Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on June 19, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, history, etc.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organization?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography , action research , phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasize different aims and perspectives.

Note that qualitative research is at risk for certain research biases including the Hawthorne effect , observer bias , recall bias , and social desirability bias . While not always totally avoidable, awareness of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data can prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves “instruments” in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analyzing the data.

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organize your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorize your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analyzing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasize different concepts.

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analyzing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability

The real-world setting often makes qualitative research unreliable because of uncontrolled factors that affect the data.

- Subjectivity

Due to the researcher’s primary role in analyzing and interpreting data, qualitative research cannot be replicated . The researcher decides what is important and what is irrelevant in data analysis, so interpretations of the same data can vary greatly.

- Limited generalizability

Small samples are often used to gather detailed data about specific contexts. Despite rigorous analysis procedures, it is difficult to draw generalizable conclusions because the data may be biased and unrepresentative of the wider population .

- Labor-intensive

Although software can be used to manage and record large amounts of text, data analysis often has to be checked or performed manually.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organization to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved March 23, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, how to do thematic analysis | step-by-step guide & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Social Work Research Methods

Introduction.

- History of Social Work Research Methods

- Feasibility Issues Influencing the Research Process

- Measurement Methods

- Existing Scales

- Group Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Evaluating Outcome

- Single-System Designs for Evaluating Outcome

- Program Evaluation

- Surveys and Sampling

- Introductory Statistics Texts

- Advanced Aspects of Inferential Statistics

- Qualitative Research Methods

- Qualitative Data Analysis

- Historical Research Methods

- Meta-Analysis and Systematic Reviews

- Research Ethics

- Culturally Competent Research Methods

- Teaching Social Work Research Methods

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Community-Based Participatory Research

- Economic Evaluation

- Evidence-based Social Work Practice

- Evidence-based Social Work Practice: Finding Evidence

- Evidence-based Social Work Practice: Issues, Controversies, and Debates

- Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs

- Impact of Emerging Technology in Social Work Practice

- Implementation Science and Practice

- Interviewing

- Measurement, Scales, and Indices

- Meta-analysis

- Occupational Social Work

- Postmodernism and Social Work

- Qualitative Research

- Research, Best Practices, and Evidence-based Group Work

- Social Intervention Research

- Social Work Profession

- Systematic Review Methods

- Technology for Social Work Interventions

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Child Welfare Effectiveness

- Immigration and Child Welfare

- International Human Trafficking

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Social Work Research Methods by Allen Rubin LAST REVIEWED: 28 April 2017 LAST MODIFIED: 14 December 2009 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780195389678-0008

Social work research means conducting an investigation in accordance with the scientific method. The aim of social work research is to build the social work knowledge base in order to solve practical problems in social work practice or social policy. Investigating phenomena in accordance with the scientific method requires maximal adherence to empirical principles, such as basing conclusions on observations that have been gathered in a systematic, comprehensive, and objective fashion. The resources in this entry discuss how to do that as well as how to utilize and teach research methods in social work. Other professions and disciplines commonly produce applied research that can guide social policy or social work practice. Yet no commonly accepted distinction exists at this time between social work research methods and research methods in allied fields relevant to social work. Consequently useful references pertaining to research methods in allied fields that can be applied to social work research are included in this entry.

This section includes basic textbooks that are used in courses on social work research methods. Considerable variation exists between textbooks on the broad topic of social work research methods. Some are comprehensive and delve into topics deeply and at a more advanced level than others. That variation is due in part to the different needs of instructors at the undergraduate and graduate levels of social work education. Most instructors at the undergraduate level prefer shorter and relatively simplified texts; however, some instructors teaching introductory master’s courses on research prefer such texts too. The texts in this section that might best fit their preferences are by Yegidis and Weinbach 2009 and Rubin and Babbie 2007 . The remaining books might fit the needs of instructors at both levels who prefer a more comprehensive and deeper coverage of research methods. Among them Rubin and Babbie 2008 is perhaps the most extensive and is often used at the doctoral level as well as the master’s and undergraduate levels. Also extensive are Drake and Jonson-Reid 2007 , Grinnell and Unrau 2007 , Kreuger and Neuman 2006 , and Thyer 2001 . What distinguishes Drake and Jonson-Reid 2007 is its heavy inclusion of statistical and Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) content integrated with each chapter. Grinnell and Unrau 2007 and Thyer 2001 are unique in that they are edited volumes with different authors for each chapter. Kreuger and Neuman 2006 takes Neuman’s social sciences research text and adapts it to social work. The Practitioner’s Guide to Using Research for Evidence-based Practice ( Rubin 2007 ) emphasizes the critical appraisal of research, covering basic research methods content in a relatively simplified format for instructors who want to teach research methods as part of the evidence-based practice process instead of with the aim of teaching students how to produce research.

Drake, Brett, and Melissa Jonson-Reid. 2007. Social work research methods: From conceptualization to dissemination . Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

This introductory text is distinguished by its use of many evidence-based practice examples and its heavy coverage of statistical and computer analysis of data.

Grinnell, Richard M., and Yvonne A. Unrau, eds. 2007. Social work research and evaluation: Quantitative and qualitative approaches . 8th ed. New York: Oxford Univ. Press.

Contains chapters written by different authors, each focusing on a comprehensive range of social work research topics.

Kreuger, Larry W., and W. Lawrence Neuman. 2006. Social work research methods: Qualitative and quantitative applications . Boston: Pearson, Allyn, and Bacon.

An adaptation to social work of Neuman's social sciences research methods text. Its framework emphasizes comparing quantitative and qualitative approaches. Despite its title, quantitative methods receive more attention than qualitative methods, although it does contain considerable qualitative content.

Rubin, Allen. 2007. Practitioner’s guide to using research for evidence-based practice . Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

This text focuses on understanding quantitative and qualitative research methods and designs for the purpose of appraising research as part of the evidence-based practice process. It also includes chapters on instruments for assessment and monitoring practice outcomes. It can be used at the graduate or undergraduate level.

Rubin, Allen, and Earl R. Babbie. 2007. Essential research methods for social work . Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks Cole.

This is a shorter and less advanced version of Rubin and Babbie 2008 . It can be used for research methods courses at the undergraduate or master's levels of social work education.

Rubin, Allen, and Earl R. Babbie. Research Methods for Social Work . 6th ed. Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks Cole, 2008.

This comprehensive text focuses on producing quantitative and qualitative research as well as utilizing such research as part of the evidence-based practice process. It is widely used for teaching research methods courses at the undergraduate, master’s, and doctoral levels of social work education.

