What is phenomenology in qualitative research?

Last updated

7 February 2023

Reviewed by

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

Take a closer look at this type of qualitative research along with characteristics, examples, uses, and potential disadvantages.

Analyze your phenomenological research

Use purpose-built tools to surface insights faster

- What is phenomenological qualitative research?

Phenomenological research is a qualitative research approach that builds on the assumption that the universal essence of anything ultimately depends on how its audience experiences it .

Phenomenological researchers record and analyze the beliefs, feelings, and perceptions of the audience they’re looking to study in relation to the thing being studied. Only the audience’s views matter—the people who have experienced the phenomenon. The researcher’s personal assumptions and perceptions about the phenomenon should be irrelevant.

Phenomenology is a type of qualitative research as it requires an in-depth understanding of the audience’s thoughts and perceptions of the phenomenon you’re researching. It goes deep rather than broad, unlike quantitative research . Finding the lived experience of the phenomenon in question depends on your interpretation and analysis.

- What is the purpose of phenomenological research?

The primary aim of phenomenological research is to gain insight into the experiences and feelings of a specific audience in relation to the phenomenon you’re studying. These narratives are the reality in the audience’s eyes. They allow you to draw conclusions about the phenomenon that may add to or even contradict what you thought you knew about it from an internal perspective.

- How is phenomenology research design used?

Phenomenological research design is especially useful for topics in which the researcher needs to go deep into the audience’s thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

It’s a valuable tool to gain audience insights, generate awareness about the item being studied, and develop new theories about audience experience in a specific, controlled situation.

- Examples of phenomenological research

Phenomenological research is common in sociology, where researchers aim to better understand the audiences they study.

An example would be a study of the thoughts and experiences of family members waiting for a loved one who is undergoing major surgery. This could provide insights into the nature of the event from the broader family perspective.

However, phenomenological research is also common and beneficial in business situations. For example, the technique is commonly used in branding research. Here, audience perceptions of the brand matter more than the business’s perception of itself.

In branding-related market research, researchers look at how the audience experiences the brand and its products to gain insights into how they feel about them. The resulting information can be used to adjust messaging and business strategy to evoke more positive or stronger feelings about the brand in the future.

Free AI content analysis generator

Make sense of your research by automatically summarizing key takeaways through our free content analysis tool.

- The 4 characteristics of phenomenological research design

The exact nature of phenomenological research depends on the subject to be studied. However, every research design should include the following four main tenets to ensure insightful and actionable outcomes:

A focus on the audience’s interpretation of something . The focus is always on what an experience or event means to a strictly defined audience and how they interpret its meaning.

A lack of researcher bias or prior influence . The researcher has to set aside all prior prejudices and assumptions. They should focus only on how the audience interprets and experiences the event.

Connecting objectivity with lived experiences . Researchers need to describe their observations of how the audience experienced the event as well as how the audience interpreted their experience themselves.

- Types of phenomenological research design

Each type of phenomenological research shares the characteristics described above. Social scientists distinguish the following three types:

Existential phenomenology —focuses on understanding the audience’s experiences through their perspective.

Hermeneutic phenomenology —focuses on creating meaning from experiences through the audience’s perspective.

Transcendental phenomenology —focuses on how the phenomenon appears in one consciousness on a broader, scientific scale.

Existential phenomenology is the most common type used in a business context. It’s most valuable to help you better understand your audience.

You can use hermeneutic phenomenology to gain a deeper understanding of how your audience perceives experiences related to your business.

Transcendental phenomenology is largely reserved for non-business scientific applications.

- Data collection methods in phenomenological research

Phenomenological research draws from many of the most common qualitative research techniques to understand the audience’s perspective.

Here are some of the most common tools to collect data in this type of research study:

Observing participants as they experience the phenomenon

Interviewing participants before, during, and after the experience

Focus groups where participants experience the phenomenon and discuss it afterward

Recording conversations between participants related to the phenomenon

Analyzing personal texts and observations from participants related to the phenomenon

You might not use these methods in isolation. Most phenomenological research includes multiple data collection methods. This ensures enough overlap to draw satisfactory conclusions from the audience and the phenomenon studied.

Get started collecting, analyzing, and understanding qualitative data with help from quickstart research templates.

- Limitations of phenomenological research

Phenomenological research can be beneficial for many reasons, but its downsides are just as important to discuss.

This type of research is not a solve-all tool to gain audience insights. You should keep the following limitations in mind before you design your research study and during the design process:

These audience studies are typically very small. This results in a small data set that can make it difficult for you to draw complete conclusions about the phenomenon.

Researcher bias is difficult to avoid, even if you try to remove your own experiences and prejudices from the equation. Bias can contaminate the entire outcome.

Phenomenology relies on audience experiences, so its accuracy depends entirely on how well the audience can express those experiences and feelings.

The results of a phenomenological study can be difficult to summarize and present due to its qualitative nature. Conclusions typically need to include qualifiers and cautions.

This type of study can be time-consuming. Interpreting the data can take days and weeks.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 22 August 2024

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 August 2024

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

- Privacy Policy

Home » Phenomenology – Methods, Examples and Guide

Phenomenology – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

Phenomenology

Definition:

Phenomenology is a branch of philosophy that is concerned with the study of subjective experience and consciousness. It is based on the idea that the essence of things can only be understood through the way they appear to us in experience, rather than by analyzing their objective properties or functions.

Phenomenology is often associated with the work of philosopher Edmund Husserl, who developed a method of phenomenological inquiry that involves suspending one’s preconceptions and assumptions about the world and focusing on the pure experience of phenomena as they present themselves to us. This involves bracketing out any judgments, beliefs, or theories about the phenomena, and instead attending closely to the subjective qualities of the experience itself.

Phenomenology has been influential not only in philosophy but also in other fields such as psychology, sociology, and anthropology, where it has been used to explore questions of perception, meaning, and human experience.

History of Phenomenology

Phenomenology is a philosophical movement that began in the early 20th century, primarily in Germany. It was founded by Edmund Husserl, a German philosopher who is often considered the father of phenomenology.

Husserl’s work was deeply influenced by the philosophy of Immanuel Kant, particularly his emphasis on the importance of subjective experience. However, Husserl sought to go beyond Kant’s transcendental idealism by developing a rigorous method of inquiry that would allow him to examine the structures of consciousness and the nature of experience in a systematic way.

Husserl’s first major work, Logical Investigations (1900-1901), laid the groundwork for phenomenology by introducing the idea of intentional consciousness, or the notion that all consciousness is directed towards objects in the world. He went on to develop a method of “bracketing” or “epoche,” which involved setting aside one’s preconceptions and assumptions about the world in order to focus on the pure experience of phenomena as they present themselves.

Other philosophers, such as Martin Heidegger and Jean-Paul Sartre, built on Husserl’s work and developed their own versions of phenomenology. Heidegger, in particular, emphasized the importance of language and the role it plays in shaping our understanding of the world, while Sartre focused on the relationship between consciousness and freedom.

Today, phenomenology continues to be an active area of philosophical inquiry, with many contemporary philosophers drawing on its insights to explore questions of perception, meaning, and human experience.

