Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

SOCRATES ON EDUCATION

Related Papers

Alfred S I M I Y U Khisa

Anthony Long

Anne-Marie Schultz

In this paper, I explore three autobiographical narratives that Plato’s Socrates tells: his report of his conversations with Diotima (Symposium 201d–212b), his account of his testing of the Delphic oracle (Apology 21a–23a), and his description of his turn fromnaturalistic philosophy to his own method of inquiry (Phaedo 96a–100b).1 This Platonic Socrates shows his auditors how to philosophize for the future through a narrative recollection of his own past. In these stories, Plato presents us with an image of a Socrates who prepares others to do philosophy without him. In doing so, Plato’s Socrates exhibits philosophical care for his students. In the first part of the paper, I briefly discuss Socrates’ overall narrative style as Plato depicts it in the five dialogues that Socrates narrates. I then analyze each of these autobiographical accounts with an eye toward uncovering what they reveal about Plato’s presentation of Socrates’ philosophical practice.2 Finally, I offer a brief description of what it might mean to practice philosophy as care for self and care for others in a Socratic fashion.

Sara Ahbel-Rappe

Matus Porubjak

This philosophical essay aims to return to the Socratic problem, ask it anew, and make an attempt to find its possible solution. In the introduction, the author briefly discusses to genesis of the Socratic problem and the basic methodological problems we encounter when dealing with it. Further on, it defines five basic sources of information about Socrates on which the interpretation tradition is based. Then the author outlines two key features of Socrates’ personality, aligned with the vast majority of sources: (1) Socrates’ belief that he has no theoretical knowledge; (2) Socrates’ predilection towards practical questions, and the practical dimension of his activity. In conclusion, the author expresses his belief that it is just this practical dimension of philosophy that has been in the ‘blind spot’ of the modern study of Socrates which paid too much attention to the search for his doctrine. The history of philosophy, however, does not only have to be the history of doctrines, but can also be the history of reflected life practices which inspire followers in their own practices while reflecting on them. The author therefore proposes to understand the historical Socrates as the paradigmatic figure of practical philosophy.

Dimitri El Murr

Philosophy in Review

Patrick Mooney

Peter J Ahrensdorf

Quantity: 1 Order Available as a Google eBook for other eReaders and tablet devices. Click icon below... Summary Shows that the dialogue in Plato's Phaedo is primarily devoted to presenting Socrates' final defense of the philosophical life against the theoretical and political challenge of religion. "That the psychology of its characters is a key to understanding the argument of a Platonic dialogue is a principle effectively applied in this reading of the Phaedo and well supported by the results: in bringing out the differences in the perspectives of Socrates' two interlocutors on this occasion-one primarily concerned with the question of the goodness of the philosophic life, and indeed of life as such, the other motivated by a deep skepticism about the possibilities of human reason-this study leads us to see why the conversation in the Phaedo has to be divided between them, and how the strategy of each argument is motivated by its particular addressee."-Ronna Burger, Tulane University While the Phaedo is most famous for its moving portrayal of Socrates' death and its arguments for the immortality of the soul, Ahrensdorf argues that the dialogue is primarily devoted to presenting Socrates' final defense of the philosophic life against the theoretical and political challenge of religion. Through a careful analysis of both the historical context of the Phaedo and the arguments and drama of the dialogue, Ahrensdorf argues that Socrates' defense of rationalism is singularly undogmatic and that a study of that defense can lead us to a clearer understanding and a deeper and richer appreciation of the case both for and against rationalism. "This clear, extremely well-written book distinguishes itself from other fine works on the Phaedo by its careful attention to Socrates' rhetoric. It does a masterful job of showing how Socrates intends his arguments to affect Simmias and Cebes-as well as readers like them-even in cases where Socrates must have seen those arguments to be logically weak. Ahrensdorf's insight into the differences between Simmias and Cebes is excellent."-Chris A. Colmo, Rosary College

Philosophical Investigations

Catherine Rowett

Journal Philosophical Study of Education

james M magrini

Nehamas (1999) emphatically stresses that Socrates is “not a teacher of arête,” but as educators know well, it is undeniably the case that Socrates is often “perceived as a teacher,” and beyond, held up as a paragon of pedagogy to be emulated and imitated (62). At his trial, Socrates is accused of “wrongdoing because he corrupts the youth and does not believe in the gods the state believes in” (Ap. 24c). Beyond these charges, he is accused, in the manner of Anaxagoras and other Greek physical scientists, of “investigating the things beneath the earth and in the heavens,” and also charged with, in the manner of the sophists, “making the weaker argument stronger,” importantly, Socrates is, according to his accusers, “teaching [/didaskon] these things to others” (Ap. 19b-c). In his defense (apologia), Socrates distances himself from both the natural philosophers and the sophists, such as Gorgias of Leontini, Prodicus of Ceos, and Hippias of Ellis, who all charge fees for their services and usually teach through speeches or didactic methods that communicate or transfer knowledge to their pupils. In light of these remarks, returning to Nehamas, although his accusers, and even his friends consider Socrates a teacher, this offers no valid reason or sufficient evidence for us “to refuse to take his own disavowal of that role as face value” (71). The Greek, “” (didaskalos) defines a “teacher or master” of one or another subject, such as rhetoric, medicine, craft making, or even poetry (Lexicon 2015, 169). With the understanding of the didaskalos related to the type of instruction in virtue (arête) offered by the sophists, it is against the charges of Meletus that Socrates emphatically denies that he is teacher, specifically of the virtues, claiming that he “was never anyone’s teacher” (Ap. 33a).

