Which program are you applying to?

Accepted Admissions Blog

Everything you need to know to get Accepted

May 8, 2024

The Diversity Essay: How to Write an Excellent Diversity Essay

What is a diversity essay in a school application? And why does it matter when applying to leading programs and universities? Most importantly, how should you go about writing such an essay?

Diversity is of supreme value in higher education, and schools want to know how every student will contribute to the diversity on their campus. A diversity essay gives applicants with disadvantaged or underrepresented backgrounds, an unusual education, a distinctive experience, or a unique family history an opportunity to write about how these elements of their background have prepared them to play a useful role in increasing and encouraging diversity among their target program’s student body and broader community.

The purpose of all application essays is to help the adcom better understand who an applicant is and what they care about. Your essays are your chance to share your voice and humanize your application. This is especially true for the diversity essay, which aims to reveal your unique perspectives and experiences, as well as the ways in which you might contribute to a college community.

In this post, we’ll discuss what exactly a diversity essay is, look at examples of actual prompts and a sample essay, and offer tips for writing a standout essay.

In this post, you’ll find the following:

What a diversity essay covers

How to show you can add to a school’s diversity, why diversity matters to schools.

- Seven examples that reveal diversity

Sample diversity essay prompts

How to write about your diversity.

- A diversity essay example

Upon hearing the word “diversity” in relation to an application essay, many people assume that they will have to write about gender, sexuality, class, or race. To many, this can feel overly personal or irrelevant, and some students might worry that their identity isn’t unique or interesting enough. In reality, the diversity essay is much broader than many people realize.

Identity means different things to different people. The important thing is that you demonstrate your uniqueness and what matters to you. In addition to writing about one of the traditional identity features we just mentioned (gender, sexuality, class, race), you could consider writing about a more unusual feature of yourself or your life – or even the intersection of two or more identities.

Consider these questions as you think about what to include in your diversity essay:

- Do you have a unique or unusual talent or skill?

- Do you have beliefs or values that are markedly different from those of the people around you?

- Do you have a hobby or interest that sets you apart from your peers?

- Have you done or experienced something that few people have? Note that if you choose to write about a single event as a diverse identity feature, that event needs to have had a pretty substantial impact on you and your life. For example, perhaps you’re part of the 0.2% of the world’s population that has run a marathon, or you’ve had the chance to watch wolves hunt in the wild.

- Do you have a role in life that gives you a special outlook on the world? For example, maybe one of your siblings has a rare disability, or you grew up in a town with fewer than 500 inhabitants.

If you are an immigrant to the United States, the child of immigrants, or someone whose ethnicity is underrepresented in the States, your response to “How will you add to the diversity of our class/community?” and similar questions might help your application efforts. Why? Because you have the opportunity to show the adcom how your background will contribute a distinctive perspective to the program you are applying to.

Of course, if you’re not underrepresented in your field or part of a disadvantaged group, that doesn’t mean that you don’t have anything to write about in a diversity essay.

For example, you might have an unusual or special experience to share, such as serving in the military, being a member of a dance troupe, or caring for a disabled relative. These and other distinctive experiences can convey how you will contribute to the diversity of the school’s campus.

Maybe you are the first member of your family to apply to college or the first person in your household to learn English. Perhaps you have worked your way through college or helped raise your siblings. You might also have been an ally to those who are underrepresented, disadvantaged, or marginalized in your community, at your school, or in a work setting.

As you can see, diversity is not limited to one’s religion, ethnicity, culture, language, or sexual orientation. It refers to whatever element of your identity distinguishes you from others and shows that you, too, value diversity.

The diversity essay provides colleges the chance to build a student body that includes different ethnicities, religions, sexual orientations, backgrounds, interests, and so on. Applicants are asked to illuminate what sets them apart so that the adcoms can see what kind of diverse views and opinions they can bring to the campus.

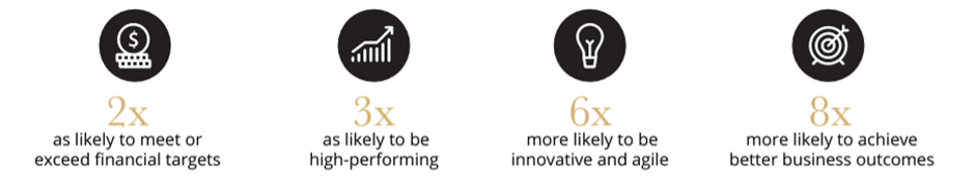

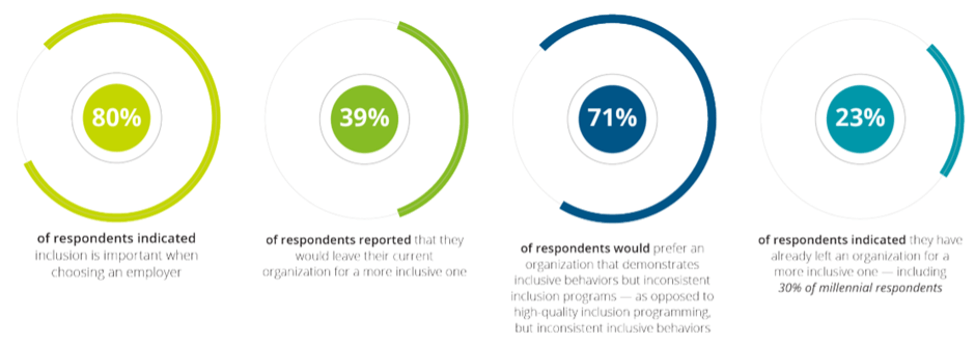

Admissions officers believe that diversity in the classroom improves the educational experience of all the students involved. They also believe that having a diverse workforce better serves society as a whole.

The more diverse perspectives found in the classroom, throughout the dorms, in the dining halls, and mixed into study groups, the richer people’s discussions will be.

Plus, learning and growing in this kind of multicultural environment will prepare students for working in our increasingly multicultural and global world.

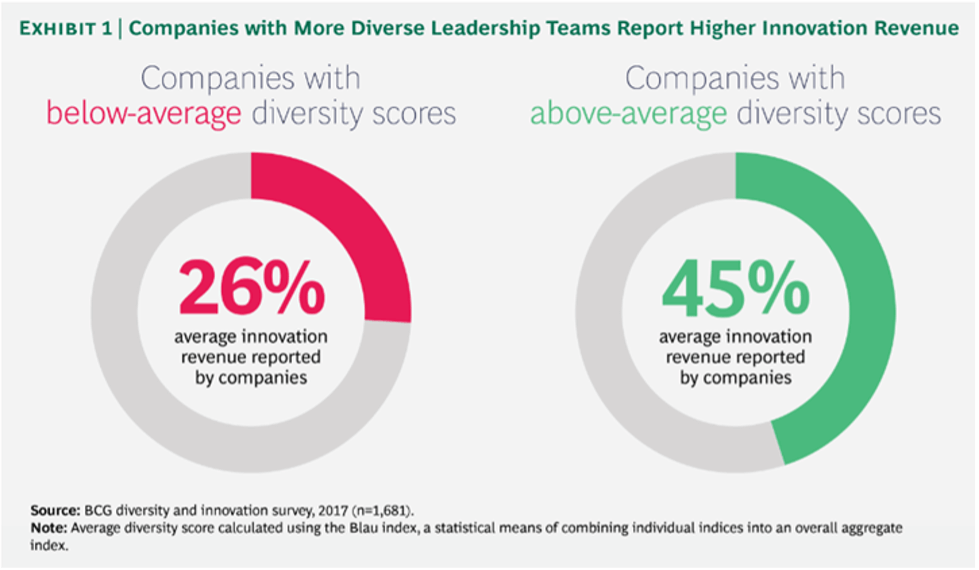

In medicine, for example, a heterogeneous workforce benefits people from previously underrepresented cultures. Businesses realize that they will market more effectively if they can speak to different audiences, which is possible when members of their workforce come from various backgrounds and cultures. Schools simply want to prepare graduates for the 21st century job market.

