- Find Flashcards

- Why It Works

- Tutors & resellers

- Content partnerships

- Teachers & professors

- Employee training

Brainscape's Knowledge Genome TM

Entrance exams, professional certifications.

- Foreign Languages

- Medical & Nursing

Humanities & Social Studies

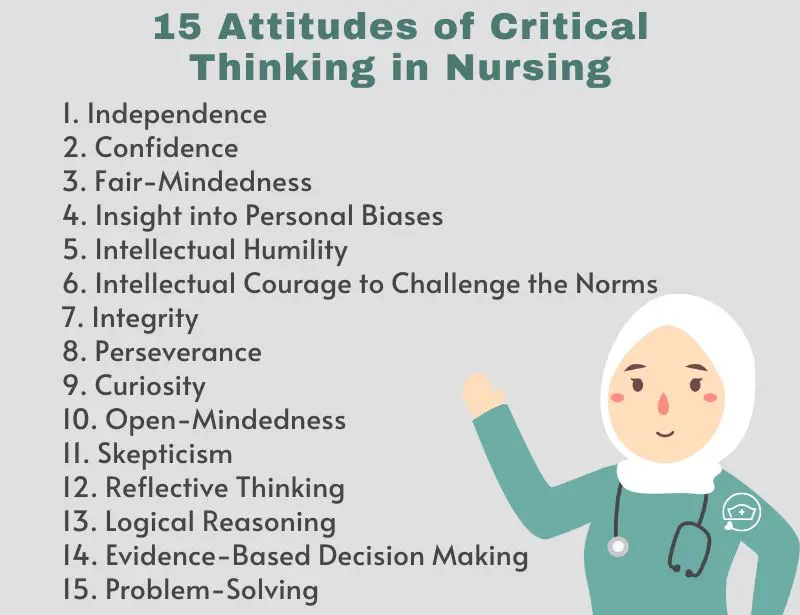

Mathematics, health & fitness, business & finance, technology & engineering, food & beverage, random knowledge, see full index, ch. 15 attitudes for critical thinking flashcards preview, fundamentals of nursing > ch. 15 attitudes for critical thinking > flashcards.

Describe the critical thinking attitude, confidence:

Learn how to introduce yourself to a patient; speak with conviction when you begin a treatment or procedure. Do not lead a patient to think that you are unable to perform care safely. Always be well prepared before performing a nursing activity. Encourage patient to ask questions.

Describe the critical thinking attitude, thinking independently:

Begin to raise important questions about your practice. Read the nursing literature, especially when there are different views on the same subject. Talk with other nurses and share ideas about nursing interventions.

Describe the critical thinking attitude, fairness:

Deal with situations justly. Listen to both sides in any discussion. If a patient or family member complains about a coworker, listen to the story and then speak with the coworker as well. If a staff member labels the patient uncooperative, I seem to care of that patient with openness and a desire to meet that patients needs

Describe the critical thinking attitude, responsibility and authority:

Or, responsibility and accountability. Ask for help if you are uncertain about how to perform a nursing skill. Referred to a policy and procedure manual to review steps of the skill. Report any problems immediately. Follow standards of practice in your care.

Describe the critical thinking attitude, risk-taking:

If your knowledge causes you to question the healthcare providers order, do so. Be willing to recommend alternative approaches to nursing care when colleagues are having little success with patients

Describe the critical thinking attitude, discipline:

Be thorough and whatever you do. Use known scientific and practice-based criteria for activities such as assessment and evaluation. Take time to be thorough and manage your time effectively.

Describe the critical thinking attitude of perseverance:

Because she is an easy answer. If co-workers give you information about a patient and some facts seems to be missing, clarify the information or talk to the patient directly. If problems of the same type continue to occur on a nursing division, bring coworkers together, look for a pattern, and find a solution.

Describe the critical thinking attitude of creativity:

Look for different approaches is interventions are not working for a patient. For example, the patient in pain might need a different positioning or distraction technique. When appropriate, involve the patient’s family in adapting approaches to care methods used at home.

Describe the critical thinking attitude of curiosity:

Always ask why. A clinical signs or symptoms often indicates a variety of problems. Explore and learn more about the patient so as to make appropriate clinical judgments.

Describe the critical thinking attitude of integrity:

Recognize when your opinions conflict with those of the patient; review your position, and decide how best to proceed to reach outcomes that will satisfy everyone. Do not compromise nursing standards or honesty and delivering nurse care.

Describe the critical thinking attitude of humility:

Recognize when you need more information to make a decision. When you are new to the clinical division, ask for an orientation to the area. Ask registered nurses regularly assigned to the area for assistance with approaches to care.

What are the 11 critical thinking attitudes? Box 15-3 p.200

- Thinking independently

- Responsibility and authority

- Risk-taking

- Perseverance

Decks in Fundamentals of Nursing Class (14):

- Ch. 2 Examples Of Healthcare Services (Box 2–1) P. 17

- Ch. 1 (Nursing Today) Key Terms

- Ch. 2 (Health Care Delivery System) Key Terms

- Ch. 15 (Critical Thinking In Nursing Practice) Key Terms

- Nursing Process

- Ch. 15 Attitudes For Critical Thinking

- Ch. 15 Critical Thinking Skills

- Ch. 16 (Nursing Assessment) Objectives

- Ch. 16 Nursing Assessment

- Ch. 17 Nursing Diagnosis Objectives

- Ch. 17 Nursing Diagnosis

- Ch. 39 Hygiene

- Ch. 44 Nutrition

- Corporate Training

- Teachers & Schools

- Android App

- Help Center

- Law Education

- All Subjects A-Z

- All Certified Classes

- Earn Money!

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Acta Inform Med

- v.22(4); 2014 Aug

Critical Thinking: The Development of an Essential Skill for Nursing Students

Ioanna v. papathanasiou.

1 Nursing Department, Technological Educational Institute of Thessaly, Greece

Christos F. Kleisiaris

2 Nursing Department, Technological Educational Institute of Crete, Greece

Evangelos C. Fradelos

3 State Mental Hospital of Attica “Daphne”, Greece

Katerina Kakou

Lambrini kourkouta.

4 Nursing Department, Alexander Technological Educational Institute of Thessaloniki, Greece

Critical thinking is defined as the mental process of actively and skillfully perception, analysis, synthesis and evaluation of collected information through observation, experience and communication that leads to a decision for action. In nursing education there is frequent reference to critical thinking and to the significance that it has in daily clinical nursing practice. Nursing clinical instructors know that students face difficulties in making decisions related to clinical practice. The main critical thinking skills in which nursing students should be exercised during their studies are critical analysis, introductory and concluding justification, valid conclusion, distinguish of facts and opinions, evaluation the credibility of information sources, clarification of concepts and recognition of conditions. Specific behaviors are essentials for enhancing critical thinking. Nursing students in order to learn and apply critical thinking should develop independence of thought, fairness, perspicacity in personal and social level, humility, spiritual courage, integrity, perseverance, self-confidence, interest for research and curiosity. Critical thinking is an essential process for the safe, efficient and skillful nursing practice. The nursing education programs should adopt attitudes that promote critical thinking and mobilize the skills of critical reasoning.

1. INTRODUCTION

Critical thinking is applied by nurses in the process of solving problems of patients and decision-making process with creativity to enhance the effect. It is an essential process for a safe, efficient and skillful nursing intervention. Critical thinking according to Scriven and Paul is the mental active process and subtle perception, analysis, synthesis and evaluation of information collected or derived from observation, experience, reflection, reasoning or the communication leading to conviction for action ( 1 ).

