How many participants do I need for qualitative research?

- Participant recruitment

- Qualitative research

6 min read David Renwick

For those new to the qualitative research space, there’s one question that’s usually pretty tough to figure out, and that’s the question of how many participants to include in a study. Regardless of whether it’s research as part of the discovery phase for a new product, or perhaps an in-depth canvas of the users of an existing service, researchers can often find it difficult to agree on the numbers. So is there an easy answer? Let’s find out.

Here, we’ll look into the right number of participants for qualitative research studies. If you want to know about participants for quantitative research, read Nielsen Norman Group’s article .

Getting the numbers right

So you need to run a series of user interviews or usability tests and aren’t sure exactly how many people you should reach out to. It can be a tricky situation – especially for those without much experience. Do you test a small selection of 1 or 2 people to make the recruitment process easier? Or, do you go big and test with a series of 10 people over the course of a month? The answer lies somewhere in between.

It’s often a good idea (for qualitative research methods like interviews and usability tests) to start with 5 participants and then scale up by a further 5 based on how complicated the subject matter is. You may also find it helpful to add additional participants if you’re new to user research or you’re working in a new area.

What you’re actually looking for here is what’s known as saturation.

Understanding saturation

Whether it’s qualitative research as part of a master’s thesis or as research for a new online dating app, saturation is the best metric you can use to identify when you’ve hit the right number of participants.

In a nutshell, saturation is when you’ve reached the point where adding further participants doesn’t give you any further insights. It’s true that you may still pick up on the occasional interesting detail, but all of your big revelations and learnings have come and gone. A good measure is to sit down after each session with a participant and analyze the number of new insights you’ve noted down.

Interestingly, in a paper titled How Many Interviews Are Enough? , authors Greg Guest, Arwen Bunce and Laura Johnson noted that saturation usually occurs with around 12 participants in homogeneous groups (meaning people in the same role at an organization, for example). However, carrying out ethnographic research on a larger domain with a diverse set of participants will almost certainly require a larger sample.

Ensuring you’ve hit the right number of participants

How do you know when you’ve reached saturation point? You have to keep conducting interviews or usability tests until you’re no longer uncovering new insights or concepts.

While this may seem to run counter to the idea of just gathering as much data from as many people as possible, there’s a strong case for focusing on a smaller group of participants. In The logic of small samples in interview-based , authors Mira Crouch and Heather McKenzie note that using fewer than 20 participants during a qualitative research study will result in better data. Why? With a smaller group, it’s easier for you (the researcher) to build strong close relationships with your participants, which in turn leads to more natural conversations and better data.

There’s also a school of thought that you should interview 5 or so people per persona. For example, if you’re working in a company that has well-defined personas, you might want to use those as a basis for your study, and then you would interview 5 people based on each persona. This maybe worth considering or particularly important when you have a product that has very distinct user groups (e.g. students and staff, teachers and parents etc).

How your domain affects sample size

The scope of the topic you’re researching will change the amount of information you’ll need to gather before you’ve hit the saturation point. Your topic is also commonly referred to as the domain.

If you’re working in quite a confined domain, for example, a single screen of a mobile app or a very specific scenario, you’ll likely find interviews with 5 participants to be perfectly fine. Moving into more complicated domains, like the entire checkout process for an online shopping app, will push up your sample size.

As Mitchel Seaman notes : “Exploring a big issue like young peoples’ opinions about healthcare coverage, a broad emotional issue like postmarital sexuality, or a poorly-understood domain for your team like mobile device use in another country can drastically increase the number of interviews you’ll want to conduct.”

In-person or remote

Does the location of your participants change the number you need for qualitative user research? Well, not really – but there are other factors to consider.

- Budget: If you choose to conduct remote interviews/usability tests, you’ll likely find you’ve got lower costs as you won’t need to travel to your participants or have them travel to you. This also affects…

- Participant access: Remote qualitative research can be a lifesaver when it comes to participant access. No longer are you confined to the people you have physical access to — instead you can reach out to anyone you’d like.

- Quality: On the other hand, remote research does have its downsides. For one, you’ll likely find you’re not able to build the same kinds of relationships over the internet or phone as those in person, which in turn means you never quite get the same level of insights.

Is there value in outsourcing recruitment?

Recruitment is understandably an intensive logistical exercise with many moving parts. If you’ve ever had to recruit people for a study before, you’ll understand the need for long lead times (to ensure you have enough participants for the project) and the countless long email chains as you discuss suitable times.

Outsourcing your participant recruitment is just one way to lighten the logistical load during your research. Instead of having to go out and look for participants, you have them essentially delivered to you in the right number and with the right attributes.

We’ve got one such service at Optimal Workshop, which means it’s the perfect accompaniment if you’re also using our platform of UX tools. Read more about that here .

So that’s really most of what there is to know about participant recruitment in a qualitative research context. As we said at the start, while it can appear quite tricky to figure out exactly how many people you need to recruit, it’s actually not all that difficult in reality.

Overall, the number of participants you need for your qualitative research can depend on your project among other factors. It’s important to keep saturation in mind, as well as the locale of participants. You also need to get the most you can out of what’s available to you. Remember: Some research is better than none!

Capture, analyze and visualize your qualitative data.

Try our qualitative research tool for usability testing, interviewing and note-taking. Reframer by Optimal Workshop.

Published on August 8, 2019

David Renwick

David is Optimal Workshop's Content Strategist and Editor of CRUX. You can usually find him alongside one of the office dogs 🐕 (Bella, Bowie, Frida, Tana or Steezy). Connect with him on LinkedIn.

Recommended for you

How to encourage people to participate in your study

Encouraging people to take part in your study can be one of the hardest parts of the research process.

Tips for recruiting quality research participants

If there’s one universal truth in user research, it’s that at some point you’re going to need to find people to actually take part in your studies. Be it a large number of participants for quantitative research or a select number for in-depth, in-person user interviews. Finding the right people (and number) of people can... View Article

Taking better notes for better sensemaking

This post makes suggestions for practitioners as part of observing users during UX interviews.

Try Optimal Workshop tools for free

What are you looking for.

Explore all tags

Discover more from Optimal Workshop

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Qualitative study design: Sampling

- Qualitative study design

- Phenomenology

- Grounded theory

- Ethnography

- Narrative inquiry

- Action research

- Case Studies

- Field research

- Focus groups

- Observation

- Surveys & questionnaires

- Study Designs Home

As part of your research, you will need to identify "who" you need to recruit or work with to answer your research question/s. Often this population will be quite large (such as nurses or doctors across Victoria), or they may be difficult to access (such as people with mental health conditions). Sampling is a way that you can choose a smaller group of your population to research and then generalize the results of this across the larger population.

There are several ways that you can sample. Time, money, and difficulty or ease in reaching your target population will shape your sampling decisions. While there are no hard and fast rules around how many people you should involve in your research, some researchers estimate between 10 and 50 participants as being sufficient depending on your type of research and research question (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Other study designs may require you to continue gathering data until you are no longer discovering new information ("theoretical saturation") or your data is sufficient to answer your question ("data saturation").

Why is it important to think about sampling?

It is important to match your sample as far as possible to the broader population that you wish to generalise to. The extent to which your findings can be applied to settings or people outside of who you have researched ("generalisability") can be influenced by your sample and sampling approach. For example, if you have interviewed homeless people in hospital with mental health conditions, you may not be able to generalise the results of this to every person in Australia with a mental health condition, or every person who is homeless, or every person who is in hospital. Your sampling approach will vary depending on what you are researching, but you might use a non-probability or probability (or randomised) approach.

Non-Probability sampling approaches

Non-Probability sampling is not randomised, meaning that some members of your population will have a higher chance of being included in your study than others. If you wanted to interview homeless people with mental health conditions in hospital and chose only homeless people with mental health conditions at your local hospital, this would be an example of convenience sampling; you have recruited participants who are close to hand. Other times, you may ask your participants if they can recommend other people who may be interested in the study: this is an example of snowball sampling. Lastly, you might want to ask Chief Executive Officers at rural hospitals how they support their staff mental health; this is an example of purposive sampling.

