Center for Teaching

Assessing student learning.

Forms and Purposes of Student Assessment

Assessment is more than grading, assessment plans, methods of student assessment, generative and reflective assessment, teaching guides related to student assessment, references and additional resources.

Student assessment is, arguably, the centerpiece of the teaching and learning process and therefore the subject of much discussion in the scholarship of teaching and learning. Without some method of obtaining and analyzing evidence of student learning, we can never know whether our teaching is making a difference. That is, teaching requires some process through which we can come to know whether students are developing the desired knowledge and skills, and therefore whether our instruction is effective. Learning assessment is like a magnifying glass we hold up to students’ learning to discern whether the teaching and learning process is functioning well or is in need of change.

To provide an overview of learning assessment, this teaching guide has several goals, 1) to define student learning assessment and why it is important, 2) to discuss several approaches that may help to guide and refine student assessment, 3) to address various methods of student assessment, including the test and the essay, and 4) to offer several resources for further research. In addition, you may find helfpul this five-part video series on assessment that was part of the Center for Teaching’s Online Course Design Institute.

What is student assessment and why is it Important?

In their handbook for course-based review and assessment, Martha L. A. Stassen et al. define assessment as “the systematic collection and analysis of information to improve student learning” (2001, p. 5). An intentional and thorough assessment of student learning is vital because it provides useful feedback to both instructors and students about the extent to which students are successfully meeting learning objectives. In their book Understanding by Design , Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe offer a framework for classroom instruction — “Backward Design”— that emphasizes the critical role of assessment. For Wiggins and McTighe, assessment enables instructors to determine the metrics of measurement for student understanding of and proficiency in course goals. Assessment provides the evidence needed to document and validate that meaningful learning has occurred (2005, p. 18). Their approach “encourages teachers and curriculum planners to first ‘think like an assessor’ before designing specific units and lessons, and thus to consider up front how they will determine if students have attained the desired understandings” (Wiggins and McTighe, 2005, p. 18). [1]

Not only does effective assessment provide us with valuable information to support student growth, but it also enables critically reflective teaching. Stephen Brookfield, in Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher, argues that critical reflection on one’s teaching is an essential part of developing as an educator and enhancing the learning experience of students (1995). Critical reflection on one’s teaching has a multitude of benefits for instructors, including the intentional and meaningful development of one’s teaching philosophy and practices. According to Brookfield, referencing higher education faculty, “A critically reflective teacher is much better placed to communicate to colleagues and students (as well as to herself) the rationale behind her practice. She works from a position of informed commitment” (Brookfield, 1995, p. 17). One important lens through which we may reflect on our teaching is our student evaluations and student learning assessments. This reflection allows educators to determine where their teaching has been effective in meeting learning goals and where it has not, allowing for improvements. Student assessment, then, both develop the rationale for pedagogical choices, and enables teachers to measure the effectiveness of their teaching.

The scholarship of teaching and learning discusses two general forms of assessment. The first, summative assessment , is one that is implemented at the end of the course of study, for example via comprehensive final exams or papers. Its primary purpose is to produce an evaluation that “sums up” student learning. Summative assessment is comprehensive in nature and is fundamentally concerned with learning outcomes. While summative assessment is often useful for communicating final evaluations of student achievement, it does so without providing opportunities for students to reflect on their progress, alter their learning, and demonstrate growth or improvement; nor does it allow instructors to modify their teaching strategies before student learning in a course has concluded (Maki, 2002).

The second form, formative assessment , involves the evaluation of student learning at intermediate points before any summative form. Its fundamental purpose is to help students during the learning process by enabling them to reflect on their challenges and growth so they may improve. By analyzing students’ performance through formative assessment and sharing the results with them, instructors help students to “understand their strengths and weaknesses and to reflect on how they need to improve over the course of their remaining studies” (Maki, 2002, p. 11). Pat Hutchings refers to as “assessment behind outcomes”: “the promise of assessment—mandated or otherwise—is improved student learning, and improvement requires attention not only to final results but also to how results occur. Assessment behind outcomes means looking more carefully at the process and conditions that lead to the learning we care about…” (Hutchings, 1992, p. 6, original emphasis). Formative assessment includes all manner of coursework with feedback, discussions between instructors and students, and end-of-unit examinations that provide an opportunity for students to identify important areas for necessary growth and development for themselves (Brown and Knight, 1994).

It is important to recognize that both summative and formative assessment indicate the purpose of assessment, not the method . Different methods of assessment (discussed below) can either be summative or formative depending on when and how the instructor implements them. Sally Brown and Peter Knight in Assessing Learners in Higher Education caution against a conflation of the method (e.g., an essay) with the goal (formative or summative): “Often the mistake is made of assuming that it is the method which is summative or formative, and not the purpose. This, we suggest, is a serious mistake because it turns the assessor’s attention away from the crucial issue of feedback” (1994, p. 17). If an instructor believes that a particular method is formative, but he or she does not take the requisite time or effort to provide extensive feedback to students, the assessment effectively functions as a summative assessment despite the instructor’s intentions (Brown and Knight, 1994). Indeed, feedback and discussion are critical factors that distinguish between formative and summative assessment; formative assessment is only as good as the feedback that accompanies it.

It is not uncommon to conflate assessment with grading, but this would be a mistake. Student assessment is more than just grading. Assessment links student performance to specific learning objectives in order to provide useful information to students and instructors about learning and teaching, respectively. Grading, on the other hand, according to Stassen et al. (2001) merely involves affixing a number or letter to an assignment, giving students only the most minimal indication of their performance relative to a set of criteria or to their peers: “Because grades don’t tell you about student performance on individual (or specific) learning goals or outcomes, they provide little information on the overall success of your course in helping students to attain the specific and distinct learning objectives of interest” (Stassen et al., 2001, p. 6). Grades are only the broadest of indicators of achievement or status, and as such do not provide very meaningful information about students’ learning of knowledge or skills, how they have developed, and what may yet improve. Unfortunately, despite the limited information grades provide students about their learning, grades do provide students with significant indicators of their status – their academic rank, their credits towards graduation, their post-graduation opportunities, their eligibility for grants and aid, etc. – which can distract students from the primary goal of assessment: learning. Indeed, shifting the focus of assessment away from grades and towards more meaningful understandings of intellectual growth can encourage students (as well as instructors and institutions) to attend to the primary goal of education.

Barbara Walvoord (2010) argues that assessment is more likely to be successful if there is a clear plan, whether one is assessing learning in a course or in an entire curriculum (see also Gelmon, Holland, and Spring, 2018). Without some intentional and careful plan, assessment can fall prey to unclear goals, vague criteria, limited communication of criteria or feedback, invalid or unreliable assessments, unfairness in student evaluations, or insufficient or even unmeasured learning. There are several steps in this planning process.

- Defining learning goals. An assessment plan usually begins with a clearly articulated set of learning goals.

- Defining assessment methods. Once goals are clear, an instructor must decide on what evidence – assignment(s) – will best reveal whether students are meeting the goals. We discuss several common methods below, but these need not be limited by anything but the learning goals and the teaching context.

- Developing the assessment. The next step would be to formulate clear formats, prompts, and performance criteria that ensure students can prepare effectively and provide valid, reliable evidence of their learning.

- Integrating assessment with other course elements. Then the remainder of the course design process can be completed. In both integrated (Fink 2013) and backward course design models (Wiggins & McTighe 2005), the primary assessment methods, once chosen, become the basis for other smaller reading and skill-building assignments as well as daily learning experiences such as lectures, discussions, and other activities that will prepare students for their best effort in the assessments.

