Sample Size Policy for Qualitative Studies Using In-Depth Interviews

- Published: 12 September 2012

- Volume 41 , pages 1319–1320, ( 2012 )

Cite this article

- Shari L. Dworkin 1

296k Accesses

565 Citations

28 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In recent years, there has been an increase in submissions to the Journal that draw on qualitative research methods. This increase is welcome and indicates not only the interdisciplinarity embraced by the Journal (Zucker, 2002 ) but also its commitment to a wide array of methodologies.

For those who do select qualitative methods and use grounded theory and in-depth interviews in particular, there appear to be a lot of questions that authors have had recently about how to write a rigorous Method section. This topic will be addressed in a subsequent Editorial. At this time, however, the most common question we receive is: “How large does my sample size have to be?” and hence I would like to take this opportunity to answer this question by discussing relevant debates and then the policy of the Archives of Sexual Behavior . Footnote 1

The sample size used in qualitative research methods is often smaller than that used in quantitative research methods. This is because qualitative research methods are often concerned with garnering an in-depth understanding of a phenomenon or are focused on meaning (and heterogeneities in meaning )—which are often centered on the how and why of a particular issue, process, situation, subculture, scene or set of social interactions. In-depth interview work is not as concerned with making generalizations to a larger population of interest and does not tend to rely on hypothesis testing but rather is more inductive and emergent in its process. As such, the aim of grounded theory and in-depth interviews is to create “categories from the data and then to analyze relationships between categories” while attending to how the “lived experience” of research participants can be understood (Charmaz, 1990 , p. 1162).

There are several debates concerning what sample size is the right size for such endeavors. Most scholars argue that the concept of saturation is the most important factor to think about when mulling over sample size decisions in qualitative research (Mason, 2010 ). Saturation is defined by many as the point at which the data collection process no longer offers any new or relevant data. Another way to state this is that conceptual categories in a research project can be considered saturated “when gathering fresh data no longer sparks new theoretical insights, nor reveals new properties of your core theoretical categories” (Charmaz, 2006 , p. 113). Saturation depends on many factors and not all of them are under the researcher’s control. Some of these include: How homogenous or heterogeneous is the population being studied? What are the selection criteria? How much money is in the budget to carry out the study? Are there key stratifiers (e.g., conceptual, demographic) that are critical for an in-depth understanding of the topic being examined? What is the timeline that the researcher faces? How experienced is the researcher in being able to even determine when she or he has actually reached saturation (Charmaz, 2006 )? Is the author carrying out theoretical sampling and is, therefore, concerned with ensuring depth on relevant concepts and examining a range of concepts and characteristics that are deemed critical for emergent findings (Glaser & Strauss, 1967 ; Strauss & Corbin, 1994 , 2007 )?

While some experts in qualitative research avoid the topic of “how many” interviews “are enough,” there is indeed variability in what is suggested as a minimum. An extremely large number of articles, book chapters, and books recommend guidance and suggest anywhere from 5 to 50 participants as adequate. All of these pieces of work engage in nuanced debates when responding to the question of “how many” and frequently respond with a vague (and, actually, reasonable) “it depends.” Numerous factors are said to be important, including “the quality of data, the scope of the study, the nature of the topic, the amount of useful information obtained from each participant, the use of shadowed data, and the qualitative method and study designed used” (Morse, 2000 , p. 1). Others argue that the “how many” question can be the wrong question and that the rigor of the method “depends upon developing the range of relevant conceptual categories, saturating (filling, supporting, and providing repeated evidence for) those categories,” and fully explaining the data (Charmaz, 1990 ). Indeed, there have been countless conferences and conference sessions on these debates, reports written, and myriad publications are available as well (for a compilation of debates, see Baker & Edwards, 2012 ).

Taking all of these perspectives into account, the Archives of Sexual Behavior is putting forward a policy for authors in order to have more clarity on what is expected in terms of sample size for studies drawing on grounded theory and in-depth interviews. The policy of the Archives of Sexual Behavior will be that it adheres to the recommendation that 25–30 participants is the minimum sample size required to reach saturation and redundancy in grounded theory studies that use in-depth interviews. This number is considered adequate for publications in journals because it (1) may allow for thorough examination of the characteristics that address the research questions and to distinguish conceptual categories of interest, (2) maximizes the possibility that enough data have been collected to clarify relationships between conceptual categories and identify variation in processes, and (3) maximizes the chances that negative cases and hypothetical negative cases have been explored in the data (Charmaz, 2006 ; Morse, 1994 , 1995 ).

The Journal does not want to paradoxically and rigidly quantify sample size when the endeavor at hand is qualitative in nature and the debates on this matter are complex. However, we are providing this practical guidance. We want to ensure that more of our submissions have an adequate sample size so as to get closer to reaching the goal of saturation and redundancy across relevant characteristics and concepts. The current recommendation that is being put forward does not include any comment on other qualitative methodologies, such as content and textual analysis, participant observation, focus groups, case studies, clinical cases or mixed quantitative–qualitative methods. The current recommendation also does not apply to phenomenological studies or life history approaches. The current guidance is intended to offer one clear and consistent standard for research projects that use grounded theory and draw on in-depth interviews.

Editor’s note: Dr. Dworkin is an Associate Editor of the Journal and is responsible for qualitative submissions.

Baker, S. E., & Edwards, R. (2012). How many qualitative interviews is enough? National Center for Research Methods. Available at: http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/2273/ .

Charmaz, K. (1990). ‘Discovering’ chronic illness: Using grounded theory. Social Science and Medicine, 30 , 1161–1172.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis . London: Sage Publications.

Google Scholar

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research . Chicago: Aldine Publishing Co.

Mason, M. (2010). Sample size and saturation in PhD studies using qualitative interviews. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11 (3) [Article No. 8].

Morse, J. M. (1994). Designing funded qualitative research. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 220–235). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Morse, J. M. (1995). The significance of saturation. Qualitative Health Research, 5 , 147–149.

Article Google Scholar

Morse, J. M. (2000). Determining sample size. Qualitative Health Research, 10 , 3–5.

Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. M. (1994). Grounded theory methodology. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 273–285). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. M. (2007). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Zucker, K. J. (2002). From the Editor’s desk: Receiving the torch in the era of sexology’s renaissance. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 31 , 1–6.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, University of California at San Francisco, 3333 California St., LHTS #455, San Francisco, CA, 94118, USA

Shari L. Dworkin

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Shari L. Dworkin .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Dworkin, S.L. Sample Size Policy for Qualitative Studies Using In-Depth Interviews. Arch Sex Behav 41 , 1319–1320 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-0016-6

Download citation

Published : 12 September 2012

Issue Date : December 2012

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-0016-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Qualitative Study

Affiliations.

- 1 University of Nebraska Medical Center

- 2 GDB Research and Statistical Consulting

- 3 GDB Research and Statistical Consulting/McLaren Macomb Hospital

- PMID: 29262162

- Bookshelf ID: NBK470395

Qualitative research is a type of research that explores and provides deeper insights into real-world problems. Instead of collecting numerical data points or intervening or introducing treatments just like in quantitative research, qualitative research helps generate hypothenar to further investigate and understand quantitative data. Qualitative research gathers participants' experiences, perceptions, and behavior. It answers the hows and whys instead of how many or how much. It could be structured as a standalone study, purely relying on qualitative data, or part of mixed-methods research that combines qualitative and quantitative data. This review introduces the readers to some basic concepts, definitions, terminology, and applications of qualitative research.

Qualitative research, at its core, asks open-ended questions whose answers are not easily put into numbers, such as "how" and "why." Due to the open-ended nature of the research questions, qualitative research design is often not linear like quantitative design. One of the strengths of qualitative research is its ability to explain processes and patterns of human behavior that can be difficult to quantify. Phenomena such as experiences, attitudes, and behaviors can be complex to capture accurately and quantitatively. In contrast, a qualitative approach allows participants themselves to explain how, why, or what they were thinking, feeling, and experiencing at a particular time or during an event of interest. Quantifying qualitative data certainly is possible, but at its core, qualitative data is looking for themes and patterns that can be difficult to quantify, and it is essential to ensure that the context and narrative of qualitative work are not lost by trying to quantify something that is not meant to be quantified.

