- Open access

- Published: 04 July 2015

Universal health coverage from multiple perspectives: a synthesis of conceptual literature and global debates

- Gilbert Abotisem Abiiro 1 , 2 &

- Manuela De Allegri 1

BMC International Health and Human Rights volume 15 , Article number: 17 ( 2015 ) Cite this article

21k Accesses

76 Citations

18 Altmetric

Metrics details

There is an emerging global consensus on the importance of universal health coverage (UHC), but no unanimity on the conceptual definition and scope of UHC, whether UHC is achievable or not, how to move towards it, common indicators for measuring its progress, and its long-term sustainability. This has resulted in various interpretations of the concept, emanating from different disciplinary perspectives. This paper discusses the various dimensions of UHC emerging from these interpretations and argues for the need to pay attention to the complex interactions across the various components of a health system in the pursuit of UHC as a legal human rights issue.

The literature presents UHC as a multi-dimensional concept, operationalized in terms of universal population coverage, universal financial protection, and universal access to quality health care, anchored on the basis of health care as an international legal obligation grounded in international human rights laws. As a legal concept, UHC implies the existence of a legal framework that mandates national governments to provide health care to all residents while compelling the international community to support poor nations in implementing this right. As a humanitarian social concept, UHC aims at achieving universal population coverage by enrolling all residents into health-related social security systems and securing equitable entitlements to the benefits from the health system for all. As a health economics concept, UHC guarantees financial protection by providing a shield against the catastrophic and impoverishing consequences of out-of-pocket expenditure, through the implementation of pooled prepaid financing systems. As a public health concept, UHC has attracted several controversies regarding which services should be covered: comprehensive services vs. minimum basic package, and priority disease-specific interventions vs. primary health care.

As a multi-dimensional concept, grounded in international human rights laws, the move towards UHC in LMICs requires all states to effectively recognize the right to health in their national constitutions. It also requires a human rights-focused integrated approach to health service delivery that recognizes the health system as a complex phenomenon with interlinked functional units whose effective interaction are essential to reach the equilibrium called UHC.

Peer Review reports

Universal health coverage (UHC) has been acknowledged as a priority goal of every health system [ 1 – 5 ]. The importance of this goal is reflected in the consistent calls by the World Health Organization (WHO) for its member states to implement pooled prepaid health care financing systems that promote access to quality health care and provide households with the needed protection from the catastrophic consequences of out-of-pocket (OOP) health-related payments [ 2 , 6 – 8 ]. This call has also been endorsed by the United Nations [ 5 ].

In the existing literature, different conceptual terminology, such as universal health care [ 9 ], universal health care coverage [ 10 , 11 ], universal health system, universal health coverage, or simply universal coverage, have been used to refer to basically the same concept [ 9 , 12 – 14 ]. Stuckler et al. [ 15 ] noted that “universal health care” is often used to describe health care reforms in high income countries while “universal health coverage” is associated with health system reforms within low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Given that the poor, marginalized and most vulnerable populations mostly reside in LMICs, this paper places relatively high emphasis on such settings. Hence, we adopt the term universal health coverage (UHC) [ 2 ] throughout the paper.

It is argued that health system reforms aimed at UHC can be traced back to the emergence of organized health care in the 19th century, in response to labor agitations calling for the implementation of social security systems [ 16 – 18 ]. This phenomenon first started in Germany under the leadership of Otto von Bismarck, and later spread throughout other parts of Europe such as Britain, France and Sweden [ 16 – 18 ]. Later in 1948, the concept of UHC was implicitly enshrined in the WHO constitution which recognized that “the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, and political belief, economic or social condition ” [ 19 ]. This fundamental human right was reaffirmed in the “ Health for all ” declaration of the Alma Ata conference on primary health care in 1978 [ 20 ].

In 2005, the concept of UHC was once again acknowledged and for the first time explicitly endorsed by the World Health Assembly (WHA) as the goal of sustainable health care financing [ 6 ]. The World Health Assembly resolution (WHA58.33) explicitly called for the implementation of health care financing systems centered on prepaid and pooling mechanisms aimed at achieving UHC [ 6 ]. Based on this Resolution, WHO defined UHC as “access to key promotive, preventive, curative and rehabilitative health interventions for all at an affordable cost, thereby achieving equity in access” [ 6 ] . The 2008 World Health Report re-emphasized prepayment and pooling systems as essential instruments for UHC by categorically stating that UHC entails “ pooling pre-paid contributions collected on the basis of ability to pay, and using these funds to ensure that services are available, accessible and produce quality care for those who need them, without exposing them to the risk of catastrophic expenditures” [ 7 ] . In 2010, the World Health Report, further stressed the role of health system financing for UHC by arguing that “ countries must raise sufficient funds, reduce the reliance on direct payments to finance services, and improve efficiency and equity” [ 2 ] . The concept of UHC as reflected in these WHO reports seems to be focused more on improving the health care financing function of a health system. The 2013 World Health Report built on prior work resulting in a call for research evidence to facilitate the transition of countries towards UHC [ 8 ]. The United Nations, the World Bank, the Gates Foundation, Oxfam, United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the International Labour Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), Rockefeller Foundation, Results for Development Institute, the Joint Learning Network, among other international and regional development organizations have also in various ways recently endorsed and promoted the move towards UHC [ 5 , 21 – 25 ]. Considering the key role of the WHO and these other global actors in shaping the health policy debate at the global level, this recent history demonstrates a consistent and increasing international interest in the concept and debates surrounding UHC [ 2 , 26 ].

To date, the literature continues to present a clear consensus on the importance of UHC [ 23 , 27 – 29 ]. UHC was described by the Director General of WHO as “ the single most powerful concept that public health has to offer” [ 30 ]. Its potential to improve the health of the population, especially for the poor, has been demonstrated [ 31 , 32 ]. It is viewed as the phenomenon that will result in the third global transition and hence greatly influence the (re-) organization and financing of global health systems [ 29 ]. As an essential catalyst for poverty reduction and economic growth [ 14 , 33 , 34 ], UHC is regarded as a prerequisite for sustainable development [ 35 ]. It has therefore been advocated for as an important health goal in the post-2015 global development agenda [ 35 – 40 ]. The Lancet Commission on Investing in Health reports that this goal can be progressively attained by 2035 [ 34 ].

Despite the global consensus on its importance, consensus on the conceptual definition, meaning, and scope of UHC are still missing [ 12 , 26 , 41 ]. Likewise, no consensus exists on whether UHC is achievable or not; on how to move towards it [ 3 , 22 , 42 , 43 ]; on common indicators for measuring progress towards it [ 13 , 24 , 28 , 29 , 44 ]; and on its long-term sustainability [ 27 ]. The absence of a clear consensus on the conceptual definition of UHC has resulted in various interpretations of the concept, emanating from different disciplinary perspectives. These different interpretations reveal distinct, but interlinked dimensions of UHC [ 2 ]. This paper seeks to explore these various interpretations and representations of the concept of UHC from a multidimensional perspective and to discuss the various dimensions of UHC emerging from these interpretations. The arguments presented in this paper are based on a synthesis of the literature emerging from recent global debates on UHC. We adapted the WHO framework [ 2 ] to guide the presentation of our synthesis of the conceptual debates currently being advanced in the literature. Inspired by the WHO framework, our conceptual reasoning is that advancing UHC requires a healthy interaction across the three coverage dimensions: population coverage, financial protection and access to health services, held together by the view of health as a legal human right.

Discussions

Universal health coverage as a legal right to health.

