When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

How to Write a Peer Review

When you write a peer review for a manuscript, what should you include in your comments? What should you leave out? And how should the review be formatted?

This guide provides quick tips for writing and organizing your reviewer report.

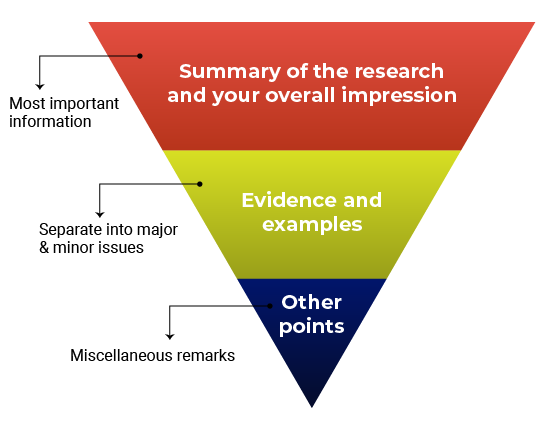

Review Outline

Use an outline for your reviewer report so it’s easy for the editors and author to follow. This will also help you keep your comments organized.

Think about structuring your review like an inverted pyramid. Put the most important information at the top, followed by details and examples in the center, and any additional points at the very bottom.

Here’s how your outline might look:

1. Summary of the research and your overall impression

In your own words, summarize what the manuscript claims to report. This shows the editor how you interpreted the manuscript and will highlight any major differences in perspective between you and the other reviewers. Give an overview of the manuscript’s strengths and weaknesses. Think about this as your “take-home” message for the editors. End this section with your recommended course of action.

2. Discussion of specific areas for improvement

It’s helpful to divide this section into two parts: one for major issues and one for minor issues. Within each section, you can talk about the biggest issues first or go systematically figure-by-figure or claim-by-claim. Number each item so that your points are easy to follow (this will also make it easier for the authors to respond to each point). Refer to specific lines, pages, sections, or figure and table numbers so the authors (and editors) know exactly what you’re talking about.

Major vs. minor issues

What’s the difference between a major and minor issue? Major issues should consist of the essential points the authors need to address before the manuscript can proceed. Make sure you focus on what is fundamental for the current study . In other words, it’s not helpful to recommend additional work that would be considered the “next step” in the study. Minor issues are still important but typically will not affect the overall conclusions of the manuscript. Here are some examples of what would might go in the “minor” category:

- Missing references (but depending on what is missing, this could also be a major issue)

- Technical clarifications (e.g., the authors should clarify how a reagent works)

- Data presentation (e.g., the authors should present p-values differently)

- Typos, spelling, grammar, and phrasing issues

3. Any other points

Confidential comments for the editors.

Some journals have a space for reviewers to enter confidential comments about the manuscript. Use this space to mention concerns about the submission that you’d want the editors to consider before sharing your feedback with the authors, such as concerns about ethical guidelines or language quality. Any serious issues should be raised directly and immediately with the journal as well.

This section is also where you will disclose any potentially competing interests, and mention whether you’re willing to look at a revised version of the manuscript.

Do not use this space to critique the manuscript, since comments entered here will not be passed along to the authors. If you’re not sure what should go in the confidential comments, read the reviewer instructions or check with the journal first before submitting your review. If you are reviewing for a journal that does not offer a space for confidential comments, consider writing to the editorial office directly with your concerns.

Get this outline in a template

Giving Feedback

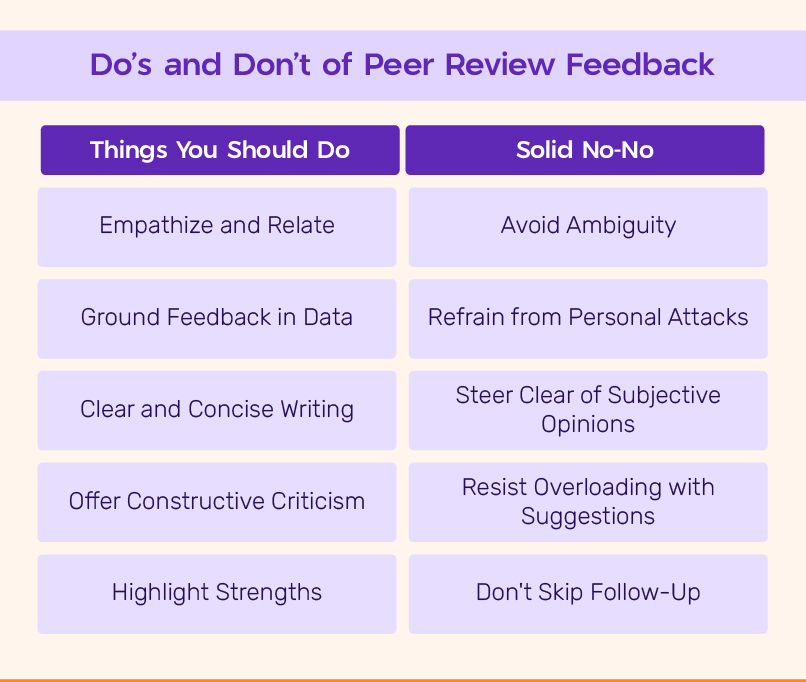

Giving feedback is hard. Giving effective feedback can be even more challenging. Remember that your ultimate goal is to discuss what the authors would need to do in order to qualify for publication. The point is not to nitpick every piece of the manuscript. Your focus should be on providing constructive and critical feedback that the authors can use to improve their study.

If you’ve ever had your own work reviewed, you already know that it’s not always easy to receive feedback. Follow the golden rule: Write the type of review you’d want to receive if you were the author. Even if you decide not to identify yourself in the review, you should write comments that you would be comfortable signing your name to.

In your comments, use phrases like “ the authors’ discussion of X” instead of “ your discussion of X .” This will depersonalize the feedback and keep the focus on the manuscript instead of the authors.

General guidelines for effective feedback

- Justify your recommendation with concrete evidence and specific examples.

- Be specific so the authors know what they need to do to improve.

- Be thorough. This might be the only time you read the manuscript.

- Be professional and respectful. The authors will be reading these comments too.

- Remember to say what you liked about the manuscript!

Don’t

- Recommend additional experiments or unnecessary elements that are out of scope for the study or for the journal criteria.

- Tell the authors exactly how to revise their manuscript—you don’t need to do their work for them.

- Use the review to promote your own research or hypotheses.

- Focus on typos and grammar. If the manuscript needs significant editing for language and writing quality, just mention this in your comments.

- Submit your review without proofreading it and checking everything one more time.

Before and After: Sample Reviewer Comments

Keeping in mind the guidelines above, how do you put your thoughts into words? Here are some sample “before” and “after” reviewer comments

✗ Before

“The authors appear to have no idea what they are talking about. I don’t think they have read any of the literature on this topic.”

✓ After

“The study fails to address how the findings relate to previous research in this area. The authors should rewrite their Introduction and Discussion to reference the related literature, especially recently published work such as Darwin et al.”

“The writing is so bad, it is practically unreadable. I could barely bring myself to finish it.”

“While the study appears to be sound, the language is unclear, making it difficult to follow. I advise the authors work with a writing coach or copyeditor to improve the flow and readability of the text.”

“It’s obvious that this type of experiment should have been included. I have no idea why the authors didn’t use it. This is a big mistake.”

“The authors are off to a good start, however, this study requires additional experiments, particularly [type of experiment]. Alternatively, the authors should include more information that clarifies and justifies their choice of methods.”

Suggested Language for Tricky Situations

You might find yourself in a situation where you’re not sure how to explain the problem or provide feedback in a constructive and respectful way. Here is some suggested language for common issues you might experience.

What you think : The manuscript is fatally flawed. What you could say: “The study does not appear to be sound” or “the authors have missed something crucial”.

What you think : You don’t completely understand the manuscript. What you could say : “The authors should clarify the following sections to avoid confusion…”

What you think : The technical details don’t make sense. What you could say : “The technical details should be expanded and clarified to ensure that readers understand exactly what the researchers studied.”

