What is Solution-Focused Therapy: 3 Essential Techniques

You’re at an important business meeting, and you’re there to discuss some problems your company is having with its production.

At the meeting, you explain what’s causing the problems: The widget-producing machine your company uses is getting old and slowing down. The machine is made up of hundreds of small parts that work in concert, and it would be much more expensive to replace each of these old, worn-down parts than to buy a new widget-producing machine.

You are hoping to convey to the other meeting attendees the impact of the problem, and the importance of buying a new widget-producing machine. You give a comprehensive overview of the problem and how it is impacting production.

One meeting attendee asks, “So which part of the machine, exactly, is getting worn down?” Another says, “Please explain in detail how our widget-producing machine works.” Yet another asks, “How does the new machine improve upon each of the components of the machine?” A fourth attendee asks, “Why is it getting worn down? We should discuss how the machine was made in order to fully understand why it is wearing down now.”

You are probably starting to feel frustrated that your colleagues’ questions don’t address the real issue. You might be thinking, “What does it matter how the machine got worn down when buying a new one would fix the problem?” In this scenario, it is much more important to buy a new widget-producing machine than it is to understand why machinery wears down over time.

When we’re seeking solutions, it’s not always helpful to get bogged down in the details. We want results, not a narrative about how or why things became the way they are.

This is the idea behind solution-focused therapy . For many people, it is often more important to find solutions than it is to analyze the problem in great detail. This article will cover what solution-focused therapy is, how it’s applied, and what its limitations are.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free . These science-based exercises will explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

What is solution-focused therapy, theory behind the solution-focused approach, solution-focused model, popular techniques and interventions, sfbt treatment plan: an example, technologies to execute an sfbt treatment plan (incl. quenza), limitations of sfbt counseling, what does sfbt have to do with positive psychology, a take-home message.

Solution-focused therapy, also called solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT), is a type of therapy that places far more importance on discussing solutions than problems (Berg, n.d.). Of course, you must discuss the problem to find a solution, but beyond understanding what the problem is and deciding how to address it, solution-focused therapy will not dwell on every detail of the problem you are experiencing.

Solution-focused brief therapy doesn’t require a deep dive into your childhood and the ways in which your past has influenced your present. Instead, it will root your sessions firmly in the present while working toward a future in which your current problems have less of an impact on your life (Iveson, 2002).

This solution-centric form of therapy grew out of the field of family therapy in the 1980s. Creators Steve de Shazer and Insoo Kim Berg noticed that most therapy sessions were spent discussing symptoms, issues, and problems.

De Shazer and Berg saw an opportunity for quicker relief from negative symptoms in a new form of therapy that emphasized quick, specific problem-solving rather than an ongoing discussion of the problem itself.

The word “brief” in solution-focused brief therapy is key. The goal of SFBT is to find and implement a solution to the problem or problems as soon as possible to minimize time spent in therapy and, more importantly, time spent struggling or suffering (Antin, 2018).

SFBT is committed to finding realistic, workable solutions for clients as quickly as possible, and the efficacy of this treatment has influenced its spread around the world and use in multiple contexts.

SFBT has been successfully applied in individual, couples, and family therapy. The problems it can address are wide-ranging, from the normal stressors of life to high-impact life events.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Exercises (PDF)

Enhance wellbeing with these free, science-based exercises that draw on the latest insights from positive psychology.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

The solution-focused approach of SFBT is founded in de Shazer and Berg’s idea that the solutions to one’s problems are typically found in the “exceptions” to the problem, meaning the times when the problem is not actively affecting the individual (Iveson, 2002).

This approach is a logical one—to find a lasting solution to a problem, it is rational to look first at those times in which the problem lacks its usual potency.

For example, if a client is struggling with excruciating shyness, but typically has no trouble speaking to his or her coworkers, a solution-focused therapist would target the client’s interactions at work as an exception to the client’s usual shyness. Once the client and therapist have discovered an exception, they will work as a team to find out how the exception is different from the client’s usual experiences with the problem.

The therapist will help the client formulate a solution based on what sets the exception scenario apart, and aid the client in setting goals and implementing the solution.

You may have noticed that this type of therapy relies heavily on the therapist and client working together. Indeed, SFBT works on the assumption that every individual has at least some level of motivation to address their problem or problems and to find solutions that improve their quality of life .

This motivation on the part of the client is an essential piece of the model that drives SFBT (Miller & Rollnick, 2013).

Solution-focused theorists and therapists believe that generally, people develop default problem patterns based on their experiences, as well as default solution patterns.

These patterns dictate an individual’s usual way of experiencing a problem and his or her usual way of coping with problems (Focus on Solutions, 2013).

The solution-focused model holds that focusing only on problems is not an effective way of solving them. Instead, SFBT targets clients’ default solution patterns, evaluates them for efficacy, and modifies or replaces them with problem-solving approaches that work (Focus on Solutions, 2013).

In addition to this foundational belief, the SFBT model is based on the following assumptions:

- Change is constant and certain;

- Emphasis should be on what is changeable and possible;

- Clients must want to change;

- Clients are the experts in therapy and must develop their own goals;

- Clients already have the resources and strengths to solve their problems;

- Therapy is short-term;

- The focus must be on the future—a client’s history is not a key part of this type of therapy (Counselling Directory, 2017).

Based on these assumptions, the model instructs therapists to do the following in their sessions with clients:

- Ask questions rather than “selling” answers;

- Notice and reinforce evidence of the client’s positive qualities, strengths, resources, and general competence to solve their own problems;

- Work with what people can do rather than focusing on what they can’t do;

- Pinpoint the behaviors a client is already engaging in that are helpful and effective and find new ways to facilitate problem-solving through these behaviors;

- Focus on the details of the solution instead of the problem;

- Develop action plans that work for the client (Focus on Solutions, 2013).

SFBT therapists aim to bring out the skills, strengths, and abilities that clients already possess rather than attempting to build new competencies from scratch. This assumption of a client’s competence is one of the reasons this therapy can be administered in a short timeframe—it is much quicker to harness the resources clients already have than to create and nurture new resources.

Beyond these basic activities, there are many techniques and exercises used in SFBT to promote problem-solving and enhance clients’ ability to work through their own problems.

Working with a therapist is generally recommended when you are facing overwhelming or particularly difficult problems, but not all problems require a licensed professional to solve.

For each technique listed below, it will be noted if it can be used as a standalone technique.

Asking good questions is vital in any form of therapy, but SFBT formalized this practice into a technique that specifies a certain set of questions intended to provoke thinking and discussion about goal-setting and problem-solving.