However, while qualitative research is sometimes placed in opposition to quantitative research, where they are necessarily opposites and therefore "compete" against each other and the philosophical paradigms associated with each other, qualitative and quantitative work are neither necessarily opposites, nor are they incompatible. While qualitative and quantitative approaches are different, they are not necessarily opposites and certainly not mutually exclusive. For instance, qualitative research can help expand and deepen understanding of data or results obtained from quantitative analysis. For example, say a quantitative analysis has determined a correlation between length of stay and level of patient satisfaction, but why does this correlation exist? This dual-focus scenario shows one way in which qualitative and quantitative research could be integrated.

Copyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC.

- Introduction

- Issues of Concern

- Clinical Significance

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

- Review Questions

Publication types

- Study Guide

How many participants do I need for qualitative research?

- Participant recruitment

- Qualitative research

6 min read David Renwick

For those new to the qualitative research space, there’s one question that’s usually pretty tough to figure out, and that’s the question of how many participants to include in a study. Regardless of whether it’s research as part of the discovery phase for a new product, or perhaps an in-depth canvas of the users of an existing service, researchers can often find it difficult to agree on the numbers. So is there an easy answer? Let’s find out.

Here, we’ll look into the right number of participants for qualitative research studies. If you want to know about participants for quantitative research, read Nielsen Norman Group’s article .

Getting the numbers right

So you need to run a series of user interviews or usability tests and aren’t sure exactly how many people you should reach out to. It can be a tricky situation – especially for those without much experience. Do you test a small selection of 1 or 2 people to make the recruitment process easier? Or, do you go big and test with a series of 10 people over the course of a month? The answer lies somewhere in between.

It’s often a good idea (for qualitative research methods like interviews and usability tests) to start with 5 participants and then scale up by a further 5 based on how complicated the subject matter is. You may also find it helpful to add additional participants if you’re new to user research or you’re working in a new area.

What you’re actually looking for here is what’s known as saturation.

Understanding saturation

Whether it’s qualitative research as part of a master’s thesis or as research for a new online dating app, saturation is the best metric you can use to identify when you’ve hit the right number of participants.

In a nutshell, saturation is when you’ve reached the point where adding further participants doesn’t give you any further insights. It’s true that you may still pick up on the occasional interesting detail, but all of your big revelations and learnings have come and gone. A good measure is to sit down after each session with a participant and analyze the number of new insights you’ve noted down.

Interestingly, in a paper titled How Many Interviews Are Enough? , authors Greg Guest, Arwen Bunce and Laura Johnson noted that saturation usually occurs with around 12 participants in homogeneous groups (meaning people in the same role at an organization, for example). However, carrying out ethnographic research on a larger domain with a diverse set of participants will almost certainly require a larger sample.

Ensuring you’ve hit the right number of participants

How do you know when you’ve reached saturation point? You have to keep conducting interviews or usability tests until you’re no longer uncovering new insights or concepts.

While this may seem to run counter to the idea of just gathering as much data from as many people as possible, there’s a strong case for focusing on a smaller group of participants. In The logic of small samples in interview-based , authors Mira Crouch and Heather McKenzie note that using fewer than 20 participants during a qualitative research study will result in better data. Why? With a smaller group, it’s easier for you (the researcher) to build strong close relationships with your participants, which in turn leads to more natural conversations and better data.

There’s also a school of thought that you should interview 5 or so people per persona. For example, if you’re working in a company that has well-defined personas, you might want to use those as a basis for your study, and then you would interview 5 people based on each persona. This maybe worth considering or particularly important when you have a product that has very distinct user groups (e.g. students and staff, teachers and parents etc).

How your domain affects sample size

The scope of the topic you’re researching will change the amount of information you’ll need to gather before you’ve hit the saturation point. Your topic is also commonly referred to as the domain.

If you’re working in quite a confined domain, for example, a single screen of a mobile app or a very specific scenario, you’ll likely find interviews with 5 participants to be perfectly fine. Moving into more complicated domains, like the entire checkout process for an online shopping app, will push up your sample size.

As Mitchel Seaman notes : “Exploring a big issue like young peoples’ opinions about healthcare coverage, a broad emotional issue like postmarital sexuality, or a poorly-understood domain for your team like mobile device use in another country can drastically increase the number of interviews you’ll want to conduct.”

In-person or remote

Does the location of your participants change the number you need for qualitative user research? Well, not really – but there are other factors to consider.

- Budget: If you choose to conduct remote interviews/usability tests, you’ll likely find you’ve got lower costs as you won’t need to travel to your participants or have them travel to you. This also affects…

- Participant access: Remote qualitative research can be a lifesaver when it comes to participant access. No longer are you confined to the people you have physical access to — instead you can reach out to anyone you’d like.

- Quality: On the other hand, remote research does have its downsides. For one, you’ll likely find you’re not able to build the same kinds of relationships over the internet or phone as those in person, which in turn means you never quite get the same level of insights.

Is there value in outsourcing recruitment?

Recruitment is understandably an intensive logistical exercise with many moving parts. If you’ve ever had to recruit people for a study before, you’ll understand the need for long lead times (to ensure you have enough participants for the project) and the countless long email chains as you discuss suitable times.

Outsourcing your participant recruitment is just one way to lighten the logistical load during your research. Instead of having to go out and look for participants, you have them essentially delivered to you in the right number and with the right attributes.

We’ve got one such service at Optimal Workshop, which means it’s the perfect accompaniment if you’re also using our platform of UX tools. Read more about that here .

So that’s really most of what there is to know about participant recruitment in a qualitative research context. As we said at the start, while it can appear quite tricky to figure out exactly how many people you need to recruit, it’s actually not all that difficult in reality.

Overall, the number of participants you need for your qualitative research can depend on your project among other factors. It’s important to keep saturation in mind, as well as the locale of participants. You also need to get the most you can out of what’s available to you. Remember: Some research is better than none!

Capture, analyze and visualize your qualitative data.

Try our qualitative research tool for usability testing, interviewing and note-taking. Reframer by Optimal Workshop.

Published on August 8, 2019

David Renwick

David is Optimal Workshop's Content Strategist and Editor of CRUX. You can usually find him alongside one of the office dogs 🐕 (Bella, Bowie, Frida, Tana or Steezy). Connect with him on LinkedIn.

Recommended for you

How to build rapport in a user interview

How exactly do you build rapport in a user interview? Here's all you need to know.

13 time-saving tips and tools for conducting great user interviews

Here are some of our best time-saving tips and tools for conducting effective user interviews.

Participant recruitment made easy and fast

Today we have an exciting new feature to announce. It's probably the most requested feature of all time for us.

Try Optimal Workshop tools for free

What are you looking for.

Explore all tags

Discover more from Optimal Workshop

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 21 November 2018

Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period

- Konstantina Vasileiou ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5047-3920 1 ,

- Julie Barnett 1 ,

- Susan Thorpe 2 &

- Terry Young 3

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 18 , Article number: 148 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

726k Accesses

1137 Citations

172 Altmetric

Metrics details

Choosing a suitable sample size in qualitative research is an area of conceptual debate and practical uncertainty. That sample size principles, guidelines and tools have been developed to enable researchers to set, and justify the acceptability of, their sample size is an indication that the issue constitutes an important marker of the quality of qualitative research. Nevertheless, research shows that sample size sufficiency reporting is often poor, if not absent, across a range of disciplinary fields.