What you think: The writing is terrible. What you could say : “The authors should revise the language to improve readability.”

What you think : The authors have over-interpreted the findings. What you could say : “The authors aim to demonstrate [XYZ], however, the data does not fully support this conclusion. Specifically…”

What does a good review look like?

Check out the peer review examples at F1000 Research to see how other reviewers write up their reports and give constructive feedback to authors.

Time to Submit the Review!

Be sure you turn in your report on time. Need an extension? Tell the journal so that they know what to expect. If you need a lot of extra time, the journal might need to contact other reviewers or notify the author about the delay.

Tip: Building a relationship with an editor

You’ll be more likely to be asked to review again if you provide high-quality feedback and if you turn in the review on time. Especially if it’s your first review for a journal, it’s important to show that you are reliable. Prove yourself once and you’ll get asked to review again!

- Getting started as a reviewer

- Responding to an invitation

- Reading a manuscript

- Writing a peer review

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

Published on December 17, 2021 by Tegan George . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Peer review, sometimes referred to as refereeing , is the process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Using strict criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decides whether to accept each submission for publication.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to the stringent process they go through before publication.

There are various types of peer review. The main difference between them is to what extent the authors, reviewers, and editors know each other’s identities. The most common types are:

- Single-blind review

- Double-blind review

- Triple-blind review

Collaborative review

Open review.

Relatedly, peer assessment is a process where your peers provide you with feedback on something you’ve written, based on a set of criteria or benchmarks from an instructor. They then give constructive feedback, compliments, or guidance to help you improve your draft.

Table of contents

What is the purpose of peer review, types of peer review, the peer review process, providing feedback to your peers, peer review example, advantages of peer review, criticisms of peer review, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about peer reviews.

Many academic fields use peer review, largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the manuscript. For this reason, academic journals are among the most credible sources you can refer to.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

Peer assessment is often used in the classroom as a pedagogical tool. Both receiving feedback and providing it are thought to enhance the learning process, helping students think critically and collaboratively.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Depending on the journal, there are several types of peer review.

Single-blind peer review

The most common type of peer review is single-blind (or single anonymized) review . Here, the names of the reviewers are not known by the author.

While this gives the reviewers the ability to give feedback without the possibility of interference from the author, there has been substantial criticism of this method in the last few years. Many argue that single-blind reviewing can lead to poaching or intellectual theft or that anonymized comments cause reviewers to be too harsh.

Double-blind peer review

In double-blind (or double anonymized) review , both the author and the reviewers are anonymous.

Arguments for double-blind review highlight that this mitigates any risk of prejudice on the side of the reviewer, while protecting the nature of the process. In theory, it also leads to manuscripts being published on merit rather than on the reputation of the author.

Triple-blind peer review

While triple-blind (or triple anonymized) review —where the identities of the author, reviewers, and editors are all anonymized—does exist, it is difficult to carry out in practice.

Proponents of adopting triple-blind review for journal submissions argue that it minimizes potential conflicts of interest and biases. However, ensuring anonymity is logistically challenging, and current editing software is not always able to fully anonymize everyone involved in the process.

In collaborative review , authors and reviewers interact with each other directly throughout the process. However, the identity of the reviewer is not known to the author. This gives all parties the opportunity to resolve any inconsistencies or contradictions in real time, and provides them a rich forum for discussion. It can mitigate the need for multiple rounds of editing and minimize back-and-forth.

Collaborative review can be time- and resource-intensive for the journal, however. For these collaborations to occur, there has to be a set system in place, often a technological platform, with staff monitoring and fixing any bugs or glitches.

Lastly, in open review , all parties know each other’s identities throughout the process. Often, open review can also include feedback from a larger audience, such as an online forum, or reviewer feedback included as part of the final published product.

While many argue that greater transparency prevents plagiarism or unnecessary harshness, there is also concern about the quality of future scholarship if reviewers feel they have to censor their comments.

In general, the peer review process includes the following steps:

- First, the author submits the manuscript to the editor.

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to the author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

In an effort to be transparent, many journals are now disclosing who reviewed each article in the published product. There are also increasing opportunities for collaboration and feedback, with some journals allowing open communication between reviewers and authors.

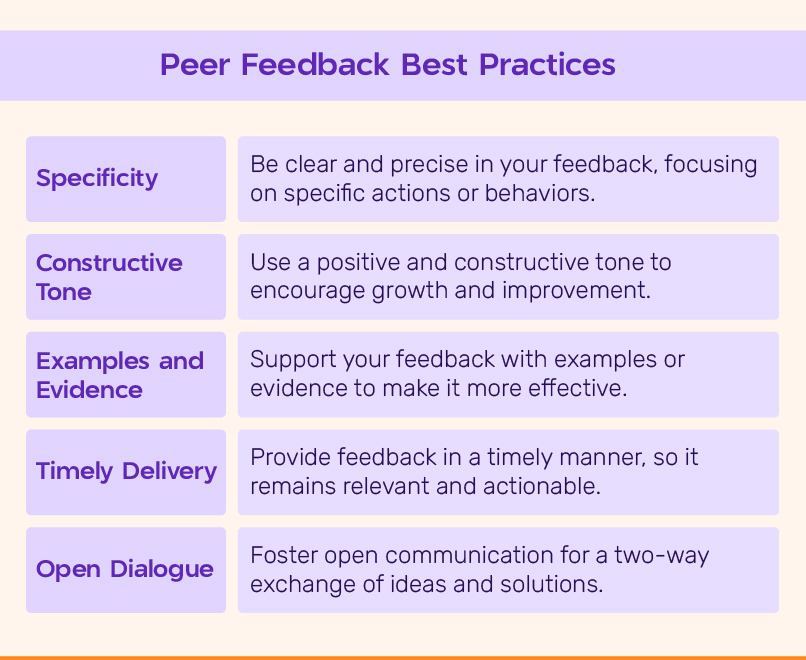

It can seem daunting at first to conduct a peer review or peer assessment. If you’re not sure where to start, there are several best practices you can use.

Summarize the argument in your own words

Summarizing the main argument helps the author see how their argument is interpreted by readers, and gives you a jumping-off point for providing feedback. If you’re having trouble doing this, it’s a sign that the argument needs to be clearer, more concise, or worded differently.

If the author sees that you’ve interpreted their argument differently than they intended, they have an opportunity to address any misunderstandings when they get the manuscript back.

Separate your feedback into major and minor issues

It can be challenging to keep feedback organized. One strategy is to start out with any major issues and then flow into the more minor points. It’s often helpful to keep your feedback in a numbered list, so the author has concrete points to refer back to.

Major issues typically consist of any problems with the style, flow, or key points of the manuscript. Minor issues include spelling errors, citation errors, or other smaller, easy-to-apply feedback.

Tip: Try not to focus too much on the minor issues. If the manuscript has a lot of typos, consider making a note that the author should address spelling and grammar issues, rather than going through and fixing each one.

The best feedback you can provide is anything that helps them strengthen their argument or resolve major stylistic issues.

Give the type of feedback that you would like to receive

No one likes being criticized, and it can be difficult to give honest feedback without sounding overly harsh or critical. One strategy you can use here is the “compliment sandwich,” where you “sandwich” your constructive criticism between two compliments.

Be sure you are giving concrete, actionable feedback that will help the author submit a successful final draft. While you shouldn’t tell them exactly what they should do, your feedback should help them resolve any issues they may have overlooked.

As a rule of thumb, your feedback should be:

- Easy to understand

- Constructive

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Below is a brief annotated research example. You can view examples of peer feedback by hovering over the highlighted sections.

Influence of phone use on sleep

Studies show that teens from the US are getting less sleep than they were a decade ago (Johnson, 2019) . On average, teens only slept for 6 hours a night in 2021, compared to 8 hours a night in 2011. Johnson mentions several potential causes, such as increased anxiety, changed diets, and increased phone use.

