Merit Sticks to Men: Gender Pay Gaps and (In)equality at UK Russell Group Universities

- ORIGINAL ARTICLE

- Open access

- Published: 12 May 2022

- Volume 86 , pages 544–558, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Carol Woodhams ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9703-1107 1 ,

- Grzegorz Trojanowski 2 &

- Krystal Wilkinson 3

6294 Accesses

4 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Academic studies of gender pay gaps within higher education institutions have consistently found pay differences. However, theory on how organisation-level factors contribute to pay gaps is underdeveloped. Using a framework of relational inequalities and advanced quantitative analysis, this paper makes a case that gender pay gaps are based on organisation-level interpretations and associated management practices to reward ‘merit’ that perpetuate inequalities. Payroll data of academic staff within two UK Russell Group universities ( N = 1,998 and 1,789) with seeming best-practice formal pay systems are analysed to determine causes of gender pay gaps. We find marked similarities between universities. Most of the variability is attributed to factors of job segregation and human capital, however we also delineate a set of demographic characteristics that, when combined, are highly rewarded without explanation. Based on our analysis of the recognition of ‘merit,’ we extend theoretical explanations of gender pay gap causes to incorporate organisation-level practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Flexible Working, Work–Life Balance, and Gender Equality: Introduction

The Participation of People with Disabilities in the Workplace Across the Employment Cycle: Employer Concerns and Research Evidence

Educational hypogamy and female employment in rural India

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The UK Higher Education (HE) sector has historically been male dominated, with evidence of horizontal and vertical segregation (Fagan & Teasdale, 2021 ). Job segregation by gender is also an international phenomenon (Macarie & Moldovan, 2015 ; Peng et al., 2017 ; Rabovsky & Lee, 2018 ). There is evidence for the closing of the HE gender gap internationally in recent decades (Baker, 2016 ) and an improvement in research outputs (Nielsen, 2016 ) and high-level jobs (Fritsch, 2015 ) for female academics. Inequalities persist, however. The causes of gender pay disparities are complex and multi-layered, but analysis of them in the higher education sector, and more generally, is theoretically and empirically incomplete. Smith ( 2009 ), for example, draws on self-report quantitative data to signal a significant gap between men and women academic staff in the UK between and within grades, and explores the implications, but not the causes, of these gaps. Traditionally, theoretical frameworks that explain gender pay differences take investment in one’s own skills and productivity as the starting point (Becker, 1975 ). However, this is a limited view that assumes that skill supply and demand will be fairly rewarded according to the logics of the market. The role of the employer in this link is overlooked.

In the current study we respond to calls to 'bring the firm back into the conceptualisation of inequalities' (Tomaskovic-Devey & Avent-Holt, 2019 , p. 7), drawing on how the relational and social construction of ‘merit’ may be connected to the power and status of workers to influence pay. Krefting ( 2003 ), for example, concludes that women faculty achievements have a lower salary pay-off, which refers to a slower time to tenure, slower time to promotion to full professor, and they earn less than men with comparable backgrounds and accomplishments. Additionally, a range of demographic (Hargens & Long, 2002 ), personal, and institutional factors (Howe-Walsh & Turnbull, 2016 ) have been linked to gender inequality, with the latter including an organisational perception of additional ‘merit’ attributed to men. Though informative, the reliance on qualitative data in these studies limits the generalisability of these findings. The current research rigorously examines ‘lower salary pay-offs’ within men’s and women’s faculty careers, and the potential for subjective and intangible ‘merit’ to be attached to certain bodies (Simpson & Kumra, 2016 ; Thornton, 2013 ).

Most publications on pay differences in HE draw conclusions from national or sectoral datasets meaning that they cannot illuminate patterns at the organisation level (i.e., Madrell et al., 2016 ). By and large, published pay data is usually aggregated, cloaking the role of organisation-level causes such as unequal promotion rates, unequal length of service, faculty specialisms, hours of engagement, types of contracts, the role of qualifications, and ultimately if and how organisational reward practices in relation to ‘merit’, sustain pay gaps. Using internal pay data at the individual employee level linked to personal employment history, we show that it is possible to account for the influence of these factors plus many others. Analysis can isolate the implications of each, building a picture of which characteristics and job patterns are most highly rewarded. These studies are rare due to the challenges of accessing comprehensive individual-level organisation data (for exceptions see Gonäs & Bergman, 2009 ; Travis et al., 2009 ). The current paper aims to enhance our understanding of causes of pay disparities in HE, criticising the effectiveness of organisation equality practice to challenge an institutionalised construction of ‘merit’ in two UK Russell Group universities.

The Russell Group is a catch-all term for 24 universities in the UK renowned for world-class research excellence and academic achievement (university league tables), including the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge (Russell Group, n.d. ). We negotiated access to employee level data; it is not normally available. The paper addresses the following research questions: (1) Is there a gender pay gap at our case- study universities and what factors explain it? (2) What does our analysis reveal about how higher education pay allocation is influenced by perceived ‘merit’?

Determinants of Pay Gaps in Higher Education

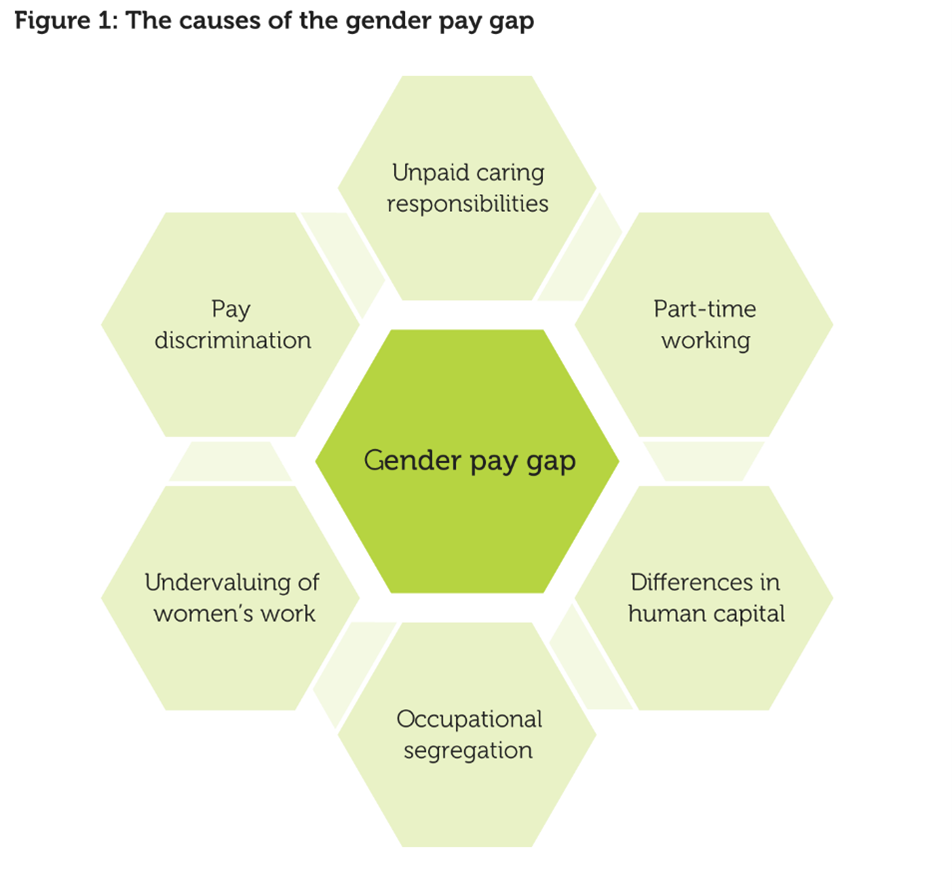

Underlying causes of the inequality gap in a whole range of industries, and specifically in higher education, are hotly disputed. Human capital theorists (e.g., Becker, 1975 ) seek to explain disparities in terms of differences in skills and experience between different groups of workers (Jacobsen, 2003 ). Women and men are seen as making different choices around the accumulation and deployment of education and skills linked to perceptions of what will bring the greatest returns, given their family commitments (Toutkoushian et al., 2007 ; Uhly et al., 2017 ). They have different ways of managing the work-life interface (Xiaoni & Caudle, 2016 ), different plans for engagement with paid work over the life-course (Metcalf, 2009 ) and have less work continuity and labour market experience due to part-time employment (Perna, 2005 ). Empirical evidence for the human capital approach specifically in relation to Higher Education comes from studies that account for human capital investment, performance measures, and type of university as explanators, and report gender pay gaps of 22% and 6.8% after controls inserted (Umbach, 2007 ).

Critics draw attention to the limitations of human capital theory, emphasising that preferences are underpinned by the gendered context of HE (Perna, 2005 ). Pay penalties in HE may emerge indirectly from the unequal effects of being segregated into types of institution, academic disciplines, contracts, and work roles that women are better able to manage alongside an uneven division of domestic work – but which have lower prestige and value. Cama et al. ( 2016 ) reported on a range of studies arguing that gender pay gaps cannot be explained by differences in individual, faculty, and institutional attributes, leaving open the possibility that there are organisational, cultural, and Human Resource (HR) effects. Gaps may also emerge because of discretionary pay practices which have the effect of disadvantaging groups in the way that 'merit' is constructed (Elvira & Graham, 2002 ). Typical of the UK HE sector, the two universities in our study formally abide by a framework of 'meritocratic' principles (Littler, 2018 ). Both deploy an objective reward system based on job evaluation plus a range of ‘best’ HR equality measures designed to overcome structural obstacles. We now discuss the potential of these measures to eliminate gender pay gaps, along with feminist critiques.

Recognising ‘Merit’ in Pay Structure Design in the UK’s HE Sector

Academic pay is determined within a market-based allocative system which seeks to reward individual effort, agency, and achievement. In theory, the design of the pay system is to produce standardised pay decisions, pegged to an objective scale, reducing flexibility and managerial discretion (Reskin, 2000 ). The establishment of a sector-wide joint negotiating committee in 2001 included the objective ‘to modernise pay arrangements with the specific aim of promoting equality, transparency and harmonisation to ensure equal pay is delivered for work of equal value’ (UCEA, 2008 : 3 as cited in Perkins & White, 2010 ). Almost all UK institutions, including our research sites, implemented the framework. The assumption is those who are not highly rewarded are not disadvantaged by unjust or discriminatory organisational practices, but rather because of their lack of personal merit (Simpson & Kumra, 2016 ); being abilities, achievements and ‘deservingness’ (Thornton, 2013 ). There are links to be made here with post-feminist governance regimes (Lewis, 2017 ) where the structural inequalities foregrounded in second-wave feminism are said to have been overcome, meaning women’s experience is dictated by their individual merit alone and feminist collective objection or action is redundant.

