- Opportunities

- Free Speech

- Creativity and Innovation

- Transparency

- International

- Deeplinks Blog

- Press Releases

- Legal Cases

- Whitepapers

- Annual Reports

- Action Center

- Electronic Frontier Alliance

- Privacy Badger

- Surveillance Self-Defense

- Atlas of Surveillance

- Cover Your Tracks

- Crocodile Hunter

- Donate to EFF

- Giving Societies

- Other Ways to Give

- Membership FAQ

Search form

- Copyright (CC BY)

- Privacy Policy

Unfiltered: How YouTube’s Content ID Discourages Fair Use and Dictates What We See Online

Introduction YouTube's Content ID: Culture of Fear Case Study 1: hbomberguy How Content ID Dictates Expression on YouTube: Practically, Fair Use Has No Effect Case Study 2: Todd in the Shadows Creators Cannot Leave or Meaningfully Challenge the System: Where Am I Supposed to Go? Case Study 3: Lindsay Ellis Conclusion

Introduction

The Internet promised to lower barriers to expression. Anyone with access to a computer and an Internet connection could share their creativity with the world. And it worked— spurring, among other things, the emergence of a new type and generation of art and criticism: the online creator—independent from major labels, movie studios, or TV networks.

However, that promise is fading once again, because while these independent creators need not rely on Hollywood, they are bound to another oligopoly—the few Internet platforms that can help them reach a broad audience. And in the case of those who make videos, they are largely dependent on just one platform: YouTube.

That dependence has real consequences for online creativity. Because YouTube is the dominant player in the online video market, its choices dictate the norms of the whole industry. And unfortunately for independent creators, YouTube has proven to be more interested in appeasing large copyright holders than protecting free speech or promoting creativity. Through its automatic copyright filter, Content ID, YouTube has effectively replaced legal fair use of copyrighted material with its own rules.

These rules disproportionately affect audio, making virtually any use of music risky. Classical musicians worry about playing public domain music. Music criticism that includes the parts of songs being analyzed is rare. The rules only care about how much is being used, so reviewers and educators do not use the “best” examples of what they are discussing, they use the shortest ones, sacrificing clarity. The filter changes constantly, so videos that passed muster once (and always were fair use) constantly need to be re-edited. Money is taken away from independent artists who happen to use parts of copyrighted material, and deposited into the pockets of major media companies, despite the fact that they would never be able to claim that money in court.

Understanding these consequences has never been more pressing, given how many are succumbing to the siren song of automated systems to “fight” online copyright infringement—from the European Union’s Copyright Directive to recent media industry calls for a discussion about “standard technical measures.” In this environment, it is important for lawmakers to understand exactly what such a regime has already wrought. 1

Lawmakers must also understand that the collateral damage of filters would only worsen if they are mandated by law. For one thing, YouTube’s dominance would be assured, as no competitor could afford to pay out to rightsholders the way YouTube does under Content ID, not to mention the costs of creating a similar system. And creators would truly be stuck, with no alternatives that might prioritize their needs over those of major rightsholders. (Most parties involved in Content ID can be content creators, rightsholders, and/or YouTube partners. For simplicity, this paper is always going to refer to those making videos on YouTube as “video creators” and those claiming matches as “rightsholders.”)

This white paper will first lay out how YouTube’s Content ID works and how it interacts with the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA). Then it will discuss fair use and how Content ID restricts creators far beyond what the law allows. Finally, it will explain how Content ID leverages fear of the law, large media companies, and YouTube’s dominance to prevent creators from changing the system, either by challenging it from within or leaving.

To illustrate the issues raised, this paper includes three case studies of long-time video creators who were interviewed about their experiences with Content ID, filters, and YouTube as a platform. For each creator, it is clear that Content ID dominates their creative experience, as does the belief that they have no choice but to be on YouTube. They are:

- Harry Brewis, known online as “hbomberguy.” Brewis is a video essayist covering a variety of topics, with over 600,000 YouTube subscribers. Also interviewed was his producer, Kat Lo.

- Todd Nathanson, known online as “Todd in the Shadows.” Nathanson is a music reviewer and historian, with over 300,000 YouTube subscribers.

- Lindsay Ellis, a New York Times best-selling author, film critic, and video essayist with over one million YouTube subscribers. Also interviewed was her channel moderator, Elisa Hansen.

Ultimately, it is hard to see any benefit to small, independent creators or viewers in mandating filters. Content ID is so unforgiving, so punishing, so byzantine that it results in a system where those who make videos—“YouTubers”—are so dependent on YouTube for audience access, and promotion by its suggestion algorithm, that they will avoid any action which would put their account in jeopardy. They will allow YouTube to de-monetize their videos, avoid making fair use of copyrighted material they want to use in their work, and endlessly edit and re-edit lawful expression just to meet the demands of YouTube’s copyright filter. The result is that, as a YouTuber with over one million subscribers put it, YouTube is a place where “the only thing that matters is are you smarter than a robot.” 2

YouTube’s Content ID: A Culture of Fear

Content ID is incredibly complicated. Even laid out in its simplest form, it is a labyrinth where every dead end leads to the DMCA. This complexity is not a bug; it is a feature. It prevents YouTubers from challenging matches, and lets rightsholders and YouTube expend as little time and resources dealing with Content ID as possible.

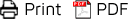

In January 2020, NYU Law School posted a video of a panel called “Proving Similarity,” moderated by Vanderbilt Law Professor Joseph Fishman and featuring Judith Finell and Sandy Wilbur—music experts from opposite sides of the “Blurred Lines” lawsuit, in which the estate of Marvin Gaye claimed Robin Thicke and Pharrell’s song infringed “Got to Give It Up.” The whole point of the panel was to show how experts analyze songs for similarity in cases of copyright infringement, so portions of the songs were played. When the panel was posted to YouTube, it was flagged by Content ID.

While the experts in intellectual property law at NYU Law were certain that the video did not infringe, they ended up lost in the byzantine process of disputing and appealing Content ID matches. They could not figure out whether or not challenging Content ID to the end and losing would result in the channel being deleted. And while it eventually restored the video, YouTube never explained why it was taken down in the first place. 3

All of this is to say that information about how Content ID works comes either from YouTube—which, as NYU Law discovered, is not as helpful as anyone might wish—or from educated guesses made from experiencing the system first hand. Any description of Content ID will by necessity be very involved. If you are confused, then you are in the same position as the YouTubers who deal with Content ID every day. Their livelihoods depend on guessing correctly.

How Content ID Works

There are two sides to Content ID: the side of the creators whose videos are being scanned and that of the rightsholders whose content triggers a match.Here is how YouTube says Content ID works: videos uploaded to YouTube are scanned against a database of files that have been submitted by rightsholders. If there is a match, one of three things happens:

1) The whole video is blocked from view—the public can not see it.

2) The rightsholder “monetizes” the video by having ads placed on it or by claiming the revenue from the ads already on it. In some cases, they will share the revenue with either the video creator or other rightsholders who have matches. 4

3) The video’s viewership statistics will be shared with the rightsholder. 5

Rightsholders can pick one of these three penalties to be automatically applied, requiring no further action on their part unless a video creator wants to challenge the match.

Challenging a match is an involved process. First, the video creator has the option to dispute the match. The rightsholder can either release the dispute, which will eliminate whatever penalty had been automatically applied, or uphold the claim, which will not. Second, the YouTuber can appeal the rightsholder’s choice to uphold the claim. Then the rightsholder can either accept the appeal (which will release the claim and the penalty) or invoke the DMCA takedown process. That is how it is described by YouTube in this chart 6 :

However, this does not capture the lived experience of the few YouTubers who go through the process. Let’s look at just this step:

“Video gets a Content ID claim”: A Content ID claim occurs when the automated algorithm that powers Content ID detects a match between a YouTuber’s video and the database of material submitted by rightsholders. Only certain rightsholders are allowed to add content to the database: those who “own a substantial body of original material that is frequently uploaded by the YouTube creator community.”. 7 This tilts the database and Content ID matches in favor of major movie and TV studios and music labels.

Matches may be made based on mere seconds of material. While YouTube itself does not say on its user support pages how much copyrighted material will trigger a Content ID match, anecdotal evidence puts the threshold under ten seconds. 8 (A ten-hour video of white noise had less than a second claimed by a rightsholder. 9 ) Matches are also made against anything in the database, regardless of any deal made between a rightsholder and a video maker. So, even if a video creator has licensed music for a video—either has paid to use something or was granted permission to use something without paying—it will still trigger a match and thus incur a penalty.