Examples of non-probability sampling include:

- Purposive (judgemental)

- Convenience

Probability (Randomised) sampling

Probability sampling methods are also called randomised sampling. They are generally preferred in research as this approach means that every person in a population has a chance of being selected for research. Truly randomised sampling is very complex; even a simple random sample requires the use of a random number generator to be used to select participants from a list of sampling frame of the accessible population. For example, if you were to do a probability sample of homeless people in hospital with a mental health condition, you would need to develop a table of all people matching this criteria; allocate each person a number; and then use a random number generator to find your sample pool. For this reason, while probability sampling is preferred, it may not be feasible to draw out a probability sample.

Things to remember:

- Sampling involves selecting a small subsection of your population to generalise back to a larger population

- Your sampling approach (probability or non-probability) will reflect how you will recruit your participants, and how generalisable your results are to the wider population

- How many participants you include in your study will vary based on your research design, research question, and sampling approach

Further reading:

Babbie, E. (2008). The basics of social research (4th ed). Belmont: Thomson Wadsworth

Creswell, J.W. & Creswell, J.D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (5th ed). Thousand Oaks: SAGE

Salkind, N.J. (2010) Encyclopedia of research design. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications

Vasileiou, K., Barnett, J., Thorpe, S., & Young, T. (2018). Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(148)

- << Previous: Interviews

- Next: Appraisal >>

- Last Updated: Jun 13, 2024 10:34 AM

- URL: https://deakin.libguides.com/qualitative-study-designs

What’s in a Number? Understanding the Right Sample Size for Qualitative Research

- May 3, 2019

By Julia Schaefer

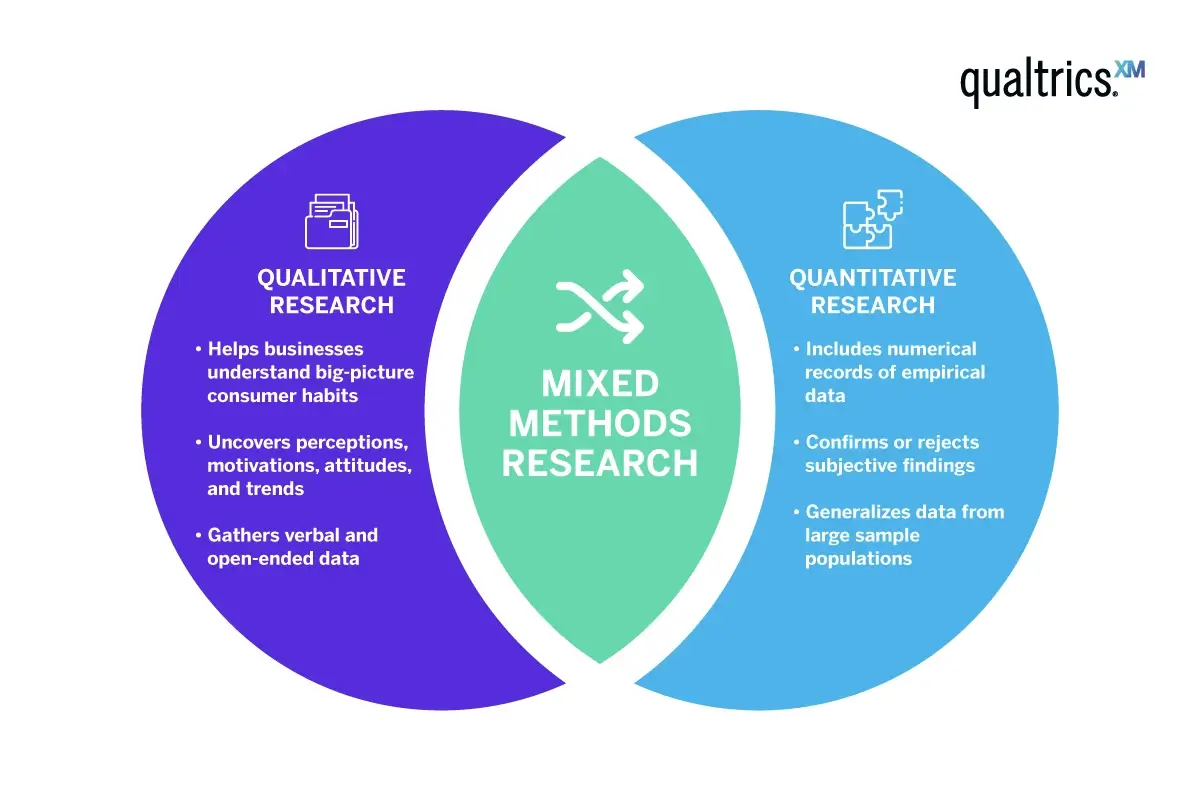

Unlike quantitative research , numbers matter less when doing qualitative research.

It’s about quality, not quantity. So what’s in a number?

When thinking about sample size, it’s really important to ensure that you understand your target and have recruited the right people for the study. Whether your company is targeting moms from the Midwest with household incomes of $70k+, or teens who use Facebook for more than 8 hours a week, it’s crucial to understand the goals and objectives of the study and how the right target can help answer your essential research questions.

Determining the Right Sample Size For Qualitative Research Tip #1: Right Size for Qualitative Research

A high-quality panel includes much more than just members who are pulled from a general population. The right respondents for the study will have met all the criteria line-items identified from quantitative research studies and check the boxes that the client has identified through their own research. Only participants who match the audience specifications and background relevance expressed by the client should be actively recruited.

Determining the Right Sample Size For Qualitative Research Tip #2: No Two Studies are Alike

Choosing an appropriate study design is an important factor to consider when determining which sample size to use. There are various methods that can be used to gather insightful data, but not all methods may be applicable to your study and your project goal. In-depth interviews , focus groups , and ethnographic research are the most common methods used in qualitative market research. Each method can provide unique information and certain methods are more relevant than others. The types of questions being studied play an equally important role in deciding on a sample size.

Determining the Right Sample Size For Qualitative Research Tip #3: Principle of Saturation and Diminishing Returns

Understanding the difference of which qualitative study to use is very important. Your study should have a large enough sample size to uncover a variety of opinions, and the sample size should be limited at the point of saturation.

Saturation occurs when adding more participants to the study does not result in obtaining additional perspectives or information. One can say there is a point of diminishing returns with larger samples, as it leads to more data but doesn’t necessarily lead to more information. A sample size should be large enough to sufficiently describe the phenomenon of interest, and address the research question at hand. However, a large sample size risks having repetitive and redundant data.

The objective of qualitative research is to reduce discovery failure, while quantitative research aims to reduce estimation error. As qualitative research works to obtain diverse opinions from a sample size on a client’s product/service/project, saturated data does benefit the project findings. As part of the analysis framework, one respondent’s opinion is enough to generate a code.

The Magic Number? Between 15-30

Based on research conducted on this issue, if you are building similar segments within the population, InterQ’s recommendation for in-depth interviews is to have a sample size of 15-30. In some cases, a minimum of 10 is sufficient, assuming there has been integrity in the recruiting process. With the goal to maintain a rigorous recruiting process, studies have noted having a sample size as little as 10 can be extremely fruitful, and still yield strong results.

