Statistics Made Easy

What is a Directional Hypothesis? (Definition & Examples)

A statistical hypothesis is an assumption about a population parameter . For example, we may assume that the mean height of a male in the U.S. is 70 inches.

The assumption about the height is the statistical hypothesis and the true mean height of a male in the U.S. is the population parameter .

To test whether a statistical hypothesis about a population parameter is true, we obtain a random sample from the population and perform a hypothesis test on the sample data.

Whenever we perform a hypothesis test, we always write down a null and alternative hypothesis:

- Null Hypothesis (H 0 ): The sample data occurs purely from chance.

- Alternative Hypothesis (H A ): The sample data is influenced by some non-random cause.

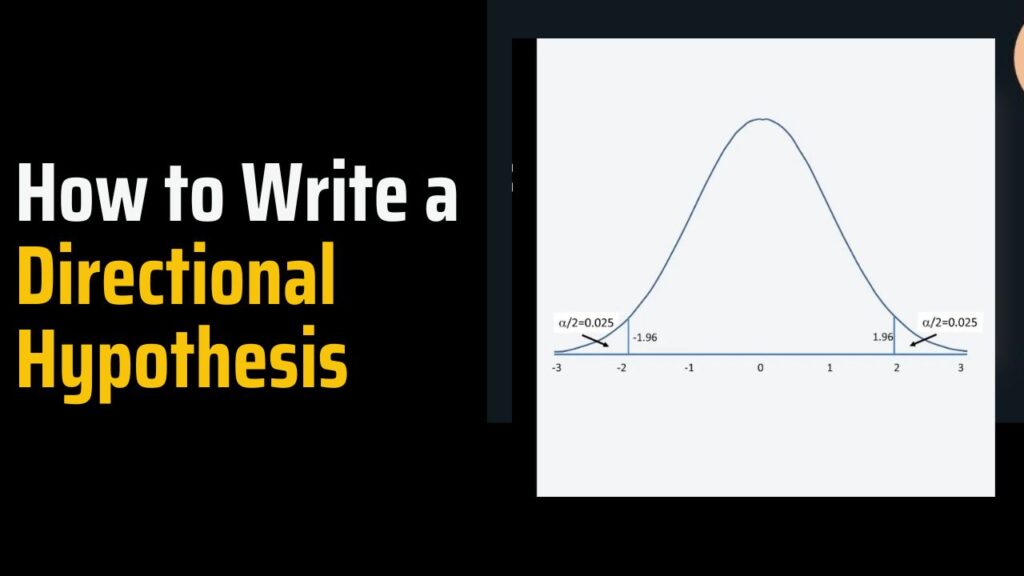

A hypothesis test can either contain a directional hypothesis or a non-directional hypothesis:

- Directional hypothesis: The alternative hypothesis contains the less than (“<“) or greater than (“>”) sign. This indicates that we’re testing whether or not there is a positive or negative effect.

- Non-directional hypothesis: The alternative hypothesis contains the not equal (“≠”) sign. This indicates that we’re testing whether or not there is some effect, without specifying the direction of the effect.

Note that directional hypothesis tests are also called “one-tailed” tests and non-directional hypothesis tests are also called “two-tailed” tests.

Check out the following examples to gain a better understanding of directional vs. non-directional hypothesis tests.

Example 1: Baseball Programs

A baseball coach believes a certain 4-week program will increase the mean hitting percentage of his players, which is currently 0.285.

To test this, he measures the hitting percentage of each of his players before and after participating in the program.

He then performs a hypothesis test using the following hypotheses:

- H 0 : μ = .285 (the program will have no effect on the mean hitting percentage)

- H A : μ > .285 (the program will cause mean hitting percentage to increase)

This is an example of a directional hypothesis because the alternative hypothesis contains the greater than “>” sign. The coach believes that the program will influence the mean hitting percentage of his players in a positive direction.

Example 2: Plant Growth

A biologist believes that a certain pesticide will cause plants to grow less during a one-month period than they normally do, which is currently 10 inches.

To test this, she applies the pesticide to each of the plants in her laboratory for one month.

She then performs a hypothesis test using the following hypotheses:

- H 0 : μ = 10 inches (the pesticide will have no effect on the mean plant growth)

- H A : μ < 10 inches (the pesticide will cause mean plant growth to decrease)

This is also an example of a directional hypothesis because the alternative hypothesis contains the less than “<” sign. The biologist believes that the pesticide will influence the mean plant growth in a negative direction.

Example 3: Studying Technique

A professor believes that a certain studying technique will influence the mean score that her students receive on a certain exam, but she’s unsure if it will increase or decrease the mean score, which is currently 82.

To test this, she lets each student use the studying technique for one month leading up to the exam and then administers the same exam to each of the students.

- H 0 : μ = 82 (the studying technique will have no effect on the mean exam score)

- H A : μ ≠ 82 (the studying technique will cause the mean exam score to be different than 82)

This is an example of a non-directional hypothesis because the alternative hypothesis contains the not equal “≠” sign. The professor believes that the studying technique will influence the mean exam score, but doesn’t specify whether it will cause the mean score to increase or decrease.

Additional Resources

Introduction to Hypothesis Testing Introduction to the One Sample t-test Introduction to the Two Sample t-test Introduction to the Paired Samples t-test

Hey there. My name is Zach Bobbitt. I have a Master of Science degree in Applied Statistics and I’ve worked on machine learning algorithms for professional businesses in both healthcare and retail. I’m passionate about statistics, machine learning, and data visualization and I created Statology to be a resource for both students and teachers alike. My goal with this site is to help you learn statistics through using simple terms, plenty of real-world examples, and helpful illustrations.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Directional Hypothesis: Definition and 10 Examples

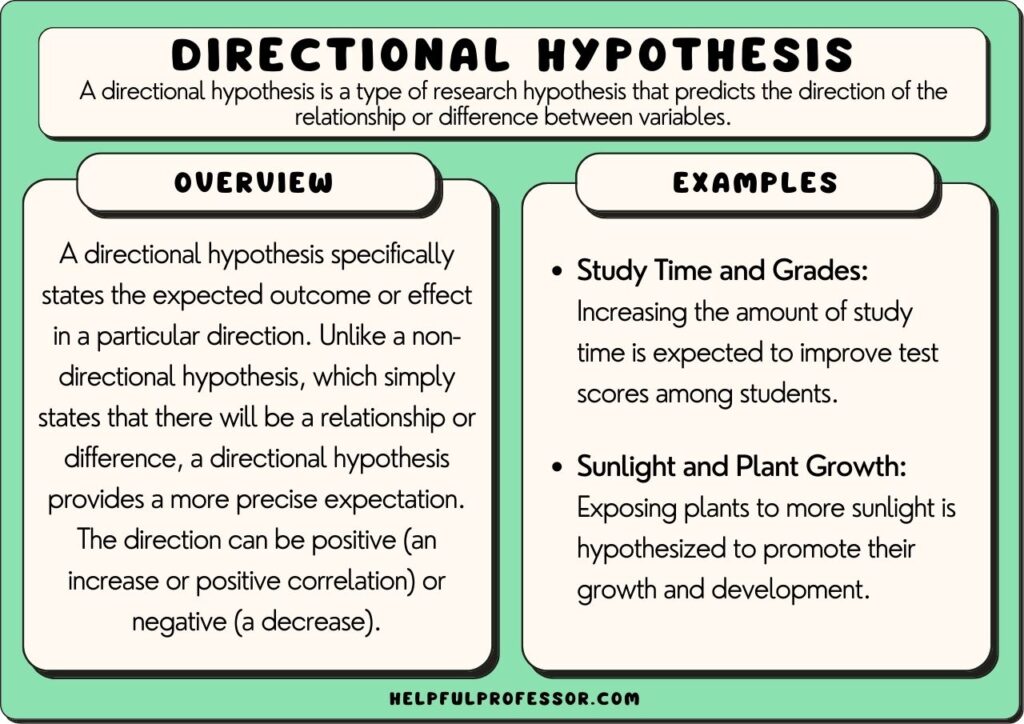

A directional hypothesis refers to a type of hypothesis used in statistical testing that predicts a particular direction of the expected relationship between two variables.

In simpler terms, a directional hypothesis is an educated, specific guess about the direction of an outcome—whether an increase, decrease, or a proclaimed difference in variable sets.