- Communicate about the assessment. Once the course has begun, it is possible and necessary to communicate the assignment and its performance criteria to students. This communication may take many and preferably multiple forms to ensure student clarity and preparation, including assignment overviews in the syllabus, handouts with prompts and assessment criteria, rubrics with learning goals, model assignments (e.g., papers), in-class discussions, and collaborative decision-making about prompts or criteria, among others.

- Administer the assessment. Instructors then can implement the assessment at the appropriate time, collecting evidence of student learning – e.g., receiving papers or administering tests.

- Analyze the results. Analysis of the results can take various forms – from reading essays to computer-assisted test scoring – but always involves comparing student work to the performance criteria and the relevant scholarly research from the field(s).

- Communicate the results. Instructors then compose an assessment complete with areas of strength and improvement, and communicate it to students along with grades (if the assignment is graded), hopefully within a reasonable time frame. This also is the time to determine whether the assessment was valid and reliable, and if not, how to communicate this to students and adjust feedback and grades fairly. For instance, were the test or essay questions confusing, yielding invalid and unreliable assessments of student knowledge.

- Reflect and revise. Once the assessment is complete, instructors and students can develop learning plans for the remainder of the course so as to ensure improvements, and the assignment may be changed for future courses, as necessary.

Let’s see how this might work in practice through an example. An instructor in a Political Science course on American Environmental Policy may have a learning goal (among others) of students understanding the historical precursors of various environmental policies and how these both enabled and constrained the resulting legislation and its impacts on environmental conservation and health. The instructor therefore decides that the course will be organized around a series of short papers that will combine to make a thorough policy report, one that will also be the subject of student presentations and discussions in the last third of the course. Each student will write about an American environmental policy of their choice, with a first paper addressing its historical precursors, a second focused on the process of policy formation, and a third analyzing the extent of its impacts on environmental conservation or health. This will help students to meet the content knowledge goals of the course, in addition to its goals of improving students’ research, writing, and oral presentation skills. The instructor then develops the prompts, guidelines, and performance criteria that will be used to assess student skills, in addition to other course elements to best prepare them for this work – e.g., scaffolded units with quizzes, readings, lectures, debates, and other activities. Once the course has begun, the instructor communicates with the students about the learning goals, the assignments, and the criteria used to assess them, giving them the necessary context (goals, assessment plan) in the syllabus, handouts on the policy papers, rubrics with assessment criteria, model papers (if possible), and discussions with them as they need to prepare. The instructor then collects the papers at the appropriate due dates, assesses their conceptual and writing quality against the criteria and field’s scholarship, and then provides written feedback and grades in a manner that is reasonably prompt and sufficiently thorough for students to make improvements. Then the instructor can make determinations about whether the assessment method was effective and what changes might be necessary.

Assessment can vary widely from informal checks on understanding, to quizzes, to blogs, to essays, and to elaborate performance tasks such as written or audiovisual projects (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). Below are a few common methods of assessment identified by Brown and Knight (1994) that are important to consider.

According to Euan S. Henderson, essays make two important contributions to learning and assessment: the development of skills and the cultivation of a learning style (1980). The American Association of Colleges & Universities (AAC&U) also has found that intensive writing is a “high impact” teaching practice likely to help students in their engagement, learning, and academic attainment (Kuh 2008).

Things to Keep in Mind about Essays

- Essays are a common form of writing assignment in courses and can be either a summative or formative form of assessment depending on how the instructor utilizes them.

- Essays encompass a wide array of narrative forms and lengths, from short descriptive essays to long analytical or creative ones. Shorter essays are often best suited to assess student’s understanding of threshold concepts and discrete analytical or writing skills, while longer essays afford assessments of higher order concepts and more complex learning goals, such as rigorous analysis, synthetic writing, problem solving, or creative tasks.

- A common challenge of the essay is that students can use them simply to regurgitate rather than analyze and synthesize information to make arguments. Students need performance criteria and prompts that urge them to go beyond mere memorization and comprehension, but encourage the highest levels of learning on Bloom’s Taxonomy . This may open the possibility for essay assignments that go beyond the common summary or descriptive essay on a given topic, but demand, for example, narrative or persuasive essays or more creative projects.

- Instructors commonly assume that students know how to write essays and can encounter disappointment or frustration when they discover that this is sometimes not the case. For this reason, it is important for instructors to make their expectations clear and be prepared to assist, or provide students to resources that will enhance their writing skills. Faculty may also encourage students to attend writing workshops at university writing centers, such as Vanderbilt University’s Writing Studio .

Exams and time-constrained, individual assessment

Examinations have traditionally been a gold standard of assessment, particularly in post-secondary education. Many educators prefer them because they can be highly effective, they can be standardized, they are easily integrated into disciplines with certification standards, and they are efficient to implement since they can allow for less labor-intensive feedback and grading. They can involve multiple forms of questions, be of varying lengths, and can be used to assess multiple levels of student learning. Like essays they can be summative or formative forms of assessment.

Things to Keep in Mind about Exams

- Exams typically focus on the assessment of students’ knowledge of facts, figures, and other discrete information crucial to a course. While they can involve questioning that demands students to engage in higher order demonstrations of comprehension, problem solving, analysis, synthesis, critique, and even creativity, such exams often require more time to prepare and validate.

- Exam questions can be multiple choice, true/false, or other discrete answer formats, or they can be essay or problem-solving. For more on how to write good multiple choice questions, see this guide .

- Exams can make significant demands on students’ factual knowledge and therefore can have the side-effect of encouraging cramming and surface learning. Further, when exams are offered infrequently, or when they have high stakes by virtue of their heavy weighting in course grade schemes or in student goals, they may accompany violations of academic integrity.

- In the process of designing an exam, instructors should consider the following questions. What are the learning objectives that the exam seeks to evaluate? Have students been adequately prepared to meet exam expectations? What are the skills and abilities that students need to do well on the exam? How will this exam be utilized to enhance the student learning process?

Self-Assessment

The goal of implementing self-assessment in a course is to enable students to develop their own judgment and the capacities for critical meta-cognition – to learn how to learn. In self-assessment students are expected to assess both the processes and products of their learning. While the assessment of the product is often the task of the instructor, implementing student self-assessment in the classroom ensures students evaluate their performance and the process of learning that led to it. Self-assessment thus provides a sense of student ownership of their learning and can lead to greater investment and engagement. It also enables students to develop transferable skills in other areas of learning that involve group projects and teamwork, critical thinking and problem-solving, as well as leadership roles in the teaching and learning process with their peers.

Things to Keep in Mind about Self-Assessment

- Self-assessment is not self-grading. According to Brown and Knight, “Self-assessment involves the use of evaluative processes in which judgement is involved, where self-grading is the marking of one’s own work against a set of criteria and potential outcomes provided by a third person, usually the [instructor]” (1994, p. 52). Self-assessment can involve self-grading, but instructors of record retain the final authority to determine and assign grades.

- To accurately and thoroughly self-assess, students require clear learning goals for the assignment in question, as well as rubrics that clarify different performance criteria and levels of achievement for each. These rubrics may be instructor-designed, or they may be fashioned through a collaborative dialogue with students. Rubrics need not include any grade assignation, but merely descriptive academic standards for different criteria.

- Students may not have the expertise to assess themselves thoroughly, so it is helpful to build students’ capacities for self-evaluation, and it is important that they always be supplemented with faculty assessments.

