- I Want to Learn Project Management

- Core Project Management Courses

- I Want to Study Agile Project Management

- Agile Project Management Courses

- Project Management Software

- I Need my Team to be Better at Project Management & Delivery

- I Want to Study for Project Management Professional (PMP)

- The Project Manager’s PMP Study Guide

- PMI Qualifications and PDUs

- I Want to Study for PRINCE2

- PRINCE2 Qualifications

- Agile Qualifications (Scrum and more)

- ITIL Qualifications

- Project Management Knowledge Areas

- Leadership and Management Skills

- Professional Personal Effectiveness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Our Latest Project Management Articles

- Themed Directory of PM Articles

- All Our PM Articles: List

- Our Top ‘Must-Read’ Project Management Guides

- Project Management Podcasts

- All our Project Management Tools & Resources

- Free Online Project Management Resources

- Project Management Productivity Bundle

- Project Management Template Kit

- Project Management Checklists

- Project Management Bookshop

- Project Management Domains

- OnlinePMCourses Kindle-exclusive Project Management eBooks Series

- What is Your Project Management Personality?

- Project in a Box

- The OnlinePMCourses Newsletter

- About OnlinePMCourses

- Contact OnlinePMCourses

- Frequently Asked Questions

- How it Works

- Volume Licensing of Project Management Courses for Businesses

- Become an OnlinePMCourses Affiliate

- Writing for OnlinePMCourses

- How to Build OnlinePMCourses

- OnlinePMCourses Email Whitelisting Instructions

- OnlinePMCourses Privacy Policy

- Free Academy of PM

3 December, 2018

2 comments

Problem-Solving: A Systematic Approach

By Mike Clayton

One of the joys of Project Management is the constant need for problem-solving.

The novelty and uncertainty of a project environment constantly throw up surprises. So, a Project Manager needs to be adept at solving problems.

In this article, we look at problem-solving and offer you a structured, systematic approach.

Problem-Solving Methodologies

There are a lot of established approaches to structured problem-solving. And there is a good chance that, if you work in a large organization, one of them is in common use. Indeed, some organizations mandate a particular problem-solving methodology.

For example, in automobile manufacturing industries, the 8 Disciplines or 8-D methodology is used widely. And anywhere that Six Sigma is an important part of the toolset, you will probably find the DMAIC method of problem-solving.

Others I like include Simplex and the catchily-named TOSIDPAR. And there are still others that, whilst highly effective, are also assertively protected by copyright, making them hard to discuss in an article like this. I’m thinking of you, Synectics.

Strengths and Weaknesses

All of these methodologies offer great features. And curiously, while each one feels complete, none offers every step you might want. The reason is simple. Each approach is tailored to focus on a part of the problem-solving process. Other parts are either outside their remit or receive less emphasis.

Comparison of Approaches

The consequence is that every structured approach can miss out steps that are important in some contexts. To illustrate, let’s compare the four methodologies I have mentioned.

Resolving the Gaps

At OnlinePMCourses, we use an 8-step problem-solving approach that covers just about all of the steps that these four methodologies offer. But, before we address these, let’s take a look at some practical approaches to applying problem-solving.

Practical Implementation

Some of the best examples of project problem-solving are in two of my favorite movies:

- Apollo 13 ‘Let’s work the problem’ (Gene Kranz played by Ed Harris)

- The Martian ‘In the face of overwhelming odds, I’m left with only one option, I’m gonna have to science the shit out of this.’ (Mark Watney played by Matt Damon)

In the Apollo 13 movie, there’s a scene where one engineer dumps a big pile of stuff onto a table in front of a bunch of his colleagues.

‘The people upstairs handed us this one and we’ve gotta come through. We’ve gotta’ find a way for this {holds up square thing] fit into the hole for this [a round thing] using nothing but that [a pile of random-looking stuff]. Let’s get it organized.’

They all dive in and we hear a hubbub.

Hubbub is about as reasonable a translation of the Japanese onomatopoeic word Waigaya as I can find. The idea behind Honda’s Waigaya approach is that everyone on the team gets to contribute to the conversation. But it isn’t a simple free-for-all. There are rules:

- Everybody is equal and needs to be able to say what they think.

- The team must listen to all ideas, and discuss them until they can either prove them to be valid or reject them.

- Once someone shares an idea, they don’t own it – it belongs to the team, who can do with the idea what it wants.

- At the end of waigaya, the team has a set of decisions and responsibilities for what to do, by whom, and by when.

There is a fabulous article that is well worth reading, at the Strategy & Business site .

In The Martian, the character Mark Watney is stuck with his problem. This makes it immediate, and also easy to see the context clearly. Another idea from Japanese manufacturing harnesses the value of getting out from behind your desk and going to where the problem is. It’s called ‘ going to the gemba’ – literally, ‘going to the place’ .

There is magic, when we get up, move about, and gather where the problem is happening. Going to the gemba and convening a waigaya is a great way to kick-off even the most complex problem-solving. Unless, that is, the gemba is halfway to the moon, or on Mars.

Recommended 8-Step Problem Solving Method

To reconcile the different methodologies for solving problems on projects, I have developed my own approach. It was tempting just to take the 17 steps in the chart above. But I also found that those four still miss some steps I find important to remember.

Would anyone think a 20-step Problem-solving Process Makes Sense?

I doubt it.

So, I decided to wrap some of the steps into 8 main steps. This gives us an 8-step method, which has everything that I have found you will need for problem-solving in a project context.

In the figure below, you can see those 8 steps as the bold boxes, with the subsidiary elements that form parts of those 8 major steps in fainter type.

So, in the rest of this article, I’ll summarize what I mean by each of these steps.

1. Define the Problem

Defining your problem is vital and takes up four of the 9 steps in the 8 Disciplines approach. But, on a project, this is often clearer than a new problem arising out of the blue in a manufacturing context, where 8D is most popular. So, I have folded the four parts into one step.

Understand the Context

Here’s where you need to find out how the problem impacts the whole of your project, and the circumstances in which it has arisen.

Gather Your Team

On a small project, this is likely to be all or most of your project team. For larger projects, this will center around the team delivering the workstream that the problem affects. For systemic problems, you’ll be asking work-stream leaders to supply expert team members to create a cross-cutting team. We sometimes call these ‘Tiger Teams’ – for reasons I can’t tell you, I’m afraid!

To support you in this stage, you may want to take a look at these articles:

- What You Need to Know about Building a Great Project Team

- Effective Teamwork: Do You Know How to Create it?

- Boost Your Project Team Performance with these Hacks

- How I Create Exceptional Project Collaboration

- How to Make Your Next Kick-off Meeting a Huge Success

Define the Problem

It’s often reasonably easy to define your problem in terms of ‘what’s wrong’. But it pays to be a specific as possible. And one thing that will help you with the next main step (setting an objective) is to define it in terms of what you want.

I like the discipline of defining your problem as:

How to…

Safety First

When I first encountered the 8 Disciplines method, the step that blew me away was D3 – Contain the Problem. I’d not thought of that before!

But it’s clear that, in many environments, like manufacturing, engineering, and transportation, solving the problem is not your first priority. You must first ensure that you do everything possible to limit further damage and risk to life and reputation. This may be the case on your project.

2. Set An Objective for Resolving the Problem

With everything safe and the problem not getting worse, you can move forward. This step is about defining what success looks like.

And, taking a leaf out of the TOSIDPAR approach, what standards, criteria, and measurable outcomes will you use to make your objective s precise as possible?

3. Establish the Facts of the Problem

I suppose the first step in solving a problem is getting an understanding of the issues, and gathering facts. This is the research and analysis stage.

