- Services Paper editing services Paper proofreading Business papers Philosophy papers Write my paper Term papers for sale Term paper help Academic term papers Buy research papers College writing services Paper writing help Student papers Original term papers Research paper help Nursing papers for sale Psychology papers Economics papers Medical papers Blog

180 Art Research Topics To Wake Your Inner Creator Up

We know, finding great art research topics can be a pretty difficult thing to do nowadays. Your classmates are all scouring the Internet in search of easy – but interesting – topics. The last thing you want is to pick a topic that has already been chosen. You want to be original. You want your professor to notice the effort you’ve put into finding the perfect topic. This is why you should take a look at our list of art research topics. All of them are original and interesting. And, best of all, the list is updated and new topics are added periodically.

Writing a Proper Art Research Paper

Writing a research paper on a topic in painting, sculpture, literature, architecture, cinema, music, or theater can be tricky if you don’t have much experience. To come to your aid, we have included a short list of tips that should help you write the best possible art research paper as quickly as possible:

Obviously, you need to find an engaging topic for your paper Spend some time on crafting the thesis statement (it’s very important) Only use information from authoritative sources that you can check Make sure all citations and references are properly formatted It pays to start your writing project with an outline Stay organized and follow the outline until you finish the paper Don’t forget to edit your work and then proofread it thoroughly Finally, don’t forget that you can get professional academic writing help, if necessary

In this blog post, we will help you with a list of 180 original art research topics for your next paper. The topics, organized in 20 categories, can be found below and are 100% free. Furthermore, if you have more important things to do, rather than going through that long and boring process, you can pay someone to write a paper and feel free to spend your time as you wish.

Brand New Art Topics for Research Papers

Below, you can find our brand new art topics for research papers. All of these topics have been recently added and we think that all of them should work great in 2023:

- Compare 2 major themes of art

- Discuss the adversity theme in art

- Is digital 3D motion graphic design an art?

- Discuss artistic styles in modern art

- An in-depth look at digital art

- Social media in 2023 art

- Talk about the popularity of art fairs

- Should you become an art historian?

- Peculiarities of abstract art of the 21st century

- Talk about Cubism influences in art

- What is mixed media art?

Artist Research Paper Ideas

Would you like to talk about artists? No problem, we’ve got an entire list of artist research paper ideas for you right here. Choose the best one and start writing in minutes:

- The life and work of Jean-Michel Basquiat

- The importance of Peter Doig’s work

- Modern paintings by Christopher Wool

- Influences in Rudolf Stingel’s art

- An in-depth look at Salvador Dali’s work

- The neo-Pop movement (Yoshitomo Nara)

- Richard Prince’s use of mass-media images in art

- The instability of life in Zeng Fanzhi’s paintings

- The life and work of Frida Kahlo

- Andy Warhol’s rise in popularity

- Discuss the themes in Vincent van Gogh’s work

- The importance of Jackson Pollock for modern art

Art History Research Paper Topics

If you want to talk about art history, you will be thrilled to learn that we are offering a list of art history research paper topics for free. Check out the latest version of the topics list:

- Imagery and symbolism in Carlo Crivelli’s work

- Talk about evolution and devolution in Willem de Kooning’s work

- An in-depth look at Chinese art

- The 3 most important architecture themes

- Talk about the portrayal of war in contemporary art

- The most important literary works of the 20th century

- European art during Medieval times

- The importance of prehistoric art in Mesopotamia

Art Topics to Write About in High School

Are you looking for some art topics to write about in high school? Don’t worry about it; we’ve got your back. We have a whole list of topics dedicated to high school students right here:

- Talk about the use of symbols in Egyptian art

- Discuss Mayan architecture

- An in-depth look at Chinese ancient paintings

- Light in Claude Monet’s work

- Talk about the peculiarities of Romanticism

- Discuss the Surrealism movement

- The importance of the Sistine Chapel paintings

- A closer look at the Harlem Renaissance

Most Interesting Art Topics

We know you want to write a paper on something interesting. After all, you probably want to impress your professor, don’t you? Here are our most interesting art topics:

- Discuss peculiarities of Iranian cinema movies

- Talk about Hindi architecture

- Best Chinese novels ever written

- Artistic similarities between the US and Canada

- Talk about a famous painter in the United Kingdom

- The ascendance motif in Raphael’s work

- Talk about feminism in contemporary art

- Japanese motifs in Claude Monet’s paintings

Advanced Art Topics

We are most certain that your professor will appreciate the effort if you choose to write your paper on a more complex topic. Here are some advanced art topics you could try:

- The emergence of urban street art

- Cubism in Pablo Picasso paintings

- The life and works of Louise Bourgeois

- Talk about the influence of the paranormal on art

- An in-depth look at Aztec religious art

- Talk about a primeval music instrument of your choice

- Talk about sculpture in Ancient Rome

- Discuss the use of art for propaganda means

Fun Art Topic Ideas

Who said writing a research paper about art can’t be fun? It all depends on the topic you choose. To help you out, we have compiled a list of fun art topic ideas. Check it out below:

- Depictions of extraterrestrials in art

- Using art during the war

- 3 most creative uses of paintings

- Talk about the emergence of NFT art

- Interesting traits of the Bauhaus movement

- Sculptures that make you laugh

- Interesting depictions of the human anatomy

- The most famous graffiti in the United States

Art Topics Good for College Students

Of course we have many art topics that are good for college students. Our experts have recently finished updating the list of ideas, so go ahead and choose the one you like the most:

- Analyze the Surrealism period

- Postmodernism in 2023 art

- The life and work of Auguste Renoir

- Talk about French caricatures

- The benefits of art therapy

- Hitler and his contribution to arts

- War dances in the Maori society

Controversial Art Topics to Write About

M any students find writing a research paper challenging. There are many controversial topics in art that you can talk about in a research paper. Take a look at some of the most controversial art topics to write about and take your pick:

- Discuss The Last Judgement by Michelangelo

- The controversies surrounding Marcel Duchamp

- Graffiti: vandalism or art?

- Why is art so controversial?

- What makes a drawing a piece of art?

- Architecture: art or utility?

Easy Topics for Art Papers

If you want to spend as little time as possible writing the research paper, you need an easier topic. Fortunately for you, our experts have compiled a list of easy topics for art papers right here:

- Types of Chinese jewelry

- Analyze art in South Korea

- The first recorded music instrument

- Discuss a novel of your choice

- Talk about Venetian carnival masks

- The life and works of Giuseppe Verdi

- Compare and contrast 3 war dances

- American Indian art over the years

- An in-depth look at totem masks

- Art in sub-Saharan Africa

- Talk about art in North Korea

Modern/Contemporary Art History Topics

Yes, we really do have a list of the best modern/contemporary art history topics. As usual, you can choose any of our topics and even reword it without giving us any credit. Take your pick:

- Talk about 5 artistic styles in modern art

- Talk about activism and art

- Discuss the role of political cartoons

- The role of digital art in 2023

- Is printmaking really an art?

- Discuss the theme of identity politics

- Political critique through the use of art

- Most interesting works of contemporary art

Ancient Art Topics

Do you want to talk about ancient art? It’s not a simple subject, but we’re certain you will manage just fine. Check out our latest list of ancient art topics and select the one you like the most:

- Analyze the El Castillo Cave Paintings

- Ancient art in India

- An in-depth look at the Diepkloof Eggshell Engravings

- Ancient art in Persia

- Why is ancient art so important?

- Ancient art in China

- What makes ancient art unique?

Ideas for an Art Research Project

Did your teacher ask you to come up with an idea for an art research project? Don’t worry about it too much because we have plenty of ideas for an art research project right here:

- Research 3 Kpop artists and their work

- Uncover signs of prehistoric art in your area

- Make a rain painting on your own

- Design a Zen garden in your backyard

- Make a 3D sculpture on your computer

- Make a wall mural for your school

- Experiment with pin art

- Experiment with sand art

Fine Arts Research Paper Topics

If you would prefer to write about the fine arts, you have definitely arrived at the right place. We have a long list of interesting fine arts research paper topics below:

- Is drawing a form of art?

- An in-depth analysis of the Mona Lisa

- The Girls with a Pearl Earring painting

- An in-depth analysis of Venus of Willendorf

- A closer look at the Terracotta Army

- Discuss a piece of abstract architecture

- A closer look at the Burj Khalifa architecture

- Discuss Ode to a Nightingale by John Keats

Renaissance Art Topics

Did you know that our Renaissance art topics have been used by more than 500 students to date? This is a clear indication that our ideas are some of the best on the Web:

- Talk about the Linear perspective in Renaissance art

- Discuss the altarpieces found in Renaissance art

- An in-depth look at anatomy in Renaissance art

- Discuss the Fresco cycles

- Talk about the peculiarities of the landscape

- Influences of Realism in Renaissance art

- Analyze the use of light in Renaissance art

- Discuss the humanism theme

- Talk about the individualism theme in Renaissance art

The Best Baroque Art Topics

We can assure you that you teacher will greatly appreciate it if you choose one of these Baroque topics. Remember, this is the place where you can find the best Baroque art topics:

- Discuss the Grandeur theme in Baroque art

- An in-depth look at the sensuous richness theme

- Talk about the importance of religious paintings

- Talk about the emotional exuberance theme

- Allegories in Baroque art

- The life and works of Annibale Carracci

- The life and works of Nicolas Poussin

Art Debate Topics

Are you planning an art debate? If you are, you most definitely need some great art debate topics to choose from. Talk to your team and propose them any of these awesome ideas:

- Do artists need talent to sculpt?

- The best painter in the world today

- Can graffiti be considered a form of art?

- The best sculpture ever made

- Can we consider dance a form of art?

- The best painting ever made

- Should we study arts in school?

- The best literary work ever written

- Why is Banksy’s work so controversial?

- The best singer of all time

- How can photographs be considered works of art?

Artist Biography Topics

Our experts have put together a list of the most intriguing artist biography topics for you. You should be able to find more than enough information about each artist on the Internet:

- Talk about the life of Michael Jackson

- Discuss the works of Leonardo da Vinci

- Discuss the importance of Elvis Presley’s work

- The life and works of Rembrandt

- The importance of Ernest Hemingway’s masterpieces

- The importance of Michelangelo’s paintings

- Talk about the life of Vincent van Gogh

- Auguste Rodin’s sculptures

- The life and works of Donatello

- The life and works of Leo Tolstoy

- Discuss Jane Austen’s literary works

Art Therapy Topics

Choosing one of our captivating art therapy topics will definitely get your research paper noticed. This is a field that has been growing in popularity for years. Check out our latest ideas:

- The importance of photography in art therapy

- Reducing pain through art therapy

- Art therapy for PTST patients

- Art therapy against the stress of the modern world

- Improving the quality of life through art therapy

- Positive health effects of finger painting

- The effects of art therapy on 3 mental health disorders

- The effects of art therapy on autism

- Art therapy and psychotherapy

- The job of an art therapist

- Benefits of art therapy for mental health

Art Epochs Paper Topics

If you want to write your paper on one of the many art epochs, you could give our art epochs paper topics a try. You should find plenty of great ideas in the list below:

- The legacy of the Romanesque period

- The importance of the Romanticism movement

- Talk about the Mannerism movement

- Discuss The New Objectivity movement

- Pop-art in the 21st century

- An in-depth look at abstract impressionism

- The importance of the Gothic Era

- Talk about the Classicist movement

- Peculiarities of Cubism art

- What is Futurism in art?

