50 Useful Academic Words & Phrases for Research

Like all good writing, writing an academic paper takes a certain level of skill to express your ideas and arguments in a way that is natural and that meets a level of academic sophistication. The terms, expressions, and phrases you use in your research paper must be of an appropriate level to be submitted to academic journals.

Therefore, authors need to know which verbs , nouns , and phrases to apply to create a paper that is not only easy to understand, but which conveys an understanding of academic conventions. Using the correct terminology and usage shows journal editors and fellow researchers that you are a competent writer and thinker, while using non-academic language might make them question your writing ability, as well as your critical reasoning skills.

What are academic words and phrases?

One way to understand what constitutes good academic writing is to read a lot of published research to find patterns of usage in different contexts. However, it may take an author countless hours of reading and might not be the most helpful advice when faced with an upcoming deadline on a manuscript draft.

Briefly, “academic” language includes terms, phrases, expressions, transitions, and sometimes symbols and abbreviations that help the pieces of an academic text fit together. When writing an academic text–whether it is a book report, annotated bibliography, research paper, research poster, lab report, research proposal, thesis, or manuscript for publication–authors must follow academic writing conventions. You can often find handy academic writing tips and guidelines by consulting the style manual of the text you are writing (i.e., APA Style , MLA Style , or Chicago Style ).

However, sometimes it can be helpful to have a list of academic words and expressions like the ones in this article to use as a “cheat sheet” for substituting the better term in a given context.

How to Choose the Best Academic Terms

You can think of writing “academically” as writing in a way that conveys one’s meaning effectively but concisely. For instance, while the term “take a look at” is a perfectly fine way to express an action in everyday English, a term like “analyze” would certainly be more suitable in most academic contexts. It takes up fewer words on the page and is used much more often in published academic papers.

You can use one handy guideline when choosing the most academic term: When faced with a choice between two different terms, use the Latinate version of the term. Here is a brief list of common verbs versus their academic counterparts:

Although this can be a useful tip to help academic authors, it can be difficult to memorize dozens of Latinate verbs. Using an AI paraphrasing tool or proofreading tool can help you instantly find more appropriate academic terms, so consider using such revision tools while you draft to improve your writing.

Top 50 Words and Phrases for Different Sections in a Research Paper

The “Latinate verb rule” is just one tool in your arsenal of academic writing, and there are many more out there. But to make the process of finding academic language a bit easier for you, we have compiled a list of 50 vital academic words and phrases, divided into specific categories and use cases, each with an explanation and contextual example.

Best Words and Phrases to use in an Introduction section

1. historically.

An adverb used to indicate a time perspective, especially when describing the background of a given topic.

2. In recent years

A temporal marker emphasizing recent developments, often used at the very beginning of your Introduction section.

3. It is widely acknowledged that

A “form phrase” indicating a broad consensus among researchers and/or the general public. Often used in the literature review section to build upon a foundation of established scientific knowledge.

4. There has been growing interest in

Highlights increasing attention to a topic and tells the reader why your study might be important to this field of research.

5. Preliminary observations indicate

Shares early insights or findings while hedging on making any definitive conclusions. Modal verbs like may , might , and could are often used with this expression.

6. This study aims to

Describes the goal of the research and is a form phrase very often used in the research objective or even the hypothesis of a research paper .

7. Despite its significance

Highlights the importance of a matter that might be overlooked. It is also frequently used in the rationale of the study section to show how your study’s aim and scope build on previous studies.

8. While numerous studies have focused on

Indicates the existing body of work on a topic while pointing to the shortcomings of certain aspects of that research. Helps focus the reader on the question, “What is missing from our knowledge of this topic?” This is often used alongside the statement of the problem in research papers.

9. The purpose of this research is

A form phrase that directly states the aim of the study.

10. The question arises (about/whether)

Poses a query or research problem statement for the reader to acknowledge.

Best Words and Phrases for Clarifying Information

11. in other words.

Introduces a synopsis or the rephrasing of a statement for clarity. This is often used in the Discussion section statement to explain the implications of the study .

12. That is to say

Provides clarification, similar to “in other words.”

13. To put it simply

Simplifies a complex idea, often for a more general readership.

14. To clarify

Specifically indicates to the reader a direct elaboration of a previous point.

15. More specifically

Narrows down a general statement from a broader one. Often used in the Discussion section to clarify the meaning of a specific result.

16. To elaborate

Expands on a point made previously.

17. In detail

Indicates a deeper dive into information.

Points out specifics. Similar meaning to “specifically” or “especially.”

19. This means that

Explains implications and/or interprets the meaning of the Results section .

20. Moreover

Expands a prior point to a broader one that shows the greater context or wider argument.

Best Words and Phrases for Giving Examples

21. for instance.

Provides a specific case that fits into the point being made.

22. As an illustration

Demonstrates a point in full or in part.

23. To illustrate

Shows a clear picture of the point being made.

24. For example

Presents a particular instance. Same meaning as “for instance.”

25. Such as

Lists specifics that comprise a broader category or assertion being made.

26. Including

Offers examples as part of a larger list.

27. Notably

Adverb highlighting an important example. Similar meaning to “especially.”

28. Especially

Adverb that emphasizes a significant instance.

29. In particular

Draws attention to a specific point.

30. To name a few

Indicates examples than previously mentioned are about to be named.

Best Words and Phrases for Comparing and Contrasting

31. however.

Introduces a contrasting idea.

32. On the other hand

Highlights an alternative view or fact.

33. Conversely

Indicates an opposing or reversed idea to the one just mentioned.

34. Similarly

Shows likeness or parallels between two ideas, objects, or situations.

35. Likewise

Indicates agreement with a previous point.

36. In contrast

Draws a distinction between two points.

37. Nevertheless

Introduces a contrasting point, despite what has been said.

38. Whereas

Compares two distinct entities or ideas.

Indicates a contrast between two points.

Signals an unexpected contrast.

Best Words and Phrases to use in a Conclusion section

41. in conclusion.

Signifies the beginning of the closing argument.

42. To sum up

Offers a brief summary.

43. In summary

Signals a concise recap.

44. Ultimately

Reflects the final or main point.

45. Overall

Gives a general concluding statement.

Indicates a resulting conclusion.

Demonstrates a logical conclusion.

48. Therefore

Connects a cause and its effect.

49. It can be concluded that

Clearly states a conclusion derived from the data.

50. Taking everything into consideration

Reflects on all the discussed points before concluding.

Edit Your Research Terms and Phrases Before Submission

Using these phrases in the proper places in your research papers can enhance the clarity, flow, and persuasiveness of your writing, especially in the Introduction section and Discussion section, which together make up the majority of your paper’s text in most academic domains.

However, it's vital to ensure each phrase is contextually appropriate to avoid redundancy or misinterpretation. As mentioned at the top of this article, the best way to do this is to 1) use an AI text editor , free AI paraphrasing tool or AI proofreading tool while you draft to enhance your writing, and 2) consult a professional proofreading service like Wordvice, which has human editors well versed in the terminology and conventions of the specific subject area of your academic documents.

For more detailed information on using AI tools to write a research paper and the best AI tools for research , check out the Wordvice AI Blog .

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

Useful Research Words and Phrases for All Sections

What are the best research words and phrases to use in a paper?

If you are a graduate student, researcher, and/or professor, you already know that composing academic documents can be a frustrating and time-consuming undertaking. In addition to including all the necessary study content, you must also present it in the right order and convey the required information using the proper institutional language. Deciding exactly which language to put in which section can get confusing as you constantly question your choice of phrasing: “ Does the Results section require this kind of explanation? Should I introduce my research with a comparison or with background research? How do I even begin the Discussion section? ”

To help you choose the right word for the right purpose, Wordvice has created a handy academic writing “cheat sheet” with ready-made formulaic expressions for all major sections of a research paper ( Introduction, Literature Review, Methods, Results, Discussion, and Conclusion ) and for reaching different objectives within each section.

This downloadable quick-reference guide contains common phrases used in academic papers, a sample journal submission cover letter, and a template rebuttal letter to be modified and used in case of receipt of a letter from the journal editor.

Each section includes annotations explaining the purposes of the expressions and a summary of essential information so that you can easily find the language your are looking for whenever you need to apply it to your paper. Using this quick reference will help you write more complete and appropriate phrases in your research writing and correspondence with journal editors.

Reference Guide Content

1. common research paper phrases (listed by manuscript section).

- Gathered from hundreds of thousands of published manuscripts, these frequently used key sentences and phrases are tailored to what each section of your paper should accomplish.

- From the abstract to the conclusion, each section is tied together by a logical structure and flow of information.

- Refer to this index when you are unsure of the correct phrases to use (in your paper/article, dissertation, or thesis) or if you are a non-native speaker and are seeking phrasing that is both natural in tone and official in form.

2. Acade mic Search Tools Index

- The search tools index is a concise compilation of some of the best academic research search tools and databases available that contain information about paper composition and relevant journals.

- Locate the sites and tools most useful for your needs using our summary of site content and features.

3. Sample Journal Submission Cover Letter with Formal Expressions

The cover letter is an essential part of the journal submission process, yet a great many researchers struggle with how to compose their cover letters to journal editors in a way that will effectively introduce their study and spur editors to read and consider their manuscript.

This sample cover letter not only provides an exemplary model of what a strong cover letter should look like but includes template language authors can apply directly to their own cover letters. By applying the formal language of the cover letter to the particular details of a particular study, the letter helps authors build a strong opening case for journals to consider accepting their manuscripts for publication.

4. Rebuttal Letter Template

The rebuttal letter is written as a response to previously received correspondence from journal editors that can take the form of a rejection, deferment, or request letter, which often requests changes, additions, or omission of content or augmentation of formatting in the manuscript. The rebuttal letter is therefore usually an author’s last chance to get their manuscript published in a given journal, and the language they use must convince the editor that an author’s manuscript is ready (or will be ready) for publication in their journal. It must therefore contain a precise rationale and explanation to accomplish this goal.

As with the journal submission cover letter, knowing exactly what to include in this letter and how to compose it can be difficult. One must be persuasive without being pushy; formal but yet candid and frank. This template rebuttal letter is constructed to help authors navigate these issues and respond to authors with confidence that they have done everything possible to get their manuscript published in the journal to which they have submitted.

