Celebrating 150 years of Harvard Summer School. Learn about our history.

14 Tips for Test Taking Success

Worried about getting through your next big exam? Here are 14 test taking strategies that can help you do your best on your next test.

Mary Sharp Emerson

From pop quizzes to standardized tests, exams are an important part of the life of every high school student.

The best way to ensure that you’ll get the grade you want is to understand the material thoroughly. Good test taking skills, however, can help make the difference between a top grade and an average one. Mastering these skills can also help reduce stress and relieve test-taking anxiety.

In this blog, we’ve divided our tips for test taking into two categories: seven things you can do to prepare for your next exam and seven things you should do once the test begins. We’ve also included four strategies that can help with test taking anxiety.

We hope these test taking tips will help you succeed the next time you are facing an exam, big or small!

Seven Best Strategies for Test Prep

You’ve probably heard the quote (originally credited to Alexander Graham Bell): “Preparation is the key to success.”

When it comes to test taking, these are words to live by.

Here are the seven best things you can do to make sure you are prepared for your next test.

1. Cultivate Good Study Habits

Understanding and remembering information for a test takes time, so developing good study habits long before test day is really important.

Do your homework assignments carefully, and turn them in on time. Review your notes daily. Write out your own study guides. Take advantage of any practice tests your teacher gives you, or even create your own.

These simple steps, when done habitually, will help ensure that you really know your stuff come test day.

2. Don’t “Cram”

It might seem like a good idea to spend hours memorizing the material you need the night before the test.

In fact, cramming for a test is highly counterproductive. Not only are you less likely to retain the information you need, cramming also increases stress, negatively impacts sleep, and decreases your overall preparedness.

So avoid the temptation to stay up late reviewing your notes. Last minute cramming is far less likely to improve your grade than developing good study habits and getting a good night’s sleep.

3. Gather Materials the Night Before

Before going to bed (early, so you get a good night’s sleep), gather everything you need for the test and have it ready to go.

Having everything ready the night before will help you feel more confident and will minimize stress on the morning of the test. And it will give you a few extra minutes to sleep and eat a healthy breakfast.

4. Get a Good Night’s Sleep

And speaking of sleep…showing up to your test well-rested is one of the best things you can do to succeed on test day.

Why should you make sleep a priority ? A good night’s sleep will help you think more clearly during the test. It will also make it easier to cope with test-taking stress and anxiety. Moreover, excellent sleep habits have been shown to consolidate memory and improve academic performance, as well as reduce the risk of depression and other mental health disorders.

5. Eat a Healthy Breakfast

Like sleeping, eating is an important part of self-care and test taking preparation. After all, it’s hard to think clearly if your stomach is grumbling.

As tough as it can be to eat when you’re nervous or rushing out the door, plan time in your morning on test day to eat a healthy breakfast.

A mix of complex carbohydrates and healthy protein will keep you feeling full without making you feel sluggish. Whole wheat cereal, eggs, oatmeal, berries, and nuts may be great choices (depending on your personal dietary needs and preferences). It’s best to avoid foods that are high in sugar, as they can give you a rush of energy that will wear off quickly, leaving you feeling tired.

And don’t forget to drink plenty of water. If possible, bring a bottle of water with you on test day.

6. Arrive Early

Arriving early at a test location can help decrease stress. And it allows you to get into a positive state of mind before the test starts.

Choose your seat as soon as possible. Organize your materials so they are readily available when you need them. Make sure you are physically comfortable (as much as possible).

By settling in early, you are giving yourself time to get organized, relaxed, and mentally ready for the test to begin. Even in a high school setting, maximizing the time you have in the test classroom—even if it’s just a couple of minutes—can help you feel more comfortable, settled, and focused before the test begins.

7. Develop Positive Rituals

Don’t underestimate the importance of confidence and a positive mindset in test preparation.

Positive rituals can help combat negative thinking, test anxiety, and lack of focus that can easily undermine your success on test day. Plan some extra time to go for a short walk or listen to your favorite music. Engage in simple breathing exercises. Visualize yourself succeeding on the test.

Your rituals can be totally unique to you. The important thing is developing a calming habit that will boost your confidence, attitude, and concentration when the test begins.

Explore College Programs for High School Students at Harvard Summer School.

Seven Best Test-Taking Tips for Success

You have gotten a good night’s sleep, eaten a healthy breakfast, arrived early, and done your positive test-day ritual. You are ready to start the test!

Different types of tests require different test taking strategies. You may not want to approach a math test the same way you would an essay test, for example. And some computerized tests such as SATs require you to work through the test in a specific way.

However, there are some general test taking strategies that will improve your chances of getting the grade you want on most, if not all, tests.

1. Listen to the Instructions

Once the test is front of you, it’s tempting to block everything out so you can get started right away.

Doing so, however, could cause you to miss out on critical information about the test itself.

The teacher or proctor may offer details about the structure of the test, time limitations, grading techniques, or other items that could impact your approach. They may also point out steps that you are likely to miss or other tips to help improve your chances of success.

So be sure to pay close attention to their instructions before you get started.

2. Read the Entire Test

If possible, look over the entire test quickly before you get started. Doing so will help you understand the structure of the test and identify areas that may need more or less time.

Once you read over the test, you can plan out how you want to approach each section of the test to ensure that you can complete the entire test within the allotted time.

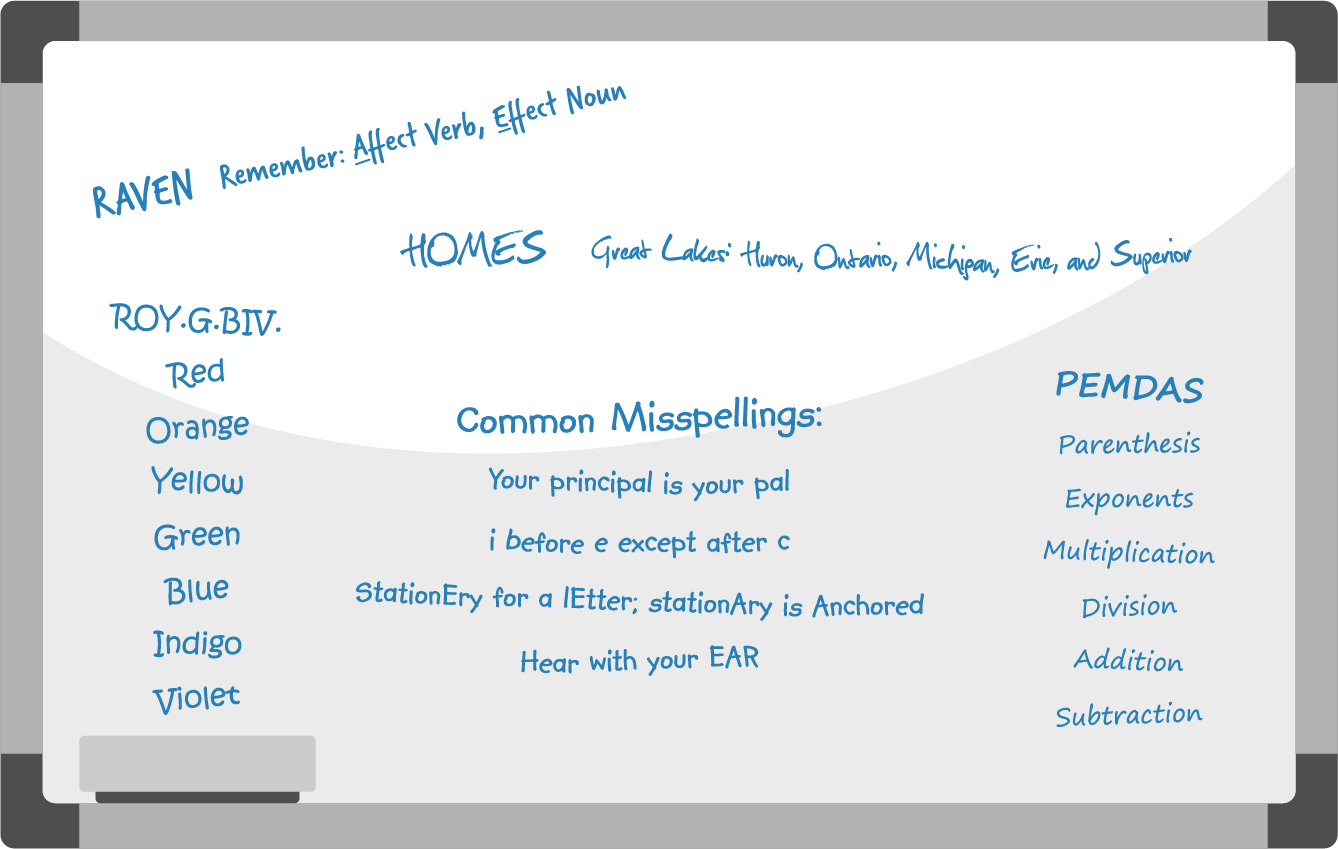

3. Do a “Brain Dump”

For certain types of tests, remembering facts, data, or formulas is key. For these tests, it can be helpful to take a few minutes to write down all the information you need on a scrap paper before you get started.