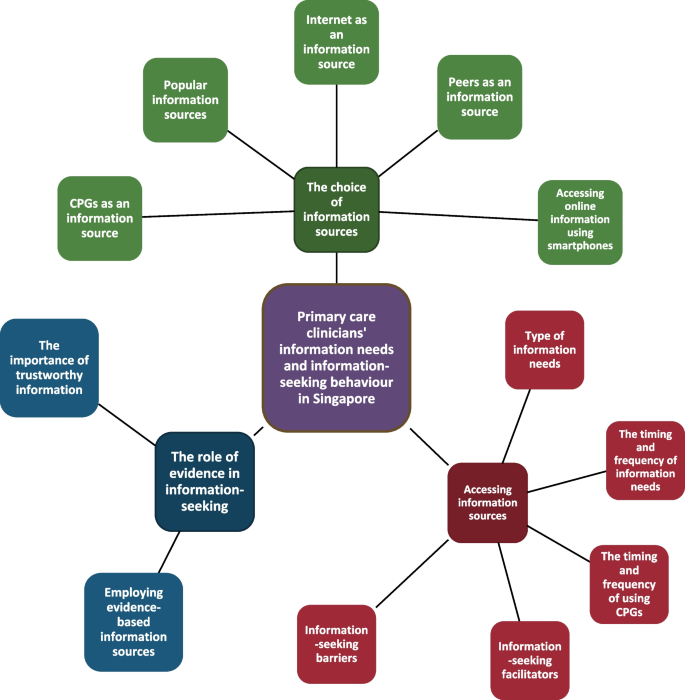

A systematic analysis of single-interview-per-participant designs within three health-related journals from the disciplines of psychology, sociology and medicine, over a 15-year period, was conducted to examine whether and how sample sizes were justified and how sample size was characterised and discussed by authors. Data pertinent to sample size were extracted and analysed using qualitative and quantitative analytic techniques.

Our findings demonstrate that provision of sample size justifications in qualitative health research is limited; is not contingent on the number of interviews; and relates to the journal of publication. Defence of sample size was most frequently supported across all three journals with reference to the principle of saturation and to pragmatic considerations. Qualitative sample sizes were predominantly – and often without justification – characterised as insufficient (i.e., ‘small’) and discussed in the context of study limitations. Sample size insufficiency was seen to threaten the validity and generalizability of studies’ results, with the latter being frequently conceived in nomothetic terms.

Conclusions

We recommend, firstly, that qualitative health researchers be more transparent about evaluations of their sample size sufficiency, situating these within broader and more encompassing assessments of data adequacy . Secondly, we invite researchers critically to consider how saturation parameters found in prior methodological studies and sample size community norms might best inform, and apply to, their own project and encourage that data adequacy is best appraised with reference to features that are intrinsic to the study at hand. Finally, those reviewing papers have a vital role in supporting and encouraging transparent study-specific reporting.

Peer Review reports

Sample adequacy in qualitative inquiry pertains to the appropriateness of the sample composition and size . It is an important consideration in evaluations of the quality and trustworthiness of much qualitative research [ 1 ] and is implicated – particularly for research that is situated within a post-positivist tradition and retains a degree of commitment to realist ontological premises – in appraisals of validity and generalizability [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ].

Samples in qualitative research tend to be small in order to support the depth of case-oriented analysis that is fundamental to this mode of inquiry [ 5 ]. Additionally, qualitative samples are purposive, that is, selected by virtue of their capacity to provide richly-textured information, relevant to the phenomenon under investigation. As a result, purposive sampling [ 6 , 7 ] – as opposed to probability sampling employed in quantitative research – selects ‘information-rich’ cases [ 8 ]. Indeed, recent research demonstrates the greater efficiency of purposive sampling compared to random sampling in qualitative studies [ 9 ], supporting related assertions long put forward by qualitative methodologists.

Sample size in qualitative research has been the subject of enduring discussions [ 4 , 10 , 11 ]. Whilst the quantitative research community has established relatively straightforward statistics-based rules to set sample sizes precisely, the intricacies of qualitative sample size determination and assessment arise from the methodological, theoretical, epistemological, and ideological pluralism that characterises qualitative inquiry (for a discussion focused on the discipline of psychology see [ 12 ]). This mitigates against clear-cut guidelines, invariably applied. Despite these challenges, various conceptual developments have sought to address this issue, with guidance and principles [ 4 , 10 , 11 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ], and more recently, an evidence-based approach to sample size determination seeks to ground the discussion empirically [ 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ].

Focusing on single-interview-per-participant qualitative designs, the present study aims to further contribute to the dialogue of sample size in qualitative research by offering empirical evidence around justification practices associated with sample size. We next review the existing conceptual and empirical literature on sample size determination.

Sample size in qualitative research: Conceptual developments and empirical investigations

Qualitative research experts argue that there is no straightforward answer to the question of ‘how many’ and that sample size is contingent on a number of factors relating to epistemological, methodological and practical issues [ 36 ]. Sandelowski [ 4 ] recommends that qualitative sample sizes are large enough to allow the unfolding of a ‘new and richly textured understanding’ of the phenomenon under study, but small enough so that the ‘deep, case-oriented analysis’ (p. 183) of qualitative data is not precluded. Morse [ 11 ] posits that the more useable data are collected from each person, the fewer participants are needed. She invites researchers to take into account parameters, such as the scope of study, the nature of topic (i.e. complexity, accessibility), the quality of data, and the study design. Indeed, the level of structure of questions in qualitative interviewing has been found to influence the richness of data generated [ 37 ], and so, requires attention; empirical research shows that open questions, which are asked later on in the interview, tend to produce richer data [ 37 ].

Beyond such guidance, specific numerical recommendations have also been proffered, often based on experts’ experience of qualitative research. For example, Green and Thorogood [ 38 ] maintain that the experience of most qualitative researchers conducting an interview-based study with a fairly specific research question is that little new information is generated after interviewing 20 people or so belonging to one analytically relevant participant ‘category’ (pp. 102–104). Ritchie et al. [ 39 ] suggest that studies employing individual interviews conduct no more than 50 interviews so that researchers are able to manage the complexity of the analytic task. Similarly, Britten [ 40 ] notes that large interview studies will often comprise of 50 to 60 people. Experts have also offered numerical guidelines tailored to different theoretical and methodological traditions and specific research approaches, e.g. grounded theory, phenomenology [ 11 , 41 ]. More recently, a quantitative tool was proposed [ 42 ] to support a priori sample size determination based on estimates of the prevalence of themes in the population. Nevertheless, this more formulaic approach raised criticisms relating to assumptions about the conceptual [ 43 ] and ontological status of ‘themes’ [ 44 ] and the linearity ascribed to the processes of sampling, data collection and data analysis [ 45 ].

In terms of principles, Lincoln and Guba [ 17 ] proposed that sample size determination be guided by the criterion of informational redundancy , that is, sampling can be terminated when no new information is elicited by sampling more units. Following the logic of informational comprehensiveness Malterud et al. [ 18 ] introduced the concept of information power as a pragmatic guiding principle, suggesting that the more information power the sample provides, the smaller the sample size needs to be, and vice versa.

Undoubtedly, the most widely used principle for determining sample size and evaluating its sufficiency is that of saturation . The notion of saturation originates in grounded theory [ 15 ] – a qualitative methodological approach explicitly concerned with empirically-derived theory development – and is inextricably linked to theoretical sampling. Theoretical sampling describes an iterative process of data collection, data analysis and theory development whereby data collection is governed by emerging theory rather than predefined characteristics of the population. Grounded theory saturation (often called theoretical saturation) concerns the theoretical categories – as opposed to data – that are being developed and becomes evident when ‘gathering fresh data no longer sparks new theoretical insights, nor reveals new properties of your core theoretical categories’ [ 46 p. 113]. Saturation in grounded theory, therefore, does not equate to the more common focus on data repetition and moves beyond a singular focus on sample size as the justification of sampling adequacy [ 46 , 47 ]. Sample size in grounded theory cannot be determined a priori as it is contingent on the evolving theoretical categories.

Saturation – often under the terms of ‘data’ or ‘thematic’ saturation – has diffused into several qualitative communities beyond its origins in grounded theory. Alongside the expansion of its meaning, being variously equated with ‘no new data’, ‘no new themes’, and ‘no new codes’, saturation has emerged as the ‘gold standard’ in qualitative inquiry [ 2 , 26 ]. Nevertheless, and as Morse [ 48 ] asserts, whilst saturation is the most frequently invoked ‘guarantee of qualitative rigor’, ‘it is the one we know least about’ (p. 587). Certainly researchers caution that saturation is less applicable to, or appropriate for, particular types of qualitative research (e.g. conversation analysis, [ 49 ]; phenomenological research, [ 50 ]) whilst others reject the concept altogether [ 19 , 51 ].