For example, in a study investigating the effects of sleep deprivation on cognitive performance, a directional hypothesis might state that as sleep deprivation (Independent Variable) increases, cognitive performance (Dependent Variable) decreases (Killgore, 2010). Such a hypothesis offers a clear, directional relationship whereby a specific increase or decrease is anticipated.

Global warming provides another notable example of a directional hypothesis. A researcher might hypothesize that as carbon dioxide (CO2) levels increase, global temperatures also increase (Thompson, 2010). In this instance, the hypothesis clearly articulates an upward trend for both variables.

In any given circumstance, it’s imperative that a directional hypothesis is grounded on solid evidence. For instance, the CO2 and global temperature relationship is based on substantial scientific evidence, and not on a random guess or mere speculation (Florides & Christodoulides, 2009).

Directional vs Non-Directional vs Null Hypotheses

A directional hypothesis is generally contrasted to a non-directional hypothesis. Here’s how they compare:

- Directional hypothesis: A directional hypothesis provides a perspective of the expected relationship between variables, predicting the direction of that relationship (either positive, negative, or a specific difference).

- Non-directional hypothesis: A non-directional hypothesis denotes the possibility of a relationship between two variables ( the independent and dependent variables ), although this hypothesis does not venture a prediction as to the direction of this relationship (Ali & Bhaskar, 2016). For example, a non-directional hypothesis might state that there exists a relationship between a person’s diet (independent variable) and their mood (dependent variable), without indicating whether improvement in diet enhances mood positively or negatively. Overall, the choice between a directional or non-directional hypothesis depends on the known or anticipated link between the variables under consideration in research studies.

Another very important type of hypothesis that we need to know about is a null hypothesis :

- Null hypothesis : The null hypothesis stands as a universality—the hypothesis that there is no observed effect in the population under study, meaning there is no association between variables (or that the differences are down to chance). For instance, a null hypothesis could be constructed around the idea that changing diet (independent variable) has no discernible effect on a person’s mood (dependent variable) (Yan & Su, 2016). This proposition is the one that we aim to disprove in an experiment.

While directional and non-directional hypotheses involve some integrated expectations about the outcomes (either distinct direction or a vague relationship), a null hypothesis operates on the premise of negating such relationships or effects.

The null hypotheses is typically proposed to be negated or disproved by statistical tests, paving way for the acceptance of an alternate hypothesis (either directional or non-directional).

Directional Hypothesis Examples

1. exercise and heart health.

Research suggests that as regular physical exercise (independent variable) increases, the risk of heart disease (dependent variable) decreases (Jakicic, Davis, Rogers, King, Marcus, Helsel, Rickman, Wahed, Belle, 2016). In this example, a directional hypothesis anticipates that the more individuals maintain routine workouts, the lesser would be their odds of developing heart-related disorders. This assumption is based on the underlying fact that routine exercise can help reduce harmful cholesterol levels, regulate blood pressure, and bring about overall health benefits. Thus, a direction – a decrease in heart disease – is expected in relation with an increase in exercise.

2. Screen Time and Sleep Quality

Another classic instance of a directional hypothesis can be seen in the relationship between the independent variable, screen time (especially before bed), and the dependent variable, sleep quality. This hypothesis predicts that as screen time before bed increases, sleep quality decreases (Chang, Aeschbach, Duffy, Czeisler, 2015). The reasoning behind this hypothesis is the disruptive effect of artificial light (especially blue light from screens) on melatonin production, a hormone needed to regulate sleep. As individuals spend more time exposed to screens before bed, it is predictably hypothesized that their sleep quality worsens.

3. Job Satisfaction and Employee Turnover

A typical scenario in organizational behavior research posits that as job satisfaction (independent variable) increases, the rate of employee turnover (dependent variable) decreases (Cheng, Jiang, & Riley, 2017). This directional hypothesis emphasizes that an increased level of job satisfaction would lead to a reduced rate of employees leaving the company. The theoretical basis for this hypothesis is that satisfied employees often tend to be more committed to the organization and are less likely to seek employment elsewhere, thus reducing turnover rates.

4. Healthy Eating and Body Weight

Healthy eating, as the independent variable, is commonly thought to influence body weight, the dependent variable, in a positive way. For example, the hypothesis might state that as consumption of healthy foods increases, an individual’s body weight decreases (Framson, Kristal, Schenk, Littman, Zeliadt, & Benitez, 2009). This projection is based on the premise that healthier foods, such as fruits and vegetables, are generally lower in calories than junk food, assisting in weight management.

5. Sun Exposure and Skin Health

The association between sun exposure (independent variable) and skin health (dependent variable) allows for a definitive hypothesis declaring that as sun exposure increases, the risk of skin damage or skin cancer increases (Whiteman, Whiteman, & Green, 2001). The premise aligns with the understanding that overexposure to the sun’s ultraviolet rays can deteriorate skin health, leading to conditions like sunburn or, in extreme cases, skin cancer.

6. Study Hours and Academic Performance

A regularly assessed relationship in academia suggests that as the number of study hours (independent variable) rises, so too does academic performance (dependent variable) (Nonis, Hudson, Logan, Ford, 2013). The hypothesis proposes a positive correlation , with an increase in study time expected to contribute to enhanced academic outcomes.

7. Screen Time and Eye Strain

It’s commonly hypothesized that as screen time (independent variable) increases, the likelihood of experiencing eye strain (dependent variable) also increases (Sheppard & Wolffsohn, 2018). This is based on the idea that prolonged engagement with digital screens—computers, tablets, or mobile phones—can cause discomfort or fatigue in the eyes, attributing to symptoms of eye strain.

8. Physical Activity and Stress Levels

In the sphere of mental health, it’s often proposed that as physical activity (independent variable) increases, levels of stress (dependent variable) decrease (Stonerock, Hoffman, Smith, Blumenthal, 2015). Regular exercise is known to stimulate the production of endorphins, the body’s natural mood elevators, helping to alleviate stress.

9. Water Consumption and Kidney Health

A common health-related hypothesis might predict that as water consumption (independent variable) increases, the risk of kidney stones (dependent variable) decreases (Curhan, Willett, Knight, & Stampfer, 2004). Here, an increase in water intake is inferred to reduce the risk of kidney stones by diluting the substances that lead to stone formation.

10. Traffic Noise and Sleep Quality

In urban planning research, it’s often supposed that as traffic noise (independent variable) increases, sleep quality (dependent variable) decreases (Muzet, 2007). Increased noise levels, particularly during the night, can result in sleep disruptions, thus, leading to poor sleep quality.

11. Sugar Consumption and Dental Health

In the field of dental health, an example might be stating as one’s sugar consumption (independent variable) increases, dental health (dependent variable) decreases (Sheiham, & James, 2014). This stems from the fact that sugar is a major factor in tooth decay, and increased consumption of sugary foods or drinks leads to a decline in dental health due to the high likelihood of cavities.

See 15 More Examples of Hypotheses Here

A directional hypothesis plays a critical role in research, paving the way for specific predicted outcomes based on the relationship between two variables. These hypotheses clearly illuminate the expected direction—the increase or decrease—of an effect. From predicting the impacts of healthy eating on body weight to forecasting the influence of screen time on sleep quality, directional hypotheses allow for targeted and strategic examination of phenomena. In essence, directional hypotheses provide the crucial path for inquiry, shaping the trajectory of research studies and ultimately aiding in the generation of insightful, relevant findings.

Ali, S., & Bhaskar, S. (2016). Basic statistical tools in research and data analysis. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia, 60 (9), 662-669. doi: https://doi.org/10.4103%2F0019-5049.190623

Chang, A. M., Aeschbach, D., Duffy, J. F., & Czeisler, C. A. (2015). Evening use of light-emitting eReaders negatively affects sleep, circadian timing, and next-morning alertness. Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences, 112 (4), 1232-1237. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1418490112

Cheng, G. H. L., Jiang, D., & Riley, J. H. (2017). Organizational commitment and intrinsic motivation of regular and contractual primary school teachers in China. New Psychology, 19 (3), 316-326. Doi: https://doi.org/10.4103%2F2249-4863.184631

Curhan, G. C., Willett, W. C., Knight, E. L., & Stampfer, M. J. (2004). Dietary factors and the risk of incident kidney stones in younger women: Nurses’ Health Study II. Archives of Internal Medicine, 164 (8), 885–891.

