Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples

What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples

Published on August 2, 2022 by Bas Swaen and Tegan George. Revised on March 18, 2024.

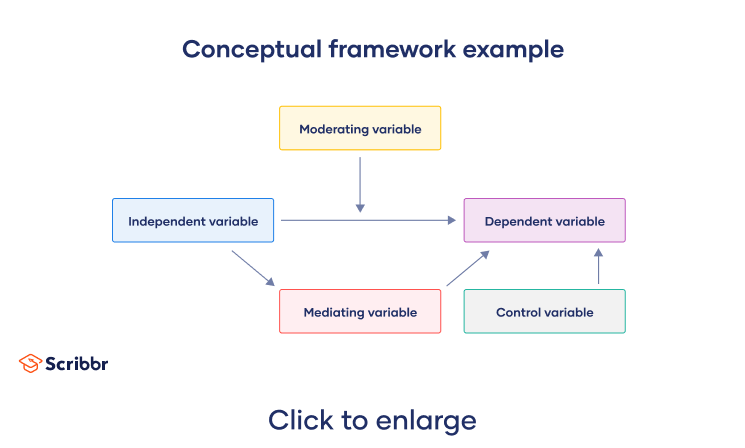

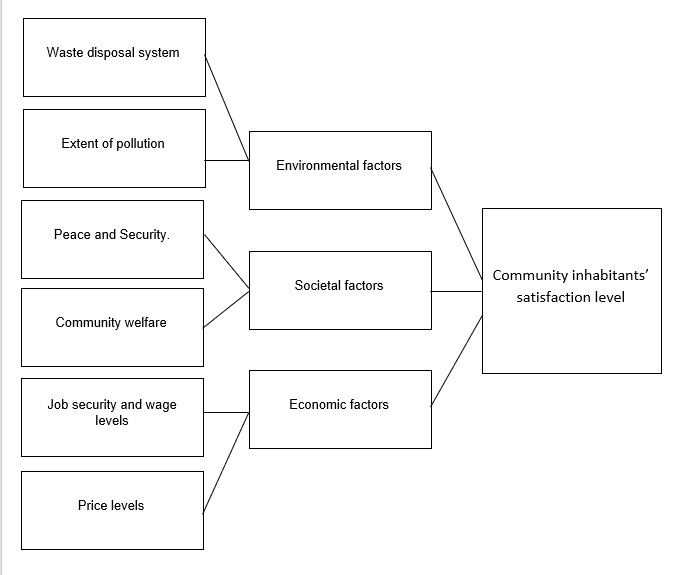

A conceptual framework illustrates the expected relationship between your variables. It defines the relevant objectives for your research process and maps out how they come together to draw coherent conclusions.

Keep reading for a step-by-step guide to help you construct your own conceptual framework.

Table of contents

Developing a conceptual framework in research, step 1: choose your research question, step 2: select your independent and dependent variables, step 3: visualize your cause-and-effect relationship, step 4: identify other influencing variables, frequently asked questions about conceptual models.

A conceptual framework is a representation of the relationship you expect to see between your variables, or the characteristics or properties that you want to study.

Conceptual frameworks can be written or visual and are generally developed based on a literature review of existing studies about your topic.

Your research question guides your work by determining exactly what you want to find out, giving your research process a clear focus.

However, before you start collecting your data, consider constructing a conceptual framework. This will help you map out which variables you will measure and how you expect them to relate to one another.

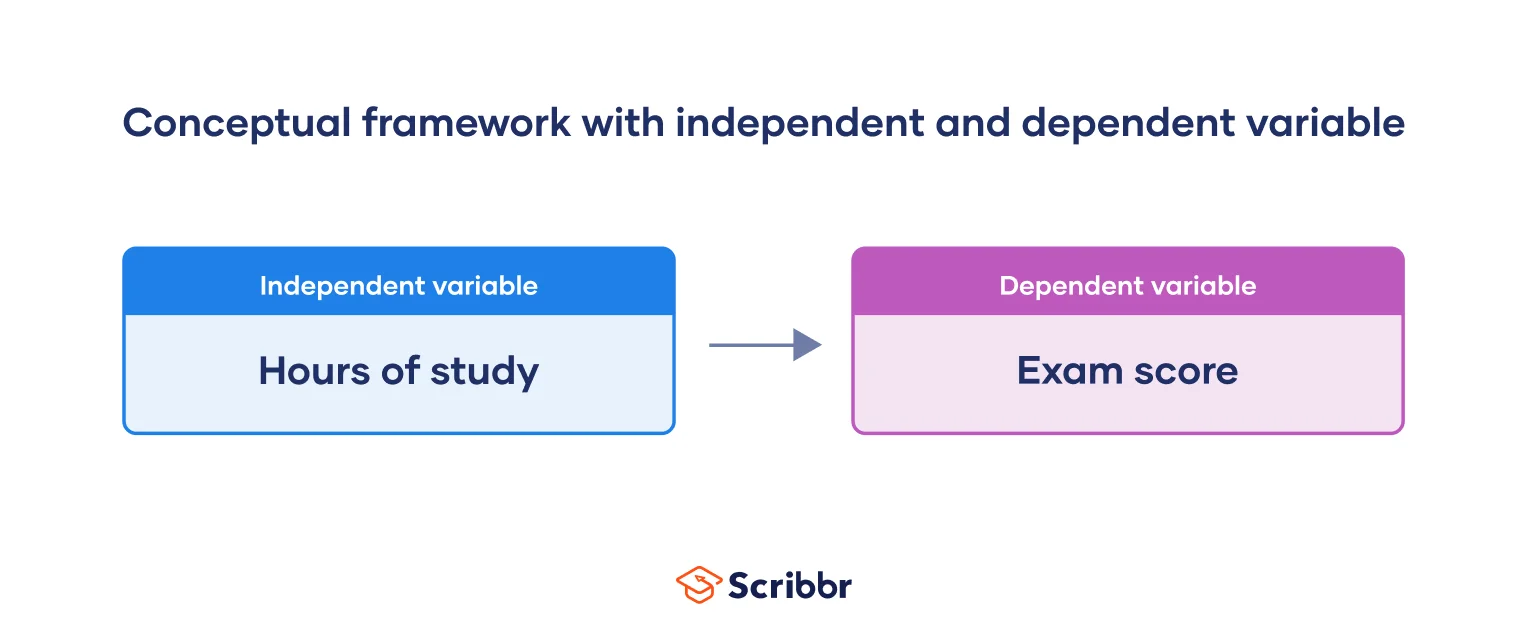

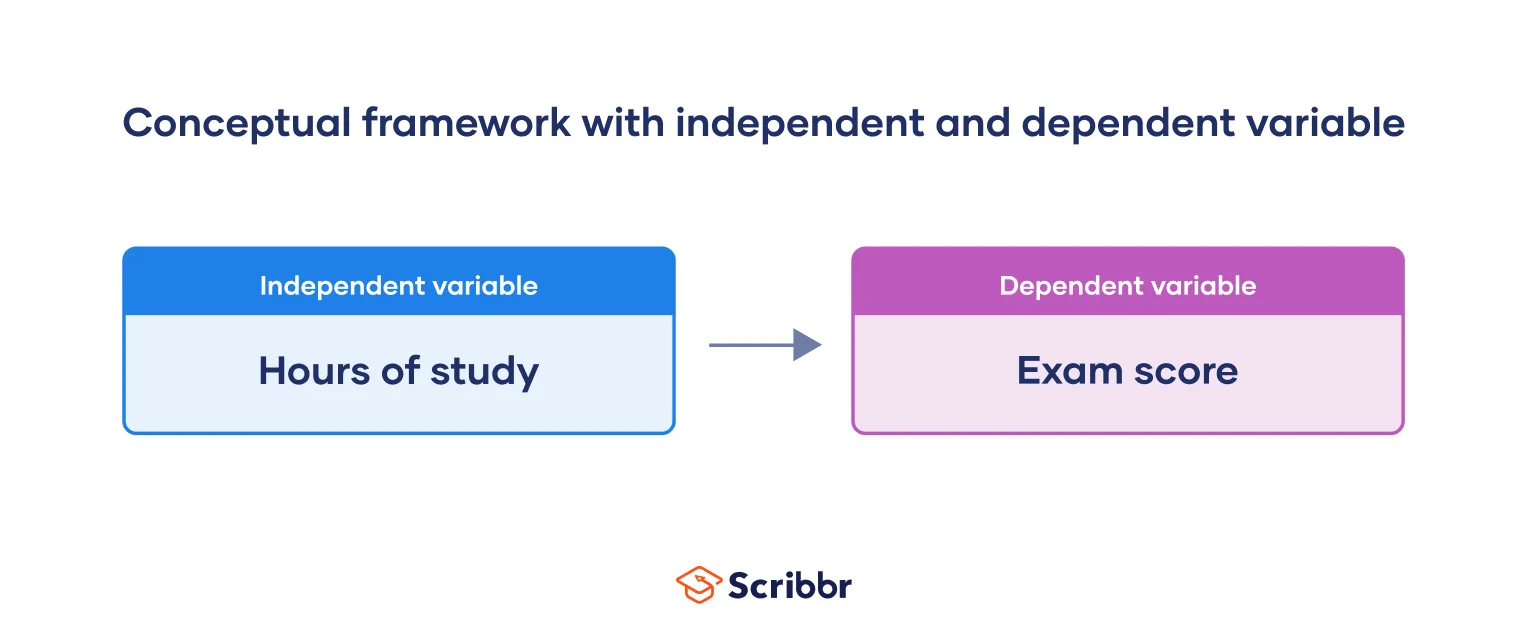

In order to move forward with your research question and test a cause-and-effect relationship, you must first identify at least two key variables: your independent and dependent variables .

- The expected cause, “hours of study,” is the independent variable (the predictor, or explanatory variable)

- The expected effect, “exam score,” is the dependent variable (the response, or outcome variable).

Note that causal relationships often involve several independent variables that affect the dependent variable. For the purpose of this example, we’ll work with just one independent variable (“hours of study”).

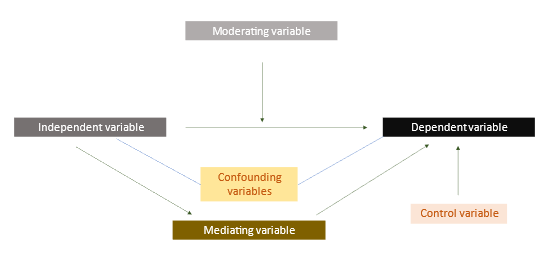

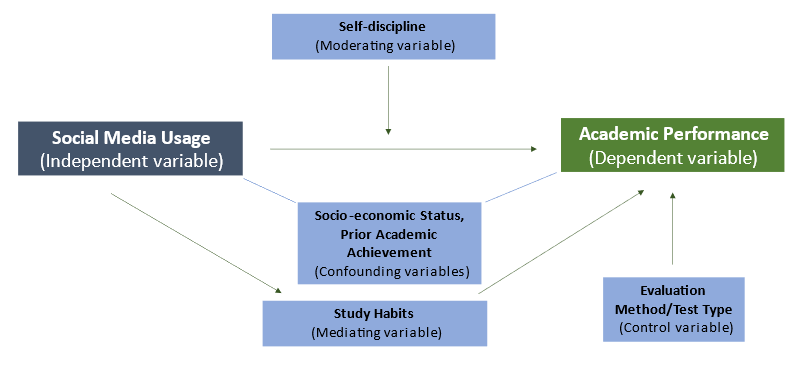

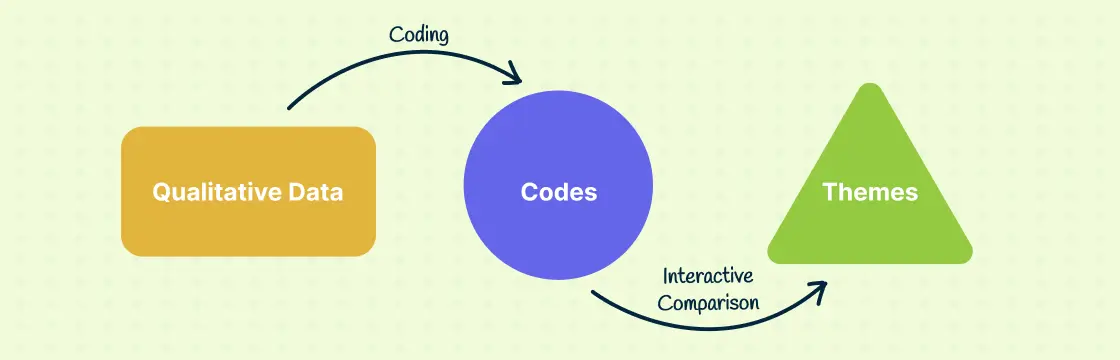

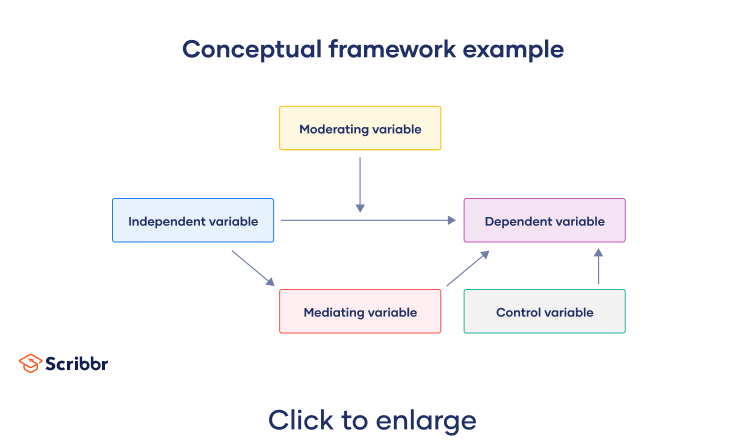

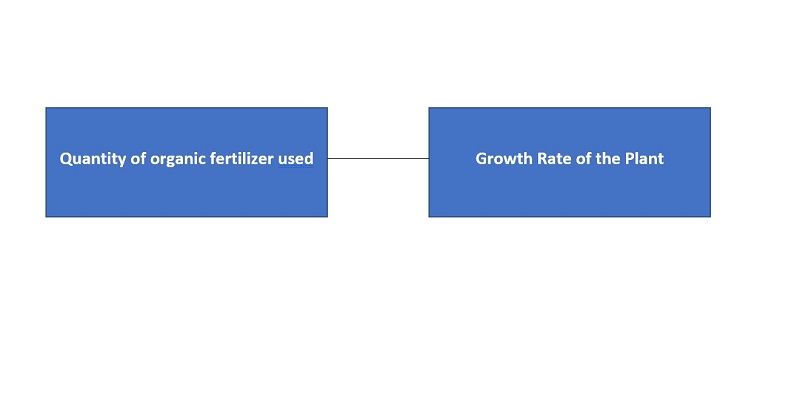

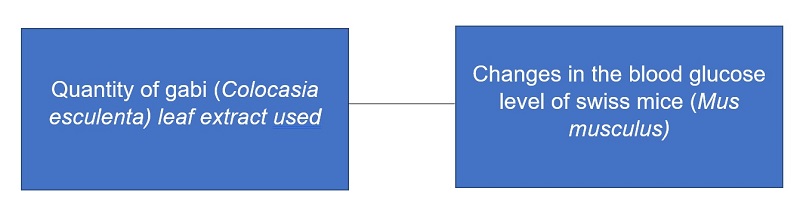

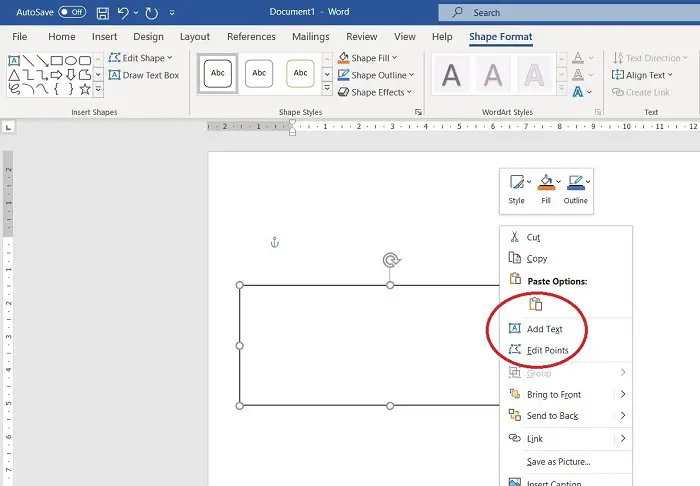

Now that you’ve figured out your research question and variables, the first step in designing your conceptual framework is visualizing your expected cause-and-effect relationship.