Methodological studies in this area aim to provide guidance about saturation and develop a practical application of processes that ‘operationalise’ and evidence saturation. Guest, Bunce, and Johnson [ 26 ] analysed 60 interviews and found that saturation of themes was reached by the twelfth interview. They noted that their sample was relatively homogeneous, their research aims focused, so studies of more heterogeneous samples and with a broader scope would be likely to need a larger size to achieve saturation. Extending the enquiry to multi-site, cross-cultural research, Hagaman and Wutich [ 28 ] showed that sample sizes of 20 to 40 interviews were required to achieve data saturation of meta-themes that cut across research sites. In a theory-driven content analysis, Francis et al. [ 25 ] reached data saturation at the 17th interview for all their pre-determined theoretical constructs. The authors further proposed two main principles upon which specification of saturation be based: (a) researchers should a priori specify an initial analysis sample (e.g. 10 interviews) which will be used for the first round of analysis and (b) a stopping criterion , that is, a number of interviews (e.g. 3) that needs to be further conducted, the analysis of which will not yield any new themes or ideas. For greater transparency, Francis et al. [ 25 ] recommend that researchers present cumulative frequency graphs supporting their judgment that saturation was achieved. A comparative method for themes saturation (CoMeTS) has also been suggested [ 23 ] whereby the findings of each new interview are compared with those that have already emerged and if it does not yield any new theme, the ‘saturated terrain’ is assumed to have been established. Because the order in which interviews are analysed can influence saturation thresholds depending on the richness of the data, Constantinou et al. [ 23 ] recommend reordering and re-analysing interviews to confirm saturation. Hennink, Kaiser and Marconi’s [ 29 ] methodological study sheds further light on the problem of specifying and demonstrating saturation. Their analysis of interview data showed that code saturation (i.e. the point at which no additional issues are identified) was achieved at 9 interviews, but meaning saturation (i.e. the point at which no further dimensions, nuances, or insights of issues are identified) required 16–24 interviews. Although breadth can be achieved relatively soon, especially for high-prevalence and concrete codes, depth requires additional data, especially for codes of a more conceptual nature.

Critiquing the concept of saturation, Nelson [ 19 ] proposes five conceptual depth criteria in grounded theory projects to assess the robustness of the developing theory: (a) theoretical concepts should be supported by a wide range of evidence drawn from the data; (b) be demonstrably part of a network of inter-connected concepts; (c) demonstrate subtlety; (d) resonate with existing literature; and (e) can be successfully submitted to tests of external validity.

Other work has sought to examine practices of sample size reporting and sufficiency assessment across a range of disciplinary fields and research domains, from nutrition [ 34 ] and health education [ 32 ], to education and the health sciences [ 22 , 27 ], information systems [ 30 ], organisation and workplace studies [ 33 ], human computer interaction [ 21 ], and accounting studies [ 24 ]. Others investigated PhD qualitative studies [ 31 ] and grounded theory studies [ 35 ]. Incomplete and imprecise sample size reporting is commonly pinpointed by these investigations whilst assessment and justifications of sample size sufficiency are even more sporadic.

Sobal [ 34 ] examined the sample size of qualitative studies published in the Journal of Nutrition Education over a period of 30 years. Studies that employed individual interviews ( n = 30) had an average sample size of 45 individuals and none of these explicitly reported whether their sample size sought and/or attained saturation. A minority of articles discussed how sample-related limitations (with the latter most often concerning the type of sample, rather than the size) limited generalizability. A further systematic analysis [ 32 ] of health education research over 20 years demonstrated that interview-based studies averaged 104 participants (range 2 to 720 interviewees). However, 40% did not report the number of participants. An examination of 83 qualitative interview studies in leading information systems journals [ 30 ] indicated little defence of sample sizes on the basis of recommendations by qualitative methodologists, prior relevant work, or the criterion of saturation. Rather, sample size seemed to correlate with factors such as the journal of publication or the region of study (US vs Europe vs Asia). These results led the authors to call for more rigor in determining and reporting sample size in qualitative information systems research and to recommend optimal sample size ranges for grounded theory (i.e. 20–30 interviews) and single case (i.e. 15–30 interviews) projects.

Similarly, fewer than 10% of articles in organisation and workplace studies provided a sample size justification relating to existing recommendations by methodologists, prior relevant work, or saturation [ 33 ], whilst only 17% of focus groups studies in health-related journals provided an explanation of sample size (i.e. number of focus groups), with saturation being the most frequently invoked argument, followed by published sample size recommendations and practical reasons [ 22 ]. The notion of saturation was also invoked by 11 out of the 51 most highly cited studies that Guetterman [ 27 ] reviewed in the fields of education and health sciences, of which six were grounded theory studies, four phenomenological and one a narrative inquiry. Finally, analysing 641 interview-based articles in accounting, Dai et al. [ 24 ] called for more rigor since a significant minority of studies did not report precise sample size.

Despite increasing attention to rigor in qualitative research (e.g. [ 52 ]) and more extensive methodological and analytical disclosures that seek to validate qualitative work [ 24 ], sample size reporting and sufficiency assessment remain inconsistent and partial, if not absent, across a range of research domains.

Objectives of the present study

The present study sought to enrich existing systematic analyses of the customs and practices of sample size reporting and justification by focusing on qualitative research relating to health. Additionally, this study attempted to expand previous empirical investigations by examining how qualitative sample sizes are characterised and discussed in academic narratives. Qualitative health research is an inter-disciplinary field that due to its affiliation with medical sciences, often faces views and positions reflective of a quantitative ethos. Thus qualitative health research constitutes an emblematic case that may help to unfold underlying philosophical and methodological differences across the scientific community that are crystallised in considerations of sample size. The present research, therefore, incorporates a comparative element on the basis of three different disciplines engaging with qualitative health research: medicine, psychology, and sociology. We chose to focus our analysis on single-per-participant-interview designs as this not only presents a popular and widespread methodological choice in qualitative health research, but also as the method where consideration of sample size – defined as the number of interviewees – is particularly salient.

Study design

A structured search for articles reporting cross-sectional, interview-based qualitative studies was carried out and eligible reports were systematically reviewed and analysed employing both quantitative and qualitative analytic techniques.

We selected journals which (a) follow a peer review process, (b) are considered high quality and influential in their field as reflected in journal metrics, and (c) are receptive to, and publish, qualitative research (Additional File 1 presents the journals’ editorial positions in relation to qualitative research and sample considerations where available). Three health-related journals were chosen, each representing a different disciplinary field; the British Medical Journal (BMJ) representing medicine, the British Journal of Health Psychology (BJHP) representing psychology, and the Sociology of Health & Illness (SHI) representing sociology.

Search strategy to identify studies

Employing the search function of each individual journal, we used the terms ‘interview*’ AND ‘qualitative’ and limited the results to articles published between 1 January 2003 and 22 September 2017 (i.e. a 15-year review period).

