- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Citations: Secondary Sources

Nontraditional sources: secondary sources video.

- Nontraditional Sources: Secondary Sources (video transcript)

Basics of Secondary Sources

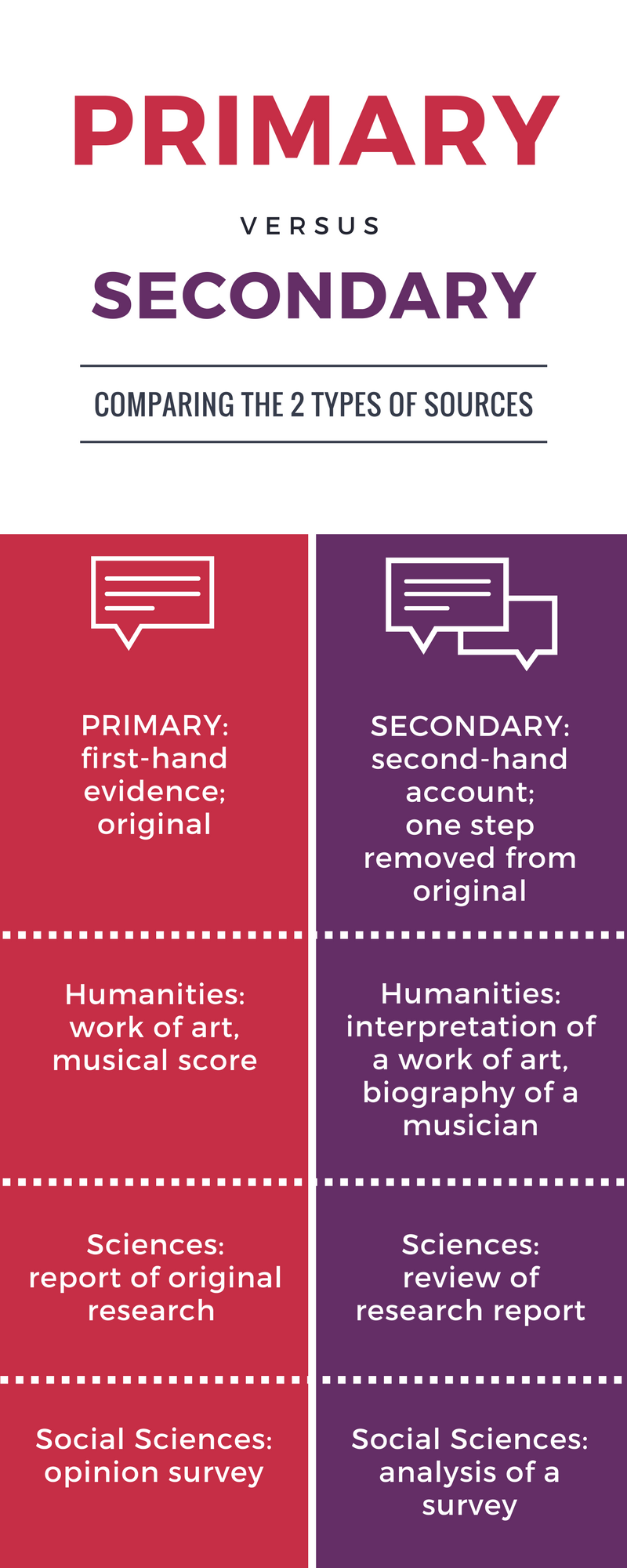

Secondary sources often are defined in contrast to primary sources. In a primary source, an author shares his or her original research—whether it be case study findings, experiment results, interview materials, or clinical observations. However, in a secondary source, an author focuses on presenting other scholars’ research, such as in a literature review.

When trying to distinguish between a primary and secondary source, it is important to ask yourself:

- Who originally made the discoveries or brought the conclusions in this document to light?

- Did the author conduct the study his or herself?

- Or is the author recounting the work of other authors?

For further guidance on determining the difference between primary and secondary sources, see Walden Library’s “Evaluating Resources: Primary & Secondary Sources” page .

Citing a Source Within a Source

Secondary sources refer to sources that report on the content of other published sources.

Citing a source within a source (citing a secondary source) is generally acceptable within academic writing as long as these citations are kept to a minimum. You should use a secondary source only if you are unable to find or retrieve the original source of information. However, if you need to cite a source within a source, follow the guidelines from APA 7, Section 8.6.

For example, imagine that you found a quotation from Culver that you wish to use in your text; however, you found this information in Jones and were unable to locate Culver’s original source. For this reference, Culver would be the primary source, and Jones would be the secondary source. You will name the primary source in your text, but the reference and citations will credit the secondary source:

According to Culver (2006, as cited in Jones, 2009), learning APA "can be tough, but like any skill, it just takes practice" (p. 23). In addition, the mastery of APA increases an author's chance of scoring well on an assignment (Culver, 2006, as cited in Jones, 2009).

Corresponding Reference List Entry

Cite just the secondary source in your reference list.

Jones, J. (2009). Scholarly writing tips . Minneapolis, MN: Publishing House.

Secondary source citations are not just for direct quotations. For instance, when referencing Rogers's adult learning theory, if you did not find the information in Rogers, your citations for the material should be in secondary source format.

Note : When citing primary material, the original publication date is usually unneeded. Following the primary author's name with the year in parentheses, like Culver (2006), indicates that you are directly citing the original source. To avoid confusion, just include the year of the secondary source in your text, like Culver (as cited in Jones, 2009).

Related Resource

Knowledge Check: Secondary Sources

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Block Quotations

- Next Page: Personal Communication

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Have a thesis expert improve your writing

Check your thesis for plagiarism in 10 minutes, generate your apa citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Working with sources

- Primary vs. Secondary Sources | Difference & Examples

Primary vs. Secondary Sources | Difference & Examples

Published on 4 September 2022 by Raimo Streefkerk . Revised on 15 May 2023.

When you do research, you have to gather information and evidence from a variety of sources.

Primary sources provide raw information and first-hand evidence. Examples include interview transcripts, statistical data, and works of art. A primary source gives you direct access to the subject of your research.

Secondary sources provide second-hand information and commentary from other researchers. Examples include journal articles, reviews, and academic books . A secondary source describes, interprets, or synthesises primary sources.

Primary sources are more credible as evidence, but good research uses both primary and secondary sources.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

What is a primary source, what is a secondary source, primary and secondary source examples, how to tell if a source is primary or secondary, primary vs secondary sources: which is better, frequently asked questions about primary and secondary sources.

A primary source is anything that gives you direct evidence about the people, events, or phenomena that you are researching. Primary sources will usually be the main objects of your analysis.

If you are researching the past, you cannot directly access it yourself, so you need primary sources that were produced at the time by participants or witnesses (e.g. letters, photographs, newspapers ).

If you are researching something current, your primary sources can either be qualitative or quantitative data that you collect yourself (e.g. through interviews, surveys, experiments) or sources produced by people directly involved in the topic (e.g. official documents or media texts).

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

A secondary source is anything that describes, interprets, evaluates, or analyses information from primary sources. Common examples include:

- Books , articles and documentaries that synthesise information on a topic

- Synopses and descriptions of artistic works

- Encyclopaedias and textbooks that summarize information and ideas

- Reviews and essays that evaluate or interpret something

When you cite a secondary source, it’s usually not to analyse it directly. Instead, you’ll probably test its arguments against new evidence or use its ideas to help formulate your own.