The current study focuses on the effect phone use before bedtime has on the number of hours of sleep teens are getting.

For this study, a sample of 300 teens was recruited using social media, such as Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat. The first week, all teens were allowed to use their phone the way they normally would, in order to obtain a baseline.

The sample was then divided into 3 groups:

- Group 1 was not allowed to use their phone before bedtime.

- Group 2 used their phone for 1 hour before bedtime.

- Group 3 used their phone for 3 hours before bedtime.

All participants were asked to go to sleep around 10 p.m. to control for variation in bedtime . In the morning, their Fitbit showed the number of hours they’d slept. They kept track of these numbers themselves for 1 week.

Two independent t tests were used in order to compare Group 1 and Group 2, and Group 1 and Group 3. The first t test showed no significant difference ( p > .05) between the number of hours for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 2 ( M = 7.0, SD = 0.8). The second t test showed a significant difference ( p < .01) between the average difference for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 3 ( M = 6.1, SD = 1.5).

This shows that teens sleep fewer hours a night if they use their phone for over an hour before bedtime, compared to teens who use their phone for 0 to 1 hours.

Peer review is an established and hallowed process in academia, dating back hundreds of years. It provides various fields of study with metrics, expectations, and guidance to ensure published work is consistent with predetermined standards.

- Protects the quality of published research

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. Any content that raises red flags for reviewers can be closely examined in the review stage, preventing plagiarized or duplicated research from being published.

- Gives you access to feedback from experts in your field

Peer review represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field and to improve your writing through their feedback and guidance. Experts with knowledge about your subject matter can give you feedback on both style and content, and they may also suggest avenues for further research that you hadn’t yet considered.

- Helps you identify any weaknesses in your argument

Peer review acts as a first defense, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process. This way, you’ll end up with a more robust, more cohesive article.

While peer review is a widely accepted metric for credibility, it’s not without its drawbacks.

- Reviewer bias

The more transparent double-blind system is not yet very common, which can lead to bias in reviewing. A common criticism is that an excellent paper by a new researcher may be declined, while an objectively lower-quality submission by an established researcher would be accepted.

- Delays in publication

The thoroughness of the peer review process can lead to significant delays in publishing time. Research that was current at the time of submission may not be as current by the time it’s published. There is also high risk of publication bias , where journals are more likely to publish studies with positive findings than studies with negative findings.

- Risk of human error

By its very nature, peer review carries a risk of human error. In particular, falsification often cannot be detected, given that reviewers would have to replicate entire experiments to ensure the validity of results.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Thematic analysis

- Discourse analysis

- Cohort study

- Ethnography

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Conformity bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Availability heuristic

- Attrition bias

- Social desirability bias

Peer review is a process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Utilizing rigorous criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decide whether to accept each submission for publication. For this reason, academic journals are often considered among the most credible sources you can use in a research project– provided that the journal itself is trustworthy and well-regarded.

In general, the peer review process follows the following steps:

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits, and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. It also represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field. It acts as a first defense, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to this stringent process they go through before publication.

Many academic fields use peer review , largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the published manuscript.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

A credible source should pass the CRAAP test and follow these guidelines:

- The information should be up to date and current.

- The author and publication should be a trusted authority on the subject you are researching.

- The sources the author cited should be easy to find, clear, and unbiased.

- For a web source, the URL and layout should signify that it is trustworthy.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, June 22). What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved March 20, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/peer-review/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what are credible sources & how to spot them | examples, ethical considerations in research | types & examples, applying the craap test & evaluating sources, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

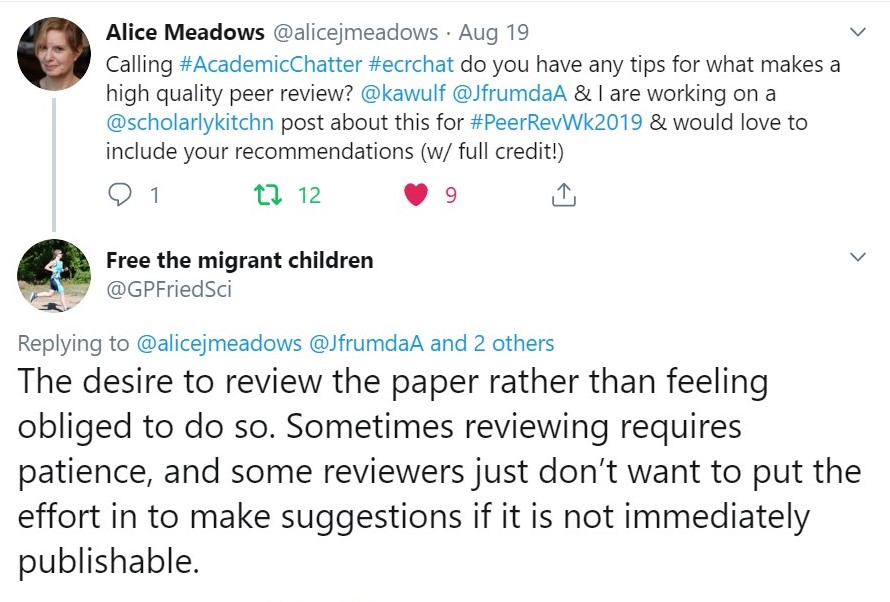

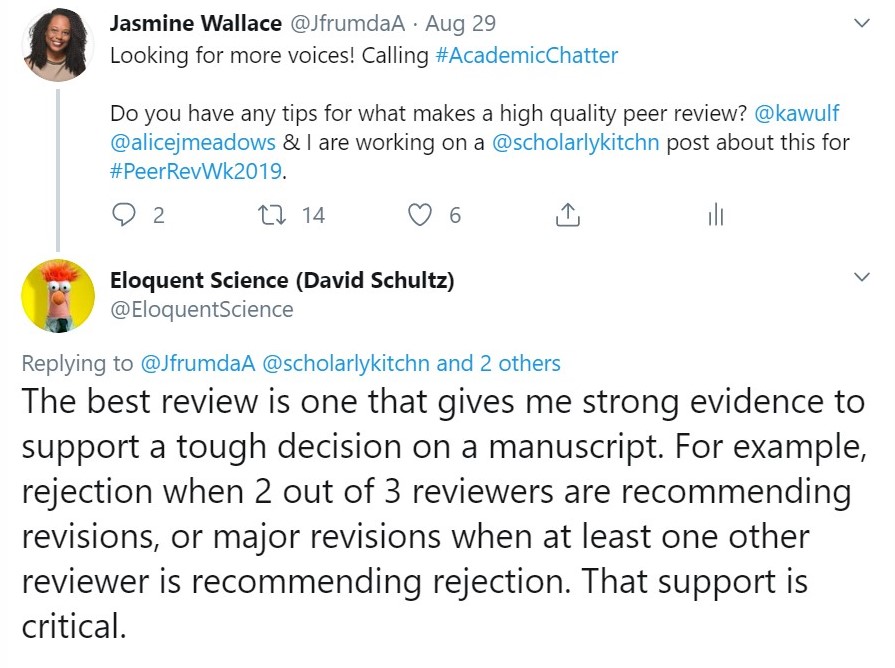

What makes a good or a bad peer review? Tips for excelling at reviewing

Dr rebecca sear tells us her opinion on what makes a good or bad review, and how new reviewers can succeed in this process..

Following on from her previous post on ‘ Tips for good practice in peer review ’, Dr Rebecca Sear , Head of the Department of Population Health at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and Editorial Board member of Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B , has given us some further thoughts about what makes a good or bad review, and how new reviewers can succeed in this process.

You’ve accepted your first peer review request, thoroughly read the paper, and are now sitting in front of a blank computer screen wondering what your peer review should look like. Here are my tips.

What does a good peer review look like?

1. Start with a (very) brief summary of the paper. This is a useful exercise for both reviewers and authors. If you struggle to summarise what the paper is about, that suggests the authors need to improve the clarity of their writing. It also lets the authors know what a reader took from their paper – which may not be what they intended!