Multiple rightsholders may add the same content to the database. A commercial, a music video, a movie that all use the same song, and so on—will all trigger matches on the same video. This means that multiple entities can make multiple demands on a video, regardless of who the primary rightsholder is. The same white noise video that had less than a second claimed also had five other bad matches made on it. 10 This is because Content ID assumes that anything in the database is under the exclusive control of the rightsholder that added it, rather than something multiple people have the legal right to use.

This means that video creators who did the work of contacting a rightsholder or paid for a subscription that grants them the right to use something will still get punished by Content ID.

Those punishments include, as the YouTube flowchart describes, a video being blocked or money being diverted from the video creator to the rightsholder. Or, a video will have ads put on it against the wishes of the video creator. Depending on circumstances, these penalties can be applied even throughout the period when the video creator is challenging the match.

Finally, Content ID matches can occur at any time. While many matches occur at time of upload, matches can be made when new content is added to the database or whenever the algorithm used by Content ID changes.

If the video has been blocked or monetized for a rightsholder—either depriving the video creator of income or putting ads on a video against their wishes—and the video creator wants people to see it without re-editing, then they have to dispute it. Disputing can mean a blocked video goes back up, but that outcome is not certain. Additionally, while both the match and the penalty are usually done automatically—98 percent of Content ID claims are made automatically—filing an official dispute means drawing the attention of a rightsholder and YouTube. 11 This will likely be the first time in the process a human other than the video creator is involved.

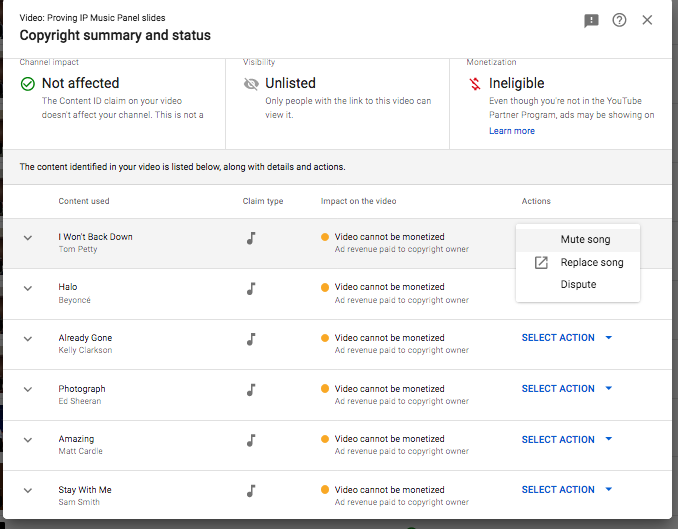

In theory, the rightsholder has 30 days to respond to a dispute. If the rightsholder releases the claim or does not respond, the video is back in control of the video creator. If the rightsholder upholds the claim, the penalty they chose to impose on the video creator continues.

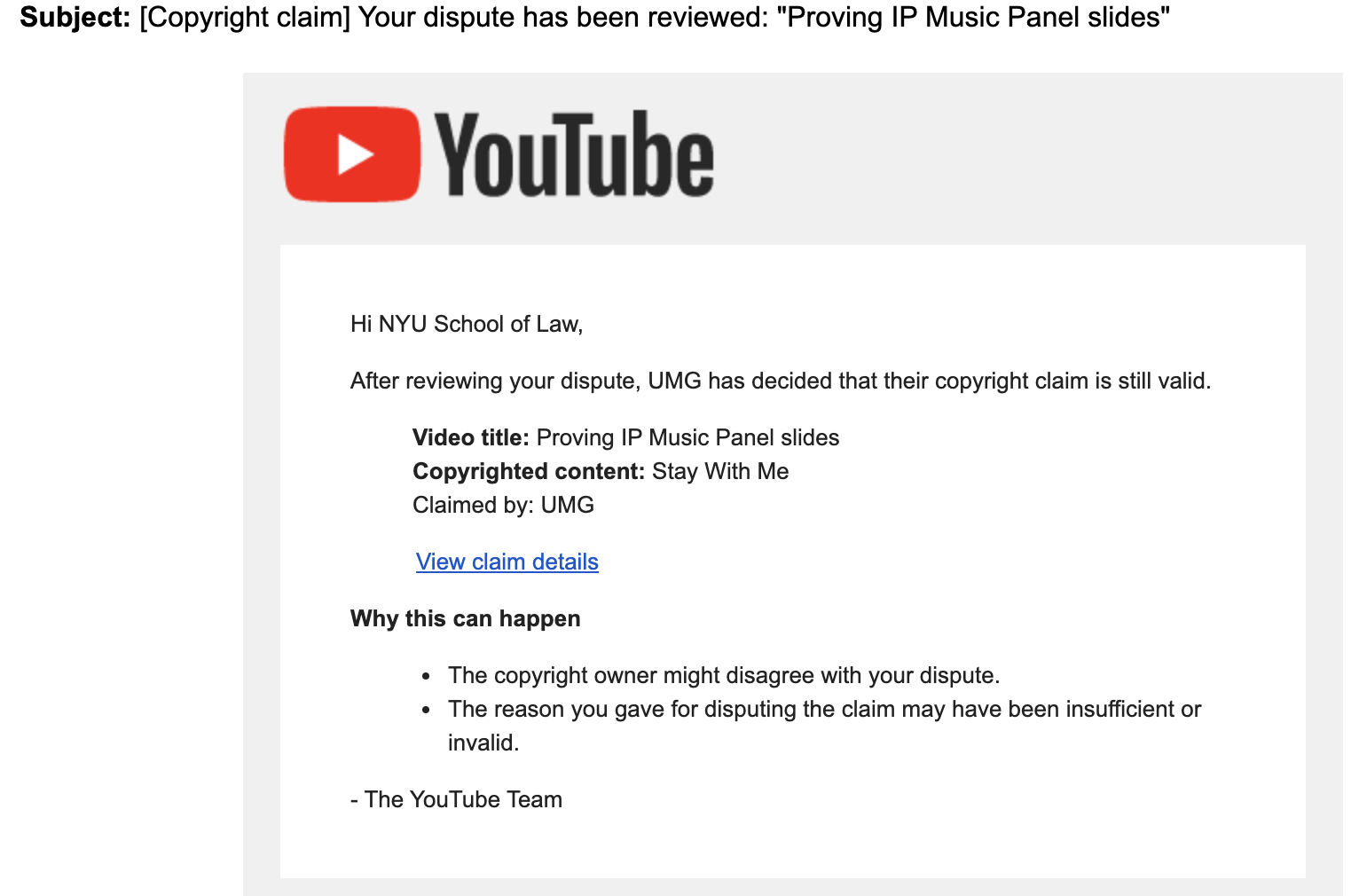

At this point, the video creator can appeal, and then the rightsholder can choose whether to let the claim go, or issue a takedown under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, or DMCA. Rightsholders can also choose to issue a takedown at any point in this process. The takedown demand will take the video down and result in a “copyright strike” against the video creator. Or, the rightsholder can tell the video creator that a DMCA takedown will be issued in seven days, giving the creator the chance to retract their dispute and simply accept the Content ID match. (The interaction of the DMCA and Content ID will be explored in depth in the next section of this paper.)

The few video creators who bother to challenge claims find simply navigating YouTube’s user interface difficult, especially since it changes frequently and without warning. 12 They are also reminded frequently that they risk losing their accounts entirely if they go through this process.

YouTube says that “overclaiming” can lead to a rightsholder being kicked out of Content ID, but the whole system is mostly automated unless there is a challenge of some kind from a video creator. The only check on Content ID is the willingness of video creators to dispute Content ID matches, a willingness that is undermined by the system itself.

Challenging matches mean drawing a rightsholder’s attention to a video. Once that has been done, the rightsholder can, at any point in this process, file a DMCA takedown. And video creators rightfully fear DMCA takedowns.

Content ID Gets Power From Fear of the DMCA

The DMCA takedown process is very intimidating. There’s a built-in possibility of legal action, the requirement to reveal personal information, and the chance of losing your entire account and having all your videos deleted. As a result, video creators try to avoid it at all costs. By creating a private system that dead-ends in the DMCA if disputed, YouTube has leveraged fear of the law to discourage video creators from challenging Content ID. Therefore, it is important to understand how the DMCA works, and how Content ID has been attached to it, in order to understand why video creators are so willing to submit to Content ID.