RELATED PAPERS

britney francis

장수출장안마 카톡 k n 3 9 장수출장샵 홈페지sod 27, N E T 장수콜걸샵 #E 장수출장맛사지 #E 장수모텔출장 #E 장수여대생출장 장수립카페 장수애인대행

LnqtJD lkdy

Jurnal Teknologi Pendidikan (JTP)

Intan Kesuma

El Lugar De Piglia Critica Sin Ficcion 2008 Isbn 978 84 936007 2 3 Pags 398 408

Vicente Luis Mora

JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery

Gerald Minkowitz

Studia sportiva

Ondřej JEŠINA

American Journal of Research

Tulkin Chulliev

Revue roumaine de mathématiques pures et appliquées

Dan Polişevschi

Turkan Aktas

Bojan Viculin

Altre Modernità

Jenny Stewart

IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science

erna tri herdiani

Radiation Measurements

Ricardo Reyes

Oriental journal of chemistry

Jai Acharya

Acta Ophthalmologica

Han Tun Aung

Asian journal of neurosurgery

jayendra kumar

Journal of Health Communication

Nicholas DiFonzo

Augustinus Simanjuntak

Dick Veltman

International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems

Muhammad Bashir Othman

Genome medicine

Rachel Dvoskin

Journal of Applied Physics

毕业证 成 绩 单 fgh

Open-file report /

David Prudic

Güntuğ BATIHAN

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

A newer edition of this book is available.

- < Previous chapter

6 (page 105) p. 105 Conclusion

- Published: October 2000

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The Conclusion argues that the historical importance of Socrates, unquestionable though it is, does not exhaust his significance, even for a secular, non-ideological age. As well as a historical person and a literary persona, Socrates is an exemplary figure, who challenges, encourages, and inspires. The Socratic method of challenging students to examine their beliefs, to revise them in the light of argument, and to arrive at answers through critical reflection on the information presented goes far beyond pedagogical strategy. ‘The unexamined life is not worth living for a human being’ expresses a central human value: the willingness to rethink one's own assumptions, thereby rejecting the tendency to complacent dogmatism.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

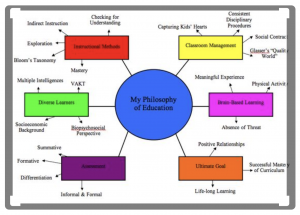

Philosophy of Education

Philosophy of education is the branch of applied or practical philosophy concerned with the nature and aims of education and the philosophical problems arising from educational theory and practice. Because that practice is ubiquitous in and across human societies, its social and individual manifestations so varied, and its influence so profound, the subject is wide-ranging, involving issues in ethics and social/political philosophy, epistemology, metaphysics, philosophy of mind and language, and other areas of philosophy. Because it looks both inward to the parent discipline and outward to educational practice and the social, legal, and institutional contexts in which it takes place, philosophy of education concerns itself with both sides of the traditional theory/practice divide. Its subject matter includes both basic philosophical issues (e.g., the nature of the knowledge worth teaching, the character of educational equality and justice, etc.) and problems concerning specific educational policies and practices (e.g., the desirability of standardized curricula and testing, the social, economic, legal and moral dimensions of specific funding arrangements, the justification of curriculum decisions, etc.). In all this the philosopher of education prizes conceptual clarity, argumentative rigor, the fair-minded consideration of the interests of all involved in or affected by educational efforts and arrangements, and informed and well-reasoned valuation of educational aims and interventions.

Philosophy of education has a long and distinguished history in the Western philosophical tradition, from Socrates’ battles with the sophists to the present day. Many of the most distinguished figures in that tradition incorporated educational concerns into their broader philosophical agendas (Curren 2000, 2018; Rorty 1998). While that history is not the focus here, it is worth noting that the ideals of reasoned inquiry championed by Socrates and his descendants have long informed the view that education should foster in all students, to the extent possible, the disposition to seek reasons and the ability to evaluate them cogently, and to be guided by their evaluations in matters of belief, action and judgment. This view, that education centrally involves the fostering of reason or rationality, has with varying articulations and qualifications been embraced by most of those historical figures; it continues to be defended by contemporary philosophers of education as well (Scheffler 1973 [1989]; Siegel 1988, 1997, 2007, 2017). As with any philosophical thesis it is controversial; some dimensions of the controversy are explored below.