Thyer, Bruce A., ed. 2001 The handbook of social work research methods . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

This comprehensive compendium includes twenty-nine chapters written by esteemed leaders in social work research. It covers quantitative and qualitative methods as well as general issues.

Yegidis, Bonnie L., and Robert W. Weinbach. 2009. Research methods for social workers . 6th ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

This introductory paperback text covers a broad range of social work research methods and does so in a briefer fashion than most lengthier, hardcover introductory research methods texts.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Social Work »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Adolescent Depression

- Adolescent Pregnancy

- Adolescents

- Adoption Home Study Assessments

- Adult Protective Services in the United States

- African Americans

- Aging out of foster care

- Aging, Physical Health and

- Alcohol and Drug Abuse Problems

- Alcohol and Drug Problems, Prevention of Adolescent and Yo...

- Alcohol Problems: Practice Interventions

- Alcohol Use Disorder

- Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias

- Anti-Oppressive Practice

- Asian Americans

- Asian-American Youth

- Autism Spectrum Disorders

- Baccalaureate Social Workers

- Behavioral Health

- Behavioral Social Work Practice

- Bereavement Practice

- Bisexuality

- Brief Therapies in Social Work: Task-Centered Model and So...

- Bullying and Social Work Intervention

- Canadian Social Welfare, History of

- Case Management in Mental Health in the United States

- Central American Migration to the United States

- Child Maltreatment Prevention

- Child Neglect and Emotional Maltreatment

- Child Poverty

- Child Sexual Abuse

- Child Welfare

- Child Welfare and Child Protection in Europe, History of

- Child Welfare Practice with LGBTQ Youth and Families

- Children of Incarcerated Parents

- Christianity and Social Work

- Chronic Illness

- Clinical Social Work Practice with Adult Lesbians

- Clinical Social Work Practice with Males

- Cognitive Behavior Therapies with Diverse and Stressed Pop...

- Cognitive Processing Therapy

- Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

- Community Development

- Community Policing

- Community-Needs Assessment

- Comparative Social Work

- Computational Social Welfare: Applying Data Science in Soc...

- Conflict Resolution

- Council on Social Work Education

- Counseling Female Offenders

- Criminal Justice

- Crisis Interventions

- Cultural Competence and Ethnic Sensitive Practice

- Culture, Ethnicity, Substance Use, and Substance Use Disor...

- Dementia Care

- Dementia Care, Ethical Aspects of

- Depression and Cancer

- Development and Infancy (Birth to Age Three)

- Differential Response in Child Welfare

- Digital Storytelling for Social Work Interventions

- Direct Practice in Social Work

- Disabilities

- Disability and Disability Culture

- Domestic Violence Among Immigrants

- Early Pregnancy and Parenthood Among Child Welfare–Involve...

- Eating Disorders

- Ecological Framework

- Elder Mistreatment

- End-of-Life Decisions

- Epigenetics for Social Workers

- Ethical Issues in Social Work and Technology

- Ethics and Values in Social Work

- European Institutions and Social Work

- European Union, Justice and Home Affairs in the

- Evidence-based Social Work Practice: Issues, Controversies...

- Families with Gay, Lesbian, or Bisexual Parents

- Family Caregiving

- Family Group Conferencing

- Family Policy

- Family Services

- Family Therapy

- Family Violence

- Fathering Among Families Served By Child Welfare

- Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders

- Field Education

- Financial Literacy and Social Work

- Financing Health-Care Delivery in the United States

- Forensic Social Work

- Foster Care

- Foster care and siblings

- Gender, Violence, and Trauma in Immigration Detention in t...

- Generalist Practice and Advanced Generalist Practice

- Grounded Theory

- Group Work across Populations, Challenges, and Settings

- Group Work, Research, Best Practices, and Evidence-based

- Harm Reduction

- Health Care Reform

- Health Disparities

- Health Social Work

- History of Social Work and Social Welfare, 1900–1950

- History of Social Work and Social Welfare, 1950-1980

- History of Social Work and Social Welfare, pre-1900

- History of Social Work from 1980-2014

- History of Social Work in China

- History of Social Work in Northern Ireland

- History of Social Work in the Republic of Ireland

- History of Social Work in the United Kingdom

- HIV/AIDS and Children

- HIV/AIDS Prevention with Adolescents

- Homelessness

- Homelessness: Ending Homelessness as a Grand Challenge

- Homelessness Outside the United States

- Human Needs

- Human Trafficking, Victims of

- Immigrant Integration in the United States

- Immigrant Policy in the United States

- Immigrants and Refugees

- Immigrants and Refugees: Evidence-based Social Work Practi...

- Immigration and Health Disparities

- Immigration and Intimate Partner Violence

- Immigration and Poverty

- Immigration and Spirituality

- Immigration and Substance Use

- Immigration and Trauma

- Impaired Professionals

- Indigenous Peoples

- Individual Placement and Support (IPS) Supported Employmen...

- In-home Child Welfare Services

- Intergenerational Transmission of Maltreatment

- International Social Welfare

- International Social Work

- International Social Work and Education

- International Social Work and Social Welfare in Southern A...

- Internet and Video Game Addiction

- Interpersonal Psychotherapy

- Intervention with Traumatized Populations

- Intimate-Partner Violence

- Juvenile Justice

- Kinship Care

- Korean Americans

- Latinos and Latinas

- Law, Social Work and the

- LGBTQ Populations and Social Work

- Mainland European Social Work, History of

- Major Depressive Disorder

- Management and Administration in Social Work

- Maternal Mental Health

- Medical Illness

- Men: Health and Mental Health Care

- Mental Health

- Mental Health Diagnosis and the Addictive Substance Disord...

- Mental Health Needs of Older People, Assessing the

- Mental Illness: Children

- Mental Illness: Elders

- Microskills

- Middle East and North Africa, International Social Work an...

- Military Social Work

- Mixed Methods Research

- Moral distress and injury in social work

- Motivational Interviewing

- Multiculturalism

- Native Americans

- Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders

- Neighborhood Social Cohesion

- Neuroscience and Social Work

- Nicotine Dependence

- Organizational Development and Change

- Pain Management

- Palliative Care

- Palliative Care: Evolution and Scope of Practice

- Pandemics and Social Work

- Parent Training

- Personalization

- Person-in-Environment

- Philosophy of Science and Social Work

- Physical Disabilities

- Podcasts and Social Work

- Police Social Work

- Political Social Work in the United States

- Positive Youth Development

- Postsecondary Education Experiences and Attainment Among Y...

