Feminist Theory

Jo Ann Arinder

Feminist theory falls under the umbrella of critical theory, which in general have the purpose of destabilizing systems of power and oppression. Feminist theory will be discussed here as a theory with a lower case ‘t’, however this is not meant to imply that it is not a Theory or cannot be used as one, only to acknowledge that for some it may be a sub-genre of Critical Theory, while for others it stands alone. According to Egbert and Sanden (2020), some scholars see critical paradigms as extensions of the interpretivist, but there is also an emphasis on oppression and lived experience grounded in subjectivist epistemology.

The purpose of using a feminist lens is to enable the discovery of how people interact within systems and possibly offer solutions to confront and eradicate oppressive systems and structures. Feminist theory considers the lived experience of any person/people, not just women, with an emphasis on oppression. While there may not be a consensus on where feminist theory fits as a theory or paradigm, disruption of oppression is a core tenant of feminist work. As hooks (2000) states, “Simply put, feminism is a movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation and oppression. I liked this definition because it does not imply that men were the enemy” (p. viii).

Previous Studies

Marxism and socialism are key components in the heritage.of feminist theory. The origins of feminist theory can be found in the 18th century with growth in the 1970s’ and 1980s’ equality movements. According to Burton (2014), feminist theory has its roots in Marxism but specifically looks to Engles’ (1884) work as one possible starting point. Burton (2014) notes that, “Origin of the Family and commentaries on it were central texts to the feminist movement in its early years because of the felt need to understand the origins and subsequent development of the subordination of the female sex” (p. 2). Work in feminist theory, including research regarding gender equality, is ongoing.

Gender equality continues to be an issue today, and research into gender equality in education is still moving feminist theory forward. For example, Pincock’s (2017) study discusses the impact of repressive norms on the education of girls in Tanzania. The author states that, “…considerations of what empowerment looks like in relation to one’s sexuality are particularly important in relation to schooling for teenage girls as a route to expanding their agency” (p. 909). This consideration can be extended to any oppressed group within an educational setting and is not an area of inquiry relegated to the oppression of only female students. For example, non-binary students face oppression within educational systems and even male students can face barriers, and students are often still led towards what are considered “gender appropriate” studies. This creates a system of oppression that requires active work to disrupt.

Looking at representation in the literature used in education is another area of inquiry in feminist research. For example, Earles (2017) focused on physical educational settings to explore relationships “between gendered literary characters and stories and the normative and marginal responses produced by children” (p. 369). In this research, Earles found evidence to support that a contradiction between the literature and children’s lived experiences exists. The author suggests that educators can help to continue the reduction of oppressive gender norms through careful selection of literature and spaces to allow learners opportunities for appropriate discussions about these inconsistencies.

In another study, Mackie (1999) explored incorporating feminist theory into evaluation research. Mackie was evaluating curriculum created for English language learners that recognized the dual realities of some students, also known as the intersectionality of identity, and concluded that this recognition empowered students. Mackie noted that valuing experience and identity created a potential for change on an individual and community level and “Feminist and other types of critical teaching and research provide needed balance to TESL and applied linguistics” (p. 571).Further, Bierema and Cseh (2003) used a feminist research framework to examine previously ignored structural inequalities that affect the lives of women working in the field of human resources.

Model of Feminist Theory

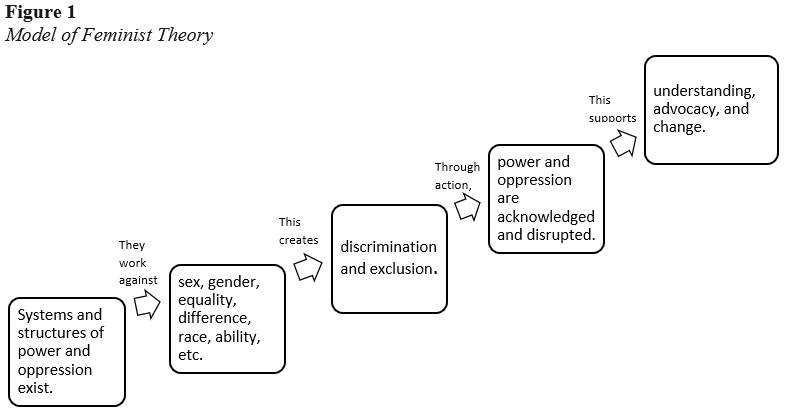

Figure 1 presents a model of feminist theory that begins with the belief that systems exist that oppress and work against individuals. The model then shows that oppression is based on intersecting identities that can create discrimination and exclusion. The model indicates the idea that, through knowledge and action, oppressive systems can be disrupted to support change and understanding.

The core concepts in feminist theory are sex, gender, race, discrimination, equality, difference, and choice. There are systems and structures in place that work against individuals based on these qualities and against equality and equity. Research in critical paradigms requires the belief that, through the exploration of these existing conditions in the current social order, truths can be revealed. More important, however, this exploration can simultaneously build awareness of oppressive systems and create spaces for diverse voices to speak for themselves (Egbert & Sanden, 2019).

Constructs

Feminism is concerned with the constructs of intersectionality, dimensions of social life, social inequality, and social transformation. Through feminist research, lasting contributions have been made to understanding the complexities and changes in the gendered division of labor. Men and women should be politically, economically, and socially equal and this theory does not subscribe to differences or similarities between men, nor does it refer to excluding men or only furthering women’s causes. Feminist theory works to support change and understanding through acknowledging and disrupting power and oppression.

Proposition

Feminist theory proposes that when power and oppression are acknowledged and disrupted, understanding, advocacy, and change can occur.

Using the Model

There are many potential ways to utilize this model in research and practice. First, teachers and students can consider what systems of power exist in their classroom, school, or district. They can question how these systems are working to create discrimination and exclusion. By considering existing social structures, they can acknowledge barriers and issues inherit to the system. Once these issues are acknowledged, they can be disrupted so that change and understanding can begin. This may manifest, for example, as considering how past colonialism has oppressed learners of English as a second or foreign language.

The use of feminist theory in the classroom can ensure that the classroom is created, in advance, to consider barriers to learning faced by learners due to sex, gender, difference, race, or ability. This can help to reduce oppression created by systemic issues. In the case of the English language classroom, learners may be facing oppression based on their native language or country of origin. Facing these barriers in and out of the classroom can affect learners’ access to education. Considering these barriers in planning and including efforts to mitigate the issues and barriers faced by learners is a use of feminist theory.

Feminist research is interested in disrupting systems of oppression or barriers created from these systems with a goal of creating change. All research can include feminist theory when the research adds to efforts to work against and advocate to eliminate the power and oppression that exists within systems or structures that, in particular, oppress women. An examination of education in general could be useful since education is a field typically dominated by women; however, women are not often in leadership roles in the field. In the same way, using feminist theory for an examination into the lack of people of color and male teachers represented in education might also be useful. Action research is another area that can use feminist theory. Action research is often conducted in the pursuit of establishing changes that are discovered during a project. Feminism and action research are both concerned with creating change, which makes them a natural pairing.

Pre-existing beliefs about what feminism means can make including it in classroom practice or research challenging. Understanding that feminism is about reducing oppression for everyone and sharing that definition can reduce this challenge. hooks (2000) said that, “A male who has divested of male privilege, who has embraced feminist politics, is a worthy comrade in struggle, in no way a threat to feminism, whereas a female who remains wedded to sexist thinking and behavior infiltrating feminist movement is a dangerous threat”(p. 12). As Angela Davis noted during a speech at Western Washington University in 2017, “Everything is a feminist issue.” Feminist theory is about questioning existing structures and whether they are creating barriers for anyone. An interest in the reduction of barriers is feminist. Anyone can believe in the need to eliminate oppression and work as teachers or researchers to actively to disrupt systems of oppression.