And I like the DMAIC method’s approach of separating this into two distinct parts:

- Fact-finding. This is where we make measurements in DMAIC, and gather information more generally. Be careful with perceptions and subjective accounts. It may be a fact that this is what I think I saw, but it may not be what actually happened.

- Analysis Once you have your evidence, you can start to figure out what it tells you. This can be a straightforward discussion, or may rely on sophisticated analytical methods, depending on circumstances. One analytical approach, which the 8D method favors, is root cause analysis. There are a number of ways to carry this out.

4. Find Options for Resolving the Problem

I see this step as the heart of problem-solving. So, it always surprises me how thin some methodologies are, here. I split it into four considerations.

Identify Your Options

The creative part of the problem-solving process is coming up with options that will either solve the problem or address it in part. The general rules are simple:

Rule 1: The more options you have, the greater chance of success. Rule 2: The more diverse your team, the more and better will be the options they find.

So, create an informal environment, brief your team, and use your favorite idea generation methods to create the longest list of ideas you can find. Then, look for some more!

Identify your Decision Criteria

A good decision requires good input – in this case, good ideas to choose from. It also needs a strong process and the right people. The first step in creating a strong process is to refer back to your objectives for resolving the problem and define the criteria against which you will evaluate your options and make your decision.

Determine your Decision-makers

You also need to determine who is well-placed to make the decision. This will be by virtue of their authority to commit the project and their expertise in assessing the relevant considerations. In most cases, this will be you – maybe with the support of one or more work-stream leaders. For substantial issues that have major financial, schedule, reputational, or strategic implications, this may be your Project Sponsor or Project Board.

Evaluate your Options

There are a number of ways to evaluate your problem resolution options that range from highly structured and objective to simple subjective approaches. Whichever you select, be sure that you apply the criteria you chose earlier, and present the outcomes of your evaluation honestly.

It is good practice to offer a measure of the confidence decision-makers can have in the evaluation, and a scenario assessment, based on each option.

5. Make a Decision on How to Resolve the Problem

We have done two major articles like this one about decision-making. For more on this topic, take a look at:

- The Essential Guide to Robust Project Decision-Making

- Rapid Decision Making in Projects: How to Get it Right

There are two parts to this step, that are equally important.

- The first is to make the decision.

- The second is to document that decision

Documenting your Decision

Good governance demands that you document your decision. But how documentation to provide is a matter of judgment. Doubtless, it will correlate to the scale and implications of that decision.

Things to consider include:

- What were the options?

- Who were the decision-makers?

- What was the evidence they considered?

- How did they make their decision (process)?

- What decision did they make?

- What were the reasons for their choice?

6. Make a Plan for Resolving the Problem

Well, of course, now you need to put together a plan for how you are going to implement your resolution. Unless, of course, the fix is simple enough that you can just ask your team to get on and do it. So, in that case, skip to step 7.

Inform your Stakeholders

But for an extensive change to your project, you will need to plan the fix. And you will also need to communicate the decision and your plan to your stakeholders. Probably, this is nothing more than informing them of what has happened and how you are acting to resolve it. This can be enormously reassuring and the cost of not doing so is often rumours and gossip about how things are going wrong and that you don’t have control of your project.

Sometimes, however, your fix is a big deal. It may involve substantial disruption, delay, or risk, for example. In this case, you may need to persuade some of your stakeholders that it is the right course of action. As always, communication is 80 percent of project management, and stakeholder engagement is critical to the success of your project.

7. Take Action

There’s an old saying: ‘There’s no change without action.’ Indeed.

What more can I say about this step that will give you any value?

Hmmm. Nothing.

8. Review and Evaluate Your Plan

But this step is vital. How you finish something says a lot about your character.

If you consider the problem-solving as a mini-project, this is the close stage. And what you need to do will echo the needs of that stage. I’ll focus on three components.

Review and Evaluate

Clearly, there is always an opportunity to learn from reviewing the problem, the problem-solving, and the implementation, after completion. This is important for your professional development and for that of your team colleagues.

But it is also crucial to keep the effectiveness of your fix under review. So, monitor closely, until you are confident you have completed the next task…

Prevent the Problem from Recurring

Another phrase from the world of Japanese manufacturing: ‘Poka Yoke’ .

This is mistake-proofing. It is about designing something so it can’t fail. What stops you from putting an SD card or a USB stick into your device in the wrong orientation? If you did, the wrong connections of pins would probably either fry the memory device or, worse, damage your device.

The answer is that they are physically designed so they cannot be inserted incorrectly.

What can you do on your project to make a recurrence of this problem impossible? If there is an answer and that answer is cost-effective, then implement it.

Celebrate your Success in Fixing it

Always the last thing you do is celebrate. Now, when Jim Lovell, Jack Swigert, and Fred Haise (the crew of Apollo 13) returned safely to Earth, I’ll bet there was a big celebration. For solving your project problem, something modest is more likely to be in order. But don’t skill this. Even if it’s nothing more than a high five and a coffee break, always ensure that your team knows they have done well.

What Approach Do You Use for Problem-Solving?

How do you tackle solving problems on your projects? Do tell us, or share any thoughts you have, in the comments below. I’ll respond to anything you contribute.

Never miss an article or video!

Get notified of every new article or video we publish, when we publish it.

Type your email…

Mike Clayton

About the author....

Great structure, Mike. We had a problem once that suited the “contain” step quite well. Lubricating oil and hydraulic fluid, from the same supplier, had been packaged incorrectly. A tech went to add oil to an aircraft’s engine, but dropped the can onto the concrete, and noticed red hydraulic fluid spill out! Obviously there’s now the risk that people have been inadvertently adding hydraulic fluid to aircraft engines… not good. It was actually FAR more important to contain this is real time so that aircraft, some of which could be airborne, could be safely grounded/quarantined. Resolving the subsequent ramifications could then be accomplished in “slow time” with some deliberate planning/execution.

Thank you very much. That’s a powerful illustration and hopefully the incudenbt did not cause any loss of life or serious damage.

Get notified of every new article or video we publish, when we publish it.

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.

CSense Management Solutions Pvt Ltd

Search search, systematic problem-solving.

What is Problem-solving?

Before we understand problem-solving, let us first calibrate ourselves on ‘what is called a problem?’

When there is a gap between our expectations and reality, we feel unhappy – which is a Problem . This is how a deviation from the specification, a failure to meet timelines, etc., become our problems. A problem could be defined as “the gap between our expectations and actual state or observation”.

From the gap analogy, we also understand that as the gap increases, our suffering intensifies.

Problem-solving

A fundamental part of every manager’s role is problem-solving. So, being a confident problem solver is really important to your success.

Much of that confidence comes from having a good process to use when approaching a problem. With one, you can solve problems quickly and effectively. Without one, your solutions may be ineffective, or you’ll get stuck and do nothing, sometimes with painful consequences.

Managing the problem (correction) instead of solving it (with corrective action) creates firefighting in our daily work. To solve a problem permanently, we need to understand and act on its root cause. We will also follow the steps of identifying root causes and prevent their recurrence in this workshop.