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Practice Interventions and Aging

- Practice Interventions with Adolescents

- Practice Research

- Primary Prevention in the 21st Century

- Productive Engagement of Older Adults

- Profession, Social Work

- Program Development and Grant Writing

- Promoting Smart Decarceration as a Grand Challenge

- Psychiatric Rehabilitation

- Psychoanalysis and Psychodynamic Theory

- Psychoeducation

- Psychometrics

- Psychopathology and Social Work Practice

- Psychopharmacology and Social Work Practice

- Psychosocial Framework

- Psychosocial Intervention with Women

- Psychotherapy and Social Work

- Race and Racism

- Readmission Policies in Europe

- Redefining Police Interactions with People Experiencing Me...

- Rehabilitation

- Religiously Affiliated Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Restorative Justice

- Risk Assessment in Child Protection Services

- Risk Management in Social Work

- Rural Social Work in China

- Rural Social Work Practice

- School Social Work

- School Violence

- School-Based Delinquency Prevention

- Services and Programs for Pregnant and Parenting Youth

- Severe and Persistent Mental Illness: Adults

- Sexual and Gender Minority Immigrants, Refugees, and Asylu...

- Sexual Assault

- Single-System Research Designs

- Social and Economic Impact of US Immigration Policies on U...

- Social Development

- Social Insurance and Social Justice

- Social Justice and Social Work

- Social Movements

- Social Planning

- Social Policy

- Social Policy in Denmark

- Social Security in the United States (OASDHI)

- Social Work and Islam

- Social Work and Social Welfare in East, West, and Central ...

- Social Work and Social Welfare in Europe

- Social Work Education and Research

- Social Work Leadership

- Social Work Luminaries: Luminaries Contributing to the Cla...

- Social Work Luminaries: Luminaries contributing to the fou...

- Social Work Luminaries: Luminaries Who Contributed to Soci...

- Social Work Regulation

- Social Work Research Methods

- Social Work with Interpreters

- Solution-Focused Therapy

- Strategic Planning

- Strengths Perspective

- Strengths-Based Models in Social Work

- Supplemental Security Income

- Survey Research

- Sustainability: Creating Social Responses to a Changing En...

- Syrian Refugees in Turkey

- Task-Centered Practice

- Technology Adoption in Social Work Education

- Technology, Human Relationships, and Human Interaction

- Technology in Social Work

- Terminal Illness

- The Impact of Systemic Racism on Latinxs’ Experiences with...

- Transdisciplinary Science

- Translational Science and Social Work

- Transnational Perspectives in Social Work

- Transtheoretical Model of Change

- Trauma-Informed Care

- Triangulation

- Tribal child welfare practice in the United States

- United States, History of Social Welfare in the

- Universal Basic Income

- Veteran Services

- Vicarious Trauma and Resilience in Social Work Practice wi...

- Vicarious Trauma Redefining PTSD

- Victim Services

- Virtual Reality and Social Work

- Welfare State Reform in France

- Welfare State Theory

- Women and Macro Social Work Practice

- Women's Health Care

- Work and Family in the German Welfare State

- Workforce Development of Social Workers Pre- and Post-Empl...

- Working with Non-Voluntary and Mandated Clients

- Young and Adolescent Lesbians

- Youth at Risk

- Youth Services

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|195.158.225.244]

- 195.158.225.244

Qualitative Research : Definition

Qualitative research is the naturalistic study of social meanings and processes, using interviews, observations, and the analysis of texts and images. In contrast to quantitative researchers, whose statistical methods enable broad generalizations about populations (for example, comparisons of the percentages of U.S. demographic groups who vote in particular ways), qualitative researchers use in-depth studies of the social world to analyze how and why groups think and act in particular ways (for instance, case studies of the experiences that shape political views).

- Next: Choose an approach >>

- Choose an approach

- Find studies

- Learn methods

- Get software

- Get data for secondary analysis

- Network with researchers

- Last Updated: Jan 31, 2024 9:21 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.stanford.edu/qualitative_research

Social Work Research Methods That Drive the Practice

Social workers advocate for the well-being of individuals, families and communities. But how do social workers know what interventions are needed to help an individual? How do they assess whether a treatment plan is working? What do social workers use to write evidence-based policy?

Social work involves research-informed practice and practice-informed research. At every level, social workers need to know objective facts about the populations they serve, the efficacy of their interventions and the likelihood that their policies will improve lives. A variety of social work research methods make that possible.

Data-Driven Work

Data is a collection of facts used for reference and analysis. In a field as broad as social work, data comes in many forms.

Quantitative vs. Qualitative

As with any research, social work research involves both quantitative and qualitative studies.

Quantitative Research

Answers to questions like these can help social workers know about the populations they serve — or hope to serve in the future.

- How many students currently receive reduced-price school lunches in the local school district?

- How many hours per week does a specific individual consume digital media?

- How frequently did community members access a specific medical service last year?

Quantitative data — facts that can be measured and expressed numerically — are crucial for social work.

Quantitative research has advantages for social scientists. Such research can be more generalizable to large populations, as it uses specific sampling methods and lends itself to large datasets. It can provide important descriptive statistics about a specific population. Furthermore, by operationalizing variables, it can help social workers easily compare similar datasets with one another.

Qualitative Research

Qualitative data — facts that cannot be measured or expressed in terms of mere numbers or counts — offer rich insights into individuals, groups and societies. It can be collected via interviews and observations.

- What attitudes do students have toward the reduced-price school lunch program?

- What strategies do individuals use to moderate their weekly digital media consumption?

- What factors made community members more or less likely to access a specific medical service last year?

Qualitative research can thereby provide a textured view of social contexts and systems that may not have been possible with quantitative methods. Plus, it may even suggest new lines of inquiry for social work research.

Mixed Methods Research

Combining quantitative and qualitative methods into a single study is known as mixed methods research. This form of research has gained popularity in the study of social sciences, according to a 2019 report in the academic journal Theory and Society. Since quantitative and qualitative methods answer different questions, merging them into a single study can balance the limitations of each and potentially produce more in-depth findings.

However, mixed methods research is not without its drawbacks. Combining research methods increases the complexity of a study and generally requires a higher level of expertise to collect, analyze and interpret the data. It also requires a greater level of effort, time and often money.

The Importance of Research Design

Data-driven practice plays an essential role in social work. Unlike philanthropists and altruistic volunteers, social workers are obligated to operate from a scientific knowledge base.

To know whether their programs are effective, social workers must conduct research to determine results, aggregate those results into comprehensible data, analyze and interpret their findings, and use evidence to justify next steps.

Employing the proper design ensures that any evidence obtained during research enables social workers to reliably answer their research questions.

Research Methods in Social Work

The various social work research methods have specific benefits and limitations determined by context. Common research methods include surveys, program evaluations, needs assessments, randomized controlled trials, descriptive studies and single-system designs.

