Essay on Importance of Voting in Democracy

Students are often asked to write an essay on Importance of Voting in Democracy in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Importance of Voting in Democracy

The essence of democracy.

Voting is the cornerstone of a democracy. It’s the tool that allows citizens to choose their leaders and voice their opinions on important issues.

Why Voting Matters

By voting, you get to influence the society you live in. It’s a way to ensure that your interests are represented in government.

The Power of Each Vote

Every vote counts. In many cases, elections have been decided by just a few votes. Therefore, your vote can make a real difference.

In summary, voting is a crucial component of democracy. So, always exercise your right to vote!

250 Words Essay on Importance of Voting in Democracy

Democracy is often defined as ‘government of the people, by the people, for the people.’ It is a system that bestows power in the hands of the citizens to choose their representatives. The cornerstone of this power lies in the act of voting.

The Role of Voting

Voting is not just a right, but a duty and a moral responsibility. It is the most direct and effective way of participating in the democratic process. The vote of every citizen contributes to the formation of a government and the trajectory of the nation.

Empowering the Masses

Voting gives citizens the power to express their opinion and choose leaders who align with their views. It is a tool to effect change and ensure the government reflects the will of the people. Voting also empowers marginalized groups, providing an equal platform for their voices to be heard.

Accountability and Transparency

Voting ensures accountability and transparency in the democratic system. It acts as a check on the government, reminding them of their responsibility towards the electorate. If the government fails to deliver, voters have the power to change the administration in the next election.

The importance of voting in democracy cannot be overstated. It is the fundamental right and duty of every citizen to participate in this process. It is through voting that we shape our society, influence policies, and ensure the government serves the common good. By voting, we uphold the democratic values of freedom, equality, and justice.

500 Words Essay on Importance of Voting in Democracy

Introduction.

Democracy is a system of governance where citizens participate directly or indirectly in the decision-making process. At the heart of this system lies the act of voting, an essential tool through which citizens express their will, choose their leaders, and influence public policy. The importance of voting in a democratic society cannot be overstated as it forms the basis for the exercise of political and civil rights.

The Pillar of Democratic Governance

Voting is a fundamental pillar of democratic governance. It is the mechanism through which citizens exercise their sovereignty and control over the government. By voting, citizens choose their representatives who will make laws, shape public policy, and steer the direction of the nation. This process ensures that the government is accountable to the people, and not the other way round. The act of voting is, therefore, a powerful expression of political freedom and self-determination.

Instrument for Social Change

Voting is not only a political act but also a tool for social change. It gives citizens the power to influence public policy and the direction of societal evolution. Through the ballot box, citizens can express their views on critical issues such as education, health, economy, and social justice. Voting, therefore, serves as a peaceful means of effecting change and shaping the society we want to live in.

Equality and Inclusivity

In a democracy, voting underscores the principle of equality. Regardless of social, economic, or cultural backgrounds, every citizen has an equal vote. This inclusivity strengthens social cohesion and fosters a sense of belonging among citizens. Moreover, it ensures that marginalized and underrepresented groups have a voice in the political process, thereby promoting social equity.

Responsibility of Citizenship

Voting is not just a right; it is a responsibility. By participating in elections, citizens contribute to the democratic process and the overall health of the political system. Abstaining from voting leads to a skewed representation, which may not reflect the true will of the people. Therefore, every vote counts, and each citizen ought to take this responsibility seriously.

In conclusion, the act of voting is a cornerstone of democracy, serving as a tool for change, a symbol of equality, and a responsibility of citizenship. It gives power to the people, ensuring that the government remains accountable and responsive to their needs. Hence, for a democracy to be truly representative and effective, it is essential that citizens understand the importance of voting and actively participate in the electoral process. The future of our democratic society depends on the collective action of informed and engaged citizens.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Electoral Literacy for Stronger Democracy

- Essay on Democracy in Sri Lanka

- Essay on New Delhi

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

Voting is Still One of Our Most Powerful Tools For Change

John freeman on how every election is a chance to rebuild.

A vote is the difference between a citizen and a subject. The powerful used to be able to say to all and sundry, You must; a vote says to the powerful, No, you must listen.

Thus begins, in many places, the modern world.

For a long time the powers that be have turned an ear toward the people—because every two to four years, those voters are waiting for them. Everywhere the vote has traveled, so has a sense of accountability. If you are greedy or corrupt or abuse your power or ignore the needs of citizens, there’s a chance you will be voted out.

So there has been a move, from the very beginning of the vote, to restrict who has the power to use it—to plane down the realm of responsibility. From the beginning, in most places, it was just men with land who could vote; then it was just men; then it’s all those men plus women. The history of many liberal democracies is this story—at least in part: the drive toward greater inclusion.

Now we are swinging the other way. Most of our societies are so top-heavy—literally crumbling under the weight of an oligarch class whose interests are vastly overrepresented—that the only way for them to function is to reduce or even cancel the vote. Were people to vote at higher percentages, power would lose. So the vote itself has to come under attack.

Some of these assaults are soft and accomplished through suggestion. A foreign power or even a candidate may put out that the vote is rigged, stoking the already understandable apathy. In many two-party systems, the candidates themselves play a game in debates, provoking just enough apathy to shave off voters from each other’s total. These subtractions can be accomplished with targeted messaging, too.

Apathy, however, is not enough to keep the powers that be in their seats. So voters literally have to be removed from rolls. Those who haven’t voted in years are scrubbed from voter rolls; new laws are passed to make it harder to vote—paperwork is needed, appointments required. These rules target poor and overworked people, minorities, and those who have an unhappy relationship with the law’s surgical precision. Sometimes “accidents” happen: you turn up to vote and your name isn’t on the rolls. On it goes. Districts are drawn and redrawn, especially in America, to make it especially difficult for one of the parties to win. Both parties have used this tool. In some cases, the police are brought out: nothing turns some voters away from a polling center like two or three squad cars parked, lights flashing. False messages are spread about polling time, about laws. Polling stations are moved across town to someplace inconvenient. In one recent election, a candidate illegally installed cameras inside polling stations. In the worst cases, people are beaten, chased away. Called and threatened. The history of voter suppression is told through the bodies of citizens.

Voting isn’t entirely fair; it’s only a partially decent enterprise. Yet it’s the best one we’ve created for channeling civic participation.

The very first responsibility that comes with a vote, then, ought to be the awareness that it needs to be protected and constantly improved. A great many people are handed the right to vote, and it never occurs to them that it will be taken away. This fact needs to be taught to children—who have an instinct for fairness—when they first learn history and government. Many schoolbooks ask teachers to present the right to vote as an arrival point, a destiny of civic society, when in fact the vote is simply an element allowing a civic society to function. You corrode the vote and hope will go dark.