- Discuss the great artists of the Baroque era

- Interesting facts about the Rococo period

- The Art Nouveau era

Paper Writing Service You Can Rely On

Our affordable experts are ready to spring into action and help you write an exceptional art research paper in no time (in as little as 3 hours). Yes, we really are as fast and trustworthy as people say. Just take a look at our stellar reviews and see for yourself. We are the research paper writing service you need if you want to buy research papers. Every student can get the help he requires in minutes, even during the night and during holidays. Our reliable ENL writers can write you a custom art paper for any class. And remember, all of our essays are 100% written from scratch. This means that all our work is completely original (a plagiarism report will be sent to you for free with every paper). What are you waiting for? Contact us with a “ do my research paper ” request and get a paper on art online from our team of experienced writers and editors and get the top grade you deserve!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Terms & Conditions Loyalty Program Privacy Policy Money-Back Policy

Copyright © 2013-2024 MyPaperDone.com

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you’re on board with our cookie policy

- A Research Guide

- Research Paper Topics

25 Arts Research Paper Topics

- Ancient Roman art

- African architecture

- The works of Lysippos

- Bauhaus movement

- The transition to the Renaissance

- The art of ancient Egypt

- Expressionists and their impact on modern art

- Fine art and folk art

- Gothic and Neo-Gothic

- Comparison of Nazi and Soviet art

- Surrealist movement

- Censorship in the works of art

- Art as propaganda

- Can abstract art be decoded?

- Photography as art

- The rise of digital art

- Venetian carnival as an art performance

- The history of the art of dance

- Hollywood and Bollywood

- The beauty standards in the art

- Rock music as neoclassical art

- The art of disgusting

- Computer games as art

- Art therapy

By clicking "Log In", you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We'll occasionally send you account related and promo emails.

Sign Up for your FREE account

Forget about ChatGPT and get quality content right away.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 23 June 2022

The role of expertise and culture in visual art appreciation

- Kohinoor M. Darda 1 , 2 , 3 &

- Emily S. Cross 1 , 2 , 4

Scientific Reports volume 12 , Article number: 10666 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

8 Citations

7 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

Is art appreciation universal? Previous evidence suggests a general preference for representational art over abstract art, and a tendency to like art originating from one’s own culture more than another culture (an ingroup bias), modulated by art expertise. However, claims about universality are difficult given that most research has focused on Western populations. Across two pre-registered and statistically powered experiments, we explore the role of culture and art expertise in the aesthetic evaluation of Indian and Western paintings and dance depicting both abstract and representational content, by inviting expert and art-naïve Indian and Western participants to rate stimuli on beauty and liking. Results suggest an ingroup bias (for dance) and a preference for representational art (for paintings) exists, both modulated by art expertise. As predicted, the ingroup bias was present only in art-naïve participants, and the preference for representational art was lower in art experts, but this modulation was present only in Western participants. The current findings have two main implications: (1) they inform and constrain understanding of universality of aesthetic appreciation, cautioning against generalising models of empirical aesthetics to non-western populations and across art forms, (2) they highlight the importance of art experience as a medium to counter prejudices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Bias against AI art can enhance perceptions of human creativity

C. Blaine Horton Jr, Michael W. White & Sheena S. Iyengar

The impact of contextual information on aesthetic engagement of artworks

Kohinoor M. Darda & Anjan Chatterjee

The mediating effect of the need for cognition between aesthetic experiences and aesthetic competence in art

Agata H. Świątek, Małgorzata Szcześniak, … Marianna Chmiel

Introduction

Across millennia, humans have expressed themselves through the medium of art. Art is often considered to be a society’s collective memory, preserving what fact-based historical records may not be able to—how it felt to exist in a particular time and in a particular space. More recently, the function of art to communicate and soothe, and to bring people together has been emphatically highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Whether it is people singing to each other from their balconies 1 , musicians performing orchestral works over Zoom 2 , or artists tapping into their creativity to explain public health guidelines 3 , art has given hope and provided much-needed human connection, across geographic, racial, and cultural boundaries. In a world facing increasing societal stresses due to racism, political polarisation, xenophobia, and other geostrategic fractures, art proves its ability to bring people together.

In the words of Danish-Icelandic contemporary artist Olafur Eliasson, art “… helps us identify with one another and expands our notion of we—from the local to the global” 4 . Engagement with art is not always a solitary event. Instead, it represents one of the few areas in society where people can come together to share experiences even when they have radically different beliefs or worldviews. But to what extent can art really bind us together, and can it transcend boundaries of culture or country? Do we share much more than what divides us? Or do our in-group biases and preferences persist when watching dance performances or viewing paintings?

The degree to which aesthetic preferences are universal or shared across cultures, as opposed to being highly individual in nature and moderated by our in-group biases is an important question in empirical aesthetics. To date, however, little insight has been gained into the universality of psychological underpinnings of aesthetic appreciation, as most research has exclusively examined perceptions and preferences among Western European and North American populations 5 . Moreover, influence of the visual properties of the artwork (such as its content), as well as observers’ attributes (such as their culture or art expertise) on aesthetic preferences have been extensively studied for the fine arts (including paintings, drawings and sculpture), while our knowledge of such attributes for other artforms remains limited (e.g., 6 , 7 , 8 ). This is somewhat surprising, given the ubiquity and importance of a range of artforms beyond the fine arts, including music, theatre, poetry, and dance, across many cultures. The current work attempts to begin to bridge several of these considerable gaps in knowledge regarding the human aesthetic experience by one, evaluating whether universal primitives underpin people’s appreciation in fine and performing arts; and two, examining the extent to which cultural background shapes these preferences. To accomplish this, we have combined paintings and dance choreography under a common analytical framework, with exemplars from “western” (Anglo-European) and “eastern” (Indian) artistic practices. Addressing the universality of aesthetic preference, and its modulation by expertise and culture in paintings and dance should lead to a better understanding and a fresh and culturally inclusive reconceptualization of long-debated issues in empirical aesthetics such as the nature of aesthetic judgements and evaluations, and how a beholder’s attributes shape their aesthetic experience.

Theoretical accounts of aesthetic processing have proposed the influence of cultural contexts, as well as the differing meaning of beauty across cultures (e.g., 9 ). There is also some evidence to suggest cross-species universal aesthetic appreciation and perception of visual patterns such as symmetry 10 , and the universality of musical aesthetic processing (e.g., 11 ). However, our focus in the current empirical work is on cross-cultural differences (or similarities) in the visual (fine and performing) arts, specifically paintings and dance, and therefore we focus the following review of extant literature primarily on empirical cross-cultural investigations of paintings and dance.

The universality of the preference for representational art and its modulation by expertise

The creation and appreciation of art finds a place in all cultures, serving different social, religious, economic, and political functions 12 , 13 . If engagement with art is indeed universal, as has been argued, then it seems plausible that the processes underpinning aesthetic appreciation are also shared across cultures. Indeed, evidence suggests that people from different cultures base their aesthetic appreciation on a common set of features such as symmetry, contrast, colour, brightness, complexity, and proportion (for a review, see 5 ). Nevertheless, on face value, nothing seems more subjective than the human appreciation of art. People differ in their aesthetic preferences—some may like contemporary art, while others have intense negative feelings toward it 14 . Previous work also demonstrates how individual differences such as art expertise, understanding, and knowledge, as well as personality traits influence aesthetic evaluations 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 .

Aesthetic judgements and ratings of visual art have also been found to be highly idiosyncratic depending on the content depicted in the art 6 , 19 , or the contextual framing with which artworks are introduced 20 . Across a range of studies, a number of research teams report that paintings and images with representational content, i.e. those depicting landscapes, people, still life scenes, and so on, are preferred and assigned higher ratings of aesthetic qualities such as beauty and liking, compared to paintings or images with abstract content that do not represent anything concrete or figurative 6 , 8 , 17 , 21 , 22 , 23 . Preferences for representational content are also more reliable and consistent compared to abstract content. For example, Schepman and colleagues show greater agreement across people for representational compared to abstract paintings and images, and the semantic associations generated by viewers for these artworks are also more convergent across individuals for representational art compared to abstract art 6 , 23 . One proposed explanation for this preference and agreement across viewers for representational content focuses on the meaningfulness of the depiction: people may prefer art that they find meaningful, and semantic associations may be better shared for meaningful stimuli compared to abstract ones 21 .

The meaning drawn from the content of an artwork also depends on the observer’s experience, expertise, and knowledge of the artworks. Indeed, previous evidence has shown increased aesthetic ratings for abstract artworks among those with expertise and knowledge of art 24 , 25 , 26 . Therefore, although a general preference for representational artworks compared to abstract artworks seems to exist, evidence also suggests that art expertise modulates this preference such that the preference for representational (compared to abstract) artworks among art experts is more attenuated than that reported among art-naïve participants. However, the universality of this preference for visual art can be contested on the grounds that all previous research in this domain has focused exclusively on static paintings or images, and the evaluations of participants from western cultures (primarily Western Europe and North America).

It is important to note that representational and abstract artworks are not restricted to the fine arts. Dance forms across many cultures also have both representational and abstract content, such as dance that involves movements, tropes, or symbols to depict certain social or cultural themes and characters (representational dance), and dance that is purely for an aesthetic but non-symbolic, non-representative purpose (abstract dance; 27 , 28 , 29 ). Characteristics of a dance piece, such as its complexity, acceleration, predictability, uniformity, difficulty or reproducibility, movement amplitude, and evocativeness have been evidenced to predict the aesthetic ratings of dance 30 , 31 , 32 . A growing body of research has focused on the characteristics of the observer or spectator such as their visual and motor expertise with dance, and familiarity and competency with the dance movement vocabulary and how this affects aesthetic ratings 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 . Similar to paintings, the aesthetic ratings for dance are also higher for dance experts, and are modulated by similar features such as evocativeness, familiarity, and complexity. Yet, the representativeness of the content of dance and its modulation by dance expertise has to date received little attention in dance, even though, like paintings, dance can be representative or abstract 30 .

