- Español (Spanish)

HIV Overview

Hiv and aids clinical trials.

- A clinical trial is a research study done to evaluate new medical approaches in people. HIV and AIDS clinical trials help researchers find better ways to prevent, detect, or treat HIV and AIDS.

- Examples of HIV and AIDS clinical trials underway include studies of new HIV medicines, studies of vaccines to prevent or treat HIV, and studies of medicines to treat infections related to HIV and AIDS.

- The benefits and possible risks of participating in an HIV and AIDS clinical trial are explained to study volunteers before they decide whether to participate in a study.

- Use the find a study search feature on ClinicalTrials.gov to find HIV and AIDS studies looking for volunteer participants. Some HIV and AIDS clinical trials enroll only people who have HIV. Other studies enroll people who do not have HIV.

What is a clinical trial?

A clinical trial is a research study that evaluates new medical approaches in people. These approaches include:

- new medicines or new combinations of medicines

- new medical devices or surgical procedures

- new ways to use an existing medicine or device

- new ways to change behaviors to improve health

Clinical trials are conducted in several phases to determine whether new medical approaches are safe and effective in people. Results from a Phase 1 Trial , Phase 2 Trial , and Phase 3 Trial are used to determine whether a new drug should be approved for sale in the United States. Once a new drug is approved, researchers continue to track its safety in a Phase 4 Trial .

Interventional trial and observational trial are two main types of clinical trials.

What is an HIV and AIDS clinical trial?

HIV and AIDS clinical trials help researchers find better ways to prevent, detect, or treat HIV and AIDS. Every HIV medicine was first studied through clinical trials.

Examples of HIV and AIDS clinical trials include:

- studies of new medicines to prevent or treat HIV and AIDS

- studies of vaccines to prevent or treat HIV

- studies of medicines to treat infections related to HIV and AIDS

Can anyone participate in an HIV and AIDS clinical trial?

It depends on the study. Some HIV and AIDS clinical trials enroll only people who have HIV. Other studies include people who do not have HIV.

Participation in an HIV and AIDS clinical trial may also depend on other factors, such as age, gender, HIV treatment history, or other medical conditions.

What are the benefits of participating in an HIV and AIDS clinical trial?

Participating in an HIV and AIDS clinical trial can provide benefits. For example, many people participate in HIV and AIDS clinical trials, because they want to contribute to HIV and AIDS research. They may have HIV or know someone who has HIV.

People with HIV who participate in an HIV and AIDS clinical trial may benefit from new HIV medicines before they are widely available. HIV medicines being studied in clinical trials are called investigational drugs . To learn more, read the HIVinfo What is an Investigational HIV Drug? fact sheet.

Participants in clinical trials can receive regular and careful medical care from a research team that includes doctors and other health professionals. Often the medicines and medical care are free of charge.

Sometimes people get paid for participating in a clinical trial. For example, they may receive money or a gift card. They may be reimbursed for the cost of meals or transportation.

Are HIV and AIDS clinical trials safe?

Researchers try to make HIV and AIDS clinical trials as safe as possible. However, volunteering to participate in a study testing an experimental treatment for HIV can involve risks of varying degrees. Most volunteers do not experience serious side effects; however, potential side effects that may be serious or even life-threatening can occur from the treatment being studied.

Before enrolling in a clinical trial, potential volunteers learn about the study in a process called informed consent . The process includes an explanation of the possible risks and benefits of participating in the study.

Once enrolled in a study, people continue to receive information about the study through the informed consent process.

If a person decides to participate in an HIV and AIDS clinical trial, will their personal information be shared?

The privacy of study volunteers is important to everyone involved in an HIV and AIDS clinical trial. The informed consent process includes an explanation of how a study volunteer’s personal information is protected.

How can one find an HIV and AIDS clinical trial looking for volunteer participants?

There are several ways to find an HIV and AIDS clinical trial looking for volunteer participants.

- Use the find a study search feature on ClinicalTrials.gov to find HIV and AIDS studies looking for volunteer participants.

- Call a Clinical Info health information specialist at 1-800-448-0440 or email [email protected] .

- Join ResearchMatch , which is a free, secure online tool that makes it easier for the public to become involved in clinical trials.

This fact sheet is based on information from the following sources:

From the National Institutes of Health (NIH):

- NIH Clinical Research Trials and You: The Basics

From the National Library of Medicine:

- Learn About Clinical Studies

Also see the HIV Source collection of HIV links and resources.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 01 December 2021

Research priorities for an HIV cure: International AIDS Society Global Scientific Strategy 2021

- Steven G. Deeks 1 ,

- Nancie Archin 2 ,

- Paula Cannon ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0059-354X 3 ,

- Simon Collins 4 ,

- R. Brad Jones 5 ,

- Marein A. W. P. de Jong 6 ,

- Olivier Lambotte 7 ,

- Rosanne Lamplough 8 ,

- Thumbi Ndung’u 9 , 10 , 11 ,

- Jeremy Sugarman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7022-8332 12 ,

- Caroline T. Tiemessen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0991-1690 13 ,

- Linos Vandekerckhove ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8600-1631 14 ,

- Sharon R. Lewin ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0330-8241 15 , 16 , 17 &

The International AIDS Society (IAS) Global Scientific Strategy working group

Nature Medicine volume 27 , pages 2085–2098 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

60k Accesses

136 Citations

193 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Translational research

Despite the success of antiretroviral therapy (ART) for people living with HIV, lifelong treatment is required and there is no cure. HIV can integrate in the host genome and persist for the life span of the infected cell. These latently infected cells are not recognized as foreign because they are largely transcriptionally silent, but contain replication-competent virus that drives resurgence of the infection once ART is stopped. With a combination of immune activators, neutralizing antibodies, and therapeutic vaccines, some nonhuman primate models have been cured, providing optimism for these approaches now being evaluated in human clinical trials. In vivo delivery of gene-editing tools to either target the virus, boost immunity or protect cells from infection, also holds promise for future HIV cure strategies. In this Review, we discuss advances related to HIV cure in the last 5 years, highlight remaining knowledge gaps and identify priority areas for research for the next 5 years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Prevention, treatment and cure of HIV infection

CD8+ T cells in HIV control, cure and prevention

Therapeutic vaccination following early antiretroviral therapy elicits highly functional T cell responses against conserved HIV-1 regions

Modern antiretroviral regimens can effectively block HIV replication in people with HIV for decades, but these therapies are not curative and must be taken for life. However, there is evidence that a cure can be achieved; initially, this came from a single case study (Timothy Brown, a man living with HIV who became widely known as the ‘Berlin patient’) following bone-marrow transplantation from a donor who was naturally resistant to HIV 1 . On the basis of this inspiring development and the recognition that not everyone can access and/or adhere indefinitely to antiretroviral therapy (ART), a global consensus emerged approximately 10 years ago that a curative intervention was a high priority for people with HIV and would be necessary to bring an end to the HIV pandemic. Since then, there has been a second case report of a cure following bone-marrow transplantation 2 as well as evidence of persistence of only defective forms of the virus in certain patients 3 and enhanced immune control of the virus by others after only a short time on ART 4 —further supporting the notion that a cure for HIV can be achieved.

An HIV cure includes both remission and eradication. Here, we define the term remission as durable control of virus in the absence of any ongoing ART. Eradication is the complete removal of intact and rebound-competent virus. The minimal and optimal criteria for an acceptable target product profile for an HIV cure, including the duration and level of virus control off ART, has recently been developed and published by the International AIDS Society (IAS), following wide consultation with multiple stakeholders 5 .

In 2011 and 2016, the IAS convened expert working groups to outline a strategy for developing an effective and scalable cure 6 , 7 . Since then, significant progress has been made, and the overall agenda has evolved. Here, we assembled a group of experts from academia, industry, and the community (Box 1 ) to evaluate recent progress and to outline cure-related research priorities for the next 5 years. The key recommendations for each component of the strategy are summarized in Box 2 .

Box 1 The Global Cure Strategy—forming a consensus

The Global Cure Strategy was created using a full online process during the COVID-19 pandemic from November 2020 to August 2021. The co-chairs of the initiative identified the major topics which were divided into eight subthemes, each with its own working group, which included a chair, three scientific experts, at least one community member, an IAS Research-for-Cure fellow, and an industry representative. Working groups met at least twice virtually to generate a summary of key advances and recommendations for the next five years. The steering committee consisted of the chairs of each working group, the co-chairs of the cure strategy and a community expert, selected for diversity in geographic background, gender, age, and expertise. We engaged people living with HIV at all levels as well as a wide range of scientific and nonscientific stakeholders.

