Academic Experience

Great survey questions: How to write them & avoid common mistakes

Learning how to write survey questions is both art and science. The wording you choose can make the difference between accurate, useful data and just the opposite. Fortunately, we’ve got a raft of tips to help.

Figuring out how to make a good survey that yields actionable insights is all about sweating the details. And writing effective questionnaire questions is the first step.

Essential for success is understanding the different types of survey questions and how they work. Each format needs a slightly different approach to question-writing.

In this article, we’ll share how to write survey questionnaires and list some common errors to avoid so you can improve your surveys and the data they provide.

Free eBook: The Qualtrics survey template guide

Survey question types

Did you know that Qualtrics provides 23 question types you can use in your surveys ? Some are very popular and used frequently by a wide range of people from students to market researchers, while others are more specialist and used to explore complex topics. Here’s an introduction to some basic survey question formats, and how to write them well.

Multiple choice

Familiar to many, multiple choice questions ask a respondent to pick from a range of options. You can set up the question so that only one selection is possible, or allow more than one to be ticked.

When writing a multiple choice question…

- Be clear about whether the survey taker should choose one (“pick only one”) or several (“select all that apply”).

- Think carefully about the options you provide, since these will shape your results data.

- The phrase “of the following” can be helpful for setting expectations. For example, if you ask “What is your favorite meal” and provide the options “hamburger and fries”, “spaghetti and meatballs”, there’s a good chance your respondent’s true favorite won’t be included. If you add “of the following” the question makes more sense.

Asking participants to rank things in order, whether it’s order of preference, frequency or perceived value, is done using a rank structure. There can be a variety of interfaces, including drag-and-drop, radio buttons, text boxes and more.

When writing a rank order question…

- Explain how the interface works and what the respondent should do to indicate their choice. For example “drag and drop the items in this list to show your order of preference.”

- Be clear about which end of the scale is which. For example, “With the best at the top, rank these items from best to worst”

- Be as specific as you can about how the respondent should consider the options and how to rank them. For example, “thinking about the last 3 months’ viewing, rank these TV streaming services in order of quality, starting with the best”

Slider structures ask the respondent to move a pointer or button along a scale, usually a numerical one, to indicate their answers.

When writing a slider question…

- Consider whether the question format will be intuitive to your respondents, and whether you should add help text such as “click/tap and drag on the bar to select your answer”

- Qualtrics includes the option for an open field where your respondent can type their answer instead of using a slider. If you offer this, make sure to reference it in the survey question so the respondent understands its purpose.

Also known as an open field question, this format allows survey-takers to answer in their own words by typing into the comments box.

When writing a text entry question…

- Use open-ended question structures like “How do you feel about…” “If you said x, why?” or “What makes a good x?”

- Open-ended questions take more effort to answer, so use these types of questions sparingly.

- Be as clear and specific as possible in how you frame the question. Give them as much context as you can to help make answering easier. For example, rather than “How is our customer service?”, write “Thinking about your experience with us today, in what areas could we do better?”

Matrix table

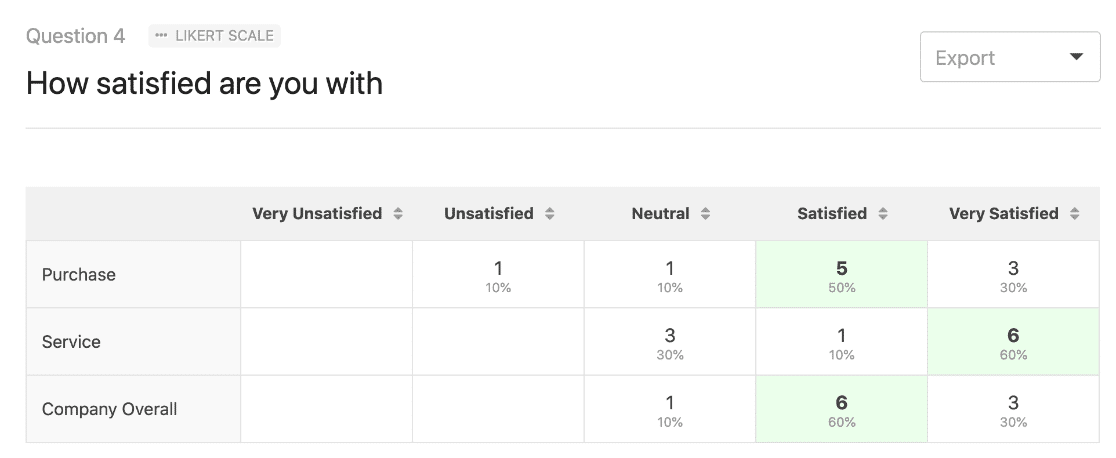

Matrix structures allow you to address several topics using the same rating system, for example a Likert scale (Very satisfied / satisfied / neither satisfied nor dissatisfied / dissatisfied / very dissatisfied).

When writing a matrix table question…

- Make sure the topics are clearly differentiated from each other, so that participants don’t get confused by similar questions placed side by side and answer the wrong one.

- Keep text brief and focused. A matrix includes a lot of information already, so make it easier for your survey-taker by using plain language and short, clear phrases in your matrix text.

- Add detail to the introductory static text if necessary to help keep the labels short. For example, if your introductory text says “In the Philadelphia store, how satisfied were you with the…” you can make the topic labels very brief, for example “staff friendliness” “signage” “price labeling” etc.

Now that you know your rating scales from your open fields, here are the 7 most common mistakes to avoid when you write questions. We’ve also added plenty of survey question examples to help illustrate the points.

Likert Scale Questions

Likert scales are commonly used in market research when dealing with single topic survyes. They're simple and most reliable when combatting survey bias . For each question or statement, subjects choose from a range of possible responses. The responses, for example, typically include:

- Strongly agree

- Strongly disagree

7 survey question examples to avoid.

There are countless great examples of writing survey questions but how do you know if your types of survey questions will perform well? We've highlighted the 7 most common mistakes when attempting to get customer feedback with online surveys.

Survey question mistake #1: Failing to avoid leading words / questions

Subtle wording differences can produce great differences in results. For example, non-specific words and ideas can cause a certain level of confusing ambiguity in your survey. “Could,” “should,” and “might” all sound about the same, but may produce a 20% difference in agreement to a question.

In addition, strong words such as “force” and “prohibit” represent control or action and can bias your results.

Example: The government should force you to pay higher taxes.

No one likes to be forced, and no one likes higher taxes. This agreement scale question makes it sound doubly bad to raise taxes. When survey questions read more like normative statements than questions looking for objective feedback, any ability to measure that feedback becomes difficult.

Wording alternatives can be developed. How about simple statements such as: The government should increase taxes, or the government needs to increase taxes.

Example: How would you rate the career of legendary outfielder Joe Dimaggio?

This survey question tells you Joe Dimaggio is a legendary outfielder. This type of wording can bias respondents.

How about replacing the word “legendary” with “baseball” as in: How would you rate the career of baseball outfielder Joe Dimaggio? A rating scale question like this gets more accurate answers from the start.

Survey question mistake #2: Failing to give mutually exclusive choices

Multiple choice response options should be mutually exclusive so that respondents can make clear choices. Don’t create ambiguity for respondents.

Review your survey and identify ways respondents could get stuck with either too many or no single, correct answers to choose from.

Example: What is your age group?

What answer would you select if you were 10, 20, or 30? Survey questions like this will frustrate a respondent and invalidate your results.

Example: What type of vehicle do you own?

This question has the same problem. What if the respondent owns a truck, hybrid, convertible, cross-over, motorcycle, or no vehicle at all?

Survey question mistake #3: Not asking direct questions

Questions that are vague and do not communicate your intent can limit the usefulness of your results. Make sure respondents know what you’re asking.

Example: What suggestions do you have for improving Tom’s Tomato Juice?

This question may be intended to obtain suggestions about improving taste, but respondents will offer suggestions about texture, the type of can or bottle, about mixing juices, or even suggestions relating to using tomato juice as a mixer or in recipes.

Example: What do you like to do for fun?

Finding out that respondents like to play Scrabble isn’t what the researcher is looking for, but it may be the response received. It is unclear that the researcher is asking about movies vs. other forms of paid entertainment. A respondent could take this question in many directions.

Survey question mistake #4: Forgetting to add a “prefer not to answer” option

Sometimes respondents may not want you to collect certain types of information or may not want to provide you with the types of information requested.

Questions about income, occupation, personal health, finances, family life, personal hygiene, and personal, political, or religious beliefs can be too intrusive and be rejected by the respondent.

Privacy is an important issue to most people. Incentives and assurances of confidentiality can make it easier to obtain private information.

While current research does not support that PNA (Prefer Not to Answer) options increase data quality or response rates, many respondents appreciate this non-disclosure option.

Furthermore, different cultural groups may respond differently. One recent study found that while U.S. respondents skip sensitive questions, Asian respondents often discontinue the survey entirely.

- What is your race?

- What is your age?

- Did you vote in the last election?

- What are your religious beliefs?

- What are your political beliefs?

- What is your annual household income?