Bierema, L. L., & Cseh, M. (2003). Evaluating AHRD research using a feminist research framework. Human Resource Development Quarterly , 14 (1), 5–26.

Burton, C. (2014). Subordination: Feminism and social theory . Routledge.

Earles, J. (2017). Reading gender: A feminist, queer approach to children’s literature and children’s discursive agency. Gender and Education, 29 (3), 369–388.

Egbert, J., & Sanden, S. (2019). Foundations of education research: Understanding theoretical components . Taylor & Francis.

Hooks, B. (2000). Feminism is for everybody: Passionate politics . South End Press.

Mackie, A. (1999). Possibilities for feminism in ESL education and research. TESOL Quarterly, 33 (3), 566-573.

Pincock, K. (2018). School, sexuality and problematic girlhoods: Reframing ‘empowerment’ discourse. Third World Quarterly, 39 (5), 906-919.

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 26, Issue 3

- Research made simple: an introduction to feminist research

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Gillian Wilson

- School of Nursing and Midwifery , University of Hull , Hull , UK

- Correspondence to Gillian Wilson, University of Hull, Hull, Kingston upon Hull, UK; gillian.wilson{at}hull.ac.uk

https://doi.org/10.1136/ebnurs-2023-103749

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Writing an article for ‘Research Made Simple’ on feminist research may at first appear slightly oxymoronic, given that there is no agreed definition of feminist research, let alone a single definition of feminism. The literature that examines the historical and philosophical roots of feminism(s) and feminist research is vast, extends over several decades and reaches across an expanse of varying disciplines. Trying to navigate the literature can be daunting and may, at first, appear impenetrable to those new to feminist research.

There is no ‘How To’ in feminist research. Although feminists tend to share the same common goals, their interests, values and perspectives can be quite disparate. Depending on the philosophical position they hold, feminist researchers will draw on differing epistemologies (ways of knowing), ask different questions, be guided by different methodologies and employ different methods. Within the confines of space, this article will briefly outline some of the principles of feminist research. It will then turn to discuss three established epistemologies that can guide feminist research (although there are many others): feminist empiricism, feminist standpoint and feminist postmodernism.

What makes feminist research feminist?

Feminist research is grounded in a commitment to equality and social justice, and is cognisant of the gendered, historical and political processes involved in the production of knowledge. 1 It also strives to explore and illuminate the diversity of the experiences of women and other marginalised groups, thereby creating opportunities that increase awareness of how social hierarchies impact on and influence oppression. 2 Commenting on the differentiation between feminist and non-feminist research, Skeggs asserts that ‘feminist research begins from the premise that the nature of reality in western society is unequal and hierarchical’ Skeggs 3 p77; therefore, feminist research may also be viewed as having both academic and political concerns.

Reflexivity

The practice of reflexivity is considered a hallmark of feminist research. It invites the researcher to engage in a ‘disciplined self-reflection’ Wilkinson 9 p93. This includes consideration of the extent to which their research fulfils feminist principles. Reflexivity can be divided into three discrete forms: personal, functional and disciplinary. 9 Personal reflexivity invites the researcher to contemplate their role in the research and construction of knowledge by examining the ways in which their own values, beliefs, interests, emotions, biography and social location, have influenced the research process and the outcomes (personal reflexivity). 10 By stating their position rather than concealing it, feminist researchers use reflexivity to add context to their claims. Functional reflexivity pays attention to the influence that the chosen research tools and processes may have had on the research. Disciplinary reflexivity is about analysing the influence of approaching a topic from a specific disciplinary field.

Feminist empiricism

Feminist empiricism is underpinned by foundationalist principles that believes in a single true social reality with truth existing entirely independent of the knower (researcher). 8 Building on the premise that feminist researchers pay attention to how methods are used, feminist empiricist researchers set out to use androcentric positivist scientific methods ‘more appropriately’. 8 They argue that feminist principles can legitimately be applied to empirical inquiry if the masculine bias inherent in scientific research is removed. This is achieved through application of rigorous, objective, value-free scientific methods. Methods used include experimental, quasi-experimental and survey. Feminist empiricists employ traditional positivist methodology while being cognisant of the sex and gender biases. What makes the research endeavour feminist is the attentiveness in identifying potential sources of gendered bias. 11

Feminist standpoint

In a similar way to feminist empiricism, standpoint feminism—also known as ‘women’s experience epistemology’ Letherby 8 p44—holds firm the position that traditional science is androcentric and is therefore bad science. This is predicated on the belief that traditional science only produces masculine forms of knowledge thus excluding women’s perspectives and experiences. Feminist standpoint epistemology takes issue with the masculinised definition of women’s experience and argue it holds little relevance for women. Feminist standpoint epistemology therefore operates on the assumption that knowledge emanates from social position and foregrounds the voices of women and their experiences of oppression to generate knowledge about their lives that would otherwise have remained hidden. 12 Feminist standpoint epistemology maintains that women, as the oppressed or disadvantaged, may have an epistemological advantage over the dominant groups by virtue of their ability to understand their own experience and struggles against oppression, while also by being attuned to the experience and culture of their oppressors. 11 This gives women’s experience a valid basis for knowledge production that both reflects women’s oppression and resistance. 13

Feminist standpoint epistemology works on the premise that there is no single reality, 11 thus disrupting the empiricist notion that research must be objective and value-free. 12 To shed light on the experiences of the oppressed, feminist standpoint researchers use both quantitative and qualitative approaches to see the world through the eyes of their research participants and understand how their positions shape their experiences within the social world. In addition, the researchers are expected to engage in strong reflexivity and reflect on, and acknowledge in their writing, how their own attributes and social location may impact on interpretation of their data. 14

Feminist postmodernism

Feminist postmodernism is a branch of feminism that embraces feminist and postmodernist thought. Feminist postmodernists reject the notion of an objective truth and a single reality. They maintain that truths are relative, multiple, and dependent on social contexts. 15 The theory is marked by the rejection of the feminist ideology that seeks a single explanation for oppression of women. Feminist postmodernists argue that women experience oppression because of social and political marginalisation rather than their biological difference to men, concluding that gender is a social construct. 16

Feminist postmodernists eschew phallogocentric masculine thought (expressed through words and language) that leads to by binary opposition. They are particularly concerned with the man/woman dyad, but also other binary oppositions of race, gender and class. 17 Feminist postmodernist scholars believe that knowledge is constructed by language and that language gives meaning to everything—it does not portray reality, rather it constructs it. 11 A key feature of feminist postmodernist research is the attempt to deconstruct the binary opposition through reflecting on existing assumptions, questioning how ways of thinking have been socially constructed and challenging the taken-for-granted. 17

This article has provided a brief overview of feminist research. It should be considered more of a taster that introduces readers to the complex but fascinating world of feminist research. Readers who have developed an appetite for a more comprehensive examination are guided to a useful and accessible text on feminist theories and concepts in healthcare written by Kay Aranda. 1

- Western D ,

- Giacomini M

- Margaret Fonow M ,

- Wilkinson S

- Campbell R ,

- Wigginton B ,

- Lafrance MN

- Naples NA ,

- Hesse-Biber S

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Handbook of Feminist Research Theory and Praxis

- Sharlene Nagy Hesse-Biber - Boston College, USA

- Description

This Handbook presents both a theoretical and practical approach to conducting social science research on, for, and about women. It develops an understanding of feminist research by introducing a range of feminist epistemologies, methodologies, and emergent methods that have had a significant impact on feminist research practice and women's studies scholarship. Contributors to the Second Edition continue to highlight the close link between feminist research and social change and transformation.