Curious about qualitative research? Request a proposal today >

- Request Proposal

- Participate in Studies

- Our Leadership Team

- Our Approach

- Mission, Vision and Core Values

- Qualitative Research

- Quantitative Research

- Research Insights Workshops

- Customer Journey Mapping

- Millennial & Gen Z Market Research

- Market Research Services

- Our Clients

- InterQ Blog

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Grad Med Educ

- v.4(1); 2012 Mar

Qualitative Research Part II: Participants, Analysis, and Quality Assurance

This is the second of a two-part series on qualitative research. Part 1 in the December 2011 issue of Journal of Graduate Medical Education provided an introduction to the topic and compared characteristics of quantitative and qualitative research, identified common data collection approaches, and briefly described data analysis and quality assessment techniques. Part II describes in more detail specific techniques and methods used to select participants, analyze data, and ensure research quality and rigor.

If you are relatively new to qualitative research, some references you may find especially helpful are provided below. The two texts by Creswell 2008 and 2009 are clear and practical. 1 , 2 In 2008, the British Medical Journal offered a series of short essays on qualitative research; the references provided are easily read and digested. 3 – , 8 For those wishing to pursue qualitative research in more detail, a suggestion is to start with the appropriate chapters in Creswell 2008, 1 and then move to the other texts suggested. 9 – , 11

To summarize the previous editorial, while quantitative research focuses predominantly on the impact of an intervention and generally answers questions like “did it work?” and “what was the outcome?”, qualitative research focuses on understanding the intervention or phenomenon and exploring questions like “why was this effective or not?” and “how is this helpful for learning?” The intent of qualitative research is to contribute to understanding. Hence, the research procedures for selecting participants, analyzing data, and ensuring research rigor differ from those for quantitative research. The following sections address these approaches. table 1 provides a comparative summary of methodological approaches for quantitative and qualitative research.

A Comparison of Qualitative and Quantitative Methodological Approaches

Data collection methods most commonly used in qualitative research are individual or group interviews (including focus groups), observation, and document review. They can be used alone or in combination. While the following sections are written in the context of using interviews or focus groups to collect data, the principles described for sample selection, data analysis, and quality assurance are applicable across qualitative approaches.

Selecting Participants

Quantitative research requires standardization of procedures and random selection of participants to remove the potential influence of external variables and ensure generalizability of results. In contrast, subject selection in qualitative research is purposeful; participants are selected who can best inform the research questions and enhance understanding of the phenomenon under study. 1 , 8 Hence, one of the most important tasks in the study design phase is to identify appropriate participants. Decisions regarding selection are based on the research questions, theoretical perspectives, and evidence informing the study.

The subjects sampled must be able to inform important facets and perspectives related to the phenomenon being studied. For example, in a study looking at a professionalism intervention, representative participants could be considered by role (residents and faculty), perspective (those who approve/disapprove the intervention), experience level (junior and senior residents), and/or diversity (gender, ethnicity, other background).

The second consideration is sample size. Quantitative research requires statistical calculation of sample size a priori to ensure sufficient power to confirm that the outcome can indeed be attributed to the intervention. In qualitative research, however, the sample size is not generally predetermined. The number of participants depends upon the number required to inform fully all important elements of the phenomenon being studied. That is, the sample size is sufficient when additional interviews or focus groups do not result in identification of new concepts, an end point called data saturation . To determine when data saturation occurs, analysis ideally occurs concurrently with data collection in an iterative cycle. This allows the researcher to document the emergence of new themes and also to identify perspectives that may otherwise be overlooked. In the professionalism intervention example, as data are analyzed, the researchers may note that only positive experiences and views are being reported. At this time, a decision could be made to identify and recruit residents who perceived the experience as less positive.

Data Analysis

The purpose of qualitative analysis is to interpret the data and the resulting themes, to facilitate understanding of the phenomenon being studied. It is often confused with content analysis, which is conducted to identify and describe results. 12 In the professionalism intervention example, content analysis of responses might report that residents identified the positive elements of the innovation to be integration with real patient cases, opportunity to hear the views of others, and time to reflect on one's own professionalism. An interpretive analysis, on the other hand, would seek to understand these responses by asking questions such as, “Were there conditions that most frequently elicited these positive responses?” Further interpretive analysis might show that faculty engagement influenced the positive responses, with more positive features being described by residents who had faculty who openly reflected upon their own professionalism or who asked probing questions about the cases. This interpretation can lead to a deeper understanding of the results and to new ideas or theories about relationships and/or about how and why the innovation was or was not effective.

Interpretive analysis is generally seen as being conducted in 3 stages: deconstruction, interpretation, and reconstruction. 11 These stages occur after preparing the data for analysis, ie, after transcription of the interviews or focus groups and verification of the transcripts with the recording.

- Deconstruction refers to breaking down data into component parts in order to see what is included. It is similar to content analysis mentioned above. It requires reading and rereading interview or focus group transcripts and then breaking down data into categories or codes that describe the content.

- Interpretation follows deconstruction and refers to making sense of and understanding the coded data. It involves comparing data codes and categories within and across transcripts and across variables deemed important to the study (eg, year of residency, discipline, engagement of faculty). Techniques for interpreting data and findings include discussion and comparison of codes among research team members while purposefully looking for similarities and differences among themes, comparing findings with those of other studies, exploring theories which might explain relationships among themes, and exploring negative results (those that do not confirm the dominant themes) in more detail.

- Reconstruction refers to recreating or repackaging the prominent codes and themes in a manner that shows the relationships and insights derived in the interpretation phase and that explains them more broadly in light of existing knowledge and theoretical perspectives. Generally one or two central concepts will emerge as central or overarching, and others will appear as subthemes that further contribute to the central concepts. Reconstruction requires contextualizing the findings, ie, positioning and framing them within existing theory, evidence, and practice.

Ensuring Research Quality and Rigor

Within qualitative research, two main strategies promote the rigor and quality of the research: ensuring the quality or “authenticity” of the data and the quality or “trustworthiness” of the analysis. 8 , 12 These are similar in many ways to ensuring validity and reliability, respectively, in quantitative research.

1. Authenticity of the data refers to the quality of the data and data collection procedures. Elements to consider include:

• Sampling approach and participant selection to enable the research question to be addressed appropriately (see “Selecting Participants” above) and reduce the potential of having a biased sample.

• Data triangulation refers to using multiple data sources to produce a more comprehensive view of the phenomenon being studied, eg, interviewing both residents and faculty and using multiple residency sites and/or disciplines.

• Using the appropriate method to answer the research questions, considering the nature of the topic being explored, eg, individual interviews rather than focus groups are generally more appropriate for topics of a sensitive nature.

• Using interview and other guides that are not biased or leading, ie, that do not ask questions in a way that may lead the participant to answer in a particular manner.

• The researcher's and research team's relationships to the study setting and participants need to be explicit, eg, describe the potential for coercion when a faculty member requests his or her own residents to participate in a study.

• The researcher's and team members' own biases and beliefs relative to the phenomenon under study must be made explicit, and, when necessary, appropriate steps must be taken to reduce their impact on the quality of data collected, eg, by selecting a neutral “third party” interviewer.

2. Trustworthiness of the analysis refers to the quality of data analysis. Elements to consider when assessing the quality of analysis include:

• Analysis process: is this clearly described, eg, the roles of the team members, what was done, timing, and sequencing? Is it clear how the data codes or categories were developed? Does the process reflect best practices, eg, comparison of findings within and among transcripts, and use of memos to record decision points?

• Procedure for resolving differences in findings and among team members: this needs to be clearly described.

• Process for addressing the potential influence the researchers' views and beliefs may have upon the analysis.

• Use of a qualitative software program: if used, how was this used?

In summary, this editorial has addressed 3 components of conducting qualitative research: selecting participants, performing data analysis, and assuring research rigor and quality. See table 2 for the key elements for each of these topics.

Conducting Qualitative Research: Summary of Key Elements

JGME editors look forward to reading medical education papers employing qualitative methods and perspectives. We trust these two editorials may be helpful to potential authors and readers, and we welcome your comments on this subject.

