- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Alcohol and Alcoholism

- About the Medical Council on Alcohol

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Contact the MCA

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Alcohol’s Impact on Young People

How does alcohol affect the young?

The papers in our collection focus on the relationship between alcohol and young people from childhood to early adulthood .

Research suggests that even moderate drinking by parents may impact children. At the same time, young children’s familiarity with alcohol may put them at risk of early alcohol initiation.

Our collection goes on to explore alcohol use in adolescence , from neurobiological implications to association with sexual identity and STI risk; and considers a cohort of adolescents and young adults when analysing the relationship of drinking behaviours with social media use and risk of violence respectively.

Finally, we follow trajectories of alcohol use in early adulthood , with articles assessing predictors of Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD), considering the role of gender and age on drinking practices, and examining withdrawal-associated muscle pain hypersensitivity in healthy episodic binge drinkers.

All articles will be free to access and share until the 30th of June, with a view to disseminating scientific knowledge on the impact of alcohol on young people.

Alcohol and Children

From age 4 to 8, children become increasingly aware about normative situations for adults to consume alcohol.

Children aged 4–8 become increasingly knowledgeable about drinking norms in specific situations which implies that they know in what kind of situation alcohol consumption is a common human behavior. This knowledge may put them at risk for early alcohol initiation and frequent drinking later in life.

An Exploration of the Impact of Non-Dependent Parental Drinking on Children

Findings suggest levels of and motivations for parental drinking, as well as exposure to a parent tipsy or drunk, all influence children’s likelihood of experiencing negative outcomes.

Alcohol and Adolescents

Lifetime alcohol use influences the association between future-oriented thought and white matter microstructure in adolescents.

These findings replicate reports of reduced future orientation as a function of greater lifetime alcohol use and demonstrate an association between future orientation and white matter microstructure, in the PCR, a region containing afferent and efferent fibers connecting the cortex to the brain stem, which depends upon lifetime alcohol use.

Differential Alcohol Use Disparities by Sexual Identity and Behavior Among High School Students

Results highlight the need to incorporate multiple methods of sexual orientation measurement into substance use research.

What a Difference a Drink Makes: Determining Associations Between Alcohol-Use Patterns and Condom Utilization Among Adolescents

Results suggest significant increased risk of condomless sex among binge drinking youth. Surprisingly, no significant difference in condom utilization was identified between non-drinkers and only moderate drinkers.

Alcohol and Adolescents and Young Adults

The association between social media use and hazardous alcohol use among youths: a four-country study.

Certain social media platforms might inspire and/or attract hazardously drinking youths, contributing to the growing opportunities for social media interventions.

Change in the Relationship Between Drinking Alcohol and Risk of Violence Among Adolescents and Young Adults: A Nationally Representative Longitudinal Study

Alcohol is most strongly linked to violence among adolescents, so programmes for primary prevention of alcohol-related violence are best targeted towards this age group, particularly males who engage in heavy episodic drinking.

Alcohol and Young Adults

Predictors of alcohol use disorders among young adults: a systematic review of longitudinal studies.

This review suggests that externalizing behaviour is a strong predictor of AUD. The risk of AUD is also high when illicit drug use co-occurs with externalizing behaviour. Environmental factors were influential but changed over time.More evidence is needed to assess the roles of early internalizing behaviour, early drinking onset and other distinctive factors on the development of AUD in young adulthood

Gender-Specific Drinking Contexts Are Associated With Social Harms Resulting From Drinking Among Australian Young Adults at 30 Years

We found that experiences of social harms from drinking at 30 years differ depending on the drinker’s gender and context. Our findings suggest that risky contexts and associated harms are still significant among 30-year-old adults, indicating that a range of gender-specific drinking contexts should be represented in harm reduction campaigns. The current findings also highlight the need to consider gender to inform context-based harm reduction measures and to widen the age target for these beyond emerging adults.

The Role of Sex and Age on Pre-drinking: An Exploratory International Comparison of 27 Countries

This exploratory study aims to model the impact of sex and age on the percentage of pre-drinking in 27 countries, presenting a single model of pre-drinking behaviour for all countries and then comparing the role of sex and age on pre-drinking behaviour between countries. Using data from the Global Drug Survey, the percentages of pre-drinkers were estimated for 27 countries from 64,485 respondents. Bivariate and multivariate multilevel models were used to investigate and compare the percentage of pre-drinking by sex (male and female) and age (16–35 years) between countries.

Hyperalgesia after a Drinking Episode in Young Adult Binge Drinkers: A Cross-Sectional Study

This is the first study to show that alcohol withdrawal-associated muscle hyperalgesia may occur in healthy episodic binge drinkers with only 2–3 years of drinking history, and epinephrine may play a role in binge drinking-associated hyperalgesia.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1464-3502

- Copyright © 2024 Medical Council on Alcohol and Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.14(11); 2022 Nov

Substance Abuse Amongst Adolescents: An Issue of Public Health Significance

1 School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences, Wardha, IND

Sonali G Choudhari

2 School of Epidemiology and Public Health; Community Medicine, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences, Wardha, IND

Sarika U Dakhode

3 Department of Community Medicine, Dr. Panjabrao Deshmukh Memorial Medical College, Amravati, IND

Asmita Rannaware

Abhay m gaidhane.

Adolescence is a crucial time for biological, psychological, and social development. It is also a time when substance addiction and its adverse effects are more likely to occur. Adolescents are particularly susceptible to the negative long-term effects of substance use, including mental health illnesses, sub-par academic performance, substance use disorders, and higher chances of getting addicted to alcohol and marijuana. Over the past few decades, there have been substantial changes in the types of illegal narcotics people consume. The present article deals with the review of substance abuse as a public health problem, its determinants, and implications seen among adolescents. A systematic literature search using databases such as PubMed and Google Scholar was undertaken to search all relevant literature on teenage stimulant use. The findings have been organized into categories to cover essential aspects like epidemiology, neurobiology, prevention, and treatment. The review showed that substance addiction among adolescents between 12 to 19 years is widespread, though national initiatives exist to support young employment and their development. Research on psychological risk factors for teenage substance abuse is vast, wherein conduct disorders, including aggression, impulsivity, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, have been mentioned as risk factors for substance use. Parents' attitudes toward drugs, alcohol, academic and peer pressure, stress, and physical outlook are key determinants. Teenage drug usage has a significant negative impact on users, families, and society as a whole. It was found that a lot has been done to provide correct intervention to those in need with the constant development of programs and rehabilitative centers to safeguard the delicate minds of youths and prevent them from using intoxicants. Still, there is much need for stringent policy and program guidelines to curb this societal menace.

Introduction and background

Drug misuse is a widespread issue; in 2016, 5.6% of people aged 15 to 26 reported using drugs at least once [ 1 ]. Because alcohol and illegal drugs represent significant issues for public health and urgent care, children and adolescents frequently visit emergency rooms [ 2 ]. It is well known that younger people take drugs more often than older adults for most drugs. Drug usage is on the rise in many Association of Southeast Asian Nations, particularly among young males between the ages of 15 and 30 years [ 3 ]. According to the 2013 Global Burden of Disease report, drug addiction is a growing problem among teenagers and young people. Early substance use increases the likelihood of future physical, behavioral, social, and health issues [ 4 ]. Furthermore, recreational drug use is a neglected contributor to childhood morbidity and mortality [ 5 ]. One of the adverse outcomes of adolescent substance use is the increased risk of addiction in those who start smoking, drinking, and taking drugs before they are of 18 years. Moreover, most individuals with Substance Use Disorders begin using substances when they are young [ 6 ]. Substance use disorders amongst adolescents have long-term adverse health effects but can be mitigated with efficient treatment [ 7 ].