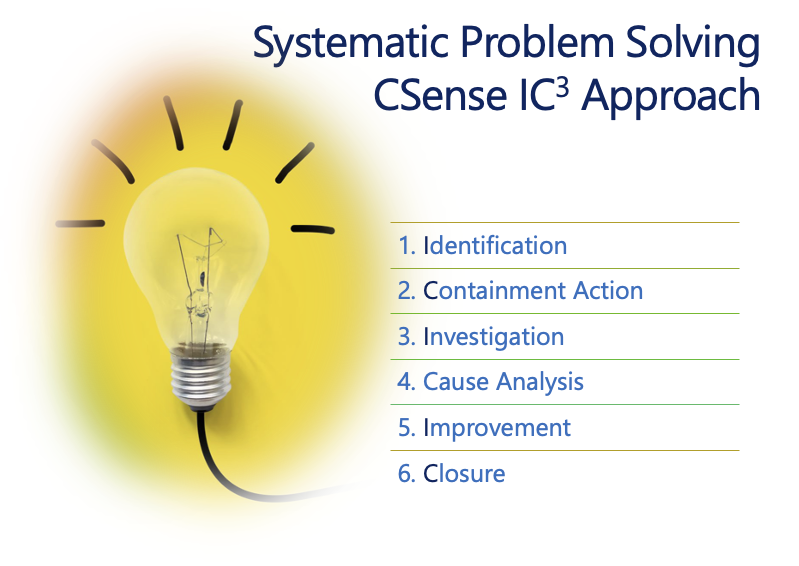

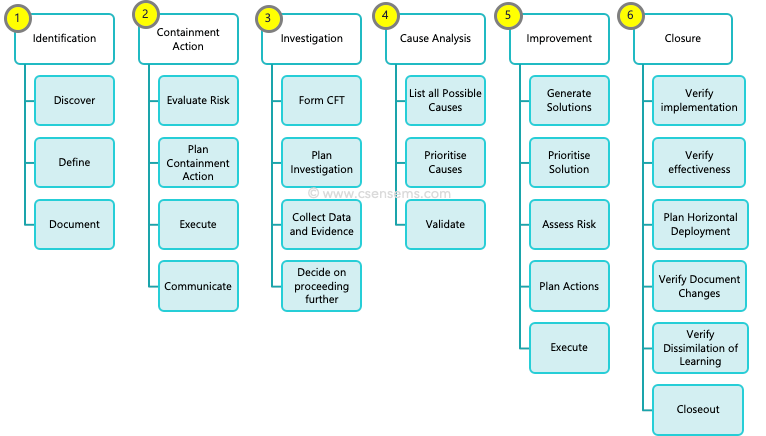

CSense IC 3 Approach

- Identification

- Containment Action

- Investigation

- Cause Analysis

- Improvement

Applications of methodology

The methodology is simple and applicable to most of the problems faced by the industries. Hence, it is widely accepted and recommended by companies. This also forms a framework for Auto industries’ 8D Problem Solving, Pharma industries’ USFDA recommended 7 step approach and Six Sigma’s DMAIC approach.

Training Contents

- Overview of Problem-solving

- Need for Problem-Solving

- Managing a Problem Vs Problem Solving

- Definitions – Correction, Corrective Action & Preventive Action

Step by Step Approach to Problem-Solving

1. identification.

- Use of 5W2H questions

2. Containment Action

- Assessing the problem and its risk

- Forming Effective Teams

- CFT & CHT

- Damage control – Interim Actions

- Communication plan

3. Investigation

- Data / Evidence Collection

4. Cause Analysis

- Brainstorming for Problem-solving

- Fishbone Analysis

- Is – Is Not Analysis

- Process Mapping

- Data and Statistical Analysis

- Data collection

- Graphical Tools

- Why-Why Analysis

- Validation of Root causes

- Statistical Analysis

5. Improvement

- Permanent Corrective Action

- Solution Generation

- Pilot Implementation

- Solution Action Plan

- Preventing Recurrence

- Control Plan

- Verification of Status

- Verification of Effectiveness

- Training & Documentation

Training Duration

- Two days – 16 hours

About the Course

The Problem-Solving workshop caters to leaders and managers who are interested in solving the recurring problems and want to bring in the culture and team-based approach of systematic problem solving to every level of people in the organisation. We deal with the most relevant tools in the step-by-step approach. We can take up the actual cases of recurring problems in the company as an example and study for the workshop. The course covers essential problem-solving tools like problem definition, containment action, root cause analysis with QC tools, root cause validation using statistical tools, corrective action, preventive action, escape points, Poka-yoke and more.

Course Objectives

At the end of the course, participants will be able to understand and appreciate

- Cost of Poor Quality

- The need for Systematic problem-solving

- Various approaches to problem-solving

- Difference between correction, corrective action and preventive action

- Team approach enhance effective solutions and learning

- Risk assessment and containment actions

- Root cause analysis

- Statistical tools

- Arriving at an effective action plan

- Preventing the defects

Target Audience

- Managers responsible for process improvements

- Quality Managers, Internal and External Auditors

- Shop floor managers and supervisors

- Production and Maintenance Managers

- Product Design Engineers

- Research Engineers & Scientists

Workshop Methodology

CSense Workshop approach is based on scientifically proven methodologies of Learning, which includes Learning by

- Listening – Classroom sessions & Audio-Visuals

- by Teaching

- Examples & Exercises at the end of each step

- We will provide the required Templates and formats for each tool

- During the course, we will form 3 to 4 cross-functional teams

- We will help each team choose a specific problem (either an open Non-conformance or a recently closed out non-conformance)

- We encourage the teams to choose different types of problems like Audit observations, internal failures/rejections, customer complaints, machine breakdown or accidents.

- Then we will guide the participants to work on their assigned problem with the new approach – application & documentation.

- Faculty will help the teams to apply the learning on the problems and explain the practical doubts.

- After each step, teams will present their work.

Min 12 and Max 20 Participants per batch

Customisation

We can customise the deliverable as per client’s requirements.

Certification

- Certification Criteria: 90% attendance in Training Sessions, participation in activities and 70% Score in written test

- The test will be conducted on 2 nd day of training

- Laptop/desktop with provision to install software packages for participants to be arranged by the client.

Additional Support

Continued coaching and hand-holding support could be provided by CSense after the workshop for successful project completion, as an optional engagement.

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Self-Assessment • 20 min read

How Good Is Your Problem Solving?

Use a systematic approach..

By the Mind Tools Content Team

Good problem solving skills are fundamentally important if you're going to be successful in your career.

But problems are something that we don't particularly like.

They're time-consuming.

They muscle their way into already packed schedules.

They force us to think about an uncertain future.

And they never seem to go away!

That's why, when faced with problems, most of us try to eliminate them as quickly as possible. But have you ever chosen the easiest or most obvious solution – and then realized that you have entirely missed a much better solution? Or have you found yourself fixing just the symptoms of a problem, only for the situation to get much worse?

To be an effective problem-solver, you need to be systematic and logical in your approach. This quiz helps you assess your current approach to problem solving. By improving this, you'll make better overall decisions. And as you increase your confidence with solving problems, you'll be less likely to rush to the first solution – which may not necessarily be the best one.

Once you've completed the quiz, we'll direct you to tools and resources that can help you make the most of your problem-solving skills.

How Good Are You at Solving Problems?

Instructions.

For each statement, click the button in the column that best describes you. Please answer questions as you actually are (rather than how you think you should be), and don't worry if some questions seem to score in the 'wrong direction'. When you are finished, please click the 'Calculate My Total' button at the bottom of the test.

Answering these questions should have helped you recognize the key steps associated with effective problem solving.

This quiz is based on Dr Min Basadur's Simplexity Thinking problem-solving model. This eight-step process follows the circular pattern shown below, within which current problems are solved and new problems are identified on an ongoing basis. This assessment has not been validated and is intended for illustrative purposes only.

Below, we outline the tools and strategies you can use for each stage of the problem-solving process. Enjoy exploring these stages!

Step 1: Find the Problem (Questions 7, 12)

Some problems are very obvious, however others are not so easily identified. As part of an effective problem-solving process, you need to look actively for problems – even when things seem to be running fine. Proactive problem solving helps you avoid emergencies and allows you to be calm and in control when issues arise.