So, nurses must adopt positions that promote critical thinking and refine skills of critical reasoning in order a meaningful assessment of both the previous and the new information and decisions taken daily on hospitalization and use of limited resources, forces you to think and act in cases where there are neither clear answers nor specific procedures and where opposing forces transform decision making in a complex process ( 2 ).

Critical thinking applies to nurses as they have diverse multifaceted knowledge to handle the various situations encountered during their shifts still face constant changes in an environment with constant stress of changing conditions and make important decisions using critical thinking to collect and interpret information that are necessary for making a decision ( 3 ).

Critical thinking, combined with creativity, refine the result as nurses can find specific solutions to specific problems with creativity taking place where traditional interventions are not effective. Even with creativity, nurses generate new ideas quickly, get flexible and natural, create original solutions to problems, act independently and with confidence, even under pressure, and demonstrate originality ( 4 ).

The aim of the study is to present the basic skills of critical thinking, to highlight critical thinking as a essential skill for nursing education and a fundamental skill for decision making in nursing practice. Moreover to indicate the positive effect and relation that critical thinking has on professional outcomes.

2. CRITICAL THINKING SKILLS

Nurses in their efforts to implement critical thinking should develop some methods as well as cognitive skills required in analysis, problem solving and decision making ( 5 ). These skills include critical analysis, introductory and concluding justification, valid conclusion, distinguishing facts and opinions to assess the credibility of sources of information, clarification of concepts, and recognition conditions ( 6 , 7 ).

Critical analysis is applied to a set of questions that relate to the event or concept for the determination of important information and ideas and discarding the unnecessary ones. It is, thus, a set of criteria to rationalize an idea where one must know all the questions but to use the appropriate one in this case ( 8 ).

The Socratic Method, where the question and the answer are sought, is a technique in which one can investigate below the surface, recognize and examine the condition, look for the consequences, investigate the multiple data views and distinguish between what one knows and what he simply believes. This method should be implemented by nurses at the end of their shifts, when reviewing patient history and progress, planning the nursing plan or discussing the treatment of a patient with colleagues ( 9 ).

The Inference and Concluding justification are two other critical thinking skills, where the justification for inductive generalizations formed from a set of data and observations, which when considered together, specific pieces of information constitute a special interpretation ( 10 ). In contrast, the justification is deduced from the general to the specific. According to this, nurse starts from a conceptual framework–for example, the prioritization of needs by Maslow or a context–evident and gives descriptive interpretation of the patient’s condition with respect to this framework. So, the nurse who uses drawing needs categorizes information and defines the problem of the patient based on eradication, nutrition or need protection.

In critical thinking, the nurses still distinguish claims based on facts, conclusions, judgments and opinions. The assessment of the reliability of information is an important stage of critical thinking, where the nurse needs to confirm the accuracy of this information by checking other evidence and informants ( 10 ).

The concepts are ideas and opinions that represent objects in the real world and the importance of them. Each person has developed its own concepts, where they are nested by others, either based on personal experience or study or other activities. For a clear understanding of the situation of the patient, the nurse and the patient should be in agreement with the importance of concepts.

People also live under certain assumptions. Many believe that people generally have a generous nature, while others believe that it is a human tendency to act in its own interest. The nurse must believe that life should be considered as invaluable regardless of the condition of the patient, with the patient often believing that quality of life is more important than duration. Nurse and patient, realizing that they can make choices based on these assumptions, can work together for a common acceptable nursing plan ( 11 ).

3. CRITICAL THINKING ENHANCEMENT BEHAVIORS

The person applying critical thinking works to develop the following attitudes and characteristics independence of thought, fairness, insight into the personal and public level, humble intellect and postpone the crisis, spiritual courage, integrity, perseverance, self-confidence, research interest considerations not only behind the feelings and emotions but also behind the thoughts and curiosity ( 12 ).

Independence of Thought

Individuals who apply critical thinking as they mature acquire knowledge and experiences and examine their beliefs under new evidence. The nurses do not remain to what they were taught in school, but are “open-minded” in terms of different intervention methods technical skills.

Impartiality

Those who apply critical thinking are independent in different ways, based on evidence and not panic or personal and group biases. The nurse takes into account the views of both the younger and older family members.

Perspicacity into Personal and Social Factors

Those who are using critical thinking and accept the possibility that their personal prejudices, social pressures and habits could affect their judgment greatly. So, they try to actively interpret their prejudices whenever they think and decide.

Humble Cerebration and Deferral Crisis

Humble intellect means to have someone aware of the limits of his own knowledge. So, those who apply critical thinking are willing to admit they do not know something and believe that what we all consider rectum cannot always be true, because new evidence may emerge.

Spiritual Courage

The values and beliefs are not always obtained by rationality, meaning opinions that have been researched and proven that are supported by reasons and information. The courage should be true to their new ground in situations where social penalties for incompatibility are strict. In many cases the nurses who supported an attitude according to which if investigations are proved wrong, they are canceled.

Use of critical thinking to mentally intact individuals question their knowledge and beliefs quickly and thoroughly and cause the knowledge of others so that they are willing to admit and appreciate inconsistencies of both their own beliefs and the beliefs of the others.

Perseverance

The perseverance shown by nurses in exploring effective solutions for patient problems and nursing each determination helps to clarify concepts and to distinguish related issues despite the difficulties and failures. Using critical thinking they resist the temptation to find a quick and simple answer to avoid uncomfortable situations such as confusion and frustration.

Confidence in the Justification

According to critical thinking through well motivated reasoning leads to reliable conclusions. Using critical thinking nurses develop both the inductive and the deductive reasoning. The nurse gaining more experience of mental process and improvement, does not hesitate to disagree and be troubled thereby acting as a role model to colleagues, inspiring them to develop critical thinking.

Interesting Thoughts and Feelings for Research

Nurses need to recognize, examine and inspect or modify the emotions involved with critical thinking. So, if they feel anger, guilt and frustration for some event in their work, they should follow some steps: To restrict the operations for a while to avoid hasty conclusions and impulsive decisions, discuss negative feelings with a trusted, consume some of the energy produced by emotion, for example, doing calisthenics or walking, ponder over the situation and determine whether the emotional response is appropriate. After intense feelings abate, the nurse will be able to proceed objectively to necessary conclusions and to take the necessary decisions.

The internal debate, that has constantly in mind that the use of critical thinking is full of questions. So, a research nurse calculates traditions but does not hesitate to challenge them if you do not confirm their validity and reliability.

4. IMPLEMENTATION OF CRITICAL THINKING IN NURSING PRACTICE

In their shifts nurses act effectively without using critical thinking as many decisions are mainly based on habit and have a minimum reflection. Thus, higher critical thinking skills are put into operation, when some new ideas or needs are displayed to take a decision beyond routine. The nursing process is a systematic, rational method of planning and providing specialized nursing ( 13 ). The steps of the nursing process are assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation, evaluation. The health care is setting the priorities of the day to apply critical thinking ( 14 ). Each nurse seeks awareness of reasoning as he/she applies the criteria and considerations and as thinking evolves ( 15 ).

Problem Solving

Problem solving helps to acquire knowledge as nurse obtains information explaining the nature of the problem and recommends possible solutions which evaluate and select the application of the best without rejecting them in a possible appeal of the original. Also, it approaches issues when solving problems that are often used is the empirical method, intuition, research process and the scientific method modified ( 16 ).