Types of Phenomenology

There are several types of phenomenology that have emerged over time, each with its own focus and approach. Here are some of the most prominent types of phenomenology:

Transcendental Phenomenology

This is the type of phenomenology developed by Edmund Husserl, which aims to investigate the structures of consciousness and experience in a systematic way by using the method of epoche or bracketing.

Existential Phenomenology

This type of phenomenology, developed by philosophers such as Martin Heidegger and Jean-Paul Sartre, focuses on the subjective experience of individual existence, emphasizing the role of freedom, authenticity, and the search for meaning in human life.

Hermeneutic Phenomenology

This type of phenomenology, developed by philosophers such as Hans-Georg Gadamer and Paul Ricoeur, emphasizes the role of interpretation and understanding in human experience, particularly in the context of language and culture.

Phenomenology of Perception

This type of phenomenology, developed by Maurice Merleau-Ponty, emphasizes the embodied and lived nature of perception, arguing that perception is not simply a matter of passive reception but is instead an active and dynamic process of engagement with the world.

Phenomenology of Sociality

This type of phenomenology, developed by philosophers such as Alfred Schutz and Emmanuel Levinas, focuses on the social dimension of human experience, exploring how we relate to others and how our understanding of the world is shaped by our interactions with others.

Methods of Phenomenology

Here are some of the key methods that phenomenologists use to investigate human experience:

Epoche (Bracketing)

This is a key method in phenomenology, which involves setting aside one’s preconceptions and assumptions about the world in order to focus on the pure experience of phenomena as they present themselves. By bracketing out any judgments, beliefs, or theories about the phenomena, one can attend more closely to the subjective qualities of the experience itself.

Introspection

Phenomenologists often rely on introspection, or a careful examination of one’s own mental states and experiences, as a way of gaining insight into the nature of consciousness and subjective experience.

Descriptive Analysis

Phenomenology also involves a careful description and analysis of subjective experiences, paying close attention to the way things appear to us in experience, rather than analyzing their objective properties or functions.

Another method used in phenomenology is the variation technique, in which one systematically varies different aspects of an experience in order to gain a deeper understanding of its structure and meaning.

Phenomenological Reduction

This method involves reducing a phenomenon to its essential features or structures, in order to gain a deeper understanding of its nature and significance.

Epoché Variations

This method involves examining different aspects of an experience through the process of epoché or bracketing, to gain a more nuanced understanding of its subjective qualities and significance.

Applications of Phenomenology

Phenomenology has a wide range of applications across many fields, including philosophy, psychology, sociology, education, and healthcare. Here are some of the key applications of phenomenology:

- Philosophy : Phenomenology is primarily a philosophical approach, and has been used to explore a wide range of philosophical issues related to consciousness, perception, identity, and the nature of reality.

- Psychology : Phenomenology has been used in psychology to study human experience and consciousness, particularly in the areas of perception, emotion, and cognition. It has also been used to develop new forms of psychotherapy, such as existential and humanistic psychotherapy.

- Sociology : Phenomenology has been used in sociology to study the subjective experience of individuals within social contexts, particularly in the areas of culture, identity, and social change.

- Education : Phenomenology has been used in education to explore the subjective experience of students and teachers, and to develop new approaches to teaching and learning that take into account the individual experiences of learners.

- Healthcare : Phenomenology has been used in healthcare to explore the subjective experience of patients and healthcare providers, and to develop new approaches to patient care that are more patient-centered and focused on the individual’s experience of illness.

- Design : Phenomenology has been used in design to better understand the subjective experience of users and to create more user-centered products and experiences.

- Business : Phenomenology has been used in business to better understand the subjective experience of consumers and to develop more effective marketing strategies and user experiences.

Purpose of Phenomenology

The purpose of phenomenology is to understand the subjective experience of human beings. Phenomenology is concerned with the way things appear to us in experience, rather than their objective properties or functions. The goal of phenomenology is to describe and analyze the essential features of subjective experience, and to gain a deeper understanding of the nature of consciousness, perception, and human existence.

Phenomenology is particularly concerned with the ways in which subjective experience is structured, and with the underlying meanings and significance of these structures. Phenomenologists seek to identify the essential features of subjective experience, such as intentionality, embodiment, and lived time, and to explore the ways in which these features give rise to meaning and significance in human life.

Phenomenology has a wide range of applications across many fields, including philosophy, psychology, sociology, education, healthcare, and design. In each of these fields, phenomenology is used to gain a deeper understanding of human experience, and to develop new approaches and strategies that are more focused on the subjective experiences of individuals.

Overall, the purpose of phenomenology is to deepen our understanding of human experience and to provide insights into the nature of consciousness, perception, and human existence. Phenomenology offers a unique perspective on the subjective aspects of human life, and its insights have the potential to transform our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.

Examples of Phenomenology

Phenomenology has many real-life examples across different fields. Here are some examples of phenomenology in action:

- Psychology : In psychology, phenomenology is used to study the subjective experience of individuals with mental health conditions. For example, a phenomenological study might explore the experience of anxiety in individuals with generalized anxiety disorder, or the experience of depression in individuals with major depressive disorder.

- Healthcare : In healthcare, phenomenology is used to explore the subjective experience of patients and to develop more patient-centered approaches to care. For example, a phenomenological study might explore the experience of chronic pain in patients, in order to develop more effective pain management strategies that are based on the patient’s individual experience of pain.

- Education : In education, phenomenology is used to study the subjective experience of students and to develop more effective teaching and learning strategies. For example, a phenomenological study might explore the experience of learning in students, in order to develop teaching methods that are more focused on the individual needs and experiences of learners.

- Business : In business, phenomenology is used to better understand the subjective experience of consumers, and to develop more effective marketing strategies and user experiences. For example, a phenomenological study might explore the experience of using a particular product or service, in order to identify areas for improvement and to create a more user-centered experience.

- Design : In design, phenomenology is used to better understand the subjective experience of users, and to create more user-centered products and experiences. For example, a phenomenological study might explore the experience of using a particular app or website, in order to identify ways to improve the user interface and user experience.

When to use Phenomenological Research

Here are some situations where phenomenological research might be appropriate:

- When you want to explore the meaning and significance of an experience : Phenomenological research is particularly useful when you want to gain a deeper understanding of the subjective experience of individuals and the meanings and significance that they attach to their experiences. For example, if you want to understand the experience of being a first-time parent, phenomenological research can help you explore the various emotions, challenges, and joys that are associated with this experience.

- When you want to develop more patient-centered healthcare: Phenomenological research can be useful in healthcare settings where there is a need to develop more patient-centered approaches to care. For example, if you want to improve pain management strategies for patients with chronic pain, phenomenological research can help you gain a better understanding of the individual experiences of pain and the different ways in which patients cope with this experience.

- When you want to develop more effective teaching and learning strategies : Phenomenological research can be used in education settings to explore the subjective experience of students and to develop more effective teaching and learning strategies that are based on the individual needs and experiences of learners.

- When you want to improve the user experience of a product or service: Phenomenological research can be used in design settings to gain a deeper understanding of the subjective experience of users and to develop more user-centered products and experiences.