Examples of sources that can be primary or secondary

A secondary source can become a primary source depending on your research question . If the person, context, or technique that produced the source is the main focus of your research, it becomes a primary source.

To determine if something can be used as a primary or secondary source in your research, there are some simple questions you can ask yourself:

- Does this source come from someone directly involved in the events I’m studying (primary) or from another researcher (secondary)?

- Am I interested in analysing the source itself (primary) or only using it for background information (secondary)?

- Does the source provide original information (primary) or does it comment upon information from other sources (secondary)?

Most research uses both primary and secondary sources. They complement each other to help you build a convincing argument. Primary sources are more credible as evidence, but secondary sources show how your work relates to existing research.

What do you use primary sources for?

Primary sources are the foundation of original research. They allow you to:

- Make new discoveries

- Provide credible evidence for your arguments

- Give authoritative information about your topic

If you don’t use any primary sources, your research may be considered unoriginal or unreliable.

What do you use secondary sources for?

Secondary sources are good for gaining a full overview of your topic and understanding how other researchers have approached it. They often synthesise a large number of primary sources that would be difficult and time-consuming to gather by yourself. They allow you to:

- Gain background information on the topic

- Support or contrast your arguments with other researchers’ ideas

- Gather information from primary sources that you can’t access directly (e.g. private letters or physical documents located elsewhere)

When you conduct a literature review , you can consult secondary sources to gain a thorough overview of your topic. If you want to mention a paper or study that you find cited in a secondary source, seek out the original source and cite it directly.

Remember that all primary and secondary sources must be cited to avoid plagiarism . You can use Scribbr’s free citation generator to do so!

Common examples of primary sources include interview transcripts , photographs, novels, paintings, films, historical documents, and official statistics.

Anything you directly analyze or use as first-hand evidence can be a primary source, including qualitative or quantitative data that you collected yourself.

Common examples of secondary sources include academic books, journal articles , reviews, essays , and textbooks.

Anything that summarizes, evaluates or interprets primary sources can be a secondary source. If a source gives you an overview of background information or presents another researcher’s ideas on your topic, it is probably a secondary source.

To determine if a source is primary or secondary, ask yourself:

- Was the source created by someone directly involved in the events you’re studying (primary), or by another researcher (secondary)?

- Does the source provide original information (primary), or does it summarize information from other sources (secondary)?

- Are you directly analyzing the source itself (primary), or only using it for background information (secondary)?

Some types of sources are nearly always primary: works of art and literature, raw statistical data, official documents and records, and personal communications (e.g. letters, interviews ). If you use one of these in your research, it is probably a primary source.

Primary sources are often considered the most credible in terms of providing evidence for your argument, as they give you direct evidence of what you are researching. However, it’s up to you to ensure the information they provide is reliable and accurate.

Always make sure to properly cite your sources to avoid plagiarism .

A fictional movie is usually a primary source. A documentary can be either primary or secondary depending on the context.

If you are directly analysing some aspect of the movie itself – for example, the cinematography, narrative techniques, or social context – the movie is a primary source.

If you use the movie for background information or analysis about your topic – for example, to learn about a historical event or a scientific discovery – the movie is a secondary source.

Whether it’s primary or secondary, always properly cite the movie in the citation style you are using. Learn how to create an MLA movie citation or an APA movie citation .

Articles in newspapers and magazines can be primary or secondary depending on the focus of your research.

In historical studies, old articles are used as primary sources that give direct evidence about the time period. In social and communication studies, articles are used as primary sources to analyse language and social relations (for example, by conducting content analysis or discourse analysis ).

If you are not analysing the article itself, but only using it for background information or facts about your topic, then the article is a secondary source.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Streefkerk, R. (2023, May 15). Primary vs. Secondary Sources | Difference & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 29 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/working-sources/primary-vs-secondary-sources/

Is this article helpful?

Raimo Streefkerk

Other students also liked, tertiary sources explained | quick guide & examples, types of sources explained | examples & tips, how to find sources | scholarly articles, books, etc..

University Library

Distinguish between primary and secondary sources.

- Further Information

Introduction

1. Introduction

Whether conducting research in the social sciences, humanities (especially history), arts, or natural sciences, the ability to distinguish between primary and secondary source material is essential. Basically, this distinction illustrates the degree to which the author of a piece is removed from the actual event being described, informing the reader as to whether the author is reporting impressions first hand (or is first to record these immediately following an event), or conveying the experiences and opinions of others—that is, second hand .

2. Primary sources

These are contemporary accounts of an event, written by someone who experienced or witnessed the event in question. These original documents (i.e., they are not about another document or account) are often diaries, letters, memoirs, journals, speeches, manuscripts, interviews and other such unpublished works. They may also include published pieces such as newspaper or magazine articles (as long as they are written soon after the fact and not as historical accounts), photographs, audio or video recordings, research reports in the natural or social sciences, or original literary or theatrical works.

3. Secondary sources

The function of these is to interpret primary sources , and so can be described as at least one step removed from the event or phenomenon under review. Secondary source materials, then, interpret, assign value to, conjecture upon, and draw conclusions about the events reported in primary sources. These are usually in the form of published works such as journal articles or books, but may include radio or television documentaries, or conference proceedings.

4. Defining questions

When evaluating primary or secondary sources, the following questions might be asked to help ascertain the nature and value of material being considered:

- How does the author know these details (names, dates, times)? Was the author present at the event or soon on the scene?

- Where does this information come from—personal experience, eyewitness accounts, or reports written by others?

- Are the author's conclusions based on a single piece of evidence, or have many sources been taken into account (e.g., diary entries, along with third-party eyewitness accounts, impressions of contemporaries, newspaper accounts)?

Ultimately, all source materials of whatever type must be assessed critically and even the most scrupulous and thorough work is viewed through the eyes of the writer/interpreter. This must be taken into account when one is attempting to arrive at the 'truth' of an event.

Ask a Librarian

In Person | Phone | Email | Chat

Related Guides

- Distinguish between Popular and Scholarly Journals by Annette Marines Last Updated Mar 17, 2024 3772 views this year

- Next: Further Information >>

Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License except where otherwise noted.

Land Acknowledgement

The land on which we gather is the unceded territory of the Awaswas-speaking Uypi Tribe. The Amah Mutsun Tribal Band, comprised of the descendants of indigenous people taken to missions Santa Cruz and San Juan Bautista during Spanish colonization of the Central Coast, is today working hard to restore traditional stewardship practices on these lands and heal from historical trauma.

The land acknowledgement used at UC Santa Cruz was developed in partnership with the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band Chairman and the Amah Mutsun Relearning Program at the UCSC Arboretum .

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.4: Primary, Secondary and Tertiary Sources

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 205566

Teaching & Learning and University Libraries

Another information category is called publication mode and has to do with whether the information is:

- Firsthand information (information in its original form, not translated or published in another form).

- Secondhand information (a restatement, analysis, or interpretation of original information).

- Thirdhand information (a summary or repackaging of original information, often based on secondary information that has been published).