The new edition expands the base of scholarship into new areas, with 12 entirely new chapters on topics such as the natural sciences, social work, the health sciences, and environmental studies. It extends discussion of the intersections of race, class, gender, and globalization, as well as transgender, transsexualism and the queering of gender identities. All 22 chapters retained from the first edition are updated with the most current scholarship, including a focus on the role that new technologies play in the feminist research process.

Discover the latest news from Author Sharlene Nagy Hesse-Biber: Visit http://www.fordham.edu/Campus_Resources/eNewsroom/topstories_2397.asp

| ISBN: 9781412980593 | Hardcover | Suggested Retail Price: $195.00 | Bookstore Price: $156.00 |

| ISBN: 9781483341453 | Electronic Version | Suggested Retail Price: $156.00 | Bookstore Price: $124.80 |

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

'The Handbook of Feminist Research: Theory and Praxis is a well-developed contribution to the body of feminist literature. It effectively highlights the connection between feminist research and social change by drawing upon the range of existent feminist epistemologies, methods, and practices, all of which adopt different means of conceptualising, researching, and ultimately representing the lived experiences of women, varied across the lines of race, class and/or other demographics. The text, while accessible for both research and teaching purposes, perhaps most importantly draws our attention to the need to be critically aware in the process of conducting feminist research. One must address the challenges, research developments, and, crucially, the diversity amongst women, that may be incurred in attempting to research, understand, and accurately represent the lived experiences of all women'

Key Features of the Second Edition

- Expands the base of scholarship into new areas , with new chapters on the place of feminism in the natural sciences, social work, the health sciences, and environmental studies

- Extends discussion of the intersections of race, class, gender, and globalization , with new chapter on issues of gender identity

- Updates all chapters retained from the first edition with the most current scholarship , including a focus on the role that new technologies play in the feminist research process

- Includes research case studies in each chapter , providing readers with step-by-step praxis examples for conducting their own research projects

- Offers new research and teaching resources, including discussion questions, and a list of websites as well as journal references geared to each chapter's content

We continue to reach out to two primary constituencies. The first is researchers, practitioners, and students within, and outside the academy, who conduct a variety of research projects and who are interested in consulting "cutting edge" research methods and gaining insights into the overall research process. This group also includes policymakers and activists who are interested in how to conduct research for social change. The second edition's audience continues to include academic researchers who, it is hoped, will use the Handbook in their research scholarship, as well as in their courses, at the upper-level undergraduate and graduate levels, as a main or supplementary text.

The second edition of the Handbook also includes a range of new research and teaching resources for both these readership groups with a list of websites as well as journal references that are specifically geared to each chapter's content. In addition, the second edition has an enhanced pedagogical feature at the end of each chapter that provides a set of key discussion questions intended as a praxis application for the ideas and concepts contained in each chapter.

The second edition's Handbook structure contains three primary sections that that represent a more finely tuned focus on theory and praxis, including the an enhanced set of case study research examples for each chapter that provide readers with a step-by- step praxis examples for conducting their own research projects.

Section one, "Feminist Perspectives on Knowledge Building,"

traces the historical rise of feminist research and begins with the early link of feminist epistemologies and perspectives within the research process. We trace the contours of early feminist inquiry and introduce the reader to the history, and historical debates, of and within feminist scholarship. We explore the androcentrism (male bias) in traditional research projects and the alternative set of questions feminist researchers bring to the research endeavor. We explore the political process of knowledge building by introducing the reader to the link between knowledge, authority, representation and power relations.

The chapters in Section One, introduce the unique knowledge frameworks feminists offer to enhance our understanding of the social reality. We explore some of the range of issues and questions feminists have addressed and the emphasis of feminist epistemologies and methodologies on understanding of the diversity of women's experiences, the commitment to the empowerment of women and other oppressed groups.

We examine a broad spectrum of the most important feminist perspectives and we take an in-depth look at how a given methodology intersects with epistemology and method to produce set of research practices. The Handbook's overall thesis is that any given feminist perspective does not preclude the use of specific methods, but serves to guide how a given method is practiced in the research process. While each feminist perspective is distinct, it sometimes shares elements with other perspectives. We discuss the similarities and differences across the spectrum of feminist perspectives on knowledge building.

Section two of the Handbook , "Feminist Research Praxis," examines how feminist researchers utilize a range of research methods in the service of feminist perspectives. Feminist researchers use a range of qualitative and quantitative as well as mixed and multi methods, and this section examines the unique characteristics feminists researchers bring to the practice of feminist research, by by maintaining a tight link between their theoretical perspectives and methods practices.

This section includes three new chapters. Deboleena Roy's chapter titled, "Feminist Approaches to Inquiry in the Natural Sciences: Practices for the Lab," tackles how feminist researchers go about their work within a natural science laboratory setting. She notes the importance of being reflexive of the range of ethical conundrums that are contained within practicing the scientific method. Roy suggests the importance of infusing laboratory research with a sense of "playfulness" and what she terms a "feeling around" in the pursuit of feminist laboratory knowledge building, that privileges a reaching out to other scientists in order to build a community of "togetherness" among researchers.

Stephanie Wahab, Ben Anderson-Nathe, and Christina Gringeri's new chapter, "Joining the Conversation: Social Work Contributions to Feminist Research," provides exemplary case studies of the practice of feminist research within a social work setting. Wahab et al. suggest that social work history of being grounded in praxis, ethics and reflection, can contribute to feminist knowledge building. In turn, social work's engagement with feminist theory, may help to disrupt the assumptions of knowledge contain in social work practice. Kristen Intemann's new chapter, "Putting Feminist Research Principles Into Practice," suggests that research principles of feminist praxis can benefit scientific research. Intemann proposes that scientific communities need to tend to issues of difference in the scientific research process by including diverse researchers (in terms of experiences, social positions, and values), that will serve to enhance a critical reflection on scientific research praxis with the goals of enhancing the perspective of the marginalized, and working towards a multiplicity of conceptual models.

Section III of the Handbook, "Feminist Issues and Insights in Practice and Pedagogy" examines some of the current tensions within feminist research and discusses a range of strategies for positioning of feminist research within the dominant research paradigms and emerging research practices. Section III also introduces some feminist "conundrums" regarding knowledge building that deal with issues of truth, reason logic and ethics. Section III also tackles the conceptualization of difference and its practice. In addition, it addresses how feminist researchers can develop an empowered feminist community of scholars across transnational space. Section three also focuses on issues within the practice of feminist pedagogy that includes a discussion of how feminists can or should convey the range of women's scholarship that differentiates it from the charge that women's studies scholarship conveys only ideology not knowledge.

A new chapter added to this section is Katherine Johnson's contribution titled, "Transgender, Transsexualism, and the Queering of Gender Identities: Debates for Feminist Research." Johnson examines some of the core issues of contention within queer studies with the goal of identify those theoretical perspectives that have particular relevance to feminist researchers. Johnson argues that feminist researchers need to be cognizant of the range of identity positions with regard to gender identities. Johnson encourages feminist researchers to explore definitions, terminology, and areas for coalitions in order to promote the crossing of identity borders. Johnson's work analyzes the dialogues between feminism and transgender, transsexual, and queer studies and at how the fields may work together to more robust research.