One such question is the “coping question.” This question is intended to help clients recognize their own resiliency and identify some of the ways in which they already cope with their problems effectively.

There are many ways to phrase this sort of question, but generally, a coping question is worded something like, “How do you manage, in the face of such difficulty, to fulfill your daily obligations?” (Antin, 2018).

Another type of question common in SFBT is the “miracle question.” The miracle question encourages clients to imagine a future in which their problems are no longer affecting their lives. Imagining this desired future will help clients see a path forward, both allowing them to believe in the possibility of this future and helping them to identify concrete steps they can take to make it happen.

This question is generally asked in the following manner: “Imagine that a miracle has occurred. This problem you are struggling with is suddenly absent from your life. What does your life look like without this problem?” (Antin, 2018).

If the miracle question is unlikely to work, or if the client is having trouble imagining this miracle future, the SFBT therapist can use “best hopes” questions instead. The client’s answers to these questions will help establish what the client is hoping to achieve and help him or her set realistic and achievable goals.

The “best hopes” questions can include the following:

- What are your best hopes for today’s session?

- What needs to happen in this session to enable you to leave thinking it was worthwhile?

- How will you know things are “good enough” for our sessions to end?

- What needs to happen in these sessions so that your relatives/friends/coworkers can say, “I’m really glad you went to see [the therapist]”? (Vinnicombe, n.d.).

To identify the exceptions to the problems plaguing clients, therapists will ask “exception questions.” These are questions that ask about clients’ experiences both with and without their problems. This helps to distinguish between circumstances in which the problems are most active and the circumstances in which the problems either hold no power or have diminished power over clients’ moods or thoughts.

Exception questions can include:

- Tell me about the times when you felt the happiest;

- What was it about that day that made it a better day?

- Can you think of times when the problem was not present in your life? (Counselling Directory, 2017).

Another question frequently used by SFBT practitioners is the “scaling question.”

It asks clients to rate their experiences (such as how their problems are currently affecting them, how confident they are in their treatment, and how they think the treatment is progressing) on a scale from 0 (lowest) to 10 (highest). This helps the therapist to gauge progress and learn more about clients’ motivation and confidence in finding a solution.

For example, an SFBT therapist may ask, “On a scale from 0 to 10, how would you rate your progress in finding and implementing a solution to your problem?” (Antin, 2018).

Do One Thing Different

This exercise can be completed individually, but the handout may need to be modified for adult or adolescent users.

This exercise is intended to help the client or individual to learn how to break his or her problem patterns and build strategies to simply make things go better.

The handout breaks the exercise into the following steps (Coffen, n.d.):

- Think about the things you do in a problem situation. Change any part you can. Choose to change one thing, such as the timing, your body patterns (what you do with your body), what you say, the location, or the order in which you do things;

- Think of a time that things did not go well for you. When does that happen? What part of that problem situation will you do differently now?

- Think of something done by somebody else does that makes the problem better. Try doing what they do the next time the problem comes up. Or, think of something that you have done in the past that made things go better. Try doing that the next time the problem comes up;

- Think of something that somebody else does that works to make things go better. What is the person’s name and what do they do that you will try?

- Think of something that you have done in the past that helped make things go better. What did you do that you will do next time?

- Feelings tell you that you need to do something. Your brain tells you what to do. Understand what your feelings are but do not let them determine your actions. Let your brain determine the actions;

- Feelings are great advisors but poor masters (advisors give information and help you know what you could do; masters don’t give you choices);

- Think of a feeling that used to get you into trouble. What feeling do you want to stop getting you into trouble?

- Think of what information that feeling is telling you. What does the feeling suggest you should do that would help things go better?

- Change what you focus on. What you pay attention to will become bigger in your life and you will notice it more and more. To solve a problem, try changing your focus or your perspective.

- Think of something that you are focusing on too much. What gets you into trouble when you focus on it?

- Think of something that you will focus on instead. What will you focus on that will not get you into trouble?

- Imagine a time in the future when you aren’t having the problem you are having right now. Work backward to figure out what you could do now to make that future come true;

- Think of what will be different for you in the future when things are going better;

- Think of one thing that you would be doing differently before things could go better in the future. What one thing will you do differently?

- Sometimes people with problems talk about how other people cause those problems and why it’s impossible to do better. Change your story. Talk about times when the problem was not happening and what you were doing at that time. Control what you can control. You can’t control other people, but you can change your actions, and that might change what other people do;

- Think of a time when you were not having the problem that is bothering you. Talk about that time.

- If you believe in a god or a higher power, focus on God to get things to go better. When you are focused on God or you are asking God to help you, things might go better for you.

- Do you believe in a god or a higher power? Talk about how you will seek help from your god to make things go better.

- Use action talk to get things to go better. Action talk sticks to the facts, addresses only the things you can see, and doesn’t address what you believe another person was thinking or feeling—we have no way of knowing that for sure. When you make a complaint, talk about the action that you do not like. When you make a request, talk about what action you want the person to do. When you praise someone, talk about what action you liked;

- Make a complaint about someone cheating at a game using action talk;

- Make a request for someone to play fairly using action talk;

- Thank someone for doing what you asked using action talk.

Following these eight steps and answering the questions thoughtfully will help people recognize their strengths and resources, identify ways in which they can overcome problems, plan and set goals to address problems, and practice useful skills.

While this handout can be extremely effective for SFBT, it can also be used in other therapies or circumstances.

To see this handout and download it for you or your clients, click here .

Presupposing Change

The “presupposing change” technique has great potential in SFBT, in part because when people are experiencing problems, they have a tendency to focus on the problems and ignore the positive changes in their life.

It can be difficult to recognize the good things happening in your life when you are struggling with a painful or particularly troublesome problem.

This technique is intended to help clients be attentive to the positive things in their lives, no matter how small or seemingly insignificant. Any positive change or tiny step of progress should be noted, so clients can both celebrate their wins and draw from past wins to facilitate future wins.

Presupposing change is a strikingly simple technique to use: Ask questions that assume positive changes. This can include questions like, “What’s different or better since I saw you last time?”

If clients are struggling to come up with evidence of positive change or are convinced that there has been no positive change, the therapist can ask questions that encourage clients to think about their abilities to effectively cope with problems, like, How come things aren’t worse for you? What stopped total disaster from occurring? How did you avoid falling apart? (Australian Institute of Professional Counsellors, 2009).

