What works to reduce police brutality

Psychologists’ research is pinpointing the factors that lead to overly aggressive, biased policing—and intervention that can prevent it

Vol. 51, No. 7 Print version: page 30

- Physical Abuse and Violence

- Forensics, Law, and Public Safety

- Racism, Bias, and Discrimination

When the Las Vegas Police Department applied a psychology-informed “hands off” policy for officers involved in foot chases, use of force dropped by 23%. In Seattle, officers trained in a “procedural justice” intervention designed in part by psychologists used force up to 40% less. These are just a few examples of the work the field is doing to address police brutality.

“There’s much more openness to the idea of concrete change among police departments,” says Joel Dvoskin, PhD, ABPP, a clinical and forensic psychologist and past president of APA’s Div. 18 (Psychologists in Public Service).

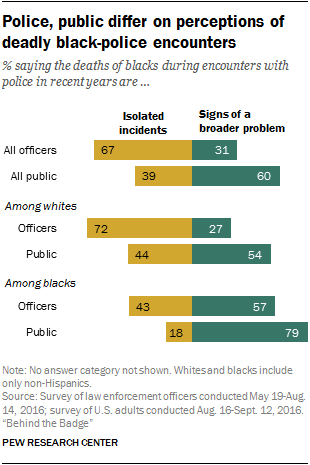

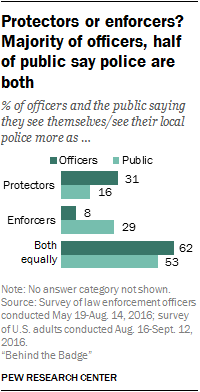

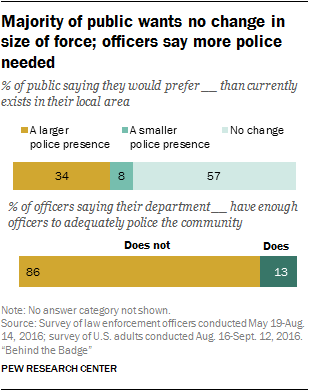

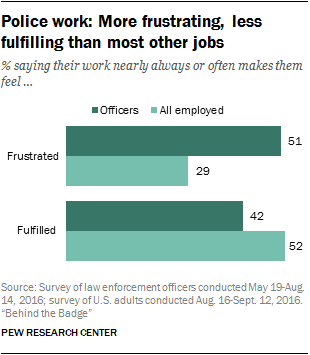

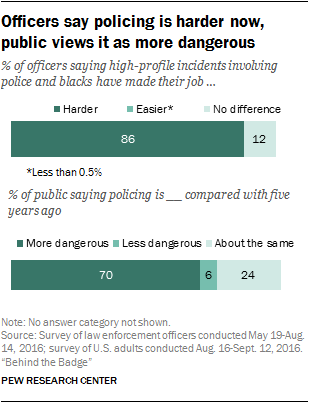

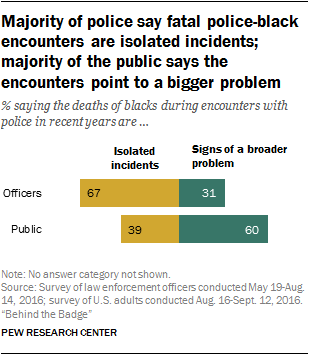

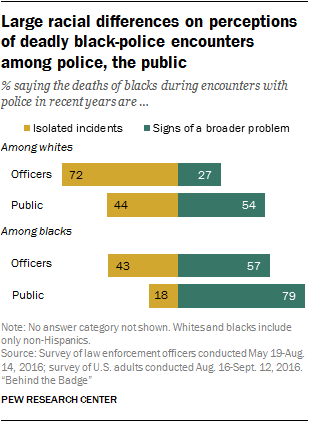

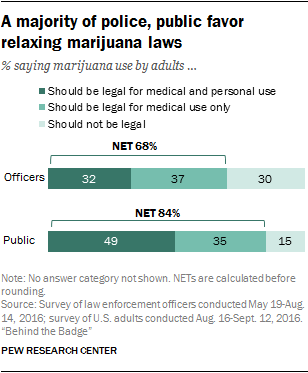

That shift is backed by support from the public. Since 2016, the share of Americans who say that police use the right amount of force, treat racial and ethnic groups equally and hold officers accountable for misconduct has declined substantially, according to the Pew Research Center ( Majority of Public Favors Giving Civilians the Power to Sue Officers for Misconduct , 2020).

Psychologists have already played a critical role in the reform process—from collecting data on biased police stops, searches and use of force to designing and delivering interventions that reduce the chances that police will rely on stereotypes, for instance by limiting the amount of discretion officers have during searches.

Now, psychologists are promoting those interventions to more police departments, conducting research to determine how well they work and continuing to collect and organize data on police behavior and department culture.

“Criminal justice—police, courts, prisons—has been called an evidence-free zone,” says Tom Tyler, PhD, a professor of psychology at Yale Law School and an expert in the psychology of justice. “People in positions of power tend to make policy decisions based on intuition and common sense—presumptions that we as psychologists recognize are often in error.”

“What’s really needed is an evidence-informed model of criminal justice,” he says. “And a lot of that evidence can come from psychologists.”

Psychological research in action

In 2015, President Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing reviewed scientific data on policing, recommending major policy changes at the federal level to improve oversight, training, officer wellness and more ( Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing , 2015).

Federal efforts have slowed in recent years, with most changes happening at the local level. But with around 18,000 police departments nationwide, that response has been fragmented and inconsistent ( National Sources of Law Enforcement Employment Data , Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2016).

Still, psychologists have forged ahead with efforts that are making a difference. One key contribution involves spurring policy changes and interventions based on psychological insights.

“One of the most influential approaches coming from psychology is training in procedurally just policing,” says Calvin Lai, PhD, an assistant professor of psychological and brain sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

That approach aims to increase the public’s trust in police by drawing on psychological research on justice and fairness. It involves teaching officers strategies such as explaining to citizens why they’ve been stopped and how it will benefit public safety ( Principles of Procedurally Just Policing , The Justice Collaboratory at Yale Law School, 2018).

“We know that the policing model of using force to compel compliance lowers the crime rate but does not build trust,” says Tyler, who has developed and studied models of procedurally just policing. “The crime rate has declined about 75% in the last 30 years, but public trust in the police hasn’t increased at all.”

His research has shown that what community members really want is for police to treat them with respect and to give them a voice—a chance to explain their situation before action is taken. People also want to know that police are sincere, care about the well-being of their community, and act in an unbiased and consistent way—for example, by explaining the rules they use and how they’re applying them.

A study in Seattle randomly assigned officers to receive training in procedurally just policing, leading to a reduction in use of force of between 15% and 40%, depending on the situation (Owens, E., et al., Criminology & Public Policy , Vol. 17 , No. 1, 2018).

“It seems to be doing what we’d hope in terms of promoting better relationships between police officers and community members,” says Lai.

The Center for Policing Equity (CPE), led by psychologist Phillip Atiba Goff, PhD, of Yale University, has also led a number of psychology-driven policy changes in police departments around the country. In an effort to cut down on high-adrenaline encounters—where police officers are more likely to rely on stereotypes—Goff urged the Las Vegas Police Department to bar officers involved in a foot pursuit from handling suspects when the chase ends. The policy led to a 23% drop in use of force at the department, an 11% reduction in officer injury and a simultaneous drop in racial disparities in use of force data. CPE has also pioneered efforts to recruit racially and ethnically diverse officer candidates and to make immigration enforcement more consistent.

Another key area that psychological interventions target is implicit bias, which has been documented across a range of domains and populations ( State of the Science: Implicit Bias Review , Kirwan Institute, 2017). One study led by Jennifer Eberhardt, PhD, professor of psychology at Stanford University, reviewed body camera footage and found that police officers in Oakland, California, treated Black people with less respect than whites (Voigt, R., et al., PNAS , Vol. 114, No. 25, 2017).