Seven examples that reveal diversity

Adcoms want to know about the diverse elements of your character and how these have helped you develop particular personality traits , as well as about any unusual experiences that have shaped you.

Here are seven examples an applicant could write about:

1. They grew up in an environment with a strong emphasis on respecting their elders, attending family events, and/or learning their parents’ native language and culture.

2. They are close to their grandparents and extended family members who have taught them how teamwork can help everyone thrive.

3. They have had to face difficulties that stem from their parents’ values being in conflict with theirs or those of their peers.

4. Teachers have not always understood the elements of their culture or lifestyle and how those elements influence their performance.

5. They have suffered discrimination and succeeded despite it because of their grit, values, and character.

6. They learned skills from a lifestyle that is outside the norm (e.g., living in foreign countries as the child of a diplomat or contractor; performing professionally in theater, dance, music, or sports; having a deaf sibling).

7. They’ve encountered racism or other prejudice (either toward themselves or others) and responded by actively promoting diverse, tolerant values.

And remember, diversity is not about who your parents are. It’s about who you are – at the core.

Your background, influences, religious observances, native language, ideas, work environment, community experiences – all these factors come together to create a unique individual, one who will contribute to a varied class of distinct individuals taking their place in a diverse world.

The best-known diversity essay prompt is from the Common App . It states:

“Some students have a background, identity, interest, or talent that is so meaningful they believe their application would be incomplete without it. If this sounds like you, then please share your story.”

Some schools have individual diversity essay prompts. For example, this one is from Duke University :

“We believe a wide range of personal perspectives, beliefs, and lived experiences are essential to making Duke a vibrant and meaningful living and learning community. Feel free to share with us anything in this context that might help us better understand you and what you might bring to our community.”

And the Rice University application includes the following prompt:

“Rice is strengthened by its diverse community of learning and discovery that produces leaders and change agents across the spectrum of human endeavor. What perspectives shaped by your background, experiences, upbringing, and/or racial identity inspire you to join our community of change agents at Rice?”

In all instances, colleges want you to demonstrate how and what you’ll contribute to their communities.

Your answer to a school’s diversity essay question should focus on how your experiences have built your empathy for others, your embrace of differences, your resilience, your character, and your perspective.

The school might ask how you think of diversity or how you will bring or add to the diversity of the school, your chosen profession, or your community. Make sure you answer the specific question posed by highlighting distinctive elements of your profile that will add to the class mosaic every adcom is trying to create. You don’t want to blend in; you want to stand out in a positive way while also complementing the school’s canvas.

Here’s a simple, three-part framework that will help you think of diversity more broadly:

Who are you? What has contributed to your identity? How do you distinguish yourself? Your identity can include any of the following: gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, disability, religion, nontraditional work experience, nontraditional educational background, multicultural background, and family’s educational level.

What have you done? What have you accomplished? This could include any of the following: achievements inside and/or outside your field of study, leadership opportunities, community service, internship or professional experience, research opportunities, hobbies, and travel. Any or all of these could be unique. Also, what life-derailing, throw-you-for-a-loop challenges have you faced and overcome?

How do you think? How do you approach things? What drives you? What influences you? Are you the person who can break up a tense meeting with some well-timed humor? Are you the one who intuitively sees how to bring people together?

Read more about this three-part framework in Episode 193 of Accepted’s Admissions Straight Talk podcast or listen wherever you get your favorite podcast s.

Think about each question within this framework and how you could apply your diversity elements to your target school’s classroom or community. Any of these elements can serve as the framework for your essay.

Don’t worry if you can’t think of something totally “out there.” You don’t need to be a tightrope walker living in the Andes or a Buddhist monk from Japan to be able to contribute to a school’s diversity!

And please remember, the examples we have offered here are not exhaustive. There are many other ways to show diversity!

All you need to do to be able to write successfully about how you will contribute to the diversity of your target school’s community is examine your identity, deeds, and ideas, with an eye toward your personal distinctiveness and individuality. There is only one you .

Take a look at the sample diversity essay in the next section of this post, and pay attention to how the writer underscores their appreciation for, and experience with, diversity.

A diversity essay sample

When I was starting 11th grade, my dad, an agricultural scientist, was assigned to a 3-month research project in a farm village in Niigata (northwest Honshu in Japan). Rather than stay behind with my mom and siblings, I begged to go with him. As a straight-A student, I convinced my parents and the principal that I could handle my schoolwork remotely (pre-COVID) for that stretch. It was time to leap beyond my comfortable suburban Wisconsin life—and my Western orientation, reinforced by travel to Europe the year before.

We roomed in a sprawling farmhouse with a family participating in my dad’s study. I thought I’d experience an “English-free zone,” but the high school students all studied and wanted to practice English, so I did meet peers even though I didn’t attend their school. Of the many eye-opening, influential, cultural experiences, the one that resonates most powerfully to me is experiencing their community. It was a living, organic whole. Elementary school kids spent time helping with the rice harvest. People who foraged for seasonal wild edibles gave them to acquaintances throughout the town. In fact, there was a constant sharing of food among residents—garden veggies carried in straw baskets, fish or meat in coolers. The pharmacist would drive prescriptions to people who couldn’t easily get out—new mothers, the elderly—not as a business service but as a good neighbor. If rain suddenly threatened, neighbors would bring in each other’s drying laundry. When an empty-nest 50-year-old woman had to be hospitalized suddenly for a near-fatal snakebite, neighbors maintained her veggie patch until she returned. The community embodied constant awareness of others’ needs and circumstances. The community flowed!

Yet, people there lamented that this lifestyle was vanishing; more young people left than stayed or came. And it wasn’t idyllic: I heard about ubiquitous gossip, long-standing personal enmities, busybody-ness. But these very human foibles didn’t dam the flow. This dynamic community organism couldn’t have been more different from my suburban life back home, with its insular nuclear families. We nod hello to neighbors in passing.

This wonderful experience contained a personal challenge. Blond and blue-eyed, I became “the other” for the first time. Except for my dad, I saw no Westerner there. Curious eyes followed me. Stepping into a market or walking down the street, I drew gazes. People swiftly looked away if they accidentally caught my eye. It was not at all hostile, I knew, but I felt like an object. I began making extra sure to appear “presentable” before going outside. The sense of being watched sometimes generated mild stress or resentment. Returning to my lovely tatami room, I would decompress, grateful to be alone. I realized this challenge was a minute fraction of what others experience in my own country. The toll that feeling—and being— “other” takes on non-white and visibly different people in the US can be extremely painful. Experiencing it firsthand, albeit briefly, benignly, and in relative comfort, I got it.

Unlike the organic Niigata community, work teams, and the workplace itself, have externally driven purposes. Within this different environment, I will strive to exemplify the ongoing mutual awareness that fueled the community life in Niigata. Does it benefit the bottom line, improve the results? I don’t know. But it helps me be the mature, engaged person I want to be, and to appreciate the individuals who are my colleagues and who comprise my professional community. I am now far more conscious of people feeling their “otherness”—even when it’s not in response to negative treatment, it can arise simply from awareness of being in some way different.

What did you think of this essay? Does this middle class Midwesterner have the unique experience of being different from the surrounding majority, something she had not experienced in the United States? Did she encounter diversity from the perspective of “the other”?

Here a few things to note about why this diversity essay works so well:

1. The writer comes from “a comfortable, suburban, Wisconsin life,” suggesting that her background might not be ethnically, racially, or in any other way diverse.