We demonstrate this using basic design components of boxes and arrows. Here, each variable appears in a box. To indicate a causal relationship, each arrow should start from the independent variable (the cause) and point to the dependent variable (the effect).

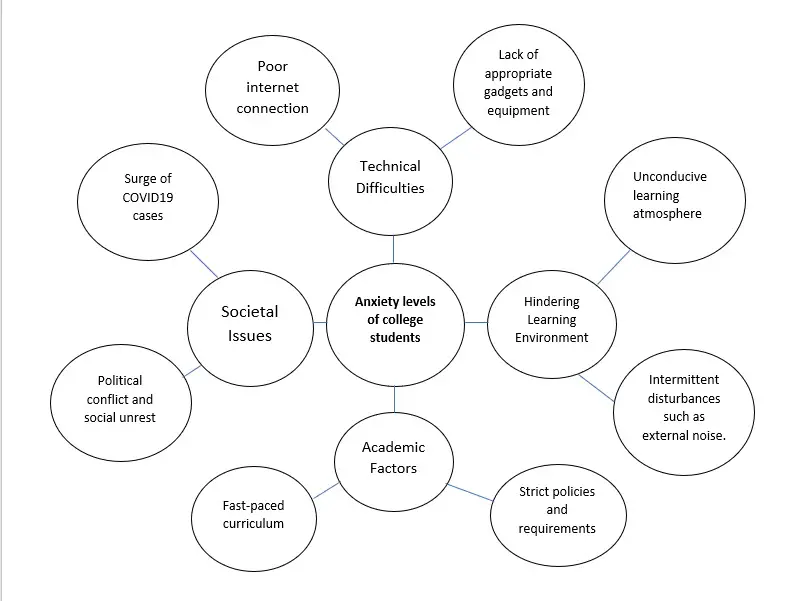

It’s crucial to identify other variables that can influence the relationship between your independent and dependent variables early in your research process.

Some common variables to include are moderating, mediating, and control variables.

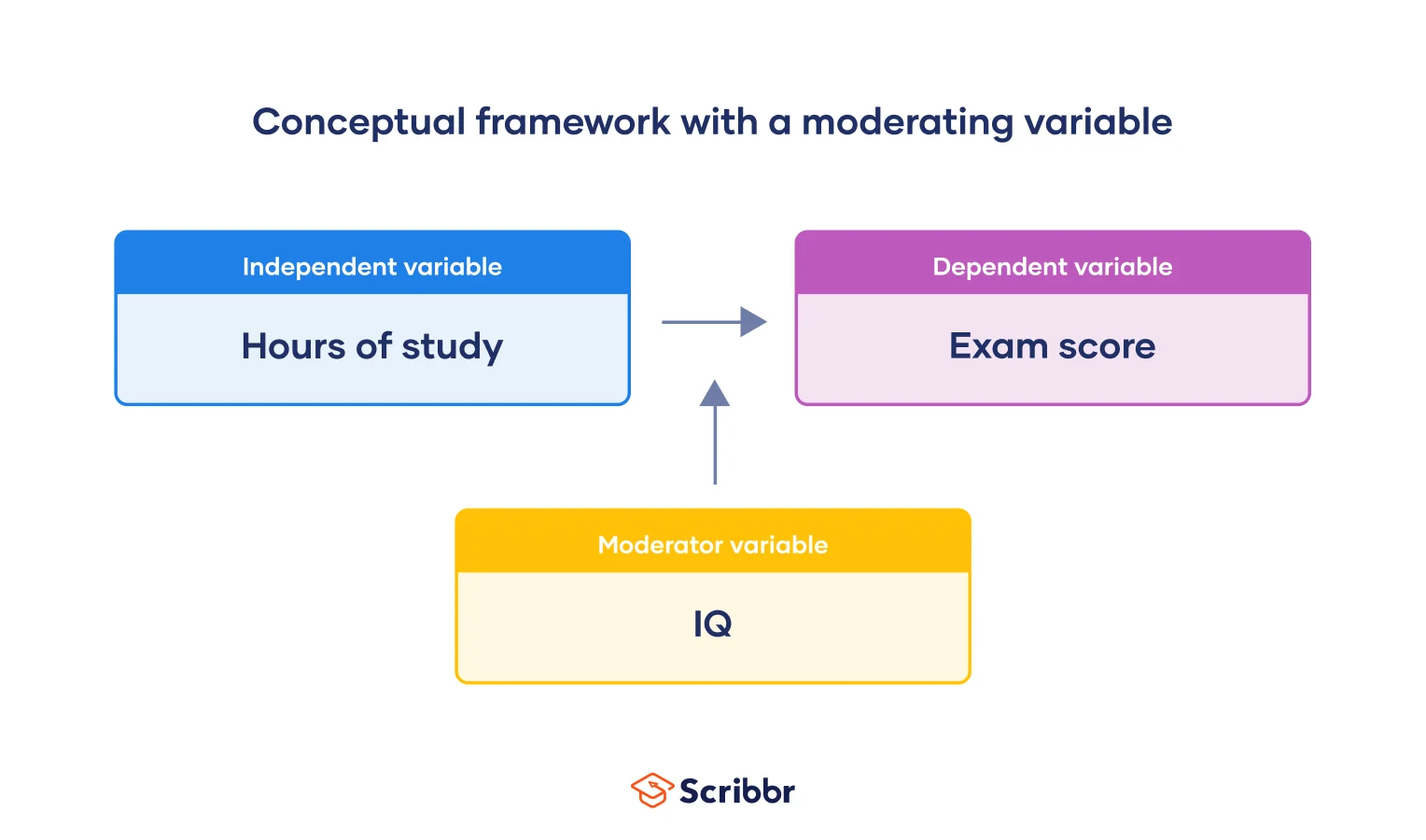

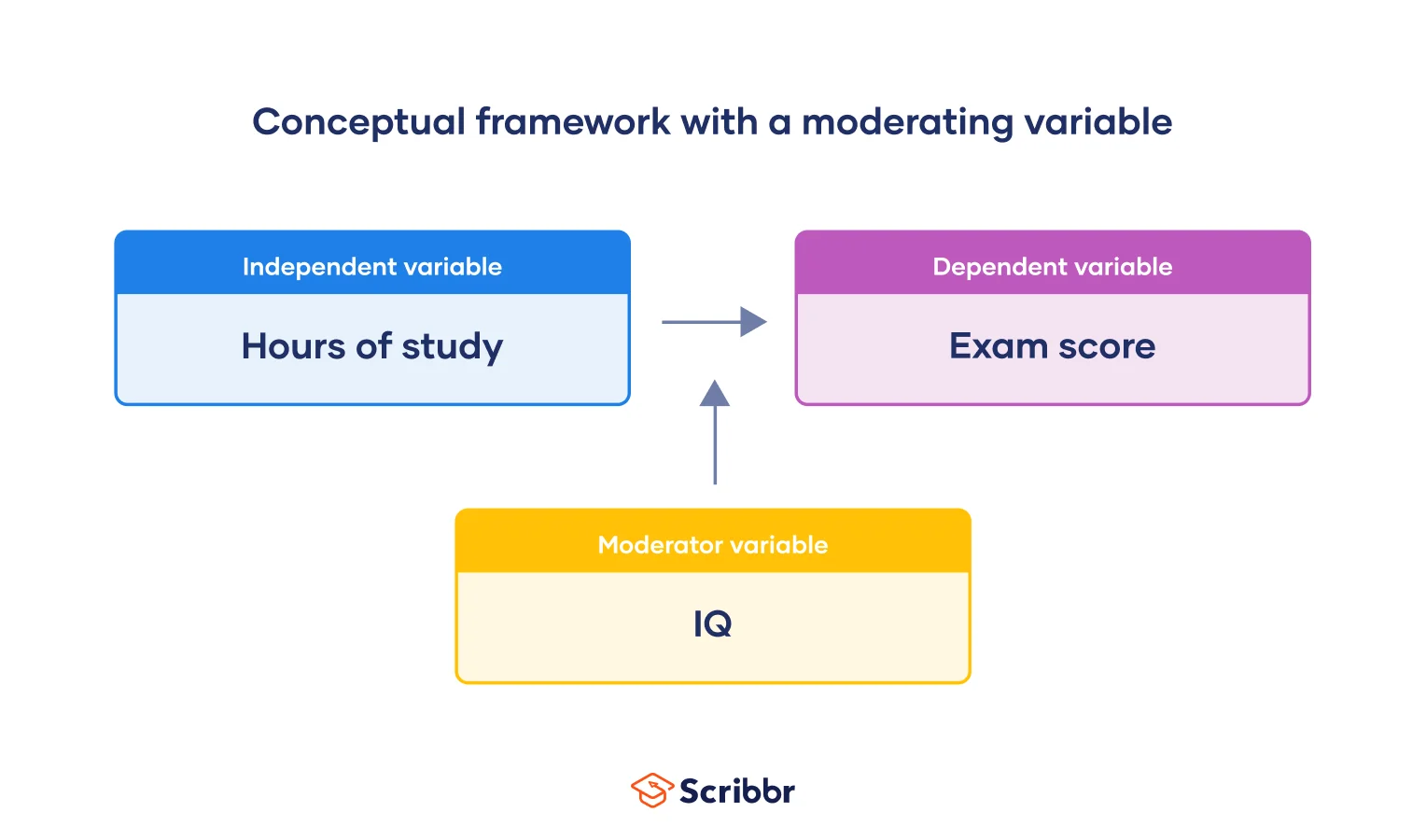

Moderating variables

Moderating variable (or moderators) alter the effect that an independent variable has on a dependent variable. In other words, moderators change the “effect” component of the cause-and-effect relationship.

Let’s add the moderator “IQ.” Here, a student’s IQ level can change the effect that the variable “hours of study” has on the exam score. The higher the IQ, the fewer hours of study are needed to do well on the exam.

