Essay on Economics Importance In Daily Life

Students are often asked to write an essay on Economics Importance In Daily Life in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Economics Importance In Daily Life

Understanding economics.

Economics is a subject that studies how people, businesses, and governments make choices about how to use resources. It’s like a guidebook for making decisions. It’s not just about money, but also about time, effort, and what you give up when you make a choice.

Economics in Daily Life

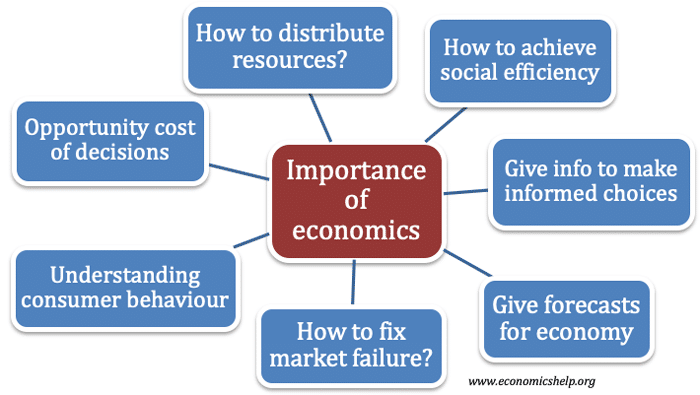

Importance of economics.

Understanding economics helps us make better choices. It helps us decide how to use our resources wisely. It also helps us understand the world around us. For example, why are some things more expensive than others? Economics can help answer that.

Economics and Future

Economics also helps us plan for the future. It helps us understand how to save and invest money. It helps us understand how the economy works. This knowledge can help us make smart choices about jobs, education, and more.

250 Words Essay on Economics Importance In Daily Life

What is economics, personal economics.

Every day, we make decisions about what to buy, where to buy, and how much to spend. We also think about saving money for future needs. This is personal economics. We have to choose how to use our money wisely.

Economics in Business

Businesses also use economics. They decide what products to make, how many to produce, and at what price to sell them. They look at the demand for their products and the cost of making them. This helps them make profits and stay in business.

Economics in Society

Economics also plays a big role in society. It helps governments decide how to use their money. They have to choose what services to provide, like schools, hospitals, and roads. They also have to decide how to pay for these services, usually through taxes.

So, economics is very important in our daily lives. It helps us, businesses, and governments make important decisions. Understanding economics can help us make better choices and understand the world around us. So, even if you’re a student, it’s never too early to start learning about economics!

500 Words Essay on Economics Importance In Daily Life

Economics is a subject that helps us understand how the world works. It studies how people, businesses, and governments make choices about how to use resources. It’s like a guidebook that helps us make smart decisions about money and resources.

Economics in our Daily Lives

Importance of economics in spending.

Economics helps us make good decisions about spending. It teaches us to think about the value of things. For example, if you have only $10 and you want to buy a book that costs $15, economics can help you decide if it’s worth saving up for the book or if you should spend your money on something else.

Economics and Saving

Economics doesn’t just help us with spending, but with saving too. It can help us understand why it’s important to save money for the future. For example, if you save a part of your pocket money every week, you could buy a more expensive toy or game later. This is called delayed gratification, a key concept in economics.

Economics in Resource Allocation

Economics also helps us understand how to use resources wisely. Resources can be anything from time to natural resources like water and trees. For example, if we understand that water is a limited resource, we will be more careful about not wasting it. This is an economic principle called scarcity.

Economics and Jobs

In conclusion, economics is a part of our daily life. It helps us make smart choices about spending and saving. It teaches us to use resources wisely and understand the world of work. Just like a map helps us find our way, economics helps us navigate through life. So, even though it might seem like a tough subject, it’s worth learning because it’s so useful in our daily lives.

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Sustainability

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

The power of economics to explain and shape the world

Press contact :.

Previous image Next image

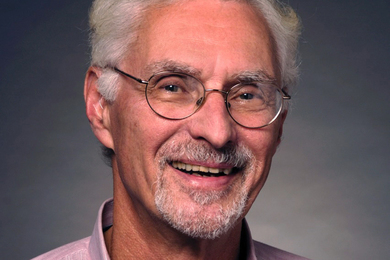

Nobel Prize-winning economist Esther Duflo sympathizes with students who have no interest in her field. She was such a student herself — until an undergraduate research post gave her the chance to learn first-hand that economists address many of the major issues facing human and planetary well-being. “Most people have a wrong view of what economics is. They just see economists on television discussing what’s going to happen to the stock market,” says Duflo, the Abdul Latif Jameel Professor of Poverty Alleviation and Development Economics. “But what people do in the field is very broad. Economists grapple with the real world and with the complexity that goes with it.”

That’s why this year Duflo has teamed up with Professor Abhijit Banerjee to offer 14.009 (Economics and Society’s Greatest Problems), a first-year discovery subject — a class type designed to give undergraduates a low-pressure, high-impact way to explore a field. In this case, they are exploring the range of issues that economists engage with every day: the economic dimensions of climate change, international trade, racism, justice, education, poverty, health care, social preferences, and economic growth are just a few of the topics the class covers. “We think it’s pretty important that the first exposure to economics is via issues,” Duflo says. “If you first get exposed to economics via models, these models necessarily have to be very simplified, and then students get the idea that economics is a simplistic view of the world that can’t explain much.” Arguably, Duflo and Banerjee have been disproving that view throughout their careers. In 2003, the pair founded MIT’s Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab, a leading antipoverty research network that provides scientific evidence on what methods actually work to alleviate poverty — which enables governments and nongovernmental organizations to implement truly effective programs and social policies. And, in 2019 they won the Nobel Prize in economics (together with Michael Kremer of the University of Chicago) for their innovative work applying laboratory-style randomized, controlled trials to research a wide range of topics implicated in global poverty. “Super cool”

First-year Jean Billa, one of the students in 14.009, says, “Economics isn’t just about how money flows, but about how people react to certain events. That was an interesting discovery for me.”

It’s also precisely the lesson Banerjee and Duflo hoped students would take away from 14.009, a class that centers on weekly in-person discussions of the professors’ recorded lectures — many of which align with chapters in Banerjee and Duflo’s book “Good Economics for Hard Times” (Public Affairs, 2019). Classes typically start with a poll in which the roughly 100 enrolled students can register their views on that week’s topic. Then, students get to discuss the issue, says senior Dina Atia, teaching assistant for the class. Noting that she finds it “super cool” that Nobelists are teaching MIT’s first-year students, Atia points out that both Duflo and Banerjee have also made themselves available to chat with students after class. “They’re definitely extending themselves,” she says. “We want the students to get excited about economics so they want to know more,” says Banerjee, the Ford Foundation International Professor of Economics, “because this is a field that can help us address some of the biggest problems society faces.” Using natural experiments to test theories

Early in the term, for example, the topic was migration. In the lecture, Duflo points out that migration policies are often impacted by the fear that unskilled migrants will overwhelm a region, taking jobs from residents and demanding social services. Yet, migrant flows in normal years represent just 3 percent of the world population. “There is no flood. There is no vast movement of migrants,” she says. Duflo then explains that economists were able to learn a lot about migration thanks to a “natural experiment,” the Mariel boat lift. This 1980 event brought roughly 125,000 unskilled Cubans to Florida over a matter a months, enabling economists to study the impacts of a sudden wave of migration. Duflo says a look at real wages before and after the migration showed no significant impacts. “It was interesting to see that most theories about immigrants were not justified,” Billa says. “That was a real-life situation, and the results showed that even a massive wave of immigration didn’t change work in the city [Miami].”