Sharlene Hesse-Biber and Abigail Brooks' introduction to this section remind us that "There is no one feminist viewpoint that defines feminist inquiry." But rather "feminists continue to engage in and dialogue across a range of diverse approaches to theory, praxis, and pedagogy" (Hesse-Biber & Brooks, this volume).

Sample Materials & Chapters

Chapter 1: FEMINIST RESEARCH

Chapter 2: FEMINIST EMPIRICISM

Select a Purchasing Option

This title is also available on SAGE Research Methods , the ultimate digital methods library. If your library doesn’t have access, ask your librarian to start a trial .

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Feminist Theory

Introduction.

- Anthologies

- Classic Texts

- Universalist Theories

- Psychoanalytic and Interactionist Theories

- Rejecting Universalism

- Intersectionality

- Deconstructing Gender

- Beyond Gender

- Postcolonialism and Transnationalism

- Methodology and Epistemology

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Contemporary Family Issues

- Doing Gender

- Family Policies

- Gender Stratification

- Human Trafficking

- Intersectionalities

- LGBT Social Movements

- Marriage and Divorce

- Masculinity

- Sex versus Gender

- Sexualities

- Social Stratification

- Social Theory

- Welfare Policy and Gender

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Global Racial Formations

- Transition to Parenthood in the Life Course

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Feminist Theory by Jennifer Carlson , Raka Ray LAST REVIEWED: 27 July 2011 LAST MODIFIED: 27 July 2011 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756384-0020

Feminist theory explores both inequality in gender relations and the constitution of gender. It is best understood as both an intellectual and a normative project. What is commonly understood as feminist theory accompanied the feminist movement in the mid-seventies, though there are key texts from the 19th and early- to mid-20th centuries that represent early feminist thought. Whereas feminist theories first began as an attempt to explain women’s oppression globally, following a grand theoretical approach akin to Marxism, the questions and emphases in the field have undergone some major shifts. Two primary shifts have been (1) from universalizing to particularizing and contextualizing women’s experiences and (2) from conceptualizing men and women as categories and focusing on the category “women” to questioning the content of that category, and moving to the exploration of gendered practices. Thus, while many theorists do focus on the question of how gender inequality manifests in institutions such as the workplace, home, armed forces, economy, or public sphere, others explore the range of practices that have come to be defined as masculine or feminine and how gender is constituted in relation to other social relations. Feminist theories can thus be used to explain how institutions operate with normative gendered assumptions and selectively reward or punish gendered practices. Many contemporary feminists look beyond the United States to focus on the effects of transnational economic, political, and cultural linkages on shaping gender.

While Signs and Feminist Studies were the first journals dedicated to interdisciplinary feminist work, there are now several specialist journals across the social sciences. Feminism & Psychology is a leading journal in psychology and gender, while Feminist Media Studies focuses on media and communication studies. Gender & Society is the top journal in sociology of gender. While Hypatia and Feminist Theory mainly publish feminist philosophy, their articles draw heavily on works across the humanities and the social sciences.

Feminism & Psychology .

A leading journal in gender and psychology, Feminism & Psychology features empirical and theoretical studies in psychology targeting audiences of both practitioners and academics.

Feminist Media Studies .

A transnational, transdisciplinary journal, Feminist Media Studies presents original empirical work on gender in the field of media and communication studies.

Feminist Studies .

Feminist Studies is a leading journal in feminist thought and politics. First published in 1972, its origins are directly traceable to American feminist activism in the late 1960s and early 1970s. True to its beginnings, the journal’s articles aim to provide both scholarly and political insight.

Feminist Theory .

This British interdisciplinary journal features feminist thought from scholars in a variety of disciplines within the social sciences and humanities.

Gender & Society .

The leading journal in the sociology of gender, Gender & Society features empirical research that provides theoretically sophisticated insights into gender as a core social phenomenon in society. The journal publishes work in sociology as well as anthropology, economics, history, political science, and social psychology.

Hypatia is a highly readable, engaging, and interdisciplinary journal of feminist philosophy that features cutting-edge work from feminist thinkers. First published in the 1980s, Hypatia ’s readership includes women studies scholars and philosophers.

First published in 1975, Signs has become a leading journal in feminist theory and gender studies. Its list of pathbreaking publications include work from Adrienne Rich, Evelyn Nakano Glenn, Raewyn Connell, Heidi Hartmann, Nancy Fraser, and Iris Marion Young, among others.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Sociology »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Actor-Network Theory

- Adolescence

- African Americans

- African Societies

- Agent-Based Modeling

- Analysis, Spatial

- Analysis, World-Systems

- Anomie and Strain Theory

- Arab Spring, Mobilization, and Contentious Politics in the...

- Asian Americans

- Assimilation

- Authority and Work

- Bell, Daniel

- Biosociology

- Bourdieu, Pierre

- Catholicism

- Causal Inference

- Chicago School of Sociology

- Chinese Cultural Revolution

- Chinese Society

- Citizenship

- Civil Rights

- Civil Society

- Cognitive Sociology

- Cohort Analysis

- Collective Efficacy

- Collective Memory

- Comparative Historical Sociology

- Comte, Auguste

- Conflict Theory

- Conservatism

- Consumer Credit and Debt

- Consumer Culture

- Consumption

- Contingent Work

- Conversation Analysis

- Corrections

- Cosmopolitanism

- Crime, Cities and

- Cultural Capital

- Cultural Classification and Codes

- Cultural Economy

- Cultural Omnivorousness

- Cultural Production and Circulation

- Culture and Networks

- Culture, Sociology of

- Development

- Discrimination

- Du Bois, W.E.B.

- Durkheim, Émile

- Economic Globalization

- Economic Institutions and Institutional Change

- Economic Sociology

- Education and Health

- Education Policy in the United States

- Educational Policy and Race

- Empires and Colonialism

- Entrepreneurship

- Environmental Sociology

- Epistemology

- Ethnic Enclaves

- Ethnomethodology and Conversation Analysis

- Exchange Theory

- Families, Postmodern

- Feminist Theory

- Field, Bourdieu's Concept of

- Forced Migration

- Foucault, Michel

- Frankfurt School

- Gender and Bodies

- Gender and Crime

- Gender and Education

- Gender and Health

- Gender and Incarceration

- Gender and Professions

- Gender and Social Movements

- Gender and Work

- Gender Pay Gap

- Gender, Sexuality, and Migration

- Gender, Welfare Policy and

- Gendered Sexuality

- Gentrification

- Gerontology

- Global Inequalities

- Globalization and Labor

- Goffman, Erving

- Historic Preservation

- Immigration

- Indian Society, Contemporary

- Institutions

- Intellectuals

- Interview Methodology

- Job Quality

- Knowledge, Critical Sociology of

- Labor Markets

- Latino/Latina Studies

- Law and Society

- Law, Sociology of

- LGBT Parenting and Family Formation

- Life Course

- Lipset, S.M.

- Markets, Conventions and Categories in

- Marxist Sociology

- Mass Incarceration in the United States and its Collateral...