Social scientists have found that in the absence of mandatory voting, some people will always need to be coaxed to the polls. They are old, or indigent, or depressed, or lonely, or apathetic, or just simply not engaged. They don’t have a ride, or they are too busy; they aren’t feeling well, or they have better things to do. So volunteers need to walk door-to-door to speak with them about upcoming elections. To agitate democracy to life. Imagine if instead of 55 percent of people voting, 90 percent did. Imagine if this were a celebratory part of every civics class taught round the world—children escorted by an adult or two around neighborhoods reminding people to vote, with no partisan agenda? What sort of accountability would a candidate face? Who can face down the civics equivalent of a Girl Scout cookie sale?

This kind of ceremony feels like just the beginning of a series of changes that could protect the vote. Any government that refuses to consider them is sending up a red flag. Why isn’t voting mandatory? Why isn’t registration automatic, say, when you get a driver’s license or a state ID? Why isn’t voting a national, state, and local holiday with required paid leave? Why isn’t public transportation free on voting days? Why can’t you vote online? Almost every single study of voter participation tells you these elements will increase turnout. Ask yourself why your local and federal governments are not following these simple questions.

The only answer to continued resistance to these changes is to run. To run yourself. Governments in some parts of the world know that the financial barriers to candidacy are often so high that they can essentially neglect their constituents. Indeed, there’s a cycle to voter suppression, one made worse by the corruption of elections through the politics of money. Certain populations are said not to vote, so candidates from those backgrounds and areas can’t run because they do not get the money to run. Even when they do get the money to run, their opponents know just which demographics to push down on, whom to scrub from voting rolls. The nakedness of this control mechanism can vandalize any kind of optimism.

Yet each election is a chance to rebuild a politics of optimism. Each candidate is a chance to defeat the cynical politics of voter suppression. So if your vote is being ignored, run. One of the extraordinary aftereffects of the Me Too movement has been a huge surge in female candidates. If government cannot be trusted to protect the rights of women, let alone a woman’s right to choose, then the thing to do is to run. Nearly five hundred women ran for congressional primaries alone in 2018 in the United States, which led to the most diverse Congress ever elected, one that looks a lot more like the nation it represents. In a world knitted by social media and crowdsourced funding, smaller candidates have greater weapons than ever in elections. It is possible to run for office without taking major donations or beginning with enormous ad buys.

A cynic might say here that even if someone enters elected office with the noblest of intentions, the politics of power and money will eventually corrupt them. In a world in which most elected officials make terrible compromises, that may be so. Here’s why we need a revolution of how we approach civic life, though, and who gets to be involved. Imagine if in coming elections, candidates win who are not corrupted, who were themselves once voters so outraged they ran for office; imagine if a great many of them refused the kinds of strings-attached donations that have led us to the point we are in now, where elected officials say one thing and vote another way on key legislation. What if so many people like this get elected that it’s impossible to buy them all—also because they refuse. What would be possible then?

The ubiquity of money in politics today, especially in America, means that one of the most powerful statements a candidate can make is, I won’t take the money. Voters can signal their desire for this. Peer pressure can, in fact, drive it. Voters can also protest for it. Have you ever watched an election in which one candidate changes a position under duress so that their opponent holding it loses that advantage? With the right amount of protesting and public service ads and a strategic use of social media, voters can make it known that refusing dark money in elections is a must.

These types of changes are necessary to lend power back to the voter. A voter is a mighty thing; a single voter has decided elections. A single voter has led to sweeping social change. A single vote, in, say, a justice system ruling, has led to the overturning of some of the worst and most discriminating practices in many of our societies. A common judicial ruling tally is 5–4. That vote was made possible by your vote. A candidate who talks only of himself gives fair warning that he does not understand this fundamental truth. Change is always driven by and stems from people. The elected official—the person later seen as heroic—often has done something quite simple, decent, and just. People bring to politics an understanding of what they need and how they live. This should not be so hard. Yet society has shown that preserving this relationship requires constant vigilance and questioning. A vote is the most important way to ask, Are you hearing us?

__________________________________

From Dictionary of the Undoing by John Freeman. Used with the permission of Via MCD X FSG Originals.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

John Freeman

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

Meet the PhD Student Inventing a New Scientific Language in Welsh

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

Home — Essay Samples — Government & Politics — Voting — The Importance of Voting for Strengthening Democracy

The Importance of Voting for Strengthening Democracy

- Categories: Voting

About this sample

Words: 630 |

Published: Sep 5, 2023

Words: 630 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Shaping government policies, promoting representation and inclusivity, fostering civic participation, challenges and the importance of overcoming them.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: Government & Politics

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 591 words

4 pages / 1956 words

1 pages / 544 words

6 pages / 2506 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Voting

As the 2024 presidential election approaches, the Republican Party finds itself at a critical juncture, grappling with a series of ethical and democratic dilemmas that have the potential to shape the future of American politics. [...]

Compulsory voting is a topic that sparks fervent debate, challenging us to consider the role of civic duty, individual choice, and the overall health of a democratic society. This essay delves into the complexities surrounding [...]

I am a Political psychology of International Relations MSc Student who is interested in voting behaviour and the psychology behind why people vote the way they do. Research into the “Why” is very Sparse in International [...]

The Paper frameworks different policy disagreements and arguments about lowering the voting age to Sixteen. I feel the opposite about bringing down the democratic age to 16. As I would see it, 16-year-olds are basically not [...]

In the United States, the legal age for voting stands at eighteen, this is an age that has been lowered from twenty-one due to statue reform. Every citizen has the right to vote, yet so many choose not to. Especially in the 2008 [...]

Are 16-year-olds mature enough to vote? This question has sparked heated debates among policymakers, educators, and the public at large. In recent years, there has been a growing movement to lower the voting age from 18 to 16 in [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Open Search Search

- Information for Information For

To Increase the Youth Vote, Address the Why and the How

By Bita Mosallai

Young people don’t turn out for elections. Young people don’t care about their government. Our government doesn’t need young people’s voices. These are some statements that have been continuously pushed down our throats since our first government class in high school, before we could even understand what it meant to vote. Some young people have come to believe our voices do not matter because older politicians do not pay attention to the issues we are concerned about.

As a first-time voter who was heavily involved in a youth voter registration drive last year, I believe two approaches must be taken to strengthen the youth vote. First, we need to address the larger systematic issue of why young people don’t think voting is important and, second, we must provide guidance to young voters through peer-to peer-contact about how to vote.

This new generation—Generation Z—is more outspoken and politically conscious than ever. Yet as I continually speak with people my age, there is still frustration with our government. Young people argue their voice is not actually heard in the political process or that they feel powerless with how our government is set up. I tell them: Why can’t the answer be to change our government? If you don't like a politician, vote them out. If you wish to see a bill on the policy agenda, vote for the politician who you know will support that bill. One of the most important ways we can create change and a better future for ourselves is by voting, because that's how our government has been set up. We need to provide appropriate support to young voters through civic education and in-person guidance, so they can get to a place where that frustration turns into productive action.