2. The diversity “points” scored all come from her fascinating experience of having lived in a Japanese farm village, where she immersed herself in a totally different culture.

3. The lessons learned about the meaning of community are what broaden and deepen the writer’s perspective about life, about a purpose-driven life, and about the concept of “otherness.”

By writing about a time when you experienced diversity in one of its many forms, you can write a memorable and meaningful diversity essay.

Working on your diversity essay?

Want to ensure that your application demonstrates the diversity that your dream school is seeking? Work with one of our admissions experts . This checklist includes more than 30 different ways to think about diversity to jump-start your creative engine.

Dr. Sundas Ali has more than 15 years of experience teaching and advising students, providing career and admissions advice, reviewing applications, and conducting interviews for the University of Oxford’s undergraduate and graduate programs. In addition, Sundas has worked with students from a wide range of countries, including the United Kingdom, the United States, India, Pakistan, China, Japan, and the Middle East. Want Sundas to help you get Accepted? Click here to get in touch!

Related Resources:

- Different Dimensions of Diversity , podcast Episode 193

- What Should You Do If You Belong to an Overrepresented MBA Applicant Group?

- Fitting In & Standing Out: The Paradox at the Heart of Admissions , a free guide

About Us Press Room Contact Us Podcast Accepted Blog Privacy Policy Website Terms of Use Disclaimer Client Terms of Service

Accepted 1171 S. Robertson Blvd. #140 Los Angeles CA 90035 +1 (310) 815-9553 © 2022 Accepted

Are you seeking one-on-one college counseling and/or essay support? Limited spots are now available. Click here to learn more.

How to Write the Diversity Essay – With Examples

May 1, 2024

The diversity essay has newfound significance in college application packages following the 2023 SCOTUS ruling against race-conscious admissions. Affirmative action began as an attempt to redress unequal access to economic and social mobility associated with higher education. But before the 2023 ruling, colleges frequently defended the policy based on their “compelling interest” in fostering diverse campuses. The reasoning goes that there are certain educational benefits that come from heterogeneous learning environments. Now, the diversity essay has become key for admissions officials in achieving their compelling interest in campus diversity. Thus, unlocking how to write a diversity essay enhances an applicant’s ability to describe their fit with a campus environment. This article describes the genre and provides diversity essay examples to help any applicant express how they conceptualize and contribute to diversity.

How to Write a Diversity Essay – Defining the Genre

Diversity essays in many ways resemble the personal statement genre. Like personal statements, they help readers get to know applicants beyond their academic and extracurricular achievements. What makes an applicant unique? Precisely what motivates or inspires them? What is their demeanor like and how do they interact with others? All these questions are useful ways of thinking about the purpose and value of the diversity essay.

It’s important to realize that the essay does not need to focus on aspects like race, religion, or sexuality. Some applicants may choose to write about their relationship to these or other protected identity categories. But applicants shouldn’t feel obligated to ‘come out’ in a diversity essay. Conversely, they should not be anxious if they feel their background doesn’t qualify them as ‘diverse.’

Instead, the diversity essay helps demonstrate broader thinking about what makes applicants unique that admissions officials can’t glean elsewhere. Usually, it also directly or indirectly indicates how an applicant will enhance the campus community they hope to join. Diversity essays can explicitly connect past experiences with future plans. Or they can offer a more general sense of how one’s background will influence their actions in college.

Thus, the diversity essay conveys both aspects that make an applicant unique and arguments for how those aspects will contribute on campus. The somewhat daunting genre is, in fact, a great opportunity for applicants to articulate how their background, identity, or formative experiences will shape their academic, intellectual, social, and professional trajectories.

Diversity College Essay Examples of Prompts – Sharing a Story

All diversity essays ask applicants to share what makes them unique and convey how that equips them for university life. However, colleges will typically ask applicants to approach this broad topic from a variety of different angles. Since it’s likely applicants will encounter some version of the genre in either required or supplemental essay assignments, it’s a good idea to have a template diversity essay ready to adapt to each specific prompt.

One of the most standard prompts is the “share a story” prompt. For example, here’s the diversity-related Common App prompt:

“Some students have a background, identity, interest, or talent that is so meaningful they believe their application would be incomplete without it. If this sounds like you, then please share your story.”

This prompt is deliberately broad, inviting applicants to articulate their distinctive qualities in myriad ways. What is unsaid, but likely expected, is some statement about how the story evidences the ability to enhance campus diversity.

Diversity College Essay Examples of Prompts – Describing Contribution

Another common prompt explicitly asks students to reflect on diversity while centering what they will contribute in college. A good example of this prompt comes from the University of Miami’s supplemental essay:

Located within one of the most dynamic cities in the world, the University of Miami is a distinctive community with a variety of cultures, traditions, histories, languages, and backgrounds. The University of Miami is a values-based and purpose-driven postsecondary institution that embraces diversity and inclusivity in all its forms and strives to create a culture of belonging, where every person feels valued and has an opportunity to contribute.

Please describe how your unique experiences, challenges overcome, or skills acquired would contribute to our distinctive University community. (250 words)

In essays responding to these kinds of prompts, its smart to more deliberately tailor your essay to what you know about the institution and its values around diversity. You’ll need a substantial part of the essay to address not only your “story” but your anticipated institutional contribution.

Diversity College Essay Examples of Prompts – Navigating Difference

The last type of diversity essay prompt worth mentioning asks applicants to explain how they experience and navigate difference. It could be a prompt about dealing with “diverse perspectives.” Or it could ask the applicant to tell a story involving someone different than them. Regardless of the framing, these types of prompts ask you to unfold a theory of diversity stemming from social encounters. Applicants might still think of how they can use the essay to frame what makes them unique. However, here colleges are also hoping for insight into how applicants will deal with the immense diversity of college life beyond their unique experiences. In these cases, it’s especially important to use a story kernel to draw attention to fundamental beliefs and values around diversity.

How to Write a Diversity Essay – Tips for Writing

Before we get to the diversity college essay examples, some general tips for writing the diversity essay:

- Be authentic: This is not the place to embellish, exaggerate, or overstate your experiences. Writing with humility and awareness of your own limitations can only help you with the diversity essay. So don’t write about who you think the admissions committee wants to see – write about yourself.

- Find dynamic intersections: One effective brainstorming strategy is to think of two or more aspects of your background, identity, and interests you might combine. For example, in one of the examples below, the writer talks about their speech impediment alongside their passion for poetry. By thinking of aspects of your experience to combine, you’ll likely generate more original material than focusing on just one.

- Include a thesis: Diversity essays follow more general conventions of personal statement writing. That means you should tell a story about yourself, but also make it double as an argumentative piece of writing. Including a thesis in the first paragraph can clearly signal the argumentative hook of the essay for your reader.

- Include your definition of diversity: Early in the essay you should define what diversity means to you. It’s important that this definition is as original as possible, preferably connecting to the story you are narrating. To avoid cliché, you might write out a bunch of definitions of diversity. Then, review them and get rid of any that seem like something you’d see in a dictionary or an inspirational poster. Get those clichéd definitions out of your system early, so you can wow your audience with your own carefully considered definition.

How to Write a Diversity Essay – Tips for Writing (Cont.)

- Zoom out to diversity more broadly: This tip is especially important you are not writing about protected minority identities like race, religion, and sexuality. Again, it’s fine to not focus on these aspects of diversity. But you’ll want to have some space in the essay where you connect your very specific understanding of diversity to a larger system of values that can include those identities.

Revision is another, evergreen tip for writing good diversity essays. You should also remember that you are writing in a personal and narrative-based genre. So, try to be as creative as possible! If you find enjoyment in writing it, chances are better your audience will find entertainment value in reading it.