2. Next, give the Editor an overview of what you thought of the paper. You will typically have to provide a recommendation (e.g. accept, revise or reject), but in the review itself you should give a summary of your reasons for this recommendation. Some examples:

- ‘the data appear appropriate for testing the authors’ hypothesis but I have some concerns about the methods. If these can be fixed, then this should become a useful contribution to the literature’.

- ‘the authors’ have a clear research question and use appropriate methods, but their data are not suitable to provide an answer to their research question. Without additional data collection, this paper is not appropriate for publication’.

3. The rest of your review should provide detailed comments about the manuscript. It is most helpful to Editors and authors if this section is structured in some way. Many reviewers start with the major problems first, then list more minor comments afterwards. Major comments would be those which need to be addressed before the paper is publishable and/or which will take substantial work to resolve – such as concerns with the methodology or the authors’ interpretation of results. Minor comments could be recommendations for revisions that are not necessarily essential to make the paper publishable – for example, suggestions for additional literature to include, or cosmetic changes.

4. Remember that you have two audiences: the Editor and the authors. Authors need to know what was good about the paper and where improvements could be made. The Editor needs to know if you think the manuscript is a publishable piece of work. Bear in mind that different journals have different criteria for what makes a paper publishable – this information should be accessible on the journal webpage, or you might have been sent guidance to help with this when you accepted the invitation to review.

5. Your review should be clear, constructive and consistent.

- Clarity is important because authors will not be able to respond to your concerns if they don’t fully understand what they are.

- Reviews are most helpful if they don’t just criticise, but also make constructive suggestions for how concerns may be resolved.

- Your overall recommendation should be consistent with your comments. There is likely to be an opportunity to provide confidential comments to the Editor to provide further context or justification for your recommendation, but don’t include comments here that are completely different from the main messages of your review. The Editor needs to be able to justify their final decision to the authors using the reviewer comments as part of their evidence.

6. Don’t be afraid to highlight good things about the paper – a good review does not just criticise but also highlights what the authors have done well.

7. Your review should always be polite; it is unprofessional to use derogatory language or take a harsh or sarcastic tone (and remember that even if reviewer names are blinded to authors, the Editor knows who you are…). Write the review in a tone you would be happy to receive.

What does a bad review look like?

1. One which uses insulting or unprofessional language.

2. An unstructured stream of consciousness, which lists many concerns but without any indication of which are the most serious.

3. One in which the comments are too brief for the Editor to understand what you liked or didn’t like about the paper.

4. One which doesn’t justify its recommendation, or makes a recommendation which is not reflected in the comments. The Editor needs to know why you came to the recommendation you did.

5. One which insists on unnecessary revisions – maybe the paper would be improved by another seven experiments, but that’s not relevant to the question of whether the paper you have in front of you is publishable. You should feel free to make suggestions about additional work that you think might improve the paper, but don’t insist on this unless the paper in front of you isn’t publishable without it.

6. One which makes unreasonable demands. Think about how the authors are going to respond to your concerns, and only recommend changes which are feasible.

Peer reviewing is an opportunity to improve the quality of published research, and is very valuable to the research process when it works well. I hope these tips are helpful for making the process as efficient (and painless!) as possible.

The full slide set for Rebecca’s training course on ‘Good practice in peer review’, which also includes links to useful online resources.

Visit our website for more information on reviewing for the Royal Society’s journals.

Dr Rebecca Sear

Helen Eaton

Head of the Department of Population Health at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

Senior Commissioning Editor, the Royal Society

Related blogs

Buchi Okereafor

In publishing

AI and the future of scholarly publishing (part 1)

The focus for this year's Peer Review Week is 'Peer Review and the Future of Publishing'. We speak…

AI and the future of scholarly publishing (part 2)

Matt Hodgkinson, Research Integrity Manager at the UK Research Integrity Office, gives us an…

Callum Shoosmith

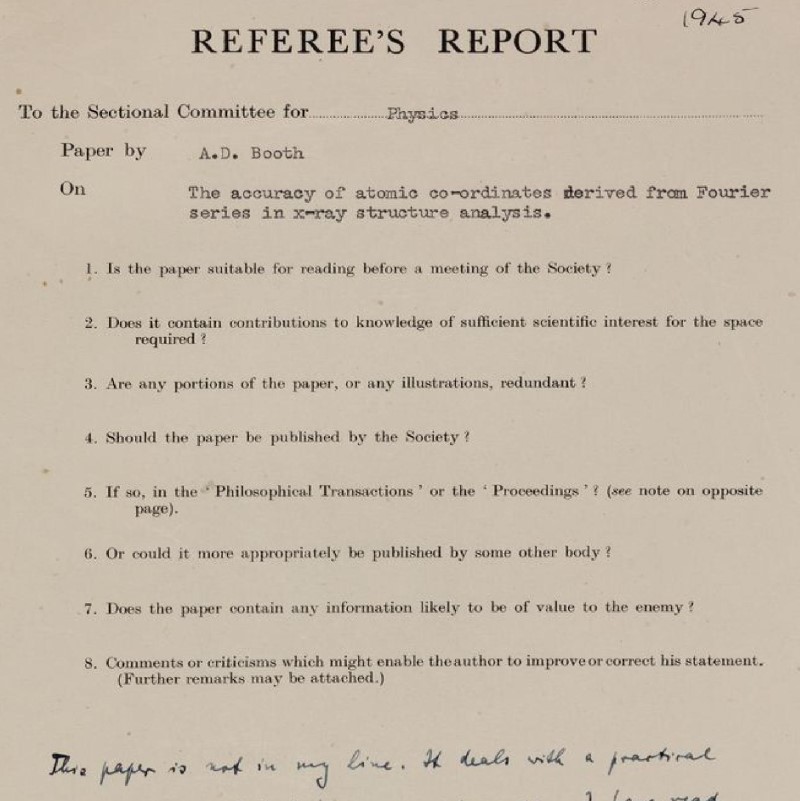

The future of peer review in the 17th Century

For Peer Review Week 2023 we explore the Royal Society’s collection of centuries-old referee…

Email updates

We promote excellence in science so that, together, we can benefit humanity and tackle the biggest challenges of our time.

Subscribe to our newsletters to be updated with the latest news on innovation, events, articles and reports.

What subscription are you interested in receiving? (Choose at least one subject)

How to Write a Peer Review: 12 things you need to know

Joanna Wilkinson

Learning how to peer review is no small feat. You’re responsible for protecting the public from false findings and research flaws, while at the same time helping to uncover legitimate breakthroughs. You’re also asked to constructively critique the research of your peers, some of which has taken blood, sweat, tears and years to put together.

Despite this, peer review doesn’t need to be hard or nerve-wracking–or make you feel like you’re doomed to fail.

We’ve put together 12 tips to help with peer review , and you can learn the entire process with our free peer review training course, the Web of Science Academy . This on-demand, practical course and comes with one-to-one support with your own mentor. You’ll have exclusive access to our peer review template, plenty of expert review examples to learn from, and by the end of it, you’ll not only be a certified reviewer, we’ll help put you in front of editors in your field.

The peer review process

Journal peer review is a critical tool for ensuring the quality and integrity of the research literature. It is the process by which researchers use their expert knowledge of a topic to assess an article for its accuracy and rigor, and to help make sure it builds on and adds to the current literature.

It’s actually a very structured process; it can be learned and improved the more you do it, and you’ll become faster and more confident as time goes on. Soon enough, you’ll even start benefiting from the process yourself.

Peer review not only helps to maintain the quality and integrity of literature in your field, it’s key to your own development as a researcher. It’s a great way to keep abreast of current research, impress editors at elite journals, and hone your critical analysis skills. It teaches you how to review a manuscript , spot common flaws in research papers , and improve your own chances of being a successful published author .

12-step guide to writing a peer review

To get the most out of the peer review process, you’ll want to keep some best practice tips and techniques in mind from the start. This will help you write a review around two to three pages (four maximum) in length.