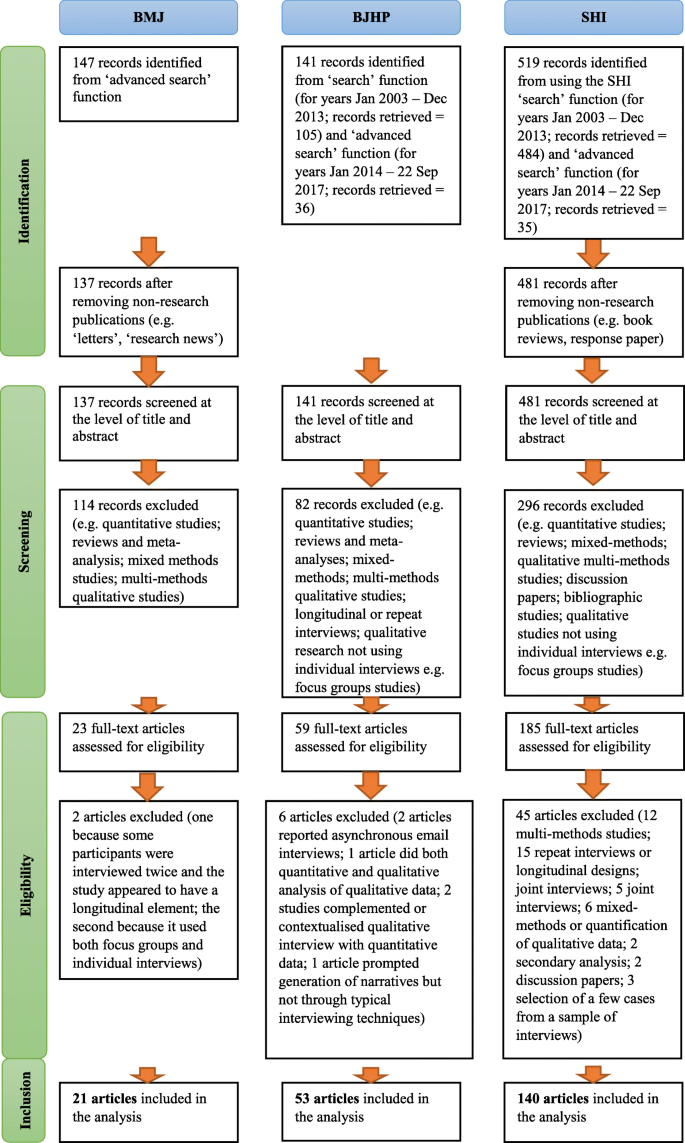

Eligibility criteria

To be eligible for inclusion in the review, the article had to report a cross-sectional study design. Longitudinal studies were thus excluded whilst studies conducted within a broader research programme (e.g. interview studies nested in a trial, as part of a broader ethnography, as part of a longitudinal research) were included if they reported only single-time qualitative interviews. The method of data collection had to be individual, synchronous qualitative interviews (i.e. group interviews, structured interviews and e-mail interviews over a period of time were excluded), and the data had to be analysed qualitatively (i.e. studies that quantified their qualitative data were excluded). Mixed method studies and articles reporting more than one qualitative method of data collection (e.g. individual interviews and focus groups) were excluded. Figure 1 , a PRISMA flow diagram [ 53 ], shows the number of: articles obtained from the searches and screened; papers assessed for eligibility; and articles included in the review (Additional File 2 provides the full list of articles included in the review and their unique identifying code – e.g. BMJ01, BJHP02, SHI03). One review author (KV) assessed the eligibility of all papers identified from the searches. When in doubt, discussions about retaining or excluding articles were held between KV and JB in regular meetings, and decisions were jointly made.

PRISMA flow diagram

Data extraction and analysis

A data extraction form was developed (see Additional File 3 ) recording three areas of information: (a) information about the article (e.g. authors, title, journal, year of publication etc.); (b) information about the aims of the study, the sample size and any justification for this, the participant characteristics, the sampling technique and any sample-related observations or comments made by the authors; and (c) information about the method or technique(s) of data analysis, the number of researchers involved in the analysis, the potential use of software, and any discussion around epistemological considerations. The Abstract, Methods and Discussion (and/or Conclusion) sections of each article were examined by one author (KV) who extracted all the relevant information. This was directly copied from the articles and, when appropriate, comments, notes and initial thoughts were written down.

To examine the kinds of sample size justifications provided by articles, an inductive content analysis [ 54 ] was initially conducted. On the basis of this analysis, the categories that expressed qualitatively different sample size justifications were developed.

We also extracted or coded quantitative data regarding the following aspects:

Journal and year of publication

Number of interviews

Number of participants

Presence of sample size justification(s) (Yes/No)

Presence of a particular sample size justification category (Yes/No), and

Number of sample size justifications provided

Descriptive and inferential statistical analyses were used to explore these data.

A thematic analysis [ 55 ] was then performed on all scientific narratives that discussed or commented on the sample size of the study. These narratives were evident both in papers that justified their sample size and those that did not. To identify these narratives, in addition to the methods sections, the discussion sections of the reviewed articles were also examined and relevant data were extracted and analysed.

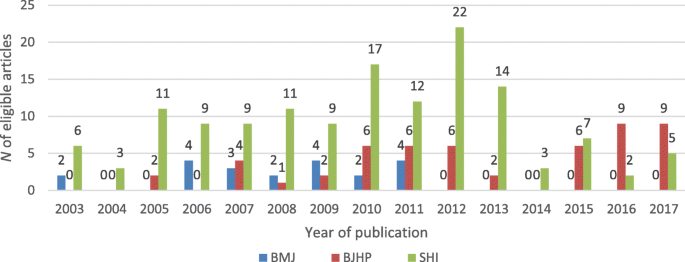

In total, 214 articles – 21 in the BMJ, 53 in the BJHP and 140 in the SHI – were eligible for inclusion in the review. Table 1 provides basic information about the sample sizes – measured in number of interviews – of the studies reviewed across the three journals. Figure 2 depicts the number of eligible articles published each year per journal.

The publication of qualitative studies in the BMJ was significantly reduced from 2012 onwards and this appears to coincide with the initiation of the BMJ Open to which qualitative studies were possibly directed.

Pairwise comparisons following a significant Kruskal-Wallis Footnote 2 test indicated that the studies published in the BJHP had significantly ( p < .001) smaller samples sizes than those published either in the BMJ or the SHI. Sample sizes of BMJ and SHI articles did not differ significantly from each other.

Sample size justifications: Results from the quantitative and qualitative content analysis

Ten (47.6%) of the 21 BMJ studies, 26 (49.1%) of the 53 BJHP papers and 24 (17.1%) of the 140 SHI articles provided some sort of sample size justification. As shown in Table 2 , the majority of articles which justified their sample size provided one justification (70% of articles); fourteen studies (25%) provided two distinct justifications; one study (1.7%) gave three justifications and two studies (3.3%) expressed four distinct justifications.

There was no association between the number of interviews (i.e. sample size) conducted and the provision of a justification (rpb = .054, p = .433). Within journals, Mann-Whitney tests indicated that sample sizes of ‘justifying’ and ‘non-justifying’ articles in the BMJ and SHI did not differ significantly from each other. In the BJHP, ‘justifying’ articles ( Mean rank = 31.3) had significantly larger sample sizes than ‘non-justifying’ studies ( Mean rank = 22.7; U = 237.000, p < .05).

There was a significant association between the journal a paper was published in and the provision of a justification (χ 2 (2) = 23.83, p < .001). BJHP studies provided a sample size justification significantly more often than would be expected ( z = 2.9); SHI studies significantly less often ( z = − 2.4). If an article was published in the BJHP, the odds of providing a justification were 4.8 times higher than if published in the SHI. Similarly if published in the BMJ, the odds of a study justifying its sample size were 4.5 times higher than in the SHI.

The qualitative content analysis of the scientific narratives identified eleven different sample size justifications. These are described below and illustrated with excerpts from relevant articles. By way of a summary, the frequency with which these were deployed across the three journals is indicated in Table 3 .

Saturation was the most commonly invoked principle (55.4% of all justifications) deployed by studies across all three journals to justify the sufficiency of their sample size. In the BMJ, two studies claimed that they achieved data saturation (BMJ17; BMJ18) and one article referred descriptively to achieving saturation without explicitly using the term (BMJ13). Interestingly, BMJ13 included data in the analysis beyond the point of saturation in search of ‘unusual/deviant observations’ and with a view to establishing findings consistency.

Thirty three women were approached to take part in the interview study. Twenty seven agreed and 21 (aged 21–64, median 40) were interviewed before data saturation was reached (one tape failure meant that 20 interviews were available for analysis). (BMJ17). No new topics were identified following analysis of approximately two thirds of the interviews; however, all interviews were coded in order to develop a better understanding of how characteristic the views and reported behaviours were, and also to collect further examples of unusual/deviant observations. (BMJ13).