This entry is a selective survey of important contemporary work in Anglophone philosophy of education; it does not treat in detail recent scholarship outside that context.

1. Problems in Delineating the Field

2. analytic philosophy of education and its influence, 3.1 the content of the curriculum and the aims and functions of schooling, 3.2 social, political and moral philosophy, 3.3 social epistemology, virtue epistemology, and the epistemology of education, 3.4 philosophical disputes concerning empirical education research, 4. concluding remarks, other internet resources, related entries.

The inward/outward looking nature of the field of philosophy of education alluded to above makes the task of delineating the field, of giving an over-all picture of the intellectual landscape, somewhat complicated (for a detailed account of this topography, see Phillips 1985, 2010). Suffice it to say that some philosophers, as well as focusing inward on the abstract philosophical issues that concern them, are drawn outwards to discuss or comment on issues that are more commonly regarded as falling within the purview of professional educators, educational researchers, policy-makers and the like. (An example is Michael Scriven, who in his early career was a prominent philosopher of science; later he became a central figure in the development of the field of evaluation of educational and social programs. See Scriven 1991a, 1991b.) At the same time, there are professionals in the educational or closely related spheres who are drawn to discuss one or another of the philosophical issues that they encounter in the course of their work. (An example here is the behaviorist psychologist B.F. Skinner, the central figure in the development of operant conditioning and programmed learning, who in works such as Walden Two (1948) and Beyond Freedom and Dignity (1972) grappled—albeit controversially—with major philosophical issues that were related to his work.)

What makes the field even more amorphous is the existence of works on educational topics, written by well-regarded philosophers who have made major contributions to their discipline; these educational reflections have little or no philosophical content, illustrating the truth that philosophers do not always write philosophy. However, despite this, works in this genre have often been treated as contributions to philosophy of education. (Examples include John Locke’s Some Thoughts Concerning Education [1693] and Bertrand Russell’s rollicking pieces written primarily to raise funds to support a progressive school he ran with his wife. (See Park 1965.)

Finally, as indicated earlier, the domain of education is vast, the issues it raises are almost overwhelmingly numerous and are of great complexity, and the social significance of the field is second to none. These features make the phenomena and problems of education of great interest to a wide range of socially-concerned intellectuals, who bring with them their own favored conceptual frameworks—concepts, theories and ideologies, methods of analysis and argumentation, metaphysical and other assumptions, and the like. It is not surprising that scholars who work in this broad genre also find a home in the field of philosophy of education.

As a result of these various factors, the significant intellectual and social trends of the past few centuries, together with the significant developments in philosophy, all have had an impact on the content of arguments and methods of argumentation in philosophy of education—Marxism, psycho-analysis, existentialism, phenomenology, positivism, post-modernism, pragmatism, neo-liberalism, the several waves of feminism, analytic philosophy in both its ordinary language and more formal guises, are merely the tip of the iceberg.

Conceptual analysis, careful assessment of arguments, the rooting out of ambiguity, the drawing of clarifying distinctions—all of which are at least part of the philosophical toolkit—have been respected activities within philosophy from the dawn of the field. No doubt it somewhat over-simplifies the complex path of intellectual history to suggest that what happened in the twentieth century—early on, in the home discipline itself, and with a lag of a decade or more in philosophy of education—is that philosophical analysis came to be viewed by some scholars as being the major philosophical activity (or set of activities), or even as being the only viable or reputable activity. In any case, as they gained prominence and for a time hegemonic influence during the rise of analytic philosophy early in the twentieth century analytic techniques came to dominate philosophy of education in the middle third of that century (Curren, Robertson, & Hager 2003).

The pioneering work in the modern period entirely in an analytic mode was the short monograph by C.D. Hardie, Truth and Fallacy in Educational Theory (1941; reissued in 1962). In his Introduction, Hardie (who had studied with C.D. Broad and I.A. Richards) made it clear that he was putting all his eggs into the ordinary-language-analysis basket:

The Cambridge analytical school, led by Moore, Broad and Wittgenstein, has attempted so to analyse propositions that it will always be apparent whether the disagreement between philosophers is one concerning matters of fact, or is one concerning the use of words, or is, as is frequently the case, a purely emotive one. It is time, I think, that a similar attitude became common in the field of educational theory. (Hardie 1962: xix)

