From Gender Equality to Racial Equality

More on this subject.

Event International Conference of the Memory of the World Programme, incorporating the 4th Global Policy Forum 28 October 2024 - 29 October 2024

Other recent news

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Race and gender intersectionality and education.

- Venus E. Evans-Winters Venus E. Evans-Winters Illinois State University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.1345

- Published online: 23 February 2021

When recognizing the cultural political agency of Black women and girls from diverse racial and ethnic, gender, sexual, and socioeconomic backgrounds and geographical locations, it is argued that intersectionality is a contributing factor in the mitigation of educational inequality. Intersectionality as an analytical framework helps education researchers, policymakers, and practitioners better understand how race and gender intersect to derive varying amounts of penalty and privilege. Race, class, and gender are emblematic of the three systems of oppression that most profoundly shape Black girls at the personal, community, and social structural levels of institutions. These three systems interlock to penalize some students in schools while privileging other students. The intent of theoretically framing and analyzing educational problems and issues from an intersectional perspective is to better comprehend how race and gender overlap to shape (a) educational policy and discourse, (b) relationships in schools, and (c) students’ identities and experiences in educational contexts. With Black girls at the center of analysis, educational theorists and activists may be able to better understand how politics of domination are organized along other axes such as ethnicity, language, sexuality, age, citizenship status, and religion within and across school sites. Intersectionality as a theoretical framework is informed by a variety of standpoint theories and emancipatory projects, including Afrocentrism, Black feminism and womanism, critical race theory, queer theory, radical Marxism, critical pedagogy, and grassroots’ organizing efforts led by Black, Indigenous, and other women of color throughout US history and across the diaspora.

- intersectionality

- Black girls

- girls of color

- Black feminism

Intersectionality as a Mitigating Framework and Analytical Tool

The complexity exists; interpreting it remains the unfulfilled challenge for Black women intellectuals. — Patricia Hill Collins ( 1990 , p. 229)

Intersectionality is a theoretical framework and mode of analysis used to understand the multifarious ways race, class, gender, and other social categories overlap and intersect with one another to shape individuals’ and groups’ perspectives and collective experiences. In this article, Black girls are centered in the discussion on the possibilities of intersectionality for educational policy and discourse. Kimberlé Crenshaw ( 1989 ) first coined the term intersectionality to accentuate how racism in employment excluded Black women in ways that diverged from that of Black men, and at the same time, sex discrimination in employment manifested in the lives of Black women’s differently than it did for White women. Similarly, Black girls’ experiences in schools are simultaneously similar yet different from the experiences of Black boys; and Black girls’ schooling experiences unfold differently from that of White girls.

Although ideologically the concept of intersectionality has been a part of Black women’s onto-epistemology (see Barad, 1999 , for discussion on onto-epistemology and agential realism) for centuries, in the post-civil rights era, scholars have been considering the role and implications of intersectionality in theories, methodologies, and approaches to praxis in K-12 education. Suffice it enough to say here, Black feminists and other feminists of color in social science disciplines have a tradition of grappling with race and gender in academia (Perkins, 1993 ; Mirza, 2014 ; Evans-Winters, 2015 ). For this discussion, the usefulness of intersectionality and other related paradigms proffered by women of color will be considered with Black girls in mind.

The intent of theoretically framing and analyzing educational problems and issues from an intersectional perspective is to better comprehend how race and gender overlap to shape (a) educational policy and discourse, (b) relationships in schools, and (c) students’ identities and experiences in educational contexts. First, by placing Black girls’ at the center of analysis, it becomes obvious who is erased from so-called progressive education reforms. Second, situating Black girls at the center of the analysis seeks to combat both historical amnesia of the role of Black women’s thought in theorizings of intersectionality and begin to (re)locate Black girl students in educational theory and discourse. One of the biggest challenges critical theorists face in education is the assumption that educational policy, discourse, and concepts are neutral, and therefore, germane to all students. Another challenge is the erasure of Black women’s contribution to social theory and Black girls’ agency in the face of politics of domination. Following a brief historical contextualization of intersectionality, throughout the discussion an overview of intersectionality is put forth to illuminate the significance of race and gender in educational policy and discourse.

Intersectionality is a term that is becoming more widely used in education scholarship and discourse. Because of the wide use of intersectionality in academic parlance, more people are claiming to be “intersectional” or assume that there is a shared understanding of what intersectionality means and what it entails. First, people are not intersectional; instead theoretical perspectives and interpretations of the social world are intersectional. Second, like with most standpoint theories, without a critical examination of the socio-political aims of the theory (i.e., intersectionality), those who embrace intersectionality for its criticality or as a tool of resistance will fail to meaningfully serve and protect the exact groups from which the critical framework and praxis derived.

For the purposes of this discussion, an explication of intersectionality is offered with Black girls at the center of the analysis. Public education in a democracy is arguably a mitigating factor in social inequity. When recognizing the cultural political authority of Black women and girls from diverse racial and ethnic, gender, sexual, and socioeconomic backgrounds and geographical locations, it is argued that intersectionality is a contributing factor in the mitigation of educational inequality. Intersectionality as an analytical framework helps education researchers to better understand how race and gender intersect to “derive varying amounts of penalty and privilege” (Collins, 1990 , p. 226). Race, class, and gender are emblematic of the three systems of oppression that most profoundly shape Black girls at the personal, community, and social structural levels of institutions (e.g., schools, religion, judicial, workplace, and so on). These three systems interlock to penalize some students in schools while privileging others.

With Black girls at the center of analysis, educational theorists and activists may be able to better understand how “politics of domination” (hooks, 1989 , p. 19) are organized along other axes like ethnicity, language, sexuality, age, citizenship status, and religion within and across school sites. Intersectionality as a theoretical framework is informed by a variety of standpoint theories and emancipatory projects, including Afrocentrism, Black feminism and womanism, critical race theory, queer theory, radical Marxism, critical pedagogy, and grassroots’ organizing efforts led by Black, Indigenous, and other women of color throughout US history and across the diaspora.

An example of Black women’s early protestations against subjugation in all of its forms is when in 1863 Sojourner Truth ( 1851 ) proclaimed, “Ain’t I a Woman” at the Women’s Convention in Akron, Ohio. At the convention, Sojourner Truth illustrated the ways in which African women were rendered invisible in debates about both Black citizenship and deliberations on women’s suffrage. Speaking as both an African and a woman, Sojourner Truth openly professed how she bared the harsh physical labors enforced on all enslaved people, regardless of gender; and expectantly performed the gender roles assigned to women without being accorded the privileges and sanctity of White womanhood, including the privilege of being able to protect, rear, and care for her own children. The interlocking oppressions of racism and sexism rendered her to a subordinated position in both the private and public spheres, and simultaneously, as a Black woman at once vulnerable and scrupulously formidable.

Enslaved African girls endured the harsh realities of physical labor, beatings, rape, racial terror, and having their offspring stolen away from them. Girls of African ancestry, undoubtedly, learned early on in US history their quandary as Black people and as girls under White supremacy patriarchal rule. Throughout abolitionism and the women’s suffrage movement, Black women actively participated in political campaigns against chattel slavery, White racial terrorism, and the political disenfranchisement of Black people; and Black women simultaneously created their own or collaborated with women suffragists’ organizations (Davis, 1981 ; hooks, 1981 ). Like Sojourner Truth, Black women understood that their freedom was grounded in both Black people’s full citizenship rights and women’s enfranchisement.