The complicated nature of Content ID’s relationship to the DMCA and the consequences of the DMCA prevent many from challenging Content ID. In the case of NYU Law’s panel on copyright infringement, while the experts there were confident that their video was not copyright infringement, they were less able to figure out how challenging the Content ID matches would affect their account under the DMCA. They opted not to challenge the matches until they got an answer on that. They never did. Ultimately, the Content ID matches simply went away without explanation. 13

The safe harbor provisions of the DMCA give online service providers like YouTube immunity from liability for copyright infringement by users. As long as YouTube meets the requirements laid on in Section 512 of the DMCA, it cannot be held liable for its users’ infringing activity. Those requirements include, among other things, expeditious removal of material once a valid takedown notice is received, and a “repeat infringer policy” that terminates the account of those repeatedly accused of infringement. 14

“Valid” takedown notices are those that come from the actual rightsholder or an authorized agent of that rightsholder, have all the identifying information required by the DMCA, and are sent under a “good faith belief” that the use of copyrighted material was not authorized by the “owner, its agent, or the law.” However, the threat of liability and the large damage awards possible in copyright cases encourages YouTube and other service providers to take things down quickly in response, even when the notices are flawed.

YouTube and other services rely on another part of the DMCA to serve as a check on false and abusive takedowns: the counter notice. Under the DMCA, if someone receives a bad takedown notice, they can send a counter notice. If the other party does not respond with a lawsuit within two weeks, the service provider can restore the content without fear of liability. Counter notices must contain all of a creator’s contact information, and the creator must consent to jurisdiction in a United States Federal District Court. 15

In general, large numbers of takedown notices are flawed. Counter notices are rarely used and are not protecting users’ rights as intended. 16 On YouTube, specifically, the platform rarely scrutinizes takedowns, and creators rarely send counter notices. In 2017, YouTube received 2,500,000 takedowns targeting 7,000,000 videos, and rejected or requested more information for takedowns on just 300,000 videos. By contrast, it received only 150,000 counter notices for 200,000 videos. YouTube rejected 2/3 of these counter notices out of hand. 17

In theory, another provision of the DMCA, Section 512(f), should help discourage false takedowns. Section 512(f), allows creators to sue for damages, including attorneys fees, if they are the victim of a bad faith DMCA notice. 18 In practice, it has not served as much of a deterrent.

First, such challenges are expensive and public. What is worse, courts have interpreted Section 512(f) to effectively require subjective knowledge that the takedown is improper. In Lenz v Universal , the Ninth Circuit correctly held that the DMCA requires a rightsholder to consider whether the uses she targets in a DMCA notice are actually lawful under the fair use doctrine. However, the appeals court also held that a rightsholder’s determination on that question passes muster as long as she subjectively believes it to be true.

This leads to a virtually incoherent result: a rightsholder must consider fair use, but has no incentive to actually learn what such a consideration should entail. After all, if she doesn’t know what the fair use factors are, she can’t be held liable for not applying them thoughtfully. Particularly relevant to the subject of this paper, Judge Milan Smith noted in his dissent that “in an era when a significant proportion of media distribution and consumption takes place on third-party safe harbors such as YouTube, if a creative work can be taken down without meaningfully considering fair use, then the viability of the concept of fair use itself is in jeopardy.” 19 If the sender of an improper takedown cannot suffer liability under Section 512(f) no matter how unreasonable her belief, the Lenz decision effectively eliminates Section 512(f) protections for even classic fair uses upon which creators rely. 20

One of the other requirements for safe harbor protection under the DCMA is the aforementioned “repeat infringer policy,” that terminates the account of those repeatedly accused of infringement. YouTube fulfills this requirement with its infamous “three strikes”rule. On YouTube, getting three copyright strikes—in other words, having a video removed three times with an official DMCA notice—within 90 days will lead to a creator losing their account, having all their videos removed, and losing the ability to make new channels.

How Content ID Leverages Fear of the DMCA

Losing one’s account, having one’s videos deleted, or taking the chance on a lawsuit against a better-funded and resourced rightsholder are all too great a risk for most independent video creators. The DMCA hangs over the entire Content ID process—in comparison to the DMCA’s possible penalties, Content ID seems like a better bet for video creators, no matter how unfair it actually is.

On the one hand, it seems like YouTube is merely advising video creators of the risks when it repeatedly reminds creators that disputing Content ID matches could result in a DMCA claim, a strike, and, if enough strikes accumulate, the loss of their channel. 21 On the other, it also seems YouTube incentivizes video creators to accept unfair restrictions and penalties by holding over their heads the chance of losing their entire account under the DMCA.

Remember, if a video creator disputes the Content ID claim and the rightsholder—who has nothing to lose—rejects the dispute, the video creator can appeal. But if the rightsholder objects to the appeal, the only option left is a DMCA takedown, i.e., a copyright strike. Moreover, YouTube gives rightsholders an additional club by giving the option of a “scheduled copyright takedown notice.” 22 With this, rightsholders can let a video creator know that if they do not give up on their dispute or appeal within seven days, they will get a DMCA takedown and therefore a copyright strike.

Rightsholders also have the right to file a DMCA takedown at any point in the Content ID process. Disputing or appealing Content ID decisions may increase the chance of this happening, because it calls the rightsholders’ attention to the video in question.

And, as one YouTube creator noted, that is “is especially a problem when the video is critical.” 23 One of the case studies in this paper received DMCA takedowns only after he challenged Content ID claims. 24 Disputing a claim opens the creator up to DMCA abuse—that is, the use of DMCA takedowns to remove non-infringing material in order to silence criticism or for some other, non copyright-related, reason. This leads to the video being blocked and the video creator to get a copyright strike. Therefore, many video creators have made the calculation that simply accepting a Content ID match and either acquiescing to the penalty or re-editing the video is the safest course of action.

As another YouTube creator sums up the situation: “People are so afraid of being deplatformed or losing that income that it is sort of a culture of fear.” 25

Case Study 1: hbomberguy

Harry Brewis, known online as “hbomberguy,” is a video essayist with over 600,000 YouTube subscribers. In July 2020, he posted a video called “RWBY Is Disappointing, And Here’s Why,” which has been viewed over 1.5 million times. The review criticizes an animated series called RWBY, using clips as part of that criticism. However, prior to posting the video, Brewis and his producer, Kat Lo, found themselves dealing with a very complicated Content ID situation.

Because of the length of the video—two and a half hours—Brewis uploaded 20-minute chunks of it to YouTube as he was editing, so that he could see what triggered Content ID and make changes. Each portion of the video passed Content ID. But, after uploading the full video, Brewis saw it come back with one or two Content ID matches. He re-edited the video, only to find new matches. He repeatedly edited and uploaded the video, getting a small number of matches every time. “The shocking part was every time it happened I thought, ‘Oh that’s great, it only got hit twice, that’s really encouraging’ and then the next one would get hit three times,” said Brewis.

Part of the problem was that the show Brewis was criticizing, RWBY, is owned by a company called Rooster Teeth, which has set Content ID to automatically block any video with a match. Rooster Teeth tells users to dispute the match— a response that, as noted, is intimidating to creators and actively discouraged by YouTube. If creators do dispute, Rooster Teeth either monetizes the video for itself or “removes the claim,” based on its own determination of whether the use is lawful. 26 Rooster Teeth monetized at least one of Brewis’s drafts of the video, meaning that it would make money off of the review and Brewis, who planned to donate the proceeds, would not.

Eventually, Brewis manually checked every part of his video to make sure no clip was over five seconds. Overall, the process of re-editing the video to pass Content ID took a week and a half of extra work and cost $1,000 in fees to a lawyer to assess the clips. Brewis noted that YouTube’s own recommendations make this problem very clear. “This is my favorite part of the whole process,” said Brewis, heavy with irony. “YouTube’s system is such a mess that when you are uploading the video, it says ‘upload it unlisted and wait a while to see if it gets picked up because it will take a while.’ It just warns you, ‘This will be strange.’”

