Human Research Violations By UCSD Eye Doctor Showcase A National Problem

Tens of millions of people have volunteered their time and bodies to help create breakthroughs in medicine. You see the results with the pain relievers in your medicine cabinet, the vaccines that protect you from disease, the pacemakers that keep your heart beating and the innovations happening now with stem cells.

Yet the systems meant to protect those volunteers from harm are far from perfect, and research violations by Dr. Kang Zhang , an eye doctor at the University of California San Diego, show just how easily that well-intentioned framework can collapse.

Zhang is the chief of eye genetics at UCSD and has a lab named after him at the university. He receives millions of dollars in federal grants and presents at symposiums around the world.

A few years ago, he helped develop a way to remove cataracts from infants and regenerate their lenses using their own stem cells. He also built a tool that scanned over a million patient records and diagnosed illnesses with more than 90% accuracy.

But several of Zhang’s studies were riddled with violations of basic human research standards. A U.S. Food and Drug Administration warning in 2017 and a UCSD audit that followed reveal a pattern that put patients in harm’s way for years.

The 56-year-old doctor enrolled people he shouldn’t have for his medical trials, failed to document what happened to 25 units of a study drug, performed HIV tests on participants without their permission, kept poor records on his patients and didn’t complete necessary ethics training for a stem cell study.

When asked by the FDA to create a plan to prevent more violations from happening in the future, Zhang didn’t provide one.

“There ought to be some serious penalties for this sort of thing,” said Spencer Hey, a Harvard Medical School expert in biomedical research ethics.

inewsource reached out to Zhang, the director of the eye institute where he works and the director of UCSD’s human research protection program for interviews. In response, UCSD sent a statement that said the university had “implemented a comprehensive management plan to address these issues” and suspended Zhang indefinitely from serving as a primary researcher overseeing human research studies at UCSD. He may continue to apply for federal grants, publish in medical journals and train the next generation of scientists.

UCSD later told inewsource , “Zhang’s research had undergone multiple audits since 2012,” which prompted his suspension. When asked if that meant the university had known about Zhang’s violations for five years before taking action, a UCSD spokeswoman would not comment further.

After speaking with five ethics experts for this story, it appears Zhang’s violations — and what happened after they were discovered — are symptomatic of larger problems impacting the field of human subject research in the U.S. Those include patchwork oversight and poor communication between watchdog agencies, a lack of transparency and dialogue with the public, and a combination of money and prestige that sometimes safeguard an institution’s reputation more than patient welfare.

“Science is accelerating always,” said Stacey Springs , Harvard University’s research integrity officer. “But it feels that it’s accelerating in ways that are pushing on regulatory compliance like never before. So we really need to focus now, and learn from each other, and apply these best practices – because it's coming fast.”

An early warning

Zhang received his medical degree and doctorate in genetics from Harvard, then taught at Johns Hopkins University and the University of Utah before founding UCSD’s Institute for Genomic Medicine in 2009.

His accomplishments have landed him on CBS’ “60 Minutes” and in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and the Los Angeles Times. He’s received dozens of honors from national and international associations and universities, published or co-authored more than 100 peer-reviewed manuscripts in top journals and recruited human research subjects from around the world – including from the San Diego VA and UCSD’s Shiley Eye Institute on the La Jolla campus.

It was during Zhang’s time at the institute, in the summer of 2016, when the FDA inspected one of his ongoing human trials to ensure the “rights, safety, and welfare” of his patients were protected.

For five years, Zhang had been testing a drug to reverse the effects of a common age-related eye disease. He received approval to enroll patients whose vision had already started to decline – to see if the drug could restore their sight.

Zhang’s research team injected ranibizumab once a month into each test subject’s eyes, 12 times total for each patient. The drug can produce side effects that include eye haemorrhages, pain, inflammation and spots in a field of vision. In rare cases, it can prompt serious cataracts or blindness.

The FDA letter prompted UCSD to suspend enrollment in all of Zhang’s active research projects at the time, pending the results of an internal audit.

Amy Caruso Brown is an assistant professor of bioethics, humanities and pediatrics at New York’s Upstate Medical University. She also is a member of an institutional review board – a safety committee that approves and oversees projects like Zhang’s.

