All Things Matter

Thoughts on everyday life, society, the cosmos, and other things that matter

- Review: The End of Education by Neil Postman

- Review: Teaching as a Subversive Activity by Neil Postman and Charles Weingartner

- Review: Teaching as a Conserving Activity by Neil Postman

What It’s About

Postman is quick to acknowledge that these early narratives were not without their problems (in fact, no narratives are), and that is one reason for some of the changes in American culture and schooling since then. Partly from the gradual erosion of traditional American narratives and partly from the gradual introduction of new narratives into the culture, we are in a much different place today. The main problem Postman finds with this new place is that there are now narratives giving shape to public schooling that are in competition and incompatible with each other and with the original shared vision of liberal democracy. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that educators now seem almost entirely uninterested in discussing the reason for schooling or even acknowledging that such a thing is necessary. Consequently, schools now seem to be suffering from a severe lack of clear purpose, resulting in confusion, division, and alienation among students (not to mention mere lack of motivation).

All of this has left our public schools with no adequate god to serve – no clear or agreed-upon purpose. What, then, is to be done?

In brief, then, these five narratives are:

A Few Thoughts

OK, so, I have more than a few thoughts. Given that this is the third of Neil Postman’s books I have reviewed on this blog, it should come as no surprise that I am generally a fan of his work, and The End of Education is certainly no exception. As with the previous two books, I found this one to be insightful, accessible, and entertaining. Postman’s perspective brings, as always, a keen awareness of the place of public education within society and the critical role it plays, whether for good or ill. It also brings, especially with the present work, a willingness to raise fundamental questions that penetrate into the heart and soul of the enterprise of public school – namely in this case, “what is it all for in the first place?” Indeed, in asking and answering this question, The End of Education draws on many of the themes present in Postman’s previous works – not just those focused on education but those on childhood, technology, and media – and reads almost like a concluding synthesis, bringing this all to bear on the central question of the purpose for school.

Finally, The End of Education strikes me in some ways as the most abstract, or theoretical, of all Postman’s works on education, containing the fewest immediately applicable methods or practical steps for educators already in the classroom. Some of this no doubt stems from the nature of the central subject, which rests at the theoretical level, the underlying spirit behind the whole endeavor rather than the particular methods involved in carrying it out. It is, after all, a book about the “why” rather than the “how.” Nevertheless, in thinking back on the book as a whole, I’m left wondering seriously about its practical applicability. Assuming Postman’s right, and we want to change the spirit or purpose of something like the American public education system, just how would we go about doing that? Who makes that decision and how? Teachers? Administrators? School boards? Politicians? Would we need new legislation? Can one write into law something like purpose and have that be meaningful or enforceable? Or, would we need buy-in from participants at every level? Is such a shift realistic?

These are some significant questions to say the least, and I have some thoughts on them, but maybe I’m getting ahead of myself. Before tackling these issues, we would do well to first ask whether Postman is right about his central claims in the first place: is American public education suffering from a crisis of purpose? If so, is it bad enough to spell the end of the system? And, finally, are the solutions Postman offers truly viable? In what follows, I’ll consider each of these questions in turn.

First up, is Postman right in saying that American public education lacks a clear and unified purpose? My answer to this question is an emphatic “yes.” I have many reasons for this answer, beginning with my own experience in the public education system, first as a student, then as an educator.

As an adult, from my earliest experiences working as an educator to the present, I’ve felt strongly that there’s been something important missing from the experience of most students – namely any sense of meaningful purpose or direction for their learning. In my experience, the way this lack is almost always expressed by students is with a question or a statement along the lines of “when am I ever going to use this in real life?”

What is that question if not a cry for purpose? Yet, too often as educators we are asked to dismiss such questions as illegitimate or distractions from the official business of school, which is to teach the standards regardless of the reason for them.

To be clear, I am not saying individual teachers don’t have reasons for teaching or even that some individual students don’t have reasons for learning what they’re taught in school. I am saying, along with Postman, that many of the reasons teachers and students have in mind for the activities of school are really quite uninspired, uninspiring, or otherwise very bad reasons for public school. I am further saying, again following Postman, that even in the case that many individual educators have very good reasons for teaching what they do, there’s no agreed-upon standard reason(s) shared across the system – no clear and unified purpose or set of values on which all can agree.

For those who buy this first point, the conclusion that’s often drawn is that we’re doing school wrong, and we need to change it – to make it more practical, more relevant to everyday life, to provide more job skills, technical skills, and the like. This is, however, precisely the wrong solution, warns Postman, and it brings us to the second point in his argument – that even were schools to improve in their ability to train students in various sorts of practical skills, this would not be a good purpose for a public education system.

If not job skills, then, we might still be inclined to think of public education as a good place to introduce other practical skills, such as those in the use of technology, especially the latest technology, so as to prepare students for the future. This too, Postman warns, is fraught with problems of a similar nature. To start with, as with job skills, there are far more practical and efficient ways for both young and old to learn the use of new technologies. In fact, this is something that people tend to be able to do quite readily without the help of public schools when it suits them. Part of the reason for this is that technology has itself already come to be of such high value in American culture and society that it threatens to control almost all parts of our lives, to become an end to be served by us rather than a tool used in serving our ends – to become, in a word, a god.

This is to say, in other words, that in teaching technology, the “why” (which necessarily includes the “why not”) is even more important than the “how.” And, I would argue that the same goes for any skill set in which we might wish to train the public. As it is with job skills and technical skills, so it is with life skills, social skills, math skills, language skills, or any others; without adequate direction and purpose, in the hands of the public (especially the youth) these become worse than useless. All of this is just to say that the teaching of practical skills isn’t an adequate reason for public education – is in fact no reason at all, which brings us to the third and final point in Postman’s argument.

