8 David Foster Wallace Essays You Can Read Online

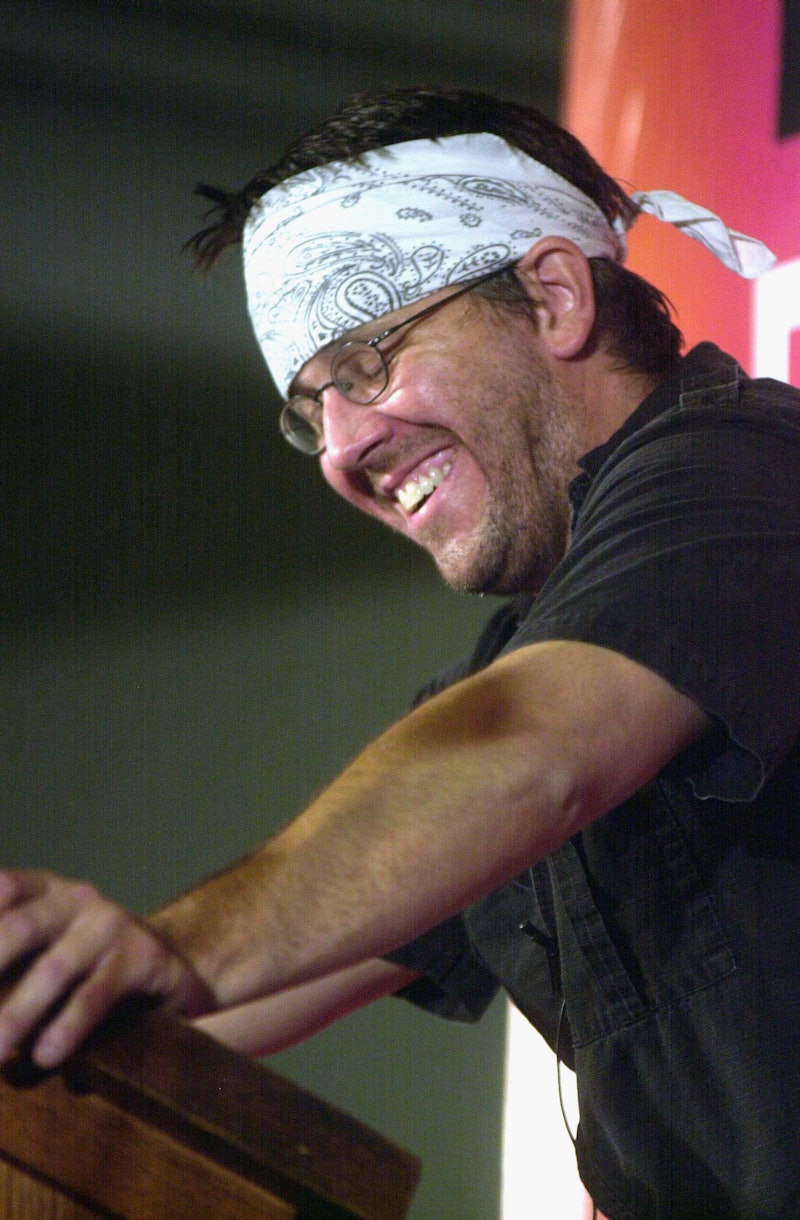

If you've talked to me for more than five minutes, you probably know that I'm a huge fan of author and essayist David Foster Wallace . In my opinion, he's one of the most fascinating writers and thinkers that has ever lived, and he possessed an almost supernatural ability to articulate the human experience.

Listen, you don't have to be a pretentious white dude to fall for DFW. I know that stigma is out there, but it's just not true. David Foster Wallace's writing will appeal to anyone who likes to think deeply about the human experience. He really likes to dig into the meat of a moment — from describing state fair roller coaster rides to examining the mind of a detoxing addict. His explorations of the human consciousness are incredibly astute, and I've always felt as thought DFW was actually mapping out my own consciousness.

Contrary to what some may think, the way to become a DFW fan is not to immediately read Infinite Jest . I love Infinite Jest. It's one of my favorite books of all-time. But it is also over 1,000 pages long and extremely difficult to read. It took me seven months to read it for the first time. That's a lot to ask of yourself as a reader.

My recommendation is to start with David Foster Wallace's essays . They are pure gold. I discovered DFW when I was in college, and I would spend hours skiving off my homework to read anything I could get my hands on. Most of what I read I got for free on the Internet.

So, here's your guide to David Foster Wallace on the web. Once you've blown through these, pick up a copy of Consider the Lobster or A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again .

1. "This is Water" Commencement Speech

Technically this is a speech, but it will seriously revolutionize the way you think about the world and how you interact with it. You can listen to Wallace deliver it at Kenyon College , or you can read this transcript . Or, hey, do both.

2. "Consider the Lobster"

This is a classic. When he goes to the Maine Lobster Festival to do a report for Gourmet , DFW ends up taking his readers along for a deep, cerebral ride. Asking questions like "Do lobsters feel pain?" Wallace turns the whole celebration into a profound breakdown on the meaning of consciousness. (Don't forget to read the footnotes!)

2. "Ticket to the Fair"

Another episode of Wallace turning journalism into something more. Harper 's sent DFW to report on the state fair, and he emerged with this masterpiece. The Harper's subtitle says it all: "Wherein our reporter gorges himself on corn dogs, gapes at terrifying rides, savors the odor of pigs, exchanges unpleasantries with tattooed carnies, and admires the loveliness of cows."

3. "Federer as Religious Experience"

DFW was obviously obsessed with tennis, but you don't have to like or know anything about the sport to be drawn in by his writing. In this essay, originally published in the sports section of The New York Times , Wallace delivers a profile on Roger Federer that soon turns into a discussion of beauty with regard to athleticism. It's hypnotizing to read.

4. "Shipping Out: On the (nearly lethal) comforts of a luxury cruise"

Later published as "A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again" in the collection of the same name, this essay is the result of Harper's sending Wallace on a luxury cruise. Wallace describes how the cruise sends him into a depressive spiral, detailing the oddities that make up the strange atmosphere of an environment designed for ultimate "fun."

5. "E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction"

This is definitely in the running for my favorite DFW essay. (It's so hard to choose.) Fiction writers! Television! Voyeurism! Loneliness! Basically everything I love comes together in this piece as Wallace dives into a deep exploration of how humans find ways to look at each other. Though it's a little long, it's endlessly fascinating.

6. "String Theory"

"You are invited to try to imagine what it would be like to be among the hundred best in the world at something. At anything. I have tried to imagine; it's hard."

Originally published in Esquire , this article takes you deep into the intricate world of professional tennis. Wallace uses tennis (and specifically tennis player Michael Joyce) as a vehicle to explore the ideas of success, identity, and what it means to be a professional athlete.

7. "9/11: The View from the Midwest"

Written in the days following 9/11, this article details DFW and his community's struggle to come to terms with the attack.

8. "Tense Present: Democracy, English, and the Wars Over Usage "

If you're a language nerd like me, you'll really dig this one. A self-proclaimed "snoot" about grammar, Wallace dives into the world of dictionaries, exploring all of the implications of how language is used, how we understand and define grammar, and how the "Democratic Spirit" fits into the tumultuous realms of English.