Joan Sargeant, PhD, is Professor in the Division of Medical Education, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Sample Size Policy for Qualitative Studies Using In-Depth Interviews

- Published: 12 September 2012

- Volume 41 , pages 1319–1320, ( 2012 )

Cite this article

- Shari L. Dworkin 1

299k Accesses

567 Citations

28 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In recent years, there has been an increase in submissions to the Journal that draw on qualitative research methods. This increase is welcome and indicates not only the interdisciplinarity embraced by the Journal (Zucker, 2002 ) but also its commitment to a wide array of methodologies.

For those who do select qualitative methods and use grounded theory and in-depth interviews in particular, there appear to be a lot of questions that authors have had recently about how to write a rigorous Method section. This topic will be addressed in a subsequent Editorial. At this time, however, the most common question we receive is: “How large does my sample size have to be?” and hence I would like to take this opportunity to answer this question by discussing relevant debates and then the policy of the Archives of Sexual Behavior . Footnote 1

The sample size used in qualitative research methods is often smaller than that used in quantitative research methods. This is because qualitative research methods are often concerned with garnering an in-depth understanding of a phenomenon or are focused on meaning (and heterogeneities in meaning )—which are often centered on the how and why of a particular issue, process, situation, subculture, scene or set of social interactions. In-depth interview work is not as concerned with making generalizations to a larger population of interest and does not tend to rely on hypothesis testing but rather is more inductive and emergent in its process. As such, the aim of grounded theory and in-depth interviews is to create “categories from the data and then to analyze relationships between categories” while attending to how the “lived experience” of research participants can be understood (Charmaz, 1990 , p. 1162).

There are several debates concerning what sample size is the right size for such endeavors. Most scholars argue that the concept of saturation is the most important factor to think about when mulling over sample size decisions in qualitative research (Mason, 2010 ). Saturation is defined by many as the point at which the data collection process no longer offers any new or relevant data. Another way to state this is that conceptual categories in a research project can be considered saturated “when gathering fresh data no longer sparks new theoretical insights, nor reveals new properties of your core theoretical categories” (Charmaz, 2006 , p. 113). Saturation depends on many factors and not all of them are under the researcher’s control. Some of these include: How homogenous or heterogeneous is the population being studied? What are the selection criteria? How much money is in the budget to carry out the study? Are there key stratifiers (e.g., conceptual, demographic) that are critical for an in-depth understanding of the topic being examined? What is the timeline that the researcher faces? How experienced is the researcher in being able to even determine when she or he has actually reached saturation (Charmaz, 2006 )? Is the author carrying out theoretical sampling and is, therefore, concerned with ensuring depth on relevant concepts and examining a range of concepts and characteristics that are deemed critical for emergent findings (Glaser & Strauss, 1967 ; Strauss & Corbin, 1994 , 2007 )?

While some experts in qualitative research avoid the topic of “how many” interviews “are enough,” there is indeed variability in what is suggested as a minimum. An extremely large number of articles, book chapters, and books recommend guidance and suggest anywhere from 5 to 50 participants as adequate. All of these pieces of work engage in nuanced debates when responding to the question of “how many” and frequently respond with a vague (and, actually, reasonable) “it depends.” Numerous factors are said to be important, including “the quality of data, the scope of the study, the nature of the topic, the amount of useful information obtained from each participant, the use of shadowed data, and the qualitative method and study designed used” (Morse, 2000 , p. 1). Others argue that the “how many” question can be the wrong question and that the rigor of the method “depends upon developing the range of relevant conceptual categories, saturating (filling, supporting, and providing repeated evidence for) those categories,” and fully explaining the data (Charmaz, 1990 ). Indeed, there have been countless conferences and conference sessions on these debates, reports written, and myriad publications are available as well (for a compilation of debates, see Baker & Edwards, 2012 ).

Taking all of these perspectives into account, the Archives of Sexual Behavior is putting forward a policy for authors in order to have more clarity on what is expected in terms of sample size for studies drawing on grounded theory and in-depth interviews. The policy of the Archives of Sexual Behavior will be that it adheres to the recommendation that 25–30 participants is the minimum sample size required to reach saturation and redundancy in grounded theory studies that use in-depth interviews. This number is considered adequate for publications in journals because it (1) may allow for thorough examination of the characteristics that address the research questions and to distinguish conceptual categories of interest, (2) maximizes the possibility that enough data have been collected to clarify relationships between conceptual categories and identify variation in processes, and (3) maximizes the chances that negative cases and hypothetical negative cases have been explored in the data (Charmaz, 2006 ; Morse, 1994 , 1995 ).

The Journal does not want to paradoxically and rigidly quantify sample size when the endeavor at hand is qualitative in nature and the debates on this matter are complex. However, we are providing this practical guidance. We want to ensure that more of our submissions have an adequate sample size so as to get closer to reaching the goal of saturation and redundancy across relevant characteristics and concepts. The current recommendation that is being put forward does not include any comment on other qualitative methodologies, such as content and textual analysis, participant observation, focus groups, case studies, clinical cases or mixed quantitative–qualitative methods. The current recommendation also does not apply to phenomenological studies or life history approaches. The current guidance is intended to offer one clear and consistent standard for research projects that use grounded theory and draw on in-depth interviews.

Editor’s note: Dr. Dworkin is an Associate Editor of the Journal and is responsible for qualitative submissions.

Baker, S. E., & Edwards, R. (2012). How many qualitative interviews is enough? National Center for Research Methods. Available at: http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/2273/ .

Charmaz, K. (1990). ‘Discovering’ chronic illness: Using grounded theory. Social Science and Medicine, 30 , 1161–1172.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis . London: Sage Publications.

Google Scholar

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research . Chicago: Aldine Publishing Co.

Mason, M. (2010). Sample size and saturation in PhD studies using qualitative interviews. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11 (3) [Article No. 8].

Morse, J. M. (1994). Designing funded qualitative research. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 220–235). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Morse, J. M. (1995). The significance of saturation. Qualitative Health Research, 5 , 147–149.

Article Google Scholar

Morse, J. M. (2000). Determining sample size. Qualitative Health Research, 10 , 3–5.

Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. M. (1994). Grounded theory methodology. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 273–285). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. M. (2007). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Zucker, K. J. (2002). From the Editor’s desk: Receiving the torch in the era of sexology’s renaissance. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 31 , 1–6.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, University of California at San Francisco, 3333 California St., LHTS #455, San Francisco, CA, 94118, USA

Shari L. Dworkin

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Shari L. Dworkin .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Dworkin, S.L. Sample Size Policy for Qualitative Studies Using In-Depth Interviews. Arch Sex Behav 41 , 1319–1320 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-0016-6

Download citation

Published : 12 September 2012

Issue Date : December 2012

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-0016-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

How Many Participants Do I Need? A Guide to Sample Estimation

As a qualitative mentor, a question I am frequently asked is, “How do I select the right sample size?”. There is no short answer or hard and fast rule for this. As with all things, there is nuance here, and much of this depends on other factors of your study. The purpose of this blog post is to provide you with strategies to select the appropriate sample for your qualitative study.

When students ask me what their sample needs to be, my first response is to look at the literature. In your literature review , you reviewed studies with methodologies similar to yours. Look at what others who have conducted studies like your own have used as samples. Start to model yours on these estimates. This will provide you with a good start to estimate your sample size.

The key to finding the right number of participants to recruit is to estimate the point at which you will reach data saturation, or when you are not gleaning new information as you add participants. Practically speaking, this means that you are not creating new codes or modifying your codebook anymore. Guest et al. (2006) found that in homogeneous studies using purposeful sampling, like many qualitative studies, 12 interviews should be sufficient to achieve data saturation.

However, there are qualifications here, including specifics of a data set as well as a researcher’s experience or tendency to lump or split categories. More recently, Hagaman and Wutich (2017) explored how many interviews were needed to identify metathemes, or those overarching themes, in qualitative research. In contrast to Guest’s (2006) work, and in a very different study, Hagaman and Wutich (2017) found that a larger sample of between 20-40 interviews was necessary to detect those metathemes.