These types of questions should be asked only when absolutely necessary. In addition, they should always include an option to not answer. (e.g. “Prefer Not to Answer”).

Survey question mistake #5: Failing to cover all possible answer choices

Do you have all of the options covered? If you are unsure, conduct a pretest version of your survey using “Other (please specify)” as an option.

If more than 10% of respondents (in a pretest or otherwise) select “other,” you are probably missing an answer. Review the “Other” text your test respondents have provided and add the most frequently mentioned new options to the list.

Example: You indicated that you eat at Joe's fast food once every 3 months. Why don't you eat at Joe's more often?

There isn't a location near my house

I don't like the taste of the food

Never heard of it

This question doesn’t include other options, such as healthiness of the food, price/value or some “other” reason. Over 10% of respondents would probably have a problem answering this question.

Survey question mistake #6: Not using unbalanced scales carefully

Unbalanced scales may be appropriate for some situations and promote bias in others.

For instance, a hospital might use an Excellent - Very Good - Good - Fair scale where “Fair” is the lowest customer satisfaction point because they believe “Fair” is absolutely unacceptable and requires correction.

The key is to correctly interpret your analysis of the scale. If “Fair” is the lowest point on a scale, then a result slightly better than fair is probably not a good one.

Additionally, scale points should represent equi-distant points on a scale. That is, they should have the same equal conceptual distance from one point to the next.

For example, researchers have shown the points to be nearly equi-distant on the strongly disagree–disagree–neutral–agree–strongly agree scale.

Set your bottom point as the worst possible situation and top point as the best possible, then evenly spread the labels for your scale points in-between.

Example: What is your opinion of Crazy Justin's auto-repair?

Pretty good

The Best Ever

This question puts the center of the scale at fantastic, and the lowest possible rating as “Pretty Good.” This question is not capable of collecting true opinions of respondents.

Survey question mistake #7: Not asking only one question at a time

There is often a temptation to ask multiple questions at once. This can cause problems for respondents and influence their responses.

Review each question and make sure it asks only one clear question.

Example: What is the fastest and most economical internet service for you?

This is really asking two questions. The fastest is often not the most economical.

Example: How likely are you to go out for dinner and a movie this weekend?

Dinner and Movie

Dinner Only

Even though “dinner and a movie” is a common term, this is two questions as well. It is best to separate activities into different questions or give respondents these options:

5 more tips on how to write a survey

Here are 5 easy ways to help ensure your survey results are unbiased and actionable.

1. Use the Funnel Technique

Structure your questionnaire using the “funnel” technique. Start with broad, general interest questions that are easy for the respondent to answer. These questions serve to warm up the respondent and get them involved in the survey before giving them a challenge. The most difficult questions are placed in the middle – those that take time to think about and those that are of less general interest. At the end, we again place general questions that are easier to answer and of broad interest and application. Typically, these last questions include demographic and other classification questions.

2. Use “Ringer” questions

In social settings, are you more introverted or more extroverted?

That was a ringer question and its purpose was to recapture your attention if you happened to lose focus earlier in this article.

Questionnaires often include “ringer” or “throw away” questions to increase interest and willingness to respond to a survey. These questions are about hot topics of the day and often have little to do with the survey. While these questions will definitely spice up a boring survey, they require valuable space that could be devoted to the main topic of interest. Use this type of question sparingly.

3. Keep your questionnaire short

Questionnaires should be kept short and to the point. Most long surveys are not completed, and the ones that are completed are often answered hastily. A quick look at a survey containing page after page of boring questions produces a response of, “there is no way I’m going to complete this thing”. If a questionnaire is long, the person must either be very interested in the topic, an employee, or paid for their time. Web surveys have some advantages because the respondent often can't view all of the survey questions at once. However, if your survey's navigation sends them page after page of questions, your response rate will drop off dramatically.

How long is too long? The sweet spot is to keep the survey to less than five minutes. This translates into about 15 questions. The average respondent is able to complete about 3 multiple choice questions per minute. An open-ended text response question counts for about three multiple choice questions depending, of course, on the difficulty of the question. While only a rule of thumb, this formula will accurately predict the limits of your survey.

4. Watch your writing style

The best survey questions are always easy to read and understand. As a rule of thumb, the level of sophistication in your survey writing should be at the 9th to 11th grade level. Don’t use big words. Use simple sentences and simple choices for the answers. Simplicity is always best.

5. Use randomization

We know that being the first on the list in elections increases the chance of being elected. Similar bias occurs in all questionnaires when the same answer appears at the top of the list for each respondent. Randomization corrects this bias by randomly rotating the order of the multiple choice matrix questions for each respondent.

Free Templates: Get free access to 30+ of Qualtrics' best survey templates

While not totally inclusive, these seven survey question tips are common offenders in building good survey questions. And the five tips above should steer you in the right direction.

Focus on creating clear questions and having an understandable, appropriate, and complete set of answer choices. Great questions and great answer choices lead to great research success. To learn more about survey question design, download our eBook, The Qualtrics survey template guide or get started with a free survey account with our world-class survey software .

Sarah Fisher

Related Articles

February 8, 2023

Smoothing the transition from school to work with work-based learning

December 6, 2022

How customer experience helps bring Open Universities Australia’s brand promise to life

August 18, 2022

School safety, learning gaps top of mind for parents this back-to-school season

August 9, 2022

3 things that will improve your teachers’ school experience

August 2, 2022

Why a sense of belonging at school matters for K-12 students

July 14, 2022

Improve the student experience with simplified course evaluations

March 17, 2022

Understanding what’s important to college students

February 18, 2022

Malala: ‘Education transforms lives, communities, and countries’

Stay up to date with the latest xm thought leadership, tips and news., request demo.

Ready to learn more about Qualtrics?

How to Write a Survey Introduction [+Examples]

Published: August 25, 2021

Writing a survey introduction probably isn't something you think about very often. That is until you're looking at the first screen of your almost finalized survey thinking "I should put something here. But what?"

While a potentially overlooked piece of the survey creation process, a good survey introduction is critical to improving survey completion rates and ensuring that the responses you receive are accurate. Taking the time to think about what information to include in your introduction can have a big impact on the success of your survey.

![assignment on survey → Free Download: 5 Customer Survey Templates [Access Now]](https://no-cache.hubspot.com/cta/default/53/9d36416b-3b0d-470c-a707-269296bb8683.png)

What is a Survey Introduction?

A survey introduction is the block of text that precedes the questions of your survey. It might be included at the top of an email requesting feedback or be the first slide in a series of questions. The survey introduction serves to set the stage for what the survey is, why the recipient should take the time to complete it, and what you're going to do with the information you collect. It should be compelling, informative, and reassuring.

.webp)

5 Free Customer Satisfaction Survey Templates

Easily measure customer satisfaction and begin to improve your customer experience.

- Net Promoter Score

- Customer Effort Score

Download Free

All fields are required.

You're all set!

Click this link to access this resource at any time.

How to Write a Survey Introduction

Start by thinking about the purpose of this survey. Who will be taking the survey? What information do you need for the project to be successful? Distill this information down into a sentence or two for your audience. Some examples may include:

- We're looking for feedback on our new product line for men.

- Tell us about your recent customer service experience.

- We're revamping our spring menu! What do you want for dinner?

Secondly, follow up with any logistical information they need to know about the survey. How many questions is it? When does the survey end? Who should they contact if they have additional questions? This might sound something like:

- This 5 question survey will take around 10 minutes to complete.

- Click below to access the short, two-question survey. For further information or feedback, please contact our support team at [email protected].

- This survey will be open until April 24th, 2022. Please take 5 minutes to provide your feedback before that time.

Finally, reassure the survey participants that their data is safe, and offer any information about how the survey data will be used:

- Your answers are anonymous and will be used to improve our future customer service strategy.

- Responses will be anonymized and analyzed for our upcoming report on consumer perception of insurance companies in the US. Please leave your email address if you'd like to receive a copy of the finished report.

- We read every response to our customer happiness surveys, and follow-up to make sure you're left with a positive experience.

No matter what you include in your survey introduction, make sure to keep it concise and as short as possible. Too long, and you risk readers dropping off and not completing your survey. It's also important to keep your survey messaging on-brand. If you typically use a brand voice that's quite corporate, switching to a conversational tone in your survey introduction will feel out of place. It might even make some readers question if the survey is truly coming from your company - causing distrust in its authenticity.

Finally, thank your respondents for their time. Even if their responses are negative, the fact that they're engaging with your survey is a great indicator of their loyalty . Customers will not take the time to provide feedback to companies they don't care about. Here are some phrases you can use to show your appreciation:

- This feedback is very helpful for our team in developing new features. Thank you so much for taking the time to complete this survey.

- We read every comment you leave on these surveys, so thank you for your feedback!

- We truly appreciate your insight and your time.

Want to make sure you've got it all covered? Save this checklist of the most important aspects to include in the survey introduction:

- How long will it take? (Minutes or number of questions)

- Why are you doing this survey?

- Why should they fill it out? Is there a giveaway for respondents (such as a draw for a $50 Amazon card) or another incentive to complete it?