Images: cocoparisienne /Pixabay; werner22brigette /Pixabay; StartupStockPhotos /Pixabay; PublicDomainPIctures /Pixabay

Biblioklept

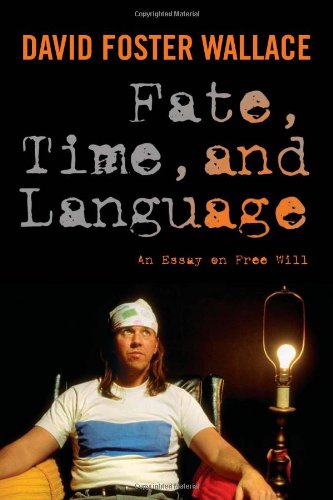

Fate, Time, and Language: An Essay on Free Will — David Foster Wallace

Sometime last year, during a rare visit to a big chain bookstore, I was disgusted to see what had happened to David Foster Wallace’s amazing Kenyon College commencement speech, “This Is Water.” Wallace’s speech, about 3,815 words, give or take (maybe twelve standard typed pages), was being sold as a 144 page hardback volume with only a sentence or two printed per page. The book was (and is) a nakedly commercial attempt to turn a text that is widely available on the web into the sort of thing that well-meaning uncles give to their nephews or nieces as graduation gifts. Of course, hardcore Wallace fans might want such a book — and I’d never begrudge them that — but it’s hard to imagine that Wallace would have been comfortable with how his book was marketed.

Which brings us to Fate, Time, and Language: An Essay on Free Will , new from Columbia University Press this week. The book publishes the 1985 honors thesis that Wallace submitted to the Amherst College’s Department of Philosophy, “Richard Taylor’s ‘Fatalism’ and the Semantics of Physical Modality.” The essay’s title alone signals a prohibitive level of academic specialization. In his introductory essay to the volume, “A Head That Throbbed Heartlike,” New York Times Magazine editor James Ryerson points out, “Its obscurity is easy to appreciate. A highly specialized, seventy-six page work of logic, semantics, and metaphysics, it is not for the philosophically faint of heart.” Ryerson then warns his reader to “Brace yourself for a sample sentence,” before offering a sample from Wallace’s essay that I do not have the patience or fortitude to type out (it would take me too long to locate all the diacritical marks and special logic symbols). Ryerson concludes the paragraph with this wry remark: “There are reasons that he’s better known for an essay about a cruise ship.”

Fortunately, the editors of Fate, Time, and Language make every effort to contextualize Wallace’s essay in a way that explains its aims, strengths, and even shortcomings. There’s Ryerson’s lengthy introduction, which provides an overview to Wallace’s life in philosophy. Then there’s Taylor’s “Fatalism” of course, a short, provocative argument combining six presuppositions that led Taylor to declare that humans have no control — none, whatsoever — over any future event. The volume collects four other essays by Taylor on fatalism, as well as eight other essays responding to his arguments, before delivering Wallace’s essay (the longest in the collection). Here’s Wallace—

So Taylor’s central claim, the Taylor problem, is that just a few basic logical and semantic presuppositions, regarded as uncontroversially true by most philosophers, lead directly to the metaphysical conclusion that human beings, agents, have no control over what is going to happen.

I ain’t even gonna front–pretty much everything that Wallace says after this was lost on me; if you want to read and comprehend the details of his argument you will need to have a grasp on the basics of Montague grammar and tensed modal logic. If you lack these skills, there will be skimming . Lots and lots of skimming. So, in short, I have no ideawhether Wallace’s logic is sound, although I find his conclusion (minus all the modal evidence) quite compelling—

This essay’s semantic analysis has shown that Taylor’s proof doesn’t “force” fatalism on us at all. We should now recall that Taylor was offering a very curious sort of argument: a semantic argument for a metaphysical conclusion. In light of what we’ve seen about the semantics of physical modality, I hold that Taylor’s semantic argument does not in fact yield his metaphysical conclusion.

After Wallace’s honors thesis, there’s a wonderful little memoir essay by his adviser on the project, Jay L. Garfield, who offers up this nugget—

I knew at the time, as I mention above, that David was also writing a novel as a thesis in English. But I never took that seriously. I though of David as a very talented young philosopher with a writing hobby, and did not realize that he was instead one of the most talented fiction writers of his generation who had a philosophy hobby.

These little pockets of insight appeal to me most in Fate, Time, and Language , and as such, Ryerson’s essay “A Head That Throbbed Heartlike” is the highpoint of the book. It weaves together Wallace’s personal life, writing career, and academic pursuits into a moving elegy of sorts, although one more rooted in ideas than feelings. He also spells out the book’s mission quite clearly—

For all its seeming inscrutability, though, the thesis is lucidly argued and–with some patience and industry on the part of the lay reader–ultimately accessible, which is welcome news for those looking to deepen their understanding of Wallace. The paper offers a point of entry into an overlooked aspect of his intellectual life: a serious early engagement with philosophy that would play a lasting role in his work and thought, including his ideas about the purpose and possibilities of fiction.

Many of us might shudder at the idea of our college essays being published posthumously. Of course, most of us aren’t Wallace, but there are undoubtedly critics out there who will cry foul at this publication. Fortunately, the team behind Fate, Time, and Language has produced a book of remarkable integrity, one that understands why it exists, readily acknowledges its obscurity without trying to gloss over that obscurity, and makes every effort to communicate with and engage its readers without sacrificing erudition. To return to my opening anecdote, this is not the naked commercialism that motivated a gimmicky edition This Is Water ; rather, this is a book delivered by people who genuinely care about Wallace and his ideas. Make no mistake–it’s very dry and very specialized, but fanatics will no doubt want it.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Published by Edwin Turner

View all posts by Edwin Turner

6 thoughts on “Fate, Time, and Language: An Essay on Free Will — David Foster Wallace”

[…] 1. After reading Tom McCarthy’s front-page review of two works by the late David Foster Wallace, Wallace’s unfinished novel, The Pale King, and Wallace’s essay Fate, Time, and Language: […]

Thanks for finally writing about >Fate, Time, and Language: An Essay on Free Will – David Foster Wallace | biblioklept <Liked it!

[…] Wallace’s adviser on the project, Jay L. Garfield, later stated: […]

[…] Wallace’s adviser on the project, Jay L. Garfield, later stated: […]

[…] Wallace’s adviser on the project, Jay L. Garfield, later stated: […]

[…] Applying the principle of bivalence (i.e. statements identified as either true or false), Taylor identified six presuppositions that appeared to prove individual powerlessness in the face of inevitable outcomes; and David Foster Wallace’s rebuttal came in the form of his 1985 honors thesis at Amherst College, entitled: “Fate, Time, and Language: An Essay on Free Will”. […]

Your thoughts? Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Advertisement

Supported by

‘Fate, Time, and Language’

- Share full article

To the Editor:

In his superb and highly sophisticated review of David Foster Wallace’s unfinished novel, “The Pale King” (April 17), Tom McCarthy stops to take a look at the publication of “Fate, Time, and Language” — Wallace’s undergraduate philosophy thesis, along with commentary by other authors — about the seminal and controversial 1962 essay “Fatalism,” by the philosopher Richard Taylor. In that essay, based on a set of at least seemingly persuasive logical axioms, Taylor (as have many before him) argued that, logically speaking, the future is essentially as set in stone as the past. McCarthy writes, “That the assertion is ridiculous isn’t the issue” — begging the question right off the bat, it seems to me. Whether it is ridiculous or not is precisely the issue that Wallace and Taylor discuss seriously and disagree seriously about. McCarthy summarizes what he considers the refutation of Taylor’s position, more or less as argued by Wallace’s thesis: “Taylor has assumed a single-lined, inevitable flow from past to future — whereas, even considered logically, each point in this progression in fact splits, along the lines of possibility, into divergent strands.” Along the lines of possibility, yes. Each point contains lots of possibilities, but only one of those possibilities actually occurs. There is no real-world “split,” unless perhaps in the recently posited alternate universes that surround us, such as the one in which I decided not to write this letter — one that may seem pretty appealing if the reader has gotten this far. Only one thing happens here.