These techniques can help you do this:

PEST Analysis helps you pick up changes to your environment that you should be paying attention to. Make sure too that you're watching changes in customer needs and market dynamics, and that you're monitoring trends that are relevant to your industry.

Risk Analysis helps you identify significant business risks.

Failure Modes and Effects Analysis helps you identify possible points of failure in your business process, so that you can fix these before problems arise.

After Action Reviews help you scan recent performance to identify things that can be done better in the future.

Where you have several problems to solve, our articles on Prioritization and Pareto Analysis help you think about which ones you should focus on first.

Step 2: Find the Facts (Questions 10, 14)

After identifying a potential problem, you need information. What factors contribute to the problem? Who is involved with it? What solutions have been tried before? What do others think about the problem?

If you move forward to find a solution too quickly, you risk relying on imperfect information that's based on assumptions and limited perspectives, so make sure that you research the problem thoroughly.

Step 3: Define the Problem (Questions 3, 9)

Now that you understand the problem, define it clearly and completely. Writing a clear problem definition forces you to establish specific boundaries for the problem. This keeps the scope from growing too large, and it helps you stay focused on the main issues.

A great tool to use at this stage is CATWOE . With this process, you analyze potential problems by looking at them from six perspectives, those of its Customers; Actors (people within the organization); the Transformation, or business process; the World-view, or top-down view of what's going on; the Owner; and the wider organizational Environment. By looking at a situation from these perspectives, you can open your mind and come to a much sharper and more comprehensive definition of the problem.

Cause and Effect Analysis is another good tool to use here, as it helps you think about the many different factors that can contribute to a problem. This helps you separate the symptoms of a problem from its fundamental causes.

Step 4: Find Ideas (Questions 4, 13)

With a clear problem definition, start generating ideas for a solution. The key here is to be flexible in the way you approach a problem. You want to be able to see it from as many perspectives as possible. Looking for patterns or common elements in different parts of the problem can sometimes help. You can also use metaphors and analogies to help analyze the problem, discover similarities to other issues, and think of solutions based on those similarities.

Traditional brainstorming and reverse brainstorming are very useful here. By taking the time to generate a range of creative solutions to the problem, you'll significantly increase the likelihood that you'll find the best possible solution, not just a semi-adequate one. Where appropriate, involve people with different viewpoints to expand the volume of ideas generated.

Tip: Don't evaluate your ideas until step 5. If you do, this will limit your creativity at too early a stage.

Step 5: Select and Evaluate (Questions 6, 15)

After finding ideas, you'll have many options that must be evaluated. It's tempting at this stage to charge in and start discarding ideas immediately. However, if you do this without first determining the criteria for a good solution, you risk rejecting an alternative that has real potential.

Decide what elements are needed for a realistic and practical solution, and think about the criteria you'll use to choose between potential solutions.

Paired Comparison Analysis , Decision Matrix Analysis and Risk Analysis are useful techniques here, as are many of the specialist resources available within our Decision-Making section . Enjoy exploring these!

Step 6: Plan (Questions 1, 16)

You might think that choosing a solution is the end of a problem-solving process. In fact, it's simply the start of the next phase in problem solving: implementation. This involves lots of planning and preparation. If you haven't already developed a full Risk Analysis in the evaluation phase, do so now. It's important to know what to be prepared for as you begin to roll out your proposed solution.

The type of planning that you need to do depends on the size of the implementation project that you need to set up. For small projects, all you'll often need are Action Plans that outline who will do what, when, and how. Larger projects need more sophisticated approaches – you'll find out more about these in the article What is Project Management? And for projects that affect many other people, you'll need to think about Change Management as well.

Here, it can be useful to conduct an Impact Analysis to help you identify potential resistance as well as alert you to problems you may not have anticipated. Force Field Analysis will also help you uncover the various pressures for and against your proposed solution. Once you've done the detailed planning, it can also be useful at this stage to make a final Go/No-Go Decision , making sure that it's actually worth going ahead with the selected option.

Step 7: Sell the Idea (Questions 5, 8)

As part of the planning process, you must convince other stakeholders that your solution is the best one. You'll likely meet with resistance, so before you try to “sell” your idea, make sure you've considered all the consequences.

As you begin communicating your plan, listen to what people say, and make changes as necessary. The better the overall solution meets everyone's needs, the greater its positive impact will be! For more tips on selling your idea, read our article on Creating a Value Proposition and use our Sell Your Idea Skillbook.

Step 8: Act (Questions 2, 11)

Finally, once you've convinced your key stakeholders that your proposed solution is worth running with, you can move on to the implementation stage. This is the exciting and rewarding part of problem solving, which makes the whole process seem worthwhile.

This action stage is an end, but it's also a beginning: once you've completed your implementation, it's time to move into the next cycle of problem solving by returning to the scanning stage. By doing this, you'll continue improving your organization as you move into the future.

Problem solving is an exceptionally important workplace skill.

Being a competent and confident problem solver will create many opportunities for you. By using a well-developed model like Simplexity Thinking for solving problems, you can approach the process systematically, and be comfortable that the decisions you make are solid.

Given the unpredictable nature of problems, it's very reassuring to know that, by following a structured plan, you've done everything you can to resolve the problem to the best of your ability.

This assessment has not been validated and is intended for illustrative purposes only. It is just one of many Mind Tool quizzes that can help you to evaluate your abilities in a wide range of important career skills.

If you want to reproduce this quiz, you can purchase downloadable copies in our Store .

You've accessed 1 of your 2 free resources.

Get unlimited access

Discover more content

4 logical fallacies.

Avoid Common Types of Faulty Reasoning

Problem Solving

Add comment

Comments (2)

Afkar Hashmi

😇 This tool is very useful for me.

over 1 year

Very impactful

Get 20% off your first year of Mind Tools

Our on-demand e-learning resources let you learn at your own pace, fitting seamlessly into your busy workday. Join today and save with our limited time offer!

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Most Popular

Newest Releases

Team Management Skills

5 Phrases That Kill Collaboration

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

How do i manage a hybrid team.

Adjusting your management style to a hybrid world

The Life Career Rainbow

Finding a Work-Life Balance That Suits You

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Get out of your own way at work: and help others to do the same.

Mark Goulston

Book Insights

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Decision Making

Pain Points

Creativity and Innovation pp 117–147 Cite as

Creative Problem-Solving

- Terence Lee 4 ,

- Lauren O’Mahony 5 &

- Pia Lebeck 6

- First Online: 29 January 2023

496 Accesses

This chapter presents Alex Osborn’s 1953 creative problem-solving (CPS) model as a three-procedure approach that can be deployed to problems that emerge in our everyday lives. The three procedures are fact-finding, idea-finding and solution-finding, with each step carefully informed by both divergent and convergent thinking. Using case studies to elaborate on the efficacy of CPS, the chapter also identifies a few common flaws that can impact on creativity and innovation. This chapter explores the challenges posed by ‘wicked problems’ that are particularly challenging in that they are ill-defined, unique, contradictory, multi-causal and recurring; it considers the practical importance of building team environments, of embracing diversity and difference, and other characteristics of effective teams. The chapter builds conceptually and practically on the earlier chapters, especially Chapter 4 , and provides case studies to help make sense of the key principles of creative problem-solving.

- Creative problem-solving

- Fact-finding

- Idea-finding

- Solution-finding

- Divergent thinking

- Convergent thinking

- Wicked problems

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

The creative problem-solving process explored in this chapter is not to be confused with the broader ‘creative process’ that is presented in Chapter 2 of this book. See Chapter 2 to understand what creative process entails.

A general online search of the Osborn-Parnes Creative Problem-Solving (CPS) process will generate many results. One of them is: https://projectbliss.net/osborn-parnes-creative-problem-solving-process/ . Osborn is largely credited as the creator of CPS, hence references are largely made to him (Osborn 1953 , 1957 ).