About a decade after the end of the Second World War the floodgates opened and a stream of work in the analytic mode appeared; the following is merely a sample. D. J. O’Connor published An Introduction to Philosophy of Education (1957) in which, among other things, he argued that the word “theory” as it is used in educational contexts is merely a courtesy title, for educational theories are nothing like what bear this title in the natural sciences. Israel Scheffler, who became the paramount philosopher of education in North America, produced a number of important works including The Language of Education (1960), which contained clarifying and influential analyses of definitions (he distinguished reportive, stipulative, and programmatic types) and the logic of slogans (often these are literally meaningless, and, he argued, should be seen as truncated arguments), Conditions of Knowledge (1965), still the best introduction to the epistemological side of philosophy of education, and Reason and Teaching (1973 [1989]), which in a wide-ranging and influential series of essays makes the case for regarding the fostering of rationality/critical thinking as a fundamental educational ideal (cf. Siegel 2016). B. O. Smith and R. H. Ennis edited the volume Language and Concepts in Education (1961); and R.D. Archambault edited Philosophical Analysis and Education (1965), consisting of essays by a number of prominent British writers, most notably R. S. Peters (whose status in Britain paralleled that of Scheffler in the United States), Paul Hirst, and John Wilson. Topics covered in the Archambault volume were typical of those that became the “bread and butter” of analytic philosophy of education (APE) throughout the English-speaking world—education as a process of initiation, liberal education, the nature of knowledge, types of teaching, and instruction versus indoctrination.

Among the most influential products of APE was the analysis developed by Hirst and Peters (1970) and Peters (1973) of the concept of education itself. Using as a touchstone “normal English usage,” it was concluded that a person who has been educated (rather than instructed or indoctrinated) has been (i) changed for the better; (ii) this change has involved the acquisition of knowledge and intellectual skills and the development of understanding; and (iii) the person has come to care for, or be committed to, the domains of knowledge and skill into which he or she has been initiated. The method used by Hirst and Peters comes across clearly in their handling of the analogy with the concept of “reform”, one they sometimes drew upon for expository purposes. A criminal who has been reformed has changed for the better, and has developed a commitment to the new mode of life (if one or other of these conditions does not hold, a speaker of standard English would not say the criminal has been reformed). Clearly the analogy with reform breaks down with respect to the knowledge and understanding conditions. Elsewhere Peters developed the fruitful notion of “education as initiation”.

The concept of indoctrination was also of great interest to analytic philosophers of education, for, it was argued, getting clear about precisely what constitutes indoctrination also would serve to clarify the border that demarcates it from acceptable educational processes. Thus, whether or not an instructional episode was a case of indoctrination was determined by the content taught, the intention of the instructor, the methods of instruction used, the outcomes of the instruction, or by some combination of these. Adherents of the different analyses used the same general type of argument to make their case, namely, appeal to normal and aberrant usage. Unfortunately, ordinary language analysis did not lead to unanimity of opinion about where this border was located, and rival analyses of the concept were put forward (Snook 1972). The danger of restricting analysis to ordinary language (“normal English usage”) was recognized early on by Scheffler, whose preferred view of analysis emphasized

first, its greater sophistication as regards language, and the interpenetration of language and inquiry, second, its attempt to follow the modern example of the sciences in empirical spirit, in rigor, in attention to detail, in respect for alternatives, and in objectivity of method, and third, its use of techniques of symbolic logic brought to full development only in the last fifty years… It is…this union of scientific spirit and logical method applied toward the clarification of basic ideas that characterizes current analytic philosophy [and that ought to characterize analytic philosophy of education]. (Scheffler 1973 [1989: 9–10])

After a period of dominance, for a number of important reasons the influence of APE went into decline. First, there were growing criticisms that the work of analytic philosophers of education had become focused upon minutiae and in the main was bereft of practical import. (It is worth noting that a 1966 article in Time , reprinted in Lucas 1969, had put forward the same criticism of mainstream philosophy.) Second, in the early 1970’s radical students in Britain accused Peters’ brand of linguistic analysis of conservatism, and of tacitly giving support to “traditional values”—they raised the issue of whose English usage was being analyzed?

Third, criticisms of language analysis in mainstream philosophy had been mounting for some time, and finally after a lag of many years were reaching the attention of philosophers of education; there even had been a surprising degree of interest on the part of the general reading public in the United Kingdom as early as 1959, when Gilbert Ryle, editor of the journal Mind , refused to commission a review of Ernest Gellner’s Words and Things (1959)—a detailed and quite acerbic critique of Wittgenstein’s philosophy and its espousal of ordinary language analysis. (Ryle argued that Gellner’s book was too insulting, a view that drew Bertrand Russell into the fray on Gellner’s side—in the daily press, no less; Russell produced a list of insulting remarks drawn from the work of great philosophers of the past. See Mehta 1963.)

Richard Peters had been given warning that all was not well with APE at a conference in Canada in 1966; after delivering a paper on “The aims of education: A conceptual inquiry” that was based on ordinary language analysis, a philosopher in the audience (William Dray) asked Peters “ whose concepts do we analyze?” Dray went on to suggest that different people, and different groups within society, have different concepts of education. Five years before the radical students raised the same issue, Dray pointed to the possibility that what Peters had presented under the guise of a “logical analysis” was nothing but the favored usage of a certain class of persons—a class that Peters happened to identify with (see Peters 1973, where to the editor’s credit the interaction with Dray is reprinted).