I’ve met young people that have devoted their entire life to civic engagement and activism, but I’ve also met people who didn’t care enough to vote in a general election. But if you’ve spoken to any young person, you know that every single one of us has a belief we are passionate about. Now, not every single person is using their vote to act on their beliefs, which is problematic because voting is ultimately how our representatives are elected. We need to make youth see why voting matters to them; they need to see they are not just voting for the President, they are voting for Congress, governors, important ballot measures, state judicial candidates, etc. They need to see that protesting and pressuring politicians through other methods is effective, but ultimately, they need someone in office that aligns with their views because other methods beyond voting can only do so much.

While guiding youth on why voting is important, the how also matters. Working on a youth voter registration drive last year with the Student PIRGs helped me realize that the best way to support youth voters was by validating the inevitable challenges they will face. Voting is complicated, even though older and more experienced people, as well as elected officials, make it out to be something as easy as filling out a form. For young people voting can be new and intimidating, with rules, deadlines, and many guidelines in place for specific states. Last year, I recognized that along with many young people being newly eligible to vote, voting by mail was a new concept for even experienced voters, so people needed assistance more than ever. Supporting young people through the process, rather than leaving them to figure it out for themselves, also motivates young people to continue voting in the future.

Support becomes even more important when youth encounter all the information out there about politics and elections. I don’t believe that there is not enough accessible information; I believe there is too much information and resources, so voting becomes overwhelming. Simply googling how to sign up for a vote by mail ballot in Arizona took me through five different voter registration sites. All these different resources can be incredibly helpful if curated well, but they may intimidate voters further, and having one single voter registration tool and sticking with it could be one key to not confusing first-time voters.

While we work to streamline resources, first-time voters can benefit from in-person guidance. One of the best ways to make the process easier is by enlisting the help of knowledgeable people who can answer questions. In particular, having other young people who are willing to answer questions can be even more effective—peer-to-peer contact is powerful. I have heard stories from friends and acquaintances who recalled how they got far through the process of registering to vote or requesting a ballot, but didn’t complete an easy step or missed a deadline. But the biggest problem is that they never reached out for help. We need to support our peers if we want them to contribute their much-needed voices.

Voting is not this easy process where you just check the box for President. There are complex voting laws, research you have to do to become an informed citizen, and then you have to do the work to keep elected officials accountable. The process can be overwhelming, but if we wish to construct our ideal government, we need to contribute our voice. If we wish to see a future where the youth vote is robust, we need to provide additional support to young voters and convince them voting is the most effective way of creating change. Young people won’t vote unless they believe their voices are valuable, and they may give in to defeat unless we are out there to help them and remind them there are people watching and waiting for us to give up.

Bita Mosallai is a junior at the University of Arizona. She works with the Student PIRG on civic engagement, food insecurity, and environmental efforts. She aims to combine her passions of education and government in her future career.

Democracy Reform, One Ballot at a Time

- Joshua A. Douglas

The way our democracy operates is on the ballot this November. Voters do not just elect people to public office; they can also dictate the rules for elections through ballot initiatives in many states. From creating independent redistricting commissions to adopting campaign finance measures to expanding voter eligibility and changing the way we vote, voters in states and localities may fundamentally reshape our electoral processes. These efforts follow similar activity 2016 , when several localities enacted new rules to enhance their democratic processes. These positive measures provide a path forward in light of a conservative U.S. Supreme Court that has cabined voting rights and opened the door to more money in our campaigns . Passing these reforms will go a long way toward improving our system in a proactive manner. If faced with a challenge to one of these positive expansions, the Court should defer to the voters’ preferences.

In a forthcoming book, Vote for US: How to Take Back Our Elections and Change the Future of Voting , I chronicle the ongoing fight for positive voting reforms, highlighting the democracy champions who are on the ground in communities all over the country and are engaged in a grassroots effort to take back our democracy. Vote for US tells the stories of these amazing individuals, providing inspiration and ideas on how to achieve meaningful change in today’s harried political climate. Here, I want to highlight the efforts underway this November as well as sketch out why the reforms should pass constitutional muster if challenged in court.

Take the problem of redistricting. In most states, politicians themselves draw the lines every ten years, leading to unfairly drawn districts that entrench the current party in power. This is a bipartisan problem: Republicans in Wisconsin and Democrats in Maryland , to give just two examples, both draw lines to help their party in future elections. This results in not only protracted litigation, but also congressional delegations and state legislatures that do not truly reflect the will of the people.

But this November voters in four states —Colorado, Michigan, Missouri, and Utah— can ameliorate the problem by enacting independent redistricting commissions. This activity follows Ohio voters passing an initiative in May 2018 to create their own commission. These states would join a handful of others —Alaska, Arizona, California, Idaho, Montana, and Washington—that take the process of redistricting away from elected politicians. Some localities also use independent redistricting commissions to draw local lines, such as for city council. To be sure, independent redistricting commissions cannot overcome all consideration of politics in crafting legislative lines. Studies are also mixed as to whether independent redistricting commissions actually produce more competitive elections. That is partially because it is difficult to agree on what measures of a map’s performance indicate “success.” Yet taking explicitly political actors out of the process is surely a step in the right direction.

Voters in a few places will also consider whether to expand the electorate to more people. Currently Florida is one of four states that disenfranchise felons for life, which has a disproportionate effect on racial minorities. The Florida electorate, however, can change that on November 6 through Amendment 4 , which would restore the right to vote for all felons—except those convicted of murder or sexual offense—who have completed their sentence, parole, and probation. Enacting this state constitutional amendment, which requires 60 percent approval, would re-enfranchise over 1.4 million Floridians.

Other voter expansions are also afoot. Voters in Golden, Colorado will decide whether to lower the voting age for local elections to 16. Doing so would follow the action in localities in Maryland and California, which have opened the election process for 16- and 17-year-olds for local or school board elections. The D.C. City Council is also considering a similar proposal and early indications show that it has the support of a majority of council members. Lowering the voting age has many benefits : it can create a culture of democratic engagement early in life while young people are in the supportive environments of home and school and may increase voter turnout in the future as they age and become habitual voters. Psychologists have found that 16-year-olds are cognitively developed enough to be informed voters. Coupled with improved civics education , lowering the voting age—at least for local elections—offers immense promise.

Nevada voters will decide whether to join over a dozen other states in adopting automatic voter registration, where the state takes the onus of registering everyone, such as by using information from its motor vehicles database. This reform improves turnout by automatically putting more people on the rolls, eliminating a barrier for people who do not take the affirmative step of registering in time. Maryland voters will decide whether to adopt same-day registration, allowing individuals to register at the polls on Election Day. A proposal in Michigan would adopt several election-related reforms, including automatic voter registration, same-day registration, and no-excuse absentee voting.

Campaign finance reform is also on the ballot in a few places, including Missouri, South Dakota, Portland, Oregon, and Denver, Colorado. The reforms in Missouri and South Dakota would lower campaign contribution limits and impose other ethics rules. The Portland measure would also impose contribution and spending limits for city elections. The Denver proposal would allow candidates to use public money to fund their campaigns, which can open the door for more people to run for office. The goal of all of these proposals is to make politicians less beholden to wealthy interests and more receptive to their constituents.