A group of scholars, building their opinions from a legal and human rights perspective, enshrined in various international covenants and treaties [ 45 – 49 ], argue that the concept of UHC implies the existence of a legal framework to ensure that every resident gets access to affordable health care [ 15 , 50 , 51 ]. This portrays UHC as a reformulation of the “ health for all” goal of the Alma Ata Declaration [ 15 , 22 , 52 – 54 ]. The view of UHC as a legal obligation imposed on all states that ratified the convention on the right to health [ 45 ], implies that UHC calls for all States to create legal entitlements to health care for all their residents [ 50 , 55 , 56 ], thereby placing the responsibility for the delivery of UHC on national governments [ 5 , 17 , 57 ]. To guarantee a comprehensive right to health, the legal obligation of the state needs to reach beyond mere health service provision to include deliberate efforts to advance improvements in structures which are recognized to act as important social determinants of health such as, education, housing, sanitation and portable water as well as equitable gender and power relations [ 58 – 60 ]. The goal of UHC and the responsibility of moving towards it, therefore, need to be mandated by national laws [ 4 , 61 , 62 ]. Backman et al. [ 63 ] report that only 56 states have constitutional provisions that legally recognize the right to health and argue that even within these states, much work is still needed to ensure that this right is guaranteed in actual practice for all. Kingston et al. [ 55 ] also argue that even the state-centered view of the right to health is based on a false assumption that all people have legal nationalities. They insist that this false assumption is the cause for the medical exclusion of some migrants, especially illegal immigrants, from accessing institutionalized health care within their countries of residence. This situation is even more serious in LIMCs, where states find it difficult to raise sufficient revenues to finance health care for their legal citizenry. The vague definition of the right to health for non-nationals premised on the individual state’s economic ability and willingness to guarantee it [ 46 ], is therefore a potential recipe for social exclusion on the basis of nationality. Current debates on UHC therefore need to seriously reflect on ways by which the rights of stateless individuals to health care can also be guaranteed within the framework of UHC.

Acknowledging financial constraints to enforcing the right to health within poor-resource settings, some scholars explicitly call for international assistance for health as a way of strengthening the right to health component of UHC [ 62 , 64 ]. This, they argue, can be implemented through the establishment of a global fund to finance UHC [ 65 ] thereby presenting health as a global public good [ 66 ]. The notion of creating a common fund for UHC also recognizes the transnational nature of emerging global health problems and the inherent global interdependency needed to deal with such problems [ 67 ]. The possibility of funding global efforts towards UHC from this global fund is being explored. Initial results reveal conflicting expectations and interests between the potential donors/financiers and beneficiary countries [ 65 ]. The rights-based arguments for UHC therefore suggest a shift on the ethical spectrum of international assistance for health, from the concept of international health, where international assistance for health is viewed as a form of charity, towards that of global health [ 62 , 67 – 69 ] which is driven by the cosmopolitan ethical preposition that states should assist each other on the basis of humanitarian responsibility [ 68 , 69 ] and solidarity [ 67 ]. This cosmopolitan ethical view has the potential of facilitating efforts at raising more international assistance to facilitate UHC within its broader dimensions currently being advanced by WHO and other global experts.

Population coverage as a dimension of universal health coverage

Another group of scholars [ 22 , 61 ], also supportive of the rights-based perspective, argue that UHC implies “ equal or same entitlements” to the benefits of a health system. This reflects the notion of universal enrollment into health-related social security or risk protection systems [ 17 , 70 ] or population coverage under public health financing systems [ 2 ]. This notion therefore puts people (population) at the center of UHC [ 71 ]. Universal population coverage is to be understood in relation to the tenets of the right to health [ 45 ] as the absence of systemic exclusion of certain population groups (especially the poor and vulnerable) from the coverage of public prepaid funds and the ability of all residents to enjoy the same entitlements to the benefits of such public funding, irrespective of their nationality, race, sexual orientation, gender, political affiliations, socio-economic status or geographic locations [ 2 , 12 , 22 , 53 , 55 , 61 , 72 – 74 ].

To distinguish between aggregate and equity-based measures of population coverage, both WHO & the World Bank [ 24 ] have defined population coverage along two dimensions. Thus; achieving a 100 % coverage of the total population as an aggregate measure, or ensuring a relatively good proportion of coverage of the poorest 40 % compared to the rest of the population as an equity-based measure [ 24 ]. The overall notion of equity, defined as progressive income-rated contributions to health financing and need-based entitlements to health services, is embedded in almost all conceptual definitions of universal population coverage [ 2 , 4 , 75 – 77 ]. Implicit in the notion of equity is the concept of income and risk cross-subsidization [ 78 ], whereby the rich cross-subsidize the poor, whilst the healthy cross-subsidize the sick [ 61 ]. Notwithstanding this, other scholars have warned that universal population coverage, although desirable, must be carefully pursued to avoid creating a situation of which official entitlements will be offered to all people yet the existing health system may not have sufficient capacity to deliver quality health care for all the population [ 79 , 80 ]. This is referred to as adverse incorporation or inclusion [ 79 ].

Financial protection as a dimension of universal health coverage

From the perspective of health economics, UHC is viewed as a means of protection against the economic consequences of ill health [ 81 , 82 ]. A guaranteed financial protection requires the implementation of a health care financing mechanism that does not require direct (substantial) out-of-pocket (OOP) payments, official or informal, such as user fees, copayments and deductibles, for health care at the point of use [ 23 , 74 , 81 , 83 ]. This is the reason why the international community has endorsed financing health care from pooled prepaid mechanisms such as tax (general or dedicated) revenue, and contributions from social health insurance (usually for formal sector employees), private health insurance, and micro health insurance as essential pre-requisites for moving towards universal financial protection [ 6 ]. The existing literature does not reveal a consensus on the best prepayment mechanism or the right mix of prepayment systems that will guarantee adequate financial protection [ 22 , 84 ]. A report by Oxfam [ 22 ] suggests that within the context of LMICs, different development partners each promote their ideologically favored prepayment mechanisms as a strategy towards achieving UHC. Both the WHO and the academic community, however, recommend that such ideological prescriptions should be abandoned in favor of mixed pooling systems that can coordinate funds from different prepaid sources, in a manner that reflects context-specific UHC needs [ 2 , 28 ]. This recommendation is also rooted in the recognition that no country, not even high income ones, has achieved complete coverage, relying solely on one single financing strategy [ 4 ]. Within a mixed pooling system, there is the need to ensure proper monitory of both private and public inputs that go into the financing system.

The WHO recommends two measures for assessing progress towards financial protection: the incidence of catastrophic health care expenditure and the incidence of impoverishment resulting from OOP payments for health care [ 25 ]. The proportion of total health care expenditure incurred through OOP payments is normally used as an indicator of financial protection at the national level [ 2 ]. WHO recommends a maximum OOP expenditure threshold of 15–20 % of total health care expenditure as a requirement for financial protection [ 2 ]. At the household level, a quantitative measure of financial protection is the proportion of households incurring OOP healthcare expenditure exceeding 40 % of their household’s non-subsistence (i.e., non-food) expenditure [ 85 ] or 10 % of total household expenditure [ 86 ]. It must be noted that direct medical cost of seeking health care is not the only barrier to financial protection. A good estimate of catastrophic health care expenditure must therefore reflect all relevant costs including non-medical costs such as the cost of travelling to a health facility and loss of earnings while being treated among others. These quantitative measures, estimated on the basis of actual health care cost incurred, however, only reflect the true situation of financial risk protection if all those who need care can actually utilize health services [ 87 ]. It is argued that, such utilization-focused quantitative cost estimates are often not able to capture the quantum of needed healthcare that is forgone due to fear of impoverishment associated with utilization [ 87 ]. Effective universal financial protection can, therefore, be attained not only if the population does not incur (substantial) OOP payments and critical income losses due to payment for health care, but if there are no fears of and delays in seeking healthcare due to financial reasons, no borrowing and sale of valuable assets to pay for healthcare, and no detentions in hospitals for non-payment of bills [ 2 , 61 , 80 , 86 , 88 – 90 ].

Access to services as a dimension of universal health coverage

From the perspective of public health, it is argued that a UHC package should include a comprehensive spectrum of health services in line with the WHO’s conceptualization of UHC as “ access to key promotive, preventive, curative and rehabilitative health interventions … ” [ 2 , 6 ]. From a feasibility view point, other scholars, however, argue that the focus should be on the provision of a minimum basic package to cover priority health needs for which there are effective low-cost interventions [ 91 ] . Some of these scholars insist that this package should include priority services in line with the health-related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) [ 14 , 24 ], thereby suggesting a continuous focus on vertical disease-specific interventions. While some of these scholars argue that the expansion and effective implementation of disease-specific interventions, especially those focused on prevention, can improve health and reduce health system costs, opponents insist that all disease-specific interventions create fragmentation and undermine broader efforts aimed at system-wide strengthening [ 92 , 93 ]. The opposing scholars call for a focus on primary health care [ 7 , 15 , 94 ], to the extent that Yates [ 74 ] calls for a clear timetable, proposing 2015 as deadline, for the achievement of universal access to primary health care.