Eberhardt and others, including Lorie Fridell, PhD, a professor of criminology at the University of South Florida, have designed and begun to deliver training programs on implicit bias to law enforcement agencies around the country (“ Producing Bias-Free Policing: A Science-Based Approach ,” Springer Publishing, 2017).

Those programs, which typically mix instruction, discussion and role-playing, aim to help agencies reduce high-discretion policing and hold officers accountable for biased practices. But there’s no standardized curriculum—and experts say more research is needed to determine whether implicit bias training has a lasting impact and how such training can work alongside other agency reform efforts.

“There seem to be some forms of training that are effective, but the studies on these interventions are still pretty limited,” says Lai. “We just don’t know that much one way or the other.”

The power of peer intervention

Another intervention that has shown promise for reducing violence among police is known as Project ABLE , or Active Bystandership for Law Enforcement. Based on the work of psychologist Ervin Staub, PhD, an emeritus professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and past president of APA’s Div. 48 (Society for the Study of Peace, Conflict and Violence), the program promotes a culture of peer intervention. It teaches officers to prevent their peers from perpetrating unnecessary violence, which can save both lives and careers. Developed by the New Orleans Police Department in 2014 and originally named Ethical Policing Is Courageous (EPIC), Project ABLE is now being adopted by all police departments in New Hampshire and Washington state, as well as those in Baltimore, Boston, Philadelphia, several other cities and the FBI National Academy.

When an officer commits an act of unnecessary violence, his colleagues face a tough choice, Dvoskin says. Report the act and get a reputation as a “rat”—which may mean your next call for backup goes unanswered—or lie, which is a crime.

“What if, instead, you can prevent the bad thing from happening in the first place?” he says. “What if you manifested your loyalty to a fellow officer by helping him or her stay out of trouble?”

Staub says minor interventions can be highly effective. During recent protests of confederate monuments in New Orleans, an officer stopped a peer from attacking demonstrators by putting an arm around his shoulder. Trainees also apply strategies taught by the program to themselves. One officer in New Orleans reported using EPIC to avoid retaliating against a protester who had spit in her face.

That sort of behavior requires culture change. Police officers need to get comfortable both giving and receiving such interventions—and that culture must be modeled and supported by the highest levels of leadership within an organization, Dvoskin says.

To test his model of active bystandership, Staub studied examples of group violence, such as genocide, observing how hostility and violence evolve progressively. He has also conducted experimental research to understand how people respond to emergencies depending on the actions of those around them. In one study, participants’ helping behavior in response to a simulated emergency ranged from 25% to 100% of the time depending on a confederate’s response to the emergency. He also found that those who are asked to help once are more likely to volunteer later (Staub, E., “ The Roots of Goodness and Resistance to Evil ,” Oxford University Press, 2015).

Now, Project ABLE has support from Georgetown University and the international law firm Sheppard Mullin, which will help fund free training in active bystandership for any interested U.S. police department—and they’ve had hundreds of inquiries since June. Dvoskin, Staub and their team are now working to standardize lesson plans and policy guidelines.

“If this training is introduced in many police departments and done effectively, I believe that policing in America will be transformed,” Staub says.

Understanding and changing officer behavior

Psychologists are also helping agencies collect, report and understand data on their officers’ behavior—data that can point to further policy changes to reduce unnecessary violence and racial bias.

Simply changing the definition of a “police stop,” for instance, can help identify patterns of racial profiling that might otherwise be missed, says social psychologist Jack Glaser, PhD, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley’s Goldman School of Public Policy. Glaser has advised the California attorney general’s office on how to collect policing data, including revising the regulations on police stop reporting.

“Some police-civilian encounters are very casual and are not typically recognized as stops—but they are done with investigatory intent and can escalate to a detention,” he says.

For example, a pedestrian might voluntarily speak with a police officer who says, “Hi, can I ask you a question?”—but that conversation could lead to a search and even an arrest. Those stops typically aren’t reported, so racial bias in such practices could go unchecked.

Glaser has also partnered with CPE for a nationwide effort to aggregate data on police behavior with the National Justice Database , which draws from nearly 100 police departments representing more than a third of the U.S. population. He has worked to standardize and harmonize that data—which includes hundreds of thousands of entries on police stops, searches and use of force and can vary a lot from one agency to the next—so that researchers can start making comparisons and looking for larger trends.

Glaser says reporting officer behavioral data in different ways can paint a very different picture about whether racial disparities exist—so it’s important to get it right. For example, some departments consider officer presence or unholstering a weapon instances of police use of force, while others do not.

Goff, Glaser and their team delved into police use of force data to explore why some researchers, such as economist Roland Fryer, PhD, of Harvard University, have reported no racial differences in officer-involved shootings (Fryer, R.G., Journal of Political Economy , Vol. 127, No. 3, 2019). Their preliminary analysis shows that racial disparities may not exist in all officer-involved shootings, but that there’s a clear bias against African Americans when the victim is unarmed.

“Given that the protest movement is overwhelmingly about unarmed people getting killed by police, that seems to be the most important data point—but it seems to be getting lost,” Glaser says.

One major takeaway from the National Justice Database so far is that police are more likely to display racial bias when they conduct a “high-discretion search”—usually done on a hunch in ambiguous circumstances—versus a “low-discretion search,” a more routine activity, for instance when a person has already been detained for a crime. When the California Highway Patrol banned high-discretion searches, racial disparities began to level off ( Racial & Identity Profiling Advisory Board Annual Report , 2020).

“The obvious implication there is to try and minimize high-discretion searches,” Glaser says. “The tremendous amount of discretion given to police promotes decision-making under ambiguity and uncertainty, which psychologists know is ripe for stereotype influence.”

Screening officer candidates

Other psychologists have worked to adapt the police selection process to address the issue of implicit bias. Portland-based forensic psychologist David Corey, PhD, ABPP, has urged departments to add “cultural competence” as a criterion for screening law enforcement officers. “On the surface, the implicit bias literature is dismally depressing, because it tells us that everybody has automatic stereotypes that operate unconsciously and affect behavior,” says Corey, who also founded the American Board of Police and Public Safety Psychology .

Because of measurement issues, it’s not practical to screen candidates for policing jobs based on their implicit biases. But studies show that some personality dimensions can help officers temper those biases (Ben-Porath, Y.S., “ Interpreting the MMPI-2-RF ,” University of Minnesota Press, 2012). Specifically, people high in executive functioning, emotional regulation skills and metacognitive abilities are better able to prevent implicit biases from affecting their behavior. A capacity for theory of mind formation—the ability to anticipate how others will behave based on their actions or tone of voice—also helps officers learn to bypass their initial instincts.

“Those competencies render implicit bias more malleable,” says Corey. “So, my focus, and that of a growing number of colleagues around the country, is to evaluate applicants for those qualities.”

The Portland Police Bureau, as well as several other agencies in the Pacific Northwest, have added such measures to their selection battery.

Answering more questions

Looking ahead, psychologists are working to address gaps in the data in crucial areas such as use of force, says Shauna Laughna, PhD, ABPP, a Florida-based police and public safety psychologist and chair of APA Div. 18’s Police and Public Safety section. She adds that recruitment, training, discipline and retention of personnel can vary greatly across the 18,000 law enforcement agencies in the United States. That points to a need for more data, standardized measures—for instance, what constitutes excessive use of force—and a comprehensive national database on policing incidents.

“Attempting to generalize from data gathered at one agency to another may not always be prudent,” she says.

As reform efforts continue at the local and state levels, there’s one other essential thing the field can do, says Colby Mills, PhD, a clinical psychologist who works with the Fairfax County Police Department in Virginia: Provide more formal training opportunities for police psychologists, including during graduate school and in the form of continuing education. The limited police psychology coursework currently available within forensic psychology programs often does not include adequate training on the culture, ethics and special skills required to do such work, he says.

“It takes a lot of courage for a police officer to reach out to a mental health professional, because of the stigmas and the pressures they experience,” Mills says. “But once they do it, we owe it to them to provide a qualified professional who knows what they face and understands their culture.”