“A big problem on top of that is the appeals process. Where if you say, ‘No, this is fair use,’ the person who holds the copyright gets to decide if it is fair use,” said Brewis. He and his producer also emailed YouTube. As a “partner” channel with YouTube, they thought they could contact a human representative and ask for help. The partner program gives YouTube creators access to a suite of resources—access to editing tools, the stripped-down version of Content ID, and, in theory, greater support from YouTube’s Creator Support teams. YouTube channels get “partner” status through meeting a threshold for subscribers and hours watched, as well as a few other requirements like having the channel linked to Google’s ad system, Adsense. 27 When Brewis reached partner status, he was contacted by someone who worked for YouTube who claimed to be “his” representative at the company. But during this problem, Brewis contacted this person, only to be told that they only rarely help people and that direct contact with a YouTube representative only lasts for six months after reaching partner status.

This experience shaped the entire video-making process for Brewis. He has an upcoming video timed to an anniversary, and he “has” to finish a draft and upload it to YouTube weeks before the scheduled publish date because “If I try uploading it on the day, it might not be allowed.”

Brewis’s final word on Content ID? “It cost me a lot of time, and revenue, and emotional damage. If Content ID were a person, I would have taken him to court.”

How Content ID Dictates Expression on YouTube: Practically, Fair Use Has No Effect

Content ID pervades the lives of YouTube creators. Which makes sense because Google claims 98 percent of copyright claims are handled through Content ID. 28 So, using Google’s own numbers, if YouTube received 2,500,000 million DMCA takedowns in 2017, that means 122,500,000 claims were handled by Content ID that year. 29

Content ID scans its creations when they are uploaded and periodically thereafter. It can prevent a video from ever being seen or from making any money. What and how Content ID makes matches therefore determine what viewers get to see—not free expression, fair use, or what a creator thinks makes for the strongest video.

It is important to underscore a few key points about fair use because it is central to much of what YouTube creators do. The Internet opened up the world of criticism and commentary to anyone with a computer. Those who were traditionally locked out of traditional careers in criticism or simply wanted to be their own boss have found a place online. And those who want to make parodies or mashups or other transformative works have tools and audiences never before available to them.

Fair use, enshrined in law as Section 107 of the Copyright Act, allows the creators to do this work without getting permission or paying a rightsholder. Whether or not a use is “fair” is a context-dependent determination made based on four factors:

(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

(2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

(4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work. 30

The first factor often turns on whether a use is “transformative,” i.e, whether it serves a new and different purpose from that of the original. Criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, and research are all classic fair uses that can be found on YouTube 31 And because YouTube is a video-streaming site those uses often involve bits of copyrighted audio and video material.

The second factor considered whether the original work is more or less creative, and also whether it is published or unpublished. Where a work is long since published and/or highly factual, this factor will tend to tilt in favor of fair use.

The third factor considers whether the user has borrowed more or less than what is needed to serve the purpose identified in the first factor. Importantly for this analysis, the third factor does not have a bright-line limit on how much copyrighted material can be used—you can take as much or as little as you need for your purpose. So while the use may be a few seconds, as for some kind of music criticism, it can also be the whole piece, such as in a music parody. 32

Finally, the fourth factor concerns whether the use caused harm to the rightsholder by replacing the original work in the market. Crucially, the “harm” considered here does not include harm caused by parody or a negative review that suppresses demand for the original by pointing out its flaws. 33 Instead, it considers whether the use in question could substitute for the original.

Let us look at the ways in which Content ID undermines the first, third, and fourth factors in particular, thereby restricting online content beyond what copyright law actually requires.

Transformative Music Content Suffers Because Content ID Disproportionately Affects Audio Material

While the law does not make fair use of music more difficult to prove than fair use of any other kind of work, Content ID does.

The key problem is one of mechanics. It is easier for Content ID to find a match just on a piece of audio material compared to a full audiovisual clip. And then there is the likelihood that Content ID is merely checking to see if a few seconds of a video file seems to contain a few seconds of an audio file.

For an example of the mechanical problem, classical musicians filming themselves playing public domain music— compositions that they have every right to play, as they are not copyrighted—attract many matches. 34 This is because the major rightsholders who have qualified to join Content ID have put many examples of copyrighted performances of these songs in the system. It does not seem to matter whether the video shows a different performer playing the song—the match is made on audio alone. This drives a lawful use of material off YouTube.

Similarly, music that is part of a larger work will be claimed, but the audiovisual work as a whole will not. So creators commenting on a film that includes music will still get a match for that music, but not the film. 35 It is therefore easier to choose to include parts of the film that have no music, even if it is not the best illustration of their point. Or, as YouTube itself advises, to remove or replace the music, which could mean compromising the point being made about that part of a film. YouTube even gives creators a tool set that makes removing portions of a video, removing music, or replacing music easier. 36

It obviously does not matter to Content ID if the music is being transformed. While those commenting on film or TV may be able to find a way to get their point across without music, music reviewers and historians cannot. At least, not in a way that is clear and interesting for the audience.

Content ID’s sensitivity to audio material and the large number of musical partners that choose to monetize matches makes it difficult to succeed on YouTube in anything music-related. Especially for those just starting out, who cannot rely on the external revenue streams that more-established creators have built (sponsorships, crowdfunding, etc.).

The difficulty of getting music clips past Content ID explains the dearth of music commentators on YouTube. 37 It is common knowledge among YouTube creators. Ellis, not normally a music reviewer, did not even bother trying to put ads on a video she did about music because “this is why you don’t make content about music”—the advertising revenue is going to go to the labels. 38

A whole genre of art is covered far less than others simply because Content ID makes more music matches than audiovisual ones. While fair use would protect music reviews as transformative, Content ID makes doing them on YouTube nigh impossible.

Creators Edit to Content ID’s Time Constraints

Content ID only determines whether a few seconds of a video matches a few seconds of something in its database. So while fair use has no bright-line rule about how much a creator can or cannot use, Content ID does. And it’s just a few seconds. 39

Because Content ID matches can result in either a rightsholder getting the revenue of the video or a video being blocked (also resulting in a loss of revenue for a creator), there is every incentive for video creators to simply make videos that will not get Content ID matches.

Creators know that, if a video is blocked because of a content ID match, they will suffer. It does not matter if they dispute it and win; they need to avoid it happening in the first place. Internet publishing is time-sensitive, and an ill-timed block can severely impact views and, therefore, revenue. To mitigate this risk, YouTubers again and again make creative decisions based not on what will strengthen their video, but on what will allow them to pass Content ID.

Avoiding a match is especially important because, although Content ID claims to have a timeframe for disputes and appeals, that claim does not comport with the practical experience of both Nathanson and Ellis. For Brewis’s producer, Kat Lo, the potential delay created an additional concern: “The thing we had to prepare for was the circumstance where if it got Content IDed and blocked after it had been out for a day, it would completely tank the views,” said Lo. “So it would not get the views it normally would,” which would cost them income and placement in search results and recommendations. 40

Therefore, creators have to ensure that the copyrighted material they use is under Content ID’s threshold for matches. YouTubers report keeping their clips under seven seconds if possible, under ten at most. “I understand fair use as if I’m using copyrighted material for commentary, or critique, or review then I can use it. That’s how I understand it legally. Practically, it has absolutely no effect on what I do,” said music reviewer Nathanson. 41 While every clip he uses is for commentary or criticism, the most important factor in his calculations is not fair use but whether the clip will get past Content ID.

Thus, instead of showing audiences exactly what they are criticizing or the best illustration of an issue in an educational setting, creators pick an example that is under ten seconds long. Their comments are thus built around Content ID’s restrictions, not what they have the legal right to use.

Rather than wait the indeterminate time period for a Content ID dispute to be resolved or chance a DMCA takedown and resulting copyright strike, YouTube creators will also, like Brewis in the case study above, endlessly edit and re-edit videos until they pass Content ID. In some cases, they will re-edit videos that had been available for years—and passed Content ID all that time—but then suddenly received new claims.