Two articles reported pre-determining their sample size with a view to achieving data saturation (BMJ08 – see extract in section In line with existing research ; BMJ15 – see extract in section Pragmatic considerations ) without further specifying if this was achieved. One paper claimed theoretical saturation (BMJ06) conceived as being when “no further recurring themes emerging from the analysis” whilst another study argued that although the analytic categories were highly saturated, it was not possible to determine whether theoretical saturation had been achieved (BMJ04). One article (BMJ18) cited a reference to support its position on saturation.

In the BJHP, six articles claimed that they achieved data saturation (BJHP21; BJHP32; BJHP39; BJHP48; BJHP49; BJHP52) and one article stated that, given their sample size and the guidelines for achieving data saturation, it anticipated that saturation would be attained (BJHP50).

Recruitment continued until data saturation was reached, defined as the point at which no new themes emerged. (BJHP48). It has previously been recommended that qualitative studies require a minimum sample size of at least 12 to reach data saturation (Clarke & Braun, 2013; Fugard & Potts, 2014; Guest, Bunce, & Johnson, 2006) Therefore, a sample of 13 was deemed sufficient for the qualitative analysis and scale of this study. (BJHP50).

Two studies argued that they achieved thematic saturation (BJHP28 – see extract in section Sample size guidelines ; BJHP31) and one (BJHP30) article, explicitly concerned with theory development and deploying theoretical sampling, claimed both theoretical and data saturation.

The final sample size was determined by thematic saturation, the point at which new data appears to no longer contribute to the findings due to repetition of themes and comments by participants (Morse, 1995). At this point, data generation was terminated. (BJHP31).

Five studies argued that they achieved (BJHP05; BJHP33; BJHP40; BJHP13 – see extract in section Pragmatic considerations ) or anticipated (BJHP46) saturation without any further specification of the term. BJHP17 referred descriptively to a state of achieved saturation without specifically using the term. Saturation of coding , but not saturation of themes, was claimed to have been reached by one article (BJHP18). Two articles explicitly stated that they did not achieve saturation; instead claiming a level of theme completeness (BJHP27) or that themes being replicated (BJHP53) were arguments for sufficiency of their sample size.

Furthermore, data collection ceased on pragmatic grounds rather than at the point when saturation point was reached. Despite this, although nuances within sub-themes were still emerging towards the end of data analysis, the themes themselves were being replicated indicating a level of completeness. (BJHP27).

Finally, one article criticised and explicitly renounced the notion of data saturation claiming that, on the contrary, the criterion of theoretical sufficiency determined its sample size (BJHP16).

According to the original Grounded Theory texts, data collection should continue until there are no new discoveries ( i.e. , ‘data saturation’; Glaser & Strauss, 1967). However, recent revisions of this process have discussed how it is rare that data collection is an exhaustive process and researchers should rely on how well their data are able to create a sufficient theoretical account or ‘theoretical sufficiency’ (Dey, 1999). For this study, it was decided that theoretical sufficiency would guide recruitment, rather than looking for data saturation. (BJHP16).

Ten out of the 20 BJHP articles that employed the argument of saturation used one or more citations relating to this principle.

In the SHI, one article (SHI01) claimed that it achieved category saturation based on authors’ judgment.

This number was not fixed in advance, but was guided by the sampling strategy and the judgement, based on the analysis of the data, of the point at which ‘category saturation’ was achieved. (SHI01).

Three articles described a state of achieved saturation without using the term or specifying what sort of saturation they had achieved (i.e. data, theoretical, thematic saturation) (SHI04; SHI13; SHI30) whilst another four articles explicitly stated that they achieved saturation (SHI100; SHI125; SHI136; SHI137). Two papers stated that they achieved data saturation (SHI73 – see extract in section Sample size guidelines ; SHI113), two claimed theoretical saturation (SHI78; SHI115) and two referred to achieving thematic saturation (SHI87; SHI139) or to saturated themes (SHI29; SHI50).

Recruitment and analysis ceased once theoretical saturation was reached in the categories described below (Lincoln and Guba 1985). (SHI115). The respondents’ quotes drawn on below were chosen as representative, and illustrate saturated themes. (SHI50).

One article stated that thematic saturation was anticipated with its sample size (SHI94). Briefly referring to the difficulty in pinpointing achievement of theoretical saturation, SHI32 (see extract in section Richness and volume of data ) defended the sufficiency of its sample size on the basis of “the high degree of consensus [that] had begun to emerge among those interviewed”, suggesting that information from interviews was being replicated. Finally, SHI112 (see extract in section Further sampling to check findings consistency ) argued that it achieved saturation of discursive patterns . Seven of the 19 SHI articles cited references to support their position on saturation (see Additional File 4 for the full list of citations used by articles to support their position on saturation across the three journals).

Overall, it is clear that the concept of saturation encompassed a wide range of variants expressed in terms such as saturation, data saturation, thematic saturation, theoretical saturation, category saturation, saturation of coding, saturation of discursive themes, theme completeness. It is noteworthy, however, that although these various claims were sometimes supported with reference to the literature, they were not evidenced in relation to the study at hand.

Pragmatic considerations

The determination of sample size on the basis of pragmatic considerations was the second most frequently invoked argument (9.6% of all justifications) appearing in all three journals. In the BMJ, one article (BMJ15) appealed to pragmatic reasons, relating to time constraints and the difficulty to access certain study populations, to justify the determination of its sample size.

On the basis of the researchers’ previous experience and the literature, [30, 31] we estimated that recruitment of 15–20 patients at each site would achieve data saturation when data from each site were analysed separately. We set a target of seven to 10 caregivers per site because of time constraints and the anticipated difficulty of accessing caregivers at some home based care services. This gave a target sample of 75–100 patients and 35–50 caregivers overall. (BMJ15).

In the BJHP, four articles mentioned pragmatic considerations relating to time or financial constraints (BJHP27 – see extract in section Saturation ; BJHP53), the participant response rate (BJHP13), and the fixed (and thus limited) size of the participant pool from which interviewees were sampled (BJHP18).

We had aimed to continue interviewing until we had reached saturation, a point whereby further data collection would yield no further themes. In practice, the number of individuals volunteering to participate dictated when recruitment into the study ceased (15 young people, 15 parents). Nonetheless, by the last few interviews, significant repetition of concepts was occurring, suggesting ample sampling. (BJHP13).

Finally, three SHI articles explained their sample size with reference to practical aspects: time constraints and project manageability (SHI56), limited availability of respondents and project resources (SHI131), and time constraints (SHI113).

The size of the sample was largely determined by the availability of respondents and resources to complete the study. Its composition reflected, as far as practicable, our interest in how contextual factors (for example, gender relations and ethnicity) mediated the illness experience. (SHI131).

Qualities of the analysis

This sample size justification (8.4% of all justifications) was mainly employed by BJHP articles and referred to an intensive, idiographic and/or latently focused analysis, i.e. that moved beyond description. More specifically, six articles defended their sample size on the basis of an intensive analysis of transcripts and/or the idiographic focus of the study/analysis. Four of these papers (BJHP02; BJHP19; BJHP24; BJHP47) adopted an Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) approach.

The current study employed a sample of 10 in keeping with the aim of exploring each participant’s account (Smith et al. , 1999). (BJHP19).

BJHP47 explicitly renounced the notion of saturation within an IPA approach. The other two BJHP articles conducted thematic analysis (BJHP34; BJHP38). The level of analysis – i.e. latent as opposed to a more superficial descriptive analysis – was also invoked as a justification by BJHP38 alongside the argument of an intensive analysis of individual transcripts

The resulting sample size was at the lower end of the range of sample sizes employed in thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2013). This was in order to enable significant reflection, dialogue, and time on each transcript and was in line with the more latent level of analysis employed, to identify underlying ideas, rather than a more superficial descriptive analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). (BJHP38).

Finally, one BMJ paper (BMJ21) defended its sample size with reference to the complexity of the analytic task.