5. Useful Phrases for the Journal Submission Cover Letter/Rebuttal Letter

As with research papers, there are usually dozens of options for how to phrase the language in letters to journal editors. This section suggests several of the most common phrases that authors use to express their objectives and persuade editors to publish their journals. And as with the section on “Common Research Paper Phrases,” you will find here that each phrase is listed under a heading that indicates its objective so that authors know when and where to apply these expressions.

Use this reference guide as another resource in your toolkit to make the research paper writing and journal submission processes a bit easier. And remember that there are many excellent resources out there if you require additional assistance.

Wordvice ‘s academic English editing services include paper editing services , dissertation editing services , and thesis editing services that are specifically tailored to help researchers polish their papers to get the very most out of their research writing. Visit our Resources pages for great articles and videos on academic writing and journal submission.

Wordvice Resources

A guide to paraphrasing in research papers, 100+ strong verbs that will make your research writing amazing , how to compose a journal submission cover letter, how to write the best journal submission cover letter, related resources, 40 useful words and phrases for top-notch essays, “essential academic writing words and phrases” (my english teacher.eu), “academic vocabulary, useful phrases for academic writing and research paper writing” (research gate).

Training videos | Faqs

Useful Phrases and Sentences for Academic & Research Paper Writing

Overview | Abstract | Introduction | Literature Review | Materials & Methods | Results & Discussion | Conclusion & Future Work | Acknowledgements & Appendix

1. Abstract

An abstract is a self-contained and short synopsis that describes a larger work. The abstract is the only part of the paper that is published online and in most conference proceedings. Hence abstract constitutes a very important section of your paper. Also, when you submit your paper to a journal, potential reviewers only see the abstract when invited by an editor to review a manuscript. The abstract should include one or two lines briefly describing the topic, scope, purpose, results, and conclusion of your work. The abstract is indexed by search engines, so make sure that it has all the right words that a fellow researcher in the same field will be using while searching for articles online. Also, make sure it is rich with data and numbers to demonstrate the scientific rigor of your article. Be very clear and confident about your findings. Keep it punchy and straight to the point.

The abstract section of your research paper should include the following:

Click here for the academic phrases and vocabulary for the abstract section of the research paper…

2. Introduction

Introduction section comes after the abstract. Introduction section should provide the reader with a brief overview of your topic and the reasons for conducting research. The introduction is a perfect place to set the scene and make a good first impression. Regarding word count, introduction typically occupies 10-15% of your paper, for example, if the total word count of your paper is 3000, then you should aim for an introduction of around 600 words. It is often recommended that the introduction section of the paper is written after finishing the other sections of the paper. This is because it is difficult to figure out what exactly to put in the introduction section of the paper until you have seen the big picture. Sound very confident about your chosen subject area and back up your arguments with appropriate references. After reading the introduction, the reader must have a clear idea of what to expect from the rest of your research paper.

The introduction section of your research paper should include the following:

- General introduction

- Problem definition

- Gaps in the literature

- Problems solution

- Study motivation

- Aims & objectives

- Significance and advantages of your work

Click here for the academic phrases and vocabulary for the introduction section of the research paper…

3. Literature review

The literature review should clearly demonstrate that the author has a good knowledge of the research area. Literature review typically occupies one or two passages in the introduction section. A well-written literature review should provide a critical appraisal of previous studies related to the current research area rather than a simple summary of prior works. The author shouldn’t shy away from pointing out the shortcomings of previous works. However, criticising other’s work without any basis can weaken your paper. This is a perfect place to coin your research question and justify the need for such a study. It is also worth pointing out towards the end of the review that your study is unique and there is no direct literature addressing this issue. Add a few sentences about the significance of your research and how this will add value to the body of knowledge.

The literature review section of your research paper should include the following:

- Previous literature

- Limitations of previous research

- Research questions

- Research to be explored

Click here for the academic phrases and vocabulary for the literature review section of the research paper…

4. Materials and Methods

The methods section that follows the introduction section should provide a clear description of the experimental procedure, and the reasons behind the choice of specific experimental methods. The methods section should be elaborate enough so that the readers can repeat the experimental procedure and reproduce the results. The scientific rigor of the paper is judged by your materials and methods section, so make sure you elaborate on all the fine details of your experiment. Explain the procedures step-by-step by splitting the main section into multiple sub-sections. Order procedures chronologically with subheadings. Use past tense to describe what you did since you are reporting on a completed experiment. The methods section should describe how the research question was answered and explain how the results were analyzed. Clearly explain various statistical methods used for significance testing and the reasons behind the choice.

The methods section of your research paper should include the following:

- Experimental setup

- Data collection

- Data analysis

- Statistical testing

- Assumptions

- Remit of the experiment

Click here for the academic phrases and vocabulary for the methods section of the research paper…

5. Results and Discussion

The results and discussion sections are one of the challenging sections to write. It is important to plan this section carefully as it may contain a large amount of scientific data that needs to be presented in a clear and concise fashion. The purpose of a Results section is to present the key results of your research. Results and discussions can either be combined into one section or organized as separate sections depending on the requirements of the journal to which you are submitting your research paper. Use subsections and subheadings to improve readability and clarity. Number all tables and figures with descriptive titles. Present your results as figures and tables and point the reader to relevant items while discussing the results. This section should highlight significant or interesting findings along with P values for statistical tests. Be sure to include negative results and highlight potential limitations of the paper. You will be criticized by the reviewers if you don’t discuss the shortcomings of your research. This often makes up for a great discussion section, so do not be afraid to highlight them.

The results and discussion section of your research paper should include the following:

- Comparison with prior studies

- Limitations of your work

- Casual arguments

- Speculations

- Deductive arguments

Click here for the academic phrases and vocabulary for the results and discussion section of the research paper…

6. Conclusion and Future Work

A research paper should end with a well-constructed conclusion. The conclusion is somewhat similar to the introduction. You restate your aims and objectives and summarize your main findings and evidence for the reader. You can usually do this in one paragraph with three main key points, and one strong take-home message. You should not present any new arguments in your conclusion. You can raise some open questions and set the scene for the next study. This is a good place to register your thoughts about possible future work. Try to explain to your readers what more could be done? What do you think are the next steps to take? What other questions warrant further investigation? Remember, the conclusion is the last part of the essay that your reader will see, so spend some time writing the conclusion so that you can end on a high note.

The conclusion section of your research paper should include the following:

- Overall summary

- Further research

Click here for the academic phrases and vocabulary for the conclusions and future work sections of the research paper…

7. Acknowledgements and Appendix

There is no standard way to write acknowledgements. This section allows you to thank all the people who helped you with the project. You can take either formal or informal tone; you won’t be penalized. You can place supplementary materials in the appendix and refer to them in the main text. There is no limit on what you can place in the appendix section. This can include figures, tables, costs, budget, maps, etc. Anything that is essential for the paper but might potentially interrupt the flow of the paper goes in the appendix.

Click here for the academic phrases and vocabulary for the acknowledgements and appendix sections of the research paper…

Similar Posts

Writing a Medical Clinical Trial Research Paper – Example & Format

In this blog, we will teach you step-by-step how to write a clinical trial research paper for publication in a high quality scientific journal.

Academic Phrases for Writing Acknowledgements & Appendix Sections of a Research Paper

In this blog, we discuss phrases related to thanking colleagues, acknowledging funders and writing the appendix section.

Introduction Paragraph Examples and Writing Tips

In this blog, we will go through a few introduction paragraph examples and understand how to construct a great introduction paragraph for your research paper.

Academic Phrases for Writing Literature Review Section of a Research Paper

In this blog, we discuss phrases related to literature review such as summary of previous literature, research gap and research questions.

Results Section Examples and Writing Tips

In this blog, we will go through many results section examples and understand how to write a great results section for your paper.

Conclusion Section Examples and Writing Tips

In this blog, we will go through many conclusion examples and learn how to present a powerful final take-home message to your readers.

Thanks for your effort. could I have a PDF having all the info included here.

You can control + p and save as pdf

- Pingback: Scholarly Paraphrasing Tool and Essay Rewriter for Rewording Academic Papers - Ref-N-Write: Scientific Research Paper Writing Software Tool - Improve Academic English Writing Skills

thank you so much

if you can also add on verbs used for each section would be good further

First of all, Thanks! I really appreciate the time and effort you put into http://www.intoref-n-write.com/trial/how-to-write-a-research-paper-academic-phrasebank-vocabulary/ ) which have greatly enhanced understanding of “how-to-write-a-research-paper”.

Thank you very much for this 🙂

Thank you very much!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- 22 Share Facebook

- 26 Share Twitter

- 24 Share LinkedIn

- 37 Share Email

- Lawrence W. Tyree Library

- Library How-To Guides

*Research 101

Library and research vocabulary.

- Developing a Topic

- How to Search

- Books & eBooks

- Popular vs. Scholarly Articles

- Internet Sources

- Writing Resources

- Organizing & Citing Sources

- Research Beyond SF

As you use the library or do research, there are specialized terms and words you will find. This list includes the more common words you will find, along with a definition.

Vocabulary List

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Developing a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Mar 18, 2024 5:08 PM

- URL: https://sfcollege.libguides.com/research101

Commitment to Equal Access and Equal Opportunity

Santa Fe College is committed to an environment that embraces diversity, respects the rights of all individuals, is open and accessible, and is free of harassment and discrimination. For more information, visit sfcollege.edu/eaeo or contact [email protected] .

SACSCOC Accreditation Statement

Santa Fe College is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC). For more information, visit sfcollege.edu/sacscoc .

- Resources Research Proposals --> Industrial Updates Webinar - Research Meet

- Countries-Served

- Add-on-services

Text particle

feel free to change the value of the variable "message"

Guidelines for Researchers to Improve their Academic Vocabulary

Vocabulary knowledge helps people discover new ideas, appreciate the beauty of language, and learn about the world. A strong vocabulary strengthens what a person wants to say, especially when they want to write anything. It is evident that an educated person has a broad and varied vocabulary. One way to guarantee that there are consistent practices in all courses and that there is a cumulative effect on participant vocabulary development across topics and over time is to have a school-wide or district-wide commitment to research-based vocabulary training.

What is common academic vocabulary?