You can see that between these two articles, there is variation in sample size and the number of participants necessary to reach data saturation. These should, however, provide some guidance and a starting point for thinking about your own sample. At a minimum, you probably want to begin with a sample of 12-15 participants. Plan to add more as needed if you do not believe you have reached saturation in that amount.

Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough?: An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods , 18(1), 59.82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903

Hagaman, A. K., & Wutich, A. (2017). How many interviews are enough to identify metathemes in multisited and cross-cultural research? Another perspective on Guest, Bunce, and Johnson’s (2006) landmark study. Field Methods , 29(1), 23-41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X16640447

We work with graduate students every day and know what it takes to get your research approved.

- Address committee feedback

- Roadmap to completion

- Understand your needs and timeframe

Find the right market research agencies, suppliers, platforms, and facilities by exploring the services and solutions that best match your needs

list of top MR Specialties

Browse all specialties

Browse Companies and Platforms

by Specialty

by Location

Browse Focus Group Facilities

Manage your listing

Follow a step-by-step guide with online chat support to create or manage your listing.

About Greenbook Directory

IIEX Conferences

Discover the future of insights at the Insight Innovation Exchange (IIEX) event closest to you

IIEX Virtual Events

Explore important trends, best practices, and innovative use cases without leaving your desk

Insights Tech Showcase

See the latest research tech in action during curated interactive demos from top vendors

Stay updated on what’s new in insights and learn about solutions to the challenges you face

Greenbook Future list

An esteemed awards program that supports and encourages the voices of emerging leaders in the insight community.

Insight Innovation Competition

Submit your innovation that could impact the insights and market research industry for the better.

Find your next position in the world's largest database of market research and data analytics jobs.

For Suppliers

Directory: Renew your listing

Directory: Create a listing

Event sponsorship

Get Recommended Program

Digital Ads

Content marketing

Ads in Reports

Podcasts sponsorship

Run your Webinar

Host a Tech Showcase

Future List Partnership

All services

Dana Stanley

Greenbook’s Chief Revenue Officer

What is the ideal Sample Size in Qualitative Research?

Presented by InterQ Research LLC

If we were to assemble a list of “most asked questions” that we receive from new clients, it’s this:

What is the ideal sample size in qualitative research? It’s a great question. A fantastic one. Because panel size does matter, though perhaps not as much as it does in quantitative research, when we’re aiming for a statistically meaningful number. Let’s explore this whole issue of panel size and what you should be looking for from participant panels when conducing qualitative research.

First off, look at quality versus quantity

Most likely, your company is looking for market research on a very specific audience type. B2B decision makers in human resources. Moms who live in the Midwest and have household incomes of $70k +. Teens who use Facebook more than 8 hours a week. Specificity is great thing, and without fail, every client we work with has a good grasp on their audience type. In qualitative panels, therefore, our first objective is to ensure that we’re recruiting people who meet each and every criteria line-item that we identify through quantitative research – and the criteria that our clients have pinpointed through their own research. Panel quality – having the right members in the panel – is so much more important than just pulling from a general population that falls within broad parameters. So first and foremost, we focus on recruiting the right respondents who match our audience specifications.

Study design in qualitative research

The type of qualitative study chosen is also one of the most important factors to consider when choosing sample size. In-depth interviews, focus groups, and ethnographic research are the most common methods used in qualitative market research, and the types of questions being studied have an equally important factor as the sample size chosen for these various methods. One of the most important principles to keep in mind – in all of these study designs – is the principle of saturation .

The objective of qualitative research (as compared to quantitative research) is to lessen discovery failure; in quantitative research, the objective is to reduce estimation error. Here’s where the principle of saturation comes in: With saturation, we say that the collection of new data isn’t giving the researcher any new additional insights into the issue being investigated. Qualitative seeks to uncover diverse opinions from the sample size, and one person’s opinion is enough to generate a code (part of the analysis framework). There is a point of diminishing return with larger samples; more data does not necessarily lead to more information – it simply leads to the same information being repeated (saturation). The goal, therefore, is to have a large enough sample size in a qualitative study that we’re able to uncover a range of opinions, but to cut the sample size off at the number where we’re getting saturation and repetitive data.

So … is there a magical number to aim for in qualitative research?

So now we’re back to our original question:

What is the ideal sample size in qualitative research?

We’ll answer it this time. Based on studies that have been done in academia on this very issue, 30 seems to be an ideal sample size for the most comprehensive view, but studies can have as little as 10 total participants and still yield extremely fruitful, and applicable, results. (This goes back to excellence in recruiting.)

Our general recommendation for in-depth interviews is a sample size of 30, if we’re building a study that includes similar segments within the population. A minimum size can be 10 – but again, this assumes the population integrity in recruiting.

Presented by

San Francisco, California

SOCIAL LINKS

Save to my lists

Featured expert

InterQ Research LLC

Full Service

Qualitative Research

Quantitative Research

Headquartered in Silicon Valley, InterQ delivers innovative market research for the tech industry, including qualitative, quantitative, and UX.

Why choose InterQ Research LLC

Tech industry specialist

B2B complex recruiting

Innovative methodologies

Big brand experience

Proven results

Learn more about InterQ Research LLC

Sign Up for Updates

Get content that matters, written by top insights industry experts, delivered right to your inbox.

67k+ subscribers

Weekly Newsletter

Greenbook Podcast

Event Updates

I agree to receive emails with insights-related content from Greenbook. I understand that I can manage my email preferences or unsubscribe at any time and that Greenbook protects my privacy under the General Data Protection Regulation.*

Get the latest updates from top market research, insights, and analytics experts delivered weekly to your inbox

Your guide for all things market research and consumer insights

Create a New Listing

Manage My Listing

Find Companies

Find Focus Group Facilities

Tech Showcases

GRIT Report

Expert Channels

Get in touch

Marketing Services

Future List

Publish With Us

Privacy policy

Cookie policy

Terms of use

Copyright © 2024 New York AMA Communication Services, Inc. All rights reserved. 234 5th Avenue, 2nd Floor, New York, NY 10001 | Phone: (212) 849-2752

Articles and blog posts

How to choose the right sample size for a qualitative study… and convince your supervisor that you know what you’re doing.

The question of how many participants are enough for a qualitative interview is, in my opinion, one of the most difficult questions to find an answer to in the literature. In fact, many authors who set out to find specific guidelines on the ideal sample size in qualitative research in the literature have also concluded that these are “virtually non-existent” (Guest, Bunce and Johnson, 2005: 59). This is particularly unfortunate, given that as a student planning to undertake your research, one of the things that will be most likely to be asked of you is to indicate, and justify, the number of participants in your planned study (this also includes your PhD proposal in which you are expected to give as much detail of the study as possible).

If you, then, turn to the literature, hoping to find advice from some of the great minds in research methodology, you are likely to find them evading the question and often hiding behind the term “saturation” which refers to the point at which gathering new data does not provide any new theoretical insights into the studied phenomenon. Although the concept of saturation may also be controversial, not least because the longer you explore, analyse and reflect on your data, you are always likely to find something “new” in it, it has come to be the guiding concept in establishing sample size in many qualitative studies. As Guest, Bunce and Johnson (2005) rightly point out, however

“although the idea of saturation is helpful at the conceptual level, it provides little practical guidance for estimating sample sizes for robust research prior to data collection”

(Guest, Bunce and Johnson, 2005: 59)

In other words – how in the world are we supposed to know when we will reach saturation PRIOR TO THE STUDY???