Putting that important information on paper can relieve stress and help you focus on the test questions without worrying about your ability to recall the facts. And now you have a kind of “cheat sheet” to refer to throughout the test!

4. Answer the Questions You Know First

When possible, do a first pass through the test to answer the “easy” questions or the ones you know right away. When you come to a question that you can’t answer (relatively) quickly, skip it on this first pass.

Don’t rush through this first pass, but do be mindful of time—you’ll want to leave yourself enough time to go back and answer the questions you skipped.

* It’s important to remember that this technique is not possible on some tests. Standardized computer-based tests often do not allow you to skip questions and return to them later. On these types of tests, you will need to work through each problem in order instead of skipping around.

5. Answer the Questions You Skipped

Once you’ve done a first pass, you now have to go back and answer the questions you skipped.

In the best case scenario, you might find some of these questions aren’t as challenging as you thought at first. Your mind is warmed up and you are fully engaged and focused at this point in the test. And answering the questions you know easily may have reminded you of the details you need for these questions.

Of course you may still struggle with some of the questions, and that’s okay. Hopefully doing a first pass somewhat quickly allows you to take your time with the more challenging questions.

6. Be Sure the Test is Complete

Once you think you’ve answered all the questions, double check to make sure you didn’t miss any. Check for additional questions on the back of the paper, for instance, or other places that you might have missed or not noticed during your initial read-through.

A common question is whether you should skip questions that you can’t answer. It’s not possible to answer that question in a general sense: it depends on the specific test and the teacher’s rules. It may also depend on the value of each individual question, and whether your teacher gives partial credit.

But, if you’re not penalized for a wrong answer or you are penalized for leaving an answer blank, it is probably better to put something down than nothing.

7. Check Your Work

Finally, if you have time left, go back through the test and check your answers.

Read over short answer and essay questions to check for typos, points you may have missed, or better ways to phrase your answers. If there were multiple components to the question, make sure you answered all of them. Double check your answers on math questions in case you made a small error that impacts the final answer. You don’t want to overthink answers, but a doublecheck can help you find—and correct—obvious mistakes.

Four Ways to Cope with Test-Taking Anxiety

Nearly every student gets nervous before a test at some point, especially if the exam is an important one. If you are lucky, your pre-test nervousness is mild and can be mitigated by these test taking tips.

A mild case of nerves can even be somewhat beneficial (if uncomfortable); the surge of adrenaline at the root of a nervous feeling can keep you focused and energized.

For some students, however, test taking anxiety—a form of performance anxiety—can be debilitating and overwhelming. This level of anxiety can be extremely difficult to cope with.

However, there are a few things you can do before and during a test to help cope with more severe stress and anxiety:

1. Take a Meditation or Sitting Stretch Break

Take a minute or two before or even during a test to focus on your breathing, relax tense muscles, do a quick positive visualization, or stretch your limbs. The calming effect can be beneficial and worth a few minutes of test time.

2. Replace Negative Thoughts with Positive Ones

Learn to recognize when your brain is caught in a cycle of negative thinking and practice turning negative thoughts into positive ones. For example, when you catch yourself saying “I’m going to fail”, force yourself to say “I’m going to succeed” instead. With practice, this can be a powerful technique to break the cycle of negative thinking undermining your confidence.

3. Mistakes are Learning Opportunities

It’s easy to get caught up in worrying about a bad grade. Instead, remind yourself that it’s ok to make mistakes. A wrong answer on a test is an opportunity to understand where you need to fill in a gap in your knowledge or spend some extra time studying.

4. Seek Professional Help

Test taking anxiety is very real and should be taken seriously. If you find that your anxiety does not respond to these calming tips, it’s time to seek professional help. Your guidance counselor or a therapist may be able to offer long-term strategies for coping with test taking anxiety. Talk with your parents or guardians about finding someone to help you cope.

Following these test taking tips can’t guarantee that you will get an A on your next big test. Only hard work and lots of study time can do that.

However, these test taking strategies can help you feel more confident and perform better on test day. Tests may be an inevitable part of student life, but with preparation and confidence, you can succeed on them all!

Sign up for our mailing list for important information about Harvard Summer School.

About the Author

Digital Content Producer

Emerson is a Digital Content Producer at Harvard DCE. She is a graduate of Brandeis University and Yale University and started her career as an international affairs analyst. She is an avid triathlete and has completed three Ironman triathlons, as well as the Boston Marathon.

Everything You Need to Know About College Summer School: The Complete Guide

This guide will outline the benefits of summer courses and offer tips on how to get the most out of your experience.

Harvard Division of Continuing Education

The Division of Continuing Education (DCE) at Harvard University is dedicated to bringing rigorous academics and innovative teaching capabilities to those seeking to improve their lives through education. We make Harvard education accessible to lifelong learners from high school to retirement.

Do our kids have too much homework?

by: Marian Wilde | Updated: January 31, 2024

Print article

Many students and their parents are frazzled by the amount of homework being piled on in the schools. Yet many researchers say that American students have just the right amount of homework.

“Kids today are overwhelmed!” a parent recently wrote in an email to GreatSchools.org “My first-grade son was required to research a significant person from history and write a paper of at least two pages about the person, with a bibliography. How can he be expected to do that by himself? He just started to learn to read and write a couple of months ago. Schools are pushing too hard and expecting too much from kids.”

Diane Garfield, a fifth grade teacher in San Francisco, concurs. “I believe that we’re stressing children out,” she says.

But hold on, it’s not just the kids who are stressed out . “Teachers nowadays assign these almost college-level projects with requirements that make my mouth fall open with disbelief,” says another frustrated parent. “It’s not just the kids who suffer!”

“How many people take home an average of two hours or more of work that must be completed for the next day?” asks Tonya Noonan Herring, a New Mexico mother of three, an attorney and a former high school English teacher. “Most of us, even attorneys, do not do this. Bottom line: students have too much homework and most of it is not productive or necessary.”

Research about homework

How do educational researchers weigh in on the issue? According to Brian Gill, a senior social scientist at the Rand Corporation, there is no evidence that kids are doing more homework than they did before.

“If you look at high school kids in the late ’90s, they’re not doing substantially more homework than kids did in the ’80s, ’70s, ’60s or the ’40s,” he says. “In fact, the trends through most of this time period are pretty flat. And most high school students in this country don’t do a lot of homework. The median appears to be about four hours a week.”

Education researchers like Gill base their conclusions, in part, on data gathered by the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) tests.

“It doesn’t suggest that most kids are doing a tremendous amount,” says Gill. “That’s not to say there aren’t any kids with too much homework. There surely are some. There’s enormous variation across communities. But it’s not a crisis in that it’s a very small proportion of kids who are spending an enormous amount of time on homework.”

Etta Kralovec, author of The End of Homework: How Homework Disrupts Families, Overburdens Children, and Limits Learning , disagrees, saying NAEP data is not a reliable source of information. “Students take the NAEP test and one of the questions they have to fill out is, ‘How much homework did you do last night’ Anybody who knows schools knows that teachers by and large do not give homework the night before a national assessment. It just doesn’t happen. Teachers are very clear with kids that they need to get a good night’s sleep and they need to eat well to prepare for a test.

“So asking a kid how much homework they did the night before a national test and claiming that that data tells us anything about the general run of the mill experience of kids and homework over the school year is, I think, really dishonest.”

Further muddying the waters is an AP/AOL poll that suggests that most Americans feel that their children are getting the right amount of homework. It found that 57% of parents felt that their child was assigned about the right amount of homework, 23% thought there was too little and 19% thought there was too much.

One indisputable fact

One homework fact that educators do agree upon is that the young child today is doing more homework than ever before.

“Parents are correct in saying that they didn’t get homework in the early grades and that their kids do,” says Harris Cooper, professor of psychology and director of the education program at Duke University.

Gill quantifies the change this way: “There has been some increase in homework for the kids in kindergarten, first grade, and second grade. But it’s been an increase from zero to 20 minutes a day. So that is something that’s fairly new in the last quarter century.”

The history of homework

In his research, Gill found that homework has always been controversial. “Around the turn of the 20th century, the Ladies’ Home Journal carried on a crusade against homework. They thought that kids were better off spending their time outside playing and looking at clouds. The most spectacular success this movement had was in the state of California, where in 1901 the legislature passed a law abolishing homework in grades K-8. That lasted about 15 years and then was quietly repealed. Then there was a lot of activism against homework again in the 1930s.”

The proponents of homework have remained consistent in their reasons for why homework is a beneficial practice, says Gill. “One, it extends the work in the classroom with additional time on task. Second, it develops habits of independent study. Third, it’s a form of communication between the school and the parents. It gives parents an idea of what their kids are doing in school.”

The anti-homework crowd has also been consistent in their reasons for wanting to abolish or reduce homework.

“The first one is children’s health,” says Gill. “A hundred years ago, you had medical doctors testifying that heavy loads of books were causing children’s spines to be bent.”

The more things change, the more they stay the same, it seems. There were also concerns about excessive amounts of stress .

“Although they didn’t use the term ‘stress,'” says Gill. “They worried about ‘nervous breakdowns.'”