This is the point at which things get a little complicated, because finding answers to these questions on which we can all agree is particularly difficult in a nation like the United States – that is, a liberal-secular nation with a diverse population. Indeed, I suspect many parents of students are apt to think the above questions are none of the public schools’ business. Perhaps that’s why we’ve tended to settle on schools offering mere practical skills and left the question of purpose up to individual families – in essence, to privatize purpose. It may seem, after all, only appropriate to limit the role of a government-run educational system on our personal beliefs and values in this way. I certainly see the merits of this position, but nevertheless I think it is a mistake for several reasons.

So, I am in full agreement with Postman’s framing of this problem. But, what of the solutions he offers? Do any of those five proposed narratives serve as viable reasons for public school?

My short answer is, “Yes, I think they all do.” To be sure, there are complications to consider for each of them, and none is without its pitfalls, but ultimately I think all of them could work to restore meaning and purpose to the activities of school. I’m tempted to say we could scarcely do worse, since the question of the purpose for school seems to be something hardly anyone takes as seriously as Postman, and these may well be some of the only real offers on the table.

In what follows, rather than address each of the five solutions in turn, I’ll offer my thoughts about some merits that I think all of them share.

At this point, we would do well to pause and consider what’s at stake here. What I’m discussing goes well beyond the institutionalized public education system to encompass the whole of American society itself. In the end, this book is primarily about what makes us a society in the first place: the shared identity, beliefs, and values – the shared purpose that brings us together and keeps us together as a nation, rather than a mere collection of individuals. In short, this book is about the heart and soul of America. Both in principle and in practice, to be truly viable, any heart and soul of America must account for and represent the full diversity of Americans. This is why an orientation toward inclusivity and diversity are essential to any shared purpose. Postman’s main insight, then, lies in identifying the public education system as the best hope for instilling this in the public and indeed in recognizing this as the right and proper role of public school in the first place.

But, what a task! One might reasonably wonder these days whether such a thing is either desirable or possible. It is my belief that it is both, which is an optimistic position, to be sure. To explain my reasons for it will lead me to two additional merits shared by Postman’s proposed solutions.

Yet, liberty is a tricky thing, as is democracy. Without certain measures in place to tame and protect them, both can easily prove either self-destructive to society or end up as mere false promises. I therefore count it as an additional merit that Postman’s solutions all seem interested in providing those measures and are all in this way complementary to liberal democracy. Some more directly than others, but each in their own way pays complement to ensuring personal liberty and democratic cooperation are able to exist side-by-side. For example, consider “The American Experiment,” which takes as its main educational goal the teaching of arguments and argumentation with a view to equipping citizens to enter into arguments in a constructive, sophisticated, and critical manner. It seems to me that little could be more essential to the healthy functioning of a liberal democratic nation than the ability of its citizens to argue well (i.e. constructively). At the risk of over-explaining this connection, allow me to break it down in the following terms. If people are going to be allowed to think, speak, and act freely, they’re going to disagree; if they’re going to disagree, they need to learn how to resolve disagreements in some way that’s constructive. Perhaps if we emphasized this more in schools, we’d have a citizenry better able to handle the responsibilities that liberty and democracy require. Similarly, if we placed greater emphasis on our interconnectedness, our own fallibility, an appreciation of diversity, and an awareness of the role of language in our understanding, we’d have a citizenry much more well equipped to navigate the many challenges that inevitably arise in a liberal-secular democratic nation such as ours, not to mention in the wider world. That’s the education our citizens need, and that’s what Postman’s solutions offer.

So, maybe this all sounds good in theory, but how realistic is it? Can we really hope to use something like our public school system to accomplish all this? To create a citizenry with shared value and purpose, which can disagree, argue, compromise, and cooperate – especially with such a large and diverse population?

That is a key question, and one which I can’t answer definitively. I can say, first of all, that we’ll never know for sure unless we try. Secondly, in my estimation, if we’re going to try, Postman’s solutions or something similar to them would probably be about as good a chance as any we’ll get. This brings me to the final merit shared by all five solutions – that they are balanced and realistic enough to work in the United States.

So, to recap, I think Postman is right that American public education is experiencing a crisis of purpose, and I think his proposed solutions to this crisis are all quite viable based on several merits they all seem to share. They are all largely secular, inclusive, supportive of liberal democracy, and balanced enough to be realistic in America. I believe we would do well to adopt any or all of them.

There remains, however, one set of questions still to answer: if we want to adopt these principles, just how can we go about doing that? Who do we need to convince to actually make this change, and how would it be made?

In thinking about this question, I must first of all admit that I can think of no simple or easy answer. As it stands today, the American public education system is large; it’s complex, and it’s dynamic, with many moving parts and many people that make decisions for it at various levels. It is also what one might call decentralized. Some significant policies and decisions come top-down from the federal level, but many more are made at the state and local levels. Local school boards, district and building administrators, and individual teachers all wield a significant amount of power when it comes to what’s actually being taught in the classroom. Ideally, then, the answer to the question of who to convince is “everyone.” However, since such an ideal goal is rather too grand to be of much help at this point, I’ll offer just a couple more thoughts on where we might start in making these changes.

In the end, it may well be that none of this will make much difference. There are many forces in society working against giving public education a transcendent purpose, and our schools may already be on their way to a much less noble fate.

I hope this is not the case, and I remain optimistic that it won’t be – an optimism I’ve derived in no small part from Neil Postman. No author has been more inspiring to me in this regard, and no book has better encapsulated my own relationship and attitude toward our schools than The End of Education . Increasingly, the kind of education it envisions is the only kind of which I find myself wanting to be a part. In any case, it’s the kind I believe our country truly needs.