Experiential Method

This method is mainly used in home care nursing interventions where they cannot function properly because of the tools and equipment that are incomplete ( 17 ).

Intuition is the perception and understanding of concepts without the conscious use of reasoning. As a problem solving approach, as it is considered by many, is a form of guessing and therefore is characterized as an inappropriate basis for nursing decisions. But others see it as important and legitimate aspect of the crisis gained through knowledge and experience. The clinical experience allows the practitioner to recognize items and standards and approach the right conclusions. Many nurses are sensing the evolution of the patient’s condition which helps them to act sooner although the limited information. Despite the fact that the intuitive method of solving problems is recognized as part of nursing practice, it is not recommended for beginners or students because the cognitive level and the clinical experience is incomplete and does not allow a valid decision ( 16 ).

Research Process / Scientifically Modified Method

The research method is a worded, rational and systematic approach to problem solving. Health professionals working in uncontrolled situations need to implement a modified approach of the scientific method of problem solving. With critical thinking being important in all processes of problem solving, the nurse considers all possible solutions and decides on the choice of the most appropriate solution for each case ( 18 ).

The Decision

The decision is the selection of appropriate actions to fulfill the desired objective through critical thinking. Decisions should be taken when several exclusive options are available or when there is a choice of action or not. The nurse when facing multiple needs of patients, should set priorities and decide the order in which they help their patients. They should therefore: a) examine the advantages and disadvantages of each option, b) implement prioritization needs by Maslow, c) assess what actions can be delegated to others, and d) use any framework implementation priorities. Even nurses make decisions about their personal and professional lives. The successive stages of decision making are the Recognition of Objective or Purpose, Definition of criteria, Calculation Criteria, Exploration of Alternative Solutions, Consideration of Alternative Solutions, Design, Implementation, Evaluation result ( 16 ).

The contribution of critical thinking in decision making

Acquiring critical thinking and opinion is a question of practice. Critical thinking is not a phenomenon and we should all try to achieve some level of critical thinking to solve problems and make decisions successfully ( 19 - 21 ).

It is vital that the alteration of growing research or application of the Socratic Method or other technique since nurses revise the evaluation criteria of thinking and apply their own reasoning. So when they have knowledge of their own reasoning-as they apply critical thinking-they can detect syllogistic errors ( 22 – 26 ).

5. CONCLUSION

In responsible positions nurses should be especially aware of the climate of thought that is implemented and actively create an environment that stimulates and encourages diversity of opinion and research ideas ( 27 ). The nurses will also be applied to investigate the views of people from different cultures, religions, social and economic levels, family structures and different ages. Managing nurses should encourage colleagues to scrutinize the data prior to draw conclusions and to avoid “group thinking” which tends to vary without thinking of the will of the group. Critical thinking is an essential process for the safe, efficient and skillful nursing practice. The nursing education programs should adopt attitudes that promote critical thinking and mobilize the skills of critical reasoning.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: NONE DECLARED.

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 8 min read

Critical Thinking

Developing the right mindset and skills.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

We make hundreds of decisions every day and, whether we realize it or not, we're all critical thinkers.

We use critical thinking each time we weigh up our options, prioritize our responsibilities, or think about the likely effects of our actions. It's a crucial skill that helps us to cut out misinformation and make wise decisions. The trouble is, we're not always very good at it!

In this article, we'll explore the key skills that you need to develop your critical thinking skills, and how to adopt a critical thinking mindset, so that you can make well-informed decisions.

What Is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking is the discipline of rigorously and skillfully using information, experience, observation, and reasoning to guide your decisions, actions, and beliefs. You'll need to actively question every step of your thinking process to do it well.

Collecting, analyzing and evaluating information is an important skill in life, and a highly valued asset in the workplace. People who score highly in critical thinking assessments are also rated by their managers as having good problem-solving skills, creativity, strong decision-making skills, and good overall performance. [1]

Key Critical Thinking Skills

Critical thinkers possess a set of key characteristics which help them to question information and their own thinking. Focus on the following areas to develop your critical thinking skills:

Being willing and able to explore alternative approaches and experimental ideas is crucial. Can you think through "what if" scenarios, create plausible options, and test out your theories? If not, you'll tend to write off ideas and options too soon, so you may miss the best answer to your situation.

To nurture your curiosity, stay up to date with facts and trends. You'll overlook important information if you allow yourself to become "blinkered," so always be open to new information.

But don't stop there! Look for opposing views or evidence to challenge your information, and seek clarification when things are unclear. This will help you to reassess your beliefs and make a well-informed decision later. Read our article, Opening Closed Minds , for more ways to stay receptive.

Logical Thinking

You must be skilled at reasoning and extending logic to come up with plausible options or outcomes.

It's also important to emphasize logic over emotion. Emotion can be motivating but it can also lead you to take hasty and unwise action, so control your emotions and be cautious in your judgments. Know when a conclusion is "fact" and when it is not. "Could-be-true" conclusions are based on assumptions and must be tested further. Read our article, Logical Fallacies , for help with this.

Use creative problem solving to balance cold logic. By thinking outside of the box you can identify new possible outcomes by using pieces of information that you already have.

Self-Awareness

Many of the decisions we make in life are subtly informed by our values and beliefs. These influences are called cognitive biases and it can be difficult to identify them in ourselves because they're often subconscious.

Practicing self-awareness will allow you to reflect on the beliefs you have and the choices you make. You'll then be better equipped to challenge your own thinking and make improved, unbiased decisions.

One particularly useful tool for critical thinking is the Ladder of Inference . It allows you to test and validate your thinking process, rather than jumping to poorly supported conclusions.

Developing a Critical Thinking Mindset

Combine the above skills with the right mindset so that you can make better decisions and adopt more effective courses of action. You can develop your critical thinking mindset by following this process:

Gather Information

First, collect data, opinions and facts on the issue that you need to solve. Draw on what you already know, and turn to new sources of information to help inform your understanding. Consider what gaps there are in your knowledge and seek to fill them. And look for information that challenges your assumptions and beliefs.

Be sure to verify the authority and authenticity of your sources. Not everything you read is true! Use this checklist to ensure that your information is valid:

- Are your information sources trustworthy ? (For example, well-respected authors, trusted colleagues or peers, recognized industry publications, websites, blogs, etc.)

- Is the information you have gathered up to date ?

- Has the information received any direct criticism ?

- Does the information have any errors or inaccuracies ?

- Is there any evidence to support or corroborate the information you have gathered?

- Is the information you have gathered subjective or biased in any way? (For example, is it based on opinion, rather than fact? Is any of the information you have gathered designed to promote a particular service or organization?)

If any information appears to be irrelevant or invalid, don't include it in your decision making. But don't omit information just because you disagree with it, or your final decision will be flawed and bias.

Now observe the information you have gathered, and interpret it. What are the key findings and main takeaways? What does the evidence point to? Start to build one or two possible arguments based on what you have found.

You'll need to look for the details within the mass of information, so use your powers of observation to identify any patterns or similarities. You can then analyze and extend these trends to make sensible predictions about the future.

To help you to sift through the multiple ideas and theories, it can be useful to group and order items according to their characteristics. From here, you can compare and contrast the different items. And once you've determined how similar or different things are from one another, Paired Comparison Analysis can help you to analyze them.

The final step involves challenging the information and rationalizing its arguments.

Apply the laws of reason (induction, deduction, analogy) to judge an argument and determine its merits. To do this, it's essential that you can determine the significance and validity of an argument to put it in the correct perspective. Take a look at our article, Rational Thinking , for more information about how to do this.