We asked an expert panel of researchers what steps they take to ensure a thorough and robust review. We then compiled their advice into 12 easy steps with link to blog posts for further information:

1) Make sure you have the right expertise. Check out our post, Are you the right reviewer? for our checklist to assess whether you should take on a certain peer review request.

2) Visit the journal web page to learn their reviewer-specific instructions. Check the manuscript fits in the journal format and the references are standardised (if the editor has not already done so).

3) Skim the paper very quickly to get a general sense of the article. Underline key words and arguments, and summarise key points. This will help you quickly “tune in” to the paper during the next read.

4) Sit in a quiet place and read the manuscript critically. Make sure you have the tables, figures and references visible. Ask yourself key questions, including: Does it have a relevant title and valuable research question? Are key papers referenced? What’s the author’s motivation for the study and the idea behind it? Are the data and tools suitable and correct? What’s new about it? Why does that matter? Are there other considerations? Find out more in our 12-step guide to critically reviewing a manuscript .

5) Take notes about the major, moderate and minor revisions that need to be made . You need to make sure you can put the paper down and come back to it with fresh eyes later on. Note-taking is essential for this.

6) Are there any methodological concerns or common research errors? Check out our guide for common research flaws to watch out for .

7) Create a list of things to check. For example, does the referenced study actually show what is claimed in the paper?

8) Assess language and grammar, and make sure it’s a right ‘fit’ for the journal. Does the paper flow? Does it have connectivity? Does it have clarity? Are the words and structure concise and effective?

9) Is it new research? Check previous publications of the authors and of other authors in the field to be sure that the results were not published before.

10) Summarise your notes for the editor. This can include overview, contribution, strengths & weaknesses, and acceptability. You can also include the manuscript’s contribution/context for the authors (really just to clarify whether you view it similarly, or not), then prioritise and collate the major revisions and minor/specific revisions into feedback. Try to compile this in a logical way, grouping similar things under a common heading where possible, and numbering them for ease of reference.

11) Give specific recommendations to the authors for changes. What do you want them to work on? in the manuscript that the authors can do.

12) Give your recommendation to the editor.

We hope these 12 steps help get you on your way for your first peer review, or improving the structure of your current reviews. And remember, if you’d like to master the skills involved in peer review and get access to our Peer Review Template, sign up for our Web of Science Academy .

Our expert panel of reviewers include: Ana Marie Florea (Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf), James Cotter (University of Otago), and Robert Faff (University of Queensland). These reviewers are all recipients of the Global Peer Review Awards powered by Publons. They also and boast hundreds of pre-publication peer reviews for more than 100 different journals and sit on numerous editorial boards.

Related posts

Unlocking u.k. research excellence: key insights from the research professional news live summit.

For better insights, assess research performance at the department level

Getting the Full Picture: Institutional unification in the Web of Science

The Savvy Scientist

Experiences of a London PhD student and beyond

My Complete Guide to Academic Peer Review: Example Comments & How to Make Paper Revisions

Once you’ve submitted your paper to an academic journal you’re in the nerve-racking position of waiting to hear back about the fate of your work. In this post we’ll cover everything from potential responses you could receive from the editor and example peer review comments through to how to submit revisions.

My first first-author paper was reviewed by five (yes 5!) reviewers and since then I’ve published several others papers, so now I want to share the insights I’ve gained which will hopefully help you out!

This post is part of my series to help with writing and publishing your first academic journal paper. You can find the whole series here: Writing an academic journal paper .

The Peer Review Process

When you submit a paper to a journal, the first thing that will happen is one of the editorial team will do an initial assessment of whether or not the article is of interest. They may decide for a number of reasons that the article isn’t suitable for the journal and may reject the submission before even sending it out to reviewers.

If this happens hopefully they’ll have let you know quickly so that you can move on and make a start targeting a different journal instead.

Handy way to check the status – Sign in to the journal’s submission website and have a look at the status of your journal article online. If you can see that the article is under review then you’ve passed that first hurdle!

When your paper is under peer review, the journal will have set out a framework to help the reviewers assess your work. Generally they’ll be deciding whether the work is to a high enough standard.

Interested in reading about what reviewers are looking for? Check out my post on being a reviewer for the first time. Peer-Reviewing Journal Articles: Should You Do It? Sharing What I Learned From My First Experiences .

Once the reviewers have made their assessments, they’ll return their comments and suggestions to the editor who will then decide how the article should proceed.

How Many People Review Each Paper?

The editor ideally wants a clear decision from the reviewers as to whether the paper should be accepted or rejected. If there is no consensus among the reviewers then the editor may send your paper out to more reviewers to better judge whether or not to accept the paper.

If you’ve got a lot of reviewers on your paper it isn’t necessarily that the reviewers disagreed about accepting your paper.

You can also end up with lots of reviewers in the following circumstance:

- The editor asks a certain academic to review the paper but doesn’t get a response from them

- The editor asks another academic to step in

- The initial reviewer then responds

Next thing you know your work is being scrutinised by extra pairs of eyes!

As mentioned in the intro, my first paper ended up with five reviewers!

Potential Journal Responses

Assuming that the paper passes the editor’s initial evaluation and is sent out for peer-review, here are the potential decisions you may receive:

- Reject the paper. Sadly the editor and reviewers decided against publishing your work. Hopefully they’ll have included feedback which you can incorporate into your submission to another journal. I’ve had some rejections and the reviewer comments were genuinely useful.

- Accept the paper with major revisions . Good news: with some more work your paper could get published. If you make all the changes that the reviewers suggest, and they’re happy with your responses, then it should get accepted. Some people see major revisions as a disappointment but it doesn’t have to be.

- Accept the paper with minor revisions. This is like getting a major revisions response but better! Generally minor revisions can be addressed quickly and often come down to clarifying things for the reviewers: rewording, addressing minor concerns etc and don’t require any more experiments or analysis. You stand a really good chance of getting the paper published if you’ve been given a minor revisions result.

- Accept the paper with no revisions . I’m not sure that this ever really happens, but it is potentially possible if the reviewers are already completely happy with your paper!

Keen to know more about academic publishing? My series on publishing is now available as a free eBook. It includes my experiences being a peer reviewer. Click the image below for access.

Example Peer Review Comments & Addressing Reviewer Feedback

If your paper has been accepted but requires revisions, the editor will forward to you the comments and concerns that the reviewers raised. You’ll have to address these points so that the reviewers are satisfied your work is of a publishable standard.

It is extremely important to take this stage seriously. If you don’t do a thorough job then the reviewers won’t recommend that your paper is accepted for publication!

You’ll have to put together a resubmission with your co-authors and there are two crucial things you must do:

- Make revisions to your manuscript based off reviewer comments

- Reply to the reviewers, telling them the changes you’ve made and potentially changes you’ve not made in instances where you disagree with them. Read on to see some example peer review comments and how I replied!

Before making any changes to your actual paper, I suggest having a thorough read through the reviewer comments.

Once you’ve read through the comments you might be keen to dive straight in and make the changes in your paper. Instead, I actually suggest firstly drafting your reply to the reviewers.

Why start with the reply to reviewers? Well in a way it is actually potentially more important than the changes you’re making in the manuscript.

Imagine when a reviewer receives your response to their comments: you want them to be able to read your reply document and be satisfied that their queries have largely been addressed without even having to open the updated draft of your manuscript. If you do a good job with the replies, the reviewers will be better placed to recommend the paper be accepted!

By starting with your reply to the reviewers you’ll also clarify for yourself what changes actually have to be made to the paper.

So let’s now cover how to reply to the reviewers.

1. Replying to Journal Reviewers

It is so important to make sure you do a solid job addressing your reviewers’ feedback in your reply document. If you leave anything unanswered you’re asking for trouble, which in this case means either a rejection or another round of revisions: though some journals only give you one shot! Therefore make sure you’re thorough, not just with making the changes but demonstrating the changes in your replies.

It’s no good putting in the work to revise your paper but not evidence it in your reply to the reviewers!