- Students may initially resist instructor attempts to involve themselves in the assessment process. This is usually due to insecurities or lack of confidence in their ability to objectively evaluate their own work, or possibly because of habituation to more passive roles in the learning process. Brown and Knight note, however, that when students are asked to evaluate their work, frequently student-determined outcomes are very similar to those of instructors, particularly when the criteria and expectations have been made explicit in advance (1994).

- Methods of self-assessment vary widely and can be as unique as the instructor or the course. Common forms of self-assessment involve written or oral reflection on a student’s own work, including portfolio, logs, instructor-student interviews, learner diaries and dialog journals, post-test reflections, and the like.

Peer Assessment

Peer assessment is a type of collaborative learning technique where students evaluate the work of their peers and, in return, have their own work evaluated as well. This dimension of assessment is significantly grounded in theoretical approaches to active learning and adult learning . Like self-assessment, peer assessment gives learners ownership of learning and focuses on the process of learning as students are able to “share with one another the experiences that they have undertaken” (Brown and Knight, 1994, p. 52). However, it also provides students with other models of performance (e.g., different styles or narrative forms of writing), as well as the opportunity to teach, which can enable greater preparation, reflection, and meta-cognitive organization.

Things to Keep in Mind about Peer Assessment

- Similar to self-assessment, students benefit from clear and specific learning goals and rubrics. Again, these may be instructor-defined or determined through collaborative dialogue.

- Also similar to self-assessment, it is important to not conflate peer assessment and peer grading, since grading authority is retained by the instructor of record.

- While student peer assessments are most often fair and accurate, they sometimes can be subject to bias. In competitive educational contexts, for example when students are graded normatively (“on a curve”), students can be biased or potentially game their peer assessments, giving their fellow students unmerited low evaluations. Conversely, in more cooperative teaching environments or in cases when they are friends with their peers, students may provide overly favorable evaluations. Also, other biases associated with identity (e.g., race, gender, or class) and personality differences can shape student assessments in unfair ways. Therefore, it is important for instructors to encourage fairness, to establish processes based on clear evidence and identifiable criteria, and to provide instructor assessments as accompaniments or correctives to peer evaluations.

- Students may not have the disciplinary expertise or assessment experience of the instructor, and therefore can issue unsophisticated judgments of their peers. Therefore, to avoid unfairness, inaccuracy, and limited comments, formative peer assessments may need to be supplemented with instructor feedback.

As Brown and Knight assert, utilizing multiple methods of assessment, including more than one assessor when possible, improves the reliability of the assessment data. It also ensures that students with diverse aptitudes and abilities can be assessed accurately and have equal opportunities to excel. However, a primary challenge to the multiple methods approach is how to weigh the scores produced by multiple methods of assessment. When particular methods produce higher range of marks than others, instructors can potentially misinterpret and mis-evaluate student learning. Ultimately, they caution that, when multiple methods produce different messages about the same student, instructors should be mindful that the methods are likely assessing different forms of achievement (Brown and Knight, 1994).

These are only a few of the many forms of assessment that one might use to evaluate and enhance student learning (see also ideas present in Brown and Knight, 1994). To this list of assessment forms and methods we may add many more that encourage students to produce anything from research papers to films, theatrical productions to travel logs, op-eds to photo essays, manifestos to short stories. The limits of what may be assigned as a form of assessment is as varied as the subjects and skills we seek to empower in our students. Vanderbilt’s Center for Teaching has an ever-expanding array of guides on creative models of assessment that are present below, so please visit them to learn more about other assessment innovations and subjects.

Whatever plan and method you use, assessment often begins with an intentional clarification of the values that drive it. While many in higher education may argue that values do not have a role in assessment, we contend that values (for example, rigor) always motivate and shape even the most objective of learning assessments. Therefore, as in other aspects of assessment planning, it is helpful to be intentional and critically reflective about what values animate your teaching and the learning assessments it requires. There are many values that may direct learning assessment, but common ones include rigor, generativity, practicability, co-creativity, and full participation (Bandy et al., 2018). What do these characteristics mean in practice?

Rigor. In the context of learning assessment, rigor means aligning our methods with the goals we have for students, principles of validity and reliability, ethics of fairness and doing no harm, critical examinations of the meaning we make from the results, and good faith efforts to improve teaching and learning. In short, rigor suggests understanding learning assessment as we would any other form of intentional, thoroughgoing, critical, and ethical inquiry.

Generativity. Learning assessments may be most effective when they create conditions for the emergence of new knowledge and practice, including student learning and skill development, as well as instructor pedagogy and teaching methods. Generativity opens up rather than closes down possibilities for discovery, reflection, growth, and transformation.

Practicability. Practicability recommends that learning assessment be grounded in the realities of the world as it is, fitting within the boundaries of both instructor’s and students’ time and labor. While this may, at times, advise a method of learning assessment that seems to conflict with the other values, we believe that assessment fails to be rigorous, generative, participatory, or co-creative if it is not feasible and manageable for instructors and students.

Full Participation. Assessments should be equally accessible to, and encouraging of, learning for all students, empowering all to thrive regardless of identity or background. This requires multiple and varied methods of assessment that are inclusive of diverse identities – racial, ethnic, national, linguistic, gendered, sexual, class, etcetera – and their varied perspectives, skills, and cultures of learning.

Co-creation. As alluded to above regarding self- and peer-assessment, co-creative approaches empower students to become subjects of, not just objects of, learning assessment. That is, learning assessments may be more effective and generative when assessment is done with, not just for or to, students. This is consistent with feminist, social, and community engagement pedagogies, in which values of co-creation encourage us to critically interrogate and break down hierarchies between knowledge producers (traditionally, instructors) and consumers (traditionally, students) (e.g., Saltmarsh, Hartley, & Clayton, 2009, p. 10; Weimer, 2013). In co-creative approaches, students’ involvement enhances the meaningfulness, engagement, motivation, and meta-cognitive reflection of assessments, yielding greater learning (Bass & Elmendorf, 2019). The principle of students being co-creators of their own education is what motivates the course design and professional development work Vanderbilt University’s Center for Teaching has organized around the Students as Producers theme.

Below is a list of other CFT teaching guides that supplement this one and may be of assistance as you consider all of the factors that shape your assessment plan.

- Active Learning

- An Introduction to Lecturing

- Beyond the Essay: Making Student Thinking Visible in the Humanities

- Bloom’s Taxonomy

- Classroom Assessment Techniques (CATs)

- Classroom Response Systems

- How People Learn

- Service-Learning and Community Engagement

- Syllabus Construction

- Teaching with Blogs

- Test-Enhanced Learning

- Assessing Student Learning (a five-part video series for the CFT’s Online Course Design Institute)

Angelo, Thomas A., and K. Patricia Cross. Classroom Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for College Teachers . 2 nd edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1993. Print.

Bandy, Joe, Mary Price, Patti Clayton, Julia Metzker, Georgia Nigro, Sarah Stanlick, Stephani Etheridge Woodson, Anna Bartel, & Sylvia Gale. Democratically engaged assessment: Reimagining the purposes and practices of assessment in community engagement . Davis, CA: Imagining America, 2018. Web.

Bass, Randy and Heidi Elmendorf. 2019. “ Designing for Difficulty: Social Pedagogies as a Framework for Course Design .” Social Pedagogies: Teagle Foundation White Paper. Georgetown University, 2019. Web.

Brookfield, Stephen D. Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1995. Print

Brown, Sally, and Peter Knight. Assessing Learners in Higher Education . 1 edition. London ;Philadelphia: Routledge, 1998. Print.