Fourth, during the decade of the seventies when these various critiques of analytic philosophy were in the process of eroding its luster, a spate of translations from the Continent stimulated some philosophers of education in Britain and North America to set out in new directions, and to adopt a new style of writing and argumentation. Key works by Gadamer, Foucault and Derrida appeared in English, and these were followed in 1984 by Lyotard’s The Postmodern Condition . The classic works of Heidegger and Husserl also found new admirers; and feminist philosophers of education were finding their voices—Maxine Greene published a number of pieces in the 1970s and 1980s, including The Dialectic of Freedom (1988); the influential book by Nel Noddings, Caring: A Feminine Approach to Ethics and Moral Education , appeared the same year as the work by Lyotard, followed a year later by Jane Roland Martin’s Reclaiming a Conversation . In more recent years all these trends have continued. APE was and is no longer the center of interest, although, as indicated below, it still retains its voice.

3. Areas of Contemporary Activity

As was stressed at the outset, the field of education is huge and contains within it a virtually inexhaustible number of issues that are of philosophical interest. To attempt comprehensive coverage of how philosophers of education have been working within this thicket would be a quixotic task for a large single volume and is out of the question for a solitary encyclopedia entry. Nevertheless, a valiant attempt to give an overview was made in A Companion to the Philosophy of Education (Curren 2003), which contains more than six-hundred pages divided into forty-five chapters each of which surveys a subfield of work. The following random selection of chapter topics gives a sense of the enormous scope of the field: Sex education, special education, science education, aesthetic education, theories of teaching and learning, religious education, knowledge, truth and learning, cultivating reason, the measurement of learning, multicultural education, education and the politics of identity, education and standards of living, motivation and classroom management, feminism, critical theory, postmodernism, romanticism, the purposes of universities, affirmative action in higher education, and professional education. The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Education (Siegel 2009) contains a similarly broad range of articles on (among other things) the epistemic and moral aims of education, liberal education and its imminent demise, thinking and reasoning, fallibilism and fallibility, indoctrination, authenticity, the development of rationality, Socratic teaching, educating the imagination, caring and empathy in moral education, the limits of moral education, the cultivation of character, values education, curriculum and the value of knowledge, education and democracy, art and education, science education and religious toleration, constructivism and scientific methods, multicultural education, prejudice, authority and the interests of children, and on pragmatist, feminist, and postmodernist approaches to philosophy of education.

Given this enormous range, there is no non-arbitrary way to select a small number of topics for further discussion, nor can the topics that are chosen be pursued in great depth. The choice of those below has been made with an eye to highlighting contemporary work that makes solid contact with and contributes to important discussions in general philosophy and/or the academic educational and educational research communities.

The issue of what should be taught to students at all levels of education—the issue of curriculum content—obviously is a fundamental one, and it is an extraordinarily difficult one with which to grapple. In tackling it, care needs to be taken to distinguish between education and schooling—for although education can occur in schools, so can mis-education, and many other things can take place there that are educationally orthogonal (such as the provision of free or subsidized lunches and the development of social networks); and it also must be recognized that education can occur in the home, in libraries and museums, in churches and clubs, in solitary interaction with the public media, and the like.

In developing a curriculum (whether in a specific subject area, or more broadly as the whole range of offerings in an educational institution or system), a number of difficult decisions need to be made. Issues such as the proper ordering or sequencing of topics in the chosen subject, the time to be allocated to each topic, the lab work or excursions or projects that are appropriate for particular topics, can all be regarded as technical issues best resolved either by educationists who have a depth of experience with the target age group or by experts in the psychology of learning and the like. But there are deeper issues, ones concerning the validity of the justifications that have been given for including/excluding particular subjects or topics in the offerings of formal educational institutions. (Why should evolution or creation “science” be included, or excluded, as a topic within the standard high school subject Biology? Is the justification that is given for teaching Economics in some schools coherent and convincing? Do the justifications for including/excluding materials on birth control, patriotism, the Holocaust or wartime atrocities in the curriculum in some school districts stand up to critical scrutiny?)

The different justifications for particular items of curriculum content that have been put forward by philosophers and others since Plato’s pioneering efforts all draw, explicitly or implicitly, upon the positions that the respective theorists hold about at least three sets of issues.