Common academic vocabulary represents words and phrases you find in essays, academic papers, textbooks and articles across all fields. Some examples of these words are: analyze, constitute, derive, source, theorize and evidence.

Why is it important in research?

Nonfiction and technical books will quickly teach you new ways to think and speak with words you may be unfamiliar with, but any type of reading will help you along. It facilitates effective communication amongst researchers using the right vocabulary. The ability to understand word meanings is acknowledged as one of the key components to becoming proficient in reading, writing, listening, speaking and comprehension.

Some interesting strategies for learning academic vocabulary

Reading is Everything

The majority of people read every day for at least a portion of their time. While reading, you will find out a ton of unknown words. Your vocabulary abilities will increase through learning vocabulary that is particular to your field from sources including subject guides, reading lists, and textbooks as well as from endorsed websites and journals.

Word identification

Many words have the same or very similar meanings. To make fresh and original remarks in your writing and speaking, you can make a list of word groups. It’s helpful to check the definitions of related words before using them because some words have similar meanings but aren’t necessarily interchangeable. You can sound more polished and professional by changing the words you use in your writing.

Word Selection

Word choice is important. Consider terms that are crucial to comprehending the primary idea of the text or unit, are used often, or are regularly encountered across domains when choosing which words to target for explicit instruction.

Learn Roots

The development of strong vocabulary benefits from knowledge of word origins. A prefix or suffix on a lot of words with a common origin can help you determine what they might mean. The more roots you study, the more words that use that root you will be able to comprehend.

Create a word Journal

A word journal is one place (a notebook, a computer document, etc.) where you write down words you don’t know.

keeping a word journal involves the following steps:

- To create a definition that you can fully understand.

- Exactly where you found the word in the sentence, copy it.

- Provide a unique explanation of that word in your writing.

Vocabulary Map

When creating a vocabulary map, you draw a circle around a word in the center of your computer document and connect it to other words or concepts. Include synonyms, antonyms, or examples of the word among the words or ideas on your map.

When writing the first draft of your academic work, use academic language in your essays and papers. Check to verify if the academic language is used correctly as you update your paper. Your academic writing will improve by including general and subject-specific academic terminology in essays and research papers. It demonstrates to readers that you are well-versed in the subject of your writing. Additionally, using these terms allows you to express yourself clearly and precisely. The appropriate vocabulary mix raises the quality of your articles and papers.

Hence, Increasing your vocabulary enables you to utilize the appropriate word, which shows that you comprehend and are familiar with the accepted terms of a given discipline.

https://bozemanmagazine.com/news/2020/11/24/109317-how-to-improve-vocabulary-for-research-writing .

https://www.academicwritingsuccess.com/5-unique-ways-boost-academic-vocabulary-elevate-academic-essays/

https://www.texasldcenter.org/teachers-corner/five-research-based-ways-to-teach-vocabulary

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Academic Vocabulary Use in Doctoral Theses: A Corpus-Based Lexical Analysis of Academic Word List (AWL) in Major Scientific Disciplinary Groups

2018, International Journal of English Linguistics

Related Papers

khalil Tazik

In the past few years, several cross-disciplinary corpus-based studies have been carried out on the frequency and coverage of 570 word families from Coxhead's (2000) academic word list (AWL). Some reported high coverage of this word list in their corpuses while some others questioned its generality and stated that this word list is far from complete. Hence, along with these studies, the present study attempted to examine the word frequency and text coverage of AWL on 80 research articles (RAs) written in English with 320310 running words across two Asian EFL and ESP journals. Using frequency and range as the criteria for word form selection, this study identified 438 words as the academic words and 144 new added academic words to the list which was called revised academic word list (RAWL). Applying both AWL and RAWL into the entire corpus, results support high coverage and importance of academic words in both ESP and EFL RAs. However, when two word lists were examined into ESP corpus (ESPC) and EFL corpus (EFLC) separately, academic words had higher coverage in ESPC than EFLC. From these findings it is concluded that (1) academic words play an important role in academic texts; therefore, acquisition of them seems to be essential for language learners and users, (2) because of the nature of ESP articles, ESPC holds higher coverage of academic words, (3) some of the words included in the AWL are field-specific and (4) direct attention to these words from behalf of the material and syllabus designers and teachers can lead to a better understanding of these words ;hence, students' development in their writing and reading.

LSP International Journal

Hadina Habil

In measuring the quality of written text, especially academic writing, lexical features are as important as grammatical features and should not be ignored. The highly computable nature of lexicons can make them a good criterion for determining and measuring the quality of text. In this article three lexical features: lexical density, complexity, and formality are reviewed and justified as measurement tools of academic texts. Furthermore, a measurement method is offered to evaluate lexical complexity level of an academic text.

Journal of Quantitative Linguistics

Shuyi Amelia Sun

This study employed a text mining method to investigate the lexical features and their dynamic changes of PhD theses across the natural sciences, social sciences and humanities. Four quantitative indices, i.e. TTR, h-point, R1 and writer's view, were employed to analyze 150 PhD theses (50 theses from each discipline). Although h-point and writer's view were found counter-intuitively to show insignificant variation across disciplines, the results of TTR and R1 did reveal sharp contrasts between theses in humanities and natural sciences. While the second half of humanities theses showed a significantly higher level of lexical diversity, indicated by higher TTR, theses in natural sciences tended to be richer in content words in the first half, indicated by a higher R1. Meanwhile, theses in social sciences seemed to be more moderate, with features lying in the middle position. This study has implications not only for the widening of applications of quantitative linguistic methods but also for academic writing (especially PhD thesis writing) instruction and practice.

Magali Paquot

Research in Corpus Linguistics

Geraint P Rees

– This study examines the validity of the rationale underlying recent trends towards discipline-specific and phraseological approaches to vocabulary selection for English for Academic Purposes (EAP) courses. It examines the behaviour of Coxhead's (2000) New Academic Wordlist (AWL) using a 2,795,031 word corpus compiled from journal articles taken from the disciplines of History, Microbiology, and Management Studies. A two-stage method of analysis is employed. Firstly, coverage statistics for all AWL word families and their members are compared across the History, Microbiology, and Management Studies sub-corpora. This suggests difference in language use across disciplines. This difference is investigated further in a second stage of analysis which employs the Sketch Engine (Kilgarriff et al. 2004) Word Sketch Difference tool and Corpus Pattern Analysis (Hanks 2004) techniques to examine the collocational behaviour of a sample of 57 AWL headwords across the three sub-corpora. The results demonstrate that a large number of the AWL words have discipline-specific meanings, and that these meanings are conditioned by the syntagmatic context of the AWL item.

Applications of Language Teaching

Is'haaq Akbarian

CORPORUM: Journal of Corpus Linguistics

Rana Kashif Shakeel

The present study aims at compiling a Literary Academic Word List (LAWL) based on the HEC recognized Pakistani journals of English literature published from 2010 to 2019. A corpus consisting 215734 words with 16362 word forms was manually filtered to extract the most frequently used vocabulary items in 40 literature based research papers. The acquired wordlist (LAWL) of 766 words with a high frequency list (HFLAWL) consisting 20 words were chosen for critical analysis and discussion, considering the short and long contexts of the concordance lines and the external sources like key literary works. The results indicated that the selected timeframe was the period of frequent application of literary theories and critical approaches in Pakistani academic and research circles. The findings further stress the need for the compilation of subject specific word lists not only for literature but also for linguistics and other branches of knowledge. Finally, it is hoped that the availability of LAWL is going to be a significant contribution to the general process of learning English and to the specific process of exploring literary vocabulary in a robust manner.

Risky Ramdhani

Vocabulary profile can be used to identify the uniqueness of certain texts among sub-genres. In this study, some types of vocabularies are examined. The study aimed at identifying vocabulary profile consisting of General Service List (GSL) and Academic Word List (AWL) in three different subgenres of English major. This study used a qualitative method in identifying the elaboration on frequency of GSL and AWL as well as the dominant words emerging in 30 thesis abstracts. The thesis abstracts were retrieved from Linguistics, Cultural Studies, and Literature sub-genres. Only abstracts with A or AB score published from 2015 to 2016 were used. Based on types and tokens of GSL, it was found that Linguistics and Literature have higher number than Cultural Studies. For overall GSL, Linguistics covers more GSL compared to the other two subgenres. One of reasons to this case is because there are many plural forms of the same words used in the texts. In terms of AWL, Cultural Studies posseses ...