Cameron, Jeanne et al. “Assessment as Critical Praxis: A Community College Experience.” Teaching Sociology 30.4 (2002): 414–429. JSTOR . Web.

Fink, L. Dee. Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses. Second Edition. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2013. Print.

Gibbs, Graham and Claire Simpson. “Conditions under which Assessment Supports Student Learning. Learning and Teaching in Higher Education 1 (2004): 3-31. Print.

Henderson, Euan S. “The Essay in Continuous Assessment.” Studies in Higher Education 5.2 (1980): 197–203. Taylor and Francis+NEJM . Web.

Gelmon, Sherril B., Barbara Holland, and Amy Spring. Assessing Service-Learning and Civic Engagement: Principles and Techniques. Second Edition . Stylus, 2018. Print.

Kuh, George. High-Impact Educational Practices: What They Are, Who Has Access to Them, and Why They Matter , American Association of Colleges & Universities, 2008. Web.

Maki, Peggy L. “Developing an Assessment Plan to Learn about Student Learning.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 28.1 (2002): 8–13. ScienceDirect . Web. The Journal of Academic Librarianship. Print.

Sharkey, Stephen, and William S. Johnson. Assessing Undergraduate Learning in Sociology . ASA Teaching Resource Center, 1992. Print.

Walvoord, Barbara. Assessment Clear and Simple: A Practical Guide for Institutions, Departments, and General Education. Second Edition . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2010. Print.

Weimer, Maryellen. Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice. Second Edition . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2013. Print.

Wiggins, Grant, and Jay McTighe. Understanding By Design . 2nd Expanded edition. Alexandria,

VA: Assn. for Supervision & Curriculum Development, 2005. Print.

[1] For more on Wiggins and McTighe’s “Backward Design” model, see our teaching guide here .

Photo credit

Teaching Guides

- Online Course Development Resources

- Principles & Frameworks

- Pedagogies & Strategies

- Reflecting & Assessing

- Challenges & Opportunities

- Populations & Contexts

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

Advertisement

Does continuous assessment in higher education support student learning?

- Published: 24 January 2012

- Volume 64 , pages 489–502, ( 2012 )

Cite this article

- Rosario Hernández 1

8823 Accesses

106 Citations

5 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

A distinction is often made in the literature about “assessment of learning” and “assessment for learning” attributing a formative function to the latter while the former takes a summative function. While there may be disagreements among researchers and educators about such categorical distinctions there is consensus that both types of assessment are often used concurrently in higher education institutions. A question that often arises when formative and summative assessment practices are used in continuous assessment is the extent to which student learning can be facilitated through feedback. The views and perceptions of students and academics from a discipline in the Humanities across seven higher education institutions were sought to examine the above question. A postal survey was completed by academics, along with a survey administered to a sample of undergraduate students and a semi-structured interview was conducted with key academics in each of the seven institutions. This comparative study highlights issues that concern both groups about the extent to which continuous assessment practices facilitate student learning and the challenges faced. The findings illustrate the need to consider more effective and efficient ways in which feedback can be better used to facilitate student learning.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The Contributions of Continuous Assessment to the Improvement of Students’ Learning of School Science

Student Involvement in Assessment of their Learning

Assessment in the service of learning: challenges and opportunities or plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

Hugh Burkhardt & Alan Schoenfeld

Biggs, J. B. (2003). Teaching for quality learning at university (2nd ed.). Buckingham: SRHE and Open University Press.

Google Scholar

Bishop, G. (2004). First steps towards electronic marking of language assignments. Language Learning Journal, 29 , 42–46.

Article Google Scholar

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education, 5 (1), 7–74.

Bloxham, S., & Boyd, P. (2007). Developing effective assessment in higher education: A practical guide . Berkshire: Open University Press.

Brown, S. (1999). Institutional strategies for assessment. In S. Brown & A. Glasner (Eds.), Assessment matters in higher education: Choosing and using diverse approaches (pp. 3–13). Buckingham: SRHE and Open University Press.

Brown, E., & Glover, C. (2006). Evaluating written feedback. In C. Bryan & K. Clegg (Eds.), Innovative assessment in higher education (pp. 81–91). London: Routledge.

Brown, S., & Knight, P. (1994). Assessing learners in higher education . London: Kogan Page.

Brown, G., Bull, J., & Pendlebury, M. (1997). Assessing student learning in higher education . London: Routledge.

Bryan, C., & Clegg, K. (2006). Introduction. In C. Bryan & K. Clegg (Eds.), Innovative assessment in higher education (pp. 1–7). London: Routledge.

Carless, D. (2006). Differing perceptions in the feedback process. Studies in Higher Education, 31 (2), 219–233.

Carless, D. (2007). Learning-oriented assessment: Conceptual bases and practical implications. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 44 (1), 57–66.

Crisp, B. (2007). Is it worth the effort? How feedback influences students’ subsequent submission of assessable work. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 32 (5), 571–581.

Gibbs, G. (1999). Using assessment strategically to change the way students learn. In S. Brown & A. Glasner (Eds.), Assessment matters in higher education: Choosing and using diverse approaches (pp. 41–53). London: SRHE and Open University Press.

Gibbs, G. (2006a). How assessment frames student learning. In C. Bryan & K. Clegg (Eds.), Innovative assessment in higher education (pp. 23–36). London: Routledge.

Gibbs, G. (2006b). Why assessment is changing. In C. Bryan & K. Clegg (Eds.), Innovative assessment in higher education (pp. 11–22). London: Routledge.

Gibbs, G., & Simpson, C. (2004). Conditions under which assessment supports students’ learning. Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, 1 , 3–31.

Gibbs, G., Simpson, C., & Macdonald, R. (2003). Improving student learning through changing assessment - a conceptual and practical framework . Paper presented at the 2003 European Association for Research into Learning and Instruction Conference, Padova, Italy. Retrieved 3 July 2004, from http://www.open.ac.uk/science/fdtl/pub.htm .

Hernández, R. (2008). The challenges of engaging students with feedback . Paper presented at the 4th Biennial EARLI/Northumbria Assessment Conference, 27–29 August, Postdam/Berlin.

Heywood, J. (2000). Assessment in higher education . London: Jessica Kingsley.

Higgins, R., Hartley, P., & Skelton, A. (2001). Getting the message across: The problem of communicating assessment feedback. Teaching in Higher Education, 6 (2), 269–274.

Isaksson, S. (2007). Assess as you go: The effect of continuous assessment on student learning during a short course in archaeology. Asessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 33 (1), 1–7.

Joughin, G. (2004, November). Learning oriented assessment: A conceptual framework . Paper presented at the effective learning and teaching conference, Brisbane. Retrieved June 14, 2007, from http://www.ied.edu.hk/loap/ETL_Joughin_LOAP.pdf .

Joughin (2009). Assessment, learning and judgment in higher education: A critical review. In G. Joughin (Ed.), Assessment, learning and judgment in higher education (pp. 13–27). doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-8905-3 : Springer Science and Business Media.

Knight, P. T., & Yorke, M. (2003). Assessment, learning and employability . Maidenhead: SRHE and Open University Press.

Maclellan, E. (2001). Assessment for learning: The differing perceptions of tutors and students. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 26 (4), 307–318.

McDowell, L., & Sambell, K. (1999). The experience of innovative assessment: Student perspectives. In S. Brown & A. Glasner (Eds.), Assessment matters in higher education: Choosing and using diverse approaches (pp. 71–82). Buckingham: SRHE and Open University Press.