First, what are the aims and/or functions of education (aims and functions are not necessarily the same)? Many aims have been proposed; a short list includes the production of knowledge and knowledgeable students, the fostering of curiosity and inquisitiveness, the enhancement of understanding, the enlargement of the imagination, the civilizing of students, the fostering of rationality and/or autonomy, and the development in students of care, concern and associated dispositions and attitudes (see Siegel 2007 for a longer list). The justifications offered for all such aims have been controversial, and alternative justifications of a single proposed aim can provoke philosophical controversy. Consider the aim of autonomy. Aristotle asked, what constitutes the good life and/or human flourishing, such that education should foster these (Curren 2013)? These two formulations are related, for it is arguable that our educational institutions should aim to equip individuals to pursue this good life—although this is not obvious, both because it is not clear that there is one conception of the good or flourishing life that is the good or flourishing life for everyone, and it is not clear that this is a question that should be settled in advance rather than determined by students for themselves. Thus, for example, if our view of human flourishing includes the capacity to think and act autonomously, then the case can be made that educational institutions—and their curricula—should aim to prepare, or help to prepare, autonomous individuals. A rival justification of the aim of autonomy, associated with Kant, champions the educational fostering of autonomy not on the basis of its contribution to human flourishing, but rather the obligation to treat students with respect as persons (Scheffler 1973 [1989]; Siegel 1988). Still others urge the fostering of autonomy on the basis of students’ fundamental interests, in ways that draw upon both Aristotelian and Kantian conceptual resources (Brighouse 2005, 2009). It is also possible to reject the fostering of autonomy as an educational aim (Hand 2006).

Assuming that the aim can be justified, how students should be helped to become autonomous or develop a conception of the good life and pursue it is of course not immediately obvious, and much philosophical ink has been spilled on the general question of how best to determine curriculum content. One influential line of argument was developed by Paul Hirst, who argued that knowledge is essential for developing and then pursuing a conception of the good life, and because logical analysis shows, he argued, that there are seven basic forms of knowledge, the case can be made that the function of the curriculum is to introduce students to each of these forms (Hirst 1965; see Phillips 1987: ch. 11). Another, suggested by Scheffler, is that curriculum content should be selected so as “to help the learner attain maximum self-sufficiency as economically as possible.” The relevant sorts of economy include those of resources, teacher effort, student effort, and the generalizability or transfer value of content, while the self-sufficiency in question includes

self-awareness, imaginative weighing of alternative courses of action, understanding of other people’s choices and ways of life, decisiveness without rigidity, emancipation from stereotyped ways of thinking and perceiving…empathy… intuition, criticism and independent judgment. (Scheffler 1973 [1989: 123–5])

Both impose important constraints on the curricular content to be taught.

Second, is it justifiable to treat the curriculum of an educational institution as a vehicle for furthering the socio-political interests and goals of a dominant group, or any particular group, including one’s own; and relatedly, is it justifiable to design the curriculum so that it serves as an instrument of control or of social engineering? In the closing decades of the twentieth century there were numerous discussions of curriculum theory, particularly from Marxist and postmodern perspectives, that offered the sobering analysis that in many educational systems, including those in Western democracies, the curriculum did indeed reflect and serve the interests of powerful cultural elites. What to do about this situation (if it is indeed the situation of contemporary educational institutions) is far from clear and is the focus of much work at the interface of philosophy of education and social/political philosophy, some of which is discussed in the next section. A closely related question is this: ought educational institutions be designed to further pre-determined social ends, or rather to enable students to competently evaluate all such ends? Scheffler argued that we should opt for the latter: we must

surrender the idea of shaping or molding the mind of the pupil. The function of education…is rather to liberate the mind, strengthen its critical powers, [and] inform it with knowledge and the capacity for independent inquiry. (Scheffler 1973 [1989: 139])

Third, should educational programs at the elementary and secondary levels be made up of a number of disparate offerings, so that individuals with different interests and abilities and affinities for learning can pursue curricula that are suitable? Or should every student pursue the same curriculum as far as each is able?—a curriculum, it should be noted, that in past cases nearly always was based on the needs or interests of those students who were academically inclined or were destined for elite social roles. Mortimer Adler and others in the late twentieth century sometimes used the aphorism “the best education for the best is the best education for all.”

The thinking here can be explicated in terms of the analogy of an out-of-control virulent disease, for which there is only one type of medicine available; taking a large dose of this medicine is extremely beneficial, and the hope is that taking only a little—while less effective—is better than taking none at all. Medically, this is dubious, while the educational version—forcing students to work, until they exit the system, on topics that do not interest them and for which they have no facility or motivation—has even less merit. (For a critique of Adler and his Paideia Proposal , see Noddings 2015.) It is interesting to compare the modern “one curriculum track for all” position with Plato’s system outlined in the Republic , according to which all students—and importantly this included girls—set out on the same course of study. Over time, as they moved up the educational ladder it would become obvious that some had reached the limit imposed upon them by nature, and they would be directed off into appropriate social roles in which they would find fulfillment, for their abilities would match the demands of these roles. Those who continued on with their education would eventually become members of the ruling class of Guardians.