My advice is to use the available literature on the point of saturation and use it to justify your decision regarding the sample size. I did it for my PhD study, as I was growing frustrated that I really have to justify my decision to include 20 participants for an interview, even though I had read dozens of reports in which this number, or smaller, was common (“are you going to interview 20 participants just because others did?”). I just felt that this would be enough, and my common sense, which as I learnt throughout my PhD was the last thing that anyone would care about, was telling me the same thing. In order to support my decision with the literature, however, and considering that there are hardly any guidelines for establishing sample size , I decided to try to reach some sort of conclusion as to how many participants are enough to reach saturation and use it as my main argument for establishing the size of the sample.

So what does the literature tell us about this? Just as there is not single answer as to what sample size is sufficient, there is no single answer to the question of what sample size is sufficient to reach theoretical saturation . Such factors as heterogeneity of the studied population, the scope of the study and the adopted methods and their application (e.g. the length of the interviews) are believed, however, to have a central role in achieving this (cf. Baker and Edwards, 2012; Guest, Bunce and Johnson, 2005; Mason, 2010). Mason’s (2010) analysis of 560 PhD studies that adopted a qualitative interview as their main method revealed that the most common sample size in qualitative research is between 15 and 50 participants, with 20 being the average sample size in grounded theory studies (which was also the type of study I was undertaking). Guest, Bunce and Johnson (2005) used data from their own study to conclude that 88% of the codes they developed when analysing the data from 60 qualitative interviews were created by the time 12 interviews had been conducted.

These findings helped me in arguing that my initial sample size was going to be 20. “Given the detailed design of the study, which includes triangulation of the data and methods”, I argued, “I believe that this number will enable me to make valid judgements about the general trends emerging in the data”. I also stated that I am planning to recruit more participants, should the saturation not occur.

I hope that this article will help you in your quest to determine the sample size for your study and give you an idea of how you can go about arguing that it is a well thought-through decision. Do remember, however, that 20 participants may be enough for one study and not enough, or too many, for another. The point of this article was not to argue that 20 participants is a universally right number for a qualitative study, but rather to point to the fact that there is no such universally right number and that you are not the only one struggling to find guidelines regarding the interview sample size, as well as to put forward the concept of saturation as one of possible principles that may guide you in deciding how many participants to recruit for your study.

If you have any questions regarding this topic, comment below or send me a message through my Facebook page .

- UPDATE – see my Facebook page for my response to the question about the relevance of “saturation” for Phenomenological research

References:

Baker, S. & Edwards, R. (eds., 2012). How many qualitative interviews is enough? Expert voices and early career reflections on sampling and cases in qualitative research. National Centre for Research Methods , 1-42.

Guest, G., Bunce, A. & Johnson, L. (2005). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18 (1), 59-82.

Mason, M. (2010). Sample Size and Saturation in PhD Studies Using Qualitative Interviews. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11 (3).

Sample size for qualitative research

How large should the sample size be in a qualitative study? This article discusses the importance of sample size in qualitative research.

The risk of missing something important

Editor’s note: Peter DePaulo is an independent marketing research consultant and focus group moderator doing business as DePaulo Research Consulting, Montgomeryville, Pa.

In a qualitative research project, how large should the sample be? How many focus group respondents, individual depth interviews (IDIs), or ethnographic observations are needed?

We do have some informal rules of thumb. For example, Maria Krieger (in her white paper, “The Single Group Caveat,” Brain Tree Research & Consulting, 1991) advises that separate focus groups are needed for major segments such as men, women, and age groups, and that two or more groups are needed per segment because any one group may be idiosyncratic. Another guideline is to continue doing groups or IDIs until we seem to have reached a saturation point and are no longer hearing anything new.

Such rules are intuitive and reasonable, but they are not solidly grounded and do not really tell us what an optimal qualitative sample size may be. The approach proposed here gives specific answers based on a firm foundation.

First, the importance of sample size in qualitative research must be understood.

Size does matter, even for a qualitative sample

One might suppose that “N” (the number in the sample) simply is not very important in a qualitative project. After all, the effect of increasing N, as we learned in statistics class, is to reduce the sampling error (e.g., the +/- 3 percent variation in opinion polls with N = 1,000) in a quantitative estimate. Qualitative research normally is inappropriate for estimating quantities. So, we lack the old familiar reason for increasing sample size.

Nevertheless, in qualitative work, we do try to discover something. We may be seeking to uncover: the reasons why consumers may or may not be satisfied with a product; the product attributes that may be important to users; possible consumer perceptions of celebrity spokespersons; the various problems that consumers may experience with our brand; or other kinds of insights. (For lack of a better term, I will use the word “perception” to refer to a reason, need, attribute, problem, or whatever the qualitative project is intended to uncover.) It would be up to a subsequent quantitative study to estimate, with statistical precision, how important or prevalent each perception actually is.

The key point is this: Our qualitative sample must be big enough to assure that we are likely to hear most or all of the perceptions that might be important. Within a target market, different customers may have diverse perceptions. Therefore, the smaller the sample size, the narrower the range of perceptions we may hear. On the positive side, the larger the sample size, the less likely it is that we would fail to discover a perception that we would have wanted to know. In other words, our objective in designing qualitative research is to reduce the chances of discovery failure, as opposed to reducing (quantitative) estimation error.

Discovery failure can be serious

What might go wrong if a qualitative project fails to uncover an actionable perception (or attribute, opinion, need, experience, etc.)? Here are some possibilities:

- A source of dissatisfaction is not discovered - and not corrected. In highly competitive industries, even a small incidence of dissatisfaction could dent the bottom line.

- In the qualitative testing of an advertisement, a copy point that offends a small but vocal subgroup of the market is not discovered until a public-relations fiasco erupts.

- When qualitative procedures are used to pre-test a quantitative questionnaire, an undiscovered ambiguity in the wording of a question may mean that some of the subsequent quantitative respondents give invalid responses. Thus, qualitative discovery failure eventually can result in quantitative estimation error due to respondent miscomprehension.

Therefore, size does matter in a qualitative sample, though for a different reason that in a quant sample. The following example shows how the risk of discover failure may be easy to overlook even when it is formidable.

Example of the risk being higher than expected

The managers of a medical clinic (name withheld) had heard favorable anecdotal feedback about the clinic’s quality, but wanted an independent evaluation through research. The budget permitted only one focus group with 10 clinic patients. All 10 respondents clearly were satisfied with the clinic, and group discussion did not reverse these views.

Did we miss anything as a result of interviewing only 10? Suppose, for example that the clinic had a moody staff member who, unbeknownst to management, was aggravating one in 10 clinic patients. Also, suppose that management would have wanted to discover anything that affects the satisfaction at least 10 percent of customers. If there really was an unknown satisfaction problem with a 10 percent incidence, then what was the chance that our sample of 10 happened to miss it? That is, what is the probability that no member of the subgroup defined as those who experienced the staffer in a bad mood happened to get into the sample?

At first thought, the answer might seem to be “not much” chance of missing the problem. The hypothetical incidence is “one in 10,” and we did indeed interview 10 patients. Actually, the probability that our sample failed to include a patient aggravated by the moody staffer turns out to be just over one in three (0.349 to be exact). This probability is simple to calculate: Consider that the chance of any one customer selected at random not being a member of the 10 percent (aggravated) subgroup is 0.9 (i.e., a nine in 10 chance). Next, consider that the chance of failing to reach anyone from the 10 percent subgroup twice in a row (by selecting two customers at random) is 0.9 X 0.9, or 0.9 to the second power, which equals 0.81. Now, it should be clear that the chance of missing the subgroup 10 times in a row (i.e., when drawing a sample of 10) is 0.9 to the tenth power, which is 0.35. Thus, there is a 35 percent chance that our sample of 10 would have “missed” patients who experienced the staffer in a bad mood. Put another way, just over one in three random samples of 10 will miss an experience or characteristic with an incidence of 10 percent.

This seems counter-intuitively high, even to quant researchers to whom I have shown this analysis. Perhaps people implicitly assume the fallacy that if something has an overall frequency of one in N, then it is almost sure to appear in N chances.