The three labels for information sources in this category are, respectively, primary sources, secondary sources, and tertiary sources . Here are examples to illustrate the first- handedness, second-handedness, and third-handedness of information:

When you make distinctions between primary, secondary, and tertiary sources, you are relating the information itself to the context in which it was created. Understanding that relationship is an important skill that you’ll need in college, as well as in the workplace. Noting the relationship between creation and context helps us understand the “big picture” in which information operates and helps us figure out which information we can depend on. That’s a big part of thinking critically, a major benefit of actually becoming an educated person.

As a reminder, recall one of the frames of the Framework for Information Literacy is Authority is Constructed and Contextual . Information does not occur in a vacuum, but within a context that impacts its meaning. Part of that context will be how you as an information consumer will process the different facets in which that information exists. So, with this in mind, recognize that primary sources as defined below are not cut and dried, nor black or white. For example, to a historian, an image or a representation of a piece of sculpture might be considered a primary source for the purposes of historical analysis; however, to a sculpture or an archaeologist, anything short of the physical piece of sculpture itself would not be considered a primary source. So, in this case, the “context” to consider is how the source of information itself is perceived by a particular discipline (history vs. sculpture or archaeology). More on this below when we consider the “format” of a source.

Primary Sources – Because it is in its original form, the information in primary sources has reached us from its creators without going through any filter. We get it firsthand. Here are some examples that are often used as primary sources:

- Any literary work, including novels, plays, and poems.

- Breaking news (first formal documentation of event–remember the Information Cycle).

- Advertisements.

- Music and dance performances.

- Eyewitness accounts, including photographs and recorded interviews.

- Blog entries that are autobiographical.

- Scholarly blogs that provide data or are highly theoretical, even though they contain no autobiography.

- Artifacts such as tools, clothing, or other objects.

- Original documents such as tax returns, marriage licenses, and transcripts of trials.

- Websites, although many are secondary.

- Correspondence, including email.

- Records of organizations and government agencies.

- Journal articles that report original research for the first time (at least the parts about the new research, plus their data).

Secondary Source – These sources are sources about the sources, such as analysis or interpretation of the original information, the primary source. Thus, the information comes to us secondhand, or through at least one filter. Here are some examples that are often used as secondary sources:

- Nonfiction books and magazine articles except autobiography.

- An article or website that critiques a novel, play, painting, or piece of music.

- An article or web site that synthesizes expert opinion and several eyewitness accounts for a new understanding of an event.

- The literature review portion of a scholarly journal article.

Tertiary Source – These sources further repackage the original information because they index, condense, or summarize the original.

Typically, by the time tertiary sources are developed, there have been many secondary sources prepared on their subjects, and you can think of tertiary sources as information that comes to us “third-hand,” that is, pre -processed. Tertiary sources are usually publications that you are not intended to read from cover to cover but to dip in and out of for the information you need. You can think of them as a good place for background information to start your research but a bad place to end up. Here are some examples that are often used as tertiary sources, which are also considered “reference sources” in the library world:

- Dictionaries.

- Guide books, like the MLA Handbook

- Survey articles.

- Bibliographies.

- Encyclopedias, including Wikipedia.

- Most textbooks, including the one you are now reading.

Tertiary sources are usually not acceptable as cited sources in college research projects because they are so far removed from firsthand information. That’s why most professors don’t want you to use Wikipedia as a citable source: the information in Wikipedia is far from original information. Other people have considered it, decided what they think about it, rearranged it, and summarized it–all of which is actually what your professors want you , not another author, to do with information in your research projects.

The Details Are Tricky — A few things about primary or secondary sources might surprise you:

- Sources have the potential of becoming primary rather than always exist as primary sources.

It’s easy to think that it is the format of primary sources that makes them primary. But that’s not all that matters. When you see lists like the one above of sources that are often used as primary sources, it’s wise to remember that the ones listed are not automatically already primary sources. Firsthand sources get that designation only when researchers actually find their information relevant and use it.

For instance: Here is an illustration of the frame, Authority is Constructed and Contextual. Records that could be relevant to those studying government are created every day by federal, state, county, and city governments as they operate. But until the raw data are actually used by a researcher, they cannot be considered primary sources. How this data is used is what gives these sources the designation, and authority, as primary sources.

Another example that references the frame, Authority is Constructed and Contextual : A diary about his flying missions kept by an American helicopter pilot in the Vietnam War is not a primary source until, say, a researcher uses it in her study of how the war was carried out. But it will never be a primary source for a researcher studying the U.S. public’s reaction to the war because it does not contain information relevant to that study.

- Primary sources, even eyewitness accounts, are not necessarily accurate. Their accuracy has to be evaluated, just like that of all sources.

- Something that is usually considered a secondary source can be considered a primary source, depending on the research project and the context in which something is used .

Here is another example where the context of the use of the source dictates whether or not the source is primary or secondary. For instance, movie reviews are usually considered secondary sources. But if your research project is about the effect movie reviews have on ticket sales, the movie reviews you study would become primary sources.

- Deciding whether to consider a journal article a primary or a secondary source can be complicated for at least two reasons.

First, scholarly journal articles that report new research for the first time are usually based on data. So some disciplines consider the data to be the primary source, and the journal article that describes and analyzes them is considered a secondary source.

However, particularly in the sciences, the original researcher might find it difficult or impossible (he or she might not be allowed) to share the data. So sometimes you have nothing more firsthand than the journal article, which argues for calling it the relevant primary source because it’s the closest thing that exists to the data.

Second, even scholarly journal articles that announce new research for the first time usually contain more than data. They also typically contain secondary source elements, such as a literature review, bibliography, and sections on data analysis and interpretation. So they can actually be a mix of primary and secondary elements. Even so, in some disciplines, a journal article that announces new research findings for the first time is considered to be, as a whole, a primary source for the researchers using it.

ACTIVITY: Under What Circumstances?

Instructions: Look at each of the sources listed below and think of circumstances under which each could become a primary source. (There are probably many potential circumstances for each.) So just imagine you are a researcher with projects that would make each item firsthand information that is relevant to your work. What kind of project would make each of the following sources relevant firsthand information? Our answers are at the bottom of the page, but remember that there are many more–including the ones you think of that we didn’t!

- Fallingwater, a Pennsylvania home designed and constructed by Frank Lloyd Wright in the 1930s.

- Poet W.H. Auden’s elegy for Y.S. Yeats.

- An arrowhead made by (Florida) Seminole Native Americans but found at Flint Ridge outside Columbus, Ohio.

- E-mail between the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, Nikki Haley, and her staff about North Korea.

- A marriage license.

Despite their fluidity, what primary sources usually offer is too good not to consider using because:

- They are original. This unfiltered, firsthand information is not available anywhere else.

- Their creator was a type of person unlike others in your research project, and you want to include that perspective.

- Their creator was present at an event and shares an eyewitness account.

- They are objects that existed at the particular time of the project you are studying.

Particularly in humanities courses, your professor may require you to use a certain number of primary sources for your project. In other courses, particularly in the sciences, you may be required to use only primary sources.

What is considered primary and secondary sources can vary from discipline to discipline. If you are required to use primary sources for your research project, before getting too deep into your project, check with your professor to make sure he or she agrees with your choices. After all, it’s your professor who will be grading your project. A librarian, too, can verify your choices. Just remember to take a copy of your assignment with you when you ask, because the librarian will want to see the original assignment. After all, that’s a primary source!