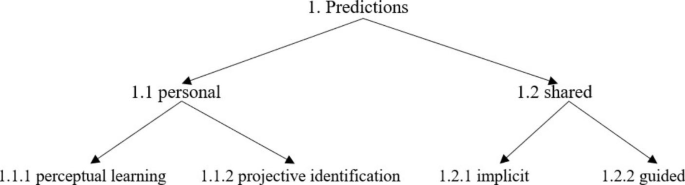

Therefore, in the current study, to address our first research question, we use mixed effects models to test whether preferences for representational art shows evidence for cultural as well as artform universality, and is modulated in a similar manner by expertise across participants from Indian and Western cultures across the domains of paintings and dance. If a universal preference for representational visual art generalises across art forms (paintings and dance), we would expect to find a preference for representational paintings and dance over abstract paintings and dance, modulated by art/dance expertise such that this preference is attenuated among painting/dance experts compared to painting/dance naïve participants. In addition, a universal preference for representational art should also emerge across cultures, and be modulated by expertise in a similar way across participants belonging to different cultures.

It is possible that a preference for representational art may be because of the familiarity or complexity of a representational artwork compared with an abstract artwork, as opposed to the abstractness of the content itself. To isolate the abstractness of the content of the paintings, we also investigated whether the universal preference for representational art and its modulation by expertise would further persist above and beyond subjective ratings of complexity, familiarity, evocativeness, reproducibility, and technical competency that have been demonstrated to influence aesthetic ratings and preferences for paintings and dance.

The universality of the ingroup bias for visual arts and its modulation by expertise

Art across the world can differ in its subject matter, production methods, the role(s) played by the artist and the spectator, and its categorisation into different art forms and styles. Cultural differences can perhaps also explain why some artworks are thought to be beautiful to some spectators and not to others. Artists from diverse cultures often report distinct aesthetic experiences when looking at the same visual art displays, and use varied geometric and metaphorical perspectives to represent the visual world in their artworks, employing specific ways to depict spatial and temporal information 7 , 38 , 39 . For instance, Western representational paintings can be very precise reproductions of the world at that time point, whereas in Indian and Chinese paintings, several periods of time can appear on the artwork at the same time 7 . Similarly, popular forms of Indian classical dance feature religious symbolism and depictions with a strong spiritual connection, whereas well-known western classical dance forms, such as ballet, do not 40 .

Previous studies investigating cultural differences in aesthetic appreciation of visual art have mainly focused on the visual processing of scenes and objects, and cultural similarities and differences in the processing of formal features such as colour perception and curvature 39 , 41 , 42 , 43 . In the domain of dance, research on cultural differences in dance appreciation is extremely sparse. One study to date has reported that Indian participants who had more visual experience or visual familiarity with Indian dance (Bharatanatyam) showed enhanced cortico-spinal excitability when viewing Bharatanatyam videos compared to Western dance (ballet) videos, whereas Western participants who have more visual experience with ballet showed higher cortico-spinal excitability when viewing ballet videos, suggesting enhanced motor resonance when watching a movement style that is more familiar 44 . However, the extent to which and how aesthetic preferences for dance might differ across cultures remains unstudied.

The few studies that have looked at the influence of cultural differences on aesthetic evaluations of artwork suggest that individuals show a preference for artworks that belong to their own culture, or correspond to their cultural traditions, compared to artworks that belong to another culture 7 , 43 . Specifically, Yang et al. 43 found that Western participants showed higher valence values when viewing Western paintings, but Chinese participants did not show this effect. Bao et al. 7 showed a double dissociation such that Chinese participants rated Chinese paintings higher on beauty compared to Western paintings, and Western participants rated Western paintings higher on beauty ratings compared to Chinese paintings. One explanation put forth for this double dissociation is a simple in-group bias 45 . Group biases (typically in-group favouritism and out-group dislike) are prevalent in day-to-day interactions wherein individuals show in-group favouritism for members of their own race, culture, ethnicity, and sex (e.g., 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 ). In a similar manner, individuals looking at artworks from their own culture may feel a sense of cultural identity and belongingness, and therefore rate it higher on aesthetic ratings compared to artworks from other cultures 7 . This preference can be implicit, i.e., when individuals are not explicitly aware that the painting belongs to their own cultural background. In contrast, the preference may only exist or be heightened when individuals have explicit knowledge of cultural closeness and can identify the painting as belonging to their own cultures.

The feeling of cultural identity, however, may not be uniform across participants with different levels of art experience, sensitivity, expertise, or knowledge. While previous research has not directly investigated the modulation of ingroup bias by the expertise of the spectator, some evidence suggests that people who are interested in art agree on their aesthetic judgements irrespective of their individual cultural backgrounds 51 , 52 . These studies, however, systematically manipulate only either the cultural background of the participants or artworks belonging to different cultures, but not both in the same experiment. Therefore, an intriguing open question remains whether a sense of cultural identity is higher in art naïve participants who may show a higher ingroup bias compared to experts who may show an attenuated ingroup bias compared to non-experts.

Therefore, to address our second research question, we use mixed effects models to test the extent to which an ingroup bias exists for both cultures such that Western participants prefer Western paintings and dance, and Indian participants prefer Indian paintings and Indian dance, compared to paintings and dance belonging to the other culture. We predict that art/dance expertise should modulate this ingroup bias similarly for both Indian and Western participants, such that experts should show no (or a reduced) preference compared to non-experts for paintings or dance belonging to their own culture compared to another culture. This ingroup bias and its modulation by expertise should further persist above and beyond the subjective ratings of complexity, familiarity, evocativeness, reproducibility, and technical competency that have been known to have an influence on aesthetic ratings and preferences of paintings and dance.

Open science statement

Across all experiments, we report how the sample size was determined, all data exclusions, and all measures used in the study 53 , 54 . For both experiments, data pre-processing, statistical analyses, and data visualisations were performed using R (R Core Team, 2018), unless otherwise specified. Following open science initiatives 55 , all raw data are available online for other researchers to pursue alternative questions of interest, along with analysis scripts and stimuli used ( https://osf.io/vtw54/ ). Data analyses for both experiments were preregistered on AsPredicted.org (Experiment 1: https://aspredicted.org/65Y_W6X , Experiment 2: https://aspredicted.org/VBB_T2F ). The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Open Science Framework (OSF) repository [ https://osf.io/vtw54/ ].

For both Experiments 1 and 2, mixed effects model analyses were executed using the ordinal package (v.2019.12–10) in R v.1.3.1093. (R Core Team). Post-hoc tests were executed using the emmeans package (v.1.5.1). We used an alpha of 0.05 to make inferences, and controlled for multiple comparisons using Tukey-HSD in post-hoc tests. Model fit was compared using the anova() function (Chi-square test).

Experiment 1—Paintings

Sample size justification.

We determined the sample size based on a simulation-based power analysis approach using the simr R package 56 . First, we used pilot data (N = 22, 14 females, 10 art experts, Mean age = 29.71, SD age = 9.86) for beta weight estimation for the following linear mixed effects model: beauty ~ category*expertise + (1|subject) + (1|item). Second, we simulated data by extending along the sample size, i.e., as a function of different sample sizes. Our main focus was the interaction between the category of the painting and the art expertise of participants, and the power analysis suggested that we required a sample size of 50 participants (25 experts and 25 non-experts) with 35 items to have > 80% power to detect a significant category*expertise interaction (more details on the power analyses and the code can be found on OSF and in the supplementary material, see Figure S1 ). We therefore aimed to stop data collection when over 100 participants finished the entire survey, with an aim to recruit approximately 50 Indian participants and 50 Western participants with 25 experts and 25 non-experts within each culture.

Participants

Participants were recruited using the online data collection tool PsyToolkit 57 , 58 . Participants were primarily recruited from India and UK/Europe and classified into either Indian or Western culture participants (see Supplementary Table 2 for a geographic distribution of the sample) by advertisement on social media. All participants provided informed consent, and had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Glasgow ethics review board (300190209), and all experiments were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were reimbursed with an Amazon gift card of either 6 GBP or Rs. 550 INR.

A total of 145 participants started the online experiment, with 113 participants completing the full experiment. Participants were excluded if they did not pass our attention check questions (see section “ Tasks and Procedures ”; N = 19), or did not provide required demographic information (age, gender, and culture; N = 2). The final sample consisted of 92 participants (17 males, 75 females; Mean age = 25.52, SD age = 3.96) which included 45 Indian participants (21 experts, 24 non-experts) and 47 Western participants (21 experts, 26 non-experts). All participants provided informed consent, and had normal or corrected-to-normal vision (a geographic distribution of the participant sample is provided in Table S2 ).