Florides, G. A., & Christodoulides, P. (2009). Global warming and carbon dioxide through sciences. Environment international , 35 (2), 390-401. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2008.07.007

Framson, C., Kristal, A. R., Schenk, J. M., Littman, A. J., Zeliadt, S., & Benitez, D. (2009). Development and validation of the mindful eating questionnaire. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 109 (8), 1439-1444. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2009.05.006

Jakicic, J. M., Davis, K. K., Rogers, R. J., King, W. C., Marcus, M. D., Helsel, D., … & Belle, S. H. (2016). Effect of wearable technology combined with a lifestyle intervention on long-term weight loss: The IDEA randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 316 (11), 1161-1171.

Khan, S., & Iqbal, N. (2013). Study of the relationship between study habits and academic achievement of students: A case of SPSS model. Higher Education Studies, 3 (1), 14-26.

Killgore, W. D. (2010). Effects of sleep deprivation on cognition. Progress in brain research , 185 , 105-129. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53702-7.00007-5

Marczinski, C. A., & Fillmore, M. T. (2014). Dissociative antagonistic effects of caffeine on alcohol-induced impairment of behavioral control. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 22 (4), 298–311. doi: https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/1064-1297.11.3.228

Muzet, A. (2007). Environmental Noise, Sleep and Health. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 11 (2), 135-142. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2006.09.001

Nonis, S. A., Hudson, G. I., Logan, L. B., & Ford, C. W. (2013). Influence of perceived control over time on college students’ stress and stress-related outcomes. Research in Higher Education, 54 (5), 536-552. doi: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018753706925

Sheiham, A., & James, W. P. (2014). A new understanding of the relationship between sugars, dental caries and fluoride use: implications for limits on sugars consumption. Public health nutrition, 17 (10), 2176-2184. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S136898001400113X

Sheppard, A. L., & Wolffsohn, J. S. (2018). Digital eye strain: prevalence, measurement and amelioration. BMJ open ophthalmology , 3 (1), e000146. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjophth-2018-000146

Stonerock, G. L., Hoffman, B. M., Smith, P. J., & Blumenthal, J. A. (2015). Exercise as Treatment for Anxiety: Systematic Review and Analysis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 49 (4), 542–556. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-014-9685-9

Thompson, L. G. (2010). Climate change: The evidence and our options. The Behavior Analyst , 33 , 153-170. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03392211

Whiteman, D. C., Whiteman, C. A., & Green, A. C. (2001). Childhood sun exposure as a risk factor for melanoma: a systematic review of epidemiologic studies. Cancer Causes & Control, 12 (1), 69-82. doi: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008980919928

Yan, X., & Su, X. (2009). Linear regression analysis: theory and computing . New Jersey: World Scientific.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 50 Durable Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 100 Consumer Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 30 Globalization Pros and Cons

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

How to Write a Directional Hypothesis: A Step-by-Step Guide

In research, hypotheses play a crucial role in guiding investigations and making predictions about relationships between variables.

One type of hypothesis that researchers often encounter is the directional hypothesis, also known as a one-tailed hypothesis.

In this blog post, we’ll explore what a directional hypothesis is, why it’s important, and provide a step-by-step guide on how to write one effectively.

Table of Contents

What is a Directional Hypothesis?

A directional hypothesis is a statement that predicts the direction of the relationship between two variables. Unlike non-directional hypotheses, which simply state that there is a relationship between variables without specifying the direction, directional hypotheses make a clear prediction about the expected outcome.

For example, a directional hypothesis might predict that an increase in one variable will lead to a decrease in another.

Examples of Directional Hypotheses

- Increasing the amount of sunlight exposure will lead to higher levels of vitamin D in the body.

- Decreasing the amount of sugar consumption will result in lower body weight among participants.

- Introducing mindfulness meditation techniques will reduce symptoms of anxiety in patients with generalized anxiety disorder.

Why to Write a Directional Hypothesis?

Directional hypotheses offer several advantages in research. They provide researchers with a more focused prediction, allowing them to test specific hypotheses rather than exploring all possible relationships between variables.

This can help streamline research efforts and increase the likelihood of finding meaningful results. Additionally, directional hypotheses are often used in experimental research, where researchers manipulate variables to observe their effects on outcomes.

Step 1: Identify the Variables

Start by identifying the independent variable (the variable you are manipulating) and the dependent variable (the variable you are measuring). Understanding the relationship between these variables is essential for writing a directional hypothesis.

Step 2: Predict the Direction

Based on your understanding of the relationship between the variables, predict the direction of the effect.

Will an increase in the independent variable lead to an increase or decrease in the dependent variable?

Be specific in your prediction.

Step 3: Use Clear Language

Write your directional hypothesis using clear and concise language. Avoid technical jargon or terms that may be difficult for readers to understand. Your hypothesis should be easily understood by both researchers and non-experts.

Step 4: Ensure Testability

Ensure that your hypothesis is testable by collecting data and conducting statistical analysis. You should be able to measure the variables and determine whether the observed results support or refute your hypothesis.

Step 5: Revise and Refine

Review your directional hypothesis to ensure that it accurately reflects your research question and predictions. Make any necessary revisions to improve clarity and specificity.

Writing a directional hypothesis is an essential skill for researchers conducting experiments and investigations.

By following the steps outlined in this guide, you can effectively formulate hypotheses that make clear predictions about the relationship between variables.

Whether you’re a researcher or just starting out in the field, mastering the art of writing directional hypotheses will enhance the quality and rigor of your research endeavors.

Related Posts

Difference between quota sampling and stratified sampling, what is purposive sampling | examples, quota sampling in research, top ai tools for literature review , research design | importance, types of research design examples, 9 qualitative research designs and research methods, tips to increase your journal citation score, types of research quiz, difference between cohort study and case control study, convenience sampling: method and examples.

Comments are closed.

What is a Directional Hypothesis? (Definition & Examples)

A statistical hypothesis is an assumption about a population parameter . For example, we may assume that the mean height of a male in the U.S. is 70 inches.

The assumption about the height is the statistical hypothesis and the true mean height of a male in the U.S. is the population parameter .

To test whether a statistical hypothesis about a population parameter is true, we obtain a random sample from the population and perform a hypothesis test on the sample data.

Whenever we perform a hypothesis test, we always write down a null and alternative hypothesis:

- Null Hypothesis (H 0 ): The sample data occurs purely from chance.

- Alternative Hypothesis (H A ): The sample data is influenced by some non-random cause.

A hypothesis test can either contain a directional hypothesis or a non-directional hypothesis:

- Directional hypothesis: The alternative hypothesis contains the less than (“”) sign. This indicates that we’re testing whether or not there is a positive or negative effect.

- Non-directional hypothesis: The alternative hypothesis contains the not equal (“≠”) sign. This indicates that we’re testing whether or not there is some effect, without specifying the direction of the effect.

Note that directional hypothesis tests are also called “one-tailed” tests and non-directional hypothesis tests are also called “two-tailed” tests.

Check out the following examples to gain a better understanding of directional vs. non-directional hypothesis tests.

Example 1: Baseball Programs

A baseball coach believes a certain 4-week program will increase the mean hitting percentage of his players, which is currently 0.285.

To test this, he measures the hitting percentage of each of his players before and after participating in the program.

He then performs a hypothesis test using the following hypotheses:

- H 0 : μ = .285 (the program will have no effect on the mean hitting percentage)

- H A : μ > .285 (the program will cause mean hitting percentage to increase)

This is an example of a directional hypothesis because the alternative hypothesis contains the greater than “>” sign. The coach believes that the program will influence the mean hitting percentage of his players in a positive direction.

Example 2: Plant Growth

A biologist believes that a certain pesticide will cause plants to grow less during a one-month period than they normally do, which is currently 10 inches.

To test this, she applies the pesticide to each of the plants in her laboratory for one month.

She then performs a hypothesis test using the following hypotheses:

- H 0 : μ = 10 inches (the pesticide will have no effect on the mean plant growth)

This is also an example of a directional hypothesis because the alternative hypothesis contains the less than “negative direction.

Example 3: Studying Technique

A professor believes that a certain studying technique will influence the mean score that her students receive on a certain exam, but she’s unsure if it will increase or decrease the mean score, which is currently 82.

To test this, she lets each student use the studying technique for one month leading up to the exam and then administers the same exam to each of the students.