There may be points that reviewers raise which don’t appear to necessitate making changes to your manuscript, but this is rarely the case. Even for comments or concerns they raise which are already addressed in the paper, clearly those areas could be clarified or highlighted to ensure that future readers don’t get confused.

How to Reply to Journal Reviewers

Some journals will request a certain format for how you should structure a reply to the reviewers. If so this should be included in the email you receive from the journal’s editor. If there are no certain requirements here is what I do:

- Copy and paste all replies into a document.

- Separate out each point they raise onto a separate line. Often they’ll already be nicely numbered but sometimes they actually still raise separate issues in one block of text. I suggest separating it all out so that each query is addressed separately.

- Form your reply for each point that they raise. I start by just jotting down notes for roughly how I’ll respond. Once I’m happy with the key message I’ll write it up into a scripted reply.

- Finally, go through and format it nicely and include line number references for the changes you’ve made in the manuscript.

By the end you’ll have a document that looks something like:

Reviewer 1 Point 1: [Quote the reviewer’s comment] Response 1: [Address point 1 and say what revisions you’ve made to the paper] Point 2: [Quote the reviewer’s comment] Response 2: [Address point 2 and say what revisions you’ve made to the paper] Then repeat this for all comments by all reviewers!

What To Actually Include In Your Reply To Reviewers

For every single point raised by the reviewers, you should do the following:

- Address their concern: Do you agree or disagree with the reviewer’s comment? Either way, make your position clear and justify any differences of opinion. If the reviewer wants more clarity on an issue, provide it. It is really important that you actually address their concerns in your reply. Don’t just say “Thanks, we’ve changed the text”. Actually include everything they want to know in your reply. Yes this means you’ll be repeating things between your reply and the revisions to the paper but that’s fine.

- Reference changes to your manuscript in your reply. Once you’ve answered the reviewer’s question, you must show that you’re actually using this feedback to revise the manuscript. The best way to do this is to refer to where the changes have been made throughout the text. I personally do this by include line references. Make sure you save this right until the end once you’ve finished making changes!

Example Peer Review Comments & Author Replies

In order to understand how this works in practice I’d suggest reading through a few real-life example peer review comments and replies.

The good news is that published papers often now include peer-review records, including the reviewer comments and authors’ replies. So here are two feedback examples from my own papers:

Example Peer Review: Paper 1

Quantifying 3D Strain in Scaffold Implants for Regenerative Medicine, J. Clark et al. 2020 – Available here

This paper was reviewed by two academics and was given major revisions. The journal gave us only 10 days to get them done, which was a bit stressful!

- Reviewer Comments

- My reply to Reviewer 1

- My reply to Reviewer 2

One round of reviews wasn’t enough for Reviewer 2…

- My reply to Reviewer 2 – ROUND 2

Thankfully it was accepted after the second round of review, and actually ended up being selected for this accolade, whatever most notable means?!

Nice to see our recent paper highlighted as one of the most notable articles, great start to the week! Thanks @Materials_mdpi 😀 #openaccess & available here: https://t.co/AKWLcyUtpC @ICBiomechanics @julianrjones @saman_tavana pic.twitter.com/ciOX2vftVL — Jeff Clark (@savvy_scientist) December 7, 2020

Example Peer Review: Paper 2

Exploratory Full-Field Mechanical Analysis across the Osteochondral Tissue—Biomaterial Interface in an Ovine Model, J. Clark et al. 2020 – Available here

This paper was reviewed by three academics and was given minor revisions.

- My reply to Reviewer 3

I’m pleased to say it was accepted after the first round of revisions 🙂

Things To Be Aware Of When Replying To Peer Review Comments

- Generally, try to make a revision to your paper for every comment. No matter what the reviewer’s comment is, you can probably make a change to the paper which will improve your manuscript. For example, if the reviewer seems confused about something, improve the clarity in your paper. If you disagree with the reviewer, include better justification for your choices in the paper. It is far more favourable to take on board the reviewer’s feedback and act on it with actual changes to your draft.

- Organise your responses. Sometimes journals will request the reply to each reviewer is sent in a separate document. Unless they ask for it this way I stick them all together in one document with subheadings eg “Reviewer 1” etc.

- Make sure you address each and every question. If you dodge anything then the reviewer will have a valid reason to reject your resubmission. You don’t need to agree with them on every point but you do need to justify your position.

- Be courteous. No need to go overboard with compliments but stay polite as reviewers are providing constructive feedback. I like to add in “We thank the reviewer for their suggestion” every so often where it genuinely warrants it. Remember that written language doesn’t always carry tone very well, so rather than risk coming off as abrasive if I don’t agree with the reviewer’s suggestion I’d rather be generous with friendliness throughout the reply.

2. How to Make Revisions To Your Paper

Once you’ve drafted your replies to the reviewers, you’ve actually done a lot of the ground work for making changes to the paper. Remember, you are making changes to the paper based off the reviewer comments so you should regularly be referring back to the comments to ensure you’re not getting sidetracked.

Reviewers could request modifications to any part of your paper. You may need to collect more data, do more analysis, reformat some figures, add in more references or discussion or any number of other revisions! So I can’t really help with everything, even so here is some general advice:

- Use tracked-changes. This is so important. The editor and reviewers need to be able to see every single change you’ve made compared to your first submission. Sometimes the journal will want a clean copy too but always start with tracked-changes enabled then just save a clean copy afterwards.

- Be thorough . Try to not leave any opportunity for the reviewers to not recommend your paper to be published. Any chance you have to satisfy their concerns, take it. For example if the reviewers are concerned about sample size and you have the means to include other experiments, consider doing so. If they want to see more justification or references, be thorough. To be clear again, this doesn’t necessarily mean making changes you don’t believe in. If you don’t want to make a change, you can justify your position to the reviewers. Either way, be thorough.

- Use your reply to the reviewers as a guide. In your draft reply to the reviewers you should have already included a lot of details which can be incorporated into the text. If they raised a concern, you should be able to go and find references which address the concern. This reference should appear both in your reply and in the manuscript. As mentioned above I always suggest starting with the reply, then simply adding these details to your manuscript once you know what needs doing.

Putting Together Your Paper Revision Submission

- Once you’ve drafted your reply to the reviewers and revised manuscript, make sure to give sufficient time for your co-authors to give feedback. Also give yourself time afterwards to make changes based off of their feedback. I ideally give a week for the feedback and another few days to make the changes.

- When you’re satisfied that you’ve addressed the reviewer comments, you can think about submitting it. The journal may ask for another letter to the editor, if not I simply add to the top of the reply to reviewers something like:

“Dear [Editor], We are grateful to the reviewer for their positive and constructive comments that have led to an improved manuscript. Here, we address their concerns/suggestions and have tracked changes throughout the revised manuscript.”

Once you’re ready to submit:

- Double check that you’ve done everything that the editor requested in their email

- Double check that the file names and formats are as required

- Triple check you’ve addressed the reviewer comments adequately

- Click submit and bask in relief!

You won’t always get the paper accepted, but if you’re thorough and present your revisions clearly then you’ll put yourself in a really good position. Remember to try as hard as possible to satisfy the reviewers’ concerns to minimise any opportunity for them to not accept your revisions!

Best of luck!

I really hope that this post has been useful to you and that the example peer review section has given you some ideas for how to respond. I know how daunting it can be to reply to reviewers, and it is really important to try to do a good job and give yourself the best chances of success. If you’d like to read other posts in my academic publishing series you can find them here:

Blog post series: Writing an academic journal paper

Subscribe below to stay up to date with new posts in the academic publishing series and other PhD content.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

Related Posts

Thesis Title: Examples and Suggestions from a PhD Grad

23rd February 2024 23rd February 2024

How to Stay Healthy as a Student

25th January 2024 25th January 2024

How to Master LinkedIn for Academics & PhD Students

22nd December 2023 22nd December 2023

2 Comments on “My Complete Guide to Academic Peer Review: Example Comments & How to Make Paper Revisions”

Excellent article! Thank you for the inspiration!