Finally, a few localities may change their voting methods. Voters in Fargo, North Dakota will decide whether to adopt approval voting, where voters can “approve” of multiple candidates for a single office and the person with the most votes wins. Lane County, Oregon may adopt STAR (Score, Then Automatic Runoff) voting, where voters can assign a score of zero to five to each candidate, with the winner determined based on these scores. These voting methods give voters more choices and eliminate a system in which a candidate can win with only a plurality of the vote. Moving in the opposite direction, voters in Memphis will decide whether to repeal its prior approval of instant runoff voting (also known as ranked choice voting ), which would allow voters to rank-order the candidates. Voters had previously approved of the system, which is set to go into effect in 2019.

Amidst these positive voter expansions, there are also a few ballot measures this year that would make it harder to participate in our elections. Specifically, voters in Arkansas and North Carolina will decide whether to amend their state constitutions to allow strict voter ID requirements.

These numerous ballot propositions, with the exception of the Memphis push to repeal ranked choice voting and the Arkansas and North Carolina voter ID proposals, have a common theme: the voters themselves may adopt electoral reforms that will expand democratic participation and reduce the influence of incumbents. Any judicial review of these laws, if they pass, must take account of these aims.

This brief blog post does not provide ample space to offer a robust judicial test that courts should follow when considering the validity of voter-backed initiatives on democratic processes. But a few general outlines are appropriate.

First, the U.S. Supreme Court has already rejected a constitutional challenge to a voter-backed independent redistricting commission. Article I, Section 4 of the U.S. Constitution provides: “The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof….” After Arizona voters passed an initiative to create an independent redistricting commission, the Arizona legislature itself brought suit, claiming that the voters’ action took away the power from the “legislature” to dictate the “times, places and manner” of holding elections, as the U.S. Constitution directs. In Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission , a 2015 decision, the Court rejected the state legislature’s argument by a 5-4 vote. The Court, per Justice Ginsburg, held that the Arizona Constitution, in creating the referendum power, contemplated that the people themselves could essentially serve as the “legislature,” meaning that a voter-created independent redistricting commission was consistent with constitutional demands. Justice Kennedy was in the majority in that case, suggesting that the replacement of Justice Kennedy with Justice Kavanaugh could change the outcome. Yet this is one area in which Justice Kavanaugh should follow his promise to adhere to precedent, even if he disagrees with the majority’s opinion, especially as voters promoting these reforms in other states have now relied on the decision.

Second, courts should generally defer to voters who want to open up their democratic process to include more people. Regardless of the type of challenge involved (constitutional or otherwise), judges should adopt an interpretive lens that sanctions these pro-democracy reforms. Put another way, courts could invoke what is essentially a one-way “ democracy ratchet ” for election rules that promote greater participation in the electoral process. In doing so, judges should consider whether the voter-backed initiative has the purpose or effect of expanding opportunities for democratic participation, with the corollary impact of limiting the entrenchment of those in power. If the new rule is democracy-enhancing in this way, then the court should defer to the voters. Improving electoral participation through expanded voter registration opportunities, expanding the eligible electorate by easing felon disenfranchisement laws or lowering the voting age, and adopting public financing or limiting contributions all make it easier for more people to participate in our democracy. Courts should allow voters to decide to expand their state and local democracies in this fashion. The fact that the voters themselves passed these reforms suggests that they truly want to take their democracy back from entrenched interests and widen the scope of those who participate. By contrast, courts should turn a skeptical eye on laws that restrict democratic participation , such as a voter ID requirement that would make it harder for some people to vote. More careful scrutiny is required in this instance because a majority is using its majority status to cut off the ability of others (the minority) to participate in democracy.

To be sure, this proposed framework still presents difficult interpretative questions and more space would be needed to flesh out all of the benefits, disadvantages, and permutations of this approach. For instance, does a limit on the amount of a campaign contribution expand or restrict electoral participation? Although there are strong arguments on both sides, the whole point of a contribution limitation is to ensure that politicians are not beholden just to their wealthy donors; a contribution limit requires a candidate to seek smaller donations from more people. In this way, a contribution limit, while cutting off the electoral participation of a few at a certain level, will likely encourage participation from a greater number of people.

In sum, even amidst all of the news of voter suppression , there is still a lot to celebrate with respect to our democratic system, and hopefully after November 6 there will be even more: positive electoral reforms that change the way our democracy operates. Separate from and in addition to fighting voter suppression, we need to harness the potential of these positive reforms to reshape our democracy. Courts, when faced with a challenge to a law that expands democratic participation, should defer to the voters who enact these positive changes.

- Election Law

More from the Blog

The fourteenth amendment is not a bill of attainder.

Uncovering the Fundamental Contradictions in Chief Justice Chase’s Argument That Section Three Is Not Self-Executing

- Henry Ishitani

On Constructing a Stronger Right to Strike Through Comparative Labor Law

- David J. Doorey

- Harvard Law Review

Read our research on: TikTok | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

5. electoral reform and direct democracy.

Free and fair elections are a critical element of a healthy democratic system . And in many of the 24 countries surveyed, reforming how elections and the electoral system work is a key priority. People want both large-scale, systemic changes – such as switching from first-past-the-post to proportional representation – as well as smaller-scale issues like making Election Day a holiday.

Many people link these changes to greater citizen representation, whether it’s because they allow people to vote more easily or because their votes can be more readily and accurately converted into representation.

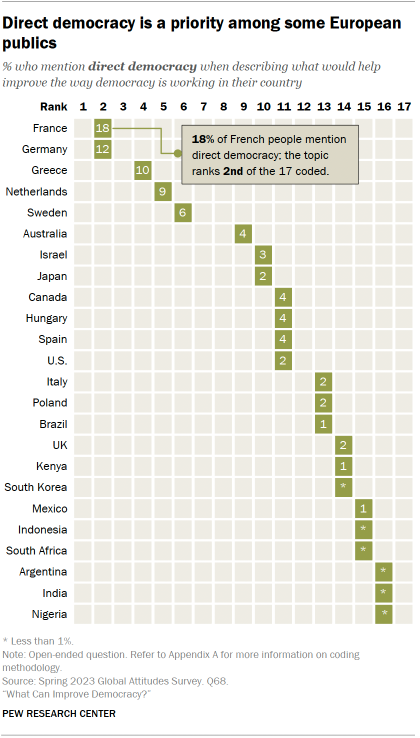

But some people take it even a step further, arguing for their country to have more direct democracy . Particularly in France and Germany, where direct democracy is the second-most suggested change, people want to have more chances to vote via referenda on topics that matter to them.