Throughout the times of the transatlantic slave trade, chattel slavery, and slave revolts, and the Jim Crow Lynching period, Black women conscientiously chose to struggle alongside Black men to protect themselves, Black men, and children. Notwithstanding, during the suffrage era, Black women did not take for granted the importance of the vote for all women and gender equality under the law. Their plight was fundamentally tied to that of both Black men and White women. Socially located at the nexus of race and gender politics of domination, Black women’s modalities of political activism as a matter of course had to be intersectional. Intersectionality as a mode of analysis synchronously represents Black women’s multiple consciousness as raced and gendered subjects as well as Black women’s conscious strategies for navigating socio-political forces.

How can intersectionality help education activists unveil the multiple realities of Black girls while drawing upon Black girls’ ways of knowing to solve education problems? Pertinently, how does either/or theoretical constructs complicate the struggles of Black girls in their schools? “Either you fight on the side of racial justice or you fight on the side of gender justice,” is a common retort young Black women social justice advocates in education hear. Intersectionality calls for a “both/and conceptual lens of the simultaneity of race, class, and gender oppression and of the need for a humanist vision of community” (Collins, 1990 , p. 221). A humanist vision of community will include (re)imagining school communities as spaces that contribute to human freedom and progress for all students.

Moreover, keeping in mind historical and contemporary forms of Black women’s political activism, intersectionality is also a useful framework for better understanding the ways in which Black girls cope with and resist race and gender domination inside and outside schools, and how they come to develop a collective consciousness. As Evans-Winters ( 2011 ) illustrated, Black girls attended school in a district that systematically underserved Black students and students from poor families for generations. Further, it was reported that at school Black girls were perceived as less attractive, less intelligent, and more aggressive than White middle-class girls.

However, Black girls in the study and the women in their lives recognized the need to view girls from working-class neighborhoods as members of the Black community and as girls with distinct cultural and education needs. From their perspective, Black girls required education prevention and intervention programs that were gender and culturally responsive. School resilience was fostered among Black girls who received support simultaneously from Black women caregivers, Black women role models at school and in their communities.

Simultaneously, the adult social actors in the students’ lives understood the significance of race and gender in the formulation of a positive student identity and achieving self-actualization. The study mentioned utilized Black feminist theory to attempt to grasp how race, class, and gender intersected to impede on the schooling experiences of Black girls. As evidenced in the cited study, Evans-Winters ( 2011 ), an intersectional analysis recognizes and advocates for processes and relationships that foster resilience, culturally responsive resistance to structural inequality, and collective action to change inequitable school structures.

Collective Responsibility and Intersectionality

Attenuated concentration on individual responsibility and motivation in the face of adversity is endemic of Eurocentric western philosophies of individualism and liberal feminism’s focus on personal autonomy which is diametrically opposed to Black feminism’s ethos of care and community (Lane, 2018 ). Intersectional conversations on vulnerability and resilience studied within a socio-cultural context are important epistemological shifts in education research that regularly ignores the racialized and gendered experiences of Black girls in schools, pathologizes the Black community, and generally deems Black students somehow culturally deficient or intellectually inferior to their White counterparts. Meanwhile, the theorization of Black girls’ schooling experiences is lost in the shuffle as race scholars push for anti-racist policies and feminists advocate for gender-based school policies.

In these dichotomous approaches to school reform policy, all the girls are White, and all the Blacks are boys . For example, President Barack Obama gave unprecedented attention to the educational neglect of Black boys during his tenure as the first Black commander-in-chief of one of the world’s most powerful nations, and a nation that has been besmirched morally for its history of racial injustice. To address the opportunity gap faced by boys and young men of color, the president implemented the “My Brother’s Keepers” initiative, which focused on a wide range of topics such as mentoring, workforce development, and early literacy programs.

Without a doubt, Black boys and other boys of color who experience relentless structural barriers certainly need policy agendas that serve to protect and advocate for their developmental needs. Nonetheless, some saw this initiative as a missed opportunity for the first Black president, who with this initiative was clearly forefronting a racial agenda, to also address the egregious education opportunity gaps that girls and young women of color face. For example, compared to their White female peers, Black and Latina girls were more likely to be suspended from school (Inniss-Thompson, 2018 ), Black and Native American girls received harsher discipline for minor offenses and typical childlike behaviors (Onyeka-Crawford, Patrick, & Chaudhry, 2017 ) and/or endured surveillance and harassment for being Black girls (Evans-Winters & GGENY, 2017 ), and disproportionality come in contact more with police after a referral from school authority (Morris, 2016 ).

In the case of private and public initiatives like “My Brother’s Keeper,” the assumption is that if boys and men of color were okay, then girls would benefit from the trickle-down effect of boys’ increased education and career opportunities (Crenshaw, 2014 ). Most policy interventions myopically focus on unilateral variables (e.g., race + intervention = an outcome) as opposed to intersecting , multiplicative , and fluctuating variables (race x gender x class x (y) + intervention = outcomes) in students’ lives. Without attention to the multiplicative (Wing, 1997 ) nature of Black girls’ identities, the dynamism of Black girls’ schooling experiences go under-theorized and unexplored.

The purpose of intersectionality, among others, is to facilitate a multidimensional non-binary policy analysis that contemporaneously frame vulnerability and oppression alongside agency and resistance in approaches to educational interventions. First, although many Black girls and women have a commonly shared experience due to the nature of race, class, and gender oppression (and colonial education), it goes without saying that Black girls are not one monolithic or homogenous group. Second, girls of African ancestry represent a multitude of personal and cultural experiences, identities, and social realities. It is from these multiple and co-existing realities that Black girls’ and women’s intersectional praxis emerges.

The Combahee River Collective (CRC, 1983 ) statement written by a group of Black feminists and lesbians gathered in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1977 , captured the multivocality and intersectional framework of Black women’s politics and praxis. Pointedly, the collective called for struggles against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression and critiqued sexual oppression in the Black community and racism within the mainstream feminist movement.

In their articulation of the intersection of multiple oppressions (and admittance that tokenism accorded some Black women more privilege), CRC set the contemporary tone for Black women’s organizing efforts. Specifically, they asserted that racial politics and racism are pervasive factors in Black women’s lives, and sexual politics and patriarchy are as pervasive as class and race. They also collectively rejected the stance of lesbian separatism and biological determinism. And like Black women activists before them, they called for political work in coalition with other progressive movements and organizations with similar interests to dismantle White supremacy, patriarchy, imperialism, and capitalism. Further, they openly proclaimed to be “concerned with any situation that impinges on the lives of women, Third World and working people” (CRC, 1983 , p. 3). Finally, women activists believed that with democratic and non-hierarchal relationships, they could look to their collective knowledge and power to combat the social issues confronting Black women and similarly situated people.

In the contemplation of intersectionality as a tool of analysis, what can be learned from the CRC statement to address educational disparity in the lives of Black girls? The CRC statement calls to mind that Black girls’ realities are constructed by multiple historically intersecting oppressed identities such as race and ethnicity, social class, gender, sexual orientation or gender identity, religion, immigrant status, age, geographical location, language, mental health, (dis)ability, and other social characteristics. How do these same politics play out in the lives of Black school girls who are multiply marginalized? To begin with, data from the Educational Policy Institute recently suggests that Black girls are more likely than their White peers to attend schools highly segregated by race and ethnicity and to attend high poverty economically segregated schools, which places them at greater risk of school underperformance (García, 2020 ).

Furthermore, using data from the Office of Civil Rights, the National Women’s Justice Institute discovered that although White girls were more likely to be bullied or harassed on the basis of sex, Black girls were more likely to report being bullied or harassed on the basis of race (Inniss-Thompson, 2018 ). Ironically, more girls were disciplined for bullying based on sex than they were for bullying based on race (Inniss-Thompson, 2018 ). Once again, Black girls’ needs for protection were not considered. If the plight of Black girls in schools is analyzed from an intersectional perspective, the intricacies (as called out in the CRC statement) of Black girls’ identities begin to reveal themselves.

For example, in 2013–2014 , nearly 10% of Black girls were subjected to out-of-school suspension, compared to only 2% of White female students, according to most recently reported data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES, 2017 ). In that same school year, Black and Native American girls were more likely than any other group of girls to receive corporal punishment at school, to receive one or more suspension or expulsion from school, and/or to be referred to law enforcement. Black girls were also more likely to be involved with a school-related arrest (NCES, 2017 ). And Black girls with a disability were multiply jeopardized by their disability status; in many cases, following their Black boy peers, these girls had higher rates of one or more in-school and out-of-school suspensions than boys and girls of other races and ethnicities and ability groups (NCES, 2017 ). Being poor, Black, and a girl with a disability unveils how interlocking systems of oppression impedes on Black girls’ educational opportunities and treatment in schools. Girls of color with a disability are an invisible minority overlooked and rendered as non-citizens with no consideration for self-determination (Erevelles & Minear, 2010 ).

Heterosexism also plays a role in harsh school punishment. In fact, evidence suggests that Black girls are punished in schools for non-conformity to gender role stereotypes, which are grounded in White middle-class heteronormative notions of femininity (see Crenshaw, Ocen, & Nanda, 2015 ; Morris, 2012 ). For instance, in 2020 , a GLSEN and the National Black Justice Coalition (NBJC) report found that nearly half of Black LGBTQ students (44.7%) experienced some form of school discipline, such as detention, out-of-school suspension, or expulsion; over half of Black LGBTQ students (51.6%) felt unsafe at school because of their sexual orientation, 40.2% because of their gender expression, and 30.6% because of their race or ethnicity; and many Black LGBTQ students experienced harassment or assault at school based on personal characteristics, including sexual orientation (65.1%), gender expression (57.2%), and race and ethnicity (51.9%) (Truong, Zongrone, & Kosciw, 2020 ).

Societal perceptions of Black people and women undoubtedly affect the treatment of Black girls in schools, but anti-discrimination policies neglect to devise reforms that explicitly address the unique discrimination that Black girls endure at the juncture of race and gender. For example, anti-discrimination policies, such as efforts to reform school-based discipline policies fail to account for students who are members of multiple social categories. Most education policy, including the 2015 reauthorized Every Student Succeed Act (ESSA), fails to not only recognize students’ multiple intersecting social identities, but also acknowledge how the intersection of multiple interlocking identities at the micro level (e.g., interpersonal relationships, classrooms, or districts) reflect multiple and interlocking structural (macro) inequality at the larger societal level.

Although the policy called for the protection of racial minorities students, students with a disability, or lower-income students for example, it did not require administrators to put special protocols in place to protect Black girls specifically from unfair discipline policies that disproportionately affect Black students (e.g., longer out-of-school suspensions) and those that disproportionately affect girls (e.g., dress code violations). Consequentially, these same anti-discrimination policies do not offer an accountability and transparency process for documenting the unique discrimination that Black schoolgirls encounter.

Intersectionality of Race and Gender in Education: For the Some of Us Who Are Brave

Racism, sexism, and classism at the societal level permeates throughout all levels of the education system, and conversely, schooling processes reproduce social inequality. Even though federal and state education policy serve to protect students from racial discrimination and gender discrimination, anti-discrimination policies fail to understand how Black girls’ multiple identities crisscross to leave them susceptible to the racism and sexism and other forms of oppression. Society’s deeply entrenched stereotypes and controlling images of Black women, Black children, and Black people all together along with societal expectations of girls and women in general transverse to shape school actors’ perceptions of Black girls.

Historically, for instance, young Black women were valued as producers of future labor (as an enslaved woman giving birth to future “profits”), domestic workers or “the help” (e.g., nanny, housecleaner, or cook), and objects of desire (e.g., singer, dancer, or sex worker). Infiltrating social institutions (e.g., education, law, or science) and propaganda (i.e., print, visual, and social media), dominating culture engrains into the psyche of society images and narratives of the oppressed that serve to continue to promote and sustain the dominating culture’s ideals, perceptions, and norms to maintain its power. Accepting the notion that White supremacy and eugenics science established its roots into all levels of education, intersectionality unveils how contemporary forms of racial violence play out in educational settings to uniquely impact Black girls who exist at the intersection of race, class, and gender oppression.

An intersectional framework allows educators to better comprehend the complex and multilayered ways schools reflect and reproduce societal inequality as well as conceptualize, critically analyze, and generate policies that are more inclusive. Intersectionality as an analytical framework recognizes that identities are mutually interlocking as well as relational (Berger & Guidroz, 2009 ). In educational policy and discourse with Black girls in mind, intersectionality is ideal for capturing how multiple identities intersect and interact to (a) inevitably and distinctly shape Black girls’ experiences in schools, (b) their relationships with school authority, (c) academic achievement, (d) beliefs about schooling, and (e) their student identity.

The core ideas of intersectionality are social inequality, power, relationality, social context, complexity, and social justice (Collins & Bilge, 2016 ). Collins and Bilge ( 2016 ) explained that “Intersectionality is a way of understanding and analyzing the complexity in the world, in people, and in human experiences,” and they further asserted, “Intersectionality as an analytic tool gives people better access to the complexity of the world and of themselves” (p. 2). Drawing upon these core ideas of intersectionality and placing Black girls at the center of an intersectional analysis, education scholars are easily able to recognize how social factors, such as de facto school segregation, housing inequality, pay inequity, mass policing in poor and Black neighborhoods, sexual violence, racial terrorism, and inequity in the healthcare system, collude to distinctly shape Black girls’ personally and as a social group.

Existing at the nexus of Black and girl, and possibly multiple other social categories (e.g., poor, queer, immigrant, and so on), Black girls experience multiple realities across social contexts. How can scholars and social justice advocates adopt intersectionality as a framework and analytical tool to mitigate and interrupt dehumanizing school practices, deculturalization, and the perpetuation of social inequality? In the case of Black girls, an intersectional analysis unveils (a) some taken-for-granted assumptions (and politics) about singular social categories, (b) the presumed symbiotic nature of human relationships in schooling and education, and (c) how power and domination permeates all aspects of society, including education.

Once the education problem can be located within its socio-cultural context(s), the education problem can be solved more justly. Traditional conceptualizations of racial and gender identity theorized individuals’ and social groups’ identities as additive and ordinal, with one primary identity influencing access and opportunities. Consequently, even critical theories of education that grappled with cultural hegemony and dehumanization processes imagined social identities to be additive or ordinal as opposed to interlocking, dynamic, and complex. Black schoolgirls social identities fall along a continuum, and simultaneously in multiple locations, in systemic stratification.

Intersectionality provides more comprehensive insight into how multiply situated identities positions students’ proximity to power and authority differently. Intersectionality is an ethical intercession for meditating asymmetrical relationships in educational settings and to promote more equitable relationships and inclusive learning spaces.

Furthermore, intersectionality in its contemporary form was proliferated via critical race feminism as a legal theory (Wing, 1997 ). Critical race feminism entailed contending with race, gender, and justice, and concurrently imaginings of racial liberation, gender equity, and cultural emancipation(s). With a focus on justice, intersectionality as theory and praxis requires an examination of how Black women, Indigenous women, and other people of color navigate social systems, interpret the social world, and resist oppression. There is a tradition of devaluation and erasure of Black women’s and other women of color’s intellectual labor and cultural productions in seemingly liberal institutions, including K-12 schools, higher education, and even in women-serving organizations.

The so-called “browning of America” has not equated to the browning or decolonization of curriculum, pedagogy, or policy. Intersectionality advances critical race feminists’ attempts to identify, acknowledge, and center the long tradition of women of color’s cultural knowledge and intuition in pursuits of educational equity. Education scholars, too, have a responsibility to examine how Black girls not only persist in schools, but also draw upon their own cultural knowledge and intuition to form a unique student identity and collective consciousness as a form of resistance in the face of hegemony.

Although intersectionality centers the experiences of the marginalized, it also prompts critical self-reflection for all involved in the educational process, including Black girls, researchers interested in the lives of Black girls, and policymakers. How does race, class, and gender influence how education scholars perceive educational problems, which education issues are worth exploring, and who, according to scholars, should be protected in schools? To seek and think more intersectionally, there is a need for collaborative research with Black girls and other girls of color that studies education from their perspective.

In these collaborative relationships, raising youth’s and people’s own collective consciousness while also participating in self-reflexivity throughout interactions with Black girls is sought. From an intersectional approach, the purpose of collaborative research projects is to: (a) create opportunities for coalition building; (b) facilitate more symmetrical relationships with student participants; and (b) contemplate ways to mediate or combat oppressive schooling. These social justice pursuits must draw upon girls’ and Black women’s multiple ways of knowing the social world and performing culture (Brown, 2013 ) with the intent to collaborate with girls and young women to generate more socially just educational policy and programs.

Future Implications of Intersectionality in Education

Reflecting on the critical stance of intersectionality and the tenets of Black feminism, racism and sexism are normal and deeply entrenched in education policy and discourse. Racism and sexism affect relationships and practices inside and outside schools; and both are recycled and re-consumed in school practices and beliefs, co-constructing new generations of racialized and gendered subjects. Born out of Black feminism, intersectionality as a theoretical framework and analytical tool is critical to the continual development of Black women’s and other women of color’s socio-political thought as well as critical theory in general. Knowledge is constructed through collective meaningful contemplation, and in the case of Black women, in the face of marginalization and systematic oppression.

In agreement with critical race feminist Crenshaw ( 1995 ), “Because women of color experience racism in ways not always the same as experienced by men of color and sexism in ways not always paralleled to experiences of white women, antiracism and feminism are limited, even on their own terms” (p. 360). For Black girls, intersectionality is a way of life, a way of seeing the world, and a way of navigating the social world. Born out of oppositional knowledge and standpoint theory, intersectionality concerns itself with power and privilege as much as it does with the ways in which women of color resist various forms of oppression. As a theoretical framework, intersectionality takes on an interdisciplinary approach that draws upon historical knowledge (from the vantage point of the marginalized and oppressed), psychology, cultural studies, gender and ethnic studies, the humanities, economics, and legal theory (e.g., critical race theory and feminism). Finally, after placing Black girls’ school experiences at the center of the analysis, the usefulness of intersectionality for grappling with race and gender in education is summarized as follows:

Intersectionality as a theoretical lens and tool of analysis reveals that Black girls’, Indigenous girls, and other girls of color’s schooling experiences are distinct from that of boys of color and White girls;

Intersectionality born out of Black women’s and other women of color’s praxis centers the lived experiences of girls of color who are confronted by multiple forms of oppression, due to the mutually interlocking identities of race and ethnicity, gender, social class, age, and other social factors within an education system that privileges and sustains White supremacy patriarchy capitalism;

Intersectionality recognizes the multiple identities, collective, and personal knowledge, and cultural intuition that Black girls possess and rely on in their daily lives; this knowledge informs efforts to confront gender and racial domination.

Intersectionality is multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary in knowledge pursuits;

Intersectionality as a theoretical framework privileges girls’ and women of color’s histories and narratives to contextualize the dynamics and resourcefulness of gender and racial domination in the lives of women and girls of color;

Intersectionality as an analytical framework synchronously excogitate upon racial and gender oppression alongside women’s and girls’ strategies of resistance against all forms of oppression.

The student population in the United States is becoming increasingly more diverse and yet many educational practices and policies remain the same. In 2017 , the percentage of US school-age children who identified as Black or African American was at 15% (a 2% decrease). Meanwhile, between 2000 and 2017 , the percentage of school-age children from other racial and ethnic groups increased. Specifically, Latinx children increased from 16 to 27%; Asian children increased from 5 to 7%; and children of two or more racial identities increased from 4 to 6%. In that same period, the percentage of White children decreased from 61 to 48%. The percentage of school-age American Indians and Alaska Natives remained at 1%, and the percentage of Pacific Islanders remained at less than 1%% during this time (NCES, 2019 ). As US student population becomes more racially and ethnically diverse, the teaching force is becoming whiter (DOE, 2016 ). With Black girls making up nearly 16% of the student population, the lack of teacher diversity puts Black girls at greater risk of race and gender discrimination. With the noted demographic shifts, as well as the current waves of health pandemic and national protest, in mind, intersectionality as an analytical framework, born out of Black women’s, Indigenous women, and other women of color’s onto-epistemology, is an entry point for radically reimagining how educational research, policies, and pedagogies can reflect the multiple realities of Black girls, and thus, protect them.

Further Reading

- Blake, J. J. , Butler, B. R. , Lewis, C. W. , & Darensbourg, A. (2011). Unmasking the inequitable discipline experiences of urban Black girls: Implications for urban educational stakeholders. Urban Review , 43 (1), 90–106.

- Brown, R. N. (2009). Black girlhood celebration: Toward a hip-hop feminist pedagogy . New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Collins, P. H. (2005). Black sexual politics: African Americans, gender, and new racism . New York, NY: Routledge.

- Crenshaw, K. W. (1995). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women’s of color. In K. Crenshaw , N. Gotanda , G. Peller , & K. Thomas (Eds.), Critical race theory (pp. 357–383). New York: The New Press.

- Edwards, E. B. , & Esposito, J. (2019). Intersectional analysis as a method to analyze popular culture: Clarity in the matrix . New York. NY: Routledge.

- Epstein, R. , Blake, J. J. , & Gonzalez, T. (2017). Girlhood interrupted: The Erasures of Black girls childhood . Georgetown Law.

- Evans-Winters, V. E. (Ed.). (2015). Black feminism in education: Black women speak back, up, and out . New York: Peter Lang.

- Evans-Winters, V. E. (2019). Black feminism in qualitative inquiry: A mosaic for writing our daughter’s body . New York: Routledge.

- Heitzeg, N. A. (2009). Education or incarceration: Zero tolerance policies and the school to prison pipeline. Forum on Public Policy Online , 2 .

- Morris, M. W. (2019). Sing a rhythm, dance a blues: Education for the Liberation of Black and Brown Girls . New York, NY: The New Press.

- Morris, M. W. (2016). Pushout: The criminalization of Black girls in schools . New York, NY: The New Press.

- Winn, M. (2010). “Betwixt and between”: Literacy, liminality, and the “celling” of Black girls. Race, Ethnicity, and Education , 13 (4), 425–447.

- Barad, K. (1999). Agential realism: Feminist interventions in understanding scientific practices. The Science Studies Reader , 1–11.

- Guidroz, K. , & Berger, M. T. (2009). A conversation with founding scholars of intersectionality. In K. Crenshaw , N. Yuval-Davis , & M. Fine (Eds.), The intersectional approach: Transforming the academy through race, class, and gender (pp. 61–78). Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Brown, R. N. (2013). Hear our truths: The creative potential of Black girlhood . Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

- Collins, P. H. (1990). Black feminist thought in the matrix of domination . Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment , 138 , 221–238.

- Collins, P. H. , & Bilge, S. (2016). Intersectionality . Cambridge, MA: Polity Press.

- Collins, P. H. (1999). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment . New York: Routledge.

- CRC (Combahee River Collective) . (1983). The Combahee river collective statement .

- Crenshaw, K. W. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal forum , 140 (1), 139–167.

- Crenshaw, K. W. (2014, July 29). The girls Obama forgot . New York Times .

- Crenshaw, K. W. , Ocen, P. , & Nanda, J. (2015). Black girls matter: Pushed out, overpoliced, and underprotected . New York, NY: Center for Intersectionality and Social Policy Studies & African American Policy Forum.

- Davis, A. (1981). Women, Class, and Race . New York, NY: Random House.

- DoE (Department of Education) (2016). The state of racial diversity in the educator workforce . Washington, DC: US Department of Education.

- Erevelles, N. (2002). Voices of silence: Foucault, disability, and the question of self- determination. Studies in Philosophy and Education , 21 (1), 17–35.

- Erevelles, N. , & Minear, A. (2010). Unspeakable offenses: Untangling race and disability in discourses of intersectionality. Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies , 4 (2), 127–145.

- Evans-Winters, V. E. (2011). Teaching black girls: Resiliency in urban classrooms . New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Evans-Winters, V. E. , & GGENY (Girls for Gender Equity New York) . (2017). Flipping the script: The Dangerous bodies of girls of color. Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies , 17 (5), 415–423.

- García, E. (2020). Schools are still segregated, and Black children are paying a price . Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute.

- hooks, b. (1981). Ain’t I a woman: Black women and feminism . Boston, MA: South End Press,

- hooks, b. (1989). Talking back: Thinking feminist, thinking Black . Boston, MA: South End Press.

- Inniss-Thompson, M. N. (2018). Summary of discipline data for girls in U.S. public schools: An analysis from the 2015–2016 U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights Data Collection . Berkeley, CA: National Black Women’s Justice Institute.

- Lane, M. (2018). “For real love”: How Black girls benefit from a politicized ethic of care. International Journal of Educational Reform , 27 (3), 269–290.

- Mirza, H. S. (2014). Decolonizing higher education: Black feminism and the intersectionality of race and gender. Journal of Feminist Scholarship , 7 (7), 1–12.

- Morris, M. (2012). Race, gender and the school-to-prison pipeline: Expanding our discussion to include Black girls . New York, NY: African American Policy Forum.

- NCES (National Center for Educational Statistics) . (2017). Percentage of students receiving selected disciplinary actions in public elementary and secondary schools, by type of disciplinary action, disability status, sex, and race/ethnicity: 2013–14 . Washington, DC: Institute of Education Sciences.

- NCES (National Center for Educational Statistics) . (2019). Racial/ethnic enrollment in public schools . Washington, DC: National Center for Educational Statistics.

- Onyeka-Crawford, K. , Patrick, K. , & Chaudhry, N. (2017). Let her learn: Stopping school pushout for girls of color . Washington, DC: National Women’s Law Center.

- Perkins, L. M. (1993). The role of education in the development of Black feminist thought, 1860–1920. History of Education , 22 (3), 265–275.

- Truong, N. L. , Zongrone, A. D. , & Kosciw, J. G. (2020). Erasure and resilience: The experiences of LGBTQ students of color, Black LGBTQ youth in U.S. schools . New York, NY: GLSEN.

- Truth, S. (1851, December). Ain’t I a woman . Women’s convention in Akron, Ohio.

- Wing, A. K. (Ed.). (1997). Critical race feminism: A reader . New York: New York University Press.

Related Articles

- Gender, Justice, and Equity in Education

- Gender and Sexuality Theory and Research in Education

- Gender Equitable Education and Technological Innovation

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Education. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 26 May 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.66.14.236]

- 185.66.14.236

Character limit 500 /500

Intersectionality: how gender interacts with other social identities to shape bias

Ph.D. Candidate in Psychology, Northwestern University

Disclosure statement

David Miller receives funding from National Science Foundation.

View all partners

Actress Patricia Arquette’s comments at the 2015 Oscars award night drew criticism for implicitly framing gender equality as an issue for straight white women. She insisted that, “It’s time for all the women in America and all the men that love women and all the gay people and all the people of color that we’ve all fought for to fight for us now.”

Among other concerns, critics argued she overlooked the unique challenges faced by queer women, women of color and other women at the intersection of multiple minority groups. This sentiment reflects a growing movement within feminist circles to understand how people simultaneously face bias along multiple identity dimensions such as gender, race, and sexual orientation – an idea called intersectionality.

Social psychologists have recently joined in this movement, but have also reframed the discussion. The politics on intersectionality can “resemble a score-keeping contest between battle-weary warriors,” argued social psychologists Valerie Purdie-Vaughns and Richard Eibach in an influential 2008 review article . “The warriors display ever deeper and more gruesome battle scars in a game of one-upmanship.”

Setting aside these “oppression Olympics,” intersectionality is a fertile area for scientific research, argued Rutgers University psychologist Diana Sanchez at the Society for Personality and Social Psychology ( SPSP ) conference last week. At this academic gathering, intersectionality was a major topic at a daylong session about gender .

Here are three lines of research illustrating how gender interacts with other social identities to shape bias in often surprising ways. People of multiple minority groups face both distinct advantages and disadvantages. Biases based on gender and race do not always simply pile up to create double disadvantages, for instance.

When stereotypes can both help and hurt black women leaders

Women are often viewed negatively for exhibiting traditionally masculine behavior . Assertive female leaders are disliked , while assertive male leaders gain respect , for instance. However, could this distaste for assertive female leaders vary by race?

Unlike white women, black women are often stereotyped as being assertive, confident and not feminine. These masculine traits are not only expected for black women but also allowed , at least in leadership roles, according to research presented at the SPSP conference.

Robert Livingston , lecturer of public policy at Harvard University, presented an experiment about how 84 nonblack participants responded to a corporate executive described as either “tough, determined” or “caring, committed.” The race and gender of the fictitious leader were also varied across conditions.

Both white female and black male leaders were rated more negatively when described as tough rather than caring. In contrast, black women faced no such penalty for behaving assertively and were instead rated similarly to white men. Livingston concluded black women “were able to show dominance, assertiveness, agency without the same penalty that either white women or black men suffered.”

He suggested that white women get knocked for being “tough, determined” because they are expected to be warm and caring. Black men are penalized because they are feared by others and activate other stereotypes such as being dangerous. In contrast, black women are expected to be assertive and confident, unlike white women, and they’re not feared in the same way as black men, Livingston suggested.

Livingston, however, emphasized that these evaluations are complex and likely depend on context. In a follow-up experiment led by Duke University associate professor of management and organizations Ashleigh Rosette , black female leaders were evaluated especially harshly if their corporation had performed poorly during the past five months. Under those conditions, black women were rated more negatively than white women or black men for the exact same business scenario.

If you are a black woman, you can be an assertive leader as long as you don’t make any mistakes, Livingston argued. “But the first time you make a mistake, your competence is called into question well before the white woman or the black man.”

When multiple minority identities render groups invisible

Individuals of multiple minority groups may be overlooked and marginalized for not being prototypical of their respective groups, argued Rebecca Mohr , doctoral psychology student at Columbia University. For instance, white women are seen as prototypical of “women.” Black men are seen as prototypical of “black people.” But black women are seen as neither prototypical of “black people” nor “women,” Mohr argued based on prior research .

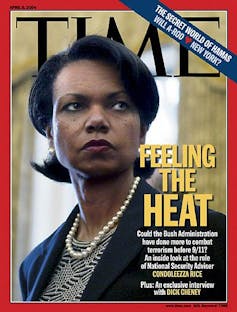

Racial minority women can therefore be rendered metaphorically invisible. Along with Columbia Associate Professor of Psychology Valerie Purdie-Vaughns , Mohr tested whether racial minority women are featured in mass media less frequently than more prototypical others.

In a currently unpublished study, the researchers analyzed covers of Time magazine published from 1980 to 2008. They chose Time because it’s one of the longest-running U.S. publications and is published weekly, offering a large archive of covers. It’s also a general interest magazine, meaning that people on the covers should presumably “appeal to a wide swath of Americans,” Mohr pointed out.

The study found that racial minority women were underrepresented when racial minorities were on the cover of Time . For instance, women were only 20 percent of the covers that featured racial minorities. Conversely, when women were on the cover, racial minority women were underrepresented relative to their share of the U.S. population.

Mohr suggested that these results reflect the broader invisibility of racial minority women in American society. For instance, even though three black queer women started the Black Lives Matter movement , most media attention has focused on black men killed by police. In contrast, black women killed by police such as Meagan Hockaday, Tanisha Anderson and Rekia Boyd are invisible, critics argue .

How gender gaps in STEM participation vary by race

Gender gaps in pursing natural science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields surprisingly sometimes vary by race, noted Laurie O’Brien , associate professor of psychology at Tulane University. Women of color in STEM may sometimes face “ double jeopardy ” because of both racial bias and gender bias in some contexts such as gaining influence over others in academic departments.

However, “double jeopardy” is not the full story, O’Brien argued in her SPSP talk. For instance, when entering college, black women are more likely than white women to intend to major in STEM. Her research shows that black women hold weaker gender-STEM stereotypes than white women, helping explain that difference.

O’Brien also pointed to research by psychologists Monica Biernat and Amanda Sesko about bias favoring male computer engineers . This bias was found only when undergraduates evaluated fictitious white, but not black, employees. Black women were instead evaluated similarly compared to white men.

In one large nationally representative experiment, gender bias in STEM even reversed by race and ethnicity. STEM faculty responded less often to emails from white female than white male prospective graduate students. However, STEM faculty consistently responded more often to Hispanic women than Hispanic men.

O’Brien emphasized these data are complex. For instance, even though black women start out in college more interested in STEM than white women, black women may face unique barriers such as race-based stereotypes to completing college with a STEM degree. In her current research, O’Brien studies how the effects of interventions to bring girls into STEM may vary by race.

Thinking beyond ‘double jeopardy’

This research on intersectionality challenges the simple narrative that prejudices such as sexism and racism always combine to create “double jeopardy.” For instance, racial minority women can be rendered “invisible.” But this invisibility may also protect them in some cases by making them less prototypical targets of common forms of bias.

This research is still in its early stages. For instance, more studies are needed to test how evaluations of black female leaders found in small laboratory experiments generalize to real world settings. Attendees at the SPSP conference also emphasized the need to develop theoretical frameworks that can help explain the nuanced results. The emerging data show that gender can interact with other social identities to shape perceptions and evaluations in complex and often surprising ways.

- Gender stereotypes

- Sexual orientation

- Stereotypes

- Social psychology

- Racial diversity

- Racial Stereotypes

- Intersectionality

Research Fellow

Senior Research Fellow - Women's Health Services

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 13 August 2020

An intimate dialog between race and gender at Women’s Suffrage Centennial

- Mimi Yang 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 7 , Article number: 65 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

40k Accesses

1 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cultural and media studies

Women’s Suffrage Centennial has arrived in a culturally divisive time in the United States as well as in a high-stakes presidential election year. All this is accompanied with the emergence of Black Lives Matter movement on a global-scale in the wake of the African American man George Floyd’s death under the knees of white police officers. In an “I cannot breathe” America at a new cultural awakening moment, is the Centennial a divider or unifier for American women in 2020? This article aims to answer the question by revisiting the 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution and iconic figures like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Frederick Douglass, W.E.B. DuBois, and Mary Church Terrell. In an interdisciplinary approach anchored in both historical and cultural studies, the article scrutinizes the split between the two visceral elements pertinent to cultural identity—gender and race—in Women’s Suffrage Movement, draws a pattern of their intersection, and maps out a “double consciousness” (to borrow W.E.B. DuBois’ term). The article argues that the women’s suffrage movement was indeed a gigantic step towards the American ideal of gender equality but it fell short of racial equality. There is a mixed legacy to embrace and to reevaluate at the same time. Therefore, Women’s Suffrage Centennial should not and cannot be a single-issue gender celebration, nor a one-size-fits-all symphony, but a landmark occasion for an intimate and nuanced dialog between gender and race. The article suggests that the Centennial should not only celebrate white American suffragists, but should be an opportunity to make a historic step to cross the color line that has cutoff African American women, as well as women of color from other races, ethnicities, and heritages from the power center.

Similar content being viewed by others

The East-West dialogue: methodical diversity and frailties of feminist accounts

Back to marx: reflections on the feminist crisis at the crossroads of neoliberalism and neoconservatism, kashmiri women in conflict: a feminist perspective, introduction.

The right to vote defines constitutional citizenship. A century ago, the long-and-hard-fought victory of women’s right to vote culminated with the passage of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution on August 18, 1920, thus completing a full circle of citizenship for woman. She could now vote like her (white) male counterparts as an equal and full citizen. On the surface, this is an indisputable narrative, and in fact, has found its way into textbooks and seeped through the nation’s imagination for a century. However, if the constitutional right to vote is a basic definition of a citizen, women of color were still not able to exercise their full citizenship in 1920 but until 45 years later in the era of the Civil Rights Movement, with the Voting Rights Act of 1965 signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson. As one of the most far-reaching pieces of civil right legislation, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 addressed manmade obstacles that had prevented African Americans and women of color in general from participating in nation’s political life. The 1965 Act eventually removed literacy tests, poll taxes, and requirement of property ownership among other “tactically” designed obstacles at state level, which had effectively stripped away African Americans and other minority individuals’ rightful right to vote. Granted in the 15th Amendment in 1870, voting rights of a citizen of color had not got exercised until 1965. History seems to have given birth to two Americas—the white one at the center, entitled of a “standard” narrative; the non-white one at the periphery, “unfit” to be counted on equal terms. Then, whose centennial of the women’s suffrage movement is this in 2020? Which America is relevant to the landmark event?

Elizabeth J. Clapp summarizes the characteristics of anniversaries of the women’ suffrage movement:

Traditionally, historians viewed the suffrage struggle as part of the history of democracy in the United States, an effort to widen the franchise to all Americans. They wrote organizational histories of the women’s rights movement, centering on the campaign for the vote, and biographers included suffragists among their projects. These pioneering histories paid attention to exceptional women who operated in the male world. They characterized them as white, middle class, and mostly living on the East Coast, which…reflected little of the diversity and regional variation… ( 2007 , p. 238).

It has indeed been a long-standing tradition and a well-accepted standard to celebrate women’s suffrage based on a single-issue of gender, with a group of iconic suffragists—white, middle class, and from the East Coast. The tradition has institutionalized a widespread cultural perception that the women’s suffrage movement is white or WASP (White-Anglo-Saxon-Protestant); a “standard” celebration as such has “reflected little the diversity and regional variation”. So observed Clapp more than a decade ago. In 2020, however, a one-size-fits-all “white” celebration proves to be evidently inadequate, given the twenty-first century demographics, distinctively transformed as opposed to the one a century ago. The centennial of women’s suffrage movement presents a much needed platform to examine these transformations and their impact on the way in which we frame and celebrate each anniversary and now the centennial.

In reviewing Ellen Carol DuBois’ 2020 book Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote , Donna Seaman states, “The story of suffrage in the United States is dramatic, infuriating, paradoxical, and saturated with sexism and racism” (Seaman, 2020 , p. 18). It is not a black or white story but a gray one in different shades at different times. DuBois’ book explores in depth the links of the woman suffrage movement to the abolition of slavery and the complex make-up of “foremothers” of the suffrage movement Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony and Sojourner Truth. DuBois points out, “The women suffrage movement had incredible range. It was sustained and transformed through massive political, social and economic changes in American life and carried forward at least by three generations of American women” (DuBois, 2020 , p. 2). The meaning of the suffrage for American women has thus never been set in stone; it morphs and alters as “hopes and fears for American democracy rise and fall” (p. 1). From the mid-nineteenth century to the Civil War, the Reconstruction, the Progressive Era, the Civil Rights Movement, the threshold of the global age, the post-colonial/post-industrial time, and the digital/informational universe, what means to be an American woman changes, evolves, and transforms. The word “woman” no longer signifies a white archetypal female who represents all female individuals. Because of demographic changes, sociopolitical transformations, and economic reconfigurations, women’s suffrage victory has never unfolded as a straightforward line, but we are taught to grasp it as a single-issue binary of women-defeating-men or feminism-defeating-sexism. Far from being “neat” and “fit” with our mental frames, women suffrage was a victory of feminism tainted by racism, of a gender-equality accomplishment that rejected racial equality.

Presently, we live in a racially susceptible, culturally divisive, and politically contentious time. 2020 not only marks Women’s Suffrage Centennial but also the year of a high-stakes presidential election, in the thick of an unprecedented Black-Lives-Matter movement. Gender and race are lined up to configure the current sociopolitical landscape; competing voices collide in hatred, bigotry and at times, in violence. Then the question is, are we equipped and ready for a race/gender dialog in the face of disconnect, distrust, and diatribe in 2020?

The answer is, not quite and not yet.

This article digs into historic and cultural depth for a root-cause examination of “why not yet” in 2020. As an interdisciplinary article, its narratives, analysis, arguments, and conclusions in the following sections are anchored in historical studies but for cultural studies engagement and outcome. Historicity, with facts and evidences, lays a tangible foundation for the weaving of cultural narratives and the extrapolating of cultural patterns. Footnote 1 An intimate dialog between gender and race occurs when we recognize familiar fear and bigotry from the past, and trace out similar divisive patterns in the current historical moment and the present sociopolitical landscape. Thus, as methodology, the article engages in research-based interpretations and analysis of context and text. Historicity delineates historical and sociopolitical contexts that have produced iconic figures, landmark events, and influential writings/texts. Conversely, documentations and written works left behind by those who made history provide textual evidence of the contexts that they lived, created, and shaped. In a symbiotic interplay, contexts and texts mirror one another to configure a cultural history that speaks to us today. At the conjuncture of history and culture and society, an intimate dialog between gender and race celebrates the centennial of women’s suffrage and dissects the racial injustice of the present day, as evidenced by George Floyd’s tragic death in May 2020. These events shape and configure American culture for the years to come.

Part 1—the missing link between gender and race in 2020: the binary and the color line

In the present time of political divisiveness and racial injustice, the link between gender and race is missing, let alone the dialog. In fact, it was severed a century ago by the collision between the power center and its periphery, the standard and the diverse, in American culture. Both sides were tripped over the impassable and perennial “color line”, to use W.E.B. DuBois’ term, which divides the nation in two since its inception. As a building block of American culture, the women’s suffrage movement was a gigantic sociopolitical and cultural step for women moving from the gender periphery to the patriarchal power center. However, this gigantic step is ironically not immune to forming an intersectional center/periphery binary within the women’s suffrage movement, with white women at the power center and African-American, as well as all other women of color at the periphery.

In 1848, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott organized the Seneca Falls Convention to launch the movement for women’s rights in the United States. Subsequently, women around the country protested, picketed, and were imprisoned to secure their constitutional right to vote. That was a historic moment when women took on a patriarchal power structure that had been in place against them in the United States. While all men are born equal in this great country, American women of all races have had to fight for the right to vote in order to be a full citizen and an equal human being. The patriarchal oppression takes countless forms across cultures and for millennia along human history. The basic and universal form is however the binary and gender hierarchy of male/female. It takes courage and ingenuity to write history with a female hand. American women did precisely that in 1848 and set the nation on the path to gender equality. After 72 years, on June 4, 1920, the 19th Amendment to the Constitution was passed by the Congress and granted women the right to vote for the first time in the U.S. history. Many trailblazers of the movement did not live to see the landmark fruit of their enduring struggle and prolonged fight. “Only two women who participated in the Seneca Falls convention were still alive when the Nineteenth Amendment went into effect” (Mintz, 2007 , p. 47). At the centennial, nationwide, museums, libraries, schools, and institutions celebrate the passing of the 19th Amendment with forums, exhibitions, seminars, lectures, and parties. Needless to say, this is the occasion of national gender celebration that moves American women in unison to honor the suffragists’ legacy. Everyone is expected to remember or learn what textbook teaches. There is a “standard” and “centralized” version of what happened a century ago and who were the protagonists. Individuals across political spectrums, genders, races, and age groups are brought together to admire the courageous, visionary, and resilient suffragists. The occasion is largely treated as a single-issue victory of gender equality and as a binary engagement of how feminism defeated sexism.

The long-held “mainstream” and “standard” celebration implies a one-size-fits-all assumption. WASP women are assumed to represent all women across races and heritages, embody the gender of the American female, and speak for all women in one voice of gender equality. The WASP uniformity and universality has been established by dismissing diversity and racial inequality within the realm of gender. Not all women were created equal in the U.S. history; the struggle for racial equality is encapsulated and often eclipsed in the struggle of gender equality. Keeping women of color in the periphery, in a support role or in irrelevance to white women’s suffrage, or simply discarding their existence are some of the mechanisms of the racial divide. It is not surprising that there is a canon that regards the WASP women as unquestionably perfect and flawless heroes, leaders, and saviors for all American women. This is the standard narrative rarely questioned and reevaluated in the suffrage history. However, after a century’s immigration and demographic shifting, in 2020, the terms “women” or “American women” expand to previously uncharted territories, while revolving around two reminiscent forces at play to define these terms: the one at the center that universalizes the terms in a vertical direction, and the one at the periphery that diversifies the term in a horizontal direction.

First, let us focus on the universalizing and vertical force. Upon the suffrage centennial, the term “American women” is still largely used in reference to the WASP women as in history. We have rarely pondered its cultural underpinnings. It is a widely accepted or acquiesced in cultural imagination that WASP women are the face and voice of all American women across races and heritages, of the women’s suffrage movement and of the centennial. Statues and monuments of Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, Amelia Mott and Lucy Stone grace national parks, cities and historical sites, institutionalizing the narrative that the women suffrage is “white”. Sojourner Truth was later included in one of the representations as a response to the criticism of exclusion of black suffragists. The universalizing force has much to do with the cultural “blueprint” that the WASPs set up at the birth of our nation. The “blueprint” has never been altered, in spite of the challenges of new cultural DNA pooled from the Civil War and the Civil Rights Movement in particular. The men and women, programed in the initial WASP cultural design, inherit these cultural genes from generation to generation:

The central elements of that culture [American] can be defined in a variety of ways but include the Christian religion, Protestant values and moralism, a work ethic, the English language, British traditions of law, justice, and the limits of government power, and a legacy of European art, literature, philosophy and music (Huntington, 2004 , p. 40).

From a long Anglo-Saxon dominated culture and tradition in the United States, these element have been held as essential and fundamental; they are the “American Creed”. WASP women had been victimized by WASP men for centuries; WASP women stood up in the women’s suffrage movement and became a beacon for all oppressed women around the world to look up to. Nonetheless, to what extent do the WASP women share or reject Huntington’s monocutluralist view? Not clear. What is clear is that Huntington’s view has the WASPs’ cultural DNA as the standard, the norm, and the authority to shape and define American culture. In a paradoxical way, the WASP culture DNA left its undeletable print, through the suffragists themselves, in the women’s suffrage movement. Quite a few suffragist leaders themselves were abolitionist but turned to be racially vitriolic in fighting for (white) women’s rights. This paradox has helped with the WASP exclusive ownership of women’s suffrage history, as well as women’s fight for gender equality in general. The sense of exclusivity rejects groups of non-WASP heritages and divides citizens/women into the mainstream and the marginalized. Thus, pivoted on the WASP blueprint, within women rights movement, a culture wall is erected by the WASP elites for exclusion and a power binary of the center/the periphery—WASP women/African American women—is created.

Second, let us shift our focus to the diversifying and horizontal force. After a century of continuous, massive, and non-Anglo/Nordic immigration, which unavoidably sparked social and culture transformations, the year 2020 witnesses a “browner” and “flatter” America. As of the present day, there has been a significant increase of women of color; they now represent roughly 40% of U.S. women. Footnote 2 When American women come together on the occasion of the Suffrage Centennial, the togetherness is far from being the sameness, despite shared interest for gender equality. Throughout suffrage history, women of color were never much of a presence at best and they were discriminated and prevented from exercising their voting rights at worst. Then, what is Women’s Suffrage Centennial to a woman of color? Footnote 3 In the “browner” and “flatter” America of the present day, not only do white women continue their fight for gender equality in their professional and personal lives, but also a much broadened range of marginalized entities, defined by gender, as well as race, find themselves in day-to-day struggle for inclusion, equality, citizenship, and humanity. These include women and men of color, immigrants, LGBTQ Footnote 4 citizens, individuals from a non-Christian faith, and members of special needs. An unprecedentedly diverse and all-encompassing population, just like white women a century ago, is fighting to cross the power binary of the center/the periphery separated by the color line. However, their binary is different from the one that their WASP sisters faced; it is a double binary with a double center and a double periphery—racial and gender. A double divide prevents women of color from being a full citizen, as well as a full woman as their rights are alienable on both fronts. If the celebration of the centennial highlights white women’s leadership, contribution and achievements in universal terms, defined by vertical WASP values, then, many contemporary American women of color would certainly find themselves as “unfit” with the narrative of women suffrage; they would remain left out the nation’s history.

The confrontation of the universalizing force from the center and the diversifying force from the periphery not only drives the women suffrage centennial to the crossroads of gender and race, but also reveals a deeper split between the two in our present social milieu. A woman of color in 2020 is no longer in the image of a freedom-deprived slave working in a cotton field in the antebellum South. She can well be a highly-educated individual, a lawyer, an executive, an artist, or a medical doctor. By the Constitution, as white women, a woman of color has equal and “unalienable rights” of education, citizenship, and the pursuit of happiness. She may be from a long line of ancestors who witnessed the inception of this nation or may be a first or second generation immigrant. Either falls into at least one of these categories: Native-African-Asian-Hispanic-Muslim-LGBTQ Americans. These “non-white” and non-WASP identities, after 100 years of the struggle for gender equality, nonetheless, still have not yet crossed “the color line” to be accepted as inherently American. When an African-American woman speaks up, she would invite the perception of “an angry woman”. When a Hispanic-American woman is in charge, how “American” she is to deserve that position would be an unuttered question. When an Asian-American woman acts with self-confidence, she would be labeled as a “banana”—yellow outside and white inside. The notion that being a white is American or more American than a person of color is still prevalent.

Racism and color line in 2020 are not as raw and crude as the ones that characterized the society a century ago. They are well absorbed into institutional systems and continue to dehumanize people of color in the name of law, conventions, patriotism, and American values. Deep in the fabric of the society and in the core of the culture, the center continues to exercise its dominance; the wounds of the periphery reopen and continue to bleed, internally or externally, in the presence of an external trigger. As the latest in a long line of Black victims of systemic racism, George Floyd’s death has sparked racial hemorrhage not only in the US but globally. In a more subtle and covert fashion, the institutional racism has left its undeletable stain not only on women’s suffrage movement but on its anniversary celebrations. “Standard” women’s suffrage anniversaries have always been the celebration of iconic figures like Stanton, Mott, Anthony, and Stone, among others. Indeed, the vision, leadership, spirit, and accomplishment of these remarkable WASP women have transformed our society and reshaped American culture. In many significant ways in the struggle for gender equality, American women across races, ethnicities, religions and heritages are indebted to the history that the WASP women have made. Nonetheless, all this glory does not alter a racialized past and does not heal the internal wounds sustained over a century. The togetherness of American women no longer means gender homogeneity but gender diversity. That not all women are created equal still remains a reality in 2020. Not only the nation but also American feminism is still divided by the color line. The question “what is Women’s Suffrage Centennial to a ‘browner’ and ‘flatter’ America” confronts the “center” and the “standard”, reevaluates the “periphery” and the diverse, and redefines the term of “American women”. A historical examination how racial equality interacts with gender equality becomes indispensable in recasting the centennial celebrations.

Part 2—a blocked dialog between gender and race in history