McDowell, L., Sambell, K., Bazin, V., Penlington, R., Wakelin, D., Wickes, H., et al. (2005). Assessment for learning: Current practice exemplars from the centre for excellence in teaching and learning, guides for staff . Newcastle: University of Northumbria at Newcastle.

Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education. (2007). Integrative assessment: Balancing assessment of learning and assessment for learning. Retrieved June 12, 2007, from http://www.enhancementthemes.ac.uk/ .

Ramsden, P. (2003). Learning to teach in higher education (2nd ed.). London: Routledge/Falmer.

Robson, C. (2002). Real world research (2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell.

Rowntree, D. (1987). Assessing students: How shall we know them? London and New York: Harper & Row.

Rust, C. (2002). The impact of assessment on student learning. Active Learning in Higher Education, 3 (2), 145–158.

Sadler, D. R. (1989). Formative assessment in the design of instructional systems. Instructional Science, 18 , 119–144.

Schmidt, M., & Ó Dochartaigh, P. (2001). Assessment in modern languages: Getting it right . Coleraine: University of Ulster Publications.

Scouller K. (1996). The influence of assessment method on students’ learning approaches, perceptions and preferences: The assignment essay versus the short answer examination. HERDSA 1996 conference proceedings . Retrieved 27 Nov 2003, from http://www.herdsa.org.au/confs/1996/scouller.html .

Scouller, K. (1998). The influence of assessment method on student’ learning approaches: Multiple choice question examination versus assignment essay. Higher Education, 35 , 453–472.

Taras, M. (2005). Assessment—summative and formative—some theoretical reflections. British Journal of Educational Studies, 53 (4), 466–478.

Taras, M. (2008). Summative and formative assessment: Perceptions and realities. Active Learning in Higher Education, 9 (2), 172–192.

Trotter, E. (2006). Student perceptions of continuous summative assessment. Asessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 31 (5), 505–521.

Yorke, M. (2003). Formative assessment in higher education: Moves towards theory and the enhancement of pedagogic practice. Higher Education, 45 , 477–501.

Yorke, M. (2007). Assessment , especially in the first year of higher education : Old principles in new wrapping? Paper presented at the REAP international online conference on assessment design for learner responsibility. Retrieved 10 June 2007, from http://ewds.strath.ac.uk/REAP07 .

Download references

Acknowledgments

This study was part of a wider PhD research project on practices and perceptions of assessment in undergraduate Hispanic Studies Programmes at Universities in the Republic of Ireland. I would like to thank Dr. Patricia Kieran for her assistance in preparing the graphs for this publication.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Languages and Literatures, University College Dublin, Newman Building, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland

Rosario Hernández

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rosario Hernández .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Hernández, R. Does continuous assessment in higher education support student learning?. High Educ 64 , 489–502 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-012-9506-7

Download citation

Published : 24 January 2012

Issue Date : October 2012

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-012-9506-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Continuous assessment

- Student learning

- Higher education

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Professional development

- Knowing the subject

- Teaching Knowledge database A-C

Continuous assessment

Continuous assessment means assessing aspects of learners' language throughout their course and then producing a final evaluation result from these assessments.

It can be compared with a final or summative assessment, which only assesses the learner at the end of the course. Continuous assessment often provides a more accurate and complete picture of the learner's level and has a positive impact on learning.

Example The learners are giving mini-presentations on their favourite films as a follow-up activity after reading about the history of cinema. The teacher evaluates their presentations and uses the results as part of their final result.

In the classroom Continuous assessment can be made more relevant and motivating by asking the learners to decide which assignments and tasks will be assessed during the course.

Further links:

https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/assessment

https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/testing-assessment

https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/ongoing-assessment-fun-not-fear

I like this learning

I like this learning procedure!

- Log in or register to post comments

Research and insight

Browse fascinating case studies, research papers, publications and books by researchers and ELT experts from around the world.

See our publications, research and insight

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

CONTINUOUS ASSESSMENT IN EDUCATION: PROBLEMS AND PROSPECTS

2021, Online Journal by League of Educational Researchers International (LERI)

The National Policy on Education (FRN, 1981) introduced some innovations into the Nigerian educational system. The system, often referred to as the 6-3-3-4 system, came in with a new assessment procedure. It introduced the concept of Continuous Assessment (C.A) in place of the one inherited at independence often referred to as the one-shot kind of evaluation (Denga, 1987 and Okon 1984, cited in Kukwi, 2003). Thus a critical look at the National Policy on Education (FRN, 1995) reveals importance attached to Continuous Assessment. The single shot system was found to have a series of shortcomings. It was observed that, the “one-shot” type was summative in nature, anxiety provoking and teachers taught exclusively for examination (WAEC, 1989, cited in Kukwi, 2003). Various kinds of examination malpractices were also related to the system, since the single examination was the sole determinant of the candidates‟ future. Consequently, the temptation to ensure success by any means was very high (Federal Ministry of Education 1995, cited in Kukwi, 2003). Furthermore it lacked formative evaluation and place high premium on certificate (Ikejani, 1999) and was responsible for the disproportionate school dropouts.

Related Papers

Alexander Decker

BEST Journals

The focus of this paper is Continuous Assessment in Nigeria; issues and challenges. The paper examines the meaning of continuous assessment, characteristics of continuous assessment, rational for adopting continuous assessment, implementing continuous assessment within school, phases of data collection in continuous assessment. It goes further to highlight keeping and reporting continuous assessment records, characteristics of a good continuous assessment records, implementation problems of continuous assessment, problems of assessing the non-cognitive Domain and the advantages of continuous assessment. Some of the challenges of continuous assessment include; as teachers assessment their own students, one cannot guarantee that the standards are the same across schools. That is so because the assessment instruments may focus on different topics and grading, there is shortage of assessment instruments and many teachers lack the skill of instrument construction, because the scores obtained in different assessments have to be combined, a problem arises as these scores may not be based on the same scale and it is poorly implemented because of the absence of proper monitoring programme among others. In conclusion, continuous assessment if well implemented will go a long was to minimizing the tendency and temptation to ensure success by all means orchestrated by the single final examination.

HENRY OWUSU

The study assessed the usage of effective Continuous Assessment Techniques in reducing examination malpractices in Nigerian schools rather than the use of one shot examination in Ilesa East Local Government Area of Osun State, Nigeria. The population for the study were teachers (in training and service.) The purposive sampling techniques were used to select the schools and the stratified random samplings were used to select the samples. The samples included 200 participants, consisting 100 males and 100 females Year II students-teacher in training from Osun state College of Education Ilesa and teachers in service in secondary schools. The study used descriptive survey design. The instruments used were Students' Questionnaire on Effective Continuous Assessment Techniques (SQECAT) and the Secondary School Teachers Questionnaire on Effective Continuous Assessment Techniques (SSTQECAT). Two research hypotheses were formulated to guide the study. The hypotheses were tested using simple percentage and independent T-test statistical techniques. The results of the analysis showed that there is a significant difference in students' and teachers' adoption of Continuous Assessment (CA) as an alternative effective technique in reducing examination malpractices in Nigerian schools. On the basis of the results it was recommended among others that it would be better to adopt the effective and proper implementation of the techniques of Continuous Assessment in Schools as an alternative to one shot examination in Nigerian Schools which would help in reducing examination malpractices, make students work harder and make teachers become more innovative

samson O oyedeji

The International Journal of Humanities & Social Studies

Stanley U. Nnorom PhD

Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Science

Bamidele Faleye

Nigerian Journal Of Curriculum Studies

Tochukwu Chinyelugo

Dr Heman Usman Bassi

Dr Heman U Bassi

Irene Vilakazi

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Columbia University in the City of New York

- Office of Teaching, Learning, and Innovation

- University Policies

- Columbia Online

- Academic Calendar

- Resources and Technology

- Instructional Technologies

- Teaching in All Modalities

Designing Assignments for Learning

The rapid shift to remote teaching and learning meant that many instructors reimagined their assessment practices. Whether adapting existing assignments or creatively designing new opportunities for their students to learn, instructors focused on helping students make meaning and demonstrate their learning outside of the traditional, face-to-face classroom setting. This resource distills the elements of assignment design that are important to carry forward as we continue to seek better ways of assessing learning and build on our innovative assignment designs.