Childhood abuse is linked to suicidal thoughts and attempts. The particular mental behavior that mediates the link between childhood trauma and adult suicidal ideation and attempts is yet unknown. Recent studies show teens experiencing suicidal thoughts, psychiatric illness symptoms like anxiety, mood, and conduct disorders, and various types of child maltreatment like sexual abuse, corporal punishment, and emotional neglect that further leads to children inclining toward intoxicants [ 8 ]. Although teen substance use has generally decreased over the past five years, prolonged opioid, marijuana, and binge drinking use are still common among adolescents and young adults [ 9 ]. Drug-using students are more prone to commit crimes, including bullying and violent behavior. It has also been connected to various mental conditions, depending on the substance used. On the other hand, it has been linked to social disorder, abnormal behavior, and association with hostile groups [ 10 ]. Adolescent substance users suffer risks and consequences on the psychological, sociocultural, or behavioral levels that may manifest physiologically [ 11 ]. About 3 million deaths worldwide were caused by alcohol consumption alone. The majority of the 273,000 preventable fatalities linked to alcohol consumption are in India [ 12 ], which is the leading contributor. The United Nations Office on Drug and Crime conducted a national survey on the extent, patterns, and trends of drug abuse in India in 2003, which found that there were 2 million opiate users, 8.7 million cannabis users, and 62.5 million alcohol users in India, of whom 17% to 20% are dependent [ 13 ]. According to prevalence studies, 13.1% of drug users in India are under the age of 20 [ 14 ].

In India, alcohol and tobacco are legal drugs frequently abused and pose significant health risks, mainly when the general populace consumes them. States like Punjab and Uttar Pradesh have the highest rates of drug abuse, and the Indian government works hard to provide them with helpful services that educate and mentor them. This increases the burden of non-communicable illnesses too [ 15 ]. In addition, several substances/drugs are Narcotic and Psychotropic and used despite the act named ‘Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985.

This review article sheds light on ‘substance abuse’ amongst adolescents as an issue of public health significance, its determinants, and its implications on the health and well-being of adolescents.

Methodology

The present article deals with the narrative review of substance abuse as a public health problem, its determinants, and implications seen among adolescents. A systematic literature search using databases such as PubMed and Google Scholar was undertaken to search all relevant literature on teenage stimulant use. The findings have been organized into categories to cover essential aspects like epidemiology, neurobiology, prevention, and treatment. Various keywords used under TiAb of PubMed advanced search were Stimulants, "Drug abuse", "Psychotropic substance", "Substance abuse", addiction, and Adolescents, teenage, children, students, youth, etc., including MeSH terms. Figure Figure1 1 shows the key substances used by youth.

Reasons for abuse

People may initially choose to take drugs for psychological and physical reasons. Psychological issues, including mental illness, traumatic experiences, or even general attitudes and ideas, might contribute to drug usage. Several factors can contribute to emotional and psychosocial stress, compelling one to practice drug abuse. It can be brought on by a loss of a job because of certain reasons, the death of a loved one, a parent's divorce, or financial problems. Even medical diseases and health problems can have a devastating emotional impact. Many take medicines to increase their physical stamina, sharpen their focus, or improve their looks.

Students are particularly prone to get indulged in substance abuse due to various reasons, like academic and peer pressure, the appeal of popularity and identification, readily available pocket money, and relatively easy accessibility of several substances, especially in industrial, urban elite areas, including nicotine (cigarettes) [ 16 , 17 ]. In addition, a relationship breakup, mental illness, environmental factors, self-medication, financial concerns, downtime, constraints of work and school, family obligations, societal pressure, abuse, trauma, boredom, curiosity, experimentation, rebellion, to be in control, enhanced performance, isolation, misinformation, ignorance, instant gratification, wide availability can be one of the reasons why one chooses this path [ 18 ].

The brain grows rapidly during adolescence and continues to do so until early adulthood, as is well documented. According to studies using structural magnetic resonance imaging, changes in cortical grey matter volume and thickness during development include linear and nonlinear transformations and increases in white matter volume and integrity. This delays the maturation of grey and white matter, resulting in poorer sustained attention [ 19 ]. Alcohol drinking excessively increases the likelihood of accidents and other harmful effects by impairing cognitive functions like impulse control and decision-making and motor functions like balance and hand-eye coordination [ 20 ]. Lower-order sensory motor regions of the brain mature first, followed by limbic areas crucial for processing rewards. The development of different brain regions follows different time-varying trajectories. Alcohol exposure has adversely affected various emotional, mental, and social functions in the frontal areas linked to higher-order cognitive functioning that emerge later in adolescence and young adulthood [ 21 ].

Smoking/e-cigarettes

The use of tobacco frequently begins before adulthood. A worryingly high percentage of schoolchildren between 13 and 15 have tried or are currently using tobacco, according to the global youth tobacco survey [ 22 ]. It is more likely that early adolescent cigarette usage will lead to nicotine dependence and adult cigarette use. Teenage smoking has been associated with traumatic stress, anxiety, and mood problems [ 23 ]. Nicotine usage has been associated with a variety of adolescent problems, including sexual risk behaviors, aggressiveness, and the use of alcohol and illegal drugs. High levels of impulsivity have been identified in adolescent smokers.

Additionally, compared to non-smokers, smoking is associated with a higher prevalence of anxiety and mood disorders in teenagers. Smoking is positively associated with suicidal thoughts and attempts [ 24 ]. Peer pressure, attempting something new, and stress management ranked top for current and former smokers [ 25 ]. Most teenagers say that when they start to feel down, they smoke to make themselves feel better and return to their usual, upbeat selves. Smoking may have varying effects on people's moods [ 26 ]. Teenagers who smoke seem more reckless, less able to control their impulses, and less attentive than non-smokers [ 27 ].

Cannabis/Marijuana

Marijuana is among the most often used illegal psychotropic substances in India and internationally. The prevalence of marijuana usage and hospitalizations related to marijuana are rising, especially among young people, according to current trends. Cannabis usage has been connected to learning, working memory, and attention problems. Cannabis has been shown to alleviate stress in small doses, but more significant amounts can cause anxiety, emotional symptoms, and dependence [ 28 ]. Myelination and synaptic pruning are two maturational brain processes that take place during adolescence and the early stages of adulthood. According to reports, these remodeling mechanisms are linked to efficient neural processing. They are assumed to provide the specialized cognitive processing needed for the highest neurocognitive performance. On a prolonged attentional processing test, marijuana usage before age 16 was linked to a shorter reaction time [ 29 ]. Cannabis use alters the endocannabinoid system, impacting executive function, reward function, and affective functions. It is believed that these disturbances are what lead to mental health problems [ 30 ].

MDMA (Ecstasy/Molly)

MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine) was a synthetic drug used legally in psychotherapy treatment throughout the 1970s, despite the lack of data demonstrating its efficacy. Molly, or the phrase "molecular," is typically utilized in powder form. Serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine are produced more significantly when MDMA is used. In the brain, these neurotransmitters affect mood, sleep, and appetite. Serotonin also causes the release of other hormones that may cause emotions of intimacy and attraction. Because of this, users might be more affectionate than usual and possibly develop ties with total strangers. The effects wear off three to six hours later, while a moderate dose may cause withdrawal symptoms to continue for a week. These symptoms include a decline in sex interest, a drop in appetite, problems sleeping, confusion, impatience, anxiety, sorrow, Impulsivity and violence, issues with memory and concentration, and insomnia are a few of them. Unsettlingly, it is rising in popularity in India, particularly among teenagers [ 31 ].