- What are you going to do with the results? Are they anonymous?

- When does the survey close? What is the overall timeline?

- Are there any definitions or things they need to know before filling out the survey?

- Where should they go if they have questions or more feedback?

- Thank your participants for their time and feedback.

- Any additional information they need to fill out the survey with good, accurate data

Good Survey Introduction Examples

These survey introductions hit all the right notes. Read on for inspiration and additional tricks on how to write your own!

1. Squamish Off-Road Cycling Association (SORCA)

Don't forget to share this post!

Related articles.

Nonresponse Bias: What to Avoid When Creating Surveys

How to Make a Survey with a QR Code

50 Catchy Referral Slogans & How to Write Your Own

![assignment on survey How Automated Phone Surveys Work [+Tips and Examples]](https://www.hubspot.com/hubfs/phone-survey.webp)

How Automated Phone Surveys Work [+Tips and Examples]

Online Panels: What They Are & How to Use Them Effectively

The Complete Guide to Survey Logic (+Expert Tips)

Focus Group vs. Survey: Which One Should You Use?

![assignment on survey Leading Questions: What They Are & Why They Matter [+ Examples]](https://www.hubspot.com/hubfs/leading-questions-hero.webp)

Leading Questions: What They Are & Why They Matter [+ Examples]

What are Survey Sample Sizes & How to Find Your Sample Size

How to Create a Survey Results Report (+7 Examples to Steal)

Do you need to write a survey results report?

A great report will increase the impact of your survey results and encourage more readers to engage with the content.

Create Your Survey Now

In This Article

1. Use Data Visualization

2. write the key facts first, 3. write a short survey summary, 4. explain the motivation for your survey, 5. put survey statistics in context, 6. tell the reader what the outcome should be, 7. export your survey results in other formats, bonus tip: export data for survey analysis, faqs on writing survey summaries, how to write a survey results report.

Let’s walk through some tricks and techniques with real examples.

The most important thing about a survey report is that it allows readers to make sense of data. Visualizations are a key component of any survey summary.

Examples of Survey Visualizations

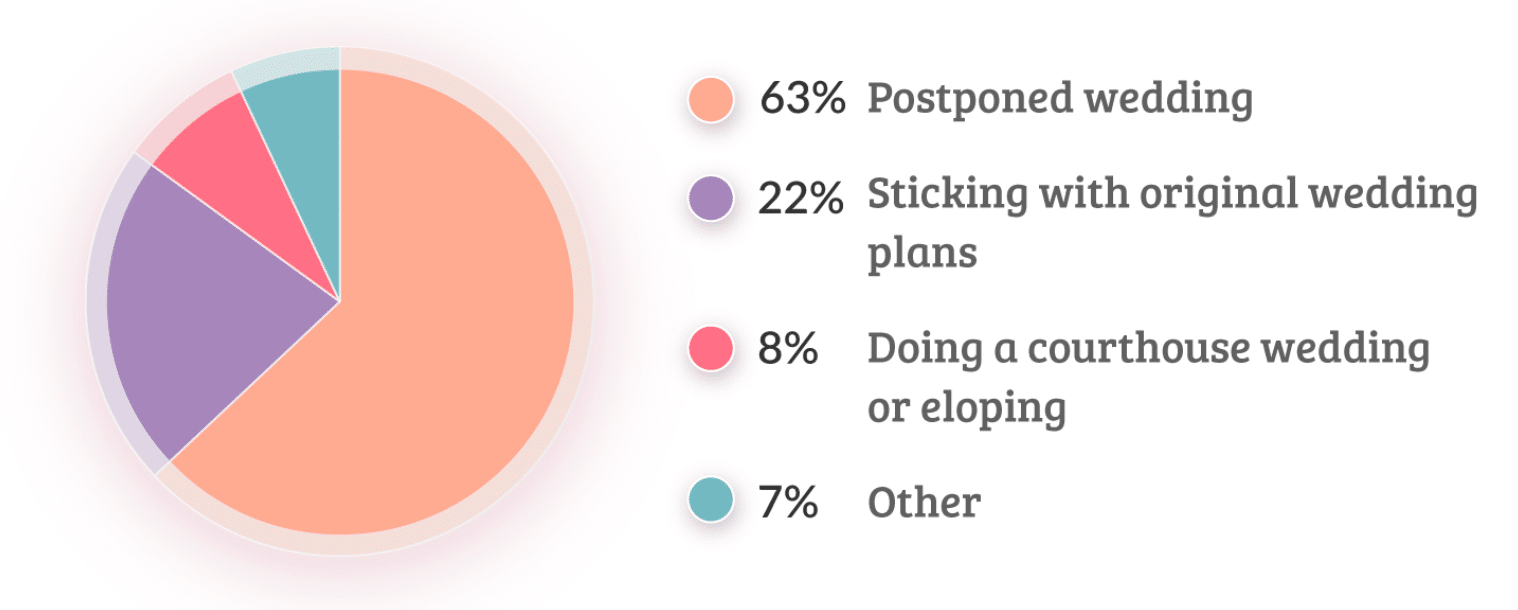

Pie charts are perfect when you want to bring statistics to life. Here’s a great example from a wedding survey:

Pie charts can be simple and still get the message across. A well-designed chart will also add impact and reinforce the story you want to tell.

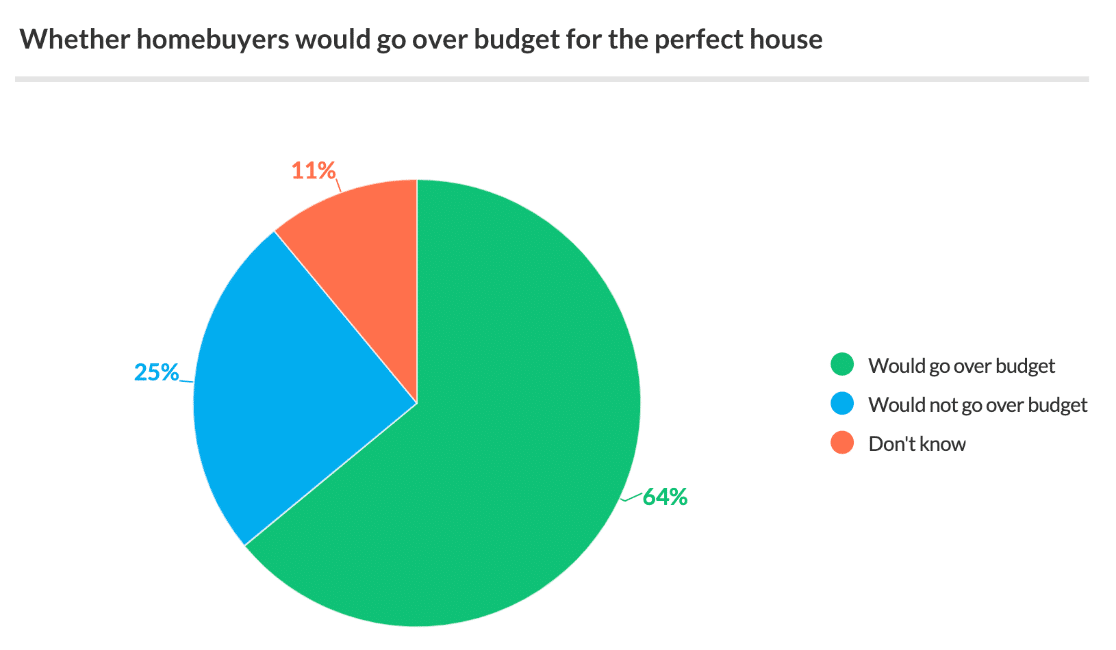

Here’s another great example from a homebuyer survey introduction:

If your survey is made up of open-ended questions, it might be more challenging to produce charts. If that’s the case, you can write up your findings instead. We’ll look at that next.

When you’re thinking about how to write a summary of survey results, remember that the introduction needs to get the reader’s attention.

Focusing on key facts helps you to do that right at the start.

This is why it’s usually best to write the survey introduction at the end once the rest of the survey report has been compiled. That way, you know what the big takeaways are.

This is an easy and powerful way to write a survey introduction that encourages the reader to investigate.