Once you have considered all of the arguments and options rationally, you can finally make an informed decision.

Afterward, take time to reflect on what you have learned and what you found challenging. Step back from the detail of your decision or problem, and look at the bigger picture. Record what you've learned from your observations and experience.

Critical thinking involves rigorously and skilfully using information, experience, observation, and reasoning to guide your decisions, actions and beliefs. It's a useful skill in the workplace and in life.

You'll need to be curious and creative to explore alternative possibilities, but rational to apply logic, and self-aware to identify when your beliefs could affect your decisions or actions.

You can demonstrate a high level of critical thinking by validating your information, analyzing its meaning, and finally evaluating the argument.

Critical Thinking Infographic

See Critical Thinking represented in our infographic: An Elementary Guide to Critical Thinking .

You've accessed 1 of your 2 free resources.

Get unlimited access

Discover more content

Book Insights

Overcoming Low Self-Esteem

Melanie Fennell

5 Customer Service Parables

Improve Customer Service With Stories

Add comment

Comments (1)

priyanka ghogare

Team Management

Learn the key aspects of managing a team, from building and developing your team, to working with different types of teams, and troubleshooting common problems.

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Newest Releases

SWOT Analysis

SMART Goals

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

How to stop procrastinating.

Overcoming the Habit of Delaying Important Tasks

What Is Time Management?

Working Smarter to Enhance Productivity

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Boost your team with positive narratives infographic.

Infographic Transcript

Infographic

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

Integrity is one of the most important and oft-cited of virtue terms. It is also perhaps the most puzzling. For example, while it is sometimes used virtually synonymously with ‘moral,’ we also at times distinguish acting morally from acting with integrity. Persons of integrity may in fact act immorally—though they would usually not know they are acting immorally. Thus one may acknowledge a person to have integrity even though that person may hold importantly mistaken moral views.

When used as a virtue term, ‘integrity’ refers to a quality of a person's character; however, there are other uses of the term. One may speak of the integrity of a wilderness region or an ecosystem, a computerized database, a defense system, a work of art, and so on. When it is applied to objects, integrity refers to the wholeness, intactness or purity of a thing—meanings that are sometimes carried over when it is applied to people. A wilderness region has integrity when it has not been corrupted by development or by the side-effects of development, when it remains intact as wilderness. A database maintains its integrity as long as it remains uncorrupted by error; a defense system as long as it is not breached. A musical work might be said to have integrity when its musical structure has a certain completeness that is not intruded upon by uncoordinated, unrelated musical ideas; that is, when it possesses a kind of musical wholeness, intactness and purity.

Integrity is also attributed to various parts or aspects of a person's life. We speak of attributes such as professional, intellectual and artistic integrity. However, the most philosophically important sense of the term ‘integrity’ relates to general character. Philosophers have been particularly concerned to understand what it is for a person to exhibit integrity throughout life. Acting with integrity on some particularly important occasion will, philosophically speaking, always be explained in terms of broader features of a person's character and life. What is it to be a person of integrity? Ordinary discourse about integrity involves two fundamental intuitions: first, that integrity is primarily a formal relation one has to oneself, or between parts or aspects of one's self; and second, that integrity is connected in an important way to acting morally, in other words, there are some substantive or normative constraints on what it is to act with integrity.

Ordinary intuitions about integrity tend to allow both that integrity is a formal relation to the self and that it has something to do with acting morally. How these two intuitions can be incorporated into a consistent theory of integrity is not obvious, and most accounts of integrity tend to focus on one of these intuitions to the detriment of the other. A number of accounts have been advanced, the most important of them being: (i) integrity as the integration of self; (ii) integrity as maintenance of identity; (iii) integrity as standing for something; (iv) integrity as moral purpose; and (v) integrity as a virtue. These accounts are reviewed below. We then examine several issues that have been of central concern to philosophers exploring the concept of integrity: the relations between types of integrity, integrity and moral theory, and integrity and social and political conditions.

1. Integrity as Self-Integration

2. the identity view of integrity, 3. integrity as standing for something, 4. integrity as moral purpose, 5. integrity as a virtue, 6. types of integrity, 7. integrity and moral theory.

- 8. Integrity in Relation to Social and Political Conditions

Bibliography

Other internet resources, related entries.

On the self-integration view of integrity, integrity is a matter of persons integrating various parts of their personality into a harmonious, intact whole. Understood in this way, the integrity of persons is analogous to the integrity of things: integrity is primarily a matter of keeping the self intact and uncorrupted. The self-integration view of integrity makes integrity a formal relation to the self.

What is a formal relation to the self? One answer is that a formal relation can be attributed to a person without evaluating the relation's components. Strength of will is probably a formal relation one has to oneself. Very roughly, we might say that a display of strength of will is a particular relation between a person's intention and corresponding action: it is a matter of acting on an intention given serious obstacles to the action. This is a formal relation to the self in the sense we are after because we don't need to evaluate the appropriateness, value, justice, practical wisdom, and so on, either of the intention or corresponding action in order to identify the whole thing as a case of strength of will. We might think that all displays of strength of will are valuable, so we might have certain pro-attitudes to an action simply because it is an attempt to fulfill an intention in the face of serious obstacles. Yet we don't need to make this evaluation in order to attribute a display of strength of will to someone. All we need to do is inspect the corrspondence of intention and action given the difficulty of acting on the intention. We don't need to evaluate whether the intention is directed at anything worthwhile, for example. Strength of will can be displayed by the deluded and the foolishly stubborn. Self-integration is a formal relation of this kind. In attributing self-integration to a person we are making no evaluative judgement of the states that are integrated within the person.

One instructive attempt to describe the fully integrated self is Harry Frankfurt's. (Frankfurt 1987, pp. 33-34) Frankfurt does not explicitly address himself to the problem of defining integrity, nonetheless he does describe an important and influential account of self-integration. According to Frankfurt, desires and volitions (acts of will) are arranged in a hierarchy. First-order desires are desires for various goods; second-order desires are desires that one desire certain goods, or that one act on one first-order desire rather than another. Similarly, one may will a particular action (first-order volition) or one may will that one's first order volitions are of a particular sort (second-order volition). Second-order desires and volitions pave the way for third-order desires and volitions, and so on. According to Frankfurt, wholly integrated persons bring these various levels of volition and desire into harmony and fully identify with them at the highest level. There are various ideas as to what it means to fully identify with higher-level desires and volitions. However, such identification appears to involve knowing them; not deceiving oneself about them; and acting on them (usually).