Some of those new claims may be the result of new works being added to the Content ID database, or changes in the Content ID algorithm. 42 For creators who have hundreds of videos, this can mean weeks of work either re-editing or disputing the claims. 43

Content ID Directs Money Away From Creators and to Rightsholders

When a rightsholder joins Content ID, it gets to choose what penalty is automatically applied to any video that contains its copyrighted material. Ninety percent of Content ID partners choose to automatically monetize a match—that is, claim the advertising revenue on a creator’s video for themselves—and 95 percent of Content ID matches made to music are monetized in some form. 44

That gives small, independent YouTube creators only a few options for how to make a living. Creators can dispute matches and hope to win, sacrificing revenue while they do and risking loss of their channel. Fewer than one percent of Content ID matches are disputed. 45

Those who have large enough followings can use alternative platforms like Patreon, which allows fans to directly contribute to their favorite creators, often with tiers that give access to extras, merchandise, or so on for higher donations. YouTubers also get sponsorships directly from companies, sell merchandise, or share affiliate links. 46 As an example, Ellis has over 1,000,000 subscribers on YouTube. She estimated she makes five times as much from Patreon and twice as much from sponsorships as she does from YouTube. 47

But even that can come with dangers. At one point, a Content ID match put ads on a video that Ellis had purposefully not monetized, since she had a sponsorship deal that precluded other promotions. Content ID’s automation potentially put her in violation of her contract. 48

Another option available to YouTube creators of a certain size is simply letting the money go. Nathanson chose for years to let major labels—he reviews mostly well-known artists and songs from major labels—claim all the advertising revenue on his reviews through Content ID. Because he built a loyal fanbase prior to his move to YouTube, they have followed him to Patreon. 49 This is the only reason he can afford to let Content ID divert advertising revenue away from him and to the rightsholders whose work he critiques.

This is a patently absurd result. The law does not require critics to get permission from or share revenue with the rightsholder of the work they are critiquing. Fair use does not let rightsholders claim market harm in court from a review. But Content ID does let rightsholders claim the revenue from them.

While both Ellis and Nathanson have the right, under fair use, to use copyrighted material without paying rightsholders, Content ID routinely diverts money away from creators like them to rightsholders in the name of policing infringement. While fair use is an exercise of your First Amendment rights, Content ID forces you to pay for that right. WatchMojo, one of the largest YouTube channels, estimated that over six years, roughly two billion dollars in ads have gone to rightsholders instead of creators. 50

YouTube does not shy away from this effect. In its 2018 report “How Google Fights Piracy,” the company declares that “the size and efficiency of Content ID are unparalleled in the industry, offering an efficient way to earn revenue from the unanticipated, creative ways that fans reuse songs and videos.” 51 Hansen, who is employed by Ellis to moderate and manage her channel, said that she felt that YouTube sells Content ID to the entertainment industry as a way of making money off of others’ transformative works and that YouTube discourages disputes so it can keep paying large rightsholders. 52

The final option for creators is simply editing videos until no Content ID matches occur, guaranteeing that they get the advertising revenue from their hard work.

Content ID prevents a whole medium from being meaningfully critiqued and taught, penalizes creators for using more than a few seconds of a work—no matter how they use it, and diverts money away from creators and to righsholders. All of these things are incompatible with fair use.

Case Study 2: Todd in the Shadows

Todd Nathanson is a music reviewer and historian who makes videos reviewing hit songs, going through the history of one-hit wonders, and dissecting the history and quality of albums that ended musicians’ careers. Online he is known as Todd in the Shadows and has over 300,000 YouTube subscribers.

Nathanson has been making videos online for almost 11 years, starting in September of 2009. He switched to YouTube when his previous platform, Blip.tv, went defunct. He has noticed a clear change from Blip to YouTube, saying, “On Blip we were largely protected from copyright. On YouTube it is a constant presence in my life, Content ID and the DMCA.”

Nathanson has had no help from YouTube, explaining that the system “is very byzantine and it’s changed many times and they don’t inform us of how things work.” (Another Youtuber used the same term). So his understanding of what to do is “100% from other YouTubers and almost nothing from YouTube.”

His understanding is that Content ID is an algorithm that scans videos for copyrighted material and “if it’s more than whatever arbitrary length of time they have chosen this week, then you will get flagged.” He can tell when there has been a major change to Content ID because hundreds of videos that had previously passed are flagged. While he edits newer videos to pass Content ID—“I do try and limit how much I use of copyrighted material just trying to keep on the right side of Content ID, as I think do most people who do what I do”—older videos have been taken down and only some of them have been reinstated. He says, “If I get flagged I can claim I was using it for fair use, but I don’t think they care.”

Nathanson says “I try to use clips as short as possible. Which affects what I say, how I say things, how I have to word things. It’s about how much I can get past Content ID, not how much I want to discuss, which is a frustration.”

But Content ID still claims the revenue generated by advertisements on the video for someone else. Explains Nathanson:

Every single one of my videos will get flagged for something and I choose not to do anything about it, because all they’re taking is the ad money. And I am okay with that, I’d rather make my videos the way they are and lose the ad money rather than try to edit around the Content ID because I have no idea how to edit around the Content ID. Even if I did know, they’d change it tomorrow. So I just made a decision not to worry about it.

Nathanson is lucky enough to be able to make a living on Patreon instead of from YouTube’s advertising, but even so must rely on YouTube. Asked whether he has the choice to leave, he answers, “No, obviously not. I had Blip.tv for a while, and that came with its drawbacks. It was less public so you got less views. But now there is absolutely no way I could do this without YouTube.”

Creators Cannot Leave or Meaningfully Challenge the System: Where Am I Supposed to Go?

Between the size of YouTube and the confusing and intimidating nature of Content ID, creators feel they have no choice but to acquiesce to whatever YouTube demands.

For example, one YouTuber had to rebuild his channel after being laid off from making videos for the videogame website Kotaku. He now makes the same videos himself as an independent small business. Having gone through the process of reestablishing a YouTube channel, he said he is even more cautious about losing the new one he has built. 53 He says that for the kinds of videos he makes, there is nowhere but YouTube. Ellis echoed that sentiment when asked if she had a choice of platforms. “No,” she said. “Where am I supposed to go?” 54

Creators Have Been Conditioned Against Challenging Content ID

YouTube creators feel they do not have any leverage in challenging Content ID. There is little communication from YouTube itself—creators mentioned a need for a dedicated helpline, with a human being on the other end, as a way to improve the system.

The most success creators have is when they go outside the system itself. Ellis found the email for someone at YouTube who helped for a while. 55 Brewis tweeted about the problems he was having and was contacted by the rightsholder. 56 NYU Law School eventually had its matches vanish after it also reached out to YouTube through personal connections. 57

For creators with many videos who get large numbers of claims every time Content ID changes, disputing becomes a game in which they have to make sure they are never in danger of crossing over into more than three strikes in a 90-day period and therefore in danger of losing their account. 58

The only check on Content ID is the willingness of YouTubers to dispute Content ID matches, a willingness, remember, that is undermined by the system itself. YouTube only allows certain rightsholders to add material to the Content ID database, from which matches originate. So it is not small creators guarding their livelihoods who benefit from Content ID. Instead, it is the largest media companies—those with a lot of resources—that small, independent creators cannot hope to match. The same imbalance that prevents counter notices under the DMCA is amplified under Content ID. And then, fear of the DMCA is used to buttress it.

The desire to fight Content ID simply is not there. “It’s such a risky thing to consider doing, especially when your livelihood is on the line, that I’ve never let anything get that far,” said Brewis. 59

All YouTube creators interviewed said they rely on a community of fellow creators to help them navigate the system. But while Ellis and her moderator—also a YouTuber—urge other creators to dispute bad Content ID claims, most people are simply too scared to take the chance. Ellis summed up the situation as “[t]hey try to scare you out of disputing Content ID claims.”

And it succeeds. YouTube reported in 2018 that 98 percent of copyright issues are handled through Content ID, not DMCA notices and counter-notices. Disputes are rare. YouTube touts that “fewer than 1 percent of Content ID claims are disputed and of that number, over 60 percent resolve in favor of the uploader.” 60

Lack of Meaningful Competition Keeps Creators From Leaving YouTube

There is a terrible, circular logic that traps creators on YouTube. They cannot afford to dispute Content ID matches because that could lead to DMCA notices. They cannot afford DMCA notices because those lead to copyright strikes. They cannot afford copyright strikes because that could lead to a loss of their account. They cannot afford to lose their account because they cannot afford to lose access to YouTube’s giant audience. And they cannot afford to lose access to that audience because they cannot count on making money from YouTube’s ads alone, partially because Content ID often diverts advertising money to rightsholders when there is Content ID match. Which they cannot afford to dispute.

Content ID is restrictive, confusing, and difficult to navigate. But video creators know there is nothing that can compete.