Characteristics of Phenomenology

Here are some of the key characteristics of phenomenology:

- Focus on subjective experience: Phenomenology is concerned with the subjective experience of individuals, rather than objective facts or data. Phenomenologists seek to understand how individuals experience and interpret the world around them.

- Emphasis on lived experience: Phenomenology emphasizes the importance of lived experience, or the way in which individuals experience the world through their own unique perspectives and histories.

- Reduction to essence: Phenomenology seeks to reduce the complexities of subjective experience to their essential features or structures, in order to gain a deeper understanding of the nature of consciousness, perception, and human existence.

- Emphasis on description: Phenomenology is primarily concerned with describing the features and structures of subjective experience, rather than explaining them in terms of underlying causes or mechanisms.

- Bracketing of preconceptions: Phenomenology involves bracketing or suspending preconceptions and assumptions about the world, in order to approach subjective experience with an open and unbiased perspective.

- Methodological approach: Phenomenology is both a philosophical and methodological approach, which involves a specific set of techniques and procedures for studying subjective experience.

- Multiple approaches: Phenomenology encompasses a wide range of approaches and variations, including transcendental phenomenology, hermeneutic phenomenology, and existential phenomenology, among others.

Advantages of Phenomenology

Phenomenology offers several advantages as a research approach, including:

- Provides rich, in-depth insights: Phenomenology is focused on understanding the subjective experiences of individuals in a particular context, which allows for a rich and in-depth exploration of their experiences, emotions, and perceptions.

- Allows for participant-centered research: Phenomenological research prioritizes the experiences and perspectives of the participants, which makes it a participant-centered approach. This can help to ensure that the research is relevant and meaningful to the participants.

- Provides a flexible approach: Phenomenological research offers a flexible approach that can be adapted to different research questions and contexts. This makes it suitable for use in a wide range of fields and research areas.

- Can uncover new insights : Phenomenological research can uncover new insights into subjective experience and can challenge existing assumptions and beliefs about a particular phenomenon or experience.

- Can inform practice and policy: Phenomenological research can provide insights that can be used to inform practice and policy decisions in fields such as healthcare, education, and design.

- Can be used in combination with other research approaches : Phenomenological research can be used in combination with other research approaches, such as quantitative methods, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of a particular phenomenon or experience.

Limitations of Phenomenology

Despite the many advantages of phenomenology, there are also several limitations that should be taken into account, including:

- Subjective nature: Phenomenology is focused on subjective experience, which means that it can be difficult to generalize findings to a larger population or to other contexts.

- Limited external validity: Because phenomenological research is focused on a specific context or experience, the findings may have limited external validity or generalizability.

- Potential for researcher bias: Phenomenological research relies heavily on the researcher’s interpretations and analyses of the data, which can introduce potential for bias and subjectivity.

- Time-consuming and resource-intensive: Phenomenological research is often time-consuming and resource-intensive, as it involves in-depth data collection and analysis.

- Difficulty with data analysis: Phenomenological research involves a complex process of data analysis, which can be difficult and time-consuming.

- Lack of standardized procedures: Phenomenology encompasses a range of approaches and variations, which can make it difficult to compare findings across studies or to establish standardized procedures.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Narrative Analysis – Types, Methods and Examples

MANOVA (Multivariate Analysis of Variance) –...

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Triangulation in Research – Types, Methods and...

Content Analysis – Methods, Types and Examples

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 21, Issue 4

- Phenomenology as a healthcare research method

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Alison Rodriguez ,

- Joanna Smith

- School of Healthcare , School of Healthcare, University of Leeds , Leeds , UK

- Correspondence to Dr Joanna Smith, School of Healthcare, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9UT, UK; j.e.smith1{at}leeds.ac.uk

https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2018-102990

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Qualitative research methodologies focus on meaning and although use similar methods have differing epistemological and ontological underpinnings, with each approach offering a different lens to explore, interpret or explain phenomena in real-world contexts and settings. In this article, we provide a brief overview of phenomenology and outline the main phenomenological approaches relevant for undertaking healthcare research.

What is phenomenology?

Edmund Husserl (1859–1938), a philosopher, established the discipline of phenomenology. In Husserl’s approach to phenomenology, now labelled descriptive phenomenology , experiences are described and researcher perceptions are set aside or ‘bracketed’ in order to enter into the life world of the research participant without any presuppositions. 1 Experience is recognised to involve perception, thought, memory, imagination and emotion, each involving ‘intentionality’, as the individual focuses their gaze on a specific ‘thing’ or event. 1 Martin Heidegger (1889–1976), a student of Husserl, rejected the theory of knowledge or ‘epistemology’ that influenced Husserl’s work, and instead adopted ‘ontology’, the science of being. In relation to research, ‘epistemology’ is concerned with what constitutes valid knowledge, and how knowledge is gained with a distinction between justified belief and opinion, while ‘ontology’ ‘is more concerned with the nature of reality and now we understand what exists and is experienced.

- View inline

Key differences between Husserl’s and Heidegger’s approaches to phenomenology

What is phenomenological research?

The philosophy of phenomenology resides within the naturalistic paradigm; phenomenological research asks: ‘ What is this experience like? ’, ‘ What does this experience mean? ’, and ‘ How does the lived world present itself to the participant or to me as the researcher? ’ Not all health research questions that seek to describe patient or professional experiences will be best met by a phenomenological approach; for example, service evaluations may be more suited to a descriptive qualitative design, where highly structured questions aim to find out participant’s views, rather than their lived experience.

Building on the work of Husserl and Heidegger, different approaches and applications of phenomenological to research have been developed. Table 2 , adapted from Rodriguez, 2 highlights the differences between the main traditions of phenomenology.

Comparison of the main phenomenological traditions

Is phenomenology an appropriate approach to undertaking healthcare research?

We will use a study that explored the lived experience of parenting a child with a life-limiting condition to outline the application of van Manen’s approach to phenomenology, 3 and the relevance of the findings to health professionals. The life expectancy of children with life-limiting conditions has increased because of medical and technical advances, with care primarily delivered at home by parents. Evidence suggests that caregiving demands can have a significant impact on parents’ physical, emotional and social well-being. 4 While both qualitative and quantitative research designs can be useful to explore the quality of life for parents living with a child with a life-limiting conditions, a phenomenological approach offers a way to begin to understand the range of factors that can effect parents, from their perspective and experience, revealing meanings that can be ‘hidden’, rather than making inferences. van Manen’s approach was chosen because the associated methods do not ‘break down’ the experience being studied into disconnected parts, but provides rich narrative descriptions and interpretations that describe what it means to be a person in their particular life-world. The phenomenological aim was to develop a ‘pathic’ understanding; the researcher was therefore committed to understanding the experience of the phenomena as a whole, rather than parts of that experience. In addition, van Manen’s approach was chosen because it offers a flexibility to data collection, where there is more of an emphasis on the facilitation of participants to share their views in a non-coercive way and the production of meaning between the researcher and researched compared to other phenomenological approaches ( table 2 ).