The most powerful word in the Solution Focused Brief Therapy vocabulary – The Solution Focused Universe

A typical treatment plan in SFBT will include several factors relevant to the treatment, including:

- The reason for referral, or the problem the client is experiencing that brought him or her to treatment;

- A diagnosis (if any);

- List of medications taken (if any);

- Current symptoms;

- Support for the client (family, friends, other mental health professionals, etc.);

- Modality or treatment type;

- Frequency of treatment;

- Goals and objectives;

- Measurement criteria for progress on goals;

- Client strengths ;

- Barriers to progress.

All of these are common and important components of a successful treatment plan. Some of these components (e.g., diagnosis and medications) may be unaddressed or acknowledged only as a formality in SFBT due to its usual focus on less severe mental health issues. Others are vital to treatment progress and potential success in SFBT, including goals, objectives, measurement criteria, and client strengths.

To this end, therapists are increasingly leveraging the benefits of technology to help develop, execute, and evaluate the outcomes of treatment plans efficiently.

Among these technologies are many digital platforms that therapists can use to carry out some steps in clients’ treatment plans outside of face-to-face sessions.

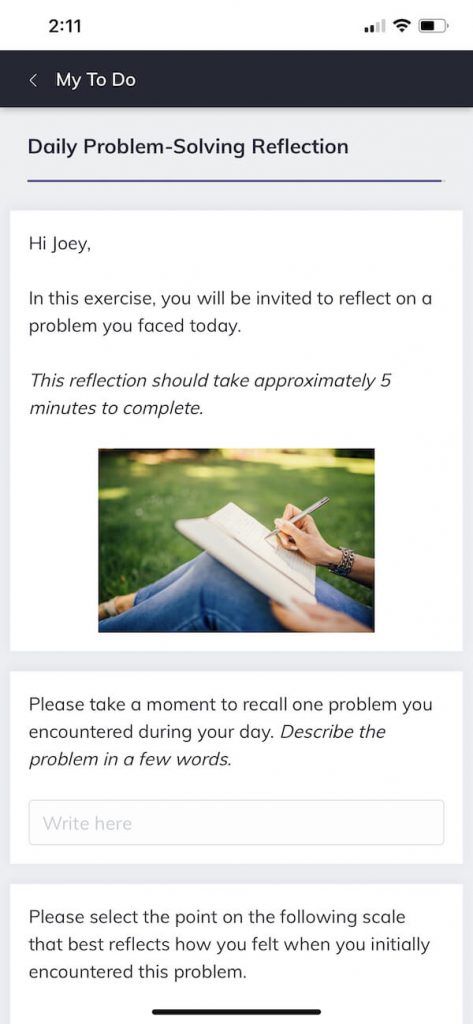

For example, by adopting a versatile blended care platform such as Quenza , an SFBT practitioner may carry out some of the initial steps in the assessment/diagnosis phase of a treatment plan, such as by inviting the client to complete a digital diagnostic questionnaire.

Likewise, the therapist may use the platform to send digital activities to the client’s smartphone, such as an end-of-day reflection inviting the client to recount their application of the ‘Do One Thing Different’ technique to overcome a problem.

These are just a few ideas for how you might use a customizable blended care tool such as Quenza to help carry out several of the steps in an SFBT treatment plan.

Some of the potential disadvantages for therapists include (George, 2010):

- The potential for clients to focus on problems that the therapist believes are secondary problems. For example, the client may focus on a current relationship problem rather than the underlying self-esteem problem that is causing the relationship woes. SFBT dictates that the client is the expert, and the therapist must take what the client says at face value;

- The client may decide that the treatment is successful or complete before the therapist is ready to make the same decision. This focus on taking what the client says at face value may mean the therapist must end treatment before they are convinced that the client is truly ready;

- The hard work of the therapist may be ignored. When conducted successfully, it may seem that clients solved their problems by themselves, and didn’t need the help of a therapist at all. An SFBT therapist may rarely get credit for the work they do but must take all the blame when sessions end unsuccessfully.

Some of the potential limitations for clients include (Antin, 2018):

- The focus on quick solutions may miss some important underlying issues;

- The quick, goal-oriented nature of SFBT may not allow for an emotional, empathetic connection between therapist and client.

- If the client wants to discuss factors outside of their immediate ability to effect change, SFBT may be frustrating in its assumption that clients are always able to fix or address their problems.

Generally, SFBT can be an excellent treatment for many of the common stressors people experience in their lives, but it may be inappropriate if clients want to concentrate more on their symptoms and how they got to where they are today. As noted earlier, it is also generally not appropriate for clients with major mental health disorders.

17 Top-Rated Positive Psychology Exercises for Practitioners

Expand your arsenal and impact with these 17 Positive Psychology Exercises [PDF] , scientifically designed to promote human flourishing, meaning, and wellbeing.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

First, both SFBT and positive psychology share a focus on the positive—on what people already have going for them and on what actions they can take. While problems are discussed and considered in SFBT, most of the time and energy is spent on discussing, thinking about, and researching what is already good, effective, and successful.

Second, both SFBT and positive psychology consider the individual to be his or her own best advocate, the source of information on his or her problems and potential solutions, and the architect of his or her own treatment and life success. The individual is considered competent, able, and “enough” in both SFBT and positive psychology.

This assumption of the inherent competence of individuals has run both subfields into murky waters and provoked criticism, particularly when systemic and societal factors are considered. While no respectable psychologist would disagree that an individual is generally in control of his or her own actions and, therefore, future, there is considerable debate about what level of influence other factors have on an individual’s life.

While many of these criticisms are valid and bring up important points for discussion, we won’t dive too deep into them in this piece. Suffice it to say that both SFBT and positive psychology have important places in the field of psychology and, like any subfield, may not apply to everyone and to all circumstances.

However, when they do apply, they are both capable of producing positive, lasting, and life-changing results.

Solution-focused therapy puts problem-solving at the forefront of the conversation and can be particularly useful for clients who aren’t suffering from major mental health issues and need help solving a particular problem (or problems). Rather than spending years in therapy, SFBT allows such clients to find solutions and get results quickly.

Have you ever tried Solution-Focused Brief Therapy, as a therapist or as a client? What did you think of the focus on solutions? Do you think SFBT misses anything important by taking the spotlight off the client’s problem(s)? Let us know in the comments section.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free .