Wallace’s novel and essay and McCarthy’s review are excellent demonstrations that the issues of will and choice and agency are, in our era of neurobiological investigations, not sterile and abstract. They are descending from the lofty and, yes, sometimes ridiculous heights of philosophy into the real world of human moral, social, jurisprudential and political actions. (See Daniel Wegner’s wonderful book “The Illusion of Conscious Will,” published a few years ago.) Did you know that if I hold a gun to your head — no, no, a pie to your face — the motor command to mush it there precedes my consciousness of the decision to do so?

DANIEL MENAKER New York

As a co-editor of “Fate, Time, and Language,” I want to clarify a matter obscured in Tom McCarthy’s review: David Foster Wallace wrote no work with this title. His senior thesis at Amherst College was titled “Richard Taylor’s ‘Fatalism’ and the Semantics of Physical Modality.” The book McCarthy reviewed includes Taylor’s original essay, criticisms of it that appeared in leading philosophical journals, Taylor’s replies to his critics, Wallace’s monograph and a related article by Taylor that sheds further light on his views.

Contrary to McCarthy’s claim, Columbia University Press did not publish Wallace’s thesis as a “kind of tie-in” to “The Pale King.” The publication is justified not by Wallace’s later literary accomplishments but by the high quality of his philosophical thinking. The issues he explores were not created, as McCarthy suggests, in the world of “analytical philosophy,” but extend back to Aristotle. They do not concern, as McCarthy unsympathetically puts it, “bean-counting,” but whether statements about our future actions are already true or false, a controversy that has its theological counterpart in the age-old conundrum of whether God’s omniscience is compatible with free will.

McCarthy seems uninterested in such issues, but Wallace found them fascinating, and the detailed analysis he offered will surely be required reading by those who henceforth undertake a serious study of the knotty problem of fatalism.

STEVEN M. CAHN Old Greenwich, Conn. The writer is a professor of philosophy at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

What can fiction tell us about the apocalypse? The writer Ayana Mathis finds unexpected hope in novels of crisis by Ling Ma, Jenny Offill and Jesmyn Ward .

At 28, the poet Tayi Tibble has been hailed as the funny, fresh and immensely skilled voice of a generation in Māori writing .

Amid a surge in book bans, the most challenged books in the United States in 2023 continued to focus on the experiences of L.G.B.T.Q. people or explore themes of race.

Stephen King, who has dominated horror fiction for decades , published his first novel, “Carrie,” in 1974. Margaret Atwood explains the book’s enduring appeal .

Do you want to be a better reader? Here’s some helpful advice to show you how to get the most out of your literary endeavor .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

David Foster Wallace on Writing, Self-Improvement, and How We Become Who We Are

By maria popova.

In late 1999, David Foster Wallace (February 21, 1962–September 12, 2008) — poignant contemplator of death and redemption , tragic prophet of the meaning of life , champion of intelligent entertainment , admonisher against blind ambition , advocate of true leadership — called the office of the prolific writer-about-writing Bryan A. Garner and, declining to be put through to Garner himself, grilled his secretary about her boss. Wallace was working on an extensive essay about Garner’s work and his newly released Dictionary of Modern American Usage . A few weeks later, Garner received a hefty package in the mail — the manuscript of Wallace’s essay, titled “Tense Present,” which was famously rejected by The New Republic and The New York Review of Books , then finally published by Harper’s and included in the 2005 anthology Consider the Lobster and Other Essays . Garner later wrote of the review, “a long, laudatory piece”: “It changed my literary life in ways that a book review rarely can.”

Over the course of the exchange, the two struck up a friendship and began an ongoing correspondence, culminating in Garner’s extensive interview with Wallace, conducted on February 3, 2006, in Los Angeles — the kind of conversation that reveals as much about its subject matter, in this case writing and language, as it does about the inner workings of its subject’s psyche. Five years after Wallace’s death, their conversation was published in Quack This Way: David Foster Wallace & Bryan A. Garner Talk Language and Writing ( public library ).

Wallace begins at the beginning, responding to Garner’s request to define good writing:

In the broadest possible sense, writing well means to communicate clearly and interestingly and in a way that feels alive to the reader. Where there’s some kind of relationship between the writer and the reader — even though it’s mediated by a kind of text — there’s an electricity about it.

Wallace, who by the time of the interview had fifteen years of teaching writing and literature under his belt, considers how one might learn this delicate craft:

In my experience with students—talented students of writing — the most important thing for them to remember is that someone who is not them and cannot read their mind is going to have to read this. In order to write effectively, you don’t pretend it’s a letter to some individual you know, but you never forget that what you’re engaged in is a communication to another human being. The bromide associated with this is that the reader cannot read your mind. The reader cannot read your mind . That would be the biggest one. Probably the second biggest one is learning to pay attention in different ways. Not just reading a lot, but paying attention to the way the sentences are put together, the clauses are joined, the way the sentences go to make up a paragraph.

This act of paying attention, Wallace argues, is a matter of slowing oneself down. Echoing Mary Gordon’s case for writing by hand , he tells Garner:

The writing writing that I do is longhand. . . . The first two or three drafts are always longhand. . . . I can type very much faster than I can write. And writing makes me slow down in a way that helps me pay attention.

In a sentiment that brings to mind Susan Sontag’s beautiful Letter to Borges , in which she defines writing as an act of self-transcendence, Wallace argues for the craft as an antidote to selfishness and self-involvement, and at the same time a springboard for self-improvement:

One of the things that’s good about writing and practicing writing is it’s a great remedy for my natural self-involvement and self-centeredness. . . . When students snap to the fact that there’s such a thing as a really bad writer, a pretty good writer, a great writer — when they start wanting to get better — they start realizing that really learning how to write effectively is, in fact, probably more of a matter of spirit than it is of intellect. I think probably even of verbal facility. And the spirit means I never forget there’s someone on the end of the line, that I owe that person certain allegiances, that I’m sending that person all kinds of messages, only some of which have to do with the actual content of what it is I’m trying to say.

Wallace argues that one of the most important points of awareness, and one of the most shocking to aspiring writers, can be summed up thusly:

“I am not, in and of myself, interesting to a reader. If I want to seem interesting, work has to be done in order to make myself interesting.”