Opium

In addition to being a top producer of illicit opium, India is a significant drug consumer. In India, opium has a long history. The most common behavioral changes are a lack of motivation, depression, hyperactivity, a lack of interest or concentration, mood swings or abrupt behavior changes, confusion or disorientation, depression, anxiety, distortion of reality perception, social isolation, slurred or slow-moving speech, reduced coordination, a loss of interest in once-enjoyed activities, taking from family members or engaging in other illegal activity [ 32 ]. Except for the chemical produced for medicinal purposes, it is imperative to prohibit both production and usage since if a relatively well-governed nation like India cannot stop the drug from leaking, the problem must be huge in scope [ 33 ].

Cocaine is a highly addictive drug that causes various psychiatric syndromes, illnesses, and symptoms. Some symptoms include agitation, paranoia, hallucinations, delusions, violence, and thoughts of suicide and murder. They may be caused by the substance directly or indirectly through the aggravation of co-occurring psychiatric conditions. More frequent and severe symptoms are frequently linked to the usage of cocaine in "crack" form. Cocaine can potentially worsen numerous mental diseases and cause various psychiatric symptoms.

Table Table1 1 discusses the short- and long-term effects of substance abuse.

| Substance | Mode | Behavioral changes | Short-term physical effects | Long-term physical effects |

| Alcohol | Oral/drinking | Growingly aggressive self-disclosure racy sexual behavior [ ]. | Unsteady speech, Drowsiness, Vomiting, Diarrhea, Uneasy stomach, Headache, Breathing problems, Vision and hearing impairment, Faulty judgment, Diminution of perception and coordination, Unconsciousness, Anemia (loss of red blood cells), Coma, and Blackouts [ ]. | Unintentional injuries such as car crashes, falls, burns, drowning; Intentional injuries such as firearm injuries, sexual assault, and domestic violence; Increased on-the-job injuries and loss of productivity; increased family problems and broken relationships. Alcohol poisoning, High blood pressure, Stroke, and other heart-related diseases; Liver disease, Nerve damage, Sexual problems, Permanent damage to the brain [ ]. Vitamin B deficiency can lead to a disorder characterized by amnesia, apathy, and disorientation. Ulcers, Gastritis (inflammation of stomach walls), Malnutrition, Cancer of the mouth and throat [ ]. |

| Cannabis | Smoked, Vaped, Eaten (mixed in food or brewed as tea) | Hallucinations, emotional swings, forgetfulness, Depersonalization, Paranoia, Delusions Disorientation. Psychosis, Bipolar illness, Schizophrenia [ ]. | Enhanced sensory perception and euphoria followed by drowsiness/relaxation; Slowed reaction time; problems with balance and coordination; Increased heart rate and appetite; problems with learning and memory; anxiety. | Mental health problems, Chronic cough, Frequent respiratory infections. |

| Cocaine (coke/crack) | Snorted, smoked, injected | Violence and hostility, paranoia and hallucinations, and monotonous or stereotyped simple conduct [ ]. Suspiciousness anger\giddiness Irritability, and Impatience [ ]. | Narrowed blood vessels; enlarged pupils; increased body temperature, heart rate, and blood pressure; headache; abdominal pain and nausea; euphoria; increased energy, alertness; insomnia, restlessness; anxiety; erratic and violent behavior, panic attacks, paranoia, psychosis; heart rhythm problems, heart attack; stroke, seizure, coma. | Loss of sense of smell, nosebleeds, nasal damage and trouble swallowing from snorting; Infection and death of bowel tissue from decreased blood flow; Poor nutrition and weight loss; Lung damage from smoking. |

| Heroin | Injected, smoked, snorted | Exaggerated efforts to keep family members out of his or her room or being secretive about where he or she goes with friends; drastic changes in behavior and relationships with family and friends; sudden requests for money without a good reason; sudden disinterest in school activities or work; a drop in grades or work performance; a lack of energy and motivation; and lack of interest in clothes are all examples of these behaviors [ ]. | Euphoria; dry mouth; itching; nausea; vomiting; analgesia; slowed breathing and heart rate. | Collapsed veins; abscesses (swollen tissue with pus); infection of the lining and valves in the heart; constipation and stomach cramps; Liver or kidney disease; pneumonia. |

| MDMA | Swallowed, snorted | A state of exhilarated tranquility or peace greater sensitivity -More vigor both physically and emotionally -Increased intimacy and sociability -Relaxation -Bruxism -Empathy [ ]. | Lowered inhibition; enhanced sensory perception; increased heart rate and blood pressure; muscle tension; nausea; faintness; chills or sweating; sharp rise in body temperature leading to kidney failure or death. | Long-lasting confusion, Depression, problems with attention, memory, and Sleep; Increased anxiety, impulsiveness; Less interest in sex. |

| Cigarettes, Vaping devices, e-cigarettes, Cigars, Bidis, Hookahs, Kreteks | Smoked, snorted, chewed, vaporized | Hyperactivity Inattention [ ]. Anxiety, Tension, enhanced emotions, and focus lower rage and stress, relax muscles, and curbs appetite [ ]. | Increased blood pressure, breathing, and heart rate; Exposes lungs to a variety of chemicals; Vaping also exposes the lungs to metallic vapors created by heating the coils in the device. | Greatly increased risk of cancer, especially lung cancer when smoked and oral cancers when chewed; Chronic bronchitis; Emphysema; Heart disease; Leukemia; Cataracts; Pneumonia [ ]. |

Other cheap substances ( sasta nasha ) used in India

India is notorious for phenomena that defy comprehension. People in need may turn to readily available items like Iodex sandwiches, fevibond, sanitizer, whitener, etc., for comfort due to poverty and other circumstances to stop additional behavioral and other changes in youth discouragement is necessary [ 42 - 44 ].

Curbing drug abuse amongst youth

Seventy-five percent of Indian households contain at least one addict. The majority of them are fathers who act in this way due to boredom, stress from their jobs, emotional discomfort, problems with their families, or problems with their spouses. Due to exposure to such risky behaviors, children may try such intoxicants [ 45 ]. These behaviors need to be discouraged because they may affect the child's academic performance, physical growth, etc. The youngster starts to feel depressed, lonely, agitated and disturbed. Because they primarily revolve around educating students about the dangers and long-term impacts of substance abuse, previous attempts at prevention have all been ineffective. To highlight the risks of drug use and scare viewers into abstaining, some programs stoked terror. The theoretical underpinning of these early attempts was lacking, and they failed to consider the understanding of the developmental, social, and other etiologic factors that affect teenage substance use. These tactics are based on a simple cognitive conceptual paradigm that says that people's decisions to use or abuse substances depend on how well they are aware of the risks involved. More effective contemporary techniques are used over time [ 46 ]. School-based substance abuse prevention is a recent innovation utilized to execute changes, including social resistance skills training, normative education, and competence enhancement skills training.