POSSIBLE AnswerS TO ACTIVITY: Under What Circumstances?

- You are doing a study of the entrances Wright designed for homes, which were smaller than other architects of the time typically designed entrances.

- Your research project is about the Auden-Yeats relationship.

- Your research project is about trade among 19th century Native Americans east of the Mississippi River.

- Your research project is on how Ambassador Haley conveyed a decision about North Korea to her staff.

- You are writing about the life of a person who claimed to have married several times, and you need more than her statements about when those marriages took place and to whom.

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Secondary Sources

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

In the social sciences, a secondary source is usually a scholar book, journal article, or digital or print document that was created by someone who did not directly experience or participate in the events or conditions under investigation. Secondary sources are not evidence per se, but rather, provide an interpretation, analysis, or commentary derived from the content of primary source materials and/or other secondary sources.

Value of Secondary Sources

To do research, you must cite research. Primary sources do not represent research per se, but only the artifacts from which most research is derived. Therefore, the majority of sources in a literature review are secondary sources that present research findings, analysis, and the evaluation of other researcher's works.

Reviewing secondary source material can be of valu e in improving your overall research paper because secondary sources facilitate the communication of what is known about a topic. This literature also helps you understand the level of uncertainty about what is currently known and what additional information is needed from further research. It is important to note, however, that secondary sources are not the subject of your analysis. Instead, they represent various opinions, interpretations, and arguments about the research problem you are investigating--opinions, interpretations, and arguments with which you may either agree or disagree with as part of your own analysis of the literature.

Examples of secondary sources you could review as part of your overall study include: * Bibliographies [also considered tertiary] * Biographical works * Books, other than fiction and autobiography * Commentaries, criticisms * Dictionaries, Encyclopedias [also considered tertiary] * Histories * Journal articles [depending on the discipline, they can be primary] * Magazine and newspaper articles [this distinction varies by discipline] * Textbooks [also considered tertiary] * Web site [also considered primary]

- << Previous: Primary Sources

- Next: Tiertiary Sources >>

- Last Updated: May 2, 2024 4:39 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- Skip to search box

- Skip to main content

Princeton University Library

Wri101 into the deep past.

- Comparison of Google, Scholar, Articles+, and Web of Science

- Working with Wikipedia

- Finding articles using a database

- Primary, secondary, and tertiary sources

- News sources

- Managing sources

- Academic Integrity at Princeton

Primary v Secondary Sources

The Standard Definition

In historical writing, a primary source is a document or physical object which was written or created during the time under study. These sources were present during an experience or time period and offer an inside view of a particular event. Some types of primary sources include: * ORIGINAL DOCUMENTS (excerpts or translations acceptable): Diaries, speeches, manuscripts, letters, interviews, news film footage, autobiographies, official records * CREATIVE WORKS: Poetry, drama, novels, music, art * RELICS OR ARTIFACTS: Pottery, furniture, clothing, buildings Examples of primary sources include: * Diary of Anne Frank - Experiences of a Jewish family during WWII * The Constitution of Canada - Canadian History * A journal article reporting NEW research or findings * Weavings and pottery - Native American history * Plato's Republic - Women in Ancient Greece What is a secondary source? A secondary source interprets and analyzes primary sources. These sources are one or more steps removed from the event. Secondary sources may have pictures, quotes or graphics of primary sources in them. Some types of seconday sources include: * PUBLICATIONS: Textbooks, magazine articles, histories, criticisms, commentaries, encyclopedias Examples of secondary sources include: * A journal/magazine article which interprets or reviews previous findings * A history textbook * A book about the effects of WWI Search by keyword for Primary Sources in the Main Catalog You can search the Main Catalog to find direct references to primary source material. Perform a keyword search for your topic and add one of the words below: (these are several examples of words that would identify a source as primary) * charters * correspondence * diaries * early works * interviews * manuscripts * oratory * pamphlets * personal narratives * sources * speeches * letters * documents

Another Possible Usage

PRIMARY SOURCE (more frequently PRIMARY TEXT) is sometimes used in a different sense in some types of classes. In a literature class, for example, the primary source might be a novel about which you are writing, and secondary sources those sources also writing about that novel (i.e., literary criticism). However, if you were writing about the literary criticism itself and making an argument about literary theory and the practice of literary criticism, some would use the term PRIMARY SOURCE to refer to the criticism about which you are writing, and secondary sources other sources also making theoretical arguments about the practice of literary criticism. In this second sense of primary source, whatever you are primarily writing ABOUT becomes the primary source, and secondary sources are those sources also writing about that source. Often this will be called the PRIMARY TEXT, but some people do use primary source with this meaning.

Tertiary Sources

Just so you can keep up with all the scholarly jargon about sources, a tertiary source is a source that builds upon secondary sources to provide information. The most common example is an encyclopedia. Consider a particular revolution as an historical event. All the documents from the time become primary sources. All the historians writing later produce secondary sources. Then someone reads those secondary sources and summarizes them in an encyclopedia article, which becomes a tertiary source. If someone then collected a bibliography of encyclopedia articles on the topic, that might be a quarternary source, but at that point the whole thing just becomes silly.

Evaluating Sources

- Critically Analyzing Information Sources Some questions to consider when evaluating sources.

- Distinguishing Scholarly Journals from other Periodicals You need a scholarly journal article. How do you know if you have one?

Evaluating Websites

FROM: Kapoun, Jim. "Teaching undergrads WEB evaluation: A guide for library instruction." C&RL News (July/August 1998): 522-523.

- << Previous: Evaluating information

- Next: Books >>

- Last Updated: Apr 16, 2024 11:35 AM

- URL: https://libguides.princeton.edu/wri101

- UConn Library

- Scientific Research and Communication

- Primary and Secondary Sources

Scientific Research and Communication — Primary and Secondary Sources

- Essential Resources

- The Scientific Method

- Types of Scientific Papers

- Organization of a Scientific Paper

- Peer Review & Academic Journals

- Scientific Information Literacy

- Critical Reading Methods

- Scientific Writing Guidebooks

- Science Literature Reviews

- Searching Strategies for Science Databases

- Engineering Career Exploration

- Qualitative Research: What is it?

- Quantitative Research: What Is It?

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- AI Tools for Research

Primary & Secondary Sources in the Sciences - Overview

Primary Sources

In the sciences, primary sources are very specific. Primary source documents in the sciences focus on original research, ideas, or findings and are most often published in scholarly journals or presented at academic conferences. These articles or presen tati ons mark the first publication of such research; they present new data and detail the researcher’s methodology and results.

Primary sources are factual, not interpretive, and include sources such as

- published results of research studies, experiments, clinical trials

- proceedings of conferences and meetings

- technical reports

Secondary Sources

Secondary sources in the sciences analyze and interpret primary research results. These sources usually have the goal of summarizing, explaining, or providing an overview of a topic, and can help place the research in context. Secondary literature is often published in books, magazines, or journals.