Brown spoke to inewsource after reading the UCSD audit and said, “I have not seen this number of issues in the five years that I've been on an IRB.”Twelve people had participated in the study by the time the FDA stepped in and found five of them were ineligible because they didn’t have the vision problems Zhang outlined for participants. Another patient’s eyesight wasn’t correctly evaluated before the person was injected with the drug.

“If it had been one out of a hundred, we could probably chalk that up to an error that doesn’t reflect a pattern of misconduct,” said Michael Carome , a former associate director at the U.S. Office for Human Research Protections, one of many federal agencies that protects human research subjects.

“But to enroll half the subjects not meeting enrollment criteria – that is more than just an occasional error. That suggests something systematically wrong with how they’re doing the research,” said Carome, who spent years investigating these kind of violations while at the agency.

He left the Office for Human Research Protections in 2010 during a decade of decline, when the office all but stopped using its enforcement tools in favor of “a more friendly approach toward institutions,” he said.

Carome is now a director of the health research group at Public Citizen , a consumer advocacy nonprofit based in Washington, D.C.

He told inewsource that research on otherwise healthy patients needs to be performed carefully, because they aren’t sick enough to justify taking chances.

“Both from a scientific standpoint and ethical human subjects standpoint, not complying with the enrollment criteria is a big deal,” Carome said, calling the guidelines “crucial in terms of ensuring that human subjects are protected.”

The FDA agreed. It issued Zhang a warning letter in January 2017 that called out his use of ineligible patients and his failure to perform required screenings and procedures, poor recordkeeping and lack of documentation about what happened to 25 units of the unused study drug (which Zhang said were destroyed).

Though not mentioned in the letter, the UCSD audit that followed said Zhang also enrolled patients while the study was suspended.

The FDA uses warning letters to document serious research problems and mandate corrective actions. Three times in the letter, it told Zhang his actions raised “concerns about the validity and integrity of the data collected,” and three times it told Zhang he didn’t have an adequate plan to keep his patients safe moving forward.

“We are unable to undertake an informed evaluation of your written response because you did not provide a corrective action plan that, if properly carried out, would prevent this type of violation in the future,” the FDA wrote.

The study was eventually shut down, and inewsource could find no articles published based on the research.

‘Major league science’

Zhang’s work at UCSD should be viewed in context.

He is one of more than 1,600 faculty members in the schools of medicine and pharmacy, one part of a healthcare system at a university ranked among the top research institutions in the country.

UCSD secured $1.2 billion in sponsored research support in 2018 – with $686 million going toward UC Health Sciences – and had more than 7,000 patients participating in clinical trials. Its scientists have made breakthroughs in diabetes research, understanding cancer genes, identifying early signs of autism and treating Alzheimer’s disease. It counts 16 Nobel laureates among current and former faculty.

All of that makes UCSD’s investigation of Zhang unique. The university has published 249 internal audits since July 2010, and the Zhang report is the only one inewsource could find specific to an individual researcher.

Auditors reviewed Zhang’s training records, enrollment logs, regulatory binders and files for ongoing projects that had enrolled human research patients. They found problems everywhere they looked: Zhang failed to get the proper consent from all patients; didn’t report problems to UCSD’s institutional review board; lost documents; kept inaccurate records; wrongly billed patients; and didn’t complete the training required to work with human embryonic stem cells.

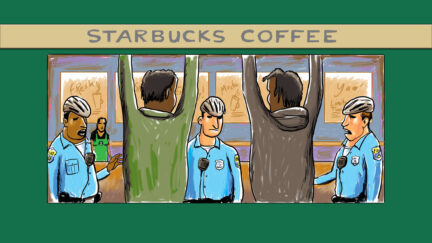

In one study, Zhang’s staff tested patients’ blood for HIV and AIDS without telling them, against federal policy.

“He’s lucky there weren’t any major patient harms,” Brown said. ”But if you act like this all the time, eventually you will hurt someone.”

The auditors found Zhang’s actions may have “negatively impacted the rights, welfare, and safety of human subjects in clinical research.” One of his studies, sponsored by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine , collected tissue from donors with blinding eye disease for a stem cell bank. California voters created the institute in 2004 to fund this type of research.

The study’s rules stated no one under 50 years old was allowed to enroll. UCSD audited files for 50 of the more than 400 patients and found seven were too young, including a minor.