On this page:

Rethinking traditional tests, quizzes, and exams.

- Examples from the Columbia University Classroom

- Tips for Designing Assignments for Learning

Reflect On Your Assignment Design

Connect with the ctl.

- Resources and References

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2021). Designing Assignments for Learning. Columbia University. Retrieved [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/teaching-with-technology/teaching-online/designing-assignments/

Traditional assessments tend to reveal whether students can recognize, recall, or replicate what was learned out of context, and tend to focus on students providing correct responses (Wiggins, 1990). In contrast, authentic assignments, which are course assessments, engage students in higher order thinking, as they grapple with real or simulated challenges that help them prepare for their professional lives, and draw on the course knowledge learned and the skills acquired to create justifiable answers, performances or products (Wiggins, 1990). An authentic assessment provides opportunities for students to practice, consult resources, learn from feedback, and refine their performances and products accordingly (Wiggins 1990, 1998, 2014).

Authentic assignments ask students to “do” the subject with an audience in mind and apply their learning in a new situation. Examples of authentic assignments include asking students to:

- Write for a real audience (e.g., a memo, a policy brief, letter to the editor, a grant proposal, reports, building a website) and/or publication;

- Solve problem sets that have real world application;

- Design projects that address a real world problem;

- Engage in a community-partnered research project;

- Create an exhibit, performance, or conference presentation ;

- Compile and reflect on their work through a portfolio/e-portfolio.

Noteworthy elements of authentic designs are that instructors scaffold the assignment, and play an active role in preparing students for the tasks assigned, while students are intentionally asked to reflect on the process and product of their work thus building their metacognitive skills (Herrington and Oliver, 2000; Ashford-Rowe, Herrington and Brown, 2013; Frey, Schmitt, and Allen, 2012).

It’s worth noting here that authentic assessments can initially be time consuming to design, implement, and grade. They are critiqued for being challenging to use across course contexts and for grading reliability issues (Maclellan, 2004). Despite these challenges, authentic assessments are recognized as beneficial to student learning (Svinicki, 2004) as they are learner-centered (Weimer, 2013), promote academic integrity (McLaughlin, L. and Ricevuto, 2021; Sotiriadou et al., 2019; Schroeder, 2021) and motivate students to learn (Ambrose et al., 2010). The Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning is always available to consult with faculty who are considering authentic assessment designs and to discuss challenges and affordances.

Examples from the Columbia University Classroom

Columbia instructors have experimented with alternative ways of assessing student learning from oral exams to technology-enhanced assignments. Below are a few examples of authentic assignments in various teaching contexts across Columbia University.

- E-portfolios: Statia Cook shares her experiences with an ePorfolio assignment in her co-taught Frontiers of Science course (a submission to the Voices of Hybrid and Online Teaching and Learning initiative); CUIMC use of ePortfolios ;

- Case studies: Columbia instructors have engaged their students in authentic ways through case studies drawing on the Case Consortium at Columbia University. Read and watch a faculty spotlight to learn how Professor Mary Ann Price uses the case method to place pre-med students in real-life scenarios;

- Simulations: students at CUIMC engage in simulations to develop their professional skills in The Mary & Michael Jaharis Simulation Center in the Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons and the Helene Fuld Health Trust Simulation Center in the Columbia School of Nursing;

- Experiential learning: instructors have drawn on New York City as a learning laboratory such as Barnard’s NYC as Lab webpage which highlights courses that engage students in NYC;

- Design projects that address real world problems: Yevgeniy Yesilevskiy on the Engineering design projects completed using lab kits during remote learning. Watch Dr. Yesilevskiy talk about his teaching and read the Columbia News article .

- Writing assignments: Lia Marshall and her teaching associate Aparna Balasundaram reflect on their “non-disposable or renewable assignments” to prepare social work students for their professional lives as they write for a real audience; and Hannah Weaver spoke about a sandbox assignment used in her Core Literature Humanities course at the 2021 Celebration of Teaching and Learning Symposium . Watch Dr. Weaver share her experiences.

Tips for Designing Assignments for Learning

While designing an effective authentic assignment may seem like a daunting task, the following tips can be used as a starting point. See the Resources section for frameworks and tools that may be useful in this effort.

Align the assignment with your course learning objectives

Identify the kind of thinking that is important in your course, the knowledge students will apply, and the skills they will practice using through the assignment. What kind of thinking will students be asked to do for the assignment? What will students learn by completing this assignment? How will the assignment help students achieve the desired course learning outcomes? For more information on course learning objectives, see the CTL’s Course Design Essentials self-paced course and watch the video on Articulating Learning Objectives .

Identify an authentic meaning-making task

For meaning-making to occur, students need to understand the relevance of the assignment to the course and beyond (Ambrose et al., 2010). To Bean (2011) a “meaning-making” or “meaning-constructing” task has two dimensions: 1) it presents students with an authentic disciplinary problem or asks students to formulate their own problems, both of which engage them in active critical thinking, and 2) the problem is placed in “a context that gives students a role or purpose, a targeted audience, and a genre.” (Bean, 2011: 97-98).

An authentic task gives students a realistic challenge to grapple with, a role to take on that allows them to “rehearse for the complex ambiguities” of life, provides resources and supports to draw on, and requires students to justify their work and the process they used to inform their solution (Wiggins, 1990). Note that if students find an assignment interesting or relevant, they will see value in completing it.

Consider the kind of activities in the real world that use the knowledge and skills that are the focus of your course. How is this knowledge and these skills applied to answer real-world questions to solve real-world problems? (Herrington et al., 2010: 22). What do professionals or academics in your discipline do on a regular basis? What does it mean to think like a biologist, statistician, historian, social scientist? How might your assignment ask students to draw on current events, issues, or problems that relate to the course and are of interest to them? How might your assignment tap into student motivation and engage them in the kinds of thinking they can apply to better understand the world around them? (Ambrose et al., 2010).

Determine the evaluation criteria and create a rubric

To ensure equitable and consistent grading of assignments across students, make transparent the criteria you will use to evaluate student work. The criteria should focus on the knowledge and skills that are central to the assignment. Build on the criteria identified, create a rubric that makes explicit the expectations of deliverables and share this rubric with your students so they can use it as they work on the assignment. For more information on rubrics, see the CTL’s resource Incorporating Rubrics into Your Grading and Feedback Practices , and explore the Association of American Colleges & Universities VALUE Rubrics (Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education).

Build in metacognition

Ask students to reflect on what and how they learned from the assignment. Help students uncover personal relevance of the assignment, find intrinsic value in their work, and deepen their motivation by asking them to reflect on their process and their assignment deliverable. Sample prompts might include: what did you learn from this assignment? How might you draw on the knowledge and skills you used on this assignment in the future? See Ambrose et al., 2010 for more strategies that support motivation and the CTL’s resource on Metacognition ).