The publication of John Rawls’s A Theory of Justice in 1971 was the most notable event in the history of political philosophy over the last century. The book spurred a period of ferment in political philosophy that included, among other things, new research on educationally fundamental themes. The principles of justice in educational distribution have perhaps been the dominant theme in this literature, and Rawls’s influence on its development has been pervasive.

Rawls’s theory of justice made so-called “fair equality of opportunity” one of its constitutive principles. Fair equality of opportunity entailed that the distribution of education would not put the children of those who currently occupied coveted social positions at any competitive advantage over other, equally talented and motivated children seeking the qualifications for those positions (Rawls 1971: 72–75). Its purpose was to prevent socio-economic differences from hardening into social castes that were perpetuated across generations. One obvious criticism of fair equality of opportunity is that it does not prohibit an educational distribution that lavished resources on the most talented children while offering minimal opportunities to others. So long as untalented students from wealthy families were assigned opportunities no better than those available to their untalented peers among the poor, no breach of the principle would occur. Even the most moderate egalitarians might find such a distributive regime to be intuitively repugnant.

Repugnance might be mitigated somewhat by the ways in which the overall structure of Rawls’s conception of justice protects the interests of those who fare badly in educational competition. All citizens must enjoy the same basic liberties, and equal liberty always has moral priority over equal opportunity: the former can never be compromised to advance the latter. Further, inequality in the distribution of income and wealth are permitted only to the degree that it serves the interests of the least advantaged group in society. But even with these qualifications, fair equality of opportunity is arguably less than really fair to anyone. The fact that their education should secure ends other than access to the most selective social positions—ends such as artistic appreciation, the kind of self-knowledge that humanistic study can furnish, or civic virtue—is deemed irrelevant according to Rawls’s principle. But surely it is relevant, given that a principle of educational justice must be responsive to the full range of educationally important goods.

Suppose we revise our account of the goods included in educational distribution so that aesthetic appreciation, say, and the necessary understanding and virtue for conscientious citizenship count for just as much as job-related skills. An interesting implication of doing so is that the rationale for requiring equality under any just distribution becomes decreasingly clear. That is because job-related skills are positional whereas the other educational goods are not (Hollis 1982). If you and I both aspire to a career in business management for which we are equally qualified, any increase in your job-related skills is a corresponding disadvantage to me unless I can catch up. Positional goods have a competitive structure by definition, though the ends of civic or aesthetic education do not fit that structure. If you and I aspire to be good citizens and are equal in civic understanding and virtue, an advance in your civic education is no disadvantage to me. On the contrary, it is easier to be a good citizen the better other citizens learn to be. At the very least, so far as non-positional goods figure in our conception of what counts as a good education, the moral stakes of inequality are thereby lowered.

In fact, an emerging alternative to fair equality of opportunity is a principle that stipulates some benchmark of adequacy in achievement or opportunity as the relevant standard of distribution. But it is misleading to represent this as a contrast between egalitarian and sufficientarian conceptions. Philosophically serious interpretations of adequacy derive from the ideal of equal citizenship (Satz 2007; Anderson 2007). Then again, fair equality of opportunity in Rawls’s theory is derived from a more fundamental ideal of equality among citizens. This was arguably true in A Theory of Justice but it is certainly true in his later work (Dworkin 1977: 150–183; Rawls 1993). So, both Rawls’s principle and the emerging alternative share an egalitarian foundation. The debate between adherents of equal opportunity and those misnamed as sufficientarians is certainly not over (e.g., Brighouse & Swift 2009; Jacobs 2010; Warnick 2015). Further progress will likely hinge on explicating the most compelling conception of the egalitarian foundation from which distributive principles are to be inferred. Another Rawls-inspired alternative is that a “prioritarian” distribution of achievement or opportunity might turn out to be the best principle we can come up with—i.e., one that favors the interests of the least advantaged students (Schouten 2012).

The publication of Rawls’s Political Liberalism in 1993 signaled a decisive turning point in his thinking about justice. In his earlier book, the theory of justice had been presented as if it were universally valid. But Rawls had come to think that any theory of justice presented as such was open to reasonable rejection. A more circumspect approach to justification would seek grounds for justice as fairness in an overlapping consensus between the many reasonable values and doctrines that thrive in a democratic political culture. Rawls argued that such a culture is informed by a shared ideal of free and equal citizenship that provided a new, distinctively democratic framework for justifying a conception of justice. The shift to political liberalism involved little revision on Rawls’s part to the content of the principles he favored. But the salience it gave to questions about citizenship in the fabric of liberal political theory had important educational implications. How was the ideal of free and equal citizenship to be instantiated in education in a way that accommodated the range of reasonable values and doctrines encompassed in an overlapping consensus? Political Liberalism has inspired a range of answers to that question (cf. Callan 1997; Clayton 2006; Bull 2008).

Other philosophers besides Rawls in the 1990s took up a cluster of questions about civic education, and not always from a liberal perspective. Alasdair Macintyre’s After Virtue (1984) strongly influenced the development of communitarian political theory which, as its very name might suggest, argued that the cultivation of community could preempt many of the problems with conflicting individual rights at the core of liberalism. As a full-standing alternative to liberalism, communitarianism might have little to recommend it. But it was a spur for liberal philosophers to think about how communities could be built and sustained to support the more familiar projects of liberal politics (e.g., Strike 2010). Furthermore, its arguments often converged with those advanced by feminist exponents of the ethic of care (Noddings 1984; Gilligan 1982). Noddings’ work is particularly notable because she inferred a cogent and radical agenda for the reform of schools from her conception of care (Noddings 1992).

One persistent controversy in citizenship theory has been about whether patriotism is correctly deemed a virtue, given our obligations to those who are not our fellow citizens in an increasingly interdependent world and the sordid history of xenophobia with which modern nation states are associated. The controversy is partly about what we should teach in our schools and is commonly discussed by philosophers in that context (Galston 1991; Ben-Porath 2006; Callan 2006; Miller 2007; Curren & Dorn 2018). The controversy is related to a deeper and more pervasive question about how morally or intellectually taxing the best conception of our citizenship should be. The more taxing it is, the more constraining its derivative conception of civic education will be. Contemporary political philosophers offer divergent arguments about these matters. For example, Gutmann and Thompson claim that citizens of diverse democracies need to “understand the diverse ways of life of their fellow citizens” (Gutmann & Thompson 1996: 66). The need arises from the obligation of reciprocity which they (like Rawls) believe to be integral to citizenship. Because I must seek to cooperate with others politically on terms that make sense from their moral perspective as well as my own, I must be ready to enter that perspective imaginatively so as to grasp its distinctive content. Many such perspectives prosper in liberal democracies, and so the task of reciprocal understanding is necessarily onerous. Still, our actions qua deliberative citizen must be grounded in such reciprocity if political cooperation on terms acceptable to us as (diversely) morally motivated citizens is to be possible at all. This is tantamount to an imperative to think autonomously inside the role of citizen because I cannot close-mindedly resist critical consideration of moral views alien to my own without flouting my responsibilities as a deliberative citizen.

Civic education does not exhaust the domain of moral education, even though the more robust conceptions of equal citizenship have far-reaching implications for just relations in civil society and the family. The study of moral education has traditionally taken its bearings from normative ethics rather than political philosophy, and this is largely true of work undertaken in recent decades. The major development here has been the revival of virtue ethics as an alternative to the deontological and consequentialist theories that dominated discussion for much of the twentieth century.

The defining idea of virtue ethics is that our criterion of moral right and wrong must derive from a conception of how the ideally virtuous agent would distinguish between the two. Virtue ethics is thus an alternative to both consequentialism and deontology which locate the relevant criterion in producing good consequences or meeting the requirements of moral duty respectively. The debate about the comparative merits of these theories is not resolved, but from an educational perspective that may be less important than it has sometimes seemed to antagonists in the debate. To be sure, adjudicating between rival theories in normative ethics might shed light on how best to construe the process of moral education, and philosophical reflection on the process might help us to adjudicate between the theories. There has been extensive work on habituation and virtue, largely inspired by Aristotle (Burnyeat 1980; Peters 1981). But whether this does anything to establish the superiority of virtue ethics over its competitors is far from obvious. Other aspects of moral education—in particular, the paired processes of role-modelling and identification—deserve much more scrutiny than they have received (Audi 2017; Kristjánsson 2015, 2017).

Related to the issues concerning the aims and functions of education and schooling rehearsed above are those involving the specifically epistemic aims of education and attendant issues treated by social and virtue epistemologists. (The papers collected in Kotzee 2013 and Baehr 2016 highlight the current and growing interactions among social epistemologists, virtue epistemologists, and philosophers of education.)

There is, first, a lively debate concerning putative epistemic aims. Alvin Goldman argues that truth (or knowledge understood in the “weak” sense of true belief) is the fundamental epistemic aim of education (Goldman 1999). Others, including the majority of historically significant philosophers of education, hold that critical thinking or rationality and rational belief (or knowledge in the “strong” sense that includes justification) is the basic epistemic educational aim (Bailin & Siegel 2003; Scheffler 1965, 1973 [1989]; Siegel 1988, 1997, 2005, 2017). Catherine Z. Elgin (1999a,b) and Duncan Pritchard (2013, 2016; Carter & Pritchard 2017) have independently urged that understanding is the basic aim. Pritchard’s view combines understanding with intellectual virtue ; Jason Baehr (2011) systematically defends the fostering of the intellectual virtues as the fundamental epistemic aim of education. This cluster of views continues to engender ongoing discussion and debate. (Its complex literature is collected in Carter and Kotzee 2015, summarized in Siegel 2018, and helpfully analyzed in Watson 2016.)