Antin, L. (2018). Solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT). Good Therapy. Retrieved from https://www.goodtherapy.org/learn-about-therapy/types/solution-focused-therapy

- Australian Institute of Professional Counsellors. (2009, March 30). Solution-focused techniques. Counseling Connection. Retrieved from http://www.counsellingconnection.com/index.php/2009/03/30/solution-focused-techniques/

- Berg, I. K. (n.d.). About solution-focused brief therapy. SFBTA . Retrieved from http://www.sfbta.org/about_sfbt.html

- Coffen, R. (n.d.). Do one thing different [Handout]. Retrieved from https://www.andrews.edu/~coffen/Do%20one%20thing%20different.pdf

- Focus on Solutions. (2013, October 28). The brief solution-focused model. Focus on solutions: Leaders in solution-focused training. Retrieved from http://www.focusonsolutions.co.uk/solutionfocused/

- George, E. (2010). Disadvantages of solution focus? BRIEF. Retrieved from https://www.brief.org.uk/resources/faq/disadvantages-of-solution-focus

- Iveson, C. (2002). Solution-focused brief therapy. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 8 (2), 149-156.

- Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2013). Motivational interviewing: Helping people change (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Vinnicombe, G. (n.d.). Greg’s SFBT handout. Useful Conversations. Retrieved from http://www.usefulconversations.com/downloads

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Thank you. I’m about to start an MMFT internship, and SFBT is the model I prefer. You put everything in perspective.

Great insights. I have a client who has become a bit disengaged with our work together. This gives me a really helpful new approach for our upcoming sessions. He’s very focused on the problem and wanting a “quick fix.” This might at least get us on that path. Thank you!

Hi Courtney, great paper! I will like to know more about the limitations to SFT and noticed that you provided an intext citation to Antin 2016. Would you be able to provide the full reference? Thank you!

Thank you for bringing this to our attention. The reference has now been updated in the reference list — this should be Antin (2018):

– Nicole | Community Manager

The only thing tat was revealed to me while reading this article is the client being able to recognize the downfall of what got them into their problem in the first place. I felt that maybe a person should understand the problem to the extent that they may understand how to recognize what led to the problem in the first place. Understanding the process of how something broke down would give one knowledge and wisdom that may be able to be applied in future instances when something may go wrong again. Even if the thing is new (machine or person) having the wisdom and understanding of the cause that led to the effect may help prevent and or overcome an arising problem in the future. Not being able to recognize the process that brought down the machine and or human may be like adhering to ignorance, although they say ignorance is bliss in case of an emergency it would be better to be informed rather then blindly ignorant, as the knowledge of how the problem surfaced in the first place may alleviate unwarranted suffering sooner rather than later. But then again looking at it this way I may work myself out of a job if my clients never came back to see me. However is it about me or them or the greater societal structural good that we can induce through our education, skills, training, experience, and good will good faith effort to instill social justice coupled with lasting change for the betterment of human society and the world as a whole.

Very very helpful, thank you for writing. Just one point “While no respectable psychologist would disagree that an individual is generally in control of his or her own actions and, therefore, future, there is considerable debate about what level of influence other factors have on an individual’s life.” I think any psychologist that has worked in neurological dysfunction would probably acknowledge consciousness and ‘voluntary control’ are not that straight-forward. Generally though, I suppose there’s that whole debate of if we are ever in control of our actions or even our thoughts. It may well boil down to what we mean by ‘we’, as in what are we? A bundle of fibres acting on memories and impulses? A unique body of energy guided by intangible forces? Maybe I am not a respectable psychologist 🙂

This article provided me with insight on how to proceed with a role-play session in my CBT graduate course. Thank you!

Hi Derrick, That’s fantastic that you were able to find some guidance in this post. Best of luck with your grad students! – Nicole | Community Manager

Thank You…Great input and clarity . I now have light…

I was looking everywhere for a simple explanation for my essay and this is it!! thank you so much for this is was very useful and I learned a lot.

Very well done. Thank you for the multitude of insights.

Thank you for such a good passage discussed. I really have a great time understanding it.

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Holistic Therapy: Healing Mind, Body, and Spirit

The term “holistic” in health care can be dated back to Hippocrates over 2,500 years ago (Relman, 1979). Hippocrates highlighted the importance of viewing individuals [...]

Trauma-Informed Therapy Explained (& 9 Techniques)

Trauma varies significantly in its effect on individuals. While some people may quickly recover from an adverse event, others might find their coping abilities profoundly [...]

Recreational Therapy Explained: 6 Degrees & Programs

Let’s face it, on a scale of hot or not, attending therapy doesn’t make any client jump with excitement. But what if that can be [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (17)

- Positive Parenting (3)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (31)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

Download 3 Free Positive CBT Tools Pack (PDF)

3 Positive CBT Exercises (PDF)

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Brief Therapies in Social Work: Task-Centered Model and Solution-Focused Therapy

Introduction.

- Introductory Works

- Reference Works

- Journal Articles and Scholarly Works

- Task-Centered Organization

- Animal-Assisted Brief Therapy

- Specialized SFT Organizations

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Behavioral Social Work Practice

- Cognitive Behavior Therapies with Diverse and Stressed Populations

- Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

- Direct Practice in Social Work

- Evidence-based Social Work Practice

- Interpersonal Psychotherapy

- Interviewing

- Motivational Interviewing

- Psychosocial Framework

- Psychotherapy and Social Work

- Solution-Focused Therapy

- Strengths Perspective

- Strengths-Based Models in Social Work

- Task-Centered Practice

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Child Welfare Effectiveness

- Immigration and Child Welfare

- International Human Trafficking

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Brief Therapies in Social Work: Task-Centered Model and Solution-Focused Therapy by Cynthia Franklin , Krystallynne Mikle LAST REVIEWED: 06 May 2015 LAST MODIFIED: 30 September 2013 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780195389678-0188