We stopped recruitment when we reached 30–35 interviews, owing to the depth and duration of interviews, richness of data, and complexity of the analytical task. (BMJ21).

Meet sampling requirements

Meeting sampling requirements (7.2% of all justifications) was another argument employed by two BMJ and four SHI articles to explain their sample size. Achieving maximum variation sampling in terms of specific interviewee characteristics determined and explained the sample size of two BMJ studies (BMJ02; BMJ16 – see extract in section Meet research design requirements ).

Recruitment continued until sampling frame requirements were met for diversity in age, sex, ethnicity, frequency of attendance, and health status. (BMJ02).

Regarding the SHI articles, two papers explained their numbers on the basis of their sampling strategy (SHI01- see extract in section Saturation ; SHI23) whilst sampling requirements that would help attain sample heterogeneity in terms of a particular characteristic of interest was cited by one paper (SHI127).

The combination of matching the recruitment sites for the quantitative research and the additional purposive criteria led to 104 phase 2 interviews (Internet (OLC): 21; Internet (FTF): 20); Gyms (FTF): 23; HIV testing (FTF): 20; HIV treatment (FTF): 20.) (SHI23). Of the fifty interviews conducted, thirty were translated from Spanish into English. These thirty, from which we draw our findings, were chosen for translation based on heterogeneity in depressive symptomology and educational attainment. (SHI127).

Finally, the pre-determination of sample size on the basis of sampling requirements was stated by one article though this was not used to justify the number of interviews (SHI10).

Sample size guidelines

Five BJHP articles (BJHP28; BJHP38 – see extract in section Qualities of the analysis ; BJHP46; BJHP47; BJHP50 – see extract in section Saturation ) and one SHI paper (SHI73) relied on citing existing sample size guidelines or norms within research traditions to determine and subsequently defend their sample size (7.2% of all justifications).

Sample size guidelines suggested a range between 20 and 30 interviews to be adequate (Creswell, 1998). Interviewer and note taker agreed that thematic saturation, the point at which no new concepts emerge from subsequent interviews (Patton, 2002), was achieved following completion of 20 interviews. (BJHP28). Interviewing continued until we deemed data saturation to have been reached (the point at which no new themes were emerging). Researchers have proposed 30 as an approximate or working number of interviews at which one could expect to be reaching theoretical saturation when using a semi-structured interview approach (Morse 2000), although this can vary depending on the heterogeneity of respondents interviewed and complexity of the issues explored. (SHI73).

In line with existing research

Sample sizes of published literature in the area of the subject matter under investigation (3.5% of all justifications) were used by 2 BMJ articles as guidance and a precedent for determining and defending their own sample size (BMJ08; BMJ15 – see extract in section Pragmatic considerations ).

We drew participants from a list of prisoners who were scheduled for release each week, sampling them until we reached the target of 35 cases, with a view to achieving data saturation within the scope of the study and sufficient follow-up interviews and in line with recent studies [8–10]. (BMJ08).

Similarly, BJHP38 (see extract in section Qualities of the analysis ) claimed that its sample size was within the range of sample sizes of published studies that use its analytic approach.

Richness and volume of data

BMJ21 (see extract in section Qualities of the analysis ) and SHI32 referred to the richness, detailed nature, and volume of data collected (2.3% of all justifications) to justify the sufficiency of their sample size.

Although there were more potential interviewees from those contacted by postcode selection, it was decided to stop recruitment after the 10th interview and focus on analysis of this sample. The material collected was considerable and, given the focused nature of the study, extremely detailed. Moreover, a high degree of consensus had begun to emerge among those interviewed, and while it is always difficult to judge at what point ‘theoretical saturation’ has been reached, or how many interviews would be required to uncover exception(s), it was felt the number was sufficient to satisfy the aims of this small in-depth investigation (Strauss and Corbin 1990). (SHI32).

Meet research design requirements

Determination of sample size so that it is in line with, and serves the requirements of, the research design (2.3% of all justifications) that the study adopted was another justification used by 2 BMJ papers (BMJ16; BMJ08 – see extract in section In line with existing research ).

We aimed for diverse, maximum variation samples [20] totalling 80 respondents from different social backgrounds and ethnic groups and those bereaved due to different types of suicide and traumatic death. We could have interviewed a smaller sample at different points in time (a qualitative longitudinal study) but chose instead to seek a broad range of experiences by interviewing those bereaved many years ago and others bereaved more recently; those bereaved in different circumstances and with different relations to the deceased; and people who lived in different parts of the UK; with different support systems and coroners’ procedures (see Tables 1 and 2 for more details). (BMJ16).

Researchers’ previous experience

The researchers’ previous experience (possibly referring to experience with qualitative research) was invoked by BMJ15 (see extract in section Pragmatic considerations ) as a justification for the determination of sample size.

Nature of study

One BJHP paper argued that the sample size was appropriate for the exploratory nature of the study (BJHP38).

A sample of eight participants was deemed appropriate because of the exploratory nature of this research and the focus on identifying underlying ideas about the topic. (BJHP38).

Further sampling to check findings consistency

Finally, SHI112 argued that once it had achieved saturation of discursive patterns, further sampling was decided and conducted to check for consistency of the findings.

Within each of the age-stratified groups, interviews were randomly sampled until saturation of discursive patterns was achieved. This resulted in a sample of 67 interviews. Once this sample had been analysed, one further interview from each age-stratified group was randomly chosen to check for consistency of the findings. Using this approach it was possible to more carefully explore children’s discourse about the ‘I’, agency, relationality and power in the thematic areas, revealing the subtle discursive variations described in this article. (SHI112).

Thematic analysis of passages discussing sample size

This analysis resulted in two overarching thematic areas; the first concerned the variation in the characterisation of sample size sufficiency, and the second related to the perceived threats deriving from sample size insufficiency.

Characterisations of sample size sufficiency

The analysis showed that there were three main characterisations of the sample size in the articles that provided relevant comments and discussion: (a) the vast majority of these qualitative studies ( n = 42) considered their sample size as ‘small’ and this was seen and discussed as a limitation; only two articles viewed their small sample size as desirable and appropriate (b) a minority of articles ( n = 4) proclaimed that their achieved sample size was ‘sufficient’; and (c) finally, a small group of studies ( n = 5) characterised their sample size as ‘large’. Whilst achieving a ‘large’ sample size was sometimes viewed positively because it led to richer results, there were also occasions when a large sample size was problematic rather than desirable.

‘Small’ but why and for whom?

A number of articles which characterised their sample size as ‘small’ did so against an implicit or explicit quantitative framework of reference. Interestingly, three studies that claimed to have achieved data saturation or ‘theoretical sufficiency’ with their sample size, discussed or noted as a limitation in their discussion their ‘small’ sample size, raising the question of why, or for whom, the sample size was considered small given that the qualitative criterion of saturation had been satisfied.

The current study has a number of limitations. The sample size was small (n = 11) and, however, large enough for no new themes to emerge. (BJHP39). The study has two principal limitations. The first of these relates to the small number of respondents who took part in the study. (SHI73).

Other articles appeared to accept and acknowledge that their sample was flawed because of its small size (as well as other compositional ‘deficits’ e.g. non-representativeness, biases, self-selection) or anticipated that they might be criticized for their small sample size. It seemed that the imagined audience – perhaps reviewer or reader – was one inclined to hold the tenets of quantitative research, and certainly one to whom it was important to indicate the recognition that small samples were likely to be problematic. That one’s sample might be thought small was often construed as a limitation couched in a discourse of regret or apology.

Very occasionally, the articulation of the small size as a limitation was explicitly aligned against an espoused positivist framework and quantitative research.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, the 100 incidents sample represents a small number of the total number of serious incidents that occurs every year. 26 We sent out a nationwide invitation and do not know why more people did not volunteer for the study. Our lack of epidemiological knowledge about healthcare incidents, however, means that determining an appropriate sample size continues to be difficult. (BMJ20).