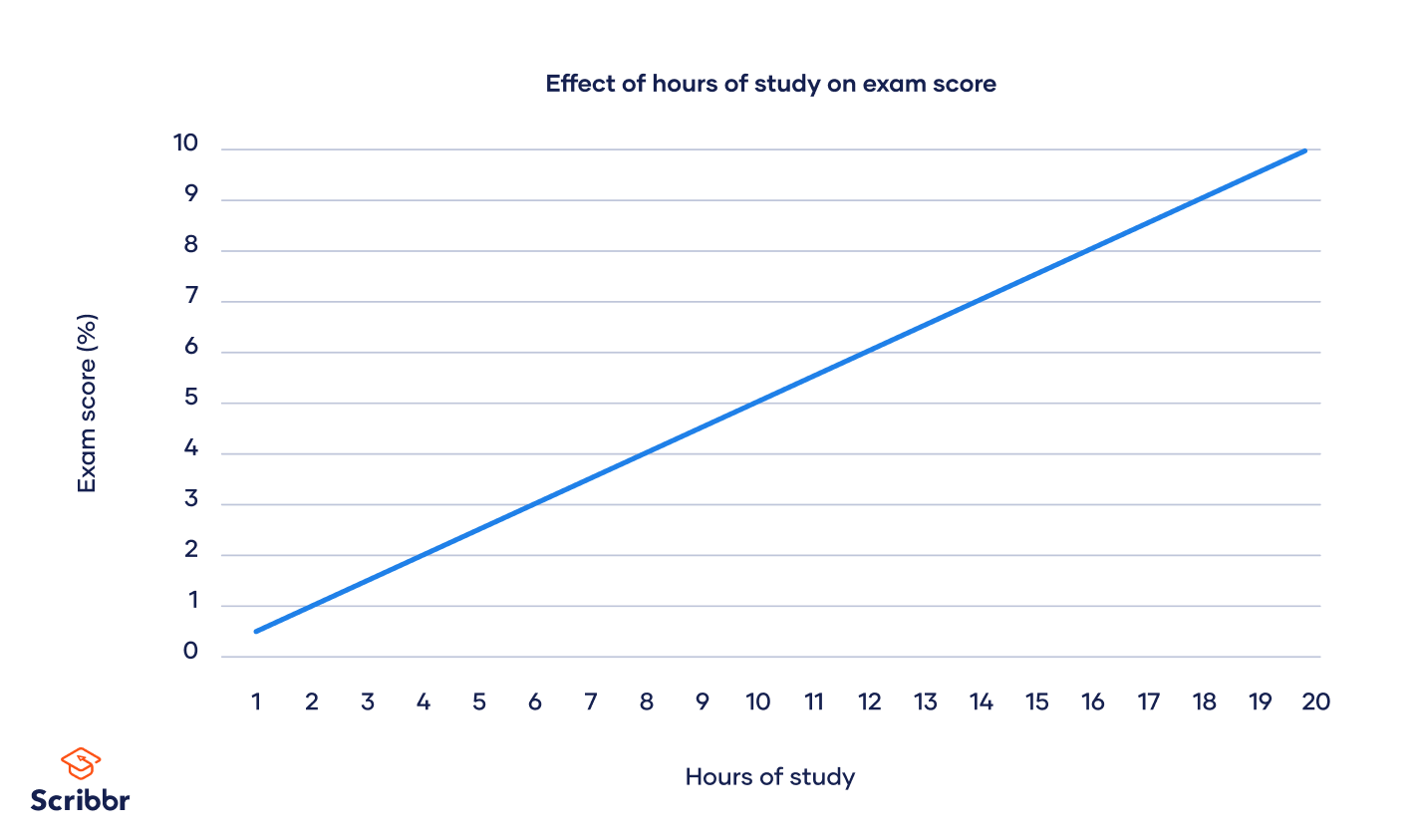

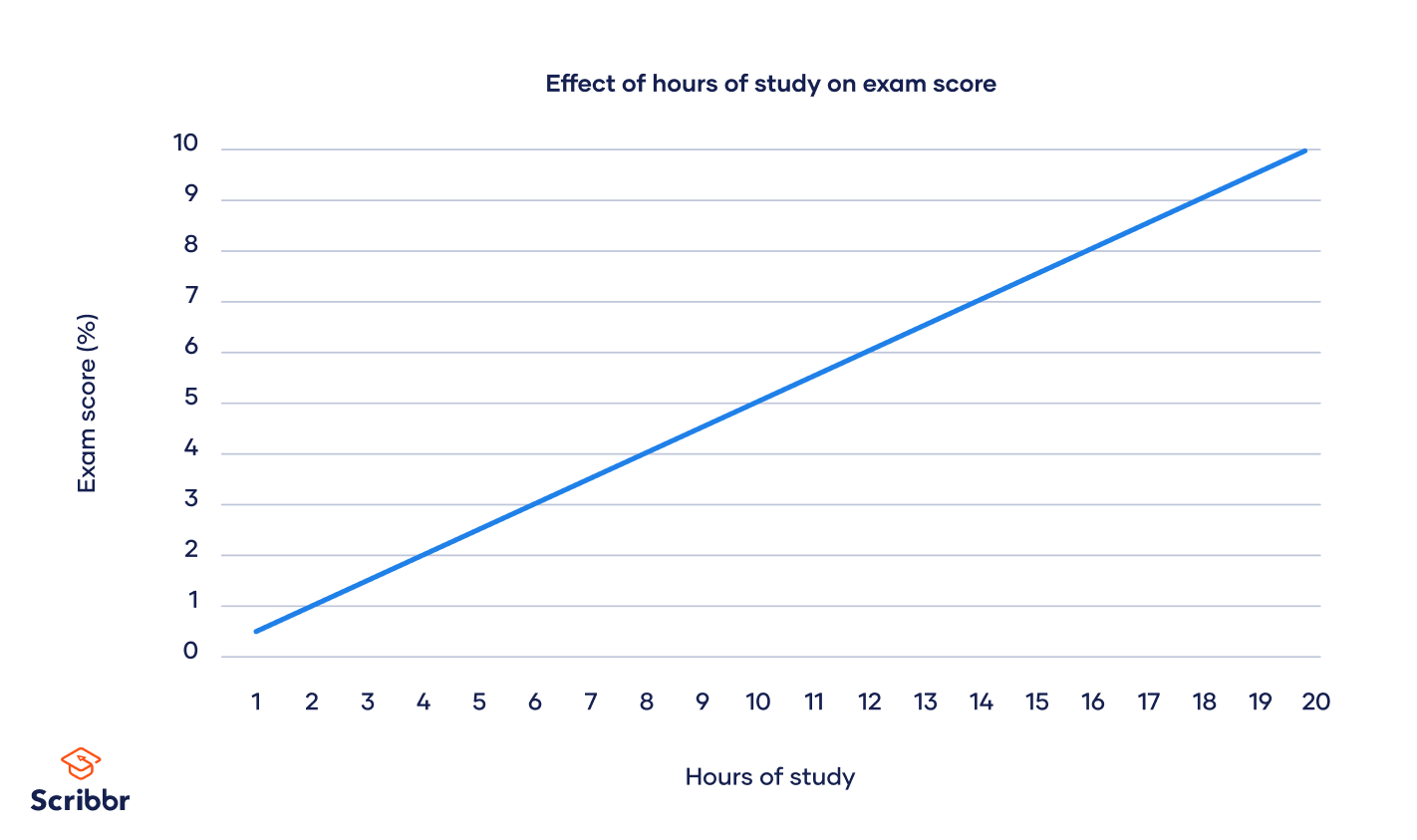

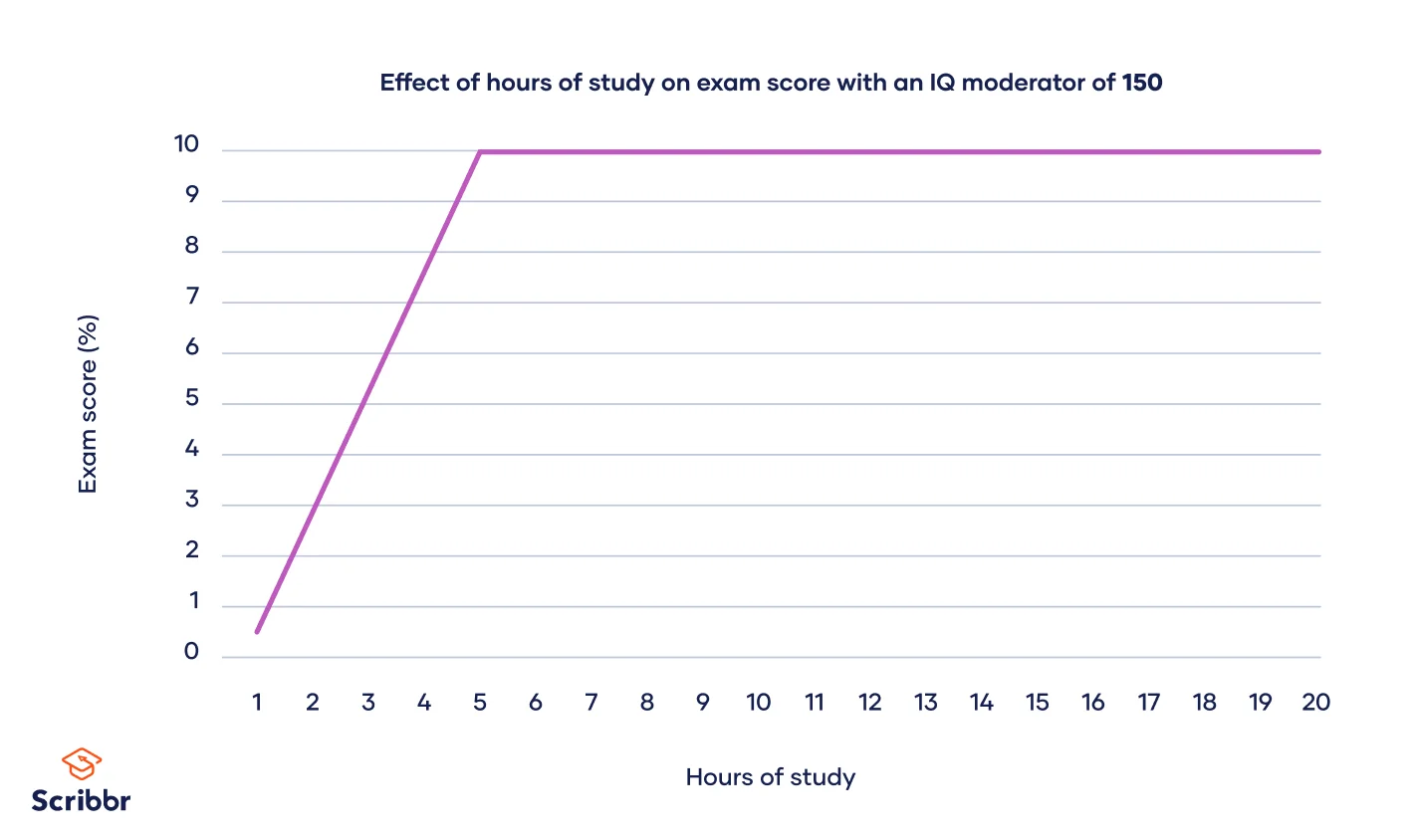

Let’s take a look at how this might work. The graph below shows how the number of hours spent studying affects exam score. As expected, the more hours you study, the better your results. Here, a student who studies for 20 hours will get a perfect score.

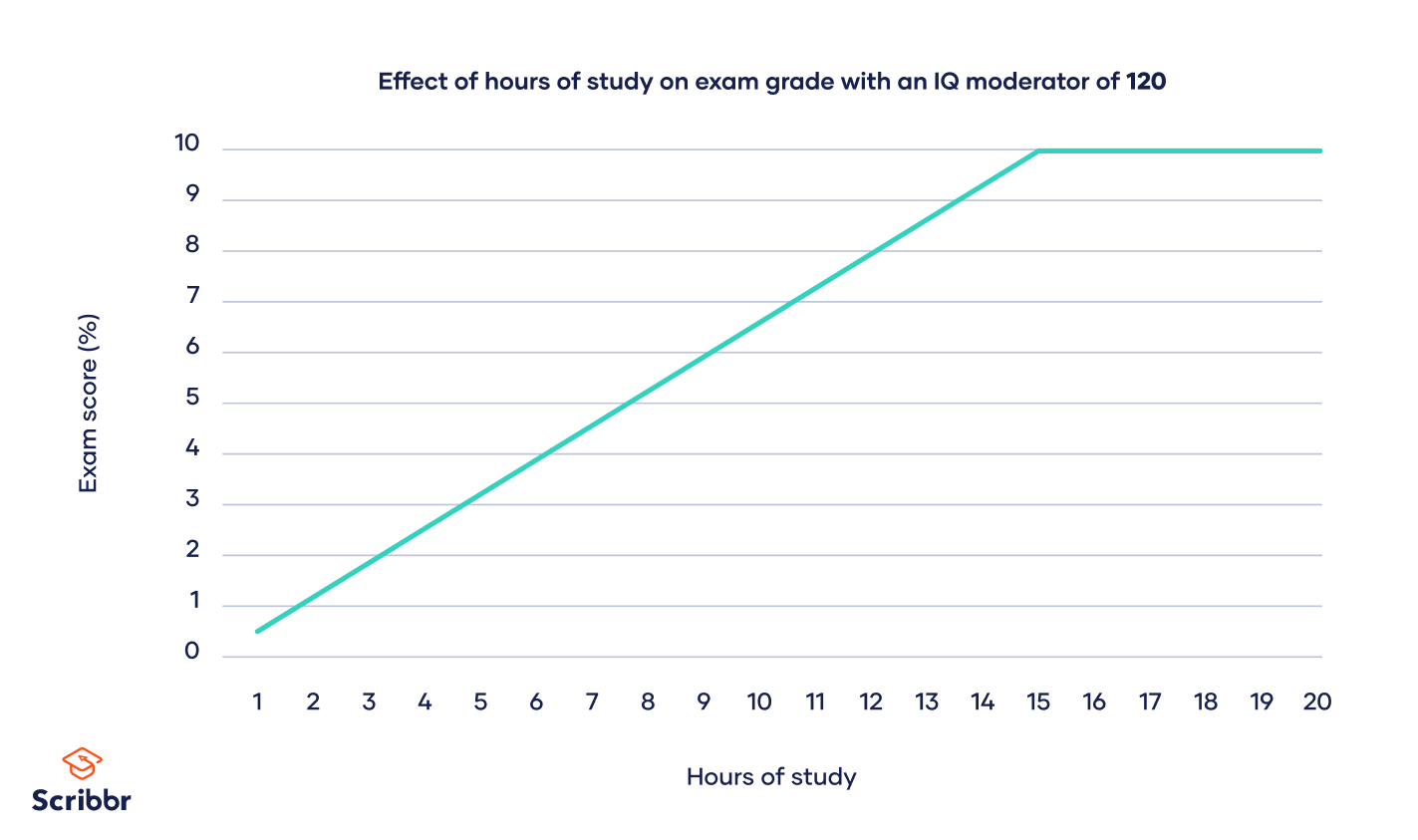

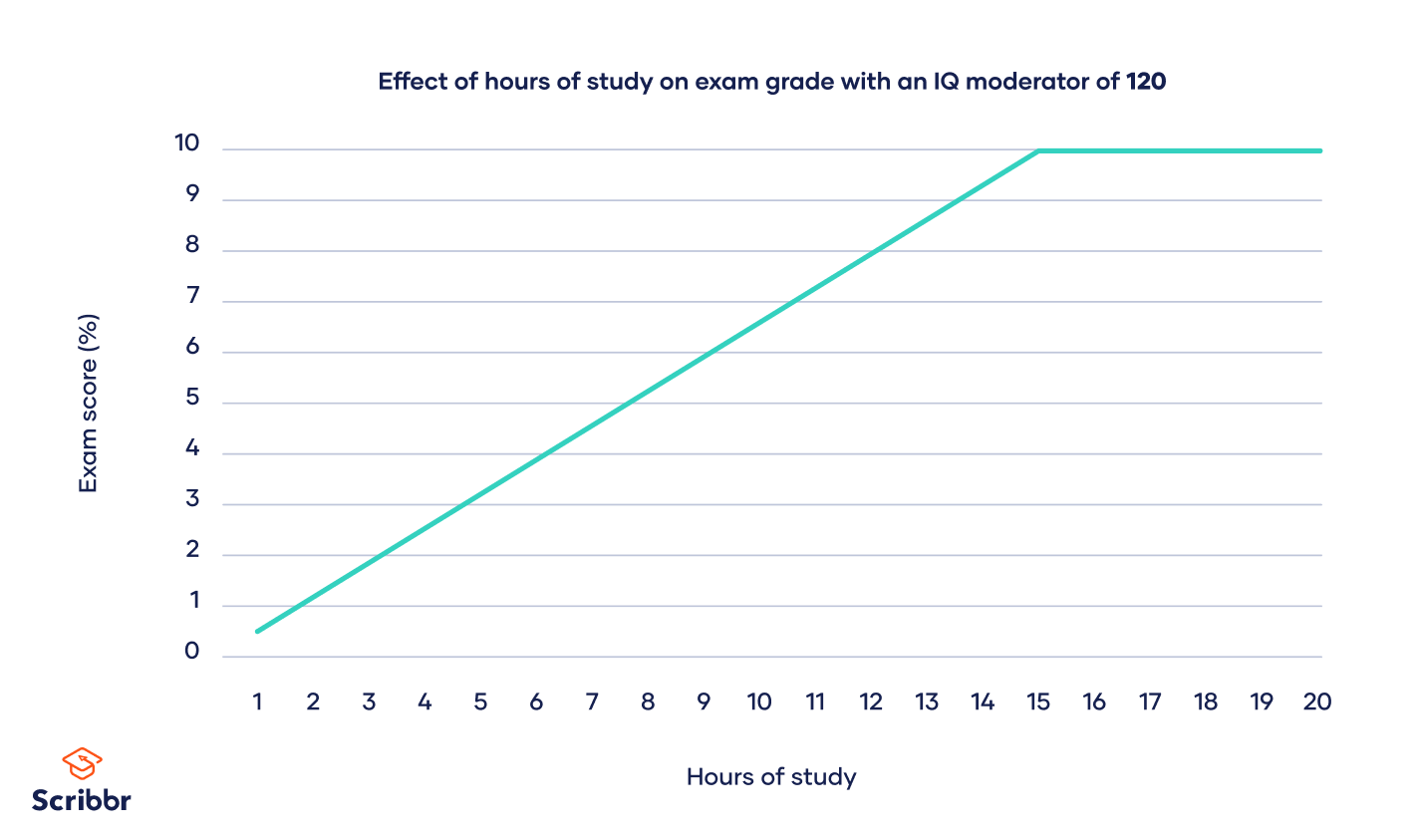

But the graph looks different when we add our “IQ” moderator of 120. A student with this IQ will achieve a perfect score after just 15 hours of study.

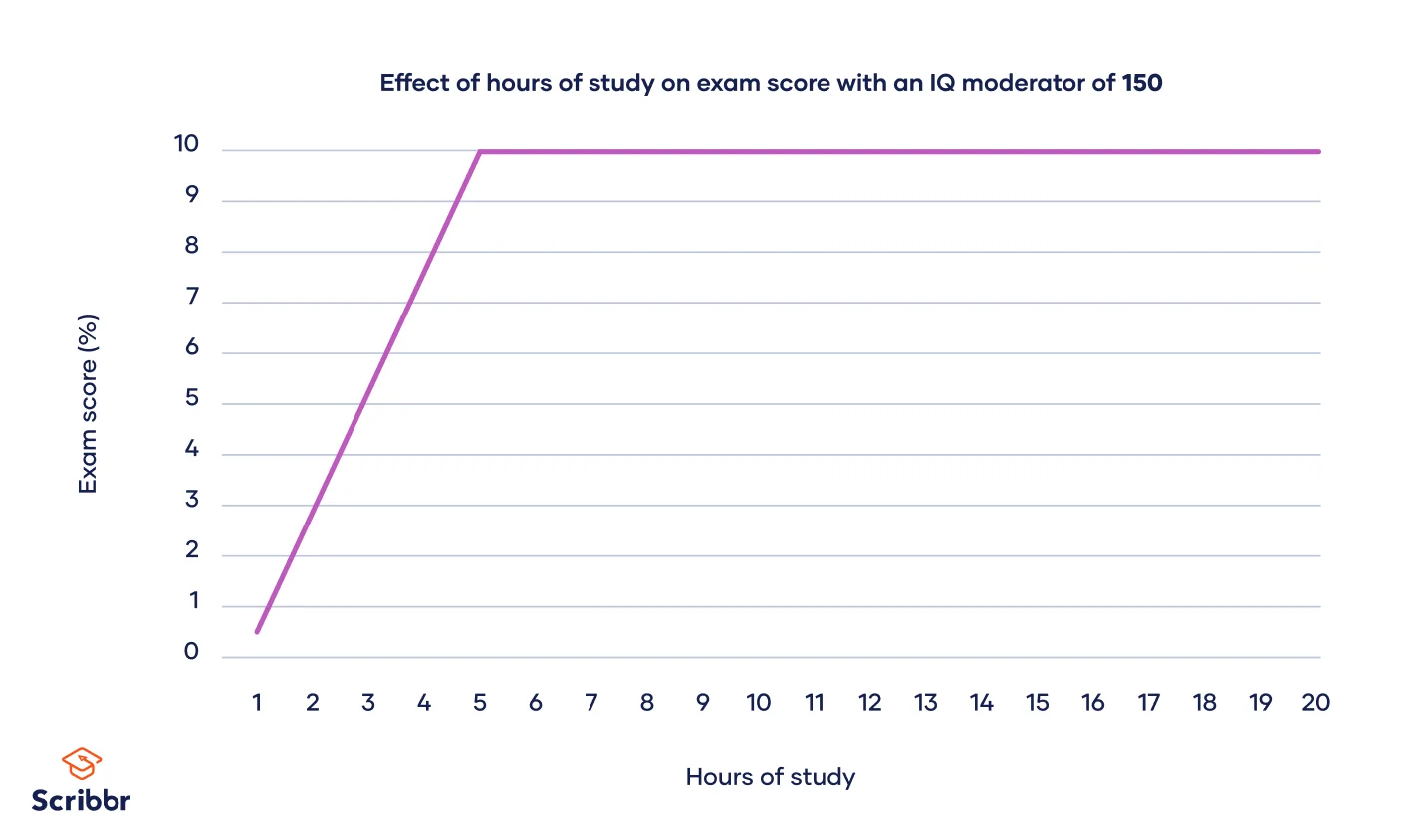

Below, the value of the “IQ” moderator has been increased to 150. A student with this IQ will only need to invest five hours of study in order to get a perfect score.