Carome, the former federal director, laughed when he read that section.

“That’s not a subtle mistake,” he said.

Another finding noted the importance of “credible and valid data” when describing a study that was missing 25 of 50 patient progress reports.

“This isn’t minor league stuff. This is major league science,” said Hey, the Harvard bioethicist, who added, “this sort of pattern should raise questions about the validity of (Zhang’s) published work.”

Zhang did publish a correction in January, but not for a study included in the audit. It involved gene editing in animals, and Zhang’s paper said UCSD supervised and approved the research. That wasn’t true – it was overseen by a university and medical center in China.

inewsource couldn’t find any published articles based on the six studies reviewed by the FDA and UCSD. Yet during the audits and study suspensions, Zhang is listed as having continued a genetics research project at the San Diego VA, which did result in 10 published articles.

UCSD doctors often work as attending physi cians at the San Diego VA and share funding, research samples, data and lab space. The VA Hospital is less than a mile from the Shiley Eye Institute and on the same campus. Yet the VA said it was never notified of the UCSD or FDA reports until inewsource asked about them in March.

A VA spokeswoman would not answer questions about whether Zhang was still practicing at the VA, enrolling patients in trials or proposing new research at the institution. The San Diego VA has one of the largest research programs in the national VA network.

Nor were other related federal or state regulators notified. That includes the federal Office for Human Research Protections, which protects research subjects from harm; the National Institutes of Health , which funds many of Zhang’s studies; the Office of Research Integrity, which oversees research misconduct cases; or the California State Medical Board, which gave Zhang a license to practice medicine.

“Communication is fraught with complexity in compliance matters,” said Springs, Harvard’s research integrity officer. Things sometimes happen on a need-to-know basis, she said, and confidentiality plays a big part.

But, she said, “If there are active studies and participants are in danger, the confidentiality is out the window.”

Symptoms of a larger problem

Picture the framework for protecting research subjects as a house.

The foundation consists of a study, planned with sound scientific and ethical principles, and a responsible, ethical researcher. If and when things go wrong or change, they are communicated and addressed immediately. That didn’t happen in this case.

Institutional review boards, the first floor, are often composed of expert volunteers who spend countless hours poring over hundreds of pages of research protocols, guidelines and regulations while also working their regular jobs. They rely on researchers to keep them updated, alert them to problems and speak the truth, but they may also have the power and responsibility to audit ongoing studies. It’s often a proactive system, but it wasn’t in Zhang’s case.

And the institutional review board system is “vulnerable to unethical manipulation, particularly by companies or individuals who intend to abuse the system or to commit fraud,” according to an undercover federal investigation from 2009.

Higher-ups at an institution – the second floor – may have reasons and methods to keep violations quiet and away from public scrutiny. The Zhang audit is a perfect example: It was published more than two years ago but didn’t reach the VA across campus, never made the news, and likely wouldn’t have shocked anyone who stumbled upon it because it never named Zhang as the researcher under scrutiny. The only place his name appears is on the report’s cover page – as one of 16 people copied on its transmittal within the UC system, including UCSD’s chief ethics and compliance officer, vice chancellors, various directors and others.

“It doesn’t look good for the university to be calling out these high-profile faculty for these kinds of violations and making a big deal out of it and applying sanctions, because that’s not the kind of attention you want to draw to your researchers,” Harvard’s Hey said.

Problems with internal probes

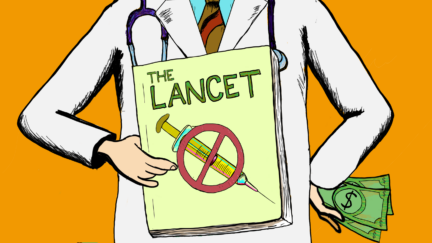

An opinion article published by three ethics experts last year in The Journal of the American Medical Association said when internal investigations are completed, the reports are often not standardized, not peer-reviewed, have limited oversight and contain conflicts of interest. “Even when institutions act, the information they release to the public is often limited and unhelpful,” they wrote.

Calling out lucrative researchers can also result in lost funding. Last fiscal year, federal agencies including the National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation and U.S. Department of Defense gave UCSD $681 million in research funding. UCSD prides itself on how much grant money flows its way each year and has defended that stream aggressively: It sued the University of Southern California in 2015 for poaching one of its most lucrative researchers.