Peer pressure makes a teenager vulnerable to such intoxicants. Teenagers are often exposed to alcohol, drugs, and smoking either because of pressure from their friends or because of being lonely. Social resistance training skills are used to achieve this. The pupils are instructed in the best ways to steer clear of or manage these harmful situations. The best method to respond to direct pressure to take drugs or alcohol is to know what to say (i.e., the specific content of a refusal message) and how to say it. These skills must be taught as a separate curriculum in every school to lower risk. Standard instructional methods include lessons and exercises to dispel misconceptions regarding drug usage's widespread use.

Teenagers typically exaggerate how common it is to smoke, drink, and use particular substances, which could give off the impression that substance usage is acceptable. We can lessen young people's perceptions of the social acceptability of drug use by educating them that actual rates of drug usage are almost always lower than perceived rates of use. Data from surveys that were conducted in the classroom, school, or local community that demonstrate the prevalence of substance use in the immediate social setting may be used to support this information. If not, this can be taught using statistics from national surveys, which usually show prevalence rates that are far lower than what kids describe.

The role social learning processes have in teen drug use is recognized by competency-improvement programs, and there is awareness about how adolescents who lack interpersonal and social skills are more likely to succumb to peer pressure to use drugs. These young people might also be more inclined to turn to drug usage instead of healthier coping mechanisms. Most competency enhancement strategies include instruction in many of the following life skills: general problem-solving and decision-making skills, general cognitive abilities for fending off peer or media pressure, skills for enhancing self-control, adaptive coping mechanisms for reducing stress and anxiety through the use of cognitive coping mechanisms or be behavioral relaxation techniques, and general social and assertive skills [ 46 ].

Programs formulated to combat the growing risk of substance abuse

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare developed Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram for teenagers aged 10 to 19, with a focus on improving nutrition, sexual and reproductive health, mental health, preventing injuries and violence, and preventing substance abuse. By enabling them to make informed and responsible decisions about their health and well-being and ensuring that they have access to the tools and assistance they need, the program seeks to enable all adolescents in India in realizing their full potential [ 47 ].

For the past six years, ‘Nasha Mukti Kendra’ in India and rehabilitation have worked to improve lives and provide treatment for those who abuse alcohol and other drugs. They provide cost-effective and dedicated therapy programs for all parts of society. Patients come to them from all around the nation. Despite having appropriate programs and therapies that can effectively treat the disorder, they do not employ medication to treat addiction.

Conclusions

Around the world, adolescent drug and alcohol addiction has significantly increased morbidity and mortality. The menace of drugs and alcohol has been woven deep into the fabric of society. As its effects reach our youth, India's current generation is at high stake for the risk associated with the abuse of drugs like cannabis, alcohol, and tobacco. Even though the issue of substance abuse is complicated and pervasive, various stakeholders like healthcare professionals, community leaders, and educational institutions have access to a wealth of evidence-based research that can assist them to adopt interventions that can lower rates of teenage substance misuse. It is realized that while this problem is not specific to any one country or culture, individual remedies might not always be beneficial. Due to the unacceptably high rate of drug abuse that is wreaking havoc on humanity, a strategy for addressing modifiable risk factors is crucial. Because human psychology and mental health influence the choices the youth make related to their indulgence in drug misuse, it is the need of the hour to give serious consideration to measures like generating awareness, counseling, student guidance cells, positive parenting, etc., across the world. It will take time to change this substance misuse behavior, but the more effort we put into it, the greater the reward we will reap.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Alcohol's Effects on Health

Research-based information on drinking and its impact.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA)

Make a difference: talk to your child about alcohol - parents.

Quick Facts

Kids who drink are more likely to be victims of violent crime, to be involved in alcohol-related traffic crashes, and to have serious school-related problems.

You have more influence on your child’s values and decisions about drinking before he or she begins to use alcohol.

Parents can have a major impact on their children’s drinking, especially during the preteen and early teen years.

Introduction

With so many drugs available to young people these days, you may wonder, “Why develop a booklet about helping kids avoid alcohol?” Alcohol is a drug, as surely as cocaine and marijuana are. The National Minimum Legal Drinking Age in the United States is 21. And underage drinking is dangerous. Kids who drink are more likely to:

Be victims of violent crime.

Have serious problems in school.

Be involved in drinking-related traffic crashes.

This guide is geared to parents and guardians of young people ages 10 to 14. Keep in mind that the suggestions on the following pages are just that—suggestions. Trust your instincts. Choose ideas you are comfortable with, and use your own style in carrying out the approaches you find useful. Your child looks to you for guidance and support in making life decisions—including the decision not to use alcohol.

“But my child isn’t drinking yet,” you may think. “Isn’t it a little early to be concerned about drinking?” Not at all. This is the age when some children begin experimenting with alcohol. Even if your child is not yet drinking alcohol, he or she may be receiving pressure to drink. Act now. Keeping quiet about how you feel about your child’s alcohol use may give him or her the impression that alcohol use is OK for kids.

It’s not easy. As children approach adolescence, friends exert a lot of influence. Fitting in is a chief priority for teens, and parents often feel shoved aside. Kids will listen, however. Study after study shows that even during the teen years, parents have enormous influence on their children’s behavior.

The bottom line is that most young teens don’t yet drink. And parents’ disapproval of youthful alcohol use is the key reason children choose not to drink. So make no mistake: You can make a difference.

(Note: This booklet uses a variety of terms to refer to young people ages 10 to 14, including youngsters, children, kids, and young teens.)

Young Teens and Alcohol: The Risks

For young people, alcohol is the drug of choice. In fact, alcohol is used by more young people than tobacco or illicit drugs. Although most children under age 14 have not yet begun to drink, early adolescence is a time of special risk for beginning to experiment with alcohol.

While some parents and guardians may feel relieved that their teen is “only” drinking, it is important to remember that alcohol is a powerful, mood-altering drug. Not only does alcohol affect the mind and body in often unpredictable ways, but teens lack the judgment and coping skills to handle alcohol wisely. As a result:

Alcohol-related traffic crashes are a major cause of death among young people. Alcohol use also is linked with teen deaths by drowning, suicide, and homicide.

Teens who use alcohol are more likely to be sexually active at earlier ages, to have sexual intercourse more often, and to have unprotected sex than teens who do not drink.

Young people who drink are more likely than others to be victims of violent crime, including rape, aggravated assault, and robbery.

Teens who drink are more likely to have problems with school work and school conduct.

The majority of boys and girls who drink tend to binge when they drink.

A person who begins drinking as a young teen is four times more likely to develop alcohol dependence than someone who waits until adulthood to use alcohol.

The message is clear: Alcohol use is unsafe for young people. And the longer children delay alcohol use, the less likely they are to develop any problems associated with it. That’s why it is so important to help your child avoid any alcohol use.

What is binge drinking?

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) defines binge drinking as a pattern of drinking that brings blood alcohol concentration (BAC) to 0.08 percent—or 0.08 grams of alcohol per deciliter—or higher.* For a typical adult, this pattern corresponds to consuming 4 or more drinks (female), or 5 or more drinks (male), in about 2 hours. Research shows that fewer drinks in the same timeframe result in the same BAC in youth; only 3 drinks for girls, and 3 to 5 drinks for boys, depending on their age and size.

*A BAC of 0.08 percent corresponds to 0.08 grams per deciliter, or 0.08 grams per 100 milliliters.

Your Young Teen's World

Early adolescence is a time of immense and often confusing changes for your son or daughter, which makes it a challenging time for both your youngster and you. Understanding what it’s like to be a teen can help you stay closer to your child and have more influence on the choices he or she makes—including decisions about using alcohol.