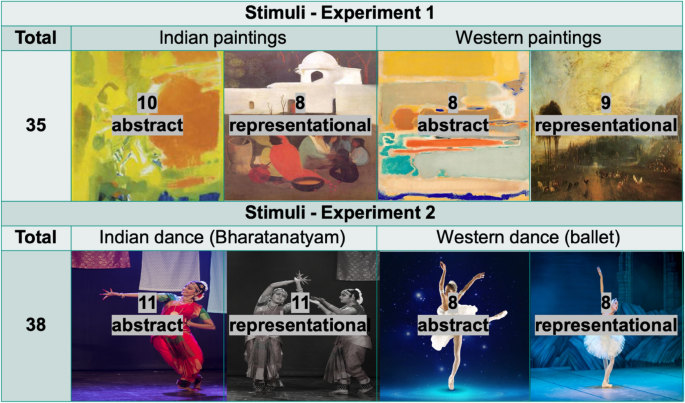

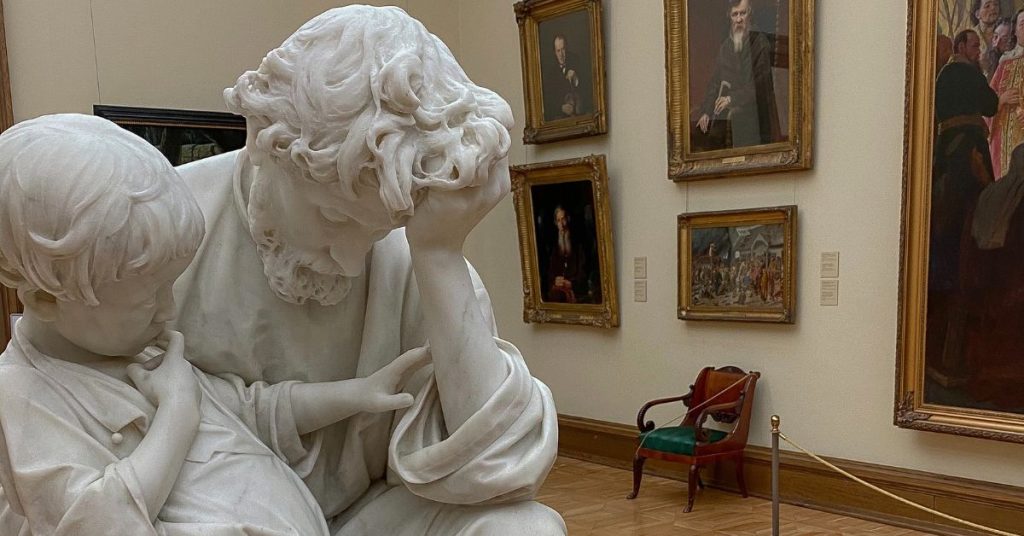

An independent sample of art naïve participants (N = 21, 13 females, Mean age = 29.14, SD age = 6.73) rated the first pool of images for abstract and representational paintings on familiarity, complexity, and evocativeness, and categorized them into ‘abstract’ or ‘representational’. A total of 120 paintings were selected and resized to 500 × 500 pixels: 60 by Indian painters, 60 by Western painters, out of which 30 each were abstract and representational paintings. Paintings were categorized by the experimenters as either ‘abstract’ or ‘representational’ depending on the content of the painting. That is, paintings depicting representational or figurative content (such as still life or landscapes) were categorized as ‘representational’ and paintings depicting content that was abstract (or not representative of anything concrete or figurative) were classified as ‘abstract.’ Participants also categorized the paintings into whether they thought the painting was abstract or representational. The final stimulus set consisted of paintings with ratings most similar to each other on the three variables of familiarity, complexity, and evocativeness. These paintings were also accurately classified as either ‘abstract’ or ‘representational’ i.e. the categorization by the participants matched the categorization made by the experimenters (more details along with the analysis code can be found here: https://osf.io/vtw54/ ). The final stimulus set consisted of 35 paintings—10 Indian abstract, 8 Western abstract, 8 Indian representational, and 9 Western representational paintings (see Fig. 1 ; note that the number of stimuli is unbalanced across categories because of the type of analysis we used to balance paintings on the variables of familiarity, complexity, and evocativeness. See the Supplementary material for more information). The paintings were resized to 500 × 500 pixels, and matched for mean luminance using the SHINE toolbox in MATLAB 59 . Therefore, the final stimulus set was closely matched across all four categories of paintings (Indian Abstract, Indian Representational, Western Abstract, Western Representational) on variables of luminance, familiarity, complexity, and evocativeness (for mean ratings for each painting category, please refer to Table S1 ).

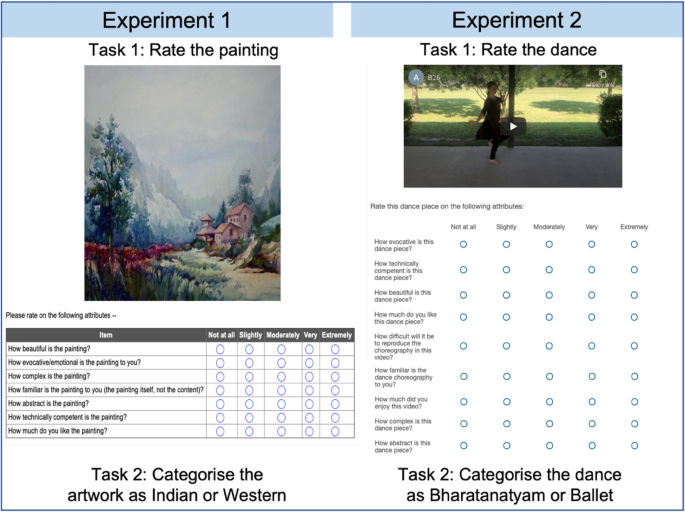

Categories of paintings and dance (abstract/representational) across different sources of painting or dance style (Indian/Western). Note: All images used in Figs. 1 and 2 are in the public domain, and/or we have informed consent from individuals for publication of their image in an online open access publication. Images used to depict abstract and representational paintings and dance in Figure 1 are not images of the actual stimuli used. Stimuli used in the current study are available online on the OSF.

Tasks and procedure

Participants completed two tasks—a rating task and a categorization task (see Fig. 2 ). In the rating task, participants saw a painting on the screen, and were asked to rate it on a 5-point likert scale from low (1) to high (5) with ‘1’ corresponding to ‘not at all’, ‘2’ corresponding to ‘slightly’, ‘3’ corresponding to ‘moderately’, ‘4’ corresponding to ‘very’, and ‘5’ corresponding to ‘extremely’ on the following variables:

Familiarity (how familiar is the painting?)

Complexity (how complex is the painting?)

Evocativeness (how evocative or emotional is the painting?)

Abstractness (how abstract is the painting?)

Technical competency (how technically competent is the painting or the painter who made the painting?)

Beauty (how beautiful do you find the painting?)

Liking (how much do you like the painting?)

Graphical representation of the rating task and categorisation task for Experiments 1 and 2.

The order in which these questions were presented was randomized for each item, and the order in which the items (35 paintings) were presented was also randomized across participants. Two additional questions appeared randomly during the rating task which served as attention check questions: “how attentive are you while doing this experiment?” and “how honest are you while doing this experiment?” The 5-point likert scale remained the same as for the other variables. Participants who responded < 4 on the 5-point likert scale were excluded from the analyses.

In the categorisation task, participants categorized the same 35 paintings they saw during the rating task into either ‘Indian’ or ‘Western’ depending on whether they thought the painting was produced by a painter of Indian origin or a painter of Western origin. The order of the items (35 paintings) was randomized across participants. Participants also completed two questionnaires—the Art Experience Questionnaire 60 to gauge their art expertise, and (unrelated to the current study) the Vienna Art Interest and Art Knowledge (VAIAK) questionnaire 61 . They were also asked if they were art professionals or not—participants were categorized as ‘non-experts’ if they were art naïve or had no experience or qualifications related to the arts, and participants were categorized as art ‘experts’ if they worked as art professionals or had completed their Masters in an arts-related field (fine arts, or arts history; detailed data of arts expertise in participants based on academic and professional qualifications, as well as their scores on the Art Experience Questionnaire, can be found on OSF). The experiment started with some demographic questions, the Art Experience Questionnaire, and then participants completed the rating task, the categorisation task, and the VAIAK questionnaire. The order of tasks and questionnaires remained constant across participants, and the tasks were self-paced. The entire experiment did not last for more than 60 min for most participants (Mean timetaken = 50.86 min, SD timetaken = 39.25). The script used for online experiment presentation in Psytoolkit is provided on the OSF.

Data analysis

We recorded ratings for each item for each participant on all variables for the rating task. For the categorisation task, we recorded which items were classified as either Indian or Western by participants (source of painting as rated by participants). We also calculated accuracy by calculating the percentage of items that were correctly categorized as Indian or Western i.e. when the actual source of the painting matched the participant’s response.

RQ1: Do expertise and culture influence aesthetic judgements of representational and abstract art (preregistered and confirmatory)?

Beauty and liking ratings were analysed separately. The current analyses differ from our pre-registered analyses in three ways:

Our study was powered to detect a category*expertise interaction with N = 50. We aimed to collect N = 50 for both cultures, and include the category*expertise*culture interaction as a fixed effect in the current model. We were able to collect N = 45 Indian and N = 47 Western participants i.e. a total N of 92 participants. Therefore, while we are powered to detect the category*expertise interaction in the total sample, we are not sufficiently powered to detect the three-way interaction of culture*expertise*category. Therefore, any findings we report are suggestive and exploratory, and not confirmatory.

We pre-registered a linear mixed effects analysis using the ‘lme4’ package in R 62 . However, because the data were ordinal in nature, we decided to analyse the ordinal data using cumulative link mixed models by using the ‘ordinal’ package in R 63 . Analysing the data using ‘lme4’ yielded similar results.

In the preregistered analyses, we included category (abstract, representational) and art expertise (expert, nonexpert) as categorical fixed effects of interest, and the by-subject and by-item intercept as a random factor for the model. However, given recommendations for the “keep it maximal” approach to multilevel modeling 64 , we further included the maximal number of random effects that the design permitted.

The categorical variables were coded using a deviation coding style where factors sum to zero and the intercept can then be interpreted as the grand mean and the main effects can be interpreted similarly to a conventional ANOVA 65 . As such, the categorical variables of category, expertise, culture, and source of painting were coded as 0.5 (representational/expert/Indian/Indian) and − 0.5 (abstract/nonexpert/Western/Western). An ordinal logistic regression was employed in the form of a cumulative-link mixed model (ordinal package, “clmm” function; 63) using logit (log-odds) as link, and flexible thresholds between the ordinal scores. We chose this approach because the dependent or outcome variables ‘beauty’ and ‘liking’ ratings were ordinal in nature (ratings on a Likert scale 1–5). The model thus measures the probability of specific ratings being above certain thresholds without the assumption that the thresholds are symmetric or equidistant from each other. In order to address our first question of interest i.e. whether representational and abstract art judgements are modulated by art expertise, and whether this is similar for both cultures, we included the three way interaction of category (abstract, representational), expertise (expert, nonexpert), and culture (Indian, Western) as a fixed effect in the model. For random effects, we included the maximal number of random effects that the design permitted. The complexity of the random structure was reduced if the results showed failure in model convergence or a singular fit. The final model used was –

To test whether category, expertise, and culture modulated beauty and liking ratings above and beyond the subjective factors that participants rated the paintings on (familiarity, complexity, evocativeness, technical competency), we further added the subjective variables as fixed effects to the model.

RQ2: Does expertise shape the ingroup bias for aesthetic judgements (preregistered but exploratory)?

We preregistered the hypotheses for our second research question, but we note that the present study was not powered to detect a three-way interaction of culture, source of painting, and expertise. Therefore, any conclusions we draw from these analyses are exploratory and suggestive, and not confirmatory.

In order to investigate the ingroup bias in aesthetic judgements, we tested for an interaction between culture of participants and the source of painting, and how this was modulated by expertise. Beauty and liking ratings were analysed separately. The categorical variables were coded using a deviation coding style. As such, expertise, culture, and source of painting were coded as 0.5 (Indian/expert/Indian) and − 0.5 (Western/nonexpert/Western). In order to address our second question of interest i.e. whether the ingroup bias exists, and is modulated by art expertise, we included the three way interaction of source of painting (Indian, Western), expertise (expert, nonexpert), and culture (Indian, Western) as a fixed effect in the model. For random effects, we included the maximal number of random effects that the design permitted. The complexity of the random structure was reduced if the results showed failure in model convergence or a singular fit. The final model used was –

To test whether source of painting, expertise, and culture modulated beauty and liking ratings above and beyond the subjective factors that participants rated the paintings on (familiarity, complexity, evocativeness, technical competency), we further added the subjective variables as fixed effects to the model.

In the analyses above, the factor ‘source of painting’ was coded according to whether a painting was actually painted by an ‘Indian’ artist or a ‘Western’ artist. However, participants were not explicitly made aware while doing the rating task that the paintings were Indian or Western. If an ingroup bias does exist in this case, the preference for paintings from their own cultural background might be reported irrespective of whether participants can accurately identify the painting as Indian or Western in an explicit sense. In contrast, preferences for artworks from one’s own culture may only arise or may be heightened when participants themselves classify the painting as ‘Indian’ or ‘Western’ and have an explicit knowledge of cultural closeness, irrespective of whether or not the paintings were actually made by an ‘Indian’ painter or ‘Western’ painter. In order to test this, we repeated the mixed effects model analyses with the factor ‘source of painting—ppt’ coded as ‘Indian’ or ‘Western’ as categorized by the participants in the categorisation task.