The Bottom Line

All of these words could apply equally well to The End of Education . The only thing I’ll add is that here, more than in any of his other works, Postman cuts straight to the heart of what’s at stake in American public education – namely the heart of the American public. For this reason, despite some concerns regarding clarity and detail, I highly recommend this book to anyone with a stake in American society, but especially to my fellow educators. May we fully realize our purpose and live up to it . . . before it’s too late.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

[ + ]

| 1 | Neil Postman, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1995). |

|---|---|

| 2 | 4. |

| 3 | See generally Chapter 1: “The Necessity of Gods,” 3-18. |

| 4 | As Postman himself notes, the term “myth” brings with it a significant amount of semantic baggage and can often be taken to mean a story that is false, or dubious at best. However, the sense in which he means it here is much closer to the way scholars of culture and religion use the term, to denote a narrative that holds meaning for people (regardless of its veracity) and through which they can readily interpret the world and understand their place in it. See p.153. |

| 5 | 6. |

| 6 | As he puts it, “My intention here is neither to bury nor to praise any gods, but to claim that we cannot do without them, that whatever else we may call ourselves, we are the god-making species. Our genius lies in our capacity to make meaning through the creation of narratives that give point to our labors, exalt our history, elucidate the present, and give direction to our future,” 6-7. |

| 7 | 21. |

| 8 | Postman credits Gunnar Myrdal with using this term to encapsulate the “system of general ideals” of America at the time that he was writing. See p.13. |

| 9 | Postman mentions in this context America’s actions specifically in “Vietnam . . . Granada, Panama, and Kuwait,” 22. |

| 10 | This may well be an understatement given the political movements and arguments over race and equality that have erupted recently in the early 21st century, and especially in the summer of 2020. To name just one example, consider the Black Lives Matter movement and organization, which over the last eight years has drawn attention (and controversy) to issues of racial equality in America and beyond. For more related to this issue, see note 44 below. |

| 11 | This is not to say that faith in these old ideals is completely lost, and this is part of Postman’s hope in writing this book. In discussing the now undermined idea of America as a beacon of morality, he reminds us, “Through all the turmoil, it is well to keep in mind that a wounded god is different than a dead one. We may yet have need of this one,” 22. |

| 12 | 27. |

| 13 | 30. |

| 14 | I find his words on this last point worth quoting: “Any education that is mainly economic utility is far too limited to be useful, and, in any case, so diminishes the world that it mocks one’s humanity. At the very least, it diminishes the idea of what a good learner is,” 31. |

| 15 | Postman for his part clarifies that “no argument is being made against the acknowledgement of cultural differences among students. I am using [‘multiculturalism’] to denote a narrative that makes cultural diversity an exclusive preoccupation,” 51. He also distinguishes “multiculturalism” from “cultural pluralism” – the acknowledgment and celebration of various ethnic and cultural identities as a part of a shared American Identity, 50. |

| 16 | 51. |

| 17 | 62. |

| 18 | 61. |

| 19 | 61-2. |

| 20 | 91. |

| 21 | See Chapter 5, 93-113. |

| 22 | See Chapter 6, 114-128. |

| 23 | See Chapter 7, 129-142. |

| 24 | See Chapter 8, 143-71. |

| 25 | See Chapter 9, 172-93. |

| 26 | In Postman’s words, this organizational division can be thought of as a division between “the doctrine” in Part 1 and “the commentary” in Part 2, See p. 91. |

| 27 | Having grown up in a Jewish household and attending both a “Jewish” school and a public school, Postman brings his own childhood experience to bear on questions of culture, ethnicity, and the role of school regarding such things. See especially p.14-16. |

| 28 | In a brief epilogue to the book, Postman states outright that he himself is “not terribly confident that any of [his solutions] will actually work,” 195. The reason for this rather bleak view is that American culture seems to be moving away from some of the basic assumptions necessary to maintain and invest in public school. Specifically, many are now questioning the ideas that “school” is necessary or important (see note 42 below), that a cohesive “public” with shared values is tenable in America (see paragraph 33 and following below), and that “childhood” still exists in any meaningful sense. (Postman has written an entire book on this last point. See Neil Postman, (New York: Delacorte Press, 1982).) Ending the book on such a pessimistic note makes the whole thing feel like something of a last ditch effort, but it is at least a worthy effort in my estimation, and one made “in good faith,” 196. |

| 29 | As I recall, one of the banners hanging in the halls of my high school read, “Believe and you can Achieve.” This slogan rang hollow to me then, and it does even more so now. “Believe in order to achieve , and ?” one might well ask, but these questions were never addressed, at least not clearly and definitively or in a way that connected them to the actual activities of school. Since then, I’ve come across numerous similarly vacuous supposedly motivational slogans, posters, etc.. In my experience, this appears to be par for the course. |

| 30 | For anyone unfamiliar, the reference I’m making is to “I Can Statements,” or “Can-do Statements,” which are a tool sometimes used by contemporary educators to aid in organizing and expressing clear learning objectives for students. My point here is that these serve as one indicator that current trends in education emphasize the development of skills. I have no major objection to the use of such statements, though I do think the full educational impact of them is worth analyzing closely. What do we teach students about learning when we encourage them to always think of it as something they should be able to act on somehow? Is anything worth learning that bids us act? Or, that in some way? |

| 31 | If you’ve been out of school for a while, you may not be familiar with Common Core standards, which were developed beginning in 2008 and are now adopted by 41 US states and some additional territories. The express reason that these standards focus on Math and English specifically is “because they are areas upon which students build skill sets that are used in other subjects. Students must learn to read, write, speak, listen, and use language effectively in a variety of content areas, so the standards specify the literacy skills and understandings required for college and career readiness in multiple disciplines,” Common Core State Standards Initiative, “Frequently Asked Questions,” Common Core State Standards Initiative: Preparing America’s Students for College & Career, accessed January 8, 2022, . Note the emphasis placed on “skills” in this explanation. |

| 32 | The argument that follows is partly drawn from Postman, partly my own. Though Postman doesn’t frame an argument exactly this way, all three of the main points can be found in . |

| 33 | See paragraph 7 of the summary above. |

| 34 | In making this claim, I’m venturing into territory that is quite a bit beyond my personal familiarity or expertise. I certainly don’t mean to overstate the case, and I welcome any evidence that could correct me on this point if I’m mistaken. That being said, here are a few reasons why I am willing to make the claim despite my reservations. First, Postman himself makes a strong claim along these lines early on in the book: “There is little evidence (that is to say, none) that the productivity of a nation’s economy is related to the quality of its schooling,” 28. In support of this statement, he cites “the work of Henry Levin of Stanford University” (though that’s as specific as he gets), 28, note 4. He also points out the difficulties with discovering anything conclusive by comparing scores in math and reading between nations with very different cultures and values, and the fact that even when these comparisons have been made, there is no consistent correlation between better test scores in these subjects and more productive national economies. See p.28-9. In thinking about this myself, I imagine it may be possible to show some statistical correlation between school grades or test scores on the one hand and employment, job performance, or salary on the other, but as always, it’s important to remember that correlation does not necessarily mean causation. The proper conclusion to draw might rather be that the traits that make good students – conscientiousness, attentiveness, organization, etc. – also tend to make good employees. Certainly, something like a high school diploma or any other sort of credential provides very clear economic benefits to someone seeking employment in our economy, so in that sense at least, school performance could be said to set students up for more economic opportunities. But, that is not what’s at issue here. The question is whether the actual of public education provides students with skills useful for life and work after graduation – whether many of the skills acquired in school are directly transferable to the real world. I tend to think not. For more on this, continue reading. |

| 35 | 32-3. To give a bit more explanation about what’s included in a “decent education,” Postman offers as a starting point “the making of adaptable, curious, open, questioning people,” which he says “has nothing to do with vocational training and everything to do with humanistic and scientific studies,” 32. I quite agree. |

| 36 | 50. |

| 37 | There are countless examples of this throughout history. Consider the environmental effects of the use of internal combustion engines, of plastic wastes, or of industrial scale harvesting. Then again, consider nuclear technologies and the numerous disasters they’ve caused, some more intentional than others. Perhaps no example is more salient to us today than the internet and its numerous unintended consequences, especially for young people, some of which we’re still just beginning to realize. Whether or not any particular technological development is ultimately a good thing for the world is not for me to judge here (and my judgement wouldn’t make much difference anyway). The point is that technology always brings profound and far-reaching consequences, some bad, some good, and is for this reason is not something to be taken lightly, least of all treated as an end in itself. |

| 38 | 3, 4, 27. Postman uses this term several times to contrast, as I take it, the sort of deeper reasons he’s interested in from more superficial reasons, which often boil down to methods or techniques, means as opposed to ends. |

| 39 | It’s worth mentioning here that the solution is also not as simple as cultivating empathy among students. I don’t deny the benefit and importance of this, but it can’t be the whole answer. Empathy – like all sentiments – has its limits. Without shared beliefs or values behind it, it can be shallow and brittle and will quickly fall apart in the face of true conflict. It’s not that beliefs matter more than feelings (a debatable point), but that beliefs and feelings are always intertwined. To try and artificially promote empathy without addressing serious differences in beliefs, then, will first of all be met with resistance from some students (and parents) and secondly, even if successful in the short term, will poorly prepare them for life as adults when the stakes become much higher. Thus, the same problem is applicable here. Even if we agree that empathy is something good for the public to have, we must ask why. To what end should we promote this? What is the reason for it? If someone doesn’t want this, why should they buy into it? |

| 40 | See paragraph 4 of the summary above. |

| 41 | This point strikes me as at once both blaringly obvious and quite difficult to demonstrate easily. I suppose it rests partly on the notion that we learn just as much from silence as from sound and partly on our natural ability to make inferences about why something might be important or valuable, to fill in the cracks of our education, so to speak. The result is that children learn, from an alarmingly young age, all sorts of things about the reason for school, whether or not anyone ever broaches the topic with them explicitly. I’ve personally had school-children as young as second grade explain to me in no uncertain terms that the reason for school is for individuals to get jobs and make money, plain and simple. I can’t resist adding here that I explored this connection (very briefly) in a presentation I gave through PechaKucha Kalamazoo in the Summer of 2019. See Joel Sanford, , PechaKucha, August 13, 2019, video, 6:50, . |

| 42 | Apparently, this has been a topic of serious discussion at least since the time Postman was writing in 1995. He mentions several authors predicting and/or advocating such things as public education’s “conversion to privatized schooling . . . its subordination to individually controlled technology [and its being] taken over by corporations . . . and operated entirely on principles associated with a market economy,” 61. Whatever might end up happening to public schools, it appears there has been a growing sentiment in some circles, at least for the last 20 years or so, that they are somehow obsolete – “nineteenth century inventions that have outlived their usefulness,” 195. In our own day, this same sentiment appears to be alive and well, not least among school-children, who are all too willing to be convinced of theories that tell them school has no real point (and certainly they’re partly correct). Many adults agree as well, and examples of this line of thinking abound for anyone who is paying attention to what people are saying about school in the wider culture, especially but not exclusively on the internet. For one particularly relevant example, consider this video by Prince Ea (to which, it’s worth noting, I was first introduced by my own class of seventh grade students): Prince Ea, , YouTube, September 3, 2018, video, 8:13, . |

| 43 | 18. |

| 44 | It would be hard to find a better example of the controversy over race and education than that surrounding the 1619 Project. This project, which started with a special issue of in August of 2019, “illuminates the legacy of slavery in the contemporary United States, and highlights the contributions of Black Americans to every aspect of American society,” Pulitzer Center, “About The 1619 Project,” The 1619 Project: Education Materials Collection, accessed January 16, 2022, . It has grown through partnerships to include a host of educational resources, many of which are made available for free. The “1619” in the title refers to the year in which a ship bearing African slaves arrived in Virginia, and the goal of the project is thus to “reframe American History by considering what it would mean to regard 1619 as our nation’s birth year,” Jake Silversteen, “Editor’s Note,” , August 18, 2019, 4-5, accessed January 16, 2022, url: . Perhaps unsurprisingly, the project has met with more than a small amount of criticism from some who see it as revisionist history or otherwise wrong or destructive to traditional American values. Several organizations coming from this perspective have titles including “1776,” apparently as a way to emphasize that year – not 1619 – as key to the start of American history. There are the , , and to name three such organizations. In each of these cases, education is a central focus, with curriculum and educational resources made available for free. So, here we clearly have a deep controversy with at least two oppositional parties each advocating for their perspective as the best one to be offered to school-children. |

| 45 | The responses from educators certainly vary, so at risk of overgeneralizing, what I want to suggest is that educators are sometimes too quick to respond at all to these arguments, to come down on one side or the other of controversial issues. In considering again the example of The 1619 Project (see note 44 above), we might be tempted to either accept the goals of The 1619 Project and implement them in the classroom or to accept the goals of the opposition view and implement them instead. However, my hope is that most educators wouldn’t see it as their role to ally themselves completely with either side of this controversy, but rather to teach the controversy itself – to recognize that 1619 and 1776 are both significant years in American history but that American history in fact begins with neither of these dates, and that all history is perspectival and open to reinterpretation and revision. This is essentially to say that our role should be to teach students to think, not to think, and I believe this approach is the sort of thing Postman has in mind with “The American Experiment.” |

| 46 | To put this all yet another way, what I’m arguing is that – as lofty as this goal might sound – public education should partisan politics, not in the sense that it avoids political issues altogether (this would be counterproductive, not to mention impossible), but in the sense that it neither endorses nor excludes any political view held by the public. I recognize the extreme difficulty of this and some of the complications that inevitably will arise, but I also believe that if public education doesn’t do this – if it doesn’t at least attempt it – then it’s not public education at all; it’s mere partisan education, and it’s no wonder certain parties are alienated by it. |

| 47 | I hope I’m being hyperbolic here, but I’m not so sure I am. I recently came across the following book by Mary Rice Hasson and Theresa Farnan, the title of which speaks for itself: (Washington: Regnery Gateway, 2018). The authors write from a self-described conservative perspective about some of the ideas and values becoming prevalent in American public schools which they find highly objectionable, and they ultimately call on fellow conservatives to remove their children from the system. Who’s to say how many will answer this call? Yet, the fact that this call was made at all, that people are seriously advocating to large numbers of Americans that they abandon the system altogether, is but one more example of the widespread distrust and alienation some feel toward the schools. |

| 48 | I have already mentioned those who have been calling for an end of one sort or another to traditional public schooling for the last two decades (see note 42 above) and those now calling for parents to simply abandon the public schools (see note 47 above). To this I’ll add that technology now makes it possible for more and more students to attend school remotely through distance learning and online educational programs. While such programs vary widely in terms of general format and the amount of live instruction and class interaction involved, the overall trend seems to be that more and more is becoming automated and individualized. This means that for many students, school is starting to look increasingly like a series of online training modules. If this doesn’t spell the end of education as we know it, I’m not sure what does. |

| 49 | Having spent some time studying a fair number of different religious traditions, I know better than to make universal statements about beliefs or worldviews. There are just too many out there, and counterexamples to any such universal statement are bound to arise. It is as true in public education as it is in life generally: You can’t please everyone. Thankfully, this has never been the goal or standard. |

| 50 | A possible exception might be solution number 4, “The Law of Diversity,” to the extent that this “law” is meant to be held as an absolute axiom, meaning that and diversity brings excellence and vitality. As Postman acknowledges, some might object that too much diversity sometimes leads to a relativizing of values or standards. He argues against this on the grounds that our shared humanity means we ultimately recognize the good in diverse perspectives, even as we can acknowledge differences. Thus, he suggests, “Diversity does not mean the disintegration of standards” . . . “It is an argument for the growth and malleability of standards,” 80. However, I’m sure there are those for whom growth and malleability are little better than disintegration when it comes to certain standards they’d like to see remain static. In response, I would first of all argue that any standard so important as to remain unchanged in this way I would hope should be able to stand up to outside challenges. In any case, those of this persuasion have little say in the matter. The fact is that we a diverse nation, and our diversity raise challenges to monolithic standards of excellence. The question is how we choose to respond to these challenges – by embracing them or resisting them. For more on this, continue reading. |

| 51 | I’m referring above all to the events of January 6th, 2021, during which a group of about 2,000 people invaded the capitol complex in Washington, D.C. and obstructed part of the official process to finalize the presidential election. However one feels about these events, they certainly indicate a blatant distrust in the democratic process on the part of this group. But, as I see it, this is but one symptom of a long-standing deeper problem for our nation. I think it’s accurate to say there’s been a deterioration of trust among Americans generally in many parts of the democratic process, the government, and their fellow citizens for quite some time. In my experience, it’s become something of a cliche to say that “we’re as divided as ever before,” and maybe we are. Divisions have always been a part of the package, and arguing over our divisions a part of the process. What’s concerning now is that we’re starting to see what happens when arguments cease. |

| 52 | As unfashionable as it may still be to raise questions such as these explicitly, I think there are numerous reasons they are worth raising, and I get the distinct impression that people are actively raising these questions anyway, if not through their words, through their actions and attitudes toward their fellow citizens. It certainly wouldn’t be the first time. |

| 53 | See p.62. |

| 54 | Of course, ideals rarely if ever square with reality. It’s important to recognize that any education system we come up with will be imperfect. The important thing here is to have the right goals in mind to strive toward. |

| 55 | Some of the values I have in mind here are nationalism, ethnocentrism, traditionalism, social Darwinism, and individualism, not to mention racism and simple self-centeredness. |

| 56 | I would include here also paraprofessionals, teacher’s aids, counselors, etc. – basically anyone who has direct contact with students and/or is involved in providing instruction. All are in a position to make this change. |

| 57 | I happen to know teachers do this because they already doing it. It’s no secret that educators do much more than teach the required federal, state, and local standards. This seems inevitable given all the time they spend with students, and I’m not sure I’d have it any other way. But, it’s also an awesome responsibility, the implications of which ought to be taken very seriously. I’ve already mentioned that all education is value-laden (see paragraph 22 above) and that teachers are sometimes very quick to adopt and proliferate certain viewpoints on issues they deem important (see note 45 above). It may or may not surprise some readers to know that there is an awful lot of discussion among public educators about what’s “really important” for students to learn and that some of the things deemed important by certain parties have little if anything to do with what’s mandated by the state and federal governments. In many ways, when it comes right down to it, each individual teacher gets to decide what’s most important to them, which is an extraordinary amount of freedom and power. This is, I should add, a part of the crisis of purpose that’s a central concern of the present work – that is, there’s no clear unified purpose to the system; rather, everyone seems to be choosing one for themselves. So, it is with some reservations that I’m suggesting – since we’re picking and choosing already at this point – teachers should choose for their own purpose one or more of those offered by Postman or something close to them, in the short term at least. |

| 58 | Because so much of his book focuses on the big picture, many of Postman’s practical suggestions involve large-scale, systemic changes that would require political or administrative buy-in, but some of them can be implemented immediately by individual teachers in their classrooms, with little or no outside changes. Some of my favorite of these ideas include students being asked and encouraged to point out and correct a teacher’s errors (p. 117-18), students being asked to consider questions about the effects of various communications media and technology (p. 141, 190), students being taught about the origins of words in the English language (p. 146-47), and, of course, students being introduced to the study of various religious traditions (p. 151-57). |

| 59 | It has been illuminating to me to do just a bit of research into mission statements of school districts. Too often in my view, they rely on buzzwords that lend themselves to extreme vagueness (e.g. “success,” “achievement,” “pursuing dreams,” “excellence,” “making a better world,” etc.). I don’t mean to attach too much importance to this, but I do wonder whether we’re sometimes simply being intentionally vague in order to gain approval from a wide constituency. After all, who would argue that “success” isn’t a good thing? The problem, of course, is that different people define success quite differently. |

| 60 | “ ,” “The Bottom Line.” |

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Enter the characters you see below

Sorry, we just need to make sure you're not a robot. For best results, please make sure your browser is accepting cookies.

Type the characters you see in this image:

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

The End of Education: Redefining the Value of School

Learn about this topic in these articles:, discussed in biography.

In The End of Education: Redefining the Value of School (1995), he rejected the growing emphasis on economic utility, training for consumership, and faith in technology that characterize modern education. He held that the purpose of education is to forge a coherent unified culture out of…

Book Notes, Summary and Review: The End of Education by Neil Postman

Summary notes.

What's the point of going to school?

I hear that very often from my friends. Well, everyone has their own personal views on this. And so does American educator Neil Postman.

In The End of Education , Neil shares his views on the American public education landscape in the 20th century. Throughout the book, he answers the introductory question of "Why we need to go to schools?". He also explores other important questions, such as "What's the purpose of school?" and "How can we cultivate a better schooling experience for future generations?".

About the Book Title

Please indulge me for a moment as I go slightly off tangent here.

I found it extremely fascinating how the title The End of Education could be interpreted in two ways. And even so, both interpretations of the book still stand:

- One possible interpretation is it's a declaration that education is finished . That unstructured education may not be as beneficial as schooling.

- The other interpretation is it's a question on the end-goal of education. What we as a society should include in a quality education?

In the book, Neil touches on both issues. In regards to the first point, he explores the differences between education and schooling in the outset of the book. But of course, it's important to note that schooling and education are not mutually exclusive activities; both activities can overlap each other.

The second point forms the bulk of his book. He spends a lot of time discussing the objectives of schools and the narratives they propagate. I found that Neil offered many valuable insights and suggestions on how schools could remodel their teaching philosophy, such that more students benefit from the education system. I'll write more about this in next few sections.

Alright now, let's begin with the book summary.

Structure of Summary

The End of Education is organized into two sections. This book summary will follow the book's structure (excluding Part I Chapter 4):

- The Necessity of Gods

- Some Gods That Fail

- Some New Gods That Fail

- Gods That May Serve

- The Spaceship Earth

- The Fallen Angel

- The American Experiment

- The Law of Diversity

- The World Weavers/The World Makers

Summary of Part I

1. the necessity of gods.

Schooling addresses two main problems: engineering problems (learn how to do something) and metaphysical problems (what to learn).

A serious problem with the public education in the United States of America, and also in other parts of the world, is that schooling fails to address the latter. Most of the conversation about education is now centered around the former. Everyone's discussing and inventing new teaching methods, but few are asking what should schools be teaching.

Metaphysical objectives are vital to our education, because they are the forces that stop us from feeling too demoralized, bored or distracted to learn.

In Nietzsche's words:

He who has a why to live can bear with almost any how.

Throughout the book, Neil makes references to these metaphysical objectives as gods (with a small g). These gods are, in Neil's view, narratives that can "give point to our labors, exalt our history, elucidate the present, and give direction to our future".

In other words, Neil is proposing the need for schools to define a clearer purpose for its students to be educated. The mission that schools pledge to model their curriculum after should be pragmatic, illuminating, inspiring, enduring and encompassing.

Without a strong and compelling narrative, students feel disillusioned, alienated and feel directionless in their lives. Isn't this a shared feeling among many students these days as well?

2. Some Gods That Fail

Gods (with a small g) aren't infallible. In the twentieth century alone, many gods have fallen: the god of communism, the god of fascism and the god of Nazism.

The same applies for gods in education.

Two gods are currently reigning over the world of education that are failing:

- God of Economic Utility: The god of Economic Utility promises the young that as long as you score well on exams, you'll be rewarded with a well-paying job. Its entire narrative is predicated on the idea that the purpose of schooling is to prepare students to be financially independent. Any other activity is seen to be irrelevant and a waste of time.

- God of Consumership: The fundamental principle of this narrative is that: you're what you accumulate. In other words: the more toys you die with, the more you win in life.

Many students tend to find the god of Economic Utility too dry and uninspiring. Young people have too much pent-up creativity, curiosity and vitality to be attracted to a narrative that reduces their life into a single dimension.

And this is where the sibling of the god of Economic Utility — the god of Consumership — comes in.

Many of us have been conditioned into subscribing to a consumerist lifestyle since young. Just in one day alone, the typical American is exposed to 4,000 to 10,000 advertisements . What this means is that media advertisements is one of the most substantial sources of values imparted to the young.

In order to subscribe to the god of Consumership, one has to earn more money. As such, people start to subscribe to the religion of Economic Utility, in order to fuel their consumerist lifestyle.

The gods of Economic Utility and of Consumership work closely together. Collectively, they develop a grand narrative that persuades us into thinking that our identity is centered around our jobs and material possessions.

On the surface, both narratives combined seem alluring to undiscerning youths. But deep down within, they recognize how unfulfilling and uninspiring such narratives are.

3. Some New Gods That Fail

Another rising contender in the world of education is: the god of Technology.

Educators often fall prey to the god of Technology, more often than students. Teachers tend to focus more on the means of education than its ends. Thus, they may utilize technology as a way of supplying more information to their students.

But more information is the last thing these students need.

What students truly need is an improved narrative that gives them a reason to learn. Technology should help educators to forward a better conceived narrative in schools, than to perpetuate and to aggravate the current failing narrative.

Summary of Part II

1. the spaceship earth.

Local problems have a global impact. What Neil suggests, therefore, is that we need to confront each problem collectively as a global community, rather than passing it on to the local community.

Schools, in Neil's view, need to cultivate interdependence and cooperation amongst their students. We could even use the youthful vigor as an asset to the students' schooling experience, by encouraging them to partake in value-adding community activities.

2. The Fallen Angel

I make mistakes.

You also make mistakes.

Everyone has made and will continue to make mistakes. Even if we think we know something, what we know may be wrong. And even if it's right, it's limited in its scope and its applicability.

All of us, including our teachers, are fallible. But we can learn to correct our mistakes and redeem ourselves. We ought to accept that we are an error-prone species and put down our hubris and dogmatism.

A central problem with how we're taught and raised is that: we quickly justify and defend what we believe. We don't consider the possibility that our beliefs are imperfect and may be improved upon with other people's input.

Rather than think of teachers as truth tellers whose role is to make students smarter, wouldn't a better definition of their role be to make students less dumb?

3. The American Experiment

Discourse is an effective means to resolve conflict.

When people stop arguing with one another, bloodshed will likely occur. Just look at the American Civil War or any other wars. Large-scale suffering will arise if we don't provide a safe platform to facilitate and to resolve these conflicts.

By teaching students to argue, we teach students to convey their points of view and to resolve conflict through a more civilized means. In the process, we also invite our youths to discover what questions are worth arguing about.

4. The Law of Diversity

Opening ourselves to new ideas, new knowledge and new cultures, we can learn how differences contribute to increased creativity, vitality and unity.

Diversity, however, doesn't equate to a complete lack of standards or irresponsible relativism. Instead, it's an advocate of the growth and malleability of standards that transcends the differences of gender, religion or any other social constructs.

Cultural diversity can be expressed through a myriad of ways: language, religion, custom, art and artifacts. These are possible means in which our youths can learn how to become more open and accepting of new ideas, new standards and new ways of living.

5. The World Weavers/The World Makers

Language is an organ of perception.

Through language, we see the world as one thing or another.

We can even create new worlds using language. Languages not only construct concepts about the events and things in our world, but also tell us the types of concepts we could and should construct.

By learning the story of language, as well as how language shape our senses of perception, our youths can create more powerful, durable and inspiring narratives for their schooling journey.

Wrapping Up

Books on education have always sparked an interest in me. Even then, I would've taken days to plough through such books.

But not in the case of Neil Postman's The End of Education — I devoured the whole book in less than a day.

Reading this book was such a pleasurable yet enriching experience. I thoroughly enjoyed reading Part I of the book, in which Neil outlines some of the uninspiring narratives that our schools are still propagating today. Mind you, this book was published in 1995. That's 27 years ago.

As a former teacher and soon-to-be University student, this book shed light on many issues I'm personally intrigued about: the global education landscape, the purpose of schooling, how our schools can provide a better education for students and so on.

The End of Education is a must-read for anyone who is even vaguely interested in education-related issues.

The End of Education: Redefining the Value of School

Neil postman. knopf publishing group, $25 (209pp) isbn 978-0-679-43006-3.

Reviewed on: 09/04/1995

Genre: Nonfiction

Open Ebook - 118 pages - 978-0-307-79720-9

Paperback - 224 pages - 978-0-679-75031-4

- Apple Books

- Barnes & Noble

More By and About this Author chevron_right

The End of Education: Redefining the Value of School

An educational technologist in the private sector for the last fifteen years. Her research interest is the public perception of the intersection of pedagogy and technology.

- Page/Article: 64-70

- DOI: 10.21061/jte.v8i1.a.7

- Published on 22 Sep 1996

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The End of Education is a book by Neil Postman about public education in the United States.The use of the word "end" in the title has two meanings: primarily, as a synonym for "purpose", but also as a prediction about the future of public schools if they do not successfully identify and communicate a convincing purpose for their existence within human culture.

The End of Education is a provocatively misleading title--what he really means is "The Larger Purpose of Education," as in "the means and the ends." Basically, Postman is saying that the current narrative that's supposed to give meaning to schooling--which he calls "the god of Economic Utility"--is neither inspiring nor believable nor powerful ...

In The End of Education Postman makes the case that without a clear and unified purpose behind it, public education in America is in danger of becoming obsolete and useless. 1 The "end" in the title is thus a double entendre, referring in one sense to the possible demise, or termination, of traditional public schooling and in another sense ...

The End of Education. fails in its attempt to provide alternative strategies to revamp the public school system today. However, it does offer keen criti-cism on the current values and ideals that shape education. It is important for schools, even Catholic ones, to avoid worshipping the gods of Economics,

Postman chose this title to purposely have a double meaning: that we'll have an end to successful public education if it doesn't have a meaningful end, or purpose, to it. In the first part of the book, he suggests some purposes that don't work: consumership, economic utility, technology, multiculturalism.

The End of Education: Redefining the Value of School. In this brilliantly challenging response to the education crisis, Neil Postman returns to the subject that established his reputation as one of our most insightful social critics. Starting from his belief that schooling is now too often a trivial pursuit, a mechanical exercise, he argues ...

About The End of Education. Postman suggests that the current crisis in our educational system derives from its failure to supply students with a translucent, unifying "narrative" like those that inspired earlier generations. Instead, today's schools promote the false "gods" of economic utility, consumerism, or ethnic separatism and resentment.

978--385-29009-8. $17.00 US. Paperback. Delta. Jul 15, 1971. Postman suggests that the current crisis in our educational system derives from its failure to supply students with a translucent, unifying "narrative" like those that inspired earlier generations. Instead, today's schools promote the false "gods" of economic utility, consumerism, or ...

Postman also gives clear suggestions for how the system of education and the approach to teaching can be modified in order to turn around the imminent end of education and make it into a positive constructive force for the future. There are a lot of crossovers with "Teaching as a Subversive Activity" which Postman co-authored.

The End of Education: Redefining the Value of School. Neil Postman. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, Oct 29, 1996 - Education - 224 pages. Postman suggests that the current crisis in our educational system derives from its failure to supply students with a translucent, unifying "narrative" like those that inspired earlier generations.

In Neil Postman. In The End of Education: Redefining the Value of School (1995), he rejected the growing emphasis on economic utility, training for consumership, and faith in technology that characterize modern education. He held that the purpose of education is to forge a coherent unified culture out of…. Read More.

As a former teacher and student, this book shed light on many issues I'm personally intrigued about: the global education landscape, the purpose of schooling, how our schools can provide a better education for students, and much more. The End of Education is a must-read for anyone who is even vaguely interested in education-related issues.

The End of Education: Redefining the Value of School. Postman, Neil. Based on the belief that schooling is now too often a trivial pursuit or a mechanical exercise, this book argues that the inherent value and substance of learning has been lost and needs to be restored. The book begins by portraying the American education of an earlier part of ...

The End of Education: Redefining the Value of School. Neil Postman. Knopf Publishing Group, $25 (209pp) ISBN 978--679-43006-3.

The End of Education: Redefining the Value of School. Neil Postman. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, Oct 29, 1996 - Education - 224 pages. Postman suggests that the current crisis in our educational system derives from its failure to supply students with a translucent, unifying "narrative" like those that inspired earlier generations.

The end of education : redefining the value of school by Postman, Neil. ... In this comprehensive response to the education crisis, the author of Teaching as a Subversive Activity returns to the subject that established his reputation as one of our most insightful social critics. Postman presents useful models with which schools can restore a ...

The End of Education: Redefining the Value of School . Alfred A. Knopf, $22.00 (hardback), 209 pp. (ISBN -679-43006-7) Reviewed by Ellen Rose. I have before me a copy of Neil Postman's The End of Education. My original intent was to review this, Postman's most recent publication, in isolation, referring only superficially, if at all, to his ...

The story says that experimenting and arguing is what Americans do. It does not matter if you are unhappy about the way things are. Everybody is unhappy about the way things are. We experiment to ...

But the end of education is just as duplicitous. Like the associated notion of "an educated public," education "is a ghost that cannot be excised" (MacIntyre, 1987, p. 34). In short, only those who are already conditioned by the idea of education, those with a taste for such falseness, can fear its end. The end of education is a

The other is the metaphysical aspect: the underlying purpose or mission — the "end" — of education. Postman believes that the debate over the future of America's schools focuses too much on engineering concerns — curricula, teaching methods, standardized testing, the role of technology, etc. — while very little attention is paid to the ...

gress entitled The End of Education: Destroying the Core Curriculum. These all too brief prefatorial remarks are intended to provide the con-text in which I examine the rhetoric of the "Harvard Core Curriculum Report" in my text. More specifically, they are meant to situate the "Report"-and the various core curricula it has encouraged tradi-

The End of Education. 'The End of Education' is a book by Neil Postman about public education in America. The use of the word "end" in the title has two meanings: primarily, as a synonym for "purpose", but also as a prediction about the future of public schools if they do not successfully identify and communicate a convincing purpose for their ...

What Is the End Goal of Education? In the 1913 Elementary Course of Study, published by the State of Kentucky, the introduction to the second chapter states that "The highest function of the school is character building.". The chapter then goes on to detail how teachers should go about forming this character in their young elementary school ...

Parents of High School Students Can Access Their Child's STAAR EOC Scores Beginning Today, Including Detailed Information and Resources AUSTIN, TX - June 7, 2024 --The Texas Education Agency (TEA) today released the spring 2024 State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness (STAAR®) End-of-Course (EOC) assessment results. These results, a key measure of student performance and ...

Millions of borrowers will see their monthly student loan payments reduced starting in July, thanks to one of the Biden administration's biggest changes to the federal student loan system to date.

In this two-day conference utilizing End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC) modules and materials, interdisciplinary speakers will share about the latest in pediatric and perinatal palliative care with evidence-based education. Learners will explore the role of the healthcare team in providing quality pediatric palliative care, identify the need for collaboration among team members ...

A new electoral divide has emerged in America. This divide is not rooted in race, geography, age or education. Instead, it is engagement in democracy itself. Scroll to continue Here is a ...

of Education. Building Technology Foundations In order to more effectively manage our technology, serve our patrons, and prepare for innovation, we have continued to upgrade our network infrastructure and technology. By the end of this fiscal year, we will have a network that we can manage and is redundant, and new computers for patrons and staff.

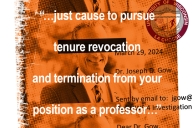

A nationally prominent conservative lawyer, hired to defend the state's Stop WOKE Act, asserted that what public university professors say in classrooms "is the government's speech." The national implications for academic freedom could be dire. In 2022, Florida's Republican state legislators passed the Stop WOKE Act, championed and signed by GOP governor Ron DeSantis.

A program to end poverty in Austin, Texas, could hold valuable lessons for Boston, where Black and Latino students have yet to experience Boston Public Schools as an engine of upward mobility