Brief therapies serve as evidenced-based practices that place a strong emphasis on effective, time-limited treatments that aid in resolving clients’ presenting problems. The resources presented in this article summarize for professionals and educators the abundant literature evaluating brief therapies within social work practice. Brief therapies have appeared in many different schools of psychotherapy, and several approaches have also evolved within social work practice, but two approaches—the task-centered model and solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT)—stand out as being grounded in research and have also gained international acclaim as important interventions for implementation and further study. These two approaches are the focus of this bibliography. The task-centered model and SFBT were developed by social work practitioners and researchers for the purposes of making clinical practice more effective, and they share a common bond in hoping to improve the services delivered to clients. Since the development of the task-centered and solution-focused approaches, brief therapies have become essential to the work of all types of psychotherapists and clinicians, and many of the principles and practices of brief therapy that are a part of the task-centered and solution-focused approaches are now essential to psychotherapy training. Clinical social workers practicing from the perspective of the task-centered model and SFBT approaches work from several brief therapy assumptions. The first regards the client/therapist relationship. The best way to help clients is to work within a collaborative relationship to discover options for coping and new behavior that may also lead to specific tasks and solutions for change that are identified by the client. Second is the assumption that change can happen quickly and can be lasting. Third, focus on the past may not be as helpful to most clients as a focus on the present and the future. The fourth regards a pragmatic perspective about where the change occurs. The best approach to practice is pragmatic, and effective practitioners recognize that what happens in a client’s life is more important than what happens in a social worker’s office. The fifth assumption is that change can happen more quickly and be maintained when practitioners utilize the strengths and resources that exist within the client and his or her environment. The next assumption is that a small change made by clients may cause significant and major life changes. The seventh assumption is associated with creating goals. It is important to focus on small, concrete goal construction and helping the client move toward small steps to achieve those goals. The next regards change. Change is viewed as hard work and involves focused effort and commitment from the client and social worker. There will be homework assignments and following through on tasks. Also, it is assumed that it is important to establish and maintain a clear treatment focus (often considered the most important element in brief treatment). Parsimony is also considered to be a guiding principle (i.e., given two equally effective treatments, the one requiring less investment of time and energy is preferable). Last, it is assumed that without evidence to the contrary, the client’s stated problem is taken as the valid focus of treatment. The task-centered model and SFBT have developed a strong empirical base, and both approaches operate from a goal-oriented and strengths perspective. Both approaches have numerous applications and have successfully been used with many different types of clients and practice settings. Both approaches have also been expanded to applications in macro social work that focus on work within management- and community-based practices. For related Oxford Bibliographies entries, see Task-Centered Practice and Solution-Focused Therapy .

Task-Centered Model Literature

The task-centered model is an empirically grounded approach to social work practice that appeared in the mid-1960s at Columbia University and was developed in response to research reports that indicated social work was not effective with clients. William J. Reid was the chief researcher who helped develop this model, and he integrated many therapeutic perspectives to create the task-centered approach, including ideas from behavioral therapies. The task-centered model evolved out of the psychodynamic practice and uses a brief, problem-solving approach to help clients resolve presenting problems. The task-centered model is currently used in clinical social work and group work and may also be applied to other types of social work practice.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Social Work »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Adolescent Depression

- Adolescent Pregnancy

- Adolescents

- Adoption Home Study Assessments

- Adult Protective Services in the United States

- African Americans

- Aging out of foster care

- Aging, Physical Health and

- Alcohol and Drug Abuse Problems

- Alcohol and Drug Problems, Prevention of Adolescent and Yo...

- Alcohol Problems: Practice Interventions

- Alcohol Use Disorder

- Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias

- Anti-Oppressive Practice

- Asian Americans

- Asian-American Youth

- Autism Spectrum Disorders

- Baccalaureate Social Workers

- Behavioral Health

- Bereavement Practice

- Bisexuality

- Brief Therapies in Social Work: Task-Centered Model and So...

- Bullying and Social Work Intervention

- Canadian Social Welfare, History of

- Case Management in Mental Health in the United States

- Central American Migration to the United States

- Child Maltreatment Prevention

- Child Neglect and Emotional Maltreatment

- Child Poverty

- Child Sexual Abuse

- Child Welfare

- Child Welfare and Child Protection in Europe, History of

- Child Welfare Practice with LGBTQ Youth and Families

- Children of Incarcerated Parents

- Christianity and Social Work

- Chronic Illness

- Clinical Social Work Practice with Adult Lesbians

- Clinical Social Work Practice with Males

- Cognitive Behavior Therapies with Diverse and Stressed Pop...

- Cognitive Processing Therapy

- Community Development

- Community Policing

- Community-Based Participatory Research

- Community-Needs Assessment

- Comparative Social Work

- Computational Social Welfare: Applying Data Science in Soc...

- Conflict Resolution

- Council on Social Work Education

- Counseling Female Offenders

- Criminal Justice

- Crisis Interventions

- Cultural Competence and Ethnic Sensitive Practice

- Culture, Ethnicity, Substance Use, and Substance Use Disor...

- Dementia Care

- Dementia Care, Ethical Aspects of

- Depression and Cancer

- Development and Infancy (Birth to Age Three)

- Differential Response in Child Welfare

- Digital Storytelling for Social Work Interventions

- Disabilities

- Disability and Disability Culture

- Domestic Violence Among Immigrants

- Early Pregnancy and Parenthood Among Child Welfare–Involve...

- Eating Disorders

- Ecological Framework

- Economic Evaluation

- Elder Mistreatment

- End-of-Life Decisions

- Epigenetics for Social Workers

- Ethical Issues in Social Work and Technology

- Ethics and Values in Social Work

- European Institutions and Social Work

- European Union, Justice and Home Affairs in the

- Evidence-based Social Work Practice: Finding Evidence

- Evidence-based Social Work Practice: Issues, Controversies...

- Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs

- Families with Gay, Lesbian, or Bisexual Parents

- Family Caregiving

- Family Group Conferencing

- Family Policy

- Family Services

- Family Therapy

- Family Violence

- Fathering Among Families Served By Child Welfare

- Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders

- Field Education

- Financial Literacy and Social Work

- Financing Health-Care Delivery in the United States

- Forensic Social Work

- Foster Care

- Foster care and siblings

- Gender, Violence, and Trauma in Immigration Detention in t...

- Generalist Practice and Advanced Generalist Practice

- Grounded Theory

- Group Work across Populations, Challenges, and Settings

- Group Work, Research, Best Practices, and Evidence-based

- Harm Reduction

- Health Care Reform

- Health Disparities

- Health Social Work

- History of Social Work and Social Welfare, 1900–1950

- History of Social Work and Social Welfare, 1950-1980

- History of Social Work and Social Welfare, pre-1900

- History of Social Work from 1980-2014

- History of Social Work in China

- History of Social Work in Northern Ireland

- History of Social Work in the Republic of Ireland

- History of Social Work in the United Kingdom

- HIV/AIDS and Children

- HIV/AIDS Prevention with Adolescents

- Homelessness

- Homelessness: Ending Homelessness as a Grand Challenge

- Homelessness Outside the United States

- Human Needs

- Human Trafficking, Victims of

- Immigrant Integration in the United States

- Immigrant Policy in the United States

- Immigrants and Refugees

- Immigrants and Refugees: Evidence-based Social Work Practi...