Question assumptions, find the facts in data Since this is a broad survey course, there is always more to unpack. The goal, faculty say, is simply to help students understand the power of economics to explain and shape the world. “We are going so fast from topic to topic, I don’t expect them to retain all the information,” Duflo says. Instead, students are expected to gain an appreciation for a way of thinking. “Economics is about questioning everything — questioning assumptions you don’t even know are assumptions and being sophisticated about looking at data to uncover the facts.” To add impact, Duflo says she and Banerjee tie lessons to current events and dive more deeply into a few economic studies. One class, for example, focused on the unequal burden the Covid-19 pandemic has placed on different demographic groups and referenced research by Harvard University professor Marcella Alsan, who won a MacArthur Fellowship this fall for her work studying the impact of racism on health disparities.

Duflo also revealed that at the beginning of the pandemic, she suspected that mistrust of the health-care system could prevent Black Americans from taking certain measures to protect themselves from the virus. What she discovered when she researched the topic, however, was that political considerations outweighed racial influences as a predictor of behavior. “The lesson for you is, it’s good to question your assumptions,” she told the class. “Students should ideally understand, by the end of class, why it’s important to ask questions and what they can teach us about the effectiveness of policy and economic theory,” Banerjee says. “We want people to discover the range of economics and to understand how economists look at problems.”

Story by MIT SHASS Communications Editorial and design director: Emily Hiestand Senior writer: Kathryn O'Neill

Share this news article on:

Press mentions.

Prof. Esther Duflo will present her research on poverty reduction and her “proposal for a global minimum tax on billionaires and increased corporate levies to G-20 finance chiefs,” reports Andrew Rosati for Bloomberg. “The plan calls for redistributing the revenues to low- and middle-income nations to compensate for lives lost due to a warming planet,” writes Rosati. “It also adds to growing calls to raise taxes on the world’s wealthiest to help its most needy.”

Previous item Next item

Related Links

- Class 14.009 (Economics and Society’s Greatest Problems)

- Esther Duflo

- Abhijit Banerjee

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab

- Department of Economics

- Video: "Lighting the Path"

Related Topics

- Education, teaching, academics

- Climate change

- Immigration

- Social justice

- Health care

- School of Humanities Arts and Social Sciences

Related Articles

Popular new major blends technical skills and human-centered applications

Report: Economics drives migration from Central America to the U.S.

MIT economists Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee win Nobel Prize

More mit news.

Flying high to enable sustainable delivery, remote care

Read full story →

Professor Emeritus Ralph Gakenheimer, mobility planner and champion of international development, dies at 89

A recipe for zero-emissions fuel: Soda cans, seawater, and caffeine

Balancing economic development with natural resources protection

Three MIT professors named 2024 Vannevar Bush Fellows

Q&A: “As long as you have a future, you can still change it”

- More news on MIT News homepage →

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA, USA

- Map (opens in new window)

- Events (opens in new window)

- People (opens in new window)

- Careers (opens in new window)

- Accessibility

- Social Media Hub

- MIT on Facebook

- MIT on YouTube

- MIT on Instagram

Saturday, June 17, 2017

The importance of economics.

- What to produce? - Is it worth spending more on health care?

- How to produce? - Should we leave it to market forces or implement government regulations.

- For whom to produce? - How should we distribute resources, should we place higher income tax on the wealthiest in society?

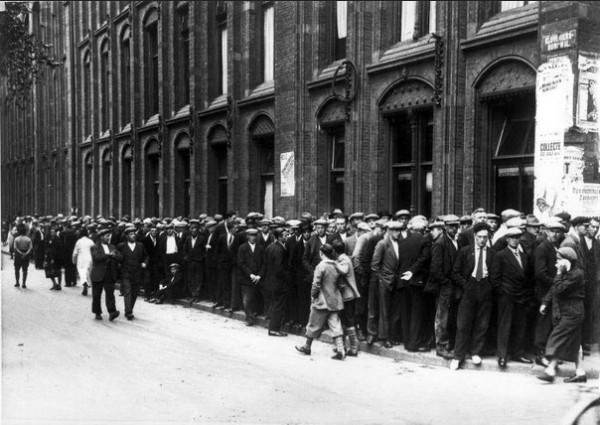

| Mass unemployment in the 1930s |

- Policies to reduce unemployment

- Policies to reduce inflation

| Market failure - stuck in traffic jam, breathing car fumes |

- The over production of negative externalities (e.g. pollution/congestion)

- The underproduction of goods with positive externalities (e.g. education, health care, public transport).

- Non-provision of Public Goods - (national defence, law and order)

- Tax negative externalities

- Subsidise public services like health care and education.

- Carbon Tax - should we implement a carbon tax to reduce global warming?

- Should we tax fatty foods?

- Efficiency v equality

- GDP and Happiness

- Economics - The Dismal Science

- How to deal/combat global warming?

- Does globalisation help or hinder developing countries?

- How to live in a society without oil?

15 comments:

a big hand of appluse for the writer of da topic who made it so easy to understand and absorbant. Mrs.Afaque...

this helped me a lot in my school project.a bit problem is there a filipino version?haha!

I really like the blog because of easy and focused approach that writer has used in simple and less words. Useful for those who just want a overview about economics.

very helpful and briefly detailed..thank you, writer.

this will help me 4 sure.. jejeje

your notes really helped me alot. i have my exam tomorrow and and i easily mugged up these notes.

waw! So nice...u realy helped me, thnx alot

thanks a lot to the writer...you just saved me from my prof's course.

Please elaborate on GDP Vs. Happiness?

Economics helps me to manage my money well when in school. thank you writer!

I will like to know how an economist is useful in an electoral decision or organization

I love the blog because the writer explained the importance of economics in simple terms and it helped me a lot with my school assignment

A definition of what an economy means is helpful in understanding the importance of economic systems. The economy is a structured system that uses production, distribution, and services to create a stable environment. Therefore, an economic system is the production, consumption of goods and services with a set of institutions and social relations to create a balanced society. There are a few different types of economic systems such as capitalist, social list, mixed economies and communism. Economic systems do not have to be on a global scale or even a national scale. For example, economic systems such as distributism, the Japanese system, social market economy and Georgism are some of the available options out there. These systems may be state or private. A few are cooperative ownerships. A mixed economy is considered one with a mix of private activity and state planning. The best gauge for the importance of economic systems is balance. The world requires a balance that will ensure the survival of the system. For example, the human race has to find balance with food, shelter, water, and even income in order to survive. Income is necessary in order to buy shelter, food, and other necessities of life. Though money did not exist in the past, we have an economic system that demands income be included in our survival. The UK has a capitalist system which the government maintains order to sustain life in the UK. Since society can be part of economic systems, it is also an important factor in people getting along in a balance of nature. Humans are social by nature therefore an economy that promotes this social interaction will also increase the effectiveness of the economic system in place and the balance of one's life.

thanks man! this helps me for my report tomorrow..

Very easy to understand Thanks

Post a Comment

The importance of economics

Readers Question: What is the importance of economics?

Economics is concerned with the optimal distribution of resources in society. The subject involves

- Understanding what happens in markets and the macroeconomy.

- Examining statistics about the state of the economy and explaining their significance

- Understanding different policy options and evaluating their likely outcomes.