Secondary sources include sources such as

- review articles, which summarize previously published studies

- articles that discuss the significance of published research or experiments

- analyses of clinical trials

Identifying Primary Research Articles in the Sciences (video)

video from University of Wisconsin-Madison Libraries

Primary, Secondary, & Tertiary Sources

- Humanities/Social Sciences

Informational sources can be classified roughly into three groups - primary, secondary, and tertiary - that reflect their originality. These groups are defined generally below.

Primary sources are original, uninterpreted information. Unedited, firsthand access to words, images, or objects created by persons directly involved in an activity or event or speaking directly for a group. This is information before it has been analyzed, interpreted, commented upon, spun, or repackaged. Depending upon the context, these may include research reports, sales receipts, speeches, e-mails, original artwork, manuscripts, photos, diaries, personal letters, spoken stories/tales/interviews, diplomatic records, etc.

Think of physical evidence or eyewitness testimony in a court trial.

Secondary sources interpret, analyze, or summarize. Commentary upon, or analysis of, events, ideas, or primary sources. Because they are often written significantly after events by parties not directly involved but who have special expertise, they may provide historical context or critical perspectives. Examples are scholarly books, journals, magazines, criticism, interpretations, and so forth.

Think of a lawyer's final summation or jury discussion in a court trial.

Tertiary sources compile, index, or organize sources. Sources which analyzed, compiled and digest secondary sources included mostly in abstracts, bibliographies, handbooks, encyclopedias, indexes, chronologies, etc.

Think of an index that lists all the cases heard by this court during the year.

In the humanities and social sciences, primary sources are the direct evidence or first-hand accounts of events without secondary analysis or interpretation. A primary source is a work that was created or written contemporary with the period or subject being studied. Secondary sources analyze or interpret historical events or creative works.

Primary sources

- Autobiographies

- Original works of art

- Photographs

- Works of literature

A primary source is an original document containing firsthand information about a topic. Different fields of study may use different types of primary sources.

Secondary sources

- Biographies

- Dissertations

- Indexes, abstracts, bibliographies (used to locate a secondary source)

- Journal articles

- Book about a primary source

A secondary source contains commentary on or discussion about a primary source. The most important feature of secondary sources is that they offer an interpretation of information gathered from primary sources.

Tertiary sources

- Dictionaries

- Encyclopedias

A tertiary source presents summaries or condensed versions of materials, usually with references back to the primary and/or secondary sources. They can be a good place to look up facts or get a general overview of a subject, but they rarely contain original material.

Adapted from lib.vt.edu

In the sciences, primary sources are documents written by the person(s) who conducted the original research. For example, a primary source would be a research article where scientists describe their methodology, results, and conclusions about the genetics of tobacco plants. A secondary source would be an article commenting or analyzing the scientists' research on tobacco.

- Conference proceedings

- Original research articles

- Lab notebooks

- Technical reports

These sources are where the results of original research are usually first published in the sciences. This makes them the best source of information on cutting edge topics. However the new ideas presented may not be fully refined or validated yet.

- Review Articles

These sources tend to summarize the existing state of knowledge in a field at the time of publication. Secondary sources are useful places to learn about your topic in depth. They are useful places to find comparisons of different ideas and theories and to see how they may have changed over time.

- Compilations

These types of sources present condensed material, generally with references back to the primary and/or secondary literature. They can be a good place to look up data or to get an overview of a subject, but they rarely contain original material.

modified from l ib.vt.edu

- << Previous: Peer Review & Academic Journals

- Next: Scientific Information Literacy >>

- Last Updated: Apr 24, 2024 1:46 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/sciencecommunication

How Scientific and Technical Information Works

- Introduction to the Ecosystem

An Information Timeline

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tertiary or Reference Sources

- Popular (vs. Scholarly) Sources

- Peer Review

- Search Strategies

- How to Evaluate Information

- Cite Sources

- Citation Management Software This link opens in a new window

In science, technology, engineering, and math, things are always happening. New ideas, unexpected experimental results, incremental achievements and landmark discoveries. One way we like to categorize the information that is produced in order to document, analyze, and integrate an Event is based on their proximity to that Event: "Primary," "Secondary," and "Tertiary" literature. An Event, a reaction to the Event, and a summary of the Event.

We value primary literature because it gets us as close as possible to the Event itself. We value secondary literature because it provides us with commentary, analysis, critique, and contextualization of the Event. We value tertiary literature because it distills the Event and its aftermath down to a short, authoritative entry that helps us quickly understand what happened.

Primary sources bring us the closest we're ever likely to get to most new research and theoretical work in STEM. These publications document experiments, observations, discoveries, new modes of analysis, and new research methods, and they are written by the people most directly involved. While peer reviewed articles in scholarly journals are the most common and well-known source of primarily literature in STEM, it can be found in a variety of formats. If your professor asks you to find a primary source for class, this is probably what they're looking for. Below are the most common types of primary research publications you are likely to encounter.

Peer Reviewed Research Articles

Research articles are extensive and detailed descriptions of scientific experiments, observations, and analysis carried out by the authors. (Learn more about peer review in the "What is Peer Review?" tab to your left.) These articles are published in peer-reviewed journals, or occasionally as chapters in edited scholarly books. They are the primary way that most scientists learn about advances in their fields. If an article is very influential in its field, or at least very interesting or surprising, it is likely to be cited in the publications of other scientists working in the same areas, and perhaps analyzed, critiqued, or commented on in a secondary work of literature.

Conference Proceedings

Conference proceedings are often “works in progress” originally meant to accompany the author’s lecture or poster at a conference. They are not always peer reviewed to the same extent as articles. The author may have later published a longer article in a scholarly journal based on the conference proceeding. Conference proceedings are a primary mode of information sharing in some fields, such as computer science and engineering, physics, and mathematics.

Preprints are early versions of articles which have not been through a peer review process yet, but which the authors want their colleagues in the field to have access to anyways. Preprints help to facilitate more rapid sharing of information, for example during a pandemic, but they are also valuable ways for authors to receive feedback on their work prior to publication. These can be great sources of cutting edge information, but it’s important to remember that they still haven't completed the publication process, and the final version of the article will likely be different.

Dissertations and Theses

Dissertations are written by doctoral students as the culminating evidence of their studies in graduate school. They are meant to be an original contribution of research to the author’s field. Dissertations are reviewed carefully by a committee of university faculty before a degree is awarded. While a full dissertation is often book-length, many authors will also opt to publish parts of it as research articles.

A patent is a legal document providing evidence of intellectual copyright over an invention (usually a product, process, method, or composition), allowing the patent holder to exclude others from making, using, or selling the invention for a period of time. Patents include original evidence describing the invention, and are thus often considered primary. Once published by the US Patent and Trademark Office, they are freely available, although often difficult to locate.

Internal Reports and other "Grey Literature"

Individual organizations produce a great quantity of original material documenting their operations that is never formally published. This is commonly referred to as “grey literature.” Grey literature that could be considered primary might include internal reports, technical documents, memos, and personal communications.

This section includes original data collected in the course of research projects. “Raw” implies the data hasn’t yet been cleaned up or manipulated. This includes numerical data, tables and charts, code, maps, transcripts, photos and drawings, lab and field notebooks, sound recordings, and even material samples. Raw data is sometimes shared by researchers who value open science, but this isn’t yet a norm.