Luiz Mesquita

RELATED PAPERS

Journal of Economic Research and Policies

Reihaneh Gaskari

… of the 26th International Conference on …

Elisa Baniassad

Journal of Materials Science

Senthil Kumar Pandian

Sándor Sánta

- Cognitive Science

Nicholas Lester

International Journal of Mobile Computing and Multimedia Communications

Teddy Mantoro

Juan Sebastian Rojas

Benny Maruli

Emirates Journal of Food and Agriculture

Pluralidade de Temas e Aportes Teórico-Metodológicos na Pesquisa em História 4

Caio Teixeira

Journal of High Energy Physics

Sayeh Rajabi

Journal of Seed Science

Silvio M Cícero

International Journal of Advanced Research

moses fayiah

Revista de ALCESXXI: Journal of Contemporary Spanish Literature & Film

Fernando Sánchez López

International Journal of Plant, Animal and Environmental Sciences

Cuadernos de economía

Ruth Mateos

Benjamin Rott

Acta medica Lituanica

Vaidutis Kučinskas

Mateusz Pudłowski

Fortune Journals

Journal of Environment and Earth Science

DR NOR EEDA ALI

The European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences

SOON AUN TAN

Physical Review A

Pablo gonzalez

Arthritis research & therapy

Faten Mohamed

Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling

Irini Doytchinova

See More Documents Like This

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

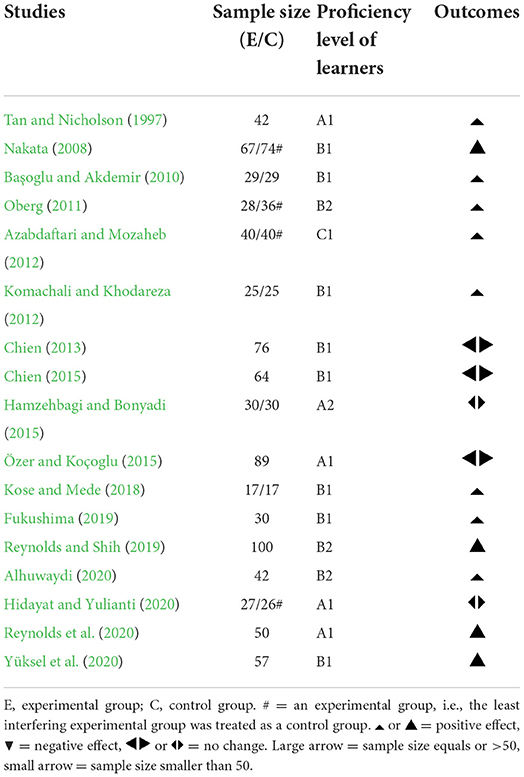

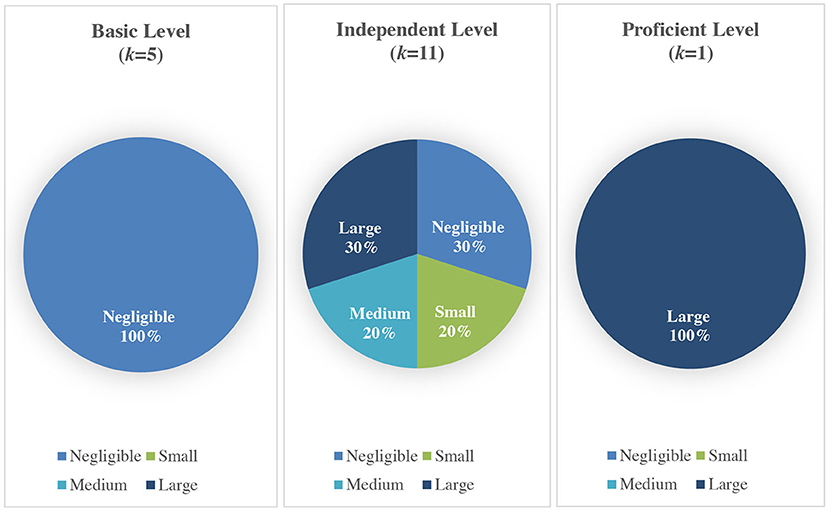

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Learning english vocabulary from word cards: a research synthesis.

- 1 Faculty of Education, University of Macau, Taipa, Macao SAR, China

- 2 Centre for Cognitive and Brain Sciences, University of Macau, Taipa, Macao SAR, China

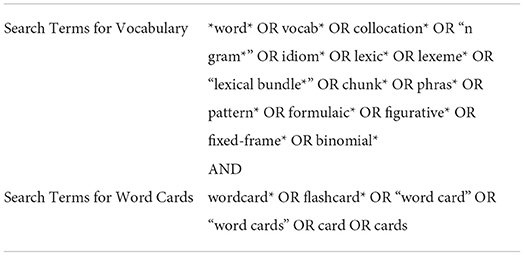

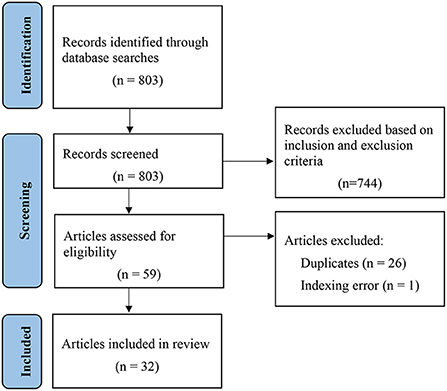

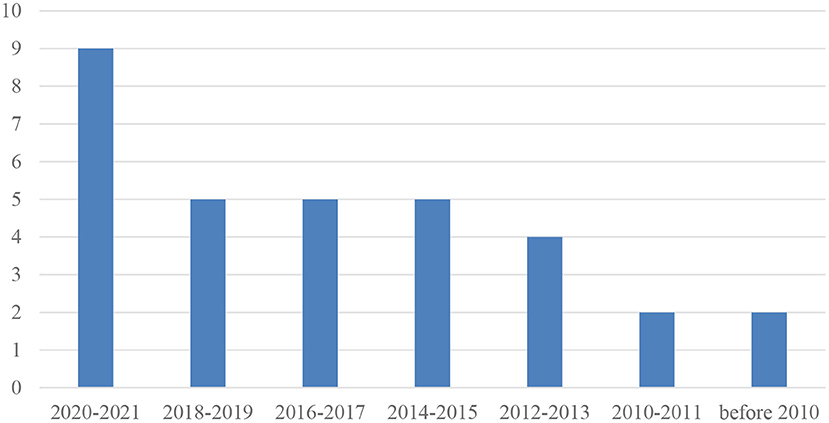

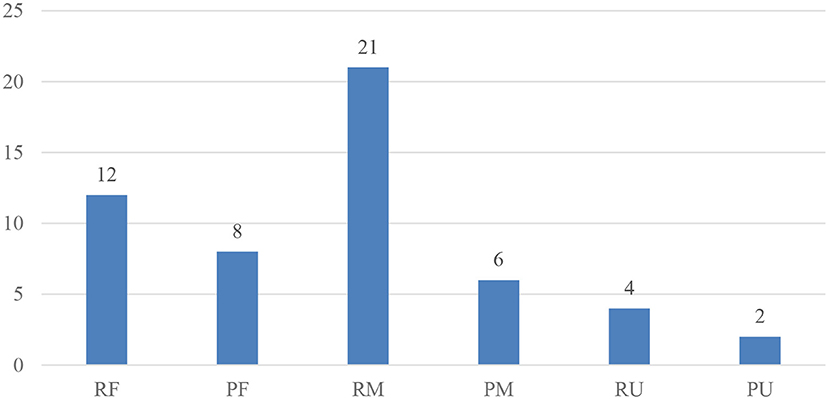

Researchers' interest in the learning of vocabulary from word cards has grown alongside the increasing number of studies published on this topic. While meta-analyses or systematic reviews have been previously performed, the types of word cards investigated, and the number of word card studies analyzed were limited. To address these issues, a research synthesis was conducted to provide an inclusive and comprehensive picture of how the use of word cards by learners results in vocabulary learning. A search of the Web of Science and Scopus databases resulted in 803 potential studies, of which 32 aligned with the inclusion criteria. Coding of these studies based on an extensive coding scheme found most studies assessed receptive vocabulary knowledge more often than productive vocabulary knowledge, and knowledge of vocabulary form and meaning were assessed more often than knowledge of vocabulary use. Results of effect size plots showed that more of the reviewed studies showed larger effects for the use of paper word cards than digital word cards, and for the use of ready-made word cards than self-constructed word cards. Results also indicated more studies showed larger effects for using word cards in an intentional learning condition compared with an incidental learning condition, and for using word cards in a massed learning condition compared with a spaced learning condition. Although a correlation was found between time spent using word cards and vocabulary learning outcomes, this correlation was not statistically significant. Learners that were more proficient in English learned more words from using word cards than those less proficient. These results suggest that future researchers should report learner proficiency, adopt reliable tests to assess vocabulary learning outcomes, compare the effectiveness of ready-made word cards and self-constructed word cards, and investigate the learning of different aspects of word knowledge. Teachers should provide learners guidance in how to use word cards and target word selection for self-construction of word cards. In addition, teachers should encourage learners to create word cards for incidentally encountered unknown words and use massed learning when initially working with these new words before using spaced learning for later retrieval practice.

Introduction

Vocabulary knowledge is essential in second language (L2) learning ( Barkat and Aminafshar, 2015 ; Reynolds and Shih, 2019 ). When learning English as a second language, acquiring vocabulary is “more important than mastering other language skills,” such as listening, speaking, reading, and writing ( Lukas et al., 2020 , p. 305). This is because vocabulary “acts as the foundation for learners to communicate” using the language ( Lukas et al., 2020 , p. 305). Learning a second language (L2) involves the learning of thousands of words ( Laufer and Hulstijn, 2001 ; Nation, 2013a ). In order to understand novels, newspapers, and spoken English, a vocabulary size of “3,000 to 4,000 word families” is needed ( Nation, 2013a , p. 14). Researchers, teachers, and learners are interested in knowing the most direct route to learn so many words to be able to use language for these and other purposes.

Learners often engage in different activities and use different strategies to learn vocabulary. Vocabulary-learning activities are often compared to determine which activity is most effective. It is advantageous to learn vocabulary from word cards. For example, Webb et al. (2020 , p. 16) suggested that word cards lead to “relatively large gains” in vocabulary knowledge compared to studying word lists. The strength of learning vocabulary from word cards comes from the fact that this activity is focused, efficient, and effective ( Nation, 2013a ). It is focused because “more attention can easily be paid to unknown words with the use of word cards” ( Reynolds et al., 2020 , p. 3). It is efficient because a large number of words “can be learned in a short time” using word cards ( Nation, 2013a , p. 439). It is effective because word cards can be used for both “receptive and productive learning” ( Nation and Webb, 2011 , p. 41). Moreover, learners have been shown to prefer learning vocabulary from word cards compared to other vocabulary learning activities (e.g., Kuo and Ho, 2012 ). Therefore, word cards were chosen as the focus of the synthesis among a variety of vocabulary learning activities available to learners.

Although there is generally a consensus that learning vocabulary from word cards is advantageous, one must acknowledge other variables could enhance or reduce their effectiveness. Previous researchers have indicated that many variables affect vocabulary learning outcomes regardless of the vocabulary learning strategy employed by learners. For most intentional vocabulary learning strategies—including the use of word cards—these include how the strategy is employed (e.g., Uchihara et al., 2019 ) and language learner proficiency (e.g., Webb et al., 2020 ). More specifically for word card use, these include aspects of word knowledge (e.g., Nation, 2013a , Ch. 11) and types of word cards (e.g., Chen and Chan, 2019 ; Reynolds et al., 2020 ). Furthermore, word cards can only be effective when learners have been trained and understand how to use them ( Reynolds et al., 2020 ). Therefore, these variables should be taken into consideration to understand whether word cards are effective for vocabulary learning.