Here, we see that a moderating variable does indeed change the cause-and-effect relationship between two variables.

Mediating variables

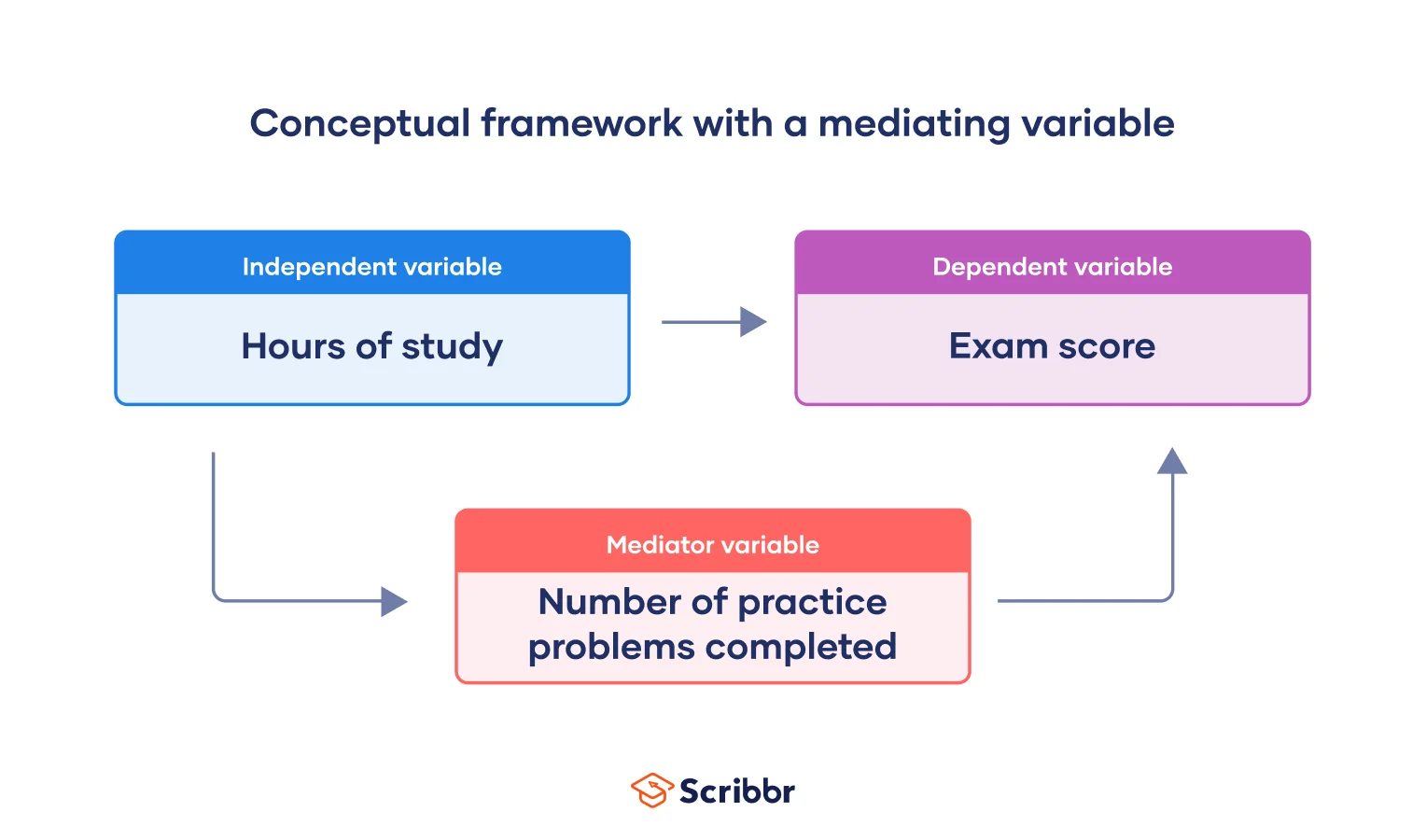

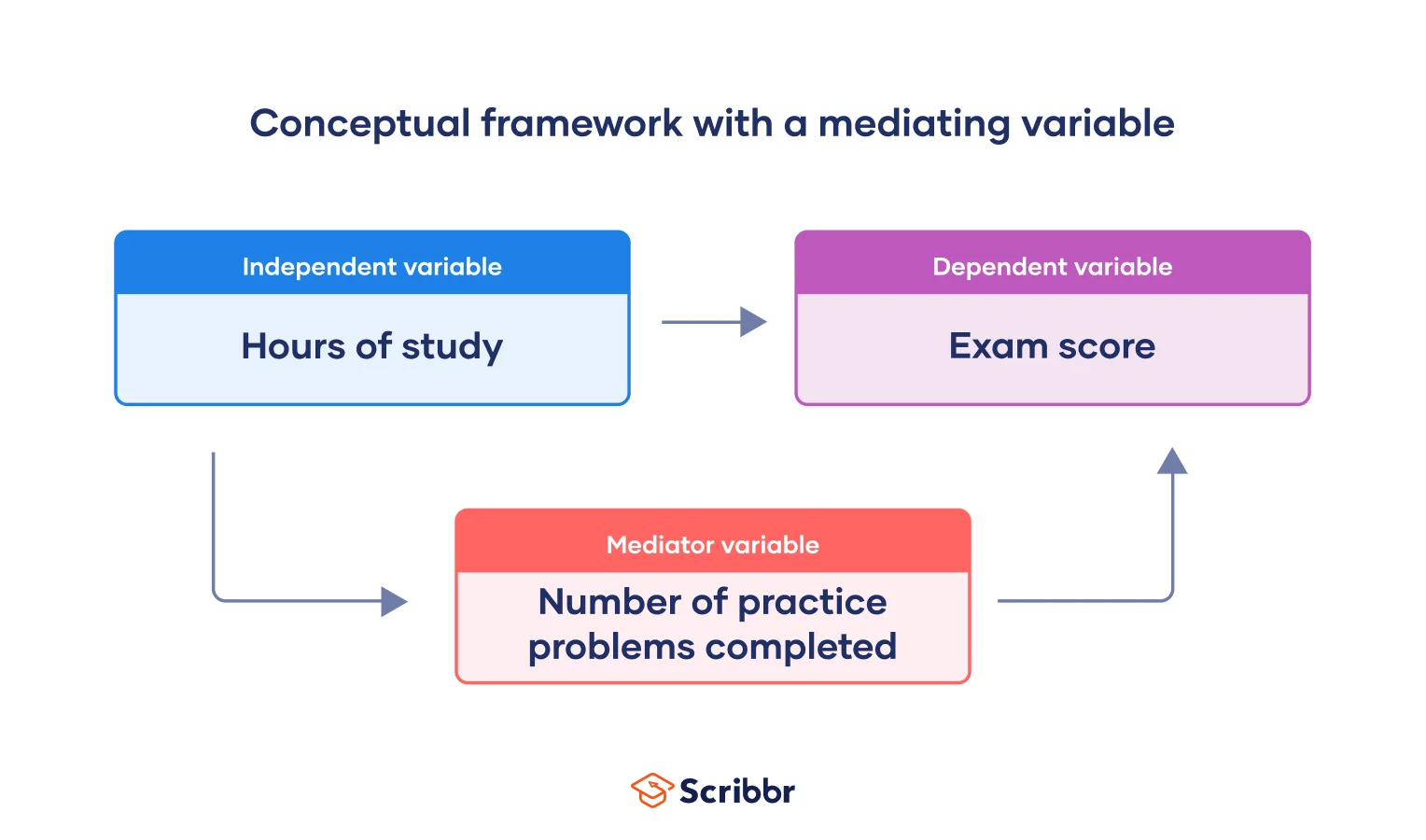

Now we’ll expand the framework by adding a mediating variable . Mediating variables link the independent and dependent variables, allowing the relationship between them to be better explained.

Here’s how the conceptual framework might look if a mediator variable were involved:

In this case, the mediator helps explain why studying more hours leads to a higher exam score. The more hours a student studies, the more practice problems they will complete; the more practice problems completed, the higher the student’s exam score will be.

Moderator vs. mediator

It’s important not to confuse moderating and mediating variables. To remember the difference, you can think of them in relation to the independent variable:

- A moderating variable is not affected by the independent variable, even though it affects the dependent variable. For example, no matter how many hours you study (the independent variable), your IQ will not get higher.

- A mediating variable is affected by the independent variable. In turn, it also affects the dependent variable. Therefore, it links the two variables and helps explain the relationship between them.

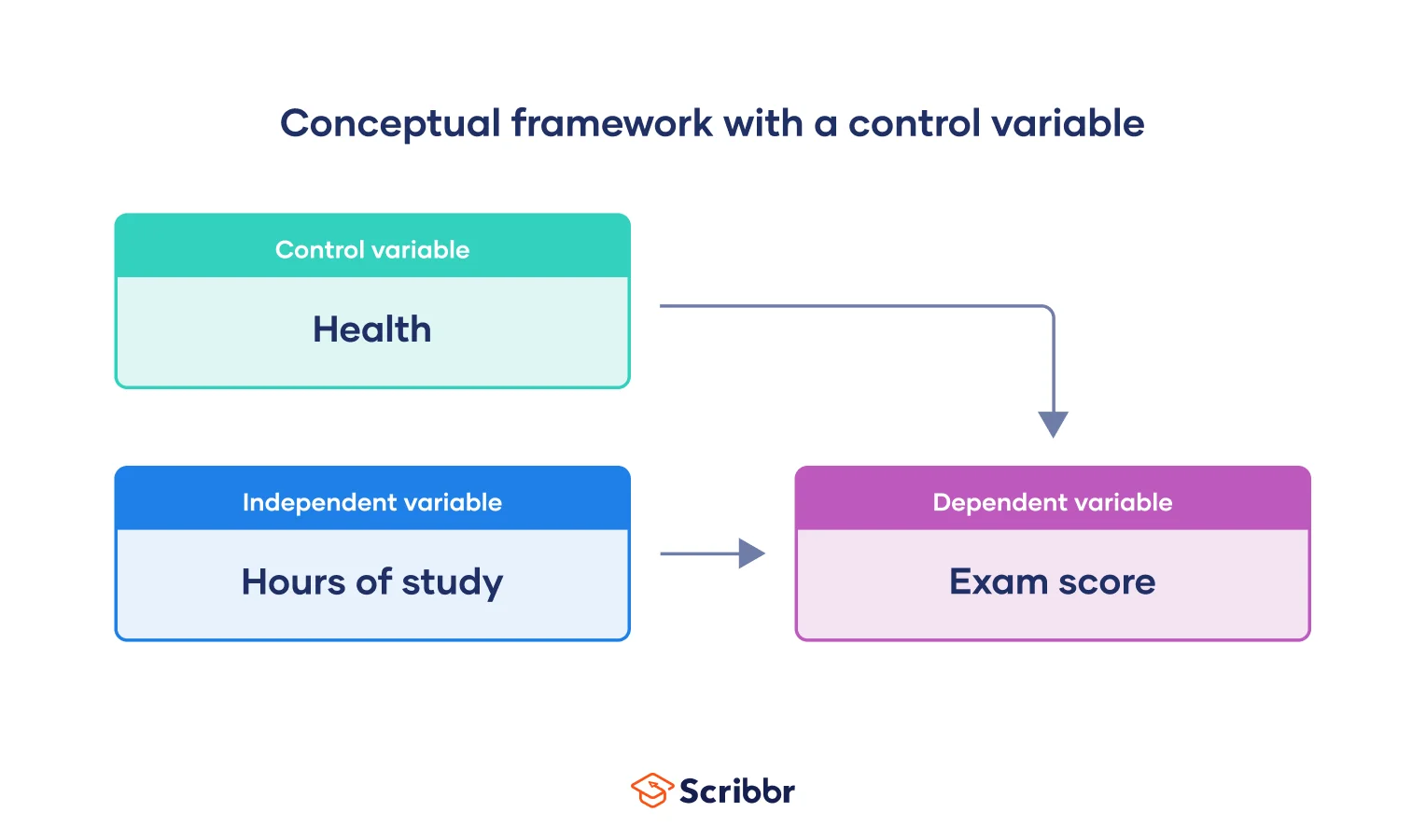

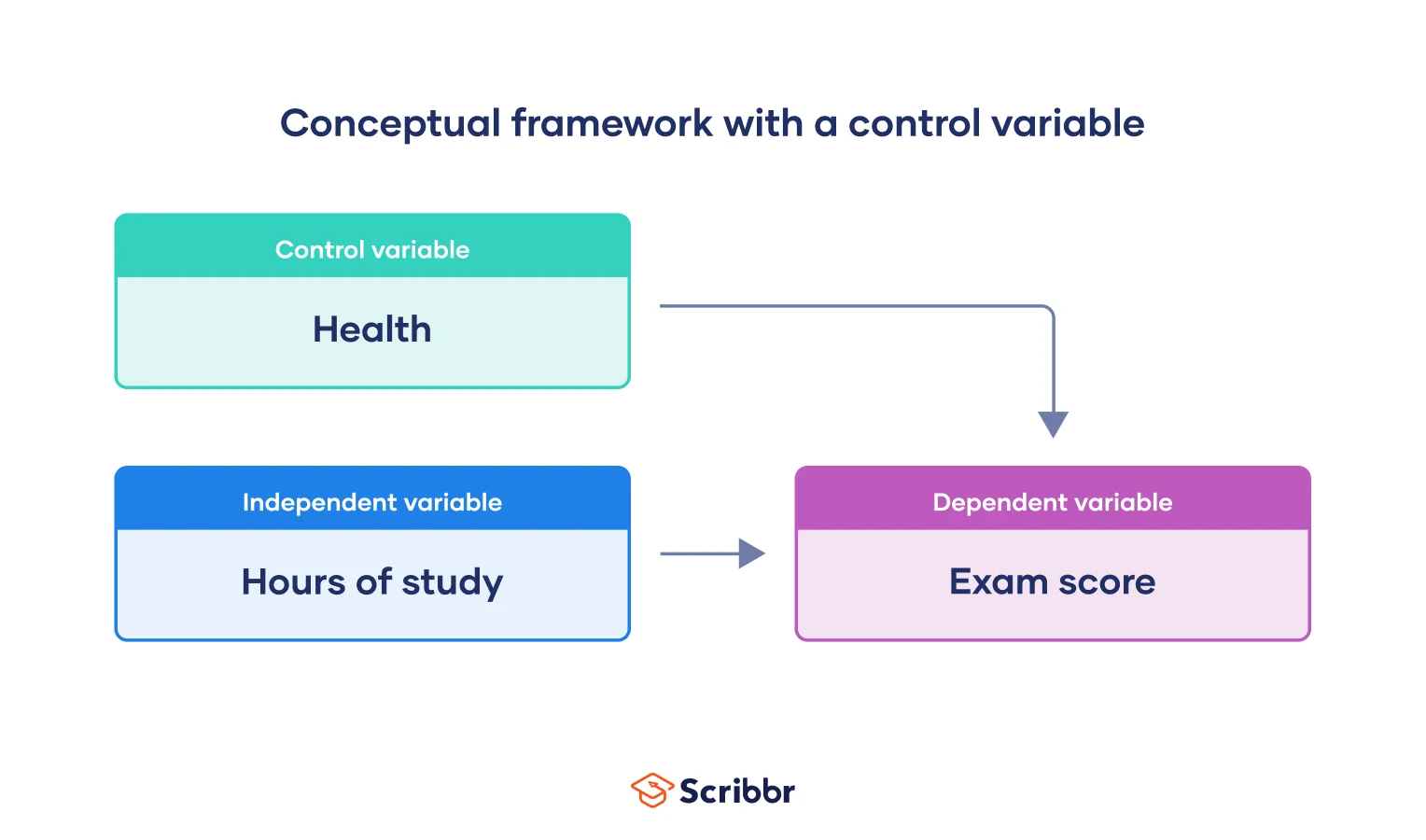

Control variables

Lastly, control variables must also be taken into account. These are variables that are held constant so that they don’t interfere with the results. Even though you aren’t interested in measuring them for your study, it’s crucial to be aware of as many of them as you can be.