Secondary sources are a step away from the Events that primary sources document. Generally, these sources are commenting on, analyzing, interpreting, or evaluating primary sources. These types of sources help researchers contextualize what's happening in their field, and they can contribute to the direction of primary research by identifying longer-term trends and implications. In college, many of the papers and articles that students produce are secondary sources.

Review Articles

Reviews are a genre of article or book chapter which present an overview of the current state of research on a particular topic. The authors identify and analyze the most important discoveries, trends, and publications on that topic. There are different types of reviews that are prevalent in particular fields. Additionally, there are review journals that exclusively publish peer-reviewed review articles, and many edited scholarly books are collections of review articles.

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

Systematic reviews, which are most common to medical and health sciences, are a specific type of review article that attempts to answer a research question by systematically aggregating and reviewing the data from large numbers of existing primary research articles on a topic. Meta-analysis is a common statistical analysis used in systematic reviews.

Annotated Bibliographies and Other Types of Literature Reviews

Annotated bibliographies are a highly stylized form of literature review. Rather than being written as a single narrative, they present a list of sources (a bibliography) on a topic, and provide review and analysis (annotation) for each source as it relates to the theme of the bibliography. Other types of literature reviews are more likely to put selected sources into conversation with each other, by comparing and contrasting them together in an essay format rather than considering each individually.

Monographs (Books)

Most, but not all, nonfiction scholarly books that are written entirely by one or two people (as opposed to edited volumes where each chapter is by a separate author) are works of secondary literature whose purpose is to provide commentary, analysis, and critique on a theme or topic. The authors are not reporting on new information they have discovered, but they are adding to the field with their intellectual examination of existing information.

Information that is confirmed through the scientific process and through the vigorous debate played out in the literature eventually comes to be considered consensus knowledge. This type of knowledge is published in tertiary, or reference sources, whose main purpose is to present established information on a topic in easily digestible form, where it can be quickly referred to as people are working.

Encyclopedias

The purpose of an encyclopedia is to provide readers with a brief overview of established knowledge in a field. There is minimal analysis and no new information is being reported. Encyclopedias can vary widely in scope, from massive encyclopedias of everything, such as Wikipedia, to niche encyclopedias covering specific fields, such as the Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology.

Dictionaries

Dictionaries exist to provide consensus definitions of words and phrases. There are many language dictionaries, which attempt to define every word in a language, and are usually pretty large. There are also smaller subject dictionaries that attempt to provide definitions of field-specific terminology, such as the Dictionary of Materials Science.

Textbooks are not usually written either to present wholly new information to the world, or to provide analysis or critical interrogation to existing information. The purpose of textbooks is to inform and educate students on the current state of knowledge in an area.

Property Data Handbooks and Indexes

Handbooks and other tools that provide chemical property data are invaluable reference sources for chemists and other scientists who need chemical information. The data is originally discovered and published in the primary literature, but once established it is collated and presented in these handbooks and indexes where it can quickly be found and referred to as chemists are working.

Databases, Bibliographies, and Concordances

These are not "sources" in the same sense as the other sources on this list, but they are all tools that allow us to locate primary and secondary literature. In that sense, many consider databases et al to be honorary tertiary sources.

Most information is not scholarly information, of course. Most published information is meant for a wider audience than one's peers in biotoxicology. So when we talk about information as "popular" instead of scholarly, we're simply referring to information that's meant for a bigger audience. This includes scientific writing! A short list of popular literature:

- Books about astronomy that you could find in an average bookstore, often with eye-catching enhanced Hubble Telescope photos on the cover

- Scientific American, Sky and Telescope, and Popular Mechanics magazines

- MIT Technology Review

- Articles in the newspaper reporting on specific research studies

If you aren't sure whether something is popular or scholarly, think about:

- Is the author a scientist themselves? Scientists do sometimes write for larger audiences, but journalists do not write scientific literature.

- the writing style: it'll be clearer, you won't need a special dictionary to get through a paragraph, and it'll be written to keep you engaged. It may even be funny or conversational.

- are there engaging visuals involved? A beautiful or stylish cover for a book, interesting graphics to accompany articles? Scholarly articles rarely include decorative images.

Basically, if the audience is scholarly, and the purpose is to inform the audience of new research in their fields, it's scholarly. If the audience is anyone who happens to pick up a book or magazine, it's popular.

- << Previous: Introduction to the Ecosystem

- Next: Peer Review >>

- Last Updated: Mar 28, 2024 12:30 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.gonzaga.edu/STEMinformationliteracy

Primary, Secondary and Tertiary Sources: Secondary

- A Quick Look

- Discipline Grid

- Library FAQs

Is it SECONDARY?

Books and journal articles discussing or analyzing Darwin's notes, sketches or theories in depth, are SECONDARY sources. Secondary sources, which interpret, analyze, or otherwise filter primary, or other secondary, sources, are explained here.

Google Scholar

Use Google Scholar to find academic-quality information (articles, papers, reports) on the Web.

Secondary Sources: A Closer Look

Frequently, a source that is not a primary source is a SECONDARY source. Typically, secondary sources comment upon, analyze, or draw information from primary sources. Secondary sources can also interpret, critique, or explain primary sources. EXAMPLE:

- Many books and journal articles have been written analyzing, interpreting, critiquing, refuting or corroborating Charles Darwin's thoughts on natural selection and the concept of evolution.

- Such books and journal articles are SECONDARY sources, like this e-book (electronic book) available at the NYIT Library: Darwin and Modern Science: Essays , A.C. Seward (Ed.).

Like this e-book about Charles Darwin and his science, a secondary source analyzes, interprets, filters, or otherwise discusses primary source material.

- << Previous: Primary

- Next: Tertiary >>

- Last Updated: Jan 13, 2021 8:21 AM

- URL: https://libguides.nyit.edu/sources

Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Sources: A Quick Guide: Secondary Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tertiary Sources

What is a Secondary Source?

Secondary sources are books, periodicals, web sites, etc. that people write using the information from primary sources. They are not written by eyewitnesses to events, for instance, but use eyewitness accounts, photographs, diaries and other primary sources to reconstruct events or to support a writer's thesis about the events and their meaning. Many books you find in the Cornell Library Catalog are secondary sources.

Reference Help

- << Previous: Primary Sources

- Next: Tertiary Sources >>

- Last Updated: Apr 12, 2024 4:30 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.cornell.edu/sources

Academic Writing

- Getting Started

- Introductions

- Thesis Statements

- Organization

- Conclusions

Using Secondary Sources

- Global vs. Local Revision

- Suggestions for Revision

- Why is Grammar Important?

- Suggestions for Further Reading

- Academic Success Center This link opens in a new window

- Citing Sources This link opens in a new window

Associate Professor-Librarian

- What are Primary and Secondary Sources?

- Using Summary

- Make Your Sources Speak

What Are Primary and Secondary Sources?

A primary source is a source that you are analyzing as the writer. In other words, there is no mediary between you and the text; you are the one doing the analysis.

Some examples of primary sources:

A secondary source , then, is a source that has also done analysis of the same (or a similar) topic. You will then use this source to discuss how it relates to your argument about the primary source. A secondary source is a mediary between you and the primary source. Secondary sources can also help your credibility as a writer; when you use them in your writing, it shows that you have done research on the topic, and can enter into the conversation on the topic with other writers.