Surveys involve a hypothesis and a series of questions in order to test that hypothesis. Social work researchers will send out a survey, receive responses, aggregate the results, analyze the data, and form conclusions based on trends.

Surveys are one of the most common research methods social workers use — and for good reason. They tend to be relatively simple and are usually affordable. However, surveys generally require large participant groups, and self-reports from survey respondents are not always reliable.

Program Evaluations

Social workers ally with all sorts of programs: after-school programs, government initiatives, nonprofit projects and private programs, for example.

Crucially, social workers must evaluate a program’s effectiveness in order to determine whether the program is meeting its goals and what improvements can be made to better serve the program’s target population.

Evidence-based programming helps everyone save money and time, and comparing programs with one another can help social workers make decisions about how to structure new initiatives. Evaluating programs becomes complicated, however, when programs have multiple goal metrics, some of which may be vague or difficult to assess (e.g., “we aim to promote the well-being of our community”).

Needs Assessments

Social workers use needs assessments to identify services and necessities that a population lacks access to.

Common social work populations that researchers may perform needs assessments on include:

- People in a specific income group

- Everyone in a specific geographic region

- A specific ethnic group

- People in a specific age group

In the field, a social worker may use a combination of methods (e.g., surveys and descriptive studies) to learn more about a specific population or program. Social workers look for gaps between the actual context and a population’s or individual’s “wants” or desires.

For example, a social worker could conduct a needs assessment with an individual with cancer trying to navigate the complex medical-industrial system. The social worker may ask the client questions about the number of hours they spend scheduling doctor’s appointments, commuting and managing their many medications. After learning more about the specific client needs, the social worker can identify opportunities for improvements in an updated care plan.

In policy and program development, social workers conduct needs assessments to determine where and how to effect change on a much larger scale. Integral to social work at all levels, needs assessments reveal crucial information about a population’s needs to researchers, policymakers and other stakeholders. Needs assessments may fall short, however, in revealing the root causes of those needs (e.g., structural racism).

Randomized Controlled Trials

Randomized controlled trials are studies in which a randomly selected group is subjected to a variable (e.g., a specific stimulus or treatment) and a control group is not. Social workers then measure and compare the results of the randomized group with the control group in order to glean insights about the effectiveness of a particular intervention or treatment.

Randomized controlled trials are easily reproducible and highly measurable. They’re useful when results are easily quantifiable. However, this method is less helpful when results are not easily quantifiable (i.e., when rich data such as narratives and on-the-ground observations are needed).

Descriptive Studies

Descriptive studies immerse the researcher in another context or culture to study specific participant practices or ways of living. Descriptive studies, including descriptive ethnographic studies, may overlap with and include other research methods:

- Informant interviews

- Census data

- Observation

By using descriptive studies, researchers may glean a richer, deeper understanding of a nuanced culture or group on-site. The main limitations of this research method are that it tends to be time-consuming and expensive.

Single-System Designs

Unlike most medical studies, which involve testing a drug or treatment on two groups — an experimental group that receives the drug/treatment and a control group that does not — single-system designs allow researchers to study just one group (e.g., an individual or family).

Single-system designs typically entail studying a single group over a long period of time and may involve assessing the group’s response to multiple variables.

For example, consider a study on how media consumption affects a person’s mood. One way to test a hypothesis that consuming media correlates with low mood would be to observe two groups: a control group (no media) and an experimental group (two hours of media per day). When employing a single-system design, however, researchers would observe a single participant as they watch two hours of media per day for one week and then four hours per day of media the next week.

These designs allow researchers to test multiple variables over a longer period of time. However, similar to descriptive studies, single-system designs can be fairly time-consuming and costly.

Learn More About Social Work Research Methods

Social workers have the opportunity to improve the social environment by advocating for the vulnerable — including children, older adults and people with disabilities — and facilitating and developing resources and programs.

Learn more about how you can earn your Master of Social Work online at Virginia Commonwealth University . The highest-ranking school of social work in Virginia, VCU has a wide range of courses online. That means students can earn their degrees with the flexibility of learning at home. Learn more about how you can take your career in social work further with VCU.

From M.S.W. to LCSW: Understanding Your Career Path as a Social Worker

How Palliative Care Social Workers Support Patients With Terminal Illnesses

How to Become a Social Worker in Health Care

Gov.uk, Mixed Methods Study

MVS Open Press, Foundations of Social Work Research

Open Social Work Education, Scientific Inquiry in Social Work

Open Social Work, Graduate Research Methods in Social Work: A Project-Based Approach

Routledge, Research for Social Workers: An Introduction to Methods

SAGE Publications, Research Methods for Social Work: A Problem-Based Approach

Theory and Society, Mixed Methods Research: What It Is and What It Could Be

READY TO GET STARTED WITH OUR ONLINE M.S.W. PROGRAM FORMAT?

Want to learn more about the program and application process? Get in touch with the form below.

Bachelor’s degree is required to attend.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

5.2 Conceptualization

Learning objectives.

- Define concept

- Identify why defining our concepts is important

- Describe how conceptualization works in quantitative and qualitative research

- Define dimensions in terms of social scientific measurement

- Apply reification to conceptualization

In this section, we’ll take a look at one of the first steps in the measurement process, which is conceptualization. This has to do with defining our terms as clearly as possible and also not taking ourselves too seriously in the process. Our definitions mean only what we say they mean—nothing more and nothing less. Let’s talk first about how to define our terms, and then we’ll examine not taking ourselves (or our terms, rather) too seriously.

Concepts and conceptualization

So far, the word concept has come up quite a bit, and it would behoove us to make sure we have a shared understanding of that term. A concept is the notion or image that we conjure up when we think of some cluster of related observations or ideas. For example, masculinity is a concept. What do you think of when you hear that word? Presumably, you imagine some set of behaviors and perhaps even a particular style of self-presentation. Of course, we can’t necessarily assume that everyone conjures up the same set of ideas or images when they hear the word masculinity . In fact, there are many possible ways to define the term. And while some definitions may be more common or have more support than others, there isn’t one true, always-correct-in-all-settings definition. What counts as masculine may shift over time, from culture to culture, and even from individual to individual (Kimmel, 2008). This is why defining our concepts is so important.

You might be asking yourself why you should bother defining a term for which there is no single, correct definition. Believe it or not, this is true for any concept you might measure in a research study—there is never a single, always-correct definition. When we conduct empirical research, our terms mean only what we say they mean. There’s a New Yorker cartoon that aptly represents this idea. It depicts a young George Washington holding an axe and standing near a freshly chopped cherry tree. Young George is looking up at a frowning adult who is standing over him, arms crossed. The caption depicts George explaining, “It all depends on how you define ‘chop.’” Young George Washington gets the idea—whether he actually chopped down the cherry tree depends on whether we have a shared understanding of the term chop .