Critical incident response

In addition to their involvement with department-wide training efforts, psychologists are also increasingly providing ongoing mental health services, for instance after an officer-involved shooting occurs, says Colby Mills, PhD, a clinical psychologist who contracts with the Fairfax County Police Department in Virginia.

Along with peer support officers and the station’s police chaplain, Mills deploys immediately after a critical incident occurs and delivers Stress First Aid, a model developed for the military that can support officers in processing emotions ( Stress First Aid for Law Enforcement , National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, 2016).

“We want to strike a balance where we offer support without implying that an officer will automatically need help to recover,” Mills says.

The Fairfax County Police Department works with about a dozen psychologists who provide critical incident response, therapy, psychoeducation, consultations and pre-employment screenings.

“In general, police and public safety agencies are starting to embrace these sorts of psychological services more and more,” Mills says.

Further reading

A Meta-Analysis of Procedures to Change Implicit Measures Forscher, P.S., et al. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 2019

The Science of Justice: Race, Arrests and Police Use of Force Goff, P.A., et al. Center for Policing Equity, 2016

Preventing Violence and Promoting Active Bystandership and Peace: My Life in Research and Applications Staub, E., Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 2018

Recommended Reading

Apa’s recommendations for police reform.

- Promote community policing

- Ban chokeholds and strangleholds

- Invest in crisis intervention teams

- Increase the number of mental health professionals in law enforcement agencies

- Involve psychologists in multidisciplinary teams to implement police reforms

- Encourage partnerships between mental health organizations and local law enforcement

- Discourage police management policies and practices that can trigger implicit and explicit biases

- Strengthen data collection

- Bolster research

Read more about APA’s recommendations online .

Contact APA

You may also like.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Police brutality and racism in America

The Schwartzreport tracks emerging trends that will affect the world, particularly the United States. For EXPLORE it focuses on matters of health in the broadest sense of that term, including medical issues, changes in the biosphere, technology, and policy considerations, all of which will shape our culture and our lives.

After getting arrested several times for participating in civil rights demonstrations as I walked down Constitution Avenue, past what were then known as the Old Navy buildings, now long gone, on that warm Wednesday afternoon on the 28th of August 1963, I thought we had reached the turning point. I and thousands of others were moving quietly and peacefully towards the Lincoln Memorial where we were going to hear the Reverend Martin Luther King give what history now knows as the “I have a Dream" speech.

I was walking with a Black friend, a reporter for The Washington Star, an historic paper now long gone. I looked over Richard's shoulder and saw walking next to us two young partners of the then conservative Republican law firm, Covington & Burling. Richard saw where I was looking and turned to watch them as well. To him they were just two more White men; a large proportion of the crowd were White, and men. When I explained who they were he smiled, and I said, “I think we've won.” It was such a happy day; I remember it still.

And a little less than a year later, on 2 July 1964, almost unthinkably, a Southern politician, President Lyndon Johnson, signed into law the bipartisan Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited discrimination in public places, provided for the integration of public schools, and facilities, and made employment discrimination based on race illegal. It seemed Dr. King's dream was coming true.

Then a year after that when Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which outlawed discriminatory voting practices, such as literacy tests and poll taxes, I thought all was now well. It had taken a hundred years, since the end of the Civil War, but we were finally throttling the monster of racism.

And yet here I sit, looking day after day at the searing television images of the new civil rights demonstrations, watching videos of White policemen murdering Black men for no reason except they could, thinking they would get away with it, as they had so often in the past. The mass demonstrations with their clouds of tear gas and rubber bullets. The gross misuse of the American military against American citizens. The eight minutes and 46 seconds of video showing four policemen in Minneapolis murdering an unarmed handcuffed Black man, George Floyd, as he lay in the street handcuffed, that has caused, as I write this, 19 days of civil rights demonstrations involving millions all over the world.

It is important to remember also, I think, that this historic event, the murder and everything that has followed from that death is known to us only because of the bravery of one 17-year old girl, Darnell Frazier, who would not be intimidated and kept her phone camera on creating a video record of what was happening. As her hometown paper, the Star Tribune reported, Frazier wasn't looking to be a hero. She was “just a 17-year-old high school student, with a boyfriend and a job at the mall, who did the right thing. She's the Rosa Parks of her generation.” 1 I completely agree. I have written often about the power of a single individual at the right moment. 2 Could there be a clearer example?

What made this event historic, so catalyzing, so emotionally powerful that people all over the world in their millions took to the streets, even though it could mean their life because the Covid-19 pandemic which, in the U.S. alone, had infected over two million people and was still killing a thousand people a day? I think it was because it illustrated the conjunction of two major trends in America: the blatant racism that still infects the country, and the racially biased police brutality which has become outrageous.

George Floyd is one of a thousand police killings that will probably happen in 2020. There were that many last year. The statistics about American law enforcement are astounding when compared to those of other developed nations, like those that make up the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). According to Statistia in the U.S. there have been, “a total (of) 429 civilians ...shot, 88 of whom were Black, as of June 4, 2020. In 2018, there were 996 fatal police shootings, and in 2019 increased to 1004 (see Figure 1). Additionally, the rate of fatal police shootings among Black Americans was much higher than that for any other ethnicity, standing at 30 fatal shootings per million of the population as of June 2020.” 3

Credit: The Washington Post.

By way of contrast, in Norway, which I pick because it is a nation with high gun ownership, the police in 2019 armed themselves and displayed weapons 42 times, and fired two guns once each, and no one was killed. Few Americans even realize that “A police officer does not have to shoot to kill and, in several countries, a police officer does not even have to carry a gun. In Norway, Iceland, New Zealand, Britain, and Ireland, police officers generally do not carry firearms.” 4

Intermixed with racial brutality on the part of the law enforcement system in the U.S. is the gross misuse of the American military against the American people they are sworn to protect. And then there is the American gulag. It's prisons and jails dot our national landscape holding millions of incarcerated men and women a large majority of them Black and Brown.

Until this June I don't think most Americans really understood how violent and racist policing in America has become. If you are White like me, professional and relatively affluent, you never have any interactions with the police. They don't come to your door, and should it happen that you are stopped for a traffic ticket you don't feel threatened; it is no more than an annoyance that is going to cost you a few dollars for the fine. And even then, how often does that happen? I haven't been stopped since 1973, when a taillight on my car had gone out without my noticing. You see the police, they are there. But it is not an issue.

But if you are Black or Brown you live in another world.

Three weeks before George Floyd was murdered during a traffic stop by four police officers, an exhaustive study carried out by a research team at Stanford University led by Emma Pierson and Camelia Simoiu, was published in Nature Human Behavior Entitled, “A Large-scale Analysis of Racial Disparities in Police stops Across the United States”. It presented the truth of America, and it is horrifying.

“We assessed racial disparities in policing in the United States by compiling and analysing a dataset detailing nearly 100 million traffic stops conducted across the country. We found that black drivers were less likely to be stopped after sunset, when a ‘veil of darkness’ masks one's race, suggesting bias in stop decisions. Furthermore, by examining the rate at which stopped drivers were searched and the likelihood that searches turned up contraband, we found evidence that the bar for searching black and Hispanic drivers was lower than that for searching white drivers. Finally, we found that legalization of recreational marijuana reduced the number of searches of white, black and Hispanic drivers—but the bar for searching black and Hispanic drivers was still lower than that for white drivers post-legalization. Our results indicate that police stops and search decisions suffer from persistent racial bias and point to the value of policy interventions to mitigate these disparities.” 5

Some years ago I was on the board of a foundation to help children in medical distress. Also on the board was the then Deputy Chief of Police of the Los Angeles Police Department. We became friendly and one night went out to dinner together after a board meeting. This was not long after the 1992 riots that occurred when Rodney King, a Black man, was savagely beaten by police in a traffic stop. I asked the Deputy Chief, who had told me he had risen through the ranks and been a sworn officer for almost 30 years, how many police officers would participate in something like the King beating? I have never forgotten his answer. He said, “About 15% of police are heroes, the very best you could ever ask for. Another 15% are thugs and bullies who become police because they think they can act out without fear of punishment. The remaining 70% go with the flow. If they are with heroes, they behave heroically; if they are assigned to work with thugs, well bad things happen.” He explained that what he was trying to do was identify the thugs before they were hired. And to break through the “Blue Wall” if they were hired. He told me it was not easy, and one of the problems was the police union which protected its members at all cost.