Electoral reform

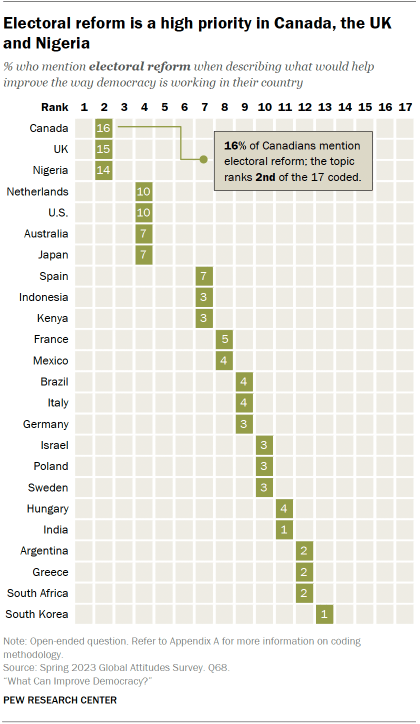

Changing the electoral system appears in the top five ranked issues in seven of the 24 countries surveyed. In Canada, Nigeria and the UK, the issue ranks second among the 17 substantive topics coded.

In six countries, those who do not support the governing party or parties are more likely to mention electoral reform than those who do support such parties. In the UK, for example, where electoral reform is ranked second only to politicians, 17% of those who do not support the ruling Conservative Party mention electoral reform, compared with 6% of Conservative Party supporters. (For more information on how we classify governing party supporters, refer to Appendix D .)

However, in the U.S. and Israel, this pattern is reversed: Those who do support the governing parties are more likely than those who do not to mention electoral reform as an improvement to democracy.

“People should have the right to choose their leaders through a free and fair election.” Woman, 20, Nigeria

Across the countries surveyed, people want to see a wide range of electoral reforms. Some of these focus on the logistics of casting votes – how and when people vote , and who is eligible . Others focus more on changing the electoral system , referencing issues like electoral thresholds and gerrymandering. And some emphasize the need to ensure free and fair elections . In Nigeria and Brazil, people who are not confident that their recent national elections were conducted fairly and accurately (as asked in a separate question in Brazil, Kenya and Nigeria) are more likely to bring up electoral reform.

Logistics of casting votes

Some of the calls for electoral reform center specifically on how ballots are cast. For example, some see benefits to electronic voting options over paper ballots, especially as a tool to protect elections: “Use modernized technology to help in security of the voting system,” said one Kenyan woman. Others see electronic ballots as an issue of convenience, particularly if it means one can vote from the comfort of their own house. As one Canadian man put it: “I think people should be able to vote electronically, using the internet and telephone instead of going to a polling station. It makes it more convenient.”

Still, in some places that have electronic voting, respondents raise concerns about this method. “End the electronic ballot box,” said a Brazilian woman. A man in India expressed his preference for paper ballots : “The use of electronic voting machines should be stopped and bring paper ballots back so that transparent democracy will be seen.”

For some Americans, increased access to absentee or mail-in voting is a specific electoral change they want to see: “Making vote-by-mail standard in every state, giving voters time to vote at their convenience, rather than having to miss work. It also gives them the time to research candidates at their leisure.” Others in the U.S. oppose mail-in voting : “Stop voter fraud! Go back to voting on Election Day. Enough with this all-month voting and mail-in votes,” wrote one American woman. “Stop mail-in ballots unless for military or another exempt person,” echoed a man. There are large partisan divides in U.S. views of voting methods , and more Democrats cast absentee votes than Republicans.

When people vote

People also see the need to change the frequency of elections . Some request fewer elections so that officeholders spend less of their term campaigning for reelection: One Australian man wanted to “lengthen the period between federal elections to five years.” Others want to see more elections, like a Canadian woman who said, “Do not have an election every four years; it should be every two years,” or a Nigerian woman who wanted her government to “conduct elections every two years, or frequently.” One South African woman went so far as to say, “Elections should be held every year.”

Some in the U.S. (where national elections are held on the first Tuesday after the first Monday of November) call for making Election Day a holiday . The U.S. is one of few advanced economies that does not hold elections over the weekend or designate the day a national holiday. For example, one American man said, “Create a national voting holiday to ensure every American has a chance to vote.” Another person said, “Eliminate voter suppression. Make Election Day a national holiday. Make voting as easy as mailing a letter.”

Who gets to vote

Making changes to who is allowed to participate in elections is another means people see to improve their democracy. For example, some want to alter the age at which citizens become eligible to cast their votes . For those who want to lower it, the argument centers around allowing more young people to participate in elections: “Lowering the voting age to 16, now young people have more stake in the game,” suggested a Canadian man. An American man had a similar opinion, saying, “I think lowering the age for voting would help democracy, because many teens as young as 16 already have views about policies in the U.S.”

Not all are in favor of lowering the voting age, however. As one Swedish man put it: “Raise the voting age. People at 18 need to take their electoral mandate more seriously.”

“There should be a voter’s license, and voters should take a civics test. Informed voting is the crux of democracy.” Man, 76, Italy

Others feel voters need to pass a knowledge test in order to cast a vote. “The right to vote should be bound by educational attainment,” said a man in Hungary. An Italian man said, “Those who want to vote should pass a test of general culture before the elections.” And a woman in Sweden was specific on this policy: “One should know what you’re voting for, a little mini test so you know what you’re voting for. A driver’s license to vote.” (For more on perceived citizen responsibility, read Chapter 4 .)

In some countries, though, there are calls to protect people’s existing right to vote . In the U.S., where voter suppression has become an electoral issue, several people were vocal about protecting the right to vote. “Abolish state laws that restrict voters’ rights,” suggested one American man. An Australian man focused specifically on protecting voting rights for Aboriginal people: “Ensure Indigenous voters have the opportunity to vote in all circumstances.” Certain respondents even want to enfranchise new types of voters: “Open the right to vote to all permanent residents, such as all Europeans who live in France,” said one French woman.

Mandatory voting

“To oblige every citizen to vote and influence according to law.” Man, 68, Israel

Respondents in some places went as far as suggesting that voting in elections and referenda be required as a means to improve democracy. One Greek woman said, “All citizens should be forced to vote on very important laws and decisions for the country.” A man in the Netherlands saw mandatory voting as a way to improve voter turnout: “Compulsory voting should be reintroduced. For provincial council elections, turnout is only 50% to 60%. Introducing compulsory voting could improve this.”

Still, not everyone who lives in a country that has mandatory voting approves of it. “Don’t make it compulsory to vote for someone. That way, the people who really care will have their vote and those who don’t care won’t just pick the first person on the sheet or the one with the best name with no idea who they are voting for,” said one Australian woman. Another Australian shared a similar view: “I would like to see the scrapping of compulsory voting, as this will mean political parties will need to work harder for votes.” And, in Argentina, where voting is mandatory for most citizens, some respondents called for its overhaul – “that voting is not compulsory.”