Provide students with opportunities to practice

Design your assignment to be a learning experience and prepare students for success on the assignment. If students can reasonably expect to be successful on an assignment when they put in the required effort ,with the support and guidance of the instructor, they are more likely to engage in the behaviors necessary for learning (Ambrose et al., 2010). Ensure student success by actively teaching the knowledge and skills of the course (e.g., how to problem solve, how to write for a particular audience), modeling the desired thinking, and creating learning activities that build up to a graded assignment. Provide opportunities for students to practice using the knowledge and skills they will need for the assignment, whether through low-stakes in-class activities or homework activities that include opportunities to receive and incorporate formative feedback. For more information on providing feedback, see the CTL resource Feedback for Learning .

Communicate about the assignment

Share the purpose, task, audience, expectations, and criteria for the assignment. Students may have expectations about assessments and how they will be graded that is informed by their prior experiences completing high-stakes assessments, so be transparent. Tell your students why you are asking them to do this assignment, what skills they will be using, how it aligns with the course learning outcomes, and why it is relevant to their learning and their professional lives (i.e., how practitioners / professionals use the knowledge and skills in your course in real world contexts and for what purposes). Finally, verify that students understand what they need to do to complete the assignment. This can be done by asking students to respond to poll questions about different parts of the assignment, a “scavenger hunt” of the assignment instructions–giving students questions to answer about the assignment and having them work in small groups to answer the questions, or by having students share back what they think is expected of them.

Plan to iterate and to keep the focus on learning

Draw on multiple sources of data to help make decisions about what changes are needed to the assignment, the assignment instructions, and/or rubric to ensure that it contributes to student learning. Explore assignment performance data. As Deandra Little reminds us: “a really good assignment, which is a really good assessment, also teaches you something or tells the instructor something. As much as it tells you what students are learning, it’s also telling you what they aren’t learning.” ( Teaching in Higher Ed podcast episode 337 ). Assignment bottlenecks–where students get stuck or struggle–can be good indicators that students need further support or opportunities to practice prior to completing an assignment. This awareness can inform teaching decisions.

Triangulate the performance data by collecting student feedback, and noting your own reflections about what worked well and what did not. Revise the assignment instructions, rubric, and teaching practices accordingly. Consider how you might better align your assignment with your course objectives and/or provide more opportunities for students to practice using the knowledge and skills that they will rely on for the assignment. Additionally, keep in mind societal, disciplinary, and technological changes as you tweak your assignments for future use.

Now is a great time to reflect on your practices and experiences with assignment design and think critically about your approach. Take a closer look at an existing assignment. Questions to consider include: What is this assignment meant to do? What purpose does it serve? Why do you ask students to do this assignment? How are they prepared to complete the assignment? Does the assignment assess the kind of learning that you really want? What would help students learn from this assignment?

Using the tips in the previous section: How can the assignment be tweaked to be more authentic and meaningful to students?

As you plan forward for post-pandemic teaching and reflect on your practices and reimagine your course design, you may find the following CTL resources helpful: Reflecting On Your Experiences with Remote Teaching , Transition to In-Person Teaching , and Course Design Support .

The Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) is here to help!

For assistance with assignment design, rubric design, or any other teaching and learning need, please request a consultation by emailing [email protected] .

Transparency in Learning and Teaching (TILT) framework for assignments. The TILT Examples and Resources page ( https://tilthighered.com/tiltexamplesandresources ) includes example assignments from across disciplines, as well as a transparent assignment template and a checklist for designing transparent assignments . Each emphasizes the importance of articulating to students the purpose of the assignment or activity, the what and how of the task, and specifying the criteria that will be used to assess students.

Association of American Colleges & Universities (AAC&U) offers VALUE ADD (Assignment Design and Diagnostic) tools ( https://www.aacu.org/value-add-tools ) to help with the creation of clear and effective assignments that align with the desired learning outcomes and associated VALUE rubrics (Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education). VALUE ADD encourages instructors to explicitly state assignment information such as the purpose of the assignment, what skills students will be using, how it aligns with course learning outcomes, the assignment type, the audience and context for the assignment, clear evaluation criteria, desired formatting, and expectations for completion whether individual or in a group.

Villarroel et al. (2017) propose a blueprint for building authentic assessments which includes four steps: 1) consider the workplace context, 2) design the authentic assessment; 3) learn and apply standards for judgement; and 4) give feedback.

References

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., & DiPietro, M. (2010). Chapter 3: What Factors Motivate Students to Learn? In How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching . Jossey-Bass.

Ashford-Rowe, K., Herrington, J., and Brown, C. (2013). Establishing the critical elements that determine authentic assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. 39(2), 205-222, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2013.819566 .

Bean, J.C. (2011). Engaging Ideas: The Professor’s Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom . Second Edition. Jossey-Bass.

Frey, B. B, Schmitt, V. L., and Allen, J. P. (2012). Defining Authentic Classroom Assessment. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation. 17(2). DOI: https://doi.org/10.7275/sxbs-0829

Herrington, J., Reeves, T. C., and Oliver, R. (2010). A Guide to Authentic e-Learning . Routledge.

Herrington, J. and Oliver, R. (2000). An instructional design framework for authentic learning environments. Educational Technology Research and Development, 48(3), 23-48.

Litchfield, B. C. and Dempsey, J. V. (2015). Authentic Assessment of Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. 142 (Summer 2015), 65-80.

Maclellan, E. (2004). How convincing is alternative assessment for use in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. 29(3), June 2004. DOI: 10.1080/0260293042000188267

McLaughlin, L. and Ricevuto, J. (2021). Assessments in a Virtual Environment: You Won’t Need that Lockdown Browser! Faculty Focus. June 2, 2021.

Mueller, J. (2005). The Authentic Assessment Toolbox: Enhancing Student Learning through Online Faculty Development . MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching. 1(1). July 2005. Mueller’s Authentic Assessment Toolbox is available online.

Schroeder, R. (2021). Vaccinate Against Cheating With Authentic Assessment . Inside Higher Ed. (February 26, 2021).

Sotiriadou, P., Logan, D., Daly, A., and Guest, R. (2019). The role of authentic assessment to preserve academic integrity and promote skills development and employability. Studies in Higher Education. 45(111), 2132-2148. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1582015

Stachowiak, B. (Host). (November 25, 2020). Authentic Assignments with Deandra Little. (Episode 337). In Teaching in Higher Ed . https://teachinginhighered.com/podcast/authentic-assignments/

Svinicki, M. D. (2004). Authentic Assessment: Testing in Reality. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. 100 (Winter 2004): 23-29.

Villarroel, V., Bloxham, S, Bruna, D., Bruna, C., and Herrera-Seda, C. (2017). Authentic assessment: creating a blueprint for course design. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. 43(5), 840-854. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2017.1412396

Weimer, M. (2013). Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice . Second Edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Wiggins, G. (2014). Authenticity in assessment, (re-)defined and explained. Retrieved from https://grantwiggins.wordpress.com/2014/01/26/authenticity-in-assessment-re-defined-and-explained/

Wiggins, G. (1998). Teaching to the (Authentic) Test. Educational Leadership . April 1989. 41-47.

Wiggins, Grant (1990). The Case for Authentic Assessment . Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation , 2(2).

Wondering how AI tools might play a role in your course assignments?

See the CTL’s resource “Considerations for AI Tools in the Classroom.”

This website uses cookies to identify users, improve the user experience and requires cookies to work. By continuing to use this website, you consent to Columbia University's use of cookies and similar technologies, in accordance with the Columbia University Website Cookie Notice .