A number of authors further distinguish between official health service coverage, defined in terms of entitlement to services, and actual effective coverage, defined in terms of real access and utilization of health services according to need [ 13 , 44 , 51 ]. It follows that attempts to measure UHC should focus on indicators that measure actual effective service coverage in relation to people’s ability to obtain real access to services, without facing barriers on both the demand and the supply side [ 13 , 51 , 70 ]. Real access, is further defined as access in relation to the availability of health services, personnel and facilities; geographical accessibility of health services; acceptability defined in relation to appropriate client-provider interactions, timeliness, appropriateness and quality of services; and affordability in terms of medical and transport costs of services relative to clients’ ability-to-pay [ 73 , 80 , 95 – 106 ]. A guaranteed sufficient capacity of the local health system, in terms of adequate health infrastructure, qualified human resources, equipment and tools, to deliver quality health care is therefore an essential component of the access dimension of UHC [ 2 , 11 , 107 ]. It is interesting to note that “ Availability, Acceptability, Affordability and Quality (AAAQ)” of health services as essential sub-components of real access are directly rooted in the human rights conceptual framework and captured in broader discussions on the right to health [ 45 , 63 ].

Considering its interactive facets, it can be concluded that UHC emerges from the literature as a multi-dimensional concept, operationalized in terms of population coverage of health-related social security systems, financial protection, and access to quality health care according to need [ 17 ], and pursued within the framework of health care as an international legal obligation grounded in international human rights laws [ 45 , 46 , 48 , 49 ]. As an essential pre-condition for moving towards UHC in LMICs, there is therefore the need for all states to abide by the international human rights obligation imposed on them and thereby legally recognize the right to health in their national constitutions. It is only on this basis that the needed national and political commitment can be enhanced for a successful move towards universal population coverage of health-related social security systems, financial protection and access to services, which are essential components of a guaranteed comprehensive right to health and hence UHC. UHC can thus be understood as a broad legal, rights-based, social humanitarian, health economics and public health concept [ 15 , 17 , 27 , 42 ]. As such, it transcends a mere legal extension of the coverage of prepaid financing systems such as health insurance or tax-based systems to all residents, to ensuring that other financial and health system bottlenecks are removed to enhance effective financial protection and equitable access to services for all. As an overall health system strengthening tool, UHC can only be achieved through a human rights-focused integrated approach that recognizes the health system as a complex phenomenon with interlinked functional units whose effective interaractions are essential to reach the equilibrium called UHC. It follows that in LMICs, interventions aimed at strengthening health systems need to attract as much attention and funding as currently being deployed towards disease-specific interventions within the framework of the MDGs. Such an action has the capability of improving local service delivery capacity and hence of building resilient and responsive health systems to facilitate the move towards UHC. The move towards UHC should therefore be conceptualized as a continuous process of identifying gaps in the various interactive UHC dimensions, and designing context-specific strategies to address these gaps in accordance with the international legal obligations imposed on states by international agreements on the right to health. As a global issue, international assistance based on the principle of global solidarity is indispensable in the move towards UHC in LMICs.

Abbreviations

Availability, Acceptability, Affordability, Quality

Low - and Middle-Income Countries

Millennium Development Goals

Out-of-pocket

Universal Health coverage

United Nations Children’s Fund

United States Agency for International Development

World Health Assembly

World Health Organization

Garrett L, Chowdhury AMR, Pablos-Méndez A. All for universal health coverage. Lancet. 2009;374:1294–9.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

WHO. The World Health Report 2010 - Health Systems Financing: the path to universal coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

Google Scholar

Mills A, Ally M, Goudge J, Gyapong J, Mtei G. Progress towards universal coverage: the health systems of Ghana, South Africa and Tanzania. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27 suppl 1:i4–12.

Kutzin J. Health financing for universal coverage and health system performance: concepts and implications for policy. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:602–11.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

United Nations’ General Assembly. Global Health and Foreign policy. Agenda item 123. The Sixty-seventh session (A/67/L.36). New York: United Nations; 2012.

World Health Organization. Sustainable health financing, universal coverage and social health insurance. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005.

WHO. World Health Report 2008 - primary health care - now more than ever. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

WHO. WHO | World Health Report 2013: research for universal health coverage. Genena: World Health Organization; 2013.

Reddy KS, Patel V, Jha P, Paul VK, Kumar AKS, Dandona L. Towards achievement of universal health care in India by 2020. A call to action. Lancet. 2011;377:760–8.

Gorin S. Universal health care coverage in the United States: Barriers, prospects, and implications. Health Soc Work. 1997;22:223–30.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Collet T-H, Salamin S, Zimmerli L, Kerr EA, Clair C, Picard-Kossovsky M, et al. The quality of primary care in a country with universal health care coverage. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:724–30.

O’Connell T, Rasanathan K, Chopra M. What does universal health coverage mean? Lancet. 2013;6736:13–5.

de Noronha JC. Universal health coverage: how to mix concepts, confuse objectives, and abandon principles. Cad Saúde Pública. 2013;29:847–9.

Kieny M-P, Evans DB. Universal health coverage. East Mediterr Health J. 2013;19:305-6.

Stuckler D, Feigl AB, Basu S, McKee M. The political economy of universal health coverage. In: Background paper for the global symposium on health systems research. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

Bärnighausen T, Sauerborn R. One hundred and eighteen years of the German health insurance system. Are there any lessons for middle-and low-income countries. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:1559–87.

Savedoff W, de Ferranti D, Smith A, Fan V. Political and economic aspects of the transition to universal health coverage. Lancet. 2012;380:924–32.

McKee M, Balabanova D, Basu S, Ricciardi W, Stuckler D. Universal health coverage: a quest for all countries but under threat in some. Value Health. 2013;16(1, Supplement):S39–45.

WHO. Constitution of the World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1948.

Declaration of Alma-Ata. International Conference on Primary Health Care, Al ma-Ata, USSR, 6–12 September 1978. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/113877/E93944.pdf . Accessed 4 May, 2015.

Bristol N. Global action towards Universal health coverage: a report for the CSIS Global Health Policy Center. Washington DC: Centre for strategic and International Studies; 2014.

Oxfam. Universal Health Coverage : Why health insurance schemes are leaving the poor behind. Oxford: Oxfam International; 2013.

World Bank WHO. WHO/World Bank Ministerial-level Meeting on Universal Health Coverage 18–19 February 2013. Geneva: World Health Organization’s headquarters; 2013.

WHO, World Bank. Monitoring Progress towards Universal Health Coverage at Country and Global Levels: A Framework. Joint WHO/World Bank Group Discussion Paper. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

World Bank, WHO. Towards Universal Health Coverage by 2030. Washington DC: World Bank Group; 2014.

Latko B, Temporão JG, Frenk J, Evans TG, Chen LC, Pablos-Mendez A, et al. The growing movement for universal health coverage. Lancet. 2011;377:2161–3.

Borgonovi E, Compagni A. Sustaining universal health coverage: the interaction of social, political, and economic sustainability. Value Health. 2013;16(1, Supplement):S34–8.

Kutzin J. Anything goes on the path to universal health coverage? No. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90:867–8.

Rodin J, de Ferranti D. Universal health coverage. The third global health transition? Lancet. 2012;380:861–2.

Chan M. Best days for public health are ahead of us, says WHO Director-General. Geneva, Switzerland: Address to the 65th World Health Assembly; 2012.

Lee Y-C, Huang Y-T, Tsai Y-W, Huang S-M, Kuo KN, McKee M, et al. The impact of universal National Health Insurance on population health: the experience of Taiwan. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:225.

Moreno-Serra R, Smith PC. Does progress towards universal health coverage improve population health? Lancet. 2012;380:917–23.

The World Bank. World Development Report 1993. Investing in Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993.

Book Google Scholar

Jamison DT, Summers LH, Alleyne G, Arrow KJ, Berkley S, Binagwaho A, et al. Global health 2035: a world converging within a generation. Lancet. 2013;382:1898–955.

Evans DB, Marten R, Etienne C. Universal health coverage is a development issue. Lancet. 2012;380:864–5.

D’Ambruoso L. Global health post-2015: the case for universal health equity. Global Health Action. 2013;6:19661.