How bad is it? I mean real numbers, not just the conjecture and political commentary that fills the airwaves. It turns out that it is very hard to get this information. Because of the power of the police unions and the racism of the U.S. Congress under the last four presidents, both Democrats and Republicans — Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barrack Obama, and Donald Trump — as police violence has grown worse each year, creating a real federal data base on police violence has proven almost impossible.

Congress passed H.R. 3355 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994. 6 It provided funds for local and state law enforcement entities and the State Attorney Generals to “acquire data about the use of excessive force by law enforcement officers” across the nation and to “publish an annual summary of the data acquired.” It didn't go well. In 1996, the Institute for Law and Justice and the National Institute of Justice on behalf of the DOJ, in a carefully worded report, described the failure to do what was mandated two years earlier. “Systematically collecting information on use of force from the Nation's more than 17,000 law enforcement agencies is difficult given the lack of standard definitions, the variety of incident recording practices, and the sensitivity of the issue.” 7

So in 2020, do we know any more? We do, although still far from enough. In 2019, a research team led by Frank Edwards of the School of Criminal Justice at Rutgers University, published a report, “Risk of being killed by police use-of-foce in the U.S. by age, race/ethnicity, and sex.” They reported:

“We use novel data on police-involved deaths to estimate how the risk of being killed by police use-of-force in the United States varies across social groups. We estimate the lifetime and age-specific risks of being killed by police by race and sex. We also provide estimates of the proportion of all deaths accounted for by police use-of-force. We find that African American men and women, American Indian / Alaska Native men and women, and Latino men face higher lifetime risk of being killed by police than do their white peers. We find that Latino women and Asian / Pacific Islander men and women face lower risk of being killed by police than do their white peers. Risk is highest for Black men, who (at current levels of risk) face about a 1 in 1000 chance of being killed by police over the life course. The average lifetime odds of being killed by police are about 1 in 2000 for men and about 1 in 33,000 for women. Risk peaks between the ages of 20 and 35 for all groups. For young men of color, police use-of-force is among the leading causes of death.” 8

Just to put that in a little finer focus, what they are saying is: “African American men were about 2 1 / 2 times more likely than White men to be killed by police. Men of color face a non-trivial lifetime risk of being killed by police” 9

The Washington Post looked into this issue and tuned the data even finer: “Although half of the people shot and killed by police are white, black Americans are shot at a disproportionate rate. They account for just 13 percent of the U.S. population, but more than a quarter of police shooting victims. The disparity is even more pronounced among unarmed victims, of whom more than a third are black.” 10

And if you are Black or Brown, while being murdered is the worst case scenario it is not the only misery that awaits any interaction with America's racist police. A study carried out by Megan T. Stevenson and Sandra Mayson that was published in 2018 in The Boston University Law Review described the reality of being a Black person on the streets of America. In doing their research Stevenson and Mayson discovered first that the hysteria about crime built up in America by conservative politicians and commentators, who are overwhelmingly White, is unfounded. “the number of misdemeanor arrests and cases filed have declined markedly in recent years. In fact, national arrest rates for almost every misdemeanor offense category have been declining for at least two decades, and the misdemeanor arrest rate was lower in 2014 than in 1995 in almost every state for which data is available.” 11

But they also found, “there is profound racial disparity in the misdemeanor arrest rate for most—but not all—offense types. This is sobering if not surprising. More unexpectedly, perhaps, the variation in racial disparity across offense types has remained remarkably constant over the past thirty-seven years; the offenses marked by the greatest racial disparity in arrest rates in 1980 are more or less the same as those marked by greatest racial disparity today.” 12

The truth that almost none of us who are White get is that 57 years after Martin Luther King's I Have a Dream speech, 56 years after the Civil Rights act of 1964, and 55 years after the Voting Rights Act of 1965, if you are Black or Brown, and particularly if you are a young Black man, for you America is like living in an occupied country where any interaction with the police is to be avoided. It can send you to prison for a trivial offense at the least, and may, and often does, result in your murder at the hands of those whose supposed but not actual job is to “serve and protect.”

Speaking as a White man, I am fed up with that, and I think that this November all of us who are White and who believe the function of the state should be to foster wellbeing at every level, for everyone, need to check off our ballots only for candidates who are willing to do that, and vote out of office all politicians not so committed. What do you think?

Scientist, futurist, and award-winning author and novelist Stephan A. Schwartz , is a Distinguished Consulting Faculty of Saybrook University, and a BIAL Fellow. He is an award winning author of both fiction and non-fiction, columnist for the journal EXPLORE, and editor of the daily web publication Schwartzreport.net in both of which he covers trends that are affecting the future. For over 40 years, as an experimentalist, he has been studying the nature of consciousness, particularly that aspect independent of space and time. Schwartz is part of the small group that founded modern Remote Viewing research, and is the principal researcher studying the use of Remote Viewing in archaeology. In addition to his own non-fiction works and novels, he is the author of more than 200 technical reports, papers, and academic book chapters. In addition to his experimental studies he has written numerous magazine articles for Smithsonian, OMNI, American History, American Heritage, The Washington Post, The New York Times, as well as other magazines and newspapers. He is the recipient of the Parapsychological Association Outstanding Contribution Award, OOOM Magazine (Germany) 100 Most Inspiring People in the World award, and the 2018 Albert Nelson Marquis Award for Outstanding Contributions.

Gabriel Gelpi Rodriguez

Michael Gerald Ray Kirvelay

Anthony Ashford

Brent Pickard

Charles Todero

Eric Carter

Arteair Porter

Noah Magallan

Jose Juan Marquez

Bryan Bernard Wallace

Zabina Gafoor

Manuel Sanabria

Terry Maurer

Claudia Abigail Garcia-Miranda

Micaiah Clinton

Michael St. Clair

James Robert Frazier Jr

Roderick McDaniel

Marcelo Pelaez

Jose De Jesus Montoya Villa

Khari Westly

Branch Wroth

Jesus Hernandez Murillo

Alejandro Campos Rios

Christian Redwine

Brandon Lawrence

Juan A. Ruiz

Javier Magana

Dominique Clayton

Kendrall Tate

Sean Marie Hake or Sean Ryan

Alex Richard Makalii Naone

Anthony Hodge

Shane Allen Jensen

Updated 06/10/2024

Mapping Police Violence

Law enforcement agencies across the country are failing to provide us with even basic information about the lives they take. So we collect the data ourselves. Scroll to explore.

See our research & resources

View the data

Read about the methodology

Hover over a graphic to see more

Copy link to dashboard

Police killed 1,158 Victim people in Location the U.S. in Years 2020 .

A live tracker by campaign zero.

Last updated 06/10/2024

Share to Facebook

Share to Twitter

Share to email

There were 18 days in Victim 2020 when police did not kill Victim people in Location the U.S. .

Killings by police in 2020.