It is worthwhile to conduct a synthesis of the word card literature to allow for generalization of the results reported in primary studies. A synthesis can help us to systematically review the word card literature, thereby providing a clearer picture of the overall effectiveness of word cards. Such a result can be useful for teachers, learners, and researchers, as a research synthesis can provide clear implications for research and teaching. Compared to meta-analysis, which “requires strict inclusion criteria for calculating effect sizes (ESs),” a research synthesis allows for “more varieties of relevant studies to be included” ( Yang et al., 2021 , p. 472). Therefore, this study gives a systematic and comprehensive review on the past research regarding vocabulary learning from word cards using a research synthesis methodology.

The current synthesis of primary empirical studies brings significance to the field of vocabulary learning from word cards for two main reasons. Firstly, there is growing interest in the effects that word cards have on vocabulary learning, evident through the large number of studies published on this topic. With this large body of research, it is not surprising that some existing meta-analyses and syntheses also touch on this topic. For example, Webb et al. (2020) conducted a meta-analysis to examine the effectiveness of many vocabulary learning activities including the use of word cards. As a meta-analysis requires some strict inclusion criteria, many relevant word card studies had to be eliminated. Similarly, several researchers have synthesized the word card literature. Unfortunately, their focus was on synthesizing the literature on one specific type of word cards rather than all types of word cards ( Nakata, 2011 ; Lin and Lin, 2019 ; Ji and Aziz, 2021 ). Therefore, the previous meta-analyses and syntheses have not given an exclusive picture of how word cards lead to vocabulary learning. To fill this gap, this study adopts an inclusive synthesis approach to examine how the learners' use of word cards can lead to vocabulary learning.