“In the 1930s, there were lots of graduate students in education schools around the country who were doing experiments that claimed to show that homework had no academic value — that kids who got homework didn’t learn any more than kids who didn’t,” Gill continues. Also, a lot of the opposition to homework, in the first half of the 20th century, was motivated by a notion that it was a leftover from a 19th-century model of schooling, which was based on recitation, memorization and drill. Progressive educators were trying to replace that with something more creative, something more interesting to kids.”

The more-is-better movement

Garfield, the San Francisco fifth-grade teacher, says that when she started teaching 30 years ago, she didn’t give any homework. “Then parents started asking for it,” she says. “I got In junior high and high school there’s so much homework, they need to get prepared.” So I bought that one. I said, ‘OK, they need to be prepared.’ But they don’t need two hours.”

Cooper sees the trend toward more homework as symptomatic of high-achieving parents who want the best for their children. “Part of it, I think, is pressure from the parents with regard to their desire to have their kids be competitive for the best universities in the country. The communities in which homework is being piled on are generally affluent communities.”

The less-is-better campaign

Alfie Kohn, a widely-admired progressive writer on education and parenting, published a sharp rebuttal to the more-homework-is-better argument in his 2006 book The Homework Myth: Why Our Kids Get Too Much of a Bad Thing . Kohn criticized the pro-homework studies that Cooper referenced as “inconclusive… they only show an association, not a causal relationship” and he titled his first chapter “Missing Out on Their Childhoods.”

Vera Goodman’s 2020 book, Simply Too Much Homework: What Can We Do? , repeats Kohn’s scrutiny and urges parents to appeal to school and government leaders to revise homework policies. Goodman believes today’s homework load stresses out teachers, parents, and students, deprives children of unstructured time for play, hobbies, and individual pursuits, and inhibits the joy of learning.

Homework guidelines

What’s a parent to do, you ask? Fortunately, there are some sanity-saving homework guidelines.

Cooper points to “The 10-Minute Rule” formulated by the National PTA and the National Education Association, which suggests that kids should be doing about 10 minutes of homework per night per grade level. In other words, 10 minutes for first-graders, 20 for second-graders and so on.

Too much homework vs. the optimal amount

Cooper has found that the correlation between homework and achievement is generally supportive of these guidelines. “We found that for kids in elementary school there was hardly any relationship between how much homework young children did and how well they were doing in school, but in middle school the relationship is positive and increases until the kids were doing between an hour to two hours a night, which is right where the 10-minute rule says it’s going to be optimal.

“After that it didn’t go up anymore. Kids that reported doing more than two hours of homework a night in middle school weren’t doing any better in school than kids who were doing between an hour to two hours.”

Garfield has a very clear homework policy that she distributes to her parents at the beginning of each school year. “I give one subject a night. It’s what we were studying in class or preparation for the next day. It should be done within half an hour at most. I believe that children have many outside activities now and they also need to live fully as children. To have them work for six hours a day at school and then go home and work for hours at night does not seem right. It doesn’t allow them to have a childhood.”

International comparisons

How do American kids fare when compared to students in other countries? Professors Gerald LeTendre and David Baker of Pennsylvania State University conclude in their 2005 book, National Differences, Global Similarities: World Culture and the Future of Schooling, that American middle schoolers do more homework than their peers in Japan, Korea, or Taiwan, but less than their peers in Singapore and Hong Kong.

One of the surprising findings of their research was that more homework does not correlate with higher test scores. LeTendre notes: “That really flummoxes people because they say, ‘Doesn’t doing more homework mean getting better scores?’ The answer quite simply is no.”

Homework is a complicated thing

To be effective, homework must be used in a certain way, he says. “Let me give you an example. Most homework in the fourth grade in the U.S. is worksheets. Fill them out, turn them in, maybe the teacher will check them, maybe not. That is a very ineffective use of homework. An effective use of homework would be the teacher sitting down and thinking ‘Elizabeth has trouble with number placement, so I’m going to give her seven problems on number placement.’ Then the next day the teacher sits down with Elizabeth and she says, ‘Was this hard for you? Where did you have difficulty?’ Then she gives Elizabeth either more or less material. As you can imagine, that kind of homework rarely happens.”

Shotgun homework

“What typically happens is people give what we call ‘shotgun homework’: blanket drills, questions and problems from the book. On a national level that’s associated with less well-functioning school systems,” he says. “In a sense, you could sort of think of it as a sign of weaker teachers or less well-prepared teachers. Over time, we see that in elementary and middle schools more and more homework is being given, and that countries around the world are doing this in an attempt to increase their test scores, and that is basically a failing strategy.”

Quality not quantity?

“ The Case for (Quality) Homework: Why It Improves Learning, and How Parents Can Help ,” a 2019 paper written by Boston University psychologist Janine Bempechat, asks for homework that specifically helps children “confront ever-more-complex tasks” that enable them to gain resilience and embrace challenges.

Similar research from University of Ovideo in Spain titled “ Homework: Facts and Fiction 2021 ” says evidence shows that how homework is applied is more important than how much is required, and it asserts that a moderate amount of homework yields the most academic achievement. The most important aspect of quality homework assignment? The effort required and the emotions prompted by the task.

Robyn Jackson, author of How to Plan Rigorous Instruction and other media about rigor says the key to quality homework is not the time spent, but the rigor — or mental challenge — involved. ( Read more about how to evaluate your child’s homework for rigor here .)

Nightly reading as a homework replacement

Across the country, many elementary schools have replaced homework with a nightly reading requirement. There are many benefits to children reading every night , either out loud with a parent or independently: it increases their vocabulary, imagination, concentration, memory, empathy, academic ability, knowledge of different cultures and perspectives. Plus, it reduces stress, helps kids sleep, and bonds children to their cuddling parents or guardians. Twenty to 30 minutes of reading each day is generally recommended.

But, is this always possible, or even ideal?

No, it’s not.

Alfie Kohn criticizes this added assignment in his blog post, “ How To Create Nonreaders .” He cites an example from a parent (Julie King) who reports, “Our children are now expected to read 20 minutes a night, and record such on their homework sheet. What parents are discovering (surprise) is that those kids who used to sit down and read for pleasure — the kids who would get lost in a book and have to be told to put it down to eat/play/whatever — are now setting the timer… and stopping when the timer dings. … Reading has become a chore, like brushing your teeth.”

The take-away from Kohn? Don’t undermine reading for pleasure by turning it into another task burdening your child’s tired brain.

Additional resources

Books Simply Too Much Homework: What Can We do? by Vera Goodman, Trafford Publishing, 2020

The Case Against Homework: How Homework is Hurting Children and What Parents Can Do About It by Sara Bennett and Nancy Kalish, Crown Publishers, 2007

The Homework Myth: Why Our Kids Get Too Much of a Bad Thing by Alfie Kohn, Hatchett Books, 2006 The End of Homework: How Homework Disrupts Families, Overburdens Children, and Limits Learning by Etta Kralovec and John Buell, Beacon Press, 2001.

The Battle Over Homework: Common Ground for Administrators, Teachers, and Parents by Harris M. Cooper, Corwin Press, 2001.

Seven Steps to Homework Success: A Family Guide to Solving Common Homework Problems by Sydney Zentall and Sam Goldstein, Specialty Press, 1998.

Homes Nearby

Homes for rent and sale near schools

Why your neighborhood school closes for good – and what to do when it does

What should I write my college essay about?

What the #%@!& should I write about in my college essay?

How longer recess fuels child development

How longer recess fuels stronger child development

Yes! Sign me up for updates relevant to my child's grade.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up!

Server Issue: Please try again later. Sorry for the inconvenience

Studying 101: Study Smarter Not Harder

Do you ever feel like your study habits simply aren’t cutting it? Do you wonder what you could be doing to perform better in class and on exams? Many students realize that their high school study habits aren’t very effective in college. This is understandable, as college is quite different from high school. The professors are less personally involved, classes are bigger, exams are worth more, reading is more intense, and classes are much more rigorous. That doesn’t mean there’s anything wrong with you; it just means you need to learn some more effective study skills. Fortunately, there are many active, effective study strategies that are shown to be effective in college classes.

This handout offers several tips on effective studying. Implementing these tips into your regular study routine will help you to efficiently and effectively learn course material. Experiment with them and find some that work for you.