Changes in the Brain. Research shows that as a child matures, his or her brain continues to develop too. In fact, the brain’s final, adult wiring may not even be complete until well into the twenties. Furthermore, in some ways, the adolescent brain may be specifically “wired” to help youth navigate adolescence and to take some of the risks necessary to achieve independence from their parents. This may help explain why teens often seek out new and thrilling—sometimes dangerous—situations, including drinking alcohol. It also offers a possible reason for why young teens act so impulsively, often not recognizing that their actions—such as drinking—can lead to serious problems.

Growing Up and Fitting In. As children approach adolescence, “fitting in” becomes extremely important. They begin to feel more self-conscious about their bodies than they did when they were younger and begin to wonder whether they are “good enough”—tall enough, slender enough, attractive enough—compared with others. They look to friends and the media for clues on how they measure up, and they begin to question adults’ values and rules. It’s not surprising that this is the time when parents often experience conflict with their kids. Respecting your child’s growing independence while still providing support and setting limits is a key challenge during this time.

A young teen who feels that he or she doesn’t fit in is more likely to do things to try to please friends, including experimenting with alcohol. During this vulnerable time, it is particularly important to let your children know that in your eyes, they do measure up—and that you care about them deeply.

Did You Know?

That according to a recent national survey, 16 percent of eighth graders reported drinking alcohol within the past month?

That 32 percent of eighth graders reported drinking in the past year?

That 64 percent of eighth graders say that alcohol is easy to get?

That a recent survey shows that more girls than boys ages 12 to 17 reported drinking alcohol?

The Bottom Line: A Strong Parent–Child Relationship

You may wonder why a guide for preventing teen alcohol use is putting so much emphasis on parents’ need to understand and support their children. But the fact is, the best way to influence your child to avoid drinking is to have a strong, trusting relationship with him or her. Research shows that teens are much more likely to delay drinking when they feel they have a close, supportive tie with a parent or guardian. Moreover, if your son or daughter eventually does begin to drink, a good relationship with you will help protect him or her from developing alcohol-related problems.

The opposite also is true: When the relationship between a parent and teen is full of conflict or is very distant, the teen is more likely to use alcohol and to develop drinking-related problems.

This connection between the parent–child relationship and a child’s drinking habits makes a lot of sense when you think about it. First, when children have a strong bond with a parent, they are apt to feel good about themselves and therefore be less likely to give in to peer pressure to use alcohol. Second, a good relationship with you is likely to encourage your children to try to live up to your expectations, because they want to maintain their close tie with you. Here are some ways to build a strong, supportive bond with your child:

Establish open communication. Make it easy for your teen to talk honestly with you. (See box “Tips for Talking With Your Teen.”)

Show you care. Even though young teens may not always show it, they still need to know that they are important to their parents. Make it a point to regularly spend one-on-one time with your child—time when you can give him or her your loving, undivided attention. Some activities to share: a walk, a bike ride, a quiet dinner out, or a cookie-baking session.

Draw the line. Set clear, realistic expectations for your child’s behavior. Establish appropriate consequences for breaking rules and consistently enforce them.

Offer acceptance. Make sure your teen knows that you appreciate his or her efforts as well as accomplishments. Avoid hurtful teasing or criticism.

Understand that your child is growing up. This doesn’t mean a hands-off attitude. But as you guide your child’s behavior, also make an effort to respect his or her growing need for independence and privacy.

Tips For Talking With Your Teen

Developing open, trusting communication between you and your child is essential to helping him or her avoid alcohol use. If your child feels comfortable talking openly with you, you’ll have a greater chance of guiding him or her toward healthy decisionmaking. Some ways to begin:

Encourage conversation. Encourage your child to talk about whatever interests him or her. Listen without interruption and give your child a chance to teach you something new. Your active listening to your child’s enthusiasms paves the way for conversations about topics that concern you.

Ask open-ended questions. Encourage your teen to tell you how he or she thinks and feels about the issue you’re discussing. Avoid questions that have a simple “yes” or “no” answer.

Control your emotions. If you hear something you don’t like, try not to respond with anger. Instead, take a few deep breaths and acknowledge your feelings in a constructive way.

Make every conversation a “win-win” experience. Don’t lecture or try to “score points” on your teen by showing how he or she is wrong. If you show respect for your child’s viewpoint, he or she will be more likely to listen to and respect yours.

Good Reasons For Teens Not To Drink

You want your child to avoid alcohol.

You want your child to maintain self-respect.

The National Minimum Legal Drinking Age is 21.

Drinking at their age can be dangerous.

You may have a family history of alcoholism.

Talking With Your Teen About Alcohol

For many parents, bringing up the subject of alcohol is no easy matter. Your young teen may try to dodge the discussion, and you yourself may feel unsure about how to proceed. To make the most of your conversation, take some time to think about the issues you want to discuss before you talk with your child. Consider too how your child might react and ways you might respond to your youngster’s questions and feelings. Then choose a time to talk when both you and your child have some “down time” and are feeling relaxed.

You don’t need to cover everything at once. In fact, you’re likely to have a greater impact on your child’s decisions about drinking by having a number of talks about alcohol use throughout his or her adolescence. Think of this talk with your child as the first part of an ongoing conversation.

And remember, do make it a conversation, not a lecture! You might begin by finding out what your child thinks about alcohol and drinking.

Your Child’s Views About Alcohol. Ask your young teen what he or she knows about alcohol and what he or she thinks about teen drinking. Ask your child why he or she thinks kids drink. Listen carefully without interrupting. Not only will this approach help your child to feel heard and respected, but it can serve as a natural “lead-in” to discussing alcohol topics.

Important Facts About Alcohol. Although many kids believe that they already know everything about alcohol, myths and misinformation abound. Here are some important facts to share:

Alcohol is a powerful drug that slows down the body and mind. It impairs coordination; slows reaction time; and impairs vision, clear thinking, and judgment.

Beer and wine are not “safer” than distilled spirits (gin, rum, tequila, vodka, whiskey, etc.). A 12-ounce can of beer (about 5 percent alcohol), a 5-ounce glass of wine (about 12 percent alcohol), and 1.5 ounces of 80-proof distilled spirits (40 percent alcohol) all contain the same amount of alcohol and have the same effects on the body and mind.

On average, it takes 2 to 3 hours for a single drink to leave a person’s system. Nothing can speed up this process, including drinking coffee, taking a cold shower, or “walking it off.”

People tend to be very bad at judging how seriously alcohol has affected them. That means many individuals who drive after drinking think they can control a car—but actually cannot.

Anyone can develop a serious alcohol problem, including a teenager.

Good Reasons Not to Drink. In talking with your child about reasons to avoid alcohol, stay away from scare tactics. Most young teens are aware that many people drink without problems, so it is important to discuss the consequences of alcohol use without overstating the case. Some good reasons why teens should not drink:

You want your child to avoid alcohol. Clearly state your own expectations about your child’s drinking. Your values and attitudes count with your child, even though he or she may not always show it.

To maintain self-respect. Teens say the best way to persuade them to avoid alcohol is to appeal to their self-respect—let them know that they are too smart and have too much going for them to need the crutch of alcohol. Teens also are likely to pay attention to examples of how alcohol might lead to embarrassing situations or events—things that might damage their self-respect or alter important relationships.

The National Minimum Legal Drinking Age is 21. Getting caught with alcohol before age 21 may mean trouble with the authorities. Even if getting caught doesn’t lead to police action, the parents of your child’s friends may no longer permit them to associate with your child.