A mediator variable explains the process through which two variables are related, while a moderator variable affects the strength and direction of that relationship.

A confounding variable is closely related to both the independent and dependent variables in a study. An independent variable represents the supposed cause , while the dependent variable is the supposed effect . A confounding variable is a third variable that influences both the independent and dependent variables.

Failing to account for confounding variables can cause you to wrongly estimate the relationship between your independent and dependent variables.

Yes, but including more than one of either type requires multiple research questions .

For example, if you are interested in the effect of a diet on health, you can use multiple measures of health: blood sugar, blood pressure, weight, pulse, and many more. Each of these is its own dependent variable with its own research question.

You could also choose to look at the effect of exercise levels as well as diet, or even the additional effect of the two combined. Each of these is a separate independent variable .

To ensure the internal validity of an experiment , you should only change one independent variable at a time.

A control variable is any variable that’s held constant in a research study. It’s not a variable of interest in the study, but it’s controlled because it could influence the outcomes.

A confounding variable , also called a confounder or confounding factor, is a third variable in a study examining a potential cause-and-effect relationship.

A confounding variable is related to both the supposed cause and the supposed effect of the study. It can be difficult to separate the true effect of the independent variable from the effect of the confounding variable.

In your research design , it’s important to identify potential confounding variables and plan how you will reduce their impact.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Swaen, B. & George, T. (2024, March 18). What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved June 20, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/conceptual-framework/

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked

Independent vs. dependent variables | definition & examples, mediator vs. moderator variables | differences & examples, control variables | what are they & why do they matter, what is your plagiarism score.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Conceptual Framework – Types, Methodology and Examples

Conceptual Framework – Types, Methodology and Examples

Table of Contents

Conceptual Framework

Definition:

A conceptual framework is a structured approach to organizing and understanding complex ideas, theories, or concepts. It provides a systematic and coherent way of thinking about a problem or topic, and helps to guide research or analysis in a particular field.

A conceptual framework typically includes a set of assumptions, concepts, and propositions that form a theoretical framework for understanding a particular phenomenon. It can be used to develop hypotheses, guide empirical research, or provide a framework for evaluating and interpreting data.

Conceptual Framework in Research

In research, a conceptual framework is a theoretical structure that provides a framework for understanding a particular phenomenon or problem. It is a key component of any research project and helps to guide the research process from start to finish.

A conceptual framework provides a clear understanding of the variables, relationships, and assumptions that underpin a research study. It outlines the key concepts that the study is investigating and how they are related to each other. It also defines the scope of the study and sets out the research questions or hypotheses.

Types of Conceptual Framework

Types of Conceptual Framework are as follows:

Theoretical Framework

A theoretical framework is an overarching set of concepts, ideas, and assumptions that help to explain and interpret a phenomenon. It provides a theoretical perspective on the phenomenon being studied and helps researchers to identify the relationships between different concepts. For example, a theoretical framework for a study on the impact of social media on mental health might draw on theories of communication, social influence, and psychological well-being.

Conceptual Model

A conceptual model is a visual or written representation of a complex system or phenomenon. It helps to identify the main components of the system and the relationships between them. For example, a conceptual model for a study on the factors that influence employee turnover might include factors such as job satisfaction, salary, work-life balance, and job security, and the relationships between them.

Empirical Framework

An empirical framework is based on empirical data and helps to explain a particular phenomenon. It involves collecting data, analyzing it, and developing a framework to explain the results. For example, an empirical framework for a study on the impact of a new health intervention might involve collecting data on the intervention’s effectiveness, cost, and acceptability to patients.

Descriptive Framework

A descriptive framework is used to describe a particular phenomenon. It helps to identify the main characteristics of the phenomenon and to develop a vocabulary to describe it. For example, a descriptive framework for a study on different types of musical genres might include descriptions of the instruments used, the rhythms and beats, the vocal styles, and the cultural contexts of each genre.

Analytical Framework

An analytical framework is used to analyze a particular phenomenon. It involves breaking down the phenomenon into its constituent parts and analyzing them separately. This type of framework is often used in social science research. For example, an analytical framework for a study on the impact of race on police brutality might involve analyzing the historical and cultural factors that contribute to racial bias, the organizational factors that influence police behavior, and the psychological factors that influence individual officers’ behavior.

Conceptual Framework for Policy Analysis

A conceptual framework for policy analysis is used to guide the development of policies or programs. It helps policymakers to identify the key issues and to develop strategies to address them. For example, a conceptual framework for a policy analysis on climate change might involve identifying the key stakeholders, assessing their interests and concerns, and developing policy options to mitigate the impacts of climate change.

Logical Frameworks

Logical frameworks are used to plan and evaluate projects and programs. They provide a structured approach to identifying project goals, objectives, and outcomes, and help to ensure that all stakeholders are aligned and working towards the same objectives.

Conceptual Frameworks for Program Evaluation

These frameworks are used to evaluate the effectiveness of programs or interventions. They provide a structure for identifying program goals, objectives, and outcomes, and help to measure the impact of the program on its intended beneficiaries.

Conceptual Frameworks for Organizational Analysis

These frameworks are used to analyze and evaluate organizational structures, processes, and performance. They provide a structured approach to understanding the relationships between different departments, functions, and stakeholders within an organization.

Conceptual Frameworks for Strategic Planning

These frameworks are used to develop and implement strategic plans for organizations or businesses. They help to identify the key factors and stakeholders that will impact the success of the plan, and provide a structure for setting goals, developing strategies, and monitoring progress.

Components of Conceptual Framework

The components of a conceptual framework typically include:

- Research question or problem statement : This component defines the problem or question that the conceptual framework seeks to address. It sets the stage for the development of the framework and guides the selection of the relevant concepts and constructs.

- Concepts : These are the general ideas, principles, or categories that are used to describe and explain the phenomenon or problem under investigation. Concepts provide the building blocks of the framework and help to establish a common language for discussing the issue.

- Constructs : Constructs are the specific variables or concepts that are used to operationalize the general concepts. They are measurable or observable and serve as indicators of the underlying concept.

- Propositions or hypotheses : These are statements that describe the relationships between the concepts or constructs in the framework. They provide a basis for testing the validity of the framework and for generating new insights or theories.

- Assumptions : These are the underlying beliefs or values that shape the framework. They may be explicit or implicit and may influence the selection and interpretation of the concepts and constructs.

- Boundaries : These are the limits or scope of the framework. They define the focus of the investigation and help to clarify what is included and excluded from the analysis.

- Context : This component refers to the broader social, cultural, and historical factors that shape the phenomenon or problem under investigation. It helps to situate the framework within a larger theoretical or empirical context and to identify the relevant variables and factors that may affect the phenomenon.

- Relationships and connections: These are the connections and interrelationships between the different components of the conceptual framework. They describe how the concepts and constructs are linked and how they contribute to the overall understanding of the phenomenon or problem.

- Variables : These are the factors that are being measured or observed in the study. They are often operationalized as constructs and are used to test the propositions or hypotheses.

- Methodology : This component describes the research methods and techniques that will be used to collect and analyze data. It includes the sampling strategy, data collection methods, data analysis techniques, and ethical considerations.

- Literature review : This component provides an overview of the existing research and theories related to the phenomenon or problem under investigation. It helps to identify the gaps in the literature and to situate the framework within the broader theoretical and empirical context.

- Outcomes and implications: These are the expected outcomes or implications of the study. They describe the potential contributions of the study to the theoretical and empirical knowledge in the field and the practical implications for policy and practice.

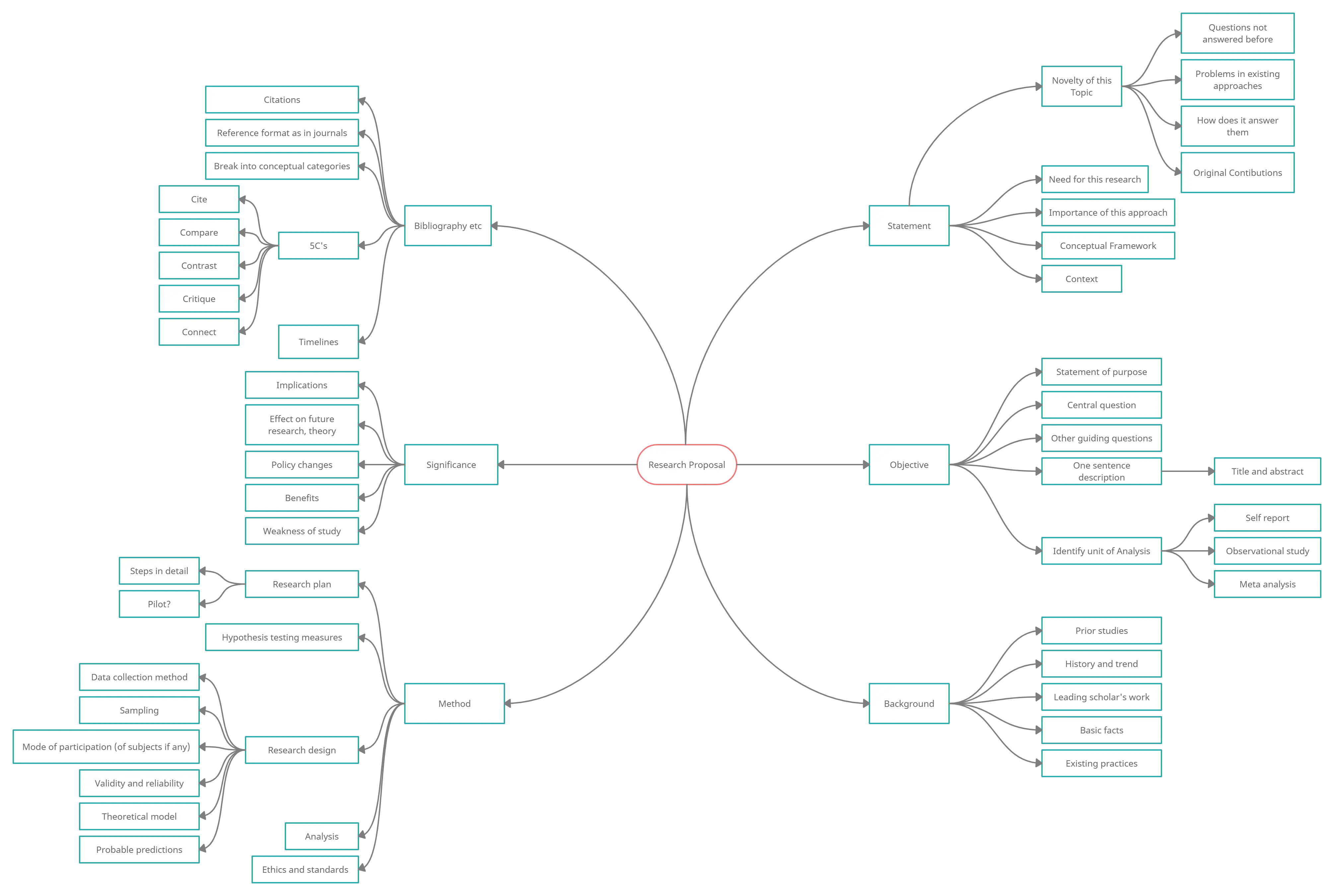

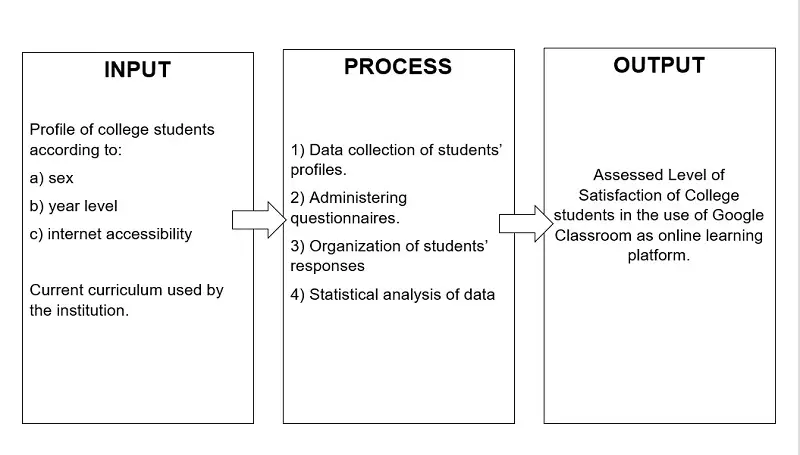

Conceptual Framework Methodology

Conceptual Framework Methodology is a research method that is commonly used in academic and scientific research to develop a theoretical framework for a study. It is a systematic approach that helps researchers to organize their thoughts and ideas, identify the variables that are relevant to their study, and establish the relationships between these variables.

Here are the steps involved in the conceptual framework methodology:

Identify the Research Problem

The first step is to identify the research problem or question that the study aims to answer. This involves identifying the gaps in the existing literature and determining what specific issue the study aims to address.

Conduct a Literature Review

The second step involves conducting a thorough literature review to identify the existing theories, models, and frameworks that are relevant to the research question. This will help the researcher to identify the key concepts and variables that need to be considered in the study.

Define key Concepts and Variables

The next step is to define the key concepts and variables that are relevant to the study. This involves clearly defining the terms used in the study, and identifying the factors that will be measured or observed in the study.

Develop a Theoretical Framework

Once the key concepts and variables have been identified, the researcher can develop a theoretical framework. This involves establishing the relationships between the key concepts and variables, and creating a visual representation of these relationships.

Test the Framework

The final step is to test the theoretical framework using empirical data. This involves collecting and analyzing data to determine whether the relationships between the key concepts and variables that were identified in the framework are accurate and valid.

Examples of Conceptual Framework

Some realtime Examples of Conceptual Framework are as follows:

- In economics , the concept of supply and demand is a well-known conceptual framework. It provides a structure for understanding how prices are set in a market, based on the interplay of the quantity of goods supplied by producers and the quantity of goods demanded by consumers.

- In psychology , the cognitive-behavioral framework is a widely used conceptual framework for understanding mental health and illness. It emphasizes the role of thoughts and behaviors in shaping emotions and the importance of cognitive restructuring and behavior change in treatment.

- In sociology , the social determinants of health framework provides a way of understanding how social and economic factors such as income, education, and race influence health outcomes. This framework is widely used in public health research and policy.

- In environmental science , the ecosystem services framework is a way of understanding the benefits that humans derive from natural ecosystems, such as clean air and water, pollination, and carbon storage. This framework is used to guide conservation and land-use decisions.

- In education, the constructivist framework is a way of understanding how learners construct knowledge through active engagement with their environment. This framework is used to guide instructional design and teaching strategies.