YouTube is the largest video streaming website—by far. As of September 2019, YouTube averaged 163 million monthly average users, compared to Netflix’s 46 million, Hulu’s 26 million, Amazon Prime’s 16 million, and Vimeo’s 15 million. 61 Almost 20 percent of Americans watch YouTube for more than three hours a day. 62

According to a study of the online creative economy, in 2017, over two million U.S. creators posted on YouTube, earning about four billion dollars per year. 63 Between 2016 and 2017, the number of U.S. creators grew by 81 percent and the amount of money they earned grew by 21 percent. None of the other platforms included in this study had anywhere near YouTube’s growth in number of creators. 64

Ellis and Nathanson both became reliant on YouTube when the competitor service they were on was shut down in 2015, cementing YouTube’s dominance. In 2010, 24 hours of video was uploaded to YouTube every minute. 65 Now, it is more than 500 hours of video per minute. 66 In 2010, more than two billion videos were being watched per day. 67 Now, that number is over five billion. 68

Ironically, creators need YouTube because they cannot rely on making money from YouTube. They need the audience YouTube provides in order to amass enough fans to be attractive to sponsors or convert some of that audience to pay them directly through Patreon or a like service because of YouTube’s rules about monetization and the way Content ID diverts advertising revenue away from them.

YouTube’s dominance also means that the decisions it makes—how Content ID works, what policies it enacts, what kinds of videos it promotes, what it demonetizes 69 —become de facto norms for the entire online video industry.

Case Study 3: Lindsay Ellis

Lindsay Ellis is a video essayist and New York Times best-selling author with over one million YouTube subscribers. She has been making videos online for about 12 years, starting out on a platform called Revver, which no longer exists, and then Blip.tv, which also no longer exists, and was then “shunted on to YouTube for lack of better options.”

Here is how Ellis describes Content ID:

It’s almost like a game. You don’t know exactly what the rules are, but you have a general idea of what the rules are. Unless you are resigned to going completely unmonetized, which I did do for a recent video because it just had too many clips in it. So it’s an issue of uploading your video, re-editing, and doing it again and again until it doesn’t ping Content ID.

Ellis eventually found an email address for a YouTube help desk unrelated to Content ID that was a) answered by a human who was b) willing to push the disputes up the chain. Some other claims against Ellis’s channel were resolved not through YouTube’s appeals system, but by getting the claimants’ contact information and sending letters directly to them explaining that Ellis was willing to assert fair use in court, which got the claims released. Ellis ended up going outside YouTube’s system to fix problems generated by the system, which is dysfunctional.

Ellis’s manager, Elisa Hansen, eventually learned that once a dispute is denied, you have seven days to withdraw the appeal of a dispute denial and avoid it becoming a DMCA claim and therefore a strike. But, says Hansen, that knowledge did not come from anyone at YouTube but through “trial and error. We took that risk.” Hansen says that after a major change to the Content ID algorithm, it took three weeks to deal with the new claims that came in. During our interview, Ellis and Hansen also discovered that YouTube had changed its system again, and they struggled to figure out how to look up how many Content ID claims they had and what they were.

Ellis and Hansen have a nuanced understanding of fair use. But Ellis feels like she had to become a fair use “unexpert” because “it’s never about fair use, it’s about beating Content ID.” Hansen added, “If I understand fair use but I’m still losing these appeals, what does it matter? I’m becoming an expert in how to use the YouTube system.”

For Ellis and Hansen the most frustrating parts of Content ID are the lack of human review and YouTube’s failure to follow its own rules. For example, after appealing a denial of a dispute, YouTube advised them that the claim would be released if the rightsholder did not respond within 30 days. Instead the claim lingered far past that month.

Ellis’s account sat with hundreds of Content ID claims for years because they did not know they could contest them. Eventually, once they decided to assert fair use, risking the DMCA strikes and litigation, they found that they could have been getting the revenue from advertisements the whole time. “We were scared to do it because of the way YouTube wants you to think it works. Like, ‘are you sure you want to do this? You could lose your channel,’” said Hansen.

The only advice they can give other YouTubers is “make the clips shorter or cut out a few frames or put licensed music under the video.” Ellis says she finds herself wondering “why I bothered playing by the rules all these years because fair use doesn’t matter. Content ID is all that matters.”

Because of the way that YouTube pays, Ellis considers YouTube mostly a promotional tool, rather than a viable source of income. Ultimately, says Ellis, “Content ID is pinging clips I am actually discussing, which is a pretty clear case of fair use. Or it would be, if they looked at that, but they don’t.”

The restrictions that Content ID puts on expression—and the pervasiveness that YouTube’s dominance gives those restrictions—not only harm creators, they harm culture as a whole.

The Internet was supposed to open up the world of creativity, not only lowering barriers of entry for creators but expanding the options for the rest of us. With so much of the creative arts dominated by just a few large companies—the very few music labels, movie studios, and TV networks—we were supposed to have more of a say in what we saw, instead of those few gatekeepers. We were also supposed to get more information from a diversity of voices. Criticism and commentary from those who traditionally could not get jobs doing that work in traditional outlets.

We all have limited time and money, and we should be able to choose how to spend both. A movie review, for example, helps people decide whether they want to spend their hard-earned money and/or time on a ticket, DVD, or stream of it. But in the current system, takedowns and filters become barriers to informed decisions.

When dealing with the Internet, it is all too easy to assume that problems can be solved by some novel technology. Calls for platforms to do more about copyright infringement, either through mandating action or encouraging private agreements between rightsholders and tech companies, often lead to copyright filters like Content ID.

While rightsholders often complain about YouTube, the new generation of creators trying to independently make and share work online is even more trapped and exploited by the platform. We must take care not to implement laws, regulations, or incentives that are easy for YouTube to comply with by passing the buck to the creators whose work fuels its site.

Nathanson has only one answer to the question of what could make filters like Content ID better:

“I wish Content ID wasn’t there. That is basically the long and short of it. I know YouTube has a copyright infringement problem with legit abusers, but for my purposes I’d like it gone. That’s the only thing I can think of to say."

See: Katharine Trendacosta and Corynne McSherry, Copyright and Crisis: Filters Are Not the Answer, EFF (April 21, 2020), available at https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2020/04/copyright-and-crisis-filters-are-not-answer (Accessed September 29, 2020); Christoph Schmon, Copyright Filters Are on a Collision Course With EU Data Privacy Rules, EFF (March 3, 2020), available at https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2020/02/upload-filters-are-odds-gdpr (Accessed September 29, 2020). ↩

Lindsay Ellis and Elisa Hansen, Interview with author, July 31 2020. ↩

Engelberg Center on Innovation Law & Policy NYU School of Law, How Explaining Copyright Broke the YouTube Copyright System, available at

https://www.law.nyu.edu/centers/engelberg/news/2020-03-04-youtube-takedown?fbclid=IwAR1ruv0KnYwVawITN1uEv9J5FCxzVkPEUySSVEEZ7S78eeKFRmOX2tefnNA (last accessed Nov. 25, 2020). ↩

It is worth noting that the phrasing around this option can get a little confusing. Video creators will often lump Content ID monetization in with “demonetizing.” Demonetizing is when YouTube prevents ads from even appearing on a video, usually because the subject is one advertisers do not want to be associated with or because a video has been reported for having such content. (This is a tactic, much like DMCA abuse, used to harm creators whom someone disagrees with or wants to harass in some way.) Content ID monetization still places ads on a video, but the video creator’s share of the revenue diminishes or vanishes. In both cases, they may see no money from the video they have made, but the difference is in whether or not there are ads at all. ↩

Content ID Overview, YouTube Creator Academy, available at https://creatoracademy.youtube.com/page/lesson/respond-to-content-id-claims_copyright-content-id-overview_image?cid=respond-to-content-id-claims&hl=en (last accessed November 30, 2020). ↩

Content ID Overview, YouTube Creator Academy, available at https://creatoracademy.youtube.com/page/lesson/respond-to-content-id-claims_copyright-content-id-overview_image?cid=respond-to-content-id-claims&hl=en (last accessed November 30, 2020) ↩

YouTube Help, How Content ID Works, Support.google.com,

https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/2797370?hl=en&ref_topic=9282364 (last visited Sep 29, 2020) ↩

From our interviews, Ellis and Nathanson say they keep their clips to under ten seconds to pass Content ID. Brewis keeps his to under five. ↩

EFF Takedown Hall of Shame, “Ten Hours of Static Gets Five Copyright Notices,” Electronic Frontier Foundation,

https://www.eff.org/takedowns/ten-hours-static-gets-five-copyright-notices, (last visited Sep 29, 2020). ↩