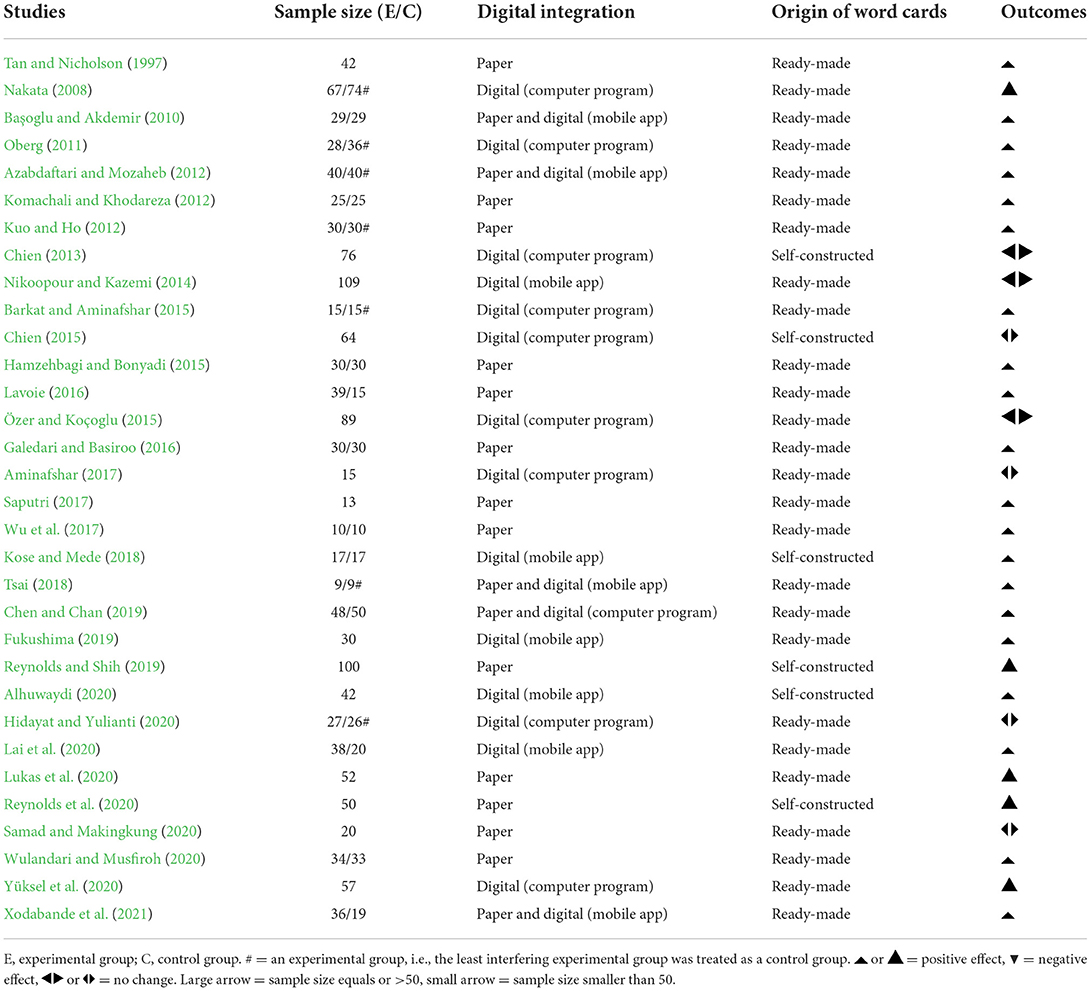

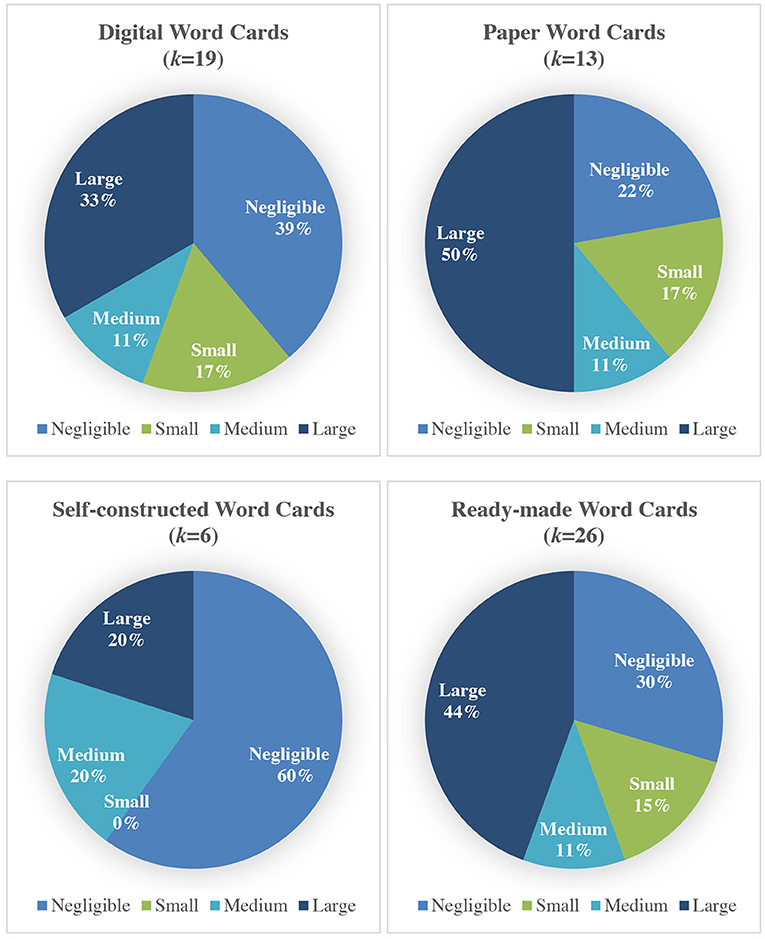

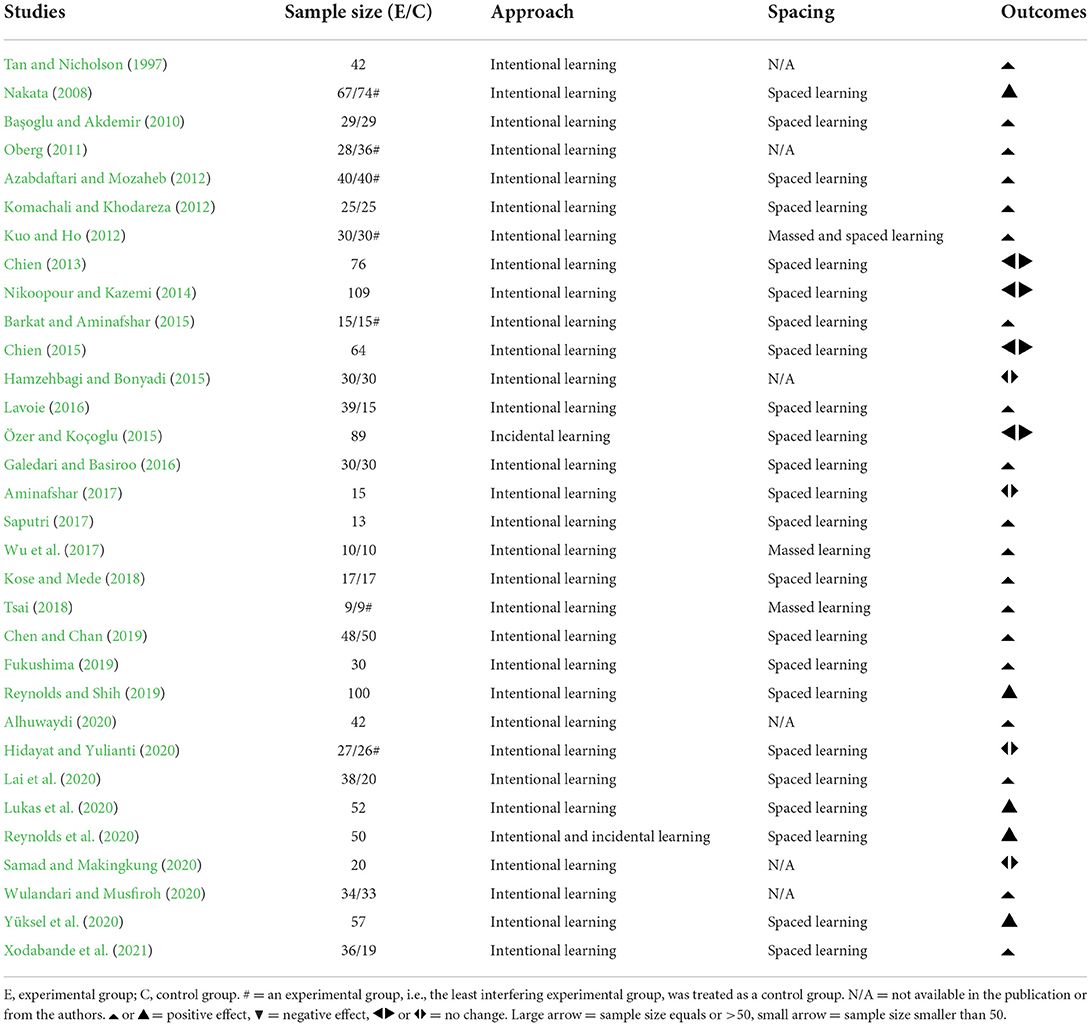

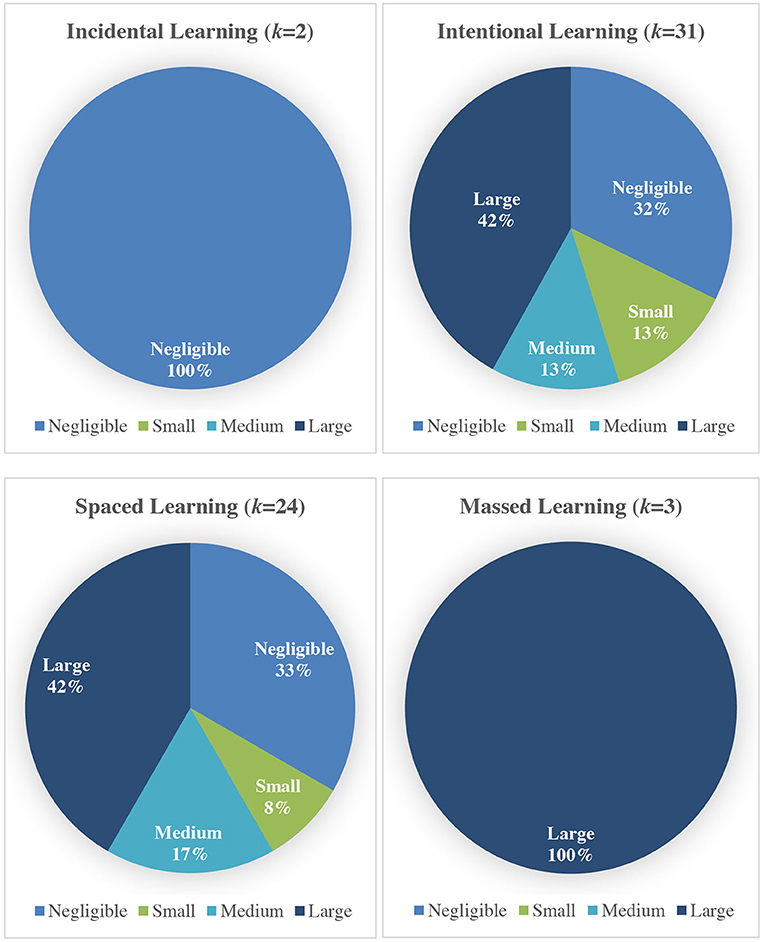

Secondly, there are several potential variables that may affect vocabulary learning from word card use. For example, the effect of the use of digital word cards has been compared to paper word cards (e.g., Azabdaftari and Mozaheb, 2012 ; Chen and Chan, 2019 ). Some studies asked learners to self-construct word cards (e.g., Reynolds et al., 2020 ), while other studies provided word cards to learners (e.g., Oberg, 2011 ). However, it appears in the previous literature that researchers have not considered whether this could influence the effectiveness of word card use. The use of word cards is most often assumed to be an intentional vocabulary learning strategy. However, some researchers have reported to use word cards as an incidental learning strategy as well (e.g., Reynolds et al., 2020 ). Researchers have not considered whether the use of word cards is suitable for incidental learning. The literature usually suggests that learners use word cards in a spaced learning condition. However, some researchers have suggested learners to use massed learning as a large number of repeated encounters with the words will occur ( Uchihara et al., 2019 ). Word cards were also reported to have been used for different amounts of time in previous studies (e.g., Webb et al., 2020 ). The amount of time spent learning from word cards might influence vocabulary learning. Moreover, most of the previous research involved learners at different levels of proficiency (e.g., Tan and Nicholson, 1997 ; Nakata, 2008 ). Different levels of language proficiency might result in varied amounts of vocabulary learning from word card use. In this regard, this study extends the discussion of learning L2 vocabulary through the use of word cards and includes potential variables that may affect the reported effects in the published word card literature.

Practically, the findings of this synthesis have the potential to benefit two stakeholders. Firstly, this study provides some suggestions for researchers who have been investigating vocabulary learning from word card use. The results can provide suggestions for a future research trajectory. Secondly, this study has the potential to provide teachers with advice on how they can incorporate the use of word cards into their classroom teaching and skill training for learners.

Literature review

In this section, we review relevant vocabulary, word card, and theory literature before summarizing existing findings about the variables of interest to the present synthesis. Doing this helps to situate the research questions that follow. The results of this research synthesis builds on the literature that is covered in this section.

Previous research syntheses on vocabulary learning from word cards

Previous meta-analysists and synthesists have conducted research related to English vocabulary learning activities and examined this field from different perspectives. For example, Webb et al. (2020) conducted a meta-analysis which focused on studies investigating “four types of intentional vocabulary learning activities, including flashcards, word lists, writing and fill-in-the-blanks” ( Webb et al., 2020 , p. 1). In their meta-analysis of 22 studies, Webb et al. (2020) found that “both flashcards and word lists led to relatively large gains in vocabulary knowledge while writing and fill-in-the-blanks lead to relatively small gains” ( Webb et al., 2020 , p. 19). However, their meta-analysis only included studies with treatments that lasted up to 1 day, i.e., studies with treatments that lasted longer than 1 day were excluded ( Webb et al., 2020 ). Uchihara et al. (2019) conducted a meta-analysis which focused on the effects of repetition on incidental vocabulary learning. In their meta-analysis of 26 studies, Uchihara et al. (2019 , p. 559) found that “there was a medium effect of repetition on incidental vocabulary learning.” However, their meta-analysis only included studies that adopted within participants design, i.e., studies that adopted between participants design were excluded. Various research designs deserve investigation, as there are an increasing number of empirical studies that have included separate groups with different interventions ( Kose and Mede, 2018 ; Reynolds and Shih, 2019 ; Wulandari and Musfiroh, 2020 ). Both Webb et al.'s (2020) and Uchihara et al.'s (2019) meta-analyses focused on the form and meaning aspects of word knowledge. Other aspects of word knowledge should also be given attention by meta-analysists and synthesists. Other aspects of word knowledge require more rigid attention in vocabulary learning from word cards research ( Uchihara et al., 2019 ), as vocabulary learning involves more than “associating the new words with their meaning” ( Nakata, 2011 , p. 20).

Nakata (2011) conducted a systematic review on digital word card programs for vocabulary learning. In this systematic review of 9 digital word card programs, Nakata (2011 , p. 17) found that most digital word card programs “have been developed in a way that maximize vocabulary learning.” Lin and Lin (2019) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis on vocabulary learning from digital word card use. In their systematic review and meta-analysis of 33 studies, Lin and Lin (2019) found that there was a positive and large effect of engagement in activities using digital word cards on vocabulary learning. Later, Ji and Aziz (2021) also conducted a systematic review of vocabulary learning from digital word card use. In their systematic review of 18 studies, Ji and Aziz (2021) also found that the use of digital word cards enhanced learners' vocabulary knowledge. These previous syntheses and meta-analyses gave insights on the effects of digital word card use but did not report on paper word card use or compare digital word cards to paper word cards. It is necessary to synthesize the studies that used digital word cards and paper word cards as it is important to see which type of word cards can result in better vocabulary learning outcomes.

Although previous syntheses have been investigating English language learning activities, few comprehensive syntheses have been conducted that focus on the use of word cards for vocabulary learning. Studies that utilized different research designs and assessed different aspects of word knowledge should be included for analysis, as the existing word card research was implemented in various research designs and assessed various aspects of word knowledge. In addition, various variables that might affect the vocabulary learning from word cards should be extracted from the studies for analysis.

It is evident that there is a growing interest in the effects that word cards have on vocabulary learning. This is shown from the number of different syntheses and meta-analyses that have been conducted on this topic ( Nakata, 2011 ; Elgort, 2017 ; Lin and Lin, 2019 ; Kim and Webb, 2022 ). There is also a growing body of studies on word card use ( Chen and Chan, 2019 ; Reynolds and Shih, 2019 ; Reynolds et al., 2020 ). However, the syntheses and the meta-analyses have not been very comprehensive in terms of the aspects of word knowledge assessed and the types of word cards used. The current synthesis is an attempt to give a systematic and comprehensive review on the past vocabulary learning research with a focus on word card use, hoping to provide some teaching implications and suggestions for future research.

Theoretical perspectives of vocabulary learning from word cards

There are several theoretical perspectives that have been used to frame previous studies. However, the majority of studies have used the Involvement Load Hypothesis ( Laufer and Hulstijn, 2001 ), the Pimsleur's Memory Schedule ( Pimsleur, 1967 ), or the Dual-Coding Theory ( Paivio, 1979 ). The word card studies included in the current synthesis relied on these theories for their research designs and interpretations of their results.