- H 0 : μ = 82 (the studying technique will have no effect on the mean exam score)

- H A : μ ≠ 82 (the studying technique will cause the mean exam score to be different than 82)

This is an example of a non-directional hypothesis because the alternative hypothesis contains the not equal “≠” sign. The professor believes that the studying technique will influence the mean exam score, but doesn’t specify whether it will cause the mean score to increase or decrease.

Additional Resources

Introduction to Hypothesis Testing Introduction to the One Sample t-test Introduction to the Two Sample t-test Introduction to the Paired Samples t-test

How to Perform a Partial F-Test in Excel

4 examples of confidence intervals in real life, related posts, how to normalize data between -1 and 1, vba: how to check if string contains another..., how to interpret f-values in a two-way anova, how to create a vector of ones in..., how to determine if a probability distribution is..., what is a symmetric histogram (definition & examples), how to find the mode of a histogram..., how to find quartiles in even and odd..., how to calculate sxy in statistics (with example), how to calculate sxx in statistics (with example).

Directional and non-directional hypothesis: A Comprehensive Guide

Karolina Konopka

Customer support manager

In the world of research and statistical analysis, hypotheses play a crucial role in formulating and testing scientific claims. Understanding the differences between directional and non-directional hypothesis is essential for designing sound experiments and drawing accurate conclusions. Whether you’re a student, researcher, or simply curious about the foundations of hypothesis testing, this guide will equip you with the knowledge and tools to navigate this fundamental aspect of scientific inquiry.

Understanding Directional Hypothesis

Understanding directional hypotheses is crucial for conducting hypothesis-driven research, as they guide the selection of appropriate statistical tests and aid in the interpretation of results. By incorporating directional hypotheses, researchers can make more precise predictions, contribute to scientific knowledge, and advance their fields of study.

Definition of directional hypothesis

Directional hypotheses, also known as one-tailed hypotheses, are statements in research that make specific predictions about the direction of a relationship or difference between variables. Unlike non-directional hypotheses, which simply state that there is a relationship or difference without specifying its direction, directional hypotheses provide a focused and precise expectation.

A directional hypothesis predicts either a positive or negative relationship between variables or predicts that one group will perform better than another. It asserts a specific direction of effect or outcome. For example, a directional hypothesis could state that “increased exposure to sunlight will lead to an improvement in mood” or “participants who receive the experimental treatment will exhibit higher levels of cognitive performance compared to the control group.”

Directional hypotheses are formulated based on existing theory, prior research, or logical reasoning, and they guide the researcher’s expectations and analysis. They allow for more targeted predictions and enable researchers to test specific hypotheses using appropriate statistical tests.

The role of directional hypothesis in research

Directional hypotheses also play a significant role in research surveys. Let’s explore their role specifically in the context of survey research:

- Objective-driven surveys : Directional hypotheses help align survey research with specific objectives. By formulating directional hypotheses, researchers can focus on gathering data that directly addresses the predicted relationship or difference between variables of interest.

- Question design and measurement : Directional hypotheses guide the design of survey question types and the selection of appropriate measurement scales. They ensure that the questions are tailored to capture the specific aspects related to the predicted direction, enabling researchers to obtain more targeted and relevant data from survey respondents.

- Data analysis and interpretation : Directional hypotheses assist in data analysis by directing researchers towards appropriate statistical tests and methods. Researchers can analyze the survey data to specifically test the predicted relationship or difference, enhancing the accuracy and reliability of their findings. The results can then be interpreted within the context of the directional hypothesis, providing more meaningful insights.

- Practical implications and decision-making : Directional hypotheses in surveys often have practical implications. When the predicted relationship or difference is confirmed, it informs decision-making processes, program development, or interventions. The survey findings based on directional hypotheses can guide organizations, policymakers, or practitioners in making informed choices to achieve desired outcomes.

- Replication and further research : Directional hypotheses in survey research contribute to the replication and extension of studies. Researchers can replicate the survey with different populations or contexts to assess the generalizability of the predicted relationships. Furthermore, if the directional hypothesis is supported, it encourages further research to explore underlying mechanisms or boundary conditions.

By incorporating directional hypotheses in survey research, researchers can align their objectives, design effective surveys, conduct focused data analysis, and derive practical insights. They provide a framework for organizing survey research and contribute to the accumulation of knowledge in the field.

Examples of research questions for directional hypothesis

Here are some examples of research questions that lend themselves to directional hypotheses:

- Does increased daily exercise lead to a decrease in body weight among sedentary adults?

- Is there a positive relationship between study hours and academic performance among college students?

- Does exposure to violent video games result in an increase in aggressive behavior among adolescents?

- Does the implementation of a mindfulness-based intervention lead to a reduction in stress levels among working professionals?

- Is there a difference in customer satisfaction between Product A and Product B, with Product A expected to have higher satisfaction ratings?

- Does the use of social media influence self-esteem levels, with higher social media usage associated with lower self-esteem?

- Is there a negative relationship between job satisfaction and employee turnover, indicating that lower job satisfaction leads to higher turnover rates?

- Does the administration of a specific medication result in a decrease in symptoms among individuals with a particular medical condition?

- Does increased access to early childhood education lead to improved cognitive development in preschool-aged children?

- Is there a difference in purchase intention between advertisements with celebrity endorsements and advertisements without, with celebrity endorsements expected to have a higher impact?

These research questions generate specific predictions about the direction of the relationship or difference between variables and can be tested using appropriate research methods and statistical analyses.

Definition of non-directional hypothesis

Non-directional hypotheses, also known as two-tailed hypotheses, are statements in research that indicate the presence of a relationship or difference between variables without specifying the direction of the effect. Instead of making predictions about the specific direction of the relationship or difference, non-directional hypotheses simply state that there is an association or distinction between the variables of interest.

Non-directional hypotheses are often used when there is no prior theoretical basis or clear expectation about the direction of the relationship. They leave the possibility open for either a positive or negative relationship, or for both groups to differ in some way without specifying which group will perform better or worse.

Advantages and utility of non-directional hypothesis

Non-directional hypotheses in survey s offer several advantages and utilities, providing flexibility and comprehensive analysis of survey data. Here are some of the key advantages and utilities of using non-directional hypotheses in surveys:

- Exploration of Relationships : Non-directional hypotheses allow researchers to explore and examine relationships between variables without assuming a specific direction. This is particularly useful in surveys where the relationship between variables may not be well-known or there may be conflicting evidence regarding the direction of the effect.

- Flexibility in Question Design : With non-directional hypotheses, survey questions can be designed to measure the relationship between variables without being biased towards a particular outcome. This flexibility allows researchers to collect data and analyze the results more objectively.

- Open to Unexpected Findings : Non-directional hypotheses enable researchers to be open to unexpected or surprising findings in survey data. By not committing to a specific direction of the effect, researchers can identify and explore relationships that may not have been initially anticipated, leading to new insights and discoveries.

- Comprehensive Analysis : Non-directional hypotheses promote comprehensive analysis of survey data by considering the possibility of an effect in either direction. Researchers can assess the magnitude and significance of relationships without limiting their analysis to only one possible outcome.

- S tatistical Validity : Non-directional hypotheses in surveys allow for the use of two-tailed statistical tests, which provide a more conservative and robust assessment of significance. Two-tailed tests consider both positive and negative deviations from the null hypothesis, ensuring accurate and reliable statistical analysis of survey data.

- Exploratory Research : Non-directional hypotheses are particularly useful in exploratory research, where the goal is to gather initial insights and generate hypotheses. Surveys with non-directional hypotheses can help researchers explore various relationships and identify patterns that can guide further research or hypothesis development.

It is worth noting that the choice between directional and non-directional hypotheses in surveys depends on the research objectives, existing knowledge, and the specific variables being investigated. Researchers should carefully consider the advantages and limitations of each approach and select the one that aligns best with their research goals and survey design.

- Share with others

- Twitter Twitter Icon

- LinkedIn LinkedIn Icon

Related posts

How to implement nps surveys: a step-by-step guide, 15 best website survey questions to ask your visitors, how to write a good survey introduction, 7 best ai survey generators, multiple choice questions: types, examples & samples, how to make a gdpr compliant survey, get answers today.

- No credit card required

- No time limit on Free plan

You can modify this template in every possible way.

All templates work great on every device.

How to Develop a Good Research Hypothesis

The story of a research study begins by asking a question. Researchers all around the globe are asking curious questions and formulating research hypothesis. However, whether the research study provides an effective conclusion depends on how well one develops a good research hypothesis. Research hypothesis examples could help researchers get an idea as to how to write a good research hypothesis.