Critiques of Assumptions of ‘Merit’ in HE

There arelimits to assumptions of the equality of ‘merit’ between genders. Scholars argue that a socially acceptable postfeminist subjectivity requires the simultaneous performance of both ‘ideal worker’ (Acker, 1990 ) masculinity in terms of ambition, drive, and active planning, but also femininity in terms of emotional nurturing behaviour (Hochschild, 1983 ) and personal appearance (Lewis, 2017 ). As men are not required to demonstrate such dual behaviours, it can be argued that standards of ‘merit’ are unequal. Simpson and Kumra ( 2016 ) and Simpson et al. ( 2020 ) observe how narratives of ‘merit’ and ‘deservingness’ intertwine and become a gendered issue – with deservingness relying on subjective evaluations based, in part, on personal values and normative expectations – which stands in contrast to merit, which is typically presented in the HE context as an objective, gender-neutral measure, based upon qualifications and the capacity of the individual to apply them to job-related tasks (Castilla, 2008 , 2012 ; Castilla & Bernard, 2010 ; Simpson et al., 2020 ). Taken together, it is argued, merit fails to ‘stick’ to female bodies. Castilla and Bernard ( 2010 ) term this the ‘meritocracy paradox': that systems that appear to reward skills and effort may involve processes that entrench discrimination. Understandings of ‘merit’ have been and continue to be determined by those at the highest levels of the organisational hierarchy–dominated by men, although there is some interest in the rise of women in positions of power (see Huffman, 2013 ), meaning that the benchmark for success is often based upon masculine traits and the male life-course. Simpson and Kumra ( 2016 ) add that such bias is largely hidden by the desire to see merit in fixed, universal terms (Sen, 2000 ) where it can assuage concerns about unequal allocations of power and authority and provide a discursive mechanism by which inequality is justified.

It follows that merit will also fail to stick to the bodies of other individuals who differ from the white, male, able-bodied ‘ideal worker,’ which has been found in other studies, including those that study the intersectional effects of gender alongside demographic factors such as ethnicity, class, family education history and disability on employment outcomes (Bowleg, 2008 ; Crew, 2020 ; Rickett & Morris, 2021 ; Śliwa & Johansson, 2014 ; Woodhams et al., 2015 ). Whilst an espoused meritocracy, the UK HE sector is responding to significant labour market pressures, which challenge attempts to ensure standard and transparent reward allocation. Government funding has been withdrawn, so the sector is in a period of rapid global reform. To compete for global talent, pressure is brought to bear to ensure that salaries are flexible. For example, in both case study universities, following a selection panel, senior managers debate a salary point to offer based on perceived ‘deservingness’. The full grade range is available including ‘discretionary’ points in ‘exceptional’ circumstances. Pay offers are almost always negotiated (see Gamage et al., 2020 ), maybe with less motivation from female academics (Sarfaty et al., 2007 ). The agreed pay outcome is put to HR for approval and is rarely rejected. Enhanced pay increments can also be negotiated within-role as a retention payment. Subjective assessments of ‘merit’ have potential to undermine equitable outcomes.

Best Practice Equality and the ‘Merit’ Principle

It is recognised that women may be particularly constrained in demonstrating their ‘merit’ due to a range of factors such as additional responsibilities in the home domain, stereotyping and discrimination (Lewis & Simpson, 2010 ; Lips, 2013a , b ). To give them full opportunity to develop, a raft of university initiatives has been introduced (Saltmarsh & Randell-Moon, 2015 ). In our two chosen universities, initiatives cover flexible hours of work and location (Rafnsdóttir & Heijstra, 2013 ) plus a variety of academic contract types, including part-time working, fixed-term working, and term-time working. To assist with social capital development, several women’s leadership and mentoring initiatives have been introduced (see Gallant, 2014 ). Both universities hold Athena Swan awards (Advance HE, n.d. ), an external audit of good diversity practice. At least one department in each holds the highest gold level award. Compulsory training ensures equality and diversity compliance. The modern HE landscape is thus aligned with broader discussions of neoliberal feminism (Rottenberg, 2018 ) viewing the ideal neoliberal feminist subject as a ‘balanced woman’ (Rottenberg, 2014 ) who can manage a professional job role alongside intensive caring responsibilities. Neoliberal structures and cultures emphasise individual competition and merit and suggest the ‘ideal worker’ (Acker, 1990 ) is one unencumbered by responsibilities outside of work. Whilst our female academic subject might note the structures that disadvantage her as a woman (thus differentiating the neo-liberal subjectivity from the postfeminist one), she looks inwardly, guided by these workplace equality initiatives that focus on individual action and adaptation (around working hours and better ‘leaning in’ to organisational structures) to resolve the tension, rather than looking towards collective action to change underlying structures.

There is also criticism from gender scholars concerning interpretation of meritocratic principles within HE, arguing that activities that are seen to be meritorious are those on which men spend more time and have greater success. The highest valued activities when it comes to pay and progression in academia are entrepreneurial research activities (Priola, 2007 ; Thornton, 2013 ), including peer-reviewed publications in high-ranking academic journals and citation figures. There is some evidence that men outperform women in these metrics (Monroe et al., 2008 ), but this is by no means universal (Nakhaie, 2007 ; Nielsen, 2016 ; Shauman & Xie, 2003 ). Female academics tend to spend more time on pastoral work, as they are expected to be nurturing and accommodating to student requests (El-Alayli et al., 2018 ) and undertake the bulk of administration and citizenship activities (Perna, 2005 ). Male academics engage in greater institutional mobility than women academics (Leemann, 2010 ), enabling networking and increased opportunities to collaborate (Loacker & Sliwa, 2015 ). Universities tend to be sites where patriarchal relations and gendered hierarchies of power flourish to the disadvantage of women (Bagilhole & Goode, 2001 ).

Policy Implications

There are significant policy implications in this area. The UK’s Athena Swan, Gender Equality Charter Mark (Madrell et al., 2016 ) and Gender Pay Gap mandatory reporting initiatives are all shedding light on pay gaps at the employer level. These initiatives raise awareness of pay gaps and provide data that is useful in making sectoral comparisons. However, given that reported data is aggregated, there are limitations in their usefulness in illuminating comparative and potentially unfair reward practices at the employee level. Our analysis addresses that gap.

Ethical approval was sought and obtained from the University of Exeter prior to the analysis of this data. Data is secondary in nature. Data is confidential and storage arrangements complied with General Data Protection Regulations.

Sample Characteristics

Tables 1 and 2 provide descriptive statistics for two Russell Group universities that comprised the analysis. The two universities are matched in their gender spilt being 43% and 44% female. Ethnic origin data is categorised into sixteen categories. Nationality data is given in 76 categories in one university and 54 in the other. To ensure viable categories for analytical purposes they were recategorized into White/BME and British/non-British dummy variables. In University 1, 85% of men and 89% of women identify as white. Sixty-six percent of men and 61% of women identify as British. University 2 is matched with corresponding figures of 90%, 89%, 70% and 63%, respectively. Disabled status is self-nominated at the point of recruitment or by updating the self-service HR administration platform. Disabled workers comprise 4% of the workforce in both universities. Sex is given in binary format. Maternity leave taken in the past five years (yes/no) is a dummy variable for women only. The maternity leave variable cannot be added to a fully-fledged Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition as it is meaningfully defined for female academics only. It is not included in the main analyses reported. We add a note below explaining its effects entered in the regression equation.

Grade and seniority are denoted in five hierarchical bands (Associate Lecturer, Lecturer, Senior Lecturer, Reader and Professor, in order of seniority). In both universities, men are significantly more likely to be more senior in higher grades. Men have significantly longer length of service (LOS; 6.18 and 9.25 years for men, compared with 5.41 and 6.84 for women) and significantly more years in the HE sector (8.83 years compared with 8.07 for women) in University 1, but less in University 2 (11.58 years compared with 15.29). Most staff (75% and 92%) hold a doctorate as their highest-level qualification.

The dependent variable is salary. Individual payroll data was obtained for all academics employed by University 1 ( N = 1,998) and University 2 ( N = 1,789). Payroll data has greater reliability than self-reported pay (see Leslie et al., 2017 ) and greater validity for investigating the connection of employment histories to pay than aggregated data (van Wanrooy et al., 2013 ). Salary data is taken for a single month (Feb 2018 for University 1 and July 2018 for University 2). To protect the anonymity of the universities we obscure certain features including the organisation’s location in the UK. Support staff are excluded.

The salary structure in both universities is a multi-grade single pay spine linked to tenure and grade and based on a Higher Education Role Analysis job evaluation exercise. Starting salary is based on qualifications, experience, perceived merit, and previous salary. Movement between grades is determined by promotion into a different role. Scheduled pay raises (so-called 'increments') are awarded annually (as of 1 August each year) until the job holder reaches the top of the normal grade range. Each grade, except Professor, then has four to five ‘discretionary’ points that can be used to recognise extra ‘merit’. Professorial salaries are personally negotiated, subject to university-specific banding of pay. Starters and leavers have been removed from the dataset. Full-time equivalent (FTE) pay has been created to remove the effects of part-time working. Both universities award increments during maternity leave.

Salaries are attached to a common UK HE intuitions 51–point pay scale (UCU, 2022 ). There is considerable variation between universities in attaching grades to pay scale points, for example in one university a Reader grade applicant might be appointed between scale point 45 (currently £52,559) and scale point 50 (currently £60,905) and in another, the Reader scale might sit between points 41 and 47. However, internally, a university will always (in theory) appoint staff in the same academic grade to the same range of scale points. University 2 has awarded their female professors a one-off salary uplift (mean of £3,435) following Essex University (BBC News, 2016 ). The uplift was applied in Sept 2016 with reference to the mean of male professorial salaries in the discipline and taking account of length of service.