No worries at all, thanks for your kind comment!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Privacy Overview

- Peer Review System

- Production Service

- OA Publishing Platform

- Law Review System

- Why Scholastica?

- Customer Stories

- eBooks, Guides & More

- Schedule a demo

- Law Reviews

- Innovations In Academia

- New Features

Subscribe to receive posts by email

- Legal Scholarship

- Peer Review/Publishing

- I agree to the data use terms outlined in Scholastica's Privacy Policy Must agree to privacy policy.

How to Write Constructive Peer Review Comments: Tips every journal should give referees

Like the art of tightrope walking, writing helpful peer review comments requires honing the ability to traverse many fine lines.

Referees have to strike a balance between being too critical or too careful, too specific or too vague, too conclusive or too open-ended — and the list goes on. Regardless of the stage of a scholar’s career, learning how to write consistently constructive peer review comments takes time and practice.

Most scholars embark on peer review with little to no formal training. So a bit of guidance from journals before taking on assignments is often welcome and can make a big difference in review quality. In this blog post, we’re rounding up 7 tips journals can give referees to help them conduct solid peer reviews and deliver feedback effectively.

You can incorporate these tips into your journal reviewer guidelines and any training materials you prepare, or feel free to link reviewers straight to this blog post!

Take steps to avoid decision fatigue

Did you know that some sources suggest adults make upwards of 35,000 decisions per day ? Hard to believe, right?!

Whether that stat is indeed the norm, there’s no question that we humans make MANY choices on the regular, from what to wear and what route to take to work to avoid construction to which emails to respond to first and how to go about that really tricky research project in the midst of tackling usual tasks, meetings — and, well, everything else. And that’s all likely before 10 AM!

In his blog post “ How to Peer Review ,” Dr. Matthew Might, Professor in the Department of Medicine and Director of the Hugh Kaul Precision Medicine Institute at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, explained that over time the compounding mental strain of so much deliberation can result in a phenomenon known as decision fatigue . Decision fatigue is a deterioration in decision-making quality, which for busy peer reviewers can lead to writing less than articulate comments at best and missing critical points at worst.

In order to avoid decision fatigue, Might said scholars should try to work on peer reviews early in the day before they become bogged down with other matters. Additionally, he advises referees to work on no more than one review at a time when possible, or within one sitting at least, and to avoid reviewing when they feel tired or hungry. Taking steps to prevent decision fatigue can help scholars produce higher quality comments and, ultimately, write reviews faster because they’ll be working on them at times when they’re likely to be more focused and productive.

Of course, referees won’t always be able to follow every one of the above recommendations all of the time, nor will journal editors know if they have. But, it’s worth it for editors to remind reviewers to take decision fatigue into account before accepting and starting assignments.

Be cognizant of conscious and unconscious biases

Another decision-making factor that can cloud peer reviewers’ judgment that all editors should be hyper-attuned to is conscious and unconscious biases. Journal ethical guidelines are, of course, the first line of defense for preventing explicit biases. Every journal should have conflict of interest policies on when and how to disclose potential competing interests (e.g., financial ties, academic commitments, personal relationships) that could influence reviewers’ (as well as editors’ and authors’) level of objectivity in the publication process. The Committee on Publication Ethics offers many helpful guides for developing conflict of interest / competing interest statements, and medical journals can find a “summary of key elements for peer-reviewed medical journal’s conflict of interest policies” from The World Association of Medical Editors (WAME) here .

But what about unconscious biases that could have potentially insidious impacts on peer reviews?

Journals can help curb implicit bias by following double-anonymized peer review processes. Though, as the editors of Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology acknowledged in an announcement about their decision to move to double-anonymized peer review, even when all parties’ identities are concealed “unintentional exposure of author or institution identity is sometimes unavoidable, such as in small, specialized fields or subsequent to early sharing of data at conferences.”

Truly tackling unconscious biases requires getting to their roots, starting with acknowledging that they exist. Journals should remind reviewers to be cognizant of the fact that everyone harbors implicit biases that could impact their decision-making, as IOPScience does here and Cambridge University Press does here and provide tips for spotting and addressing biases. IOP advises reviewers to “focus on facts rather than feelings, slow down your decision making, and consider and reconsider the reasons for your conclusions.” And CUP reminds referees that “rooting your review in evidence from the paper or proposal is crucial in avoiding bias.”

Journals can also offer unconscious bias prevention training or direct referees to available resources such as this recorded Peer Reviewer Unconscious Bias webinar from the American Heart Association.

Null or negative results aren’t a basis for rejection

Speaking of forms of bias that can affect the peer review process, “positive results bias” — or the tendency to want to accept and publish positive results rather than null or negative results — is a common one. In a Royal Society blog post on what makes a good peer review, Head of the Department of Population Health at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, Dr. Rebecca Sear, spoke to how positive results bias can throw a wrench in peer review. Speaking from the perspective of an author, editor, and reviewer, Sear said, “at worst, this distorts science by keeping valuable research out of the literature entirely. It also creates inefficiencies in the system when publishable research has to be submitted to multiple journals before publication, burdening several reviewers and editors with the costs of evaluating the same research. A further problem is that the anonymity typically given to peer reviewers can result in unprofessional behavior being unleashed on authors.”

Journals can help prevent positive results bias by clearly stating that recommendations regarding manuscript decisions should be made on the basis of the quality of the research question, methodology, and perceived accuracy (rather than positivity) of the findings. Remind reviewers (and editors) that null and negative results can also provide valuable and even novel contributions to the literature.

List the negatives and the positives

When it comes time to write peer review comments, some scholars may intentionally or not lean heavily towards giving criticism rather than praise. Of course, peer reviews need to be rigorous, and that requires a critical eye, but it’s important for reviewers to let authors know what they’re doing right also. Otherwise, the author may lose sight of the working parts of their submission and could end up actually making it worse in revisions.

Journals should remind reviewers that their goal is to help authors identify what they are doing correctly as well as where to improve . Reviews shouldn’t be so negative that the author ends up pulling apart their entire manuscript. Additionally, it’s worth reminding reviewers to keep snarky comments to themselves. As Dr. Might noted in his blog, the presence of sarcasm in peer review may nullify any useful feedback provided in the eyes of the author.

Give concrete examples and advice (within scope!)

No author likes hearing that an area of their paper “needs work” without getting context as to why. It’s essential to remind reviewers to back up their comments and opinions with concrete examples and suggestions for improvement and ensure that any recommendations they’re making are within the scope of the journal requirements and research subject matter in question.

Remind reviewers that if they make suggestions for authors to provide additional references, data points, or experiments, they should be within scope and something the reviewer can confirm they would be able (and willing) to do themselves if in the author’s position.

One of the best ways to help train reviewers on how to give constructive feedback is to provide them with real-world examples. These “ Peer Review Examples “ from F1000 are a great starting point.

Another way editors can help reviewers give more concrete commentary is by advising them to log their reactions and responses to a paper as they read it. This can help reviewers avoid making blanket criticisms about an entire work that are, in fact, only applicable to some sections. It may also encourage reviewers to recognize and point out more positives!

Providing reviewers with detailed feedback forms and manuscript assessment checklists is another surefire way to help them stay on track.

Don’t be afraid to seek support

Journals should also remind prospective reviewers that it’s OK to ask for support when working on peer reviews. For example, an early-career researcher might want to seek a mentor to co-author their first review with them or provide general guidance on how to determine whether an experiment was conducted in the best manner possible (keeping manuscript information confidential, of course).

To help new referees get their footing, journals can assist them in identifying mentorship opportunities where applicable and offer peer reviewer training or links to external resources. For example, Taylor & Francis has an “ Excellence in Peer Review “ course, and Sense About Science has a “ Peer Review Nuts and Bolts “ guide.

For journals dealing with specialized subject matter, it’s also critical to be prepared to bring in expert opinions when needed. Editors should let reviewers know not to hesitate to suggest bringing in an expert if they feel it’s necessary.