Drinking can be dangerous. One of the leading causes of teen deaths is motor vehicle crashes involving alcohol. Drinking also makes a young person more vulnerable to sexual assault and unprotected sex. And while your teen may believe he or she wouldn’t engage in hazardous activities after drinking, point out that because alcohol impairs judgment, a drinker is very likely to think such activities won’t be dangerous.

You have a family history of alcoholism. If one or more members of your family has suffered from alcoholism, your child may be somewhat more vulnerable to developing a drinking problem.

Alcohol affects young people differently than adults. Drinking while the brain is still maturing may lead to long-lasting intellectual effects and may even increase the likelihood of developing alcohol dependence later in life.

The “Magic Potion” Myth. The media’s glamorous portrayal of alcohol encourages many teens to believe that drinking will make them “cool,” popular, attractive, and happy. Research shows that teens who expect such positive effects are more likely to drink at early ages. However, you can help to combat these dangerous myths by watching TV shows and movies with your child and discussing how alcohol is portrayed in them. For example, television advertisements for beer often show young people having an uproariously good time, as though drinking always puts people in a terrific mood. Watching such a commercial with your child can be an opportunity to discuss the many ways that alcohol can affect people—in some cases bringing on feelings of sadness or anger rather than carefree high spirits.

How to Handle Peer Pressure. It’s not enough to tell your young teen that he or she should avoid alcohol—you also need to help your child figure out how. What can your daughter say when she goes to a party and a friend offers her a beer? (See “Help Your Child Say No.”) Or what should your son do if he finds himself in a home where kids are passing around a bottle of wine and parents are nowhere in sight? What should their response be if they are offered a ride home with an older friend who has been drinking?

Brainstorm with your teen for ways that he or she might handle these and other difficult situations, and make clear how you are willing to support your child. An example: “If you find yourself at a home where kids are drinking, call me and I’ll pick you up—and there will be no scolding or punishment.” The more prepared your child is, the better able he or she will be to handle high-pressure situations that involve drinking.

Mom, Dad, Did You Drink When You Were a Kid?

This is the question many parents dread—yet it is highly likely to come up in any family discussion of alcohol. The reality is that some parents did drink when they were underage. So how can one be honest with a child without sounding like a hypocrite who advises, “Do as I say, not as I did”?

This is a judgment call. If you believe that your drinking or drug use history should not be part of the discussion, you can simply tell your child that you choose not to share it. Another approach is to admit that you did do some drinking as a teenager, but that it was a mistake—and give your teen an example of an embarrassing or painful moment that occurred because of your drinking. This approach may help your child better understand that youthful alcohol use does have negative consequences.

How To Host A Teen Party

Agree on a guest list—and don’t admit party crashers.

Discuss ground rules with your child before the party.

Encourage your teen to plan the party with a responsible friend so that he or she will have support if problems arise.

Brainstorm fun activities for the party.

If a guest brings alcohol into your house, ask him or her to leave.

Serve plenty of snacks and non-alcoholic drinks.

Be visible and available—but don’t join the party!

Taking Action: Prevention Strategies for Parents

While parent–child conversations about not drinking are essential, talking isn’t enough—you also need to take concrete action to help your child resist alcohol. Research strongly shows that active, supportive involvement by parents and guardians can help teens avoid underage drinking and prevent later alcohol misuse.

In a recent national survey, 64 percent of eighth graders said alcohol was “fairly easy” or “very easy” to get and 32 percent reported drinking within the last year. The message is clear: Young teens still need plenty of adult supervision. Some ways to provide it:

Monitor Alcohol Use in Your Home. If you keep alcohol in your home, keep track of the supply. Make it clear to your child that you don’t allow unchaperoned parties or other teen gatherings in your home. If possible, however, encourage him or her to invite friends over when you are at home. The more entertaining your child does in your home, the more you will know about your child’s friends and activities.

Connect With Other Parents. Getting to know other parents and guardians can help you keep closer tabs on your child. Friendly relations can make it easier for you to call the parent of a teen who is having a party to be sure that a responsible adult will be present and that alcohol will not be available. You’re likely to find out that you’re not the only adult who wants to prevent teen alcohol use—many other parents share your concern.

Keep Track of Your Child’s Activities. Be aware of your teen’s plans and whereabouts. Generally, your child will be more open to your supervision if he or she feels you are keeping tabs because you care, not because you distrust him or her.

Develop Family Rules About Youthful Drinking. When parents establish clear “no alcohol” rules and expectations, their children are less likely to begin drinking. Although each family should develop agreements about teen alcohol use that reflect their own beliefs and values, some possible family rules about drinking are:

Kids will not drink alcohol until they are 21.

Older siblings will not encourage younger brothers or sisters to drink and will not give them alcohol.

Kids will not stay at teen parties where alcohol is served.

Kids will not ride in a car with a driver who has been drinking.

Set a Good Example. Parents and guardians are important role models for their children—even children who are fast becoming teenagers. Studies indicate that if a parent uses alcohol, his or her children are more likely to drink as well. But even if you use alcohol, there may be ways to lessen the likelihood that your child will drink. Some suggestions:

Use alcohol in moderation.

Don’t communicate to your child that alcohol is a good way to handle problems. For example, don’t come home from work and say, “I had a rotten day. I need a drink.”

Let your child see that you have other, healthier ways to cope with stress, such as exercise; listening to music; or talking things over with your spouse, partner, or friend.

Don’t tell your kids stories about your own drinking in a way that conveys the message that alcohol use is funny or glamorous.

Never drink and drive or ride in a car with a driver who has been drinking.

When you entertain other adults, serve alcohol-free beverages and plenty of food. If anyone drinks too much at your party, make arrangements for them to get home safely.

Help Your Child Say No

Your child can learn to resist alcohol or anything else he or she may feel pressured into. Let him or her know that the best way to say “no” is to be assertive—that is, say no and mean it.

Resist The Pressure To Drink

Say no and let them know you mean it.

Stand up straight.

Make eye contact.

Say how you feel.

Don’t make excuses.

Stand up for yourself.

Don’t Support Teen Drinking. Your attitudes and behavior toward teen drinking also influence your child. Avoid making jokes about underage drinking or drunkenness, or otherwise showing acceptance of teen alcohol use. Never serve alcohol to your child’s underage friends. Research shows that kids whose parents or friends’ parents provide alcohol for teen get-togethers are more likely to engage in heavier drinking, to drink more often, and to get into traffic crashes. Remember, too, that in almost every State it is illegal to provide alcohol to minors who are not family members.

Help Your Child Build Healthy Friendships. If your child’s friends use alcohol, your child is more likely to drink too. So it makes sense to try to encourage your young teen to develop friendships with kids who do not drink and who are otherwise healthy influences on your child. A good first step is to simply get to know your child’s friends better. You can then invite the kids you feel good about to family get-togethers and outings and find other ways to encourage your child to spend time with those teens. Also, talk directly with your child about the qualities in a friend that really count, such as trustworthiness and kindness, rather than popularity or a “cool” style.

When you disapprove of one of your child’s friends, the situation can be tougher to handle. While it may be tempting to simply forbid your child to see that friend, such a move may make your child even more determined to hang out with him or her. Instead, you might try pointing out your reservations about the friend in a caring, supportive way. You can also limit your child’s time with that friend through your family rules, such as how after-school time can be spent or how late your child can stay out in the evening.