A person is subject to many conflicting desires. If one simply acted at each moment out of the strongest current desire, with no deliberation or discrimination between more or less worthwhile desires, then one clearly acts without integrity. Frankfurt calls such a person a ‘wanton’ (Frankfurt 1971). Integrity thus requires that one discriminate between first-order desires. One may do this by endorsing certain first-order desires and ‘outlawing’ others. For instance, one may endorse a desire to study and ‘outlaw’ a desire to party, and do so by reference to a higher order desire ranking success over fun. Second-order desires may conflict. One may value success over fun, but also both fear that a ruthless pursuit of success will make one boring and value being fun over being boring. Fully integrated persons will not fall victim to such conflict; they will either avoid it altogether (if they can) or resolve the conflict in some way. Resolution of self-conflict may be achieved by appeal to yet higher level desires or volitions, or by deciding to endorse one set of desires and outlawing others. At some point the full integration of one's self will require that one decide upon a certain structure of higher level desires and order one's lower level desires and volitions in light of it. As Frankfurt puts it, when a person unreservedly decides to endorse a particular desire:

the person no longer holds himself at all apart from the desire to which he has committed himself. It is no longer unsettled or uncertain whether the object of that desire—that is, what he wants—is what he really wants: The decision determines what the person really wants by making the desires upon which he decides fully his own. To this extent the person, in making a decision by which he identifies with a desire, constitutes himself . (Frankfurt 1987, p. 38)

When agents thus constitute themselves without ambivalence (that is, unresolved desire for a thing and against it) or inconsistency (that is, unresolved desire for incompatible things), then the agent has what Frankfurt calls wholeheartedness. On one way of developing the integrated-self view of integrity, wholeheartedness is equated with integrity. It should be noted that self-conflict is not limited to desire. Conflict also ranges over commitments, principles, values, and wishes. Furthermore, all of these things—desires, commitments, values, and so on—are in flux. They change over time so that achieving the kind of ‘wholeheartedness’ that Frankfurt describes is a never-ending process and task. Self-knowledge is crucial to this process in so far as one must know what one's values, for example, are if one is to order them.

Frankfurt's account illustrates one way of describing the fully-integrated self. (See Taylor 1981 for a different approach.) The key question, however, is whether the idea of a fully-integrated self adequately captures the quality we ascribe when we say of someone that they are a person of integrity. There have been a number of criticisms of the integrated-self view of integrity. First, it places only formal limits on the kind of person who may be said to have integrity. People of integrity, however, are plausibly thought to be generally honest and genuine in their dealings with others. (See Halfon 1989, pp. 7-8.) Imagine a person who sells used-cars for a living and is wholeheartedly dedicated to selling cars for as much money as possible. Such a person will be prepared to blatantly lie in order to set up a deal. The person may well be perfectly integrated in Frankfurt's sense, but we should feel no temptation at all to describe them as having exemplary integrity.

Second, a person of integrity is plausibly said to make reasonable judgments about the relative importance of various desires and commitments. Yet, again, the self-integration view places only formal limits on the kind of desires that constitute a self. (See McFall 1987, pp. 9-11, Calhoun 1995, pp. 237-38). As McFall notes, one cannot say with a straight face something like: ‘Harold demonstrates great integrity in his single-minded pursuit of approval.’ (McFall 1987, p. 9; we discuss McFall's views more fully in Section 4, below.) If integrity is nothing more than the perfect integration of self, however, it is hard to see how one can automatically deny Harold's integrity.

Third, on some accounts, the fully and perfectly integrated person is not able to experience genuine temptation. Temptation requires that the full force of an ‘outlaw’ desire be experienced, but successful integration of the self may mean that such desires are fully subordinated to wholeheartedly endorsed desires and this may preclude an agent fully experiencing them. (See Taylor 1981, p. 151 for an example of a view like this.) That a person experiences, and overcomes, temptation would count against their integrity on such a view. One might think, however, that a capacity to overcome temptation and display strength of character is in fact a sign of a person's integrity, not its lack. (Halfon 1989, pp. 44-7 urges this criticism.)

Fourth, Cheshire Calhoun argues that agents may find themselves in situations in which wholeheartedness tends to undermine their integrity rather than constitute it. (Calhoun 1995, pp. 238-41. Analogously, Victoria Davion 1991, pp. 180-192 argues that a person may change radically and yet maintain integrity.) In the midst of a complex and multifaceted life one may have compelling reasons to avoid neatly resolving incompatible desires. The cost of the resolution of all self-conflict may be a withdrawal from aspects of life that make genuine claims upon us. Resolving self-conflict at the expense of fully engaging with different parts of one's life does not seem to contribute to one's integrity. It seems rather like the sort of cop-out that undermines integrity. (One should not confuse integrity with neatness .)

A related approach to integrity is to think of it primarily in terms of a person's holding steadfastly true to their commitments, rather than ordering and endorsing desires. ‘Commitment’ is used as a broad umbrella term covering many different kinds of intentions, promises, convictions and relationships of trust and expectation. One may be, and usually is, committed in many different ways to many different kinds of thing: people, institutions, traditions, causes, ideals, principles, projects, and so on. Commitments can be explicitly, self-consciously, publicly entered into or implicit, unself-conscious and private. Some are relatively superficial and unimportant, like casual support of a sporting team; others are very deep, like the commitment implicit in genuine love or friendship.

Because we find ourselves with so many commitments, of so many different kinds, and because commitments inevitably clash and change over time, it will not do to define integrity merely in terms of remaining steadfastly true to one's commitments. It matters which commitments we expect a person of integrity to remain true to. Philosophers have developed different accounts of integrity in response to this need to specify the kind of commitments that are centrally important to a person's integrity.

One option here is to define integrity in terms of the commitments that people identify with most deeply, as constituting what they consider their life is fundamentally about. Commitments of this kind are called ‘identity-conferring commitments’ or sometimes ‘ground projects’. This view of integrity, the identity view, is associated most closely with Bernard Williams. It is implicit in his discussion of integrity and utilitarianism (Williams 1973; we examine this discussion below) and also features in his criticism of Kantian moral theory (1981b). The idea is that for people to abandon an identity-conferring commitment is for them to lose grip on what gives their life its identity, or individual character. An identity-conferring commitment, according to Williams, is ‘the condition of my existence, in the sense that unless I am propelled forward by the conatus of desire, project and interest, it is unclear why I should go on at all.’ (Williams 1981b, p. 12).

One apparent consequence of defining integrity as maintenance of identity-conferring commitments is that integrity cannot really be a virtue. This is Williams's view. He argues that integrity is not related to motivation as virtues are. A virtue either motivates a person to act in desirable ways (as benevolence moves a person to act for another's good), or it enables a person to act in desirable ways (as courage enables a person to act well). If integrity is no more than maintenance of identity, however, it can play neither of these roles. On the identity view of integrity, to act with integrity is just to act in a way that accurately reflects your sense of who you are; to act from motives, interests and commitments that are most deeply your own. (Williams 1981a, p. 49) A further consequence of this view of integrity as maintenance of identity-conferring commitments is that there appears to be no normative constraints either on what such commitments may be, or on what the person of integrity can do in the pursuit of these commitments. People of integrity can do horrific things and maintain their integrity so long as they are acting in accordance with their core commitments.

A number of criticisms of the identity view of integrity have been made. First, integrity is usually regarded as something worth striving for and the identity account of integrity fails to make sense of this. (See Cox, La Caze, Levine 1999.) It disconnects integrity from the prevalent view that it is a virtue of some kind and generally praiseworthy. Second, the identity theory of integrity ties integrity to commitments with which an agent identifies, but acts of identification can be ill-informed, superficial and foolish. People may, through ignorance or self-deception, fail to understand or properly acknowledge the source of their deepest commitments and convictions and we are unlikely to attribute integrity to people who hold true to a false and unrealistic picture of themselves. (On the other hand, this view of integrity as maintenance of identify-conferring commitments, recognizes the relevance of self-knowledge to acting with integrity. If people fail to act on their core commitments, through self-deception, weakness of will, cowardice, or even ignorance, then to this extent they may be said to lack integrity.)

Third, on the identity view of integrity, a person's integrity is only at issue when their deepest, most characteristic, or core convictions and aspirations are brought into play. However, we expect persons of integrity to behave with integrity in many different contexts, not only those of central importance to them. (See Calhoun 1995, p. 245.)