Reading is not studying

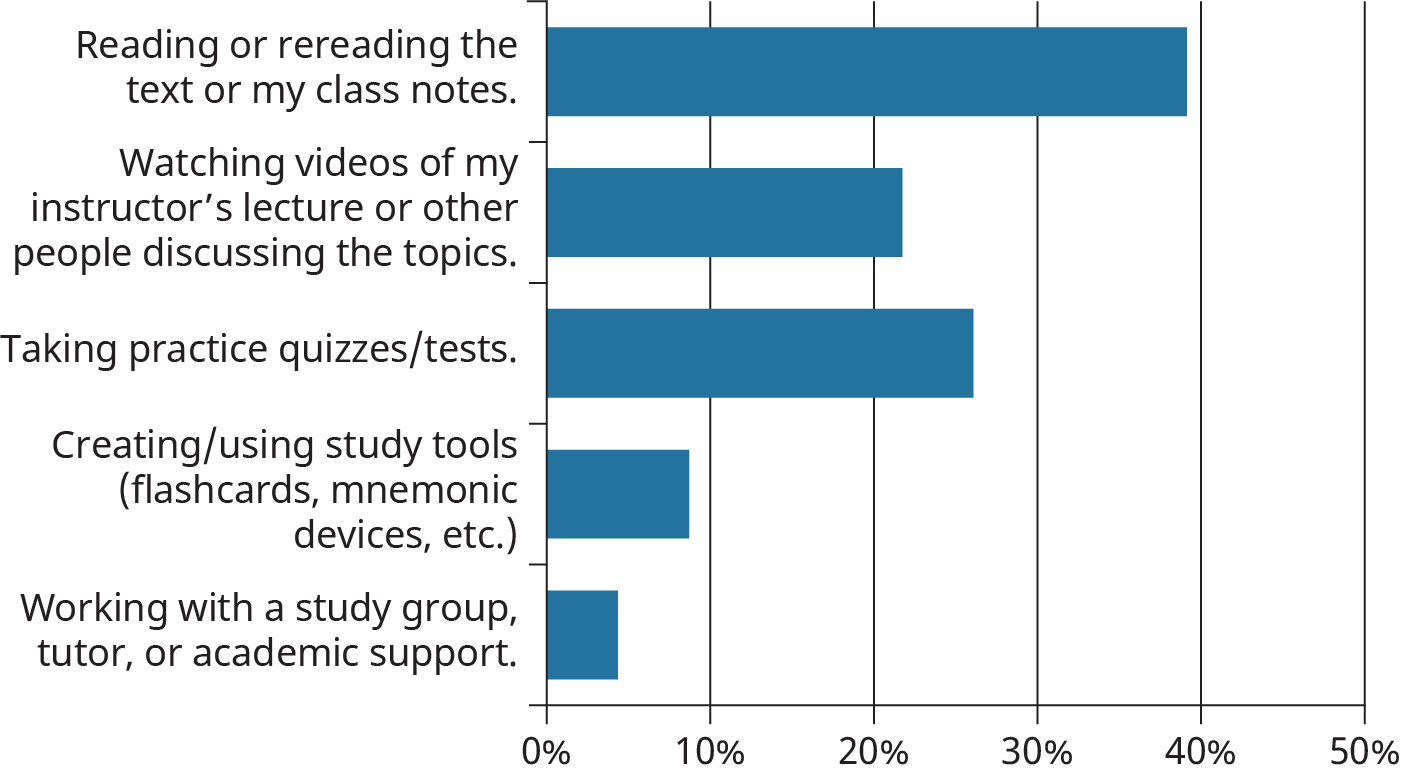

Simply reading and re-reading texts or notes is not actively engaging in the material. It is simply re-reading your notes. Only ‘doing’ the readings for class is not studying. It is simply doing the reading for class. Re-reading leads to quick forgetting.

Think of reading as an important part of pre-studying, but learning information requires actively engaging in the material (Edwards, 2014). Active engagement is the process of constructing meaning from text that involves making connections to lectures, forming examples, and regulating your own learning (Davis, 2007). Active studying does not mean highlighting or underlining text, re-reading, or rote memorization. Though these activities may help to keep you engaged in the task, they are not considered active studying techniques and are weakly related to improved learning (Mackenzie, 1994).

Ideas for active studying include:

- Create a study guide by topic. Formulate questions and problems and write complete answers. Create your own quiz.

- Become a teacher. Say the information aloud in your own words as if you are the instructor and teaching the concepts to a class.

- Derive examples that relate to your own experiences.

- Create concept maps or diagrams that explain the material.

- Develop symbols that represent concepts.

- For non-technical classes (e.g., English, History, Psychology), figure out the big ideas so you can explain, contrast, and re-evaluate them.

- For technical classes, work the problems and explain the steps and why they work.

- Study in terms of question, evidence, and conclusion: What is the question posed by the instructor/author? What is the evidence that they present? What is the conclusion?

Organization and planning will help you to actively study for your courses. When studying for a test, organize your materials first and then begin your active reviewing by topic (Newport, 2007). Often professors provide subtopics on the syllabi. Use them as a guide to help organize your materials. For example, gather all of the materials for one topic (e.g., PowerPoint notes, text book notes, articles, homework, etc.) and put them together in a pile. Label each pile with the topic and study by topics.

For more information on the principle behind active studying, check out our tipsheet on metacognition .

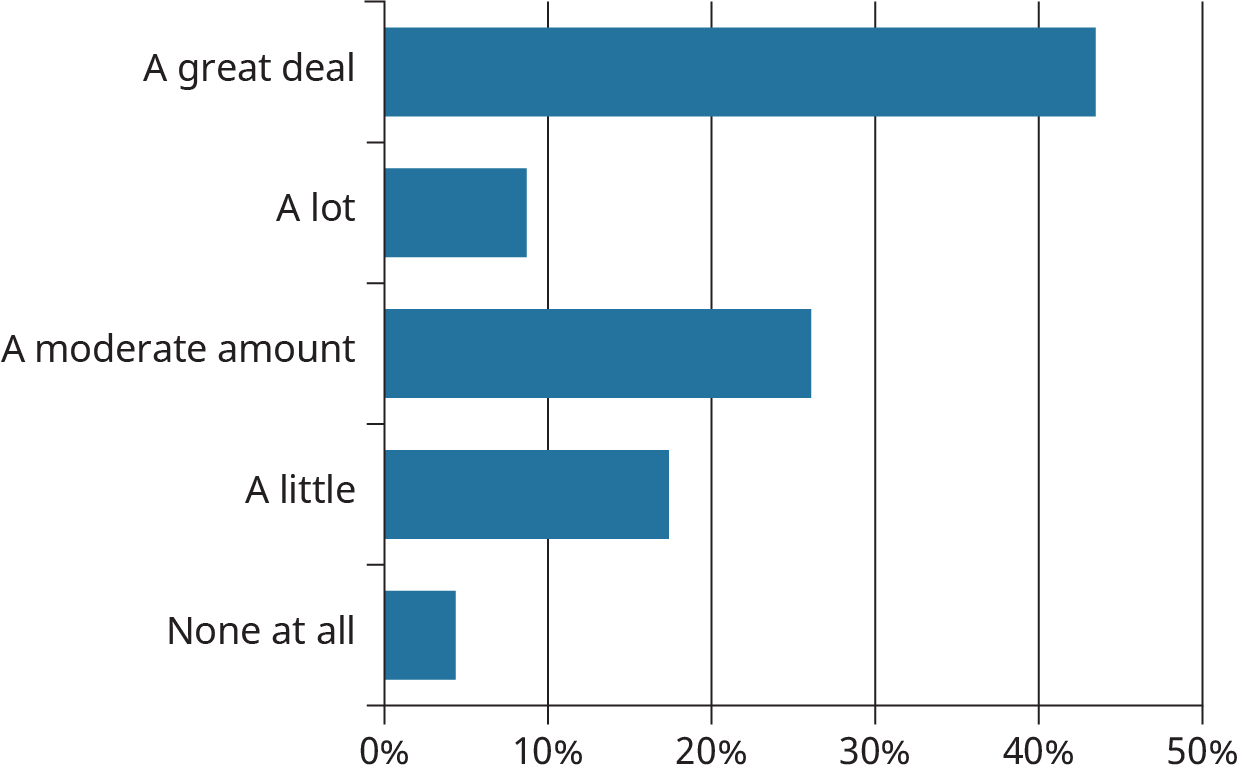

Understand the Study Cycle

The Study Cycle , developed by Frank Christ, breaks down the different parts of studying: previewing, attending class, reviewing, studying, and checking your understanding. Although each step may seem obvious at a glance, all too often students try to take shortcuts and miss opportunities for good learning. For example, you may skip a reading before class because the professor covers the same material in class; doing so misses a key opportunity to learn in different modes (reading and listening) and to benefit from the repetition and distributed practice (see #3 below) that you’ll get from both reading ahead and attending class. Understanding the importance of all stages of this cycle will help make sure you don’t miss opportunities to learn effectively.

Spacing out is good

One of the most impactful learning strategies is “distributed practice”—spacing out your studying over several short periods of time over several days and weeks (Newport, 2007). The most effective practice is to work a short time on each class every day. The total amount of time spent studying will be the same (or less) than one or two marathon library sessions, but you will learn the information more deeply and retain much more for the long term—which will help get you an A on the final. The important thing is how you use your study time, not how long you study. Long study sessions lead to a lack of concentration and thus a lack of learning and retention.

In order to spread out studying over short periods of time across several days and weeks, you need control over your schedule . Keeping a list of tasks to complete on a daily basis will help you to include regular active studying sessions for each class. Try to do something for each class each day. Be specific and realistic regarding how long you plan to spend on each task—you should not have more tasks on your list than you can reasonably complete during the day.

For example, you may do a few problems per day in math rather than all of them the hour before class. In history, you can spend 15-20 minutes each day actively studying your class notes. Thus, your studying time may still be the same length, but rather than only preparing for one class, you will be preparing for all of your classes in short stretches. This will help focus, stay on top of your work, and retain information.