Encourage Healthy Alternatives to Alcohol. One reason kids drink is to beat boredom. So it makes sense to encourage your child to participate in supervised after-school and weekend activities that are challenging and fun. According to a recent survey of preteens, the availability of enjoyable, alcohol-free activities is a big reason for deciding not to use alcohol.

If your community doesn’t offer many supervised activities, consider getting together with other parents and teens to help create some. Start by asking your child and other kids what they want to do, because they will be most likely to participate in activities that truly interest them. Find out whether your church, school, or community organization can help you sponsor a project.

Could My Child Develop a Drinking Problem?

This booklet is primarily concerned with preventing teen alcohol use. We also need to pay attention to the possibility of youthful alcohol abuse. Certain children are more likely than others to drink heavily and encounter alcohol-related difficulties, including health, school, legal, family, and emotional problems. Kids at highest risk for alcohol-related problems are those who:

Begin using alcohol or other drugs before the age of 15.

Have a parent who is a problem drinker or an alcoholic.

Have close friends who use alcohol and/or other drugs.

Have been aggressive, antisocial, or hard to control from an early age.

Have experienced childhood abuse and/or other major traumas.

Have current behavioral problems and/or are failing at school.

Have parents who do not support them, do not communicate openly with them, and do not keep track of their behavior or whereabouts.

Experience ongoing hostility or rejection from parents and/or harsh, inconsistent discipline.

The more of these experiences a child has had, the greater the chances that he or she will develop problems with alcohol. Having one or more risk factors does not mean that your child definitely will develop a drinking problem, but it does suggest that you may need to act now to help protect your youngster from later problems.

Talking with your child is more important now than ever. If your child has serious behavioral problems, you may want to seek help from his or her school counselor, physician, and/or a mental health professional. And if you suspect that your child may be in trouble with drinking, consider getting advice from a health care professional specializing in alcohol problems before talking with your teen (see box “Warning Signs of a Drinking Problem”). To find a professional, contact your family doctor or a local hospital. Other sources of information and guidance may be found in your local Yellow Pages under “Alcoholism” or through one of the resources listed at the end of this booklet.

Warning Signs Of A Drinking Problem

Although the following signs may indicate a problem with alcohol or other drugs, some also reflect normal teenage growing pains. Experts believe that a drinking problem is more likely if you notice several of these signs at the same time, if they occur suddenly, and if some of them are extreme in nature.

Mood changes: flare-ups of temper, irritability, and defensiveness.

School problems: poor attendance, low grades, and/or recent disciplinary action.

Rebelling against family rules.

Switching friends, along with a reluctance to have you get to know the new friends.

A “nothing matters” attitude: sloppy appearance, a lack of involvement in former interests, and general low energy.

Finding alcohol in your child’s room or backpack, or smelling alcohol on his or her breath.

Physical or mental problems: memory lapses, poor concentration, bloodshot eyes, lack of coordination, or slurred speech.

Action Checklist

Establish a loving, trusting relationship with your child.

Make it easy for your teen to talk honestly with you.

Talk with your child about alcohol facts, reasons not to drink, and ways to avoid drinking in difficult situations.

Keep tabs on your young teen’s activities, and join with other parents in making common policies about teen alcohol use.

Develop family rules about teen drinking and establish consequences.

Set a good example regarding your own alcohol use and your response to teen drinking.

Encourage your child to develop healthy friendships and fun alternatives to drinking.

Know whether your child is at high risk for a drinking problem; if so, take steps to lessen that risk.

Know the warning signs of a teen drinking problem and act promptly to get help for your child.

Believe in your own power to help your child avoid alcohol use.

Partnership to End Addiction 485 Lexington Avenue, 3rd Floor New York, NY 10017-6706 212–841–5200 Internet address: https://drugfree.org/

A national resource working to reduce teen substance abuse and to support families impacted by addiction.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Publications Distribution Center P.O. Box 10686 Rockville, MD 20849–0686 301–443–3860 Internet address: http://www.niaaa.nih.gov

Makes available free informational materials on many aspects of alcohol use, alcohol abuse, and alcoholism.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration National Drug Information Treatment and Referral Hotline 800–662–HELP (4357) (toll free) Internet address: https://www.samhsa.gov/find-treatment

Provides information, support, treatment options, and referrals to local rehab centers for drug or alcohol problems. Operates 24 hours, 7 days a week.

To download or order, visit https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications .

Or write to:

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Publications Distribution Center P.O. Box 10686, Rockville, MD 20849–0686

niaaa.nih.gov

An official website of the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

Alcohol Among the Youth

How it works

Alcohol has always been around us even at a young age we see it everywhere and are allured by the concept of alcohol. The popularity of drinking alcohol starts to happen in 8th grade and 39% of students have tried alcohol (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2012). Students who have problems at home or who might feel the need to find an escape which is alcohol. In middle school, a student who identifies as a bully are three to five times more likely to drink alcohol (deBry & Tiffany, 2008; King & Chassin, 2007; Zucker et al.

, 2006). If this trend keeps persisting during the student’s earlier years this can lead to adulthood. Impaired social adjustments may be traced back to early parent-child attachments, and victimization and bullying perpetration may reflect dissatisfying interpersonal bonds early in development (Lereya, Samara, & Wolke, 2013). Living in a society where technology is striving, there is another form of aggression that has formed called cyberbullying which is hard to tackle. Mostly cyberbullying work has focused on more middle and high school students, with popularity rating ranging from twenty to forty percent (Selkie, E.). This type of bullying reports to have suicidal thoughts and feel depressed.

The Consequence of Drinking

The consequence that comes can have a major impact on those who drink alcohol irresponsibly. An article called “Cyberbullying, depression, and problem alcohol use in female college students” states, that thirty percent of college students are reported to have a diagnosis of depression. Also, sixty five percent of college students consume alcohol in any given month, and half of those students binge drink (Selkie, E.). According to (Pedrelli, P.), some large-scale national surveys have shown that nearly half (44%) of college students are binge drinkers [1–3] and that 22.7% binge frequently [4]. It has become so popular that it is part of the culture to drink. However, this is affecting the students’ performance at school which can lead to depression. Moreover, adolescent substance use is related to social and academic problems, such as academic failure and lower educational achievement (Crosnoe 2006; Latvala et al. 2014). The article called “Gender, Depressive Symptoms and Patterns of Alcohol Use among College Students” said it found that college students meeting criteria for alcohol abuse were 3.6 times more likely to have a history of major depressive disorder than their peers who did not meet criteria for alcohol abuse (Pedrelli, P.).

This is a lot more common in female students compared to males. Another issue that students go through is peer pressure. For example, peer victimization may lead to social anxiety and depressive symptoms (e.g., Hamilton et al. 2013; Landoll et al. 2013; Siegel et al. 2009; Thompson and Leadbeater 2012) and, in turn, social anxiety and negative affect may lead to greater substance use (e.g., Mason et al. 2009; Zehe et al. 2013). Anxiety can hinder college student’s concentration and social skills in school. To reduce the psychological and physical anxiety symptoms, students have the capability to drink alcohol a lot more easily because of the anxiolytic properties (Keyes, Hatzenbuehler, & Hasin, 2011; Low, Lee, Johnson, Williams, & Harris, 2008). In addition, the article called, “Correlation between anxiety and alcohol consumption among college students,” by Silva, E. C., & Tucci, A. M. (2018) says that 6.5% of students drink alcohol to reduce the symptoms of anxiety. The goal of this study was to examine further the use of alcohol among students and how that affects their behavior such as having low self-esteem and anxiety. This study took place in a university with a handful of students answering a survey.