- Material Culture

- Mathematical Sociology

- Medical Sociology

- Mental Illness

- Methodological Individualism

- Middle Classes

- Military Sociology

- Money and Credit

- Multiculturalism

- Multilevel Models

- Multiracial, Mixed-Race, and Biracial Identities

- Nationalism

- Non-normative Sexuality Studies

- Occupations and Professions

- Organizations

- Panel Studies

- Parsons, Talcott

- Political Culture

- Political Economy

- Political Sociology

- Popular Culture

- Proletariat (Working Class)

- Protestantism

- Public Opinion

- Public Space

- Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA)

- Race and Sexuality

- Race and Violence

- Race and Youth

- Race in Global Perspective

- Race, Organizations, and Movements

- Rational Choice

- Relationships

- Religion and the Public Sphere

- Residential Segregation

- Revolutions

- Role Theory

- Rural Sociology

- Scientific Networks

- Secularization

- Sequence Analysis

- Sexual Identity

- Sexuality Across the Life Course

- Simmel, Georg

- Single Parents in Context

- Small Cities

- Social Capital

- Social Change

- Social Closure

- Social Construction of Crime

- Social Control

- Social Darwinism

- Social Disorganization Theory

- Social Epidemiology

- Social History

- Social Indicators

- Social Mobility

- Social Movements

- Social Network Analysis

- Social Networks

- Social Policy

- Social Problems

- Social Psychology

- Socialization, Sociological Perspectives on

- Sociolinguistics

- Sociological Approaches to Character

- Sociological Research on the Chinese Society

- Sociological Research, Qualitative Methods in

- Sociological Research, Quantitative Methods in

- Sociology, History of

- Sociology of Manners

- Sociology of Music

- Sociology of War, The

- Suburbanism

- Survey Methods

- Symbolic Boundaries

- Symbolic Interactionism

- The Division of Labor after Durkheim

- Tilly, Charles

- Time Use and Childcare

- Time Use and Time Diary Research

- Tourism, Sociology of

- Transnational Adoption

- Unions and Inequality

- Urban Ethnography

- Urban Growth Machine

- Urban Inequality in the United States

- Veblen, Thorstein

- Visual Arts, Music, and Aesthetic Experience

- Wallerstein, Immanuel

- Welfare, Race, and the American Imagination

- Welfare States

- Women’s Employment and Economic Inequality Between Househo...

- Work and Employment, Sociology of

- Work/Life Balance

- Workplace Flexibility

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [195.158.225.244]

- 195.158.225.244

- Directories

- General Literary Theory & Criticism Resources

- African Diaspora Studies

- Critical Disability Studies

- Critical Race Theory

- Deconstruction and Poststructuralism

- Ecocriticism

- Feminist Theory

- Indigenous Literary Studies

- Marxist Literary Criticism

- Narratology

- New Historicism

- Postcolonial Theory

- Psychoanalytic Criticism

- Queer and Trans Theory

- Structuralism and Semiotics

- How Do I Use Literary Criticism and Theory?

- Start Your Research

- Research Guides

- University of Washington Libraries

- Library Guides

- UW Libraries

- Literary Research

Literary Research: Feminist Theory

What is feminist theory.

"An extension of feminism’s critique of male power and ideology, feminist theory combines elements of other theoretical models such as psychoanalysis, Marxism, poststructuralism, and deconstruction to interrogate the role of gender in the writing, interpretation, and dissemination of literary texts. Originally concerned with the politics of women’s authorship and representations of women in literature, feminist theory has recently begun to examine ideas of gender and sexuality across a wide range of disciplines including film studies, geography, and even economics."

Brief Overviews:

- Feminism (Bloomsbury Handbook of Literary and Cultural Theory)

- Feminism (Routledge Companion to Critical and Cultural Theory)

- Feminist Literary Theory (Feminism in Literature: A Gale Critical Companion)

- Feminist Theory (Literary Theory Handbook)

- Feminist Theory (Oxford Research Encyclopedias)

Notable Scholars:

Luce Irigaray

- Irigaray, Luce., and Margaret Whitford. The Irigaray Reader . Basil Blackwell, 1991.

- Irigaray, Luce, and Gillian Gill. Speculum of the Other Woman . Cornell University Press, 1985.

- Irigaray, Luce., and Carolyn Burke. This Sex Which Is Not One . Cornell University Press, 1985.

Julia Kristeva

- Kristeva, Julia, and Toril. Moi. The Kristeva Reader. Basil Blackwell, 1986.

- Kristeva, Julia, et al. Desire in Language: A Semiotic Approach to Literature and Art. Columbia University Press, 1980.

Kate Millett

- Millett, Kate. Sexual Politics . Doubleday, 1970.

Jennifer Nash

- Nash, Jennifer C. Birthing Black Mothers. Duke University Press, 2021.

- Nash, Jennifer C. The Black Body in Ecstasy: Reading Race, Reading Pornography . Duke University Press, 2014.

- Nash, Jennifer C. Black Feminism Reimagined: After Intersectionality . Duke University Press, 2019.

Christina Sharpe

- Sharpe, Christina Elizabeth. In the Wake: In Blackness and Being . Duke University Press, 2016.

- Sharpe, Christina Elizabeth. Monstrous Intimacies: Making Post-Slavery Subjects . Duke University Press, 2010.

Elaine Showalter

- Showalter, Elaine. A Literature of Their Own: British Women Novelists from Brontë to Lessing . Princeton University Press, 1999.

Hortense Spillers

- Spillers, Hortense J. Black, White, and in Color: Essays on American Literature and Culture . University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- Pryse, Marjorie, and Hortense J. Spillers. Conjuring: Black Women, Fiction, and Literary Tradition . Indiana University Press, 1985.

Introductions & Anthologies

Also see other recent eBooks discussing or using feminist theory in literature and scholar-recommended sources on Julia Kristeva and Luce Irigaray via Oxford Bibliographies.

Definition from: " Feminist Theory ." Glossary of Poetic Terms. Poetry Foundation.(24 July 2023)

- << Previous: Ecocriticism

- Next: Formalism >>

- Last Updated: Jun 12, 2024 2:03 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uw.edu/research/literaryresearch

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Affective Science

- Biological Foundations of Psychology

- Clinical Psychology: Disorders and Therapies

- Cognitive Psychology/Neuroscience

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational/School Psychology

- Forensic Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems of Psychology

- Individual Differences

- Methods and Approaches in Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational and Institutional Psychology

- Personality

- Psychology and Other Disciplines

- Social Psychology

- Sports Psychology

- Back to results

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Feminist psychology in north america.

- Kate Sheese Kate Sheese Sigmund Freud University Berlin

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.665

- Published online: 25 March 2021

Feminist psychology as an institutionalized field in North America has a relatively recent history. Its formalization remains geographically uneven and its institutionalization remains a contested endeavor. Women’s liberation movements, anticolonial struggles, and the civil rights movement acted as galvanizing forces in bringing feminism formally into psychology, transforming not only its sexist institutional practices but also its theories, and radically challenging its epistemological and methodological commitments and constraints. Since the late 1960s, feminists in psychology have produced radically new understandings of sex and gender, have recovered women’s history in psychology, have developed new historiographical methods, have engaged with and developed innovative approaches to theory and research, and have rendered previously invisibilized issues and experiences central to women’s lives intelligible and worthy of scholarly inquiry. Heated debates about the potential of feminist psychology to bring about radical social and political change are ongoing as feminists in the discipline negotiate threats and dilemmas related to collusion, colonialism, and co-optation in the face of ongoing commitments to positivism and individualism in psychology and as the theory and practice of psychology remains embedded within broader structures of neoliberalism and global capitalism.