In addition to learning the material more deeply, spacing out your work helps stave off procrastination. Rather than having to face the dreaded project for four hours on Monday, you can face the dreaded project for 30 minutes each day. The shorter, more consistent time to work on a dreaded project is likely to be more acceptable and less likely to be delayed to the last minute. Finally, if you have to memorize material for class (names, dates, formulas), it is best to make flashcards for this material and review periodically throughout the day rather than one long, memorization session (Wissman and Rawson, 2012). See our handout on memorization strategies to learn more.

It’s good to be intense

Not all studying is equal. You will accomplish more if you study intensively. Intensive study sessions are short and will allow you to get work done with minimal wasted effort. Shorter, intensive study times are more effective than drawn out studying.

In fact, one of the most impactful study strategies is distributing studying over multiple sessions (Newport, 2007). Intensive study sessions can last 30 or 45-minute sessions and include active studying strategies. For example, self-testing is an active study strategy that improves the intensity of studying and efficiency of learning. However, planning to spend hours on end self-testing is likely to cause you to become distracted and lose your attention.

On the other hand, if you plan to quiz yourself on the course material for 45 minutes and then take a break, you are much more likely to maintain your attention and retain the information. Furthermore, the shorter, more intense sessions will likely put the pressure on that is needed to prevent procrastination.

Silence isn’t golden

Know where you study best. The silence of a library may not be the best place for you. It’s important to consider what noise environment works best for you. You might find that you concentrate better with some background noise. Some people find that listening to classical music while studying helps them concentrate, while others find this highly distracting. The point is that the silence of the library may be just as distracting (or more) than the noise of a gymnasium. Thus, if silence is distracting, but you prefer to study in the library, try the first or second floors where there is more background ‘buzz.’

Keep in mind that active studying is rarely silent as it often requires saying the material aloud.

Problems are your friend

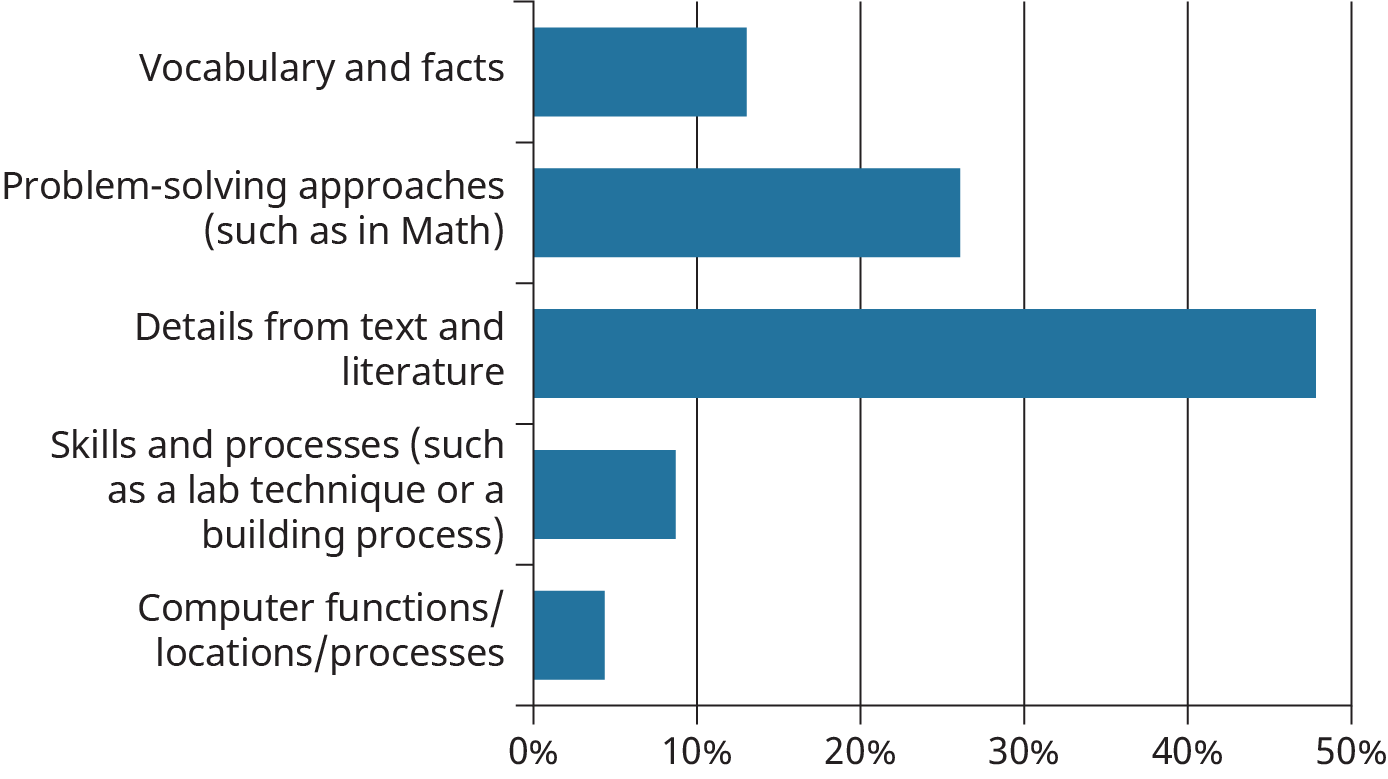

Working and re-working problems is important for technical courses (e.g., math, economics). Be able to explain the steps of the problems and why they work.

In technical courses, it is usually more important to work problems than read the text (Newport, 2007). In class, write down in detail the practice problems demonstrated by the professor. Annotate each step and ask questions if you are confused. At the very least, record the question and the answer (even if you miss the steps).

When preparing for tests, put together a large list of problems from the course materials and lectures. Work the problems and explain the steps and why they work (Carrier, 2003).

Reconsider multitasking

A significant amount of research indicates that multi-tasking does not improve efficiency and actually negatively affects results (Junco, 2012).

In order to study smarter, not harder, you will need to eliminate distractions during your study sessions. Social media, web browsing, game playing, texting, etc. will severely affect the intensity of your study sessions if you allow them! Research is clear that multi-tasking (e.g., responding to texts, while studying), increases the amount of time needed to learn material and decreases the quality of the learning (Junco, 2012).

Eliminating the distractions will allow you to fully engage during your study sessions. If you don’t need your computer for homework, then don’t use it. Use apps to help you set limits on the amount of time you can spend at certain sites during the day. Turn your phone off. Reward intensive studying with a social-media break (but make sure you time your break!) See our handout on managing technology for more tips and strategies.

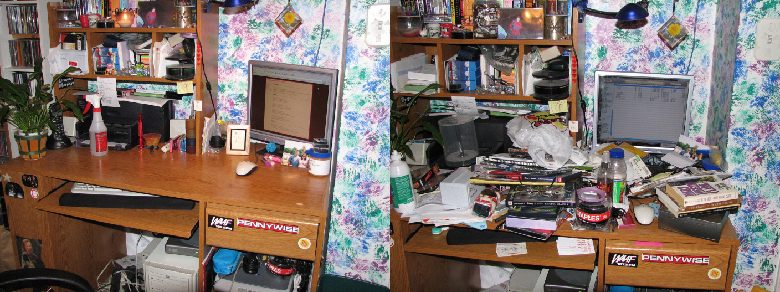

Switch up your setting

Find several places to study in and around campus and change up your space if you find that it is no longer a working space for you.

Know when and where you study best. It may be that your focus at 10:00 PM. is not as sharp as at 10:00 AM. Perhaps you are more productive at a coffee shop with background noise, or in the study lounge in your residence hall. Perhaps when you study on your bed, you fall asleep.

Have a variety of places in and around campus that are good study environments for you. That way wherever you are, you can find your perfect study spot. After a while, you might find that your spot is too comfortable and no longer is a good place to study, so it’s time to hop to a new spot!

Become a teacher

Try to explain the material in your own words, as if you are the teacher. You can do this in a study group, with a study partner, or on your own. Saying the material aloud will point out where you are confused and need more information and will help you retain the information. As you are explaining the material, use examples and make connections between concepts (just as a teacher does). It is okay (even encouraged) to do this with your notes in your hands. At first you may need to rely on your notes to explain the material, but eventually you’ll be able to teach it without your notes.

Creating a quiz for yourself will help you to think like your professor. What does your professor want you to know? Quizzing yourself is a highly effective study technique. Make a study guide and carry it with you so you can review the questions and answers periodically throughout the day and across several days. Identify the questions that you don’t know and quiz yourself on only those questions. Say your answers aloud. This will help you to retain the information and make corrections where they are needed. For technical courses, do the sample problems and explain how you got from the question to the answer. Re-do the problems that give you trouble. Learning the material in this way actively engages your brain and will significantly improve your memory (Craik, 1975).

Take control of your calendar

Controlling your schedule and your distractions will help you to accomplish your goals.

If you are in control of your calendar, you will be able to complete your assignments and stay on top of your coursework. The following are steps to getting control of your calendar:

- On the same day each week, (perhaps Sunday nights or Saturday mornings) plan out your schedule for the week.

- Go through each class and write down what you’d like to get completed for each class that week.