And as quickly as those funding agencies give, they can take away – or even require repayment if serious violations happened using taxpayer dollars.

At the very top of the house, the roof is made up of agencies that regulate human subject protection across the country. The big one – the Office for Human Research Protections – protects those involved in research funded or conducted by the U.S. Health and Human Services Department. It can investigate allegations of wrongdoing but often does not, choosing instead to refer investigations back to the institutions themselves. It can also revoke an entire institution’s ability to perform human research, though that hasn’t happened since 2007.

At Harvard, Springs said she often uses these agencies as a lever in talks with researchers to get them to understand and follow rules. She said the patchwork of institutional, academic and statewide regulations can be messy, so there’s a hope that the feds will act consistently, “because they really are the heavy in these conversations.”

But, she added, “Then they aren't predictable, and you're like, ‘Wow, OK. So they have these enforcement mechanisms and they're not using them. Or they're using them selectively.’”

The Office for Human Research Protections never took action in the Zhang case, which isn’t surprising for two reasons. One, they weren’t informed by the FDA or UCSD of his violations. Two, the agency has drastically cut down on enforcement over the past decade.

For example, it charged institutions with investigating misconduct allegations 94 times in 2002. In 2015, it did that three times. For the same period, the agency went from issuing 146 “determination letters” – an important tool for communicating findings of misconduct – to issuing five.

It’s not due to a lack of funding or a drop in complaints. In fact, institutional misconduct reports sent to the office jumped 400 percent from 2002 to 2014.

Carome said his former agency’s current leadership is “less interested in issuing harsh findings and embarrassing institutions.”

The problem with that, he said, is enforcement actions are “one of the more important tools the office has to change behavior.”

The Office of Research Integrity , another federal agency that oversees research misconduct investigations, has also been criticized for slowing its enforcement. It recently went nearly 10 months without issuing a single finding of research misconduct, though the agency has since stepped up its actions.

One medical ethicist quoted in an industry publication in 2017 called the lack of oversight by the Office of Research Integrity and the Office for Human Research Protections “nothing short of appalling.”

Even if oversight agencies were operating at full speed, a lack of transparency and data sharing would still be major flaws in safeguarding patients that could rip the roof apart.

Compliance data at the Office for Human Research Protections is kept in-house and offline, and getting at it requires a public records request, weeks to months of wait time and then skilled data analysis. The California Medical Board publishes doctor information online , but it’s more concerned with things like medical malpractice judgments, physician substance abuse and negligence in the course of routine health care than monitoring human research and clinical trials. Its database isn’t designed to incorporate audit findings, FDA warning letters or federal databases.

Academic investigations – at least in California – are kept far from Google’s reach, and typically require a public records request and the knowledge they exist. The same goes for institutional review board investigations, reviews and audits.

And none of these systems communicate with each other in any meaningful way.

Carome added one more problem plaguing the field: “Much noncompliance goes undetected or unnoticed.”

Zhang’s audit likely would have gone unnoticed if inewsource weren’t digging into the risks associated with human research, yet Springs said this may prove an opportunity for UCSD.

“When these cases emerge in the press, or people come to hear about them in some way, it highlights our failures – and that should happen,” she said.

But even then, Springs said, it doesn’t always “turn into constructive discussion and dialogue around how we can fix it.”

Audits like Zhang’s are often unintelligible to the community, to patients enrolled and even to academics, even though they are the people who should be providing feedback and criticism, she said.

“These are opportunities where we can actually promote transparency,” she said, “and say, ‘Hey, this is what happened. This is how we approached it,’ and model effective dialogue with communities on how we can work better on this.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story cited a 2017 industry publication that said the Office of Research Integrity had gone a year without making a research misconduct finding. Since the story published, the office has clarified that it went nine months and 21 days without a finding of research misconduct between 2016 and 2017.

Case Summaries

2008 and older.

Email Updates

Annual Review of Ethics Case Studies

What are research ethics cases.

For additional information, please visit Resources for Research Ethics Education

Research Ethics Cases are a tool for discussing scientific integrity. Cases are designed to confront the readers with a specific problem that does not lend itself to easy answers. By providing a focus for discussion, cases help staff involved in research to define or refine their own standards, to appreciate alternative approaches to identifying and resolving ethical problems, and to develop skills for dealing with hard problems on their own.