How Google Fights Piracy at 24. ↩

During the author’s interview with Lindsay Ellis and her moderator Elisa Hansen, Ellis and Hansen found that the interface had changed since they last used it and could not even navigate to see how many Content ID claims Ellis’ channel had. (Ellis and Hansen interview.) ↩

Engelberg Center on Innovation Law & Policy NYU School of Law ↩

17 USC § 512. ↩

17 USC § 512(g)(3). ↩

See Jennifer M. Urban, Joe Karaganis, & Brianna Schofield, Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice 44 (UC Berkeley Public Law Research Paper No. 2755628, Mar. 24, 2017), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2755628. ↩

How Google Fights Piracy, 30-31. ↩

17 USC § 512(f). ↩

Lenz v. Universal, 815 F.3d 1145, 1160 (9th Cir. 2016) ↩

Ellis and Hansen interview. ↩

What is a scheduled copyright takedown request?, Support.google.com, https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/9167045?hl=en (last visited November 30, 2020). ↩

Harry Brewis and Kat Lo, Interview with author, September 23, 2020 ↩

Nathanson interview. ↩

Ellis and Hansen interview. ↩

Content Usage Guidelines, Roosterteeth (2020),

https://support.roosterteeth.com/hc/en-us/articles/360045358831-Content-Usage-Guidelines (last visited Sep 29, 2020). ↩

YouTube Partner Program overview & eligibility - YouTube Help, Support.google.com, https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/72851?hl=en (last visited Sep 29, 2020). ↩

That is the most conservative estimate, since the 2,500,000 actually affected 7,000,000 videos. But for the sake of giving the benefit of the doubt, we are using the lower number. ↩

17 USC 107 ↩

Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569, 584 (1994). ↩

Id at 592, citing Fisher v. Dees, 794 F.2d 438 (9th Cir. 1986). ↩

Micheal Andor Brodeur, Copyright Bots and Classical Musicians Are Fighting Online. The Bots Are Winning. Washington Post (May 21, 2020),

https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/music/copyright-bots-and-classical-musicians-are-fighting-online-the-bots-are-winning/2020/05/20/?arc404=true (last visited Sep 29, 2020). ↩

Taylor B Bartholomew, The Death of Fair Use in Cyberspace: YouTube and the Problem With Content ID, 13 Duke Law & Technology Review 66-88, 84, (2015). ↩

Katharine Trendacosta, A Tool That Removes Copyrighted Works Is Not a Substitute for Fair Use, EFF (January 20, 2020),

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2020/01/tool-removes-copyrighted-works-not-substitute-fair-use (last visited Sep 29, 2020). ↩

Todd Nathanson (@ShadowTodd), Twitter, November 7, 2019, 10:05 PM, https://twitter.com/ShadowTodd/status/1192684569427877888. ↩

Nathanson and Ellis keep their uses to under ten seconds, Brewis to under five. ↩

Brewis and Lo interview. ↩

Todd Nathanson, Interview with author, September 9, 2020. ↩

See: Todd in the Shadows (@ShadowTodd), Twitter, May 2 2019, 1:05 PM. https://twitter.com/ShadowTodd/status/1124766905057841152 ↩

How Google Fights Piracy, 14, 25. ↩

Id at 28. ↩

BBC, Evan Edinger: The Five Ways YouTubers Make Money, BBC (December 17, 2017), http://www.bbc.co.uk/newsbeat/article/42395224/evan-edinger-the-five-ways-youtubers-make-money (last visited Sep 29, 2020). ↩

Lindsay Ellis (@thelindsayellis), Twitter, October 23, 2019, 11:52 AM, https://twitter.com/thelindsayellis/status/1187079685705879552. ↩

Todd in the Shadows (@ShadowTodd), Twitter, November 7, 2019, https://twitter.com/ShadowTodd/status/1192684000306970625 ↩

See WatchMojo, E Are Rights Holders Unlawfully Claiming Billions in AdSense Revenue?

(May 9, 2019), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-w1f3olwqcg&feature=youtu.be

(last visited Sep 29, 2020). ↩

How Google Fights Piracy, 25. ↩

Chris Person, Interview with author, September 23, 2020. ↩

Ellis interview. ↩

Ellis interview ↩

See WatchMojo, Exposing Worst ContentID Abusers! #WTFU (May 2, 2019), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gbs9UVelEfg (last visited Sep 29, 2020). ↩

Brewis and Lo interview ↩

How Google Fights Piracy, 28 (2018). ↩

Amy Watson, Most Popular Video Streaming Services in the United States as of September 2019, by Monthly Average Users, Statista (Aug 24, 2020), https://www.statista.com/statistics/910875/us-most-popular-video-streaming-services-by-monthly-average-users/ (last visited Sep 29, 2020). ↩

US Media Consumption Report 2019, Attest (2019), available at https://www.askattest.com/original-research/us-media-consumption-report-2019 (last visited Sep 29, 2020). ↩

Robert Shapiro and Siddhartha Aneja, Taking Root: The Growth of America’s New Creative Economy, Re:Create (2019), 1, available at https://www.recreatecoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/ReCreate-2017-New-Creative-Economy-Study.pdf. ↩

Ben Parr, YouTube Is Huge: 24 Hours of Video Now Uploaded Every Minute, Mashable (March 17,2010), available at https://mashable.com/2010/03/17/youtube-24-hours (last visited Sep 29, 2020). ↩

J. Clement, YouTube: Hours of Video Uploaded Every Minute as of May 2019, Statista (Aug 25, 2020), https://www.statista.com/statistics/259477/hours-of-video-uploaded-to-youtube-every-minute (last visited Sep 29, 2020). ↩

Ben Parr, YouTube Surpasses Two Billion Video Views Daily, Mashable (May 16, 2010), available at https://mashable.com/2010/05/16/youtube-2-billion-views (last visited Sep 29, 2020). ↩

Grant Eizikowitz, How to Get a Billion Views on YouTube, Business Insider (April 30, 2018), available at

https://www.businessinsider.com/how-to-get-billion-views-viral-hit-youtube-2018-4 (last visited Sep 29, 2020). ↩

See Rachel Dunphy, Can YouTube Survive the Adpocalypse?, Intelligencer (December 28, 2017),

https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2017/12/can-youtube-survive-the-adpocalypse.html (last visited Sep 29, 2020). ↩

Back to top

Follow EFF:

Check out our 4-star rating on Charity Navigator .

- Internships

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Creativity & Innovation

- EFFector Newsletter

- Press Contact

- Join or Renew Membership Online

- One-Time Donation Online

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- About Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, limitations.

- < Previous

How does the public perceive music copyright law? A content analysis of YouTube videos on the Flame v Perry ‘Dark Horse’ case

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Ann C Luk, How does the public perceive music copyright law? A content analysis of YouTube videos on the Flame v Perry ‘Dark Horse’ case, Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice , Volume 17, Issue 9, September 2022, Pages 704–726, https://doi.org/10.1093/jiplp/jpac066

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Ann Luk is a lecturer in Law at the University of Kent, Darwin Road, Canterbury, UK. She specializes in interdisciplinary study, specifically between law and psychology.

This study undertakes a qualitative content analysis of YouTube videos on the Flame v Perry ‘Dark Horse’ case in order to analyse public discussion regarding music copyright law ( n = 59).

Results show that YouTube creators are engaged with complex issues in copyright law. It is found that disagreement exists over how to apply the ‘substantial similarity’ test and that there is a widespread concern that copyright law is becoming excessive in its protection of common musical elements, which should be available to all, are. Results indicate that those from a music background are particularly concerned with these issues and that this is reflected in their more likely decision of no copyright infringement in this case. Concerns with the ability of the law to provide unbiased and neutral decisions were expressed by many.

Overall, the results indicate that copyright law is in a challenging position and that there is a need to rebuild trust in the ability of the law to distinguish genuine copyright claims from frivolous charges.