Sheikh M, Cometto G, Duvivier R. Universal health coverage and the post 2015 agenda. Lancet. 2013;381:725–6.

United Nations. Adopting consensus text, General Assembly encourages member states to plan, pursue transition of National Health Care Systems towards Universal Coverage. In: Sixty-seventh General Assembly Plenary 53rd Meeting (AM). New York: Department of Public Information • News and Media Division; 2012.

Vega J. Universal health coverage. The post-2015 development agenda. Lancet. 2013;381:179–80.

Victora C, Saracci R, Olsen J. Universal health coverage and the post-2015 agenda. Lancet. 2013;381:726.

Sengupta M. Universal Health Coverage: Beyond rhetoric. In: McDonald DA, Ruiters G, editors. Municipal Services Project, Occasional Paper No 20 - November 2013. http://www.alames.org/documentos/uhcamit.pdf . Accessed 14 May, 2015.

Holmes D. Margaret Chan: committed to universal health coverage. Lancet. 2012;380:879.

Horton R, Das P. Universal health coverage: not why, what, or when—but how? Lancet. 2014;384:2101.

Article Google Scholar

Lagomarsino G, Garabrant A, Adyas A, Muga R, Otoo N. Moving towards universal health coverage: health insurance reforms in nine developing countries in Africa and Asia. Lancet. 2012;380:933–43.

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, WHO. The Right to Health: Joint Fact Sheet WHO/OHCHR/323. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007.

United Nations’ General Assemby. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: Adopted and opened for signature, ratification and accession by General Assembly resolution 2200A (XXI) of 16 December 1966 entry into force 3 January 1976, in accordance with article 27. New York: United Nations; 1966.

Young S, The U.S. Fund for UNICEF Education Department. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child: An Introduction -A Middle School Unit (Grades 6–8). U.S. Malawi: Fund for UNICEF/Mia Brandt; 2006.

United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. New York: United Nations; 2006.

United Nations General Assemby. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. New York: United Nations; 1979.

Bárcena A. Health protection as a citizen’s right. Lancet. 2014;6736:61771–2.

Scheil-Adlung X, Bonnet F. Beyond legal coverage: assessing the performance of social health protection. Int Soc Secur Rev. 2011;64:21–38.

Forman L, Ooms G, Chapman A, Friedman E, Waris A, Lamprea E, et al. What could a strengthened right to health bring to the post-2015 health development agenda?: interrogating the role of the minimum core concept in advancing essential global health needs. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2013;13:48.

Fried ST, Khurshid A, Tarlton D, Webb D, Gloss S, Paz C, et al. Universal health coverage: necessary but not sufficient. Reprod Health Matters. 2013;21:50–60.

Hammonds R, Ooms G. The emergence of a global right to health norm - the unresolved case of universal access to quality emergency obstetric care. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2014;14:4.

Kingston LN, Cohen EF, Morley CP. Debate: limitations on universality: the “right to health” and the necessity of legal nationality. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2010;10:11.

Yamin AE, Frisancho A. Human-rights-based approaches to health in Latin America. Lancet. 2014;6736(14):61280.

Rosen G. A History of Public Health. Maryland: John Hopkins University Press; 1993.

Wilkinson R, Marmot M. Social determinants of health. The solid facts. Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 1998.

Marmot M, Wilkinson R. Social determinants of health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005.

WHO. Social determinants of health: report by the Secretariat EB132/14. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012.

McIntyre D. Health service financing for universal coverage in east and southern Africa, EQUINET Discussion Paper 95. Harare: Regional Network for Equity in Health in East and Southern Africa (EQUINET); 2012.

Ooms G. From international health to global health: how to foster a better dialogue between empirical and normative disciplines. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2014; 14:36.

Backman G, Hunt P, Khosla R, Jaramillo-Strouss C, Fikre BM, Rumble C, et al. Health systems and the right to health: an assessment of 194 countries. Lancet. 2008;372:2047–85.

Ooms G, Latif LA, Waris A, Brolan CE, Hammonds R, Friedman EA, et al. Is universal health coverage the practical expression of the right to health care? BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2014; 14:3.

Ooms G, Hammonds R. Financing Global Health Through a Global Fund for Health? Working Group on Financing | PAPER 4. London: CHATHAM HOUSE (The Royal Institute of International Affairs); 2014.

Chen LC, Evans T, Cash R. Health as a global public good. In: Kaul I, Stern M, Grunberg I, editors. Global public goods: international cooperation in the 21st century. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999. p. 284–304.

Chapter Google Scholar

Frenk J, Gómez-Dantés O, Moon S. From sovereignty to solidarity: a renewed concept of global health for an era of complex interdependence. Lancet. 2014;383:94–7.

Stuckler D, McKee M. Five metaphors about global-health policy. Lancet. 2008;372:95–7.

Lencucha R. Cosmopolitanism and foreign policy for health: ethics for and beyond the state. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2013;13:29.

Knaul FM, González-Pier E, Gómez-Dantés O, García-Junco D, Arreola-Ornelas H, Barraza-Lloréns M, et al. The quest for universal health coverage: achieving social protection for all in Mexico. Lancet. 2012;380:1259–79.

The Lancet. Universal health coverage post-2015: putting people first. Lancet. 2014;384:2083.

Allotey P, Verghis S, Alvarez-Castillo F, Reidpath DD. Vulnerability, equity and universal coverage – a concept note. BMC Public Health. 2012;12 Suppl 1:S2.

Ravindran TS. Universal access: making health systems work for women. BMC Public Health. 2012;12 Suppl 1:S4.

Yates R. Universal health care and the removal of user fees. Lancet. 2009;373:2078–81.

McIntyre D. What healthcare financing changes are needed to reach universal coverage in South Africa? SAMJ: S Afr Med J. 2012;102:489–90.

Mills A, Ataguba JE, Akazili J, Borghi J, Garshong B, Makawia S, et al. Equity in financing and use of health care in Ghana, South Africa, and Tanzania: implications for paths to universal coverage. Lancet. 2012;380:126–33.

Rodney AM, Hill PS. Achieving equity within universal health coverage: a narrative review of progress and resources for measuring success. Int J Equity Health. 2014;13:1–72.

Goudge J, Akazili J, Ataguba J, Kuwawenaruwa A, Borghi J, Harris B, et al. Social solidarity and willingness to tolerate risk- and income-related cross-subsidies within health insurance: experiences from Ghana, Tanzania and South Africa. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27 suppl 1:i55–63.

Hickey S, Du Toit A. Adverse incorporation, social exclusion and chronic poverty, CPRC Working Paper 81. Chronic Poverty Research Centre: Manchester, UK; 2007.

Abiiro GA, Mbera GB, De Allegri M. Gaps in universal health coverage in Malawi: a qualitative study in rural communities. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:234.

Palmer N, Mueller DH, Gilson L, Mills A, Haines A. Health financing to promote access in low income settings—how much do we know? Lancet. 2004;364:1365–70.

Xu K, Evans DB, Kawabata K, Zeramdini R, Klavus J, Murray CJL. Household catastrophic health expenditure. A multicountry analysis. Lancet. 2003;362:111–7.

McIntyre D, Ranson MK, Aulakh BK, Honda A. Promoting universal financial protection: evidence from seven low-and middle-income countries on factors facilitating or hindering progress. Health Res Policy Syst. 2013;11:36.

Kutzin J, Ibraimova A, Jakab M, O’Dougherty S. Bismarck meets Beveridge on the Silk Road: coordinating funding sources to create a universal health financing system in Kyrgyzstan. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:549–54.

Xu K, Evans DB, Carrin G, Aguilar-Rivera AM, Musgrove P, Evans T. Protecting households from catastrophic health spending. Health Affair. 2007;26:972–83.

Cleary S, Birch S, Chimbindi N, Silal S, McIntyre D. Investigating the affordability of key health services in South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2013;80:37–46.

Moreno-Serra R, Millett C, Smith PC. Towards improved measurement of financial protection in health. PLoS Med. 2011;8, e1001087.

Dekker M, Wilms A. Health insurance and other risk-coping strategies in Uganda. The case of Microcare Insurance Ltd. World Dev. 2009;38:369–78.