Central to data analysis is how the researcher develops a dialogue with the text, rather than using a structured coding approach. Phenomenological themes are derived but are also understood as the structures of experience that contribute to the whole experience. van Manen’s approach draws on a dynamic interplay of six activities, that assist in gaining a deeper understanding of the nature of meaning of everyday experience:

Turning to a phenomenon, a commitment by the researcher to understanding that world.

Investigating experience as we live it rather than as we conceptualise it.

Reflecting on the essential themes, which characterise the phenomenon.

Describing the phenomenon through the art of writing and rewriting.

Maintaining a strong and oriented relation to the phenomenon.

Balancing the research context by considering the parts and the whole. 8

These activities guide the researcher, alongside drawing on the four-life world existentials ( table 2 ), as lenses to explore the data and unveil meanings.

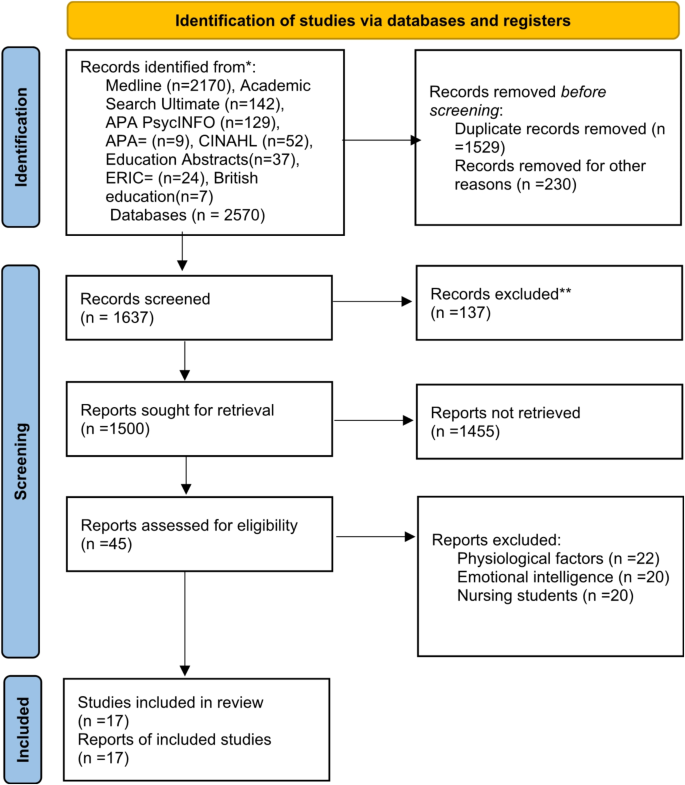

Ten parents of children with life-limiting conditions were interviewed with the aim of gathering lived experiences and generating thick descriptions of what it is like to be a parent of a child with a life-limiting condition. The essential meaning of the phenomenon ‘the lived experience of parenting a child with a life limiting condition’ can be understood as a full-time emotional struggle involving six continuous constituents, presented in figure 1 . Health professional supporting families where a child has a life limiting condition need to be aware of the isolation faced by parents and the strain of constant care demands. Parents innate parental love and commitment to their child can make it challenging to admit they are struggling; support and the way care and services are delivered should be considerate of the holistic needs of these families ( figure 1 ).

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Lived experience of parenting a child with a life-limiting condition.

In summary, in Husserlian (or descriptive)derived approaches, the researcher from the outset has a concrete ‘example’ of the phenomenon being investigated, presuppositions are bracketed and the researcher imaginatively explores the phenomena; a ‘pure’ description of the phenomena’s essential features as it is experienced can then be unveiled. While in Heideggerian, hermeneutic (or interpretive) approaches, the researcher’s perspectives, experiences and interpretations of the data are interwoven, allowing the phenomenologist to provide an ‘interpretation’ rather than just a description of the phenomena as it is experienced. In all phenomenological approaches, the researcher’s role in self-reflection and the co-creativity (between researcher and researched) is required to produce detailed descriptions and interpretations of a participant’s lived experience and are acknowledged throughout the researcher’s journey and the research process. These reflections are deliberated to a greater degree in heuristic and relational approaches, as the self and relational dialogue are considered crucial to the generated understanding of the phenomena being explored.

We will provide more specific details of interpretative phenomenological analysis in the next Research Made Simple series.

- Rodriguez A

- Rodriguez A ,

- Cheater F ,

- Moustakas C

- van Manen M

- Flowers P ,

- Larkin M , et al

- Langridge D

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent Not required.

Provenance and peer review Commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Qualitative Research Methods

- Gumberg Library and CIQR

- Qualitative Methods Overview

Phenomenology

- Case Studies

- Grounded Theory

- Narrative Inquiry

- Oral History

- Feminist Approaches

- Action Research

- Finding Books

- Getting Help

Phenomenology helps us to understand the meaning of people's lived experience. A phenomenological study explores what people experienced and focuses on their experience of a phenomenon. As phenomenology has a strong foundation in philosophy, it is recommended that you explore the writings of key thinkers such as Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre and Merleau-Ponty before embarking on your research. Duquesne's Simon Silverman Phenomenology Center maintains a collection of resources connected to phenomenology as well as hosting lectures, and is a good place to start your exploration.

- Simon Silverman Phenomenology Center

- Husserl, Edmund, 1859–1938

- Heidegger, Martin, 1889–1976

- Sartre, Jean Paul, 1905–1980

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice, 1908–1961

Books and eBooks

Online Resources

- Phenomenology Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry.

- << Previous: Qualitative Methods Overview

- Next: Case Studies >>

- Last Updated: Aug 18, 2023 11:56 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.duq.edu/qualitative_research

Phenomenological Research: Methods And Examples

Ravi was a novice, finding it difficult to select the right research design for his study. He joined a program…

Ravi was a novice, finding it difficult to select the right research design for his study. He joined a program to improve his understanding of research. As a part of his assignment, he was asked to work with a phenomenological research design. To execute good practices in his work, Ravi studied examples of phenomenological research. This let him understand what approaches he needed and areas he could apply the phenomenological method.

What Is Phenomenological Research?

Phenomenological research method, examples of phenomenological research.

A qualitative research approach that helps in describing the lived experiences of an individual is known as phenomenological research. The phenomenological method focuses on studying the phenomena that have impacted an individual. This approach highlights the specifics and identifies a phenomenon as perceived by an individual in a situation. It can also be used to study the commonality in the behaviors of a group of people.

Phenomenological research has its roots in psychology, education and philosophy. Its aim is to extract the purest data that hasn’t been attained before. Sometimes researchers record personal notes about what they learn from the subjects. This adds to the credibility of data, allowing researchers to remove these influences to produce unbiased narratives. Through this method, researchers attempt to answer two major questions:

- What are the subject’s experiences related to the phenomenon?

- What factors have influenced the experience of the phenomenon?

A researcher may also use observations, art and documents to construct a universal meaning of experiences as they establish an understanding of the phenomenon. The richness of the data obtained in phenomenological research opens up opportunities for further inquiry.

Now that we know what is phenomenological research , let’s look at some methods and examples.