- women’s liberation movement

- sex differences

- intersectionality

- epistemology

- gender-based violence

- sexual subjectivities

- feminist therapy

- psychiatric diagnosis

- neoliberalism

Introduction

Feminist psychology as an institutionalized field in North America has a relatively recent history. Its formalization remains geographically uneven, linked to the institutionalized status of psychology, varying definitions and enactments of feminism, and local political struggles and strategies in different geopolitical regions (Rutherford et al., 2011 ). In the United States and Canada, feminist psychology was institutionalized in the late 1960s and early 1970s, in tandem with the second-wave women’s movement. As global power relations and the hegemony of American psychology began to be challenged through anticolonial movements and liberation struggles of the 1960s, the women’s movement added to the political and intellectual momentum and was seized upon to center feminist concerns in psychology, effectively establishing a new field of inquiry and practice (Pickren & Rutherford, 2010 ).

Even where feminist psychology has an institutionalized presence, it has not taken the form of a unified or uncontested epistemological or political endeavor. The historical pairing of feminism and psychology has been, and remains, diverse, complex, and linked to the shifting discourses of gender and sexuality (Rutherford & Pettit, 2015 ); structures of racism, White supremacy, and neocolonialism (Rutherford et al., 2011 ); and economic and political ideologies (Liebert et al., 2011 ).

Early Inroads

Despite the field’s more recent institutionalization, efforts by women to identify and subvert sexist assumptions and practices in American psychology have a much longer history, dating back to the discipline’s establishment in the late 1800s, in the midst of first-wave feminism. Overcoming significant barriers to participation in higher education and scientific work, a small cohort of women held higher degrees in psychology in the late 19th century and early 20th century (Rutherford et al., 2013 ). Many of these psychologists, such as Christine Ladd-Franklin ( 1847–1930 ), Helen Thompson Wooley ( 1874–1947 ), and Leta Stetter Hollingworth ( 1886–1939 ), were women’s rights supporters and activists, and they used their hard-earned professional status to confront sexist barriers in psychology and to bring feminist values to bear on their empirical work. Christine Ladd-Franklin, for example, repeatedly challenged the Society of Experimentalists’ barring of women from their meetings. Although her efforts to change the Society of Experimentalists’ policy were unsuccessful, she found other means to increase women’s participation in psychology, establishing the Sarah Berliner Postdoctoral Fellowship in 1909 , which enabled women who had recently been awarded a PhD to continue their work at an institution of their choice (Rutherford et al., 2013 ).

The institutionalization of psychology occurred significantly later in Canada than in the United States. In Canada, separate psychology departments were established in the 1920s, and Canada’s national professional organization formed in 1939 , 47 years after its American equivalent (Wright & Myers, 1982 ). Thus, the first cohort of women in Canadian psychology entered the field later than their American counterparts and encountered fewer institutional and educational barriers (Keates & Stam, 2009 ). Some of the challenges they did face, however, were comparable to those of their contemporaries in the second generation of women in American psychology: being ushered into less prestigious applied work, being denied access to laboratories by male professors, and facing barriers to full-time academic work as a result of antinepotism rules (Gul et al., 2013 ).

Helen Thompson Wooley and Leta Stetter Hollingworth both used their empirical work to undermine prevailing sexist assumptions about women’s nature and abilities (see Shields, 1975a ). Helen Thompson Wooley developed the first dissertation in psychology addressing sex differences, The Mental Traits of Sex (Thompson, 1903 ). As part of her dissertation, she reviewed the existing literature on male–female differences and conducted her own empirical study comparing the motor and sensory abilities of a group of men with those of a group of women. Both her literature review and her study found little evidence for sex differences; indeed, she found that men and women exhibited more similarities than differences on most tests (Rutherford et al., 2013 ). Thompson Wooley’s conclusion that the influence of different social environments and expectations should be considered anticipated the position of future feminist psychologists.

Leta Stetter Hollingworth very explicitly engaged feminism in her psychological work. Indeed, her participation in a variety of feminist, radical, intellectual groups in the early 1900s likely influenced her research challenging two prevalent social beliefs about women’s inferiority and unsuitability for certain types of work: the variability hypothesis and the functional periodicity hypothesis (Rutherford et al., 2013 ; Shields, 1975b ). The variability hypothesis posited that men had a greater range and variability of psychological and physical traits than women had; if true, the hypothesis would account for greater numbers of men of both superior and inferior capacity and for women’s mediocrity. The functional periodicity hypothesis suggested that women’s menstrual periods rendered them dysfunctional for a certain portion of each month, which would preclude them from performing certain types of work.

Hollingworth challenged both hypotheses in the article “Science and Feminism” (Lowie & Hollingworth, 1916 ), which she wrote with Robert Lowie, a former student of cultural anthropologist Franz Boas. Hollingworth and Lowie both served on the Committee on the Biological Status of Women of the Feminist Alliance, an association founded in 1914 with a commitment to dismantling barriers to employment for women based on sex discrimination. In their article, Hollingworth and Lowie extensively reviewed anthropological, anthropometric, and psychological research, including Hollingworth’s own, and found no evidence for innate differences in ability that would affect women’s ability to work. Hollingworth pointed out that the variability hypothesis endured despite the fact that scientific studies had already persuaded many scientists that beliefs about women’s intellectual inferiority and men’s increased variability were unfounded (Rutherford et al., 2013 ). In Lowie and Hollingworth’s response to the functional periodicity hypothesis, their review of the literature related to menstrual impairment yielded no evidence supporting the hypothesis; rather, they found “a veritable mass of conflicting statements by men of science, misogynists, practitioners, and general writers” (Lowie & Hollingworth, 1916 , p. 283). The authors concluded, as Thompson Wooley had just over a decade earlier (in 1903 ), that social conditions were determining factors in women’s abilities and activities.

In the United States, feminism as an organized political movement largely dissolved after women won the right to vote in 1920 . In the postwar period, the field of psychology, mirroring shifts in society more broadly, saw a revival of gender stereotypes and roles (Pickren & Rutherford, 2010 ). While there was little collective feminist action in society and in psychology at this time, one notable exception was the National Council of Women Psychologists (NCWP)—its formation in 1941 was a direct response to women’s exclusion from participating in the Emergency Committee in Psychology. The NCWP emerged from ongoing discussions among about 50 New York–based women, and by 1942 it had a membership of nearly 250 doctoral-level women psychologists whose initiatives included the selection of women for the military, preparation of recommendations on how to remain calm in war, and advice on childrearing for working mothers (Capshew & Laszlo, 1986 ). Although the values of the individual members and the overall council were not explicitly feminist, their organizing and their work challenged sexist barriers to professional participation in psychology and helped to sustain interest in women’s issues (Johnson & Johnston, 2010 ).

Beliefs about sex roles and innate abilities took on renewed pertinence after World War II as American soldiers returned and were reintegrated into the professional positions many women had filled in their absence. The NCWP and the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues (SPSSI) formed a joint committee to address the roles of men and women in postwar society. As part of the committee’s work, Georgene Seward ( 1902–1992 ), a social and clinical psychologist, published a book, Sex and the Social Order ( 1946 ), which reviewed sex differences in behavior across different species. Seward concluded that the basis of sex differences was increasingly social as one moved along the evolutionary spectrum, and that the overwhelming tendency to assign human social roles according to biological sex produced significant psychological distress and conflict (Rutherford et al., 2013 ).