Changing the electoral system

“Election law reform. Stop voting by region and switch to a national election where one can choose the winner based on the highest number of votes nationwide.” Woman, 63, Japan

People also call for a different style of voting than they currently have. For example, some focus on implementing a first-past-the-post voting system (in which people vote for a single candidate and the candidate with the most votes wins). As one Australian man put it: “Introduce first-past-the-post voting , dispensing with preferential voting, as the minor parties are making every government difficult to operate.”

Other people value proportional representation , a system where politicians hold the number of seats proportional to their party’s support in the voting population. “Reintroduce the proportional representation voting system and ensure accountability by elected officials,” said a South African man. And a French woman said, “All representatives should be elected by proportional representation.”

Some expressed frustration with ballots listing a choice of parties instead of specific candidates , as in the case of a Swedish man who said, “Direct election of people, not parties. It is better to vote for a person, you know what they think.” An Australian agreed: “Enhancing the electoral process for Australians to vote for candidates, and less for their parties.”

There are also calls for things like ranked-choice voting (“Ranked-choice voting would limit extremism.”) and two-round voting (“The kind of two-round voting system would improve democracy.”).

But no one system necessarily satisfies everyone. In some countries that already have first-past-the-post voting, for example, there are requests to eliminate it: “Get rid of first-past-the-post. The electoral system needs reform so that the representation by popular votes should have some weight,” said one man in Canada. One Japanese woman said, “Abolish the single-seat constituency system ,” referring to a type of voting that includes first-past-the-post, where one winner represents one electoral district.

Electoral threshold

“The electoral threshold should be raised, there should be fewer and larger parties.” Man, 82, Netherlands

Changes to the electoral threshold , or the minimum share of votes needed for a candidate or party to provide representation, is suggested by some as a way to improve democracy – particularly among those who live in countries with low thresholds and fragmented party systems. In Israel, where the 3.25% electoral threshold leads to many parties participating in each election, one woman said, “Significantly increase the electoral threshold.”

This sentiment is echoed in the Netherlands, where the 0.67% threshold is the lowest in the world . One Dutch man said, “I think a high electoral threshold would be good. This could lead to less fragmentation and speed up decision-making.” Another Dutch man saw this change as a means to improve the overall quality of elections: “Raise the electoral threshold, so that there will be more substance. That way not everyone can just start a party.” The Dutch survey was conducted prior to November 2023 elections , in which the far-right Party for Freedom (PVV) won the most seats in the House of Representatives.

Making all votes count – or count more

Revising the borders of electoral districts is a reform some think could help increase voter representation. Gerrymandering , for example – a term coined in the U.S. to describe the practice of drawing electoral district boundaries in a way that creates an advantage for one party over another – is something that people in multiple countries flagged as a problem. For example, an Australian man said, “If we were to ban gerrymandering then each political group would have an equal chance to be elected.” In the U.S., one man said, “It would help if we got rid of gerrymandering and the Electoral College and things that suppress the majority.”

For others, voter representation is not just about physical electoral districts, but about correcting a perceived imbalance in the value of each vote . A 38-year-old Japanese man suggested “equalizing the value of votes from young people versus those of the elderly. Young people should be entitled to two votes.” This issue was also brought up in Spain: “The best thing would be one person, one vote. That is, that all votes were worth the same, that they were not counted by autonomous communities,” said one man.

The U.S. Electoral College

The Electoral College – the process by which U.S. presidential elections are decided – is a major focus of electoral reform for many Americans. One man’s response summarized this stance: “Abolition of the Electoral College to allow for direct representation of individual voters rather than allowing certain states to be overrepresented compared to their population size.”

Most of the U.S. respondents who mention the Electoral College are against the process, like one woman who said, “We need to do away with the Electoral College. It was a good idea, but now it doesn’t make sense.” For many, it’s an issue of unequal representation: “The Electoral College should go away, and potentially change how senators are allotted. Sparsely populated areas have too much influence while tens of millions of city residents essentially have no say,” said another woman.

Free and fair elections

“Have transparent voting and respect who wins. And the one who loses should help the one who won and move on.” Man, 38, Argentina

People also call for more election integrity . For example, some feel there should be more transparency: “More openness in general election, no corruption, collusion or nepotism,” said a woman in Indonesia. Or, as a Nigerian man put it: “Let us have a free and fair election with transparency.” People are concerned about this issue in advanced economies as well, with one Canadian man saying, “Election integrity needs to be improved, and no outside interference.”

Others emphasize the importance of respecting election results . “Accept when a candidate loses the election and when a candidate is elected,” said a man in Brazil. An Israeli man put it simply: “Respect the results of the elections.”

“Monitor the processes more, so that there is no miscount.” Woman, 23, Mexico

Improving electoral monitoring , or the use of unbiased observers to ensure that elections are free and fair , is also a key change people want: “Supervision over the counting of votes,” as a woman in Israel said.

In Mexico, where President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has sought controversial election reforms that many believe will weaken the country’s National Electoral Institute (INE), there are specific calls to “strengthen the INE instead of wanting to destroy it,” as one man said.

A Nigerian man expressed his wish for a better institutional oversight, saying, “The electoral commission should be independent and free from interference from the ruling party.” Nigeria’s electoral commission faced criticism during the February 2023 presidential election and was accused of delaying election results .

Direct democracy

“Consult the French people more often through referendums about important issues, life-changing issues.” Woman, 49, France

For some, a form of government where the public votes directly on proposed legislation or policies is a solution to fixing democracy.

This sentiment is particularly common in European countries: In France, Germany, Greece and the Netherlands, it appears in the top five topics mentioned.

In most other countries, it is less of a priority.

In a handful of countries (Australia, Canada, France, Greece, the Netherlands and the UK), those who do not support the governing party or coalition are more likely to mention direct democracy.

French people stand out as particularly likely to mention direct democracy

In France, direct democracy is the second-most mentioned change people want to see. French people on the ideological left are more likely to bring up this topic than those on the right. Additionally, French adults who believe most elected officials don’t care what people like them think ( as asked in a separate question ) are twice as likely to mention direct democracy as those who say most officials care what they think.

Some in France specifically reference Article 49.3 of the French Constitution , under which the government can push legislation through the National Assembly with no legislative vote: “Article 49.3, which had been established for certain situations, is being used to force through unpopular measures,” said one man. The survey was fielded in France between February and April, a period during which Article 49.3 was used to implement controversial pension reforms . Another French man criticizing Article 49.3 saw direct democracy as a clear solution, saying, “Take into account the opinion of citizens in the form of a referendum. Ask for the citizens’ opinions to avoid passing laws in the form of 49.3.”

The Swiss model

Switzerland’s political system – in which the public is able to vote directly on constitutional initiatives and policy referenda – is perceived positively by others around the world, many of whom want their own country to emulate this model. For example, one Canadian woman said, “If people could vote on important issues like in Switzerland and make decisions on important laws, that’s a true democracy there.”