Police killed 4 people on January 01, 2020

Police killed 6 people on January 02, 2020

Police killed 0 people on January 03, 2020

Police killed 2 people on January 04, 2020

Police killed 6 people on January 05, 2020

Police killed 4 people on January 06, 2020

Police killed 2 people on January 07, 2020

Police killed 3 people on January 08, 2020

Police killed 6 people on January 09, 2020

Police killed 1 people on January 10, 2020

Police killed 5 people on January 11, 2020

Police killed 1 people on January 12, 2020

Police killed 2 people on January 13, 2020

Police killed 1 people on January 14, 2020

Police killed 5 people on January 15, 2020

Police killed 3 people on January 16, 2020

Police killed 1 people on January 17, 2020

Police killed 0 people on January 18, 2020

Police killed 4 people on January 19, 2020

Police killed 4 people on January 20, 2020

Police killed 6 people on January 21, 2020

Police killed 3 people on January 22, 2020

Police killed 6 people on January 23, 2020

Police killed 3 people on January 24, 2020

Police killed 2 people on January 25, 2020

Police killed 0 people on January 26, 2020

Police killed 4 people on January 27, 2020

Police killed 5 people on January 28, 2020

Police killed 2 people on January 29, 2020

Police killed 4 people on January 30, 2020

Police killed 0 people on January 31, 2020

Police killed 3 people on February 01, 2020

Police killed 3 people on February 02, 2020

Police killed 3 people on February 03, 2020

Police killed 5 people on February 04, 2020

Police killed 1 people on February 05, 2020

Police killed 1 people on February 06, 2020

Police killed 3 people on February 07, 2020

Police killed 2 people on February 08, 2020

Police killed 5 people on February 09, 2020

Police killed 3 people on February 10, 2020

Police killed 0 people on February 11, 2020

Police killed 3 people on February 12, 2020

Police killed 5 people on February 13, 2020

Police killed 4 people on February 14, 2020

Police killed 0 people on February 15, 2020

Police killed 5 people on February 16, 2020

Police killed 2 people on February 17, 2020

Police killed 2 people on February 18, 2020

Police killed 1 people on February 19, 2020

Police killed 5 people on February 20, 2020

Police killed 3 people on February 21, 2020

Police killed 2 people on February 22, 2020

Police killed 1 people on February 23, 2020

Police killed 3 people on February 24, 2020

Police killed 8 people on February 25, 2020

Police killed 6 people on February 26, 2020

Police killed 4 people on February 27, 2020

Police killed 2 people on February 28, 2020

Police killed 6 people on February 29, 2020

Police killed 4 people on March 01, 2020

Police killed 2 people on March 02, 2020

Police killed 4 people on March 03, 2020

Police killed 2 people on March 04, 2020

Police killed 5 people on March 05, 2020

Police killed 4 people on March 06, 2020

Police killed 2 people on March 07, 2020

Police killed 6 people on March 08, 2020

Police killed 3 people on March 09, 2020

Police killed 2 people on March 10, 2020

Police killed 2 people on March 11, 2020

Police killed 2 people on March 12, 2020

Police killed 8 people on March 13, 2020

Police killed 5 people on March 14, 2020

Police killed 5 people on March 15, 2020

Police killed 6 people on March 16, 2020

Police killed 3 people on March 17, 2020

Police killed 3 people on March 18, 2020

Police killed 3 people on March 19, 2020

Police killed 4 people on March 20, 2020

Police killed 5 people on March 21, 2020

Police killed 1 people on March 22, 2020

Police killed 2 people on March 23, 2020

Police killed 4 people on March 24, 2020

Police killed 3 people on March 25, 2020

Police killed 2 people on March 26, 2020

Police killed 5 people on March 27, 2020

Police killed 2 people on March 28, 2020

Police killed 1 people on March 29, 2020

Police killed 6 people on March 30, 2020

Police killed 3 people on March 31, 2020

Police killed 4 people on April 01, 2020

Police killed 4 people on April 02, 2020

Police killed 2 people on April 03, 2020

Police killed 1 people on April 04, 2020

Police killed 5 people on April 05, 2020

Police killed 3 people on April 06, 2020

Police killed 6 people on April 07, 2020

Police killed 3 people on April 08, 2020

Police killed 4 people on April 09, 2020

Police killed 6 people on April 10, 2020

Police killed 3 people on April 11, 2020

Police killed 5 people on April 12, 2020

Police killed 2 people on April 13, 2020

Police killed 1 people on April 14, 2020

Police killed 7 people on April 15, 2020

Police killed 2 people on April 16, 2020

Police killed 2 people on April 17, 2020

Police killed 4 people on April 18, 2020

Police killed 5 people on April 19, 2020

Police killed 0 people on April 20, 2020

Police killed 4 people on April 21, 2020

Police killed 5 people on April 22, 2020

Police killed 3 people on April 23, 2020

Police killed 5 people on April 24, 2020

Police killed 2 people on April 25, 2020

Police killed 2 people on April 26, 2020

Police killed 3 people on April 27, 2020

Police killed 4 people on April 28, 2020

Police killed 7 people on April 29, 2020

Police killed 3 people on April 30, 2020

Police killed 6 people on May 01, 2020

Police killed 0 people on May 02, 2020

Police killed 9 people on May 03, 2020

Police killed 3 people on May 04, 2020

Police killed 6 people on May 05, 2020

Police killed 4 people on May 06, 2020

Police killed 4 people on May 07, 2020

Police killed 3 people on May 08, 2020

Police killed 6 people on May 09, 2020

Police killed 1 people on May 10, 2020

Police killed 1 people on May 11, 2020

Police killed 2 people on May 12, 2020

Police killed 3 people on May 13, 2020

Police killed 3 people on May 14, 2020

Police killed 5 people on May 15, 2020

Police killed 3 people on May 16, 2020

Police killed 4 people on May 17, 2020

Police killed 2 people on May 18, 2020

Police killed 4 people on May 19, 2020

Police killed 3 people on May 20, 2020

Police killed 5 people on May 21, 2020

Police killed 0 people on May 22, 2020

Police killed 4 people on May 23, 2020

Police killed 2 people on May 24, 2020

Police killed 7 people on May 25, 2020

Police killed 8 people on May 26, 2020

Police killed 7 people on May 27, 2020

Police killed 6 people on May 28, 2020

Police killed 7 people on May 29, 2020

Police killed 1 people on May 30, 2020

Police killed 2 people on May 31, 2020

Police killed 3 people on June 01, 2020

Police killed 3 people on June 02, 2020

Police killed 5 people on June 03, 2020

Police killed 0 people on June 04, 2020

Police killed 3 people on June 05, 2020

Police killed 4 people on June 06, 2020

Police killed 4 people on June 07, 2020

Police killed 1 people on June 08, 2020

Police killed 4 people on June 09, 2020

Police killed 4 people on June 10, 2020

Police killed 4 people on June 11, 2020

Police killed 2 people on June 12, 2020

Police killed 3 people on June 13, 2020

Police killed 0 people on June 14, 2020

Police killed 1 people on June 15, 2020

Police killed 2 people on June 16, 2020

Police killed 5 people on June 17, 2020

Police killed 4 people on June 18, 2020

Police killed 2 people on June 19, 2020

Police killed 1 people on June 20, 2020

Police killed 2 people on June 21, 2020

Police killed 5 people on June 22, 2020

Police killed 3 people on June 23, 2020

Police killed 2 people on June 24, 2020

Police killed 5 people on June 25, 2020

Police killed 1 people on June 26, 2020

Police killed 5 people on June 27, 2020

Police killed 1 people on June 28, 2020

Police killed 4 people on June 29, 2020

Police killed 2 people on June 30, 2020

Police killed 3 people on July 01, 2020

Police killed 3 people on July 02, 2020

Police killed 1 people on July 03, 2020

Police killed 4 people on July 04, 2020

Police killed 2 people on July 05, 2020

Police killed 5 people on July 06, 2020

Police killed 3 people on July 07, 2020

Police killed 4 people on July 08, 2020

Police killed 3 people on July 09, 2020

Police killed 4 people on July 10, 2020

Police killed 2 people on July 11, 2020

Police killed 3 people on July 12, 2020

Police killed 3 people on July 13, 2020

Police killed 4 people on July 14, 2020

Police killed 2 people on July 15, 2020

Police killed 4 people on July 16, 2020

Police killed 2 people on July 17, 2020

Police killed 1 people on July 18, 2020

Police killed 1 people on July 19, 2020

Police killed 2 people on July 20, 2020

Police killed 1 people on July 21, 2020

Police killed 3 people on July 22, 2020

Police killed 2 people on July 23, 2020

Police killed 4 people on July 24, 2020

Police killed 2 people on July 25, 2020

Police killed 1 people on July 26, 2020

Police killed 1 people on July 27, 2020

Police killed 3 people on July 28, 2020

Police killed 4 people on July 29, 2020

Police killed 4 people on July 30, 2020

Police killed 2 people on July 31, 2020

Police killed 2 people on August 01, 2020

Police killed 2 people on August 02, 2020

Police killed 2 people on August 03, 2020

Police killed 7 people on August 04, 2020