This blog will help you understand what is a research hypothesis, its characteristics and, how to formulate a research hypothesis

Table of Contents

What is Hypothesis?

Hypothesis is an assumption or an idea proposed for the sake of argument so that it can be tested. It is a precise, testable statement of what the researchers predict will be outcome of the study. Hypothesis usually involves proposing a relationship between two variables: the independent variable (what the researchers change) and the dependent variable (what the research measures).

What is a Research Hypothesis?

Research hypothesis is a statement that introduces a research question and proposes an expected result. It is an integral part of the scientific method that forms the basis of scientific experiments. Therefore, you need to be careful and thorough when building your research hypothesis. A minor flaw in the construction of your hypothesis could have an adverse effect on your experiment. In research, there is a convention that the hypothesis is written in two forms, the null hypothesis, and the alternative hypothesis (called the experimental hypothesis when the method of investigation is an experiment).

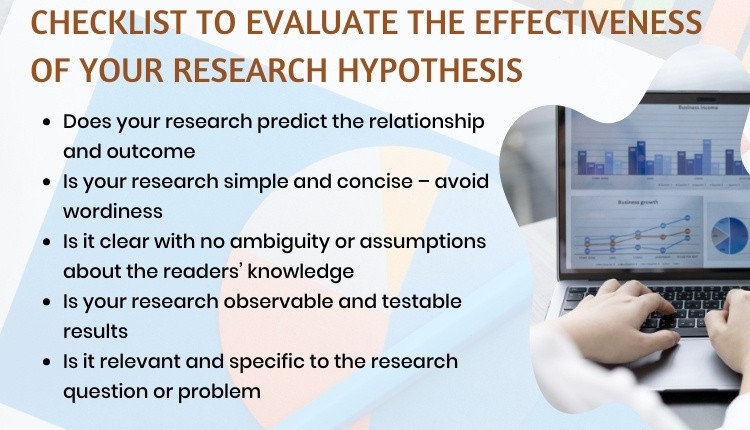

Characteristics of a Good Research Hypothesis

As the hypothesis is specific, there is a testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. You may consider drawing hypothesis from previously published research based on the theory.

A good research hypothesis involves more effort than just a guess. In particular, your hypothesis may begin with a question that could be further explored through background research.

To help you formulate a promising research hypothesis, you should ask yourself the following questions:

- Is the language clear and focused?

- What is the relationship between your hypothesis and your research topic?

- Is your hypothesis testable? If yes, then how?

- What are the possible explanations that you might want to explore?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate your variables without hampering the ethical standards?

- Does your research predict the relationship and outcome?

- Is your research simple and concise (avoids wordiness)?

- Is it clear with no ambiguity or assumptions about the readers’ knowledge

- Is your research observable and testable results?

- Is it relevant and specific to the research question or problem?

The questions listed above can be used as a checklist to make sure your hypothesis is based on a solid foundation. Furthermore, it can help you identify weaknesses in your hypothesis and revise it if necessary.

Source: Educational Hub

How to formulate a research hypothesis.

A testable hypothesis is not a simple statement. It is rather an intricate statement that needs to offer a clear introduction to a scientific experiment, its intentions, and the possible outcomes. However, there are some important things to consider when building a compelling hypothesis.

1. State the problem that you are trying to solve.

Make sure that the hypothesis clearly defines the topic and the focus of the experiment.

2. Try to write the hypothesis as an if-then statement.

Follow this template: If a specific action is taken, then a certain outcome is expected.

3. Define the variables

Independent variables are the ones that are manipulated, controlled, or changed. Independent variables are isolated from other factors of the study.

Dependent variables , as the name suggests are dependent on other factors of the study. They are influenced by the change in independent variable.

4. Scrutinize the hypothesis

Evaluate assumptions, predictions, and evidence rigorously to refine your understanding.

Types of Research Hypothesis

The types of research hypothesis are stated below:

1. Simple Hypothesis

It predicts the relationship between a single dependent variable and a single independent variable.

2. Complex Hypothesis

It predicts the relationship between two or more independent and dependent variables.

3. Directional Hypothesis

It specifies the expected direction to be followed to determine the relationship between variables and is derived from theory. Furthermore, it implies the researcher’s intellectual commitment to a particular outcome.

4. Non-directional Hypothesis

It does not predict the exact direction or nature of the relationship between the two variables. The non-directional hypothesis is used when there is no theory involved or when findings contradict previous research.

5. Associative and Causal Hypothesis

The associative hypothesis defines interdependency between variables. A change in one variable results in the change of the other variable. On the other hand, the causal hypothesis proposes an effect on the dependent due to manipulation of the independent variable.

6. Null Hypothesis

Null hypothesis states a negative statement to support the researcher’s findings that there is no relationship between two variables. There will be no changes in the dependent variable due the manipulation of the independent variable. Furthermore, it states results are due to chance and are not significant in terms of supporting the idea being investigated.

7. Alternative Hypothesis

It states that there is a relationship between the two variables of the study and that the results are significant to the research topic. An experimental hypothesis predicts what changes will take place in the dependent variable when the independent variable is manipulated. Also, it states that the results are not due to chance and that they are significant in terms of supporting the theory being investigated.

Research Hypothesis Examples of Independent and Dependent Variables

Research Hypothesis Example 1 The greater number of coal plants in a region (independent variable) increases water pollution (dependent variable). If you change the independent variable (building more coal factories), it will change the dependent variable (amount of water pollution).

Research Hypothesis Example 2 What is the effect of diet or regular soda (independent variable) on blood sugar levels (dependent variable)? If you change the independent variable (the type of soda you consume), it will change the dependent variable (blood sugar levels)

You should not ignore the importance of the above steps. The validity of your experiment and its results rely on a robust testable hypothesis. Developing a strong testable hypothesis has few advantages, it compels us to think intensely and specifically about the outcomes of a study. Consequently, it enables us to understand the implication of the question and the different variables involved in the study. Furthermore, it helps us to make precise predictions based on prior research. Hence, forming a hypothesis would be of great value to the research. Here are some good examples of testable hypotheses.

More importantly, you need to build a robust testable research hypothesis for your scientific experiments. A testable hypothesis is a hypothesis that can be proved or disproved as a result of experimentation.

Importance of a Testable Hypothesis

To devise and perform an experiment using scientific method, you need to make sure that your hypothesis is testable. To be considered testable, some essential criteria must be met:

- There must be a possibility to prove that the hypothesis is true.

- There must be a possibility to prove that the hypothesis is false.

- The results of the hypothesis must be reproducible.

Without these criteria, the hypothesis and the results will be vague. As a result, the experiment will not prove or disprove anything significant.

What are your experiences with building hypotheses for scientific experiments? What challenges did you face? How did you overcome these challenges? Please share your thoughts with us in the comments section.

Frequently Asked Questions

The steps to write a research hypothesis are: 1. Stating the problem: Ensure that the hypothesis defines the research problem 2. Writing a hypothesis as an 'if-then' statement: Include the action and the expected outcome of your study by following a ‘if-then’ structure. 3. Defining the variables: Define the variables as Dependent or Independent based on their dependency to other factors. 4. Scrutinizing the hypothesis: Identify the type of your hypothesis

Hypothesis testing is a statistical tool which is used to make inferences about a population data to draw conclusions for a particular hypothesis.

Hypothesis in statistics is a formal statement about the nature of a population within a structured framework of a statistical model. It is used to test an existing hypothesis by studying a population.

Research hypothesis is a statement that introduces a research question and proposes an expected result. It forms the basis of scientific experiments.

The different types of hypothesis in research are: • Null hypothesis: Null hypothesis is a negative statement to support the researcher’s findings that there is no relationship between two variables. • Alternate hypothesis: Alternate hypothesis predicts the relationship between the two variables of the study. • Directional hypothesis: Directional hypothesis specifies the expected direction to be followed to determine the relationship between variables. • Non-directional hypothesis: Non-directional hypothesis does not predict the exact direction or nature of the relationship between the two variables. • Simple hypothesis: Simple hypothesis predicts the relationship between a single dependent variable and a single independent variable. • Complex hypothesis: Complex hypothesis predicts the relationship between two or more independent and dependent variables. • Associative and casual hypothesis: Associative and casual hypothesis predicts the relationship between two or more independent and dependent variables. • Empirical hypothesis: Empirical hypothesis can be tested via experiments and observation. • Statistical hypothesis: A statistical hypothesis utilizes statistical models to draw conclusions about broader populations.