(Vonnegut only compounded the terror when he memorably admonished , “The most damning revelation you can make about yourself is that you do not know what is interesting and what is not.” )

Wallace weighs the question of talent, erring on the side of grit as the quality that sets successful writers apart:

There’s a certain amount of stuff about writing that’s like music or math or certain kinds of sports. Some people really have a knack for this. . . . One of the exciting things about teaching college is you see a couple of them every semester. They’re not always the best writers in the room because the other part of it is it takes a heck of a lot of practice. Gifted, really really gifted writers pick stuff up quicker, but they also usually have a great deal more ego invested in what they write and tend to be more difficult to teach. . . . Good writing isn’t a science. It’s an art, and the horizon is infinite. You can always get better.

Despite the prevalence of mindless language usage , Wallace — not one to miss an opportunity to poke some fun at then-President George Bush — makes a case for a yang to the yin of E.B. White’s assertion that the writer’s responsibility is “to lift people up, not lower them down,” arguing that part of that responsibility is also having faith in the reader’s capacities and sensitivities:

Regardless of whom you’re writing for or what you think about the current debased state of the English language, right? — in which the President says things that would embarrass a junior-high-school student — the fact remains that … the average person you’re writing for is an acute, sensitive, attentive, sophisticated reader who will appreciate adroitness, precision, economy, and clarity. Not always, but I think the vast majority of the time.

Learning to write well, with elegance and sensitivity, shouldn’t be reserved for those trying to have a formal career in writing — it also, Wallace points out, immunizes us against the laziness of clichés and vogue expressions :

A vogue word … becomes trendy because a great deal of listening, talking, and writing for many people takes place below the level of consciousness. It happens very fast. They don’t pay it very much attention, and they’ve heard it a lot. It kind of enters into the nervous system. They get the idea, without it ever being conscious, that this is the good, current, credible way to say this, and they spout it back. And for people outside, say, the corporate business world or the advertising world, it becomes very easy to make fun of this kind of stuff. But in fact, probably if we look carefully at ourselves and the way we’re constantly learning language . . . a lot of us are very sloppy in the way that we use language. And another advantage of learning to write better, whether or not you want to do it for a living, is that it makes you pay more attention to this stuff. The downside is stuff begins bugging you that didn’t bug you before. If you’re in the express lane and it says, “10 Items or Less,” you will be bugged because less is actually inferior to fewer for items that are countable. So you can end up being bugged a lot of the time. But it is still, I think, well worth paying attention. And it does help, I think . . . the more attention one pays, the more one is immune to the worst excesses of vogue words, slang, you know. Which really I think on some level for a lot of listeners or readers, if you use a whole lot of it, you just kind of look like a sheep—somebody who isn’t thinking, but is parroting.

He returns to the question of good writing and the deliberate practice it takes to master:

Writing well in the sense of writing something interesting and urgent and alive, that actually has calories in it for the reader — the reader walks away having benefited from the 45 minutes she put into reading the thing — maybe isn’t hard for a certain few. I mean, maybe John Updike’s first drafts are these incredible . . . Apparently Bertrand Russell could just simply sit down and do this. I don’t know anyone who can do that. For me, the cliché that “Writing that appears effortless takes the most work” has been borne out through very unpleasant experience.

In a sentiment that Anne Lamott memorably made, urging that perfectionism is the great enemy of creativity , and Neil Gaiman subsequently echoed in his 8 rules of writing , where he asserted that “perfection is like chasing the horizon,” Wallace adds:

Like any art, probably, the more experience you have with it, the more the horizon of what being really good is . . . the more it recedes. . . . Which you could say is an important part of my education as a writer. If I’m not aware of some deficits, I’m not going to be working hard to try to overcome them. . . . Like any kind of infinitely rich art, or any infinitely rich medium, like language, the possibilities for improvement are infinite and so are the possibilities for screwing up and ceasing to be good in the ways you want to be good.

Reflecting on the writers he sees as “models of incredibly clear, beautiful, alive, urgent, crackling-with-voltage prose” — he lists William Gass, Don DeLillo, Cynthia Ozick, Louise Erdrich, and Cormac McCarthy — Wallace makes a beautiful case for the gift of encountering, of arriving in the work of that rare writer who not only shares one’s sensibility but also offers an almost spiritual resonance. (For me, those writers include Rebecca Solnit , Dani Shapiro , Susan Sontag , Carl Sagan , E.B White , Anne Lamott , Virginia Woolf .) Wallace puts it elegantly:

If you spend enough time reading or writing, you find a voice, but you also find certain tastes. You find certain writers who when they write, it makes your own brain voice like a tuning fork, and you just resonate with them. And when that happens, reading those writers … becomes a source of unbelievable joy. It’s like eating candy for the soul. And I sometimes have a hard time understanding how people who don’t have that in their lives make it through the day.

Echoing Kandinsky’s thoughts on the spiritual element in art , he adds:

Lucky people develop a relationship with a certain kind of art that becomes spiritual, almost religious, and doesn’t mean, you know, church stuff, but it means you’re just never the same.

But perhaps his most important point is that the act of finding our purpose and finding ourselves is not an A-to-B journey but a dynamic act, one predicated on continually, cyclically getting lost — something we so often, and with such spiritually toxic consequences, forget in a culture where the first thing we ask a stranger is “So, what do you do?” Wallace tells Garner:

I don’t think there’s a person alive who doesn’t have certain passions. I think if you’re lucky, either by genetics or you just get a really good education, you find things that become passions that are just really rich and really good and really joyful, as opposed to the passion being, you know, getting drunk and watching football. Which has its appeals, right? But it is not the sort of calories that get you through your 20s, and then your 30s, and then your 40s, and, “Ooh, here comes death,” you know, the big stuff. . . . It’s also true that we go through cycles. . . . These are actually good — one’s being larval. . . . But I think the hard thing to distinguish among my friends is who . . . who’s the 45-year-old who doesn’t know what she likes or what she wants to do? Is she immature? Or is she somebody who’s getting reborn over and over and over again? In a way, that’s rather cool.

Quack This Way is excellent in its entirety, brimming with the very spiritual resonance discussed above. Complement it with this compendium of famous writers’ wisdom on the craft , including Kurt Vonnegut ’s 8 rules for writing with style , Henry Miller ’s 11 commandments , Susan Sontag ’s synthesized wisdom , Chinua Achebe on the writer’s responsibility , Nietzsche ’s 10 rules for writers , and Jeanette Winterson on reading and writing .

— Published August 11, 2014 — https://www.themarginalian.org/2014/08/11/david-foster-wallace-quack-this-way/ —

www.themarginalian.org

PRINT ARTICLE

Email article, filed under, art books creativity culture david foster wallace interview writing, view full site.

The Marginalian participates in the Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate programs, designed to provide a means for sites to earn commissions by linking to books. In more human terms, this means that whenever you buy a book from a link here, I receive a small percentage of its price, which goes straight back into my own colossal biblioexpenses. Privacy policy . (TLDR: You're safe — there are no nefarious "third parties" lurking on my watch or shedding crumbs of the "cookies" the rest of the internet uses.)

Book Review , Books , reviews

Lessons in Language from David Foster Wallace and Bryan Garner: A Review of “Quack This Way”

Quack this Way: David Foster Wallace and Bryan A. Garner Talk Language and Writing by Brian Andrew Garner Penrose; 146 p.