Phenomenological research can be based on single case studies or a pool of samples. Single case studies identify system failures and discrepancies. Data from multiple samples highlights many possible situations. In either case, these are the methods a researcher can use:

- The researcher can observe the subject or access written records, such as texts, journals, poetry, music or diaries

- They can conduct conversations and interviews with open-ended questions, which allow researchers to make subjects comfortable enough to open up

- Action research and focus workshops are great ways to put at ease candidates who have psychological barriers

To mine deep information, a researcher must show empathy and establish a friendly rapport with participants. These kinds of phenomenological research methods require researchers to focus on the subject and avoid getting influenced.

Phenomenological research is a way to understand individual situations in detail. The theories are developed transparently, with the evidence available for a reader to access. We can use this methodology in situations such as:

- The experiences of every war survivor or war veteran are unique. Research can illuminate their mental states and survival strategies in a new world.

- Losing family members to Covid-19 hasn’t been easy. A detailed study of survivors and people who’ve lost loved ones can help understand coping mechanisms and long-term traumas.

- What’s it like to be diagnosed with a terminal disease when a person becomes a parent? The conflict of birth and death can’t be generalized, but research can record emotions and experiences.

Phenomenological research is a powerful way to understand personal experiences. It provides insights into individual actions and motivations by examining long-held assumptions. New theories, policies and responses can be developed on this basis. But, the phenomenological research design will be ineffective if subjects are unable to communicate due to language, age, cognition or other barriers. Managers must be alert to such limitations and sharp to interpret results without bias.

Harappa’s Thinking Critically program prepares professionals to think like leaders. Make decisions after careful consideration, engage with opposing views and weigh every possible outcome. Our stellar faculty will help you learn how to back the right strategies. Get the techniques and tools to build an analytical mindset. Effective thinking will improve communication. This in turn can break down barriers and open new avenues for success. Take a step forward with Harappa today!

Explore Harappa Diaries to learn more about topics such as What Are The Objectives Of Research , Fallacy Meaning , Kolb Learning Styles and How to Learn Unlearn And Relearn to upgrade your knowledge and skills.

Reskilling Programs

L&D leaders need to look for reskilling programs that meet organizational goals and employee aspirations. The first step to doing this is to understand the skills gaps and identify what’s necessary. An effective reskilling program will be one that is scalable and measurable. Companies need to understand their immediate goals and prepare for future requirements when considering which employees to reskill.

Are you still uncertain about the kind of reskilling program you should opt for? Speak to our expert to understand what will work best for your organization and employees.

Qualitative study design: Phenomenology

- Qualitative study design

Phenomenology

- Grounded theory

- Ethnography

- Narrative inquiry

- Action research

- Case Studies

- Field research

- Focus groups

- Observation

- Surveys & questionnaires

- Study Designs Home

Used to describe the lived experience of individuals.

- Now called Descriptive Phenomenology, this study design is one of the most commonly used methodologies in qualitative research within the social and health sciences.

- Used to describe how human beings experience a certain phenomenon. The researcher asks, “What is this experience like?’, ‘What does this experience mean?’ or ‘How does this ‘lived experience’ present itself to the participant?’

- Attempts to set aside biases and preconceived assumptions about human experiences, feelings, and responses to a particular situation.

- Experience may involve perception, thought, memory, imagination, and emotion or feeling.

- Usually (but not always) involves a small sample of participants (approx. 10-15).

- Analysis includes an attempt to identify themes or, if possible, make generalizations in relation to how a particular phenomenon is perceived or experienced.

Methods used include:

- participant observation

- in-depth interviews with open-ended questions

- conversations and focus workshops.

Researchers may also examine written records of experiences such as diaries, journals, art, poetry and music.

Descriptive phenomenology is a powerful way to understand subjective experience and to gain insights around people’s actions and motivations, cutting through long-held assumptions and challenging conventional wisdom. It may contribute to the development of new theories, changes in policies, or changes in responses.

Limitations

- Does not suit all health research questions. For example, an evaluation of a health service may be better carried out by means of a descriptive qualitative design, where highly structured questions aim to garner participant’s views, rather than their lived experience.

- Participants may not be able to express themselves articulately enough due to language barriers, cognition, age, or other factors.

- Gathering data and data analysis may be time consuming and laborious.

- Results require interpretation without researcher bias.

- Does not produce easily generalisable data.

Example questions

- How do cancer patients cope with a terminal diagnosis?

- What is it like to survive a plane crash?

- What are the experiences of long-term carers of family members with a serious illness or disability?

- What is it like to be trapped in a natural disaster, such as a flood or earthquake?

Example studies

- The patient-body relationship and the "lived experience" of a facial burn injury: a phenomenological inquiry of early psychosocial adjustment . Individual interviews were carried out for this study.

- The use of group descriptive phenomenology within a mixed methods study to understand the experience of music therapy for women with breast cancer . Example of a study in which focus group interviews were carried out.

- Understanding the experience of midlife women taking part in a work-life balance career coaching programme: An interpretative phenomenological analysis . Example of a study using action research.

- Holloway, I. & Galvin, K. (2017). Qualitative research in nursing and healthcare (Fourth ed.): John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Rodriguez, A., & Smith, J. (2018). Phenomenology as a healthcare research method . Journal of Evidence Based Nursing , 21(4), 96-98. doi: 10.1136/eb-2018-102990

- << Previous: Methodologies

- Next: Grounded theory >>

- Last Updated: Jul 3, 2024 11:46 AM

- URL: https://deakin.libguides.com/qualitative-study-designs

Phenomenology In Qualitative Research

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

What is phenomenology?

Phenomenology in qualitative research is characterized by a focus on understanding the meaning of lived experience from the perspective of the individual.

Instead of testing hypotheses or seeking to generalize findings to a larger population, phenomenological research aims to illuminate the specific and to challenge structural or normative assumptions by revealing the subjective experiences and perceptions of individuals.

This approach is particularly valuable for gaining insights into people’s motivations and actions, and for cutting through taken-for-granted assumptions and conventional wisdom.

Aim of Phenomenological Research

The aim of phenomenological research is to arrive at phenomenal understandings and insights into the meaning of lived experience.

These insights should be “impressively unique” and “primordially meaningful”, illuminating the specific experience being studied.

Phenomenological research attempts to uncover the meaning in lived experiences that are often overlooked in daily life. In other words, phenomenology asks the basic question: “What is this (primal) experience like?

To do this, phenomenological research examines experience as it appears to consciousness, seeking to avoid any preconceptions or assumptions.

Rather than simply describing what participants say, phenomenological research seeks to go deeper, to uncover implicit meanings and reveal the participant’s lifeworld.

This is not a matter of making generalized statements, but of understanding the experience from the individual’s perspective.

The aim is not to provide causal explanations or to theorize about the experience, but to “restore to each experience the ontological cipher which marks it internally.

Characteristics of Phenomenology

Phenomenology is best understood as a radical, anti-traditional style of philosophising that emphasizes describing phenomena as they appear to consciousness. It is not a set of dogmas or a system, but rather a practice of doing philosophy.