Research Ethics Cases for Use by the NIH Community

- Theme 23 – Authorship, Collaborations, and Mentoring (2023)

- Theme 22 – Use of Human Biospecimens and Informed Consent (2022)

- Theme 21 – Science Under Pressure (2021)

- Theme 20 – Data, Project and Lab Management, and Communication (2020)

- Theme 19 – Civility, Harassment and Inappropriate Conduct (2019)

- Theme 18 – Implicit and Explicit Biases in the Research Setting (2018)

- Theme 17 – Socially Responsible Science (2017)

- Theme 16 – Research Reproducibility (2016)

- Theme 15 – Authorship and Collaborative Science (2015)

- Theme 14 – Differentiating Between Honest Discourse and Research Misconduct and Introduction to Enhancing Reproducibility (2014)

- Theme 13 – Data Management, Whistleblowers, and Nepotism (2013)

- Theme 12 – Mentoring (2012)

- Theme 11 – Authorship (2011)

- Theme 10 – Science and Social Responsibility, continued (2010)

- Theme 9 – Science and Social Responsibility - Dual Use Research (2009)

- Theme 8 – Borrowing - Is It Plagiarism? (2008)

- Theme 7 – Data Management and Scientific Misconduct (2007)

- Theme 6 – Ethical Ambiguities (2006)

- Theme 5 – Data Management (2005)

- Theme 4 – Collaborative Science (2004)

- Theme 3 – Mentoring (2003)

- Theme 2 – Authorship (2002)

- Theme 1 – Scientific Misconduct (2001)

For Facilitators Leading Case Discussion

For the sake of time and clarity of purpose, it is essential that one individual have responsibility for leading the group discussion. As a minimum, this responsibility should include:

- Reading the case aloud.

- Defining, and re-defining as needed, the questions to be answered.

- Encouraging discussion that is “on topic”.

- Discouraging discussion that is “off topic”.

- Keeping the pace of discussion appropriate to the time available.

- Eliciting contributions from all members of the discussion group.

- Summarizing both majority and minority opinions at the end of the discussion.

How Should Cases be Analyzed?

Many of the skills necessary to analyze case studies can become tools for responding to real world problems. Cases, like the real world, contain uncertainties and ambiguities. Readers are encouraged to identify key issues, make assumptions as needed, and articulate options for resolution. In addition to the specific questions accompanying each case, readers should consider the following questions:

- Who are the affected parties (individuals, institutions, a field, society) in this situation?

- What interest(s) (material, financial, ethical, other) does each party have in the situation? Which interests are in conflict?

- Were the actions taken by each of the affected parties acceptable (ethical, legal, moral, or common sense)? If not, are there circumstances under which those actions would have been acceptable? Who should impose what sanction(s)?

- What other courses of action are open to each of the affected parties? What is the likely outcome of each course of action?

- For each party involved, what course of action would you take, and why?

- What actions could have been taken to avoid the conflict?

Is There a Right Answer?

Acceptable solutions.

Most problems will have several acceptable solutions or answers, but it will not always be the case that a perfect solution can be found. At times, even the best solution will still have some unsatisfactory consequences.

Unacceptable Solutions

While more than one acceptable solution may be possible, not all solutions are acceptable. For example, obvious violations of specific rules and regulations or of generally accepted standards of conduct would typically be unacceptable. However, it is also plausible that blind adherence to accepted rules or standards would sometimes be an unacceptable course of action.

Ethical Decision-Making

It should be noted that ethical decision-making is a process rather than a specific correct answer. In this sense, unethical behavior is defined by a failure to engage in the process of ethical decision-making. It is always unacceptable to have made no reasonable attempt to define a consistent and defensible basis for conduct.

This page was last updated on Friday, July 7, 2023

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 05 June 2019

Japanese hospital uncovers flood of research ethics violations

- Mark Zastrow

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

A brain and heart hospital and research centre in Japan has found 158 cases of studies being done in violation of ethics standards since 2013.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-01747-w

Reprints and permissions

Related Articles

University says prominent Japanese cell biologist committed misconduct

Japan fails to settle university dispute

Research integrity guidelines in Japan

Seed-stashing chickadees overturn ideas about location memory

News & Views 23 MAY 24

Neural pathways for reward and relief promote fentanyl addiction

News & Views 22 MAY 24

AI networks reveal how flies find a mate

Guidelines for academics aim to lessen ethical pitfalls in generative-AI use

Nature Index 22 MAY 24

Are robots the solution to the crisis in older-person care?