Some examples of secondary sources:

Summary: When and How Do I Use It?

One of the important distinctions to make when coming to terms with a text is knowing when to summarize it, when to paraphrase it, and when to quote it. Here’s what Joseph Harris, author of the textbook Rewriting: How to Do Things with Texts , has to say:

“Summarize when what you have to say about a text is routine and quote when it is more contentious” (21).

In other words, quote when you need to rely on the voice of the writer, when you need the language of the text to help you make a point. Otherwise, try to use paraphrase or summary, so that your ideas are still the main focus.

Summarizing a text can distract your reader from your argument, especially if you rely on lengthy summaries to capture a source in a nutshell. However, it can also prove an effective rhetorical tool: you just need to know when to use it.

You can use summary in the following ways:

- When the source offers important background about your ideas

- When you need to provide your readers with an overview of a source’s entire argument before analyzing certain ideas from it

- When the source either supports your thesis, or when it offers a position you want to argue against or analyze more in-depth

Here is a sample summary. What do you notice about it?

Ryuko Kubota argues in “Ideologies of English in Japan” that the debate over English’s place in the Japanese language disappeared with the militaristic rule of the 1930s and 1940s, when Japan rejected and/or suppressed the learning of English and other languages in favor of heavy nationalism. However, he adds that the debate returned during America’s occupation of Japan and has periodically been a topic for debate since. Japanese politicians have always seen English as an important tool for Japan’s success as an industrial nation on a global scale. However, instead of molding itself to the English of the Western world, Japan has integrated English to fit its ideologies, to serve its own needs; indeed, to become part of the Japanese language.

1. This is a succinct summary; the entire summary is only three sentences.

2. The final sentence of the paragraph is the writer's attempt to make a connection between the article and her own ideas for her paper. This is an important step in using summary; it's important to always show the reader how/why the summary is important/relevant.

Paraphrasing: When/How/Why Should I Do It?

Paraphrasing gives you the room to condense a text’s ideas into your own words. You can use this, for example, to rewrite a definition, to emphasize important points, or to clarify ideas that might be hard for the reader to understand if you quote the original text.

When you paraphrase, remember that you still need to cite the source in-text!

Depending on your field and the style guide your field follows, you may be required to paraphrase more than quote or summarize. Make sure you are familiar with the writing conventions for your field. APA, for example, draws much more on paraphrase than MLA.

Example of a Paraphrase

Let’s look at an example of a paraphrase. Note that here the author of this paraphrase has used the author’s name first as an attributive tag – she is letting the reader know who wrote this. She then goes on to put the writer’s ideas into her own words, but acknowledges directly where the ideas came from by using the in-text citation at the end of the second sentence.

- This is a paraphrase for MLA; in APA, the year would come after Honna's name in parentheses.

In source-based or synthesis writing, we try to not only express our ideas using our own voice, but to also express our ideas through the voices of those we are citing. In their book Wriiting Analytically , Rosenwasser and Stephen offer six strategies to use in researched writing to make our sources speak, to make them come alive.

Here are some typical problems we encounter when using primary and secondary sources:

- Leaving quotations and paraphrases to speak for themselves

- Not differentiating your own voice from the voices of your sources (ventriloquizing)

- Resorting to overly agreeing and disagreeing as your only means of responding to a source (other than summary)

Primary and secondary sources are nothing to fear. Many times we either leave sources to speak for themselves or ignore them altogether because we are afraid of losing our own voices. These strategies, listed below, are designed to help us know when and how to use quotes, and how not to become lost in the process.

Strategy 1: Make Your Sources Speak

v Quote, paraphrase, or summarize in order to analyze , as opposed to in place of analyzing. Don’t assume that the meaning of your source material is self-evident. Instead, explain to your readers what the quote, paraphrase, or summary means. For example, what aspects do you find interesting or strange? And relate these aspects to your overall thesis. Your focus here in analysis should be on how the source leads you to your conclusion – beware of generalizing or putting two quotes next to each other without explaining the connection.

Using Strategy #1 : How are you using your sources? Are you taking the time to develop points from your sources, or are you just using evidence – and is it clear why you are using it? Highlight/bracket analysis, mark in a different color where analysis is not present immediately following source.

Strategy 2: Use Your Sources to Ask Questions, Not Just to Provide Answers

v Use your selections from your sources as a means to raise issues and questions; avoid the temptation to use selections that provide answers without any commentary or further elaboration. If you feel stuck with this, consider the source alongside other contexts (other sources, for example) and compare and contrast them to see if there are aspects of your topic that your source does not adequately address.

Using Strategy #2: Again, ask: how are you using your sources as question generators? What how/why questions do your sources generate? Look over the evidence you’ve used, and jot down the how/why questions you think your evidence creates. Next, go through your paper. Do you see yourself addressing these questions? Mark your analysis appropriately so you can see how you’re addressing these questions (or not).

Strategy 3: Put Your Sources in Conversation with One Another

v This is an extension of strategy 2. Rather than limiting yourself to the only conversationalist with each source, aim for conversation among them. Although it is not wrong to agree or disagree with your sources, it is wrong to see these as your only possible moves. You should also understand that although it is sometimes useful and perhaps even necessary to agree or disagree, these judgments should 1) always be qualified and 2) occur only in certain contexts . Instead of looking just at how you agree or disagree, try to imagine what these critics might say to one another. Looking at sources in this way may prove useful as you explore your topics further in depth.

Using Strategy #3:

This is a way for your sources to address one another directly, while also giving you more room to expand on your ideas through a slightly different form of analysis. For example: what might the person you interviewed think about the secondary sources you found? Would they agree with the claims you see your sources making, or would they disagree? Why – what about their interview suggests this? Make a list of possible dialogues your sources could have with one another.

Strategy 4: Find Your Own Role in the Conversation

v Even though it’s important to not be the only person in the essay agreeing and disagreeing with the texts, it is important that you establish what you think and feel about each source. After all, something compelled you to choose it, right? In general, you have two options when you are in agreement with a source. You can apply it in another context to qualify or expand its implications, or you can seek out other perspectives in order to break the hold it has on you. In the first option, to do this, instead of focusing on the most important point, choose a lesser yet equally interesting point and work on developing that idea to see if it holds relevance to your topic. The second option can also hold new perspectives if you allow yourself to be open to the possibilities of other perspectives that may or may not agree with your original source.

Using Strategy #4: While it’s important that you create a distinct voice for all the different kinds of sources you’ve used (interview, fieldwork, scholarly journals/books, etc.), it’s perhaps even more important that you have a clear role in this conversation that is your research essay. Look over your paper: is it clear what you think? Is it clear what is your voice, and what are the ideas/opinions of your sources? (Hint: your voice should still be clear in the midst of your sources, if you are taking the time to analyze them and develop your analysis as fully as possible.) Highlight places where you voice – what you think – is clear. Highlight in a different color places where your voice is unclear, or needs to be expressed more fully.

Strategy 5: Supply Ongoing Analysis of Sources (Don’t Wait Until the End)

v Instead of summarizing everything first and then leaving your analysis until the end, analyze as you quote or paraphrase a source . This will help yield good conversation, by integrating your analysis of your sources into your presentation of them.