Without a shared understanding of this term, our understandings of what George has just done may differ. Likewise, without understanding how a researcher has defined her key concepts, it would be nearly impossible to understand the meaning of that researcher’s findings and conclusions. Thus, any decision we make based on findings from empirical research should be made based on full knowledge not only of how the research was designed, but also of how its concepts were defined and measured.

So, how do we define our concepts? This is part of the process of measurement, and this portion of the process is called conceptualization. The answer depends on how we plan to approach our research. We will begin with quantitative conceptualization and then discuss qualitative conceptualization.

In quantitative research, conceptualization involves writing out clear, concise definitions for our key concepts. Sticking with the previously mentioned example of masculinity, think about what comes to mind when you read that term. How do you know masculinity when you see it? Does it have something to do with men? With social norms? If so, perhaps we could define masculinity as the social norms that men are expected to follow. That seems like a reasonable start, and at this early stage of conceptualization, brainstorming about the images conjured up by concepts and playing around with possible definitions is appropriate. However, this is just the first step.

It would make sense as well to consult other previous research and theory to understand if other scholars have already defined the concepts we’re interested in. This doesn’t necessarily mean we must use their definitions, but understanding how concepts have been defined in the past will give us an idea about how our conceptualizations compare with the predominant ones out there. Understanding prior definitions of our key concepts will also help us decide whether we plan to challenge those conceptualizations or rely on them for our own work. Finally, working on conceptualization is likely to help in the process of refining your research question to one that is specific and clear in what it asks.

If we turn to the literature on masculinity, we will surely come across work by Michael Kimmel, one of the preeminent masculinity scholars in the United States. After consulting Kimmel’s prior work (2000; 2008), we might tweak our initial definition of masculinity just a bit. Rather than defining masculinity as “the social norms that men are expected to follow,” perhaps instead we’ll define it as “the social roles, behaviors, and meanings prescribed for men in any given society at any one time” (Kimmel & Aronson, 2004, p. 503). Our revised definition is both more precise and more complex. Rather than simply addressing one aspect of men’s lives (norms), our new definition addresses three aspects: roles, behaviors, and meanings. It also implies that roles, behaviors, and meanings may vary across societies and over time. To be clear, we’ll also have to specify the particular society and time period we’re investigating as we conceptualize masculinity.

As you can see, conceptualization isn’t quite as simple as merely applying any random definition that we come up with to a term. Sure, it may involve some initial brainstorming, but conceptualization goes beyond that. Once we’ve brainstormed a bit about the images a particular word conjures up for us, we should also consult prior work to understand how others define the term in question. And after we’ve identified a clear definition that we’re happy with, we should make sure that every term used in our definition will make sense to others. Are there terms used within our definition that also need to be defined? If so, our conceptualization is not yet complete. And there is yet another aspect of conceptualization to consider—concept dimensions. We’ll consider that aspect along with an additional word of caution about conceptualization in the next subsection.

Conceptualization in qualitative research

Conceptualization in qualitative research proceeds a bit differently than in quantitative research. Because qualitative researchers are interested in the understandings and experiences of their participants, it is less important for the researcher to find one fixed definition for a concept before starting to interview or interact with participants. The researcher’s job is to accurately and completely represent how their participants understand a concept, not to test their own definition of that concept.

If you were conducting qualitative research on masculinity, you would likely consult previous literature like Kimmel’s work mentioned above. From your literature review, you may come up with a working definition for the terms you plan to use in your study, which can change over the course of the investigation. However, the definition that matters is the definition that your participants share during data collection. A working definition is merely a place to start, and researchers should take care not to think it is the only or best definition out there.

In qualitative inquiry, your participants are the experts (sound familiar, social workers?) on the concepts that arise during the research study. Your job as the researcher is to accurately and reliably collect and interpret their understanding of the concepts they describe while answering your questions. Conceptualization of qualitative concepts is likely to change over the course of qualitative inquiry, as you learn more information from your participants. Indeed, getting participants to comment on, extend, or challenge the definitions and understandings of other participants is a hallmark of qualitative research. This is the opposite of quantitative research, in which definitions must be completely set in stone before the inquiry can begin.

A word of caution about conceptualization

Whether you have chosen qualitative or quantitative methods, you should have a clear definition for the term masculinity and make sure that the terms we use in our definition are equally clear—and then we’re done, right? Not so fast. If you’ve ever met more than one man in your life, you’ve probably noticed that they are not all exactly the same, even if they live in the same society and at the same historical time period. This could mean there are dimensions of masculinity. In terms of social scientific measurement, concepts can be said to have multiple dimensions when there are multiple elements that make up a single concept. With respect to the term masculinity , dimensions could be regional (is masculinity defined differently in different regions of the same country?), age-based (is masculinity defined differently for men of different ages?), or perhaps power-based (does masculinity differ based on membership to privileged groups?). In any of these cases, the concept of masculinity would be considered to have multiple dimensions. While it isn’t necessarily required to spell out every possible dimension of the concepts you wish to measure, it may be important to do so depending on the goals of your research. The point here is to be aware that some concepts have dimensions and to think about whether and when dimensions may be relevant to the concepts you intend to investigate.

Before we move on to the additional steps involved in the measurement process, it would be wise to remind ourselves not to take our definitions too seriously. Conceptualization must be open to revisions, even radical revisions, as scientific knowledge progresses. Although that we should consult prior scholarly definitions of our concepts, it would be wrong to assume that just because prior definitions exist that they are more real than the definitions we create (or, likewise, that our own made-up definitions are any more real than any other definition). It would also be wrong to assume that just because definitions exist for some concept that the concept itself exists beyond some abstract idea in our heads. This idea, assuming that our abstract concepts exist in some concrete, tangible way, is known as reification .

To better understand reification, take a moment to think about the concept of social structure. This concept is central to critical thinking. When social scientists talk about social structure, they are talking about an abstract concept. Social structures shape our ways of being in the world and of interacting with one another, but they do not exist in any concrete or tangible way. A social structure isn’t the same thing as other sorts of structures, such as buildings or bridges. Sure, both types of structures are important to how we live our everyday lives, but one we can touch, and the other is just an idea that shapes our way of living.

Here’s another way of thinking about reification: Think about the term family . If you were interested in studying this concept, we’ve learned that it would be good to consult prior theory and research to understand how the term has been conceptualized by others. But we should also question past conceptualizations. Think, for example, about how different the definition of family was 50 years ago. Because researchers from that time period conceptualized family using now outdated social norms, social scientists from 50 years ago created research projects based on what we consider now to be a very limited and problematic notion of what family means. Their definitions of family were as real to them as our definitions are to us today. If researchers never challenged the definitions of terms like family, our scientific knowledge would be filled with the prejudices and blind spots from years ago. It makes sense to come to some social agreement about what various concepts mean. Without that agreement, it would be difficult to navigate through everyday living. But at the same time, we should not forget that we have assigned those definitions, they are imperfect and subject to change as a result of critical inquiry.