- Immigration and Health Disparities

- Immigration and Intimate Partner Violence

- Immigration and Poverty

- Immigration and Spirituality

- Immigration and Substance Use

- Immigration and Trauma

- Impact of Emerging Technology in Social Work Practice

- Impaired Professionals

- Implementation Science and Practice

- Indigenous Peoples

- Individual Placement and Support (IPS) Supported Employmen...

- In-home Child Welfare Services

- Intergenerational Transmission of Maltreatment

- International Social Welfare

- International Social Work

- International Social Work and Education

- International Social Work and Social Welfare in Southern A...

- Internet and Video Game Addiction

- Intervention with Traumatized Populations

- Intimate-Partner Violence

- Juvenile Justice

- Kinship Care

- Korean Americans

- Latinos and Latinas

- Law, Social Work and the

- LGBTQ Populations and Social Work

- Mainland European Social Work, History of

- Major Depressive Disorder

- Management and Administration in Social Work

- Maternal Mental Health

- Measurement, Scales, and Indices

- Medical Illness

- Men: Health and Mental Health Care

- Mental Health

- Mental Health Diagnosis and the Addictive Substance Disord...

- Mental Health Needs of Older People, Assessing the

- Mental Illness: Children

- Mental Illness: Elders

- Meta-analysis

- Microskills

- Middle East and North Africa, International Social Work an...

- Military Social Work

- Mixed Methods Research

- Moral distress and injury in social work

- Multiculturalism

- Native Americans

- Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders

- Neighborhood Social Cohesion

- Neuroscience and Social Work

- Nicotine Dependence

- Occupational Social Work

- Organizational Development and Change

- Pain Management

- Palliative Care

- Palliative Care: Evolution and Scope of Practice

- Pandemics and Social Work

- Parent Training

- Personalization

- Person-in-Environment

- Philosophy of Science and Social Work

- Physical Disabilities

- Podcasts and Social Work

- Police Social Work

- Political Social Work in the United States

- Positive Youth Development

- Postmodernism and Social Work

- Postsecondary Education Experiences and Attainment Among Y...

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Practice Interventions and Aging

- Practice Interventions with Adolescents

- Practice Research

- Primary Prevention in the 21st Century

- Productive Engagement of Older Adults

- Profession, Social Work

- Program Development and Grant Writing

- Promoting Smart Decarceration as a Grand Challenge

- Psychiatric Rehabilitation

- Psychoanalysis and Psychodynamic Theory

- Psychoeducation

- Psychometrics

- Psychopathology and Social Work Practice

- Psychopharmacology and Social Work Practice

- Psychosocial Intervention with Women

- Qualitative Research

- Race and Racism

- Readmission Policies in Europe

- Redefining Police Interactions with People Experiencing Me...

- Rehabilitation

- Religiously Affiliated Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research Ethics

- Restorative Justice

- Risk Assessment in Child Protection Services

- Risk Management in Social Work

- Rural Social Work in China

- Rural Social Work Practice

- School Social Work

- School Violence

- School-Based Delinquency Prevention

- Services and Programs for Pregnant and Parenting Youth

- Severe and Persistent Mental Illness: Adults

- Sexual and Gender Minority Immigrants, Refugees, and Asylu...

- Sexual Assault

- Single-System Research Designs

- Social and Economic Impact of US Immigration Policies on U...

- Social Development

- Social Insurance and Social Justice

- Social Intervention Research

- Social Justice and Social Work

- Social Movements

- Social Planning

- Social Policy

- Social Policy in Denmark

- Social Security in the United States (OASDHI)

- Social Work and Islam

- Social Work and Social Welfare in East, West, and Central ...

- Social Work and Social Welfare in Europe

- Social Work Education and Research

- Social Work Leadership

- Social Work Luminaries: Luminaries Contributing to the Cla...

- Social Work Luminaries: Luminaries contributing to the fou...

- Social Work Luminaries: Luminaries Who Contributed to Soci...

- Social Work Regulation

- Social Work Research Methods

- Social Work with Interpreters

- Strategic Planning

- Supplemental Security Income

- Survey Research

- Sustainability: Creating Social Responses to a Changing En...

- Syrian Refugees in Turkey

- Systematic Review Methods

- Technology Adoption in Social Work Education

- Technology for Social Work Interventions

- Technology, Human Relationships, and Human Interaction

- Technology in Social Work

- Terminal Illness

- The Impact of Systemic Racism on Latinxs’ Experiences with...

- Transdisciplinary Science

- Translational Science and Social Work

- Transnational Perspectives in Social Work

- Transtheoretical Model of Change

- Trauma-Informed Care

- Triangulation

- Tribal child welfare practice in the United States

- United States, History of Social Welfare in the

- Universal Basic Income

- Veteran Services

- Vicarious Trauma and Resilience in Social Work Practice wi...

- Vicarious Trauma Redefining PTSD

- Victim Services

- Virtual Reality and Social Work

- Welfare State Reform in France

- Welfare State Theory

- Women and Macro Social Work Practice

- Women's Health Care

- Work and Family in the German Welfare State

- Workforce Development of Social Workers Pre- and Post-Empl...

- Working with Non-Voluntary and Mandated Clients

- Young and Adolescent Lesbians

- Youth at Risk

- Youth Services

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|91.193.111.216]

- 91.193.111.216

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)?

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Rachel Goldman, PhD FTOS, is a licensed psychologist, clinical assistant professor, speaker, wellness expert specializing in eating behaviors, stress management, and health behavior change.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Rachel-Goldman-1000-a42451caacb6423abecbe6b74e628042.jpg)

Verywell / Daniel Fishel

- Effectiveness

- Considerations

- Getting Started

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a type of psychotherapeutic treatment that helps people learn how to identify and change the destructive or disturbing thought patterns that have a negative influence on their behavior and emotions.

Cognitive behavioral therapy combines cognitive therapy with behavior therapy by identifying maladaptive patterns of thinking, emotional responses, or behaviors and replacing them with more desirable patterns.

Cognitive behavioral therapy focuses on changing the automatic negative thoughts that can contribute to and worsen our emotional difficulties, depression , and anxiety . These spontaneous negative thoughts also have a detrimental influence on our mood.

Through CBT, faulty thoughts are identified, challenged, and replaced with more objective, realistic thoughts.

Everything You Need to Know About CBT

This video has been medically reviewed by Steven Gans, MD .

Types of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

CBT encompasses a range of techniques and approaches that address our thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. These can range from structured psychotherapies to self-help practices. Some of the specific types of therapeutic approaches that involve cognitive behavioral therapy include:

- Cognitive therapy centers on identifying and changing inaccurate or distorted thought patterns, emotional responses, and behaviors.

- Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) addresses destructive or disturbing thoughts and behaviors while incorporating treatment strategies such as emotional regulation and mindfulness.

- Multimodal therapy suggests that psychological issues must be treated by addressing seven different but interconnected modalities: behavior, affect, sensation, imagery, cognition, interpersonal factors, and drug/biological considerations.

- Rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT) involves identifying irrational beliefs, actively challenging these beliefs, and finally learning to recognize and change these thought patterns.

While each type of cognitive behavioral therapy takes a different approach, all work to address the underlying thought patterns that contribute to psychological distress.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Techniques

CBT is about more than identifying thought patterns. It uses a wide range of strategies to help people overcome these patterns. Here are just a few examples of techniques used in cognitive behavioral therapy.

Identifying Negative Thoughts

It is important to learn what thoughts, feelings, and situations are contributing to maladaptive behaviors. This process can be difficult, however, especially for people who struggle with introspection . But taking the time to identify these thoughts can also lead to self-discovery and provide insights that are essential to the treatment process.

Practicing New Skills

In cognitive behavioral therapy, people are often taught new skills that can be used in real-world situations. For example, someone with a substance use disorder might practice new coping skills and rehearse ways to avoid or deal with social situations that could potentially trigger a relapse.

Goal-Setting

Goal setting can be an important step in recovery from mental illness, helping you to make changes to improve your health and life. During cognitive behavioral therapy, a therapist can help you build and strengthen your goal-setting skills .

This might involve teaching you how to identify your goal or how to distinguish between short- and long-term goals. It may also include helping you set SMART goals (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-based), with a focus on the process as much as the end outcome.

Problem-Solving

Learning problem-solving skills during cognitive behavioral therapy can help you learn how to identify and solve problems that may arise from life stressors, both big and small. It can also help reduce the negative impact of psychological and physical illness.

Problem-solving in CBT often involves five steps:

- Identify the problem

- Generate a list of potential solutions

- Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each potential solution

- Choose a solution to implement

- Implement the solution

Self-Monitoring

Also known as diary work, self-monitoring is an important cognitive behavioral therapy technique. It involves tracking behaviors, symptoms, or experiences over time and sharing them with your therapist.

Self-monitoring can provide your therapist with the information they need to provide the best treatment. For example, for people with eating disorders, self-monitoring may involve keeping track of eating habits, as well as any thoughts or feelings that went along with consuming a meal or snack.

Additional cognitive behavioral therapy techniques may include journaling , role-playing , engaging in relaxation strategies , and using mental distractions .

What Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Can Help With

Cognitive behavioral therapy can be used as a short-term treatment to help individuals learn to focus on present thoughts and beliefs.

CBT is used to treat a wide range of conditions, including:

- Anger issues

- Bipolar disorder

- Eating disorders

- Panic attacks

- Personality disorders

In addition to mental health conditions, cognitive behavioral therapy has also been found to help people cope with:

- Chronic pain or serious illnesses

- Divorce or break-ups

- Grief or loss

- Low self-esteem

- Relationship problems

- Stress management

Get Help Now

We've tried, tested, and written unbiased reviews of the best online therapy programs including Talkspace, BetterHelp, and ReGain. Find out which option is the best for you.

Benefits of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

The underlying concept behind CBT is that thoughts and feelings play a fundamental role in behavior. For example, a person who spends a lot of time thinking about plane crashes, runway accidents, and other air disasters may avoid air travel as a result.

The goal of cognitive behavioral therapy is to teach people that while they cannot control every aspect of the world around them, they can take control of how they interpret and deal with things in their environment.

CBT is known for providing the following key benefits:

- It helps you develop healthier thought patterns by becoming aware of the negative and often unrealistic thoughts that dampen your feelings and moods.

- It is an effective short-term treatment option as improvements can often be seen in five to 20 sessions.

- It is effective for a wide variety of maladaptive behaviors.

- It is often more affordable than some other types of therapy .

- It is effective whether therapy occurs online or face-to-face.

- It can be used for those who don't require psychotropic medication .

One of the greatest benefits of cognitive behavioral therapy is that it helps clients develop coping skills that can be useful both now and in the future.

Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

CBT emerged during the 1960s and originated in the work of psychiatrist Aaron Beck , who noted that certain types of thinking contributed to emotional problems. Beck labeled these "automatic negative thoughts" and developed the process of cognitive therapy.

Where earlier behavior therapies had focused almost exclusively on associations, reinforcements , and punishments to modify behavior, the cognitive approach addresses how thoughts and feelings affect behaviors.

Today, cognitive behavioral therapy is one of the most well-studied forms of treatment. It has been shown to be effective in the treatment of a range of mental conditions, including anxiety, depression, eating disorders, insomnia, obsessive-compulsive disorder , panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder , and substance use disorder.

- Research indicates that cognitive behavioral therapy is the leading evidence-based treatment for eating disorders .

- CBT has been proven helpful in those with insomnia, as well as those who have a medical condition that interferes with sleep, including those with pain or mood disorders such as depression.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy has been scientifically proven to be effective in treating symptoms of depression and anxiety in children and adolescents.

- A 2018 meta-analysis of 41 studies found that CBT helped improve symptoms in people with anxiety and anxiety-related disorders, including obsessive-compulsive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy has a high level of empirical support for the treatment of substance use disorders, helping people with these disorders improve self-control , avoid triggers, and develop coping mechanisms for daily stressors.

CBT is one of the most researched types of therapy, in part, because treatment is focused on very specific goals and results can be measured relatively easily.

Verywell Mind's Cost of Therapy Survey , which sought to learn more about how Americans deal with the financial burdens associated with therapy, found that Americans overwhelmingly feel the benefits of therapy:

- 80% say therapy is a good investment

- 91% are satisfied with the quality of therapy they receive

- 84% are satisfied with their progress toward mental health goals

Things to Consider With Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

There are several challenges that people may face when engaging in cognitive behavioral therapy. Here are a few to consider.

Change Can Be Difficult

Initially, some patients suggest that while they recognize that certain thoughts are not rational or healthy, simply becoming aware of these thoughts does not make it easy to alter them.

CBT Is Very Structured

Cognitive behavioral therapy doesn't focus on underlying, unconscious resistance to change as much as other approaches such as psychoanalytic psychotherapy . Instead, it tends to be more structured, so it may not be suitable for people who may find structure difficult.