Analytic Strategy

To examine the first research question on the reasons for gender pay differences, we calculate simple mean gender differences in base pay rates. We then make use of regression analysis, which isolates gender pay differences if all other variables are held constant. This is, of course, hypothetical as men and women are rarely matched, so we use the Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition (OBD) technique (Blinder, 1973 ; Oaxaca, 1973 ). This technique identifies the extent to which pay gaps are due to the different 'endowments' of men and women. Endowments constitute differences between men and women that are meaningful within pay allocation; in other words, their simultaneous distribution across ranks of well-rewarded and less well-rewarded features. For ease of reporting, we have bundled these features into a) demographic (being age, gender, disability, ethnicity and nationality), b) human capital (education, length of service, and length of service in HE), and finally c) segregation and job (faculty of employment, grade & seniority, type of contract, duration of contract, and whether FT or PT). This analytic technique examines which differences and in what proportion men’s and women’s 'endowments' create the gender pay gap.

To address the second research question, we further explore the outcomes of the OBD highlighting the different rates of financial return to endowments, known as 'coefficients' and 'interaction' elements. These elements reveal whether having the same feature, for example a doctorate, results in a differential financial return for men, vis a vis women. Where, and if, this occurs, we consider this to be pay discrimination and indicative of an unbalanced institutionalised interpretation of salary-worthy ‘merit.’

Research Question 1

The mean salary for men academics is £50,050 and £42,192 for women ( t = 9.21, p < .001, see Table 1 ) in University 1 and £54,668 and £46,556 in University 2 ( t = 9.48, p < .001, see Table 2 ). Despite differences between universities in pay levels, gender pay differences are consistent. University 1 has a gender disparity of £8,308, or 15.7% and University 2 has £8,112 or 14.8%, favoring men. Table A1 (University 1) and A2 (University 2) in the online appendix provide mean pay based on demographic and job-related characteristics. Based on this initial analysis, we can only draw limited conclusions on ways that job, work, and personal characteristics underlie gender pay differences. To explore further, we first conduct regression analysis and then undertake Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition analyses (Jann, 2008 ).

Tables 3 and 4 give results of pooled and subsample regression analyses. Regression analysis is informative because it shows the effect on pay of a single characteristic isolated from others. The pooled (men and women) sample shows that a significant proportion of pay is explained by factors of horizontal and vertical segregation (i.e., faculty and grade), however segregation is not the only effect. Experience at the university (University 2) and in the HE sector (University 1) is positively correlated with salary, as is age and job family at both universities. Education level is not a strong predictor of wage in this sector, except that in University 2 having an ‘other’ qualification creates a significant disadvantage of £4,140 per year. After inserting all controls, detriments of £1,070 and £1,272 for women are attached to gender.

The origins of the alarming and unexplainable pay difference can be explored first via subsample regression analysis. Regression analysis measures the differences between men and women in their pay as if all other characteristics are equal. Tables 3 and 4 show that employment factors are not equally rewarded, and not always in the expected direction. For example, in both universities, men experience a penalty compared with women for being in a Humanities faculty (-£3,140 compared with -£1,932 in University 1 and -£3,012 compared with -£745 in University 2) with similar patterns in Social Science faculties. Similarly, men are paid less in every grade in University 2, when all other factors are accounted for, and in all except the Professorial grade in University 1. There is also a difference between how men and women are rewarded for length of service at both universities; men being rewarded for short service at both universities. Whilst this is an interesting analysis, it is hypothetical one because it assumes all characteristics other than gender are identical. But gender career differences are dynamic and interactional and regression analysis is imprecise as to whether and to what extent each difference contributes to the actual pay disparity between men and women. For this we turn to an OBD. What follows is an explanation of those findings.

Endowment Effects

Decomposing the pay gap shows consistency between universities. In total, as shown within Tables 5 and 6 , a total of over 81% (£6,335.60) of the gender gap at University 1 and 79% (£6,554.21) at University 2 is attributable to gender differences in bundles of endowments: being demographic, human capital, and segregation/ job characteristics. In other words, most of the pay gap is explained by differences in the way that men and women engage with the jobs, roles, and disciplines that are linked to higher [or lower] pay. A further 12% (£904.51) in University 1 and 11.9% (£978.70) in University 2 per year is due to gender differences in coefficients – i.e. differences in the way these endowments attract reward. The remaining 7% (£563.62) and 8.6% (£706.42) is due to the interaction of gender differences in coefficients and the strength of their effects.

More specifically, most of the pay gap in both universities pertains to job segregation. For example, although like-for-like women are paid more, for example, in a Reader role (as above), the fact that they are underrepresented in Reader and Professorial grades is key. If women academics were as likely to reach the Professor grade as men, the annual gender pay gap would shrink by £5,518.14 at University 1 and £6,825.93 in University 2. Additionally, women are over-represented in the low-paid research-only job family in University 1 and teaching-only job family in University 2, adding to the gender pay gap. Women are over-represented in the lowest-paying faculty (Faculty of Humanities) in University 1 and under-represented in the highest-paying faculty (Faculty of Social Sciences) in University 2. In University 2, women are over-represented in the lower-paying academic grades. Job segregation in seniority and faculty, then, explains over three-quarters of the gender discrepancy in pay in both universities (with Professoriate under-representation solely accounting for over 70%). Differences in demographic and human capital endowments also contribute to the gender disparity in pay. Since women academics are, on average, slightly younger and age has a strong positive association with pay, age constitutes another source of gender pay differences. Differences in LOS at University 1 (men have more service) also helps to explain their higher pay.

Research Question 2

We have seen that segregation (i.e., differences in ways that men and women engage in HE careers), accounts for the majority, but not all the pay difference. There are also uneven gender effects in the financial return to these features, which can be seen in the coefficient and interaction columns of Tables 5 and 6 . For example, whilst women academics being younger and less likely to hold senior academic positions contributed to the pay gap (as above), the coefficient component indicates that age and seniority have a higher return for equal endowments for men academics. Being older benefits men by £288.15 per year in University 1 and £370.33 in University 2, but women 'return' less than half (£142.17 and £170.90 per annum) of this for the exact same feature (i.e. being a year older). This unequal return to age accumulates year-on-year to contribute £5,939.98 / £8,577.29 in favour of men to the gender pay gap. Moreover, we know fewer women academics have reached the Professorial grade, however the coefficient column shows that women in University 1 reap a significantly smaller financial return after achieving it (explaining £243.33 of the gender pay gap) compared to their otherwise-equal male peers. In other words, there seems to be a 'double-whammy' discriminating effect for women: not only are they less likely to possess the characteristics associated with higher pay, even those who do so, are under-paid in comparison. University 2 appears to have staved off these effects, perhaps via their targeted salary uplift in 2016.

The effects of differences in coefficients pertaining to age and seniority are partly offset by gender differences in the effect of the length of service at both universities. Women benefit from longer tenure (reducing the pay gap by £1,889.52 / £1,278.25 pa). Whilst this might seem positive, it indicates that men, because they gain through age, but not length of service, benefit more from increased mobility. Men move more often, and this works to their financial benefit.

Differences in the financial return to demographic features are also important. At University 1, all else being equal, being British is lucrative for men academics but not women (explaining £842.15; more than 10% of the pay gap). At University 2, being white is a benefit for men only, returning an additional £1,792.81 per year into their pay packets. There is also a small, yet statistically significant, gender difference in the effects that disability has on pay in University 1, to the benefit of disabled women; and a larger advantage to women working in Humanities and the Arts in university 2 of £480.13 annually.

Interaction Effects

The aforementioned effects of age and length of service are further strengthened by the significant differences in the effects of interactions of coefficients and endowments in both datasets. For instance, the age interaction component is positive as the returns to age for men tend to be greater, while at the same time they have higher values attached to the age variable.

This paper has analysed payroll data from two UK Russell Group universities with formal payment schemes, based on incremental pay scales and job evaluation. By controlling for human capital, job segregation, and demographic variables, our findings suggest flaws with the way that gender pay differences are regarded and being addressed in academic institutions. The findings help us understand how ‘merit’ is represented within the ostensibly 'objectively determined' pay scales of both universities. As we might anticipate, most ‘merit’ is attributed to seniority and length of service. However, these features are not equally rewarded between men and matched women. The seniority effect is disproportionately advantageous (in pay terms) when attached to men. Men are rewarded for mobility while women are rewarded for loyalty. And a significant proportion of our gender pay gap is linked to features that are not of direct relevance. Men are rewarded in one university for Britishness and the other for whiteness. There are small advantages for women, but these are less numerate and not as financially advantageous.

To elaborate, our findings pertaining to our first research question support previous observations around occupational segregation in explaining pay gaps, i.e., that through conformance to social role (Eagly, 1987 ), individual preference (Hakim, 2000 ) or discriminatory treatment (Lips, 2013a ), women are under-represented in highly-paid academic roles (Doucet et al., 2012 ), and higher-paying grades (Ornstein et al., 2007 ) and over-represented in wage-depressed women-dense disciplines (Reskin & Roos, 2009 ). We show that women and men have different ‘endowments’ (i.e., men are more likely to be older and to be a Professor) that pay out to men’s advantage. Good equality practices such as those within the Athena Swan accreditation, will, if effective, decrease pay differences in relation to these factors. However, our analysis also shows in line with neo-liberal critiques that the benefit of investing in remedies like these will be limited because of organisation-level management practices.

Analysis pertaining to the second research question demonstrated that even if women were to become equally endowed, a significant proportion of the pay gap will be left untouched. Equally endowed women at University 1 earn less like-for-like in the Professorial grade. In both, they earn less each year for equal age. It could be argued that these variations stem from cohort-level differences in human capital, with older women accumulating less quality experience, even if their qualifications and length of service match, however prior literature argues that cohort effects are less significant than life-cycle effects, i.e. ageism in academia (Maguire, 1995 ). It could also be the case that the gender-specific returns to age might result from career breaks stemming from maternity leave periods, however when the maternity leave dummy is included in the regression model the main effect is not significant and other results are upheld. Additionally, length of service is most strongly rewarded if it is short and if the academic is male. Our overall finding is that women have a significant pay penalty, for reasons of segregation (which might also contain discriminatory influences that are hidden from our view), but most importantly because they do not have features in common with older white or British professors who frequently move universities.