Key Takeaways

- Conceptualization is a process that involves coming up with clear, concise definitions.

- Conceptualization in quantitative research comes from the researcher’s ideas or the literature.

- Qualitative researchers conceptualize by creating working definitions which will be revised based on what participants say.

- Some concepts have multiple elements or dimensions.

- Researchers should acknowledge the limitations of their definitions for concepts.

- Concept- notion or image that we conjure up when we think of some cluster of related observations or ideas

- Conceptualization- writing out clear, concise definitions for our key concepts, particularly in quantitative research

- Multi-dimensional concepts- concepts that are comprised of multiple elements

- Reification- assuming that abstract concepts exist in some concrete, tangible way

Image attributions

thought by TeroVesalainen CC-0

mindmap by TeroVesalainen CC-0

Foundations of Social Work Research Copyright © 2020 by Rebecca L. Mauldin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Fieldwork in Social Work pp 119–141 Cite as

Data Collection for Field Reports in Social Work Practice

- M. Rezaul Islam ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2217-7507 2

- First Online: 22 March 2024

This chapter equips social work students with essential skills for gathering and utilizing data effectively. It begins by providing an overview of both qualitative and quantitative data collection techniques, ensuring that students are well-versed in diverse methods. The chapter then focuses on the practical aspect of data collection, emphasizing the use of data collection tools and instruments to streamline the process and enhance data quality. Through this chapter, social work students gain the knowledge and skills necessary to collect, manage, and utilize data to inform their practice, enhancing their ability to make data-driven decisions in the field.

- Data collection methods

- Qualitative data

- Quantitative data

- Data collection tools

- Field practices

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Akhter, S. (2022). Key informants’ interviews. In M. R. Islam, N. A. Khan, & R. Baikady (Eds.), Principles of social research methodology. Springer. Principles of social research methodology (pp. 389–403). Springer Nature Singapore.

Google Scholar

Azam, M. G. (2022). In-depth case interview. In M. R. Islam, N. A. Khan, & R. Baikady (Eds.), Principles of social research methodology. Springer. Principles of social research methodology (pp. 347–364). Springer Nature Singapore.

Gray, M., Plath, D., & Webb, S. (2009). Evidence-based social work: A critical stance . Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Islam, M. R. (2022). Participatory research. In M. R. Islam, N. A. Khan, & R. Baikady (Eds.), Principles of social research methodology. Springer. Principles of social research methodology (pp. 291–311). Springer Nature Singapore.

Khan, N. A., & Abedin, S. (2022). Focus group discussion. In M. R. Islam, N. A. Khan, & R. Baikady (Eds.), Principles of social research methodology. Springer. Principles of social research methodology (pp. 377–387). Springer Nature Singapore.

Margaryan, A., Littlejohn, A., & Vojt, G. (2011). Are digital natives a myth or reality? University students’ use of digital technologies. Computers & Education, 56 (2), 429–440.

Article Google Scholar

Pollock, K. (2012). Procedure versus process: Ethical paradigms and the conduct of qualitative research. BMC Medical Ethics, 13 , 1–12.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Social Welfare and Research, University of Dhaka, Dhaka, Bangladesh

M. Rezaul Islam

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Review Questions

What is the primary purpose of data collection in social work field practice?

Name two qualitative data collection techniques discussed in this chapter and briefly explain their applications.

Briefly outline the ethical considerations related to participant autonomy and privacy in data collection.

Why is it beneficial to integrate mixed-methods approaches in social work field research?

Discuss the role of technology in data collection for social work field practices, highlighting its advantages and potential ethical considerations.

Multiple Choice Questions

What is the main advantage of utilizing mixed-methods approaches in social work field research?

Simplicity in data analysis

Increased depth and breadth of understanding

Limited perspectives on the research question

Narrow scope of data collection

Which of the following is an example of a qualitative data collection technique?

Statistical analysis

Content analysis

Standardized tests

What is a key ethical consideration in technology-mediated data collection?

Limited access to data

Participant anonymity

Informed consent

Avoidance of data encryption

In quantitative data collection, what method involves asking participants to respond to a series of predetermined questions?

Participant observation

Focus group discussions

Surveys and questionnaires

Key informant interviews

Why is ensuring participant autonomy important in social work field research?

It protects the participants’ rights and choices.

It simplifies the research process.

It reduces the need for informed consent.

It limits the diversity of collected data.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Islam, M.R. (2024). Data Collection for Field Reports in Social Work Practice. In: Fieldwork in Social Work. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-56683-7_9

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-56683-7_9

Published : 22 March 2024

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-56682-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-56683-7

eBook Packages : Social Sciences

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 15 March 2024

Young people's experiences of physical activity insecurity: a qualitative study highlighting intersectional disadvantage in the UK

- Caroline Dodd-Reynolds 1 ,

- Naomi Griffin 2 ,

- Phillippa Kyle 3 ,

- Steph Scott 2 ,

- Hannah Fairbrother 4 ,

- Eleanor Holding 5 ,

- Mary Crowder 5 ,

- Nicholas Woodrow 5 &

- Carolyn Summerbell 1

BMC Public Health volume 24 , Article number: 813 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

453 Accesses

12 Altmetric

Metrics details

Intersecting socioeconomic and demographic reasons for physical activity (PA) inequalities are not well understood for young people at risk of experiencing marginalisation and living with disadvantage. This study explored young people’s experiences of PA in their local area, and the associated impacts on opportunities for good physical and emotional health and wellbeing.

Seven local youth groups were purposefully sampled from disadvantaged areas across urban, rural and coastal areas of England, including two that were specifically for LGBTQ + young people. Each group engaged in three interlinked focus groups which explored young people’s perceptions and lived experience of PA inequalities. Data were analysed using an inductive, reflexive thematic approach to allow for flexibility in coding.