“More public participation on single important topics, just like the referendums in Switzerland.” Man, 55, Germany

This viewpoint is particularly widespread across European respondents; many want their country’s democracy to resemble Switzerland’s. “It would be a good idea to go back and make decisions much more collegially, like the Swiss system,” said a French man. And a Swedish woman said, “More referenda on nuclear power, sexuality, NATO and the EU. Like Switzerland, which has referendums on many issues.” (The survey was conducted prior to Sweden joining NATO in March 2024.)

Respondents in many countries highlight the benefits of more referenda , or instances where the public votes directly on an issue. For some, a key factor is the frequency of voting . One Kenyan man responded, “Citizens should have a referendum at least once in a while to decide on major issues that affect the country.” And a German woman asked that “more referendums take place.”

“More citizen participation in real decision-making. In other countries, referendums are held expressing opinions on different issues, not like here where they vote every four years.” Man, 41, Spain

In other cases, referenda are seen as opportunities for the government to seek the public’s approval . A Mexican man explained, “Before becoming legal, reforms should pass through a citizen filter and popular consultation.” This sometimes includes ensuring that more marginalized voices get a chance to weigh in. For example, one Israeli man said, “When enacting any law, there should be a referendum where all citizens vote, whether Arabs or Jews.” And an Australian woman wished to see more perspectives reflected, calling for “more direct democracy, and more opportunities for influence by poor, multicultural and minority groups.”

In the UK, where a controversial June 2016 referendum resulted in the UK departing the European Union (known as Brexit), some still express support for direct democracy. A British woman suggested, “We need to put down more questions more polls for the public to choose new policies, new laws.” One British man even noted that a referendum could undo Brexit: “We should have a referendum that is truly reflective about Brexit and rejoining the EU.” But other Britons are more wary of direct democracy: One man said, “We should not allow the general public to make critical decisions. The general public should not be allowed to make economic decisions, for example, Brexit.”

Facts are more important than ever

In times of uncertainty, good decisions demand good data. Please support our research with a financial contribution.

Report Materials

Table of contents, freedom, elections, voice: how people in australia and the uk define democracy, global public opinion in an era of democratic anxiety, most people in advanced economies think their own government respects personal freedoms, more people globally see racial, ethnic discrimination as a serious problem in the u.s. than in their own society, citizens in advanced economies want significant changes to their political systems, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Chapter 1: American Government and Civic Engagement

Engagement in a Democracy

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the importance of citizen engagement in a democracy

- Describe the main ways Americans can influence and become engaged in government

- Discuss factors that may affect people’s willingness to become engaged in government

Participation in government matters. Although people may not get all that they want, they can achieve many goals and improve their lives through civic engagement. According to the pluralist theory, government cannot function without active participation by at least some citizens. Even if we believe the elite make political decisions, participation in government through the act of voting can change who the members of the elite are.

WHY GET INVOLVED?

Are fewer people today active in politics than in the past? Political scientist Robert Putnam has argued that civic engagement is declining; although many Americans may report belonging to groups, these groups are usually large, impersonal ones with thousands of members. People who join groups such as Amnesty International or Greenpeace may share certain values and ideals with other members of the group, but they do not actually interact with these other members. These organizations are different from the types of groups Americans used to belong to, like church groups or bowling leagues. Although people are still interested in volunteering and working for the public good, they are more interested in either working individually or joining large organizations where they have little opportunity to interact with others. Putnam considers a number of explanations for this decline in small group membership, including increased participation by women in the workforce, a decrease in the number of marriages and an increase in divorces, and the effect of technological developments, such as the internet, that separate people by allowing them to feel connected to others without having to spend time in their presence. [1]

Putnam argues that a decline in social capital —”the collective value of all ‘social networks’ [those whom people know] and the inclinations that arise from these networks to do things for each other”—accompanies this decline in membership in small, interactive groups. [2] Included in social capital are such things as networks of individuals, a sense that one is part of an entity larger than oneself, concern for the collective good and a willingness to help others, and the ability to trust others and to work with them to find solutions to problems. This, in turn, has hurt people’s willingness and ability to engage in representative government. If Putnam is correct, this trend is unfortunate, because becoming active in government and community organizations is important for many reasons.

Some have countered Putnam’s thesis and argue that participation is in better shape than what he portrays. Everett Ladd shows many positive trends in social involvement in American communities that serve to soften some of the declines identified by Putnam. For example, while bowling league participation is down, soccer league participation has proliferated. [3] April Clark examines and analyzes a wide variety of social capital data trends and disputes the original thesis of erosion. [4] Others have suggested that technology has increased connectedness, an idea that Putnam himself has critiqued as not as deep as in-person connections. [5]

LINK TO LEARNING

To learn more about political engagement in the United States, read “The Current State of Civic Engagement in America” by the Pew Research Center.

Civic engagement can increase the power of ordinary people to influence government actions. Even those without money or connections to important people can influence the policies that affect their lives and change the direction taken by government. U.S. history is filled with examples of people actively challenging the power of elites, gaining rights for themselves, and protecting their interests. For example, slavery was once legal in the United States and large sectors of the U.S. economy were dependent on this forced labor. Slavery was outlawed and blacks were granted citizenship because of the actions of abolitionists. Although some abolitionists were wealthy white men, most were ordinary people, including men and women of both races. White women and blacks were able to actively assist in the campaign to end slavery despite the fact that, with few exceptions, they were unable to vote. Similarly, the right to vote once belonged solely to white men until the Fifteenth Amendment gave the vote to African American men. The Nineteenth Amendment extended the vote to include women, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 made exercising the right to vote a reality for African American men and women in the South. None of this would have happened, however, without the efforts of people who marched in protest, participated in boycotts, delivered speeches, wrote letters to politicians, and sometimes risked arrest in order to be heard. The tactics used to influence the government and effect change by abolitionists and members of the women’s rights and African American civil rights movements are still used by many activists today.

The rights gained by these activists and others have dramatically improved the quality of life for many in the United States. Civil rights legislation did not focus solely on the right to vote or to hold public office; it also integrated schools and public accommodations, prohibited discrimination in housing and employment, and increased access to higher education. Activists for women’s rights fought for, and won, greater reproductive freedom for women, better wages, and access to credit. Only a few decades ago, homosexuality was considered a mental disorder, and intercourse between consenting adults of the same sex was illegal in many states. Although legal discrimination against gays and lesbians still remains, consensual intercourse between homosexual adults is no longer illegal anywhere in the United States, and same-sex couples have the right to legally marry.

Activism can improve people’s lives in less dramatic ways as well. Working to make cities clean up vacant lots, destroy or rehabilitate abandoned buildings, build more parks and playgrounds, pass ordinances requiring people to curb their dogs, and ban late-night noise greatly affects people’s quality of life. The actions of individual Americans can make their own lives better and improve their neighbors’ lives as well.

Representative democracy cannot work effectively without the participation of informed citizens, however. Engaged citizens familiarize themselves with the most important issues confronting the country and with the plans different candidates have for dealing with those issues. Then they vote for the candidates they believe will be best suited to the job, and they may join others to raise funds or campaign for those they support. They inform their representatives how they feel about important issues. Through these efforts and others, engaged citizens let their representatives know what they want and thus influence policy. Only then can government actions accurately reflect the interests and concerns of the majority. Even people who believe the elite rule government should recognize that it is easier for them to do so if ordinary people make no effort to participate in public life.