Involvement load hypothesis

The use of word cards is regarded as a task that has high involvement. The Involvement Load Hypothesis (ILH) is a “task-induced involvement” theory that consists of “three motivational and cognitive dimensions,” i.e., need, search, and evaluation ( Laufer and Hulstijn, 2001 , p. 2). Need is the “motivational, non-cognitive dimension of involvement” and refers to “whether unknown words are needed to complete a task” ( Laufer and Hulstijn, 2001 , p. 14; Yanagisawa and Webb, 2021 , p. 489). Need is absent when an unknown word is not required (need is 0) ( Yanagisawa and Webb, 2021 ). Need is moderate when it is “imposed by an external agent” (e.g., the learners are required to create word cards for teacher selected words) (need is 1), and it is strong when it is “imposed by the learners themselves” (e.g., the learners wish to create word cards for the incidentally encountered unknown words) (need is 2) ( Laufer and Hulstijn, 2001 , p. 14; Reynolds et al., 2020 ; Yanagisawa and Webb, 2021 , p. 489). Search and evaluation are the “two cognitive dimensions of involvement” ( Laufer and Hulstijn, 2001 , p. 14). Search refers to the attempt to find an unknown L2 word's form or its meaning ( Laufer and Hulstijn, 2001 ). Search is absent when the L2 word's form and its meaning are provided in a task (e.g., a reading comprehension task where new words are glossed) (search is 0) ( Laufer and Hulstijn, 2001 ; Yanagisawa and Webb, 2021 ). Search is moderate when the learners need to find an unknown L2 word's form or its meaning using external resources (e.g., dictionaries or teachers) (search is 1), and it is strong when the learners need to engage in both receptive learning and productive learning (e.g., looking at the L2 word forms and trying to recall the L1 translations, and looking at the L1 translations and trying to recall the L2 word forms on word cards) (search is 2) ( Reynolds et al., 2020 ; Yanagisawa and Webb, 2021 ). Evaluation involves “the comparison of a given word with other words” ( Laufer and Hulstijn, 2001 , p. 14). Evaluation is absent when the learners do not need to decide which word to use (evaluation is 0) ( Yanagisawa and Webb, 2021 ). Evaluation is moderate when it entails recognizing differences between words with a context provided (e.g., a fill-in-the-blanks task with given words) (evaluation is 1), and it is strong when a word must be used in an authentic context (evaluation is 2) (e.g., a composition writing task using target words) ( Laufer and Hulstijn, 2001 ; Yanagisawa and Webb, 2021 ). The strength of the involvement load can occur in any combination. ILH predicts that “higher involvement in a word induced by the task will result in better retention” ( Laufer and Hulstijn, 2001 , p. 20).

Some researchers used the ILH as a framework for designing their studies. For studies that used word cards, the involvement load was calculated as 6 out of a possible 6. For example, in Reynolds et al.'s (2020 , p. 5) study, learners were required to “construct word cards for unknown words encountered while reading a class textbook.” In Reynolds et al.'s (2020 , pp. 5–6) study, need was 2 (as the learners initiated the need to understand “the unknown words incidentally encountered during reading class texts”), search was 2 (as word cards were used for both receptive learning, i.e., the learners recalled the L1 translations by looking at the L2 word forms, and productive learning, i.e., the learners recalled the L2 word forms by looking at the L1 translations), and evaluation was 2 (as the learners compared “multiple meanings of the words” and used the chosen word to write a sentence on the word card). However, the ILH can only suggest the predictability of a task being useful or not for vocabulary learning. To address the issue of how memory works in the learning of vocabulary from word cards, the Pimsleur's Memory Schedule ( Pimsleur, 1967 ) is more suitable.

Pimsleur's memory schedule

Previous researchers have suggested that the traditional way of memorizing words lacks scheduled repetition, which would lead to forgetting ( Mondria and Mondria-De Vries, 1994 ). Repetition is “essential for vocabulary learning” in a foreign language ( Nation, 2013a , p. 451). Pimsleur (1967) recommended “a memory schedule” which can be regarded as a guide “for determining the length of time that should occur between repetitions” ( Kose and Mede, 2018 , p. 5). Teachers can follow this schedule to space the recall of words previously learned by students. In this schedule, the rationale for determining the amount of time before recalling previously learned words is that most of the forgetting occurs after the initial learning of a word ( Kose and Mede, 2018 ). This forgetting will slow down as time passes by if the words are periodically encountered ( Kose and Mede, 2018 ). Pimsleur (1967) suggested how often new words should be repeated in order to keep them in a person's memory. It should be “5 s, 25 s (5 2 = 25 s), 2 min (5 3 = 125 s), 10 min (5 4 = 625 s), and so on” ( Nation, 2013a , p. 454). If learners are provided with opportunities for repetition of new words at the right time, their memories will be refreshed, and the retrieval of the words can improve retention.

Some researchers used the Pimsleur's Memory Schedule (PMS) ( Pimsleur, 1967 ) as a framework for designing their studies. For example, Kose and Mede (2018 ) investigated the effects of vocabulary learning using digital word cards with a spaced repetition system following the PMS. By enabling learners to repeatedly be exposed to the target words at the right time, the learners in their study demonstrated a high level of vocabulary acquisition. This is because after the initial learning of a target word, the forgetting is very fast, but the forgetting on the second repetition will be slower ( Nation, 2013a ). Knowledge of vocabulary decreases less rapidly after each repetition of target words if the spacing has been increased ( Mondria and Mondria-De Vries, 1994 ). However, most of the included studies used increased spacing rather than strictly following the PMS. However, if studies do not strictly use words cards only with printed text and instead opt for word cards containing pictorial elements, then the Dual-Coding Theory ( Paivio, 1979 ) should be considered to understand how this added multimedia element affects learning.

Dual-coding theory

It is possible for the use of word cards to “combine visual and verbal information” to optimize “memorization of words” ( Lavoie, 2016 , p. 22). The Dual-Coding Theory (DCT) ( Paivio, 1979 ) proposed that cognition occurs in two distinct codes, i.e., a verbal code for language, and a non-verbal code for mental imagery ( Sadoski, 2006 ). When information is processed through two channels (verbal and non-verbal) instead of one, learners can “benefit from an additional or compensatory scaffold that supports L2 vocabulary learning” ( Wong and Samudra, 2019 , p. 1187). Visual representations of word meanings, such as pictures or multimedia, play an important role in vocabulary learning. In addition, written word forms must also be processed visually and learned as visible units ( Sadoski, 2006 ). Therefore, dual coding of word cards might enhance memory recall of vocabulary.

Previous researchers have used the DCT as a framework for designing their studies. For example, in Lavoie's (2016 ) study, the experimental group that used word cards was compared to a control group. The word cards were presented with words and pictures to ensure the verbal and non-verbal information was processed at the same time. The results showed learners progressing in the learning of new words, demonstrating the additive effects of the two sources of input on vocabulary learning ( Lavoie, 2016 ).

Aspects of word knowledge

Vocabulary learning is not all or nothing. There are different aspects of word knowledge. At the most general level, vocabulary knowledge can be divided into three main categories, i.e., “form, meaning, and use” ( Nation, 2013a , p. 48). Form refers to the “spoken form, written form and word parts”; meaning refers to “the connection between form and meaning, concepts, references and associations of a word”; and use refers to the “grammatical functions, collocations and constraints on use of a word” ( Nation, 2013a , p. 539). Each of these aspects of word knowledge can be assessed productively or receptively. Receptive and productive vocabulary knowledge refers to the “learning direction” of vocabulary ( Nation, 2013a , pp. 51–52). Productive knowledge of a word is what a learner “needs to know in order to use the word while speaking or writing,” while receptive knowledge is what a learner “needs to know to understand a word while reading or listening” ( Crow, 1986 , p. 242).

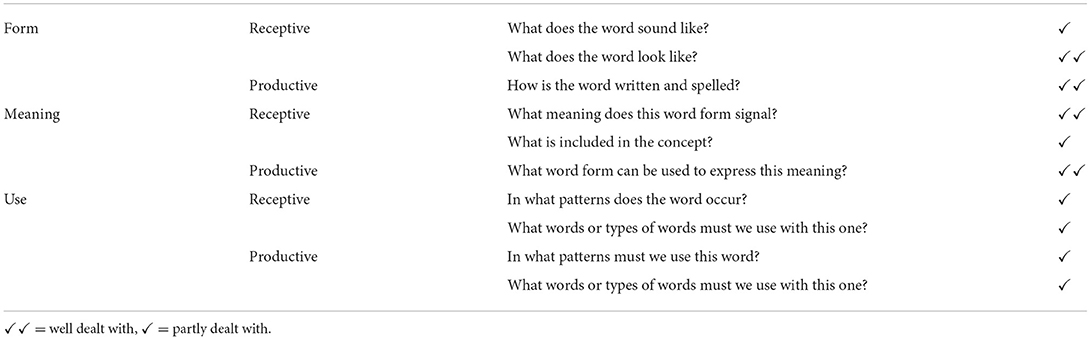

Table 1 ( Nation, 2013a ) lists these aspects of word knowledge, indicating which ones are well dealt with by learning form word cards, and which ones are partly dealt with by this strategy. Ideal learning occurs when vocabulary has been acquired both receptively and productively. Word cards “can be used for both receptive and productive learning” ( Nation, 2013a , p. 441). For example, if the learners are using bilingual word cards with the “L1 on one side and the L2 on the other,” “looking at the L1 and trying to recall the L2 form” involves productive knowledge of form ( Nation, 2013a , p. 446; Reynolds et al., 2020 , p. 5). If the learners are “looking at the L2 and trying to recall the L1 meaning with the word cards,” it involves receptive knowledge of meaning ( Reynolds et al., 2020 , p. 5).

Table 1 . Aspects of word knowledge dealt with by learning from word cards ( Nation, 2013a , p. 442).

Variables that affect learning from word cards

Several variables have the potential of moderating the effectiveness of learning vocabulary from using word cards. These include the type of word cards used (i.e., paper or digital, ready-made or self-constructed), word cards used in different learning conditions (i.e., incidental or intentional, spaced or massed), period of time they are used, or if they are used by learners with different language proficiencies.

Paper and digital word cards

Paper word cards are defined as word cards made from paper-based materials ( Nation, 2013a ). The emergence of digital word cards allows learners to learn vocabulary on computers ( Nakata, 2008 ) or mobile devices ( Lai et al., 2020 ). The use of digital word cards can arouse learners' interest in vocabulary learning ( Lin and Lin, 2019 ) and potentially lead to learning gains ( Başoglu and Akdemir, 2010 ; Azabdaftari and Mozaheb, 2012 ; Tsai, 2018 ; Chen and Chan, 2019 ; Xodabande et al., 2021 ).

Ready-made and self-constructed word cards

Ready-made word cards, which are prepared by teachers or bought in stores, are common in the language learning classroom. For example, McDonald and Reynolds (2021) presented ready-made cards based on words taken from storybooks for learners. In addition to using ready-made word cards, learners can also acquire vocabulary by self-constructing their own word cards. For example, Reynolds et al. (2020 ) required learners to construct 10 word cards for each of the 10 readings in a textbook. Previous researchers have indicated that learners might have a strong affective bond with self-constructed word cards ( Mondria and Mondria-De Vries, 1994 ). It is meaningful to know whether a learner should use self-constructed word cards or ready-made word cards. As learners may select the words by themselves for self-constructed word cards, this selection might affect their vocabulary learning.