Basing the decision on calculated probabilities

So, how can we figure the sample size needed to reduce the risk as much as we want? I am proposing two ways. One would be based on calculated probabilities like those in the table above, which was created by repeating the power calculations described above for various incidences and sample sizes. The client and researcher would peruse the table and select a sample size that is affordable yet reduces the risk of discover failure to a tolerable level.

For example, if the research team would want to discover a perception with an incidence as low as 10 percent of the population, and if the team wanted to reduce the risk of missing that subgroup to less than 5 percent, then a sample of N=30 would suffice, assuming random selection. (To be exact, the risk shown in the table is .042, or 4.2 percent.) This is analogous to having 95 percent confidence in being able to discover a perception with a 10 percent incidence. Remember, however, that we are expressing the confidence in uncovering a qualitative insight - as opposed to the usual quantitative notion of “confidence” in estimating a proportion or mean plus or minus the measurement error.

If the team wants to be more conservative and reduce the risk of missing the one-in-10 subgroup to less than 1 percent (i.e., 99 percent confidence), then a sample of nearly 50 would be needed. This would reduce the risk to nearly 0.005 (see table).

What about non-randomness?

Of course, the table assumes random sampling, and qualitative samples often are not randomly drawn. Typically, focus groups are recruited from facility databases, which are not guaranteed to be strictly representative of the local adult population, and factors such as refusals (also a problem in quantitative surveys, by the way) further compromise the randomness of the sample.

Unfortunately, nothing can be done about subgroups that are impossible to reach, such as people who, for whatever reason, never cooperate when recruiters call. Nevertheless, we can still sample those subgroups who are less likely to be reached as long as the recruiter’s call has some chance of being received favorably, for example, people who are home only half as often as the average target customer but will still answer the call and accept our invitation to participate. We can compensate for their reduced likelihood of being contacted by thinking of their reachable incidence as half of their actual incidence. Specifically, if we wanted to allocate enough budget to reach a 10 percent subgroup even if it is twice as hard to reach, then we would suppose that their reachable incidence is as low as 5 percent, and look at the 5 percent row in the table. If, for instance, we wanted to be very conservative, we would recruit 100 respondents, resulting in less than a 1 percent chance - .006, to be exact - of missing a 5 percent subgroup (or a 10 percent subgroup that behaves like a 5 percent subgroup in likelihood of being reached).

An approach based on actual qualitative findings

The other way of figuring an appropriate sample size would be to consider the findings of a pair of actual qualitative studies reported by Abbie Griffin and John Hauser in an article, “The Voice of the Customer” (Marketing Science, Winter 1993). These researchers looked at the number of customer needs uncovered by various numbers of focus groups and in-depth interviews.

In one of the two studies, two-hour focus groups and one-hour in-depth interviews (IDIs) were conducted with users of a complex piece of office equipment. In the other study, IDIs were conducted with consumers of coolers, knapsacks, and other portable means of storing food. Both studies looked at the number of needs (attributes, broadly defined) uncovered for each product category. Using mathematical extrapolations, the authors hypothesized that 20-30 IDIs are needed to uncover 90-95 percent of all customer needs for the product categories studied.

As with typical learning curves, there were diminishing returns in the sense that fewer new (non-duplicate) needs were uncovered with each additional IDI. It seemed that few additional needs would be uncovered after 30 IDIs. This is consistent with the probability table (shown earlier), which shows that perceptions of all but the smallest market segments are likely to be found in samples of 30 or less.

In the office equipment study, one two-hour focus group was no better than two one-hour IDIs, implying that “group synergies [did] not seem to be present” in the focus groups. The study also suggested that multiple analysts are needed to uncover the broadest range of needs.

These studies were conducted within the context of quality function deployment, where, according to the authors, 200-400 “customer needs” are usually identified. It is not clear how the results might generalize to other qualitative applications.

Nevertheless, if one were to base a sample-size decision on the Griffin and Hauser results, the implication would be to conduct 20-30 IDIs and to arrange for multiple analysts to look for insights in the data. Perhaps backroom observers could, to some extent, serve as additional analysts by taking notes while watching the groups or interviews. The observers’ notes might contain some insights that the moderator overlooks, thus helping to minimize the chances of missing something important.

N=30 as a starting point for planning

Neither the calculation of probabilities in the prior table nor the empirical rationale of Griffin and Hauser is assured of being the last word on qualitative sample size. There might be other ways of figuring the number of IDIs, groups, or ethnographic observations needed to avoid missing something important.

Until the definitive answer is provided, perhaps an N of 30 respondents is a reasonable starting point for deciding the qualitative sample size that can reveal the full range (or nearly the full range) of potentially important customer perceptions. An N of 30 reduces the probability of missing a perception with a 10 percent-incidence to less than 5 percent (assuming random sampling), and it is the upper end of the range found by Griffin and Hauser. If the budget is limited, we might reduce the N below 30, but the client must understand the increased risks of missing perceptions that may be worth knowing. If the stakes and budget are high enough, we might go with a larger sample in order to ensure that smaller (or harder to reach) subgroups are still likely to be represented.

If focus groups are desired, and we want to count each respondent separately toward the N we choose (e.g., getting an N of 30 from three groups with 10 respondents in each), then it is important for every respondent to have sufficient air time on the key issues. Using mini groups instead of traditional-size groups could help achieve this objective. Also, it is critical for the moderator to control dominators and bring out the shy people, lest the distinctive perceptions of less-talkative customers are missed.

Across segments or within each one?

A complication arises when we are separately exploring different customer segments, such as men versus women, different age groups, or consumers in different geographic regions. In the case of gender and a desired N of 30, for example, do we need 30 in total (15 males plus 15 females) or do we really need to interview 60 people (30 males plus 30 females)? This is a judgment call, which would depend on the researchers’ belief in the extent to which customer perceptions may vary from segment to segment. Of course, it may also depend on budget. To play it safe, each segment should have its own N large enough so that appreciable subgroups within the segment are likely to be represented in the sample.

What if we only want the “typical” or “majority” view?

For some purportedly qualitative studies, the stated or implied purpose may be to get a sense of how customers feel overall about the issue under study. For example, the client may want to know whether customers “generally” respond favorably to a new concept. In that case, it might be argued that we need not be concerned about having a sample large enough to make certain that we discover minority viewpoints, because the client is interested only in how “most” customers react.

The problem with this agenda is that the “qualitative” research would have an implicit quantitative purpose: to reveal the attribute or point of view held by more than 50 percent of the population. If, indeed, we observe what “most” qualitative respondents say or do and then infer that we have found the majority reaction, we are doing more than “discovering” that reaction: We are implicitly estimating its incidence at more than 50 percent.

The approach I propose makes no such inferences. If we find that only one respondent in a sample of 30 holds a particular view, we make no assumption that it represents a 10 percent population incidence, although, as discussed later, it might be that high. The actual population incidence is likely to be closer to 3.3 percent (1/30) than to 10 percent. Moreover, to keep the study qualitative, we should not say that we have estimated the incidence at all. We only want to ensure that if there is an attribute or opinion with an incidence as low as 10 percent, we are likely to have at least one respondent to speak for it - and a sample of 30 will probably do the job.

If we do want to draw quantitative inferences from a qualitative procedure (and, normally, this is ill advised), then this paper does not apply. Instead, the researchers should use the usual calculations for setting a quantitative sample size at which the estimation error resulting from random sampling variations would be acceptably low.

Keeping qualitative pure

Whenever I present this sample-size proposal, someone usually objects that I am somehow “quantifying qualitative.” On the contrary, estimating the chances of missing a potentially important perception is completely different from estimating the percent of a target population who hold a particular perception. To put it another way, calculating the odds of missing a perception with a hypothetical incidence does not quantify the incidences of those perceptions that we actually do uncover.