Examples of the importance of economics

- Dealing with a shortage of raw materials. Economics provides a mechanism for looking at possible consequences as we run short of raw materials such as gas and oil. See also: Effects of a world without oil.

- How to distribute resources in society. To what extent should we redistribute income in society? Is inequality necessary to create economic incentives or does inequality create unnecessary economic and social problems?

- To what extent should the government intervene in the economy? A critical divide in economics is the extent to which the government should intervene in the economy. Free market economists, like Hayek and Friedman, argue for limited government intervention and free markets. Other economists, like Stiglitz or Krugman, argue government intervention can overcome inequality and the underprovision of public goods. For example – should the government provide health care free at the point of use or is it more efficient to encourage private health care? See also: To what extent should the government intervene in the economy?

- The principle of opportunity cost. Politicians win elections by promising more spending and cutting taxes. This is because lower taxes and more spending is what voters want to hear. However, an economist will be aware that everything has an opportunity cost. Spend more on subsidising free university education, and it means higher taxes and lower spending elsewhere. Giving students £4,000 a year to spend at university may be a noble ideal. But, is it the best use of public money? Are there better uses of money, such as spending on primary education? See: Opportunity Cost

- Social efficiency. The free market leads to countless examples of market failure. I feel one of the best uses of economics is to provide solutions to overcoming market failure. For example, driving into the centre of town creates negative externalities such as pollution and congestion. There is overconsumption. An economist can suggest a tax on driving into towns to internalise the externality. Of course, new taxes are not popular, but, it might provide a better solution for society. You may not want to pay £10 a week to drive into a city centre. But, if it saved you two hours of sitting in a jam, then maybe you would be much happier to pay it.

- Knowledge and understanding. One of the principal jobs for economists is to understand what is happening in the economy and investigate reasons for poverty, unemployment and low economic growth. For example, in a political debate such as – Should, the UK leave the EU? There are many emotional arguments made about immigration. Economic studies can try and evaluate the costs and benefits of free movement of labour. Economic studies can try to examine the economic effects of immigration . This can help people make a decision about political issues.

- How to deal with an economic crisis. In the 1930s, the Wall Street Crash precipitated a significant rise in unemployment. There was a debate on how to respond. Many western governments increased taxes, tariffs and benefits. This response caused John M. Keynes to develop a new branch of economics – focused on dealing with a persistent recession.

- Evaluation. Economics is not a definitive science like Maths. Because of many unknown variables, it is impossible to be definitive about outcomes, but a good economist will be aware the result depends on different variables, and there are different potential outcomes. This should help avoid an overly ideological approach. For example, a government may have the philosophy ‘free markets are always best’, but an economist would be aware of a more nuanced view that in some markets, like health care, transport, government intervention can overcome market failure and improve welfare. But, at the same time, it doesn’t mean state intervention is always best.

- Behavioural economics Why do people behave as they do? Can governments subtly nudge people into better behaviour, e.g. banning cigarette advertising? Are we subject to bias and irrational behaviour? For example, can we be sucked along by a bubble and lose a fortune on the stock market? Behavioural economics examines the reasons why we make decisions. See: Behavioural economics .

- Applying economics in everyday life . Modern economists have examined economic forces behind everyday social issues. For example, Gary Becker argued that most crime could be explained by economic costs and benefits. See: Applying economics in everyday life .

Limitations of Economics

Does economics place too much value on rationality, utility maximisation and profit maximisation? That is the work of behavioural economics who are more critical of the limitations of the traditional economic theory.

Does GDP measure living standards?

Related reading

- Economic growth and happiness

- A frivolous look at ten reasons to study economics

- Winners and losers from globalisation

- Economic instability

Last updated: 10th March 2020, Tejvan Pettinger , www.economicshelp.org, Oxford, UK

58 thoughts on “The importance of economics”

It reals helps

Yeah that’s right good job I agree with you about opportunity cost of politicians…🤣🤣🤣

Economic is the social science to a group of social science to other subjects in the same group are religious studies and it really good to individuals needs 👍👍👍👍😊😊😊

Economics is the study of manage individuals, groups, and nations’ unlimited demand and wants with limited resources. The study of economics not only expands the skills required to understand multifaceted markets but also comes left with sturdy analytical and problem–solving skills and with additional business expertise necessary to be successful in the professional globe village even though Economics is useful for professionals in all industries even not only in business

Dear honourable sir I need economics support to establish an new business which can stand me an happy life with humanity and be upon to helping others to establish their life with an modernity in future

Yes health crisis is common problem in our life everyday,I have been trying personally to do an new plan that’s save people’s health riscks,for this people’s need to understand what is health? health mean a human body and minds protect from disease,what is disseas? disease is one kinds of effect in our health,by various virus,and disseas,how we protect us,we protect us from disseas by our understanding what feeling in our body health,and what it’s harm,what kinds of disseas?then we personally try to stop this disseas,then a man can safe his/her health.

I have small amount of money with me but I fail to identify business to start please I need some help coz I don’t know what to do next since there is risks and uncertainty in business

start selling food if you can cook its pretty low risk if you get into events

Very good to to analyze this importance of economic

Comments are closed.

How Does Economics Affect Our Daily Lives?

What Are the Causes of Economic Decline?

While the word "economics" may conjure up a view of Wall Street trading or a college course, it is actually a term that relates to everyday life in many ways. Economics is a social science that deals with the life-cycle of goods and services. It is a study of how innovation and finance revolve around the basic human needs and wants in order to provide products and services to the public. Understanding how economics relates to society is critical to business success but also relates everyday life. Consumers confident in the economy are more likely to spend while a shaky economy may be matched with consumers less willing to spend money. Taking a closer look at supply and cost, consumer loans, consumer confidence and debt and spending helps analyze the overall economic climate and outlook.

Supply and Cost

Economics has an enormous effect on the daily lives and wallets of all people, even if they aren't actually involved in economic studies. The principles of supply and demand play out every day for people making purchasing decisions on goods and services as well as in them keeping or finding employment. Changes in circumstances, regulations or government mandates on any part of an industry's economic structure can create a ripple effect of price changes through multiple industries to the end consumer. For example, if regulations change distribution channels, that can increase the cost of producing goods which in turn, forces retailers to raise the price of goods to still have an economic profit.

Consumer Confidence

When the consumers' confidence in the economy is low, they restrain spending, starting with dining out and going to the movies. These industries have wage workers that lose income when hours are cut due to reduced business. Soon, everyone feels the pinch perpetuated by fewer open retail check-out lines to fewer police on the streets. The Gallup Consumer Confidence poll measures ongoing consumer economic confidence by asking Americans to answer questions on their view of current economic conditions and if they think conditions are improving or declining from a point in the recent past.

Debt and Spending

CNN Money reports that consumer spending fuels two-thirds of the United States economic activity, much of which was based on credit prior to 2008. The 2008 to 2009 financial collapse led banks to tighten consumer lending, and consumers began paying down debt rather then spending as usual. Reducing personal debt is good on the individual level, but this reaction also kept employment in a slump and reduced the disposable income of households and individuals. When individuals see the economy as being stronger, they are more apt to spend money in stores and on larger purchases like homes or vehicles. Debt often comes with those purchases beyond day-to-day spending. When consumers return to feeling the economy is rebounding, they are apt to take on more debt with less fear of an economic collapse.