Kruk ME, Goldmann E, Galea S. Borrowing and selling to pay for health care in low- and middle-income countries. Health Aff. 2009;28:1056–66.

Leive A, Xu K. Coping with out-of-pocket health payments: empirical evidence from 15 African countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:849–56.

Sachs JD. Achieving universal health coverage in low-income settings. Lancet. 2012;380:944–7.

Adam T, Hsu J, de Savigny D, Lavis JN, Røttingen J-A, Bennett S. Evaluating health systems strengthening interventions in low-income and middle-income countries: are we asking the right questions? Health Policy Plan. 2012;27 suppl 4:iv9–19.

PubMed Google Scholar

Rao KD, Ramani S, Hazarika I, George S. When do vertical programmes strengthen health systems? A comparative assessment of disease-specific interventions in India. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29:495–505.

Sustainable Development Solutions Network. Health in the framework of development: Technical Report for the Post-2015 Development Agenda. New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network: Global Inititative for the United Nation; 2014.

Aday LA, Andersen R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res. 1974;9:208–20.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Arnold C, Theede J, Gagnon A. A qualitative exploration of access to urban migrant healthcare in Nairobi, Kenya. Soc Sci Med. 2014;110:1–9.

Dillip A, Alba S, Mshana C, Hetzel MW, Lengeler C, Mayumana I, et al. Acceptability – a neglected dimension of access to health care: findings from a study on childhood convulsions in rural Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:113.

Ensor T, Cooper S. Overcoming barriers to health service access: influencing the demand side. Health Policy Plan. 2004;19:69–79.

Evans DB, Hsu J, Boerma T. Universal health coverage and universal access. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:546–546A.

Goudge J, Gilson L, Russell S, Gumede T, Mills A. Affordability, availability and acceptability barriers to health care for the chronically ill: longitudinal case studies from South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:75.

Jacobs B, Ir P, Bigdeli M, Annear PL, Damme WV. Addressing access barriers to health services: an analytical framework for selecting appropriate interventions in low-income Asian countries. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27:288–300.

Macha J, Harris B, Garshong B, Ataguba JE, Akazili J, Kuwawenaruwa A, et al. Factors influencing the burden of health care financing and the distribution of health care benefits in Ghana, Tanzania and South Africa. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27 suppl 1:i46–54.

McIntyre D, Thiede M, Birch S. Access as a policy-relevant concept in low- and middle-income countries. Health Econ Policy Law. 2009;4(Pt 2):179–93.

O’Donnell O. Access to health care in developing countries: breaking down demand side barriers. Cad Saúde Pública. 2007;23:2820–34.

Penchansky R, Thomas JW. The concept of access: definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med Care. 1981;19:127–40.

Silal SP, Penn-Kekana L, Harris B, Birch S, McIntyre D. Exploring inequalities in access to and use of maternal health services in South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:120.

Meessen B, Malanda B. No universal health coverage without strong local health systems. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92:78–78A.

Download references

Acknowledgement

GAA was funded by a scientific contract from the Institute of Public Health, University of Heidelberg, Germany, and a senior research assistant contract from the University for Development Studies, Ghana. MDA is fully funded by a core position in the Medical Faculty of the University of Heidelberg, Germany.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Public Health, Medical Faculty, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany

Gilbert Abotisem Abiiro & Manuela De Allegri

Department of Planning and Management, Faculty of Planning and Land Management, University for Development Studies, University Post Box 3, Wa, Upper West Region, Ghana

Gilbert Abotisem Abiiro

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Gilbert Abotisem Abiiro .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

GAA conceptualized and designed the study, undertook the literature search, data extraction and analysis, and drafted the paper. MDA supported the conceptualization and design of the study and paper drafting, and critically reviewed the drafts and contributed to its finalization. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Abiiro, G.A., De Allegri, M. Universal health coverage from multiple perspectives: a synthesis of conceptual literature and global debates. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 15 , 17 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-015-0056-9

Download citation

Received : 15 January 2015

Accepted : 29 June 2015

Published : 04 July 2015

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-015-0056-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Universal health coverage

- Multi-dimensional concept

- Rights-based

- Population coverage

- Financial protection

- Access to health services

- Health system

- Conceptual literature

- Global debates

BMC International Health and Human Rights

ISSN: 1472-698X

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Universal health coverage from multiple perspectives: a synthesis of conceptual literature and global debates

Affiliations.

- 1 Institute of Public Health, Medical Faculty, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany. [email protected].

- 2 Department of Planning and Management, Faculty of Planning and Land Management, University for Development Studies, University Post Box 3, Wa, Upper West Region, Ghana. [email protected].

- 3 Institute of Public Health, Medical Faculty, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany. [email protected].

- PMID: 26141806

- PMCID: PMC4491257

- DOI: 10.1186/s12914-015-0056-9

Background: There is an emerging global consensus on the importance of universal health coverage (UHC), but no unanimity on the conceptual definition and scope of UHC, whether UHC is achievable or not, how to move towards it, common indicators for measuring its progress, and its long-term sustainability. This has resulted in various interpretations of the concept, emanating from different disciplinary perspectives. This paper discusses the various dimensions of UHC emerging from these interpretations and argues for the need to pay attention to the complex interactions across the various components of a health system in the pursuit of UHC as a legal human rights issue.

Discussion: The literature presents UHC as a multi-dimensional concept, operationalized in terms of universal population coverage, universal financial protection, and universal access to quality health care, anchored on the basis of health care as an international legal obligation grounded in international human rights laws. As a legal concept, UHC implies the existence of a legal framework that mandates national governments to provide health care to all residents while compelling the international community to support poor nations in implementing this right. As a humanitarian social concept, UHC aims at achieving universal population coverage by enrolling all residents into health-related social security systems and securing equitable entitlements to the benefits from the health system for all. As a health economics concept, UHC guarantees financial protection by providing a shield against the catastrophic and impoverishing consequences of out-of-pocket expenditure, through the implementation of pooled prepaid financing systems. As a public health concept, UHC has attracted several controversies regarding which services should be covered: comprehensive services vs. minimum basic package, and priority disease-specific interventions vs. primary health care. As a multi-dimensional concept, grounded in international human rights laws, the move towards UHC in LMICs requires all states to effectively recognize the right to health in their national constitutions. It also requires a human rights-focused integrated approach to health service delivery that recognizes the health system as a complex phenomenon with interlinked functional units whose effective interaction are essential to reach the equilibrium called UHC.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Health Services Accessibility

- Internationality

- Universal Health Insurance*

- Open access

- Published: 04 January 2024

Building a resilient health system for universal health coverage and health security: a systematic review

- Ayal Debie ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5596-8401 1 , 4 ,

- Adane Nigusie 2 ,

- Dereje Gedle 3 ,

- Resham B. Khatri 3 &

- Yibeltal Assefa 3

Global Health Research and Policy volume 9 , Article number: 2 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1823 Accesses

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

Resilient health system (RHS) is crucial to achieving universal health coverage (UHC) and health security. However, little is known about strategies towards RHS to improve UHC and health security. This systematic review aims to synthesise the literature to understand approaches to build RHS toward UHC and health security.

A systematic search was conducted including studies published from 01 January 2000 to 31 December 2021. Studies were searched in three databases (PubMed, Embase, and Scopus) using search terms under four domains: resilience, health system, universal health coverage, and health security. We critically appraised articles using Rees and colleagues’ quality appraisal checklist to assess the quality of papers. A systematic narrative synthesis was conducted to analyse and synthesise the data using the World Health Organization’s health systems building block framework.

A total of 57 articles were included in the final review. Context-based redistribution of health workers, task-shifting policy, and results-based health financing policy helped to build RHS. High political commitment, community-based response planning, and multi-sectorial collaboration were critical to realising UHC and health security. On the contrary, lack of access, non-responsive, inequitable healthcare services, poor surveillance, weak leadership, and income inequalities were the constraints to achieving UHC and health security. In addition, the lack of basic healthcare infrastructures, inadequately skilled health workforces, absence of clear government policy, lack of clarity of stakeholder roles, and uneven distribution of health facilities and health workers were the challenges to achieving UHC and health security.

Conclusions

Advanced healthcare infrastructures and adequate number of healthcare workers are essential to achieving UHC and health security. However, they are not alone adequate to protect the health system from potential failure. Context-specific redistribution of health workers, task-shifting, result-based health financing policies, and integrated and multi-sectoral approaches, based on the principles of primary health care, are necessary for building RHS toward UHC and health security.