There are two inferences here. The first inference in our findings is that pay judgements in academia are made based on an organisational-level understanding of ‘merit’ that ‘sticks’ to certain types of men’s bodies, specifically, white and British older Professors with a record of mobility. This finding supports previous work that shows how these features are of benefit to men. Results of ‘wisdom’ studies show that older men are more likely than older women to be regarded as cognitively ‘wise’ (Ardelt, 2009 ; Baltes et al., 1995 ), and that men, rather than women, inhabit the role of ‘Professor’, not ‘Teacher’, with ease (Miller & Chamberlin, 2000 ). Job mobility is lucrative for academics; however, women feel the need to build and sustain a reputation with their employer to demonstrate competence (Blackaby et al., 2005 ; Booth et al., 2003 ) rather than moving jobs to demonstrate ambition. Women remain on the margins in academia trying to prove their skills whilst men strategize reputation (Krefting, 2003 ). Finally, intersectional ethnic academic women appear to be disproportionately disadvantaged by the combination of ethnicity and nationality and gender in comparison with ethnic men and white women (Eaton et al., 2020 ; McCall, 2005 ).

The second inference points to the failure of formalised payment systems in standardising starting and ongoing salary awards. It might be that women’s actual or perceived inability to negotiate better salary packages into the discretionary grade points is the cause (Dittrich et al., 2014 ). It is well known that negotiation is a complex skill that is deeply ingrained in societal gender roles (Bowles & Babcock, 2013 ); women are less likely to be well-evaluated when they initiate negotiations (Bowles et al., 2005 ) and more likely to receive backlash (Amanatullah & Tinsley, 2013 ; Dannals et al, 2021 ; Rudman, 1998 ; Williams & Tiedens, 2016 ) which may serve to discourage them.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

There are limitations to the generalisability of our work. The paper is based on two cases with reputations for best-practice equality. Both are in the elite research-intensive group. Given the similarities between the two cases, it is highly likely that similar findings would be realised elsewhere in UK universities with a similar best practice-approach and use of standardised national pay and reward structures. However, higher pay gaps and greater wage dispersion has been found in research-intensive universities, so findings may differ in institutions that differently emphasise research output (Bailey et al., 2016 ; Mumford & Sechel, 2020 ). There are also limitations to validity of the data given that we do not have a full set of covariates on productivity/performance and how this might inform promotion and extra-ordinary decisions around base pay. Analysis of social class data, which was not available in this dataset, would add a valuable dimension of understanding for scholars interested in intersectional studies. To further strengthen our understanding of ways that organisations produce and reproduce unequal personifications of a ‘meritorious’ academic in future research projects, we encourage researchers to replicate our methodology in different universities and country contexts, comparing our outcomes with those achieved in organisations with different, and maybe less flexible, reward arrangements. We encourage studies that delve more deeply into the effects of intersecting identities on the causes of gender pay gaps for academics.

Practice Implications

Our findings have specific implications for human resource management professionals and senior leaders in HE and beyond, as they suggest flaws in the ways that gender pay differences are reproduced at the organisational level. In order to tackle the systemic problems highlighted in this paper, we recommend that alongside the typical package of positive action recruitment and promotion measures, such as mentoring (Cullen & Luna, 1993 ), changes are needed around how pay is structured and determined, as both appear to unfairly disadvantage women that are otherwise equally endowed. For example, we recommend the removal of ‘discretionary’ pay points that are typically used in circumstances where staff persistently self-proclaim their ‘merit’ to their managers, creating shorter pay scales which leave less room for managerial subjectivity to choose between pay points. We also recommend stronger guidance on the way that pay is set on appointment. A specific recommendation for University 1 is an immediate salary uplift of the type implemented at University 2. We also recommend positive action measures are extended to recognise the intersectional effects of gender with other disadvantaging personal characteristics such as nationality, ethnicity, and age. Our findings also have implications for academic women working/seeking work in UK HE institutions who may be unaware of their disadvantaged intersectional positioning, due to the principles of ‘meritocratic ideology’ underpinning existing structures and postfeminist/neoliberal feminist discourse. They are encouraged to explore collective forms of agency more akin to second-wave feminist action, such as vocal protest against pay disparities and engagement in trade union action.

Explanations of gender pay gaps are complex and multi-layered. In part, as previously identified in higher education, they result from differences in occupational segregation (Blau & Kahn, 2017 ), which is being tackled in many universities via established equality practice. Our findings, however, indicate additional contributors to pay gaps linked to intersecting features, for example increased age is less advantageous for women, and disability potentially less advantageous for men, and how organisation-level recognition of ‘merit’ sticks to certain bodies, enabled by specific and widespread reward practices. In conclusion we argue that pay structures premised on ‘meritocracy’, and initiatives that aim to level the playing field for academic women under the banner of 'best practice' reinforce postfeminist or neoliberal feminist sensibilities. Women academics, unknowingly complicit, look inwardly for the resolution of disadvantage whilst structures continue to discriminate against them.

However, our primary point here is that salary negotiation involves two parties and responsibility lies with those that carry institutional authority to recognise and reward to ensure that perceived ‘merit’ does not cloud judgement. We contend that our research raises awareness that the organisational space in which resource allocation takes place is influenced by socially defined relational power inequalities (Tomaskovic-Devey & Avent-Holt, 2019 ) that shape perceptions of ‘meritorious’ and ‘deserving’ features.

Data Availability

Data is held by each institution. We have a contract to publish with express agreement, but not to share data.

Code Availability

STATA code available on request.

Acker, J. (1990). Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: A theory of gendered organizations. Gender & Society, 4 (2), 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124390004002002

Article Google Scholar

Advance HE. (n.d.). Athena Swan Charter . https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/equality-charters/athena-swan-charter

Amanatullah, E., & Tinsley, C. (2013). Punishing female negotiators for asserting too much…or not enough: Exploring why advocacy moderates backlash against assertive female negotiators. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 120 (1), 110–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2012.03.006

Ardelt, M. (2009). How similar are wise men and women? A comparison across two age cohorts. Research in Human Development, 6 (1), 9–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427600902779354

Bailey, J., Peetz, D., Strachan, G., Whitehouse, G., & Broadbent, K. (2016). Academic pay loadings and gender in Australian universities. Journal of Industrial Relations, 58 (5), 647–668. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185616639308

Bagilhole, B., & Goode, J. (2001). The contradiction of the myth of individual merit, and the reality of a patriarchal support system in academic careers: A feminist investigation. European Journal of Women's Studies, 8 (2), 161–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/135050680100800203

Baker, M. (2016). Women graduates and the workplace: Continuing challenges for academic women. Studies in Higher Education, 41 (5), 887–900. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1147718

Baltes, P. B., Staudinger, U. M., Maercker, A., & Smith, J. (1995). People nominated as wise: A comparative study of wisdom-related knowledge. Psychology and Aging, 10 (2), 155. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.10.2.155

Article PubMed Google Scholar

BBC News. (2016). University wipes out gender pay gap with salary hike . https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-36444063

Becker, G. (1975). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education . University of Chicago Press.

Google Scholar

Blackaby, D., Booth, A., & Frank, J. (2005). Outside offers and the gender pay gap: Empirical evidence from the UK academic labour market. The Economic Journal, 115 (501), F81–F107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0013-0133.2005.00973.x

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2017). The gender wage gap: Extent, trends, and explanations. Journal of Economic Literature, 55 (3), 789–865. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20160995

Blinder, A. S. (1973). Wage discrimination: Reduced form and structural estimates. The Journal of Human Resources, 8 (4): 436–455. https://doi.org/10.2307/144855

Booth, A. L., Francesconi, M., & Frank, J. (2003). A sticky floors model of promotion, pay, and gender. European Economic Review, 47 (2), 295–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-2921(01)00197-0

Bowleg, L. (2008). When Black + lesbian + woman ≠ Black lesbian woman: The methodological challenges of qualitative and quantitative intersectionality research. Sex Roles, 59 , 312–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9400-z

Bowles, H. R., & Babcock, L. (2013). How can women escape the compensation negotiation dilemma? Relational accounts are one answer. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37 (1), 80–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684312455524

Bowles, H. R., Babcock, L., & McGinn, K. L. (2005). Constraints and triggers: Situational mechanics of gender in negotiation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89 (6), 951. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.951

Cama, G. M., Jorge, L. M., & Peña, A. F. J. (2016). Gender differences between faculty members in higher education: A literature review of selected higher educational journals. Educational Research Review, 18 , 58–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2016.03.001

Castilla, E. J. (2008). Gender, race, and meritocracy in organizational careers. The American Journal of Sociology, 113 (6), 1479–1526. https://doi.org/10.1086/588738

Castilla, E. J. (2012). Gender, race, and the new (merit-based) employment relationship. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 51 (s1), 528–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-232X.2012.00689.x

Castilla, E. J., & Benard, S. (2010). The paradox of meritocracy in organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 55 (4), 543–676. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.2010.55.4.543

Crew, T. (2020). Higher education and working-class academics . Springer International Publishing.