Fourth, as noted above, the identity view of integrity places only formal conditions upon the kind of person that might be said to possess integrity. The identity view of integrity shares this feature with the self-integration view of integrity and similar criticism can be made of it on this ground. It seems plausible to observe certain substantive limits on the kinds of commitments had by a person of integrity.

The self-integration and identity views of integrity see it as primarily a personal virtue: a quality defined by a person's care of the self. Cheshire Calhoun argues that integrity is primarily a social virtue, one that is defined by a person's relations to others (Calhoun 1995). The social character of integrity is, Calhoun claims, a matter of a person's proper regard for their own best judgement. Persons of integrity do not just act consistently with their endorsements, they stand for something: they stand up for their best judgment within a community of people trying to discover what in life is worth doing. As she puts it:

Persons of integrity treat their own endorsements as ones that matter, or ought to matter, to fellow deliberators. Absent a special sort of story, lying about one's views, concealing them, recanting them under pressure, selling them out for rewards or to avoid penalties, and pandering to what one regards as the bad views of others, all indicate a failure to regard one's own judgment as one that should matter to others. (Calhoun 1995 p. 258)

On Calhoun's view, integrity is a matter of having proper regard for one's role in a community process of deliberation over what is valuable and what is worth doing. This, she claims, entails not only that one stand up, unhypocritically, for one's best judgment, but also that one have proper respect for the judgment of others.

Calhoun's account of integrity promises to explain why it is that the fanatic lacks integrity. It seems intuitively very plausible to distinguish between fanatical zeal and integrity, but the self-integration and identity views of integrity threaten to make the fanatic a paradigm case of a person of integrity. Fanatics integrate desires and volitions of various orders in an intimidatingly coherent package; they remain steadfastly true to their deepest commitments like no others. On Calhoun's view of integrity, however, we can locate a distinction between integrity and fanaticism. Fanatics lack one very important quality that, on Calhoun's view, is centrally important to integrity: they lack proper respect for the deliberations of others. What is not clear in Calhoun's account, and is in fact very hard to get clear on in any case, is what the proper respect for other's views in the end amounts to. Exemplary figures of integrity often stand by their judgment in the face of enormous pressure to recant. How, then, is one to understand the difference between standing up for one's views under great pressure and fanatically standing by them? Calhoun's claim that the fanatic lacks integrity because they fail to properly respect the social character of judgement and deliberation sounds right, but most of the work is done by the idea of ‘proper respect’—and it is not clear in the end what this comes to.

Calhoun's account of integrity places no material constraints on the kinds of commitments that a person of integrity may endorse. It does not seem necessary on her view that a person of integrity has a special concern with acting morally. Although they have a special concern to understand what in life is worth doing, the person of integrity is not constrained to give moral, other-regarding answers to this question. By contrast, the following account of integrity is explicitly concerned with attitudes towards morality.

Another way of thinking about integrity places moral constraints upon the kinds of commitment to which a person of integrity must remain true. There are several ways of doing this. Elizabeth Ashford argues for a virtue she calls ‘objective integrity’. Objective integrity requires that agents have a sure grasp of their real moral obligations. (Ashford 2000, p. 246) A person of integrity cannot, therefore, be morally mistaken. Understood in this way, one only properly ascribes integrity to a person with whom one finds oneself completely in moral agreement. This concept of integrity does not, however, closely match ordinary use of the term. The point of attributing integrity to another is not to signal unambiguous moral agreement. It is often to ameliorate criticism of another's moral judgment. For example, we may disagree strongly with the Pope's views of the role of women in the Church, take this to be a significant moral criticism of him, and yet admit that he is a man of integrity. In such a case it is largely the point of attributing integrity to open a space for substantial moral disagreement without launching a wholesale attack upon another's moral character.

Mark Halfon offers a different way of defining integrity in terms of moral purpose. Halfon describes integrity in terms of a person's dedication to the pursuit of a moral life and their intellectual responsibility in seeking to understand the demands of such a life. He writes that persons of integrity:

…embrace a moral point of view that urges them to be conceptually clear, logically consistent, apprised of relevant empirical evidence, and careful about acknowledging as well as weighing relevant moral considerations. Persons of integrity impose these restrictions on themselves since they are concerned, not simply with taking any moral position, but with pursuing a commitment to do what is best. (Halfon 1989, p. 37.)

Halfon's view allows that integrity is not necessarily ‘objective’, as Ashford claims, and is similar in a number of respects to Calhoun's. Both see integrity as centrally concerned with deliberation about how to live. However, Halfon conceives this task in more narrowly moral terms and ties integrity to personal intellectual virtues exercised in pursuit of a morally good life. Halfon speaks of a person confronting ‘all relevant moral considerations’, but this turns out to be quite a formal constraint. What counts as a relevant moral consideration, on Halfon's view, depends upon the moral point of view of the agent. Persons of integrity may thus be responsible for acts others would regard as grossly immoral. What is important is that they act with moral purpose and display intellectual integrity in moral deliberation. This leads Halfon to admit that, on his conception of integrity, it is possible for a Nazi bent on genocide of the entire Jewish people to be a person of moral integrity. Halfon thinks it possible, but not at all likely. (Halfon 1989, pp. 134-36)

Other philosophers object to this consequence. If the genocidal Nazi is a possible object of ascriptions of moral integrity, then we can properly ascribe integrity to people whose moral viewpoint is bizarrely remote from any we find intelligible or defensible. (See McFall 1987 and Cox, La Caze and Levine 2003, pp. 56-68. Putnam 1996 draws on the work of Carol Gilligan 1982 to suggest a different way of overcoming the problem of the Nazi of integrity.) Moral constraints upon attributions of integrity need not take the form of Ashford's ‘moralized’ view or Halfon's more limited formal view. One might say instead that attributions of integrity involve the judgment that an agent acts from a moral point of view those attributing integrity find intelligible and defensible (though not necessarily right) —and that this formal constraint does have substantive implications. It prohibits attributing integrity to, for example, those who advocate genocide, or deny the moral standing of people on, for example, sex-based or racial grounds. There are things which a person of integrity cannot do. The Nazis and other perpetrators of great evil were either committed to what they were doing, in which case they were profoundly immoral (or not moral agents at all) and lacked integrity; or else they lacked integrity because they were self-deceived or dissembling and never actually had the Nazi commitments they claimed to have. Judgments of integrity would thus involve judgment about the reasonableness of others' moral points of view, rather than the absolute correctness of their view (Ashford) or the intellectual responsibility with which they generally approach the task of thinking about moral questions (Halfon).

McFall (1987) contains an interesting discussion of the nature of the constraints on proper attributions of integrity. She asks ‘Are there no constraints on the content of the principles or commitments a person of integrity may hold?’ and then invites us to consider the following statements. (McFall 1987, p. 9)

- Sally is a person of principle: pleasure.

- Harold demonstrates great integrity in his single-minded pursuit of approval.

- John was a man of uncommon integrity. He let nothing, not friendship, not justice, not truth stand in the way of his amassment of wealth.

McFall holds that the fact that ‘none of these claims can be made with a straight face suggests that integrity is inconsistent with such principles.’ (McFall 1987, p. 9) The question, however, is whether this is down to the formal constraints or substantive constraints; that is, whether attributions of integrity are constrained by the content of principles a person maintains, or by way certain kinds of principle fail to meet formal constraints on the way persons of integrity holds to their principles. McFall appears to suggest the latter interpretation.