Examples of Survey Summaries With Key Facts

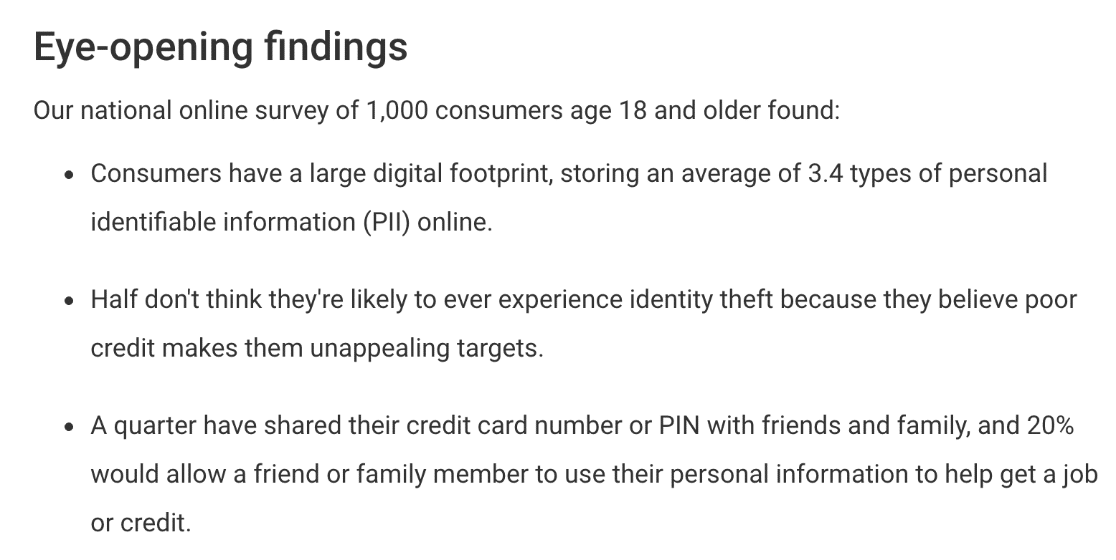

Here’s an awesome example of a survey summary that immediately draws the eye.

The key finding is presented first, and then we see a fact about half the group immediately after:

Using this order lets us see the impactful survey responses right up top.

If you need help deciding which questions to ask in your survey, check out this article on the best survey questions to include.

Your survey summary should give the reader a complete overview of the content. But you don’t want to take up too much space.

Survey summaries are sometimes called executive summaries because they’re designed to be quickly digested by decision-makers.

You’ll want to filter out the less important findings and focus on what matters. A 1-page summary is enough to get this information across. You might want to leave space for a table of contents on this page too.

Examples of Short Survey Introductions

One way to keep a survey summary short is to use a teaser at the start.

Here’s an example introduction that doesn’t state all of its findings but gives us the incentive to keep reading:

And here’s a great survey introduction that summarizes the findings in just one sentence:

In WPForms, you can reduce the size of your survey report by excluding questions you don’t need. We decided to remove this question from the report PDF because it has no answers. Just click the arrow at the top, and it won’t appear in the final printout:

This is a great way to quickly build a PDF summary of your survey that only includes the most important questions. You can also briefly explain your methodology.

When you create a survey in WordPress, you probably have a good idea of your reasons for doing so.

Make your purpose clear in the intro. For example, if you’re running a demographic survey , you might want to clarify that you’ll use this information to target your audience more effectively.

The reader must know exactly what you want to find out. Ideally, you should also explain why you wanted to create the survey in the first place. This can help you to reach the correct target audience for your survey.

Examples of Intros that Explain Motivation

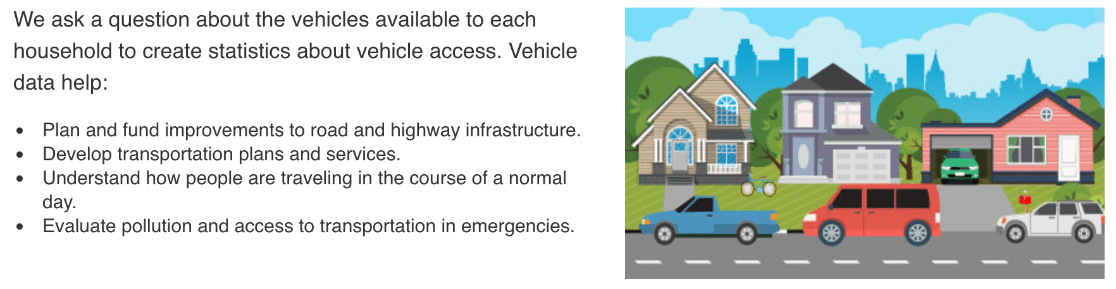

This vehicle survey was carried out to help with future planning, so the introduction makes the purpose clear to the reader:

Having focused questions can help to give your survey a clear purpose. We have some questionnaire examples and templates that can help with that.

Explaining why you ran the survey helps to give context, which we’ll talk about more next.

Including numbers in a survey summary is important. But your survey summary should tell a story too.

Adding numbers to your introduction will help draw the eye, but you’ll also want to explain what the numbers tell you.

Otherwise, you’ll have a list of statistics that don’t mean much to the reader.

Examples of Survey Statistics in Context

Here’s a great example of a survey introduction that uses the results from the survey to tell a story.

Another way to put numbers in context is to present the results visually.

Here, WPForms has automatically created a table from our Likert Scale question that makes it easy to see a positive trend in the survey data:

If you’d like to use a Likert scale to produce a chart like this, check out this article on the best Likert scale questions for survey forms .

Now that your survey report is done, you’ll likely want action to be taken based on your findings.

That’s why it’s a good idea to make a recommendation.

If you already explained your reasons for creating the survey, you can naturally add a few sentences on the outcomes you want to see.

Examples of Survey Introductions with Recommendations

Here’s a nice example of a survey introduction that clearly states the outcomes that the organization would like to happen now that the survey is published:

This helps to focus the reader on the content and helps them to understand why the survey is important. Respondents are more likely to give honest answers if they believe that a positive outcome will come from the survey.

You can also cite related research here to give your reasoning more weight.

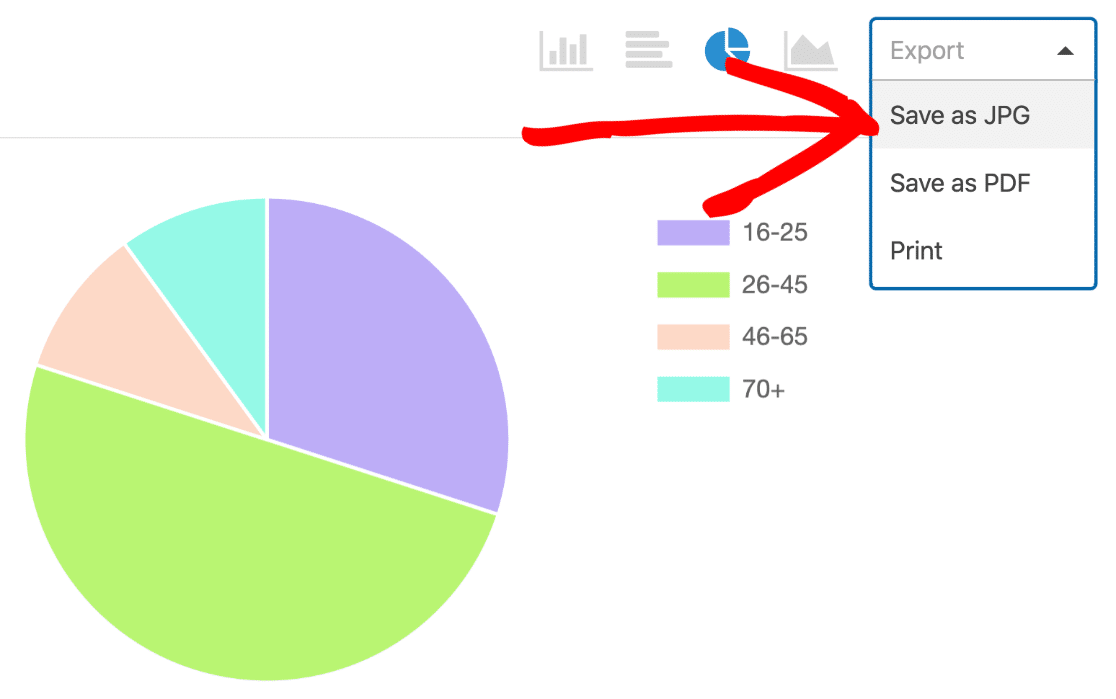

You can easily create pie charts in the WPForms Surveys and Polls addon. It allows you to change the way your charts look without being overwhelmed by design options.

This handy feature will save tons of time when you’re composing your survey results.

Once you have your charts, exporting them allows you to use them in other ways. You may want to embed them in marketing materials like:

- Presentation slides

- Infographics

- Press releases

WPForms makes it easy to export any graphic from your survey results so you can use it on your website or in slides.

Just use the dropdown to export your survey pie chart as a JPG or PDF:

And that’s it! You now know how to create an impactful summary of survey results and add these to your marketing material or reports.

WPForms is the best form builder plugin for WordPress. As well as having the best survey tools, it also has the best data export options.

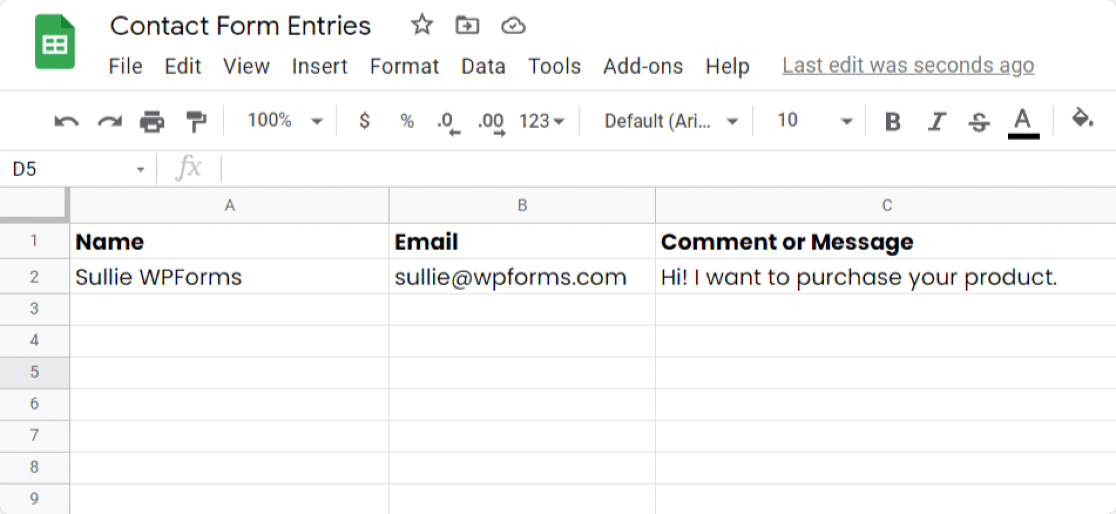

Often, you’ll want to export form entries to analyze them in other tools. You can do exactly the same thing with your survey data.

For example, you can:

- Export your form entries or survey data to Excel

- Automatically send survey responses to a Google Sheet

We really like the Google Sheets addon in WPForms because it sends your entries to a Google Sheet as soon as they’re submitted. And you can connect any form or survey to a Sheet without writing any code.

The Google Sheets integration is powerful enough to send all of your metrics. You can add columns to your Sheet and map the data points right from your WordPress form.

This is an ideal solution if you want to give someone else access to your survey data so they can crunch the numbers in spreadsheet format.

We’ll finish up with a few questions we’ve been asked about survey reporting.

What Is a Survey Report and What Should It Include?

A survey report compiles all data collected during a survey and presents it objectively. The report often summarizes pages of data from all responses received and makes it easier for the audience to process and digest.

How Do You Present Survey Results in an Impactful Way?

The best way to present survey results is to use visualizations. Charts, graphs, and infographics will make your survey outcomes easier to interpret.

For online surveys, WPForms has an awesome Surveys and Polls addon that makes it easy to publish many types of surveys and collect data using special survey fields:

- Likert Scale (sometimes called a matrix question )

- Net Promoter Score (sometimes called an NPS Survey)

- Star Rating

- Single Line Text

- Multiple Choice (sometimes called radio buttons )

You can turn on survey reporting at any time, even if the form expiry date has passed.

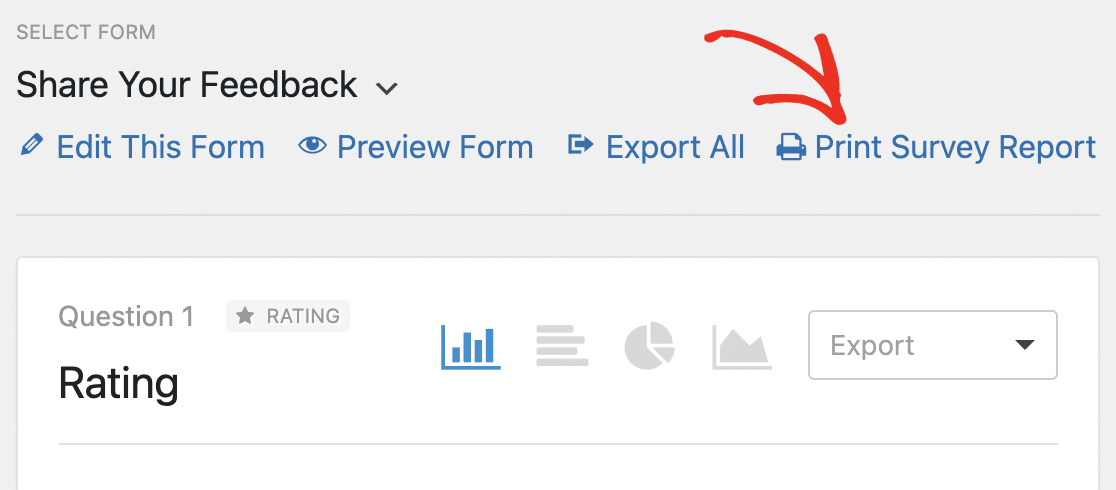

To present your results, create a beautiful PDF by clicking Print Survey Report right from the WordPress dashboard:

Next Step: Make Your Survey Form

To create a great survey summary, you’ll want to start out with a great survey form. Check out this article on how to create a survey form online to learn how to create and customize your surveys in WordPress.

You can also:

- Learn how to create a popup WordPress survey

- Read some rating scale question examples

- Get started easily with a customer survey template from the WPForms template library.

Ready to build your survey? Get started today with the easiest WordPress form builder plugin. WPForms Pro includes free survey form templates and offers a 14-day money-back guarantee.

If this article helped you out, please follow us on Facebook and Twitter for more free WordPress tutorials and guides.

Using WordPress and want to get WPForms for free?

Enter the URL to your WordPress website to install.

This is really good

Hi Jocasta! Glad to hear that you enjoyed our article! Please check back often as we’re always adding new content as well as updating old ones!

Hi, I need to write an opinion poll report would you help with a sample I could use

Hi Thuku, I’m sorry but we don’t have any such examples available as it’s a bit outside our purview. A quick Google search does show some sites with information and examples regarding this though. I hope that helps!

With the Likert Scale what visualisation options are available? For example if there were 30 questions… I would like to be able to total up for all questions how many said never, or often… etc… and for each ‘x’ option for example if it was chocolate bars down the side and never through to often across the top… for each question… I would like to total for all questions for each chocolate bar… the totals of never through to often…? can you help?

Hey Nigel- to achieve what you’ve mentioned, I’d recommend you to make use of the Survey and Poll addon that has the ability to display the number of polls count. Here is a complete guide on this addon

If you’ve any questions, please get in touch with the support team and we’d be happy to assist you further!

Thanks, and have a good one 🙂

I am looking for someone to roll-up survey responses and prepare presentations/graphs. I have 58 responses. Does this company offer this as an option? If so, what are the cost?

Hi Ivory! I apologize for any misunderstanding, but we do not provide such services.

Hi! Can you make survey report.

Hi Umay! I apologize as I’m not entirely certain about your question, or what you’re looking to do. In case it helps though, our Survey and Polls addon does have some features to generate survey reports. You can find out more about that in this article .

I hope this helps to clarify 🙂 If you have any further questions about this, please contact us if you have an active subscription. If you do not, don’t hesitate to drop us some questions in our support forums .

Super helpful..

Hi Shaz! We’re glad to hear that you found this article helpful. Please check back often as we’re always adding new content and making updates to old ones 🙂

Hi , can you help meon how to present the questionnaire answer on my report writing

Hi Elida – Yes, we will be happy to help!

If you have a WPForms license, you have access to our email support, so please submit a support ticket . Otherwise, we provide limited complimentary support in the WPForms Lite WordPress.org support forum .

Add a Comment Cancel reply

We're glad you have chosen to leave a comment. Please keep in mind that all comments are moderated according to our privacy policy , and all links are nofollow. Do NOT use keywords in the name field. Let's have a personal and meaningful conversation.

Your Comment

Your Real Name

Your Email Address

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This form is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Add Your Comment

- Testimonials

- FTC Disclosure

- Online Form Builder

- Conditional Logic

- Conversational Forms

- Form Landing Pages

- Entry Management

- Form Abandonment

- Form Notifications

- Form Templates

- File Uploads

- Calculation Forms

- Geolocation Forms

- Multi-Page Forms

- Newsletter Forms

- Payment Forms

- Post Submissions

- Signature Forms

- Spam Protection

- Surveys and Polls

- User Registration

- HubSpot Forms

- Mailchimp Forms

- Brevo Forms

- Salesforce Forms

- Authorize.Net

- PayPal Forms

- Square Forms

- Stripe Forms

- Documentation

- Plans & Pricing

- WordPress Hosting

- Start a Blog

- Make a Website

- Learn WordPress

- WordPress Forms for Nonprofits

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Survey Research | Definition, Examples & Methods

Survey Research | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on August 20, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Survey research means collecting information about a group of people by asking them questions and analyzing the results. To conduct an effective survey, follow these six steps:

- Determine who will participate in the survey

- Decide the type of survey (mail, online, or in-person)

- Design the survey questions and layout

- Distribute the survey

- Analyze the responses

- Write up the results

Surveys are a flexible method of data collection that can be used in many different types of research .

Table of contents

What are surveys used for, step 1: define the population and sample, step 2: decide on the type of survey, step 3: design the survey questions, step 4: distribute the survey and collect responses, step 5: analyze the survey results, step 6: write up the survey results, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about surveys.

Surveys are used as a method of gathering data in many different fields. They are a good choice when you want to find out about the characteristics, preferences, opinions, or beliefs of a group of people.

Common uses of survey research include:

- Social research : investigating the experiences and characteristics of different social groups

- Market research : finding out what customers think about products, services, and companies

- Health research : collecting data from patients about symptoms and treatments

- Politics : measuring public opinion about parties and policies

- Psychology : researching personality traits, preferences and behaviours

Surveys can be used in both cross-sectional studies , where you collect data just once, and in longitudinal studies , where you survey the same sample several times over an extended period.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Before you start conducting survey research, you should already have a clear research question that defines what you want to find out. Based on this question, you need to determine exactly who you will target to participate in the survey.

Populations

The target population is the specific group of people that you want to find out about. This group can be very broad or relatively narrow. For example:

- The population of Brazil

- US college students

- Second-generation immigrants in the Netherlands

- Customers of a specific company aged 18-24

- British transgender women over the age of 50

Your survey should aim to produce results that can be generalized to the whole population. That means you need to carefully define exactly who you want to draw conclusions about.

Several common research biases can arise if your survey is not generalizable, particularly sampling bias and selection bias . The presence of these biases have serious repercussions for the validity of your results.

It’s rarely possible to survey the entire population of your research – it would be very difficult to get a response from every person in Brazil or every college student in the US. Instead, you will usually survey a sample from the population.

The sample size depends on how big the population is. You can use an online sample calculator to work out how many responses you need.

There are many sampling methods that allow you to generalize to broad populations. In general, though, the sample should aim to be representative of the population as a whole. The larger and more representative your sample, the more valid your conclusions. Again, beware of various types of sampling bias as you design your sample, particularly self-selection bias , nonresponse bias , undercoverage bias , and survivorship bias .

There are two main types of survey:

- A questionnaire , where a list of questions is distributed by mail, online or in person, and respondents fill it out themselves.

- An interview , where the researcher asks a set of questions by phone or in person and records the responses.

Which type you choose depends on the sample size and location, as well as the focus of the research.

Questionnaires

Sending out a paper survey by mail is a common method of gathering demographic information (for example, in a government census of the population).

- You can easily access a large sample.

- You have some control over who is included in the sample (e.g. residents of a specific region).

- The response rate is often low, and at risk for biases like self-selection bias .

Online surveys are a popular choice for students doing dissertation research , due to the low cost and flexibility of this method. There are many online tools available for constructing surveys, such as SurveyMonkey and Google Forms .

- You can quickly access a large sample without constraints on time or location.

- The data is easy to process and analyze.

- The anonymity and accessibility of online surveys mean you have less control over who responds, which can lead to biases like self-selection bias .

If your research focuses on a specific location, you can distribute a written questionnaire to be completed by respondents on the spot. For example, you could approach the customers of a shopping mall or ask all students to complete a questionnaire at the end of a class.

- You can screen respondents to make sure only people in the target population are included in the sample.

- You can collect time- and location-specific data (e.g. the opinions of a store’s weekday customers).

- The sample size will be smaller, so this method is less suitable for collecting data on broad populations and is at risk for sampling bias .

Oral interviews are a useful method for smaller sample sizes. They allow you to gather more in-depth information on people’s opinions and preferences. You can conduct interviews by phone or in person.

- You have personal contact with respondents, so you know exactly who will be included in the sample in advance.

- You can clarify questions and ask for follow-up information when necessary.

- The lack of anonymity may cause respondents to answer less honestly, and there is more risk of researcher bias.

Like questionnaires, interviews can be used to collect quantitative data: the researcher records each response as a category or rating and statistically analyzes the results. But they are more commonly used to collect qualitative data : the interviewees’ full responses are transcribed and analyzed individually to gain a richer understanding of their opinions and feelings.

Next, you need to decide which questions you will ask and how you will ask them. It’s important to consider:

- The type of questions

- The content of the questions

- The phrasing of the questions

- The ordering and layout of the survey

Open-ended vs closed-ended questions

There are two main forms of survey questions: open-ended and closed-ended. Many surveys use a combination of both.

Closed-ended questions give the respondent a predetermined set of answers to choose from. A closed-ended question can include:

- A binary answer (e.g. yes/no or agree/disagree )

- A scale (e.g. a Likert scale with five points ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree )

- A list of options with a single answer possible (e.g. age categories)

- A list of options with multiple answers possible (e.g. leisure interests)

Closed-ended questions are best for quantitative research . They provide you with numerical data that can be statistically analyzed to find patterns, trends, and correlations .

Open-ended questions are best for qualitative research. This type of question has no predetermined answers to choose from. Instead, the respondent answers in their own words.

Open questions are most common in interviews, but you can also use them in questionnaires. They are often useful as follow-up questions to ask for more detailed explanations of responses to the closed questions.

The content of the survey questions

To ensure the validity and reliability of your results, you need to carefully consider each question in the survey. All questions should be narrowly focused with enough context for the respondent to answer accurately. Avoid questions that are not directly relevant to the survey’s purpose.

When constructing closed-ended questions, ensure that the options cover all possibilities. If you include a list of options that isn’t exhaustive, you can add an “other” field.

Phrasing the survey questions

In terms of language, the survey questions should be as clear and precise as possible. Tailor the questions to your target population, keeping in mind their level of knowledge of the topic. Avoid jargon or industry-specific terminology.

Survey questions are at risk for biases like social desirability bias , the Hawthorne effect , or demand characteristics . It’s critical to use language that respondents will easily understand, and avoid words with vague or ambiguous meanings. Make sure your questions are phrased neutrally, with no indication that you’d prefer a particular answer or emotion.

Ordering the survey questions

The questions should be arranged in a logical order. Start with easy, non-sensitive, closed-ended questions that will encourage the respondent to continue.

If the survey covers several different topics or themes, group together related questions. You can divide a questionnaire into sections to help respondents understand what is being asked in each part.

If a question refers back to or depends on the answer to a previous question, they should be placed directly next to one another.

Before you start, create a clear plan for where, when, how, and with whom you will conduct the survey. Determine in advance how many responses you require and how you will gain access to the sample.

When you are satisfied that you have created a strong research design suitable for answering your research questions, you can conduct the survey through your method of choice – by mail, online, or in person.

There are many methods of analyzing the results of your survey. First you have to process the data, usually with the help of a computer program to sort all the responses. You should also clean the data by removing incomplete or incorrectly completed responses.

If you asked open-ended questions, you will have to code the responses by assigning labels to each response and organizing them into categories or themes. You can also use more qualitative methods, such as thematic analysis , which is especially suitable for analyzing interviews.

Statistical analysis is usually conducted using programs like SPSS or Stata. The same set of survey data can be subject to many analyses.

Finally, when you have collected and analyzed all the necessary data, you will write it up as part of your thesis, dissertation , or research paper .

In the methodology section, you describe exactly how you conducted the survey. You should explain the types of questions you used, the sampling method, when and where the survey took place, and the response rate. You can include the full questionnaire as an appendix and refer to it in the text if relevant.

Then introduce the analysis by describing how you prepared the data and the statistical methods you used to analyze it. In the results section, you summarize the key results from your analysis.

In the discussion and conclusion , you give your explanations and interpretations of these results, answer your research question, and reflect on the implications and limitations of the research.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

A questionnaire is a data collection tool or instrument, while a survey is an overarching research method that involves collecting and analyzing data from people using questionnaires.

A Likert scale is a rating scale that quantitatively assesses opinions, attitudes, or behaviors. It is made up of 4 or more questions that measure a single attitude or trait when response scores are combined.

To use a Likert scale in a survey , you present participants with Likert-type questions or statements, and a continuum of items, usually with 5 or 7 possible responses, to capture their degree of agreement.

Individual Likert-type questions are generally considered ordinal data , because the items have clear rank order, but don’t have an even distribution.

Overall Likert scale scores are sometimes treated as interval data. These scores are considered to have directionality and even spacing between them.

The type of data determines what statistical tests you should use to analyze your data.

The priorities of a research design can vary depending on the field, but you usually have to specify:

- Your research questions and/or hypotheses

- Your overall approach (e.g., qualitative or quantitative )

- The type of design you’re using (e.g., a survey , experiment , or case study )

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods (e.g., questionnaires , observations)

- Your data collection procedures (e.g., operationalization , timing and data management)

- Your data analysis methods (e.g., statistical tests or thematic analysis )

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, June 22). Survey Research | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved June 26, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/survey-research/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, questionnaire design | methods, question types & examples, what is a likert scale | guide & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

You're signed out

Sign in to ask questions, follow content, and engage with the Community

- Canvas Instructor

- Instructor Guide

How do I create a survey in my course?

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Printer Friendly Page

- Report Inappropriate Content

in Instructor Guide

Note: You can only embed guides in Canvas courses. Embedding on other sites is not supported.

Community Help

View our top guides and resources:.

To participate in the Instructurer Community, you need to sign up or log in:

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 9: Survey Research

Constructing Survey Questionnaires

Learning Objectives

- Describe the cognitive processes involved in responding to a survey item.

- Explain what a context effect is and give some examples.

- Create a simple survey questionnaire based on principles of effective item writing and organization.

The heart of any survey research project is the survey questionnaire itself. Although it is easy to think of interesting questions to ask people, constructing a good survey questionnaire is not easy at all. The problem is that the answers people give can be influenced in unintended ways by the wording of the items, the order of the items, the response options provided, and many other factors. At best, these influences add noise to the data. At worst, they result in systematic biases and misleading results. In this section, therefore, we consider some principles for constructing survey questionnaires to minimize these unintended effects and thereby maximize the reliability and validity of respondents’ answers.

Survey Responding as a Psychological Process

Before looking at specific principles of survey questionnaire construction, it will help to consider survey responding as a psychological process.

A Cognitive Model

Figure 9.1 presents a model of the cognitive processes that people engage in when responding to a survey item (Sudman, Bradburn, & Schwarz, 1996) [1] . Respondents must interpret the question, retrieve relevant information from memory, form a tentative judgment, convert the tentative judgment into one of the response options provided (e.g., a rating on a 1-to-7 scale), and finally edit their response as necessary.

Consider, for example, the following questionnaire item:

How many alcoholic drinks do you consume in a typical day?

- _____ a lot more than average

- _____ somewhat more than average

- _____ average

- _____ somewhat fewer than average

- _____ a lot fewer than average

Although this item at first seems straightforward, it poses several difficulties for respondents. First, they must interpret the question. For example, they must decide whether “alcoholic drinks” include beer and wine (as opposed to just hard liquor) and whether a “typical day” is a typical weekday, typical weekend day, or both . Even though Chang and Krosnick (2003) [2] found that asking about “typical” behaviour has been shown to be more valid than asking about “past” behaviour, their study compared “typical week” to “past week” and may be different when considering typical weekdays or weekend days) . Once they have interpreted the question, they must retrieve relevant information from memory to answer it. But what information should they retrieve, and how should they go about retrieving it? They might think vaguely about some recent occasions on which they drank alcohol, they might carefully try to recall and count the number of alcoholic drinks they consumed last week, or they might retrieve some existing beliefs that they have about themselves (e.g., “I am not much of a drinker”). Then they must use this information to arrive at a tentative judgment about how many alcoholic drinks they consume in a typical day. For example, this mental calculation might mean dividing the number of alcoholic drinks they consumed last week by seven to come up with an average number per day. Then they must format this tentative answer in terms of the response options actually provided. In this case, the options pose additional problems of interpretation. For example, what does “average” mean, and what would count as “somewhat more” than average? Finally, they must decide whether they want to report the response they have come up with or whether they want to edit it in some way. For example, if they believe that they drink much more than average, they might not want to report th e higher number for fear of looking bad in the eyes of the researcher.

From this perspective, what at first appears to be a simple matter of asking people how much they drink (and receiving a straightforward answer from them) turns out to be much more complex.

Context Effects on Questionnaire Responses

Again, this complexity can lead to unintended influences on respondents’ answers. These are often referred to as context effects because they are not related to the content of the item but to the context in which the item appears (Schwarz & Strack, 1990) [3] . For example, there is an item-order effect when the order in which the items are presented affects people’s responses. One item can change how participants interpret a later item or change the information that they retrieve to respond to later items. For example, researcher Fritz Strack and his colleagues asked college students about both their general life satisfaction and their dating frequency (Strack, Martin, & Schwarz, 1988) [4] . When the life satisfaction item came first, the correlation between the two was only −.12, suggesting that the two variables are only weakly related. But when the dating frequency item came first, the correlation between the two was +.66, suggesting that those who date more have a strong tendency to be more satisfied with their lives. Reporting the dating frequency first made that information more accessible in memory so that they were more likely to base their life satisfaction rating on it.

The response options provided can also have unintended effects on people’s responses (Schwarz, 1999) [5] . For example, when people are asked how often they are “really irritated” and given response options ranging from “less than once a year” to “more than once a month,” they tend to think of major irritations and report being irritated infrequently. But when they are given response options ranging from “less than once a day” to “several times a month,” they tend to think of minor irritations and report being irritated frequently. People also tend to assume that middle response options represent what is normal or typical. So if they think of themselves as normal or typical, they tend to choose middle response options. For example, people are likely to report watching more television when the response options are centred on a middle option of 4 hours than when centred on a middle option of 2 hours. To mitigate against order effects, rotate questions and response items when there is no natural order. Counterbalancing is a good practice for survey questions and can reduce response order effects which show that among undecided voters, the first candidate listed in a ballot receives a 2.5% boost simply by virtue of being listed first [6] !

Writing Survey Questionnaire Items

Types of items.

Questionnaire items can be either open-ended or closed-ended. Open-ended items simply ask a question and allow participants to answer in whatever way they choose. The following are examples of open-ended questionnaire items.

- “What is the most important thing to teach children to prepare them for life?”

- “Please describe a time when you were discriminated against because of your age.”

- “Is there anything else you would like to tell us about?”

Open-ended items are useful when researchers do not know how participants might respond or want to avoid influencing their responses. They tend to be used when researchers have more vaguely defined research questions—often in the early stages of a research project. Open-ended items are relatively easy to write because there are no response options to worry about. However, they take more time and effort on the part of participants, and they are more difficult for the researcher to analy z e because the answers must be transcribed, coded, and submitted to some form of qualitative analysis, such as content analysis. The advantage to open-ended items is that they are unbiased and do not provide respondents with expectations of what the researcher might be looking for. Open-ended items are also more valid and more reliable. The disadvantage is that respondents are more likely to skip open-ended items because they take longer to answer. It is best to use open-ended questions when the answer is unsure and for quantities which can easily be converted to categories later in the analysis.

Closed-ended items ask a question and provide a set of response options for participants to choose from. The alcohol item just mentioned is an example, as are the following:

How old are you?

- _____ Under 18

- _____ 18 to 34

- _____ 35 to 49

- _____ 50 to 70

- _____ Over 70

On a scale of 0 (no pain at all) to 10 (worst pain ever experienced), how much pain are you in right now?

Have you ever in your adult life been depressed for a period of 2 weeks or more?

Closed-ended items are used when researchers have a good idea of the different responses that participants might make. They are also used when researchers are interested in a well-defined variable or construct such as participants’ level of agreement with some statement, perceptions of risk, or frequency of a particular behaviour. Closed-ended items are more difficult to write because they must include an appropriate set of response options. However, they are relatively quick and easy for participants to complete. They are also much easier for researchers to analyze because the responses can be easily converted to numbers and entered into a spreadsheet. For these reasons, closed-ended items are much more common.

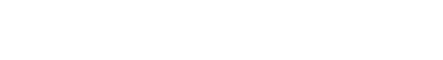

All closed-ended items include a set of response options from which a participant must choose. For categorical variables like sex, race, or political party preference, the categories are usually listed and participants choose the one (or ones) that they belong to. For quantitative variables, a rating scale is typically provided. A rating scale is an ordered set of responses that participants must choose from. Figure 9.2 shows several examples. The number of response options on a typical rating scale ranges from three to 11—although five and seven are probably most common. Five-point scales are best for unipolar scales where only one construct is tested, such as frequency (Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, Always). Seven-point scales are best for bipolar scales where there is a dichotomous spectrum, such as liking (Like very much, Like somewhat, Like slightly, Neither like nor dislike, Dislike slightly, Dislike somewhat, Dislike very much). For bipolar questions, it is useful to offer an earlier question that branches them into an area of the scale; if asking about liking ice cream, first ask “Do you generally like or dislike ice cream?” Once the respondent chooses like or dislike, refine it by offering them one of choices from the seven-point scale. Branching improves both reliability and validity (Krosnick & Berent, 1993) [7] . Although you often see scales with numerical labels, it is best to only present verbal labels to the respondents but convert them to numerical values in the analyses. Avoid partial labels or length or overly specific labels. In some cases, the verbal labels can be supplemented with (or even replaced by) meaningful graphics. The last rating scale shown in Figure 9.2 is a visual-analog scale, on which participants make a mark somewhere along the horizontal line to indicate the magnitude of their response.

What is a Likert Scale?

In reading about psychological research, you are likely to encounter the term Likert scale . Although this term is sometimes used to refer to almost any rating scale (e.g., a 0-to-10 life satisfaction scale), it has a much more precise meaning.

In the 1930s, researcher Rensis Likert (pronounced LICK-ert) created a new approach for measuring people’s attitudes (Likert, 1932) [8] . It involves presenting people with several statements—including both favourable and unfavourable statements—about some person, group, or idea. Respondents then express their agreement or disagreement with each statement on a 5-point scale: Strongly Agree , Agree , Neither Agree nor Disagree , Disagree , Strongly Disagree . Numbers are assigned to each response (with reverse coding as necessary) and then summed across all items to produce a score representing the attitude toward the person, group, or idea. The entire set of items came to be called a Likert scale.

Thus unless you are measuring people’s attitude toward something by assessing their level of agreement with several statements about it, it is best to avoid calling it a Likert scale. You are probably just using a “rating scale.”

Writing Effective Items

We can now consider some principles of writing questionnaire items that minimize unintended context effects and maximize the reliability and validity of participants’ responses. A rough guideline for writing questionnaire items is provided by the BRUSO model (Peterson, 2000) [9] . An acronym, BRUSO stands for “brief,” “relevant,” “unambiguous,” “specific,” and “objective.” Effective questionnaire items are brief and to the point. They avoid long, overly technical, or unnecessary words. This brevity makes them easier for respondents to understand and faster for them to complete. Effective questionnaire items are also relevant to the research question. If a respondent’s sexual orientation, marital status, or income is not relevant, then items on them should probably not be included. Again, this makes the questionnaire faster to complete, but it also avoids annoying respondents with what they will rightly perceive as irrelevant or even “nosy” questions. Effective questionnaire items are also unambiguous ; they can be interpreted in only one way. Part of the problem with the alcohol item presented earlier in this section is that different respondents might have different ideas about what constitutes “an alcoholic drink” or “a typical day.” Effective questionnaire items are also specific , so that it is clear to respondents what their response should be about and clear to researchers what it is about. A common problem here is closed-ended items that are “double barrelled.” They ask about two conceptually separate issues but allow only one response. For example, “Please rate the extent to which you have been feeling anxious and depressed.” This item should probably be split into two separate items—one about anxiety and one about depression. Finally, effective questionnaire items are objective in the sense that they do not reveal the researcher’s own opinions or lead participants to answer in a particular way. Table 9.2 shows some examples of poor and effective questionnaire items based on the BRUSO criteria. The best way to know how people interpret the wording of the question is to conduct pre-tests and ask a few people to explain how they interpreted the question.

| B—Brief | “Are you now or have you ever been the possessor of a firearm?” | “Have you ever owned a gun?” |

| R—Relevant | “What is your sexual orientation?” | Do not include this item unless it is clearly relevant to the research. |

| U—Unambiguous | “Are you a gun person?” | “Do you currently own a gun?” |

| S—Specific | “How much have you read about the new gun control measure and sales tax?” | “How much have you read about the new sales tax?” |

| O—Objective | “How much do you support the new gun control measure?” | “What is your view of the new gun control measure?” |

For closed-ended items, it is also important to create an appropriate response scale. For categorical variables, the categories presented should generally be mutually exclusive and exhaustive. Mutually exclusive categories do not overlap. For a religion item, for example, the categories of Christian and Catholic are not mutually exclusive but Protestant and Catholic are. Exhaustive categories cover all possible responses.

Although Protestant and Catholic are mutually exclusive, they are not exhaustive because there are many other religious categories that a respondent might select: Jewish , Hindu , Buddhist , and so on. In many cases, it is not feasible to include every possible category, in which case an Other category, with a space for the respondent to fill in a more specific response, is a good solution. If respondents could belong to more than one category (e.g., race), they should be instructed to choose all categories that apply.

For rating scales, five or seven response options generally allow about as much precision as respondents are capable of. However, numerical scales with more options can sometimes be appropriate. For dimensions such as attractiveness, pain, and likelihood, a 0-to-10 scale will be familiar to many respondents and easy for them to use. Regardless of the number of response options, the most extreme ones should generally be “balanced” around a neutral or modal midpoint. An example of an unbalanced rating scale measuring perceived likelihood might look like this:

Unlikely | Somewhat Likely | Likely | Very Likely | Extremely Likely

A balanced version might look like this:

Extremely Unlikely | Somewhat Unlikely | As Likely as Not | Somewhat Likely | Extremely Likely

Note, however, that a middle or neutral response option does not have to be included. Researchers sometimes choose to leave it out because they want to encourage respondents to think more deeply about their response and not simply choose the middle option by default. Including middle alternatives on bipolar dimensions is useful to allow people to genuinely choose an option that is neither.

Formatting the Questionnaire

Writing effective items is only one part of constructing a survey questionnaire. For one thing, every survey questionnaire should have a written or spoken introduction that serves two basic functions (Peterson, 2000) [10] . One is to encourage respondents to participate in the survey. In many types of research, such encouragement is not necessary either because participants do not know they are in a study (as in naturalistic observation) or because they are part of a subject pool and have already shown their willingness to participate by signing up and showing up for the study. Survey research usually catches respondents by surprise when they answer their phone, go to their mailbox, or check their e-mail—and the researcher must make a good case for why they should agree to participate. Thus the introduction should briefly explain the purpose of the survey and its importance, provide information about the sponsor of the survey (university-based surveys tend to generate higher response rates), acknowledge the importance of the respondent’s participation, and describe any incentives for participating.

The second function of the introduction is to establish informed consent. Remember that this aim means describing to respondents everything that might affect their decision to participate. This includes the topics covered by the survey, the amount of time it is likely to take, the respondent’s option to withdraw at any time, confidentiality issues, and so on. Written consent forms are not typically used in survey research, so it is important that this part of the introduction be well documented and presented clearly and in its entirety to every respondent.

The introduction should be followed by the substantive questionnaire items. But first, it is important to present clear instructions for completing the questionnaire, including examples of how to use any unusual response scales. Remember that the introduction is the point at which respondents are usually most interested and least fatigued, so it is good practice to start with the most important items for purposes of the research and proceed to less important items. Items should also be grouped by topic or by type. For example, items using the same rating scale (e.g., a 5-point agreement scale) should be grouped together if possible to make things faster and easier for respondents. Demographic items are often presented last because they are least interesting to participants but also easy to answer in the event respondents have become tired or bored. Of course, any survey should end with an expression of appreciation to the respondent.

Key Takeaways

- Responding to a survey item is itself a complex cognitive process that involves interpreting the question, retrieving information, making a tentative judgment, putting that judgment into the required response format, and editing the response.

- Survey questionnaire responses are subject to numerous context effects due to question wording, item order, response options, and other factors. Researchers should be sensitive to such effects when constructing surveys and interpreting survey results.

- Survey questionnaire items are either open-ended or closed-ended. Open-ended items simply ask a question and allow respondents to answer in whatever way they want. Closed-ended items ask a question and provide several response options that respondents must choose from.

- Use verbal labels instead of numerical labels although the responses can be converted to numerical data in the analyses.

- According to the BRUSO model, questionnaire items should be brief, relevant, unambiguous, specific, and objective.

- Discussion: Write a survey item and then write a short description of how someone might respond to that item based on the cognitive model of survey responding (or choose any item on the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale .

- How much does the respondent use Facebook?

- How much exercise does the respondent get?

- How likely does the respondent think it is that the incumbent will be re-elected in the next presidential election?

- To what extent does the respondent experience “road rage”?

Long Descriptions

Figure 9.1 long description: Flowchart modelling the cognitive processes involved in responding to a survey item. In order, these processes are:

- Question Interpretation

- Information Retrieval

- Judgment Formation

- Response Formatting

- Response Editing

[Return to Figure 9.1]

Figure 9.2 long description: Three different rating scales for survey questions. The first scale provides a choice between “strongly agree,” “agree,” “neither agree nor disagree,” “disagree,” and “strongly disagree.” The second is a scale from 1 to 7, with 1 being “extremely unlikely” and 7 being “extremely likely.” The third is a sliding scale, with one end marked “extremely unfriendly” and the other “extremely friendly.” [Return to Figure 9.2]

Figure 9.3 long description: A note reads, “Dear Isaac. Do you like me?” with two check boxes reading “yes” or “no.” Someone has added a third check box, which they’ve checked, that reads, “There is as yet insufficient data for a meaningful answer.” [Return to Figure 9.3]

Media Attributions

- Study by XKCD CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial)

- Sudman, S., Bradburn, N. M., & Schwarz, N. (1996). Thinking about answers: The application of cognitive processes to survey methodology . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. ↵

- Chang, L., & Krosnick, J.A. (2003). Measuring the frequency of regular behaviors: Comparing the ‘typical week’ to the ‘past week’. Sociological Methodology, 33 , 55-80. ↵

- Schwarz, N., & Strack, F. (1990). Context effects in attitude surveys: Applying cognitive theory to social research. In W. Stroebe & M. Hewstone (Eds.), European review of social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 31–50). Chichester, UK: Wiley. ↵

- Strack, F., Martin, L. L., & Schwarz, N. (1988). Priming and communication: The social determinants of information use in judgments of life satisfaction. European Journal of Social Psychology, 18 , 429–442. ↵

- Schwarz, N. (1999). Self-reports: How the questions shape the answers. American Psychologist, 54 , 93–105. ↵

- Miller, J.M. & Krosnick, J.A. (1998). The impact of candidate name order on election outcomes. Public Opinion Quarterly, 62 (3), 291-330. ↵

- Krosnick, J.A. & Berent, M.K. (1993). Comparisons of party identification and policy preferences: The impact of survey question format. American Journal of Political Science, 27 (3), 941-964. ↵

- Likert, R. (1932). A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology,140 , 1–55. ↵

- Peterson, R. A. (2000). Constructing effective questionnaires . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. ↵

Being tested in one condition can also change how participants perceive stimuli or interpret their task in later conditions.

The order in which the items are presented affects people’s responses.

A questionnaire item that allows participants to answer in whatever way they choose.

A questionnaire item that asks a question and provides a set of response options for participants to choose from.