How to Write a Diversity Essay – Diversity Essay Examples

The first example addresses the “share a story” prompt. It is written in the voice of Karim Amir, the main character of Hanif Kureishi’s novel The Buddha of Suburbia .

As a child of the suburbs, I have frequently navigated the labyrinthine alleys of identity. Born to an English mother and an Indian father, I inherited a rich blend of traditions, customs, and perspectives. From an early age, I found myself straddling two worlds, trying to reconcile the conflicting expectations of my dual heritage. Yet, it was only through the lens of acting that I began to understand the true fluidity of identity.

- A fairly typical table setting first paragraph, foregrounding themes of identity and performance

- Includes a “thesis” in the final sentence suggesting the essay’s narrative and argumentative arc

Diversity, to me, is more than just a buzzword describing a melting pot of ethnic backgrounds, genders, and sexual orientations. Instead, it evokes the unfathomable heterogeneity of human experience that I aim to help capture through performance. On the stage, I have often been slotted into Asian and other ethnic minority roles. I’ve had to deal with discriminatory directors who complain I am not Indian enough. Sometimes, it has even been tempting to play into established stereotypes attached to the parts I am playing. However, acting has ultimately helped me to see that the social types we imagine when we think of the word ‘diversity’ are ultimately fantastical constructions. Prescribed identities may help us to feel a sense of belonging, but they also distort what makes us radically unique.

- Includes an original definition of diversity, which the writer compellingly contrasts with clichéd definitions

- Good narrative dynamism, stressing how the writer has experienced growth over time

Diversity Essay Examples Continued – Example One

The main challenge for an actor is to dig beneath the “type” of character to find the real human being underneath. Rising to this challenge entails discarding with lazy stereotypes and scaling what can seem to be insurmountable differences. Bringing human drama to life, making it believable, requires us to realize a more fundamental meaning of diversity. It means locating each character at their own unique intersection of identity. My story, like all the stories I aspire to tell as an actor, can inspire others to search for and celebrate their specificity.

- Focuses in on the kernel of wisdom acquired over the course of the narrative

- Indirectly suggests what the applicant can contribute to the admitted class

Acting has ultimately underlined an important takeaway of my dual heritage: all identities are, in a sense, performed. This doesn’t mean that heritage is not important, or that identities are not significant rallying points for community. Instead, it means recognizing that identity isn’t a prison, but a stage.

- Draws the reader back to where the essay began, locating them at the intersection of two aspects of writer’s background

- Sharply and deftly weaves a course between saying identities are fictions and saying that identities matter (rather than potentially alienating reader by picking one over the other)

Diversity Essay Examples Continued – Example Two

The second example addresses a prompt about what the applicant can contribute to a diverse campus. It is written from the perspective of Jason Taylor, David Mitchell’s protagonist in Black Swan Green .

Growing up with a stutter, each word was a hesitant step, every sentence a delicate balance between perseverance and frustration. I came to think of the written word as a sanctuary away from the staccato rhythm of my speech. In crafting melodically flowing poems, I discovered a language unfettered by the constraints of my impediment. However, diving deeper into poetry eventually made me realize how my stammer had a humanistic rhythm all its own.

- Situates us at the intersection of two themes – a speech impediment and poetry – and uses the thesis to gesture to their synthesis

- Nicely matches form and content. The writer uses this opportunity to demonstrate their facility with literary language.

Immersing myself in the genius of Langston Hughes, Walt Whitman, and Maya Angelou, I learned to embrace the beauty of diversity in language, rhythm, and life itself. Angelou wrote that “Everything in the universe has a rhythm, everything dances.” For me, this quote illuminates how diversity is not simply a static expression of discrete differences. Instead, diversity teaches us the beauty of a multitude of rhythms we can learn from and incorporate in a mutual dance. If “everything in the universe has a rhythm,” then it’s also possible that anything can be poetry. Even my stuttering speech can dance.

- Provides a unique definition of diversity

- Conveys growth over time

- Connects kernel of wisdom back to the essay’s narrative starting point

As I embark on this new chapter of my life, I bring with me the lessons learned from the interplay of rhythm and verse. I bring a perspective rooted in empathy, an unwavering commitment to inclusivity, and a belief in language as the ultimate tool of transformative social connection. I am prepared to enter your university community, adding a unique voice that refuses to be silent.

- Directly addresses how background and experiences will contribute to campus life

- Conveys contributions in an analytic mode (second sentence) and more literary and personal mode (third sentence)

Additional Resources

Diversity essays can seem intimidating because of the political baggage we bring to the word ‘diversity.’ But applicants should feel liberated by the opportunity to describe what makes them unique. It doesn’t matter if applicants choose to write about aspects of identity, life experiences, or personal challenges. What matters is telling a compelling story of personal growth. Also significant is relating that story to an original theory of the function and value of diversity in society. At the end of the day, committees want to know their applicants deeper and get a holistic sense of how they will improve the educational lives of those around them.

Additional Reading and Resources

- 10 Instructive Common App Essay Examples

- How to Write the Overcoming Challenges Essay + Example

- Common App Essay Prompts

- Why This College Essay – Tips for Success

- How to Write a Body Paragraph for a College Essay

- UC Essay Examples

- College Essay

Tyler Talbott

Tyler holds a Bachelor of Arts in English from the University of Missouri and two Master of Arts degrees in English, one from the University of Maryland and another from Northwestern University. Currently, he is a PhD candidate in English at Northwestern University, where he also works as a graduate writing fellow.

- 2-Year Colleges

- ADHD/LD/Autism/Executive Functioning

- Application Strategies

- Best Colleges by Major

- Best Colleges by State

- Big Picture

- Career & Personality Assessment

- College Search/Knowledge

- College Success

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Data Visualizations

- Dental School Admissions

- Extracurricular Activities

- Graduate School Admissions

- High School Success

- High Schools

- Homeschool Resources

- Law School Admissions

- Medical School Admissions

- Navigating the Admissions Process

- Online Learning

- Outdoor Adventure

- Private High School Spotlight

- Research Programs

- Summer Program Spotlight

- Summer Programs

- Teacher Tools

- Test Prep Provider Spotlight

“Innovative and invaluable…use this book as your college lifeline.”

— Lynn O'Shaughnessy

Nationally Recognized College Expert

College Planning in Your Inbox

Join our information-packed monthly newsletter.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Check your paper for plagiarism in 10 minutes, generate your apa citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- College essay

- How to Write a Diversity Essay | Tips & Examples

How to Write a Diversity Essay | Tips & Examples

Published on November 1, 2021 by Kirsten Courault . Revised on May 31, 2023.

Table of contents

What is a diversity essay, identify how you will enrich the campus community, share stories about your lived experience, explain how your background or identity has affected your life, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about college application essays.

Diversity essays ask students to highlight an important aspect of their identity, background, culture, experience, viewpoints, beliefs, skills, passions, goals, etc.

Diversity essays can come in many forms. Some scholarships are offered specifically for students who come from an underrepresented background or identity in higher education. At highly competitive schools, supplemental diversity essays require students to address how they will enhance the student body with a unique perspective, identity, or background.

In the Common Application and applications for several other colleges, some main essay prompts ask about how your background, identity, or experience has affected you.

Why schools want a diversity essay

Many universities believe a student body representing different perspectives, beliefs, identities, and backgrounds will enhance the campus learning and community experience.

Admissions officers are interested in hearing about how your unique background, identity, beliefs, culture, or characteristics will enrich the campus community.

Through the diversity essay, admissions officers want students to articulate the following:

- What makes them different from other applicants

- Stories related to their background, identity, or experience

- How their unique lived experience has affected their outlook, activities, and goals

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Think about what aspects of your identity or background make you unique, and choose one that has significantly impacted your life.