Experiment 2—Dance

We determined the sample size based on a simulation-based power analysis approach using the simr R package 56 . First, we used pilot data (N = 21, 17 females, 12 dance experts, Mean age = 29.71, SD age = 9.86) for beta weight estimation for the following model: beauty ~ category*expertise + (1|subject) + (1|item). Second, we simulated data by extending along the sample size and plotted statistical power as a function of different sample sizes (see Figure S9 ; more details on the power analyses and the code can be found here: https://osf.io/vtw54/ ). Our main focus was the interaction between the category of the dance and the dance expertise of participants, and the power analysis suggested that we required a sample size of 50 participants (25 experts and 25 non-experts) with 38 items to have 80% power to detect a significant category*expertise interaction. We therefore aimed to recruit 50 Indian participants and 50 Western participants with approximately 25 experts and 25 non-experts in each culture.

Participants completed the experiment on Qualtrics. Participants were primarily recruited from India and UK/Europe and classified as either from Indian or Western culture (see the supplementary table S10 for a geographic distribution of the sample). All participants provided informed consent, and had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Glasgow ethics review board (300190209), and all experiments were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were reimbursed with an Amazon gift card of either 6 GBP or Rs. 550 INR.

A total of 161 participants started the online experiment, with 110 participants completing the full experiment. Participants were excluded if they did not pass our attention check questions (see “section Tasks and procedure ”; N = 16), and did not provide required demographic information (age, gender, and culture; N = 2). Two participants were further excluded as they did not fit in either the ‘Indian’ or ‘Western’ culture group of participants (a geographic description of our participant sample is provided in the Table S10 ). The final sample consisted of 90 participants (79 females, 8 males, 3 non-binary; Mean age = 25.94, SD age = 7.51) which included 48 Indian participants (23 experts, 25 non-experts) and 42 Western participants (22 experts, 20 non-experts). All participants provided informed consent, and had normal or corrected-to-normal vision.

We invited a professional dancer trained in classical ballet and Bharatanatyam, Sophia Salingaros 66 , to record Bharatanatyam and ballet dance videos. We recorded both ballet and Bharatanatyam dance videos featuring movement sequences that either were intended to represent something in the external world (e.g. humans, animals, birds, nature, etc.) or not represent anything in particular (pure dance, referred to as nrtta in Bharatanatyam, or non-representational abstract dance). The videos were edited in iMovie into 10–12 s clips, and the first 0.5 s of the video faded in, and the last 0.5 s faded out to a black screen. An independent sample of participants (all non-dancers, N = 13, 8 females, Mean age = 28.85, SD age = 8.93) rated the first pool of stimuli of abstract and representational dance videos on familiarity, complexity, and evocativeness. Out of a total of 91 videos (46 Bharatanatyam/Indian dance videos, out of which 18 were abstract, and 45 ballet/Western dance videos, out of which 25 were abstract), the final stimulus set was selected by selecting dance videos with ratings most similar to each other on the three variables of familiarity, complexity, and evocativeness (more details along with the analysis code can be found on the OSF). The final stimuli consisted of 38 dance videos—11 Indian abstract, 8 Western abstract, 11 Indian representational, and 8 Western representational dances, matched on the variables of familiarity, complexity, and evocativeness (see Supplementary Material for more details). Mean ratings for each video as rated in the pilot study are reported in Table S9 , and all videos are available on the OSF.

Participants completed two tasks—a Rating task and a Categorization task (see Fig. 2 ). In the rating task, participants saw a dance video on the screen, and were asked to rate it on a 5 point likert scale similar to Experiment 1 from low (1) to high (5) on the following variables:

Familiarity (how familiar is the dance?)

Complexity (how complex is the dance?)

Evocativeness (how evocative or emotional is the dance?)

Abstractness (how abstract is the dance?)

Technical competency (how technically competent is the dance?)

Reproducibility (how reproducible is the dance?)

Beauty (how beautiful do you find the dance?)

Liking (how much do you like the dance?)

Enjoyability (how much did you enjoy the dance?)

The order in which these questions were presented was randomized for each item, and the order in which the items (38 dance videos) were presented was also randomized across participants. Two additional attention check questions were also presented randomly during the task (same as Experiment 1) and participants who responded < 4 on the likert scale on these questions were excluded from the analyses.

In the categorisation task, participants categorized the same 38 dance videos they saw during the rating task into either ‘Bharatanatyam’ or ‘Ballet’ depending on whether they thought the dance was of Indian origin or Western origin (the instructions given to the participants were whether they thought the dance was ballet i.e., western classical dance/ of Western origin, or Bharatanatyam i.e., Indian classical dance/ of Indian origin). The order of the items (38 dance videos) was randomized across participants. Participants also completed a dance experience questionnaire similar to the Art Experience Questionnaire ( 60 , see the supplementary material for the exact set of questions used to measure dance experience). Participants were asked if they were dance professionals or not—participants were categorized as ‘non-experts’ if they were dance naïve or had no experience with or qualifications related to dance, and participants were categorized as dance ‘experts’ if they worked as dance professionals or had more than 8 years of training in either ballet or Bharatanatyam (a detailed distribution of dance expertise in participants and their scores on the dance experience questionnaire can be found in the supplementary material). The experiment started with some demographic questions, followed by the rating task and the categorisation task. The tasks and questionnaires were self-paced, and the order remained constant across participants. The experiment was self-paced but lasted ~ 120 min for most participants (Mean time = 120.19 min, SD time = 242.40). Results were similar when participants who were 3SD away from the mean time taken by participants to finish the experiment were excluded from the analyses.

The data analysis pipeline was the same as Experiment 1 with the following changes: 1) instead of categorizing paintings as Indian and Western, participants categorized dance as either Ballet or Bharatanatyam (labelled as ‘dance style’ instead of ‘source of painting’; 2) we added two additional variables: enjoyability as a dependent variable, and reproducibility as a subjective variable. Therefore, the model with subjective variables for Experiment 2 includes reproducibility along with other variables (the same as Experiment 1), and analyses are performed separately for beauty, liking, and enjoyability dependent/outcome variables.

Rating task

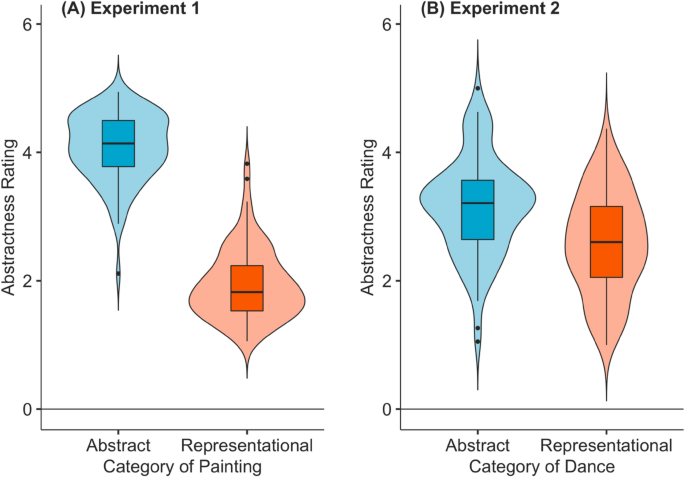

Mean ratings for familiarity, complexity, evocativeness, technical competency, beauty, liking, and abstractness across abstract and representational art for experts and non-experts of Indian and Western cultures and Indian and Western art are provided in Table S3 and in Figures S2 - S8 . To check whether participants perceived abstract and representational paintings as more abstract and less abstract respectively, participants were also asked to rate paintings on abstractness. Overall, a paired samples t-test suggested that participants rated abstract paintings (Mean = 4.08, SD = 0.52) higher on abstractness compared to representational paintings (mean = 1.94; SD = 0.55; t(91) = 29.44, p < 0.001, 95% CI [2.01, ∞]; see Fig. 3 ).

Abstractness ratings (on a 5-point likert scale where 1 = not at all abstract, and 5 = extremely abstract) for abstract and representational paintings (A; Experiment 1) and abstract and representational dance (B; Experiment 2).

Categorisation task

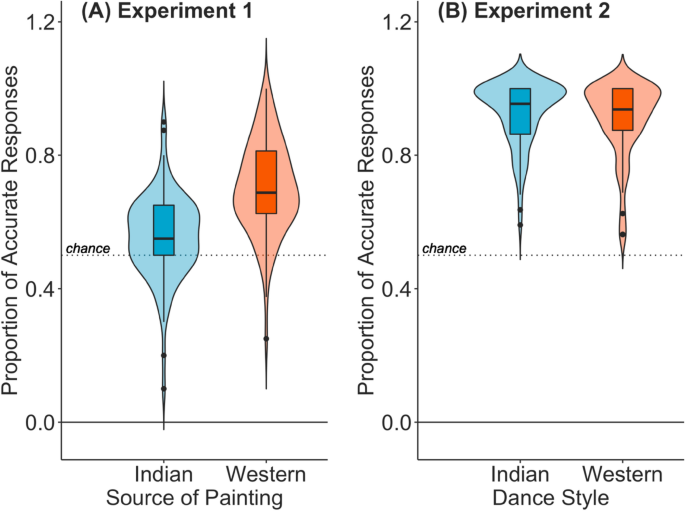

Accuracy on the categorisation task across category, source of painting, expertise, and culture are provided in Table S17 . One sample t-tests suggested that for both Indian and Western paintings, participants could accurately categorise paintings as “Indian” or “Western” greater than chance (Indian paintings: Mean = 0.55, SD = 0.20, t(91) = 4.18, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.53, ∞]; Western paintings: Mean = 0.70, SD = 0.24, t(91) = 14.06, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.68, ∞]; see Fig. 4 A). Accuracy for Western paintings was higher than Indian paintings (t (91) = 7.35, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.19, 0.11]).

Proportion of accurate responses for Experiment 1 ( A ) and Experiment 2 ( B ) of all participants for Indian and Western paintings and dance styles. Dashed line represents 50% accuracy (or chance).

RQ1: Do expertise and culture shape aesthetic judgements of representational and abstract art (preregistered and confirmatory)?