Founded in 2002, Fahrenheit 212 described itself as “a global innovation consultancy delivering sustainable, profitable growth for companies by pairing business acumen and consumer empathy.” It merged with Capgemini Consulting in 2016 and remains based in New York City, USA. ( https://www.capgemini.com/in-en/news/press-releases/capgemini-acquires-innovation-and-design-consultancy-fahrenheit-212-to-drive/ ).

More information on the NeoNurture incubator can be found in the Design That Matters website ( https://www.designthatmatters.org/ ) and in a TEDx presentation by Timothy Prestero ( https://www.ted.com/talks/timothy_prestero_design_for_people_not_awards ) (Prestero 2012 ).

For more information on the Embrace infant warmer, see Embrace Global: https://www.embraceglobal.org/ .

See also David Alger’s popular descriptions of the ‘Rules of Improv’ (Parts 1 and 2): https://www.pantheater.com/rules-of-improv.html ; and, ‘How to be a better improvisor’: https://www.pantheater.com/how-to-be-a-better-improvisor.html .

For more information about the Bay of Pigs, visit the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum at Columbia Point, Boston, Massachusetts, USA. Online information can be accessed here: https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/jfk-in-history/the-bay-of-pigs .

Bhat, R. 2021. Solving Wicked Problems Is What MBA Programs Need to Prepare the Students For? Business World Education . May 20. Available: http://bweducation.businessworld.in/article/Solving-Wicked-Problems-Is-What-MBA-Programs-Need-To-Prepare-The-Students-For-/20-05-2021-390302/. Accessed 30 August 2022.

Bratton, J., et al. 2010. Work and Organizational Behaviour , 2nd ed. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Book Google Scholar

Buzan, T. 1974. Use Your Head . London: BBC Active.

Google Scholar

Cohen, A.K., and J.R. Cromwell. 2021. How to Respond to the COVID-19 Pandemic with More Creativity and Innovation. Population Health Management 24 (2): 153–155.

Article Google Scholar

Cunningham, E., B. Smyth, and D. Greene. 2021. Collaboration in the Time of COVID: A Scientometric Analysis of Multidisciplinary SARSCoV-2 Research. Humanities & Social Sciences Communications. 8 (240): 1–8.

Cunningham, S. 2021. Sitting with Difficult Things: Meaningful Action in Contested Times. Griffith Review 71 (February): 124–133.

De Bono, E. 1985. Six Thinking Hats . Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Dutta, K. 2018. Solving Wicked Problems: Searching for the Critical Cognitive Trait. The International Journal of Management Education 16 (3): 493–503.

Elia, G., and A. Margherita. 2018. Can we Solve Wicked Problems? A Conceptual Framework and a Collective Intelligence System to Support Problem Analysis and Solution Design for Complex Social Issues. Technological Forecasting & Social Change 133: 279–286.

Engler, J.O., D.J. Abson, and H. von Wehrden. 2021. The Coronavirus Pandemic as an Analogy for Future Sustainability. Sustainability Science 16: 317–319.

Grivas, C., and G. Puccio. 2012. The Innovative Team: Unleashing Creative Potential for Breakthrough Results . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Holmes, K. 2021. Generation Covid: Crafting History and Collective Memory. Griffith Review 71 (February): 79–88.

Kapoor, H., and J.C. Kaufman. 2020. Meaning-Making Through Creativity During COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology 18 (December): 1–8.

Kelley, T. 2001. The Art of Innovation: Lessons in Creativity from IDEO, America’s Leading Design Firm . New York, NY: Random House.

Kite-Powell, J. 2014. Simple Tech Creates Infant-Warmer to Save Lives in Developing Countries. Forbes , 29 January. Available: https://www.forbes.com/sites/jenniferhicks/2014/01/29/simple-tech-creates-infant-warmer-to-save-lives-in-developing-countries/?sh=df540aa758c1. Accessed 31 August 2022.

May, M. 2009. In Pursuit of Elegance . NY: Broadway Books.

McShane, S., M. Olekalns, and T. Travaglione. 2010. Organisational Behaviour on the Pacific Rim , 3rd ed. Sydney: McGraw Hill.

Osborn, A. 1953. Applied Imagination: Principles and Procedures of Creative Thinking . New York: Scribners.

Osborn, A. 1957. Applied Imagination: Principles and Procedures of Creative Thinking , 10th ed. New York: Scribners.

Page, S.E. 2007. The Difference: How the power of Diversity Creates Better Groups, Firms, Schools, and Societies . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Page, S.E. 2011. Diversity and Complexity . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Page, S.E. 2012. The Hidden Factor: Why Thinking Differently Is Your Greatest Asset . Chantilly, Virginia: The Great Courses.

Payne, M. 2014. How to Kill a Unicorn: How the World’s Hottest Innovation Factory Builds Bold Ideas That Make It to Market . New York: Crown Business.

Potter, A., M. McClure, and K. Sellers. 2010. Mass Collaboration Problem Solving: A New Approach to Wicked Problems. Proceedings of 2010 International Symposium on Collaborative Technologies and Systems . IEEE Explore, Chicago, Illinois. May 17–21: 398–407.

Prestero, T. 2012. Design for People, Not Awards. TEDxBoston . Available: https://www.ted.com/speakers/timothy_prestero. Accessed 30 August 2022.

Proctor, T. 2013. Creative Problem Solving for Managers: Developing Skills for Decision Making and Managers , 4th ed. New York: Routledge.

Puccio, G.J. 2012. Creativity Rising: Creative Thinking and Creative Problem Solving in the 21st Century . Buffalo, NY: ICSC Press.

Rittel, H.W.J., and M.M. Webber. 1973. Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. Policy Sciences 4 (2), June: 155–169.

Roberto, M. 2009. The Art of Critical Decision Making: The Great Courses. Chantilly, Virginia: The Teaching Company.

Roy, A. 2020. Arundhati Roy: “The Pandemic is a Portal”. Financial Times , April 4. Available: https://www.ft.com/content/10d8f5e8-74eb-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca . Accessed 28 February 2022.

Ruggiero, V.R. 2009. The Art of Thinking: A Guide to Critical and Creative Thought , 9th ed. New York: Longman.

Sawyer, K. 2007. Group Genius: The Creative Power of Collaboration . New York: Basic Books.

Schuelke-Leech, B. 2021. A Problem Taxonomy for Engineering. IEEE Transactions on Technology and Society 2 (2), June: 105.

Stellar, D. 2010. The PlayPump: What Went Wrong? State of the Planet, Columbia Climate School. Columbia University. Available: https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2010/07/01/the-playpump-what-went-wrong/. Accessed 30 August 2022.

Surowiecki, J. 2004. The Wisdom of Crowds: Why the Many Are Smarter than the Few and How Collective Wisdom Shapes Businesses, Economies, Societies and Nations . New York: Anchor Books.

Sweet, C., H. Blythe, and R. Carpenter. 2021. Creativity in the Time of COVID-19: Three Principles. The National Teaching and Learning Forum. 30 (5): 6–8.

Taibbi, R. 2011. The Tao of Improv: 5 Rules for Improvising Your Life. Psychology Today , 25 January. Available: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/fixing-families/201101/the-tao-improv-5-rules-improvising-your-life. Accessed 1 September 2022.

Walton, M. 2010. Playpump is Not a Panacea for Africa’s Water Problems. Circle of Blue , July 24. Available: http://www.circleofblue.org/waternews/2010/world/playpump-not-a-panacea-for-africas-water-problems/. Accessed 30 August 2022.