PATHWAYS TO ENGAGEMENT

People can become civically engaged in many ways, either as individuals or as members of groups. Some forms of individual engagement require very little effort. One of the simplest ways is to stay informed about debates and events in the community, in the state, and in the nation. Awareness is the first step toward engagement. News is available from a variety of reputable sources, such as newspapers like the New York Times ; national news shows, including those offered by the Public Broadcasting Service and National Public Radio; and reputable internet sites.

Visit Avaaz and Change.org for more information on current political issues.

Another form of individual engagement is to write or email political representatives. Filing a complaint with the city council is another avenue of engagement. City officials cannot fix problems if they do not know anything is wrong to begin with. Responding to public opinion polls, actively contributing to a political blog, or starting a new blog are all examples of different ways to be involved.

One of the most basic ways to engage with government as an individual is to vote. Individual votes do matter. City council members, mayors, state legislators, governors, and members of Congress are all chosen by popular vote. Although the president of the United States is not chosen directly by popular vote but by a group called the Electoral College, the votes of individuals in their home states determine how the Electoral College ultimately votes. Registering to vote beforehand is necessary in most states, but it is usually a simple process, and many states allow registration online. (We discuss voter registration and voter turnout in more depth in a later chapter.)

Voting, however, is not the only form of political engagement in which people may participate. Individuals can engage by attending political rallies, donating money to campaigns, and signing petitions. Starting a petition of one’s own is relatively easy, and some websites that encourage people to become involved in political activism provide petitions that can be circulated through email. Taking part in a poll or survey is another simple way to make your voice heard.

Votes for Eighteen-Year-Olds

Young Americans are often reluctant to become involved in traditional forms of political activity. They may believe politicians are not interested in what they have to say, or they may feel their votes do not matter. However, this attitude has not always prevailed. Indeed, today’s college students can vote because of the activism of college students in the 1960s. Most states at that time required citizens to be twenty-one years of age before they could vote in national elections. This angered many young people, especially young men who could be drafted to fight the war in Vietnam. They argued that it was unfair to deny eighteen-year-olds the right to vote for the people who had the power to send them to war. As a result, the <strong”>Twenty-Sixth Amendment, which lowered the voting age in national elections to eighteen, was ratified by the states and went into effect in 1971.

Are you engaged in or at least informed about actions of the federal or local government? Are you registered to vote? How would you feel if you were not allowed to vote until age twenty-one?

Some people prefer to work with groups when participating in political activities or performing service to the community. Group activities can be as simple as hosting a book club or discussion group to talk about politics. Coffee Party USA provides an online forum for people from a variety of political perspectives to discuss issues that are of concern to them. People who wish to be more active often work for political campaigns. Engaging in fundraising efforts, handing out bumper stickers and campaign buttons, helping people register to vote, and driving voters to the polls on Election Day are all important activities that anyone can engage in. Individual citizens can also join interest groups that promote the causes they favor.

GET CONNECTED!

Getting Involved

In many ways, the pluralists were right. There is plenty of room for average citizens to become active in government, whether it is through a city council subcommittee or another type of local organization. Civic organizations always need volunteers, sometimes for only a short while and sometimes for much longer.

For example, Common Cause is a non-partisan organization that seeks to hold government accountable for its actions. It calls for campaign finance reform and paper verification of votes registered on electronic voting machines. Voters would then receive proof that the machine recorded their actual vote. This would help to detect faulty machines that were inaccurately tabulating votes or election fraud. Therefore, one could be sure that election results were reliable and that the winning candidate had in fact received the votes counted in their favor. Common Cause has also advocated that the Electoral College be done away with and that presidential elections be decided solely on the basis of the popular vote.

Follow-up activity: Choose one of the following websites to connect with organizations and interest groups in need of help:

- Common Cause ;

- Friends of the Earth which mobilizes people to protect the natural environment;

- Grassroots International which works for global justice;

- The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget which seeks to inform the public on issues with fiscal impact and favors smaller budget deficits; or

- Eagle Forum which supports greater restrictions on immigration and fewer restrictions on home schooling.

Political activity is not the only form of engagement, and many people today seek other opportunities to become involved. This is particularly true of young Americans. Although young people today often shy away from participating in traditional political activities, they do express deep concern for their communities and seek out volunteer opportunities. [6]

Although they may not realize it, becoming active in the community and engaging in a wide variety of community-based volunteer efforts are important forms of civic engagement and help government do its job. The demands on government are great, and funds do not always exist to enable it to undertake all the projects it may deem necessary. Even when there are sufficient funds, politicians have differing ideas regarding how much government should do and what areas it should be active in. Volunteers and community organizations help fill the gaps. Examples of community action include tending a community garden, building a house for Habitat for Humanity, cleaning up trash in a vacant lot, volunteering to deliver meals to the elderly, and tutoring children in after-school programs.

Some people prefer even more active and direct forms of engagement such as protest marches and demonstrations, including civil disobedience. Such tactics were used successfully in the African American civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s and remain effective today. Likewise, the sit-ins (and sleep-ins and pray-ins) staged by African American civil rights activists, which they employed successfully to desegregate lunch counters, motels, and churches, have been adopted today by movements such as Black Lives Matter and Occupy Wall Street. Other tactics, such as boycotting businesses of whose policies the activists disapproved, are also still common. Along with boycotts, there are now “buycotts,” in which consumers purchase goods and services from companies that give extensively to charity, help the communities in which they are located, or take steps to protect the environment.

Many ordinary people have become political activists. Read “19 Young Activists Changing America” to learn about people who are working to make people’s lives better.

INSIDER PERSPECTIVE

Ritchie Torres

In 2013, at the age of twenty-five, Ritchie Torres became the youngest member of the New York City Council and the first gay council member to represent the Bronx. Torres became interested in social justice early in his life. He was raised in poverty in the Bronx by his mother and a stepfather who left the family when Torres was twelve. The mold in his family’s public housing apartment caused him to suffer from asthma as a child, and he spent time in the hospital on more than one occasion because of it. His mother’s complaints to the New York City Housing Authority were largely ignored. In high school, Torres decided to become a lawyer, participated in mock trials, and met a young and aspiring local politician named James Vacca. After graduation, he volunteered to campaign for Vacca in his run for a seat on the City Council. After Vacca was elected, he hired Torres to serve as his housing director to reach out to the community on Vacca’s behalf. While doing so, Torres took pictures of the poor conditions in public housing and collected complaints from residents. In 2013, Torres ran for a seat on the City Council himself and won. He remains committed to improving housing for the poor. [7]

Why don’t more young people run for local office as Torres did? What changes might they effect in their communities if they were elected to a government position?

FACTORS OF ENGAGEMENT