Outlook 25 APR 24

Lethal AI weapons are here: how can we control them?

News Feature 23 APR 24

Postdoctoral Research Associate- Oncology

Memphis, Tennessee

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (St. Jude)

Group Leader in Immunology

The Institut Necker Enfants Malades (https://www.institut-necker-enfants-malades.fr/) in Paris seeks a group leader in Immunology.

Paris, Ile-de-France (FR)

INSERM DR IdF PARIS CENTRE

Postdoc Erdmann Group, Structural Biology Research Center

Job description APPLICATION CLOSING DATE: 12/06/2024 Human Technopole (HT) is an interdisciplinary life science research institute, created and sup...

Human Technopole

The recruitment for Earth Science High-talent in IDSSE, CAS

Seeking global talents in the field of Earth Science and Ocean Engineering.

Sanya, Hainan, China

Institute of Deep-sea Science and Engineering, Chinese Academy of Sciences

Faculty(Group Leaders or Principal Investigators) and Postdoc positions

Faculty and Postdoc positions are open all year.

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

The Stomatology Hospital, School of Stomatology, Zhejiang University School of Medicine(ZJUSS)

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 30 April 2021

A scoping review of the literature featuring research ethics and research integrity cases

- Anna Catharina Vieira Armond ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7121-5354 1 ,

- Bert Gordijn 2 ,

- Jonathan Lewis 2 ,

- Mohammad Hosseini 2 ,

- János Kristóf Bodnár 1 ,

- Soren Holm 3 , 4 &

- Péter Kakuk 5

BMC Medical Ethics volume 22 , Article number: 50 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

26 Citations

28 Altmetric

Metrics details

The areas of Research Ethics (RE) and Research Integrity (RI) are rapidly evolving. Cases of research misconduct, other transgressions related to RE and RI, and forms of ethically questionable behaviors have been frequently published. The objective of this scoping review was to collect RE and RI cases, analyze their main characteristics, and discuss how these cases are represented in the scientific literature.

The search included cases involving a violation of, or misbehavior, poor judgment, or detrimental research practice in relation to a normative framework. A search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science, SCOPUS, JSTOR, Ovid, and Science Direct in March 2018, without language or date restriction. Data relating to the articles and the cases were extracted from case descriptions.

A total of 14,719 records were identified, and 388 items were included in the qualitative synthesis. The papers contained 500 case descriptions. After applying the eligibility criteria, 238 cases were included in the analysis. In the case analysis, fabrication and falsification were the most frequently tagged violations (44.9%). The non-adherence to pertinent laws and regulations, such as lack of informed consent and REC approval, was the second most frequently tagged violation (15.7%), followed by patient safety issues (11.1%) and plagiarism (6.9%). 80.8% of cases were from the Medical and Health Sciences, 11.5% from the Natural Sciences, 4.3% from Social Sciences, 2.1% from Engineering and Technology, and 1.3% from Humanities. Paper retraction was the most prevalent sanction (45.4%), followed by exclusion from funding applications (35.5%).

Conclusions

Case descriptions found in academic journals are dominated by discussions regarding prominent cases and are mainly published in the news section of journals. Our results show that there is an overrepresentation of biomedical research cases over other scientific fields compared to its proportion in scientific publications. The cases mostly involve fabrication, falsification, and patient safety issues. This finding could have a significant impact on the academic representation of misbehaviors. The predominance of fabrication and falsification cases might diverge the attention of the academic community from relevant but less visible violations, and from recently emerging forms of misbehaviors.

Peer Review reports

There has been an increase in academic interest in research ethics (RE) and research integrity (RI) over the past decade. This is due, among other reasons, to the changing research environment with new and complex technologies, increased pressure to publish, greater competition in grant applications, increased university-industry collaborative programs, and growth in international collaborations [ 1 ]. In addition, part of the academic interest in RE and RI is due to highly publicized cases of misconduct [ 2 ].