For some students, it may be easy to identify what sets them apart from their peers. But if you’re having trouble identifying what makes you different from other applicants, consider your life from an outsider’s perspective. Don’t presume your lived experiences are normal or boring just because you’re used to them.

Some examples of identities or experiences that you might write about include the following:

- Race/ethnicity

- Gender identity

- Sexual orientation

- Nationality

- Socioeconomic status

- Immigration background

- Religion/belief system

- Place of residence

- Family circumstances

- Extracurricular activities related to diversity

Include vulnerable, authentic stories about your lived experiences. Maintain focus on your experience rather than going into too much detail comparing yourself to others or describing their experiences.

Keep the focus on you

Tell a story about how your background, identity, or experience has impacted you. While you can briefly mention another person’s experience to provide context, be sure to keep the essay focused on you. Admissions officers are mostly interested in learning about your lived experience, not anyone else’s.

When I was a baby, my grandmother took me in, even though that meant postponing her retirement and continuing to work full-time at the local hairdresser. Even working every shift she could, she never missed a single school play or soccer game.

She and I had a really special bond, even creating our own special language to leave each other secret notes and messages. She always pushed me to succeed in school, and celebrated every academic achievement like it was worthy of a Nobel Prize. Every month, any leftover tip money she received at work went to a special 509 savings plan for my college education.

When I was in the 10th grade, my grandmother was diagnosed with ALS. We didn’t have health insurance, and what began with quitting soccer eventually led to dropping out of school as her condition worsened. In between her doctor’s appointments, keeping the house tidy, and keeping her comfortable, I took advantage of those few free moments to study for the GED.

In school pictures at Raleigh Elementary School, you could immediately spot me as “that Asian girl.” At lunch, I used to bring leftover fun see noodles, but after my classmates remarked how they smelled disgusting, I begged my mom to make a “regular” lunch of sliced bread, mayonnaise, and deli meat.

Although born and raised in North Carolina, I felt a cultural obligation to learn my “mother tongue” and reconnect with my “homeland.” After two years of all-day Saturday Chinese school, I finally visited Beijing for the first time, expecting I would finally belong. While my face initially assured locals of my Chinese identity, the moment I spoke, my cover was blown. My Chinese was littered with tonal errors, and I was instantly labeled as an “ABC,” American-born Chinese.

I felt culturally homeless.

Speak from your own experience

Highlight your actions, difficulties, and feelings rather than comparing yourself to others. While it may be tempting to write about how you have been more or less fortunate than those around you, keep the focus on you and your unique experiences, as shown below.

I began to despair when the FAFSA website once again filled with red error messages.

I had been at the local library for hours and hadn’t even been able to finish the form, much less the other to-do items for my application.

I am the first person in my family to even consider going to college. My parents work two jobs each, but even then, it’s sometimes very hard to make ends meet. Rather than playing soccer or competing in speech and debate, I help my family by taking care of my younger siblings after school and on the weekends.

“We only speak one language here. Speak proper English!” roared a store owner when I had attempted to buy bread and accidentally used the wrong preposition.

In middle school, I had relentlessly studied English grammar textbooks and received the highest marks.

Leaving Seoul was hard, but living in West Orange, New Jersey was much harder一especially navigating everyday communication with Americans.

After sharing relevant personal stories, make sure to provide insight into how your lived experience has influenced your perspective, activities, and goals. You should also explain how your background led you to apply to this university and why you’re a good fit.

Include your outlook, actions, and goals

Conclude your essay with an insight about how your background or identity has affected your outlook, actions, and goals. You should include specific actions and activities that you have done as a result of your insight.

One night, before the midnight premiere of Avengers: Endgame , I stopped by my best friend Maria’s house. Her mother prepared tamales, churros, and Mexican hot chocolate, packing them all neatly in an Igloo lunch box. As we sat in the line snaking around the AMC theater, I thought back to when Maria and I took salsa classes together and when we belted out Selena’s “Bidi Bidi Bom Bom” at karaoke. In that moment, as I munched on a chicken tamale, I realized how much I admired the beauty, complexity, and joy in Maria’s culture but had suppressed and devalued my own.

The following semester, I joined Model UN. Since then, I have learned how to proudly represent other countries and have gained cultural perspectives other than my own. I now understand that all cultures, including my own, are equal. I still struggle with small triggers, like when I go through airport security and feel a suspicious glance toward me, or when I feel self-conscious for bringing kabsa to school lunch. But in the future, I hope to study and work in international relations to continue learning about other cultures and impart a positive impression of Saudi culture to the world.

The smell of the early morning dew and the welcoming whinnies of my family’s horses are some of my most treasured childhood memories. To this day, our farm remains so rural that we do not have broadband access, and we’re too far away from the closest town for the postal service to reach us.

Going to school regularly was always a struggle: between the unceasing demands of the farm and our lack of connectivity, it was hard to keep up with my studies. Despite being a voracious reader, avid amateur chemist, and active participant in the classroom, emergencies and unforeseen events at the farm meant that I had a lot of unexcused absences.

Although it had challenges, my upbringing taught me resilience, the value of hard work, and the importance of family. Staying up all night to watch a foal being born, successfully saving the animals from a minor fire, and finding ways to soothe a nervous mare afraid of thunder have led to an unbreakable family bond.

Our farm is my family’s birthright and our livelihood, and I am eager to learn how to ensure the farm’s financial and technological success for future generations. In college, I am looking forward to joining a chapter of Future Farmers of America and studying agricultural business to carry my family’s legacy forward.

Tailor your answer to the university

After explaining how your identity or background will enrich the university’s existing student body, you can mention the university organizations, groups, or courses in which you’re interested.

Maybe a larger public school setting will allow you to broaden your community, or a small liberal arts college has a specialized program that will give you space to discover your voice and identity. Perhaps this particular university has an active affinity group you’d like to join.

Demonstrating how a university’s specific programs or clubs are relevant to you can show that you’ve done your research and would be a great addition to the university.

At the University of Michigan Engineering, I want to study engineering not only to emulate my mother’s achievements and strength, but also to forge my own path as an engineer with disabilities. I appreciate the University of Michigan’s long-standing dedication to supporting students with disabilities in ways ranging from accessible housing to assistive technology. At the University of Michigan Engineering, I want to receive a top-notch education and use it to inspire others to strive for their best, regardless of their circumstances.

If you want to know more about academic writing , effective communication , or parts of speech , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Academic writing

- Writing process

- Transition words

- Passive voice

- Paraphrasing

Communication

- How to end an email

- Ms, mrs, miss

- How to start an email

- I hope this email finds you well

- Hope you are doing well

Parts of speech

- Personal pronouns

- Conjunctions

In addition to your main college essay , some schools and scholarships may ask for a supplementary essay focused on an aspect of your identity or background. This is sometimes called a diversity essay .

Many universities believe a student body composed of different perspectives, beliefs, identities, and backgrounds will enhance the campus learning and community experience.

Admissions officers are interested in hearing about how your unique background, identity, beliefs, culture, or characteristics will enrich the campus community, which is why they assign a diversity essay .

To write an effective diversity essay , include vulnerable, authentic stories about your unique identity, background, or perspective. Provide insight into how your lived experience has influenced your outlook, activities, and goals. If relevant, you should also mention how your background has led you to apply for this university and why you’re a good fit.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Courault, K. (2023, May 31). How to Write a Diversity Essay | Tips & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 21, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/college-essay/diversity-essay/

Is this article helpful?

Kirsten Courault

Other students also liked, how to write about yourself in a college essay | examples, what do colleges look for in an essay | examples & tips, how to write a scholarship essay | template & example, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

The Diversity College Essay: How to Write a Stellar Essay

What’s covered:, what’s covered in a diversity essay, what is a diversity essay, examples of the diversity essay prompt, how to write the diversity college essay after the end of affirmative action, tips for writing a diversity college essay.