Related Articles

Cons of Supply Side Economics

Managerial Economics Topics

Negative Effects of Tariffs

Macroeconomic Paper Research Topics

Topics for A Human Relations Research Paper

Difference Between Deflation, Recession & Depression

How to Calculate Total Cost in Economics

Advantages & Disadvantages on College Students With Credit Cards

- CNNMoney: Consumer Confidence Ticks up in October (2010)

- RasmussenReports: Discover ® Consumer Spending Monitor (SM) Rises 1.8 Points in October

- BusinessInsider: The New American Consumer is Terrified of Debt Even as the Economy Grows

- Economics Help: Applying Economics in Everyday Life

- Gallup: U.S. Economic Confidence Index

Cynthia Clark began writing professionally in 2004. Her work experience includes all areas of small-business development, real-estate investments, home remodeling and Web development. Clark is skilled in a number of design disciplines from digital graphics to interior design. Her diverse background and commonsense problem-solving skills allow her to tackle a variety of topics as an online writer.

1.1 What Is Economics, and Why Is It Important?

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss the importance of studying economics

- Explain the relationship between production and division of labor

- Evaluate the significance of scarcity

Economics is the study of how humans make decisions in the face of scarcity. These can be individual decisions, family decisions, business decisions or societal decisions. If you look around carefully, you will see that scarcity is a fact of life. Scarcity means that human wants for goods, services and resources exceed what is available. Resources, such as labor, tools, land, and raw materials are necessary to produce the goods and services we want but they exist in limited supply. Of course, the ultimate scarce resource is time- everyone, rich or poor, has just 24 expendable hours in the day to earn income to acquire goods and services, for leisure time, or for sleep. At any point in time, there is only a finite amount of resources available.

Think about it this way: In 2015 the labor force in the United States contained over 158 million workers, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The total land area was 3,794,101 square miles. While these are certainly large numbers, they are not infinite. Because these resources are limited, so are the numbers of goods and services we produce with them. Combine this with the fact that human wants seem to be virtually infinite, and you can see why scarcity is a problem.

Introduction to FRED

Data is very important in economics because it describes and measures the issues and problems that economics seek to understand. A variety of government agencies publish economic and social data. For this course, we will generally use data from the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank's FRED database. FRED is very user friendly. It allows you to display data in tables or charts, and you can easily download it into spreadsheet form if you want to use the data for other purposes. The FRED website includes data on nearly 400,000 domestic and international variables over time, in the following broad categories:

- Money, Banking & Finance

- Population, Employment, & Labor Markets (including Income Distribution)

- National Accounts (Gross Domestic Product & its components), Flow of Funds, and International Accounts

- Production & Business Activity (including Business Cycles)

- Prices & Inflation (including the Consumer Price Index, the Producer Price Index, and the Employment Cost Index)

- International Data from other nations

- U.S. Regional Data

- Academic Data (including Penn World Tables & NBER Macrohistory database)

For more information about how to use FRED, see the variety of videos on YouTube starting with this introduction.

If you still do not believe that scarcity is a problem, consider the following: Does everyone require food to eat? Does everyone need a decent place to live? Does everyone have access to healthcare? In every country in the world, there are people who are hungry, homeless (for example, those who call park benches their beds, as Figure 1.2 shows), and in need of healthcare, just to focus on a few critical goods and services. Why is this the case? It is because of scarcity. Let’s delve into the concept of scarcity a little deeper, because it is crucial to understanding economics.

The Problem of Scarcity

Think about all the things you consume: food, shelter, clothing, transportation, healthcare, and entertainment. How do you acquire those items? You do not produce them yourself. You buy them. How do you afford the things you buy? You work for pay. If you do not, someone else does on your behalf. Yet most of us never have enough income to buy all the things we want. This is because of scarcity. So how do we solve it?

Visit this website to read about how the United States is dealing with scarcity in resources.

Every society, at every level, must make choices about how to use its resources. Families must decide whether to spend their money on a new car or a fancy vacation. Towns must choose whether to put more of the budget into police and fire protection or into the school system. Nations must decide whether to devote more funds to national defense or to protecting the environment. In most cases, there just isn’t enough money in the budget to do everything. How do we use our limited resources the best way possible, that is, to obtain the most goods and services we can? There are a couple of options. First, we could each produce everything we each consume. Alternatively, we could each produce some of what we want to consume, and “trade” for the rest of what we want. Let’s explore these options. Why do we not each just produce all of the things we consume? Think back to pioneer days, when individuals knew how to do so much more than we do today, from building their homes, to growing their crops, to hunting for food, to repairing their equipment. Most of us do not know how to do all—or any—of those things, but it is not because we could not learn. Rather, we do not have to. The reason why is something called the division and specialization of labor , a production innovation first put forth by Adam Smith ( Figure 1.3 ) in his book, The Wealth of Nations .

The Division of and Specialization of Labor

The formal study of economics began when Adam Smith (1723–1790) published his famous book The Wealth of Nations in 1776. Many authors had written on economics in the centuries before Smith, but he was the first to address the subject in a comprehensive way. In the first chapter, Smith introduces the concept of division of labor , which means that the way one produces a good or service is divided into a number of tasks that different workers perform, instead of all the tasks being done by the same person.

To illustrate division of labor, Smith counted how many tasks went into making a pin: drawing out a piece of wire, cutting it to the right length, straightening it, putting a head on one end and a point on the other, and packaging pins for sale, to name just a few. Smith counted 18 distinct tasks that different people performed—all for a pin, believe it or not!

Modern businesses divide tasks as well. Even a relatively simple business like a restaurant divides the task of serving meals into a range of jobs like top chef, sous chefs, less-skilled kitchen help, servers to wait on the tables, a greeter at the door, janitors to clean up, and a business manager to handle paychecks and bills—not to mention the economic connections a restaurant has with suppliers of food, furniture, kitchen equipment, and the building where it is located. A complex business like a large manufacturing factory, such as the shoe factory ( Figure 1.4 ), or a hospital can have hundreds of job classifications.

Why the Division of Labor Increases Production

When we divide and subdivide the tasks involved with producing a good or service, workers and businesses can produce a greater quantity of output. In his observations of pin factories, Smith noticed that one worker alone might make 20 pins in a day, but that a small business of 10 workers (some of whom would need to complete two or three of the 18 tasks involved with pin-making), could make 48,000 pins in a day. How can a group of workers, each specializing in certain tasks, produce so much more than the same number of workers who try to produce the entire good or service by themselves? Smith offered three reasons.

First, specialization in a particular small job allows workers to focus on the parts of the production process where they have an advantage. (In later chapters, we will develop this idea by discussing comparative advantage .) People have different skills, talents, and interests, so they will be better at some jobs than at others. The particular advantages may be based on educational choices, which are in turn shaped by interests and talents. Only those with medical degrees qualify to become doctors, for instance. For some goods, geography affects specialization. For example, it is easier to be a wheat farmer in North Dakota than in Florida, but easier to run a tourist hotel in Florida than in North Dakota. If you live in or near a big city, it is easier to attract enough customers to operate a successful dry cleaning business or movie theater than if you live in a sparsely populated rural area. Whatever the reason, if people specialize in the production of what they do best, they will be more effective than if they produce a combination of things, some of which they are good at and some of which they are not.

Second, workers who specialize in certain tasks often learn to produce more quickly and with higher quality. This pattern holds true for many workers, including assembly line laborers who build cars, stylists who cut hair, and doctors who perform heart surgery. In fact, specialized workers often know their jobs well enough to suggest innovative ways to do their work faster and better.

A similar pattern often operates within businesses. In many cases, a business that focuses on one or a few products (sometimes called its “ core competency ”) is more successful than firms that try to make a wide range of products.