Here are some key characteristics of phenomenology:

- Focus on Experience: Phenomenology is concerned with the “phenomena,” which refers to anything that appears in the way that it appears to consciousness. This includes experiences, perceptions, thoughts, feelings, and meanings.

- First-Person Perspective: Phenomenology emphasizes the importance of the first-person, subjective experience. It seeks to understand the world as it is lived and experienced by individuals.

- Intentionality: A central concept in phenomenology is intentionality, which refers to the directedness of consciousness toward an object. This means that consciousness is always consciousness of something, and this directedness shapes how we experience the world.

- Bracketing (Epoche): Phenomenological research often involves “bracketing” or setting aside preconceived notions and assumptions about the world. This allows researchers to approach phenomena with an open mind and focus on how they appear in experience.

- Descriptive Emphasis: Phenomenology prioritizes description over explanation or interpretation. The aim is to provide a rich and nuanced account of experience as it is lived, without imposing theoretical frameworks or seeking to explain it in terms of external factors.

- Search for Essences: Phenomenology is interested in uncovering the essential structures and meanings of experience. This involves going beyond the particularities of individual experiences to grasp the shared features that make them what they are.

- Holistic Approach: Phenomenology seeks to understand experience in a holistic way , recognizing the interconnectedness of mind, body, and world. It rejects reductionist approaches that attempt to explain experience solely in terms of its parts.

- Use of Examples: Phenomenological researchers often use concrete examples to illustrate and explore the meaning of experience. These examples can be drawn from personal narratives, literature, or other sources that provide rich descriptions of lived experience.

Is phenomenology an epistemology or ontology?

Phenomenology straddles or undermines the traditional distinction between epistemology and ontology. Traditionally, epistemology is understood as the study of how we come to understand and have knowledge of the world, while ontology is the study of the nature of reality itself.

- Phenomenology investigates both how we understand the world and the nature of reality through its focus on phenomena . By examining how things appear to us, phenomenology analyzes our way of experiencing and understanding the world, simultaneously addressing questions about the objects themselves and their modes of appearance.

- Heidegger suggests that ontology is only possible through phenomenology . According to this view, analyzing our being-in-the-world is key to understanding the nature of reality itself.

Instead of separating subject and object, or the knower and the known, phenomenology highlights their interrelation, arguing that the mind is essentially open to the world, and reality is essentially capable of manifesting itself to us.

Exploring Phenomenology: Three Key Perspectives

1. husserl’s transcendental phenomenology.

Edmund Husserl viewed phenomenology as the “science of the essence of consciousness”, emphasizing the intentional structure of conscious acts. Central for phenomenological psychology was phenomenological philosopher Husserl’s understanding of “intentionality,” the idea that whenever we are conscious we are conscious of something, making the job of the researcher to better understand people’s experiences of things “in their appearing” (Langdridge, 2007, p. 13).

- Intentionality: This key concept describes consciousness’s directedness towards objects—our experiences are always about something. This “aboutness” isn’t limited to physical objects and encompasses mental acts like remembering, imagining, or even fearing.

- Essence over Existence: Husserl’s phenomenology focuses on uncovering the invariant structures of consciousness, aiming to reveal the essence of experiences like perception, thought, or emotion. It is not concerned with whether the object of an experience actually exists in the world.

- Transcendental Reduction: To grasp these essences, Husserl introduces the “epoché,” a methodological tool to bracket our natural attitude towards the world. This doesn’t mean denying the world’s existence; it’s about shifting focus from the objects themselves to how they appear in our consciousness.

- Example: When perceiving a table, we experience it through different profiles or perspectives. We can’t see all sides simultaneously, yet we grasp the table as a unified object. Transcendental phenomenology investigates the structures of consciousness that enable this constitution of objects from a multitude of appearances.

2. Heidegger’s Hermeneutical Phenomenology:

Martin Heidegger, while influenced by Husserl, diverged by emphasizing the importance of hermeneutics—the art of interpretation—in phenomenological inquiry.

- Being-in-the-World: Unlike Husserl’s focus on pure consciousness, Heidegger grounds his phenomenology in the concrete existence of Dasein—a term he uses to describe human existence’s inherent being-in-the-world.

- Facticity and Historicity: Heidegger recognizes that our understanding of the world is shaped by our historical and cultural contexts. We don’t encounter the world as a neutral observer, but through a lens of pre-existing interpretations and practices.

- Self-Concealing Nature of Phenomena: Heidegger contends that things don’t always reveal themselves fully. Our understanding is often clouded by biases, assumptions, or simply the inherent ambiguity of existence. Phenomenology, therefore, becomes a process of uncovering hidden meanings and questioning taken-for-granted assumptions.

- Example: Consider the act of using a hammer. For Heidegger, this isn’t just a neutral interaction with an object. It reveals a whole network of meanings related to our practical engagement with the world, our understanding of “for-the-sake-of-which” (building something), and our shared cultural practices.

3. Merleau-Ponty’s Idea of Perception

Maurice Merleau-Ponty further developed phenomenology by emphasizing the centrality of embodiment in our experience of the world.

- The Primacy of Perception: Merleau-Ponty challenges the traditional view of perception as a passive reception of sensory data. He argues that perception is an active and embodied engagement with the world.

- Body-Subject: Merleau-Ponty rejects the Cartesian mind-body dualism. For him, our body is not just an object in the world, but the very medium through which we experience and understand the world. The body is the “vehicle of being-in-the-world”.

- Perception as Foundation: Merleau-Ponty places perception at the heart of his phenomenology. He sees it as the foundation for all other cognitive activities, including thought, language, and intersubjectivity.

- Example: Consider the experience of touching a piece of velvet. It’s not simply that we receive tactile sensations. Our hand actively explores the fabric, and the perceived texture emerges from the dynamic interplay between our moving hand and the resistant surface. This experience can’t be reduced to purely mental representations or objective properties of the velvet; it arises from the embodied engagement between the perceiving subject and the world.

Data Collection in Phenomenological Research

Phenomenological research focuses on understanding lived experience, and therefore relies on qualitative data that can illuminate the subjective experiences of individuals.

Because phenomenology aims to examine experience on its own terms, it is wary of imposing pre-defined categories or structures on the data.

Many phenomenological philosophers and researchers avoid using the term “method” in favor of talking about the phenomenological “approach.”

Interviews are a common method for collecting data in phenomenological research.

Researchers typically use semi-structured or unstructured interviews, which prioritize open-ended questions and allow participants to describe their experiences in their own words.

These interviews aim to elicit detailed, concrete descriptions of specific experiences rather than abstract generalizations.

For instance, instead of asking “What does friendship mean to you?”, a researcher might ask: “Can you describe a time you felt particularly connected to a friend?”.

This shift from the abstract to the concrete helps researchers access the pre-reflective, lived experience of the phenomenon, revealing its texture and nuanc

Researchers may also use follow-up questions to clarify or gain a deeper understanding of participants’ responses.

Phenomenological interviews often explore experiences across multiple dimensions:

- Bodily sensations: The interviewer might ask: “What was happening in your body during that experience?” or “How did that situation make you feel physically?” These questions help uncover the embodied aspects of experience often overlooked in more cognitively-focused approaches.