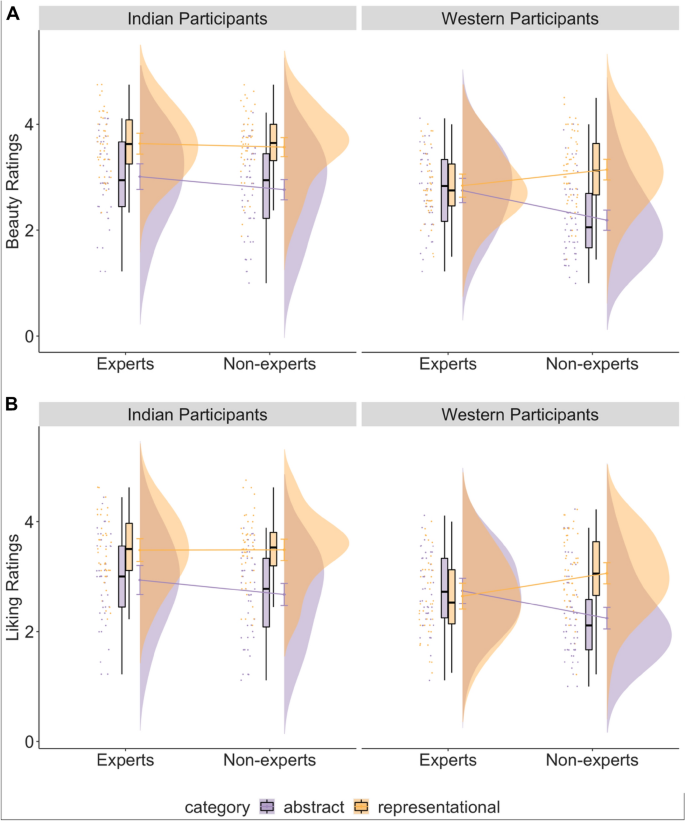

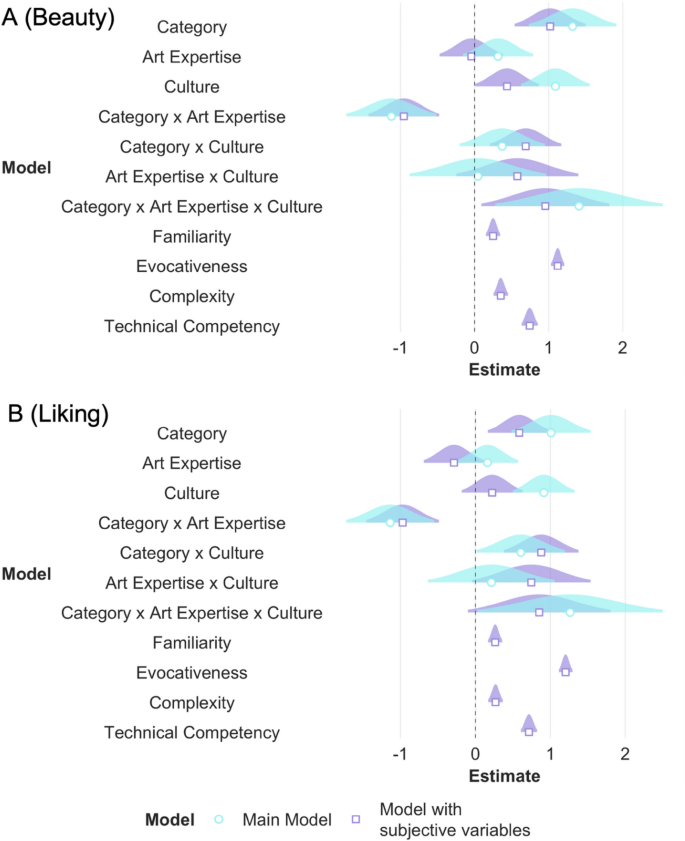

The results of a cumulative link mixed effects model for beauty and liking ratings showed that category (beauty: β = 1.32, p < 0.001; liking: β = 1.01, p < 0.001), culture (beauty: β = 1.09, p < 0.001; liking: β = 0.91, p < 0.001) the interaction between category and expertise (beauty: β = 1.12, p < 0.001; liking: β = 1.14, p < 0.001), the interaction between culture and category (liking: β = 0.60, p = 0.04) and the three-way interaction between category, expertise, and culture (beauty: β = 1.41, p < 0.001; liking: β = 1.26, p = 0.04) had an effect on the ratings of beauty and liking (Table S4 ). Post-hoc tests revealed that all participants (except Western experts) showed higher ratings of beauty and liking for representational paintings compared with abstract paintings, and overall ratings by Indian participants were higher than Western participants (see Table S8 ). Specifically, to test our hypothesis whether the difference in beauty and liking ratings of abstract and representational paintings would be higher in non-experts compared to experts, we computed an interaction contrast for both Indian and Western culture participants separately. The contrast revealed that the difference between beauty and liking ratings for abstract and representational paintings was higher in non-experts than experts, but only for Western participants (beauty: M = 1.83, SE = 0.42, p < 0.001; liking: M = 1.77, SE = 0.44, p < 0.001) and not for Indian participants (beauty: M = 0.42, SE = 0.43, p = 0.33, Fig. 5 A; liking: M = 0.51, SE = 0.43, p = 0.24, Fig. 5 B).

The effect of category (abstract or representational paintings), expertise (art experts or non-experts) and culture (Indian participants or Western participants) on the ratings of beauty ( A ) and liking ( B ).

As our study was powered to detect a two-way interaction between category and expertise, we additionally ran a model to test for this interaction for Indian and Western culture participants separately:

Similar to the above findings, we found that beauty and liking ratings were modulated by an interaction between category and expertise only for Western participants (beauty: β = 1.76, p < 0.001; liking: β = 1.66, p < 0.001), and not for Indian participants (β = 0.44, p = 0.32; liking: β = 0.53, p = 0.25; see Table S7 ).

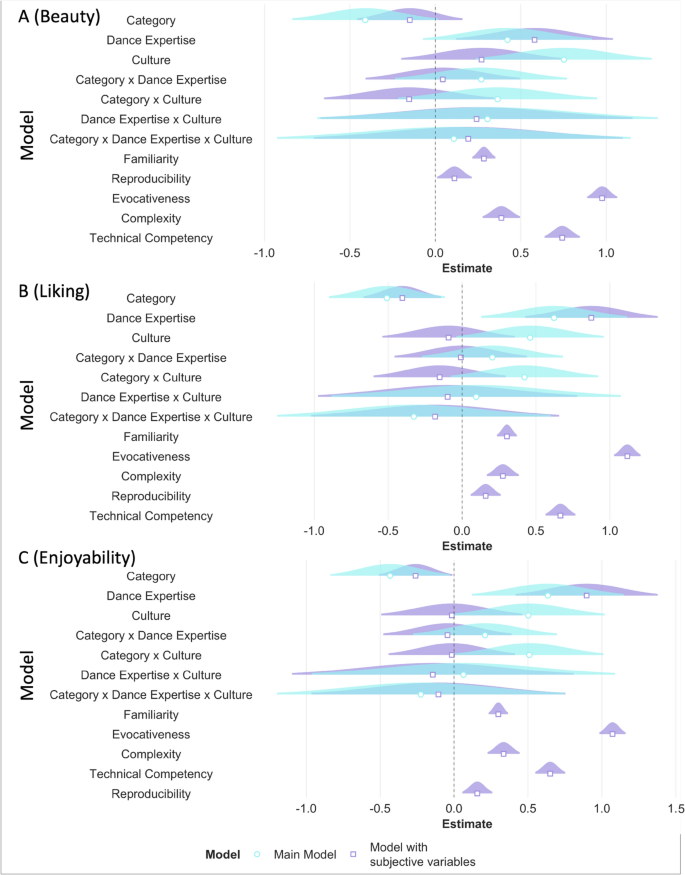

Additionally, we added the subjective variables of familiarity, evocativeness, complexity, and technical competency as fixed effects to our main model to investigate whether the three-way interaction modulated beauty and liking ratings irrespective of the contribution of the subjective variables. As expected, all subjective variables predicted ratings of beauty and liking, with higher familiarity, complexity, evocativeness, and technical competency predicting higher ratings of beauty and liking. Adding the subjective variables significantly improved our main models (beauty: AIC main = 8492.53, AIC subj = 7035.66, p < 0.001; liking: AIC main = 8893.61, AIC subj = 7391.98, p < 0.001) and the three-way interaction of category, expertise, and culture influenced ratings of beauty even when accounting for possible contributions of subjective variables. For liking ratings, the three-way interaction estimate confidence intervals partially overlapped with zero but still influenced ratings of liking even when accounting for possible contributions of subjective variables (see Table S4 ; Fig. 6 A,B).

For the outcome variables of beauty ( A ) and liking ( B ), beta estimates for the main model (in aqua blue) and the model with subjective variables (in purple) are plotted for each predictor variable along with their corresponding uncertainties (95% confidence interval width for a normal distribution for each estimate). Distributions are rescaled to match the height of each distribution. This figure (and other similar figures) is made using the plot_summs function in the jtools R package (v. 2.1.0; Long, 2020).

RQ2: Does expertise influence the ingroup bias for aesthetic judgements (preregistered but exploratory)?

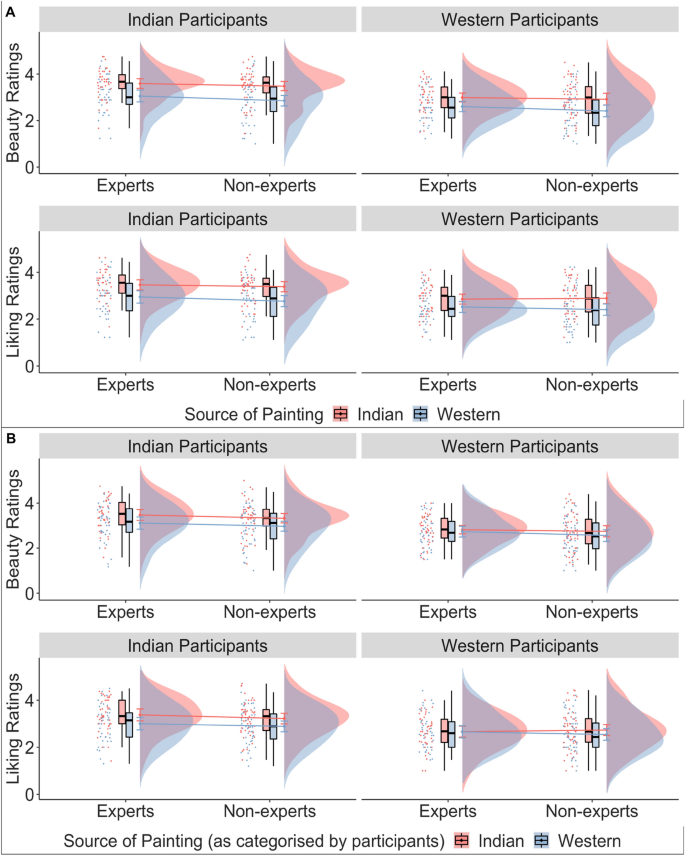

The results of a cumulative link mixed effects model for beauty and liking ratings showed that source of painting (beauty: β = 1.05, p < 0.001; liking: β = 1.01, p < 0.001) and culture (beauty: β = 1.05, p < 0.001; liking: β = 0.91, p < 0.001) had an effect on the ratings of beauty and liking (Table S5 ). Specifically Indian paintings were liked more and rated as more beautiful than Western paintings by all participants. Indian participants (beauty: M = 0.43, SE = 0.23, 95% CI [− 0.03, 0.88]) showed higher ratings of beauty and liking for all paintings compared to Western participants (beauty: M = − 0.62, SE = 0.24, 95% CI [− 1.08, − 0.16]; p < 0.001). There was no evidence of an ingroup bias or its modulation by art expertise: there were no other significant main effects or two-way or three-way interactions (see Table S5 , Fig. 7 A,B).