Third, specialization allows businesses to take advantage of economies of scale , which means that for many goods, as the level of production increases, the average cost of producing each individual unit declines. For example, if a factory produces only 100 cars per year, each car will be quite expensive to make on average. However, if a factory produces 50,000 cars each year, then it can set up an assembly line with huge machines and workers performing specialized tasks, and the average cost of production per car will be lower. The ultimate result of workers who can focus on their preferences and talents, learn to do their specialized jobs better, and work in larger organizations is that society as a whole can produce and consume far more than if each person tried to produce all of their own goods and services. The division and specialization of labor has been a force against the problem of scarcity.

Trade and Markets

Specialization only makes sense, though, if workers can use the pay they receive for doing their jobs to purchase the other goods and services that they need. In short, specialization requires trade.

You do not have to know anything about electronics or sound systems to play music—you just buy an iPod or MP3 player, download the music, and listen. You do not have to know anything about artificial fibers or the construction of sewing machines if you need a jacket—you just buy the jacket and wear it. You do not need to know anything about internal combustion engines to operate a car—you just get in and drive. Instead of trying to acquire all the knowledge and skills involved in producing all of the goods and services that you wish to consume, the market allows you to learn a specialized set of skills and then use the pay you receive to buy the goods and services you need or want. This is how our modern society has evolved into a strong economy.

Why Study Economics?

Now that you have an overview on what economics studies, let’s quickly discuss why you are right to study it. Economics is not primarily a collection of facts to memorize, although there are plenty of important concepts to learn. Instead, think of economics as a collection of questions to answer or puzzles to work. Most importantly, economics provides the tools to solve those puzzles.

Consider the complex and critical issue of education barriers on national and regional levels, which affect millions of people and result in widespread poverty and inequality. Governments, aid organizations, and wealthy individuals spend billions of dollars each year trying to address these issues. Nations announce the revitalization of their education programs; tech companies donate devices and infrastructure, and celebrities and charities build schools and sponsor students. Yet the problems remain, sometimes almost as pronounced as they were before the intervention. Why is that the case? In 2019, three economists—Esther Duflo, Abhijit Banerjee, and Michael Kremer—were awarded the Nobel Prize for their work to answer those questions. They worked diligently to break the widespread problems into smaller pieces, and experimented with small interventions to test success. The award citation credited their work with giving the world better tools and information to address poverty and improve education. Esther Duflo, who is the youngest person and second woman to win the Nobel Prize in Economics, said, "We believed that like the war on cancer, the war on poverty was not going to be won in one major battle, but in a series of small triumphs. . . . This work and the culture of learning that it fostered in governments has led to real improvement in the lives of hundreds of millions of poor people.”

As you can see, economics affects far more than business. For example:

- Virtually every major problem facing the world today, from global warming, to world poverty, to the conflicts in Syria, Afghanistan, and Somalia, has an economic dimension. If you are going to be part of solving those problems, you need to be able to understand them. Economics is crucial.

- It is hard to overstate the importance of economics to good citizenship. You need to be able to vote intelligently on budgets, regulations, and laws in general. When the U.S. government came close to a standstill at the end of 2012 due to the “fiscal cliff,” what were the issues? Did you know?

- A basic understanding of economics makes you a well-rounded thinker. When you read articles about economic issues, you will understand and be able to evaluate the writer’s argument. When you hear classmates, co-workers, or political candidates talking about economics, you will be able to distinguish between common sense and nonsense. You will find new ways of thinking about current events and about personal and business decisions, as well as current events and politics.

The study of economics does not dictate the answers, but it can illuminate the different choices.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Steven A. Greenlaw, David Shapiro, Daniel MacDonald

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Principles of Economics 3e

- Publication date: Dec 14, 2022

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/1-1-what-is-economics-and-why-is-it-important

© Jan 23, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Topic 1: Introductory Concepts and Models

1.1 What Is Economics, and Why Is It Important?

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss the importance of studying economics

- Explain the relationship between production and division of labor

- Evaluate the significance of scarcity

At its core, Economics is the study of how humans make decisions in the face of scarcity. These can be individual decisions, family decisions, business decisions or societal decisions. If you look around carefully, you will see that scarcity is a fact of life. Scarcity means that human wants for goods, services and resources exceed what is available. Resources, such as labor, tools, land, and raw materials are necessary to produce the goods and services we want but they exist in limited supply. Of course, the ultimate scarce resource is time – everyone, rich or poor, has just 24 hours in the day to try to acquire the goods they want. At any point in time, there is only a finite amount of resources available.

Think about it this way: In 2016, the labor force in Canada contained 19.4 million workers, according to Statistics Canada. The total area of the Canada is 9.99 million square kilometres. These are large numbers for such crucial resources, however, they are limited. Because these resources are limited, so are the numbers of goods and services we produce with them. Combine this with the fact that human wants seem to be virtually infinite, and you can see why scarcity is a problem.

If you still do not believe that scarcity is a problem, consider the following: Does everyone need food to eat? Does everyone need a decent place to live? Does everyone have access to healthcare? In every country in the world, there are people who are hungry, homeless, and in need of healthcare, just to focus on a few critical goods and services. Why is this the case? It is because of scarcity. Let’s delve into the concept of scarcity a little deeper, because it is crucial to understanding economics.

The Problem of Scarcity

Think about all the things you consume: food, shelter, clothing, transportation, healthcare, and entertainment. How do you acquire those items? You do not produce them yourself. You buy them. How do you afford the things you buy? You work for a wage. Or if you do not, someone else does on your behalf. Yet most of us never have enough to buy all the things we want. This is because of scarcity. So how do we solve the problem of scarcity?

Every society, at every level, must make choices about how to use its resources. Families must decide whether to spend their money on a new car or a vacation. Towns must choose whether to put more of the budget into police and fire protection or into the school system. Nations must decide whether to devote more funds to national defence or to protecting the environment. In most cases, there just isn’t enough money in the budget to do everything. So why do we not each just produce all of the things we consume? The simple answer is most of us do not know how, but that is not the main reason. Think back to pioneer days, when individuals knew how to do many more practical tasks than we do today, from building their homes, to growing crops, to hunting for food, or repairing their equipment. Most of us do not know how to do all—or any—of those things. It is not because we could not learn. Rather, we do not have to. The reason why is something called the division and specialization of labor , a production innovation first put forth by Adam Smith in his book, The Wealth of Nations (See Figure 2).

The Division of and Specialization of Labor

The formal study of economics began when Adam Smith (1723–1790) published his famous book The Wealth of Nations in 1776. Many authors had written on economics in the centuries before Smith, but he was the first to address the subject in a comprehensive way. In the first chapter, Smith introduces the division of labor , which means that the way a good or service is produced is divided into a number of tasks that are performed by different workers, instead of all the tasks being done by the same person.

To illustrate the division of labor, Smith counted how many tasks went into making a pin: drawing out a piece of wire, cutting it to the right length, straightening it, putting a head on one end and a point on the other, and packaging pins for sale, to name just a few. Smith counted 18 distinct tasks that were often done by different people—all for a pin!

Modern businesses divide tasks as well. Even a relatively simple business like a restaurant divides up the task of serving meals into a range of jobs like top chef, sous chefs, kitchen help, servers to wait on the tables, a greeter at the door, janitors to clean up, and a business manager to handle paychecks and bills—not to mention the economic connections a restaurant has with suppliers of food, furniture, kitchen equipment, and the building where it is located. A complex business like a large manufacturing factory, such as the shoe factory shown in Figure 3 can have hundreds of job classifications.