The Global Cure Strategy was further refined through a broad, online stakeholder consultation, including an online survey, a review by key stakeholders in the field, and interviews with select experts and opinion leaders (more than 25 respondents). The survey received 162 responses, primarily from people working in academia, nongovernmental organizations, and hospitals or research institutions; 11% of respondents were from organizations of people living with HIV, and 4% were from industry. The majority of respondents were working in Africa, followed by Western and Central Europe, North America, and Central and South America. The summary and detailed responses can be found here: https://www.surveymonkey.com/results/SM-7YYFTZ599/.

Box 2 Key research goals to be addressed in the next 5 years

Understanding hiv reservoirs.

Define and characterize the sources of the replication- and rebound-competent viruses during ART

Define the phenotype of cells harboring intact HIV genomes

Define the clinical significance of defective yet inducible proviruses

Define the mechanisms of clonal proliferation

Determine if infected cells that persist on ART are resistant to cell death

Define the impact of sex and other factors on the reservoir and virus-specific therapies

HIV reservoir measurement

Develop and validate a high-throughput assay to quantify the rebound-competent reservoir

Develop assays that quantify integration sites

Develop assays that account for key qualitative differences in viral transcripts

Develop methods to quantify HIV protein expression in cells and tissues

Develop imaging modalities that quantify the size, distribution, and activity of the reservoir in tissues

Define the link between the cellular reservoirs, residual plasma viremia, and the rebounding virus

Develop assays for point-of-care and eventually at-home viral-load monitoring

Mechanisms of virus control

Identify the mechanisms that contribute to SIV/HIV control

Define the role of HIV-specific antibodies, B cells, and the innate immune response in virus elimination or control

Define the viral dynamics and biomarkers associated with post-treatment control

Optimize human organoid models, as well as mouse and nonhuman primate models, for cure- and remission-related studies

Targeting the provirus

Develop improved strategies to reverse latency

Develop strategies to permanently silence the provirus

Determine the impact of targeting the provirus at the time of initiation of ART

Define the role of viral subtype on the effectiveness of interventions that target the provirus

Targeting the immune system

Develop ‘reduce and control’ approaches

Develop immune modulators

Conduct clinical trials to determine whether combination immunotherapies will result in safe and durable HIV remission

Cell and gene therapy

Define the level of antigen expression needed to enable recognition of infected cells by immunotherapies

Develop gene-editing strategies that target the provirus

Develop strategies for sustained production in vivo of antiviral antibodies

Leverage advances in other biomedical fields to develop safer and more scalable approaches

Pediatric remission and cure

Characterize the establishment, persistence, and potential for preventing or reversing HIV latency in infants and children on ART

Develop assays to monitor and identify biomarkers to predict the efficacy of HIV-1 cure therapeutics

Test HIV immunotherapies and other strategies in infants and children

Social, behavioral, and ethical aspects of cure

Expand community/stakeholder engagement and capacity building

Develop HIV cure research with equity, representation, and scalability considerations

Establish standards for the safe conduct of clinical research

Integrate social, behavioral, and ethics research as part of HIV cure trials

Build capacity for basic discovery research and clinical trials in high-burden, resource-limited settings

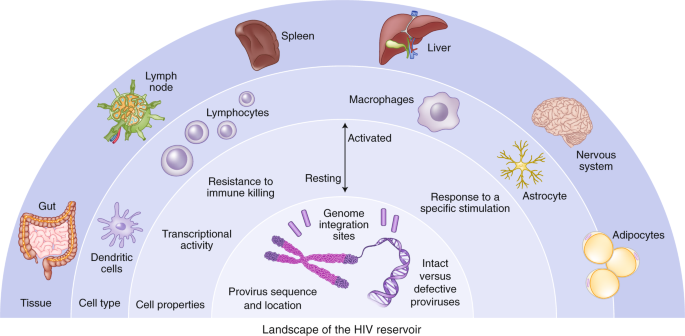

A shared definition of the HIV reservoir is crucial for researchers, clinicians, and people living with HIV. Here, we use the term ‘HIV reservoir’ in the context of eradication or remission, as a representative term for all cells infected with replication-competent HIV in both the blood and different anatomical sites in individuals on ART—in other words, all potential sources of viral rebound in the context of a treatment interruption. Although the source of virus rebound is still not entirely understood, we now know that virus can persist in multiple forms, in multiple cells and in multiple sites.

Characterization of the complete HIV reservoir

HIV DNA can be detected in CD4 + T cells in blood and lymphoid tissue in nearly all people with HIV on ART. These viral genomes are mainly defective. Only a small proportion (less than 5%) appear to be intact and potentially replication-competent 8 . But the HIV reservoir goes beyond circulating CD4 + T cells; it also includes tissue-resident CD4 + T cells and cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage, further complicating efforts to characterize and quantify it. In vitro, HIV preferentially integrates into transcriptionally active genes 9 ; however, in people with HIV on ART, many proviruses (defined as virus that is integrated into the host genome), including intact ones, have been identified in genomic regions that are silent (known as ‘gene deserts’), which limits or precludes their reactivation 3 .

Our initial conception of the HIV reservoir as a static viral archive has given way to a more dynamic view in which, over time on ART, certain within-host HIV variants are gradually eliminated while others persist through various mechanisms, including clonal expansion of infected cells 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 . Sporadic infection of new cells during ART has been reported 16 , although there has been no convincing demonstration that viral sequences evolve during effective ART 17 , suggesting that the degree of virus spread is minimal. The sources of viral rebound following cessation of ART are incompletely defined. Multiple factors can contribute to viral replication following ART, including anatomical and microanatomical locations, the infected cell type, cellular phenotype, the nature of the provirus, the antigen specificity of the infected cell, the potential for transcriptional activity given the specific integration site, and/or distribution of antiretroviral drugs within tissues (Fig. 1 ).

The HIV reservoir can be defined across a number of dimensions, including: (1) anatomical and microanatomical locations, (2) cell type (for example, CD4 + T cell or macrophage), (3) cell functional profile (activated or resting; resistance to killing), (4) pool of proviruses with a particular functional profile (for example, interferon-alpha resistant) or (5) triggering event (for example, response to stimulation with a particular antigen), and (6) integration-site features of the rebounding virus.

We recommend prioritizing efforts to understand integration sites of the virus during long-term ART and to understand the inducibility of a provirus on the basis of its chromosomal context. In addition, large prospective studies incorporating analytical treatment interruptions (ATIs) are still needed to probe clinically relevant sources of viral rebound and to identify a biomarker that predicts this. A favorable cure intervention could either prolong the time to the point when virus is detectable (that is, rebound) in plasma or reduce the viral ‘set point’ (that is, post-treatment control).

One of the most daunting obstacles to designing more effective methods to target persistent HIV infection is the lack of biomarkers to unambiguously identify the cells that harbor the rebound-competent reservoir. Recent work has demonstrated that the viral reservoir is preferentially enriched in cells that express programmed death-1 (PD-1) and other immune checkpoint markers, activation markers such as HLA-DR, and chemokine receptors such as CCR6 and CXCR3, but there is no phenotypic marker specific for the reservoir 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 . Specific biomarkers of the reservoir are needed, particularly to assess the impact of cure interventions. Furthermore, understanding how HIV persists in specific tissue sites and relevant local cell populations, such as those in the brain, gastrointestinal tract liver, or genital tract, will be important, given that the mechanism for persistence in each site may be distinct, and therefore different approaches may be required to eliminate each of these reservoirs.

There is growing evidence that some defective proviruses can produce transcripts and proteins (including novel viral RNAs and chimeric viral proteins) that in turn can elicit immune responses and perhaps contribute to chronic inflammation 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 . This may be of high relevance to end organ complications, such as HIV-associated neurological disease 26 . If the production of RNA and proteins from these defective proviruses proves to have clinical relevance, then their removal may be necessary to ensure long-term health.

A major mechanism of HIV persistence is the proliferation of cells that were infected prior to ART, resulting in large clonal populations of infected cells that arise as a result of the site of HIV integration 27 , 28 , response to antigen 29 , 30 , or homeostatic drivers 31 . Characterization of these presumably physiological expansions might lead to the development of therapies aimed at interrupting proliferation of infected cells. It will be important to determine to what degree these expanded clones are transcriptionally active, whether they are an important of post-ART viral rebound, and whether they have some innate survival advantage that prevents the cells from being effectively cleared by the host.