The effect of source of painting (A) and the source of painting as categorized by participants (B; Indian or Western paintings depicted in red and blue respectively), expertise (art experts or non-experts) and culture (Indian participants or Western participants) on the ratings of beauty and liking.

Similar to RQ1, we ran an additional model adding the subjective variables of familiarity, evocativeness, complexity, and technical competency as fixed effects. As expected, all subjective variables influenced the ratings of beauty and liking. Adding the subjective variables significantly improved our main models (beauty: AIC main = 8636.42, AIC subj = 7087.03, p < 0.001; liking: AIC main = 8893.61, AIC subj = 7391.98, p < 0.001). The main effects of culture (although marginally significant) and source of painting still influenced beauty and liking ratings even when accounting for the possible contributions of the subjective variables (see Table S5 , Fig. 8 A,B).

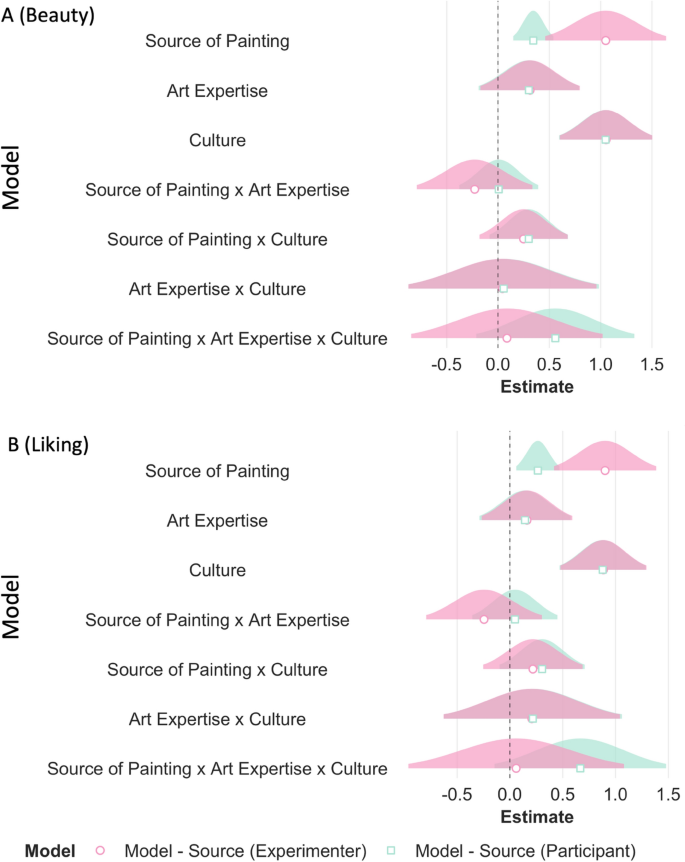

For the outcome variables of beauty and liking, beta estimates for the main model (in aqua blue) and the model with subjective variables (in purple) are plotted for each predictor variable along with their corresponding uncertainties (95% confidence interval width for a normal distribution for each estimate). Distributions are rescaled to match the height of each distribution. Figures A1 and A2 display models with source of painting as classified by the experimenter i.e., according to the origin of the artists. Figures B1 and B2 display models with source of painting as classified by the participants themselves.

Results were similar when the factor ‘source of painting’ was coded as either ‘Indian’ or ‘Western’ as categorized by the individual participants in the Categorization task (see Table S6 , Figs. 9 and 10 ). That is, source of painting and culture influenced beauty and liking ratings, but no other two-way or three-way interactions were found. However, a visual inspection of the data suggests that although a three-way interaction did not pass our statistical threshold (i.e. p < 0.05), a trend for a three way interaction can be observed such that Western experts no longer showed higher ratings of beauty and liking for Indian paintings when paintings were categorized by the participants (see Figs. 7 A,B, 9 A,B).

For the outcome variables of beauty ( A ) and liking ( B ), beta estimates for the model with source of painting as categorized by the experimenter (in pink) and the model with source of paintings as categorized by the participant (in green) are plotted for each predictor variable along with their corresponding uncertainties (95% confidence interval width for a normal distribution for each estimate). Distributions are rescaled to match the height of each distribution.

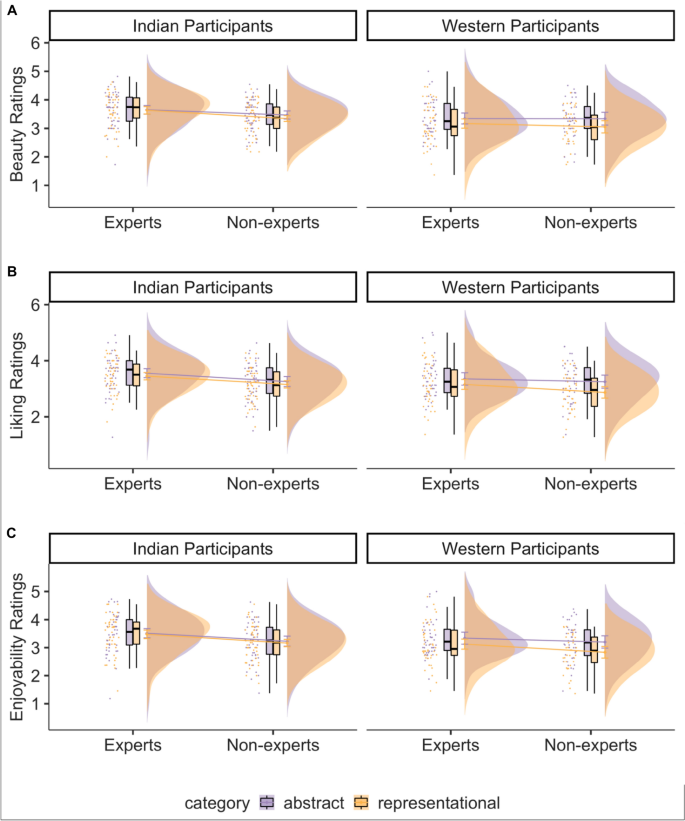

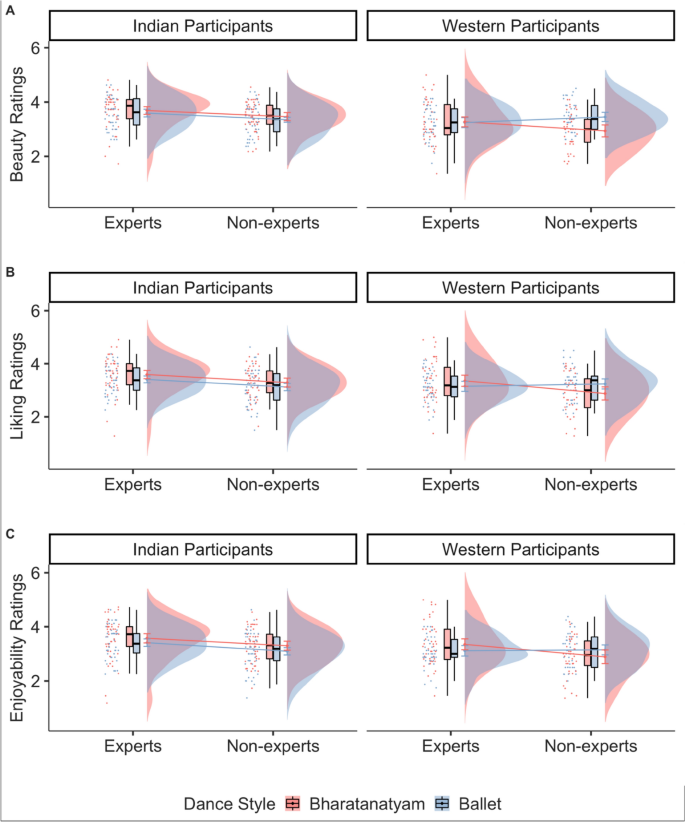

The effect of dance expertise (experts or non-experts) and culture (Indian or Western participants) on beauty, liking, and enjoyability ratings of abstract (in purple) and representational (in yellow) dance videos.

Mean ratings for familiarity, complexity, evocativeness, technical competency, reproducibility, and abstractness across abstract and representational dance for experts and non-experts of Indian and Western cultures for Bharatanatyam and ballet dance styles are provided in Table S11 and in Figures S10 - S17 . To check whether participants perceived abstract and representational dance as more abstract and less abstract respectively, participants were also asked to rate the dance videos on abstractness. Overall, a paired-samples t-test suggested that participants rated abstract dance videos (Mean = 3.16, SD = 0.76) higher on abstractness compared to representational dance (mean = 2.59; SD = 0.79; t(89) = 4.81, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.37, ∞]; see Fig. 3 B).

Accuracy across dance style, category, expertise, and culture are provided in Table S18 . One sample t-tests suggested that for both Indian and Western dance styles, participants could accurately categorise dance videos as “Bharatanatyam” or “ballet” greater than chance (Bharatanatyam: Mean = 0.93, SD = 0.14, t(89) = 43.08, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.91, ∞]; ballet: Mean = 0.91, SD = 0.16, t(89) = 35.24, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.89, ∞]; see Fig. 4 B). There was no difference in accuracy for Bharatanatyam or ballet dance styles (t (89) = 1.13, p = 0.26, 95% CI [− 0.01, 0.05]).

RQ1: Do expertise and culture shape aesthetic judgements of representational and abstract dance (preregistered and confirmatory)?