Copyright law has increasingly been in the public eye due to several high-profile music cases. These have notably included the charges made against Pharrell Williams and Robin Thicke’s ‘Blurred Lines’ by the estate of the late Marvin Gaye, 1 which has since led to a plethora of large-scale cases, including Jessie Braham suing Taylor Swift for her lyrics in ‘Shake it Off’, 2 Marcus Gray suing Katy Perry for copyright infringement in ‘Dark Horse’, 3 and more recently the copyright case against Ed Sheeran’s ‘Shape of You’. 4

The ‘Blurred Lines’ case received high levels of attention due to not only the prominent status of the musicians involved but also the general criticism of the case. 5 A jury unanimously held that ‘Blurred Lines’ did infringe upon Marvin Gaye’s ‘Got to Give it Up’, with the final damages award held at $5.3million. Thicke had acknowledged in prior interviews that he did take inspiration from Gaye’s song, specifically stating that he wanted to make something similar to its groove. 6 The dissenting judgment from Justice Nguyen reflects many of the main concerns that the final judgment unfairly punishes ‘inspiration’ as ‘copying’ and allows the ‘Gayes to accomplish what no one has before: copyright a musical style’. 7 The case has been described as ‘frivolous’ 8 and setting a dangerous precedent, which creates a hindrance rather than a protection for artists. 9 Some have challenged whether too much in damages were rewarded, 10 with others arguing that the current test in copyright law of ‘substantial similarity’ is too subjective and confusing. 11

As it has been noted, the foundational nature of copyright has been constantly disputed. 12 It faces numerous issues including widespread non-compliance and multiple ongoing debates regarding what its justifications are. 13 While the basic purpose of copyright law to protect and encourage creativity is generally undisputed, there are important questions regarding how the law should do so and to what extent. 14 This has led to arguments that a justificatory pluralist toolbox is needed to take into account the diverse stakeholders and competing interests involved. 15 With regard to music in particular, the modern context of how society uses and engages with music challenges the adaptability of our current legal provisions. Particular instances referred to include the use of music in political campaigns 16 and the increasing complexity of music production today, complicating the question of ownership. 17

This article focuses on the particular question of how the public perceives the current state of copyright law particularly in the music context. This is an important question that will shed light on how the public engages with these debates, highlighting what they perceive to be some of the main issues and challenges.

A recent study shows that the public is capable of engaging in deliberative discourse regarding complex issues in copyright law. 18 Another study demonstrates how YouTube can be used as an effective research tool to gauge public reaction to copyright infringement strikes. 19

This article will similarly utilize a content analysis method to analyse public perceptions over the ‘Dark Horse’ copyright case. This case is chosen for its relevance to the current debates regarding copyright protections over music and also because of its interesting legal procedure, which involved the overturning of a jury’s verdict.

The ‘Dark Horse’ case was brought in 2014 by Christian rapper, Marcus Gray, from now on referred to by his stage name of Flame, who argued that Katy Perry’s ‘Dark Horse’ copied an eight-note ostinato from his song ‘Joyful Noise’. A jury found that there was copyright infringement, awarding $2.8 million in damages. This was overturned by Judge Snyder in a US District Court, who distinguished this case from ‘Blurred Lines’, stating that the elements did not comprise the entire musical composition of the song and were made up of common building blocks (CBB) of music, which cannot be protected. 20 Under US copyright law, a two-part test for substantiality is used. First, the extrinsic test is applied by the court to decide if there is a ‘similarity of ideas and expression as measured by external, objective criteria.’ If the extrinsic test is passed, the case is then passed to the jury who must consider the intrinsic test. This asks ‘whether the ordinary, reasonable person would find the total concept and feel of the works to be substantially similar’. 21 Judge Snyder argued that the previous court had incorrectly found evidence of the extrinsic test, and for this reason, it should not have reached the jury in the first place. This decision was upheld following an appeal in the Ninth Circuit.

The data for this study consist of a manual search on YouTube videos that was carried out between 29 March and 31 March 2022. The keyword search terms were ‘dark horse copyright’, ‘katy perry copyright’ and ‘katy perry flame –immortal’. The ‘–’ operator was used in the last search term to force the results to omit reference to an unrelated Katy Perry song entitled Immortal Flame. The search included all videos that have been uploaded since Dark Horse was released on 17 September 2013.

The search terms were purposefully kept broad to ensure maximum coverage. However, this led to irrelevant videos such as those covering the Dark Horse song without mentioning any copyright issues, which were therefore excluded from the analysis. Also excluded were YouTube shorts, videos that duplicated content with previously uploaded videos and videos that were not in English.

This resulted in a total of 118 videos. A preliminary check identified that 59 consisted entirely of factual information regarding the case. This left 59 videos in total for the final analysis. Tables 1–3 provide overviews of these datasets. The videos collected encompass a range of accounts, from those with subscribers of below 1000 to over 1 million ( Table 1 ). There is evidence of high levels of engagement with the uploaded videos, with over 12 million views in total, over 500 000 likes and over 50 000 comments ( Table 2 ). Based on an analysis of the videos uploaded by the YouTube channel, the background of the YouTube creator was identified. The channels cover several creator backgrounds including from music, law, general (no overriding topic of interest identified from the uploaded videos), Christian religion and sports ( Table 3 ).

Overview of videos, showing the distribution by date, search term and subscribers to the channel. F = videos containing factual information only. R = videos containing material relevant for further content analysis

Overview of videos by length, number of views, number of likes and number of comments. F = videos containing only factual information. R = videos relevant for further content analysis

Overview of the number of videos included in the data analysis, broken down by YouTube creator’s background, which is identified by the topic of videos uploaded by the channel

A pilot study was carried out on eight randomly selected videos ( n = 8) to identify core themes and issues. Two researchers independently analysed these videos before comparing them. This ultimately resulted in the development of a codebook, which included one closed-ended section for manual analysis; did the creator think a copyright infringement had occurred or not? (positive, negative or not stated), and qualitative categories for further thematic analysis. The qualitative categories were developed using a grounded approach 22 and consisted of four central themes. First, ‘relevant factors’ includes discussion regarding how to decide if a copyright infringement has occurred and what factors should be taken into account. Second, ‘consequences’ refers to comments made regarding the legal consequences of the case, such as conversations around damages, as well as any other broader implications from the case on the parties or on the general public. Third, ‘challenges’ refers to the discussion revolving around issues that can negatively impact the legal proceedings for copyright cases, for instance potential biases the jury might have. Lastly, ‘emotional responses’ referred to explicit statements made regarding creators’ emotional response to the case or emotive language used indicative of an emotional response to the case.

An overview of results in each of these categories will be broken down into key legal event to test for any differences in public perceptions across the timeline of the case. These key legal events are defined as follows: firstly, before the first case was heard on 29 July 2019; secondly, after the jury verdict and before the reversing of the jury verdict on 16 March 2020; thirdly, after the reversing of the jury verdict and before the Ninth Circuit decision on 10 March 2022; lastly, after the Ninth Circuit decision. Results will also be analysed according to background of the creator and correspondence to the creator’s decision of whether copyright infringement has occurred.

This study focuses on one particular case and one particular social medial platform. Future studies can build on these findings by applying similar methods to test how public opinion differs across social media platforms, including non-English speakers, or between users of social media platforms versus non-users and in relation to different copyright cases. This study is also a snapshot of current public opinion and so does not capture any longitudinal changes, meaning that it cannot contribute to questions of what affects public perceptions to music copyright law. As this is an analysis based on YouTube videos, the background of the speakers could be identified based on the types of videos uploaded by the channel, but more discrete information such as age or nationality was not available. Nevertheless, the sample was able to include speakers from a variety of backgrounds including music, law and a strong proportion from more general backgrounds.

I. Was there copyright infringement?

Of the 59 YouTube creators, 44 provided an opinion on if there was a copyright infringement. Opinions were finely balanced with an almost equal proportion at each stage ( Fig. 1 ). Breaking this down by background of the creator, the majority of music creators decided that there is no copyright infringement. There was an almost equal balance for general creators. The majority of legal and Christian religion creators decided either that there was copyright infringement or did not provide any opinion on this ( Fig. 2 ).

Opinions on whether a copyright infringement has occurred. Results are broken down by key legal event.

Opinions on whether a copyright infringement occurred broken down by background of YouTube creator.

II. Relevant factors

During the pilot study, a grounded theory approach was used to identify a core issue that was discussed by the majority of YouTube creators ( n = 41, 69.49 per cent, Fig. 3 ). This was the question of what the relevant factors for a decision of copyright infringement are.

Number of creators discussing factors relevant for copyright infringement. Results are broken down by key legal event.

Following the notes made from the content analysis, comments regarding relevant factors were delineated into six main groups: feel and atmosphere, musical elements, access, proportion and substantiality, CBB of music, history and intention of parties. These groups are not mutually exclusive, and as discussed below, the category of musical elements is further divided.