In the last chapter of her book, Seward made a series of recommendations for the fundamental reconfiguration of traditional sex roles, which she argued was necessary for establishing a successful and democratic postwar society. The recommendations included promoting traditionally feminine values in the socialization of all children, training girls in mathematics and mechanics, training boys in child care and parenting, and developing cooperative housing, day care, and economic reforms that would promote equal participation of both men and women in the workforce. Seward’s work had limited impact at the time, and it took until the 1960s for radical reconfigurations like those Seward proposed to gain cultural and political resonance.

The Women’s Liberation Movement and the Rooting of Feminist Psychology

In 1966 , as the women’s liberation movement gained momentum, the National Organization for Women (NOW) formed and issued a mandate that echoed Seward’s earlier recommendations (Rutherford et al., 2013 ), with demands for a national system of child care, for a reconceptualization of marriage that included the sharing of domestic and childrearing responsibilities, and for the end to exclusionary professional policies and practices that belittled women and fostered their self-denigration and dependence (Rosenberg, 2008 ). The vociferous critiques of existing structures and values of American society that were expressed by the civil rights movement, the New Left, and the antiwar movement throughout the 1960s propelled many women into political action. Many women in psychology were active in these movements, and it was not difficult for them to identify professional practices of discrimination, exclusion, harassment, and discrediting and at the same time to begin to articulate the ways in which psychology was itself complicit in producing and legitimating the concepts, categories, and structures through which women were (mis)understood, marginalized, and violated.

The women’s liberation movement was a galvanizing force in bringing feminism formally into psychology, and feminists in psychology transformed not only its sexist institutional practices but also its theories, and they radically challenged its epistemological and methodological commitments and constraints. Indeed, since the late 1960s, feminists in psychology have produced radically new understandings of sex and gender, have recovered women’s history in psychology, have developed new historiographical methods, have engaged with and developed innovative approaches to theory and research, and have rendered previously invisibilized issues and experiences central to women’s lives intelligible and worthy of scholarly inquiry (see Morawski, 1994 ).

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, women in psychology began organizing to protest sexist institutional practices, to challenge psychology’s androcentric theories, and to secure a platform for women’s work. In 1968 , Naomi Weisstein ( 1939–2015 ) delivered a paper that became a foundational text in feminist psychology; the text was published in 1971 under the title Psychology Constructs the Female . In this work, Weisstein argued that psychology had failed to produce any valid knowledge about women or their experiences, a failure she linked to psychologists’ focus on inner traits at the expense of considering social context and to a reliance on unscientific theories and on examples of sexed behavior in specific animals that mirrored social relations in humans while ignoring those that didn’t.

Pioneering work like Weisstein’s, along with effective political activism by other groups in psychology, such as Psychologists for Social Responsibility’s successful campaign to have the American Psychological Association (APA) relocate its annual convention in protest of police brutality in Chicago in 1968 , inspired a sense that the status quo in psychology could be challenged and changed (Tiefer, 1991 ). Women began organizing informal meetings and formal associations to challenge the status quo. In 1969 , several groups of women organized unofficial but very well-attended symposiums, paper sessions, and workshops for the APA convention (Rutherford et al., 2013 ). During these sessions, women circulated petitions demanding that the APA rectify sexist discrimination in the organization and in psychology departments and calling for the APA to pass a resolution confirming abortion as a civil right. Following the meetings, a group of around 35 men and women psychologists continued to meet, laying the groundwork for the formation of the Association of Women in Psychology (AWP). In 1970 , the AWP developed several resolutions and motions related to sexist institutional practices that it presented to the APA. The APA responded by appointing a Task Force on the Status of Women, which produced a report documenting inequities in the field. A key recommendation was to develop a division within the APA to address deficiencies in psychological knowledge about women. Division 35, the Division of the Psychology of Women, was formally approved in 1973 , despite covert resistance (Rutherford et al., 2013 ).

In Canada, organizing followed a similar trajectory. In 1972 , a hugely popular underground symposium was held parallel to the annual convention of the Canadian Psychological Association (CPA) and was followed in the coming years by the convening of the Task Force on the Status of Women in Canadian Psychology (Pyke, 2001 ). In 1976 , the Task Force presented nearly 100 recommendations to the board of directors, including the establishment of a special interest group on the psychology of women, which became what is now the Section on Women and Psychology (SWAP; Rutherford et al., 2013 ).

In addition to offering official spaces for engaging with feminist concerns in psychology, these organizations also provided opportunities for networking and mentorship and for important psychosocial support, often serving as a refuge from hostile and belittling professional environments (Unger et al., 2010 ). The associations also spawned professional journals, securing venues for the publication of feminist empirical research and theory and legitimizing the psychology of women and gender as a scholarly pursuit (Rutherford & Yoder, 2011 ).

As women increasingly staked out spaces for academic exchange and the development of a psychology of and for women, they also began to explore and address the invisibility of women in accounts of psychology’s history. In 1974 , Maxine Bernstein and Nancy Russo published “The History of Psychology Revisited, or Up With Our Foremothers,” an article in which they argued that androcentric biases and documenting practices in psychology had led many to assume, incorrectly, that women had not contributed in significant ways to the development of psychology. What started as an important recovery project, searching for information about women’s contributions and repositioning women in the historical record (see Bernstein & Russo, 1974 ; Furumoto, 1979 ; Shields, 1975b ), developed into more nuanced analyses of the structural conditions and social relations that shaped women’s experiences as psychologists (see Johnston & Johnson, 2008 ; Scarborough & Furumoto, 1987 ). In the 21st century , historiographical work has taken gender as a category of analysis, interrogating how psychologists have participated in constructing gender—that is, how they have understood, deployed, and reified notions of sex and gender (Rutherford & Pettit, 2015 ).

Products, Tensions, and Dilemmas of Feminist Psychology

Reconceptualizing sex and gender, sex differences.

Beliefs about women’s inferiority linked to biologically based sex differences have persisted well beyond the early years of psychology, and discrediting these assumptions continues to be a focus of feminist work. As Helen Thompson Wooley and Leta Stetter Hollingworth did in the early 1900s, many psychologists have relied on forms of feminist empiricism, that is:

the conviction that if scientific research were done carefully and objectively enough, the results would dismantle and undermine the unscientific and biased assumptions that formed the basis of these commonly held beliefs. (Pickren & Rutherford, 2010 , p. 268)

In 1974 , Eleanor Maccoby ( 1917–2018 ) and Carol Jacklin ( 1939–2011 ) published The Psychology of Sex Differences , a book based on their comprehensive review of hundreds of studies on sex differences. The aim of their work was to assess the validity of a range of purported sex differences and to review the theoretical positions on their sources. Maccoby and Jacklin ( 1974 ) concluded that there was empirical evidence to support differences in just four out of more than 80 traits or skills, and they suggested that sex-typed behaviors were likely the result of a social learning process that was built on biological foundations (for a more detailed description, see Rutherford et al., 2013 ). Although both women were feminists, active in the social justice movements of the 1960s (Ball, 2011 ), they did not identify their work as feminist. Indeed, some feminist psychologists have criticized Maccoby and Jacklin’s emphasis on the biological origins of sex differences, despite the authors’ explicit conviction that biology is not destiny (Rutherford et al., 2013 ).