Wow! You really simplified your explanation that even dummies would find it easy to comprehend. Thank you so much.

Thanks a lot for your valuable guidance.

I enjoy reading the post. Hypotheses are actually an intrinsic part in a study. It bridges the research question and the methodology of the study.

Useful piece!

This is awesome.Wow.

It very interesting to read the topic, can you guide me any specific example of hypothesis process establish throw the Demand and supply of the specific product in market

Nicely explained

It is really a useful for me Kindly give some examples of hypothesis

It was a well explained content ,can you please give me an example with the null and alternative hypothesis illustrated

clear and concise. thanks.

So Good so Amazing

Good to learn

Thanks a lot for explaining to my level of understanding

Explained well and in simple terms. Quick read! Thank you

It awesome. It has really positioned me in my research project

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Reporting Research

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for data interpretation

In research, choosing the right approach to understand data is crucial for deriving meaningful insights.…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right approach

The process of choosing the right research design can put ourselves at the crossroads of…

- Industry News

COPE Forum Discussion Highlights Challenges and Urges Clarity in Institutional Authorship Standards

The COPE forum discussion held in December 2023 initiated with a fundamental question — is…

- Career Corner

Unlocking the Power of Networking in Academic Conferences

Embarking on your first academic conference experience? Fear not, we got you covered! Academic conferences…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Research recommendations play a crucial role in guiding scholars and researchers toward fruitful avenues of…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right…

How to Design Effective Research Questionnaires for Robust Findings

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

The Craft of Writing a Strong Hypothesis

Table of Contents

Writing a hypothesis is one of the essential elements of a scientific research paper. It needs to be to the point, clearly communicating what your research is trying to accomplish. A blurry, drawn-out, or complexly-structured hypothesis can confuse your readers. Or worse, the editor and peer reviewers.

A captivating hypothesis is not too intricate. This blog will take you through the process so that, by the end of it, you have a better idea of how to convey your research paper's intent in just one sentence.

What is a Hypothesis?

The first step in your scientific endeavor, a hypothesis, is a strong, concise statement that forms the basis of your research. It is not the same as a thesis statement , which is a brief summary of your research paper .

The sole purpose of a hypothesis is to predict your paper's findings, data, and conclusion. It comes from a place of curiosity and intuition . When you write a hypothesis, you're essentially making an educated guess based on scientific prejudices and evidence, which is further proven or disproven through the scientific method.

The reason for undertaking research is to observe a specific phenomenon. A hypothesis, therefore, lays out what the said phenomenon is. And it does so through two variables, an independent and dependent variable.

The independent variable is the cause behind the observation, while the dependent variable is the effect of the cause. A good example of this is “mixing red and blue forms purple.” In this hypothesis, mixing red and blue is the independent variable as you're combining the two colors at your own will. The formation of purple is the dependent variable as, in this case, it is conditional to the independent variable.

Different Types of Hypotheses

Types of hypotheses

Some would stand by the notion that there are only two types of hypotheses: a Null hypothesis and an Alternative hypothesis. While that may have some truth to it, it would be better to fully distinguish the most common forms as these terms come up so often, which might leave you out of context.

Apart from Null and Alternative, there are Complex, Simple, Directional, Non-Directional, Statistical, and Associative and casual hypotheses. They don't necessarily have to be exclusive, as one hypothesis can tick many boxes, but knowing the distinctions between them will make it easier for you to construct your own.

1. Null hypothesis

A null hypothesis proposes no relationship between two variables. Denoted by H 0 , it is a negative statement like “Attending physiotherapy sessions does not affect athletes' on-field performance.” Here, the author claims physiotherapy sessions have no effect on on-field performances. Even if there is, it's only a coincidence.

2. Alternative hypothesis

Considered to be the opposite of a null hypothesis, an alternative hypothesis is donated as H1 or Ha. It explicitly states that the dependent variable affects the independent variable. A good alternative hypothesis example is “Attending physiotherapy sessions improves athletes' on-field performance.” or “Water evaporates at 100 °C. ” The alternative hypothesis further branches into directional and non-directional.

- Directional hypothesis: A hypothesis that states the result would be either positive or negative is called directional hypothesis. It accompanies H1 with either the ‘<' or ‘>' sign.

- Non-directional hypothesis: A non-directional hypothesis only claims an effect on the dependent variable. It does not clarify whether the result would be positive or negative. The sign for a non-directional hypothesis is ‘≠.'

3. Simple hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a statement made to reflect the relation between exactly two variables. One independent and one dependent. Consider the example, “Smoking is a prominent cause of lung cancer." The dependent variable, lung cancer, is dependent on the independent variable, smoking.

4. Complex hypothesis

In contrast to a simple hypothesis, a complex hypothesis implies the relationship between multiple independent and dependent variables. For instance, “Individuals who eat more fruits tend to have higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.” The independent variable is eating more fruits, while the dependent variables are higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.

5. Associative and casual hypothesis

Associative and casual hypotheses don't exhibit how many variables there will be. They define the relationship between the variables. In an associative hypothesis, changing any one variable, dependent or independent, affects others. In a casual hypothesis, the independent variable directly affects the dependent.

6. Empirical hypothesis

Also referred to as the working hypothesis, an empirical hypothesis claims a theory's validation via experiments and observation. This way, the statement appears justifiable and different from a wild guess.

Say, the hypothesis is “Women who take iron tablets face a lesser risk of anemia than those who take vitamin B12.” This is an example of an empirical hypothesis where the researcher the statement after assessing a group of women who take iron tablets and charting the findings.

7. Statistical hypothesis

The point of a statistical hypothesis is to test an already existing hypothesis by studying a population sample. Hypothesis like “44% of the Indian population belong in the age group of 22-27.” leverage evidence to prove or disprove a particular statement.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

Writing a hypothesis is essential as it can make or break your research for you. That includes your chances of getting published in a journal. So when you're designing one, keep an eye out for these pointers:

- A research hypothesis has to be simple yet clear to look justifiable enough.

- It has to be testable — your research would be rendered pointless if too far-fetched into reality or limited by technology.

- It has to be precise about the results —what you are trying to do and achieve through it should come out in your hypothesis.

- A research hypothesis should be self-explanatory, leaving no doubt in the reader's mind.

- If you are developing a relational hypothesis, you need to include the variables and establish an appropriate relationship among them.

- A hypothesis must keep and reflect the scope for further investigations and experiments.

Separating a Hypothesis from a Prediction

Outside of academia, hypothesis and prediction are often used interchangeably. In research writing, this is not only confusing but also incorrect. And although a hypothesis and prediction are guesses at their core, there are many differences between them.

A hypothesis is an educated guess or even a testable prediction validated through research. It aims to analyze the gathered evidence and facts to define a relationship between variables and put forth a logical explanation behind the nature of events.

Predictions are assumptions or expected outcomes made without any backing evidence. They are more fictionally inclined regardless of where they originate from.

For this reason, a hypothesis holds much more weight than a prediction. It sticks to the scientific method rather than pure guesswork. "Planets revolve around the Sun." is an example of a hypothesis as it is previous knowledge and observed trends. Additionally, we can test it through the scientific method.

Whereas "COVID-19 will be eradicated by 2030." is a prediction. Even though it results from past trends, we can't prove or disprove it. So, the only way this gets validated is to wait and watch if COVID-19 cases end by 2030.