Police killed 1 people on August 05, 2020

Police killed 3 people on August 06, 2020

Police killed 7 people on August 07, 2020

Police killed 5 people on August 08, 2020

Police killed 3 people on August 09, 2020

Police killed 5 people on August 10, 2020

Police killed 3 people on August 11, 2020

Police killed 0 people on August 12, 2020

Police killed 1 people on August 13, 2020

Police killed 4 people on August 14, 2020

Police killed 6 people on August 15, 2020

Police killed 4 people on August 16, 2020

Police killed 5 people on August 17, 2020

Police killed 3 people on August 18, 2020

Police killed 3 people on August 19, 2020

Police killed 5 people on August 20, 2020

Police killed 2 people on August 21, 2020

Police killed 5 people on August 22, 2020

Police killed 1 people on August 23, 2020

Police killed 2 people on August 24, 2020

Police killed 4 people on August 25, 2020

Police killed 3 people on August 26, 2020

Police killed 1 people on August 27, 2020

Police killed 2 people on August 28, 2020

Police killed 3 people on August 29, 2020

Police killed 2 people on August 30, 2020

Police killed 5 people on August 31, 2020

Police killed 1 people on September 01, 2020

Police killed 1 people on September 02, 2020

Police killed 4 people on September 03, 2020

Police killed 2 people on September 04, 2020

Police killed 3 people on September 05, 2020

Police killed 3 people on September 06, 2020

Police killed 1 people on September 07, 2020

Police killed 1 people on September 08, 2020

Police killed 3 people on September 09, 2020

Police killed 5 people on September 10, 2020

Police killed 1 people on September 11, 2020

Police killed 2 people on September 12, 2020

Police killed 2 people on September 13, 2020

Police killed 0 people on September 14, 2020

Police killed 2 people on September 15, 2020

Police killed 1 people on September 16, 2020

Police killed 1 people on September 17, 2020

Police killed 6 people on September 18, 2020

Police killed 3 people on September 19, 2020

Police killed 1 people on September 20, 2020

Police killed 4 people on September 21, 2020

Police killed 3 people on September 22, 2020

Police killed 1 people on September 23, 2020

Police killed 5 people on September 24, 2020

Police killed 1 people on September 25, 2020

Police killed 0 people on September 26, 2020

Police killed 2 people on September 27, 2020

Police killed 2 people on September 28, 2020

Police killed 1 people on September 29, 2020

Police killed 2 people on September 30, 2020

Police killed 1 people on October 01, 2020

Police killed 5 people on October 02, 2020

Police killed 2 people on October 03, 2020

Police killed 4 people on October 04, 2020

Police killed 2 people on October 05, 2020

Police killed 5 people on October 06, 2020

Police killed 0 people on October 07, 2020

Police killed 5 people on October 08, 2020

Police killed 4 people on October 09, 2020

Police killed 2 people on October 10, 2020

Police killed 0 people on October 11, 2020

Police killed 4 people on October 12, 2020

Police killed 3 people on October 13, 2020

Police killed 6 people on October 14, 2020

Police killed 4 people on October 15, 2020

Police killed 6 people on October 16, 2020

Police killed 4 people on October 17, 2020

Police killed 4 people on October 18, 2020

Police killed 6 people on October 19, 2020

Police killed 7 people on October 20, 2020

Police killed 2 people on October 21, 2020

Police killed 6 people on October 22, 2020

Police killed 8 people on October 23, 2020

Police killed 4 people on October 24, 2020

Police killed 1 people on October 25, 2020

Police killed 3 people on October 26, 2020

Police killed 4 people on October 27, 2020

Police killed 3 people on October 28, 2020

Police killed 2 people on October 29, 2020

Police killed 3 people on October 30, 2020

Police killed 2 people on October 31, 2020

Police killed 3 people on November 01, 2020

Police killed 3 people on November 02, 2020

Police killed 5 people on November 03, 2020

Police killed 6 people on November 04, 2020

Police killed 4 people on November 05, 2020

Police killed 1 people on November 06, 2020

Police killed 3 people on November 07, 2020

Police killed 3 people on November 08, 2020

Police killed 3 people on November 09, 2020

Police killed 4 people on November 10, 2020

Police killed 3 people on November 11, 2020

Police killed 2 people on November 12, 2020

Police killed 6 people on November 13, 2020

Police killed 5 people on November 14, 2020

Police killed 2 people on November 15, 2020

Police killed 2 people on November 16, 2020

Police killed 5 people on November 17, 2020

Police killed 1 people on November 18, 2020

Police killed 5 people on November 19, 2020

Police killed 3 people on November 20, 2020

Police killed 2 people on November 21, 2020

Police killed 5 people on November 22, 2020

Police killed 2 people on November 23, 2020

Police killed 2 people on November 24, 2020

Police killed 1 people on November 25, 2020

Police killed 1 people on November 26, 2020

Police killed 4 people on November 27, 2020

Police killed 0 people on November 28, 2020

Police killed 3 people on November 29, 2020

Police killed 2 people on November 30, 2020

Police killed 3 people on December 01, 2020

Police killed 2 people on December 02, 2020

Police killed 4 people on December 03, 2020

Police killed 5 people on December 04, 2020

Police killed 5 people on December 05, 2020

Police killed 3 people on December 06, 2020

Police killed 1 people on December 07, 2020

Police killed 3 people on December 08, 2020

Police killed 3 people on December 09, 2020

Police killed 6 people on December 10, 2020

Police killed 3 people on December 11, 2020

Police killed 0 people on December 12, 2020

Police killed 4 people on December 13, 2020

Police killed 1 people on December 14, 2020

Police killed 5 people on December 15, 2020

Police killed 3 people on December 16, 2020

Police killed 4 people on December 17, 2020

Police killed 5 people on December 18, 2020

Police killed 1 people on December 19, 2020

Police killed 1 people on December 20, 2020

Police killed 2 people on December 21, 2020

Police killed 4 people on December 22, 2020

Police killed 2 people on December 23, 2020

Police killed 2 people on December 24, 2020

Police killed 4 people on December 25, 2020

Police killed 1 people on December 26, 2020

Police killed 2 people on December 27, 2020

Police killed 8 people on December 28, 2020

Police killed 5 people on December 29, 2020

Police killed 4 people on December 30, 2020

Police killed 3 people on December 31, 2020

Black people are 2.9x more likely to be killed by police than white people in Location the U.S. .

Police killings per 1 million people in the u.s., 2013–2024.

Race and ethnicity population data from the 2020 Decennial Census

Police killed 49 more Victim people in Location the U.S. in Year 2020 compared to the previous year.

Police killed victim people in 49 states and the district of columbia in year 2020 ..

Fewer police killings

More police killings

Sage Journals

The threshold for being perceived as dangerous, and thereby falling victim to lethal police force, appears to be higher for White civilians relative to their Black or Hispanic peers.

The threshold for being perceived as dangerous, and thereby falling victim to lethal police force, appears to be higher for White civilians relative to their Black or Hispanic peers. - Sage Journals

Protest against police brutality reduces officer-involved fatalities for African Americans and Latinos (but not for Whites)

Protest against police brutality reduces officer-involved fatalities for African Americans and Latinos (but not for Whites) - SSRN

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- NEWS FEATURE

- 04 September 2019

What the data say about police shootings

- Lynne Peeples 0

Lynne Peeples is a science journalist in Seattle, Washington.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Protesters march after a fatal shooting by police in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in 2016. Credit: William Widmer/New York Times/eyevine

On Tuesday 6 August, the police shot and killed a schoolteacher outside his home in Shaler Township, Pennsylvania. He had reportedly pointed a gun at the officers. In Grants Pass, Oregon, that same day, a 39-year-old man was shot and killed after an altercation with police in the state police office. And in Henderson, Nevada, that evening, an officer shot and injured a 15-year-old suspected of robbing a convenience store. The boy reportedly had an object in his hand that the police later confirmed was not a deadly weapon.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 573 , 24-26 (2019)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-02601-9

Edwards, F., Lee, H. & Esposito, M. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116 , 16793–16798 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Johnson, D. J. et al. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116 , 15877–15882 (2019).