Cullen, D. L., & Luna, G. (1993). Women mentoring in academe: Addressing the gender gap in higher education. Gender and Education, 5 (2), 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/0954025930050201

Dannals, J. E., Zlatev, J. J., Halevy, N., & Neale, M. A. (2021). The dynamics of gender and alternatives in negotiation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106 (11), 1655–1672. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000867

Dittrich, M., Knabe, A., & Leipold, K. (2014). Gender differences in experimental wage negotiations. Economic Inquiry, 52 (2), 862–873. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecin.12060

Doucet, C., Smith, M., & Durand, C. (2012). Pay structure, female representation and the gender pay gap among university professors. Relations Industrielles/ Industrial Relations, 67 (1), 51–75. https://doi.org/10.7202/1008195ar

Eagly, A. H. (1987). Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Eaton, A. A., Saunders, J. F., Jacobson, R. K., & West, K. (2020). How gender and race stereotypes impact the advancement of scholars in STEM: Professors’ biased evaluations of physics and biology post-doctoral candidates. Sex Roles, 82 (3), 127–141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-01052-w

El-Alayli, A., Hansen-Brown, A. A., & Ceynar, M. (2018). Dancing backwards in high heels: Female professors experience more work demands and special favor requests, particularly from academically entitled students. Sex Roles, 79 , 136–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0872-6

Elvira, M. M., & Graham, M. (2002). Not just a formality: Pay system formalisation and sex- related earnings effects. Organisation Science, 13 (6), 601–617. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.13.6.601.499

Fagan, C., & Teasdale, N. (2021). Women professors across STEMM and non-STEMM disciplines: Navigating gendered spaces and playing the academic game. Work, Employment and Society, 35 (4), 774–792. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017020916182

Fritsch, N. (2015). At the leading edge – does gender still matter? A qualitative study of prevailing obstacles and successful coping strategies in academia. Current Sociology, 63 (4), 547–565. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392115576527

Gallant, A. (2014). Symbolic interactions and the development of women leaders in Higher Education. Gender, Work and Organization, 21 (3), 203–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12030

Gamage, D. D. K., Kavetsos, G., Mallick, S., & Sevilla, A. (2020). Pay transparency initiative and gender pay gap: Evidence from research-intensive universities in the UK. IZA Discussion Paper No. 13635 https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/13635/pay-transparency-initiative-and-gender-pay-gap-evidence-from-research-intensive-universities-in-the-uk

Gonäs, L., & Bergman, A. (2009). Equal opportunities, segregation and gender-based wage differences: The case of a Swedish university. The Journal of Industrial Relations, 51 (5), 669–686. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185609346198

Hakim, C. (2000). Work-lifestyle choices in the 21st century: Preference theory . Oxford University Press

Hargens, L. L., & Long, J. S. (2002). Demographic inertia and women’s representation among faculty in higher education. The Journal of Higher Education, 73 (4), 494–517. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2002.11777161

Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart . University of California Press.

Howe-Walsh, L., & Turnbull, S. (2016). Barriers to women leaders in academia: Tales from science and technology. Studies in Higher Education, 41 (3), 415–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.929102

Huffman, M. L. (2013). Organizations, managers, and wage inequality. Sex Roles, 68 , 216–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-012-0240-5

Jacobsen, J. (2003). The human capital explanation for the gender gap in earnings. In K. Moe (Ed.), Women, family, and work: Writings on the economics of gender . Blackwell.

Jann, B. (2008). The Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition for linear regression models. The Stata Journal, 8 (4), 453–479. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X0800800401

Krefting, L. (2003). Intertwined discourses of merit and gender: Evidence from academic employment in the USA. Gender, Work and Organisation, 10 (2), 260–278. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0432.t01-1-00014

Leemann, R. (2010). Gender inequalities in transnational academic mobility and the ideal type of academic entrepreneur. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 31 (5), 605–625. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2010.516942

Leslie, L., Flaherty Manchester, C., & Dahm, P. (2017). Why and when does the gender gap reverse? Diversity goals and the pay premium for high potential women. Academy of Management Journal, 60 (2), 402–432. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2015.0195

Lewis, P., & Simpson, R. (2010). Meritocracy, difference and choice: Women’s experiences of advantage and disadvantage at work. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 25 (3), 165–169. https://doi.org/10.1108/17542411011036374

Lips, H. M. (2013a). The gender pay gap: Challenging the rationalizations, perceived equity, discrimination, and the limits of human capital models. Sex Roles, 68 , 169–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-012-0165-z

Lips, H. M. (2013b). Acknowledging discrimination as a key to the gender pay gap. Sex Roles, 68 , 223–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-012-0245-0

Littler, J. (2018). Against meritocracy: Culture, power and myths of mobility (1st ed.). Routledge.

Loacker, B., & Sliwa, M. (2015). Moving to stay in the same place?’ Academics and theatrical artists as exemplars of the ‘mobile middle. Organization, 23 (5), 657–679. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508415598247

Macarie, F. C., & Moldovan, O. (2015). Horizontal and vertical gender segregation in higher education: EU 28 under scrutiny. Managerial Challenges of the Contemporary Society. Proceedings, 8 (1): 162.

Madrell, A., Strauss, K., Thomas, N., & Wyse, S. (2016). Mind the gap: Gender disparities still to be addressed in UK Higher Education geography. Area, 48 (1), 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12223

McCall, L. (2005). The complexity of intersectionality. Signs, 30 (3), 1771–1801. https://doi.org/10.1086/426800

Metcalf, H. (2009). Pay gaps across the equality strands: A review. Equality and Human Rights Commission Research Report 14 . https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/research-report-14-pay-gaps-across-equality-strands.pdf

Miller, J., Chamberlin, M. (2000). Women are teachers, men are professors: A study of student perceptions. Teaching Sociology , 28 (4) 283–298. https://doi.org/10.2307/1318580

Monroe, K., Ozyurt, S., Wrigley, T., & Alexander, A. (2008). Gender equality in academia: Bad news from the trenches, and some possible solutions. Perspectives on Politics, 6 (2), 215–233. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592708080572

Mumford, K., & Sechel, C. (2020). Pay and Job Rank among Academic Economists in the UK: Is Gender Relevant? British Journal of Industrial Relations, 58 (1), 82–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjir.12468

Nakhaie, M. R. (2007). Universalism, ascription and academic rank: Canadian professors, 1987–2000. Canadian Review of Sociology/revue Canadienne De Sociologie, 44 (3), 361–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-618X.2007.tb01190.x

Nielsen, M. (2016). Gender inequality and research performance: Moving beyond individual-meritocratic explanations of academic advancement. Studies in Higher Education, 41 (11), 2044–2060. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1007945

Oaxaca, R. (1973). Male-female wage differentials in urban labor markets. International Economic Review, 14 (3), 693–709. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2525981

Ornstein, M., Stewart, P., & Drakich, J. (2007). Promotion at canadian universities: The intersection of gender, discipline, and institution. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 37 (3), 1–25.

Peng, Y. W., Kawano, G., Lee, E., Tsai, L. L., Takarabe, K., Yokoyama, M., Ohtsubo, H., & Ogawa, M. (2017). Gender segregation on campuses: A cross-time comparison of the academic pipeline in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. International Journal of Gender, Science and Technology , 9 (1), 3–24. http://genderandset.open.ac.uk/index.php/genderandset/article/view/409

Perkins, S. J., & White, G. (2010). Modernising pay in the UK public services: Trends and implications. Human Resource Management Journal, 20 (3), 244–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2009.00125.x

Perna, L. (2005). Sex difference in faculty tenure and promotion: The contribution of family ties. Research in Higher Education, 46 , 277–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-004-1641-2

Priola, V. (2007). Being female doing gender. Narratives of women in education management. Gender and Education , 19 (1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250601087728

Rabovsky, T., & Lee, H. (2018). Exploring the antecedents of the gender pay gap in US higher education. Public Administration Review, 78 (3), 375–385. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12827

Rafnsdóttir, G., & Heijstra, T. (2013). Balancing work-family life in academia: The power of time. Gender, Work and Organization, 20 (3), 283–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2011.00571.x

Reskin, B. F. (2000). The proximate causes of employment discrimination. Contemporary Sociology, 29 (2), 319–328. https://doi.org/10.2307/2654387

Reskin, B. F., Roos, P. A. (2009). Job queues, gender queues: Explaining women's inroads into male occupations. Temple University Press.

Rottenberg, C. A. (2014). Happiness and the liberal imagination: How superwoman became balanced. Feminist Studies, 40(1) , 144–168. https://doi.org/10.15767/feministstudies.40.1.144

Rottenberg, C. A. (2018). The rise of neoliberal feminism . Oxford University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Rudman, L. A. (1998). Self-promotion as a risk factor for women: The costs and benefits of counterstereotypical impression management. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74 (3), 629. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.629

Saltmarsh, S., & Randell-Moon, H. (2015). Managing the risky humanity of academic workers: Risk and reciprocity in university work-life balance policies. Policy Futures in Education, 13 (5), 662–682. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210315579552

Sarfaty, S., Kolb, D., Barnett, R., Szalacha, L., Caswell, C., Inui, T., & Carr, P. L. (2007). Negotiation in academic medicine: A necessary career skill. Journal of Women’s Health, 16 (2), 235–244. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2006.0037

Sen, A. (2000). Merit and justice in meritocracy and economic inequality, in K. Arrow, S. Bowles, & S. N. Durlauf, (Eds.), Meritocracy and inequality . Princeton University Press.

Shauman, K. A., Xie, Y. (2003). Explaining sex differences in publication productivity among postsecondary faculty. In L.S Hornig (Ed.), Equal rites, unequal outcomes (pp. 175–208). Springer.

Simpson, R., & Kumra, S. (2016). The Teflon effect: When the glass slipper meets merit. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 31 (8), 562–576. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-12-2014-0111

Simpson, R., Kumra, S., Lewis, P., & Rumens, N. (2020). Towards a performative understanding of deservingness: Merit, gender and the BBC pay dispute. Gender, Work and Organisation, 27 (2), 181–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12397

Śliwa, M., & Johansson, M. (2014). The discourse of meritocracy contested/reproduced: Foreign women academics in UK business schools. Organization, 21 (6), 821–843. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508413486850

Smith, M. (2009). Gender, pay and work satisfaction in a UK university. Work, Employment and Society, 16 (5), 621–641. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2008.00403.x

Thornton, M. (2013). The mirage of merit: Reconstituting the ’ideal academic’. Australian Feminist Studies, 28 (76), 127–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/08164649.2013.789584

Tomaskovic-Devey, D., & Avent-Holt, D. (2019). Relational inequalities: An organizational approach . Oxford University Press.

Toutkoushian, R., Bellas, M., & Moore, J. (2007). The interaction effects of gender, race, and marital status on faculty salaries. The Journal of Higher Education, 78 (5), 572–601. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2007.11772330

Travis, C., Gross, L., & Johnson, B. (2009). Tracking the gender pay gap: A case study. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33 (4), 410–418. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2009.01518.x

Uhly, K., Visser, L., & Zippel, K. (2017). Gendered patterns in international research collaborations in academia. Studies in Higher Education, 42 (4), 760–782. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1072151

Umbach, P. (2007). Gender equity in the academic labour market: An analysis of academic disciplines. Research in Higher Education, 48 , 169–192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-006-9043-2

van Wanrooy, B., Bewley, H., Bryson, A., Forth, J., Freeth, S., Stokes, L., & Wood, S. (2013). Employment relations in the shadow of recession: Findings from the 2011 Workplace Employment Relations Study . Palgrave MacMillan.