World Health Organization (WHO). 2022. Child Mortality (Under 5 Years). Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/levels-and-trends-in-child-under-5-mortality-in-2020. Accessed 28 February 2022.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Humanities and Social Sciences, Sheridan Institute of Higher Education, Perth, WA, Australia

Terence Lee

Media and Communication, Murdoch University, Perth, WA, Australia

Lauren O’Mahony

Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, Murdoch University, Perth, WA, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Terence Lee .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Lee, T., O’Mahony, L., Lebeck, P. (2023). Creative Problem-Solving. In: Creativity and Innovation. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-8880-6_5

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-8880-6_5

Published : 29 January 2023

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-19-8879-0

Online ISBN : 978-981-19-8880-6

eBook Packages : Business and Management Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- A Step-by-Step Guide to A3 Problem Solving Methodology

- Learn Lean Sigma

- Problem Solving

Problem-solving is an important component of any business or organization. It entails identifying, analyzing, and resolving problems in order to improve processes, drive results, and foster a culture of continuous improvement. A3 Problem solving is one of the most effective problem-solving methodologies.

A3 Problem solving is a structured and systematic approach to problem-solving that originated with the lean manufacturing methodology. It visualizes the problem-solving process using a one-page document known as an A3 report. The A3 report provides an overview of the problem, data analysis, root causes, solutions, and results in a clear and concise manner.

A3 Problem Solving has numerous advantages, including improved communication, better decision-making, increased efficiency, and reduced waste. It is a powerful tool for businesses of all sizes and industries, and it is especially useful for solving complex and multi-faceted problems.

In this blog post, we will walk you through the A3 Problem Solving methodology step by step. Whether you are new to A3 Problem Solving or simply want to improve your skills, this guide will help you understand and apply the process in your workplace.

Table of Contents

What is a3 problem solving.

A3 Problem Solving is a structured and systematic approach to problem-solving that makes use of a one-page document called an A3 report to visually represent the process. The A3 report provides an overview of the problem, data analysis, root causes, solutions, and results in a clear and concise manner. The method was created within the framework of the Lean manufacturing methodology and is based on the principles of continuous improvement and visual management.

Looking for a A3 Problem solving template? Click here

Origin and History of A3 Problem Solving

A3 Problem Solving was developed by Toyota Motor Corporation and was first used in the manufacture of automobiles. The term “A3” refers to the size of the paper used to create the report, which is an ISO standard known as “A3”. The goal of the A3 report is to provide a visual representation of the problem-solving process that all members of the organisation can easily understand and share. A3 Problem Solving has been adopted by organisations in a variety of industries over the years, and it has become a widely used and recognised method for problem-solving.

Key Principles of A3 Problem Solving

The following are the key principles of A3 Problem Solving:

- Define the problem clearly and concisely

- Gather and analyze data to gain a deep understanding of the problem

- Identify the root causes of the problem

- Develop and implement effective solutions

- Evaluate results and continuously improve

These principles serve as the foundation of the A3 Problem Solving methodology and are intended to assist organisations in continuously improving and achieving their objectives. Organizations can effectively solve problems, identify areas for improvement, and drive results by adhering to these principles.

Step 1: Define the Problem

Importance of clearly defining the problem.

The first step in the A3 Problem Solving process is critical because it lays the groundwork for the remaining steps. To define the problem clearly and accurately, you must first understand the problem and identify the underlying root cause. This step is critical because if the problem is not correctly defined, the rest of the process will be based on incorrect information, and the solution developed may not address the issue effectively.

The significance of defining the problem clearly cannot be overstated. It aids in the collection and analysis of relevant data, which is critical for developing effective solutions. When the problem is clearly defined, the data gathered is more relevant and targeted, resulting in a more comprehensive understanding of the issue. This will enable the development of solutions that are more likely to be effective because they are founded on a thorough and accurate understanding of the problem.

However, if the problem is not clearly defined, the data gathered may be irrelevant or incorrect, resulting in incorrect conclusions and ineffective solutions. Furthermore, the process of collecting and analysing data can become time-consuming and inefficient, resulting in resource waste. Furthermore, if the problem is not accurately defined, the solutions developed may fail to address the root cause of the problem, resulting in ongoing issues and a lack of improvement.

Techniques for Defining the Problem

The first step in the A3 Problem Solving process is to clearly and accurately define the problem. This is an important step because a clearly defined problem will help to ensure that the appropriate data is collected and solutions are developed. If the problem is not clearly defined, incorrect data may be collected, solutions that do not address the root cause of the problem, and time and resources may be wasted.

A problem can be defined using a variety of techniques, including brainstorming , root cause analysis , process mapping , and Ishikawa diagrams . Each of these techniques has its own advantages and disadvantages and can be used in a variety of situations depending on the nature of the problem.

Best Practice for Defining the Problem

In addition to brainstorming, root cause analysis, process mapping, and Ishikawa diagram s, best practices should be followed when defining a problem in A3 Problem Solving. Among these best practices are:

- Define the issue in a specific and quantifiable way: It is critical to be specific and concise when defining the problem, as well as to quantify the problem in terms of its impact. This will help to ensure that all stakeholders understand the problem and that data collection is focused on the right areas.

- Focus on the problem’s root cause: The A3 Problem Solving methodology is intended to assist organisations in identifying and addressing the root cause of a problem, rather than just the symptoms. Organizations can ensure that their solutions are effective and long-lasting by focusing on the root cause of the problem.

- Ascertain that all stakeholders agree on the problem’s definition: All stakeholders must agree on the definition of the problem for the A3 Problem Solving process to be effective. This ensures that everyone is working towards the same goal and that the solutions developed are relevant and appropriate.

- Consider the problem’s impact on the organisation and its stakeholders: It is critical to consider the impact of the problem on the organisation and its stakeholders when defining it. This will assist in ensuring that the appropriate data is gathered and that the solutions developed are relevant and appropriate.

Organizations can ensure that their problem is defined in a way that allows for effective data collection, analysis, and solution development by following these best practices. This will aid in the development of appropriate solutions and the effective resolution of the problem, resulting in improvements in the organization’s processes and outcomes.

Step 2: Gather Data

Gathering data in a3 problem solving.

Data collection is an important step in the A3 Problem Solving process because it allows organisations to gain a thorough understanding of the problem they are attempting to solve. This step entails gathering pertinent information about the problem, such as data on its origin, impact, and any related factors. This information is then used to help identify root causes and develop effective solutions.

One of the most important advantages of data collection in A3 Problem Solving is that it allows organisations to identify patterns and trends in data, which can be useful in determining the root cause of the problem. This information can then be used to create effective solutions that address the problem’s root cause rather than just its symptoms.

In A3 Problem Solving, data collection is a collaborative effort involving all stakeholders, including those directly impacted by the problem and those with relevant expertise or experience. Stakeholders can ensure that all relevant information is collected and that the data is accurate and complete by working together.

Overall, data collection is an important step in the A3 Problem Solving process because it serves as the foundation for effective problem-solving. Organizations can gain a deep understanding of the problem they are attempting to solve and develop effective solutions that address its root cause by collecting and analysing relevant data.

Data Collection Methods

In A3 Problem Solving, several data collection methods are available, including:

- Observations

- Process diagrams

The best data collection method will be determined by the problem being solved and the type of data required. To gain a complete understanding of the problem, it is critical to use multiple data collection methods.

Tools for Data Analysis and Visualization

Once the data has been collected, it must be analysed and visualised in order to gain insights into the problem. This process can be aided by the following tools:

- Excel Spreadsheets

- Flow diagrams

- Pareto diagrams

- Scatter Plots

- Control diagrams

These tools can assist in organising data and making it easier to understand. They can also be used to generate visual representations of data, such as graphs and charts, to communicate the findings to others.