There is a growing body of published RE and RI cases, which may contribute to public attitudes regarding both science and scientists [ 3 ]. Different approaches have been used in order to analyze RE and RI cases. Studies focusing on ORI files (Office of Research Integrity) [ 2 ], retracted papers [ 4 ], quantitative surveys [ 5 ], data audits [ 6 ], and media coverage [ 3 ] have been conducted to understand the context, causes, and consequences of these cases.

Analyses of RE and RI cases often influence policies on responsible conduct of research [ 1 ]. Moreover, details about cases facilitate a broader understanding of issues related to RE and RI and can drive interventions to address them. Currently, there are no comprehensive studies that have collected and evaluated the RE and RI cases available in the academic literature. This review has been developed by members of the EnTIRE consortium to generate information on the cases that will be made available on the Embassy of Good Science platform ( www.embassy.science ). Two separate analyses have been conducted. The first analysis uses identified research articles to explore how the literature presents cases of RE and RI, in relation to the year of publication, country, article genre, and violation involved. The second analysis uses the cases extracted from the literature in order to characterize the cases and analyze them concerning the violations involved, sanctions, and field of science.

This scoping review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement and PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR). The full protocol was pre-registered and it is available at https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/documents/downloadPublic?documentIds=080166e5bde92120&appId=PPGMS .

Eligibility

Articles with non-fictional case(s) involving a violation of, or misbehavior, poor judgment, or detrimental research practice in relation to a normative framework, were included. Cases unrelated to scientific activities, research institutions, academic or industrial research and publication were excluded. Articles that did not contain a substantial description of the case were also excluded.

A normative framework consists of explicit rules, formulated in laws, regulations, codes, and guidelines, as well as implicit rules, which structure local research practices and influence the application of explicitly formulated rules. Therefore, if a case involves a violation of, or misbehavior, poor judgment, or detrimental research practice in relation to a normative framework, then it does so on the basis of explicit and/or implicit rules governing RE and RI practice.

Search strategy

A search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science, SCOPUS, JSTOR, Ovid, and Science Direct in March 2018, without any language or date restrictions. Two parallel searches were performed with two sets of medical subject heading (MeSH) terms, one for RE and another for RI. The parallel searches generated two sets of data thereby enabling us to analyze and further investigate the overlaps in, differences in, and evolution of, the representation of RE and RI cases in the academic literature. The terms used in the first search were: (("research ethics") AND (violation OR unethical OR misconduct)). The terms used in the parallel search were: (("research integrity") AND (violation OR unethical OR misconduct)). The search strategy’s validity was tested in a pilot search, in which different keyword combinations and search strings were used, and the abstracts of the first hundred hits in each database were read (Additional file 1 ).

After searching the databases with these two search strings, the titles and abstracts of extracted items were read by three contributors independently (ACVA, PK, and KB). Articles that could potentially meet the inclusion criteria were identified. After independent reading, the three contributors compared their results to determine which studies were to be included in the next stage. In case of a disagreement, items were reassessed in order to reach a consensus. Subsequently, qualified items were read in full.

Data extraction

Data extraction processes were divided by three assessors (ACVA, PK and KB). Each list of extracted data generated by one assessor was cross-checked by the other two. In case of any inconsistencies, the case was reassessed to reach a consensus. The following categories were employed to analyze the data of each extracted item (where available): (I) author(s); (II) title; (III) year of publication; (IV) country (according to the first author's affiliation); (V) article genre; (VI) year of the case; (VII) country in which the case took place; (VIII) institution(s) and person(s) involved; (IX) field of science (FOS-OECD classification)[ 7 ]; (X) types of violation (see below); (XI) case description; and (XII) consequences for persons or institutions involved in the case.

Two sets of data were created after the data extraction process. One set was used for the analysis of articles and their representation in the literature, and the other set was created for the analysis of cases. In the set for the analysis of articles, all eligible items, including duplicate cases (cases found in more than one paper, e.g. Hwang case, Baltimore case) were included. The aim was to understand the historical aspects of violations reported in the literature as well as the paper genre in which cases are described and discussed. For this set, the variables of the year of publication (III); country (IV); article genre (V); and types of violation (X) were analyzed.