Williams, M. J., & Tiedens, L. Z. (2016). The subtle suspension of backlash: A meta-analysis of penalties for women’s implicit and explicit dominance behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 142 (2), 165–197. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000039

Woodhams, C., Lupton, B., & Cowling, M. (2015). The presence of ethnic minority and disabled men in feminised work: Intersectionality, vertical segregation and the glass escalator. Sex Roles, 72 , 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0427-z

Xiaoni, R., & Caudle, D. (2016). Walking the tightrope between work and non-work life: Strategies employed by British and Chinese academics and their implications. Studies in Higher Education, 41 (4), 599–618. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.942277

Download references

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the provision of data from the two anonymised university institutions and to the anonymous reviewers for their comments.

Research was not directly funded.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Surrey Business School, University of Surrey, Surrey, UK

Carol Woodhams

University of Exeter Business School, Exeter, UK

Grzegorz Trojanowski

Manchester Metropolitan University Business School, Manchester, UK

Krystal Wilkinson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Carol Woodhams and Grzegorz Trojanowski. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Krystal Wilkinson and Carol Woodhams and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Carol Woodhams .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest.

We do not have conflicts of interest or competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (DOCX 18 KB)

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Woodhams, C., Trojanowski, G. & Wilkinson, K. Merit Sticks to Men: Gender Pay Gaps and (In)equality at UK Russell Group Universities. Sex Roles 86 , 544–558 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-022-01277-2

Download citation

Accepted : 28 February 2022

Published : 12 May 2022

Issue Date : May 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-022-01277-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Gender pay gap

- UK Russell Group

- Discrimination

- Relational inequalities

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Cookies on GOV.UK

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We’d like to set additional cookies to understand how you use GOV.UK, remember your settings and improve government services.

We also use cookies set by other sites to help us deliver content from their services.

You have accepted additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

You have rejected additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

Bring photo ID to vote Check what photo ID you'll need to vote in person in the General Election on 4 July.

The gender pay gap in the UK: evidence from the UKHLS

Research into the main predictors of the gender pay gap.

Ref: ISBN 978-1-78105-875-6, DFE-RR804

PDF , 644 KB , 36 pages

This is a report on research undertaken by Professor Wendy Olsen, Dr Vanessa Gash, Sook Kim, and Dr Min Zhang on behalf of the Government Equalities Office.

The primary aim of this research is to identify the factors that influence the gender pay gap in the UK.

The work uses decomposition techniques to analyse the main predictors of the gender pay gap using waves of the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS) and the United Kingdom Household Longitudinal Survey (UKHLS) relating to 2014 to 2015.

The gender pay gap is the difference between men’s and women’s average hourly earnings.

Related content

Is this page useful.

- Yes this page is useful

- No this page is not useful

Help us improve GOV.UK

Don’t include personal or financial information like your National Insurance number or credit card details.

To help us improve GOV.UK, we’d like to know more about your visit today. Please fill in this survey (opens in a new tab) .

- Leeds University Business School

- Departments

"Can Human Capital Theory Alone Explain the Variation in the Gender Pay Gap throughout the United Kingdom? A Comparative Case Study of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland" by Courtney Owens

Can Human Capital Theory Alone Explain the Variation in the Gender Pay Gap throughout the United Kingdom? A Comparative Case Study of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland

- Courtney Owens - Dissertation edit 2019 (PDF 1.06 MB) Download

Investigating the driving forces behind low pay and the gender pay gap

- Justice and Equality

- Risk, Evidence and Decision Making

Our research conducted with the Low Pay Commission has made a new contribution to the understanding of wage inequality in the UK.

Karen Mumford

Professor Mumford's expertise is labour economics. Her research topics include: wage bargaining, industrial disputation, employment dynamics, the relative labour market position of women and job satisfaction. She was appointed CBE for services to Economics and Labour Market Diversity in the 2016 New Year’s Honours List.

View profile

Peter Smith

Professor Smith is Professor of Economics and Finance. He is engaged in research in areas of financial economics, macro economics and labour economics.

Case studies

Read more examples of York research making a difference.

Explore more research from the Department of Economics and Related Studies.

Business and society

Explore more research from the School for Business and Society.

Rachel Reeves wants to end the UK’s gender pay gap for good – here’s how she could do it

Research Fellow, University of Sussex

Disclosure statement

Rachel Verdin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Sussex provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

Shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves has declared she wants to end the gender pay gap once and for all. If Labour is elected, she said , firms would be required to publish action plans, increase the number of female executives and improve flexibility in the workplace.

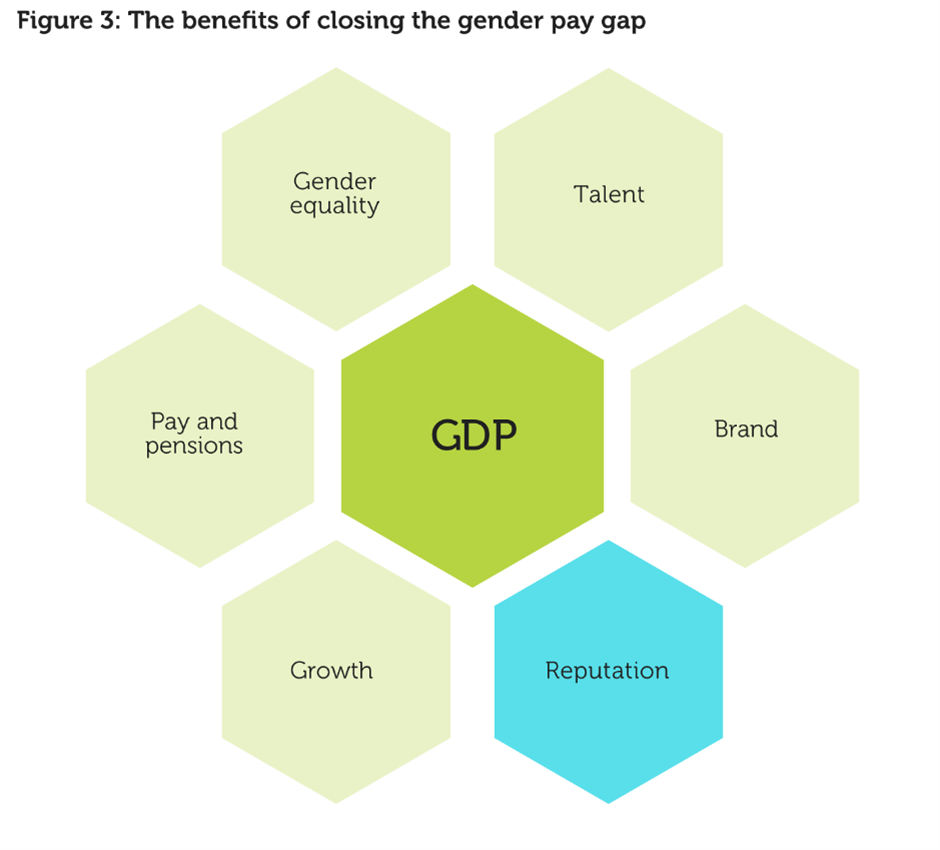

These initiatives would be both necessary and welcome. Reeves may become the UK’s first female chancellor and finally closing the gender pay gap would be a historic achievement – boosting women’s earnings by as much as £55 billion a year . But is her plan bold enough to deliver on its promise? My research on the huge gender pay gap in the finance sector and exploring measures being taken in other countries suggests she may need to go further.