Using Strateg y #5:

Are your sources presented throughout the paper with careful analysis attending to each one? Or are you presenting all your sources first, and analyzing them later? Look through your paper, and mark places where you see yourself not analyzing your sources as you go. Also: are there places where you see too much analysis, and not enough evidence? Be sure to mark those places as well.

Strategy 6: Attend Carefully to the Language of Your Sources by Quoting or Paraphrasing Them

v Rather than generalizing broadly about the ideas in your sources, you should spell out what you think is significant about their key words. Quote sources if the actual language they use is important to your point; this practice will help you to present the view of your source fairly and accurately. Your analysis will also benefit from the way the source represents its position (which may or may not be your position) with carefully chosen words and phrases. Take advantage of this, and use the exact language to discuss the relevance (or not) of the quote to the issue you’re using it for.

Using Strategy #6: When paraphrasing or quoting a source, it’s important that you use the language of the source to help explain it – it keeps the reader in the moment with you, and helps him/her understand the key terms of that source – why you chose, why these words are so important, etc. Look over your evidence, both quoted and paraphrased: are you using the language of the quote to help explain it? Or is your analysis removed from the “moment of the source” (i.e. the language which the source uses to illustrate its point)? Mark places where you think it’s important to use the language of the source to help analyze and develop the evidence more completely.

- Strategies for Using Quotes

- Floating Quotations

- How to Integrate Quotations

Attributed Quotations

Integrated Quotations

Strategies for Using Quotations In-Text

Acknowledge sources in your text, not just in citations:

“According to Lewis” or “Whitney argues.”

Use a set-up phrase, and splice the most important part of quotations in with your own words:

According to Paul McCartney, “All you need is love.”

Or phrase it with a set-up:

Patrick Henry’s famous phrase is one of the first American schoolchildren memorize:

“Give me liberty, or give me death.”

Anytime you use a quote, cite your source after the quotation:

Maxine Greene might attribute this resistance to “vaguely perceived expectations; they

allow themselves to be programmed by organizations and official schedules or forms” (43).

Use ellipses to shorten quotations:

“The album ‘OK Computer’ …pictured the onslaught of the information age and a young

person’s panicky embrace of it” (Ross 85) .

Use square brackets to alter or add information within a quotation:

Popular music has always “[challenged] the mores of the older generation,” according to

Nick Hornby.

Acc ording to Janet Gardner in her book Writing About Literature , there are three ways that we tend to use quotes:

Gardner advocates that we stay away from “floating quotations,” use at least an “attributed quotation,” and use “integrated quotations” as much as possible.

You will recognize a floating quotation when it looks as though the writer has simply lifted the passage from the original text, put quotations around it, and (maybe) identified the source.

Doing this can create confusion for the reader, who is left to guess the context and the reason for the quote.

This type of quoting reads awkward and choppy because there is no transition between your words and the language of the text you are quoting.

Example of a Floating Quotation; text taken from All She was Worth , by Miyuki Miyabe

Both Honma and Kyoko were rejected and looked down upon by Jun and Chizuko’s family when entering into marriage with their respective partners. “About her cousin – Jun’s father – and his family: what snobs they were, with fixed ideas on education and jobs” ( Miyabe 17).This passage shows that Honma and Kyoko were both being judged by their future in-laws by superficial stipulations.

- << Previous: Conclusions

- Next: Revision and Editing >>

- Last Updated: Mar 8, 2021 10:50 AM

- URL: https://guides.rider.edu/academic_writing

- Healey Library

- Research Guides

Primary Sources: A Research Guide

- Primary vs. Secondary

- Historical Newspapers

- Book Collections

- Find Videos

- Open Access

- Local Archives and Archival Societies

- University Archives and Special Collections at UMass Boston

Primary Sources

Texts of laws and other original documents.

Newspaper reports, by reporters who witnessed an event or who quote people who did.

Speeches, diaries, letters and interviews - what the people involved said or wrote.

Original research.

Datasets, survey data, such as census or economic statistics.

Photographs, video, or audio that capture an event.

Secondary Sources

Secondary Sources are one step removed from primary sources, though they often quote or otherwise use primary sources. They can cover the same topic, but add a layer of interpretation and analysis. Secondary sources can include:

Most books about a topic.

Analysis or interpretation of data.

Scholarly or other articles about a topic, especially by people not directly involved.

Documentaries (though they often include photos or video portions that can be considered primary sources).

When is a Primary Source a Secondary Source?

Whether something is a primary or secondary source often depends upon the topic and its use.

A biology textbook would be considered a secondary source if in the field of biology, since it describes and interprets the science but makes no original contribution to it.

On the other hand, if the topic is science education and the history of textbooks, textbooks could be used a primary sources to look at how they have changed over time.

Examples of Primary and Secondary Sources

Adapted from Bowling Green State University, Library User Education, Primary vs. Secondary Sources .

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Find Primary Sources >>

- Last Updated: May 1, 2024 7:22 PM

- URL: https://umb.libguides.com/PrimarySources

Philosophy: A Guide to Research

- About this Guide

- Getting Started with Research

- Finding Peer-Reviewed Articles

Primary & Secondary Sources

Tips for finding primary sources, books in milne library's reference collection, databases available through milne library, websites for primary sources.

- Finding a Book at Milne Library

- Citations This link opens in a new window

- Get Library Help

- Self-Guided Tour of the James M. Milne Library

- SUNY Oneonta Philosophy Department This link opens in a new window

Primary sources are documents or objects that provide direct, first-hand evidence. A secondary source analyzes, discusses, summarizes, and comments upon primary sources. Secondary sources are one step removed from the original, primary source.

Disciplines define primary sources differently. To the scientist, they might be reports of original research or personal papers; to the journalist, they might be interviews or letters.

In Philosophy, examples of primary sources can include:

- philosophical texts, treatises, meditations

- personal narratives, diaries, memoirs, correspondence, letters

( Primary Sources - Philosophy - Subject Guides at University of Alberta Libraries (ualberta.ca) available under a Creative Commons — Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International — CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 )

Examples of secondary sources include:

- biographies

- critical analysis

- second-person account

- historical study

- journal article summarizing or examining previous findings

Primary sources may be available in print, in library databases, on websites, or in microform collections. Print primary sources, or print reproductions of primary sources, are sometimes available in archives and libraries. In addition, primary sources are increasingly found online in digitized form. These may be found in library databases or on websites. Primary sources are also available in m icroform, a format that has been used for many years to preserve documents, as well as to save storage space.

Tips for finding primary sources:

When searching print and online access tools use search terms such as SOURCES , CORRESPONDENCE , PERSONAL NARRATIVES , DIARIES , RECORDS AND CORRESPONDENCE , SERMONS , SPEECHES , PAPERS , LETTERS.

Look for titles of primary sources in secondary sources and in lists included in bibliographies of secondary sources. Use text, class, and library bibliographies for recommended titles or listings of primary sources.

Browse library shelves around other relevant books. This is often a wonderful way to discover collections of primary sources that have been published in a book format.

On this guide you will find a partial listing of primary source materials available in Milne Library. This includes a listing of reference books , databases , websites , and microform collections containing primary source materials. Remember, this is only a partial listing. More primary sources can be found through searching print and online access tools and browsing the library shelves in relevant areas.