- Thoughts and cognitions: Questions like “What sense did you make of that experience?” or “What thoughts went through your head?” help explore the cognitive interpretations participants make about their experiences.

- Emotional responses: The interviewer may ask: “What feelings were present during that time?” or “How did that situation make you feel emotionally?” Allowing participants to articulate their feelings without judgment or interpretation is crucial.

- Relational dynamics: When exploring interpersonal experiences, interviewers might ask: “What was it like to be with that person during that event?” or “How did your relationship with that person shape your experience?” Recognizing that experiences are not confined to the individual but are shaped by social and relational contexts is central to phenomenological inquiry

Beyond interviews, phenomenological research may draw upon a variety of other methods, including :

- Discussions: Open-ended discussions among participants who share an experience can shed light on commonalities and differences in how the phenomenon is lived.

- Participant observation: This method involves the researcher immersing themselves in a particular setting or community to gain firsthand experience of the phenomenon being studied.

- Analysis of personal texts: Participants’ diaries, letters, or other written accounts of their experiences can provide valuable insights into their subjective lifeworlds.

- Creative media: Researchers may use art, dance, literature, photography, or other creative media to encourage participants to express their experiences in non-verbal ways.

“Examples” are particularly important in phenomenological research. Rather than treating individual experiences as mere illustrations of general concepts, phenomenology understands examples as offering a unique window into the essence of a phenomenon.

Researchers carefully select and analyze examples to uncover and articulate the essential features of a lived experience.

Number of Participants in Phenomenological Studies

There is no prescribed number of participants required for a phenomenological study. Some researchers may choose to include a larger number of participants.

Phenomenological research emphasizes in-depth understanding of lived experiences rather than statistical generalization.

Therefore, sample size is less important than the richness and depth of the data obtained from the participants.

However, phenomenological studies that include more than a handful of participants risk being superficial and may miss the spirit of phenomenology.

Here are some examples of approaches to the number of participants in a phenomenological study:

- Three to six participants are considered to give sufficient variation.

- One participant can be used for a case study.

- Researchers can also use autobiographical reflection .

- Single-case studies can identify issues that illustrate discrepancies and system failures and illuminate or draw attention to “different” situations, but positive inferences are less easy to make without a small sample of participants.

- The strength of inference increases rapidly once factors start to recur with more than one participant .

Analyzing Data in Phenomenological Research

There are a variety of approaches to conducting phenomenological research and analyzing data.

The variety of approaches within phenomenological research can make it challenging for students to navigate, as there are no fixed rules or procedures

The specific analytic strategies used in a phenomenological study depend on the researcher’s chosen approach and the nature of the phenomenon being investigated.

Some researchers advocate for a more orthodox approach to phenomenological research that prioritizes rigorous description and aims to uncover essential structures of experience.

Descriptive Phenomenology

This approach, exemplified by the work of Giorgi and Wertz, emphasizes a rigorous, descriptive approach to capturing the essential structures of experience. It involves bracketing assumptions, focusing on pre-reflective experience, and seeking generalizable insight

For example, Giorgi’s descriptive phenomenological method involves a multi-step procedure for analyzing descriptions of lived experience:

- Read the entire description to gain a holistic understanding.

- Divide the description into smaller units of meaning.

- Explicate the psychological significance of each meaning unit.

Hermeneutic Phenomenology

Other researchers, while still grounding their work in phenomenological philosophy, emphasize the importance of interpretation in understanding the unique, lived experience of individuals.

This approach, embraced by researchers like van Manen, prioritizes interpretation and dialogue in understanding the unique, lived experience of individuals.

For example, van Manen’s hermeneutic phenomenology emphasizes the role of interpretation and reflection in uncovering meaning in lived experience.

It acknowledges the researcher’s role in shaping interpretations and emphasizes the transition from pre-reflective experience to conceptual understanding.

Van Manen suggests that researchers should explicate their own assumptions and biases in order to better understand how they might be shaping their interpretations of the data.

His approach also highlights the importance of understanding the transition from pre-reflective experience to conceptual understanding.

Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis

If you are learning phenomenology, struggling with the material is expected.

Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) has become popular because it offers novice researchers a concrete structure, but its set structures may cause researchers to get caught up in method and lose the essence of the phenomenon being studied.

Developed by Jonathan Smith, IPA is a qualitative research method designed to gain an in-depth understanding of how individuals experience and make sense of specific situations.

It focuses on individual experiences and interpretations rather than aiming to uncover universal essences. IPA draws on a broader range of phenomenological thinkers than just Husserl.

It differs from descriptive phenomenology by incorporating an interpretive component, acknowledging that individuals are inherently engaged in meaning-making processes.

Critical Phenomenology

Critical phenomenology expands upon traditional phenomenology by examining the impact of social structures on lived experiences of power and oppression.

Critical phenomenology acknowledges that societal structures like capitalism, colonialism, and patriarchy shape our lifeworlds and cannot be fully put aside

A key goal of critical phenomenology is to identify practical strategies for challenging oppressive structures and fostering liberatory ways of being in the world.

In psychology, phenomenology is linked with a critical realist epistemology; here, the real world exists, but it cannot be fully discovered because our experiences of it are always mediated (Shaw, 2019).

Regardless of the specific approach, several key principles should guide data analysis in phenomenological research:

- Focus on description : Phenomenological research aims to describe the lived experience of a phenomenon, rather than explain or theorize about it.

- Attend to pre-reflective experience : Researchers should strive to move beyond participants’ initial, surface-level descriptions to uncover the deeper, often implicit, meanings embedded in their experiences.

- Adopt a holistic perspective : A thorough analysis considers various aspects of experience, including embodiment, intersubjectivity, and the influence of social and cultural factors.

Reflexivity in Phenomenological Research

Phenomenological research acknowledges that researchers are active participants who bring their own perspectives and experiences to the research process.

It’s important for researchers to practice reflexivity by setting aside their own assumptions and previous knowledge in order to see the world anew through the lens of the participants’ lived experiences.

This process, known as bracketing , is an attempt to approach the research with “fresh eyes,” free from contaminating assumptions. It involves:

- Adopting a self-critical, reflexive meta-awareness: This means questioning “common sense” and taken-for-granted assumptions to reveal more about the nature of subjectivity.

- Abstaining from judgments about the truth or reality of objects in the world: For example, if a participant mentions seeing a ghost, the researcher focuses on what the ghost means to the person and how they experienced it subjectively rather than questioning the existence of ghosts.

- Recognizing the impossibility of completely removing subjectivity: Rather than trying to eliminate subjectivity, researchers should actively recognize its impact and engage with their own (inter-)subjectivity to better understand the other.

Bracketing is an ongoing process that requires mindfulness, curiosity, compassion, and a “genuinely unknowing stance” to remain open to new understandings and avoid imposing the researcher’s own biases on the data.

This is essential for rigorous phenomenological research, as subjectivity is central to the investigation.

However, different schools of thought within phenomenology emphasize different aspects of bracketing:

- Descriptive phenomenologists focus on reflexively setting aside previous understandings to prioritize the participant’s perspective.