Resilient health system (RHS) is essential to ensure universal health coverage (UHC) and health security. It is about the health system’s preparedness and response to severe and acute shocks, and how the system can absorb, adapt and transform to cope with such changes [ 1 , 2 ]. Resilient health system reflects the ability to continue service delivery despite extraordinary shocks to achieving UHC [ 3 ]. A study in Nepal showed that adoption of coexistence strategy on the continuation of the international community on strengthening the health sector with the principle of “do-no-harm” and impartiality at the time of conflicts improve the health outcomes [ 4 ].

In 2015, the United Nations (UN) General Assembly adopted a new development agenda aiming to transform the world by achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030 [ 5 ], based on the lessons from the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) [ 6 ]. The SDGs seek to tackle the “unfinished business” of the MDGs era and recognise that health is a major contributor and beneficiary of sustainable development policies [ 7 ]. One of the 17 goals has been devoted specifically to health: “ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all ages” [ 6 ]. All UN Member States have agreed to achieve UHC (target 3.8) by 2030, as part of the SDGs [ 8 ]. The 2030 UHC target was intended to reach at least 80% for the UHC service coverage index and 100% for financial protection [ 9 ]. Universal health coverage is achieved when everyone has access to essential healthcare services without financial hardship associated with paying for care [ 10 ].

Universal health coverage and health security are two sides of the same coin. They are interconnected and complementary goals that require strong health systems and public health infrastructure to ensure that everyone has access to essential health services [ 11 ]. Universal health coverage and health security require an integrated and multi-sectorial system strengthening to provide quality and equitable healthcare services across populations [ 12 ].

A resilient health system provides the foundation for both [ 11 ]. Strengthening the World Health Organisation’s (WHO’s) six health system building blocks, including service delivery, health workforce, health information systems, health financing, leadership and governance, and access to essential medicines and infrastructures are essential to achieve UHC and health security [ 13 ]. The 13th WHO programme is structured in three interconnected strategic priorities to ensure SDG-3 including: achieving UHC, addressing health emergencies, and promoting healthier populations [ 14 ].

In the World Health Organisation (WHO) European Region, health security emphasises on the analysis of infectious diseases, natural and human-made disasters, conflicts and complex emergencies, and potential future challenges from global changes, particularly climate change [ 15 ]. Health security is also considered as the activities required, both proactive and reactive, to minimise the danger and impact of acute public health events that endanger people’s health across geographical regions and international boundaries [ 16 ]. The links between health system and health security have started to emerge in several national strategic plans and global initiatives, such as the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA) and One Health, which aim to better facilitate the implementation of the International Health Regulations (IHR) [ 17 ]. The aim of IHR is to prevent, detect, and respond to the international spread of disease in effective and efficient manner [ 18 ]. The GHSA also help countries to build their capacity to prevent, detect, and respond to infectious disease threats [ 19 ].

Although almost all nations are progressing towards UHC, the advancement in low and low-middle income countries (LLMICs) is slow [ 20 ]. This is because the ethos and organisations of many health systems are more suitable for yesterday’s disease burden than tomorrow [ 21 , 22 ]. Health systems of various nations faced numerous shocks, including public health, social, economic and political crises associated with COVID-19 [ 23 ]. The COVID -19 pandemic has made an unprecedented impact on the international community and exposed the vulnerabilities of the present global health architecture [ 24 ]. The COVID-19 pandemic is a perfect reminder that countries, individually and collectively, require a strong RHS now more than ever; however, there was no adequate evidence on the strategies toward RHS to improving UHC and health security. Thus, this study can inform the global health community on the lessons of RHS and its applications to UHC in pandemic and beyond. This review generally aimed to address the following research questions: 1) What are the existing evidence on the impact of RHS for UHC and health security? 2) What are the essential elements and characteristics of RHS for UHC and health security as per the WHO building blocks? and 3) What examples exist to demonstrate on how to build RHS core components for UHC and health security?

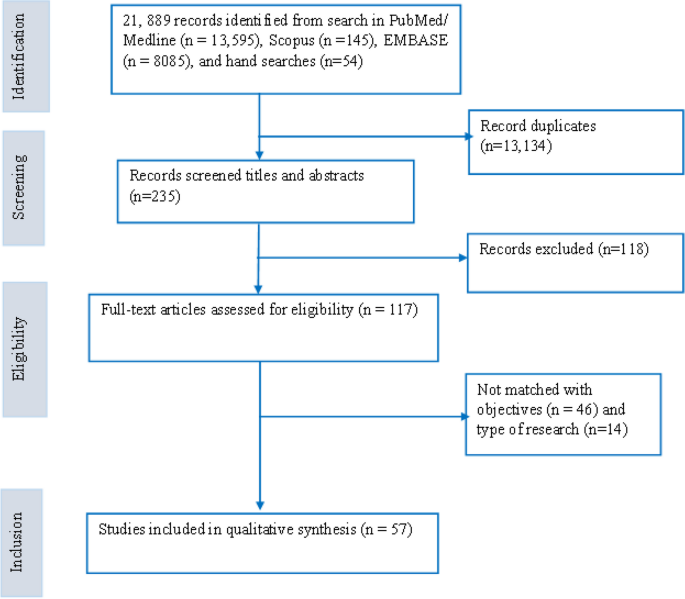

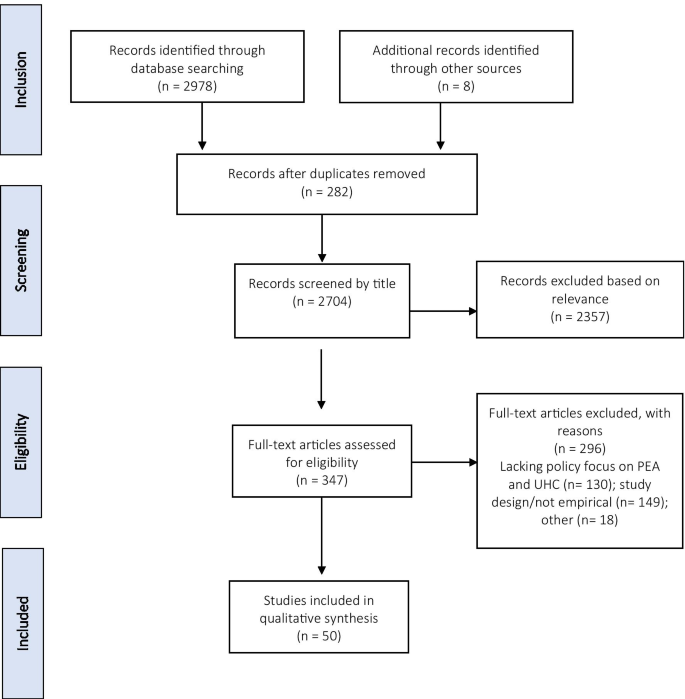

Registration and search strategy

This review was conducted and reported following enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research (ENTERQ). Following ENTERQ guidelines, the systematic review was registered with the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) on 02 January 2022 with registration: CRD42020210471. Studies were searched in three databases (PubMed, Embase and Scopus) using search terms of under four broader domains, including resilience, health system, universal health coverage, and health security. Additional literatures were identified by searching in Google and Google Scholar. The search strategies were built using the four domains of search terms, and “Title/Abstract” by linking “AND” and “OR” Boolean operator terms as appropriate (Additional file 1 ). We also used the ENTERQ checklist for reporting the articles (Additional file 2 ).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All articles in relation to RHS towards UHC and health security were included in the review. Inclusion criteria were articles written in the English language published from 01 January 2000 to 31 December 2021. Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies were eligible for inclusion. Exclusion criteria were perspectives, commentary, expert’s opinion, conference papers, debates, conference reports, letters to the editor, and editorials. We presented this paper as a narrative review, following some components of the preferred reporting of systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA) guideline for scoping review (Additional file 3 ).

Selection process

The primary author (AD) imported all retrieved articles into the Endnote library to remove duplicates. After removing the duplicates, three authors (AD, AN and DG) independently screened the articles by title and abstract based on inclusion criteria. The senior authors (RBK and YA) mediated the discrepancies between the three reviewers through discussion. Finally, we retained and reviewed the full texts of all relevant studies for final data synthesis.