By the looks of it, the book, Quack this Way: David Foster Wallace and Bryan A. Garner Talk Language and Writing , a new offering from the DFW legacy should serve as a footnote, at best, on the acclaimed author’s life. In 2001, The New Republic commissioned a book review from Wallace on Bryan Garner’s then little-known book on modern American usage. As with all of his nonfiction, Wallace turned into it a monster, taking a 3000 word assignment and turning it into a 100-page adventure into the political, philosophical and linguistic background to a battle brewing for the heart of the English language and identity. The essay, finally printed at less than half the original length, landed in Harper’s under the title “Tense Present” to widespread acclaim. It was then published in full as the centerpiece of Consider the Lobster. After Wallace wrote the essay, it changed Garner’s literary life, and consequently, they became friends, which culminated in a 67-minute-long interview between the two. (Which is now published in the form of this book.) Here, in this interview, Garner and Wallace speak at length about writing, the uses of language and grammar. Yet, despite its slight appearance and unedited style, this interview is a lost gem, one of the more interesting, insightful and undiluted look into Wallace’s mind and opinions about writing, other people, and communication.

There are many great and now legendary DFW interviews, but three published in his lifetime standout. Laura Miller, for Salon, found Wallace at the pitch of his voice-of-a generation shtick , and while it’s a great interview, you can feel the artifice of it all. The literary theorist, Larry McCaffery , engaged Wallace in a highly intellectual conversation that provides the perfect addendum to Wallace’s essay on TV, but again, you not only feel the artifice, but you can feel Wallace’s insecurity throughout, his uncertainty when he can and cannot be smart. Later in life, Wallace gave a lesser known, but insightful, honest video interview to a German TV station in which he worries about the future of America. However, again, even in this older stage interview, you can feel him balk at the implicit hero worship the interviewer was sending his way. Posthumously, David Lipsky’s interview, published in a full length book, while interesting, and while it tries for a home run on every swing, ultimately feels flat and parasitic. All of these interviews display the strange aggressive dance that Wallace felt necessary to engage in between himself and the interviewer. The interviews often end up less about a specific topic and more about the dynamics between the two human beings.

But here, given the curious nature of their relationship and friendship (Wallace sought out a relationship with Garner), many of those more self-conscious and artificial elements are gone, or well hidden. This needs some explanation. You can tell that Wallace respected Garner, even felt a little awe and perhaps jealousy towards his talents, talents that so contrasted to the talents of Wallace. Not only does Wallace treat and allow himself to be treated by Garner as an equal but you get the distinct feeling that Wallace and Garner understood that they came from different social circles, even cliques, and Wallace therefore felt considerably less worried about worrying about his desire to look cool. Both of these factors, and perhaps the relative age and maturity of Wallace allow to talk largely without as many qualifications, or reservations, or diversions from his actual intelligence. We all know that friend that belongs in a different social circle so you could speak more honestly with them, and for Wallace, Garner was that friend.

Consequently, he never appears to feel threatened; he doesn’t believe that Garner wants something from him more than friendship, more than a discussion of a shared passionate love: language, grammar, and the uses and abuses of our greatest tool of communication. For writers, this will stand as an invaluable conversation between two great, but very different types of writers. Garner serves as that brilliant but often frustrating English teacher who stubbornly insists on traditional notions of grammar, of etiquette, and the canon, unabashedly. He believes in right and wrong usage and an often linear notion of tradition. Wallace, as you would expect, feels considerably more ambivalent about these questions than Garner and that’s what works so well. Time and again, you will see this throughout the interview. Garner will make some pointed, though somewhat simplistic statement about people, about language that comes off as traditional and conservative, privileged in his male-white-status. Wallace will consequently evince some cringeworthy discomfort at Garner’s simplicity or evident dislike of certain people and Wallace will then soften the blow. You can see the gears of his brain working unfettered, navigating his evident enjoyment of this person with his inclination towards empathy and complexity, his elitism with humane desire to help other people, to understand even the most annoying of people as endlessly worthy of empathy.

Of course, this being a David Foster Wallace interview, an unedited one at that, we receive some gems and experience the frustration in a brain that just won’t stop, ever. Numerous times, Wallace worries that he needs to constantly sharpen his statements, and numerous times he notes that this will likely be cut, and should be cut because he didn’t say it right. This tic is at turns endearing and frustrating, but ultimately a nice conduit into what it felt like to think as Wallace. For him, all statements required essays given the complexity of simple words.

Given the perceived equality in the friendship, Wallace feels at relative ease and at home in making considerably more drastic statements than we normally see from his more polished and edited work. His intense diatribes against President Bush are way overdue and only hinted at in other interviews. His takedowns of pretentious people are filled with more barbs than usual, and his discussions about the strengths and weaknesses of his writing is some of the most honest I’ve ever read from him. He doesn’t speak openly only out of rage, but out of generosity as well. allow. His discussion of the often horrendous and annoying writing of academia is more balanced than the explanation of pretentiousness Wallace himself once ascribed to:

There’s the kind of boneheaded explanation, which is that a lot of people with PhDs are stupid, and like many stupid people, they associate complexity with intelligence. And therefore they get brainwashed into making their stuff more complicated than it needs to be. I think the smarter thing to say is that in many tight, insular communities— where membership is partly based on intelligence, proficiency, and being able to speak the language of the discipline— pieces of writing become as much or more about presenting one’s own qualifications for inclusion in the group than transmission of meaning.

There’s an evident maturity in the way he talks, what he thinks about, and how he communicates, a greater sense of control, direction and purpose, than in the earlier interview. A lot of this comes from Garner, a person, unlike many other interviewers, who did not cower before Wallace. Garner treats them both like peers, and doesn’t mind pushing Wallace for clarity or for clarification. When Wallace is clear he’s as good as he’s ever been in an interview:

If you spend enough time reading or writing, you find a voice, but you also find certain tastes. You find certain writers who when they write, it makes your own brain voice like a tuning fork, and you just resonate with them. And when that happens, reading those writers— not all of whom are modern . . . I mean, if you are willing to make allowances for the way English has changed, you can go way, way back with this— becomes a source of unbelievable joy. It’s like eating candy for the soul.

For the general populace — apathetic to grammar, writing and Wallace — this book still retains its importance as a very contemporary understanding of the way we use language and the effects thereof. Wallace opines pointedly, on how advertising affects us, insinuating its often twisted and powerful jargon into our minds, and colors the way we think and interact. From there, with ease, he shifts to discuss the nature of officalese, something like the phrase “how can we be of assistance” that is unnecessarily wordy and full of strange constructions, as purposefully cold and distant. He finishes with discussing the nature of political rhetoric, or what it means/meant to have a president who could clearly not speak well in public but still chose to embrace that simplicity when he could clearly just rely instead on well-spoken advisers. Wallace forces and teaches us how to think deeply and purposefully about how and why and when we use language. In his answers, and his devotion to language, to communication, he models a responsibility and devotion towards the real power of language.

Some of the joy of the interview and introduction comes from the unknown little tidbits about Wallace. For instance, Garner set up a date between the Scalias and the Wallaces, to which Wallace, after the dinner the couples had together, left this message with Garner:

This is David Wallace. I’m a friend of Mr. Garner’s — I really am. You can ask him. Anyway, I just wanted to thank him for arranging the introduction with Justice Scalia and to say hello. I don’t know who’s going to get this message, but it’s for real. I really am a friend of Bryan Garner. Again, it’s David Wallace. Thanks.