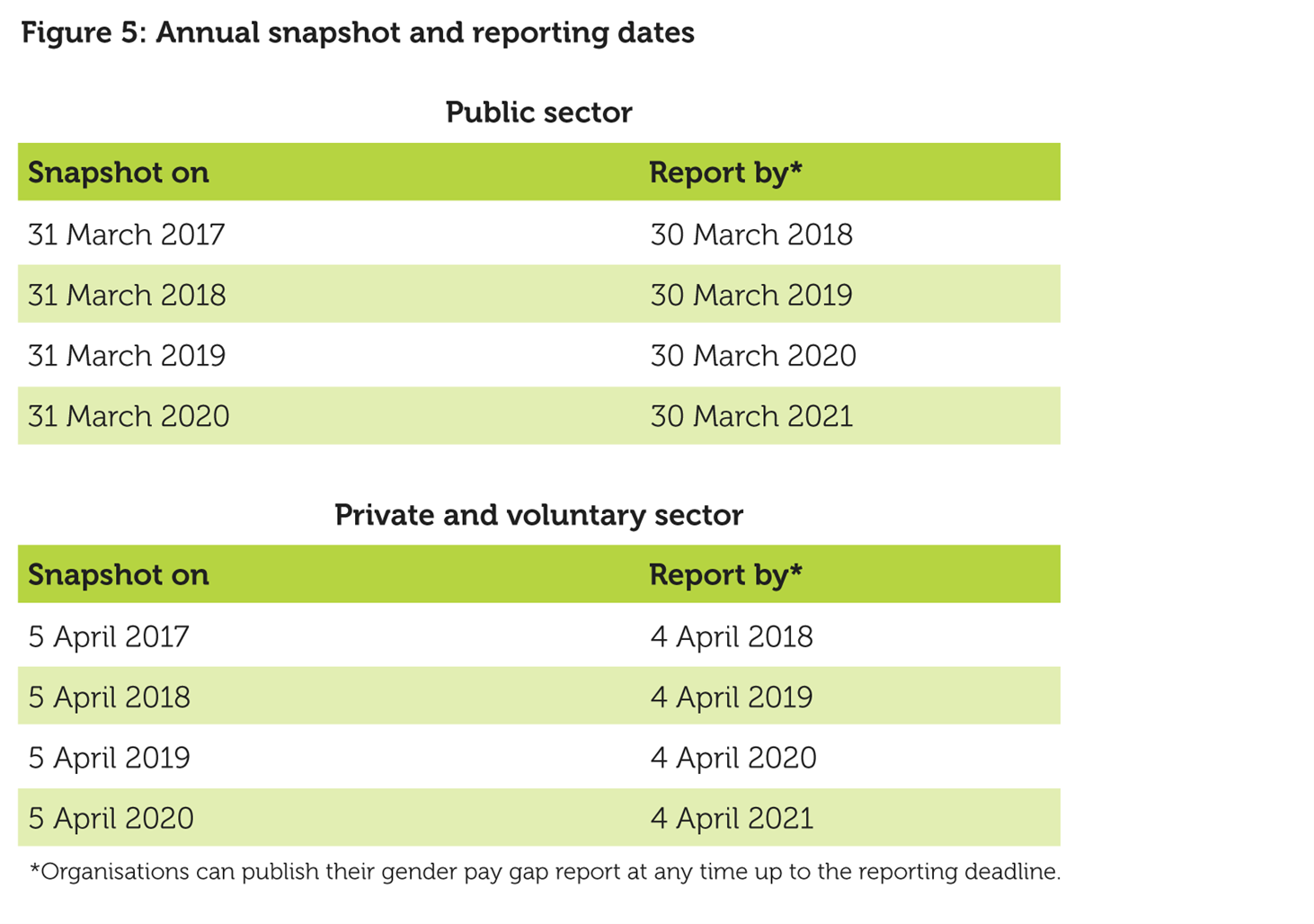

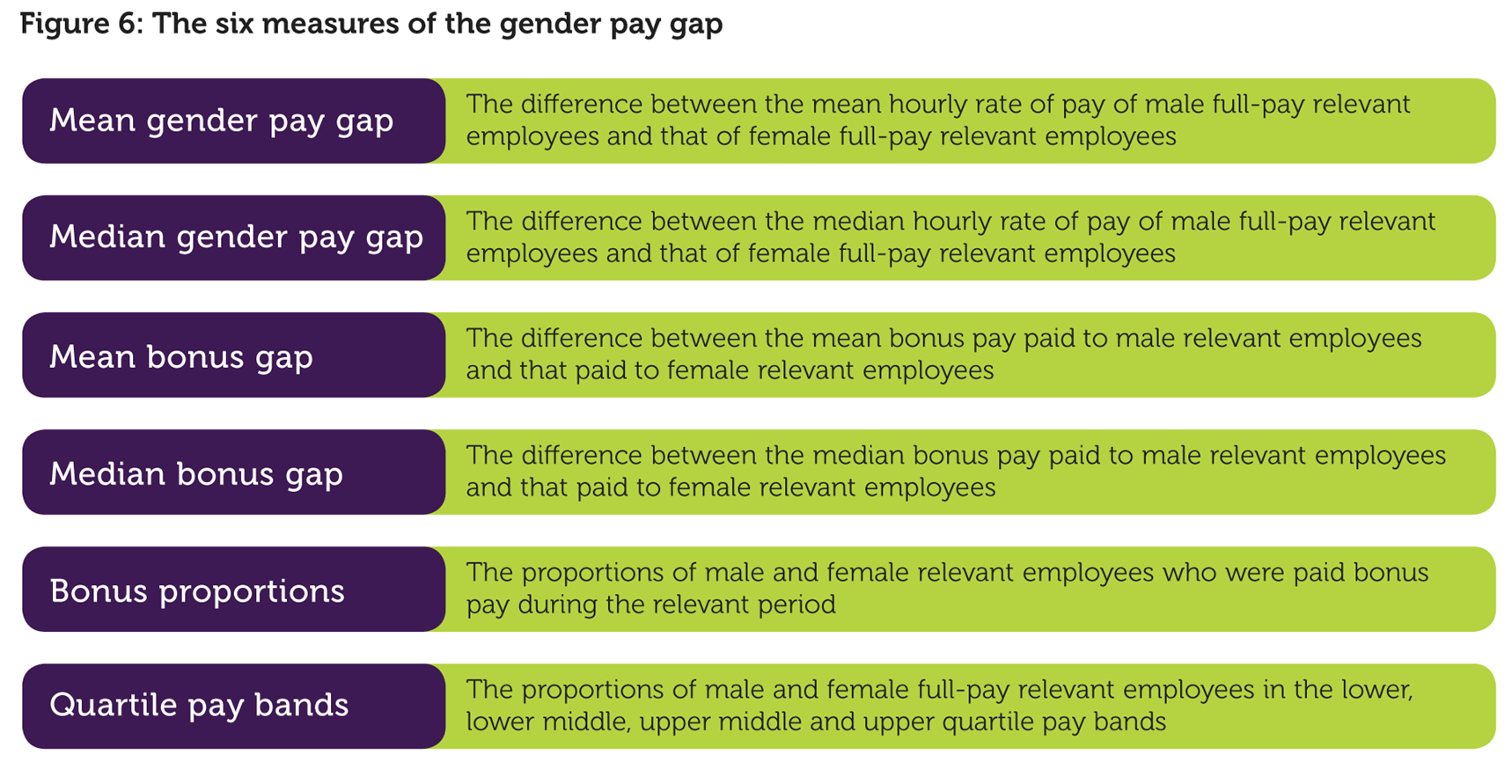

UK employers have been required to publish information about their gender pay gaps since 2017. The gender pay reporting regulations oblige firms with 250 employees or more to make public six calculations of their gender pay gaps on an annual basis.

The intention was to sharpen an organisation’s focus on equality, diversity and inclusion, and bring some much-needed transparency to the problem. In that sense, there has been some success. Observers can now monitor developments over time, by firm and sector.

However, in seven years the overall pay gap has reduced by only 1.2 percentage points from 12.8% (2017) to 11.6% (2024) . In some sectors, such as finance, gaps are significantly larger.

In 2024, the UK’s big four banks (Lloyds, HSBC, Barclays and NatWest) reported pay gaps as high as 48% and bonus gaps up to 74%. Goldman Sachs’ current gap is bigger than at any point in the last six years. The lack of movement in areas like corporate and investment banking has been described in evidence to parliament as “appalling” .

After the initial shock and media frenzy surrounding pay reports died down, it seems companies have become inured to the embarrassment of a bad report. It’s clear that naming and shaming organisations into action has failed.

Want more election coverage from The Conversation’s academic experts? Over the coming weeks, we’ll bring you informed analysis of developments in the campaign and we’ll fact check the claims being made. Sign up for our new, weekly election newsletter , delivered every Friday throughout the campaign and beyond.

So how can we stop diversity-fatigue setting in and reinvigorate this agenda?

Reeves is right – simply publishing data about pay gaps is insufficient. She proposes, therefore, to demand that firms publish action plans that set out how they will close the gap. The idea is that compelling firms to have strategies in place will lead to reductions. However, many firms already voluntarily publish action plans alongside the mandatory pay gap information. So why hasn’t this led to more progress?

In my new book, Architectures of Inequality , I examine both progress and resistance in tackling the UK’s gender pay gap. My analysis of the plans published by firms in the finance sector shows that best practice initiatives, such as women’s networking groups and flexible working, have increased.

However, my research also shows that while firms are keen to trumpet flexible working policies, they often don’t “walk the talk”. Firms including JPMorgan and Nationwide are even rolling back on hybrid working policies. At the same time, much less is being done to improve internal transparency over pay, bonus and negotiation systems, which, despite good evidence that they are effective at reducing pay gaps, are routinely disregarded.

Let’s talk about pay

We know that no one likes to talk about pay. But practices such as salary secrecy, performance-related pay systems and individual pay negotiation only serve to reinforce and protect inequities.

The government made some attempt to address this with a voluntary pay transparency pilot scheme launched in March 2022. Participating employers committed to publishing salaries on job adverts. However, in line with previous failed voluntary policy efforts , salary transparency remained at an all-time low and, two years on, the scheme seems all but forgotten.

The UK is no longer a leader on this agenda and government and employers could learn from developments abroad. Australia , Canada and parts of the US have implemented more extensive transparency requirements, such as banning employers from requesting salary information from job applicants and enhancing the right of women to know what male colleagues earn.

Since Brexit, the EU has also adopted new rules on pay transparency , going far beyond the UK requirement . There are also mandatory quotas for the representation of women at board level .

To go further and faster in fixing the gap, the UK first needs to catch up , as two successive parliamentary inquiries have pointed out.

Given the UK’s lack of progress, Reeves’ renewed ambition to close the gender pay gap for good is very welcome. But to really shift the dial on gender pay inequity she may need to go further. Updating the outdated gender pay reporting regulations and legislating for greater pay transparency would be a good start.

- Labour Party

- Gender pay gap

- Rachel Reeves

- Give me perspective

Centre Director, Transformative Media Technologies

Stephen Knight Lecturer in Medieval Literature

Postdoctoral Research Fellowship

Social Media Producer

Dean (Head of School), Indigenous Knowledges

Library Dissertation Showcase

An exploration of gender pay gap reporting in twenty ftse 100 companies.

- Kelson Mears

- International Business

- International Business Management

- Year of Publication:

- BA (Hons) International Business Management

This document uses existing literature to identify and critically analyse the causes and the extent of the presence of the gender pay gap in the UK. The broad range of concepts introduced in the Literature Review allows an appreciation of the complexity involved in narrowing this disparity , revealing the need for societal changes as well as changes to corporate policies. Goal-setting theory is introduced also, with the aim of aiding in identifying potentially effective objectives within company gender pay reports. These reports, of the top twenty FTSE l 00 companies for female boardroom representation, are qualitatively analysed herein using a mixed methods approach of both thematic analysis (Saunders, et al., 2016) and data display and analysis (Miles, et al., 2014). Whilst there is a comprehensive range of existing research around the gender pay gap, as seen in the Literature Review, little research exists concerning the language of each company’s gender pay reporting and how effective the release of these reports is likely to be in accelerating the closure of the gender pay gap. The Methodology chapter will provide context to this research by presenting its paradigm and design, before defining and justifying how the research was carried out to the highest standards of validity and reliability. The Findings section will explore the discourse of gender pay reporting within the sample by using quotations to illustrate the companies’ efforts, concluding that companies are targeting the main causes of the gender pay gap identified in the Literature Review. Particularly: the issue of few female employees in senior and leadership roles; workplace cultures favouring men over women; and the labour market interruptions experienced by more women bearing child-raising responsibilities than men. However, these targeted efforts are not universally reflected by clear objectives and until this changes, progress within the companies to which this applies is likely to be slow. This research might be continued by examining in greater depth the gender bonus gap and the effect of long-tern incentive plans on the overall pay gap of senior roles. Additionally, research into the negative fulltime gender pay gap of Northern Ireland found on page 13 in the Literature Review, might be further explored.