Follow the Golden Rule

Finally, perhaps the best piece of advice journals can give reviewers is to follow the Golden Rule. You know it, “do unto others as you would have them do unto you.”

In his “How to peer review” guide, Dr. Matthew Might provided a clear barometer for referees to determine if they’ve prepared a thorough and fair review. “Once you’ve completed your review, ask yourself if you would be satisfied with the quality had you received the same for your own work,” he said. “If the answer is no, revise.”

Related Posts

3 Reasons Your Peer Review Process is Harder Than It Needs to Be

From disorganized journal data to scattered communication, there are a lot of traps journals can fall into that complicate peer review. Here are 3 ways your journal may be making peer review harder than it needs to be.

New Editor Training Course: Guide to Managing Peer Reviewers

Scholastica announces the release of a free training course for journal editors on best practices for managing peer reviewers.

Webinar on Demand: OA Advocates Weigh in on Democratization of Academic Journals

Did you miss the live stream of Scholastica's webinar, OA Advocates Weigh in on the Democratization of Academic Journals? You can watch it on-demand!

New Research Integrity Toolkit from Scholastica and Research Square for Peer Review Week 2022

Scholastica and Research Square announce a joint Peer Review Week blog series on tools to promote research integrity for scholarly journal editors, publishers, and authors. The series will cover ways to advance more transparent, rigorous, and ethical peer review practices. Learn more!

A New Phase of Diamond OA Journal Development: Interview with TSR

One of the most exciting aspects of supporting Open Access journals for the Scholastica team is learning about their publication development journeys. In this interview, Jenn Pickering, managing editor of The Sedimentary Record, discusses how they reached the milestones of their 100th article published and a successful editorial board transfer following a journal expansion initiative.

The Rise of DIY Open Access Journals: University of Cambridge OA Week Presentation

As part of OA Week 2017, Scholastica had the opportunity to be a part of the University of Cambridge Open Access Week speaking series event Helping Researchers Publish in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics. Here's a recap of Scholastica CoFounder and CEO Brian Cody's presentation on the rise of DIY OA journal publishing.

Engaging in Peer Review

There are times when we write in solitary and intend to keep our words private. However, in many cases, we use writing as a way of communicating. We send messages, present and explain ideas, share information, and make arguments. One way to improve the effectiveness of this written communication is through peer-review.

What is Peer-Review?

In the most general of terms, peer-review is the act of having another writer read what you have written and respond in terms of its effectiveness. This reader attempts to identify the writing's strengths and weaknesses, and then suggests strategies for revising it. The hope is that not only will the specific piece of writing be improved, but that future writing attempts will also be more successful. Peer-review happens with all types of writing, at any stage of the process, and with all levels of writers.

Sometimes peer-review is called a writing workshop.

What is a Writing Workshop?

Peer-review sessions are sometimes called writing workshops. For example, students in a writing class might bring a draft of some writing that they are working on to share with either a single classmate or a group, bringing as many copies of the draft as they will need. There is usually a worksheet to fill out or a set questions for each peer-review reader to answer about the piece of writing. The writer might also request that their readers pay special attention to places where he or she would like specific help. An entire class can get together after reading and responding to discuss the writing as a group, or a single writer and reader can privately discuss the response, or the response can be written and shared in that way only.

Whether peer-review happens in a classroom setting or not, there are some common guidelines to follow.

Common Guidelines for Peer-Review

While peer-review is used in multiple contexts, there are some common guidelines to follow in any peer-review situation.

If You are the Writer

If you are the writer, think of peer-review as a way to test how well your writing is working. Keep an open mind and be prepared for criticism. Even the best writers have room for improvement. Even so, it is still up to you whether or not to take the peer-review reader's advice. If more than one person reads for you, you might receive conflicting responses, but don't panic. Consider each response and decide for yourself if you should make changes and what those changes will be. Not all the advice you get will be good, but learning to make revision choices based on the response is part of becoming a better writer.

If You are the Reader

As a peer-review reader, you will have an opportunity to practice your critical reading skills while at the same time helping the writer improve their writing skills. Specifically, you will want to do as follows:

Read the draft through once

Start by reading the draft through once, beginning to end, to get a general sense of the essay as a whole. Don't write on the draft yet. Use a piece of scratch paper to make notes if needed.

Write a summary

After an initial reading, it is sometimes helpful to write a short summary. A well written essay should be easy to summarize, so if writing a summary is difficult, try to determine why and share that with the writer. Also, if your understanding of the writer's main idea(s) turns out to be different from what the writer intended, that will be a place they can focus their revision efforts.

Focus on large issues

Focus your review on the larger writing issues. For example, the misplacement of a few commas is less important than the reader's ability to understand the main point of the essay. And yet, if you do notice a recurring problem with grammar or spelling, especially to the extent that it interferes with your ability to follow the essay, make sure to mention it.

Be constructive

Be constructive with your criticisms. A comment such as "This paragraph was boring" isn't helpful. Remember, this writer is your peer, so treat him/her with the respect and care that they deserve. Explain your responses. "I liked this part" or "This section doesn't work" isn't enough. Keep in mind that you are trying to help the writer revise, so give him/her enough information to be able to understand your responses. Point to specific places that show what you mean. As much as possible, don't criticize something without also giving the writer some suggestion for a possible solution. Be specific and helpful.

Be positive

Don't focus only on the things that aren't working, but also point out the things that are.

With these common guidelines in mind, here are some specific questions that are useful when doing peer-review.

Questions to Use

When doing peer-review, there are different ways to focus a response. You can use questions that are about the qualities of an essay or the different parts of an essay.

Questions to Ask about the Qualities of an Essay

When doing a peer-review response to a piece of writing, one way to focus it is by answering a set of questions about the qualities of an essay. Such qualities would be:

Organization

- Is there a clearly stated purpose/objective?

- Are there effective transitions?

- Are the introduction and conclusion focused on the main point of the essay?

- As a reader, can you easily follow the writer's flow of ideas?

- Is each paragraph focused on a single idea?

- At any point in the essay, do you feel lost or confused?

- Do any of the ideas/paragraphs seem out of order, too early or too late to be as effective as they could?

Development and Support

- Is each main point/idea made by the writer clearly developed and explained?

- Is the support/evidence for each point/idea persuasive and appropriate?

- Is the connection between the support/evidence, main point/idea, and the overall point of the essay made clear?

- Is all evidence adequately cited?

- Are the topic and tone of the essay appropriate for the audience?

- Are the sentences and word choices varied?

Grammar and Mechanics

- Does the writer use proper grammar, punctuation, and spelling?

- Are there any issues with any of these elements that make the writing unreadable or confusing?

Revision Strategy Suggestions

- What are two or three main revision suggestions that you have for the writer?

Questions to Ask about the Parts of an Essay

When doing a peer-review response to a piece of writing, one way to focus it is by answering a set of questions about the parts of an essay. Such parts would be:

Introduction

- Is there an introduction?

- Is it effective?

- Is it concise?

- Is it interesting?

- Does the introduction give the reader a sense of the essay's objective and entice the reader to read on?

- Does it meet the objective stated in the introduction?

- Does it stay focused on this objective or are there places it strays?

- Is it organized logically?

- Is each idea thoroughly explained and supported with good evidence?

- Are there transitions and are they effective?

- Is there a conclusion?

- Does it work?

Peer-Review Online

Peer-review doesn't happen only in classrooms or in face-to-face situations. A writer can share a text with peer-review readers in the context of a Web classroom. In this context, the writer's text and the reader's response are shared electronically using file-sharing, e-mail attachments, or discussion forums/message boards.

When responding to a document in these ways, the specific method changes because the reader can't write directly on the document like they would if it were a paper copy. It is even more important in this context to make comments and suggestions clear by thoroughly explaining and citing specific examples from the text.

When working with an electronic version of a text, such as an e-mail attachment, the reader can open the document or copy/paste the text in Microsoft Word, or other word-processing software. In this way, the reader can add his or her comments, save and then send the revised document back to the writer, either through e-mail, file sharing, or posting in a discussion forum.