Therefore, qualitative consultants should not be reluctant to talk about the probability of missing something important. In so doing, they will not lose their identity as qualitative researchers, nor will they need any “high math.” Moreover, by distinguishing between discovery failure and estimation error, researchers can help their clients fully understand the difference between qualitative and quantitative purposes. In short, the approach I propose is intended to ensure that qualitative will accomplish what it does best - to discover (not measure) potentially important insights.

Qualitative research with children: Five strategies to gain parental trust Related Categories: Recruiting-Qualitative, Qualitative Research, Focus Groups Recruiting-Qualitative, Qualitative Research, Focus Groups, Children, Parents, Research Industry

From the Publisher November 1987 Related Categories: Recruiting-Qualitative, Qualitative Research, Focus Groups Recruiting-Qualitative, Qualitative Research, Focus Groups, Focus Group-Moderating, Incentive Payment & Processing, Pharmaceutical Products

24 Top Qualitative Research Companies 2021 Related Categories: Recruiting-Qualitative, Qualitative Research, Focus Groups Recruiting-Qualitative, Qualitative Research, Focus Groups, Consumer Research, Consumers, Ethnographic Research, Focus Group-Facilities, Focus Group-Moderating, Focus Group-Online, Focus Group-Transcriptions, One-on-One (Depth) Interviews, Qualitative-Online, Software-Online Qualitative, Software-Qualitative, Transcription Services

How to get the story behind the numbers in a fast, cost-effective way Related Categories: Recruiting-Qualitative, Qualitative Research, Focus Groups Recruiting-Qualitative, Qualitative Research, Focus Groups, Focus Group-Moderating, Focus Group-Online, One-on-One (Depth) Interviews, Qualitative-Online, Software-Online Qualitative, Software-Qualitative, Consumer Research, Consumers, Quantitative Research, Video Recording

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 21 November 2018

Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period

- Konstantina Vasileiou ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5047-3920 1 ,

- Julie Barnett 1 ,

- Susan Thorpe 2 &

- Terry Young 3

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 18 , Article number: 148 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

740k Accesses

1189 Citations

172 Altmetric

Metrics details

Choosing a suitable sample size in qualitative research is an area of conceptual debate and practical uncertainty. That sample size principles, guidelines and tools have been developed to enable researchers to set, and justify the acceptability of, their sample size is an indication that the issue constitutes an important marker of the quality of qualitative research. Nevertheless, research shows that sample size sufficiency reporting is often poor, if not absent, across a range of disciplinary fields.

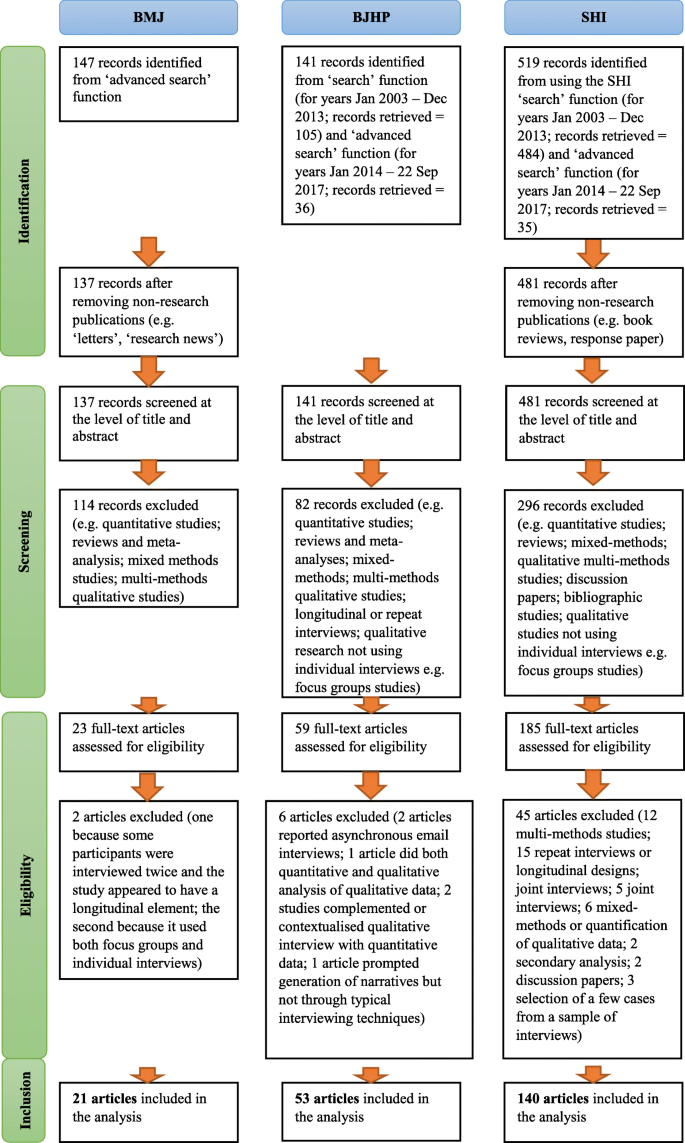

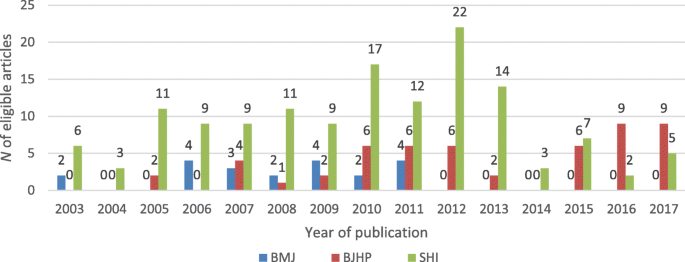

A systematic analysis of single-interview-per-participant designs within three health-related journals from the disciplines of psychology, sociology and medicine, over a 15-year period, was conducted to examine whether and how sample sizes were justified and how sample size was characterised and discussed by authors. Data pertinent to sample size were extracted and analysed using qualitative and quantitative analytic techniques.

Our findings demonstrate that provision of sample size justifications in qualitative health research is limited; is not contingent on the number of interviews; and relates to the journal of publication. Defence of sample size was most frequently supported across all three journals with reference to the principle of saturation and to pragmatic considerations. Qualitative sample sizes were predominantly – and often without justification – characterised as insufficient (i.e., ‘small’) and discussed in the context of study limitations. Sample size insufficiency was seen to threaten the validity and generalizability of studies’ results, with the latter being frequently conceived in nomothetic terms.

Conclusions

We recommend, firstly, that qualitative health researchers be more transparent about evaluations of their sample size sufficiency, situating these within broader and more encompassing assessments of data adequacy . Secondly, we invite researchers critically to consider how saturation parameters found in prior methodological studies and sample size community norms might best inform, and apply to, their own project and encourage that data adequacy is best appraised with reference to features that are intrinsic to the study at hand. Finally, those reviewing papers have a vital role in supporting and encouraging transparent study-specific reporting.

Peer Review reports

Sample adequacy in qualitative inquiry pertains to the appropriateness of the sample composition and size . It is an important consideration in evaluations of the quality and trustworthiness of much qualitative research [ 1 ] and is implicated – particularly for research that is situated within a post-positivist tradition and retains a degree of commitment to realist ontological premises – in appraisals of validity and generalizability [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ].

Samples in qualitative research tend to be small in order to support the depth of case-oriented analysis that is fundamental to this mode of inquiry [ 5 ]. Additionally, qualitative samples are purposive, that is, selected by virtue of their capacity to provide richly-textured information, relevant to the phenomenon under investigation. As a result, purposive sampling [ 6 , 7 ] – as opposed to probability sampling employed in quantitative research – selects ‘information-rich’ cases [ 8 ]. Indeed, recent research demonstrates the greater efficiency of purposive sampling compared to random sampling in qualitative studies [ 9 ], supporting related assertions long put forward by qualitative methodologists.