As with all of this emerging lost interviews and essays, they tend to engender a sense of sadness, of all the potential essays and writings from DFW that will remain forever lost. His shock at Bush stands in stark contrast to the rhetorical eloquence of Obama, a topic that apparently Wallace wanted to write about before his suicide. He describes a book he would love to read or help write about the countless distinct uses of English in America and how it reflects and creates distinct American experiences and you can’t help but sigh, but the honesty of this interview helps.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter , Facebook , Google + , our Tumblr , and sign up for our mailing list .

Site Content

Fate, time, and language.

An Essay on Free Will

David Foster Wallace. Edited by Steven M. Cahn and Maureen Eckert. Introduction by James Ryerson and epilogue by Jay Garfield

Columbia University Press

Pub Date: December 2010

ISBN: 9780231151573

Format: Paperback

List Price: $19.95 £16.99

Shipping Options

Purchasing options are not available in this country.

ISBN: 9780231151566

Format: Hardcover

List Price: $65.00 £55.00

ISBN: 9780231527071

Format: E-book

List Price: $17.99 £14.99

- EPUB via the Columbia UP App

- PDF via the Columbia UP App

Fatalism, the sorrowful erasure of possibilities, is the philosophical problem at the heart of this book. To witness the intellectual exuberance and bravado with which the young Wallace attacks this problem, the ambition and elegance of the solution he works out so that possibility might be resurrected, is to mourn, once again, the possibilities that have been lost. Rebecca Newberger Goldstein, author of Thirty-six Arguments for the Existence of God: A Work of Fiction

As an early glimpse at the preoccupations of one of the 20th century's most compelling and philosophical authors, it is invaluable, and Wallace's conclusion... is simply elegant. Publishers Weekly

This book is for any reader who has enjoyed the works of Wallace and for philosophy students specializing in fatalism. Library Journal

[A] tough and impressive book.Financial Times Anthony Gottlieb, Financial Times

an excellent summary of Wallace's thought and writing which shows how his philosophical interests were not purely cerebral, but arose from, and fed into, his emotional and ethical concerns. Robert Potts, Times Literary Supplement

Fate, Time, and Laguage contains a great deal of first-rate philosophy throughout, and not least in Wallace's extraordinarily professional and ambitious essay.... Daniel Speak, Notre Dame Philosophical Review

Valuable and interesting. James Ley, Australian Literary Review

A philosophical argument that deserves a place in any college-level library interested in modern philosophical debate. A lively, debative tone keeps this accessible to newcomers. Midwest Book Review

- Read more of Ryerson’s introduction on Slate.

- Read a read a review from the Times Literary Supplement.

- Read Daniel Menaker’s review on Barnes & Noble Review.

- Read a review from the New York Times.

- Read an article from the Wall Street Journal

- Read a review from The Financial Times.

- A review from Biblioklept.

- Read about the book on EW’s Shelf Life.

Winner, 2011 Independent Publisher Book Award (gold medal) for Classical Studies / Philosophy

About the Author

- Analytic Philosophy

- Languages and Linguistics

- Linguistics

- Literary Studies

- U.S. Literature

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Art

- History of Art

- Theory of Art

- Browse content in History

- Environmental History

- History by Period

- Intellectual History

- Political History

- Regional and National History

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Psycholinguistics

- Browse content in Literature

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Religion

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cultural Studies

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Browse content in Law

- Criminal Law

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Palaeontology

- Environmental Science

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- History of Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Information and Communication Technologies

- Browse content in Economics

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Public Economics

- Browse content in Environment

- Climate Change

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Interdisciplinary Studies

- Browse content in Politics

- Asian Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Environmental Politics

- International Relations

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Economy

- Political Theory

- Public Policy

- Security Studies

- US Politics

- Browse content in Social Work

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Browse content in Sociology

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Sport and Leisure

- Reviews and Awards

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Freedom and the Self: Essays on the Philosophy of David Foster Wallace

- Cite Icon Cite

The book Fate, Time, and Language: An Essay on Free Will , published in 2010, presented David Foster Wallace's challenge to Richard Taylor's argument for fatalism. In this anthology, notable philosophers engage directly with that work and assess Wallace's reply to Taylor as well as other aspects of Wallace's thought. The thinkers in this book explores Wallace's philosophical and literary work, illustrating remarkable ways in which his philosophical views influenced and were influenced by themes developed in his other writings, both fictional and nonfictional. This book unlocks key components of Wallace's work and its traces in modern literature and thought.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

The Last Essay I Need to Write about David Foster Wallace

Mary k. holland on closing the “open question” of wallace’s misogyny.

Feature photo by Steve Rhodes .

David Foster Wallace’s work has long been celebrated for audaciously reorienting fiction toward empathy, sincerity, and human connection after decades of (supposedly) bleak postmodern assertions that all had become nearly impossible. Linguistically rich and structurally innovative, his work is also thematically compelling, mounting brilliant critiques of liberal humanism’s masked oppressions, the soul-killing dangers of technology and American narcissism, and the increasing impotence of our culture of irony.

Wallace spoke and wrote movingly about our need to cultivate self-awareness in order to more fully see and respect others, and created formal methods that construct the reader-writer relationship with such piercing intimacy that his fans and critics feel they know and love him. A year after his death by suicide, as popular and critical attention to him and his work began to build into the industry of Wallace studies that exists today, he was first outed as a misogynist who stalked, manipulated, and physically attacked women.

In her 2009 memoir, Lit , Mary Karr spends less than four pages narrating the several years in which Wallace pursued her, leading to a brief romantic relationship that ended in vicious arguments and “his pitching my coffee table at me.” Unlike her accounts of the relationship nearly a decade later, Karr’s tone here notably remains clever and humorous throughout. She also follows each disclosure of Wallace’s ferocity with a confession of her own regrettable behavior: regarding his “temper fits” she admits to “sentences I had to apologize for” and assures us—twice—that “no doubt he was richly provoked.” After describing the coffee-table incident, she notes parenthetically that “years later, we’ll accept each other’s longhand apologies for the whole debacle,” as if having a piece of furniture thrown at you makes you as guilty as having thrown it.

Three years later D.T. Max published his biography of Wallace, in which he divulged more shocking details about the relationship with Karr—that Wallace tried to buy a gun to kill her husband, that he tried to push her from a moving car—while also dropping enough details about Wallace’s sex life and professed attitudes toward women to make him sound like one of his own hideous men. Wallace called female fans at his readings “audience pussy”; wondered to Jonathan Franzen whether “his only purpose on earth was ‘to put my penis in as many vaginas as possible’”; picked up vulnerable women in his recovery groups; admitted to a “fetish for conquering young mothers,” like Orin in Infinite Jest ; and “affected not to care that some of the women were his students.”

In a 2016 anthology dedicated to the late author, one of those students, Suzanne Scanlon, published a short story about a student having a manipulative, emotionally abusive sexual affair with her professor (called “D-,” “Author,” and “a self-identified Misogynist”), using characteristic formal elements of “Octet” and “Brief Interviews” and dominated by the narrative voice popularized by David Foster Wallace.