Indicative of an apparent oscillation of qualitative researchers between the different requirements and protocols demarcating the quantitative and qualitative worlds, there were a few instances of articles which briefly recognised their ‘small’ sample size as a limitation, but then defended their study on more qualitative grounds, such as their ability and success at capturing the complexity of experience and delving into the idiographic, and at generating particularly rich data.

This research, while limited in size, has sought to capture some of the complexity attached to men’s attitudes and experiences concerning incomes and material circumstances. (SHI35). Our numbers are small because negotiating access to social networks was slow and labour intensive, but our methods generated exceptionally rich data. (BMJ21). This study could be criticised for using a small and unrepresentative sample. Given that older adults have been ignored in the research concerning suntanning, fair-skinned older adults are the most likely to experience skin cancer, and women privilege appearance over health when it comes to sunbathing practices, our study offers depth and richness of data in a demographic group much in need of research attention. (SHI57).

‘Good enough’ sample sizes

Only four articles expressed some degree of confidence that their achieved sample size was sufficient. For example, SHI139, in line with the justification of thematic saturation that it offered, expressed trust in its sample size sufficiency despite the poor response rate. Similarly, BJHP04, which did not provide a sample size justification, argued that it targeted a larger sample size in order to eventually recruit a sufficient number of interviewees, due to anticipated low response rate.

Twenty-three people with type I diabetes from the target population of 133 ( i.e. 17.3%) consented to participate but four did not then respond to further contacts (total N = 19). The relatively low response rate was anticipated, due to the busy life-styles of young people in the age range, the geographical constraints, and the time required to participate in a semi-structured interview, so a larger target sample allowed a sufficient number of participants to be recruited. (BJHP04).

Two other articles (BJHP35; SHI32) linked the claimed sufficiency to the scope (i.e. ‘small, in-depth investigation’), aims and nature (i.e. ‘exploratory’) of their studies, thus anchoring their numbers to the particular context of their research. Nevertheless, claims of sample size sufficiency were sometimes undermined when they were juxtaposed with an acknowledgement that a larger sample size would be more scientifically productive.

Although our sample size was sufficient for this exploratory study, a more diverse sample including participants with lower socioeconomic status and more ethnic variation would be informative. A larger sample could also ensure inclusion of a more representative range of apps operating on a wider range of platforms. (BJHP35).

‘Large’ sample sizes - Promise or peril?

Three articles (BMJ13; BJHP05; BJHP48) which all provided the justification of saturation, characterised their sample size as ‘large’ and narrated this oversufficiency in positive terms as it allowed richer data and findings and enhanced the potential for generalisation. The type of generalisation aspired to (BJHP48) was not further specified however.

This study used rich data provided by a relatively large sample of expert informants on an important but under-researched topic. (BMJ13). Qualitative research provides a unique opportunity to understand a clinical problem from the patient’s perspective. This study had a large diverse sample, recruited through a range of locations and used in-depth interviews which enhance the richness and generalizability of the results. (BJHP48).

And whilst a ‘large’ sample size was endorsed and valued by some qualitative researchers, within the psychological tradition of IPA, a ‘large’ sample size was counter-normative and therefore needed to be justified. Four BJHP studies, all adopting IPA, expressed the appropriateness or desirability of ‘small’ sample sizes (BJHP41; BJHP45) or hastened to explain why they included a larger than typical sample size (BJHP32; BJHP47). For example, BJHP32 below provides a rationale for how an IPA study can accommodate a large sample size and how this was indeed suitable for the purposes of the particular research. To strengthen the explanation for choosing a non-normative sample size, previous IPA research citing a similar sample size approach is used as a precedent.

Small scale IPA studies allow in-depth analysis which would not be possible with larger samples (Smith et al. , 2009). (BJHP41). Although IPA generally involves intense scrutiny of a small number of transcripts, it was decided to recruit a larger diverse sample as this is the first qualitative study of this population in the United Kingdom (as far as we know) and we wanted to gain an overview. Indeed, Smith, Flowers, and Larkin (2009) agree that IPA is suitable for larger groups. However, the emphasis changes from an in-depth individualistic analysis to one in which common themes from shared experiences of a group of people can be elicited and used to understand the network of relationships between themes that emerge from the interviews. This large-scale format of IPA has been used by other researchers in the field of false-positive research. Baillie, Smith, Hewison, and Mason (2000) conducted an IPA study, with 24 participants, of ultrasound screening for chromosomal abnormality; they found that this larger number of participants enabled them to produce a more refined and cohesive account. (BJHP32).

The IPA articles found in the BJHP were the only instances where a ‘small’ sample size was advocated and a ‘large’ sample size problematized and defended. These IPA studies illustrate that the characterisation of sample size sufficiency can be a function of researchers’ theoretical and epistemological commitments rather than the result of an ‘objective’ sample size assessment.

Threats from sample size insufficiency

As shown above, the majority of articles that commented on their sample size, simultaneously characterized it as small and problematic. On those occasions that authors did not simply cite their ‘small’ sample size as a study limitation but rather continued and provided an account of how and why a small sample size was problematic, two important scientific qualities of the research seemed to be threatened: the generalizability and validity of results.

Generalizability

Those who characterised their sample as ‘small’ connected this to the limited potential for generalization of the results. Other features related to the sample – often some kind of compositional particularity – were also linked to limited potential for generalisation. Though not always explicitly articulated to what form of generalisation the articles referred to (see BJHP09), generalisation was mostly conceived in nomothetic terms, that is, it concerned the potential to draw inferences from the sample to the broader study population (‘representational generalisation’ – see BJHP31) and less often to other populations or cultures.

It must be noted that samples are small and whilst in both groups the majority of those women eligible participated, generalizability cannot be assumed. (BJHP09). The study’s limitations should be acknowledged: Data are presented from interviews with a relatively small group of participants, and thus, the views are not necessarily generalizable to all patients and clinicians. In particular, patients were only recruited from secondary care services where COFP diagnoses are typically confirmed. The sample therefore is unlikely to represent the full spectrum of patients, particularly those who are not referred to, or who have been discharged from dental services. (BJHP31).

Without explicitly using the term generalisation, two SHI articles noted how their ‘small’ sample size imposed limits on ‘the extent that we can extrapolate from these participants’ accounts’ (SHI114) or to the possibility ‘to draw far-reaching conclusions from the results’ (SHI124).

Interestingly, only a minority of articles alluded to, or invoked, a type of generalisation that is aligned with qualitative research, that is, idiographic generalisation (i.e. generalisation that can be made from and about cases [ 5 ]). These articles, all published in the discipline of sociology, defended their findings in terms of the possibility of drawing logical and conceptual inferences to other contexts and of generating understanding that has the potential to advance knowledge, despite their ‘small’ size. One article (SHI139) clearly contrasted nomothetic (statistical) generalisation to idiographic generalisation, arguing that the lack of statistical generalizability does not nullify the ability of qualitative research to still be relevant beyond the sample studied.

Further, these data do not need to be statistically generalisable for us to draw inferences that may advance medicalisation analyses (Charmaz 2014). These data may be seen as an opportunity to generate further hypotheses and are a unique application of the medicalisation framework. (SHI139). Although a small-scale qualitative study related to school counselling, this analysis can be usefully regarded as a case study of the successful utilisation of mental health-related resources by adolescents. As many of the issues explored are of relevance to mental health stigma more generally, it may also provide insights into adult engagement in services. It shows how a sociological analysis, which uses positioning theory to examine how people negotiate, partially accept and simultaneously resist stigmatisation in relation to mental health concerns, can contribute to an elucidation of the social processes and narrative constructions which may maintain as well as bridge the mental health service gap. (SHI103).

Only one article (SHI30) used the term transferability to argue for the potential of wider relevance of the results which was thought to be more the product of the composition of the sample (i.e. diverse sample), rather than the sample size.

The second major concern that arose from a ‘small’ sample size pertained to the internal validity of findings (i.e. here the term is used to denote the ‘truth’ or credibility of research findings). Authors expressed uncertainty about the degree of confidence in particular aspects or patterns of their results, primarily those that concerned some form of differentiation on the basis of relevant participant characteristics.