Cite this page

Alcohol Among the Youth. (2020, Apr 23). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/alcohol-among-the-youth/

"Alcohol Among the Youth." PapersOwl.com , 23 Apr 2020, https://papersowl.com/examples/alcohol-among-the-youth/

PapersOwl.com. (2020). Alcohol Among the Youth . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/alcohol-among-the-youth/ [Accessed: 22 Jun. 2024]

"Alcohol Among the Youth." PapersOwl.com, Apr 23, 2020. Accessed June 22, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/alcohol-among-the-youth/

"Alcohol Among the Youth," PapersOwl.com , 23-Apr-2020. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/alcohol-among-the-youth/. [Accessed: 22-Jun-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2020). Alcohol Among the Youth . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/alcohol-among-the-youth/ [Accessed: 22-Jun-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

- Open access

- Published: 07 November 2021

How to prevent alcohol and illicit drug use among students in affluent areas: a qualitative study on motivation and attitudes towards prevention

- Pia Kvillemo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9706-4902 1 ,

- Linda Hiltunen 2 ,

- Youstina Demetry 3 ,

- Anna-Karin Carlander 4 ,

- Tim Hansson 5 ,

- Johanna Gripenberg 1 ,

- Tobias H. Elgán 1 ,

- Kim Einhorn 4 &

- Charlotte Skoglund 1 , 4

Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy volume 16 , Article number: 83 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

13k Accesses

5 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

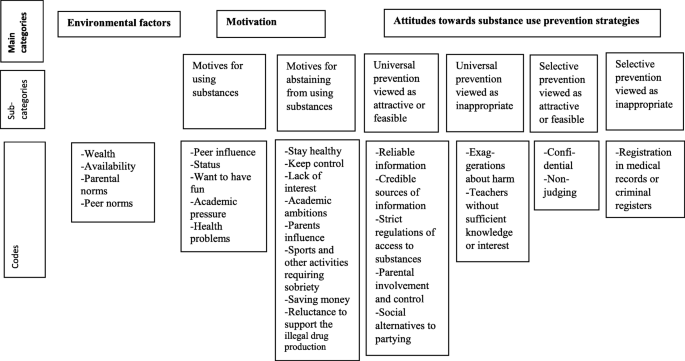

The use of alcohol and illicit drugs during adolescence can lead to serious short- and long-term health related consequences. Despite a global trend of decreased substance use, in particular alcohol, among adolescents, evidence suggests excessive use of substances by young people in socioeconomically affluent areas. To prevent substance use-related harm, we need in-depth knowledge about the reasons for substance use in this group and how they perceive various prevention interventions. The aim of the current study was to explore motives for using or abstaining from using substances among students in affluent areas as well as their attitudes to, and suggestions for, substance use prevention.

Twenty high school students (age 15–19 years) in a Swedish affluent municipality were recruited through purposive sampling to take part in semi-structured interviews. Qualitative content analysis of transcribed interviews was performed.

The most prominent motive for substance use appears to be a desire to feel a part of the social milieu and to have high social status within the peer group. Motives for abstaining included academic ambitions, activities requiring sobriety and parental influence. Students reported universal information-based prevention to be irrelevant and hesitation to use selective prevention interventions due to fear of being reported to authorities. Suggested universal prevention concerned reliable information from credible sources, stricter substance control measures for those providing substances, parental involvement, and social leisure activities without substance use. Suggested selective prevention included guaranteed confidentiality and non-judging encounters when seeking help.

Conclusions

Future research on substance use prevention targeting students in affluent areas should take into account the social milieu and with advantage pay attention to students’ suggestions on credible prevention information, stricter control measures for substance providers, parental involvement, substance-free leisure, and confidential ways to seek help with a non-judging approach from adults.

Alcohol consumption and illicit drug use are major public health concerns causing great individual suffering as well as substantial societal costs [ 1 , 2 ]. Early onset of substance use is especially problematic since the developing brain is vulnerable to the effects of alcohol and drugs, increasing the risk of long-term negative effects, such as harmful use, addiction, and mental health problems [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]. Short-term consequences of substance use include intoxication [ 5 , 7 ], accidents [ 8 [, academic failure [ 9 ], and interaction with legal authorities [ 10 ], which calls for effective substance use prevention in adolescents and young adults. Such prevention interventions may be universal, targeting the general population, e.g., legal measures and school based programs, or selective, targeting certain vulnerable at-risk groups, i.e., subsections of the population [ 11 ]. Selective prevention can be carried out within a universal prevention setting, such as health care or school, but also be delivered directly to the group which it aims to target, face-to-face or digitally [ 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ].

The motives to use substances are governed by a number of personal, social and environmental factors [ 16 ], ranging from personal knowledge, abilities, beliefs and attitudes, to the influence of family, friends and society [ 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ]. Cooper and colleagues [ 21 ] have previously identified a number of motives for drinking, i.e., 1) enhancement (drinking to maintain or amplify positive affect), 2) coping (drinking to avoid or dull negative affect), 3) social (drinking to improve parties or gatherings), and 4) conformity (drinking due to social pressure or a need to fit in). Similar motives for illicit drug use have been found by e.g. Kettner and colleagues, who highlighted the attainment of euphoria and enhancement of activities as prominent motives for use of psychoactive substances among people using psychedelics in parallel with other substances [ 22 ], along with Boys and colleagues [ 23 , 24 , 25 ], who reported on changing mood (e.g., to stop worrying about a problem) and social purposes (e.g., to enjoy the company of friends) as motives for using illicit drugs among young people. Additionally, the authors found that the facilitation of activities (e.g., to concentrate, to work/study), physical effects (e.g., to lose weight), and the managing of the effects of other substances (e.g., to ease or improve) motivated young people to use illicit drugs.

Prior research has repeatedly shown that low socioeconomic status is a risk factor for substance use and related problems [ 26 , 27 , 28 ]. However, recent research from Canada [ 29 ], the United States [ 30 , 31 , 32 ], Serbia [ 33 ], Switzerland [ 34 ], and Sweden [ 35 ] suggest that high socioeconomic status too is associated with excessive substance use among young people, although for other reasons [ 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ]. Previous research has highlighted two main explanations for excessive substance use among young people in families with high socioeconomic status; i) exceptionally high requirements to perform in both school and leisure activities and ii) absence of adult contact, emotionally and physically, due to parents in resourceful and affluent areas spending a lot of time on their work and careers [ 36 , 37 ]. In addition to these explanations, high physical and social availability due to substantial economic resources and a social milieu were substance use is a natural element, may enable extensive substance use among economically privileged young people [ 30 , 38 , 39 ].

In parallel with identification of various groups at risk for extensive substance use, a growing number of young people globally abstain from using substances [ 1 , 40 , 41 ]. By analyzing data derived from a nationally representative sample of American high school students, Levy and colleagues [ 40 ] found an increasing percentage of 12th-graders reporting no current (past 30 days) substance use between 1976 and 2014, showing that a growing proportion of high school students are motivated to abstain from substance use. However, while this global decrease in substance use among adolescents is mirrored in Swedish youths, in particular alcohol use, a more detailed investigation shows large discrepancies across different socioeconomic and geographic areas. Affluent areas in Sweden stand out as breaking the trend, showing increasing alcohol and illicit drug use among adolescents [ 42 , 43 ].