- Hermeneutic phenomenologists strive for transparency in their interpretations.

- Critical phenomenology acknowledges that societal structures like capitalism, colonialism, and patriarchy shape our lifeworlds and cannot be fully put aside.

By acknowledging the researcher’s role and emphasizing reflexivity, phenomenological research aims to ensure that findings remain grounded in the participants’ lived experiences, avoiding the imposition of the researcher’s own assumptions or biases.

Pitfalls of Phenomenology Research

A common pitfall of phenomenology research is failing to fully grasp the nuances of phenomenological philosophy.

For example, some studies that use Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) do not adequately acknowledge their hermeneutic foundations or the need to engage in the Epoché, which helps limit the researcher’s pre-understandings.

Without this philosophical anchoring, the research is merely thematic analysis instead of phenomenology.

Other pitfalls in phenomenology research include:

- Missing the Phenomenon: Researchers should not solely focus on what is observed or said, or merely reproduce participant statements. Instead, they must uncover implicit meanings and insights into the participant’s lifeworld, providing an idiographic or general description of the phenomenon. Focusing too heavily on analysis can obscure the phenomenon, while excessive thematic structures can result in presenting “results” rather than phenomenological description.

- Misunderstanding the Phenomenological Attitude: Husserl’s bracketing is often misinterpreted as striving for objectivity, when in reality it is a profoundly subjective act to perceive the world from a fresh perspective. The focus should not be on judging reality, but on exploring experiential appearances and uncovering taken-for-granted aspects of experience. Reproducing participants’ words without going beyond their taken-for-granted understandings can cause research to get stuck in the “natural attitude”.

- Presenting an Insufficiently Holistic Account: Phenomenological studies should not just explore one aspect of consciousness or experience without considering intersubjectivity. A study that only examines an individual’s thoughts or feelings without considering the body or social context misses the point of phenomenology. Good analysis acknowledges existential being and lifeworldly dimensions like embodiment, relationships, time, and space.

- Seeing Subjectivity as Located Within an Individual: Ascribing cognition or emotion solely within individuals perpetuates the dualisms that phenomenology aims to dismantle, such as individual/social, body/mind, self/other, and internal/external. Phenomenology emphasizes a worldly matrix of meaning formed through relationships, shared language, and cultural history, highlighting the interconnectedness of individuals and the world.

- Killing the Phenomenon in Trying to be Scientifically Rigorous: Phenomenological studies that include a large number of participants in a misguided attempt to generalize findings risk being superficial and missing the essence of phenomenology. Similarly, reports that use overly intellectualized language or a detached “scientific” voice compromise the description of the lived experience.

Convincing phenomenological research should:

- Provide a rich and evocative description of the phenomenon.

- Focus on pre-reflective experience and consciousness rather than reproducing participant statements or researcher assumptions.

- Be grounded in phenomenological philosophy.

- Engage with the layered complexity and ambiguity of embodied, intersubjective, and lifeworldly meanings.

Despite ongoing debates among scholars about the best way to apply phenomenology, they share a commitment to an approach of openness and wonder.

This requires discipline, practice, and patience throughout the research process. Phenomenology has the potential to reveal new insights into the nature of lived experience.

Further Information

- Dorfman, E. (2009). History of the lifeworld: From Husserl to Merleau-Ponty. Philosophy Today , 53 (3), 294–303.

- Hanna, R. (2014). Husserl’s crisis and our crisis. International Journal of Philosophical Studies , 22 (5), 752–770.

- Held, K. Husserl’s Phenomenology of the Life-World. In D. Welton (Ed.), The New Husserl: A Critical Reader (pp. 32–62). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Nenon, T. (2015). Husserl and Heidegger on the Social Dimensions of the Life-World. In L. Učník, I. Chvatík, & A. Williams (Eds.), The Phenomenological Critique of Mathematisation and the Question of Responsibility (pp. 175–184). Heidelberg: Springer.

- Dillon, M. C. (1997). Merleau-Ponty’s Ontology . 2nd edition. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

- Overgaard, S. (2007). Wittgenstein and Other Minds: Rethinking Subjectivity and Intersubjectivity with Wittgenstein, Levinas, and Husserl . New York and London: Routledge.

- Steinbock, A. (1995). Home and Beyond: Generative Phenomenology after Husserl . Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

- Theunissen, M. (1986). The Other: Studies in the Social Ontology of Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre and Buber , trans. C. Macann. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1991). The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge . Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Ferguson, H. (2006). Phenomenological Sociology: Insight and Experience in Modern Society . London: SAGE Publications.

- Garfinkel, H. (1984). Studies in Ethnomethodology . Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Heritage, J. (1984). Garfinkel and Ethnomethodology . Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Schutz, A. (1972). The Problem of Social Reality: Collected Papers I . The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

- Broome, M. R., Harland, R., Owen, G. S., & Stringaris, A. (Eds.). (2012). The Maudsley Reader in Phenomenological Psychiatry . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Finlay, L. (2009). Debating phenomenological research methods. Phenomenology & Practice , 3 (1), 6–25.

- Gallagher, S., & Zahavi, D. (2012). The Phenomenological Mind . 2nd edition. London: Routledge.

- Katz, D. (1989). The World of Touch , trans. L.E. Krueger. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Fodor, J. (1987). Psychosemantics . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- From, F. (1953). Om oplevelsen af andres adfærd: Et bidrag til den menneskelige adfærds fænomenologi . Copenhagen: Nyt Nordisk Forlag.

- Galileo, G. (1957). Discoveries and Opinions of Galileo . New York: Anchor House.

- Gadamer, H. (1991). Truth and method (J. Weinsheimer & D. Marshall, Trans.; 2nd ed.). New York: Crossroads. (Original work published 1975)

- Herman, J. (1992). Trauma and recovery . New York: Basic Books.

- Kohut, H. (1984). How does analysis cure? (A. Goldberg & P. Stepansky, Eds.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Orange, D., Atwood, G., & Stolorow, R. (1997). Working intersubjectively: Contextualism in psychoanalytic practice . Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press.

- Stolorow, R., & Atwood, G. (1992). Contexts of being: The intersubjective foundations of psychological life . Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press.

- Connell, R. W. (1985). Teachers’ Work . Sydney, Allen & Unwin.

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research . Chicago, Aldine.

- Gorden, R. L. (1969). Interviewing: Strategy, Techniques and Tactics . Homewood Ill, Dorsey Press.

- Husserl, E. (1970) trans D Carr Logical investigations . New York: Humanities Press.

- Hycner, R. H. (1985). Some guidelines for the phenomenological analysis of interview data. Human Studies , 8 , 279–303.

- Measor, L. (1985). Interviewing: A Strategy in Qualitative Research. In R Burgess (Ed.) Strategies of Educational Research: Qualitative Methods . Lewes, Falmer Press.

- Shaw, R. (2019). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In M. Forrester & C. Sullivan (Eds.), Doing qualitative research in psychology: A practical guide (2nd ed., pp. 185–208). SAGE.

- Landridge D. (2007). Phenomenological Psychology . Harlow, UK: Pearson Education.

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program