The Diversity Essay exists because colleges want a student body that includes different ethnicities, religions, sexual orientations, backgrounds, interests, and so on. The essay asks students to illuminate what sets them apart so that admissions committees can see what kind of diverse views and opinions they can bring to the campus.

In this post, we’ll be going over what exactly a diversity essay is, examples of real prompts and essays, and tips for writing a standout essay. You’ll be well prepared to answer this common essay prompt after reading this post!

Upon hearing the word diversity, many people assume that they have to write about gender and sexuality, class, or race. To many, this can feel overly personal or forced, or can cause students to worry that their identity isn’t unique or interesting enough. In reality, the diversity essay is much broader than many people realize.

Identity means different things to different people, and the important thing is that you demonstrate your uniqueness and what’s important to you. You might write about one of the classic, traditional identity features mentioned above, but you also could consider writing about a more unusual feature of yourself or your life—or even the intersection of two or more identities.

Consider these questions as you think about what to include in your diversity essay:

- Do you have a unique or unusual talent or skill? For example, you might be a person with perfect pitch, or one with a very accurate innate sense of direction.

- Do you have beliefs or values that are markedly different from the beliefs or values of those around you? Perhaps you hold a particular passion for scientific curiosity or truthfulness, even when it’s inconvenient.

- Do you have a hobby or interest that sets you apart from your peers? Maybe you’re an avid birder, or perhaps you love to watch old horror movies.

- Have you done or experienced something that few people have? Note that if you choose to write about a single event as a diverse identity feature, that event should have had a pretty substantial impact on you and your life. Perhaps you’re part of the 0.2% of the world that has run a marathon, or you’ve had the chance to watch wolves hunt in the wild.

- Do you have a role in life that gives you a special outlook on the world? Maybe one of your siblings has a rare disability, or you grew up in a town of less than 500 people.

Of course, if you would rather write about a more classic identity feature, you absolutely should! These questions are intended to help you brainstorm and get you thinking creatively about this prompt. You don’t need to dig deep for an extremely unusual diverse facet of yourself or your personality. If writing about something like ability, ethnicity, or gender feels more representative of your life experience, that can be an equally strong choice!

You should think expansively about your options and about what really demonstrates your individuality, but the most important thing is to be authentic and choose a topic that is truly meaningful to you.

Diversity essay prompts come up in both personal statements and supplemental essays. As with all college essays, the purpose of any prompt is to better understand who you are and what you care about. Your essays are your chance to share your voice and humanize your application. This is especially true for the diversity essay, which aims to understand your unique perspectives and experiences, as well as the ways in which you might contribute to a college community.

It’s worth noting that diversity essays are used in all kinds of selection processes beyond undergrad admissions—they’re seen in everything from graduate admissions to scholarship opportunities. You may very well need to write another diversity essay later in life, so it’s a good idea to get familiar with this essay archetype now.

If you’re not sure whether your prompt is best answered by a diversity essay, consider checking out our posts on other essay archetypes, like “Why This College?” , “Why This Major?” , and the Extracurricular Activity Essay .

The best-known diversity essay prompt is from the Common App . The first prompt states:

“Some students have a background, identity, interest, or talent that is so meaningful they believe their application would be incomplete without it. If this sounds like you, then please share your story.”

Some schools also have individual diversity essay prompts. For example, here’s one from Duke University :

“We believe a wide range of personal perspectives, beliefs, and lived experiences are essential to making Duke a vibrant and meaningful living and learning community. Feel free to share with us anything in this context that might help us better understand you and what you might bring to our community.” (250 words)

And here’s one from Rice :

“Rice is strengthened by its diverse community of learning and discovery that produces leaders and change agents across the spectrum of human endeavor. What perspectives shaped by your background, experiences, upbringing, and/or racial identity inspire you to join our community of change agents at Rice?” (500 words)

In all instances, colleges want you to demonstrate how and what you’ll contribute to their communities.

In June 2023, the Supreme Court overturned the use of affirmative action in college admissions, meaning that colleges are no longer able to directly factor race into admissions decisions. Despite this ruling, you can still discuss your racial or ethnic background in your Common App or supplemental essays.

If your race or ethnic heritage is important to you, we strongly recommend writing about it in one of your essays, as this is now one of the only ways that admissions committees are able to consider it as a factor in your admission.

Many universities still want to hear about your racial background and how it has impacted you, so you are likely to see diversity essays show up more frequently as part of supplemental essay packets. Remember, if you are seeing this kind of prompt, it’s because colleges care about your unique identity and life experience, and believe that these constitute an important part of viewing your application holistically. To learn more about how the end of affirmative action is impacting college admissions, check out our post for more details .

1. Highlight what makes you stand out.

A common misconception is that diversity only refers to aspects—such as ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, or socioeconomic status. While these are standard measures of diversity, you can be diverse in other ways. These ways includes (but aren’t limited to) your:

- Interests, hobbies, and talents

- Perspectives, values, and opinions

- Experiences

- Personality traits

Ask yourself which aspects of your identity are most central to who you are. Are these aspects properly showcased in other portions of your application? Do you have any interests, experiences, or traits you want to highlight?

For instance, maybe you’re passionate about reducing food waste. You might love hiking and the outdoors. Or, maybe you’re a talented self-taught barber who’s given hundreds of free haircuts in exchange for donations to charity.

The topic of your essay doesn’t have to be crazy or even especially unique. You just want to highlight whatever is important to you, and how this thing shapes who you are. You might still want to write about a more common aspect of identity. If so, there are strong ways to do so.

If you do choose to write about a more common trait (for example, maybe your love of running), do so in a way that tells your story. Don’t just write an ode to running and how it’s stress-relieving and pushes you past your limits. Share your journey with us—for instance, maybe you used to hate it, but you changed your mind one day and eventually trained to run a half marathon. Or, take us through your thought process during a race. The topic in itself is important, but how you write about it is even more important.

2. Share an anecdote.

One easy way to make your essay more engaging is to share a relevant and related story. The beginning of your essay is a great place for that, as it draws the reader in immediately. For instance, the following student chose to write about their Jewish identity, and opened the essay with a vivid experience of being discriminated against:

“I was thirsty. In my wallet was a lone $10 bill, ultimately useless at my school’s vending machine. Tasked with scrounging together the $1 cost of a water bottle, I fished out and arranged the spare change that normally hid at the bottom of my backpack in neat piles of nickels and dimes on my desk. I swept them into a spare Ziploc and began to leave when a classmate snatched the bag and held it above my head.

“Want your money back, Jew?” she chanted, waving the coins around. I had forgotten the Star-of-David around my neck, but quickly realized she must have seen it and connected it to the stacks of coins. I am no stranger to experiencing and confronting antisemitism, but I had never been targeted in my school before.”

An anecdote allows readers to experience what you’re describing, and to feel as if they’re there with you. This can ultimately help readers better relate to you.

Brainstorm some real-life stories relevant to the trait you want to feature. Possibilities include: a meaningful interaction, achieving a goal, a conflict, a time you felt proud of the trait (or ashamed of it), or the most memorable experience related to the trait. Your story could even be something as simple as describing your mental and emotional state while you’re doing a certain activity.

Whatever you decide on, consider sharing that moment in media res , or “in the middle of things.” Take us directly to the action in your story so we can experience it with you.

3. Show, don’t tell.

If you simply state what makes you diverse, it’s really easy for your essay to end up sounding bland. The writer of the previous essay example could’ve simply stated “I’m Jewish and I’ve had to face antisemitism.” This is a broad statement that doesn’t highlight their unique personal experiences. It doesn’t have the same emotional impact.