Nix, J., Campbell, B. A., Byers, E. H. & Alpert, G. P. Criminol. Public Policy 16 , 309–340 (2017).

Article Google Scholar

Wheeler, A. P., Phillips, S. W., Worrall, J. L. & Bishopp, S. A. Justice Res. Policy 18 , 48–76 (2017).

Download references

Reprints and permissions

Related Articles

FBI asks scientists for trust in taking anti-Asian bias seriously

News 07 JUN 24

Who owns your voice? Scarlett Johansson OpenAI complaint raises questions

News Explainer 29 MAY 24

Why babies in South Korea are suing the government

News 20 MAY 24

I was prevented from attending my own conference: visa processes need urgent reform

Correspondence 18 JUN 24

The global refugee crisis is above all a human tragedy — but it affects wildlife, too

We can make the UK a science superpower — with a radical political manifesto

World View 18 JUN 24

‘It can feel like there’s no way out’ — political scientists face pushback on their work

News Feature 19 JUN 24

Boycotting academics in Israel is counterproductive

Endowed Chair in Macular Degeneration Research

Dallas, Texas (US)

The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (UT Southwestern Medical Center)

Postdoctoral Fellow

Postdoc positions on ERC projects – cellular stress responses, proteostasis and autophagy

Frankfurt am Main, Hessen (DE)

Goethe University (GU) Frankfurt am Main - Institute of Molecular Systems Medicine

ZJU 100 Young Professor

Promising young scholars who can independently establish and develop a research direction.

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Zhejiang University

Qiushi Chair Professor

Distinguished scholars with notable achievements and extensive international influence.

Research Postdoctoral Fellow - MD

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

June 4, 2020

A Civil Rights Expert Explains the Social Science of Police Racism

Columbia University attorney Alexis J. Hoag discusses the history of how we got to this point and the ways that researchers can help reduce bias against black Americans throughout the legal system

By Lydia Denworth

Protester holds sign during a demonstration in honor of George Floyd on June 2, 2020, in Marin City, Calif.

Justin Sullivan Getty Images

In a now infamous event captured on video, on May 25, 2020, George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man, was killed by a Minneapolis police officer outside of a corner store. Derek Chauvin kneeled on Floyd’s neck for nine minutes and 29 seconds while two other officers helped to hold him down and a third stood guard nearby. Nearly a year later, in April 2021, a jury convicted Chauvin of second-degree murder, third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter. He could face decades in prison (sentencing was expected on June 25). In a highly unusual development, other police officers, including the Minneapolis chief of police, testified against Chauvin.

The three other officers involved, Thomas Lane, J. Alexander Kueng and Tou Thao, were indicted on a range of state and federal charges, including violating Floyd’s constitutional rights, failing to intervene to stop Chauvin, and aiding and abetting second-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter. Their trial is scheduled for March 2022.

The 2014 shooting death of Black teenager Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., sparked a renewed emphasis on racism and police brutality in the U.S.’s political and cultural conversation. In the past few years many names have been added to the list of Black people killed by police. Despite some efforts to acknowledge and grapple with systemic racism in American institutions, anger and distrust between law enforcement and Black Americans have remained high. But Floyd’s death sparked a new level of outrage. Protests erupted in hundreds of cities around the U.S. in the summer of 2020. Most demonstrations were peaceful. But some turned violent, with police using force against protesters and a small percentage of people setting fire to police cars, looting stores, and defacing or damaging buildings. By July the demonstrations were thought to be the largest protest movement in American history, with some 15 million to 26 million people estimated to have taken part.

In addition to the criminal charges against the officers, Floyd’s death has prompted U.S. Justice Department investigations into the practices of the Minneapolis Police Department. And Democrats in Congress are hoping to pass criminal justice reform legislation named for Floyd. Both reflect the interests of the new administration since Joe Biden took office in January 2021.

In June 2020, at the height of the protests, Scientific American spoke with civil rights attorney Alexis J. Hoag. Hoag is the inaugural practitioner in residence at the Eric H. Holder, Jr., Initiative for Civil and Political Rights at Columbia University. She works with both undergraduates and law school students at Columbia to introduce them to civil rights fieldwork (which she describes as “real issues, real clients, real cases”). Hoag was previously a senior counsel at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund. Scientific American asked her to share her perspective on the history that has brought the U.S. to a breaking point—and her ideas for how to make substantive improvements in how law enforcement and courts treat Black people in the country.

Why are we seeing this level of protest now?

I think it’s a combination of things. COVID-19 [has had a] disproportionate impact on Black people because of long-standing structural inequalities. Black people are more likely to live in hypersegregated low-income areas that are underresourced. And Black people are more prone to the very preexisting conditions that make people vulnerable to COVID-19 because of structural inequality and lack of access to health care. We’ve all been cooped up for 10 to 11 weeks. Forty million people [in the U.S.] are unemployed. And there was something egregious about the video that circulated of George Floyd being executed for the suspicion of tendering a counterfeit $20 bill. And I want to stress “suspicion” because we still don’t know. That became a death sentence for him.

The violence that has been rendered against Black bodies has gone on for centuries. Now it’s out there for everyone to see. And the response, which is hopeful and heartening to me, is that people—not just Black Americans—in this country are really disturbed and appropriately so.

What are the important historical factors that have led up to this point?

I lean so heavily on the unique history of this country and the fact that we enslaved people, Black people. To hold people in bondage as property, you had to look at them as less than human. You see that continuing to happen today in [what] I refer to as the criminal legal system, not the justice system, because it is not just. We are not there yet. As an appellate attorney, I read a lot of transcripts of trials. And the level of dehumanization that prosecutors use to refer to Black criminal defendants is striking. It’s the verbiage used, that the defendant was “circling” and “hunting” the victim. What hunts and circles? Animals. When you can dehumanize an individual, of course, you can put the person away for a long time, you can sentence him or her to death. And of course, you can put your knee on somebody’s neck for nine minutes because you see them as less than human. It’s a combination of the dehumanization of Black people with the presumption of dangerousness and criminality.

Is racism getting worse? Or has the ubiquity of cell phones and video recordings simply made us more aware of it?

These issues are getting amplified; they’re getting recorded. I think back to the early 1990s and Rodney King’s videotaped beating. That really galvanized people around this issue—an issue that many Black Americans were intimately aware of already—and put it out there for the world to see. Then the response after those officers were acquitted was public demonstrations in 1992 in Los Angeles. I think people would not have been as engaged if we didn’t have that image. Now we walk around with [cameras] in our pockets.

How does the seeming increase in white nationalism fit in?

I don’t know that I would call it an increase. White nationalists, known earlier as white supremacists, first rallied [more than] 150 years ago to violently limit the freedom of newly emancipated Black Americans. Despite federal legislation extending the benefits of citizenship to Black people, white supremacists passed state laws codifying inequality and used violence and intimidation to curtail any Black exercise of freedom. What’s happening now [in June 2020] is that we have [a presidential] administration that welcomes and encourages white nationalist views and activities.

Have events in Ferguson and other cities, and the Black Lives Matter movement as a whole, had any effect on policing?

Ferguson was a massive wake-up call. There was a brief glimmer of hope. There was a mechanism in place: the Law Enforcement Misconduct [Statute]. It [is] a federal law the Department of Justice could rely on to investigate Ferguson, to investigate police misconduct in Baltimore [where Freddie Gray, a 25-year-old Black man, died while being transported in a police vehicle in what was ruled to be a homicide]. That law was grossly underutilized by Attorney General William Barr. Who the administration is and who the chief law-enforcement officer of this country is—the attorney general of the U.S.—makes a difference. We’ve seen a massive rollback in the responsiveness of the [Trump] administration [in taking] a hard look at injustice and at rampant police misconduct.