Applications of Conceptual Framework

Some of the applications of Conceptual Frameworks are as follows:

- Research : Conceptual frameworks are used in research to guide the design, implementation, and interpretation of studies. Researchers use conceptual frameworks to develop hypotheses, identify research questions, and select appropriate methods for collecting and analyzing data.

- Policy: Conceptual frameworks are used in policy-making to guide the development of policies and programs. Policymakers use conceptual frameworks to identify key factors that influence a particular problem or issue, and to develop strategies for addressing them.

- Education : Conceptual frameworks are used in education to guide the design and implementation of instructional strategies and curriculum. Educators use conceptual frameworks to identify learning objectives, select appropriate teaching methods, and assess student learning.

- Management : Conceptual frameworks are used in management to guide decision-making and strategy development. Managers use conceptual frameworks to understand the internal and external factors that influence their organizations, and to develop strategies for achieving their goals.

- Evaluation : Conceptual frameworks are used in evaluation to guide the development of evaluation plans and to interpret evaluation results. Evaluators use conceptual frameworks to identify key outcomes, indicators, and measures, and to develop a logic model for their evaluation.

Purpose of Conceptual Framework

The purpose of a conceptual framework is to provide a theoretical foundation for understanding and analyzing complex phenomena. Conceptual frameworks help to:

- Guide research : Conceptual frameworks provide a framework for researchers to develop hypotheses, identify research questions, and select appropriate methods for collecting and analyzing data. By providing a theoretical foundation for research, conceptual frameworks help to ensure that research is rigorous, systematic, and valid.

- Provide clarity: Conceptual frameworks help to provide clarity and structure to complex phenomena by identifying key concepts, relationships, and processes. By providing a clear and systematic understanding of a phenomenon, conceptual frameworks help to ensure that researchers, policymakers, and practitioners are all on the same page when it comes to understanding the issue at hand.

- Inform decision-making : Conceptual frameworks can be used to inform decision-making and strategy development by identifying key factors that influence a particular problem or issue. By understanding the complex interplay of factors that contribute to a particular issue, decision-makers can develop more effective strategies for addressing the problem.

- Facilitate communication : Conceptual frameworks provide a common language and conceptual framework for researchers, policymakers, and practitioners to communicate and collaborate on complex issues. By providing a shared understanding of a phenomenon, conceptual frameworks help to ensure that everyone is working towards the same goal.

When to use Conceptual Framework

There are several situations when it is appropriate to use a conceptual framework:

- To guide the research : A conceptual framework can be used to guide the research process by providing a clear roadmap for the research project. It can help researchers identify key variables and relationships, and develop hypotheses or research questions.

- To clarify concepts : A conceptual framework can be used to clarify and define key concepts and terms used in a research project. It can help ensure that all researchers are using the same language and have a shared understanding of the concepts being studied.

- To provide a theoretical basis: A conceptual framework can provide a theoretical basis for a research project by linking it to existing theories or conceptual models. This can help researchers build on previous research and contribute to the development of a field.

- To identify gaps in knowledge : A conceptual framework can help identify gaps in existing knowledge by highlighting areas that require further research or investigation.

- To communicate findings : A conceptual framework can be used to communicate research findings by providing a clear and concise summary of the key variables, relationships, and assumptions that underpin the research project.

Characteristics of Conceptual Framework

key characteristics of a conceptual framework are:

- Clear definition of key concepts : A conceptual framework should clearly define the key concepts and terms being used in a research project. This ensures that all researchers have a shared understanding of the concepts being studied.

- Identification of key variables: A conceptual framework should identify the key variables that are being studied and how they are related to each other. This helps to organize the research project and provides a clear focus for the study.

- Logical structure: A conceptual framework should have a logical structure that connects the key concepts and variables being studied. This helps to ensure that the research project is coherent and consistent.

- Based on existing theory : A conceptual framework should be based on existing theory or conceptual models. This helps to ensure that the research project is grounded in existing knowledge and builds on previous research.

- Testable hypotheses or research questions: A conceptual framework should include testable hypotheses or research questions that can be answered through empirical research. This helps to ensure that the research project is rigorous and scientifically valid.

- Flexibility : A conceptual framework should be flexible enough to allow for modifications as new information is gathered during the research process. This helps to ensure that the research project is responsive to new findings and is able to adapt to changing circumstances.

Advantages of Conceptual Framework

Advantages of the Conceptual Framework are as follows:

- Clarity : A conceptual framework provides clarity to researchers by outlining the key concepts and variables that are relevant to the research project. This clarity helps researchers to focus on the most important aspects of the research problem and develop a clear plan for investigating it.

- Direction : A conceptual framework provides direction to researchers by helping them to develop hypotheses or research questions that are grounded in existing theory or conceptual models. This direction ensures that the research project is relevant and contributes to the development of the field.

- Efficiency : A conceptual framework can increase efficiency in the research process by providing a structure for organizing ideas and data. This structure can help researchers to avoid redundancies and inconsistencies in their work, saving time and effort.

- Rigor : A conceptual framework can help to ensure the rigor of a research project by providing a theoretical basis for the investigation. This rigor is essential for ensuring that the research project is scientifically valid and produces meaningful results.

- Communication : A conceptual framework can facilitate communication between researchers by providing a shared language and understanding of the key concepts and variables being studied. This communication is essential for collaboration and the advancement of knowledge in the field.

- Generalization : A conceptual framework can help to generalize research findings beyond the specific study by providing a theoretical basis for the investigation. This generalization is essential for the development of knowledge in the field and for informing future research.

Limitations of Conceptual Framework

Limitations of Conceptual Framework are as follows:

- Limited applicability: Conceptual frameworks are often based on existing theory or conceptual models, which may not be applicable to all research problems or contexts. This can limit the usefulness of a conceptual framework in certain situations.

- Lack of empirical support : While a conceptual framework can provide a theoretical basis for a research project, it may not be supported by empirical evidence. This can limit the usefulness of a conceptual framework in guiding empirical research.

- Narrow focus: A conceptual framework can provide a clear focus for a research project, but it may also limit the scope of the investigation. This can make it difficult to address broader research questions or to consider alternative perspectives.

- Over-simplification: A conceptual framework can help to organize and structure research ideas, but it may also over-simplify complex phenomena. This can limit the depth of the investigation and the richness of the data collected.

- Inflexibility : A conceptual framework can provide a structure for organizing research ideas, but it may also be inflexible in the face of new data or unexpected findings. This can limit the ability of researchers to adapt their research project to new information or changing circumstances.

- Difficulty in development : Developing a conceptual framework can be a challenging and time-consuming process. It requires a thorough understanding of existing theory or conceptual models, and may require collaboration with other researchers.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Research Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

Survey Instruments – List and Their Uses

Appendix in Research Paper – Examples and...

References in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing...

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- CBE Life Sci Educ

- v.21(3); Fall 2022

Literature Reviews, Theoretical Frameworks, and Conceptual Frameworks: An Introduction for New Biology Education Researchers

Julie a. luft.

† Department of Mathematics, Social Studies, and Science Education, Mary Frances Early College of Education, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602-7124

Sophia Jeong

‡ Department of Teaching & Learning, College of Education & Human Ecology, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210

Robert Idsardi

§ Department of Biology, Eastern Washington University, Cheney, WA 99004

Grant Gardner

∥ Department of Biology, Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN 37132

Associated Data

To frame their work, biology education researchers need to consider the role of literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual frameworks as critical elements of the research and writing process. However, these elements can be confusing for scholars new to education research. This Research Methods article is designed to provide an overview of each of these elements and delineate the purpose of each in the educational research process. We describe what biology education researchers should consider as they conduct literature reviews, identify theoretical frameworks, and construct conceptual frameworks. Clarifying these different components of educational research studies can be helpful to new biology education researchers and the biology education research community at large in situating their work in the broader scholarly literature.

INTRODUCTION

Discipline-based education research (DBER) involves the purposeful and situated study of teaching and learning in specific disciplinary areas ( Singer et al. , 2012 ). Studies in DBER are guided by research questions that reflect disciplines’ priorities and worldviews. Researchers can use quantitative data, qualitative data, or both to answer these research questions through a variety of methodological traditions. Across all methodologies, there are different methods associated with planning and conducting educational research studies that include the use of surveys, interviews, observations, artifacts, or instruments. Ensuring the coherence of these elements to the discipline’s perspective also involves situating the work in the broader scholarly literature. The tools for doing this include literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual frameworks. However, the purpose and function of each of these elements is often confusing to new education researchers. The goal of this article is to introduce new biology education researchers to these three important elements important in DBER scholarship and the broader educational literature.

The first element we discuss is a review of research (literature reviews), which highlights the need for a specific research question, study problem, or topic of investigation. Literature reviews situate the relevance of the study within a topic and a field. The process may seem familiar to science researchers entering DBER fields, but new researchers may still struggle in conducting the review. Booth et al. (2016b) highlight some of the challenges novice education researchers face when conducting a review of literature. They point out that novice researchers struggle in deciding how to focus the review, determining the scope of articles needed in the review, and knowing how to be critical of the articles in the review. Overcoming these challenges (and others) can help novice researchers construct a sound literature review that can inform the design of the study and help ensure the work makes a contribution to the field.

The second and third highlighted elements are theoretical and conceptual frameworks. These guide biology education research (BER) studies, and may be less familiar to science researchers. These elements are important in shaping the construction of new knowledge. Theoretical frameworks offer a way to explain and interpret the studied phenomenon, while conceptual frameworks clarify assumptions about the studied phenomenon. Despite the importance of these constructs in educational research, biology educational researchers have noted the limited use of theoretical or conceptual frameworks in published work ( DeHaan, 2011 ; Dirks, 2011 ; Lo et al. , 2019 ). In reviewing articles published in CBE—Life Sciences Education ( LSE ) between 2015 and 2019, we found that fewer than 25% of the research articles had a theoretical or conceptual framework (see the Supplemental Information), and at times there was an inconsistent use of theoretical and conceptual frameworks. Clearly, these frameworks are challenging for published biology education researchers, which suggests the importance of providing some initial guidance to new biology education researchers.

Fortunately, educational researchers have increased their explicit use of these frameworks over time, and this is influencing educational research in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields. For instance, a quick search for theoretical or conceptual frameworks in the abstracts of articles in Educational Research Complete (a common database for educational research) in STEM fields demonstrates a dramatic change over the last 20 years: from only 778 articles published between 2000 and 2010 to 5703 articles published between 2010 and 2020, a more than sevenfold increase. Greater recognition of the importance of these frameworks is contributing to DBER authors being more explicit about such frameworks in their studies.

Collectively, literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual frameworks work to guide methodological decisions and the elucidation of important findings. Each offers a different perspective on the problem of study and is an essential element in all forms of educational research. As new researchers seek to learn about these elements, they will find different resources, a variety of perspectives, and many suggestions about the construction and use of these elements. The wide range of available information can overwhelm the new researcher who just wants to learn the distinction between these elements or how to craft them adequately.

Our goal in writing this paper is not to offer specific advice about how to write these sections in scholarly work. Instead, we wanted to introduce these elements to those who are new to BER and who are interested in better distinguishing one from the other. In this paper, we share the purpose of each element in BER scholarship, along with important points on its construction. We also provide references for additional resources that may be beneficial to better understanding each element. Table 1 summarizes the key distinctions among these elements.

Comparison of literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual reviews

| Literature reviews | Theoretical frameworks | Conceptual frameworks | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purpose | To point out the need for the study in BER and connection to the field. | To state the assumptions and orientations of the researcher regarding the topic of study | To describe the researcher’s understanding of the main concepts under investigation |

| Aims | A literature review examines current and relevant research associated with the study question. It is comprehensive, critical, and purposeful. | A theoretical framework illuminates the phenomenon of study and the corresponding assumptions adopted by the researcher. Frameworks can take on different orientations. | The conceptual framework is created by the researcher(s), includes the presumed relationships among concepts, and addresses needed areas of study discovered in literature reviews. |

| Connection to the manuscript | A literature review should connect to the study question, guide the study methodology, and be central in the discussion by indicating how the analyzed data advances what is known in the field. | A theoretical framework drives the question, guides the types of methods for data collection and analysis, informs the discussion of the findings, and reveals the subjectivities of the researcher. | The conceptual framework is informed by literature reviews, experiences, or experiments. It may include emergent ideas that are not yet grounded in the literature. It should be coherent with the paper’s theoretical framing. |

| Additional points | A literature review may reach beyond BER and include other education research fields. | A theoretical framework does not rationalize the need for the study, and a theoretical framework can come from different fields. | A conceptual framework articulates the phenomenon under study through written descriptions and/or visual representations. |

This article is written for the new biology education researcher who is just learning about these different elements or for scientists looking to become more involved in BER. It is a result of our own work as science education and biology education researchers, whether as graduate students and postdoctoral scholars or newly hired and established faculty members. This is the article we wish had been available as we started to learn about these elements or discussed them with new educational researchers in biology.

LITERATURE REVIEWS

Purpose of a literature review.

A literature review is foundational to any research study in education or science. In education, a well-conceptualized and well-executed review provides a summary of the research that has already been done on a specific topic and identifies questions that remain to be answered, thus illustrating the current research project’s potential contribution to the field and the reasoning behind the methodological approach selected for the study ( Maxwell, 2012 ). BER is an evolving disciplinary area that is redefining areas of conceptual emphasis as well as orientations toward teaching and learning (e.g., Labov et al. , 2010 ; American Association for the Advancement of Science, 2011 ; Nehm, 2019 ). As a result, building comprehensive, critical, purposeful, and concise literature reviews can be a challenge for new biology education researchers.

Building Literature Reviews

There are different ways to approach and construct a literature review. Booth et al. (2016a) provide an overview that includes, for example, scoping reviews, which are focused only on notable studies and use a basic method of analysis, and integrative reviews, which are the result of exhaustive literature searches across different genres. Underlying each of these different review processes are attention to the s earch process, a ppraisa l of articles, s ynthesis of the literature, and a nalysis: SALSA ( Booth et al. , 2016a ). This useful acronym can help the researcher focus on the process while building a specific type of review.

However, new educational researchers often have questions about literature reviews that are foundational to SALSA or other approaches. Common questions concern determining which literature pertains to the topic of study or the role of the literature review in the design of the study. This section addresses such questions broadly while providing general guidance for writing a narrative literature review that evaluates the most pertinent studies.

The literature review process should begin before the research is conducted. As Boote and Beile (2005 , p. 3) suggested, researchers should be “scholars before researchers.” They point out that having a good working knowledge of the proposed topic helps illuminate avenues of study. Some subject areas have a deep body of work to read and reflect upon, providing a strong foundation for developing the research question(s). For instance, the teaching and learning of evolution is an area of long-standing interest in the BER community, generating many studies (e.g., Perry et al. , 2008 ; Barnes and Brownell, 2016 ) and reviews of research (e.g., Sickel and Friedrichsen, 2013 ; Ziadie and Andrews, 2018 ). Emerging areas of BER include the affective domain, issues of transfer, and metacognition ( Singer et al. , 2012 ). Many studies in these areas are transdisciplinary and not always specific to biology education (e.g., Rodrigo-Peiris et al. , 2018 ; Kolpikova et al. , 2019 ). These newer areas may require reading outside BER; fortunately, summaries of some of these topics can be found in the Current Insights section of the LSE website.

In focusing on a specific problem within a broader research strand, a new researcher will likely need to examine research outside BER. Depending upon the area of study, the expanded reading list might involve a mix of BER, DBER, and educational research studies. Determining the scope of the reading is not always straightforward. A simple way to focus one’s reading is to create a “summary phrase” or “research nugget,” which is a very brief descriptive statement about the study. It should focus on the essence of the study, for example, “first-year nonmajor students’ understanding of evolution,” “metacognitive prompts to enhance learning during biochemistry,” or “instructors’ inquiry-based instructional practices after professional development programming.” This type of phrase should help a new researcher identify two or more areas to review that pertain to the study. Focusing on recent research in the last 5 years is a good first step. Additional studies can be identified by reading relevant works referenced in those articles. It is also important to read seminal studies that are more than 5 years old. Reading a range of studies should give the researcher the necessary command of the subject in order to suggest a research question.

Given that the research question(s) arise from the literature review, the review should also substantiate the selected methodological approach. The review and research question(s) guide the researcher in determining how to collect and analyze data. Often the methodological approach used in a study is selected to contribute knowledge that expands upon what has been published previously about the topic (see Institute of Education Sciences and National Science Foundation, 2013 ). An emerging topic of study may need an exploratory approach that allows for a description of the phenomenon and development of a potential theory. This could, but not necessarily, require a methodological approach that uses interviews, observations, surveys, or other instruments. An extensively studied topic may call for the additional understanding of specific factors or variables; this type of study would be well suited to a verification or a causal research design. These could entail a methodological approach that uses valid and reliable instruments, observations, or interviews to determine an effect in the studied event. In either of these examples, the researcher(s) may use a qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods methodological approach.

Even with a good research question, there is still more reading to be done. The complexity and focus of the research question dictates the depth and breadth of the literature to be examined. Questions that connect multiple topics can require broad literature reviews. For instance, a study that explores the impact of a biology faculty learning community on the inquiry instruction of faculty could have the following review areas: learning communities among biology faculty, inquiry instruction among biology faculty, and inquiry instruction among biology faculty as a result of professional learning. Biology education researchers need to consider whether their literature review requires studies from different disciplines within or outside DBER. For the example given, it would be fruitful to look at research focused on learning communities with faculty in STEM fields or in general education fields that result in instructional change. It is important not to be too narrow or too broad when reading. When the conclusions of articles start to sound similar or no new insights are gained, the researcher likely has a good foundation for a literature review. This level of reading should allow the researcher to demonstrate a mastery in understanding the researched topic, explain the suitability of the proposed research approach, and point to the need for the refined research question(s).

The literature review should include the researcher’s evaluation and critique of the selected studies. A researcher may have a large collection of studies, but not all of the studies will follow standards important in the reporting of empirical work in the social sciences. The American Educational Research Association ( Duran et al. , 2006 ), for example, offers a general discussion about standards for such work: an adequate review of research informing the study, the existence of sound and appropriate data collection and analysis methods, and appropriate conclusions that do not overstep or underexplore the analyzed data. The Institute of Education Sciences and National Science Foundation (2013) also offer Common Guidelines for Education Research and Development that can be used to evaluate collected studies.

Because not all journals adhere to such standards, it is important that a researcher review each study to determine the quality of published research, per the guidelines suggested earlier. In some instances, the research may be fatally flawed. Examples of such flaws include data that do not pertain to the question, a lack of discussion about the data collection, poorly constructed instruments, or an inadequate analysis. These types of errors result in studies that are incomplete, error-laden, or inaccurate and should be excluded from the review. Most studies have limitations, and the author(s) often make them explicit. For instance, there may be an instructor effect, recognized bias in the analysis, or issues with the sample population. Limitations are usually addressed by the research team in some way to ensure a sound and acceptable research process. Occasionally, the limitations associated with the study can be significant and not addressed adequately, which leaves a consequential decision in the hands of the researcher. Providing critiques of studies in the literature review process gives the reader confidence that the researcher has carefully examined relevant work in preparation for the study and, ultimately, the manuscript.

A solid literature review clearly anchors the proposed study in the field and connects the research question(s), the methodological approach, and the discussion. Reviewing extant research leads to research questions that will contribute to what is known in the field. By summarizing what is known, the literature review points to what needs to be known, which in turn guides decisions about methodology. Finally, notable findings of the new study are discussed in reference to those described in the literature review.

Within published BER studies, literature reviews can be placed in different locations in an article. When included in the introductory section of the study, the first few paragraphs of the manuscript set the stage, with the literature review following the opening paragraphs. Cooper et al. (2019) illustrate this approach in their study of course-based undergraduate research experiences (CUREs). An introduction discussing the potential of CURES is followed by an analysis of the existing literature relevant to the design of CUREs that allows for novel student discoveries. Within this review, the authors point out contradictory findings among research on novel student discoveries. This clarifies the need for their study, which is described and highlighted through specific research aims.

A literature reviews can also make up a separate section in a paper. For example, the introduction to Todd et al. (2019) illustrates the need for their research topic by highlighting the potential of learning progressions (LPs) and suggesting that LPs may help mitigate learning loss in genetics. At the end of the introduction, the authors state their specific research questions. The review of literature following this opening section comprises two subsections. One focuses on learning loss in general and examines a variety of studies and meta-analyses from the disciplines of medical education, mathematics, and reading. The second section focuses specifically on LPs in genetics and highlights student learning in the midst of LPs. These separate reviews provide insights into the stated research question.

Suggestions and Advice

A well-conceptualized, comprehensive, and critical literature review reveals the understanding of the topic that the researcher brings to the study. Literature reviews should not be so big that there is no clear area of focus; nor should they be so narrow that no real research question arises. The task for a researcher is to craft an efficient literature review that offers a critical analysis of published work, articulates the need for the study, guides the methodological approach to the topic of study, and provides an adequate foundation for the discussion of the findings.

In our own writing of literature reviews, there are often many drafts. An early draft may seem well suited to the study because the need for and approach to the study are well described. However, as the results of the study are analyzed and findings begin to emerge, the existing literature review may be inadequate and need revision. The need for an expanded discussion about the research area can result in the inclusion of new studies that support the explanation of a potential finding. The literature review may also prove to be too broad. Refocusing on a specific area allows for more contemplation of a finding.

It should be noted that there are different types of literature reviews, and many books and articles have been written about the different ways to embark on these types of reviews. Among these different resources, the following may be helpful in considering how to refine the review process for scholarly journals:

- Booth, A., Sutton, A., & Papaioannou, D. (2016a). Systemic approaches to a successful literature review (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. This book addresses different types of literature reviews and offers important suggestions pertaining to defining the scope of the literature review and assessing extant studies.

- Booth, W. C., Colomb, G. G., Williams, J. M., Bizup, J., & Fitzgerald, W. T. (2016b). The craft of research (4th ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. This book can help the novice consider how to make the case for an area of study. While this book is not specifically about literature reviews, it offers suggestions about making the case for your study.

- Galvan, J. L., & Galvan, M. C. (2017). Writing literature reviews: A guide for students of the social and behavioral sciences (7th ed.). Routledge. This book offers guidance on writing different types of literature reviews. For the novice researcher, there are useful suggestions for creating coherent literature reviews.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKS

Purpose of theoretical frameworks.

As new education researchers may be less familiar with theoretical frameworks than with literature reviews, this discussion begins with an analogy. Envision a biologist, chemist, and physicist examining together the dramatic effect of a fog tsunami over the ocean. A biologist gazing at this phenomenon may be concerned with the effect of fog on various species. A chemist may be interested in the chemical composition of the fog as water vapor condenses around bits of salt. A physicist may be focused on the refraction of light to make fog appear to be “sitting” above the ocean. While observing the same “objective event,” the scientists are operating under different theoretical frameworks that provide a particular perspective or “lens” for the interpretation of the phenomenon. Each of these scientists brings specialized knowledge, experiences, and values to this phenomenon, and these influence the interpretation of the phenomenon. The scientists’ theoretical frameworks influence how they design and carry out their studies and interpret their data.

Within an educational study, a theoretical framework helps to explain a phenomenon through a particular lens and challenges and extends existing knowledge within the limitations of that lens. Theoretical frameworks are explicitly stated by an educational researcher in the paper’s framework, theory, or relevant literature section. The framework shapes the types of questions asked, guides the method by which data are collected and analyzed, and informs the discussion of the results of the study. It also reveals the researcher’s subjectivities, for example, values, social experience, and viewpoint ( Allen, 2017 ). It is essential that a novice researcher learn to explicitly state a theoretical framework, because all research questions are being asked from the researcher’s implicit or explicit assumptions of a phenomenon of interest ( Schwandt, 2000 ).

Selecting Theoretical Frameworks

Theoretical frameworks are one of the most contemplated elements in our work in educational research. In this section, we share three important considerations for new scholars selecting a theoretical framework.

The first step in identifying a theoretical framework involves reflecting on the phenomenon within the study and the assumptions aligned with the phenomenon. The phenomenon involves the studied event. There are many possibilities, for example, student learning, instructional approach, or group organization. A researcher holds assumptions about how the phenomenon will be effected, influenced, changed, or portrayed. It is ultimately the researcher’s assumption(s) about the phenomenon that aligns with a theoretical framework. An example can help illustrate how a researcher’s reflection on the phenomenon and acknowledgment of assumptions can result in the identification of a theoretical framework.

In our example, a biology education researcher may be interested in exploring how students’ learning of difficult biological concepts can be supported by the interactions of group members. The phenomenon of interest is the interactions among the peers, and the researcher assumes that more knowledgeable students are important in supporting the learning of the group. As a result, the researcher may draw on Vygotsky’s (1978) sociocultural theory of learning and development that is focused on the phenomenon of student learning in a social setting. This theory posits the critical nature of interactions among students and between students and teachers in the process of building knowledge. A researcher drawing upon this framework holds the assumption that learning is a dynamic social process involving questions and explanations among students in the classroom and that more knowledgeable peers play an important part in the process of building conceptual knowledge.

It is important to state at this point that there are many different theoretical frameworks. Some frameworks focus on learning and knowing, while other theoretical frameworks focus on equity, empowerment, or discourse. Some frameworks are well articulated, and others are still being refined. For a new researcher, it can be challenging to find a theoretical framework. Two of the best ways to look for theoretical frameworks is through published works that highlight different frameworks.

When a theoretical framework is selected, it should clearly connect to all parts of the study. The framework should augment the study by adding a perspective that provides greater insights into the phenomenon. It should clearly align with the studies described in the literature review. For instance, a framework focused on learning would correspond to research that reported different learning outcomes for similar studies. The methods for data collection and analysis should also correspond to the framework. For instance, a study about instructional interventions could use a theoretical framework concerned with learning and could collect data about the effect of the intervention on what is learned. When the data are analyzed, the theoretical framework should provide added meaning to the findings, and the findings should align with the theoretical framework.

A study by Jensen and Lawson (2011) provides an example of how a theoretical framework connects different parts of the study. They compared undergraduate biology students in heterogeneous and homogeneous groups over the course of a semester. Jensen and Lawson (2011) assumed that learning involved collaboration and more knowledgeable peers, which made Vygotsky’s (1978) theory a good fit for their study. They predicted that students in heterogeneous groups would experience greater improvement in their reasoning abilities and science achievements with much of the learning guided by the more knowledgeable peers.

In the enactment of the study, they collected data about the instruction in traditional and inquiry-oriented classes, while the students worked in homogeneous or heterogeneous groups. To determine the effect of working in groups, the authors also measured students’ reasoning abilities and achievement. Each data-collection and analysis decision connected to understanding the influence of collaborative work.

Their findings highlighted aspects of Vygotsky’s (1978) theory of learning. One finding, for instance, posited that inquiry instruction, as a whole, resulted in reasoning and achievement gains. This links to Vygotsky (1978) , because inquiry instruction involves interactions among group members. A more nuanced finding was that group composition had a conditional effect. Heterogeneous groups performed better with more traditional and didactic instruction, regardless of the reasoning ability of the group members. Homogeneous groups worked better during interaction-rich activities for students with low reasoning ability. The authors attributed the variation to the different types of helping behaviors of students. High-performing students provided the answers, while students with low reasoning ability had to work collectively through the material. In terms of Vygotsky (1978) , this finding provided new insights into the learning context in which productive interactions can occur for students.

Another consideration in the selection and use of a theoretical framework pertains to its orientation to the study. This can result in the theoretical framework prioritizing individuals, institutions, and/or policies ( Anfara and Mertz, 2014 ). Frameworks that connect to individuals, for instance, could contribute to understanding their actions, learning, or knowledge. Institutional frameworks, on the other hand, offer insights into how institutions, organizations, or groups can influence individuals or materials. Policy theories provide ways to understand how national or local policies can dictate an emphasis on outcomes or instructional design. These different types of frameworks highlight different aspects in an educational setting, which influences the design of the study and the collection of data. In addition, these different frameworks offer a way to make sense of the data. Aligning the data collection and analysis with the framework ensures that a study is coherent and can contribute to the field.

New understandings emerge when different theoretical frameworks are used. For instance, Ebert-May et al. (2015) prioritized the individual level within conceptual change theory (see Posner et al. , 1982 ). In this theory, an individual’s knowledge changes when it no longer fits the phenomenon. Ebert-May et al. (2015) designed a professional development program challenging biology postdoctoral scholars’ existing conceptions of teaching. The authors reported that the biology postdoctoral scholars’ teaching practices became more student-centered as they were challenged to explain their instructional decision making. According to the theory, the biology postdoctoral scholars’ dissatisfaction in their descriptions of teaching and learning initiated change in their knowledge and instruction. These results reveal how conceptual change theory can explain the learning of participants and guide the design of professional development programming.

The communities of practice (CoP) theoretical framework ( Lave, 1988 ; Wenger, 1998 ) prioritizes the institutional level , suggesting that learning occurs when individuals learn from and contribute to the communities in which they reside. Grounded in the assumption of community learning, the literature on CoP suggests that, as individuals interact regularly with the other members of their group, they learn about the rules, roles, and goals of the community ( Allee, 2000 ). A study conducted by Gehrke and Kezar (2017) used the CoP framework to understand organizational change by examining the involvement of individual faculty engaged in a cross-institutional CoP focused on changing the instructional practice of faculty at each institution. In the CoP, faculty members were involved in enhancing instructional materials within their department, which aligned with an overarching goal of instituting instruction that embraced active learning. Not surprisingly, Gehrke and Kezar (2017) revealed that faculty who perceived the community culture as important in their work cultivated institutional change. Furthermore, they found that institutional change was sustained when key leaders served as mentors and provided support for faculty, and as faculty themselves developed into leaders. This study reveals the complexity of individual roles in a COP in order to support institutional instructional change.

It is important to explicitly state the theoretical framework used in a study, but elucidating a theoretical framework can be challenging for a new educational researcher. The literature review can help to identify an applicable theoretical framework. Focal areas of the review or central terms often connect to assumptions and assertions associated with the framework that pertain to the phenomenon of interest. Another way to identify a theoretical framework is self-reflection by the researcher on personal beliefs and understandings about the nature of knowledge the researcher brings to the study ( Lysaght, 2011 ). In stating one’s beliefs and understandings related to the study (e.g., students construct their knowledge, instructional materials support learning), an orientation becomes evident that will suggest a particular theoretical framework. Theoretical frameworks are not arbitrary , but purposefully selected.

With experience, a researcher may find expanded roles for theoretical frameworks. Researchers may revise an existing framework that has limited explanatory power, or they may decide there is a need to develop a new theoretical framework. These frameworks can emerge from a current study or the need to explain a phenomenon in a new way. Researchers may also find that multiple theoretical frameworks are necessary to frame and explore a problem, as different frameworks can provide different insights into a problem.

Finally, it is important to recognize that choosing “x” theoretical framework does not necessarily mean a researcher chooses “y” methodology and so on, nor is there a clear-cut, linear process in selecting a theoretical framework for one’s study. In part, the nonlinear process of identifying a theoretical framework is what makes understanding and using theoretical frameworks challenging. For the novice scholar, contemplating and understanding theoretical frameworks is essential. Fortunately, there are articles and books that can help:

- Creswell, J. W. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. This book provides an overview of theoretical frameworks in general educational research.

- Ding, L. (2019). Theoretical perspectives of quantitative physics education research. Physical Review Physics Education Research , 15 (2), 020101-1–020101-13. This paper illustrates how a DBER field can use theoretical frameworks.

- Nehm, R. (2019). Biology education research: Building integrative frameworks for teaching and learning about living systems. Disciplinary and Interdisciplinary Science Education Research , 1 , ar15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43031-019-0017-6 . This paper articulates the need for studies in BER to explicitly state theoretical frameworks and provides examples of potential studies.

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice . Sage. This book also provides an overview of theoretical frameworks, but for both research and evaluation.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORKS

Purpose of a conceptual framework.