None of these accounts had any visible impact on fans’ or readers’ love of Wallace’s writing or on critics’ readings and opinions of his work. Rather, one writer, Rebecca Rothfeld, confessed in 2013 that Max’s record of (some of) Wallace’s misogynistic acts and statements could not shake her “faith in [his] fundamental goodness, intelligence, and likeability” because his “work seemed more real to me than his behavior did.” Critic Amy Hungerford took the opposite stance in 2016, proclaiming her decision to stop reading and teaching Wallace’s work, but without mentioning his abusive treatment of women or the question of how that behavior presses us to re-read the same in his work.

Another writer, Deirdre Coyle, explained her discomfort at reading Wallace not in terms of the author’s own behavior—which she gives no sign of being aware of—but because of sexual and misogynistic violence perpetrated on her by men she sees as very much like Wallace (“Small liberal arts colleges are breeding grounds for these guys”) and in terms of patriarchy in general (“It’s hard to distinguish my reaction to Wallace from my reaction to patriarchy.” Any woman who has been violated, talked over, and condescended to by this kind of man, the kind who thinks his pseudo-feminism allows him to enlighten her about her own experiences of male oppression and sexual violation, cannot help but sympathize with Coyle.

But in rejecting Wallace because of other men’s sexual violence and misogyny in general, she shifts the argument away from questions about how these function in the fiction and how Wallace’s biography might force us to re-read that fiction, and allows for the kind of circular rebuttal that a (male) Wallace critic offered a year later: not all male readers of Wallace are misogynists; therefore, women should listen to the good ones and read more Wallace; let me tell you why.

These pre-#MeToo reactions to Karr’s and Max’s reports of Wallace’s abuse of women clarify what is at stake as readers, critics, and teachers consider this biographical information in the context of Wallace’s work. For, while Wimsatt and Beardsley’s argument against the intentional fallacy is compelling and important, its goal is to protect the sanctity of the text against the undue influence of our assumptions about the person who wrote it. Arguments defending the importance of Wallace’s beautiful empathizing fiction in spite of his abuse of women threaten to do the opposite.

Like Rothfeld, whose admiration for Wallace’s fiction renders his own misogynistic acts less “real,” David Hering argues that “the biographical revelation of unsavoury details about Wallace’s own relationships” leads to an equation between Wallace and misogyny that “does a fundamental disservice to the kind of urgent questions Wallace asks in his work about communication, empathy, and power”—as if Wallace’s real abuse of real women is not worth contemplating in comparison with his writing about how fictional men treat fictional women. Hering’s use of the euphemism “unsavoury” to describe behavior ranging from exploitation to physical attacks, like his description of Wallace’s work regarding gender as “troublesome,” illustrates another widespread problem with nearly all critical treatments of this topic so far: an unwillingness to say, or perhaps even see, that what we are talking about in the fiction and in the author’s life is gender-motivated violence, stalking, physical abuse, even, in the case of Karr’s husband, plotting to murder.

In the wake of the October 2017 resurgence of Burke’s #MeToo movement, we see a curious split between Wallace-studies critics and others in their reactions to these allegations. Not only does Hering’s response downplay the severity of Wallace’s behavior and its relevance to his work; it also asserts Hering’s “belief” that Wallace’s work “dramatize[s]” misogyny, rather than expressing it—without offering a text-based argument or pointing to the critical work that had already done this analysis and found exactly the opposite to be true.

He also relies on a technique used by memoirists, bloggers, and critics alike in their attempts to save Wallace from his own biography: he converts an example of male domination of women into a universal human dilemma, erasing the elements of gender and power entirely, by reading Wallace’s silencing of his female interviewer’s voice in Brief Interviews as “embody[ing] the richness of Wallace’s work—its focus on the difficulty and importance of communication and empathy, and its illustration of the poisonous things that happen when dialogue breaks down.” Such a reading ignores the fact that when dialogue breaks down between an entitled man and a pressured woman , the things that can happen go beyond metaphorically poisonous to physically sickening and injurious—as so many of the stories in that collection illustrate.

Given the same platform and the same task—celebrating Wallace around what would have been his 56th birthday—critic Clare Hayes-Brady offered “Reading David Foster Wallace in 2018,” mere months after the social media flood of women’s testimonies about sexual violence had begun. It does not mention #MeToo or the public allegations that had been made about Wallace, raising the question of what “in 2018” refers to. When asked several months later “what’s changed?” in Wallace studies, after the public (but not critical) backlash had begun, Hayes-Brady falls back on the same generalizing technique used by Hering. She reframes accusations of misogyny as an entirely academic development, beneficial to Wallace studies and unrelated to #MeToo outcry against perpetrators of sexual violence (“a coincidence of timing”). She equates “flaws in his writing both technical and also moral and ethical,” as if women had been up in arms across Twitter over Wallace’s exhausting sentence structures.

When directly asked if Wallace was a misogynist, she replies “yes, but in the way everyone is, including me,” as if we neither have nor need a separate word for men who do not just live unavoidably in our misogynistic culture but also willfully perpetrate selfish, cruel, and violent acts of misogyny against women. That is, rather than responding humanely to indisputable evidence that our beloved writer was not the saint he would have liked us to think he was (and that we would have liked to believe him to be), Wallace critics—including me, in my silence at that time—refused to allow #MeToo to force the reckoning that was so clearly required. We did so by denying the relevance of his personal behavior to his fiction and to our work, or—worse—by participating in that age-old rape culture enabler: refusing to believe women’s testimony.

Those outside literary studies reacted quite differently to the renewed attention #MeToo brought to these accusations. After Junot Díaz was publicly accused on May 4, 2018, of sexually abusing women, causing immediate public protest, Mary Karr responded by reminding us on Twitter of the abuse she had reported nearly a decade earlier, prompting a series of blog articles and interviews that supported Karr by recounting the allegations made by Karr and Max. They also began to reveal the misogyny that had shaped and stifled public reception of those allegations.

Whitney Kimball pointed out that Max described Wallace’s violent treatment of Karr as beneficial to his creative output and part of what made him “fascinating”; that in praising the “quite remarkable” “craftsmanship” of one of Wallace’s letters, Max notes only in passing that the letter is Wallace’s apology for planning to buy a gun to kill Karr’s husband. Megan Garber noted the misogyny of an interviewer asking Max why “his feelings for [Karr] created such trouble for Wallace”—an example of what Kate Manne calls “himpathy,” or empathizing with a male perpetrator of sexual violence rather than the victim.

#MeToo also began to make the misogyny of Wallace’s work more visible to his readers. Devon Price describes how reading about Wallace’s abuses against women caused them to revisit Wallace’s work and see its gender violence for the first time. Tellingly, Price also realizes that one of the reasons they were depressed when they fell in love with Wallace’s work is that they were then in a physically, emotionally, and sexually abusive relationship. Price’s realization points to another common reason why readers are blind to or defensive about the misogyny in Wallace’s work and behavior, and to a key way in which the #MeToo movement can allow reading and literary studies to illuminate misogyny in synergistic ways: we are often blind to misogyny and sexual abuse, in fiction and in others’ behavior, because we are living in it unaware. And the awareness of the spectrum of sexual abuse brought by #MeToo testimonies reveals misogyny not just in the fiction that we read, but in our own lives—one revelation causing the other.