Data extraction and framework for synthesis

We used the Rees and colleagues’ appraisal instrument as a guiding tool to appraise the quality of included articles in the review [ 25 ]. The quality appraisal instrument is a comprehensive tool designed to assess the quality, rigor of research studies, covers key aspects of research design, data collection, analysis, and reporting. This includes rigour in sampling, rigour in data collection, rigour in data analysis, findings supported by the data, breadth and depth of findings, extent of the study privilege perspectives, reliability or trustworthiness, and usefulness[ 25 ]. A template was developed to extract relevant data from each eligible study. After reading the selected studies, key findings were extracted into the template, including information about the first author, year of publication, type of article, study design, and key summary findings. Three independent reviewers (AD, AN and DG) extracted the data. The senior authors (RBK and YA) verified the extracted information. The successes and challenges of RHS for UHC and health security were extracted using health system building blocks.

We analysed the findings using the WHO health system building blocks, including service delivery, health workforce, health information systems, medicines and infrastructures, healthcare financing, and leadership and governance [ 13 ]. We analysed the key challenges and successes of RHS for UHC and health security using the WHO health system frameworks. Framework analysis provides a systematic approach to analysing large amounts of textual data using pre-determined framework components. This allows the analyst and those commissioning the research to move between multiple layers of abstraction without losing sight of raw data [ 26 ].

Search results

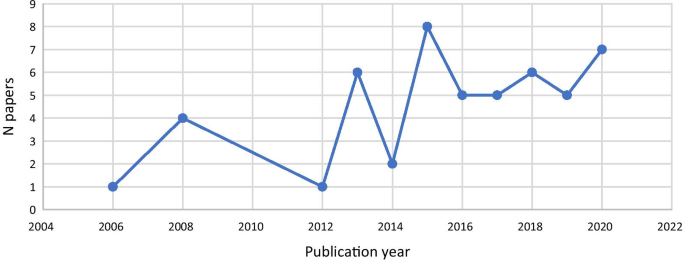

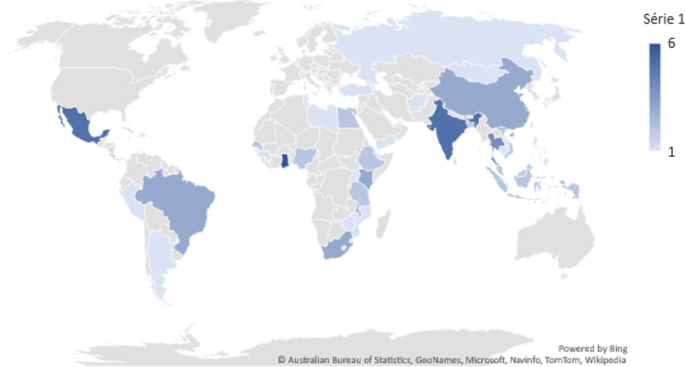

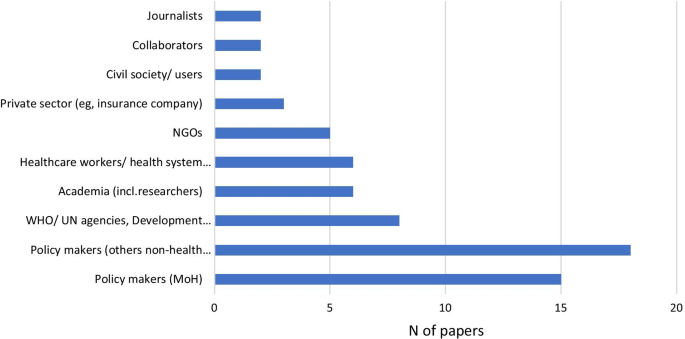

A total of 21,889 records were identified in the initial literature search. After removing 13,134 duplicates, 235 articles were screened by titles and abstracts, and 118 were excluded. Next, 117 studies were reviewed using the full texts, and finally, 57 articles met the inclusion criteria and were analyzed in the systematic review (Fig. 1 ). Of these, 32 articles were primary studies, and 25 articles investigated the application of RHS on UHC. In addition, nine articles explained RHS's implications on UHC and health security. Of these, approximately one-third (19 articles) were conducted in various African nations, while 19 articles were from Asian countries. The remaining articles were from other parts of the world. The study also reviewed articles on various aspects of health system building blocks, including health service delivery, health workforce, health information systems, health financing, leadership/governance, and medicines and infrastructure. The number of articles reviewed for each aspect were 17, 9, 10, 13, 22, and 10, respectively.

ENTREQ flow diagram for the articles included in the review

Successes and challenges of RHS

This review used the six-health system building blocks to achieve UHC and health security. These include service delivery, health workforce, health information system, health financing, medicines, diagnostics and infrastructures, and leadership and governance (Table 1 ).

Service delivery

Of the total reviewed articles, 17 described their healthcare service delivery findings. Good service delivery provides comprehensive and person-centered healthcare services with full accountability [ 27 ]. Continuation of healthcare service delivery in the face of extraordinary shocks facilitated UHC progress [ 3 ]. Studies reported that health service inputs, access to transportation, communication infrastructures, capacity building, referral systems, intersectoral actions, and electronic healthcare platforms could facilitate service delivery and improve access to health services [ 13 , 28 ]. Operational integration between health service continuity and emergency response through proactive planning across all income nations reduced health services disruptions during emergencies [ 29 ]. Community resources, cohesion, and physical accesses were significant assets to improve service utilisation and quality [ 30 ].

An inward migration or mass casualty incidents compromised the quality of services and increased deaths attributed to delays in treatment [ 30 ]. In the Ebola crisis, the long-standing lack of access to basic primary health care to isolate and treat infected people fueled the epidemic’s spread resulting in a death toll [ 31 ]. Uneven health facilities distribution and lack of well-trained personnel and supplies led to geographical inequities and poor healthcare access [ 32 , 33 ]. A combination of public health security threats, both new and reemerging infectious diseases, challenged ensuring health security [ 34 ]. For example, the health service delivery, mainly the lives of many children, was at risk associated with the lack of treatment for common childhood illnesses in Liberia during the Ebola outbreak [ 35 , 36 ]. Exclusion from work due to health problems can easily result in economic impoverishment and inequitable healthcare access, which will undoubtedly worsen health status [ 37 ]. For instance, socially excluded population groups received health services from a dysfunctional publicly provided health system marked by gaps and often invisible barriers in Guatemala and Peru, which undermines the progress towards UHC [ 38 ]. The changes in frequency, intensity, spatial extent, duration, and timing of extreme weather and climate events were also exposed to health threats [ 39 ]. For example, extreme weather events caused an increase in disease prevalence, such as malaria and other vector-borne diseases, malnutrition, food insecurity and food-borne diseases [ 40 ]. Inadequate primary health care system capacity to provide responsive health services to storm and flood-related health problems was another challenge [ 41 ].

Health workforce

In our review, nine articles reported their findings on the successes and challenges of health workforces towards UHC and health security. A well-performing health workforce provides responsive, fair and efficient health services to achieve the best health outcomes [ 27 ]. Task-shifting policy, ensuring accountability and ad hoc redistribution of health workers had a knock-on effect on health services delivery and building RHS [ 42 , 43 , 44 ]. Training on disaster preparedness and management, and rewarding packages, such as incentives and hazard allowance, facilitated healthcare workers willing to participate in disaster management [ 45 ]. Monitoring and evaluating frontline health workers levels of preparedness against public health emergency threats periodically by their higher-level hierarchy was crucial for early detection and control of health threats [ 46 ].

Lack of skilled and inadequate health workforce distribution was the major obstacle to containing an outbreak, and deaths were attributed to treatment delays [ 35 , 43 ]. Low perception of risks by tourists/ pilgrims, ineffective training, poor control of risk factors, and shortages of infrastructures were the challenges in combating contagious diseases [ 47 ]. Healthcare workers’ practices on effective pandemic management, including corona-virus disease (COVID)-19 were constrained by individual factors, such as education, residence, work station location, hygiene promotion, and social distance management [ 42 ]. Patient assessments by non-indigenous health workers during an emergency were also barriers to early identification and management of acute health events [ 30 ].