Recent studies have provided some evidence for preferential survival of infected cells with proliferative advantages or with deeper viral latency. Prosurvival and immune-resistance profiles may be particularly important in infected cells that persist despite expression of viral RNA or proteins 32 , 33 , 34 . Opportunities likely exist for collaboration and cross-fertilization of concepts with the cancer field, where the clonal dynamics of tumors have been extensively studied in relation to prosurvival and immune-resistance advantages, such as the work being done on lung cancer through prospective genetic studies in TRACRx ( https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01888601 ).

Biological sex can influence HIV pathogenesis, the immune response to HIV infection, and response to antiviral therapy 35 . Furthermore, in some but not all studies, women’s reservoirs have been shown to be less transcriptionally active and less inducible than those of men 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 . Sex, therefore, is a critical variable that should be considered as new therapies to target the reservoir are developed.

Quantification of the HIV reservoir

Significant progress toward a cure for HIV depends on having sensitive, specific, and quantitative measures of persistent virus that can be applied to various anatomical compartments 41 . Achieving this has been challenging, however, owing to the many sources and heterogeneous properties of persistent, replication-competent HIV. The reservoir can be quantified using assays that measure viral nucleic acid (total and integrated DNA, intact and defective DNA, or different forms of RNA), virus protein (p24), or viral inducibility (by measuring HIV RNA or virus replication following activation in vitro). Each approach has advantages and limitations, and assay outcomes may not always be interchangeable, comparable, or even correlated 8 .

Several groups have developed droplet digital PCR-based assays that discriminate genetically intact proviruses from a large background of defective proviruses, which are slightly less accurate but more high throughput than full genome sequencing 42 , 43 . The application of these assays to large clinical cohorts has demonstrated that there is a modest decrease in the frequency of cells with intact provirus over years on ART 44 , 45 , 46 . These assays have largely been optimized for subtype B virus, the major HIV subtype found in the United States and Europe. Yet there are over ten subtypes worldwide, some of which have evolved different mechanisms for immune evasion and persistence 47 . Pan-subtype-specific assays will need to be developed, and challenges related to cost and scalability remain. Research in this field should ideally culminate in harmonization across laboratories and crossvalidation of results. Future work will need to expand from quantification of virus in blood to quantification in tissue, particularly the more accessible tissues such as lymph nodes and gut mucosa.

Understanding the proviral landscape (defined as the degree of intactness, its transcriptional activity, and its location) is crucial, as these characteristics almost certainly influence the degree to which a provirus will rebound 48 . Over the last decade, several assays have been developed to analyze the exact location at which the virus integrates and whether the integrated virus is intact or defective. The ability to analyze single cells for integration site, viral sequence, and transcription is a major advance 48 ; however, these assays are expensive and low throughput. Technological advances are required to apply this more broadly to clinical samples, including assessment of interventions that target the reservoir.

Cell-associated viral RNA (CA-RNA) provides a measure of the total transcriptional activity of proviruses within a given sample. Several assays have recently been developed that quantify different RNA species, including total, elongated, unspliced, polyadenylated, and multi-spliced RNA, and these stand to give higher-resolution insights into the impact of therapeutic intervention 49 . An important unmet need is to develop approaches to distinguish transcripts arising from defective versus intact proviruses. Another shortcoming hampering broad use of RNA assays is the fact that they are subtype-sensitive. Overall, our ability to study the biology of transcriptionally active proviruses and the role of transcriptional activity as a potential biomarker needs to be further explored.

Since HIV protein expression is also required for recognition by HIV-specific T cells and other immune-based therapies, measuring and characterizing viral proteins in cells and tissues is an important step to understanding HIV persistence and might prove to be a critical determinant for the efficacy of therapies that target the HIV-infected cells directly (for example, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells or broadly neutralizing antibodies). Quantification of the p24 protein with ultrasensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays can determine the efficacy of therapies that target the reservoir directly. Ultrasensitive p24 assays have emerged as useful tools 25 , but drawbacks include low levels of sensitivity compared with nucleic acid detection, overestimation of the replication-competent reservoir, and the requirement for specialized instrumentation 25 , 50 . Detection of viral envelope protein (the target of many therapeutic interventions for an HIV cure) also remains a challenge. Future strategies should leverage advances in single-cell techniques and new approaches to imaging tissue using super-resolution or expansion microscopy, together with multi-omics approaches.

Substantial progress in other fields of medicine has been made in using advanced imaging techniques to quantify rare diseased cells in tissues. On the basis of some preliminary success in nonhuman primate models 51 , efforts to use radiolabeled HIV-specific tracers and sensitive imaging modalities (for example, positron emission tomography, PET) have been initiated 52 . Similar efforts aimed at characterizing sites of inflammation or expression of specific surface markers that are associated with HIV persistence should also be a priority.

Several studies have attempted to identify sources of rebound virus by probing phylogenetic linkages with the proviral sequences present in various anatomical and cellular compartments. Success has been limited, however, in part owing to the challenging nature of obtaining full-length sequences from the limited number of infected cells in blood or tissue, as well as from plasma with low level viremia 53 . Strategies that can enhance enrichment of infected cells and/or depth of viral sequencing together with high-throughput low-cost single-cell analyses are likely to advance the field. As the RNA in circulating virions is a well-accepted surrogate marker for untreated HIV disease, this measurement could be an effective tool to characterize the rebound-competent population of HIV-infected cells.

Currently, any impact of a therapeutic intervention on the viral reservoir can only be determined with an ATI. A tool for very early detection of viral rebound post-ART using a nonvirological marker—such as measures of the innate immune response 54 —could be very valuable. In addition, better ways to monitor viral load that do not require frequent healthcare appointments will be needed 5 . This should include the development of home-based tests that may not necessarily require high sensitivity as long as testing is performed frequently 55 . Finally, emerging evidence suggests that virus replication during an ATI may be associated with some long-term adverse events 56 , so careful follow up of participants in ATI studies will be necessary.

Mechanisms and models of virus control

Natural control in people living with hiv.

Individuals who naturally control HIV in the absence of any therapy and can maintain a viral load of <50 copies/ml (known as ‘elite’ controllers) have been the focus of intense investigation for years. Research in this area is increasingly focused on those controllers who exhibit remarkably stringent control (‘exceptional’ controllers) 57 , 58 , some of whom might be considered true cures 48 , 59 , and those who became controllers after ART interruption (post-treatment controllers) 60 , 61 . In exceptional controllers, the frequency of infected cells is extremely low, often below the limit of detection of most standard assays for HIV DNA 57 , 59 , there is no intact virus 48 and the site of HIV integration may be distinct 48 ; an agreed definition for an exceptional controller is needed.

Virus-specific CD8 + T cells targeting particularly vulnerable or conserved epitopes are generally recognized as the key mediator of elite control; such cells are rare in post-treatment controllers and have not yet been characterized in exceptional controllers 4 , 62 . Further characterization of the various controller phenotypes (elite, exceptional, post-treatment) should remain a priority; the identification of unique and potentially informative phenotypes should also be pursued, including individuals on ART who have very small reservoirs 62 . Functional multi-omics studies and emerging single-cell technologies should help to determine the mechanisms involved in exceptional, elite, and post-treatment control. Better animal models of exceptional and post-treatment control would greatly enhance the field, giving access to tissue and the opportunity for longitudinal assessment of virus control 63 .

Virus elimination and control will likely require a coordinated immune response involving more than just T cells. Recent data suggest that autologous antibodies targeting archived viruses as well as interferon sensitivity might influence which virus populations emerge post-ART 54 , 64 , 65 . Studies in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected nonhuman primates that naturally control infection have provided indirect evidence that natural killer (NK) cells might be able to effectively control virus in tissues 66 . Better insights into the role of antibodies, natural killer cells, and innate immunity in post-treatment and/or post-intervention control are needed.

The interplay between the virus and immune system during acute infection or immediately after the interruption of ART is largely unknown, at least in humans. During acute infection, those destined to become controllers typically have an initial period of poorly controlled viremia 61 , 67 . For post-treatment controllers, virus control is often achieved more rapidly after cessation of ART than after primary infection 61 , 68 . We need to understand the viral dynamics associated with eventual post-ART control/remission, as this will inform how a treatment interruption should be conducted. It is likely that biomarkers other than the plasma HIV RNA level might allow for the development of safer and more cost-effective strategies for interrupting ART.

Animal models of control

The role of humanized mouse models in cure research is still evolving. Recent studies showing similar effects of latency-reversing strategies in mice and the less scalable nonhuman primate model are encouraging 69 , 70 . Given that access to nonhuman primates for cure studies will likely remain a barrier, ongoing optimization, standardization, and validation of mouse models should be prioritized.