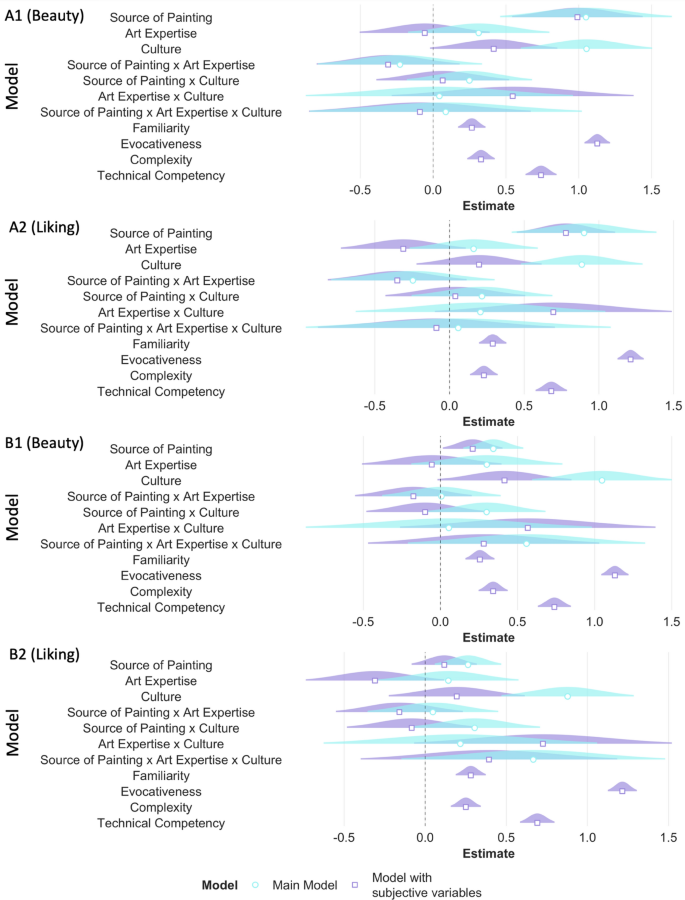

The results of a cumulative link mixed effects model for beauty, liking, and enjoyability ratings showed that culture (beauty: β = 0.75, p = 0.004; liking: β = 0.46, p = 0.07; enjoyability: β = 0.50, p = 0.06), category (beauty: β = 0.41, p = 0.06; liking: β = 0.51, p = 0.01; enjoyability: β = 0.43, p = 0.03) and dance expertise (beauty: β = 0.42, p = 0.09; liking: β = 0.62, p = 0.01; enjoyability: β = 0.63, p = 0.01) had an impact on the ratings of beauty, liking, and enjoyability. Ratings by Indian participants (beauty: M = 1.22, SE = 0.19, 95% CI [0.84, 1.59]; liking: M = 0.745, SE = 0.19, 95% CI [0.37, 1.10]; enjoyability: M = 0.75, SE = 0.20, 95% CI [0.36, 1.14]) were overall higher than ratings made by Western participants (beauty: M = 0.46, SE = 0.21, 95% CI [0.04, 0.88], p = 0.004; liking: M = 0.28, SE = 0.20, 95% CI [− 0.12, 0.68]; enjoyability: M = 0.25, SE = 0.21, 95% CI [− 0.16, 0.66]). Abstract dance videos (beauty: M = 1.04, SE = 1.87, 95% CI [0.68, 1.41]; liking: M = 0.76, SE = 0.18, 95% CI [0.41, 1.11]; enjoyability: M = 0.72, SE = 0.18, 95% CI [0.36, 1.08]) were rated as more beautiful, more enjoyable, and were liked more than representational dance videos (beauty: M = 0.63, SE = 0.19, 95% CI [0.26, 1.01], p = 0.06; liking: M = 0.25, SE = 0.18, 95% CI [− 0.10, 0.61]; enjoyability: M = 0.28, SE = 0.19, 95% CI [− 0.08, 0.65]). Dance experts (beauty: M = 1.05, SE = 0.19, 95% CI [0.68, 1.43]; liking: M = 0.82, SE = 0.19, 95% CI [0.45, 1.18]; enjoyability: M = 0.82, SE = 0.20, 95% CI [0.43, 1.20]) rated all dance videos higher on beauty, liking, and enjoyability than non-dancers (beauty: M = 0.63, SE = 0.21, 95% CI [0.22, 1.04], p = 0.09; liking: M = 0.20, SE = 0.20, 95% CI [− 0.20, 0.59]; enjoyability: M = 0.18, SE = 0.21, 95% CI [− 0.23, 0.59]). No other two-way or three-way interactions emerged for beauty and liking ratings (see Table S12 and Fig. 10 A–C). A two-way interaction between category and culture influenced enjoyability ratings (enjoyability: β = 0.51, p = 0.05). Post hoc tests revealed that abstract dance videos (M = 0.59, SE = 0.23, 95% CI [0.13, 1.05]) were rated as more enjoyable compared to representational dance videos (M = − 0.09, SE = 0.24, 95% CI [− 0.57, 0.38], p = 0.005) only by Western participants and not by Indian participants.

For Indian participants, dance expertise had a marginal effect on ratings of beauty, liking, and enjoyability, with expert dancers showing higher ratings than non-dancers (beauty: β = 0.59, p = 0.08; liking: β = 0.68, p = 0.04; enjoyability: β = 0.67, p = 0.07), and for Western participants, abstract dance videos were rated as more beautiful, were liked more, and were rated as more enjoyable than representational dance videos (beauty: β = 0.58, p = 0.04; liking: β = 1.01, p = 0.005; enjoyability: β = 0.69, p = 0.054; see Table S15 ). No two-way interaction between category and art expertise emerged.

Additionally, we added the subjective variables of familiarity, evocativeness, complexity, reproducibility, and technical competency as fixed effects to our full model to investigate whether the main effects of category, expertise, and culture modulated beauty, liking, and enjoyability ratings irrespective of the contribution of the subjective variables. As expected, all subjective variables predicted ratings of beauty, liking, and enjoyability with higher familiarity, complexity, evocativeness, reproducibility, and technical competency predicting higher ratings of beauty, liking, and enjoyability. Adding the subjective variables significantly improved our main models (beauty: AIC main = 8469.90, AIC subj = 7001.71, p < 0.001; liking: AIC main = 8862.6, AIC subj = 7307.13, p < 0.001; enjoyability: AIC main = 8889.0, AIC subj = 7366.1, p < 0.001). Dance expertise influenced beauty, liking and enjoyability ratings, and category influenced liking and enjoyability ratings, even when accounting for possible contributions of subjective variables. In this particular analysis, we did not find that culture particularly influenced beauty, liking, and enjoyability ratings suggesting that the effects of subjective variables could perhaps explain the effect of culture seen in the main models (see Table S12 , Fig. 11 A–C).

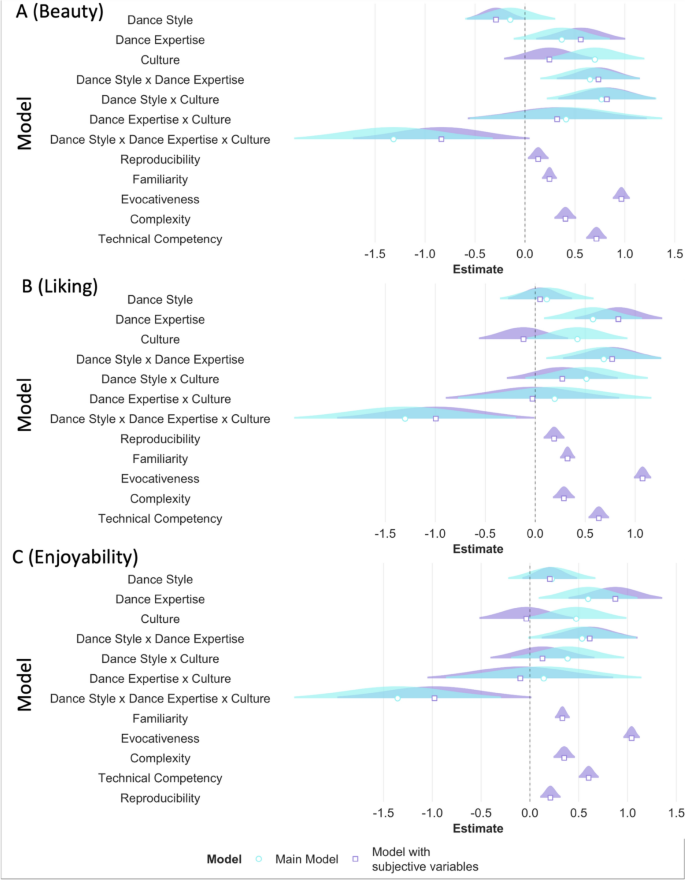

RQ1: The effect of category, expertise, and culture. For the outcome variables of beauty ( A ), liking ( B ), and enjoyability ( C ) beta estimates for the main model (in aqua blue) and the model with subjective variables (in purple) are plotted for each predictor variable (fixed effect) along with their corresponding uncertainties (95% confidence interval width for a normal distribution for each estimate). Distributions are rescaled to match the height of each distribution.

The results of a cumulative link mixed effects model for beauty and liking ratings showed that culture (beauty: β = 0.70, p = 0.006; liking: β = 1.01, p = 0.09; enjoyability: β = 0.47, p = 0.07), dance expertise (liking: β = 0.58, p = 0.02; enjoyability: β = 0.60, p = 0.02) the two-way interactions of dance style and expertise (beauty: β = 0.65, p = 0.01; liking: β = 0.69, p = 0.02; enjoyability: β = 0.53, p = 0.06), and dance style and culture (beauty: β = 0.77, p = 0.006) and the three way interaction of dance style, expertise, and culture (beauty: β = 1.32, p = 0.01; liking: β = 1.30, p = 0.02; enjoyability: β = 1.36, p = 0.01) had an effect on the ratings of beauty, liking, and enjoyability (Table S13 ). Specifically, while the two-way culture by dance style interaction suggests that Western participants rated ballet as more beautiful than Bharatanatyam, and Indian participants rated Bharatanatyam as more beautiful than ballet, post hoc tests revealed than an ingroup bias was present such that only Western non-experts showed higher ratings of beauty, liking, and enjoyability for ballet (beauty: M = 1.01, SE = 0.34, 95% CI [0.34, 1.67]; liking: M = 0.46, SE = 0.35, 95% CI [− 0.24, 1.15] ; enjoyability: M = 0.27, SE = 0.34, 95% CI [− 0.39, 0.93]) compared to Bharatanatyam (beauty: M = − 0.18, SE = 0.35, 95% CI [− 0.86, 0.50], p < 0.001; liking: M = − 0.35, SE = 0.37, 95% CI [− 1.08, 0.38], p = 0.05; enjoyability: M = − 0.31, SE = 0.37, 95% CI [− 1.03, 0.42], p = 0.05; see Table S13 , Fig. 12 A–C).

The effect of dance style (Bharatanatyam or ballet depicted in red and blue respectively), expertise (art experts or non-experts) and culture (Indian participants or Western participants) on the ratings of beauty ( A ), liking ( B ), and ( C ) enjoyability.

Similar to RQ1, we ran an additional model adding the subjective variables of familiarity, evocativeness, complexity, reproducibility, and technical competency as fixed effects. As expected, all subjective variables influenced the ratings of beauty and liking such that higher ratings of familiarity, evocativeness, complexity, technical competency, and reproducibility predicted higher ratings of beauty and liking. Adding the subjective variables significantly improved our main models (beauty: AIC main = 8636.42, AIC subj = 6977.28, p < 0.001; liking: AIC main = 8743.3, AIC subj = 7241.4, p < 0.001; enjoyability: AIC main = 8814.7, AIC subj = 7307.7, p < 0.001). Importantly, the three-way interaction still influenced beauty, liking, and enjoyability ratings even when accounting for the possible contributions of the subjective variables (beauty: β = 0.84, p = 0.06; liking: β = 0.99, p = 0.05; enjoyability: β = 0.98, p = 0.05); see Table S13 , Fig. 13 A–C).