Finally, the data collection and analysis step is an important part of the A3 Problem Solving process. Organizations can gain a better understanding of the problem and develop effective solutions by collecting and analysing relevant data.

Step 3: Identify Root Causes

Identifying the root causes of the problem is the third step in the A3 Problem Solving process. This step is critical because it assists organisations in understanding the root causes of a problem rather than just its symptoms. Once the underlying cause of the problem is identified, it can be addressed more effectively, leading to more long-term solutions.

Overview of the Root Cause Analysis Process

The process of determining the underlying causes of a problem is known as root cause analysis. This process can assist organisations in determining why a problem is occurring and what can be done to prevent it from recurring in the future. The goal of root cause analysis is to identify the underlying cause of a problem rather than just its symptoms, allowing it to be addressed more effectively.

To understand Root cause analysis in more detail check out RCA in our Lean Six Sigma Yellow Belt Course Root Cause Analysis section

Techniques for Identifying Root Causes

There are several techniques for determining the root causes of a problem, including:

- Brainstorming

- Ishikawa diagrams (also known as fishbone diagrams)

- Root Cause Tree Analysis

These methods can be used to investigate the issue in-depth and identify potential root causes. Organizations can gain a deeper understanding of the problem and identify the underlying causes that must be addressed by using these techniques.

Best Practices for Conducting Root Cause Analysis

It is critical to follow these best practices when conducting root cause analysis in A3 Problem Solving:

- Make certain that all stakeholders participate in the root cause analysis process.

- Concentrate on determining the root cause of the problem rather than just its symptoms.

- Take into account all potential root causes, not just the most obvious ones.

- To identify root causes, use a systematic approach, such as the 5 Whys or root cause tree analysis.

Organizations can ensure that root cause analysis is carried out effectively and that the root cause of the problem is identified by adhering to these best practises. This will aid in the development of appropriate solutions and the effective resolution of the problem.

Step 4: Develop Solutions

Developing solutions is the fourth step in the A3 Problem Solving process. This entails generating ideas and options for dealing with the problem, followed by selecting the best solution. The goal is to develop a solution that addresses the root cause of the problem and prevents it from recurring.

Solution Development in A3 Problem Solving

A3 solution development Problem solving is an iterative process in which options are generated and evaluated. The data gathered in the previous steps, as well as the insights and understanding gained from the root cause analysis, guide this process. The solution should be based on a thorough understanding of the problem and address the underlying cause.

Techniques for Developing Solutions

There are several techniques that can be used to develop solutions in A3 Problem Solving, including:

- Brainwriting

- Solution matrix

- Multi voting

- Force field analysis

These techniques can help to generate a range of options and to select the best solution.

Best Practice for Developing Solutions

It is critical to follow the following best practices when developing solutions in A3 Problem Solving:

- Participate in the solution development process with all stakeholders.

- Make certain that the solution addresses the underlying cause of the problem.

- Make certain that the solution is feasible and achievable.

- Consider the solution’s impact on the organisation and its stakeholders.

Organizations can ensure that the solutions they develop are effective and sustainable by adhering to these best practises. This will help to ensure that the problem is addressed effectively and that it does not reoccur.

Step 5: Implement Solutions

The final and most important step in the A3 Problem Solving methodology is solution implementation. This is the stage at which the identified and developed solutions are put into action to address the problem. This step’s goal is to ensure that the solutions are effective, efficient, and long-lasting.

The implementation Process

The implementation process entails putting the solutions developed in the previous step into action. This could include changes to processes, procedures, and systems, as well as employee training and education. To ensure that the solutions are effective, the implementation process should be well-planned and meticulously executed.

Techniques for Implementing Solutions

A3 Problem Solving solutions can be implemented using a variety of techniques, including:

- Piloting the solution on a small scale before broadening its application

- Participating in the implementation process with all relevant stakeholders

- ensuring that the solution is in line with the goals and objectives of the organisation

- Monitoring the solution to determine its effectiveness and make any necessary changes

Best Practice for Implementing Solutions

It is critical to follow these best practices when implementing solutions in A3 Problem Solving:

Make certain that all relevant stakeholders are involved and supportive of the solution. Have a clear implementation plan that outlines the steps, timeline, and resources required. Continuously monitor and evaluate the solution to determine its efficacy and make any necessary changes. Encourage all stakeholders to communicate and collaborate openly. Organizations can ensure that solutions are effectively implemented and problems are effectively addressed by adhering to these best practices. The ultimate goal is to find a long-term solution to the problem and improve the organization’s overall performance.

In conclusion, A3 Problem Solving is a comprehensive and structured methodology for problem-solving that can be applied in various industries and organisations. The A3 Problem Solving process’s five steps – Define the Problem, Gather Data, Identify Root Causes, Develop Solutions, and Implement Solutions – provide a road map for effectively addressing problems and making long-term improvements.

Organizations can improve their problem-solving skills and achieve better results by following the key principles, techniques, and best practices outlined in this guide. As a result, both the organisation and its stakeholders will benefit from increased efficiency, effectiveness, and satisfaction. So, whether you’re an experienced problem solver or just getting started, consider incorporating the A3 Problem Solving methodology into your work and start reaping the benefits right away.

Daniel Croft

Daniel Croft is a seasoned continuous improvement manager with a Black Belt in Lean Six Sigma. With over 10 years of real-world application experience across diverse sectors, Daniel has a passion for optimizing processes and fostering a culture of efficiency. He's not just a practitioner but also an avid learner, constantly seeking to expand his knowledge. Outside of his professional life, Daniel has a keen Investing, statistics and knowledge-sharing, which led him to create the website learnleansigma.com, a platform dedicated to Lean Six Sigma and process improvement insights.

Free Lean Six Sigma Templates

Improve your Lean Six Sigma projects with our free templates. They're designed to make implementation and management easier, helping you achieve better results.

5S Floor Marking Best Practices

In lean manufacturing, the 5S System is a foundational tool, involving the steps: Sort, Set…

How to Measure the ROI of Continuous Improvement Initiatives

When it comes to business, knowing the value you’re getting for your money is crucial,…

8D Problem-Solving: Common Mistakes to Avoid

In today’s competitive business landscape, effective problem-solving is the cornerstone of organizational success. The 8D…

The Evolution of 8D Problem-Solving: From Basics to Excellence

In a world where efficiency and effectiveness are more than just buzzwords, the need for…

8D: Tools and Techniques

Are you grappling with recurring problems in your organization and searching for a structured way…

How to Select the Right Lean Six Sigma Projects: A Comprehensive Guide

Going on a Lean Six Sigma journey is an invigorating experience filled with opportunities for…

- Search Search Search …

- Search Search …

Taking a systems thinking approach to problem solving

Systems thinking is an approach that considers a situation or problem holistically and as part of an overall system which is more than the sum of its parts. Taking the big picture perspective, and looking more deeply at underpinnings, systems thinking seeks and offers long-term and fundamental solutions rather than quick fixes and surface change.

Whether in environmental science, organizational change management, or geopolitics, some problems are so large, so complicated and so enduring that it’s hard to know where to begin when seeking a solution.

A systems thinking approach might be the ideal way to tackle essentially systemic problems. Our article sets out the basic concepts and ideas.

What is systems thinking?

Systems thinking is an approach that views an issue or problem as part of a wider, dynamic system. It entails accepting the system as an entity in its own right rather than just the sum of its parts, as well as understanding how individual elements of a system influence one another.

When we consider the concepts of a car, or a human being we are using a systems thinking perspective. A car is not just a collection of nuts, bolts, panels and wheels. A human being is not simply an assembly of bones, muscles, organs and blood.

In a systems thinking approach, as well as the specific issue or problem in question, you must also look at its wider place in an overall system, the nature of relationships between that issue and other elements of the system, and the tensions and synergies that arise from the various elements and their interactions.