Why the Division of Labor Increases Production

When the tasks involved with producing a good or service are divided and subdivided, workers and businesses can produce a greater quantity of output. In his observations of pin factories, Smith observed that one worker alone might make 20 pins in a day, but that a small business of 10 workers (some of whom would need to do two or three of the 18 tasks involved with pin-making), could make 48,000 pins in a day. How can a group of workers, each specializing in certain tasks, produce so much more than the same number of workers who try to produce the entire good or service by themselves? Smith offered three reasons.

First, specialization in a particular small job allows workers to focus on the parts of the production process where they have an advantage. (In later topics, we will develop this idea by discussing comparative advantage .) People have different skills, talents, and interests, so they will be better at some jobs than at others. The particular advantages may be based on educational choices, which are in turn shaped by interests and talents. Only those with medical degrees qualify to become doctors, for instance. For some goods, specialization will be affected by geography—it is easier to be a wheat farmer in Saskatchewan than in British Columbia, but easier to run a tourist hotel in BC than in Saskatchewan. If you live in or near a big city, it is easier to attract enough customers to operate a successful dry cleaning business or movie theater than if you live in a sparsely populated rural area. Whatever the reason, if people specialize in the production of what they do best, they will be more productive than if they produce a combination of things, some of which they are good at and some of which they are not.

Second, workers who specialize in certain tasks often learn to produce more quickly and with higher quality. This pattern holds true for many workers, including assembly line laborers who build cars, stylists who cut hair, and doctors who perform heart surgery. In fact, specialized workers often know their jobs well enough to suggest innovative ways to do their work faster and better.

Third, specialization allows businesses to take advantage of economies of scale , which means that for many goods, as the level of production increases, the average cost of producing each individual unit declines. For example, if a factory produces only 100 cars per year, each car will be quite expensive to make on average. However, if a factory produces 50,000 cars each year, then it can set up an assembly line with huge machines and workers performing specialized tasks, and the average cost of production per car will be lower. The ultimate result of workers who can focus on their preferences and talents, learn to do their specialized jobs better, and work in larger organizations is that society as a whole can produce and consume far more than if each person tried to produce all of their own goods and services. The division and specialization of labor has been a force against the problem of scarcity.

Trade and Markets

However, specialization only makes sense if workers can use the pay they receive for doing their jobs to purchase the other goods and services that they need. In short, specialization requires trade.

You do not have to know anything about electronics or sound systems to play music—you just buy a phone, download the music and listen. You do not have to know anything about artificial fibers or the construction of sewing machines to wear a jacket—you just buy the jacket and wear it. You do not need to know anything about internal combustion engines to operate a car—you just get in and drive. Instead of trying to acquire all the knowledge and skills involved in producing all of the goods and services that you wish to consume, the market allows you to learn a specialized set of skills and then use the pay you receive to buy the goods and services you need or want. This is how our modern society has evolved into a strong economy.

Why Study Economics?

Now that we have an overview of what economics studies, let’s quickly discuss why you are right to study it. Economics is not primarily a collection of facts to be memorized, though there are plenty of important concepts to be learned. Instead, economics is better thought of as a collection of questions to be answered or puzzles to be worked out. Most important, economics provides the tools to work out those puzzles. If you have yet to be been bitten by the economics “bug,” here are some other reasons why you should study economics:

- Virtually every major problem facing the world today, from global warming, to world poverty, to the conflicts in Syria, Afghanistan, and Somalia, has an economic dimension. If you are going to be part of solving those problems, you need to be able to understand them. Economics is crucial.

- It is hard to overstate the importance of economics to good citizenship. You need to be able to vote intelligently on budgets, regulations, and laws in general.

- A basic understanding of economics makes you a well-rounded thinker. When you read articles about economic issues, you will understand and be able to evaluate the writer’s argument. When you hear classmates, co-workers, or political candidates talking about economics, you will be able to distinguish between common sense and nonsense. You will find new ways of thinking about current events and about personal and business decisions, as well as current events and politics.

The study of economics does not dictate the answers, but it can illuminate the different choices.

Economics seeks to understand and address the problem of scarcity, which is when human wants for goods and services exceed the available supply. A modern economy displays a division of labor, in which people earn income by specializing in what they produce and then use that income to purchase the products they need or want. The division of labor allows individuals and firms to specialize and to produce more for several reasons: a) It allows the agents to focus on areas of advantage due to natural factors and skill levels; b) It encourages the agents to learn and invent; c) It allows agents to take advantage of economies of scale. Division and specialization of labor only work when individuals can purchase what they do not produce in markets. Learning about economics helps you understand the major problems facing the world today, prepares you to be a good citizen, and helps you become a well-rounded thinker.

Principles of Microeconomics Copyright © 2017 by University of Victoria is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Feedback/errata.

Comments are closed.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1.1 What Is Economics, and Why Is It Important?

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss the importance of studying economics

- Explain the relationship between production and division of labor

- Evaluate the significance of scarcity

Economics is the study of how humans make decisions in the face of scarcity. These can be individual decisions, family decisions, business decisions or societal decisions. If you look around carefully, you will see that scarcity is a fact of life. Scarcity means that human wants for goods, services and resources exceed what is available. Resources, such as labor, tools, land, and raw materials are necessary to produce the goods and services we want but they exist in limited supply. Of course, the ultimate scarce resource is time- everyone, rich or poor, has just 24 hours in the day to try to acquire the goods they want. At any point in time, there is only a finite amount of resources available.

Think about it this way: the total land area of the main Hawaiian islands is only 10,931 square miles. Because land and other natural resources are limited, so are the numbers of goods and services we can produce with them. Combine this with the fact that human wants seem to be virtually infinite, and you can see why scarcity is a problem.

If you still do not believe that scarcity is a problem, consider the following: Does everyone need food to eat? Does everyone need a decent place to live? Does everyone have access to healthcare? In Hawaiʻi there are people who are hungry, homeless, and in need of healthcare, just to focus on a few critical goods and services. Why is this the case? It is because of scarcity. Let’s delve into the concept of scarcity a little deeper, because it is crucial to understanding economics.