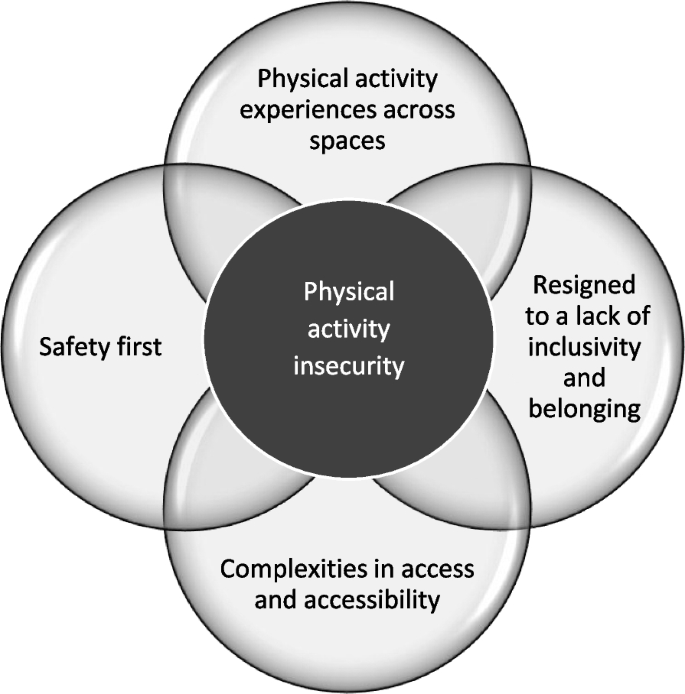

Fifty five young people aged 12–21 years of different sexualities, gender and ethnicity took part. Analysis yielded four themes: PA experiences across spaces; resigned to a lack of inclusivity and ‘belonging’; safety first; complexities in access and accessibility. Young people felt more comfortable to be active in spaces that were simpler to navigate, particularly outdoor locations largely based in nature. In contrast, local gyms and sports clubs, and the school environment in general, were spoken about often in negative terms and as spaces where they experienced insecurity, unsafety or discomfort. It was common for these young people to feel excluded from PA, often linked to their gender and sexuality. Lived experiences or fears of being bullied and harassed in many activity spaces was a powerful message, but in contrast, young people perceived their local youth club as a safe space. Intersecting barriers related to deprivation, gender and sexuality, accessibility, disability, Covid-19, affordability, ethnicity, and proximity of social networks. A need emerged for safe spaces in which young people can come together, within the local community and choose to be active.

Conclusions

The overarching concept of ‘physical activity insecurity’ emerged as a significant concern for the young people in this study. We posit that PA insecurity in this context can be described as a limited or restricted ability to be active, reinforced by worries and lived experiences of feeling uncomfortable, insecure, or unsafe.

Peer Review reports

Three in four adolescents do not meet global physical activity (PA) guidelines [ 1 ] and the annual global cost of inactivity is estimated to be in excess of $67·5 billion [ 2 ]. Adolescent inactivity is unequally distributed between nations, as well as within societies [ 3 ] and in England, only 47% of 13–16 year-olds met national PA guidelines in 2022/23 [ 4 ]. Physical activity is linked to 13 of the 2030 UN sustainable development goals (SDGs) including SDG3 good health and well-being, SDG4 quality education, and SDG10 reduced inequalities [ 1 ]. Through their global action plan, the World Health Organisation (WHO) [ 1 ] presents a mission to ensure access to safe and enabling environments along with diverse opportunities for PA, targeting a 15% relative reduction in inactivity for adults and adolescents by 2030. Despite this global focus, clear gaps in knowledge around policy development and implementation have been highlighted [ 3 ] with a need for supportive policies, environments, and opportunities [ 5 ] for children and young people to be active.

In this paper, we define physical activity as “people moving, acting and performing within culturally specific spaces and contexts, and influenced by a unique array of interests, emotions, ideas, instructions and relationships” ([ 6 ], p. 5). Like health, PA is heavily influenced by intersecting socioeconomic and demographic factors [ 7 , 8 ], yet PA has the potential to improve health equity [ 9 ]. In England, epidemiological data show that children and young people are less likely to meet PA guidelines according to low affluence, gender (girls and 'other'), and ethnicity (Black, Asian, Mixed and Other non-white/non-white British) [ 4 ]. Evidence suggests, however, that individual determinants of young people’s PA are variable and diverse and include previous PA, PE/school sports, independent mobility and active transport, education level and other health behaviours such as alcohol consumption [ 10 , 11 ]. A comprehensive systematic review of over 18-year-olds [ 12 ] reported 117 correlates of PA across a range of demographic, biological, psychological, behavioural, social and environmental factors.

The direct relationship between socioeconomic status (SES) and children’s PA is particularly unclear, with umbrella systematic review evidence [ 13 ] suggesting mixed findings in terms of whether SES is a determinant of PA, though the same study demonstrated a positive association between SES and PA for adults. Individual factors such as parental income and parental occupation, along with payment of fees/equipment did, however, show some evidence of an association with children and adolescent PA [ 13 ]. Whilst the authors note the small number of studies available for children and adolescents, a lack of causal evidence and differing measurement tools which might contribute to the uncertainty around SES and PA, we suggest also that quantitative evidence may well fail to capture the complexity of children and young people’s PA in different spaces. Indeed, a qualitative review of limited extant literature concerning socioeconomic position and experiences of barriers to PA [ 14 ] highlighted issues such as social support, accessibility and environment, and experiences (particularly gendered) of health and other behaviours, but importantly noted that those in low socioeconomic position areas had a good understanding of PA benefits. Better understanding is required regarding the complexity of PA experiences for children and young people living with disadvantage.

Within the PA literature, systems approaches are evolving to map and understand networks and mechanisms within complex systems, ultimately aiming to reduce health inequalities [ 15 , 16 ], and a systems-based framework for action forms a key component of the WHO’s global strategy [ 1 ]. To support this work, better understanding is needed regarding the dynamic, contextual mechanisms which underpin various agents in local systems [ 17 ], for example through understanding better young people’s personal, or direct ‘lived experiences’ of PA. Engaging in dialogue with young people at the heart of local communities, offers a deeper and more nuanced understanding of place-based PA challenges and opportunities.

In general, individuals transitioning from childhood to adulthood are underserved in PA research, yet experiences earlier in life have a lasting effect on adult health and health behaviours [ 7 ]. The 2016 Lancet Commission on adolescent Health and Wellbeing [ 18 ] recommended setting clear objectives for change, based on local needs, and highlighted a gap for young people at risk of being socially and economically marginalised, including LGBT + (lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and others) groups. Adolescents and those on the fringes of adulthood (hereafter referred to as young people) therefore present a critical but wide-ranging group with whom we must seek to better understand PA inequalities, particularly in the context of widening place-based inequality and deprivation and the syndemic 'shock' of the COVID-19 pandemic [ 19 , 20 ]. Accordingly, we have applied the concept of intersectionality [ 21 , 22 ] to explore the complex and intersecting factors which influence access to, and experiences of, PA.