Health information system

In this review, ten articles described the contributions and challenges of health information on RHS to realise UHC and health security. A well-functioning HIS ensures the production, analysis, dissemination and use of reliable information for policy decisions [ 27 ]. Building accountability, knowledge culture management, and evidence through regular data quality audit strengthened health management information systems (HMIS) [ 44 ]. Integrated disease surveillance, flexible automation and data processing improved clinical care and health system preparedness to tackle health threats [ 48 , 49 , 50 ]. Strengthening the health system’s capacity was another key measure to rapidly process and communicate test results for pandemic responses [ 51 ].

Poor surveillance, late timing of responses and lack of triggers weakened the functionality of plans and exposed to a high burden of diseases [ 52 ]. Poor data management, misinformation on the risk and transmission, lack of awareness, resources and insufficient electronic reporting system were responsible for the spread of diseases [ 51 , 53 , 54 ]. For instance, misinformation during the Ebola outbreak affected most communities in putting measures in place to stop the spread of the virus [ 54 ]. People approached traditional healers who lacked knowledge on treating certain health shocks in modern medicine was the major problems in early responses [ 35 ].

Medical products, diagnostics, and infrastructures

Of the reviewed articles, 10 reported their findings on the successes and constraints of medical products, diagnostics, and infrastructures to realise UHC and health security. Equitable access to essential medical products, vaccines and technologies to assure quality, safety, efficacy and cost-effective healthcare services to users was the attribute of a well-functioning health system [ 27 ]. To attain UHC, strengthening local preparedness, planning, manufacturing, and coordinating public–private initiatives and training in LMICs was important [ 55 ]. The key factors to facilitate early detection were the provision of rapid, cost-effective, sensitive, and specific diagnostic centers through the inauguration of national centers [ 53 , 56 ]. Identifying emergency medicines, adaptable mobile health care units and systems for mobilisation of health professionals contributed to successful interventions to curb health emergencies [ 57 ].

High patient load, lack of diagnostics, destruction of health facilities and lack of specific funds for medicine procurement may compromise the health system’s hardware (health facilities and supplies) and contained public health threats [ 3 , 30 , 32 , 57 ]. For instance, inadequate essential logistics such as blood, oxygen cylinders, ergometrine and sulphadoxine paramita mine in Ghana was the causes for low level of preparedness to control maternal mortality [ 58 ]. Shortages of medical supplies, personal protective equipment (PPE), and electricity increased the rate of Ebola infections during the outbreak [ 35 ]. Most medicine outlets experienced longer lead times associated with the poor inter-country transportation and limited manufacturing capacity, which were also Namibia's main challenges [ 55 ].

Health financing

In this study, 13 articles described their findings on the contributions and limitations of healthcare financing to realise UHC and health security. A good health financing system raised adequate funds for health to ensure people can use needed services and be protected from financial catastrophes [ 27 ]. Under a publicly funded health financing system that fits well with values and population preferences improved compliance, sustainability, and equity [ 59 ]. An integrated financing mechanism through high income and risk cross-subsidies reduced reliance on OOP payments, maximises risk pools and resource allocation mechanisms facilitated to achieve UHC [ 60 ]. Universal health coverage can substantially improve human security through securing finances [ 61 ]. Universal health coverage indicators were also positively associated with the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita and the share of health spending channels [ 62 ]. Income redistribution improved equity in health care service delivery [ 63 ].

Lack of adequate funds and non-affordable medical costs were the main barriers to universal financial protection and poor management of an outbreak [ 33 , 35 ]. In Burundi, for example, performance-based financing without accompanying access to incentives for the poor was the critical challenge to improve equity in health [ 64 ]. Health equity advancement challenges secured dedicated funds to support transformative learning opportunities and build infrastructures [ 65 ]. Because of causalities, the health sector requires additional financial support to address the increased demand for health services; however, movement restrictions limit people’s access to participate in gainful activities [ 30 ]. Low funds from international donors were erratic and far below the amounts required to meet the health needs at crisis time [ 66 ]. People could not trade their commodities because of the fear of attacks exposing service users to lack finances [ 30 ]. Falling in financial access to health services has resulted in political demonstrations and violent unrest [ 67 ].

Leadership and governance

Our review found that 22 articles reported their findings on health system governance (HSG) to realise UHC and health security. Good HSG ensured strategic policy frameworks combined with effective oversight, coalition, appropriate regulations, system design and accountability [ 27 ]. Building strong partnerships, ensuring accountability, coordination, rationalisation, and connection of pandemic planning across sectors and jurisdictions resulted in better preparedness [ 48 , 68 ]. Clear communication channels, multisectoral, and multilevel controls were essential to translate policy into actions [ 52 , 56 ]. Vertical and horizontal integration, centralised governance, responsible leadership, and social capital at community level were needed to address health shocks and homogenous implementation of health interventions [ 54 , 69 , 70 ]. Fueling high-performing teams and increasing investment in early warning and detection systems required leadership resilience to enable action at all levels [ 71 , 72 ].

Working alone the state had proven only partially effective, a situation exacerbated by the natural tendency within the public to ignore as irrelevant to themselves [ 73 ]. In addition, lack of clarity of stakeholder roles, poor leadership and absence of clear government policy for the delivery channels and financial coverage led to fragmentation and poor health system response [ 35 , 52 , 66 ]. For instance, weak governance and decision-making processes, such as high bureaucracy, low prevention culture, and lack of coordination between primary, social and hospital care providers, indicated virus’s rapid spread in the French population in the first wave of COVID-19 [ 74 ].

Moving away from a one-size fits-to all approach in guiding pandemic response, service delivery, political commitment, fair contribution and distribution of resources are helpful to speed up the path towards UHC [ 75 ]. For example, village health volunteers in Thailand, Zanmi Lazante’s Community Health Program in Haiti, Agentes Polivalentes Elementares in Mozambique, Village Health Teams in Uganda, lady health workers in Pakistan, BRAC in Bangladesh, Family Health Program in Brazil, and Health Extension Program in Ethiopia are successful community-based models contributed immensely to achieve health development goals [ 76 ]. In addition, community participation and coordination between different stakeholders significantly impact the prevention of encephalitis in Japan [ 77 ], and early detection of cases and collection of mortality data in Cambodia [ 78 ]. On the contrary, it was difficult for the system to automatically adjust its structure to reduce uncertainty and ascertain complex adaptive behaviour when facing public health emergencies [ 79 ].

With an overarching political will, well-integrated and locally grounded health system can be more resilient to external shocks [ 80 ]. Political leadership was critical during the crisis, which helped the government to develop a response strategy and effective implementation [ 81 ]. For instance, Singapore’s dexterous political environment allowed the government to institute measures to control COVID-19 swiftly [ 56 ]. On the other hand, political instability or war in Syria affected healthcare services by destroying physical health care infrastructures [ 3 ].

In this review, we developed a resilient health system framework that could assist countries in their endeavor toward universal health coverage and health security. The framework involves an integrated and multi-sectoral approach that considers the health system building blocks and contextual factors. The input components of the framework include health financing, health workforce, and infrastructure, while service delivery is the process component, and UHC and health security are the impact program components. The framework also considers health system performance attributes, such as access, equity, quality, safety, efficiency, sustainability, responsiveness, and financial risk protection. Additionally, the cross-cutting components of the framework are leadership and governance, health information systems (HIS), and contextual factors (e.g., political, environmental/climate, socioeconomic, and community engagement) that can affect the health system at any stage of the program components (Fig. 2 ).

Resilient health system framework for UHC and health security

We also indicated that RHS is critical to achieving UHC because it enables the provision of accessible, quality, and equitable health services, while also protecting people from financial risks associated with illness or injury. Such systems are built on strong primary healthcare services, effective governance and leadership, adequate financing, reliable health information systems, and a well-trained and motivated health workforce [ 42 , 43 , 44 ]. Resilient health systems are better equipped to deliver high-quality healthcare services to all people, including those who are marginalised or living in poverty. This, in turn, investing in RHS is essential for achieving UHC, promoting health equity, and building more sustainable and equitable societies. On the contrary, lack of healthcare access, skilled health workforces, and uneven distribution of health facilities and health workers [ 32 , 33 , 35 , 43 ] were the challenges to achieving health sector goals.