- Look at your calendar and determine how many hours you have to complete your work.

- Determine whether your list can be completed in the amount of time that you have available. (You may want to put the amount of time expected to complete each assignment.) Make adjustments as needed. For example, if you find that it will take more hours to complete your work than you have available, you will likely need to triage your readings. Completing all of the readings is a luxury. You will need to make decisions about your readings based on what is covered in class. You should read and take notes on all of the assignments from the favored class source (the one that is used a lot in the class). This may be the textbook or a reading that directly addresses the topic for the day. You can likely skim supplemental readings.

- Pencil into your calendar when you plan to get assignments completed.

- Before going to bed each night, make your plan for the next day. Waking up with a plan will make you more productive.

See our handout on calendars and college for more tips on using calendars as time management.

Use downtime to your advantage

Beware of ‘easy’ weeks. This is the calm before the storm. Lighter work weeks are a great time to get ahead on work or to start long projects. Use the extra hours to get ahead on assignments or start big projects or papers. You should plan to work on every class every week even if you don’t have anything due. In fact, it is preferable to do some work for each of your classes every day. Spending 30 minutes per class each day will add up to three hours per week, but spreading this time out over six days is more effective than cramming it all in during one long three-hour session. If you have completed all of the work for a particular class, then use the 30 minutes to get ahead or start a longer project.

Use all your resources

Remember that you can make an appointment with an academic coach to work on implementing any of the strategies suggested in this handout.

Works consulted

Carrier, L. M. (2003). College students’ choices of study strategies. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 96 (1), 54-56.

Craik, F. I., & Tulving, E. (1975). Depth of processing and the retention of words in episodic memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 104 (3), 268.

Davis, S. G., & Gray, E. S. (2007). Going beyond test-taking strategies: Building self-regulated students and teachers. Journal of Curriculum and Instruction, 1 (1), 31-47.

Edwards, A. J., Weinstein, C. E., Goetz, E. T., & Alexander, P. A. (2014). Learning and study strategies: Issues in assessment, instruction, and evaluation. Elsevier.

Junco, R., & Cotten, S. R. (2012). No A 4 U: The relationship between multitasking and academic performance. Computers & Education, 59 (2), 505-514.

Mackenzie, A. M. (1994). Examination preparation, anxiety and examination performance in a group of adult students. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 13 (5), 373-388.

McGuire, S.Y. & McGuire, S. (2016). Teach Students How to Learn: Strategies You Can Incorporate in Any Course to Improve Student Metacognition, Study Skills, and Motivation. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Newport, C. (2006). How to become a straight-a student: the unconventional strategies real college students use to score high while studying less. Three Rivers Press.

Paul, K. (1996). Study smarter, not harder. Self Counsel Press.

Robinson, A. (1993). What smart students know: maximum grades, optimum learning, minimum time. Crown trade paperbacks.

Wissman, K. T., Rawson, K. A., & Pyc, M. A. (2012). How and when do students use flashcards? Memory, 20, 568-579.

If you enjoy using our handouts, we appreciate contributions of acknowledgement.

Make a Gift

- Our Mission

What’s the Right Amount of Homework?

Decades of research show that homework has some benefits, especially for students in middle and high school—but there are risks to assigning too much.

Many teachers and parents believe that homework helps students build study skills and review concepts learned in class. Others see homework as disruptive and unnecessary, leading to burnout and turning kids off to school. Decades of research show that the issue is more nuanced and complex than most people think: Homework is beneficial, but only to a degree. Students in high school gain the most, while younger kids benefit much less.

The National PTA and the National Education Association support the “ 10-minute homework guideline ”—a nightly 10 minutes of homework per grade level. But many teachers and parents are quick to point out that what matters is the quality of the homework assigned and how well it meets students’ needs, not the amount of time spent on it.

The guideline doesn’t account for students who may need to spend more—or less—time on assignments. In class, teachers can make adjustments to support struggling students, but at home, an assignment that takes one student 30 minutes to complete may take another twice as much time—often for reasons beyond their control. And homework can widen the achievement gap, putting students from low-income households and students with learning disabilities at a disadvantage.

However, the 10-minute guideline is useful in setting a limit: When kids spend too much time on homework, there are real consequences to consider.

Small Benefits for Elementary Students

As young children begin school, the focus should be on cultivating a love of learning, and assigning too much homework can undermine that goal. And young students often don’t have the study skills to benefit fully from homework, so it may be a poor use of time (Cooper, 1989 ; Cooper et al., 2006 ; Marzano & Pickering, 2007 ). A more effective activity may be nightly reading, especially if parents are involved. The benefits of reading are clear: If students aren’t proficient readers by the end of third grade, they’re less likely to succeed academically and graduate from high school (Fiester, 2013 ).

For second-grade teacher Jacqueline Fiorentino, the minor benefits of homework did not outweigh the potential drawback of turning young children against school at an early age, so she experimented with dropping mandatory homework. “Something surprising happened: They started doing more work at home,” Fiorentino writes . “This inspiring group of 8-year-olds used their newfound free time to explore subjects and topics of interest to them.” She encouraged her students to read at home and offered optional homework to extend classroom lessons and help them review material.

Moderate Benefits for Middle School Students

As students mature and develop the study skills necessary to delve deeply into a topic—and to retain what they learn—they also benefit more from homework. Nightly assignments can help prepare them for scholarly work, and research shows that homework can have moderate benefits for middle school students (Cooper et al., 2006 ). Recent research also shows that online math homework, which can be designed to adapt to students’ levels of understanding, can significantly boost test scores (Roschelle et al., 2016 ).

There are risks to assigning too much, however: A 2015 study found that when middle school students were assigned more than 90 to 100 minutes of daily homework, their math and science test scores began to decline (Fernández-Alonso, Suárez-Álvarez, & Muñiz, 2015 ). Crossing that upper limit can drain student motivation and focus. The researchers recommend that “homework should present a certain level of challenge or difficulty, without being so challenging that it discourages effort.” Teachers should avoid low-effort, repetitive assignments, and assign homework “with the aim of instilling work habits and promoting autonomous, self-directed learning.”

In other words, it’s the quality of homework that matters, not the quantity. Brian Sztabnik, a veteran middle and high school English teacher, suggests that teachers take a step back and ask themselves these five questions :

- How long will it take to complete?

- Have all learners been considered?

- Will an assignment encourage future success?

- Will an assignment place material in a context the classroom cannot?

- Does an assignment offer support when a teacher is not there?

More Benefits for High School Students, but Risks as Well

By the time they reach high school, students should be well on their way to becoming independent learners, so homework does provide a boost to learning at this age, as long as it isn’t overwhelming (Cooper et al., 2006 ; Marzano & Pickering, 2007 ). When students spend too much time on homework—more than two hours each night—it takes up valuable time to rest and spend time with family and friends. A 2013 study found that high school students can experience serious mental and physical health problems, from higher stress levels to sleep deprivation, when assigned too much homework (Galloway, Conner, & Pope, 2013 ).

Homework in high school should always relate to the lesson and be doable without any assistance, and feedback should be clear and explicit.

Teachers should also keep in mind that not all students have equal opportunities to finish their homework at home, so incomplete homework may not be a true reflection of their learning—it may be more a result of issues they face outside of school. They may be hindered by issues such as lack of a quiet space at home, resources such as a computer or broadband connectivity, or parental support (OECD, 2014 ). In such cases, giving low homework scores may be unfair.

Since the quantities of time discussed here are totals, teachers in middle and high school should be aware of how much homework other teachers are assigning. It may seem reasonable to assign 30 minutes of daily homework, but across six subjects, that’s three hours—far above a reasonable amount even for a high school senior. Psychologist Maurice Elias sees this as a common mistake: Individual teachers create homework policies that in aggregate can overwhelm students. He suggests that teachers work together to develop a school-wide homework policy and make it a key topic of back-to-school night and the first parent-teacher conferences of the school year.

Parents Play a Key Role

Homework can be a powerful tool to help parents become more involved in their child’s learning (Walker et al., 2004 ). It can provide insights into a child’s strengths and interests, and can also encourage conversations about a child’s life at school. If a parent has positive attitudes toward homework, their children are more likely to share those same values, promoting academic success.

But it’s also possible for parents to be overbearing, putting too much emphasis on test scores or grades, which can be disruptive for children (Madjar, Shklar, & Moshe, 2015 ). Parents should avoid being overly intrusive or controlling—students report feeling less motivated to learn when they don’t have enough space and autonomy to do their homework (Orkin, May, & Wolf, 2017 ; Patall, Cooper, & Robinson, 2008 ; Silinskas & Kikas, 2017 ). So while homework can encourage parents to be more involved with their kids, it’s important to not make it a source of conflict.

- About the Hub

- Announcements

- Faculty Experts Guide

- Subscribe to the newsletter

Explore by Topic

- Arts+Culture

- Politics+Society

- Science+Technology

- Student Life

- University News

- Voices+Opinion

- About Hub at Work

- Gazette Archive

- Benefits+Perks

- Health+Well-Being

- Current Issue

- About the Magazine

- Past Issues

- Support Johns Hopkins Magazine

- Subscribe to the Magazine

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Credit: August de Richelieu

Does homework still have value? A Johns Hopkins education expert weighs in

Joyce epstein, co-director of the center on school, family, and community partnerships, discusses why homework is essential, how to maximize its benefit to learners, and what the 'no-homework' approach gets wrong.