College of Education

February 2022: spotlight on assessment and continuous improvement.

Spotlight is published twice each semester by the Office of Assessment and Continuous Improvement in the College of Education to highlight promising practices in assessment and continuous improvement.

Education to highlight promising practices in assessment and continuous improvement. This edition of the Spotlight examines one-sentence summaries as an assessment for creative thinking and synthesis, the College of Education’s Improvement Planning Model, and using ICON’s SpeedGrader with rubrics for fast and efficient feedback.

College of Education Mission, Vision & Values

Mission statement.

To deliver a personal, affordable, and top-ranked education for students who want to collaborate with renowned faculty to solve problems and effect change in the field of education in our community, our country, and around the world.

Vision Statement

A world-class college of education: leading research, engaging our communities, and preparing education and mental health professionals for innovation and impact.

- D iversity and Inclusion

- U nrelenting Commitment to Communities

- C ontinuous Improvement and Innovation

- A nti-racist Action

- T eamwork and Collaboration

- E xcellence and Integrity

In This Issue

- Classroom Assessment Assessing Creative Thinking and Synthesis with One-Sentence Summaries

- College Data The College of Education’s Improvement Planning Model

- Promising Practice Use SpeedGrader with Rubrics in ICON for Fast and Efficient Grading and Feedback

Future Opportunities

Contributors.

Prepared by Jeremy Penn with support from Michelle Yu and the Continuous Improvement Committee

To share a promising practice in a future edition of the Spotlight you are using in your classroom, in your program, or in your department, please contact [email protected] .

Classroom Assessment Tidbit

Assessing Creative Thinking and Synthesis with One-Sentence Summaries

Thomas Angelo and Patricia Cross (1993) offer one-sentence summaries as a deceptively simple assessment strategy for synthesis and creative thinking. One-sentence summaries can be written in 5-10 minutes, do not require much time to assess, and can be a powerful learning experience for students during class. One-sentence summaries are useful for helping students bring together a large amount of complex material on a specific topic. It can also be useful for helping students prepare to communicate large amounts of complex material to others.

To implement one-sentence summaries, start by selecting a topic and then working through the assessment on your own. Then, double the amount of time it took you to complete the assessment and determine how you want summaries submitted to you (e.g., on paper, via email, or posted somewhere in ICON).

At the heart of this assessment is what Angelo and Cross call “WDWWWWHW,” or “who does what to whom, when, where, how, and why?” Start by briefly answering each of these statements separately. For instance, if the topic was about how laws are made in the United States, the responses might look like this:

- Who: Senators, Representatives, and the President

- Does what: Submit, debate, and vote on legislation

- When: Legislative terms

- How: Bills are proposed through committees which are voted in the House and Senate chambers, then the President decides whether to sign or veto legislation

- Why: To serve their constituents and achieve political agendas and goals

- Next, take these responses and convert them into a single, grammatically correct sentence.

- Sample sentence: In the United States, to serve their constituents and achieve political goals, a new law must be proposed by a Member of Congress to various congressional committees who select laws to advance for voting by the Senate and the House, and, upon passing in both chambers, must then be signed by the President.

To assess, look for each element of the assignment (WDWWWWHW) and then assess the grammar and flow of the final sentence. Consider sharing examples with students in class to identify common gaps or strong summaries that might work with various audiences.

Be sure to test the one-sentence summary yourself prior to assigning it to your students as not all topics are amenable to this format.

College Data Tidbit

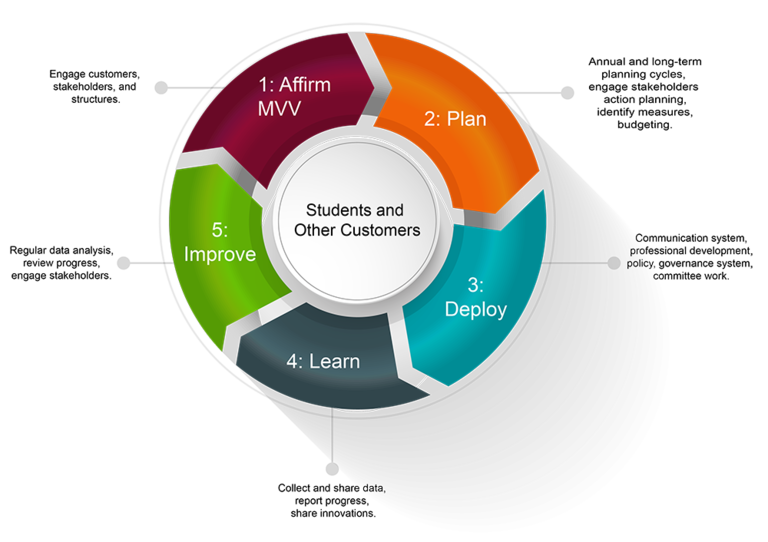

The College of Education’s Improvement Planning Model

Instead of summarizing a recent assessment result, this month we will provide a description of the College’s Improvement Planning model. This model, shown in Figure 1, is based on the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) continuous improvement model popularized by Dr. W. Edwards Deming and Walter Shewhart. This model can be used to support improvement planning and continuous improvement efforts at any level – from one-on-one mentoring of a student, to a course, to a degree program, or even to the College of Education itself. The five steps in the College’s Improvement Planning model are described in more detail below.

- Affirm Mission, Vision, and Values . This first step is assumed to be in place for use of PDSA. It is explicitly included in the College’s model as a reminder of the importance of regularly returning to the mission (what you do and how you do it), the vision (what you seek to achieve or what difference you will make in the world), and your values (core principles that guide and direct you). As the driver of the other four steps in the model, it is essential that participants have a shared, thorough understanding of the mission, vision, and values. It is also important to engage with stakeholders, students, customers, and administrative structures (such as College or University mission statements and vision statements) as part of the mission, vision, and values step.

- Plan . Planning should include long-term (such as 5-10 years) and short-term (1-year or less) planning cycles. Long-term plans should be used for big organizational goals, such as capital projects or significant growth in employment or enrollment. Short-term plans should identify key strategies that can be achieved in a shorter time frame and will support the unit’s long-term plans. Planning processes should engage stakeholders, customers, and students, and should connect with budgeting processes and measures of success.

- Deploy . The most challenging component of any improvement or planning cycle is putting the plans into action. Important levers for implementing plans is clear communication, professional development, changes in policy, leadership, and committees or other similar structures to support plan implementation.

- Learn . In some continuous improvement models this step is called “check.” The College of Education uses “learn” to reinforce the goal of this step is to learn about what is working and what is not working rather than simply checking a series of boxes or meeting an arbitrary benchmark. Learning requires looking at data on progress, reflecting on progress, and drawing conclusions about which actions are showing promise and which actions need to be modified.

- Improve . The final step is to take improvement actions in response to what was learned in step #4. This might include sharing data with students and other stakeholders, meeting with staff and faculty to examine what is working and not working, and then engaging in improvement actions. Examples of improvement actions might include professional development, making resources available for innovations, or changing short-term (or even long-term!) plans.

Using a systematic Improvement Planning model is critical for successful continuous improvement efforts. The College of Education’s Office of Assessment and Continuous Improvement is a resource for continuous improvement efforts in the College and will support your efforts through providing consulting, presentations, data analysis support, templates, and other support as needed. The University of Iowa is currently exploring strategic planning software tools which may also support these efforts at some point later this year.

Promising Practice

Use SpeedGrader with Rubrics in ICON for Fast and Efficient Grading and Feedback