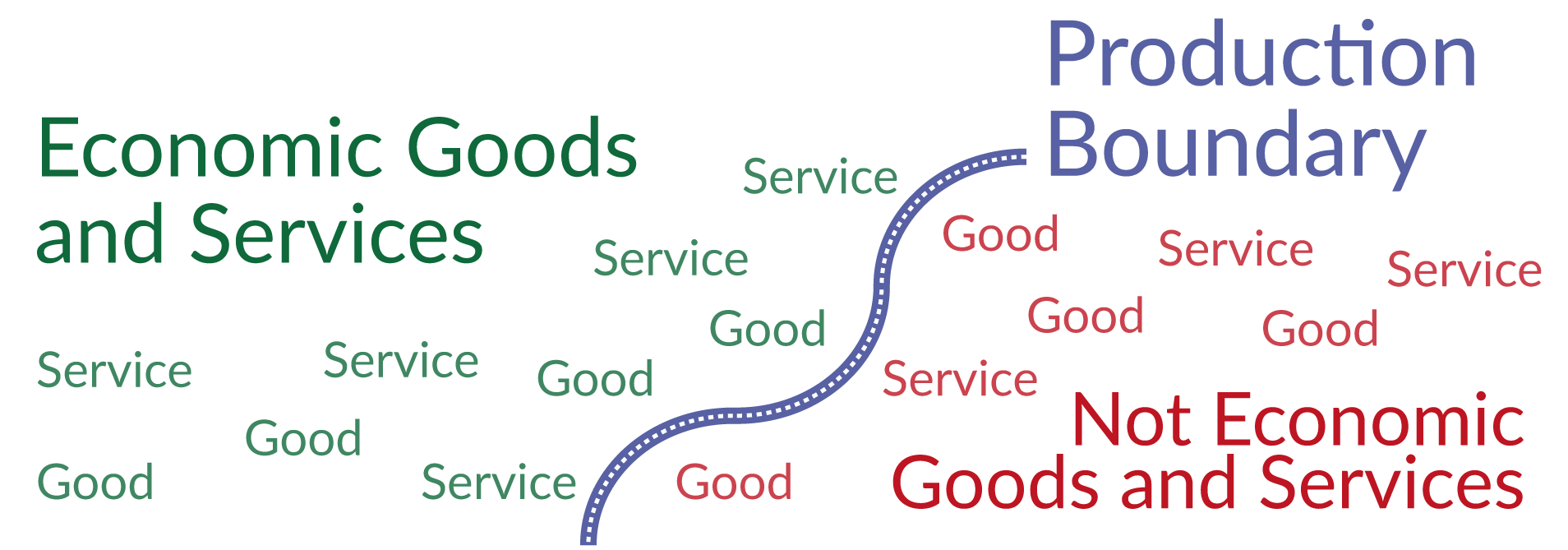

What is a good and what is a service?

Goods have a physical tangible presence, for example, a pizza or a scissors. Services have no physical tangible presence but have economic value (people are willing to pay to get this service). Examples of services include the delivery of a pizza or getting your hair cut.

Only around 20% of workers in the US work at jobs where they produce goods. The percentage is even smaller in Hawaiʻi: only 4% of workers in Hawaiʻi produce goods! What are the main services produced in Hawaiʻi and what are the main goods?

The Problem of Scarcity

Think about all the things you consume: food, shelter, clothing, transportation, healthcare, and entertainment. How do you acquire those items? You do not produce them yourself. You buy them. How do you afford the things you buy? You work for pay. Or if you do not, someone else does on your behalf. Yet most of us never have enough to buy all the things we want. This is because of scarcity. So how do we solve it?

Visit this website to read about how the United States is dealing with scarcity in resources.

Every society, at every level, must make choices about how to use its resources. Families must decide whether to spend their money on a new car or a fancy vacation. Towns must choose whether to put more of the budget into police and fire protection or into the school system. Nations must decide whether to devote more funds to national defense or to protecting the environment. In most cases, there just isn’t enough money in the budget to do everything. So why do we not each just produce all of the things we consume? The simple answer is most of us do not know how, but that is not the main reason. (When you study economics, you will discover that the obvious choice is not always the right answer—or at least the complete answer. Studying economics teaches you to think in a different of way.) Think back to pioneer days, when individuals knew how to do so much more than we do today, from building their homes, to growing their crops, to hunting for food, to repairing their equipment. Most of us do not know how to do all—or any—of those things. It is not because we could not learn. Rather, we do not have to. The reason why is something called the division and specialization of labor , a production innovation first put forth by Adam Smith in his book, The Wealth of Nations .

The Division of and Specialization of Labor

The formal study of economics began when Adam Smith (1723–1790) published his famous book The Wealth of Nations in 1776. Many authors had written on economics in the centuries before Smith, but he was the first to address the subject in a comprehensive way. In the first chapter, Smith introduces the division of labor , which means that the way a good or service is produced is divided into a number of tasks that are performed by different workers, instead of all the tasks being done by the same person.

To illustrate the division of labor, Smith counted how many tasks went into making a pin: drawing out a piece of wire, cutting it to the right length, straightening it, putting a head on one end and a point on the other, and packaging pins for sale, to name just a few. Smith counted 18 distinct tasks that were often done by different people—all for a pin, believe it or not!

Modern businesses divide tasks as well. Even a relatively simple business like a restaurant divides up the task of serving meals into a range of jobs like top chef, sous chefs, less-skilled kitchen help, servers to wait on the tables, a greeter at the door, janitors to clean up, and a business manager to handle paychecks and bills—not to mention the economic connections a restaurant has with suppliers of food, furniture, kitchen equipment, and the building where it is located (check out the video below). A complex business like a large manufacturing factory or a hospital can have hundreds of job classifications.

The Division of Labor at work at Marukame Udon in Waikiki:

Why the Division of Labor Increases Production

When the tasks involved with producing a good or service are divided and subdivided, workers and businesses can produce a greater quantity of output. In his observations of pin factories, Smith observed that one worker alone might make 20 pins in a day, but that a small business of 10 workers (some of whom would need to do two or three of the 18 tasks involved with pin-making), could make 48,000 pins in a day. How can a group of workers, each specializing in certain tasks, produce so much more than the same number of workers who try to produce the entire good or service by themselves? Smith offered three reasons.

First, specialization in a particular small job allows workers to focus on the parts of the production process where they have an advantage. (In later chapters, we will develop this idea by discussing comparative advantage .) People have different skills, talents, and interests, so they will be better at some jobs than at others. The particular advantages may be based on educational choices, which are in turn shaped by interests and talents. Only those with medical degrees qualify to become doctors, for instance. For some goods, specialization will be affected by geography—it is easier to be a wheat farmer in North Dakota than in Florida, but easier to run a tourist hotel in Florida than in North Dakota. If you live in or near a big city, it is easier to attract enough customers to operate a successful dry cleaning business or movie theater than if you live in a sparsely populated rural area. Whatever the reason, if people specialize in the production of what they do best, they will be more productive than if they produce a combination of things, some of which they are good at and some of which they are not.

Second, workers who specialize in certain tasks often learn to produce more quickly and with higher quality. This pattern holds true for many workers, including assembly line laborers who build cars, stylists who cut hair, and doctors who perform heart surgery. In fact, specialized workers often know their jobs well enough to suggest innovative ways to do their work faster and better.

A similar pattern often operates within businesses. In many cases, a business that focuses on one or a few products (sometimes called its “ core competency ”) is more successful than firms that try to make a wide range of products.

Third, specialization allows businesses to take advantage of economies of scale , which means that for many goods, as the level of production increases, the average cost of producing each individual unit declines. For example, if a factory produces only 100 cars per year, each car will be quite expensive to make on average. However, if a factory produces 50,000 cars each year, then it can set up an assembly line with huge machines and workers performing specialized tasks, and the average cost of production per car will be lower. The ultimate result of workers who can focus on their preferences and talents, learn to do their specialized jobs better, and work in larger organizations is that society as a whole can produce and consume far more than if each person tried to produce all of their own goods and services. The division and specialization of labor has been a force against the problem of scarcity.

Trade and Markets

Specialization only makes sense, though, if workers can use the pay they receive for doing their jobs to purchase the other goods and services that they need. In short, specialization requires trade.

You do not have to know anything about electronics or sound systems to play music—you just buy an iPod or MP3 player, download the music and listen. You do not have to know anything about artificial fibers or the construction of sewing machines if you need a jacket—you just buy the jacket and wear it. You do not need to know anything about internal combustion engines to operate a car—you just get in and drive. Instead of trying to acquire all the knowledge and skills involved in producing all of the goods and services that you wish to consume, the market allows you to learn a specialized set of skills and then use the pay you receive to buy the goods and services you need or want. This is how our modern society has evolved into a strong economy.