To date, no new criticism has emerged that directly considers the implications to his work of Wallace’s now widely reported misogyny and violence toward women. But the recent publication of Adrienne Miller’s memoir In the Land of Men (2020), which describes her years-long relationship with Wallace while she was literary editor at Esquire , makes a compelling, if unwitting, argument for the necessity of such biographically informed criticism. Miller documents the connection between Wallace’s life and work in excruciating detail, recounting extended scenes between them in which Wallace speaks and acts nearly identically to the misogynists of Brief Interviews , an identification he encourages by telling her that “some of the interviews were ‘actual conversations I had when I had to break up with people.’”

But though Miller lays out the “sexism” of Wallace’s fiction, especially Jest and Brief Interviews , more baldly than any of us Wallace scholars has so far, she remains, even from the vantage point of twenty years later and post-#MeToo, unable or unwilling to identify Wallace’s treatment of her as abusive or misogynistic. In fact, most shocking about the memoir is not its record of Wallace’s behavior but its methodical and steadfast refusal to acknowledge the gender violence of that behavior, and Miller’s disturbing pattern of normalizing, apologizing for, and denying it.

Ultimately, she attempts to redirect us from the question of whether her relationship with Wallace qualifies as abuse or sexual harassment by asking, “Who looks to the artist’s life for moral guidance anyway?” and “What are we to do with the art of profoundly compromised men?” But rather than neatly pivoting from Wallace’s culpability, these questions reveal important reasons why we must consider the lives of such men in conversation with their art. For these men are not merely passively “compromised” but aggressively compromis ing , in ways that our misogynistic culture obscures, and which savvy investigation of their art and lives can illuminate. And “moral” investigation is particularly indicated by the work of Wallace, who declared himself a maverick writer willing to return literature to earnestness and “love” (“Interview with David Foster Wallace” 1993), who wrote fiction that quizzes us on ethics and human value (“Octet” 1999), and who delivered a beloved commencement speech arguing the importance of recognizing one’s inherent narcissism in order to extend care to others.

What does it mean that this artist could not produce in his life the mutually respecting empathy he all but preached in his work (or, most clearly, in his statements about it)? What does it mean that a man and a body of work that claimed feminism in theory primarily produced a stream of abusive relationships between men and women in life and art? What can we learn about the blindness of both men and women to their participation in misogyny and rape culture, despite their professions of awareness of both? How might reading Wallace’s fiction in the contexts of biographical information about him and women’s narratives about their experiences of sexual violence enable us to better understand—and interrupt—the powerful hold misogyny and rape culture have on our society, our art, and our critical practices?

_____________________________________________________________________

Excerpted from #MeToo and Literary Studies: Reading, Writing, and Teaching about Sexual Violence and Rape Culture , edited by Mary K. Holland & Heather Hewett. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Bloomsbury Academic. © 2021 by Mary K. Holland & Heather Hewett.

Mary K. Holland

Previous article, next article.

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

- Kindle Store

- Kindle eBooks

- Literature & Fiction

Promotions apply when you purchase

These promotions will be applied to this item:

Some promotions may be combined; others are not eligible to be combined with other offers. For details, please see the Terms & Conditions associated with these promotions.

Buy for others

Buying and sending ebooks to others.

- Select quantity

- Buy and send eBooks

- Recipients can read on any device

These ebooks can only be redeemed by recipients in the US. Redemption links and eBooks cannot be resold.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Fate, Time, and Language: An Essay on Free Will Kindle Edition

The Pulitzer Prize finalist and author of The Pale King and Infinite Jest weighs in on a philosophical controversy in this fascinating early work. In 1962, the philosopher Richard Taylor used six commonly accepted presuppositions to imply that human beings have no control over the future. David Foster Wallace not only took issue with Taylor's method, which, according to him, scrambled the relations of logic, language, and the physical world, but also detected a semantic trick at the heart of Taylor's argument. Fate, Time, and Language presents Wallace's brilliant critique of Taylor's work. Written long before the publication of his fiction and essays, Wallace's thesis reveals his great skepticism of abstract thinking and any school of thought that abandons "the very old traditional human verities that have to do with spirituality and emotion and community." As Wallace rises to meet the challenge to free will presented by Taylor, we witness the developing perspective of this major novelist, along with his struggle to establish solid logical ground for his convictions. This volume, edited by Steven M. Cahn and Maureen Eckert, reproduces Taylor's original article and other works on fatalism cited by Wallace. James Ryerson's introduction connects Wallace's early philosophical work to the themes and explorations of his later fiction, and Jay Garfield supplies a critical biographical epilogue.

- Print length 263 pages

- Language English

- Sticky notes On Kindle Scribe

- Publisher Columbia University Press

- Publication date December 10, 2010

- File size 1915 KB

- Page Flip Enabled

- Word Wise Enabled

- Enhanced typesetting Enabled

- See all details

Customers who bought this item also bought

Editorial Reviews

From publishers weekly.

an excellent summary of Wallace's thought and writing which shows how his philosophical interests were not purely cerebral, but arose from, and fed into, his emotional and ethical concerns.

Valuable and interesting.

[A] tough and impressive book.Financial Times

As an early glimpse at the preoccupations of one of the 20th century's most compelling and philosophical authors, it is invaluable, and Wallace's conclusion... is simply elegant.

Fate, Time, and Laguage contains a great deal of first-rate philosophy throughout, and not least in Wallace's extraordinarily professional and ambitious essay....

Fatalism, the sorrowful erasure of possibilities, is the philosophical problem at the heart of this book. To witness the intellectual exuberance and bravado with which the young Wallace attacks this problem, the ambition and elegance of the solution he works out so that possibility might be resurrected, is to mourn, once again, the possibilities that have been lost.

This book is for any reader who has enjoyed the works of Wallace and for philosophy students specializing in fatalism.

I think Dave, foremost among a group of writers that also includes George Saunders and Rick Moody, created a new American literary idiom through which people who are young, or who aren't young but still feel like they are, can give voice to the full range of their intelligence and emotion and moral sensibility without feeling dorky and uncontemporary. It's very hard to read Dave and not feel almost peer-pressured to emulate him his style is utterly contagious. But none of his emulators have his giant talent or his passionate precision. Somebody could write a whole monograph on how deliberately and artfully he deploys the modifier 'sort of.'

About the Author

David Foster Wallace (1962-2008) wrote the acclaimed novels Infinite Jest and The Broom of the System and the story collections Oblivion , Brief Interviews with Hideous Men , and Girl with Curious Hair . His nonfiction includes the essay collections Consider the Lobster and A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again and the full-length work Everything and More .

Product details

- ASIN : B004EHZDDO

- Publisher : Columbia University Press; Illustrated edition (December 10, 2010)

- Publication date : December 10, 2010

- Language : English

- File size : 1915 KB

- Text-to-Speech : Enabled

- Screen Reader : Supported

- Enhanced typesetting : Enabled

- X-Ray : Not Enabled

- Word Wise : Enabled

- Sticky notes : On Kindle Scribe

- Print length : 263 pages

- #204 in Logic & Language Philosophy

- #404 in Free Will & Determinism Philosophy

- #440 in Metaphysics (Kindle Store)

About the author

Steven m. cahn.

Steven M. Cahn a Professor of Philosophy at the City University of New York Graduate Center in New York City.

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Start Selling with Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us