Instead, the writer illustrated an actual instance where they experienced antisemitism, which made the essay more vivid and easier to relate to. Even if we’re not Jewish ourselves, we can feel the anger and pain of being taunted for our background. This story is also unique to the writer’s life—while others may have experienced discrimination, no one else will have had the exact same encounter.

As you’re writing, constantly evaluate whether or not you’re sharing a unique perspective. If what you write could’ve been written by someone else with a similar background or interest, you need to get more granular. Your personal experiences are what will make your essay unique, so share those with your reader.

4. Discuss how your diversity shapes your outlook and actions.

It’s important to describe not only what your unique traits and experiences are, but also how they shape who you are. You don’t have to explicitly say “this is how X trait impacts me” (you actually shouldn’t, as that would be telling instead of showing). Instead, you can reveal the impact of your diversity through the details you share.

Maybe playing guitar taught you the importance of consistent effort. Show us this through a story of how you tackled an extremely difficult piece you weren’t sure you could handle. Show us the calluses on your fingers, the knit brows as you tinkered with the chords, the countless lessons with your teacher. Show us your elation as you finally performed the piece.

Remember that colleges learn not just about who you are, but also about what you might contribute to their community. Take your essay one step farther and show admissions officers how your diversity impacts the way you approach your life.

Where to Get Your Diversity Essay Edited

Do you want feedback on your diversity essay? After rereading your essays countless times, it can be difficult to evaluate your writing objectively. That’s why we created our free Peer Essay Review tool , where you can get a free review of your essay from another student. You can also improve your own writing skills by reviewing other students’ essays.

If you want a college admissions expert to review your essay, advisors on CollegeVine have helped students refine their writing and submit successful applications to top schools. Find the right advisor for you to improve your chances of getting into your dream school!

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Diversity Training Goals, Limitations, and Promise: A Review of the Multidisciplinary Literature

Patricia g. devine.

1 Department of Psychology, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53706, USA;

Tory L. Ash

2 Department of Psychology, Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York 13244, USA;

In this review, we utilize a narrative approach to synthesize the multidisciplinary literature on diversity training. In examining hundreds of articles on the topic, we discovered that the literature is amorphous and complex and does not allow us to reach decisive conclusions regarding best practices in diversity training. We note that scholars of diversity training, when testing the efficacy of their approaches, too often use proxy measures for success that are far removed from the types of consequential outcomes that reflect the purported goals of such trainings. We suggest that the enthusiasm for, and monetary investment in, diversity training has outpaced the available evidence that such programs are effective in achieving their goals. We recommend that researchers and practitioners work together for future investigations to propel the science of diversity training forward. We conclude with a roadmap for how to create a more rigorous and relevant science of diversity training.

INTRODUCTION

Public discourse and popular media are flooded with stories of companies implementing diversity training (DT) in response to highly publicized, and often reputation damaging, instances of bias. In a particularly salient case, Starbucks closed all 175,000 stores to host a four-hour antibias training following the controversial arrest of two Black patrons purportedly loitering while waiting for an associate to arrive ( Stewart 2018 ). In response to the outrage following the expulsion of Black passengers for allegedly laughing too loudly on the Napa Valley Train, the CEO of the company publicly promised to provide DT for all his employees ( Bhattacharjee 2016 ). In another example, Delta Air Lines offered unconscious bias training for all 23,000 flight attendants after a Black physician’s credentials were questioned when she attempted to provide emergency medical care to a fellow passenger ( Crespo 2018 ). Although the public is all too familiar with promises of reform via employee DT, much less attention is paid to the content, objectives, and effectiveness of DT. Specifically, what are the goals of DT? What should be included in DT? How would an interested consumer recognize an effective DT program? And is DT effective in reducing bias, or is it rife with empty promises?

Many scholars and laypeople alike argue that DT may be effective across a variety of contexts for reducing intergroup anxiety, preventing discrimination, and ultimately, promoting social justice. We find the hunger for knowledge regarding what practitioners can do to create more inclusive environments encouraging, as motivation to address bias is the necessary first step to achieving greater equity ( Devine 1989 ). However, the well-intentioned, yet uninformed, consumer may quickly become overwhelmed by the breadth of DT programs currently available. DT programs go by many names and range from diversity and inclusion certification programs at accredited universities to bias training via online modules and consultation services from diversity, equity, and inclusion experts. Although many programs boast endorsements from well-known companies that vouch for the efficacy of their services, their websites provide little evidence supporting the effectiveness of their programs. Despite stylish web pages featuring photos of diverse work teams, lofty promises, and persuasive customer testimonials, there is a lack of information about the particular content, techniques, and evidentiary basis underlying the application of each training. Moreover, diligent browsers are often frustrated in their efforts because many websites prohibit prospective clients from gaining more information without signing up for a listserv, consultation, or free trial.

Despite the abundance of DT programs available to purchase by the public, the practice of offering DT has gotten too far ahead of the evidence suggesting they are helpful (e.g., Green & Hagiwara 2020 , Moss-Racusin et al. 2014 , Paluck et al. 2020 ). Furthermore, some scholars explicitly question the ethics of implementing such trainings without evidence of their efficacy ( Paluck 2012 ). Others have sounded the alarm that such trainings may even be counterproductive and may be associated with a decrease in the representation of employees from historically marginalized groups ( Dobbin & Kalev 2016 , Dover et al. 2020 ).

This review summarizes the goals, content, and efficacy of DT across a variety of disciplines and settings. In light of the boom in DT and in response to calls for a more rigorous evaluation of the efficacy of DT programs ( Paluck 2012 , Paluck & Green 2009 ), this review focuses on the extent to which the science of DT has gained traction in establishing the efficacy of DT programs. And if not, where do we go from here?

Given that others have noted that “diversity training” can be considered a catch-all term (e.g., Paluck 2006 ), we cast a wide net in performing our literature search on DT. Articles included in our review evaluated DT programs targeted to address outcomes relevant to institutionalized settings. All of the studies reviewed share an emphasis on relevant samples (i.e., nurses, teachers, employees), field settings (i.e., classroom, workplace, professional conference), and training programs (rather than brief lab-based manipulations). This review is distinct in highlighting DT, specifically, and it departs from previous reviews that examine the effects of contact ( Pettigrew & Tropp 2006 ) or the broad array of prejudice reduction manipulations designed to enhance intergroup relations ( Paluck et al. 2020 ).

We used a variety of search terms and did not restrict our search to any particular field or set of journals. Search terms included: diversity training, bias/prejudice reduction interventions, antibias training, diversity education, cultural competence, bias literacy, multicultural education, ethnic studies, implicit/unconscious bias training, and racial sensitivity training. We limited our search to articles that were peer-reviewed, had adult samples, and were published during or after the year 2000. Although DT for children and adolescents is a growing topic of inquiry, this body of literature involves considerations (e.g., the developmental appropriateness of the program’s content) that fall outside the scope of this review. We restricted our database to articles published after the year 2000 for two reasons. First, that year largely marks the beginning of the big business boom of DT as a for-profit and pervasive industry ( Paluck 2006 ). Second, comprehensive reviews of the DT literature prior to 2000 already exist (e.g., Bezrukova et al. 2016 , Paluck & Green 2009 ). Our goal was to evaluate the extent to which the more recent science of DT has progressed to the point of offering clear guidelines regarding best DT practices.

Our literature search began in June of 2019 and continued until the end of 2020. In total, we collected 250 articles, which were then coded across 35 different criteria. The majority of the coding was conducted by the second author; all other coding was conducted by trained research assistants and checked by the second author. To obtain interrater reliability, two coders independently reviewed all of the articles and coded for 6 of the 35 variables, for a total of approximately 15% of the data. These 6 variables correspond to the findings reported throughout our review; interrater reliability was satisfactory (97.60% agreement).