The publication and popularity of E. O. Wilson’s Sociobiology: A New Synthesis in 1975 further ignited controversy, due to its claim that genetic inheritance is responsible for social behavior. Concerned about the position of genetic determinism and about the dangerous potential to justify sexism and racism, Ethel Tobach ( 1921–2015 ), a comparative psychologist at the American Museum of Natural History, and Betty Rosoff, an endocrinologist and professor of biology at Yeshiva University, formed the Genes and Gender Collective. The collective organized their first meeting as a daylong symposium with the aim of challenging genetic determinism on a scientific level and demonstrating its discriminatory effects against women, children, and ethnic minorities. The meeting generated massive and unexpected interest, and over 350 women from diverse backgrounds attended (Rutherford et al., 2010 ). In 1978 , based on their initial symposium, the collective published the first issue of their seven-volume series Genes and Gender . The collective went on to hold conferences focusing on pressing scientific and social issues, including genetic determinism and children, women’s health and the intersection of gender and race/ethnicity, the effects of economic policies, and the societal origins of peace and war. Their final volume, published in 1994 , was titled Challenging Racism and Sexism: Alternatives to Genetic Explanations ; it had emerged from the group’s efforts to counter the interest in J. Philippe Rushton’s repeated argument that differences among Asians, Europeans, and Africans on several measures, including intelligence, were genetically determined (Rutherford et al., 2010 ).

Debates about sex differences continue, with sustained interest in genetic and evolutionary explanations and more recent appeals to differences in neurological “hard-wiring” (Fine, 2008 ). Feminist psychologists continue to deconstruct, refute, and elucidate the stakes of these claims (see Fine, 2013 ; Fine et al., 2013 ).

Developing Gender

The term “gender” made its debut in psychology with John Money’s introduction of the phrase “gender roles” in 1955 (Downing et al., 2015 ; Rutherford et al., 2013 ). The term did not really gain traction, however, until the late 1970s. In 1979 , Rhoda Unger ( 1939–2019 ) distinguished between “sex,” referring to biological maleness and femaleness, and “gender,” referring to socially constructed characteristics and traits, in her widely circulated article, “Towards a Redefinition of Sex and Gender.” The conceptual clarity brought about by this distinction allowed psychologists to move beyond the empirical testing of differences. It opened a conceptual space for more relational, political, and process-oriented questions about how people, relationships, and practices become gendered, about the different ways gender might be expressed and interpreted, about the ways gender regulates access to power, and about how gender interacts with other social formations (Pickren & Rutherford, 2010 ).

In the 1970s, work on masculinity and femininity (e.g., Bem, 1974 ; Constantinople, 1973 ; Rubin, 1975 ) had already begun to pry open this conceptual space, challenging the conceptualization and measurement of masculinity and femininity as essential qualities of being male or female and as being mutually exclusive. Sandra Bem ( 1944–2014 ) was highly influential in this respect. She was actively engaged in the women’s liberation movement, and her earliest research ( 1973 ) on sex roles demonstrated that sex-biased job ads “aided and abetted” sex discrimination in women’s recruitment into the workforce. Based on this research, her expert testimony in landmark legal cases contributed to changes in sex-biased recruitment practices (George, 2012 ). Bem’s subsequent work extended Constantinople’s (1973) argument against the measurement of masculinity and femininity as opposite ends of a bipolar continuum, suggesting that individuals could adopt both traits. Bem ( 1974 ) introduced the notion of an androgynous sex-role identity, wherein individuals possess and enact both masculine and feminine qualities, and she argued that this flexibility was, in fact, a requisite for healthy psychological functioning. She devised the Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI), an alternate measure of sex-related attributes, which allowed respondents to endorse characteristics of both or neither femininity and masculinity. Bem’s work on androgyny and its measurement was subjected to substantial conceptual and methodological critique. Indeed, her work generated a great deal of debate as well as reconceptualization of sex and gender, and it has spawned ongoing inquiry into gender identity by others in the field. Related work in the first decades of the 21st century has engaged with queer theory as well as intersex, trans/nonbinary gender activism and scholarship, reworking conceptualizations of sex and gender, challenging cisnormative assumptions and practices in psychology, and resisting the pathologization of non-cisgender identities (see Richmond et al., 2012 ; Richmond & Sheese, 2010 ; Singh et al., 2013 ).

In the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s, several feminist psychologists developed new approaches to understanding and valuing gender differences. These psychologists reassessed attributes traditionally ascribed to women, recasting them not as deficiencies or signs of immaturity, but as unique strengths and capacities for relationality and connectedness. Jean Baker Miller ( 1927–2006 ) first articulated the need to redescribe and re-evaluate feminine traits on women’s terms in her classic text, Toward a New Psychology of Women ( 1976 ). She argued that women’s needs for emotional connection and empathy as well as their capacities for care and nurturance were psychological essentials and the foundation of a more advanced way of living. Baker Miller went on to develop a relational-cultural model of psychological development that cast the ability to sustain relationships as fundamental to human growth, and disconnectedness as a threat to psychological health. She focused on how gendered power imbalances produced disconnectedness, compelling individuals to hide or to distort their authentic feelings. Subsequent work at the Stone Center at Wellesley College has developed analyses of how other structural forms of discrimination, such as racism, classism, and heterosexism, also generate relational fractures (Pickren & Rutherford, 2010 ).

In 1982 , Carol Gilligan published In a Different Voice , where she described a distinct style of moral reasoning she had identified in women’s moral decision-making processes, which she called “an ethic of care.” Following the landmark decision in Roe v. Wade , which made abortion legal in the United States, Gilligan was interested in understanding how women might approach the decision to terminate a pregnancy. In interviews on the subject, Gilligan found that women often relied on a relational framework to navigate their dilemmas. Rather than drawing on supposedly universal ethical codes, which was believed to reflect the highest stage of moral development, women kept relationships at the center of their considerations and used feeling and thinking as the basis for their decision-making. Elaborating an ethic of care exposed the androcentric biases of prevailing psychological models of moral development, clarified why women’s proposals for resolving moral dilemmas did not register within the models’ measures, and refuted the notion that women typically achieved a lower level of moral development than men.

Both Baker Miller’s and Gilligan’s work have been criticized for contributing to the reification of sex differences and for essentializing women (Pickren & Rutherford, 2010 ). The essentialism criticism did not uniquely apply to their work. Indeed, the majority of the research emerging from the first decades of institutionalized feminist psychology has been judged essentialist. These scholars largely relied on and reproduced a unified category of “woman” that ignored the diversity and specificity of women’s experiences. Throughout the 1980s, there were mounting calls to rectify the ways in which essentialist visions of womanhood systematically excluded the experiences and voices of women of color, in particular, or constructed marginalized communities as social problems (Anzaldúa & Moraga, 1981 ; hooks, 1981 ). Throughout the 1990s, feminists in psychology who were concerned about understanding and dismantling interlocking systems of racism, sexism, classism, and ableism developed new theoretical tools and new modes of inquiry to shed light on the dynamic interplay between different forms of structural inequality, identity, and subjectivity. Beginning in the 1990s, novel methodologies and reflexive practices of South African feminists reflected critical concern with the ideal of a shared sisterhood, nonracialism, and voice and representation in South African feminist psychology (Kiguwa & Langa, 2011 ). This range of projects took up earlier critiques of science, drawing on constructionist and standpoint theories and engaged intersectionality theory, Black feminist thought, critical race theory, and feminist postcolonial critiques of Western feminism.

Approaches to Knowledge

Social constructionism.