The history of systems thinking is itself innately complex, with roots in many important disciplines of the 20th century including biology, computing and data science. As a discipline, systems thinking is still evolving today.

How can systems thinking be applied to problem solving?

A systems thinking approach to problem solving recognizes the problem as part of a wider system and addresses the whole system in any solution rather than just the problem area.

A popular way of applying a systems thinking lens is to examine the issue from multiple perspectives, zooming out from single and visible elements to the bigger and broader picture (e.g. via considering individual events, and then the patterns, structures and mental models which give rise to them).

Systems thinking is best applied in fields where problems and solutions are both high in complexity. There are a number of characteristics that can make an issue particularly compatible with a systems thinking approach:

- The issue has high impact for many people.

- The issue is long-term or chronic rather than a one-off incident.

- There is no obvious solution or answer to the issue and previous attempts to solve it have failed.

- We have a good knowledge of the issue’s environment and history through which we can sensibly place it in a systems context.

If your problem does not have most of these characteristics, systems thinking analysis may not work well in solving it.

Areas where systems thinking is often useful include health, climate change, urban planning, transport or ecology.

What is an example of a systems thinking approach to problem solving?

A tool called the iceberg mode l can be useful in learning to examine issues from a systems thinking perspective. This model frames an issue as an iceberg floating in a wider sea, with one small section above the water and three large sections unseen below.

The very tip of the iceberg, visible above the waterline, shows discrete events or occurrences which are easily seen and understood. For example, successive failures of a political party to win national elections.

Beneath the waterline and invisible, lie deeper and longer-term trends or patterns of behavior. In our example this might be internal fighting in the political party which overshadows and obstructs its public campaigning and weakens its leadership and reputation.

Even deeper under the water we can find underlying causes and supporting structures which underpin the patterns and trends.

For our failing political party, this could mean party rules and processes which encourage internal conflict and division rather than resolving them, and put off the best potential candidates from standing for the party in elections.

The electoral system in the country may also be problematic or unfair, making the party so fearful and defensive against losing its remaining support base, that it has no energy or cash to campaign on a more positive agenda and win new voters.

Mental models

At the very base of the iceberg, deepest under the water, lie the mental models that allow the rest of the iceberg to persist in this shape. These include the assumptions, attitudes, beliefs and motivations which drive the behaviors, patterns and events seen further up in the iceberg.

In this case, this could be the belief amongst senior party figures that they’ve won in the past and can therefore win again someday by repeating old campaigns. Or a widespread attitude amongst activists in all party wings that with the right party leader, all internal problems will melt away and voter preferences will turn overnight.

When is a systems thinking approach not helpful?

If you are looking for a quick answer to a simple question, or an immediate response to a single event, then systems thinking may overcomplicate the process of solving your problem and provide you with more information than is helpful, and in slower time than you need.

For example, if a volcano erupts and the local area needs to be immediately evacuated, applying a thorough systems thinking approach to life in the vicinity of an active volcano is unlikely to result in a more efficient crisis response or save more lives. After the event, systems thinking might be more constructive when considering town rebuilding, local logistics and transport links.

In general, if a problem is short-term, narrow and/or linear, systems thinking may not be the right model of thinking to use.

A final word…

The biggest problems in the real world are rarely simple in nature and expecting a quick and simple solution to something like climate change or cancer would be naive.

If you’d like to know more about applying systems thinking in real life there are many online resources, books and courses you can access, including in specific fields (e.g. FutureLearn’s course on Understanding Systems Thinking in Healthcare ).

Whether you think of it as zooming out to the big picture while retaining a focus on the small, or looking deeper under the water at the full shape of the iceberg, systems thinking can be a powerful tool for finding solutions that recognize the interactions and interdependence of individual elements in the real world.

You may also like

Systems Thinking for School Leaders: A Comprehensive Approach to Educational Management

Systems thinking is a powerful approach that school leaders can harness to navigate the complex landscape of education. With increasing challenges, such […]

How Systems Thinking Enhances Decision Making Skills: A Quick Guide

In today’s complex world, effective decision-making skills are more important than ever. One powerful approach to enhance these skills is through the […]

5 Ways to Apply Systems Thinking to Your Business Operations: A Strategic Guide

In today’s fast-paced business world, success depends on the ability to stay agile, resilient, and relevant. This is where systems thinking, an […]

Exploring Critical Thinking vs. Systems Thinking

There are many differences between Critical Thinking vs Systems Thinking. Critical Thinking involves examining and challenging thoughts or ideas, while Systems Thinking […]

BUS403: Negotiations and Conflict Management

Problem-Solving and Decision-Making in Groups

This text summarizes common characteristics of problems and the five steps in group problem-solving. The reading describes brainstorming and discussions that should occur before group decision-making, compares and contrasts decision-making techniques, and explores various influences on decision-making. The section "Getting Competent" emphasizes the need for leaders and managers to delegate tasks and responsibilities as they identify specialized skills among their teams and employees.

Group Problem-Solving Process

Group problem-solving can be a confusing puzzle unless it is approached systematically.

There are several variations of similar problem-solving models based on American scholar John Dewey's reflective thinking process. As you read through the steps in the process, think about how you can apply what we learned regarding the general and specific elements of problems. Some of the following steps are straightforward, and they are things we would logically do when faced with a problem.

However, taking a deliberate and systematic approach to problem-solving has been shown to benefit group functioning and performance. A deliberate approach is especially beneficial for groups that do not have an established history of working together and will only be able to meet occasionally.

Although a group should attend to each step of the process, group leaders or other group members who facilitate problem-solving should be cautious not to dogmatically follow each element of the process or force a group along. Such a lack of flexibility could limit group member input and negatively affect cohesion and climate.

Step 1: Define the Problem

Define the problem by considering the three elements shared by every problem: the current undesirable situation, the goal or more desirable situation, and obstacles. At this stage, group members share what they know about the current situation, without proposing solutions or evaluating the information.

Here are some good questions to ask during this stage: What is the current difficulty? How did we come to know that the difficulty exists? Who/what is involved? Why is it meaningful/urgent/important? What have the effects been so far? What, if any, elements of the difficulty require clarification?

At the end of this stage, the group should be able to compose a single sentence that summarizes the problem called a problem statement . Avoid wording in the problem statement or question that hints at potential solutions. A small group formed to investigate ethical violations of city officials could use the following problem statement: "Our state does not currently have a mechanism for citizens to report suspected ethical violations by city officials".

Step 2: Analyze the Problem

During this step a group should analyze the problem and the group's relationship to the problem. Whereas the first step involved exploring the "what" related to the problem, this step focuses on the "why." At this stage, group members can discuss the potential causes of the difficulty. Group members may also want to begin setting an agenda or timeline for the group's problem-solving process, looking forward to the other steps.

To fully analyze the problem, the group can discuss the five common problem variables discussed before. Here are two examples of questions that the group formed to address ethics violations might ask: Why doesn't our city have an ethics reporting mechanism? Do cities of similar size have such a mechanism? Once the problem has been analyzed, the group can pose a problem question that will guide the group as it generates possible solutions. "How can citizens report suspected ethical violations of city officials and how will such reports be processed and addressed?" As you can see, the problem question is more complex than the problem statement, since the group has moved on to more in-depth discussion of the problem during step 2.

Step 3: Generate Possible Solutions

During this step, group members generate possible solutions to the problem. Again, solutions should not be evaluated at this point, only proposed and clarified. The question should be, "What could we do to address this problem?" not "What should we do to address it?" It is perfectly OK for a group member to question another person's idea by asking something like "What do you mean?" or "Could you explain your reasoning more?"