The other step back that the country has taken is to characterize officers involved in misconduct as “a few bad apples.” I think we all need to admit that it’s not a few bad apples; it’s a rotten apple tree. The history of policing in the South [was driven in part by] slave patrols that were monitoring the movement of Black bodies. And in the North, law enforcement was privately funded [and often involved protecting property and goods]. The police got started targeting poor people and Black people.

What would you like to see happen now?

I think there needs to be a really hard conversation nationally and within law enforcement. To use force, police officers have to reasonably believe that their lives are in danger. What is it about Black skin that makes law enforcement feel threatened for their lives? In addition, there are legal mechanisms that need to be examined. “Qualified immunity” as a defense to police misconduct was judicially created in 1982. It shields government officials from being sued for discretionary actions that are performed within their official capacities unless the action violates clearly established federal law. Somebody who is suing an officer for tasing someone while they’re handcuffed has to find a case from the U.S. Supreme Court or the highest court of appeals in their jurisdiction that says that exact act—being handcuffed and tased—is unconstitutional. This is a massive hurdle for a plaintiff.

What are social scientists and researchers doing to help?

Data are currency. We can create a national database of officer misconduct. You have officers such as Derek Chauvin, who had 18 complaints against him and [was] still allowed to operate within the [Minneapolis Police] Department.

The data collection that happens within police departments enabled experts in the stop-and-frisk litigation [against] the [New York City Police Department] to shine a spotlight on gross disparities: the rate of stops and searches of Black and brown men and boys [coupled with] the low rate of actually acquiring contraband. They found that the rate of securing contraband from white individuals who had been stopped and frisked was so much higher because the police were actually using discretion.

There’s powerful data collection that happens in our criminal courts. Studies show that, all factors being equal, judges are rendering longer and harsher sentences for Black defendants. These judges are setting higher bail. You can isolate all these other factors, but race is the difference. That’s very powerful—to be able to document and publish those findings.

There has also been some really good social science research on implicit bias and the way that it operates. We could all take [implicit association tests] on our computers. You could do a training with your employees. To start with, there is this recognition, this acknowledgment, that we all have implicit bias.

And how do we use that information and not just let people off the hook?

Let’s talk about it. Social science research shows that when there’s recognition that we harbor implicit bias, that awareness can help mitigate [such] bias impacting our daily interactions and decisions.

What about people’s decision to protest during the pandemic? Are you worried that protesters will get sick and spread COVID-19?

Of course. I worry that there will be a second wave of infections. But I think that also speaks to how pressing the issue is and how strongly people feel about it—that they are risking their lives to bring attention to the rampant and lethal mistreatment of Black and brown bodies at the hands of law enforcement.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Suggested Results

Antes de cambiar....

Esta página no está disponible en español

¿Le gustaría continuar en la página de inicio de Brennan Center en español?

al Brennan Center en inglés

al Brennan Center en español

Informed citizens are our democracy’s best defense.

We respect your privacy .

- Research & Reports

Protecting Against Police Brutality and Official Misconduct

Amendments to the criminal civil rights law could provide the federal government with a powerful tool to pursue law enforcement accountability.

- Eric H. Holder Jr.

- Download Report

- Download Annotated Proposal

The protest movement sparked by George Floyd’s killing last year has forced a nationwide reckoning with a wide range of deep-rooted racial inequities — in our economy, in health care, in education, and even in our democracy — that undermine the American promise of freedom and justice for all. That tragic incident provoked widespread demonstrations and stirred strong emotions from people across our nation.

While our state and local governments wrestle with how to reimagine relationships between police and the communities they serve, the Justice Department has long been hamstrung in its ability to mete out justice when people’s civil rights are violated.

The Civil Rights Acts passed during Reconstruction made it a federal crime to deprive someone of their constitutional rights while acting in an official capacity, a provision now known as Section 242. Today, when state or local law enforcement are accused of misconduct, the federal government is often seen as the best avenue for justice — to conduct a neutral investigation and to serve as a backstop when state or local investigations falter. I’m proud that the Justice Department pursued more Section 242 cases under my leadership than under any other attorney general before or since.

But due to Section 242’s vague wording and a series of Supreme Court decisions that raised the standard of proof needed for a civil rights violation, it’s often difficult for federal prosecutors to hold law enforcement accountable using this statute.

This timely report outlines changes to Section 242 that would clarify its scope, making it easier to bring cases and win convictions for civil rights violations of these kinds. Changing the law would allow for charges in cases where prosecutors might currently conclude that the standard of proof cannot be met. Perhaps more important, it attempts to deter potential future misconduct by acting as a nationwide reminder to law enforcement and other public officials of the constitutional limits on their authority.

The statutory changes recommended in this proposal are carefully designed to better protect civil rights that are already recognized. And because Black, Latino, and Native Americans are disproportionately victimized by the kinds of official misconduct the proposal addresses, these changes would advance racial justice.

This proposal would also help ensure that law enforcement officers in every part of the United States live up to the same high standards of professionalism. I have immense regard for the vital role that police play in all of America’s communities and for the sacrifices that they and their families are too often called to make on behalf of their country. It is in great part for their sake — and for their safety — that we must seek to build trust in all communities.

We need to send a clear message that the Constitution and laws of the United States prohibit public officials from engaging in excessive force, sexual misconduct, and deprivation of needed medical care. This proposal will better allow the Justice Department to pursue justice in every appropriate case, across the country.

Eric H. Holder Jr. Eighty-Second Attorney General of the United States

Introduction

Excessive use of force by law enforcement, sexual abuse by public officials and others in positions of authority, and the denial of needed medical care to people in police or correctional custody undermine the rule of law, our government, and our systems of justice.

When public officials engage in misconduct, people expect justice, often in the form of a federal investigation and criminal prosecution. In 2020 alone, instances of police violence, including the killings of George Floyd, Rayshard Brooks, and Breonna Taylor and the shooting of Jacob Blake, led to demands for increased police accountability and federal civil rights investigations. footnote1_d7iNeJB2Vz3v 1 See Rashawn Ray, “How Can We Enhance Police Accountability in the United States?,” in Policy 2020 , Brookings Institution, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/policy2020/votervital/how-can-we-enhance-police-accountability-in-the-united-states/ [ https://perma.cc/8Z9S-GRCU ]; and Elliot C. McLaughlin, “Breonna Taylor Investigations Are Far from Over as Demands for Transparency Mount,” CNN, September 24, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/09/24/us/breonna-taylor-investigations-remaining/index.html [ https://perma.cc/4SR6-FG85 ]. See also, e.g., U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of California, “Federal, State and Local Law Enforcement Statement on the Death of George Floyd and Riots,” press release, May 31, 2020, https://www.justice.gov/usao-edca/pr/federal-state-and-local-law-enforcement-statement-death-george-floyd-and-riots [ https://perma.cc/V69J-49JR ]; and U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Wisconsin, “Statement Regarding Federal Civil Rights Investigation into Shooting of Mr. Jacob Blake,” press release, January 5, 2021, https://www.justice.gov/usao-edwi/pr/statement-regarding-federal-civil-rights-investigation-shooting-mr-jacob-blake [ https://perma.cc/5GCM-WJ7H ].

For almost all incidents involving violence by law enforcement, there is one federal criminal law that applies: 18 U.S.C. § 242. Unlike nearly all other criminal laws, the statute does not clearly define what conduct is a criminal act. It describes the circumstances under which a person, acting with the authority of government, can be held criminally responsible for violating someone’s constitutional rights, but it does not make clear to officials what particular actions they cannot take. footnote2_ijZv1tfVMpAe 2 Throughout this report, people who could be charged under § 242 are most often referred to as “public officials” or “law enforcement.” The Supreme Court has held, however, that § 242 may also be used to prosecute private actors whose authority to act in a given situation is derived from the state, such as a guard at a privately run prison. United States v. Price, 383 U.S. 787, 794 (1966), https://caselaw.findlaw.com/us-supreme-court/383/787.html [ https://perma.cc/V6FU-ZQR6 ] (“To act ‘under color’ of law does not require that the accused be an officer of the State. It is enough that he is a willful participant in joint activity with the State or its agents.”).