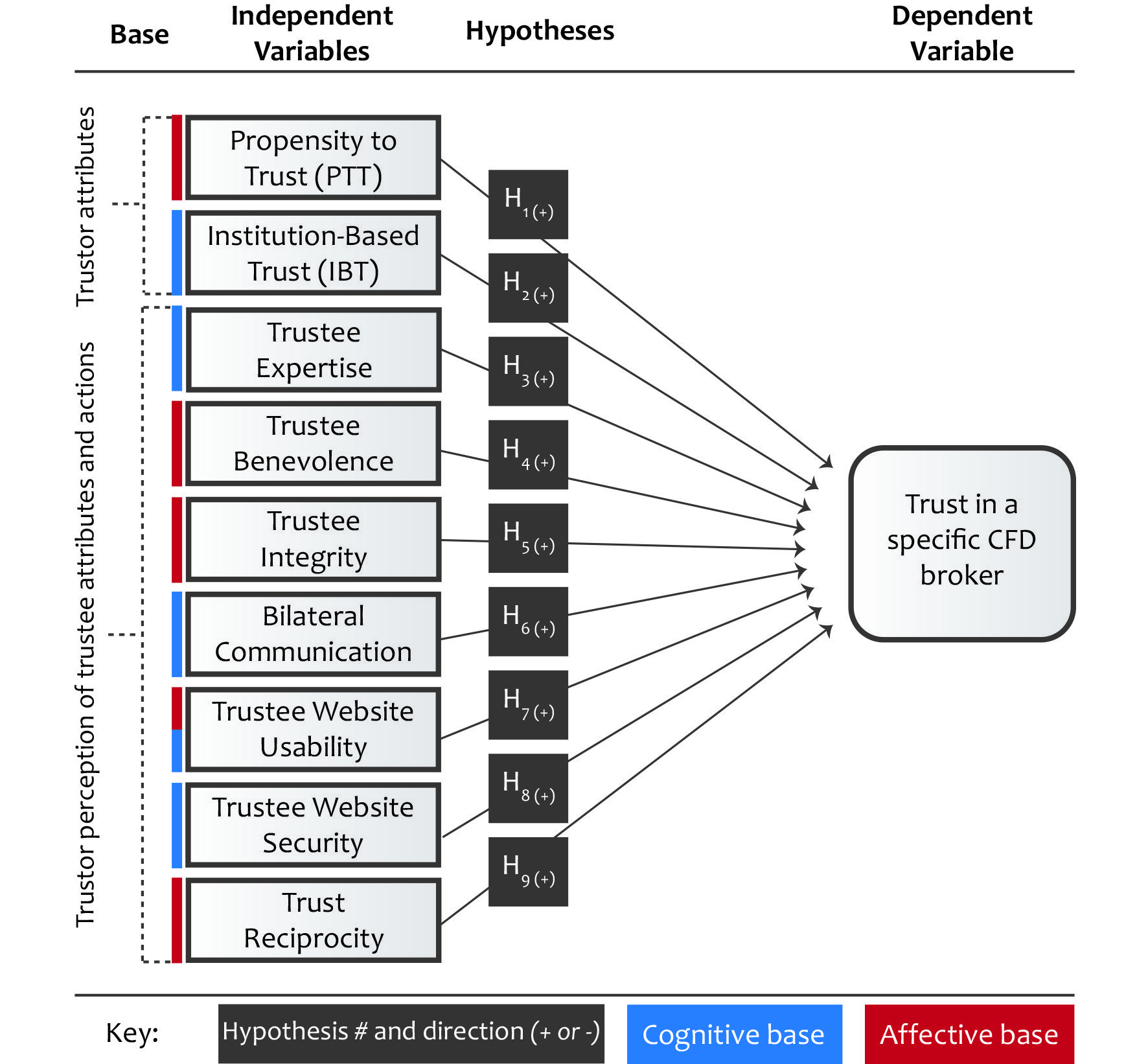

A conceptual framework is a description of the way a researcher understands the factors and/or variables that are involved in the study and their relationships to one another. The purpose of a conceptual framework is to articulate the concepts under study using relevant literature ( Rocco and Plakhotnik, 2009 ) and to clarify the presumed relationships among those concepts ( Rocco and Plakhotnik, 2009 ; Anfara and Mertz, 2014 ). Conceptual frameworks are different from theoretical frameworks in both their breadth and grounding in established findings. Whereas a theoretical framework articulates the lens through which a researcher views the work, the conceptual framework is often more mechanistic and malleable.

Conceptual frameworks are broader, encompassing both established theories (i.e., theoretical frameworks) and the researchers’ own emergent ideas. Emergent ideas, for example, may be rooted in informal and/or unpublished observations from experience. These emergent ideas would not be considered a “theory” if they are not yet tested, supported by systematically collected evidence, and peer reviewed. However, they do still play an important role in the way researchers approach their studies. The conceptual framework allows authors to clearly describe their emergent ideas so that connections among ideas in the study and the significance of the study are apparent to readers.

Constructing Conceptual Frameworks

Including a conceptual framework in a research study is important, but researchers often opt to include either a conceptual or a theoretical framework. Either may be adequate, but both provide greater insight into the research approach. For instance, a research team plans to test a novel component of an existing theory. In their study, they describe the existing theoretical framework that informs their work and then present their own conceptual framework. Within this conceptual framework, specific topics portray emergent ideas that are related to the theory. Describing both frameworks allows readers to better understand the researchers’ assumptions, orientations, and understanding of concepts being investigated. For example, Connolly et al. (2018) included a conceptual framework that described how they applied a theoretical framework of social cognitive career theory (SCCT) to their study on teaching programs for doctoral students. In their conceptual framework, the authors described SCCT, explained how it applied to the investigation, and drew upon results from previous studies to justify the proposed connections between the theory and their emergent ideas.

In some cases, authors may be able to sufficiently describe their conceptualization of the phenomenon under study in an introduction alone, without a separate conceptual framework section. However, incomplete descriptions of how the researchers conceptualize the components of the study may limit the significance of the study by making the research less intelligible to readers. This is especially problematic when studying topics in which researchers use the same terms for different constructs or different terms for similar and overlapping constructs (e.g., inquiry, teacher beliefs, pedagogical content knowledge, or active learning). Authors must describe their conceptualization of a construct if the research is to be understandable and useful.

There are some key areas to consider regarding the inclusion of a conceptual framework in a study. To begin with, it is important to recognize that conceptual frameworks are constructed by the researchers conducting the study ( Rocco and Plakhotnik, 2009 ; Maxwell, 2012 ). This is different from theoretical frameworks that are often taken from established literature. Researchers should bring together ideas from the literature, but they may be influenced by their own experiences as a student and/or instructor, the shared experiences of others, or thought experiments as they construct a description, model, or representation of their understanding of the phenomenon under study. This is an exercise in intellectual organization and clarity that often considers what is learned, known, and experienced. The conceptual framework makes these constructs explicitly visible to readers, who may have different understandings of the phenomenon based on their prior knowledge and experience. There is no single method to go about this intellectual work.

Reeves et al. (2016) is an example of an article that proposed a conceptual framework about graduate teaching assistant professional development evaluation and research. The authors used existing literature to create a novel framework that filled a gap in current research and practice related to the training of graduate teaching assistants. This conceptual framework can guide the systematic collection of data by other researchers because the framework describes the relationships among various factors that influence teaching and learning. The Reeves et al. (2016) conceptual framework may be modified as additional data are collected and analyzed by other researchers. This is not uncommon, as conceptual frameworks can serve as catalysts for concerted research efforts that systematically explore a phenomenon (e.g., Reynolds et al. , 2012 ; Brownell and Kloser, 2015 ).

Sabel et al. (2017) used a conceptual framework in their exploration of how scaffolds, an external factor, interact with internal factors to support student learning. Their conceptual framework integrated principles from two theoretical frameworks, self-regulated learning and metacognition, to illustrate how the research team conceptualized students’ use of scaffolds in their learning ( Figure 1 ). Sabel et al. (2017) created this model using their interpretations of these two frameworks in the context of their teaching.

Conceptual framework from Sabel et al. (2017) .

A conceptual framework should describe the relationship among components of the investigation ( Anfara and Mertz, 2014 ). These relationships should guide the researcher’s methods of approaching the study ( Miles et al. , 2014 ) and inform both the data to be collected and how those data should be analyzed. Explicitly describing the connections among the ideas allows the researcher to justify the importance of the study and the rigor of the research design. Just as importantly, these frameworks help readers understand why certain components of a system were not explored in the study. This is a challenge in education research, which is rooted in complex environments with many variables that are difficult to control.

For example, Sabel et al. (2017) stated: “Scaffolds, such as enhanced answer keys and reflection questions, can help students and instructors bridge the external and internal factors and support learning” (p. 3). They connected the scaffolds in the study to the three dimensions of metacognition and the eventual transformation of existing ideas into new or revised ideas. Their framework provides a rationale for focusing on how students use two different scaffolds, and not on other factors that may influence a student’s success (self-efficacy, use of active learning, exam format, etc.).

In constructing conceptual frameworks, researchers should address needed areas of study and/or contradictions discovered in literature reviews. By attending to these areas, researchers can strengthen their arguments for the importance of a study. For instance, conceptual frameworks can address how the current study will fill gaps in the research, resolve contradictions in existing literature, or suggest a new area of study. While a literature review describes what is known and not known about the phenomenon, the conceptual framework leverages these gaps in describing the current study ( Maxwell, 2012 ). In the example of Sabel et al. (2017) , the authors indicated there was a gap in the literature regarding how scaffolds engage students in metacognition to promote learning in large classes. Their study helps fill that gap by describing how scaffolds can support students in the three dimensions of metacognition: intelligibility, plausibility, and wide applicability. In another example, Lane (2016) integrated research from science identity, the ethic of care, the sense of belonging, and an expertise model of student success to form a conceptual framework that addressed the critiques of other frameworks. In a more recent example, Sbeglia et al. (2021) illustrated how a conceptual framework influences the methodological choices and inferences in studies by educational researchers.

Sometimes researchers draw upon the conceptual frameworks of other researchers. When a researcher’s conceptual framework closely aligns with an existing framework, the discussion may be brief. For example, Ghee et al. (2016) referred to portions of SCCT as their conceptual framework to explain the significance of their work on students’ self-efficacy and career interests. Because the authors’ conceptualization of this phenomenon aligned with a previously described framework, they briefly mentioned the conceptual framework and provided additional citations that provided more detail for the readers.

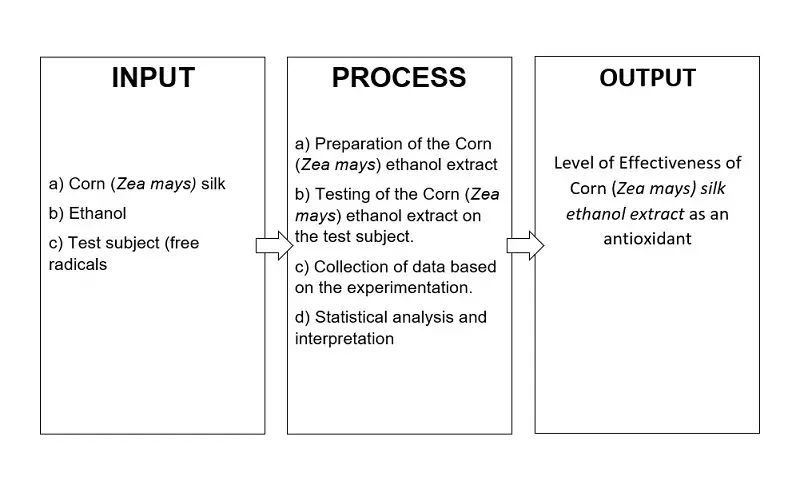

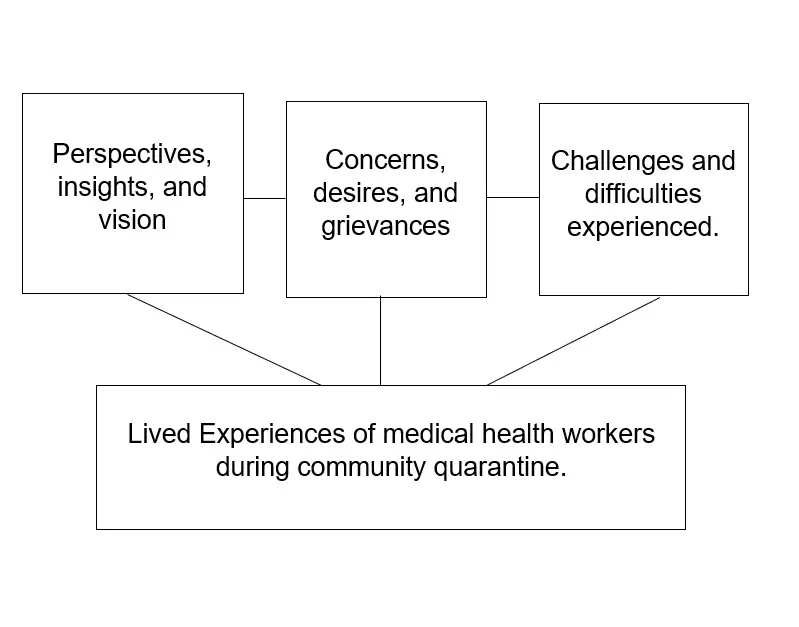

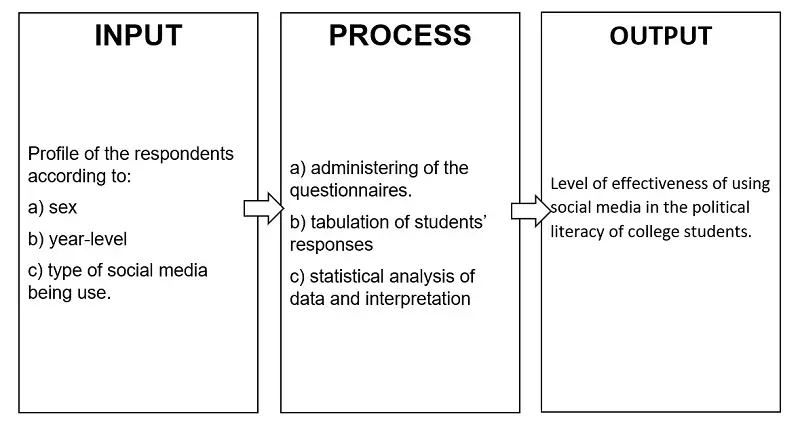

Within both the BER and the broader DBER communities, conceptual frameworks have been used to describe different constructs. For example, some researchers have used the term “conceptual framework” to describe students’ conceptual understandings of a biological phenomenon. This is distinct from a researcher’s conceptual framework of the educational phenomenon under investigation, which may also need to be explicitly described in the article. Other studies have presented a research logic model or flowchart of the research design as a conceptual framework. These constructions can be quite valuable in helping readers understand the data-collection and analysis process. However, a model depicting the study design does not serve the same role as a conceptual framework. Researchers need to avoid conflating these constructs by differentiating the researchers’ conceptual framework that guides the study from the research design, when applicable.

Explicitly describing conceptual frameworks is essential in depicting the focus of the study. We have found that being explicit in a conceptual framework means using accepted terminology, referencing prior work, and clearly noting connections between terms. This description can also highlight gaps in the literature or suggest potential contributions to the field of study. A well-elucidated conceptual framework can suggest additional studies that may be warranted. This can also spur other researchers to consider how they would approach the examination of a phenomenon and could result in a revised conceptual framework.

It can be challenging to create conceptual frameworks, but they are important. Below are two resources that could be helpful in constructing and presenting conceptual frameworks in educational research:

- Maxwell, J. A. (2012). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. Chapter 3 in this book describes how to construct conceptual frameworks.

- Ravitch, S. M., & Riggan, M. (2016). Reason & rigor: How conceptual frameworks guide research . Los Angeles, CA: Sage. This book explains how conceptual frameworks guide the research questions, data collection, data analyses, and interpretation of results.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS