The Research Gap (Literature Gap)

Everything you need to know to find a quality research gap

By: Ethar Al-Saraf (PhD) | Expert Reviewed By: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | November 2022

If you’re just starting out in research, chances are you’ve heard about the elusive research gap (also called a literature gap). In this post, we’ll explore the tricky topic of research gaps. We’ll explain what a research gap is, look at the four most common types of research gaps, and unpack how you can go about finding a suitable research gap for your dissertation, thesis or research project.

Overview: Research Gap 101

- What is a research gap

- Four common types of research gaps

- Practical examples

- How to find research gaps

- Recap & key takeaways

What (exactly) is a research gap?

Well, at the simplest level, a research gap is essentially an unanswered question or unresolved problem in a field, which reflects a lack of existing research in that space. Alternatively, a research gap can also exist when there’s already a fair deal of existing research, but where the findings of the studies pull in different directions , making it difficult to draw firm conclusions.

For example, let’s say your research aims to identify the cause (or causes) of a particular disease. Upon reviewing the literature, you may find that there’s a body of research that points toward cigarette smoking as a key factor – but at the same time, a large body of research that finds no link between smoking and the disease. In that case, you may have something of a research gap that warrants further investigation.

Now that we’ve defined what a research gap is – an unanswered question or unresolved problem – let’s look at a few different types of research gaps.

Types of research gaps

While there are many different types of research gaps, the four most common ones we encounter when helping students at Grad Coach are as follows:

- The classic literature gap

- The disagreement gap

- The contextual gap, and

- The methodological gap

Need a helping hand?

1. The Classic Literature Gap

First up is the classic literature gap. This type of research gap emerges when there’s a new concept or phenomenon that hasn’t been studied much, or at all. For example, when a social media platform is launched, there’s an opportunity to explore its impacts on users, how it could be leveraged for marketing, its impact on society, and so on. The same applies for new technologies, new modes of communication, transportation, etc.

Classic literature gaps can present exciting research opportunities , but a drawback you need to be aware of is that with this type of research gap, you’ll be exploring completely new territory . This means you’ll have to draw on adjacent literature (that is, research in adjacent fields) to build your literature review, as there naturally won’t be very many existing studies that directly relate to the topic. While this is manageable, it can be challenging for first-time researchers, so be careful not to bite off more than you can chew.

2. The Disagreement Gap

As the name suggests, the disagreement gap emerges when there are contrasting or contradictory findings in the existing research regarding a specific research question (or set of questions). The hypothetical example we looked at earlier regarding the causes of a disease reflects a disagreement gap.

Importantly, for this type of research gap, there needs to be a relatively balanced set of opposing findings . In other words, a situation where 95% of studies find one result and 5% find the opposite result wouldn’t quite constitute a disagreement in the literature. Of course, it’s hard to quantify exactly how much weight to give to each study, but you’ll need to at least show that the opposing findings aren’t simply a corner-case anomaly .

3. The Contextual Gap

The third type of research gap is the contextual gap. Simply put, a contextual gap exists when there’s already a decent body of existing research on a particular topic, but an absence of research in specific contexts .

For example, there could be a lack of research on:

- A specific population – perhaps a certain age group, gender or ethnicity

- A geographic area – for example, a city, country or region

- A certain time period – perhaps the bulk of the studies took place many years or even decades ago and the landscape has changed.

The contextual gap is a popular option for dissertations and theses, especially for first-time researchers, as it allows you to develop your research on a solid foundation of existing literature and potentially even use existing survey measures.

Importantly, if you’re gonna go this route, you need to ensure that there’s a plausible reason why you’d expect potential differences in the specific context you choose. If there’s no reason to expect different results between existing and new contexts, the research gap wouldn’t be well justified. So, make sure that you can clearly articulate why your chosen context is “different” from existing studies and why that might reasonably result in different findings.

4. The Methodological Gap

Last but not least, we have the methodological gap. As the name suggests, this type of research gap emerges as a result of the research methodology or design of existing studies. With this approach, you’d argue that the methodology of existing studies is lacking in some way , or that they’re missing a certain perspective.

For example, you might argue that the bulk of the existing research has taken a quantitative approach, and therefore there is a lack of rich insight and texture that a qualitative study could provide. Similarly, you might argue that existing studies have primarily taken a cross-sectional approach , and as a result, have only provided a snapshot view of the situation – whereas a longitudinal approach could help uncover how constructs or variables have evolved over time.

Practical Examples

Let’s take a look at some practical examples so that you can see how research gaps are typically expressed in written form. Keep in mind that these are just examples – not actual current gaps (we’ll show you how to find these a little later!).

Context: Healthcare

Despite extensive research on diabetes management, there’s a research gap in terms of understanding the effectiveness of digital health interventions in rural populations (compared to urban ones) within Eastern Europe.

Context: Environmental Science

While a wealth of research exists regarding plastic pollution in oceans, there is significantly less understanding of microplastic accumulation in freshwater ecosystems like rivers and lakes, particularly within Southern Africa.

Context: Education

While empirical research surrounding online learning has grown over the past five years, there remains a lack of comprehensive studies regarding the effectiveness of online learning for students with special educational needs.

As you can see in each of these examples, the author begins by clearly acknowledging the existing research and then proceeds to explain where the current area of lack (i.e., the research gap) exists.

How To Find A Research Gap

Now that you’ve got a clearer picture of the different types of research gaps, the next question is of course, “how do you find these research gaps?” .

Well, we cover the process of how to find original, high-value research gaps in a separate post . But, for now, I’ll share a basic two-step strategy here to help you find potential research gaps.

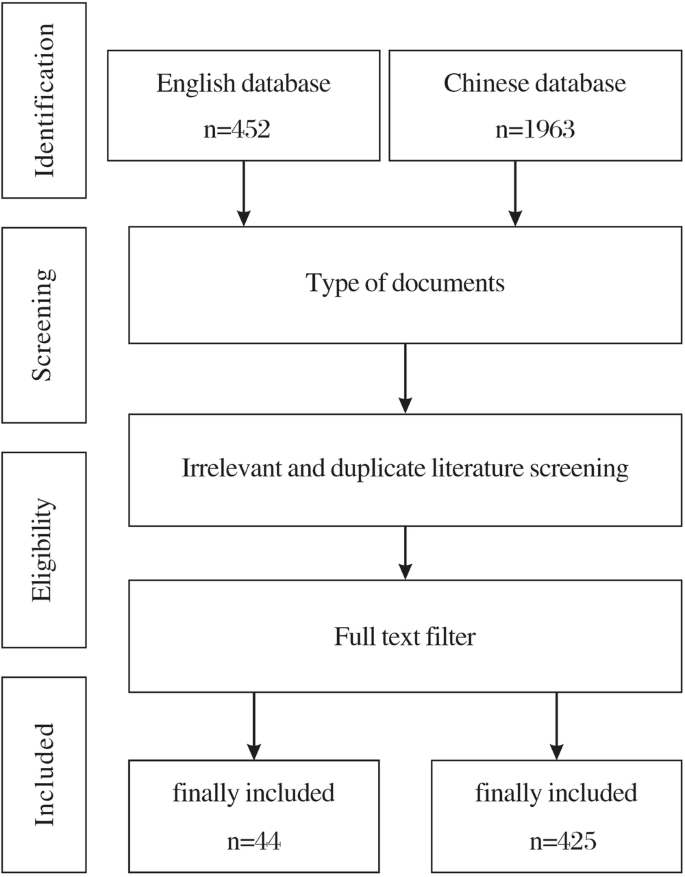

As a starting point, you should find as many literature reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analyses as you can, covering your area of interest. Additionally, you should dig into the most recent journal articles to wrap your head around the current state of knowledge. It’s also a good idea to look at recent dissertations and theses (especially doctoral-level ones). Dissertation databases such as ProQuest, EBSCO and Open Access are a goldmine for this sort of thing. Importantly, make sure that you’re looking at recent resources (ideally those published in the last year or two), or the gaps you find might have already been plugged by other researchers.

Once you’ve gathered a meaty collection of resources, the section that you really want to focus on is the one titled “ further research opportunities ” or “further research is needed”. In this section, the researchers will explicitly state where more studies are required – in other words, where potential research gaps may exist. You can also look at the “ limitations ” section of the studies, as this will often spur ideas for methodology-based research gaps.

By following this process, you’ll orient yourself with the current state of research , which will lay the foundation for you to identify potential research gaps. You can then start drawing up a shortlist of ideas and evaluating them as candidate topics . But remember, make sure you’re looking at recent articles – there’s no use going down a rabbit hole only to find that someone’s already filled the gap 🙂

Let’s Recap

We’ve covered a lot of ground in this post. Here are the key takeaways:

- A research gap is an unanswered question or unresolved problem in a field, which reflects a lack of existing research in that space.

- The four most common types of research gaps are the classic literature gap, the disagreement gap, the contextual gap and the methodological gap.

- To find potential research gaps, start by reviewing recent journal articles in your area of interest, paying particular attention to the FRIN section .

If you’re keen to learn more about research gaps and research topic ideation in general, be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach Blog . Alternatively, if you’re looking for 1-on-1 support with your dissertation, thesis or research project, be sure to check out our private coaching service .

Psst… there’s more (for free)

This post is part of our dissertation mini-course, which covers everything you need to get started with your dissertation, thesis or research project.

You Might Also Like:

29 Comments

This post is REALLY more than useful, Thank you very very much

Very helpful specialy, for those who are new for writing a research! So thank you very much!!

I found it very helpful article. Thank you.

Just at the time when I needed it, really helpful.

Very helpful and well-explained. Thank you

VERY HELPFUL

We’re very grateful for your guidance, indeed we have been learning a lot from you , so thank you abundantly once again.

hello brother could you explain to me this question explain the gaps that researchers are coming up with ?

Am just starting to write my research paper. your publication is very helpful. Thanks so much

How to cite the author of this?

your explanation very help me for research paper. thank you

Very important presentation. Thanks.

Best Ideas. Thank you.

I found it’s an excellent blog to get more insights about the Research Gap. I appreciate it!

Kindly explain to me how to generate good research objectives.

This is very helpful, thank you

Very helpful, thank you.

Thanks a lot for this great insight!

This is really helpful indeed!

This article is really helpfull in discussing how will we be able to define better a research problem of our interest. Thanks so much.

Reading this just in good time as i prepare the proposal for my PhD topic defense.

Very helpful Thanks a lot.

Thank you very much

This was very timely. Kudos

Great one! Thank you all.

Thank you very much.

This is so enlightening. Disagreement gap. Thanks for the insight.

How do I Cite this document please?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Research Gap – Types, Examples and How to Identify

Research Gap – Types, Examples and How to Identify

Table of Contents

Research Gap

Definition:

Research gap refers to an area or topic within a field of study that has not yet been extensively researched or is yet to be explored. It is a question, problem or issue that has not been addressed or resolved by previous research.

How to Identify Research Gap

Identifying a research gap is an essential step in conducting research that adds value and contributes to the existing body of knowledge. Research gap requires critical thinking, creativity, and a thorough understanding of the existing literature . It is an iterative process that may require revisiting and refining your research questions and ideas multiple times.

Here are some steps that can help you identify a research gap:

- Review existing literature: Conduct a thorough review of the existing literature in your research area. This will help you identify what has already been studied and what gaps still exist.

- Identify a research problem: Identify a specific research problem or question that you want to address.

- Analyze existing research: Analyze the existing research related to your research problem. This will help you identify areas that have not been studied, inconsistencies in the findings, or limitations of the previous research.

- Brainstorm potential research ideas : Based on your analysis, brainstorm potential research ideas that address the identified gaps.

- Consult with experts: Consult with experts in your research area to get their opinions on potential research ideas and to identify any additional gaps that you may have missed.

- Refine research questions: Refine your research questions and hypotheses based on the identified gaps and potential research ideas.

- Develop a research proposal: Develop a research proposal that outlines your research questions, objectives, and methods to address the identified research gap.

Types of Research Gap

There are different types of research gaps that can be identified, and each type is associated with a specific situation or problem. Here are the main types of research gaps and their explanations:

Theoretical Gap

This type of research gap refers to a lack of theoretical understanding or knowledge in a particular area. It can occur when there is a discrepancy between existing theories and empirical evidence or when there is no theory that can explain a particular phenomenon. Identifying theoretical gaps can lead to the development of new theories or the refinement of existing ones.

Empirical Gap

An empirical gap occurs when there is a lack of empirical evidence or data in a particular area. It can happen when there is a lack of research on a specific topic or when existing research is inadequate or inconclusive. Identifying empirical gaps can lead to the development of new research studies to collect data or the refinement of existing research methods to improve the quality of data collected.

Methodological Gap

This type of research gap refers to a lack of appropriate research methods or techniques to answer a research question. It can occur when existing methods are inadequate, outdated, or inappropriate for the research question. Identifying methodological gaps can lead to the development of new research methods or the modification of existing ones to better address the research question.

Practical Gap

A practical gap occurs when there is a lack of practical applications or implementation of research findings. It can occur when research findings are not implemented due to financial, political, or social constraints. Identifying practical gaps can lead to the development of strategies for the effective implementation of research findings in practice.

Knowledge Gap

This type of research gap occurs when there is a lack of knowledge or information on a particular topic. It can happen when a new area of research is emerging, or when research is conducted in a different context or population. Identifying knowledge gaps can lead to the development of new research studies or the extension of existing research to fill the gap.

Examples of Research Gap

Here are some examples of research gaps that researchers might identify:

- Theoretical Gap Example : In the field of psychology, there might be a theoretical gap related to the lack of understanding of the relationship between social media use and mental health. Although there is existing research on the topic, there might be a lack of consensus on the mechanisms that link social media use to mental health outcomes.

- Empirical Gap Example : In the field of environmental science, there might be an empirical gap related to the lack of data on the long-term effects of climate change on biodiversity in specific regions. Although there might be some studies on the topic, there might be a lack of data on the long-term effects of climate change on specific species or ecosystems.

- Methodological Gap Example : In the field of education, there might be a methodological gap related to the lack of appropriate research methods to assess the impact of online learning on student outcomes. Although there might be some studies on the topic, existing research methods might not be appropriate to assess the complex relationships between online learning and student outcomes.

- Practical Gap Example: In the field of healthcare, there might be a practical gap related to the lack of effective strategies to implement evidence-based practices in clinical settings. Although there might be existing research on the effectiveness of certain practices, they might not be implemented in practice due to various barriers, such as financial constraints or lack of resources.

- Knowledge Gap Example: In the field of anthropology, there might be a knowledge gap related to the lack of understanding of the cultural practices of indigenous communities in certain regions. Although there might be some research on the topic, there might be a lack of knowledge about specific cultural practices or beliefs that are unique to those communities.

Examples of Research Gap In Literature Review, Thesis, and Research Paper might be:

- Literature review : A literature review on the topic of machine learning and healthcare might identify a research gap in the lack of studies that investigate the use of machine learning for early detection of rare diseases.

- Thesis : A thesis on the topic of cybersecurity might identify a research gap in the lack of studies that investigate the effectiveness of artificial intelligence in detecting and preventing cyber attacks.

- Research paper : A research paper on the topic of natural language processing might identify a research gap in the lack of studies that investigate the use of natural language processing techniques for sentiment analysis in non-English languages.

How to Write Research Gap

By following these steps, you can effectively write about research gaps in your paper and clearly articulate the contribution that your study will make to the existing body of knowledge.

Here are some steps to follow when writing about research gaps in your paper:

- Identify the research question : Before writing about research gaps, you need to identify your research question or problem. This will help you to understand the scope of your research and identify areas where additional research is needed.

- Review the literature: Conduct a thorough review of the literature related to your research question. This will help you to identify the current state of knowledge in the field and the gaps that exist.

- Identify the research gap: Based on your review of the literature, identify the specific research gap that your study will address. This could be a theoretical, empirical, methodological, practical, or knowledge gap.

- Provide evidence: Provide evidence to support your claim that the research gap exists. This could include a summary of the existing literature, a discussion of the limitations of previous studies, or an analysis of the current state of knowledge in the field.

- Explain the importance: Explain why it is important to fill the research gap. This could include a discussion of the potential implications of filling the gap, the significance of the research for the field, or the potential benefits to society.

- State your research objectives: State your research objectives, which should be aligned with the research gap you have identified. This will help you to clearly articulate the purpose of your study and how it will address the research gap.

Importance of Research Gap

The importance of research gaps can be summarized as follows:

- Advancing knowledge: Identifying research gaps is crucial for advancing knowledge in a particular field. By identifying areas where additional research is needed, researchers can fill gaps in the existing body of knowledge and contribute to the development of new theories and practices.

- Guiding research: Research gaps can guide researchers in designing studies that fill those gaps. By identifying research gaps, researchers can develop research questions and objectives that are aligned with the needs of the field and contribute to the development of new knowledge.

- Enhancing research quality: By identifying research gaps, researchers can avoid duplicating previous research and instead focus on developing innovative research that fills gaps in the existing body of knowledge. This can lead to more impactful research and higher-quality research outputs.

- Informing policy and practice: Research gaps can inform policy and practice by highlighting areas where additional research is needed to inform decision-making. By filling research gaps, researchers can provide evidence-based recommendations that have the potential to improve policy and practice in a particular field.

Applications of Research Gap

Here are some potential applications of research gap:

- Informing research priorities: Research gaps can help guide research funding agencies and researchers to prioritize research areas that require more attention and resources.

- Identifying practical implications: Identifying gaps in knowledge can help identify practical applications of research that are still unexplored or underdeveloped.

- Stimulating innovation: Research gaps can encourage innovation and the development of new approaches or methodologies to address unexplored areas.

- Improving policy-making: Research gaps can inform policy-making decisions by highlighting areas where more research is needed to make informed policy decisions.

- Enhancing academic discourse: Research gaps can lead to new and constructive debates and discussions within academic communities, leading to more robust and comprehensive research.

Advantages of Research Gap

Here are some of the advantages of research gap:

- Identifies new research opportunities: Identifying research gaps can help researchers identify areas that require further exploration, which can lead to new research opportunities.

- Improves the quality of research: By identifying gaps in current research, researchers can focus their efforts on addressing unanswered questions, which can improve the overall quality of research.

- Enhances the relevance of research: Research that addresses existing gaps can have significant implications for the development of theories, policies, and practices, and can therefore increase the relevance and impact of research.

- Helps avoid duplication of effort: Identifying existing research can help researchers avoid duplicating efforts, saving time and resources.

- Helps to refine research questions: Research gaps can help researchers refine their research questions, making them more focused and relevant to the needs of the field.

- Promotes collaboration: By identifying areas of research that require further investigation, researchers can collaborate with others to conduct research that addresses these gaps, which can lead to more comprehensive and impactful research outcomes.

Disadvantages of Research Gap

While research gaps can be advantageous, there are also some potential disadvantages that should be considered:

- Difficulty in identifying gaps: Identifying gaps in existing research can be challenging, particularly in fields where there is a large volume of research or where research findings are scattered across different disciplines.

- Lack of funding: Addressing research gaps may require significant resources, and researchers may struggle to secure funding for their work if it is perceived as too risky or uncertain.

- Time-consuming: Conducting research to address gaps can be time-consuming, particularly if the research involves collecting new data or developing new methods.

- Risk of oversimplification: Addressing research gaps may require researchers to simplify complex problems, which can lead to oversimplification and a failure to capture the complexity of the issues.

- Bias : Identifying research gaps can be influenced by researchers’ personal biases or perspectives, which can lead to a skewed understanding of the field.

- Potential for disagreement: Identifying research gaps can be subjective, and different researchers may have different views on what constitutes a gap in the field, leading to disagreements and debate.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

info This is a space for the teal alert bar.

notifications This is a space for the yellow alert bar.

Research Process

- Brainstorming

- Explore Google This link opens in a new window

- Explore Web Resources

- Explore Background Information

- Explore Books

- Explore Scholarly Articles

- Narrowing a Topic

- Primary and Secondary Resources

- Academic, Popular & Trade Publications

- Scholarly and Peer-Reviewed Journals

- Grey Literature

- Clinical Trials

- Evidence Based Treatment

- Scholarly Research

- Database Research Log

- Search Limits

- Keyword Searching

- Boolean Operators

- Phrase Searching

- Truncation & Wildcard Symbols

- Proximity Searching

- Field Codes

- Subject Terms and Database Thesauri

- Reading a Scientific Article

- Website Evaluation

- Article Keywords and Subject Terms

- Cited References

- Citing Articles

- Related Results

- Search Within Publication

- Database Alerts & RSS Feeds

- Personal Database Accounts

- Persistent URLs

- Literature Gap and Future Research

- Web of Knowledge

- Annual Reviews

- Systematic Reviews & Meta-Analyses

- Finding Seminal Works

- Exhausting the Literature

- Finding Dissertations

- Researching Theoretical Frameworks

- Research Methodology & Design

- Tests and Measurements

- Organizing Research & Citations This link opens in a new window

- Scholarly Publication

- Learn the Library This link opens in a new window

Research Articles

These examples below illustrate how researchers from different disciplines identified gaps in existing literature. For additional examples, try a NavigatorSearch using this search string: ("Literature review") AND (gap*)

- Addressing the Recent Developments and Potential Gaps in the Literature of Corporate Sustainability

- Applications of Psychological Science to Teaching and Learning: Gaps in the Literature

- Attitudes, Risk Factors, and Behaviours of Gambling Among Adolescents and Young People: A Literature Review and Gap Analysis

- Do Psychological Diversity Climate, HRM Practices, and Personality Traits (Big Five) Influence Multicultural Workforce Job Satisfaction and Performance? Current Scenario, Literature Gap, and Future Research Directions

- Entrepreneurship Education: A Systematic Literature Review and Identification of an Existing Gap in the Field

- Evidence and Gaps in the Literature on HIV/STI Prevention Interventions Targeting Migrants in Receiving Countries: A Scoping Review

- Homeless Indigenous Veterans and the Current Gaps in Knowledge: The State of the Literature

- A Literature Review and Gap Analysis of Emerging Technologies and New Trends in Gambling

- A Review of Higher Education Image and Reputation Literature: Knowledge Gaps and a Research Agenda

- Trends and Gaps in Empirical Research on Open Educational Resources (OER): A Systematic Mapping of the Literature from 2015 to 2019

- Where Should We Go From Here? Identified Gaps in the Literature in Psychosocial Interventions for Youth With Autism Spectrum Disorder and Comorbid Anxiety

What is a ‘gap in the literature’?

The gap, also considered the missing piece or pieces in the research literature, is the area that has not yet been explored or is under-explored. This could be a population or sample (size, type, location, etc.), research method, data collection and/or analysis, or other research variables or conditions.

It is important to keep in mind, however, that just because you identify a gap in the research, it doesn't necessarily mean that your research question is worthy of exploration. You will want to make sure that your research will have valuable practical and/or theoretical implications. In other words, answering the research question could either improve existing practice and/or inform professional decision-making (Applied Degree), or it could revise, build upon, or create theoretical frameworks informing research design and practice (Ph.D Degree). See the Dissertation Center for additional information about dissertation criteria at NU.

For a additional information on gap statements, see the following:

- How to Find a Gap in the Literature

- Write Like a Scientist: Gap Statements

How do you identify the gaps?

Conducting an exhaustive literature review is your first step. As you search for journal articles, you will need to read critically across the breadth of the literature to identify these gaps. You goal should be to find a ‘space’ or opening for contributing new research. The first step is gathering a broad range of research articles on your topic. You may want to look for research that approaches the topic from a variety of methods – qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods.

See the videos below for further instruction on identifying a gap in the literature.

Identifying a Gap in the Literature - Dr. Laurie Bedford

How Do You Identify Gaps in Literature? - SAGE Research Methods

Literature Gap & Future Research - Library Workshop

This workshop presents effective search techniques for identifying a gap in the literature and recommendations for future research.

Where can you locate research gaps?

As you begin to gather the literature, you will want to critically read for what has, and has not, been learned from the research. Use the Discussion and Future Research sections of the articles to understand what the researchers have found and where they point out future or additional research areas. This is similar to identifying a gap in the literature, however, future research statements come from a single study rather than an exhaustive search. You will want to check the literature to see if those research questions have already been answered.

Roadrunner Search

Identifying the gap in the research relies on an exhaustive review of the literature. Remember, researchers may not explicitly state that a gap in the literature exists; you may need to thoroughly review and assess the research to make that determination yourself.

However, there are techniques that you can use when searching in NavigatorSearch to help identify gaps in the literature. You may use search terms such as "literature gap " or "future research" "along with your subject keywords to pinpoint articles that include these types of statements.

Was this resource helpful?

- << Previous: Resources for a Literature Review

- Next: Web of Knowledge >>

- Last Updated: Mar 31, 2024 4:57 PM

- URL: https://resources.nu.edu/researchprocess

© Copyright 2024 National University. All Rights Reserved.

Privacy Policy | Consumer Information

How to find and fill gaps in the literature [Research Gaps Made Easy]

As we dive deeper into the realm of research, one term repeatedly echoes in the corridors of academia: “gap in literature.”

But what does it mean to find a gap in the literature, and why is it so crucial for your research project?

A gap in the literature refers to an area that hasn’t been studied or lacks substantial inquiry in your field of study. Identifying such gaps allows you to contribute fresh insights and innovation, thereby extending the existing body of knowledge.

It’s the cornerstone for every dissertation or research paper, setting the stage for an introduction that explicitly outlines the scope and aim of your investigation.

This gap review isn’t limited to what has been published in peer-reviewed journals; it may also include conference papers, dissertations, or technical reports, i.e., types of papers that provide an overview of ongoing research.

This step is where your detective work comes in—by spotting trends, common methodologies, and unanswered questions, you can unearth an opportunity to explore an unexplored domain, thereby finding a research gap.

Why Looking for Research Gaps is Essential

Looking for research gaps is essential as it enables the discovery of novel and unique contributions to a particular field.

By identifying these gaps, found through methods such as analyzing concluding remarks of recent papers, literature reviews, examining research groups’ non-peer-reviewed outputs, and utilizing specific search terms on Google Scholar, one can discern the trajectory of ongoing research and unearth opportunities for original inquiry.

These gaps highlight areas of potential innovation, unexplored paths, and disputed concepts, serving as the catalyst for valuable contributions and progression in the field. Hence, finding research gaps forms the basis of substantial and impactful scientific exploration.

Then your research can contribute by finding and filling the gap in knowledge.

Method 1: Utilizing Concluding Remarks of Recent Research

When embarking on a quest to find research gaps, the concluding remarks of recent research papers can serve as an unexpected treasure map.

This section of a paper often contains insightful comments on the limitations of the work and speculates on future research directions.

These comments, although not directly pointing to a research gap, can hint at where the research is heading and what areas require further exploration.

Consider these remarks as signposts, pointing you towards uncharted territories in your field of interest.

For example, you may come across a conclusion in a recent paper on artificial intelligence that indicates a need for more research on ethical considerations. This gives you a direction to explore – the ethical implications of AI.

However, it’s important to bear in mind that while these statements provide valuable leads, they aren’t definitive indicators of research gaps. They provide a starting point, a clue to the vast research puzzle.

Your task is to take these hints, explore further, and discern the most promising areas for your investigation. It’s a bit like being a detective, except your clues come from scholarly papers instead of crime scenes!

Method 2: Examining Research Groups and Non-peer Reviewed Outputs

If concluding remarks are signposts to potential research gaps, non-peer reviewed outputs such as preprints, conference presentations, and dissertations are detailed maps guiding you towards the frontier of research.

These resources reflect the real-time development in the field, giving you a sense of the “buzz” that surrounds hot topics.

These materials, presented but not formally published, offer a sneak peek into ongoing studies, providing you with a rich source of information to identify emerging trends and potential research gaps.

For instance, a presentation on the impact of climate change on mental health might reveal a new line of research that’s in its early stages.

One word of caution: while these resources can be enlightening, they have not undergone the rigorous peer review process that published articles have.

This means the quality of research may vary and the findings should be interpreted with a critical eye. Remember, the key is to pinpoint where the research is heading and then carve out your niche within that sphere.

Exploring non-peer reviewed outputs allows you to stay ahead of the curve, harnessing the opportunity to investigate and contribute to a burgeoning area of study before it becomes mainstream.

Method 3: Searching for ‘Promising’ and ‘Preliminary’ Results on Google Scholar

With a plethora of research at your fingertips, Google Scholar can serve as a remarkable tool in your quest to discover research gaps. The magic lies in a simple trick: search for the phrases “promising results” or “preliminary results” within your research area. Why these specific phrases? Scientists often use them when they have encouraging but not yet fully verified findings.

To illustrate, consider an example. Type “promising results and solar cell” into Google Scholar, and filter by recent publications.

The search results will show you recent studies where researchers have achieved promising outcomes but may not have fully developed their ideas or resolved all challenges.

These “promising” or “preliminary” results often represent areas ripe for further exploration.

They hint at a research question that has been opened but not fully answered. However, tread carefully.

While these findings can indeed point to potential research gaps, they can also lead to dead ends. It’s crucial to examine these leads with a critical eye and further corroborate them with a comprehensive review of related research.

Nevertheless, this approach provides a simple, effective starting point for identifying research gaps, serving as a launchpad for your explorations.

Method 4: Reading Around the Subject

Comprehensive reading forms the bedrock of effective research. When hunting for research gaps, you need to move beyond just the preliminary findings and delve deeper into the context surrounding these results.

This involves broadening your view and reading extensively around your topic of interest.

In the course of your reading, you will start identifying common themes, reoccurring questions, and shared challenges in the research.

Over time, patterns will emerge, helping you recognize areas where research is thin or missing.

For instance, in studying autonomous vehicles, you might find recurring questions about regulatory frameworks, pointing to a potential gap in the legal aspects of this technology.

However, this method is not about scanning through a huge volume of literature aimlessly. It involves strategic and critical reading, looking for patterns, inconsistencies, and areas where the existing literature falls short.

It’s akin to painting a picture where some parts are vividly detailed while others remain sketchy. Your goal is to identify these sketchy areas and fill in the details.

So grab your academic reading list, and start diving into the ocean of knowledge. Remember, it’s not just about the depth, but also the breadth of your reading, that will lead you to a meaningful research gap.

Method 5: Consulting with Current Researchers

Few methods are as effective in uncovering research gaps as engaging in conversations with active researchers in your field of interest.

Current researchers, whether they are PhD students, postdoctoral researchers, or supervisors, are often deeply engaged in ongoing studies and understand the current challenges in their respective fields.

Start by expressing genuine interest in their work. Rather than directly asking for research gaps, inquire about the challenges they are currently facing in their projects.

You can ask, “What are the current challenges in your research?”

Their responses can highlight potential areas of exploration, setting you on the path to identifying meaningful research gaps.

Moreover, supervisors, particularly those overseeing PhD and Master’s students, often have ideas for potential research topics. By asking the right questions, you can tap into their wealth of knowledge and identify fruitful areas of study.

While the act of discovering research gaps can feel like a solitary journey, it doesn’t have to be.

Engaging with others who are grappling with similar challenges can provide valuable insights and guide your path. After all, the world of research thrives on collaboration and shared intellectual curiosity.

Method 6: Utilizing Online Tools

The digital age has made uncovering research gaps easier, thanks to a plethora of online tools that help visualize the interconnectedness of research literature.

Platforms such as:

- Connected Papers,

- ResearchRabbit, and

allow you to see how different papers in your field relate to one another, thereby creating a web of knowledge.

Upon creating this visual web, you may notice that many papers point towards a certain area, but then abruptly stop. This could indicate a potential research gap, suggesting that the topic hasn’t been adequately addressed or has been sidelined for some reason.

By further reading around this apparent gap, you can understand if it’s a genuine knowledge deficit or merely a research path that was abandoned due to inherent challenges or a dead end.

These online tools provide a bird’s eye view of the literature, helping you understand the broader landscape of research in your area of interest.

By examining patterns and relationships among studies, you can effectively zero in on unexplored areas, making these tools a valuable asset in your quest for research gaps.

Method 7: Seeking Conflicting Ideas in the Literature

In scientific research, areas of conflict can often be fertile ground for finding research gaps. These are areas where there’s a considerable amount of disagreement or ongoing debate among researchers.

If you can bring a fresh perspective, a new technique, or a novel hypothesis to such a contentious issue, you may well be on your way to uncovering a significant research gap.

Take, for instance, an area in psychology where there is a heated debate about the influence of nature versus nurture.

If you can introduce a new dimension to the debate or a method to test a novel hypothesis, you could potentially fill a significant gap in the literature.

Investigating areas of conflict not only opens avenues for exploring research gaps, but it also provides opportunities for you to make substantial contributions to your field. The key is to be able to see the potential for a new angle and to muster the courage to dive into contentious waters.

However, engaging with conflicts in research requires careful navigation.

Striking the right balance between acknowledging existing research and championing new ideas is crucial.

In the end, resolving these conflicts or adding significant depth to the debate can be incredibly rewarding and contribute greatly to your field.

The Right Perspective Towards Research Gaps

The traditional understanding of research gaps often involves seeking out a ‘bubble’ of missing knowledge in the sea of existing research, a niche yet to be explored. However, in today’s fast-paced research environment, these bubbles are becoming increasingly rare.

The paradigm of finding research gaps is shifting. It’s no longer just about seeking out holes in existing knowledge, but about understanding the leading edge of research and the directions it could take. It involves not just filling in the gaps but extending the boundaries of knowledge.

To identify such opportunities, develop a comprehensive understanding of the research landscape, identify emerging trends, and keep a close eye on recent advancements.

Look for the tendrils of knowledge extending out into the unknown and think about how you can push them further. It might be a challenging task, but it offers the potential for making substantial, impactful contributions to your field.

Remember, every great innovation begins at the edge of what is known. That’s where your research gap might be hiding.

Wrapping up – Literature and research gaps

Finding and filling a gap in the literature is a task crucial to every research project. It begins with a systematic review of existing literature – a quest to identify what has been studied and more importantly, what hasn’t.

You must delve into the rich terrain of literature in their field, from the seminal, citation-heavy research articles to the fresh perspective of conference papers. Identifying the gap in the literature necessitates a thorough evaluation of existing studies to refine your area of interest and map the scope and aim of your future research.

The purpose is to explicitly identify the gap that exists, so you can contribute to the body of knowledge by providing fresh insights. The process involves a series of steps, from consulting with faculty and experts in the field to identify potential trends and outdated methodologies, to being methodological in your approach to identify gaps that have emerged.

Upon finding a gap in the literature, we’ll ideally have a clearer picture of the research need and an opportunity to explore this unexplored domain.

It is important to remember that the task does not end with identifying the gap. The real challenge lies in drafting a research proposal that’s objective, answerable, and can quantify the impact of filling this gap.

It’s important to consult with your advisor, and also look at commonly used parameters and preliminary evidence. Only then can we complete the task of turning an identified gap in the literature into a valuable contribution to your field, a contribution that’s peer-reviewed and adds to the body of knowledge.

To find a research gap is to stand on the shoulders of giants, looking beyond the existing research to further expand our understanding of the world.

Dr Andrew Stapleton has a Masters and PhD in Chemistry from the UK and Australia. He has many years of research experience and has worked as a Postdoctoral Fellow and Associate at a number of Universities. Although having secured funding for his own research, he left academia to help others with his YouTube channel all about the inner workings of academia and how to make it work for you.

Thank you for visiting Academia Insider.

We are here to help you navigate Academia as painlessly as possible. We are supported by our readers and by visiting you are helping us earn a small amount through ads and affiliate revenue - Thank you!

2024 © Academia Insider

Identifying Research Gaps to Pursue Innovative Research

This article is an excerpt from a lecture given by my Ph.D. guide, a researcher in public health. She advised us on how to identify research gaps to pursue innovative research in our fields.

What is a Research Gap?

Today we are talking about the research gap: what is it, how to identify it, and how to make use of it so that you can pursue innovative research. Now, how many of you have ever felt you had discovered a new and exciting research question , only to find that it had already been written about? I have experienced this more times than I can count. Graduate studies come with pressure to add new knowledge to the field. We can contribute to the progress and knowledge of humanity. To do this, we need to first learn to identify research gaps in the existing literature.

A research gap is, simply, a topic or area for which missing or insufficient information limits the ability to reach a conclusion for a question. It should not be confused with a research question, however. For example, if we ask the research question of what the healthiest diet for humans is, we would find many studies and possible answers to this question. On the other hand, if we were to ask the research question of what are the effects of antidepressants on pregnant women, we would not find much-existing data. This is a research gap. When we identify a research gap, we identify a direction for potentially new and exciting research.

How to Identify Research Gap?

Considering the volume of existing research, identifying research gaps can seem overwhelming or even impossible. I don’t have time to read every paper published on public health. Similarly, you guys don’t have time to read every paper. So how can you identify a research gap?

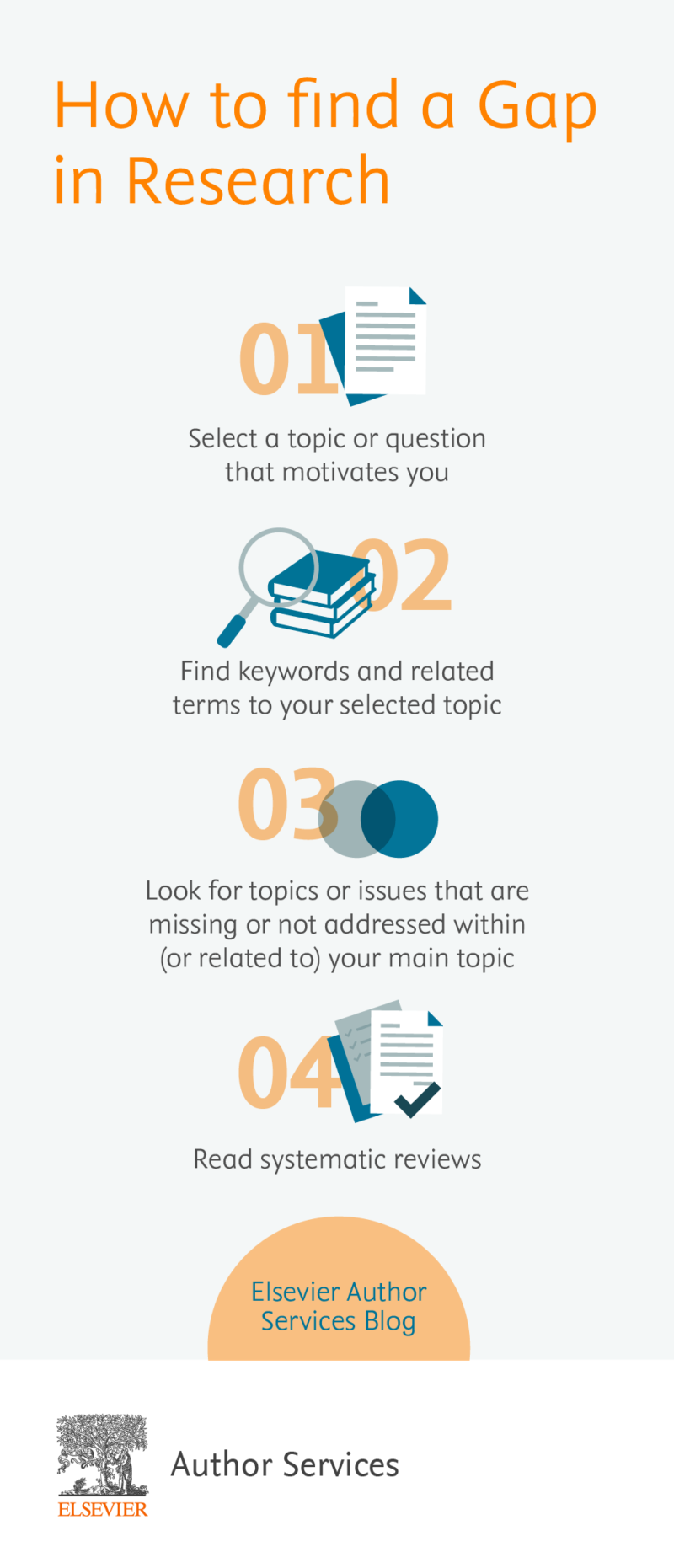

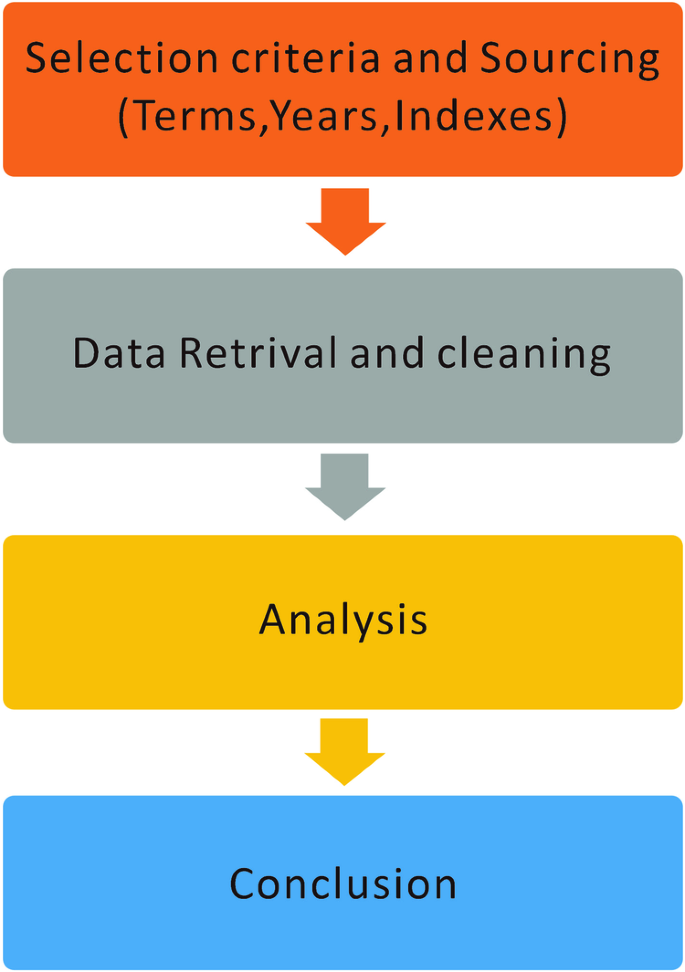

There are different techniques in various disciplines, but we can reduce most of them down to a few steps, which are:

- Identify your key motivating issue/question

- Identify key terms associated with this issue

- Review the literature, searching for these key terms and identifying relevant publications

- Review the literature cited by the key publications which you located in the above step

- Identify issues not addressed by the literature relating to your critical motivating issue

It is the last step which we all find the most challenging. It can be difficult to figure out what an article is not saying. I like to keep a list of notes of biased or inconsistent information. You could also track what authors write as “directions for future research,” which often can point us towards the existing gaps.

Different Types of Research Gaps

Identifying research gaps is an essential step in conducting research, as it helps researchers to refine their research questions and to focus their research efforts on areas where there is a need for more knowledge or understanding.

1. Knowledge gaps

These are gaps in knowledge or understanding of a subject, where more research is needed to fill the gaps. For example, there may be a lack of understanding of the mechanisms behind a particular disease or how a specific technology works.

2. Conceptual gaps

These are gaps in the conceptual framework or theoretical understanding of a subject. For example, there may be a need for more research to understand the relationship between two concepts or to refine a theoretical framework.

3. Methodological gaps

These are gaps in the methods used to study a particular subject. For example, there may be a need for more research to develop new research methods or to refine existing methods to address specific research questions.

4. Data gaps

These are gaps in the data available on a particular subject. For example, there may be a need for more research to collect data on a specific population or to develop new measures to collect data on a particular construct.

5. Practical gaps

These are gaps in the application of research findings to practical situations. For example, there may be a need for more research to understand how to implement evidence-based practices in real-world settings or to identify barriers to implementing such practices.

Examples of Research Gap

Limited understanding of the underlying mechanisms of a disease:.

Despite significant research on a particular disease, there may be a lack of understanding of the underlying mechanisms of the disease. For example, although much research has been done on Alzheimer’s disease, the exact mechanisms that lead to the disease are not yet fully understood.

Inconsistencies in the findings of previous research:

When previous research on a particular topic has inconsistent findings, there may be a need for further research to clarify or resolve these inconsistencies. For example, previous research on the effectiveness of a particular treatment for a medical condition may have produced inconsistent findings, indicating a need for further research to determine the true effectiveness of the treatment.

Limited research on emerging technologies:

As new technologies emerge, there may be limited research on their applications, benefits, and potential drawbacks. For example, with the increasing use of artificial intelligence in various industries, there is a need for further research on the ethical, legal, and social implications of AI.

How to Deal with Literature Gap?

Once you have identified the literature gaps, it is critical to prioritize. You may find many questions which remain to be answered in the literature. Often one question must be answered before the next can be addressed. In prioritizing the gaps, you have identified, you should consider your funding agency or stakeholders, the needs of the field, and the relevance of your questions to what is currently being studied. Also, consider your own resources and ability to conduct the research you’re considering. Once you have done this, you can narrow your search down to an appropriate question.

Tools to Help Your Search

There are thousands of new articles published every day, and staying up to date on the literature can be overwhelming. You should take advantage of the technology that is available. Some services include PubCrawler , Feedly , Google Scholar , and PubMed updates. Stay up to date on social media forums where scholars share new discoveries, such as Twitter. Reference managers such as Mendeley can help you keep your references well-organized. I personally have had success using Google Scholar and PubMed to stay current on new developments and track which gaps remain in my personal areas of interest.

The most important thing I want to impress upon you today is that you will struggle to choose a research topic that is innovative and exciting if you don’t know the existing literature well. This is why identifying research gaps starts with an extensive and thorough literature review . But give yourself some boundaries. You don’t need to read every paper that has ever been written on a topic. You may find yourself thinking you’re on the right track and then suddenly coming across a paper that you had intended to write! It happens to everyone- it happens to me quite often. Don’t give up- keep reading and you’ll find what you’re looking for.

Class dismissed!

How do you identify research gaps? Share your thoughts in the comments section below.

Frequently Asked Questions

A research gap can be identified by looking for a topic or area with missing or insufficient information that limits the ability to reach a conclusion for a question.

Identifying a research gap is important as it provides a direction for potentially new research or helps bridge the gap in existing literature.

Gap in research is a topic or area with missing or insufficient information. A research gap limits the ability to reach a conclusion for a question.

Thank u for your suggestion.

Very useful tips specially for a beginner

Thank you. This is helpful. I find that I’m overwhelmed with literatures. As I read on a particular topic, and in a particular direction I find that other conflicting issues, topic a and ideas keep popping up, making me more confused.

I am very grateful for your advice. It’s just on point.

The clearest, exhaustive, and brief explanation I have ever read.

Thanks for sharing

Thank you very much.The work is brief and understandable

Thank you it is very informative

Thanks for sharing this educative article

Thank you for such informative explanation.

Great job smart guy! Really outdid yourself!

Nice one! I thank you for this as it is just what I was looking for!😃🤟

Thank you so much for this. Much appreciated

Thank you so much.

Thankyou for ur briefing…its so helpful

Thank you so much .I’ved learn a lot from this.❤️

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Reporting Research

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for data interpretation

In research, choosing the right approach to understand data is crucial for deriving meaningful insights.…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right approach

The process of choosing the right research design can put ourselves at the crossroads of…

- Career Corner

Unlocking the Power of Networking in Academic Conferences

Embarking on your first academic conference experience? Fear not, we got you covered! Academic conferences…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Research recommendations play a crucial role in guiding scholars and researchers toward fruitful avenues of…

- AI in Academia

Disclosing the Use of Generative AI: Best practices for authors in manuscript preparation

The rapid proliferation of generative and other AI-based tools in research writing has ignited an…

Intersectionality in Academia: Dealing with diverse perspectives

Meritocracy and Diversity in Science: Increasing inclusivity in STEM education

Avoiding the AI Trap: Pitfalls of relying on ChatGPT for PhD applications

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

UNE Library Services

Research Help

Gaps in the literature.

Gaps in the literature are missing pieces or insufficient information in the published research on a topic. These are areas that have opportunities for further research because they are unexplored, under-explored, or outdated.

Finding Gaps

Gaps can be missing or incomplete:

- Population or sample: size, type, location etc…

- Research methods: qualitative, quantitative, or mixed

- Data collection or analysis

- Research variables or conditions

Conduct a thorough literature search to find a broad range of research articles on your topic. Search research databases ; you can find recommended databases for your subject area in research by subject for your course or program.

Identifying Gaps

If you do not find articles in your literature search, this may indicate a gap.

If you do find articles, the goal is to find a gap for contributing new research. Authors signal that there is a gap using words such as:

- Has not been clarified, studied, reported, or elucidated

- Further research is required or needed

- Is not well reported

- Suggestions for further research

- Key question is or remains

- It is important to address

- Poorly understood or known

- Lack of studies

- These findings provide valuable insights into the potential benefits of mindfulness-based interventions for stress management,however, further study is needed to address several limitations and extend our understanding in this area .

- While this study provides preliminary evidence of the potential efficacy of VRET in reducing PTSD symptoms, several aspects related to its implementation and specific treatment outcomes remain inadequately clarified, highlighting the need for further research .

- Although the studies reviewed provide valuable insights into the potential effects of climate change on species composition and ecosystem functioning. The question of how climate change will interact with other anthropogenic stressors to influence the resilience and adaptive capacity of tropical rainforest ecosystems remains unanswered, highlighting the need for further research .

Questions & Help

If you have questions on this, or another, topic, contact a librarian for help!

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Identify a Research Gap

- 5-minute read

- 10th January 2024

If you’ve been tasked with producing a thesis or dissertation, one of your first steps will be identifying a research gap. Although finding a research gap may sound daunting, don’t fret! In this post, we will define a research gap, discuss its importance, and offer a step-by-step guide that will provide you with the essential know-how to complete this critical step and move on to the rest of your research project.

What Is a Research Gap?

Simply put, a research gap is an area that hasn’t been explored in the existing literature. This could be an unexplored population, an untested method, or a condition that hasn’t been investigated yet.

Why Is Identifying a Research Gap Important?

Identifying a research gap is a foundational step in the research process. It ensures that your research is significant and has the ability to advance knowledge within a specific area. It also helps you align your work with the current needs and challenges of your field. Identifying a research gap has many potential benefits.

1. Avoid Redundancy in Your Research

Understanding the existing literature helps researchers avoid duplication. This means you can steer clear of topics that have already been extensively studied. This ensures your work is novel and contributes something new to the field.

2. Guide the Research Design

Identifying a research gap helps shape your research design and questions. You can tailor your studies to specifically address the identified gap. This ensures that your work directly contributes to filling the void in knowledge.

3. Practical Applications

Research that addresses a gap is more likely to have practical applications and contributions. Whether in academia, industry, or policymaking, research that fills a gap in knowledge is often more applicable and can inform decision-making and practices in real-world contexts.

4. Field Advancements

Addressing a research gap can lead to advancements in the field . It may result in the development of new theories, methodologies, or technologies that push the boundaries of current understanding.

5. Strategic Research Planning

Identifying a research gap is crucial for strategic planning . It helps researchers and institutions prioritize areas that need attention so they can allocate resources effectively. This ensures that efforts are directed toward the most critical gaps in knowledge.

6. Academic and Professional Recognition