PLEASE NOTE: You must be a member of the University of Lincoln to be able to view this dissertation. Please log in here.

We use cookies to understand how visitors use our website and to improve the user experience. To find out more, see our Cookies Policy .

- Economics Dissertations

- All Economics Dissertations

Analysis the Components of the Gender Pay Gap in the UK: What are the Main Components of the Gender Pay Gap, and to What Extent do they Contribute to this Inequality? (2010)

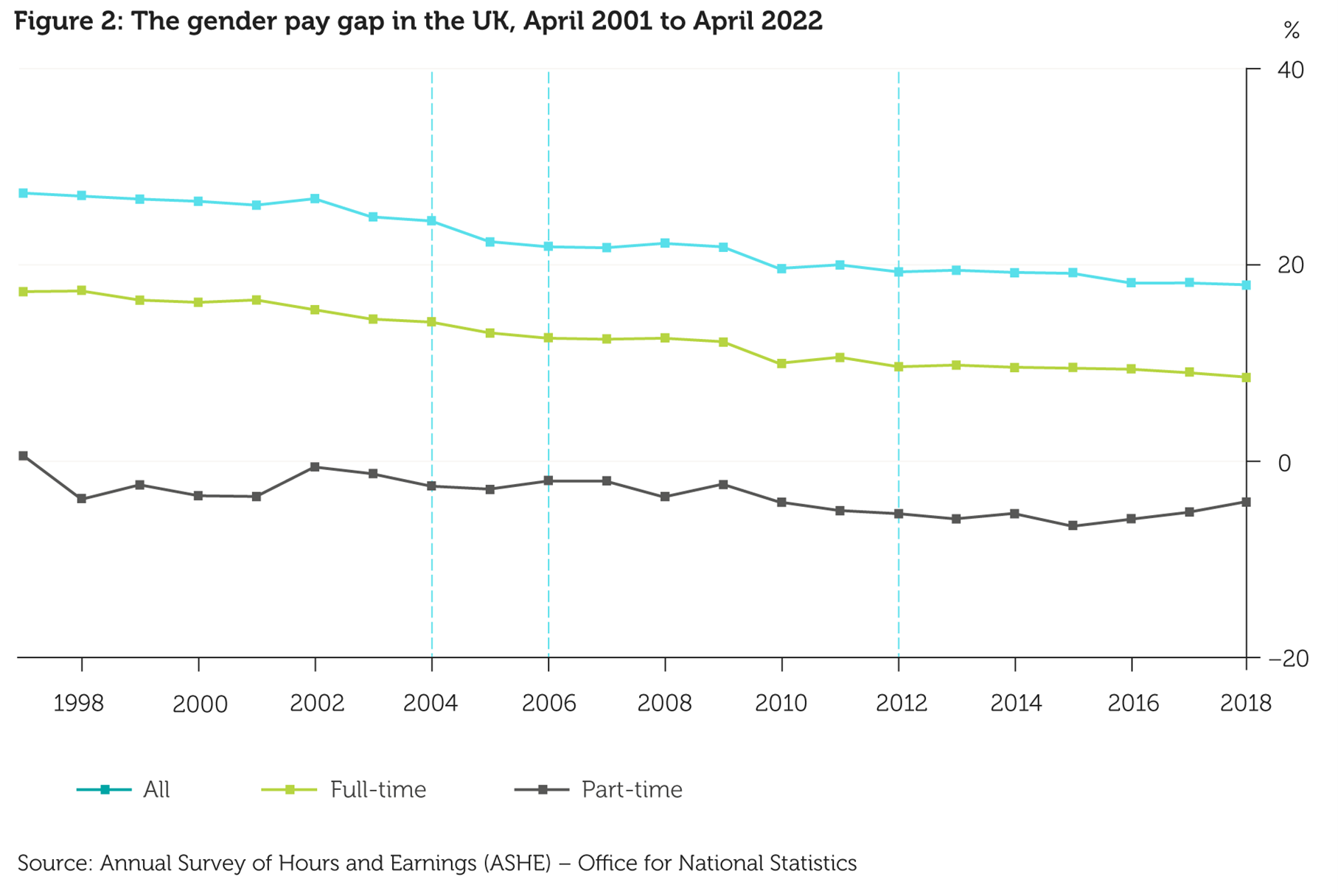

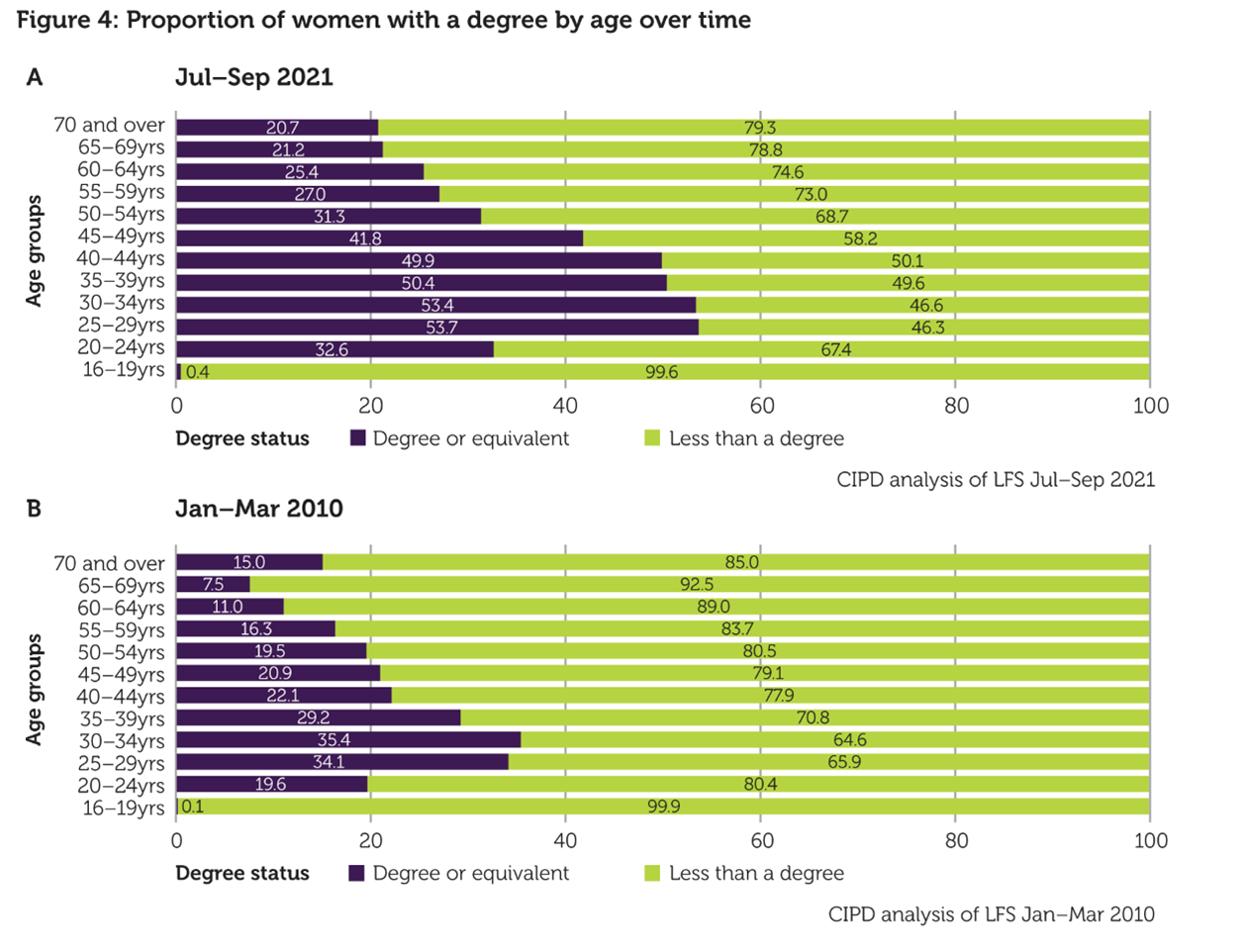

What is the size of the gender pay gap in the UK? What are the main components which contribute to this gap? There have been various changes in gender relations and labour market structure, all of which have affected the pay gap. Increase in women’s educational attainment, anti-discrimination legislation and changes in women’s attitudes towards work have all caused the gap to narrow in recent years.

The Oaxaca decomposition of the gender pay gap distinguishes between components that attribute to gender differences in productivity related characteristics and a residual component which is normally recognised as discrimination. This study of data from the 2010 British labour survey shows there is a gender pay gap of approximately 14.8% of which much is attributed to uneven distribution of sexes in occupational and industrial sectors.

However it is concluded that it is misleading to assume occupational and industrial sectors as productivity-related characteristics, nonetheless they are components which contribute to the overall gender pay gap.

Over the last thirty years, the full time pay gap has narrowed markedly while there has only been a slender reduction in the part-time pay gap. The introduction of the Equal pay act in 1975 has helped to reduce this inequality and today the pay gap stands at 18.4 percent compared to a much more substantial 30 percent before the act was introduced. Part of the gap can be explained by differences in the observed characteristics of both genders, such as education and experience. However, even once taking into account these factors affecting productivity a significant gap is left unexplained. This unexplained gap derives from either employer discrimination or non-observed productivity differential.

This dissertation will initially begin with of a brief history of the gender pay gap in the UK and then go on to explain the factors which contribute to the gap such as human capital endowments and discrimination. Following this there will be a review of previous literature, description of the data and variables which are to be used for econometric analysis followed by the analysis and empirical findings of my study. Conclusions will be presented in the final section.

- 12,000 words – 60 pages in length

- Excellent use of literature

- Excellent use of economics and data analysis models: Oaxaca Decomposition, Multi Collinearity, Chow Test, Ramsey RESET, Jarque Bera and Hetroskedasticity

- Well written throughout

- Ideal for any Economics student

1. Introduction

2. Background and Stylised Facts