Why Study Economics?

Now that we have gotten an overview on what economics studies, let’s quickly discuss why you are right to study it. Economics is not primarily a collection of facts to be memorized, though there are plenty of important concepts to be learned. Instead, economics is better thought of as a collection of questions to be answered or puzzles to be worked out. Most important, economics provides the tools to work out those puzzles. If you have yet to be been bitten by the economics “bug,” there are other reasons why you should study economics.

- Virtually every major problem facing the world today, from global warming, to world poverty, to the conflicts in Syria, Afghanistan, and Somalia, has an economic dimension. If you are going to be part of solving those problems, you need to be able to understand them. Economics is crucial.

- It is hard to overstate the importance of economics to good citizenship. You need to be able to vote intelligently on budgets, regulations, and laws in general. When the U.S. government came close to a standstill at the end of 2012 due to the “fiscal cliff,” what were the issues involved? Did you know?

- A basic understanding of economics makes you a well-rounded thinker. When you read articles about economic issues, you will understand and be able to evaluate the writer’s argument. When you hear classmates, co-workers, or political candidates talking about economics, you will be able to distinguish between common sense and nonsense. You will find new ways of thinking about current events and about personal and business decisions, as well as current events and politics.

The study of economics does not dictate the answers, but it can illuminate the different choices.

Key Concepts and Summary

Economics seeks to solve the problem of scarcity, which is when human wants for goods and services exceed the available supply. A modern economy displays a division of labor, in which people earn income by specializing in what they produce and then use that income to purchase the products they need or want. The division of labor allows individuals and firms to specialize and to produce more for several reasons: a) It allows the agents to focus on areas of advantage due to natural factors and skill levels; b) It encourages the agents to learn and invent; c) It allows agents to take advantage of economies of scale. Division and specialization of labor only work when individuals can purchase what they do not produce in markets. Learning about economics helps you understand the major problems facing the world today, prepares you to be a good citizen, and helps you become a well-rounded thinker.

Self-Check Questions

- What is scarcity? Can you think of two causes of scarcity?

- Residents of the town of Smithfield like to consume hams, but each ham requires 10 people to produce it and takes a month. If the town has a total of 100 people, what is the maximum amount of ham the residents can consume in a month?

- A consultant works for $200 per hour. She likes to eat vegetables, but is not very good at growing them. Why does it make more economic sense for her to spend her time at the consulting job and shop for her vegetables?

- A computer systems engineer could paint his house, but it makes more sense for him to hire a painter to do it. Explain why.

Review Questions

- Give the three reasons that explain why the division of labor increases an economy’s level of production.

- What are three reasons to study economics?

Critical Thinking Questions

- Suppose you have a team of two workers: one is a baker and one is a chef. Explain why the kitchen can produce more meals in a given period of time if each worker specializes in what they do best than if each worker tries to do everything from appetizer to dessert.

- Why would division of labor without trade not work?

- Can you think of any examples of free goods, that is, goods or services that are not scarce?

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. 2015. “The Employment Situation—February 2015.” Accessed March 27, 2015. http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf.

Williamson, Lisa. “US Labor Market in 2012.” Bureau of Labor Statistics . Accessed December 1, 2013. http://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2013/03/art1full.pdf.

Answers for Self-Check Questions

- Scarcity means human wants for goods and services exceed the available supply. Supply is limited because resources are limited. Demand, however, is virtually unlimited. Whatever the supply, it seems human nature to want more.

- 100 people / 10 people per ham = a maximum of 10 hams per month if all residents produce ham. Since consumption is limited by production, the maximum number of hams residents could consume per month is 10.

- She is very productive at her consulting job, but not very productive growing vegetables. Time spent consulting would produce far more income than it what she could save growing her vegetables using the same amount of time. So on purely economic grounds, it makes more sense for her to maximize her income by applying her labor to what she does best (i.e. specialization of labor).

- The engineer is better at computer science than at painting. Thus, his time is better spent working for pay at his job and paying a painter to paint his house. Of course, this assumes he does not paint his house for fun!

Principles of Microeconomics - Hawaii Edition Copyright © 2018 by John Lynham is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Liberty Fund

- Adam Smith Works

- Law & Liberty

- Browse by Author

- Browse by Topic

- Browse by Date

- Search EconLog

- Latest Episodes

- Browse by Guest

- Browse by Category

- Browse Extras

- Search EconTalk

- Latest Articles

- Liberty Classics

- Book Reviews

- Search Articles

- Books by Date

- Books by Author

- Search Books

- Browse by Title

- Biographies

- Search Encyclopedia

- #ECONLIBREADS

- College Topics

- High School Topics

- Subscribe to QuickPicks

- Search Guides

- Search Videos

- Library of Law & Liberty

- Home /

ECONLOG POST

Nov 22 2023

Economics in Everyday Life

Kevin corcoran .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-avatar img { width: 80px important; height: 80px important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-avatar img { border-radius: 50% important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-meta a { background-color: #655997 important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-meta a { color: #ffffff important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-meta a:hover { color: #ffffff important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-recent-posts-title { border-bottom-style: dotted important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-recent-posts-item { text-align: left important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-li { border-style: none important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-li { color: #3c434a important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-li { border-radius: px important; } .pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline ul.pp-multiple-authors-boxes-ul { display: flex; } .pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline ul.pp-multiple-authors-boxes-ul li { margin-right: 10px }.pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.pp-multiple-authors-wrapper.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-post-id-69046.box-instance-id-1.ppma_boxes_69046 ul li > div:nth-child(1) {flex: 1 important;}.

By Kevin Corcoran, Nov 22 2023

There are many ways to learn the ideas of economics. One way is through the standard method – read textbooks or attend lectures where ideas are described. But economics is about human action – which means the lessons of economics can also be found in our own lives. Some people claim that basic econ is often counterintuitive, and it indeed may be to some or most people. But as I began to study economics many years ago, I found its lessons extremely intuitive, because the ideas being described were things I had witnessed or experienced throughout my life.

For example, I found it very easy to envision all the ways people adjust their behavior in response to taxes. I grew up in Washington state, very close to the border with Oregon. There were two big tax differences between those states. (Well, probably more than two, but there were two I cared about at that time.) Oregon had a state income tax, while Washington did not. And Washington had a state sales tax, while Oregon did not.

Both of those were often cited as factors in decisions people would make. As people started getting jobs, it was common to find opportunities that were similarly appealing and equidistant, some in Washington and some just over the river in Oregon. When that happened, people would heavily favor finding a job in Washington, because if you worked in Oregon you had to pay Oregon state income tax, even if you weren’t an Oregon resident. (But even though you were an Oregon taxpayer, you were unable to cast any votes in Oregon – taxation without representation!) But it didn’t work in the other direction – friends I had in Portland didn’t feel any extra incentive to find a Washington job, because even if they worked in Washington, they would still have to pay Oregon state income tax.

However, the sales tax difference made a much more frequent impact. Washington’s sales tax in those days was, if memory serves, around 7.7%. This made it very common for people in Washington to put a little extra effort into driving to Oregon to make a purchase, particularly if it was a large purchase. If you needed to buy a new TV or a new couch, why would you voluntarily choose to pay what amounted to an unnecessary 7.7% surcharge on top of your already expensive purchase? I’m sure that over the years, retailers along the border in Washington lost a considerable number of sales to retailers just along the Oregon border, precisely because people would adjust their behavior in response to taxes.