Variables of interest were selected as being likely important for evaluating the effectiveness of DT based on prior literature reviews and meta-analyses (e.g., Bezrukova et al. 2016 , Paluck & Green 2009 , Pettigrew & Tropp 2006 ). We distinguished articles based on their setting, purpose, kind of training, and duration. To account for the scientific rigor of articles, we coded for the research design utilized, the sample selection and size, whether outcomes were self-reported or behavioral, and whether assessments were immediate or delayed. Throughout, we highlight the variables that are most germane for our review; however, readers interested in learning more about the other variables can do so on our page on the Open Science Framework website ( https://osf.io/p7sxr/ ).

Our review includes studies that were conducted in one of three settings—organizational, human services, and education—each with its own definition of DT and specific goals that the DT is meant to address. Studies conducted in organizational settings concerned diversity initiatives for employees in workplace settings. Articles within the subfield of human services discussed training for service providers (e.g., doctors, mental health professionals, and teachers) to promote equitable care. And studies positioned in educational settings evaluated the efficacy of diversity-related curricula directed at a general student audience.

Each of these subfields has an extensive DT literature, and evaluating them separately allows for an analysis of the unique strengths and shortcomings of the research in each context. In organizing our review around these subfields, we depart from prior meta-analyses that include DT but do not make such distinctions (e.g., Bezrukova et al. 2016 , Paluck & Green 2009 , Paluck et al. 2020 ). Evaluating whether DT is effective requires considering the specific goals that motivate the implementation of particular trainings. Trainings implemented to increase minority representation in a workplace, for example, have different objectives, targeted outcomes, and content compared to a training aimed at reducing patient treatment discrepancies in health care settings. As such, making direct comparisons across subfields is challenging, and inferences regarding DT made in one discipline may or may not generalize to another subfield.

Due to the disparate methodologies and wide-ranging practices encompassed by the cross-disciplinary term “diversity training,” we used a narrative approach in summarizing the literature. Within each discipline we identify the goals and approach of DT for that field, the most common methods used, the outcomes assessed, and the state of the evidence regarding the efficacy of DT. We then offer a critique of the work and some field-specific recommendations for advancing the science of DT. We conclude each section with a table summarizing the work done in that particular field and our field-specific recommendations.

DIVERSITY TRAINING FOR EMPLOYEES IN ORGANIZATIONAL SETTINGS

We begin our summary of DT with studies positioned in workplace or organizational settings. Within the United States, employee DT was born in response to the advent of affirmative action policies implemented in US workplaces following the civil rights movement of the 1960s and 1970s. During this time, DT was simply used to inform employees of antidiscrimination laws and to assimilate women and people of color into workplace culture. Today, many motivations likely underlie companies’ utilization of DT, such as the promotion of a diverse workforce, the provision of effective communication with a diverse customer base, the avoidance of workplace discrimination, and the cultivation of creative problem solving. Irrespective of motivation, as demographics continue to shift, corporations are tasked with creating increasingly multicultural, multiracial, and multigendered workplace communities. As a result, DT has become a big and booming industry. Undeniably, DT sells, and it sells well; by one estimate, companies invest $8 billion in DT each year ( Lipman 2018 ). Currently, more than half of mid-sized and large US companies offer some form of DT ( Dobbin & Kalev 2016 ). What is unknown, at this point, is whether the returns, in terms of benefits, warrant the huge investments in DT.

Goals and Approach

The goals for organizational DT include the “full integration of members of minority social categories into the social, structural, and power relationships of an organization or institution” ( Brewer et al. 1999 , p. 337). These goals encompass the recruitment and retention of employees from underrepresented backgrounds as well as increased group cohesion, creativity, and equity within a given workplace. Stated simply, organizational DT has the overarching goal of fostering an inclusive company climate ( Bezrukova et al. 2016 ). Therefore, our review of the literature evaluated questions such as, Does DT lead to increased feelings of belonging among members of historically marginalized groups? Does representation of members of historically marginalized groups improve following DT, and is this increase maintained over time? Do employees from both historically advantaged and disadvantaged groups who undergo DT report more inclusive work climates, compared to employees from organizations that do not offer DT?

Articles are included in this section if they discuss topics or use samples characteristic of organizational settings. For example, Combs & Luthans (2007) studied participants from a government agency, insurance company, and manufacturing firm. Others investigated government contract trainees ( Rehg et al. 2012 ), managers within a government agency ( Sanchez & Medkik 2004 ), and even taxicab drivers ( Reynolds 2010 ). Many studies recruited business graduate students (e.g., Bush & Ingram 2001 , Sanchez-Burks et al. 2007 ), hospitality students ( Madera et al. 2011 ), and undergraduate students either enrolled in a workplace diversity course ( Hostager & De Meuse 2008 ) or engaged in a professional setting as research ( Roberson et al. 2009 ) or teaching ( Roberson et al. 2001 ) assistants. A sizeable portion of the articles (17.02%) examined the impact of trainings targeting gender bias in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) organizations and departments (e.g., Hennes et al. 2018 , Moss-Racusin et al. 2018 ).

Many trainings pertained to the general promotion and inclusion of marginalized groups. Others, however, were specific about the group targeted, such as women (e.g., Chang et al. 2019 , Jackson et al. 2014 ), older individuals ( Reynolds 2010 ), English language learners ( Madera et al. 2011 ), and individuals with disabilities ( Phillips et al. 2016 ).

DT within organizational settings is most commonly delivered in a lecture-based format by an outside consultant ( Paluck 2006 ). Throughout the presentation, trainers often discuss the definition, benefits, and potential challenges of workplace diversity. The presentation is typically followed by group activities, such as reviewing cases of work-based prejudice ( Sanchez & Medkik 2004 ), simulating common disabilities associated with aging ( Reynolds 2010 ), and determining whether different scenarios constitute workplace discrimination ( Preusser et al. 2011 ).

As found by prior reviews, the selection of particular DT strategies appears to be most often motivated by personal preference or intuition about what trainers believe would be effective rather than by a specific theoretical approach or empirical evidence ( Cox & Devine 2019 , Pendry et al. 2007 ). Many studies from organizational settings did not include information explaining the content of the training (e.g., Holladay & Quiñones 2008 ) or justifying the use of the strategies employed (e.g., Sanchez & Medkik 2004 ).

Research Designs and Assessment of Outcomes

Of the 47 articles that discussed DT in organizational settings, 15 articles were correlational, theoretical, or qualitative; 32 studies delivered and quantitatively evaluated a training. Researchers most often utilized single-group repeated measures designs (i.e., pre–post; 43.75%), others used group designs with random assignment (i.e., experimental; 37.50%), and a few utilized group designs without random assignment (i.e., quasi-experimental; 18.75%). 1

Most studies (62.50%) assessed trainees’ cognitive and affective responses to the DT as their primary outcome of interest. 2 Specifically, many studies’ primary outcome was employees’ self-reported learning or recalled knowledge of the material presented within the training, such as knowledge of how stereotypes may influence one’s judgments in professional settings ( Roberson et al. 2009 ), what constitutes bias ( Hennes et al. 2018 ), and knowledge of cultural differences ( Rehg et al. 2012 ). Several studies also examined trainees’ perceptions of the training itself (e.g., liking, interest) through a program evaluation survey (e.g., Reynolds 2010 , Sanchez & Medkik 2004 ). Other studies examined participants’ attitudes following DT, such as supportive attitudes toward women in the workplace (e.g., Chang et al. 2019 ), attitudes toward LGBTQ+ employees (e.g., Hood et al. 2001 ), and attitudes toward non-English speakers ( Madera et al. 2011 ).