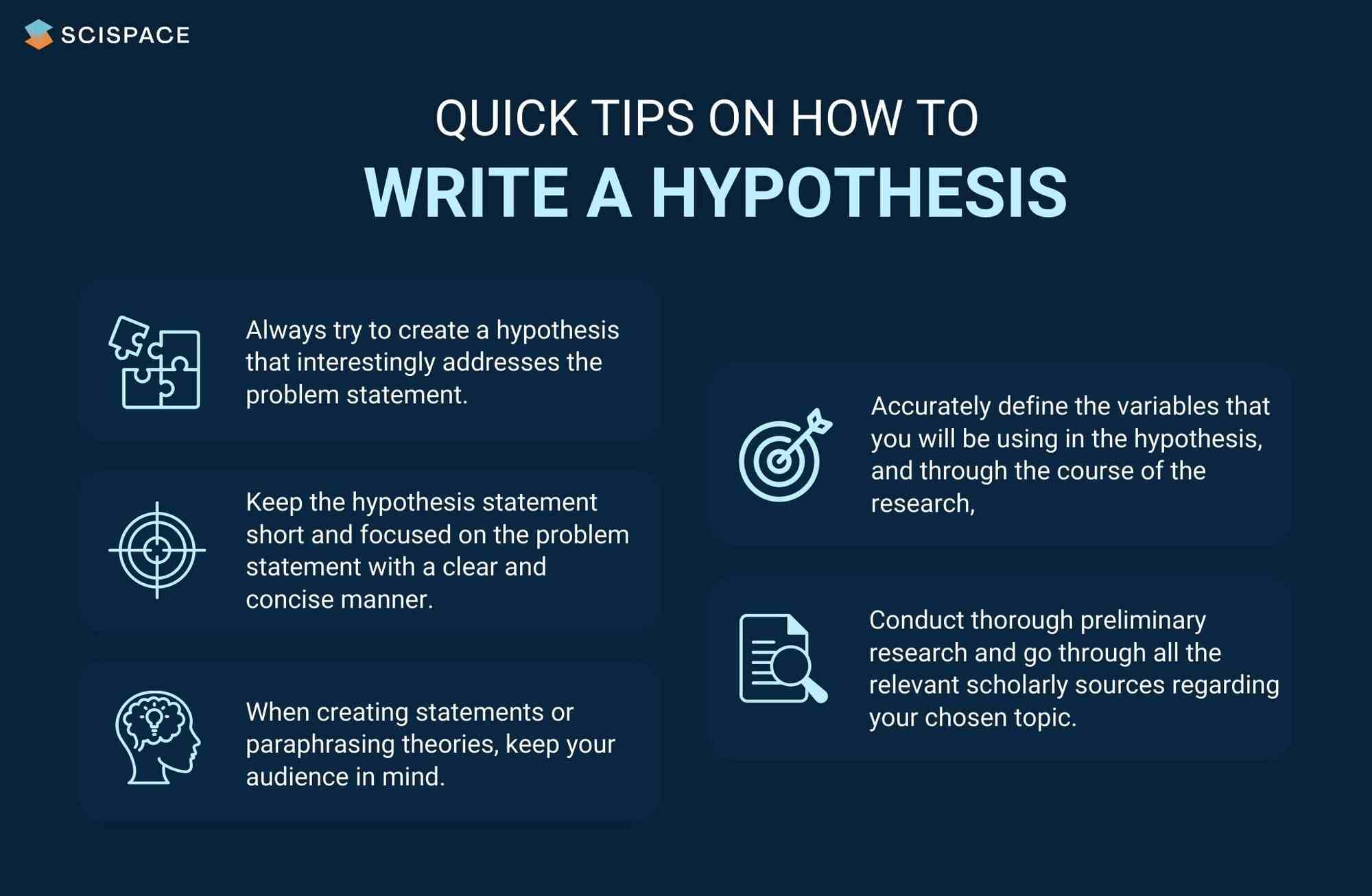

Finally, How to Write a Hypothesis

Quick tips on writing a hypothesis

1. Be clear about your research question

A hypothesis should instantly address the research question or the problem statement. To do so, you need to ask a question. Understand the constraints of your undertaken research topic and then formulate a simple and topic-centric problem. Only after that can you develop a hypothesis and further test for evidence.

2. Carry out a recce

Once you have your research's foundation laid out, it would be best to conduct preliminary research. Go through previous theories, academic papers, data, and experiments before you start curating your research hypothesis. It will give you an idea of your hypothesis's viability or originality.

Making use of references from relevant research papers helps draft a good research hypothesis. SciSpace Discover offers a repository of over 270 million research papers to browse through and gain a deeper understanding of related studies on a particular topic. Additionally, you can use SciSpace Copilot , your AI research assistant, for reading any lengthy research paper and getting a more summarized context of it. A hypothesis can be formed after evaluating many such summarized research papers. Copilot also offers explanations for theories and equations, explains paper in simplified version, allows you to highlight any text in the paper or clip math equations and tables and provides a deeper, clear understanding of what is being said. This can improve the hypothesis by helping you identify potential research gaps.

3. Create a 3-dimensional hypothesis

Variables are an essential part of any reasonable hypothesis. So, identify your independent and dependent variable(s) and form a correlation between them. The ideal way to do this is to write the hypothetical assumption in the ‘if-then' form. If you use this form, make sure that you state the predefined relationship between the variables.

In another way, you can choose to present your hypothesis as a comparison between two variables. Here, you must specify the difference you expect to observe in the results.

4. Write the first draft

Now that everything is in place, it's time to write your hypothesis. For starters, create the first draft. In this version, write what you expect to find from your research.

Clearly separate your independent and dependent variables and the link between them. Don't fixate on syntax at this stage. The goal is to ensure your hypothesis addresses the issue.

5. Proof your hypothesis

After preparing the first draft of your hypothesis, you need to inspect it thoroughly. It should tick all the boxes, like being concise, straightforward, relevant, and accurate. Your final hypothesis has to be well-structured as well.

Research projects are an exciting and crucial part of being a scholar. And once you have your research question, you need a great hypothesis to begin conducting research. Thus, knowing how to write a hypothesis is very important.

Now that you have a firmer grasp on what a good hypothesis constitutes, the different kinds there are, and what process to follow, you will find it much easier to write your hypothesis, which ultimately helps your research.

Now it's easier than ever to streamline your research workflow with SciSpace Discover . Its integrated, comprehensive end-to-end platform for research allows scholars to easily discover, write and publish their research and fosters collaboration.

It includes everything you need, including a repository of over 270 million research papers across disciplines, SEO-optimized summaries and public profiles to show your expertise and experience.

If you found these tips on writing a research hypothesis useful, head over to our blog on Statistical Hypothesis Testing to learn about the top researchers, papers, and institutions in this domain.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. what is the definition of hypothesis.

According to the Oxford dictionary, a hypothesis is defined as “An idea or explanation of something that is based on a few known facts, but that has not yet been proved to be true or correct”.

2. What is an example of hypothesis?

The hypothesis is a statement that proposes a relationship between two or more variables. An example: "If we increase the number of new users who join our platform by 25%, then we will see an increase in revenue."

3. What is an example of null hypothesis?

A null hypothesis is a statement that there is no relationship between two variables. The null hypothesis is written as H0. The null hypothesis states that there is no effect. For example, if you're studying whether or not a particular type of exercise increases strength, your null hypothesis will be "there is no difference in strength between people who exercise and people who don't."

4. What are the types of research?

• Fundamental research

• Applied research

• Qualitative research

• Quantitative research

• Mixed research

• Exploratory research

• Longitudinal research

• Cross-sectional research

• Field research

• Laboratory research

• Fixed research

• Flexible research

• Action research

• Policy research

• Classification research

• Comparative research

• Causal research

• Inductive research

• Deductive research

5. How to write a hypothesis?

• Your hypothesis should be able to predict the relationship and outcome.

• Avoid wordiness by keeping it simple and brief.

• Your hypothesis should contain observable and testable outcomes.

• Your hypothesis should be relevant to the research question.

6. What are the 2 types of hypothesis?

• Null hypotheses are used to test the claim that "there is no difference between two groups of data".

• Alternative hypotheses test the claim that "there is a difference between two data groups".

7. Difference between research question and research hypothesis?

A research question is a broad, open-ended question you will try to answer through your research. A hypothesis is a statement based on prior research or theory that you expect to be true due to your study. Example - Research question: What are the factors that influence the adoption of the new technology? Research hypothesis: There is a positive relationship between age, education and income level with the adoption of the new technology.

8. What is plural for hypothesis?

The plural of hypothesis is hypotheses. Here's an example of how it would be used in a statement, "Numerous well-considered hypotheses are presented in this part, and they are supported by tables and figures that are well-illustrated."

9. What is the red queen hypothesis?

The red queen hypothesis in evolutionary biology states that species must constantly evolve to avoid extinction because if they don't, they will be outcompeted by other species that are evolving. Leigh Van Valen first proposed it in 1973; since then, it has been tested and substantiated many times.

10. Who is known as the father of null hypothesis?

The father of the null hypothesis is Sir Ronald Fisher. He published a paper in 1925 that introduced the concept of null hypothesis testing, and he was also the first to use the term itself.