By Vicky Hallett

The necessity of homework has been a subject of debate since at least as far back as the 1890s, according to Joyce L. Epstein , co-director of the Center on School, Family, and Community Partnerships at Johns Hopkins University. "It's always been the case that parents, kids—and sometimes teachers, too—wonder if this is just busy work," Epstein says.

But after decades of researching how to improve schools, the professor in the Johns Hopkins School of Education remains certain that homework is essential—as long as the teachers have done their homework, too. The National Network of Partnership Schools , which she founded in 1995 to advise schools and districts on ways to improve comprehensive programs of family engagement, has developed hundreds of improved homework ideas through its Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork program. For an English class, a student might interview a parent on popular hairstyles from their youth and write about the differences between then and now. Or for science class, a family could identify forms of matter over the dinner table, labeling foods as liquids or solids. These innovative and interactive assignments not only reinforce concepts from the classroom but also foster creativity, spark discussions, and boost student motivation.

"We're not trying to eliminate homework procedures, but expand and enrich them," says Epstein, who is packing this research into a forthcoming book on the purposes and designs of homework. In the meantime, the Hub couldn't wait to ask her some questions:

What kind of homework training do teachers typically get?

Future teachers and administrators really have little formal training on how to design homework before they assign it. This means that most just repeat what their teachers did, or they follow textbook suggestions at the end of units. For example, future teachers are well prepared to teach reading and literacy skills at each grade level, and they continue to learn to improve their teaching of reading in ongoing in-service education. By contrast, most receive little or no training on the purposes and designs of homework in reading or other subjects. It is really important for future teachers to receive systematic training to understand that they have the power, opportunity, and obligation to design homework with a purpose.

Why do students need more interactive homework?

If homework assignments are always the same—10 math problems, six sentences with spelling words—homework can get boring and some kids just stop doing their assignments, especially in the middle and high school years. When we've asked teachers what's the best homework you've ever had or designed, invariably we hear examples of talking with a parent or grandparent or peer to share ideas. To be clear, parents should never be asked to "teach" seventh grade science or any other subject. Rather, teachers set up the homework assignments so that the student is in charge. It's always the student's homework. But a good activity can engage parents in a fun, collaborative way. Our data show that with "good" assignments, more kids finish their work, more kids interact with a family partner, and more parents say, "I learned what's happening in the curriculum." It all works around what the youngsters are learning.

Is family engagement really that important?

At Hopkins, I am part of the Center for Social Organization of Schools , a research center that studies how to improve many aspects of education to help all students do their best in school. One thing my colleagues and I realized was that we needed to look deeply into family and community engagement. There were so few references to this topic when we started that we had to build the field of study. When children go to school, their families "attend" with them whether a teacher can "see" the parents or not. So, family engagement is ever-present in the life of a school.

My daughter's elementary school doesn't assign homework until third grade. What's your take on "no homework" policies?

There are some parents, writers, and commentators who have argued against homework, especially for very young children. They suggest that children should have time to play after school. This, of course is true, but many kindergarten kids are excited to have homework like their older siblings. If they give homework, most teachers of young children make assignments very short—often following an informal rule of 10 minutes per grade level. "No homework" does not guarantee that all students will spend their free time in productive and imaginative play.

Some researchers and critics have consistently misinterpreted research findings. They have argued that homework should be assigned only at the high school level where data point to a strong connection of doing assignments with higher student achievement . However, as we discussed, some students stop doing homework. This leads, statistically, to results showing that doing homework or spending more minutes on homework is linked to higher student achievement. If slow or struggling students are not doing their assignments, they contribute to—or cause—this "result."

Teachers need to design homework that even struggling students want to do because it is interesting. Just about all students at any age level react positively to good assignments and will tell you so.

Did COVID change how schools and parents view homework?

Within 24 hours of the day school doors closed in March 2020, just about every school and district in the country figured out that teachers had to talk to and work with students' parents. This was not the same as homeschooling—teachers were still working hard to provide daily lessons. But if a child was learning at home in the living room, parents were more aware of what they were doing in school. One of the silver linings of COVID was that teachers reported that they gained a better understanding of their students' families. We collected wonderfully creative examples of activities from members of the National Network of Partnership Schools. I'm thinking of one art activity where every child talked with a parent about something that made their family unique. Then they drew their finding on a snowflake and returned it to share in class. In math, students talked with a parent about something the family liked so much that they could represent it 100 times. Conversations about schoolwork at home was the point.

How did you create so many homework activities via the Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork program?

We had several projects with educators to help them design interactive assignments, not just "do the next three examples on page 38." Teachers worked in teams to create TIPS activities, and then we turned their work into a standard TIPS format in math, reading/language arts, and science for grades K-8. Any teacher can use or adapt our prototypes to match their curricula.

Overall, we know that if future teachers and practicing educators were prepared to design homework assignments to meet specific purposes—including but not limited to interactive activities—more students would benefit from the important experience of doing their homework. And more parents would, indeed, be partners in education.

Posted in Voices+Opinion

You might also like

News network.

- Johns Hopkins Magazine

- Get Email Updates

- Submit an Announcement

- Submit an Event

- Privacy Statement

- Accessibility

Discover JHU

- About the University

- Schools & Divisions

- Academic Programs

- Plan a Visit

- my.JohnsHopkins.edu

- © 2024 Johns Hopkins University . All rights reserved.

- University Communications

- 3910 Keswick Rd., Suite N2600, Baltimore, MD

- X Facebook LinkedIn YouTube Instagram

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, how to do homework: 15 expert tips and tricks.

Coursework/GPA

Everyone struggles with homework sometimes, but if getting your homework done has become a chronic issue for you, then you may need a little extra help. That’s why we’ve written this article all about how to do homework. Once you’re finished reading it, you’ll know how to do homework (and have tons of new ways to motivate yourself to do homework)!

We’ve broken this article down into a few major sections. You’ll find:

- A diagnostic test to help you figure out why you’re struggling with homework

- A discussion of the four major homework problems students face, along with expert tips for addressing them

- A bonus section with tips for how to do homework fast

By the end of this article, you’ll be prepared to tackle whatever homework assignments your teachers throw at you .

So let’s get started!

How to Do Homework: Figure Out Your Struggles

Sometimes it feels like everything is standing between you and getting your homework done. But the truth is, most people only have one or two major roadblocks that are keeping them from getting their homework done well and on time.

The best way to figure out how to get motivated to do homework starts with pinpointing the issues that are affecting your ability to get your assignments done. That’s why we’ve developed a short quiz to help you identify the areas where you’re struggling.

Take the quiz below and record your answers on your phone or on a scrap piece of paper. Keep in mind there are no wrong answers!

1. You’ve just been assigned an essay in your English class that’s due at the end of the week. What’s the first thing you do?

A. Keep it in mind, even though you won’t start it until the day before it’s due B. Open up your planner. You’ve got to figure out when you’ll write your paper since you have band practice, a speech tournament, and your little sister’s dance recital this week, too. C. Groan out loud. Another essay? You could barely get yourself to write the last one! D. Start thinking about your essay topic, which makes you think about your art project that’s due the same day, which reminds you that your favorite artist might have just posted to Instagram...so you better check your feed right now.

2. Your mom asked you to pick up your room before she gets home from work. You’ve just gotten home from school. You decide you’ll tackle your chores:

A. Five minutes before your mom walks through the front door. As long as it gets done, who cares when you start? B. As soon as you get home from your shift at the local grocery store. C. After you give yourself a 15-minute pep talk about how you need to get to work. D. You won’t get it done. Between texts from your friends, trying to watch your favorite Netflix show, and playing with your dog, you just lost track of time!

3. You’ve signed up to wash dogs at the Humane Society to help earn money for your senior class trip. You:

A. Show up ten minutes late. You put off leaving your house until the last minute, then got stuck in unexpected traffic on the way to the shelter. B. Have to call and cancel at the last minute. You forgot you’d already agreed to babysit your cousin and bake cupcakes for tomorrow’s bake sale. C. Actually arrive fifteen minutes early with extra brushes and bandanas you picked up at the store. You’re passionate about animals, so you’re excited to help out! D. Show up on time, but only get three dogs washed. You couldn’t help it: you just kept getting distracted by how cute they were!

4. You have an hour of downtime, so you decide you’re going to watch an episode of The Great British Baking Show. You:

A. Scroll through your social media feeds for twenty minutes before hitting play, which means you’re not able to finish the whole episode. Ugh! You really wanted to see who was sent home! B. Watch fifteen minutes until you remember you’re supposed to pick up your sister from band practice before heading to your part-time job. No GBBO for you! C. You finish one episode, then decide to watch another even though you’ve got SAT studying to do. It’s just more fun to watch people make scones. D. Start the episode, but only catch bits and pieces of it because you’re reading Twitter, cleaning out your backpack, and eating a snack at the same time.