We have recently reported young people’s nuanced understandings of the malleable and dynamic relationships between socioeconomic circumstance and health [ 23 ] and in this paper, we focused on PA specifically. We explored young people’s experiences of PA in their local area, and the associated impacts on opportunities for good physical and emotional health and wellbeing. In doing so we worked with young people who were already at risk of experiencing social and health inequalities across England, UK.

This paper drew on data from a larger project [ 23 ] where a series of three interlinked qualitative focus groups were undertaken with six groups of young people who attended local community youth groups between February and June 2021. For the present study, we recruited a further group (December 2021) to ensure diversity in terms of gender and sexual orientation. In total, 55 participants aged 12–21 years, from seven youth groups across three regions of England took part. Each youth group took part in three interlinked focus groups exploring health and health inequalities (21 focus groups in total). Two regions were in the north of England (South Yorkshire (SY) n = 2; North East (NE) n = 3; one region was in the south of England (London (L) n = 2). All regions fell within the most deprived quintile based on 2019 English indices of multiple deprivation (IMD) in England, with closer to 1 being more deprived. At participant-level, IMD quintile ranged from 1–3. The project commenced during the Covid-19 pandemic, where the UK experienced several lock-down periods. Due to social distancing restrictions, all focus groups were conducted online except for two youth groups which were in-person (one due to digital exclusion and another recruited once restrictions lifted sufficiently). Focus groups lasted approximately 1.5 h. Further details on methodological and ethical challenges and full procedures are described elsewhere [ 23 , 24 ]. Ethical approval was granted by the School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR) Ethics Committee at the University of Sheffield and the Department of Sport and Exercise Sciences Ethics Committee at Durham University.

We adopted a purposive sampling strategy, designed to encapsulate maximum variation in perspectives and diversity [ 25 ]. Our sample was guided by the breadth and focus of the research question(s); demands placed on participants; depth of data likely to be generated; pragmatic constraints; and the analytic goals and purpose of the overall project [ 25 , 26 ]. Our final sample included young people of different sexualities, gender and ethnicity across urban and rural and coastal areas (see Table 1 ).

Youth workers invited group members to participate and shared an information video and project overview before researchers attended youth group sessions to discuss the study, build rapport and provide more detailed information sheets.These sessions were all held online during lockdown, except for two in-person groups, which were visited by the researchers. Written consent was gathered for all participants and, where under 16 years, opt-in consent from parents/guardians was also gained. Participants were asked to provide basic demographic information including postcode to calculate IMD.

Data generation

Topic guides were developed [ 23 ], giving careful consideration to activities and language used around health inequalities. These were piloted and revised with two other partner youth organisations through early public involvement and engagement work. Youth workers helped facilitate sessions and at least four and two researchers were present for online and in-person sessions, respectively (NG, NW, MC, EH, HF, CDR, VE). The same groups of researchers worked across the 21 focus groups in different sites, to ensure consistency in process. All focus groups began with introductions and a warmup activity, followed by the main activity (in smaller breakout groups) and finally close and a cool-down activity. The three interlinked focus groups held with each youth group explored: (1) children and young people's understandings of health and wellbeing as a human right (via participatory concept mapping, see Jessiman [ 27 ] for an example), (2) children and young people's perceptions of the social determinants of health (sharing ideas about contemporary news articles relevant to health inequalities) and (3) children and young people's understandings of the ways young people can take action in their local area. Focus groups were recorded via encrypted Dictaphones and transcribed verbatim, with data anonymised at the point of transcription. Contextual field notes were taken by researchers.

Thematic analysis is a well-established approach to qualitative inquiry in health-related research that allows for the depth and richness of qualitative data to guide analysis [ 28 ]. We used an inductive, reflexive thematic approach to allow for flexibility in coding [ 26 ] and the desire to make sure our analysis was adequately capturing views of the young people themselves [ 29 ]. The approach was rigorously tested through the piloting of methods, regular analysis meetings, and sense-checking sessions (with participants) to validate themes [ 30 ]. For a full description of the original reflexive thematic analysis process [ 26 , 31 ] please see Fairbrother et al. [ 23 ]. In brief, an initial coding frame was developed, with key codes and overarching themes discussed (linked to young people’s perspectives on the relationship between socioeconomic circumstances and health) and agreed upon by the wider research team. Once these core themes were established, an additional in-depth phase of reflexive analysis was undertaken (NH, PK, CDR, CS) to specifically explore PA, which had arisen continually, but not been developed as a theme, across the initial analysis. As before [ 23 ], we emphasised a creative and active approach to the analysis which followed an inherently ‘interpretative reflexive process’ ([ 26 ], p. 334). CDR, PK and NG were immersed in the data, continually reflecting upon, questioning and revisiting during the analysis process Regular analysis meetings took place to reflect and discuss and a new coding framework was developed and agreed by CDR, PK and NG, from which with themes were developed. The qualitative data management software system NVivo-12 was used to support data management.

Our analysis yielded four central themes: (1) PA experiences across spaces; (2) Resigned to a lack of inclusivity and ‘belonging’; (3) Safety first; (4) Complexities in access and accessibility. Nevertheless, themes naturally interrelate and the overarching concept of ‘PA insecurity’ emerged as a significant concern for the young people who generously shared their personal experiences with us. Here each interlinked focus group session is denoted S1, S2, S3.

Physical activity experiences across spaces

The types of spaces in which young people felt able, or not able, to be active were crucial and formed the backdrop to their PA-related experiences and interactions with others. These are contextually linked here to later themes which provide further depth on how PA might or might not be enacted by young people within those spaces.

Across sites, there were differential responses in terms of ‘things to do’ in the local area. Inner city areas had fewer green and blue spaces but presented more organised opportunities in the locality. In rural areas young people had to travel to engage in social activities. Whilst in general there were positive attitudes towards PA, in the NE and SY, there was a perceived lack of things to do where they lived that did not cost money, or require private or unreliable public transport. A salient sub-theme developed around local opportunities for activity, with one group highlighting the resulting ease with which sedentary activities displaced other activities:

Facilitator : ‘Do you prefer to play on consoles or do you prefer to go outside and run around and have exercise’? NE2, S2 : ‘If there’s nothing to do, then I will stay in the house, but if there is something to do, then I might as well just go outside’.

At first glance, this apathy perhaps represents a lack of self-efficacy, often described as an individual-level determinant of PA. However, being physically active was far from simplistic and the young people described many associated challenges including closure of local amenities such as bowling and trampoline parks, with investment instead made in a nearby seaside town. For example, they described complexities around access to the nearest swimming pool. This was free in summer but not in the immediate locality, and thus required adult facilitation to enable the young people to travel to and access the pool, resulting in a structural barrier preventing them from taking part in something which was important to them within their existing social networks: