Cookies on this website

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you click 'Accept all cookies' we'll assume that you are happy to receive all cookies and you won't see this message again. If you click 'Reject all non-essential cookies' only necessary cookies providing core functionality such as security, network management, and accessibility will be enabled. Click 'Find out more' for information on how to change your cookie settings.

Critical Appraisal tools

Critical appraisal worksheets to help you appraise the reliability, importance and applicability of clinical evidence.

Critical appraisal is the systematic evaluation of clinical research papers in order to establish:

- Does this study address a clearly focused question ?

- Did the study use valid methods to address this question?

- Are the valid results of this study important?

- Are these valid, important results applicable to my patient or population?

If the answer to any of these questions is “no”, you can save yourself the trouble of reading the rest of it.

This section contains useful tools and downloads for the critical appraisal of different types of medical evidence. Example appraisal sheets are provided together with several helpful examples.

Critical Appraisal Worksheets

- Systematic Reviews Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Diagnostics Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Prognosis Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Randomised Controlled Trials (RCT) Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Critical Appraisal of Qualitative Studies Sheet

- IPD Review Sheet

Chinese - translated by Chung-Han Yang and Shih-Chieh Shao

- Systematic Reviews Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Diagnostic Study Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Prognostic Critical Appraisal Sheet

- RCT Critical Appraisal Sheet

- IPD reviews Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Qualitative Studies Critical Appraisal Sheet

German - translated by Johannes Pohl and Martin Sadilek

- Systematic Review Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Diagnosis Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Prognosis Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Therapy / RCT Critical Appraisal Sheet

Lithuanian - translated by Tumas Beinortas

- Systematic review appraisal Lithuanian (PDF)

- Diagnostic accuracy appraisal Lithuanian (PDF)

- Prognostic study appraisal Lithuanian (PDF)

- RCT appraisal sheets Lithuanian (PDF)

Portugese - translated by Enderson Miranda, Rachel Riera and Luis Eduardo Fontes

- Portuguese – Systematic Review Study Appraisal Worksheet

- Portuguese – Diagnostic Study Appraisal Worksheet

- Portuguese – Prognostic Study Appraisal Worksheet

- Portuguese – RCT Study Appraisal Worksheet

- Portuguese – Systematic Review Evaluation of Individual Participant Data Worksheet

- Portuguese – Qualitative Studies Evaluation Worksheet

Spanish - translated by Ana Cristina Castro

- Systematic Review (PDF)

- Diagnosis (PDF)

- Prognosis Spanish Translation (PDF)

- Therapy / RCT Spanish Translation (PDF)

Persian - translated by Ahmad Sofi Mahmudi

- Prognosis (PDF)

- PICO Critical Appraisal Sheet (PDF)

- PICO Critical Appraisal Sheet (MS-Word)

- Educational Prescription Critical Appraisal Sheet (PDF)

Explanations & Examples

- Pre-test probability

- SpPin and SnNout

- Likelihood Ratios

- Mayo Clinic Libraries

- Systematic Reviews

- Critical Appraisal by Study Design

Systematic Reviews: Critical Appraisal by Study Design

- Knowledge Synthesis Comparison

- Knowledge Synthesis Decision Tree

- Standards & Reporting Results

- Materials in the Mayo Clinic Libraries

- Training Resources

- Review Teams

- Develop & Refine Your Research Question

- Develop a Timeline

- Project Management

- Communication

- PRISMA-P Checklist

- Eligibility Criteria

- Register your Protocol

- Other Resources

- Other Screening Tools

- Grey Literature Searching

- Citation Searching

- Data Extraction Tools

- Minimize Bias

- Synthesis & Meta-Analysis

- Publishing your Systematic Review

Tools for Critical Appraisal of Studies

“The purpose of critical appraisal is to determine the scientific merit of a research report and its applicability to clinical decision making.” 1 Conducting a critical appraisal of a study is imperative to any well executed evidence review, but the process can be time consuming and difficult. 2 The critical appraisal process requires “a methodological approach coupled with the right tools and skills to match these methods is essential for finding meaningful results.” 3 In short, it is a method of differentiating good research from bad research.

Critical Appraisal by Study Design (featured tools)

- Non-RCTs or Observational Studies

- Diagnostic Accuracy

- Animal Studies

- Qualitative Research

- Tool Repository

- AMSTAR 2 The original AMSTAR was developed to assess the risk of bias in systematic reviews that included only randomized controlled trials. AMSTAR 2 was published in 2017 and allows researchers to “identify high quality systematic reviews, including those based on non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions.” 4 more... less... AMSTAR 2 (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews)

- ROBIS ROBIS is a tool designed specifically to assess the risk of bias in systematic reviews. “The tool is completed in three phases: (1) assess relevance(optional), (2) identify concerns with the review process, and (3) judge risk of bias in the review. Signaling questions are included to help assess specific concerns about potential biases with the review.” 5 more... less... ROBIS (Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews)

- BMJ Framework for Assessing Systematic Reviews This framework provides a checklist that is used to evaluate the quality of a systematic review.

- CASP Checklist for Systematic Reviews This CASP checklist is not a scoring system, but rather a method of appraising systematic reviews by considering: 1. Are the results of the study valid? 2. What are the results? 3. Will the results help locally? more... less... CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- CEBM Systematic Reviews Critical Appraisal Sheet The CEBM’s critical appraisal sheets are designed to help you appraise the reliability, importance, and applicability of clinical evidence. more... less... CEBM (Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine)

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools, Checklist for Systematic Reviews JBI Critical Appraisal Tools help you assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis.

- NHLBI Study Quality Assessment of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses The NHLBI’s quality assessment tools were designed to assist reviewers in focusing on concepts that are key for critical appraisal of the internal validity of a study. more... less... NHLBI (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute)

- RoB 2 RoB 2 “provides a framework for assessing the risk of bias in a single estimate of an intervention effect reported from a randomized trial,” rather than the entire trial. 6 more... less... RoB 2 (revised tool to assess Risk of Bias in randomized trials)

- CASP Randomised Controlled Trials Checklist This CASP checklist considers various aspects of an RCT that require critical appraisal: 1. Is the basic study design valid for a randomized controlled trial? 2. Was the study methodologically sound? 3. What are the results? 4. Will the results help locally? more... less... CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- CONSORT Statement The CONSORT checklist includes 25 items to determine the quality of randomized controlled trials. “Critical appraisal of the quality of clinical trials is possible only if the design, conduct, and analysis of RCTs are thoroughly and accurately described in the report.” 7 more... less... CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials)

- NHLBI Study Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies The NHLBI’s quality assessment tools were designed to assist reviewers in focusing on concepts that are key for critical appraisal of the internal validity of a study. more... less... NHLBI (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute)

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools Checklist for Randomized Controlled Trials JBI Critical Appraisal Tools help you assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis.

- ROBINS-I ROBINS-I is a “tool for evaluating risk of bias in estimates of the comparative effectiveness… of interventions from studies that did not use randomization to allocate units… to comparison groups.” 8 more... less... ROBINS-I (Risk Of Bias in Non-randomized Studies – of Interventions)

- NOS This tool is used primarily to evaluate and appraise case-control or cohort studies. more... less... NOS (Newcastle-Ottawa Scale)

- AXIS Cross-sectional studies are frequently used as an evidence base for diagnostic testing, risk factors for disease, and prevalence studies. “The AXIS tool focuses mainly on the presented [study] methods and results.” 9 more... less... AXIS (Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies)

- NHLBI Study Quality Assessment Tools for Non-Randomized Studies The NHLBI’s quality assessment tools were designed to assist reviewers in focusing on concepts that are key for critical appraisal of the internal validity of a study. • Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies • Quality Assessment of Case-Control Studies • Quality Assessment Tool for Before-After (Pre-Post) Studies With No Control Group • Quality Assessment Tool for Case Series Studies more... less... NHLBI (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute)

- Case Series Studies Quality Appraisal Checklist Developed by the Institute of Health Economics (Canada), the checklist is comprised of 20 questions to assess “the robustness of the evidence of uncontrolled, [case series] studies.” 10

- Methodological Quality and Synthesis of Case Series and Case Reports In this paper, Dr. Murad and colleagues “present a framework for appraisal, synthesis and application of evidence derived from case reports and case series.” 11

- MINORS The MINORS instrument contains 12 items and was developed for evaluating the quality of observational or non-randomized studies. 12 This tool may be of particular interest to researchers who would like to critically appraise surgical studies. more... less... MINORS (Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies)

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools for Non-Randomized Trials JBI Critical Appraisal Tools help you assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis. • Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies • Checklist for Case Control Studies • Checklist for Case Reports • Checklist for Case Series • Checklist for Cohort Studies

- QUADAS-2 The QUADAS-2 tool “is designed to assess the quality of primary diagnostic accuracy studies… [it] consists of 4 key domains that discuss patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow of patients through the study and timing of the index tests and reference standard.” 13 more... less... QUADAS-2 (a revised tool for the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies)

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools Checklist for Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies JBI Critical Appraisal Tools help you assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis.

- STARD 2015 The authors of the standards note that “[e]ssential elements of [diagnostic accuracy] study methods are often poorly described and sometimes completely omitted, making both critical appraisal and replication difficult, if not impossible.”10 The Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies was developed “to help… improve completeness and transparency in reporting of diagnostic accuracy studies.” 14 more... less... STARD 2015 (Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies)

- CASP Diagnostic Study Checklist This CASP checklist considers various aspects of diagnostic test studies including: 1. Are the results of the study valid? 2. What were the results? 3. Will the results help locally? more... less... CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- CEBM Diagnostic Critical Appraisal Sheet The CEBM’s critical appraisal sheets are designed to help you appraise the reliability, importance, and applicability of clinical evidence. more... less... CEBM (Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine)

- SYRCLE’s RoB “[I]mplementation of [SYRCLE’s RoB tool] will facilitate and improve critical appraisal of evidence from animal studies. This may… enhance the efficiency of translating animal research into clinical practice and increase awareness of the necessity of improving the methodological quality of animal studies.” 15 more... less... SYRCLE’s RoB (SYstematic Review Center for Laboratory animal Experimentation’s Risk of Bias)

- ARRIVE 2.0 “The [ARRIVE 2.0] guidelines are a checklist of information to include in a manuscript to ensure that publications [on in vivo animal studies] contain enough information to add to the knowledge base.” 16 more... less... ARRIVE 2.0 (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments)

- Critical Appraisal of Studies Using Laboratory Animal Models This article provides “an approach to critically appraising papers based on the results of laboratory animal experiments,” and discusses various “bias domains” in the literature that critical appraisal can identify. 17

- CEBM Critical Appraisal of Qualitative Studies Sheet The CEBM’s critical appraisal sheets are designed to help you appraise the reliability, importance and applicability of clinical evidence. more... less... CEBM (Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine)

- CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist This CASP checklist considers various aspects of qualitative research studies including: 1. Are the results of the study valid? 2. What were the results? 3. Will the results help locally? more... less... CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias Tool Repository Created by librarians at Duke University, this extensive listing contains over 100 commonly used risk of bias tools that may be sorted by study type.

- Latitudes Network A library of risk of bias tools for use in evidence syntheses that provides selection help and training videos.

References & Recommended Reading

1. Kolaski, K., Logan, L. R., & Ioannidis, J. P. (2024). Guidance to best tools and practices for systematic reviews . British Journal of Pharmacology , 181 (1), 180-210

2. Portney LG. Foundations of clinical research : applications to evidence-based practice. Fourth edition. ed. Philadelphia: F A Davis; 2020.

3. Fowkes FG, Fulton PM. Critical appraisal of published research: introductory guidelines. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 1991;302(6785):1136-1140.

4. Singh S. Critical appraisal skills programme. Journal of Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapeutics. 2013;4(1):76-77.

5. Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2017;358:j4008.

6. Whiting P, Savovic J, Higgins JPT, et al. ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2016;69:225-234.

7. Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2019;366:l4898.

8. Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2010;63(8):e1-37.

9. Sterne JA, Hernan MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2016;355:i4919.

10. Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ open. 2016;6(12):e011458.

11. Guo B, Moga C, Harstall C, Schopflocher D. A principal component analysis is conducted for a case series quality appraisal checklist. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2016;69:199-207.e192.

12. Murad MH, Sultan S, Haffar S, Bazerbachi F. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ evidence-based medicine. 2018;23(2):60-63.

13. Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ journal of surgery. 2003;73(9):712-716.

14. Whiting PF, Rutjes AWS, Westwood ME, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Annals of internal medicine. 2011;155(8):529-536.

15. Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2015;351:h5527.

16. Hooijmans CR, Rovers MM, de Vries RBM, Leenaars M, Ritskes-Hoitinga M, Langendam MW. SYRCLE's risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC medical research methodology. 2014;14:43.

17. Percie du Sert N, Ahluwalia A, Alam S, et al. Reporting animal research: Explanation and elaboration for the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0. PLoS biology. 2020;18(7):e3000411.

18. O'Connor AM, Sargeant JM. Critical appraisal of studies using laboratory animal models. ILAR journal. 2014;55(3):405-417.

- << Previous: Minimize Bias

- Next: GRADE >>

- Last Updated: May 31, 2024 1:57 PM

- URL: https://libraryguides.mayo.edu/systematicreviewprocess

Critical Appraisal of Quantitative Research

- Living reference work entry

- Latest version View entry history

- First Online: 12 June 2018

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Rocco Cavaleri 2 ,

- Sameer Bhole 3 , 5 &

- Amit Arora 2 , 4 , 5

1281 Accesses

1 Citations

2 Altmetric

Critical appraisal skills are important for anyone wishing to make informed decisions or improve the quality of healthcare delivery. A good critical appraisal provides information regarding the believability and usefulness of a particular study. However, the appraisal process is often overlooked, and critically appraising quantitative research can be daunting for both researchers and clinicians. This chapter introduces the concept of critical appraisal and highlights its importance in evidence-based practice. Readers are then introduced to the most common quantitative study designs and key questions to ask when appraising each type of study. These studies include systematic reviews, experimental studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized controlled trials), and observational studies (cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies). This chapter also provides the tools most commonly used to appraise the methodological and reporting quality of quantitative studies. Overall, this chapter serves as a step-by-step guide to appraising quantitative research in healthcare settings.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Altman DG, Bland JM. Treatment allocation in controlled trials: why randomise? BMJ. 1999;318(7192):1209.

Article Google Scholar

Arora A, Scott JA, Bhole S, Do L, Schwarz E, Blinkhorn AS. Early childhood feeding practices and dental caries in preschool children: a multi-centre birth cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):28.

Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Irwig LM, … Lijmer JG. The STARD statement for reporting studies of diagnostic accuracy: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(1):W1–12.

Google Scholar

Cavaleri R, Schabrun S, Te M, Chipchase L. Hand therapy versus corticosteroid injections in the treatment of de quervain’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hand Ther. 2016;29(1):3–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jht.2015.10.004 .

Centre for Evidence-based Management. Critical appraisal tools. 2017. Retrieved 20 Dec 2017, from https://www.cebma.org/resources-and-tools/what-is-critical-appraisal/ .

Centre for Evidence-based Medicine. Critical appraisal worksheets. 2017. Retrieved 3 Dec 2017, from http://www.cebm.net/blog/2014/06/10/critical-appraisal/ .

Clark HD, Wells GA, Huët C, McAlister FA, Salmi LR, Fergusson D, Laupacis A. Assessing the quality of randomized trials: reliability of the jadad scale. Control Clin Trials. 1999;20(5):448–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-2456(99)00026-4 .

Critical Appraisal Skills Program. Casp checklists. 2017. Retrieved 5 Dec 2017, from http://www.casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists .

Dawes M, Davies P, Gray A, Mant J, Seers K, Snowball R. Evidence-based practice: a primer for health care professionals. London: Elsevier; 2005.

Dumville JC, Torgerson DJ, Hewitt CE. Research methods: reporting attrition in randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2006;332(7547):969.

Greenhalgh T, Donald A. Evidence-based health care workbook: understanding research for individual and group learning. London: BMJ Publishing Group; 2000.

Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Cook DJ, Guyatt G, Bass E, Brill-Edwards P, … Gerstein H. Users’ guides to the medical literature: II. How to use an article about therapy or prevention. JAMA. 1993;270(21):2598–601.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, … Jaeschke R. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction – GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4), 383–94.

Herbert R, Jamtvedt G, Mead J, Birger Hagen K. Practical evidence-based physiotherapy. London: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2005.

Hewitt CE, Torgerson DJ. Is restricted randomisation necessary? BMJ. 2006;332(7556):1506–8.

Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.0.2. The cochrane collaboration. 2009. Retrieved 3 Dec 2017, from http://www.cochrane-handbook.org .

Hoffmann T, Bennett S, Del Mar C. Evidence-based practice across the health professions. Chatswood: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2013.

Hoffmann T, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, … Johnston M. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ, 2014;348: g1687.

Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical appraisal tools. 2017. Retrieved 4 Dec 2017, from http://joannabriggs.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.html .

Mhaskar R, Emmanuel P, Mishra S, Patel S, Naik E, Kumar A. Critical appraisal skills are essential to informed decision-making. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. 2009;30(2):112–9. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7184.62770 .

Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel group randomized trials. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2001;1(1):2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-1-2 .

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the prisma statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

National Health and Medical Research Council. NHMRC additional levels of evidence and grades for recommendations for developers of guidelines. Canberra: NHMRC; 2009. Retrieved from https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/file/guidelines/developers/nhmrc_levels_grades_evidence_120423.pdf .

National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Study quality assessment tools. 2017. Retrieved 17 Dec 2017, from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools .

Physiotherapy Evidence Database. PEDro scale. 2017. Retrieved 10 Dec 2017, from https://www.pedro.org.au/english/downloads/pedro-scale/ .

Portney L, Watkins M. Foundations of clinical research: application to practice. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River: F.A. Davis Company/Publishers; 2009.

Roberts C, Torgerson DJ. Understanding controlled trials: baseline imbalance in randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 1999;319(7203):185.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, … Kristjansson E. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4008 .

Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, … Boutron I. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, … Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–12.

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, Initiative S. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (strobe) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1495–9.

Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, … Bossuyt PM. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med 2011;155(8):529–36.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Science and Health, Western Sydney University, Campbelltown, NSW, Australia

Rocco Cavaleri & Amit Arora

Sydney Dental School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Surry Hills, NSW, Australia

Sameer Bhole

Discipline of Child and Adolescent Health, Sydney Medical School, The University of Sydney, Westmead, NSW, Australia

Oral Health Services, Sydney Local Health District and Sydney Dental Hospital, NSW Health, Surry Hills, NSW, Australia

Sameer Bhole & Amit Arora

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rocco Cavaleri .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Science & Health, Western Sydney University, Penrith, New South Wales, Australia

Pranee Liamputtong

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Cavaleri, R., Bhole, S., Arora, A. (2018). Critical Appraisal of Quantitative Research. In: Liamputtong, P. (eds) Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences . Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2779-6_120-2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2779-6_120-2

Received : 20 January 2018

Accepted : 12 February 2018

Published : 12 June 2018

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-10-2779-6

Online ISBN : 978-981-10-2779-6

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Social Sciences Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

Chapter history

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2779-6_120-2

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2779-6_120-1

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Critical Appraisal Tools

- Introduction

- Related Guides

- Getting Help

Critical Appraisal of Studies

Critical appraisal is the process of carefully and systematically examining research to judge its trustworthiness, and its value/relevance in a particular context by providing a framework to evaluate the research. During the critical appraisal process, researchers can:

- Decide whether studies have been undertaken in a way that makes their findings reliable as well as valid and unbiased

- Make sense of the results

- Know what these results mean in the context of the decision they are making

- Determine if the results are relevant to their patients/schoolwork/research

Burls, A. (2009). What is critical appraisal? In What Is This Series: Evidence-based medicine. Available online at What is Critical Appraisal?

Critical appraisal is included in the process of writing high quality reviews, like systematic and integrative reviews and for evaluating evidence from RCTs and other study designs. For more information on systematic reviews, check out our Systematic Review guide.

- Next: Critical Appraisal Tools >>

- Last Updated: Nov 16, 2023 1:27 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.duq.edu/critappraise

CASP Checklists

How to use our CASP Checklists

Referencing and Creative Commons

- Online Training Courses

- CASP Workshops

- What is Critical Appraisal

- Study Designs

- Useful Links

- Bibliography

- View all Tools and Resources

- Testimonials

Critical Appraisal Checklists

We offer a number of free downloadable checklists to help you more easily and accurately perform critical appraisal across a number of different study types.

The CASP checklists are easy to understand but in case you need any further guidance on how they are structured, take a look at our guide on how to use our CASP checklists .

CASP Checklist: Systematic Reviews with Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies

CASP Checklist: Systematic Reviews with Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs)

CASP Randomised Controlled Trial Checklist

- Print & Fill

CASP Systematic Review Checklist

CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist

CASP Cohort Study Checklist

CASP Diagnostic Study Checklist

CASP Case Control Study Checklist

CASP Economic Evaluation Checklist

CASP Clinical Prediction Rule Checklist

Checklist Archive

- CASP Randomised Controlled Trial Checklist 2018 fillable form

- CASP Randomised Controlled Trial Checklist 2018

CASP Checklist

Need more information?

- Online Learning

- Privacy Policy

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) will use the information you provide on this form to be in touch with you and to provide updates and marketing. Please let us know all the ways you would like to hear from us:

We use Mailchimp as our marketing platform. By clicking below to subscribe, you acknowledge that your information will be transferred to Mailchimp for processing. Learn more about Mailchimp's privacy practices here.

Copyright 2024 CASP UK - OAP Ltd. All rights reserved Website by Beyond Your Brand

Critical Appraisal Tools and Reporting Guidelines for Evidence-Based Practice

Affiliations.

- 1 Professor, School of Nursing & Health Professions, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA.

- 2 Reference Librarian and Primary Liaison, School of Nursing & Health Professions, Gleeson Library, Geschke Center, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, CA 94117, USA.

- PMID: 28898556

- DOI: 10.1111/wvn.12258

Background: Nurses engaged in evidence-based practice (EBP) have two important sets of tools: Critical appraisal tools and reporting guidelines. Critical appraisal tools facilitate the appraisal process and guide a consumer of evidence through an objective, analytical, evaluation process. Reporting guidelines, checklists of items that should be included in a publication or report, ensure that the project or guidelines are reported on with clarity, completeness, and transparency.

Purpose: The primary purpose of this paper is to help nurses understand the difference between critical appraisal tools and reporting guidelines. A secondary purpose is to help nurses locate the appropriate tool for the appraisal or reporting of evidence.

Methods: A systematic search was conducted to find commonly used critical appraisal tools and reporting guidelines for EBP in nursing.

Rationale: This article serves as a resource to help nurse navigate the often-overwhelming terrain of critical appraisal tools and reporting guidelines, and will help both novice and experienced consumers of evidence more easily select the appropriate tool(s) to use for critical appraisal and reporting of evidence. Having the skills to select the appropriate tool or guideline is an essential part of meeting EBP competencies for both practicing registered nurses and advanced practice nurses (Melnyk & Gallagher-Ford, 2015; Melnyk, Gallagher-Ford, & Fineout-Overholt, 2017).

Results: Nine commonly used critical appraisal tools and eight reporting guidelines were found and are described in this manuscript. Specific steps for selecting an appropriate tool as well as examples of each tool's use in a publication are provided.

Linking evidence to action: Practicing registered nurses and advance practice nurses must be able to critically appraise and disseminate evidence in order to meet EBP competencies. This article is a resource for understanding the difference between critical appraisal tools and reporting guidelines, and identifying and accessing appropriate tools or guidelines.

Keywords: critical appraisal tools; evidence-based nursing; evidence-based practice; reporting guidelines.

© 2017 Sigma Theta Tau International.

Publication types

- Data Collection / methods

- Evidence-Based Practice / methods

- Evidence-Based Practice / standards*

- Nurses / trends*

- Practice Guidelines as Topic / standards*

- Quality of Health Care / standards

- Risk Management / methods

- Risk Management / standards*

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 27, Issue Suppl 2

- 12 Critical appraisal tools for qualitative research – towards ‘fit for purpose’

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Veronika Williams 1 ,

- Anne-Marie Boylan 2 ,

- Newhouse Nikki 2 ,

- David Nunan 2

- 1 Nipissing University, North Bay, Canada

- 2 University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Qualitative research has an important place within evidence-based health care (EBHC), contributing to policy on patient safety and quality of care, supporting understanding of the impact of chronic illness, and explaining contextual factors surrounding the implementation of interventions. However, the question of whether, when and how to critically appraise qualitative research persists. Whilst there is consensus that we cannot - and should not – simplistically adopt existing approaches for appraising quantitative methods, it is nonetheless crucial that we develop a better understanding of how to subject qualitative evidence to robust and systematic scrutiny in order to assess its trustworthiness and credibility. Currently, most appraisal methods and tools for qualitative health research use one of two approaches: checklists or frameworks. We have previously outlined the specific issues with these approaches (Williams et al 2019). A fundamental challenge still to be addressed, however, is the lack of differentiation between different methodological approaches when appraising qualitative health research. We do this routinely when appraising quantitative research: we have specific checklists and tools to appraise randomised controlled trials, diagnostic studies, observational studies and so on. Current checklists for qualitative research typically treat the entire paradigm as a single design (illustrated by titles of tools such as ‘CASP Qualitative Checklist’, ‘JBI checklist for qualitative research’) and frameworks tend to require substantial understanding of a given methodological approach without providing guidance on how they should be applied. Given the fundamental differences in the aims and outcomes of different methodologies, such as ethnography, grounded theory, and phenomenological approaches, as well as specific aspects of the research process, such as sampling, data collection and analysis, we cannot treat qualitative research as a single approach. Rather, we must strive to recognise core commonalities relating to rigour, but considering key methodological differences. We have argued for a reconsideration of current approaches to the systematic appraisal of qualitative health research (Williams et al 2021), and propose the development of a tool or tools that allow differentiated evaluations of multiple methodological approaches rather than continuing to treat qualitative health research as a single, unified method. Here we propose a workshop for researchers interested in the appraisal of qualitative health research and invite them to develop an initial consensus regarding core aspects of a new appraisal tool that differentiates between the different qualitative research methodologies and thus provides a ‘fit for purpose’ tool, for both, educators and clinicians.

https://doi.org/10.1136/ebm-2022-EBMLive.36

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 16 September 2004

A systematic review of the content of critical appraisal tools

- Persis Katrak 1 ,

- Andrea E Bialocerkowski 2 ,

- Nicola Massy-Westropp 1 ,

- VS Saravana Kumar 1 &

- Karen A Grimmer 1

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 4 , Article number: 22 ( 2004 ) Cite this article

157k Accesses

208 Citations

14 Altmetric

Metrics details

Consumers of research (researchers, administrators, educators and clinicians) frequently use standard critical appraisal tools to evaluate the quality of published research reports. However, there is no consensus regarding the most appropriate critical appraisal tool for allied health research. We summarized the content, intent, construction and psychometric properties of published, currently available critical appraisal tools to identify common elements and their relevance to allied health research.

A systematic review was undertaken of 121 published critical appraisal tools sourced from 108 papers located on electronic databases and the Internet. The tools were classified according to the study design for which they were intended. Their items were then classified into one of 12 criteria based on their intent. Commonly occurring items were identified. The empirical basis for construction of the tool, the method by which overall quality of the study was established, the psychometric properties of the critical appraisal tools and whether guidelines were provided for their use were also recorded.

Eighty-seven percent of critical appraisal tools were specific to a research design, with most tools having been developed for experimental studies. There was considerable variability in items contained in the critical appraisal tools. Twelve percent of available tools were developed using specified empirical research. Forty-nine percent of the critical appraisal tools summarized the quality appraisal into a numeric summary score. Few critical appraisal tools had documented evidence of validity of their items, or reliability of use. Guidelines regarding administration of the tools were provided in 43% of cases.

Conclusions

There was considerable variability in intent, components, construction and psychometric properties of published critical appraisal tools for research reports. There is no "gold standard' critical appraisal tool for any study design, nor is there any widely accepted generic tool that can be applied equally well across study types. No tool was specific to allied health research requirements. Thus interpretation of critical appraisal of research reports currently needs to be considered in light of the properties and intent of the critical appraisal tool chosen for the task.

Peer Review reports

Consumers of research (clinicians, researchers, educators, administrators) frequently use standard critical appraisal tools to evaluate the quality and utility of published research reports [ 1 ]. Critical appraisal tools provide analytical evaluations of the quality of the study, in particular the methods applied to minimise biases in a research project [ 2 ]. As these factors potentially influence study results, and the way that the study findings are interpreted, this information is vital for consumers of research to ascertain whether the results of the study can be believed, and transferred appropriately into other environments, such as policy, further research studies, education or clinical practice. Hence, choosing an appropriate critical appraisal tool is an important component of evidence-based practice.

Although the importance of critical appraisal tools has been acknowledged [ 1 , 3 – 5 ] there appears to be no consensus regarding the 'gold standard' tool for any medical evidence. In addition, it seems that consumers of research are faced with a large number of critical appraisal tools from which to choose. This is evidenced by the recent report by the Agency for Health Research Quality in which 93 critical appraisal tools for quantitative studies were identified [ 6 ]. Such choice may pose problems for research consumers, as dissimilar findings may well be the result when different critical appraisal tools are used to evaluate the same research report [ 6 ].

Critical appraisal tools can be broadly classified into those that are research design-specific and those that are generic. Design-specific tools contain items that address methodological issues that are unique to the research design [ 5 , 7 ]. This precludes comparison however of the quality of different study designs [ 8 ]. To attempt to overcome this limitation, generic critical appraisal tools have been developed, in an attempt to enhance the ability of research consumers to synthesise evidence from a range of quantitative and or qualitative study designs (for instance [ 9 ]). There is no evidence that generic critical appraisal tools and design-specific tools provide a comparative evaluation of research designs.

Moreover, there appears to be little consensus regarding the most appropriate items that should be contained within any critical appraisal tool. This paper is concerned primarily with critical appraisal tools that address the unique properties of allied health care and research [ 10 ]. This approach was taken because of the unique nature of allied health contacts with patients, and because evidence-based practice is an emerging area in allied health [ 10 ]. The availability of so many critical appraisal tools (for instance [ 6 ]) may well prove daunting for allied health practitioners who are learning to critically appraise research in their area of interest. For the purposes of this evaluation, allied health is defined as encompassing "...all occasions of service to non admitted patients where services are provided at units/clinics providing treatment/counseling to patients. These include units primarily concerned with physiotherapy, speech therapy, family panning, dietary advice, optometry occupational therapy..." [ 11 ].

The unique nature of allied health practice needs to be considered in allied health research. Allied health research thus differs from most medical research, with respect to:

• the paradigm underpinning comprehensive and clinically-reasoned descriptions of diagnosis (including validity and reliability). An example of this is in research into low back pain, where instead of diagnosis being made on location and chronicity of pain (as is common) [ 12 ], it would be made on the spinal structure and the nature of the dysfunction underpinning the symptoms, which is arrived at by a staged and replicable clinical reasoning process [ 10 , 13 ].

• the frequent use of multiple interventions within the one contact with the patient (an occasion of service), each of which requires appropriate description in terms of relationship to the diagnosis, nature, intensity, frequency, type of instruction provided to the patient, and the order in which the interventions were applied [ 13 ]

• the timeframe and frequency of contact with the patient (as many allied health disciplines treat patients in episodes of care that contain multiple occasions of service, and which can span many weeks, or even years in the case of chronic problems [ 14 ])

• measures of outcome, including appropriate methods and timeframes of measuring change in impairment, function, disability and handicap that address the needs of different stakeholders (patients, therapists, funders etc) [ 10 , 12 , 13 ].

Search strategy

In supplementary data [see additional file 1 ].

Data organization and extraction

Two independent researchers (PK, NMW) participated in all aspects of this review, and they compared and discussed their findings with respect to inclusion of critical appraisal tools, their intent, components, data extraction and item classification, construction and psychometric properties. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third member of the team (KG).

Data extraction consisted of a four-staged process. First, identical replica critical appraisal tools were identified and removed prior to analysis. The remaining critical appraisal tools were then classified according to the study design for which they were intended to be used [ 1 , 2 ]. The scientific manner in which the tools had been constructed was classified as whether an empirical research approach has been used, and if so, which type of research had been undertaken. Finally, the items contained in each critical appraisal tool were extracted and classified into one of eleven groups, which were based on the criteria described by Clarke and Oxman [ 4 ] as:

• Study aims and justification

• Methodology used , which encompassed method of identification of relevant studies and adherence to study protocol;

• Sample selection , which ranged from inclusion and exclusion criteria, to homogeneity of groups;

• Method of randomization and allocation blinding;

• Attrition : response and drop out rates;

• Blinding of the clinician, assessor, patient and statistician as well as the method of blinding;

• Outcome measure characteristics;

• Intervention or exposure details;

• Method of data analyses ;

• Potential sources of bias ; and

• Issues of external validity , which ranged from application of evidence to other settings to the relationship between benefits, cost and harm.

An additional group, " miscellaneous ", was used to describe items that could not be classified into any of the groups listed above.

Data synthesis

Data was synthesized using MS Excel spread sheets as well as narrative format by describing the number of critical appraisal tools per study design and the type of items they contained. Descriptions were made of the method by which the overall quality of the study was determined, evidence regarding the psychometric properties of the tools (validity and reliability) and whether guidelines were provided for use of the critical appraisal tool.

One hundred and ninety-three research reports that potentially provided a description of a critical appraisal tool (or process) were identified from the search strategy. Fifty-six of these papers were unavailable for review due to outdated Internet links, or inability to source the relevant journal through Australian university and Government library databases. Of the 127 papers retrieved, 19 were excluded from this review, as they did not provide a description of the critical appraisal tool used, or were published in languages other than English. As a result, 108 papers were reviewed, which yielded 121 different critical appraisal tools [ 1 – 5 , 7 , 9 , 15 – 102 , 116 ].

Empirical basis for tool construction

We identified 14 instruments (12% all tools) which were reported as having been constructed using a specified empirical approach [ 20 , 29 , 30 , 32 , 35 , 40 , 49 , 51 , 70 – 72 , 79 , 103 , 116 ]. The empirical research reflected descriptive and/or qualitative approaches, these being critical review of existing tools [ 40 , 72 ], Delphi techniques to identify then refine data items [ 32 , 51 , 71 ], questionnaires and other forms of written surveys to identify and refine data items [ 70 , 79 , 103 ], facilitated structured consensus meetings [ 20 , 29 , 30 , 35 , 40 , 49 , 70 , 72 , 79 , 116 ], and pilot validation testing [ 20 , 40 , 72 , 103 , 116 ]. In all the studies which reported developing critical appraisal tools using a consensus approach, a range of stakeholder input was sought, reflecting researchers and clinicians in a range of health disciplines, students, educators and consumers. There were a further 31 papers which cited other studies as the source of the tool used in the review, but which provided no information on why individual items had been chosen, or whether (or how) they had been modified. Moreover, for 21 of these tools, the cited sources of the critical appraisal tool did not report the empirical basis on which the tool had been constructed.

Critical appraisal tools per study design

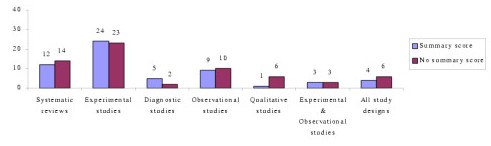

Seventy-eight percent (N = 94) of the critical appraisal tools were developed for use on primary research [ 1 – 5 , 7 , 9 , 18 , 19 , 25 – 27 , 34 , 37 – 41 ], while the remainder (N = 26) were for secondary research (systematic reviews and meta-analyses) [ 2 – 5 , 15 – 36 , 116 ]. Eighty-seven percent (N = 104) of all critical appraisal tools were design-specific [ 2 – 5 , 7 , 9 , 15 – 90 ], with over one third (N = 45) developed for experimental studies (randomized controlled trials, clinical trials) [ 2 – 4 , 25 – 27 , 34 , 37 – 73 ]. Sixteen critical appraisal tools were generic. Of these, six were developed for use on both experimental and observational studies [ 9 , 91 – 95 ], whereas 11 were purported to be useful for any qualitative and quantitative research design [ 1 , 18 , 41 , 96 – 102 , 116 ] (see Figure 1 , Table 1 ).

Number of critical appraisal tools per study design [1,2]

Critical appraisal items

One thousand, four hundred and seventy five items were extracted from these critical appraisal tools. After grouping like items together, 173 different item types were identified, with the most frequently reported items being focused towards assessing the external validity of the study (N = 35) and method of data analyses (N = 28) (Table 2 ). The most frequently reported items across all critical appraisal tools were:

Eligibility criteria (inclusion/exclusion criteria) (N = 63)

Appropriate statistical analyses (N = 47)

Random allocation of subjects (N = 43)

Consideration of outcome measures used (N = 43)

Sample size justification/power calculations (N = 39)

Study design reported (N = 36)

Assessor blinding (N = 36)

Design-specific critical appraisal tools

Systematic reviews.

Eighty-seven different items were extracted from the 26 critical appraisal tools, which were designed to evaluate the quality of systematic reviews. These critical appraisal tools frequently contained items regarding data analyses and issues of external validity (Tables 2 and 3 ).

Items assessing data analyses were focused to the methods used to summarize the results, assessment of sensitivity of results and whether heterogeneity was considered, whereas the nature of reporting of the main results, interpretation of them and their generalizability were frequently used to assess the external validity of the study findings. Moreover, systematic review critical appraisal tools tended to contain items such as identification of relevant studies, search strategy used, number of studies included and protocol adherence, that would not be relevant for other study designs. Blinding and randomisation procedures were rarely included in these critical appraisal tools.

Experimental studies

One hundred and twenty thirteen different items were extracted from the 45 experimental critical appraisal tools. These items most frequently assessed aspects of data analyses and blinding (Tables 1 and 2 ). Data analyses items were focused on whether appropriate statistical analysis was performed, whether a sample size justification or power calculation was provided and whether side effects of the intervention were recorded and analysed. Blinding was focused on whether the participant, clinician and assessor were blinded to the intervention.

Diagnostic studies

Forty-seven different items were extracted from the seven diagnostic critical appraisal tools. These items frequently addressed issues involving data analyses, external validity of results and sample selection that were specific to diagnostic studies (whether the diagnostic criteria were defined, definition of the "gold" standard, the calculation of sensitivity and specificity) (Tables 1 and 2 ).

Observational studies

Seventy-four different items were extracted from the 19 critical appraisal tools for observational studies. These items primarily focused on aspects of data analyses (see Tables 1 and 2 , such as whether confounders were considered in the analysis, whether a sample size justification or power calculation was provided and whether appropriate statistical analyses were preformed.

Qualitative studies

Thirty-six different items were extracted from the seven qualitative study critical appraisal tools. The majority of these items assessed issues regarding external validity, methods of data analyses and the aims and justification of the study (Tables 1 and 2 ). Specifically, items were focused to whether the study question was clearly stated, whether data analyses were clearly described and appropriate, and application of the study findings to the clinical setting. Qualitative critical appraisal tools did not contain items regarding sample selection, randomization, blinding, intervention or bias, perhaps because these issues are not relevant to the qualitative paradigm.

Generic critical appraisal tools

Experimental and observational studies.

Forty-two different items were extracted from the six critical appraisal tools that could be used to evaluate experimental and observational studies. These tools most frequently contained items that addressed aspects of sample selection (such as inclusion/exclusion criteria of participants, homogeneity of participants at baseline) and data analyses (such as whether appropriate statistical analyses were performed, whether a justification of the sample size or power calculation were provided).

All study designs

Seventy-eight different items were contained in the ten critical appraisal tools that could be used for all study designs (quantitative and qualitative). The majority of these items focused on whether appropriate data analyses were undertaken (such as whether confounders were considered in the analysis, whether a sample size justification or power calculation was provided and whether appropriate statistical analyses were preformed) and external validity issues (generalization of results to the population, value of the research findings) (see Tables 1 and 2 ).

Allied health critical appraisal tools

We found no critical appraisal instrument specific to allied health research, despite finding at least seven critical appraisal instruments associated with allied health topics (mostly physiotherapy management of orthopedic conditions) [ 37 , 39 , 52 , 58 , 59 , 65 ]. One critical appraisal development group proposed two instruments [ 9 ], specific to quantitative and qualitative research respectively. The core elements of allied health research quality (specific diagnosis criteria, intervention descriptions, nature of patient contact and appropriate outcome measures) were not addressed in any one tool sourced for this evaluation. We identified 152 different ways of considering quality reporting of outcome measures in the 121 critical appraisal tools, and 81 ways of considering description of interventions. Very few tools which were not specifically targeted to diagnostic studies (less than 10% of the remaining tools) addressed diagnostic criteria. The critical appraisal instrument that seemed most related to allied health research quality [ 39 ] sought comprehensive evaluation of elements of intervention and outcome, however this instrument was relevant only to physiotherapeutic orthopedic experimental research.

Overall study quality

Forty-nine percent (N = 58) of critical appraisal tools summarised the results of the quality appraisal into a single numeric summary score [ 5 , 7 , 15 – 25 , 37 – 59 , 74 – 77 , 80 – 83 , 87 , 91 – 93 , 96 , 97 ] (Figure 2 ). This was achieved by one of two methods:

Number of critical appraisal tools with, and without, summary quality scores

An equal weighting system, where one point was allocated to each item fulfilled; or

A weighted system, where fulfilled items were allocated various points depending on their perceived importance.

However, there was no justification provided for any of the scoring systems used. In the remaining critical appraisal tools (N = 62), a single numerical summary score was not provided [ 1 – 4 , 9 , 25 – 36 , 60 – 73 , 78 , 79 , 84 – 90 , 94 , 95 , 98 – 102 ]. This left the research consumer to summarize the results of the appraisal in a narrative manner, without the assistance of a standard approach.

Psychometric properties of critical appraisal tools

Few critical appraisal tools had documented evidence of their validity and reliability. Face validity was established in nine critical appraisal tools, seven of which were developed for use on experimental studies [ 38 , 40 , 45 , 49 , 51 , 63 , 70 ] and two for systematic reviews [ 32 , 103 ]. Intra-rater reliability was established for only one critical appraisal tool as part of its empirical development process [ 40 ], whereas inter-rater reliability was reported for two systematic review tools [ 20 , 36 ] (for one of these as part of the developmental process [ 20 ]) and seven experimental critical appraisal tools [ 38 , 40 , 45 , 51 , 55 , 56 , 63 ] (for two of these as part of the developmental process [ 40 , 51 ]).

Critical appraisal tool guidelines

Forty-three percent (N = 52) of critical appraisal tools had guidelines that informed the user of the interpretation of each item contained within them (Table 2 ). These guidelines were most frequently in the form of a handbook or published paper (N = 31) [ 2 , 4 , 9 , 15 , 20 , 25 , 28 , 29 , 31 , 36 , 37 , 41 , 50 , 64 – 67 , 69 , 80 , 84 – 87 , 89 , 90 , 95 , 100 , 116 ], whereas in 14 critical appraisal tools explanations accompanied each item [ 16 , 26 , 27 , 40 , 49 , 51 , 57 , 59 , 79 , 83 , 91 , 102 ].

Our search strategy identified a large number of published critical appraisal tools that are currently available to critically appraise research reports. There was a distinct lack of information on tool development processes in most cases. Many of the tools were reported to be modifications of other published tools, or reflected specialty concerns in specific clinical or research areas, without attempts to justify inclusion criteria. Less than 10 of these tools were relevant to evaluation of the quality of allied health research, and none of these were based on an empirical research approach. We are concerned that although our search was systematic and extensive [ 104 , 105 ], our broad key words and our lack of ready access to 29% of potentially useful papers (N = 56) potentially constrained us from identifying all published critical appraisal tools. However, consumers of research seeking critical appraisal instruments are not likely to seek instruments from outdated Internet links and unobtainable journals, thus we believe that we identified the most readily available instruments. Thus, despite the limitations on sourcing all possible tools, we believe that this paper presents a useful synthesis of the readily available critical appraisal tools.

The majority of the critical appraisal tools were developed for a specific research design (87%), with most designed for use on experimental studies (38% of all critical appraisal tools sourced). This finding is not surprising as, according to the medical model, experimental studies sit at or near the top of the hierarchy of evidence [ 2 , 8 ]. In recent years, allied health researchers have strived to apply the medical model of research to their own discipline by conducting experimental research, often by using the randomized controlled trial design [ 106 ]. This trend may be the reason for the development of experimental critical appraisal tools reported in allied health-specific research topics [ 37 , 39 , 52 , 58 , 59 , 65 ].

We also found a considerable number of critical appraisal tools for systematic reviews (N = 26), which reflects the trend to synthesize research evidence to make it relevant for clinicians [ 105 , 107 ]. Systematic review critical appraisal tools contained unique items (such as identification of relevant studies, search strategy used, number of studies included, protocol adherence) compared with tools used for primary studies, a reflection of the secondary nature of data synthesis and analysis.

In contrast, we identified very few qualitative study critical appraisal tools, despite the presence of many journal-specific guidelines that outline important methodological aspects required in a manuscript submitted for publication [ 108 – 110 ]. This finding may reflect the more traditional, quantitative focus of allied health research [ 111 ]. Alternatively, qualitative researchers may view the robustness of their research findings in different terms compared with quantitative researchers [ 112 , 113 ]. Hence the use of critical appraisal tools may be less appropriate for the qualitative paradigm. This requires further consideration.

Of the small number of generic critical appraisal tools, we found few that could be usefully applied (to any health research, and specifically to the allied health literature), because of the generalist nature of their items, variable interpretation (and applicability) of items across research designs, and/or lack of summary scores. Whilst these types of tools potentially facilitate the synthesis of evidence across allied health research designs for clinicians, their lack of specificity in asking the 'hard' questions about research quality related to research design also potentially precludes their adoption for allied health evidence-based practice. At present, the gold standard study design when synthesizing evidence is the randomized controlled trial [ 4 ], which underpins our finding that experimental critical appraisal tools predominated in the allied health literature [ 37 , 39 , 52 , 58 , 59 , 65 ]. However, as more systematic literature reviews are undertaken on allied health topics, it may become more accepted that evidence in the form of other research design types requires acknowledgement, evaluation and synthesis. This may result in the development of more appropriate and clinically useful allied health critical appraisal tools.

A major finding of our study was the volume and variation in available critical appraisal tools. We found no gold standard critical appraisal tool for any type of study design. Therefore, consumers of research are faced with frustrating decisions when attempting to select the most appropriate tool for their needs. Variable quality evaluations may be produced when different critical appraisal tools are used on the same literature [ 6 ]. Thus, interpretation of critical analysis must be carefully considered in light of the critical appraisal tool used.

The variability in the content of critical appraisal tools could be accounted for by the lack of any empirical basis of tool construction, established validity of item construction, and the lack of a gold standard against which to compare new critical tools. As such, consumers of research cannot be certain that the content of published critical appraisal tools reflect the most important aspects of the quality of studies that they assess [ 114 ]. Moreover, there was little evidence of intra- or inter-rater reliability of the critical appraisal tools. Coupled with the lack of protocols for use, this may mean that critical appraisers could interpret instrument items in different ways over repeated occasions of use. This may produce variable results [123].

Based on the findings of this evaluation, we recommend that consumers of research should carefully select critical appraisal tools for their needs. The selected tools should have published evidence of the empirical basis for their construction, validity of items and reliability of interpretation, as well as guidelines for use, so that the tools can be applied and interpreted in a standardized manner. Our findings highlight the need for consensus to be reached regarding the important and core items for critical appraisal tools that will produce a more standardized environment for critical appraisal of research evidence. As a consequence, allied health research will specifically benefit from having critical appraisal tools that reflect best practice research approaches which embed specific research requirements of allied health disciplines.

National Health and Medical Research Council: How to Review the Evidence: Systematic Identification and Review of the Scientific Literature. Canberra. 2000

Google Scholar

National Health and Medical Research Council: How to Use the Evidence: Assessment and Application of Scientific Evidence. Canberra. 2000

Joanna Briggs Institute. [ http://www.joannabriggs.edu.au ]

Clarke M, Oxman AD: Cochrane Reviewer's Handbook 4.2.0. 2003, Oxford: The Cochrane Collaboration

Crombie IK: The Pocket Guide to Critical Appraisal: A Handbook for Health Care Professionals. 1996, London: BMJ Publishing Group

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Systems to Rate the Strength of Scientific Evidence. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 47, Publication No. 02-E016. Rockville. 2002

Elwood JM: Critical Appraisal of Epidemiological Studies and Clinical Trials. 1998, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2

Sackett DL, Richardson WS, Rosenberg W, Haynes RB: Evidence Based Medicine. How to Practice and Teach EBM. 2000, London: Churchill Livingstone

Critical literature reviews. [ http://www.cotfcanada.org/cotf_critical.htm ]

Bialocerkowski AE, Grimmer KA, Milanese SF, Kumar S: Application of current research evidence to clinical physiotherapy practice. J Allied Health Res Dec.

The National Health Data Dictionary – Version 10. http://www.aihw.gov.au/publications/hwi/nhdd12/nhdd12-v1.pdf and http://www.aihw.gov.au/publications/hwi/nhdd12/nhdd12-v2.pdf

Grimmer K, Bowman P, Roper J: Episodes of allied health outpatient care: an investigation of service delivery in acute public hospital settings. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2000, 22 (1/2): 80-87.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Grimmer K, Milanese S, Bialocerkowski A: Clinical guidelines for low back pain: A physiotherapy perspective. Physiotherapy Canada. 2003, 55 (4): 1-9.

Grimmer KA, Milanese S, Bialocerkowski AE, Kumar S: Producing and implementing evidence in clinical practice: the therapies' dilemma. Physiotherapy. 2004,

Greenhalgh T: How to read a paper: papers that summarize other papers (systematic reviews and meta-analysis). BMJ. 1997, 315: 672-675.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Auperin A, Pignon J, Poynard T: Review article: critical review of meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials in hepatogastroenterology. Alimentary Pharmacol Therapeutics. 1997, 11: 215-225. 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.131302000.x.

CAS Google Scholar

Barnes DE, Bero LA: Why review articles on the health effects of passive smoking reach different conclusions. J Am Med Assoc. 1998, 279: 1566-1570. 10.1001/jama.279.19.1566.

Beck CT: Use of meta-analysis as a teaching strategy in nursing research courses. J Nurs Educat. 1997, 36: 87-90.

Carruthers SG, Larochelle P, Haynes RB, Petrasovits A, Schiffrin EL: Report of the Canadian Hypertension Society Consensus Conference: 1. Introduction. Can Med Assoc J. 1993, 149: 289-293.

Oxman AD, Guyatt GH, Singer J, Goldsmith CH, Hutchinson BG, Milner RA, Streiner DL: Agreement among reviewers of review articles. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991, 44: 91-98. 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90205-N.

Sacks HS, Reitman D, Pagano D, Kupelnick B: Meta-analysis: an update. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine. 1996, 63: 216-224.

Smith AF: An analysis of review articles published in four anaesthesia journals. Can J Anaesth. 1997, 44: 405-409.

L'Abbe KA, Detsky AS, O'Rourke K: Meta-analysis in clinical research. Ann Intern Med. 1987, 107: 224-233.

PubMed Google Scholar

Mulrow CD, Antonio S: The medical review article: state of the science. Ann Intern Med. 1987, 106: 485-488.

Continuing Professional Development: A Manual for SIGN Guideline Developers. [ http://www.sign.ac.uk ]

Learning and Development Public Health Resources Unit. [ http://www.phru.nhs.uk/ ]

FOCUS Critical Appraisal Tool. [ http://www.focusproject.org.uk ]

Cook DJ, Sackett DL, Spitzer WO: Methodologic guidelines for systematic reviews of randomized control trials in health care from the Potsdam Consultation on meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995, 48: 167-171. 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00172-M.

Cranney A, Tugwell P, Shea B, Wells G: Implications of OMERACT outcomes in arthritis and osteoporosis for Cochrane metaanalysis. J Rheumatol. 1997, 24: 1206-1207.

Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Sinclair JC, Hoyward R, Cook DJ, Cook RJ: User's guide to the medical literature. IX. A method for grading health care recommendations. J Am Med Assoc. 1995, 274: 1800-1804. 10.1001/jama.274.22.1800.

Gyorkos TW, Tannenbaum TN, Abrahamowicz M, Oxman AD, Scott EAF, Milson ME, Rasooli Iris, Frank JW, Riben PD, Mathias RG: An approach to the development of practice guidelines for community health interventions. Can J Public Health. 1994, 85: S8-13.

Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, Stroup DF: Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Quality of reporting of meta-analyses. Lancet. 1999, 354: 1896-1900. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04149-5.

Oxman AD, Cook DJ, Guyatt GH: Users' guides to the medical literature. VI. How to use an overview. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. J Am Med Assoc. 1994, 272: 1367-1371. 10.1001/jama.272.17.1367.

Pogue J, Yusuf S: Overcoming the limitations of current meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 1998, 351: 47-52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)08461-4.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB: Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. J Am Med Assoc. 2000, 283: 2008-2012. 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008.

Irwig L, Tosteson AN, Gatsonis C, Lau J, Colditz G, Chalmers TC, Mostellar F: Guidelines for meta-analyses evaluating diagnostic tests. Ann Intern Med. 1994, 120: 667-676.

Moseley AM, Herbert RD, Sherrington C, Maher CG: Evidence for physiotherapy practice: A survey of the Physiotherapy Evidence Database. Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro). Australian Journal of Physiotherapy. 2002, 48: 43-50.

Cho MK, Bero LA: Instruments for assessing the quality of drug studies published in the medical literature. J Am Med Assoc. 1994, 272: 101-104. 10.1001/jama.272.2.101.

De Vet HCW, De Bie RA, Van der Heijden GJ, Verhagen AP, Sijpkes P, Kipschild PG: Systematic reviews on the basis of methodological criteria. Physiotherapy. 1997, 83: 284-289.

Downs SH, Black N: The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998, 52: 377-384.

Evans M, Pollock AV: A score system for evaluating random control clinical trials of prophylaxis of abdominal surgical wound infection. Br J Surg. 1985, 72: 256-260.

Fahey T, Hyde C, Milne R, Thorogood M: The type and quality of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in UK public health journals. J Public Health Med. 1995, 17: 469-474.

Gotzsche PC: Methodology and overt and hidden bias in reports of 196 double-blind trials of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Control Clin Trials. 1989, 10: 31-56. 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90017-2.

Imperiale TF, McCullough AJ: Do corticosteroids reduce mortality from alcoholic hepatitis? A meta-analysis of the randomized trials. Ann Int Med. 1990, 113: 299-307.

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ: Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary?. Control Clin Trials. 1996, 17: 1-12. 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4.

Khan KS, Daya S, Collins JA, Walter SD: Empirical evidence of bias in infertility research: overestimation of treatment effect in crossover trials using pregnancy as the outcome measure. Fertil Steril. 1996, 65: 939-945.

Kleijnen J, Knipschild P, ter Riet G: Clinical trials of homoeopathy. BMJ. 1991, 302: 316-323.

Liberati A, Himel HN, Chalmers TC: A quality assessment of randomized control trials of primary treatment of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1986, 4: 942-951.

Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG, for the CONSORT Group: The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. J Am Med Assoc. 2001, 285: 1987-1991. 10.1001/jama.285.15.1987.

Reisch JS, Tyson JE, Mize SG: Aid to the evaluation of therapeutic studies. Pediatrics. 1989, 84: 815-827.

Sindhu F, Carpenter L, Seers K: Development of a tool to rate the quality assessment of randomized controlled trials using a Delphi technique. J Advanced Nurs. 1997, 25: 1262-1268. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.19970251262.x.

Van der Heijden GJ, Van der Windt DA, Kleijnen J, Koes BW, Bouter LM: Steroid injections for shoulder disorders: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Br J Gen Pract. 1996, 46: 309-316.

Van Tulder MW, Koes BW, Bouter LM: Conservative treatment of acute and chronic nonspecific low back pain. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of the most common interventions. Spine. 1997, 22: 2128-2156. 10.1097/00007632-199709150-00012.

Garbutt JC, West SL, Carey TS, Lohr KN, Crews FT: Pharmacotherapy for Alcohol Dependence. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 3, AHCPR Publication No. 99-E004. Rockville. 1999

Oremus M, Wolfson C, Perrault A, Demers L, Momoli F, Moride Y: Interarter reliability of the modified Jadad quality scale for systematic reviews of Alzheimer's disease drug trials. Dement Geriatr Cognit Disord. 2001, 12: 232-236. 10.1159/000051263.

Clark O, Castro AA, Filho JV, Djubelgovic B: Interrater agreement of Jadad's scale. Annual Cochrane Colloqium Abstracts. 2001, [ http://www.biomedcentral.com/abstracts/COCHRANE/1/op031 ]October Lyon

Jonas W, Anderson RL, Crawford CC, Lyons JS: A systematic review of the quality of homeopathic clinical trials. BMC Alternative Medicine. 2001, 1: 12-10.1186/1472-6882-1-12.

Van Tulder M, Malmivaara A, Esmail R, Koes B: Exercises therapy for low back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane Collaboration back review group. Spine. 2000, 25: 2784-2796. 10.1097/00007632-200011010-00011.

Van Tulder MW, Ostelo R, Vlaeyen JWS, Linton SJ, Morley SJ, Assendelft WJJ: Behavioral treatment for chronic low back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the cochrane back. Spine. 2000, 25: 2688-2699. 10.1097/00007632-200010150-00024.

Aronson N, Seidenfeld J, Samson DJ, Aronson N, Albertson PC, Bayoumi AM, Bennett C, Brown A, Garber ABA, Gere M, Hasselblad V, Wilt T, Ziegler MPHK, Pharm D: Relative Effectiveness and Cost Effectiveness of Methods of Androgen Suppression in the Treatment of Advanced Prostate Cancer. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 4, AHCPR Publication No.99-E0012. Rockville. 1999

Chalmers TC, Smith H, Blackburn B, Silverman B, Schroeder B, Reitman D, Ambroz A: A method for assessing the quality of a randomized control trial. Control Clin Trials. 1981, 2: 31-49. 10.1016/0197-2456(81)90056-8.

der Simonian R, Charette LJ, McPeek B, Mosteller F: Reporting on methods in clinical trials. New Eng J Med. 1982, 306: 1332-1337.

Detsky AS, Naylor CD, O'Rourke K, McGeer AJ, L'Abbe KA: Incorporating variations in the quality of individual randomized trials into meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992, 45: 255-265. 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90085-2.

Goudas L, Carr DB, Bloch R, Balk E, Ioannidis JPA, Terrin MN: Management of Cancer Pain. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 35 (Contract 290-97-0019 to the New England Medical Center), AHCPR Publication No. 99-E004. Rockville. 2000

Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Cook DJ: Users' guides to the medical literature. II. How to use an article about therapy or prevention. A. Are the results of the study valid? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. J Am Med Assoc. 1993, 270: 2598-2601. 10.1001/jama.270.21.2598.

Khan KS, Ter Riet G, Glanville J, Sowden AJ, Kleijnen J: Undertaking Systematic Reviews of Research on Effectiveness: Centre of Reviews and Dissemination's Guidance for Carrying Out or Commissioning Reviews: York. 2000

McNamara R, Bass EB, Marlene R, Miller J: Management of New Onset Atrial Fibrillation. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No.12, AHRQ Publication No. 01-E026. Rockville. 2001