5. Your teacher asks you to stay after class because you’ve missed turning in two homework assignments in a row. When she asks you what’s wrong, you say:

A. You planned to do your assignments during lunch, but you ran out of time. You decided it would be better to turn in nothing at all than submit unfinished work. B. You really wanted to get the assignments done, but between your extracurriculars, family commitments, and your part-time job, your homework fell through the cracks. C. You have a hard time psyching yourself to tackle the assignments. You just can’t seem to find the motivation to work on them once you get home. D. You tried to do them, but you had a hard time focusing. By the time you realized you hadn’t gotten anything done, it was already time to turn them in.

Like we said earlier, there are no right or wrong answers to this quiz (though your results will be better if you answered as honestly as possible). Here’s how your answers break down:

- If your answers were mostly As, then your biggest struggle with doing homework is procrastination.

- If your answers were mostly Bs, then your biggest struggle with doing homework is time management.

- If your answers were mostly Cs, then your biggest struggle with doing homework is motivation.

- If your answers were mostly Ds, then your biggest struggle with doing homework is getting distracted.

Now that you’ve identified why you’re having a hard time getting your homework done, we can help you figure out how to fix it! Scroll down to find your core problem area to learn more about how you can start to address it.

And one more thing: you’re really struggling with homework, it’s a good idea to read through every section below. You may find some additional tips that will help make homework less intimidating.

How to Do Homework When You’re a Procrastinator

Merriam Webster defines “procrastinate” as “to put off intentionally and habitually.” In other words, procrastination is when you choose to do something at the last minute on a regular basis. If you’ve ever found yourself pulling an all-nighter, trying to finish an assignment between periods, or sprinting to turn in a paper minutes before a deadline, you’ve experienced the effects of procrastination.

If you’re a chronic procrastinator, you’re in good company. In fact, one study found that 70% to 95% of undergraduate students procrastinate when it comes to doing their homework. Unfortunately, procrastination can negatively impact your grades. Researchers have found that procrastination can lower your grade on an assignment by as much as five points ...which might not sound serious until you realize that can mean the difference between a B- and a C+.

Procrastination can also negatively affect your health by increasing your stress levels , which can lead to other health conditions like insomnia, a weakened immune system, and even heart conditions. Getting a handle on procrastination can not only improve your grades, it can make you feel better, too!

The big thing to understand about procrastination is that it’s not the result of laziness. Laziness is defined as being “disinclined to activity or exertion.” In other words, being lazy is all about doing nothing. But a s this Psychology Today article explains , procrastinators don’t put things off because they don’t want to work. Instead, procrastinators tend to postpone tasks they don’t want to do in favor of tasks that they perceive as either more important or more fun. Put another way, procrastinators want to do things...as long as it’s not their homework!

3 Tips f or Conquering Procrastination

Because putting off doing homework is a common problem, there are lots of good tactics for addressing procrastination. Keep reading for our three expert tips that will get your homework habits back on track in no time.

#1: Create a Reward System

Like we mentioned earlier, procrastination happens when you prioritize other activities over getting your homework done. Many times, this happens because homework...well, just isn’t enjoyable. But you can add some fun back into the process by rewarding yourself for getting your work done.

Here’s what we mean: let’s say you decide that every time you get your homework done before the day it’s due, you’ll give yourself a point. For every five points you earn, you’ll treat yourself to your favorite dessert: a chocolate cupcake! Now you have an extra (delicious!) incentive to motivate you to leave procrastination in the dust.

If you’re not into cupcakes, don’t worry. Your reward can be anything that motivates you . Maybe it’s hanging out with your best friend or an extra ten minutes of video game time. As long as you’re choosing something that makes homework worth doing, you’ll be successful.

#2: Have a Homework Accountability Partner

If you’re having trouble getting yourself to start your homework ahead of time, it may be a good idea to call in reinforcements . Find a friend or classmate you can trust and explain to them that you’re trying to change your homework habits. Ask them if they’d be willing to text you to make sure you’re doing your homework and check in with you once a week to see if you’re meeting your anti-procrastination goals.

Sharing your goals can make them feel more real, and an accountability partner can help hold you responsible for your decisions. For example, let’s say you’re tempted to put off your science lab write-up until the morning before it’s due. But you know that your accountability partner is going to text you about it tomorrow...and you don’t want to fess up that you haven’t started your assignment. A homework accountability partner can give you the extra support and incentive you need to keep your homework habits on track.

#3: Create Your Own Due Dates

If you’re a life-long procrastinator, you might find that changing the habit is harder than you expected. In that case, you might try using procrastination to your advantage! If you just can’t seem to stop doing your work at the last minute, try setting your own due dates for assignments that range from a day to a week before the assignment is actually due.

Here’s what we mean. Let’s say you have a math worksheet that’s been assigned on Tuesday and is due on Friday. In your planner, you can write down the due date as Thursday instead. You may still put off your homework assignment until the last minute...but in this case, the “last minute” is a day before the assignment’s real due date . This little hack can trick your procrastination-addicted brain into planning ahead!

If you feel like Kevin Hart in this meme, then our tips for doing homework when you're busy are for you.

How to Do Homework When You’re too Busy

If you’re aiming to go to a top-tier college , you’re going to have a full plate. Because college admissions is getting more competitive, it’s important that you’re maintaining your grades , studying hard for your standardized tests , and participating in extracurriculars so your application stands out. A packed schedule can get even more hectic once you add family obligations or a part-time job to the mix.

If you feel like you’re being pulled in a million directions at once, you’re not alone. Recent research has found that stress—and more severe stress-related conditions like anxiety and depression— are a major problem for high school students . In fact, one study from the American Psychological Association found that during the school year, students’ stress levels are higher than those of the adults around them.

For students, homework is a major contributor to their overall stress levels . Many high schoolers have multiple hours of homework every night , and figuring out how to fit it into an already-packed schedule can seem impossible.

3 Tips for Fitting Homework Into Your Busy Schedule

While it might feel like you have literally no time left in your schedule, there are still ways to make sure you’re able to get your homework done and meet your other commitments. Here are our expert homework tips for even the busiest of students.

#1: Make a Prioritized To-Do List

You probably already have a to-do list to keep yourself on track. The next step is to prioritize the items on your to-do list so you can see what items need your attention right away.

Here’s how it works: at the beginning of each day, sit down and make a list of all the items you need to get done before you go to bed. This includes your homework, but it should also take into account any practices, chores, events, or job shifts you may have. Once you get everything listed out, it’s time to prioritize them using the labels A, B, and C. Here’s what those labels mean:

- A Tasks : tasks that have to get done—like showing up at work or turning in an assignment—get an A.

- B Tasks : these are tasks that you would like to get done by the end of the day but aren’t as time sensitive. For example, studying for a test you have next week could be a B-level task. It’s still important, but it doesn’t have to be done right away.

- C Tasks: these are tasks that aren’t very important and/or have no real consequences if you don’t get them done immediately. For instance, if you’re hoping to clean out your closet but it’s not an assigned chore from your parents, you could label that to-do item with a C.

Prioritizing your to-do list helps you visualize which items need your immediate attention, and which items you can leave for later. A prioritized to-do list ensures that you’re spending your time efficiently and effectively, which helps you make room in your schedule for homework. So even though you might really want to start making decorations for Homecoming (a B task), you’ll know that finishing your reading log (an A task) is more important.

#2: Use a Planner With Time Labels

Your planner is probably packed with notes, events, and assignments already. (And if you’re not using a planner, it’s time to start!) But planners can do more for you than just remind you when an assignment is due. If you’re using a planner with time labels, it can help you visualize how you need to spend your day.

A planner with time labels breaks your day down into chunks, and you assign tasks to each chunk of time. For example, you can make a note of your class schedule with assignments, block out time to study, and make sure you know when you need to be at practice. Once you know which tasks take priority, you can add them to any empty spaces in your day.

Planning out how you spend your time not only helps you use it wisely, it can help you feel less overwhelmed, too . We’re big fans of planners that include a task list ( like this one ) or have room for notes ( like this one ).

#3: Set Reminders on Your Phone

If you need a little extra nudge to make sure you’re getting your homework done on time, it’s a good idea to set some reminders on your phone. You don’t need a fancy app, either. You can use your alarm app to have it go off at specific times throughout the day to remind you to do your homework. This works especially well if you have a set homework time scheduled. So if you’ve decided you’re doing homework at 6:00 pm, you can set an alarm to remind you to bust out your books and get to work.

If you use your phone as your planner, you may have the option to add alerts, emails, or notifications to scheduled events . Many calendar apps, including the one that comes with your phone, have built-in reminders that you can customize to meet your needs. So if you block off time to do your homework from 4:30 to 6:00 pm, you can set a reminder that will pop up on your phone when it’s time to get started.

This dog isn't judging your lack of motivation...but your teacher might. Keep reading for tips to help you motivate yourself to do your homework.

How to Do Homework When You’re Unmotivated

At first glance, it may seem like procrastination and being unmotivated are the same thing. After all, both of these issues usually result in you putting off your homework until the very last minute.

But there’s one key difference: many procrastinators are working, they’re just prioritizing work differently. They know they’re going to start their homework...they’re just going to do it later.