11. When to reject null hypothesis?

You need to find a significant difference between your two populations to reject the null hypothesis. You can determine that by running statistical tests such as an independent sample t-test or a dependent sample t-test. You should reject the null hypothesis if the p-value is less than 0.05.

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

The What, Why and How of Directional Hypotheses

In the world of research and science, hypotheses serve as the starting blocks, setting the pace for the entire study. One such hypothesis type is the directional hypothesis. Here, we delve into what exactly a directional hypothesis is, its significance, and the nitty-gritty of formulating one, followed by pitfalls to avoid and how to apply it in practical situations.

The What: Understanding the Concept of a Directional Hypothesis

A directional hypothesis, often referred to as a one-tailed hypothesis, is an essential part of research that predicts the expected outcomes and their directions. The intriguing aspect here is that it goes beyond merely predicting a difference or connection, it actually suggests the direction that this difference or connection will take.

Let's break it down a bit. If the directional hypothesis is positive, this suggests that the variables being studied are expected to either increase or decrease in unison. On the other hand, if the hypothesis is negative, it implies that the variables will move in opposite directions - as one variable ascends, the other will descend, and vice versa.

This intricacy gives the directional hypothesis its unique value in research and offers a fascinating aspect of study predictions. With a clearer understanding of what a directional hypothesis is, we can now delve into why it holds such significance in research and how to construct one effectively.

The Why: The Significance of a Directional Hypothesis in Research

Ever wondered why the directional hypothesis is held in such high regard? The secret lies in its unique blend of precision and specificity. It provides an edge by paving the way for a more concentrated and focused investigation. Essentially, it helps scientists to have an informed prediction of the correlation between variables, underpinned by prior research, theoretical assumptions, or logical reasoning. This isn't just a game of guesswork but a highly credible route to more definitive and dependable results. As they say, the devil is in the detail. By using a directional hypothesis, we are able to dive into the intricate and exciting world of research, adding a robust foundation to our endeavours, ultimately boosting the credibility and reliability of our findings. By standing firmly on the shoulders of the directional hypothesis, we allow our research to gaze further and see clearer.

The How: Constructing a Strong Directional Hypothesis

Crafting a robust directional hypothesis is indeed a craft that requires a blend of art and science. This process starts with a comprehensive exploration of related literature, immersing oneself in the reservoir of knowledge that already exists around your subject of interest. This immersion enables you to soak up invaluable insights, creating a well-informed base from which to make educated predictions about the directionality between your variables of interest.

The process doesn't stop at a literature review. It's also imperative to fully comprehend your subject. Dive deeper into the layers of your topic, unpick the threads, and question the status quo. Understand what drives your variables, how they may interact, and why you anticipate they'll behave in a certain way.

Then, it's time to define your variables clearly and precisely. This might sound simple, but it's crucial to be as accurate as possible. By doing so, you not only ensure a clear understanding of what you are measuring, but you also set clear parameters for your research.

Following that, comes the exciting part - predicting the direction of the relationship between your variables. This prediction should not be a wild guess, but an informed forecast grounded in your literature review, understanding of the subject, and clear definition of variables.

Finally, remember that a directional hypothesis is not set in stone. It is, by definition, a hypothesis - a proposed explanation or prediction that is subject to testing and verification. So, don’t be disheartened if your directional hypothesis doesn’t pan out as expected. Instead, see it as an opportunity to delve further, learn more and further the boundaries of knowledge in your field. After all, research is not just about confirming hypotheses, but also about the thrill of exploration, discovery, and ultimately, growth.

Pitfalls to Avoid When Formulating a Directional Hypothesis

Crafting a directional hypothesis isn't a walk in the park. A few common missteps can muddy the waters and limit the effectiveness of your hypothesis. The first stumbling block that researchers should watch out for is making baseless presumptions. Although predicting the course of the relationship between variables is integral to a directional hypothesis, this prediction should be firmly rooted in evidence, not just whims or gut feelings.

Secondly, steer clear of being excessively rigid with your hypothesis. Remember, it's a guide, not gospel truth. Science is about exploration, about finding out, about being open to unexpected outcomes. If your hypothesis does not match the results, that's not failure; it's a chance to learn and expand your understanding.

Avoid creating an overly complex hypothesis. Simplicity is the name of the game. You want your hypothesis to be clear, concise, and comprehensible, not wrapped in jargon and unnecessary complexities.

Lastly, ensure that your directional hypothesis is testable. It's not enough to merely state a prediction; it needs to be something you can verify empirically. If it can't be tested, it's not a viable hypothesis. So, when creating your directional hypothesis, be mindful to keep it within the realm of testable claims.

Remember, falling into these traps can derail your research and limit the value of your findings. By keeping these pitfalls at bay, you are better equipped to navigate the fascinating labyrinth of research, while contributing to a deeper understanding of your field. Happy hypothesising!

Putting it All Together: Applying a Directional Hypothesis in Practice

When it comes to applying a directional hypothesis, the real fun begins as you put your prediction to the test using appropriate research methodologies and statistical techniques. Let's put this into perspective using an example. Suppose you're exploring the effect of physical activity on people's mood. Your directional hypothesis might suggest that engaging in exercise would result in an improvement in mood ratings.

To test this hypothesis, you could employ a repeated-measures design. Here, you measure the moods of your participants before they start the exercise routine and then again after they've completed it. If the data reveals an uplift in positive mood ratings post-exercise, you would have empirical evidence to support your directional hypothesis.

However, bear in mind that your findings might not always corroborate your prediction. And that's the beauty of research! Contradictory findings don't necessarily signify failure. Instead, they open up new avenues of inquiry, challenging us to refine our understanding and fuel our intellectual curiosity. Therefore, whether your directional hypothesis is proven correct or not, it still serves a valuable purpose by guiding your exploration and contributing to the ever-evolving body of knowledge in your field. So, go ahead and plunge into the exciting world of research with your well-crafted directional hypothesis, ready to embrace whatever comes your way with open arms. Happy researching!

Directional Hypothesis

Definition:

A directional hypothesis is a specific type of hypothesis statement in which the researcher predicts the direction or effect of the relationship between two variables.

Key Features

1. Predicts direction:

Unlike a non-directional hypothesis, which simply states that there is a relationship between two variables, a directional hypothesis specifies the expected direction of the relationship.

2. Involves one-tailed test:

Directional hypotheses typically require a one-tailed statistical test, as they are concerned with whether the relationship is positive or negative, rather than simply whether a relationship exists.

3. Example:

An example of a directional hypothesis would be: “Increasing levels of exercise will result in greater weight loss.”

4. Researcher’s prior belief:

A directional hypothesis is often formed based on the researcher’s prior knowledge, theoretical understanding, or previous empirical evidence relating to the variables under investigation.

5. Confirmatory nature:

Directional hypotheses are considered confirmatory, as they provide a specific prediction that can be tested statistically, allowing researchers to either support or reject the hypothesis.

6. Advantages and disadvantages:

Directional hypotheses help focus the research by explicitly stating the expected relationship, but they can also limit exploration of alternative explanations or unexpected findings.

Final dates! Join the tutor2u subject teams in London for a day of exam technique and revision at the cinema. Learn more →

Reference Library

Collections

- See what's new

- All Resources

- Student Resources

- Assessment Resources

- Teaching Resources

- CPD Courses

- Livestreams

Study notes, videos, interactive activities and more!

Psychology news, insights and enrichment

Currated collections of free resources

Browse resources by topic

- All Psychology Resources

Resource Selections

Currated lists of resources

Directional Hypothesis

A directional hypothesis is a one-tailed hypothesis that states the direction of the difference or relationship (e.g. boys are more helpful than girls).

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share by Email

Research Methods: MCQ Revision Test 1 for AQA A Level Psychology

Topic Videos

Example Answers for Research Methods: A Level Psychology, Paper 2, June 2018 (AQA)

Exam Support

Example Answer for Question 14 Paper 2: AS Psychology, June 2017 (AQA)

Model answer for question 11 paper 2: as psychology, june 2016 (aqa), a level psychology topic quiz - research methods.

Quizzes & Activities

Our subjects

- › Criminology

- › Economics

- › Geography

- › Health & Social Care

- › Psychology

- › Sociology

- › Teaching & learning resources

- › Student revision workshops

- › Online student courses

- › CPD for teachers

- › Livestreams

- › Teaching jobs

Boston House, 214 High Street, Boston Spa, West Yorkshire, LS23 6AD Tel: 01937 848885