In providing reasons for our dismissal of [i] to [iii] she says (1987, 9-10)

A person of integrity is willing to bear the consequences of her convictions, even when this is difficult … A person whose only principle is ‘Seek my own pleasure’ is not a candidate for integrity because there is no possibility of conflict—between pleasure and principle—in which integrity could be lost. Where there is no possibility of its loss, integrity cannot exist. Similarly in the case of the approval seeker. The single-minded pursuit of approval is inconsistent with integrity … A commitment to spinelessness does not vitiate its spinelessness—another of integrity's contraries. The same may be said for the ruthless seeker of wealth. A person whose only aim is to increase his bank balance is a person for whom nothing is ruled out: duplicity, theft, murder. Expedience is contrasted to a life of principle, so an ascription of integrity is out of place. Like the pleasure seeker and the approval seeker, he lacks a ‘core,’ the kind of commitments that give a person character and that make a loss of integrity possible. In order to sell one's soul, one must have something to sell.

This is an argument that evokes formal incompatibility between particular principles or goals and the proper attribution of integrity. The argument is not conclusive, however. Seeking pleasure, approval or wealth, is not always easy and it seems possible that conflict could arise, for example, between determinations to pursue higher or lower pleasures, long-term pleasures or immediate gratifications. Perhaps McFall identifies too readily certain ways of having a bad character with what it is to lack character entirely. The ruthless seeker of wealth seems to have a ‘core,’—albeit a nasty one—along with a set of principles of a sort and a set of actions that are ruled out on principle. In ruling out these kinds of principle or goal in attributions of integrity, we appear to be making substantive claims about the content of a person of integrity's principles or goals.

McFall is surely right in claiming that the people she describes cannot, under her descriptions, be persons of integrity; the question remains as to how to distinguish such people from those we would claim do have integrity, even though their principles are very different than our own. Is there a limit as to how different their principles and commitments can be, or in what ways they can be different, and still maintain their integrity? McFall does not specify ‘core’ commitments necessary to a person's integrity, but she does introduce what appears to be a substantive constraint upon attributions of integrity. She says (1987, p. 11)

When we grant integrity to a person we need not approve of his or her principles or commitments, but we must at least recognize them as ones a reasonable person might take to be of great importance and ones that a reasonable person might be tempted to sacrifice to some lesser yet still recognizable goods. It may not be possible to spell out these conditions without circularity, but that this is what underlies our judgments of integrity seems clear enough. Integrity is a personal virtue granted with social strings attached. By definition, it precludes ‘expediency, artificiality, or shallowness of any kind.’ [See Webster's Third New international Dictionary, ‘integrity.’] The pleasure seeker is guilty of shallowness, the approval seeker of artificiality, and the profit seeker of expedience of the worst sort.

According to McFall, then, we judge people to be of integrity only if they have commitments which a reasonable person could accept as important. This turns out to be a morally substantive constraint. McFall says (1987, p. 11), ‘Whether we grant or deny personal integrity, then, seems to depend on our own conceptions of what is important. And since most of our conceptions are informed if not dominated by moral conceptions of the good, it is natural that this should be reflected in our judgments of personal integrity.’ To say that judgment of another's integrity depends on our own conceptions of what is important, moral, and good implies substantive constraints on what a person may do and still be judged to have integrity. It also consistent with the view that there are constraints on the principles and commitments of a person of integrity per se . If there are objective moral constraints on adequate conceptions of the good, for example, then on the view McFall articulates there will also be objective moral constraints on the possession of integrity.

McFall thus appears to defend the existence of substantive constraints on integrity. However, she also draws a distinction between personal and moral integrity. (McFall 1987, p. 14) On her view, a person who, in acting on some morally deficient principle, does morally abhorrent things may have personal integrity even if not moral integrity. McFall gives the example of a utilitarian lover of literature who is willing to stop people burning books by killing them. She says of the utilitarian killer (1987, p. 14), ‘Although we may find his actions morally abhorrent, we may still be inclined to grant him the virtue of personal integrity. We would not, however, hold him up as a paragon of moral integrity.’ It is difficult to reconcile McFall's account of the distinction between moral and personal integrity with her more general characterization of the concept of integrity. She appears here to be drawing the distinction between moral integrity and personal integrity in terms of the reasonableness of a person's moral beliefs. The utilitarian killer exhibits personal integrity because he sincerely believes himself to be acting rightly, but he lacks moral integrity because of the grossness of his moral error and thus the unreasonableness of his moral judgment.

However, McFall also points out that integrity requires that one hold principles or commitments that a reasonable person might take to be of great importance. It is hard to see how a reasonable person could take the importance of books to be sufficiently great to justify murder. Where McFall talks of judgments of importance, it is natural to interpret her as referring to judgments of value. But if this is so, her distinction between personal and moral integrity appears to collapse. Personal integrity applied to an unambiguously moral predicament just is moral integrity. The distinction between personal and moral integrity, it seems, is better drawn in terms of the kinds of commitments or kinds of activity that are in frame. Personal integrity would then refer to non-moral aspects of a person's life (if there are any); moral integrity would refer to aspects of a person's life that have clear moral significance. It is unclear, however, whether this way of distinguishing between personal and moral integrity captures ordinary use of the term ‘personal integrity’. ‘Personal integrity’ appears to be a term used more or less synonymously with ‘integrity’. Nonetheless, distinctions between moral integrity, non-moral integrity, and overall integrity, i.e. integrity as a general cast of character, do seem well motivated and relatively clear. And if we accept the compartmentalization of a person's life in this way, then attempts to define integrity as moral purpose would be better described as attempts to define moral integrity.

Defining the overall integrity of character in terms of moral purpose has the advantage of capturing intuitions of the moral seriousness of questions of integrity. However, the approach appears too narrow. Halfon's identification of integrity and moral integrity appears to leave out important personal aspects of integrity, aspects better captured by the other views of integrity we have examined. Integrity does not seem to be exclusively a matter of how people approach plainly moral concerns. Other matters like love, friendship and personal projects appear highly relevant to judgments of integrity. Imagine a person who sets great store in writing a novel, but who postpones the writing of it for years on one excuse or another and then abandons the idea of novel-writing after one difficult experience with a first chapter. We would think this person's integrity diminished by their failure to make a serious attempt to see the project through, yet the writing of a novel need not be a moral project.

All of the accounts of integrity we have examined have a certain intuitive appeal and capture some important feature of the concept of integrity. There is, however, no philosophical consensus on the best account. It may be that the concept of integrity is a cluster concept, tying together different overlapping qualities of character under the one term. In Cox, La Caze and Levine 2003, we argue that integrity is a virtue, but not one that is reducible to the workings of a single moral capacity (in the way that, say, courage is) or the wholehearted pursuit of an identifiable moral end (in the way that, say, benevolence is). We take ‘integrity’ to be a complex and thick virtue term. One gains a fair grasp of the variety of ways in which people use the term ‘integrity’ by examining conditions commonly accepted to defeat or diminish a person's integrity. Integrity stands as a mean to various excesses. On the one side we have character traits and ways of behaving and thinking that tend to maintain the status quo even where acting with integrity demands a change. These are things like arrogance, dogmatism, fanaticism, monomania, preciousness, sanctimoniousness, and rigidity. These are all traits that can defeat integrity in so far as they undermine and suppress attempts by an individual to critically assess and balance their desires, commitments, wishes, changing goals and other factors. Thus, refusing to acknowledge that circumstance in a marriage, or one's passionate desire to write a novel, have dramatically changed (for whatever reasons) may indicate a lack of integrity—a giving in to cowardice for example, and a refusal to acknowledge new or overriding commitments. These same factors can defeat integrity, or an aspect of one's integrity, whether one decides to stay with a marriage or abandon it. In one case staying may indicate a lack of integrity, while in a different case, abandoning the marriage would indicate such a lack.