You Must Be Willing to Change

For cognitive behavioral therapy to be effective, you must be ready and willing to spend time and effort analyzing your thoughts and feelings. This self-analysis can be difficult, but it is a great way to learn more about how our internal states impact our outward behavior.

Progress Is Often Gradual

In most cases, CBT is a gradual process that helps you take incremental steps toward behavior change . For example, someone with social anxiety might start by simply imagining anxiety-provoking social situations. Next, they may practice conversations with friends, family, and acquaintances. By progressively working toward a larger goal, the process seems less daunting and the goals easier to achieve.

How to Get Started With Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy can be an effective treatment choice for a range of psychological issues. If you or someone you love might benefit from this form of therapy, consider the following steps:

- Consult with your physician and/or check out the directory of certified therapists offered by the National Association of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapists to locate a licensed professional in your area. You can also do a search for "cognitive behavioral therapy near me" to find local therapists who specialize in this type of therapy.

- Consider your personal preferences , including whether face-to-face or online therapy will work best for you.

- Contact your health insurance to see if it covers cognitive behavioral therapy and, if so, how many sessions are covered per year.

- Make an appointment with the therapist you've chosen, noting it on your calendar so you don't forget it or accidentally schedule something else during that time.

- Show up to your first session with an open mind and positive attitude. Be ready to begin to identify the thoughts and behaviors that may be holding you back, and commit to learning the strategies that can propel you forward instead.

What to Expect With Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

If you're new to cognitive behavioral therapy, you may have uncertainties or fears of what to expect. In many ways, the first session begins much like your first appointment with any new healthcare provider.

During the first session, you'll likely spend some time filling out paperwork such as HIPAA forms (privacy forms), insurance information, medical history, current medications, and a therapist-patient service agreement. If you're participating in online therapy, you'll likely fill out these forms online.

Also be prepared to answer questions about what brought you to therapy, your symptoms , and your history—including your childhood, education, career, relationships (family, romantic, friends), and current living situation.

Once the therapist has a better idea of who you are, the challenges you face, and your goals for cognitive behavioral therapy, they can help you increase your awareness of the thoughts and beliefs you have that are unhelpful or unrealistic. Next, strategies are implemented to help you develop healthier thoughts and behavior patterns.

During later sessions, you will discuss how your strategies are working and change the ones that aren't. Your therapist may also suggest cognitive behavioral therapy techniques you can do yourself between sessions, such as journaling to identify negative thoughts or practicing new skills to overcome your anxiety .

If you are having suicidal thoughts, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 for support and assistance from a trained counselor. If you or a loved one are in immediate danger, call 911.

For more mental health resources, see our National Helpline Database .

Hofmann SG, Asnaani A, Vonk IJ, Sawyer AT, Fang A. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses . Cognit Ther Res . 2012;36(5):427-440. doi:10.1007/s10608-012-9476-1

Merriam-Webster. Cognitive behavioral therapy .

Rnic K, Dozois DJ, Martin RA. Cognitive distortions, humor styles, and depression . Eur J Psychol. 2016;12(3):348-62. doi:10.5964/ejop.v12i3.1118

Lazarus AA, Abramovitz A. A multimodal behavioral approach to performance anxiety . J Clin Psychol. 2004;60(8):831-40. doi:10.1002/jclp.20041

Lincoln TM, Riehle M, Pillny M, et al. Using functional analysis as a framework to guide individualized treatment for negative symptoms . Front Psychol. 2017;8:2108. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02108

Ugueto AM, Santucci LC, Krumholz LS, Weisz JR. Problem-solving skills training . Evidence-Based CBT for Anxiety and Depression in Children and Adolescents: A Competencies-Based Approach . 2014. doi:10.1002/9781118500576.ch17

Lindgreen P, Lomborg K, Clausen L. Patient experiences using a self-monitoring app in eating disorder treatment: Qualitative study . JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6(6):e10253. doi:10.2196/10253

Tsitsas GD, Paschali AA. A cognitive-behavior therapy applied to a social anxiety disorder and a specific phobia, case study . Health Psychol Res. 2014;2(3):1603. doi:10.4081/hpr.2014.1603

Kumar V, Sattar Y, Bseiso A, Khan S, Rutkofsky IH. The effectiveness of internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy in treatment of psychiatric disorders . Cureus . 2017;9(8):e1626.

Trauer JM, Qian MY, Doyle JS, Rajaratnam SMW, Cunnington D. Cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia: A systematic review and meta-analysis . Ann Intern Med . 2015;163(3):191. doi:10.7326/M14-2841

Agras WS, Fitzsimmons-craft EE, Wilfley DE. Evolution of cognitive-behavioral therapy for eating disorders . Behav Res Ther . 2017;88:26-36. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2016.09.004

Oud M, De winter L, Vermeulen-smit E, et al. Effectiveness of CBT for children and adolescents with depression: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis . Eur Psychiatry . 2019;57:33-45. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.12.008

Carpenter J, Andrews L, Witcraft S, Powers M, Smits J, Hofmann S. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and related disorders: A meta‐analysis of randomized placebo‐controlled trials . Depress Anxiety . 2018;35(6):502–14. doi:10.1002/da.22728

National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Cognitive-behavioral therapy (alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, methamphetamine, nicotine) .

Gaudiano BA. Cognitive-behavioural therapies: Achievements and challenges . Evid Based Ment Health . 2008;11(1):5-7. doi:10.1136/ebmh.11.1.5

Beck JS. Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond .

Coull G, Morris PG. The clinical effectiveness of CBT-based guided self-help interventions for anxiety and depressive disorders: A systematic review . Psycholog Med . 2011;41(11):2239-2252. doi:10.1017/S0033291711000900

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Problem Solving Treatment (PST)

Problem-Solving Treatment (PST) is a brief form of evidence-based treatment that was originally developed in Great Britain for use by medical professionals in primary care. It is also known as Problem-Solving Treatment – Primary Care (PST-PC). PST has been studied extensively in a wide range of settings and with a variety of providers and patient populations.

PST teaches and empowers patients to solve the here-and-now problems contributing to their depression and helps increase self-efficacy. It typically involves six to ten sessions, depending on the patient’s needs. The first appointment is approximately one hour long because, in addition to the first PST session, it includes an introduction to PST techniques. Subsequent appointments are 30 minutes long.

PST is not indicated as a primary treatment for: substance abuse/dependence, acute primary post-traumatic stress disorder, panic disorder, new onset bipolar disorder, new onset psychosis.

Learn more about how to get trained in PST on this page .

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law