An important discrepancy in translating cure-related findings from SIV-infected nonhuman primates to people with HIV lies in the duration of ART. Although effective ART regimens with integrase inhibitors have been optimized in nonhuman primates, high costs, and treatment-related toxicities necessitate relatively shorter study durations (less than 1–2 years of ART). One possible solution would be for primate research centers to maintain colonies of SIV-infected nonhuman primates receiving very-long-term ART to be directly assigned for studies.

There is ongoing debate about the most appropriate virus to be used in cure-related studies in nonhuman primates. Investigations utilizing broadly neutralizing antibodies or select vaccines directed against the HIV-1 envelope necessitate infection with a virus that expresses HIV envelope proteins (simian-human immunodeficiency virus, SHIV). However, SHIV infections with some strains are characterized by post-treatment control in the absence of any intervention 71 , while others can induce significant disease progression 72 . Therefore, the specific strain used can limit the generalizability of the model. Although SIV infection of nonhuman primates can cause more significant disease progression than HIV infection of people, early ART for SIV infection can limit rapid disease progression and is therefore a useful model for cure studies 73 . Developing immunotherapies that target the SIV envelope in addition to SHIV should also be pursued.

A major recent advance has been the development of genetically barcoded SIV mac239 strains 74 . Because the barcode ‘tags’ are easily quantified and also passed on to progeny virus, this model allows for tracking of clonal dynamics, providing more precise insights into how interventions affect seeding of the reservoir, viral reactivation during ART, or viral recrudescence after ART interruption.

Therapeutic interventions

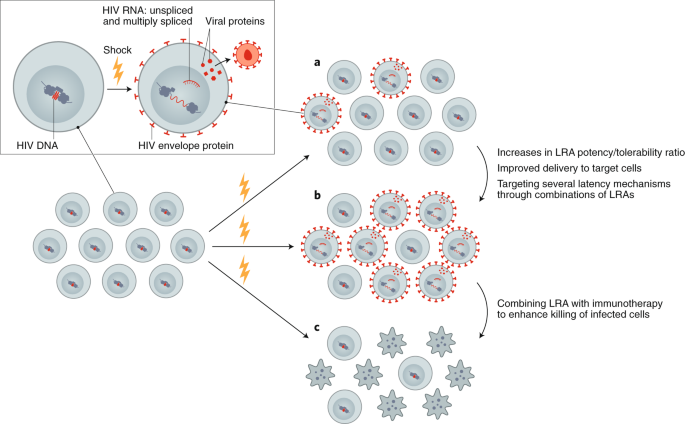

Since the discovery that HIV can establish a latent infection with minimal HIV transcription, a range of approaches has emerged that specifically target latently infected cells. These include pharmacological modulation of epigenetic or signaling pathways involved in HIV transcription to reactivate latent HIV such that the cells can be targeted and eliminated (‘shock and kill’) or to permanently silence HIV transcription (‘block and lock’) 75 , 76 , 77 . Recent reports have demonstrated that HIV latency is heterogeneous and that latency reactivation is stochastic, implying that a combination of agents targeting various pathways controlling HIV transcription may be necessary to achieve either robust silencing or latency reversal 49 , 78 , 79 , 80 .

A clear limitation of the ‘shock and kill’ approach comes from the discovery that only a fraction of proviruses is intact and among these, only some are inducible by a potent stimulus such as T cell stimulation, let alone by far less potent latency-reversing agents (LRAs) 8 , 81 , 82 , 83 . Furthermore, cells containing reactivated latent HIV may also be relatively resistant to killing by cytotoxic T cells 84 . Complicating the situation even more, CD8 + T cells appear to suppress HIV transcription and can blunt the effect of LRAs 70 .

Although LRAs tested in humans can induce HIV RNA expression and virion production in vivo, they have failed to reduce the size of the reservoir, even when combined with immunotherapeutic strategies designed to enhance clearance of infected cells 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 . This could be due to poor antigen induction by LRAs or insufficient clearance of these targets by immunotherapies (Fig. 2 ). Furthermore, many of the tested LRAs have off-target effects. Newer approaches for delivery of LRAs to reduce toxicity, enhance potency, and improve targeting, potentially leveraging advances in nanomedicine, should be explored. Greater potency could potentially be achieved using LRAs in combination, however, care is needed in these clinical trials, given that unexpected toxicities can emerge—as was recently demonstrated in the evaluation of high-dose disulfiram and vorinostat 91 . Finally, LRAs will likely need to be partnered with therapies that enhance the clearance of cells expressing viral proteins, such as immune-enhancing strategies or proapoptotic drugs 92 .

Reversing latency is an important component of revealing HIV-infected cells, allowing for conversion of a latently infected to a productively infected cell. a , Currently available LRAs reverse latency in only a subset of infected cells, and, when used alone, do not sufficiently eliminate these. b , Enhancing the efficacy of an LRA can be achieved with increased potency, targeted delivery or through using combinations of LRAs. c , Ultimately, depletion of the reservoir will require combining an LRA with other interventions, such as immunotherapy or a proapoptotic drug.

Permanently silencing the HIV promoter by suppressing factors that promote HIV transcription has also emerged as a strategy to target the provirus. The concept is to therapeutically drive HIV into a permanently silenced epigenetic state that resists reactivation (‘deep latency’). The Tat inhibitor didehydro-cortistatin A (dCA) blocks HIV reactivation from human CD4 + T cells in vitro through epigenetic repression; treatment with dCA in ART-suppressed humanized mouse latency models induces a measurable delay in virus rebound 76 , 93 . Gene therapy can also play an important part in permanent silencing of the provirus using short interfering RNA or other modalities 94 . Thus far, these approaches have yet to be successfully translated into human trials.

Further exploration of the therapeutic potential of permanently silencing the reservoir (‘block and lock’), presumably as part of a combinatorial cure approach, is a high research priority. Some pathways that might be targeted include mTOR, HSF1, and others 95 , 96 , 97 . Efforts to screen for drugs that suppress HIV transcription are encouraged, 96 , 98 , 99 with the goal to rapidly move into preclinical and clinical studies 100 , 101 .

With a recent report indicating that the HIV reservoir is stabilized at the start of ART initiation, efforts should be devised to inhibit this stabilizing effect and/or to enhance reservoir turnover during ART, where such interventions are ideally delivered at ART initiation 102 , 103 , 104 .

Most methods to target the provirus have been developed using subtype B. Thus, while conserved mechanisms govern latency across the different virus subtypes, differences at the level of the promoter may impact responsiveness to various stimuli. Therapies targeting the provirus should be evaluated across multiple HIV subtypes including recombinants.

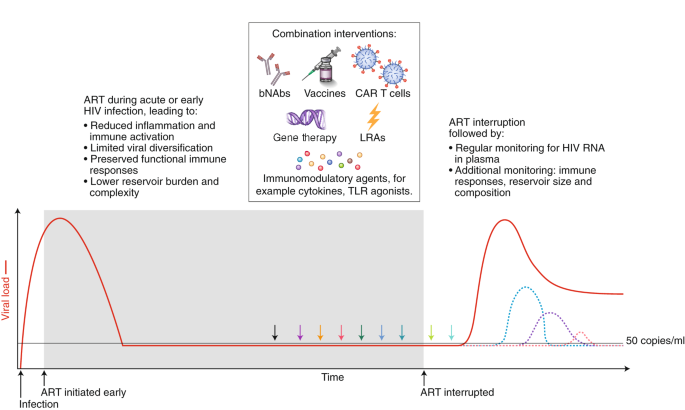

There is a robust and growing toolbox of immune therapies that might be advanced to proof-of-concept testing. Arguably, the most impactful innovation to date is the isolation and development of broadly neutralizing antibodies for clinical use, but advances have also been made in the development of therapeutic vaccines, vaccine adjuvants, and other immunotherapies. When used in combination in nonhuman primates, these immune therapies have resulted in sustained post-ART control 71 , 105 . When used alone, most of these approaches have had limited effectiveness in people, although some promising results are emerging 88 , 106 , 107 . Combination clinical trials have recently started and are ongoing. Although the combination of either vorinostat or romidepsin (HDAC inhibitors that can increase viral transcription through epigenetic modification) together with different HIV vaccines showed no or minimal reduction in the HIV reservoir 107 , 108 , 109 , results from other studies including a combination of Toll-like receptor agonists, LRAs and broadly neutralizing antibodies are eagerly awaited ( NCT03837756 ; NCT04319367 ; NCT03041012 ).

As it may be challenging to reactivate and eliminate all latently infected cells, or to induce deep irreversible latency in all cells, it seems unlikely that these approaches will be curative by themselves. By reducing the reservoir, however, they might make strategies aimed at controlling the virus long term post-ART more effective. This overall approach of 'reduce and control’ is supported by observations in elite and post-treatment controllers, and theoretical modeling 110 . Multiple approaches that might result in control of a small reservoir are being developed. Assessment of therapeutic vaccines including live vector vaccines such as adenovirus 26, modified vaccine Ankara, and also a cytomegalovirus in nonhuman primate models have been particularly promising, with a subset of animals achieving eradication of virus 71 , 111 . Such studies have not yet been performed in people. Research to develop and test novel immunogen and vaccine designs with broad, potent and durable immunity should be prioritized. Given the recognition that autologous neutralizing antibodies might contribute to reservoir control 64 , novel vaccine approaches aimed at the induction of broadly neutralizing antibodies—including germline targeting 112 —should also be prioritized.

Immune stimulators, immunomodulators, and novel immunotherapies (such as cytokine formulations, Toll-like receptor agonists, immune checkpoint inhibitors or agonists, and novel vaccine adjuvants), used alone or more likely in combination with other approaches, hold promise but have undergone relatively limited testing in HIV-cure studies in people so far 106 , 113 , 114 , 115 .

With the exception of a few anecdotal cases 116 , immunotherapy in people with HIV has yet to recapitulate the promising advances made in nonhuman primates. Combination of various therapies will almost certainly be needed (Fig. 3 ). Conducting such studies is feasible 108 , 117 ; it is expected that initial clinical research will be intensive in nature and designed to identify strategies that might then be tested in well-powered, controlled clinical trials. Defining the mechanisms and potential biomarkers associated with remissions/cures in the preclinical and clinical setting should remain a priority. Determining which combinations to study, and how to define the optimal doses and strategies, poses a significant challenge from a methodological and regulatory perspective. As immunotherapies for HIV move into the clinic, careful attention will have to be paid to immune-related adverse events, including cytokine-release syndrome and autoimmunity.

Strategies that will enhance immune-mediated clearance of latently infected cells include early initiation of ART and the administration of combined interventions at the time of suppressive ART (colored arrows) or during the treatment interruption phase, which will allow for increased antigen presentation. Given that there is no biomarker that can predict viral rebound, analytical treatment interruptions are used to determine whether the intervention has had a clinically meaningful impact. The overarching goal is to either delay viral rebound by at least months or years or reduce the set point of virus replication (that is, the stable level of viral load that the body settles at), preferably to a level of <200 copies/ml. The dashed colored lines represent different potential favorable outcomes from a cure intervention. bNAbs, broadly neutralizing antibodies; LRA, latency reversing agent; TLR, Toll-like receptor.

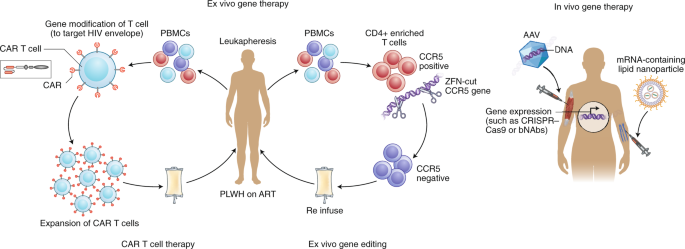

Cell and gene therapy clinical trials for people with HIV, although safe so far, have been small in scale and with no clear demonstrations of efficacy. The interest in gene therapy for an HIV cure was inspired by the elimination of intact virus in Timothy Brown (also known as the Berlin patient) and Adam Casteljo (also known as the London patient), who both received stem-cell transplants from a CCR5-negative donor 1 , 2 to treat their underlying malignancies. CCR5 is a co-receptor that is needed by most strains of HIV to enter a cell; a reduction in the size of the reservoir has also been reported following stem-cell transplantation to people with HIV from donors who are CCR5-positive 118 , 119 , but the HIV reservoir can’t be completely eliminated, irrespective of the CCR5 status of the donor. In the case of CCR5-negative stem-cell transplantation, the absence of CCR5 in the donor cells is thought to protect the newly transplanted cells from infection, at least with CCR5-dependent HIV strains. Interestingly, in both cases of cure following stem-cell transplantation of CCR5-negative cells, defective virus has been detected, but not intact or replication-competent virus 120 , 121 . These reports have prompted researchers to evaluate CCR5-targeted gene editing as a potentially safer path to cure in people living with HIV on ART, given the high mortality rate and significant morbidity associated with stem-cell transplantation. Timothy Brown unfortunately died in early 2020 owing to recurrence of his leukemia, but remained HIV-free until his death.

Ex vivo gene editing of CCR5 using zinc finger nucleases and re-infusion of CCR5-modified T cells has not yet prevented viral rebound following ATI 122 , 123 , possibly because insufficient cell numbers were engineered and/or engrafted with first-generation editing tools and cell culture protocols and/or because CCR5 disruption alone cannot shift the balance in favor of post-treatment control in the presence of persistently infected cells. More recently, gene therapies have shifted to creating effectors, including chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells, which can recognize and eliminate HIV-infected cells (Fig. 4 ). Other approaches include the use of novel delivery systems to deliver genes to local tissues, resulting in the sustained production of systemically acting antivirals such as broadly neutralizing antibodies 124 , 125 and CD4 mimetics 126 . Finally, attempts are being made to directly target integrated proviruses with technologies such as CRISPR–Cas9 and recombinases 127 , 128 . This approach remains conceptually challenging in view of the disparate locations of latently infected cells, the absence of specific markers to target delivery, the heterogeneity of proviral sequences (the majority of which are defective), and the risk of off-target effects.

Examples of ex vivo (left) and in vivo (right) gene therapy approaches that have been tested in people with HIV on ART. Ex vivo strategies include gene editing to either delete or inactivate CCR5 or HIV provirus in CD4 + -enriched T cells using gene-editing tools such as zinc finger nucelases (ZFN) or CRISPR–Cas9. Alternatively, autologous T cells can be modified to express a CAR that can recognize HIV envelope, and this can then be reinfused into the participant. In vivo strategies, on the other hand, do not require external manipulation of cells; nanoparticles or viral vectors (such as adeno-associated virus (AAV)), which encapsulate mRNA or DNA, respectively, for the relevant gene to be expressed are administered directly to the patient. These approaches have recently been successful using lipid nanoparticles that contain mRNA encoding CRISPR–Cas9 135 or for expression of anti-HIV broadly neutralizing antibodies such as PG9 or VRC07 (ref. 125 ). PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; PLWH, person living with HIV.

Many emerging cell and gene therapies are designed to target viral proteins/epitopes that are expressed in abundance on the surface of tumor cells, for example CD19 for the treatment of lymphoma 129 . Various forms of the HIV viral envelope protein (gp120 trimers and monomers, gp41) are expressed on the surface of infected cells, while multiple peptides are presented via HLA molecules. These antigens are expressed at levels well below that of many cancer antigens now being successfully targeted in the clinic. Cell-based therapies such as CAR T cells, once infused into the patient, will only persist and differentiate if there is sufficient antigenic exposure; however, the levels of antigen during ART may be too low 130 . Removal of ART after infusion of CAR T cells (or similar products) could be used to expand these cells in vivo, or more potent latency-reversing agents could be used to enhance envelope protein expression. In addition, novel adjuvants could expand CAR T cells even when the antigen burden is low, as was recently demonstrated in the nonhuman primate model 131 .

The challenges here are primarily those of delivery to relevant cells. In addition to developing methods to target specific cells, which are common problems faced by all potential in vivo gene therapies, targeting latent proviruses also presents the problem of a lack of robust cell surface markers to identify cells harboring such proviruses. Progress in both of these areas will be needed to develop strategies to deliver gene-editing reagents to latently infected cells. Some promising in vivo delivery strategies for CRISPR–Cas9 have included adeno-associated virus to target the SIV virus in nonhuman primates on ART 127 , as well as using engineered CD4 + cell-homing messenger RNA (mRNA)-containing lipid nanoparticles in mouse models of HIV infection 132 .

Long-term in vivo secretion of antibodies or antibody-like molecules can be achieved following gene therapy vector delivery of antibody cassettes to tissues such as muscle and liver, where enhanced production of antibodies is needed, rather than specific delivery to infected CD4 + T cells. This can be achieved through direct intramuscular injection leading to uptake in the muscle or, alternatively, intravenous injection, which will allow for uptake in the liver. Ectopic expression of these antibodies in liver or muscle cells fails to recapitulate aspects of natural antibody production, such as responsiveness to antigen and ongoing somatic hypermutation. Therefore, editing the B cell Ig locus itself to express antibodies presents an alternative and attractive gene-editing strategy 133 , 134 .

Sustained production of these antivirals could result in sustained (perhaps lifelong) control of the virus. Many barriers to success exist. Antidrug antibodies that target and clear the vectors often form rapidly 125 , limiting the ability to deliver multiple doses. Advances in mRNA encapsulation within lipid nanoparticles may potentially revolutionize delivery of gene therapy, allowing for delivery of mRNA encoding CRISPR–Cas9 and related guide RNAs in vivo, as has recently been successfully demonstrated in the treatment of transthyretin amyloidosis 135 . Also, antibodies targeting multiple antigens will likely need to be produced at high levels to prevent virus replication and escape.

Advances in T cell manufacturing are expected, driven by cancer CAR T cell therapies, which will also benefit HIV therapies. Similarly, advances occurring in gene therapy treatments for genetic diseases, such as hemoglobinopathies, are catalyzing safer and nongenotoxic conditioning for HSPC transplants, for example based on drug–antibody conjugates. Practicality will also be enhanced by moving toward using allogeneic off-the-shelf products.

Gene and cell therapies now require a shift towards a practical focus, identifying ways to expand use, reduce costs, and allow deployment in resource-limited settings. This could be achieved through abbreviated ex vivo cell manufacturing, including automated closed-system devices (‘gene therapy in a box’), to produce product in a place-of-care setting 136 . While still in the early stages of development, in vivo gene therapy also presents exciting possibilities to significantly expand access by eliminating the need for external manipulation of cells and associated technological requirements.

The unique context of perinatal HIV infection necessitates pediatric-specific strategies to achieve ART-free remission in children. The case of the Mississippi child, who started therapy ~30 hours after birth and achieved remission off ART for 27 months before virus rebounded 137 , 138 , raised the possibility that remission for children can be attained. Subsequent reports of early-treated pediatric cases with long-term (>12 years) virological control off ART have provided examples of post-treatment control in children 139 , 140 .

The nature of the reservoir in children is unique from that in adults. For example, naive CD4 + T cells are a more important reservoir for the virus in children 141 , 142 . Further development of infant nonhuman primate models for evaluating ART and cure strategies will contribute to our understanding of the HIV reservoir and how to target it in the unique setting of infancy and immune development, but an understanding of the limitations of this model is also crucially important 141 , 142 , 143 , 144 , 145 .

Many of the recent advances in understanding HIV persistence during ART in adults, including frequency and transcriptional activity of intact virus, clonal expansion, sites of proviral integration, and inducibility, need to be applied to studies of children. Optimizing methods that can be adapted to small blood volumes are also needed.

In the context of childhood infection, clarity is needed on how latency is established in naive T cells, susceptibility of these cells to latency reversal, propensity for T cells to clonally expand, and the relative contribution of clonally expanded cells to viral rebound following cessation of ART. It is still unclear whether integration sites and reactivation potential are different in children, and whether these change with age. Given that initial studies suggest a less-inducible reservoir in cases of perinatal infection 146 , it is especially important to determine how to maximize latency reversal in children. The optimal timing of these interventions (for example, at the time of early ART initiation) could potentially limit the pool of infected cells that persist on ART; such approaches can be explored in a nonhuman primate model.

As in adults, better tools are needed to assess the impact of cure interventions in children, including quantification of HIV persistence and in-depth cellular immune profiling. There is a particular need for noninvasive tools, such as total body imaging, to assess central nervous system and other tissue-based reservoirs. It will also be important to identify biomarkers for post-treatment control, including the degree of reduction or alteration in the composition of the latent reservoir that may be predictive of pediatric remission or cure 147 . Finally, preclinical studies in infant nonhuman primates that test new interventions to reduce or eliminate persistent HIV and/or induce viral remission after ART interruption are needed to inform the development of HIV remission and cure intervention strategies. Early therapy alone is insufficient to reliably achieve a cure or long-term remission in children. Novel approaches, including earlier administration and use of more potent antiretroviral drugs, therapeutic vaccines, or other immunotherapeutics, such as broadly neutralizing antibodies and/or innate-immune-enhancing agents, will be necessary.

Research directed toward an HIV cure intertwines critical social, behavioral, and ethical aspects that must be incorporated in the scientific agenda. This research takes place within particular social contexts and communities that shape its permissibility and appropriateness. Accordingly, affected communities must be meaningfully engaged throughout the research process; social and behavioral factors must be interrogated and taken into account because they affect research feasibility, community support for the research, and the well-being of participants and other stakeholders. Research must also address the many ethical issues associated with developing a therapy, particularly since viable options for treatment are already available. Sufficient funding for research toward social, behavioral, and ethical aspects of a cure and for community involvement is therefore essential.

Substantial progress using more conceptual and normative approaches has also been made regarding the ethical issues associated with the interruption of ART 148 , 149 . Similarly, there has been attention focused on acceptable risk thresholds for research 150 . Finally, given the important role of treatment as prevention, efforts have focused on the ethics of partner-protection measures 151 .

Community engagement in HIV cure research is still suboptimal in many settings, being mostly been limited to advisory boards typically comprised of scientifically literate individuals. Capacity to discuss HIV cure research and to evaluate its potential implications for local and global communities must be built within diverse community groups. Communities should be empowered and supported through education and engagement at all levels of the research process to help shape the HIV cure research agenda and allow for potential study participants to have a voice in trial design 152 .

Since HIV cure research is highly complex and nuanced, there is also a need to ensure understanding of it among other key stakeholders, including Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) and clinicians. For example, IRBs need to appreciate the implications of ATIs for partners who they may not see as within their remit, and clinicians need to understand the rationale for ATIs in the research setting.

Attention must focus on broad representation (for example, age, race and ethnicity, gender and sexuality, geographic location, risk behaviors) in research. Diversity in participation is essential during the development of interventions aimed at complete HIV elimination or durable ART-free control. This necessitates research directed at understanding the reasons for under-representation of certain groups of people in HIV cure research. For example, cisgender and transgender women, as well as individuals of some racial and ethnic backgrounds, are less likely to participate in HIV-cure-focused clinical trials 153 . This highlights the need for more nuanced and theoretically engaged research to understand how gender, race, and other characteristics shape engagement with HIV cure research 154 . At the same time, legal and social considerations unique to each context must be identified and addressed. For example, local laws, stigma, and access to healthcare affect research involving the interruption of ART.

There is also a need to better define ethical considerations involved in the selection of populations of interest in which promising cure strategies will be tested. For example, should priority be given to testing new interventions in individuals who initiated treatment during acute infection over those who began treatment during chronic infection? What are the best means to identify and manage the ethical considerations in pediatric HIV cure research? In addition, what measures ought to be taken to ensure that recruitment is not skewed toward people with HIV in resource-limited settings? Further, ethical questions of equity and justice related to the distribution of safe and effective cure interventions must consider acceptability, scalability, and cost-effectiveness. The COVID-19 pandemic has raised unique considerations for research participants, staff, and communities 155 . Given the rapidly changing nature of the pandemic and the availability of COVID-19 vaccines and other treatments, there is a need to continually revise and assess the safety and feasibility of HIV cure research efforts.

During the study design phase, early engagement is needed in communities where research is being considered in order to determine the nature and acceptability of research-related risks. Similarly, stakeholder perceptions should be elicited to guide the development of target product profiles (the minimal and optimal characteristics of a new therapeutic intervention), as recently done for an HIV cure 5 . In especially complex clinical studies, formative research should be used to help develop a robust, informed consent process. Furthermore, nested social and behavioral research (basic, elemental, supportive, integrative) is needed to enhance understanding of the actual experiences of trial participants as well as of sexual partners of participants. These data will help provide a check on current practices, as well as provide a foundation for future efforts aimed at improving them.

Several of the key topics addressed in the previous sections are prerequisites for the development of successful cure strategies and interventions. To date, most HIV cure research has been restricted to high-income countries with relatively low HIV burden and has most often engaged men who have sex with men. HIV strains are genetically and biologically diverse, and host mechanisms of antiviral immunity required for durable control may differ by sex, geography, and ethnicity. Basic discovery research and clinical trials in resource-limited settings must be strengthened and will require enabling infrastructure development and capacity building.

In the next decade, we expect to see a greater understanding of HIV reservoirs, an increasing number of clinical trials and hopefully reports of individuals who achieved long-term remission with less intensive and more widely applicable strategies. On the basis of the current understanding and lessons from ART, it is likely that combinations of these approaches may be the first approach to be implemented. Inclusion of knowledge from fields such as oncology and COVID-19 could also greatly facilitate progress. Finally, open and responsible communication about trials and realistic expectations will remain important. Although safety is the highest priority, with increasing number of clinical trials, there is an increase in the possibility of adverse events which will need to be appropriately managed while allowing the field to advance.

This global scientific strategy, in combination with the recently developed target product profile 5 , will assist with guiding the field toward a widely applicable, acceptable, and affordable cure. The establishment of the HIV Cure Africa Acceleration Partnership 152 will hopefully enable broader engagement and facilitate rapid implementation of any successes into low- and middle-income settings. Fortunately, the resources for such work remain available, and the field is highly committed to making the long-term commitments necessary to develop an effective and scalable remission or cure strategy.

Hutter, G. et al. Long-term control of HIV by CCR5 ∆32/∆32 stem-cell transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 360 , 692–698 (2009).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Gupta, R. K. et al. HIV-1 remission following CCR5∆32/∆32 haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Nature 568 , 244–248 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Jiang, C. et al. Distinct viral reservoirs in individuals with spontaneous control of HIV-1. Nature 585 , 261–267 (2020).

Saez-Cirion, A. et al. Post-treatment HIV-1 controllers with a long-term virological remission after the interruption of early initiated antiretroviral therapy ANRS VISCONTI Study. PLoS Pathog. 9 , e1003211 (2013).

Lewin, S. R. et al. Multi-stakeholder consensus on a target product profile for an HIV cure. Lancet HIV 8 , e42–e50 (2021).

International, A. S. S. W. G. O. H. I. V. C. et al. Towards an HIV cure: a global scientific strategy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 12 , 607–614 (2012).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Deeks, S. G. et al. International AIDS Society global scientific strategy: towards an HIV cure 2016. Nat. Med. 22 , 839–850 (2016).

Eriksson, S. et al. Comparative analysis of measures of viral reservoirs in HIV-1 eradication studies. PLoS Pathog. 9 , e1003174 (2013).

Schaller, T. et al. HIV-1 capsid–cyclophilin interactions determine nuclear import pathway, integration targeting and replication efficiency. PLoS Pathog. 7 , e1002439 (2011).

Cohn, L. B. et al. HIV-1 integration landscape during latent and active infection. Cell 160 , 420–432 (2015).

Lee, G. Q. et al. Clonal expansion of genome-intact HIV-1 in functionally polarized Th1 CD4 + T cells. J. Clin. Investig. 127 , 2689–2696 (2017).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Simonetti, F. R. et al. Clonally expanded CD4 + T cells can produce infectious HIV-1 in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113 , 1883–1888 (2016).

Lorenzi, J. C. et al. Paired quantitative and qualitative assessment of the replication-competent HIV-1 reservoir and comparison with integrated proviral DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113 , E7908–E7916 (2016).

Bui, J. K. et al. Proviruses with identical sequences comprise a large fraction of the replication-competent HIV reservoir. PLoS Pathog. 13 , e1006283 (2017).

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Halvas, E. K. et al. HIV-1 viremia not suppressible by antiretroviral therapy can originate from large T cell clones producing infectious virus. J. Clin. Invest. 130 , 5847–5857 (2020).

Fletcher, C. V. et al. Persistent HIV-1 replication is associated with lower antiretroviral drug concentrations in lymphatic tissues. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111 , 2307–2312 (2014).

McManus, W. R. et al. HIV-1 in lymph nodes is maintained by cellular proliferation during antiretroviral therapy. J. Clin. Invest. 129 , 4629–4642 (2019).

Neidleman, J. et al. Phenotypic analysis of the unstimulated in vivo HIV CD4 T cell reservoir. eLife 9 , e60933 (2020).

Gosselin, A. et al. HIV persists in CCR6 + CD4 + T cells from colon and blood during antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 31 , 35–48 (2017).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Fromentin, R. et al. CD4 + T cells expressing PD-1, TIGIT and LAG-3 contribute to HIV persistence during ART. PLoS Pathog. 12 , e1005761 (2016).

Anderson, J. L. et al. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-Infected CCR6 + rectal CD4 + T cells and HIV persistence on antiretroviral therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 221 , 744–755 (2020).

Imamichi, H. et al. Defective HIV-1 proviruses produce novel protein-coding RNA species in HIV-infected patients on combination antiretroviral therapy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113 , 8783–8788 (2016).

Imamichi, H. et al. Defective HIV-1 proviruses produce viral proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117 , 3704–3710 (2020).

Pollack, R. A. et al. Defective HIV-1 proviruses are expressed and can be recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes, which shape the proviral landscape. Cell Host Microbe 21 , 494–506(2017).

Wu, G. et al. Gag p24 is a marker of HIV expression in tissues and correlates with immune response. J. Infect. Dis. 224 , 1593–1598 (2021).

Article PubMed CAS PubMed Central Google Scholar

Spudich, S. et al. Persistent HIV-infected cells in cerebrospinal fluid are associated with poorer neurocognitive performance. J. Clin. Invest. 129 , 3339–3346 (2019).

Maldarelli, F. et al. HIV latency. Specific HIV integration sites are linked to clonal expansion and persistence of infected cells. Science 345 , 179–183 (2014).

Wagner, T. A. et al. HIV latency. Proliferation of cells with HIV integrated into cancer genes contributes to persistent infection. Science 345 , 570–573 (2014).

Mendoza, P. et al. Antigen-responsive CD4 + T cell clones contribute to the HIV-1 latent reservoir. J. Exp. Med. 217 , e20200051 (2020).

Simonetti, F. R. et al. Antigen-driven clonal selection shapes the persistence of HIV-1-infected CD4 + T cells in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 131 , 145254 (2021).

Chomont, N. et al. HIV reservoir size and persistence are driven by T cell survival and homeostatic proliferation. Nat. Med. 15 , 893–900 (2009).

Ren, Y. et al. BCL-2 antagonism sensitizes cytotoxic T cell-resistant HIV reservoirs to elimination ex vivo. J. Clin. Investig. 130 , 2542–2559 (2020).

Kuo, H. H. et al. Anti-apoptotic protein BIRC5 maintains survival of HIV-1-infected CD4 + T cells. Immunity 48 , 1183–1194(2018).

Cummins, N. W. et al. Maintenance of the HIV reservoir is antagonized by selective BCL2 inhibition. J. Virol. 91 , e00012-17 (2017).

Scully, E. P. Sex differences in HIV infection. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 15 , 136–146 (2018).

Das, B. et al. Estrogen receptor-1 is a key regulator of HIV-1 latency that imparts gender-specific restrictions on the latent reservoir. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115 , E7795–E7804 (2018).

Prodger, J. L. et al. Reduced HIV-1 latent reservoir outgrowth and distinct immune correlates among women in Rakai, Uganda. JCI Insight 5 , e139287 (2020).

Falcinelli, S. D. et al. Impact of biological sex on immune activation and frequency of the latent HIV reservoir during suppressive antiretroviral therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 222 , 1843–1852 (2020).

Scully, E. P. et al. Sex-based differences in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reservoir activity and residual immune activation. J. Infect. Dis. 219 , 1084–1094 (2019).

Szotek, E. L., Narasipura, S. D. & Al-Harthi, L. 17β-Estradiol inhibits HIV-1 by inducing a complex formation between β-catenin and estrogen receptor alpha on the HIV promoter to suppress HIV transcription. Virology 443 , 375–383 (2013).

Abdel-Mohsen, M. et al. Recommendations for measuring HIV reservoir size in cure-directed clinical trials. Nat. Med. 26 , 1339–1350 (2020).

Gaebler, C. et al. Sequence evaluation and comparative analysis of novel assays for intact proviral HIV-1 DNA. J. Virol. 95 , e01986-20 (2021).

Bruner, K. M. et al. Defective proviruses rapidly accumulate during acute HIV-1 infection. Nat. Med. 22 , 1043–1049 (2016).

Peluso, M. J. et al. Differential decay of intact and defective proviral DNA in HIV-1-infected individuals on suppressive antiretroviral therapy. JCI Insight 5 , 132997 (2020).

Gandhi, R. T. et al. Selective decay of intact HIV-1 proviral DNA on antiretroviral therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 223 , 225–233 (2020).

Anderson, E. M. et al. Dynamic shifts in the HIV proviral landscape during long term combination antiretroviral therapy: implications for persistence and control of HIV infections. Viruses 12 , E136 (2020).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Sarabia, I. & Bosque, A. HIV-1 latency and latency reversal: does subtype matter? Viruses 11 , 1104 (2019).

Yukl, S. A. et al. HIV latency in isolated patient CD4 + T cells may be due to blocks in HIV transcriptional elongation, completion, and splicing. Sci. Transl. Med. 10 , eaap9927 (2018).

Pardons, M. et al. Single-cell characterization and quantification of translation-competent viral reservoirs in treated and untreated HIV infection. PLoS Pathog. 15 , e1007619 (2019).

Santangelo, P. J. et al. Whole-body immunoPET reveals active SIV dynamics in viremic and antiretroviral therapy-treated macaques. Nat. Methods 12 , 427–432 (2015).

McMahon, J. H. et al. A clinical trial of non-invasive imaging with an anti-HIV antibody labelled with copper-64 in people living with HIV and uninfected controls. EBioMedicine 65 , 103252 (2021).

De Scheerder, M. A. et al. HIV rebound is predominantly fueled by genetically identical viral expansions from diverse reservoirs. Cell Host Microbe 26 , 347–358(2019).

Mitchell, J. L. et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells sense HIV replication before detectable viremia following treatment interruption. J. Clin. Invest. 130 , 2845–2858 (2020).

Draz, M. S. et al. DNA engineered micromotors powered by metal nanoparticles for motion based cellphone diagnostics. Nat. Commun. 9 , 4282 (2018).

Richart, V. et al. High rate of long-term clinical events after ART resumption in HIV-positive patients exposed to antiretroviral therapy interruption. AIDS https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000003058 (2021).

Mendoza, D. et al. Comprehensive analysis of unique cases with extraordinary control over HIV replication. Blood 119 , 4645–4655 (2012).

Canoui, E. et al. A subset of extreme human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) controllers is characterized by a small HIV blood reservoir and a weak T-cell activation level. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 4 , ofx064 (2017).

Casado, C. et al. Permanent control of HIV-1 pathogenesis in exceptional elite controllers: a model of spontaneous cure. Sci. Rep. 10 , 1902 (2020).

Namazi, G. et al. The Control of HIV After Antiretroviral Medication Pause (CHAMP) Study: posttreatment controllers identified from 14 clinical studies. J. Infect. Dis. 218 , 1954–1963 (2018).

Galvez, C. et al. Extremely low viral reservoir in treated chronically HIV-1-infected individuals. EBioMedicine 57 , 102830 (2020).

Passaes, C. et al. Optimal maturation of the SIV-specific CD8 + T cell response after primary infection is associated with natural control of SIV: ANRS SIC Study. Cell Rep. 32 , 108174 (2020).

Bertagnolli, L. N. et al. Autologous IgG antibodies block outgrowth of a substantial but variable fraction of viruses in the latent reservoir for HIV-1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117 , 32066–32077 (2020).

Gondim, M. V. P. et al. Heightened resistance to host type 1 interferons characterizes HIV-1 at transmission and after antiretroviral therapy interruption. Sci. Transl. Med. 13 , eabd8179 (2021).

Huot, N. et al. Natural killer cells migrate into and control simian immunodeficiency virus replication in lymph node follicles in African green monkeys. Nat. Med. 23 , 1277–1286 (2017).

Madec, Y. et al. Natural history of HIV-control since seroconversion. AIDS 27 , 2451–2460 (2013).

Chun, T. W. et al. Effect of antiretroviral therapy on HIV reservoirs in elite controllers. J. Infect. Dis. 208 , 1443–1447 (2013).

Nixon, C. C. et al. Systemic HIV and SIV latency reversal via non-canonical NF-κB signalling in vivo. Nature 578 , 160–165 (2020).

McBrien, J. B. et al. Robust and persistent reactivation of SIV and HIV by N-803 and depletion of CD8 + cells. Nature 578 , 154–159 (2020).

Borducchi, E. N. et al. Ad26/MVA therapeutic vaccination with TLR7 stimulation in SIV-infected rhesus monkeys. Nature 540 , 284–287 (2016).

Gautam, R. et al. Pathogenicity and mucosal transmissibility of the R5-tropic simian/human immunodeficiency virus SHIV(AD8) in rhesus macaques: implications for use in vaccine studies. J. Virol. 86 , 8516–8526 (2012).

Okoye, A. A. et al. Early antiretroviral therapy limits SIV reservoir establishment to delay or prevent post-treatment viral rebound. Nat. Med. 24 , 1430–1440 (2018).

Khanal, S. et al. In vivo validation of the viral barcoding of simian immunodeficiency virus SIV mac239 and the development of new barcoded SIV and subtype B and C simian–human immunodeficiency viruses. J. Virol. 94 , e01420-19 (2019).

Elsheikh, M. M., Tang, Y., Li, D. & Jiang, G. Deep latency: a new insight into a functional HIV cure. EBioMedicine 45 , 624–629 (2019).

Kessing, C. F. et al. In vivo suppression of HIV rebound by didehydro-cortistatin A, a ‘block-and-lock’ strategy for HIV-1 treatment. Cell Rep. 21 , 600–611 (2017).

Margolis, D. M. et al. Curing HIV: seeking to target and clear persistent infection. Cell 181 , 189–206 (2020).

Hosmane, N. N. et al. Proliferation of latently infected CD4 + T cells carrying replication-competent HIV-1: potential role in latent reservoir dynamics. J. Exp. Med. 214 , 959–972 (2017).

Kok, Y. L. et al. Spontaneous reactivation of latent HIV-1 promoters is linked to the cell cycle as revealed by a genetic-insulators-containing dual-fluorescence HIV-1-based vector. Sci. Rep. 8 , 10204 (2018).

Singh, A., Razooky, B., Cox, C. D., Simpson, M. L. & Weinberger, L. S. Transcriptional bursting from the HIV-1 promoter is a significant source of stochastic noise in HIV-1 gene expression. Biophys. J. 98 , L32–L34 (2010).

Cillo, A. R. et al. Quantification of HIV-1 latency reversal in resting CD4 + T cells from patients on suppressive antiretroviral therapy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111 , 7078–7083 (2014).

Laird, G. M. et al. Ex vivo analysis identifies effective HIV-1 latency-reversing drug combinations. J. Clin. Invest. 125 , 1901–1912 (2015).

Zerbato, J. M. et al. Multiply spliced HIV RNA is a predictive measure of virus production ex vivo and in vivo following reversal of HIV latency. EBioMedicine 65 , 103241 (2021).

Huang, S. H. et al. Latent HIV reservoirs exhibit inherent resistance to elimination by CD8 + T cells. J. Clin. Investig. 128 , 876–889 (2018).

Gay, C. L. et al. Assessing the impact of AGS-004, a dendritic cell-based immunotherapy, and vorinostat on persistent HIV-1 Infection. Sci. Rep. 10 , 5134 (2020).

Fidler, S. et al. Antiretroviral therapy alone versus antiretroviral therapy with a kick and kill approach, on measures of the HIV reservoir in participants with recent HIV infection (the RIVER trial): a phase 2, randomised trial. Lancet 395 , 888–898 (2020).

Gutiérrez, C. et al. Bryostatin-1 for latent virus reactivation in HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 30 , 1385–1392 (2016).

Vibholm, L. et al. Short-course Toll-like receptor 9 agonist treatment impacts innate immunity and plasma viremia in individuals with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 64 , 1686–1695 (2017).

Riddler, S. A. et al. Vesatolimod, a toll-like receptor 7 agonist, induces immune activation in virally suppressed adults with HIV-1. Clin. Infect. Dis. 72 , e815–e824 (2020).

Elliott, J. H. et al. Short-term administration of disulfiram for reversal of latent HIV infection: a phase 2 dose-escalation study. Lancet HIV 2 , 17 (2015).

Article Google Scholar

McMahon, J. H. et al. Neurotoxicity with high dose disulfiram and vorinostat used for HIV latency reversal. AIDS https://doi.org/10.1097/qad.0000000000003091 (2021).

Kim, Y., Anderson, J. L. & Lewin, S. R. Getting the ‘kill’ into ‘shock and kill’: strategies to eliminate latent HIV. Cell Host Microbe 23 , 14–26 (2018).

Mousseau, G. et al. The tat inhibitor didehydro-cortistatin A prevents HIV-1 reactivation from latency. mBio 6 , e00465 (2015).

Ahlenstiel, C. et al. Novel RNA duplex locks HIV-1 in a latent state via chromatin-mediated transcriptional silencing. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 4 , e261 (2015).

Besnard, E. et al. The mTOR complex controls HIV latency. Cell Host Microbe 20 , 785–797 (2016).