On the other side, a different set of characteristics undermine integrity. These do not undermine the status quo as much as they make it impossible to discern stable features in one's life, and in one's relations to others, that are necessary if one is to act with integrity. Here we have capriciousness, wantonness, triviality, disintegration, weakness of will, self deception, self-ignorance, mendacity, hypocrisy, indifference. Although the second of these lists dominates contemporary reflection on the nature of integrity, the first also represents, in our view, an ever present threat to our integrity. The person of integrity lives in a fragile balance between every one of these all-too-human traits. (Cox, La Caze, Levine 2003, p. 41). It is not that integrity stands as a mean between the vices that are represented in these two lists. Rather, the person of integrity will find a mean between the excesses of each one of these vices, or traits or practices that can undermine—that do undermine—integrity. Some people will be more prone to a certain set of practices or character traits that undermine integrity than others. The defeaters of integrity are person-relative, and may even be situation-relative.

This account of integrity makes it appear that integrity is much more difficult to achieve than is often thought. It makes integrity a quality of character that one may have to a greater or lesser extent, in certain ways but not others, and in certain aspects or areas of one's life but not others. Having integrity is not on this view an all or nothing thing. To say a person has integrity is to make an “all things considered” judgment: something that we may say of people if we know—and even if they know—that in certain ways and about certain things, they lack integrity.

A conception of integrity as a virtue—either developed along the lines described above or along different lines—is compatible with the existence of constraints on the content of the norms the person of integrity is committed to. Profound moral failure may be an independent defeater of integrity, just as hypocrisy, fanaticism and the like are defeaters of integrity. One might judge as internal to our conception of the virtue the idea that integrity is incompatible with major failures of moral imagination or moral courage, or with the maintenance of wholly unreasonable moral principles or opinions. On such a view, the Nazi could not, all things considered, be a regarded as person of integrity. The Nazi may be self-deceiver and a liar (which is highly probable), but even if he is not, his principles and his actions are not rationally defensible under any coherent moral view. And this latter fact may by itself justify the judgment that the Nazi lacks the virtue of integrity.

References to different types of integrity, such as intellectual and artistic integrity, abound in the philosophical literature on integrity and everyday discourse. Because integrity involves managing various commitments and values, one might conjecture that such types of integrity are simply manifestations of a person's overall integrity, or of their personal integrity. However, there are many people who we are inclined to say have intellectual but not personal integrity—or who have more of the former than the latter. If there is a radical disjunction between the type of integrity which is demanded in one sphere of life and another, integrity overall, or personal integrity, may be undermined, or at least profoundly challenged. There may, for example, be conflict between types of integrity, such as between intellectual and moral integrity. (See Code 1983, pp. 268-282; Kekes 1983, pp. 512-516.)

Is integrity in one area of life likely to flow over into others? This is possible, in that the kind of reflection and self-assessment which goes into maintaining integrity in one sphere of life may help people to reflect similarly in other spheres. However, given human beings' capacity and need for compartmentalization, or psychologically separating out different parts of their lives, this effect will not necessarily occur. The relationship between different types of integrity and moral and personal integrity needs to be carefully charted. Is integrity a zero-sum game, so that for example, the more artistic integrity a person has, the less she has in personal life? This does not seem necessarily to be the case. At the same time, a lack of integrity in one aspect of life does not necessarily mean there will be a lack in other aspects of life. Presumably, a person could lack personal integrity, but still have integrity in a number of restricted areas of life, such as in intellectual and artistic pursuits.

A related question is how different types of integrity are associated with moral integrity. Stan Godlovitch (1993, p. 580) says that professional integrity, for example, is weaker than moral integrity, and is more like etiquette. For him (1993, p. 573), integrity ‘trades between the norms of unity and honesty’. More specifically, Godlovitch (1993, p. 580) argues that the responsibilities of performers, for example, are quasi-moral; they are not truly moral because they are internal to the profession. However, it seems plausible to maintain that professional integrity is better understood as an important contribution to the living of a moral life. Professional integrity is specific to the sphere of a profession, but not entirely independent of morality.

One can also ask how types of integrity are distinguished from each other. Halfon (1989, p. 55) argues that we distinguish between types of integrity in terms of commitments to specific kinds of ends, principles and ideals. However, not every end creates a distinct type of integrity. Trivial ends, like train-spotting, do not introduce a new species of integrity. To count as being a type of integrity, the sphere of action and commitment in question should be a complex and valuable human pursuit that has distinct ways in which integrity is demonstrated. Robust examples are intellectual integrity and artistic integrity. On this way of looking at the matter, personal integrity and various specific types of integrity tend to be run together. Integrity is seen as the one virtue: essentially the same virtue expected of one's life partner, a friend, an employee, a priest, a teacher, or a politician. (See Benjamin, 1990; Calhoun, 1995; Halfon, 1989; and Grant, 1997.) Professional integrity then becomes a matter of the extent to which a person displays personal integrity in professional life. Halfon (1989, p. 53), for example, argues that types of integrity may overlap, ‘So a person who is an artist by profession may come to possess professional and artistic integrity in virtue of performing one and the same action or fulfilling one and the same commitment’.

There are, however, good reasons to resist this running together of various types of integrity. In the first place, our legitimate expectations of people must be sensitive to the roles we have tacitly or explicitly agreed that they perform. If we expect people to act with integrity in a certain professional context, then our judgment of them should be based on an understanding of this context: its special duties, obligations, rights, competencies, and so on. What it is to display integrity in one profession need not, therefore, carry over to other professions; and the difference between acting with integrity in one context may not share a common currency with what it is to act with integrity in another context. It seems that the concept of integrity cannot be demarcated into types without specific characterization of the kinds of challenges and hazards encountered in the relevant field of action.

Consider the example of intellectual integrity. The term ‘intellectual integrity’ is ambiguous between integrity of the intellect and the integrity of the intellectual. While it should, in general, be construed broadly, as integrity of the intellect, and thus applicable to anyone who thinks, here we will concentrate on the integrity of the intellectual, or integrity as the academic's virtue, as Susan Haack puts it. (1976, p. 59) Intellectuals may differ in the extent to which they exemplify intellectual virtues such as honesty, impartiality, and openness to the views of others. Intellectual integrity may then be thought of as the over-arching virtue that enables and enhances these individual virtues by maintaining a proper balance between them.

Halfon (1989, p. 54) argues that Socrates had a commitment to the pursuit of truth and knowledge, and he demonstrated his intellectual integrity in the face of attacks on it. Socrates may be an outstanding example of a person of intellectual integrity; nevertheless, there is more to intellectual integrity than having a commitment to truth and knowledge. Intellectual integrity is often characterized as a kind of ‘openness’— an openness to criticism and to the ideas of others. However, if one is too open, one could absorb too many influences to be able to properly pursue any line of thought. So an adequate account of intellectual integrity must incorporate conflicting claims: that one must be open to new ideas but not be overwhelmed by them. An account of intellectual integrity should recognize other sources of conflict and temptations that impede intellectual integrity, such as the temptations offered by the commercialization of research, self-deception about the nature of one's work, and the conflict between the free pursuit of ideas and responsibility to others.