Intentional and incidental learning conditions

The two broad approaches to vocabulary learning are intentional and incidental. Intentional vocabulary learning can be defined by whether learners know that “they will be tested on their vocabulary learning” ( Webb et al., 2020 , p. 2). If learners know of an “upcoming vocabulary test,” they may “pay special attention to vocabulary and engage in intentional learning” ( Uchihara et al., 2019 , p. 561). Incidental vocabulary learning is defined as “the learning that emerges through a meaning-focused comprehension task in which learners are not told of an upcoming vocabulary test” ( Uchihara et al., 2019 , p. 561). Thus, learners' awareness of a future assessment differentiates between incidental learning, where learners are “unaware of a subsequent vocabulary test,” and intentional learning, where “they know they will be tested” ( Webb et al., 2020 , p. 2).

Spaced and massed learning conditions

A massed learning condition refers to a learning condition in which words are repeated “during a single and continuous period of time,” while a spaced learning condition refers to a learning condition in which words are repeated “across a period of time at ever-increasing intervals” ( Kose and Mede, 2018 , p. 4). Spacing has often been operationalized “within a strictly controlled laboratory setting” in which learners study individual L2 words at different time intervals ( Uchihara et al., 2019 , p. 574). In this synthesis, the massed learning condition was operationalized as use of word cards within a single day, while the spaced learning condition was operationalized as use of word cards that lasted for more than 1 day ( Uchihara et al., 2019 ). Previous researchers have examined the effect of spacing on vocabulary development. For example, Kuo and Ho (2012 , p. 36) found a larger but non-significant effect on vocabulary learning when word cards were used in spaced learning conditions compared to massed learning conditions, because the effects of spaced learning might be reduced by retrieval activities in both learning conditions.

Time spent learning from word cards

Previous researchers were also interested in the amount of time that learners spent on learning from word cards ( Webb et al., 2020 ). In Webb et al.'s (2020) meta-analysis of vocabulary learning activities, results showed that the number of minutes learners spent per word did not significantly influence vocabulary learning. In the present research synthesis, time spent learning from word cards was operationalized as the number of minutes the learners spent learning vocabulary using the cards.

Proficiency level of learners

The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) ( Council of Europe, 2001 ) is “the most influential language framework in the field of second language teaching and assessment” ( Fleckenstein et al., 2020 , p. 2). “It describes foreign language competencies in three broad stages which can be divided into six proficiency levels,” i.e., A1/A2 for basic users, B1/B2 for independent users, and C1/C2 for proficient users ( Fleckenstein et al., 2020 , p. 2). Previous researchers have indicated that more advanced learners usually acquire more vocabulary than less proficient learners, as greater L2 knowledge should help learners to understand and use language ( Webb et al., 2020 ).

Testing vocabulary knowledge

In the previous research investigating the effects of word card use on vocabulary learning, researchers have used standardized tests and researcher-constructed tests. These tests have been used to assess different aspects of vocabulary knowledge (i.e., receptive and productive knowledge of form, meaning, and use). In this section, the standardized tests and the researcher-constructed tests used in these previous studies are introduced.

Standardized tests

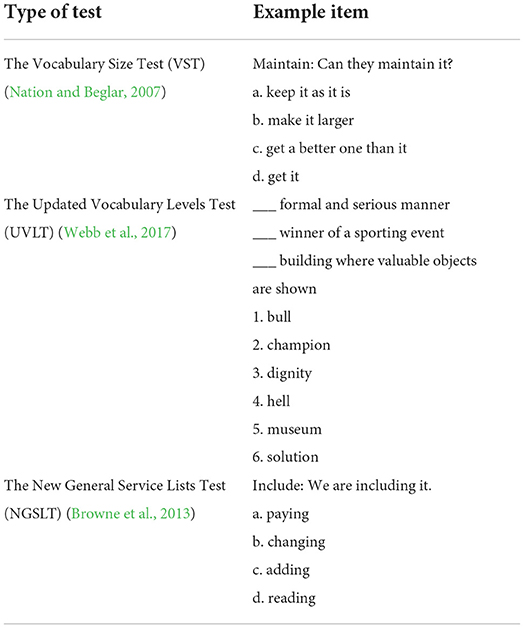

Three main standardized tests have been used in the published literature. These include the Vocabulary Size Test (VST) ( Nation and Beglar, 2007 ), the Updated Vocabulary Levels Test (UVLT) ( Webb et al., 2017 ), and the New General Service Lists Test (NGSLT) ( Browne et al., 2013 ). Table 2 provides example items from these standardized tests.

Table 2 . Standardized tests of vocabulary knowledge.

The VST ( Nation and Beglar, 2007 ) was designed to measure a learner's overall English receptive vocabulary knowledge. It is one of the most popular tests used to measure vocabulary size. The VST consists of 140 multiple-choice items. It consists of “10 sampled target words from each of the 1,000-level word family” lists up to the 14,000 level extracted from the “100,000,000 token British National Corpus” ( Reynolds et al., 2020 , p. 4). Answering all items correctly indicates that the test taker knows the most frequent “14,000 word families” of English ( Reynolds et al., 2020 , pp. 4–5).

The UVLT ( Webb et al., 2017 ) allows one to measure the mastery of vocabulary at different frequency levels. Specifically, the “first 1,000 most frequent words” of English to the “fifth 1,000 most frequent words” of English are assessed ( Webb et al., 2017 , p. 35). A test taker is presented with 30 questions per level. A test taker that scores “at least 26/30 (87%) has achieved mastery of that level” and might then focus on learning words from the next level ( Webb et al., 2017 , p. 56). However, the stricter criterion of 29/30 is recommended for masterly of the first three (1,000–3,000 word families) levels as those are commonly accepted as the basis for future vocabulary learning.

The NGSLT ( Browne et al., 2013 ) is “a diagnostic instrument” designed to assess “written receptive knowledge” of the words on the New General Service List (NGSL) ( Stoeckel et al., 2018 , p. 5; Xodabande et al., 2021 , p. 100). The NGSL is comprised of “2,800 high frequency words” and is designed to “provide maximal coverage of texts for learners of English” ( Stoeckel et al., 2018 , p. 5). The test is “a multiple-choice test that consists of 5 levels, each assessing knowledge of 20 randomly sampled words from a 560-word frequency based level of the NGSL” ( Stoeckel et al., 2018 , p. 5). The first level represents the most frequent words, the second level represents slightly less frequent words, and so forth. Answering correctly 16 or 17 items out of 20 indicates mastery of that level ( Browne et al., 2013 ).

Researcher-constructed tests

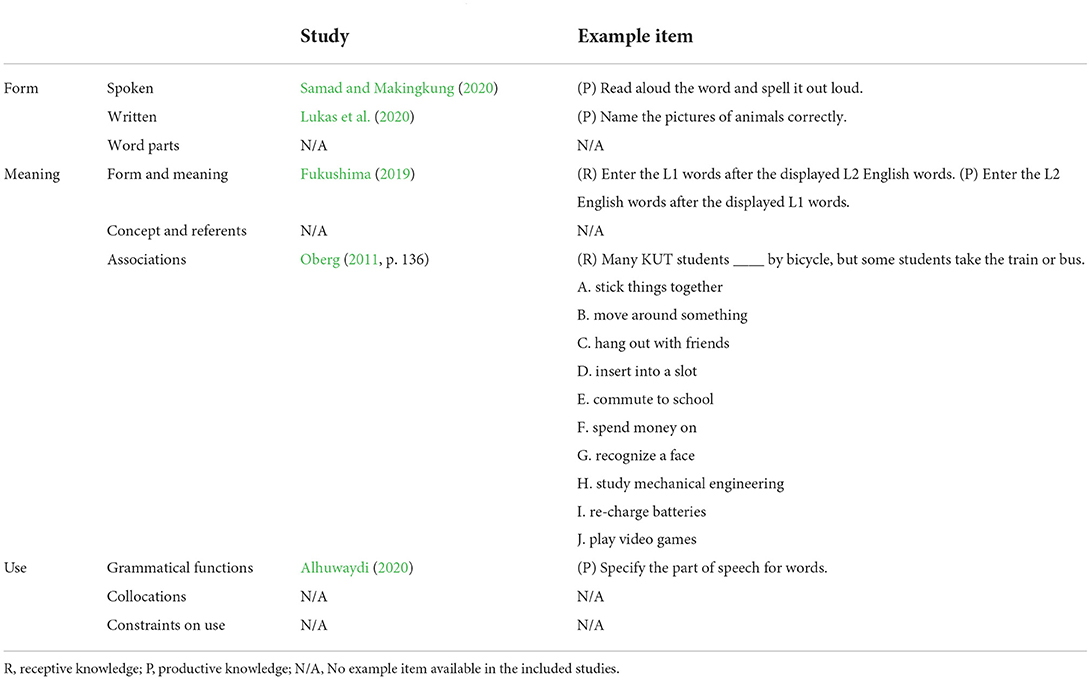

Looking at “how well a particular word is known” is called measuring “depth of knowledge,” while looking at “how many words are known” is called measuring “breath of knowledge” ( Nation, 2013a , p. 549). Table 3 ( Nation, 2013a , p. 442) lists various aspects of what is involved in “knowing a word” and provides a corresponding example test item that has been used in previous research to assess that particular knowledge aspect.

Table 3 . Researcher-constructed tests of vocabulary knowledge.

Previous word card research has assessed both receptive form knowledge and productive form knowledge. Receptive knowledge of form refers to whether a learner can recognize the “spoken form of a word, written form of a word, or the parts in a word” ( Nation, 2013a , p. 538). Productive form refers to whether a learner can “pronounce a word correctly, spell and write a word, or produce appropriate inflected and derived forms of a word” ( Nation, 2013a , p. 538). For example, Lukas et al. (2020 ) assessed the productive knowledge of form by having learners complete a word dictation task after they were provided a picture of an animal. Samad and Makingkung (2020 ) assessed the productive knowledge of form by having learners read aloud a word and spell it out loud.