For the analysis of cases, all duplicated cases and cases that did not contain enough information about particularities to differentiate them from others (e.g. names of the people or institutions involved, country, date) were excluded. In this set, prominent cases (i.e. those found in more than one paper) were listed only once, generating a set containing solely unique cases. These additional exclusion criteria were applied to avoid multiple representations of cases. For the analysis of cases, the variables: (VI) year of the case; (VII) country in which the case took place; (VIII) institution(s) and person(s) involved; (IX) field of science (FOS-OECD classification); (X) types of violation; (XI) case details; and (XII) consequences for persons or institutions involved in the case were considered.

Article genre classification

We used ten categories to capture the differences in genre. We included a case description in a “news” genre if a case was published in the news section of a scientific journal or newspaper. Although we have not developed a search strategy for newspaper articles, some of them (e.g. New York Times) are indexed in scientific databases such as Pubmed. The same method was used to allocate case descriptions to “editorial”, “commentary”, “misconduct notice”, “retraction notice”, “review”, “letter” or “book review”. We applied the “case analysis” genre if a case description included a normative analysis of the case. The “educational” genre was used when a case description was incorporated to illustrate RE and RI guidelines or institutional policies.

Categorization of violations

For the extraction process, we used the articles’ own terminology when describing violations/ethical issues involved in the event (e.g. plagiarism, falsification, ghost authorship, conflict of interest, etc.) to tag each article. In case the terminology was incompatible with the case description, other categories were added to the original terminology for the same case. Subsequently, the resulting list of terms was standardized using the list of major and minor misbehaviors developed by Bouter and colleagues [ 8 ]. This list consists of 60 items classified into four categories: Study design, data collection, reporting, and collaboration issues. (Additional file 2 ).

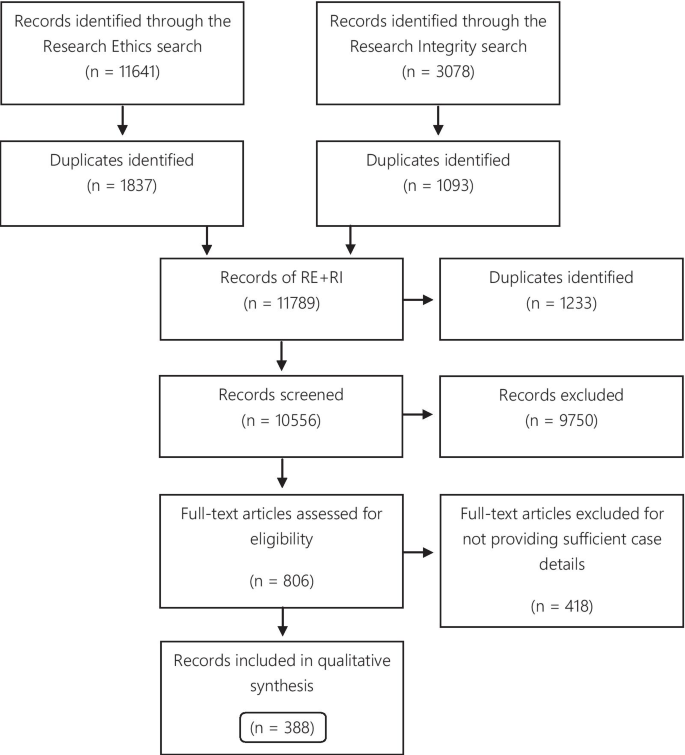

Systematic search

A total of 11,641 records were identified through the RE search and 3078 in the RI search. The results of the parallel searches were combined and the duplicates removed. The remaining 10,556 records were screened, and at this stage, 9750 items were excluded because they did not fulfill the inclusion criteria. 806 items were selected for full-text reading. Subsequently, 388 articles were included in the qualitative synthesis (Fig. 1 ).

Flow diagram

Of the 388 articles, 157 were only identified via the RE search, 87 exclusively via the RI search, and 144 were identified via both search strategies. The eligible articles contained 500 case descriptions, which were used for the analysis of the publications articles analysis. 256 case descriptions discussed the same 50 cases. The Hwang case was the most frequently described case, discussed in 27 articles. Furthermore, the top 10 most described cases were found in 132 articles (Table 1 ).

For the analysis of cases, 206 (41.2% of the case descriptions) duplicates were excluded, and 56 (11.2%) cases were excluded for not providing enough information to distinguish them from other cases, resulting in 238 eligible cases.

Analysis of the articles

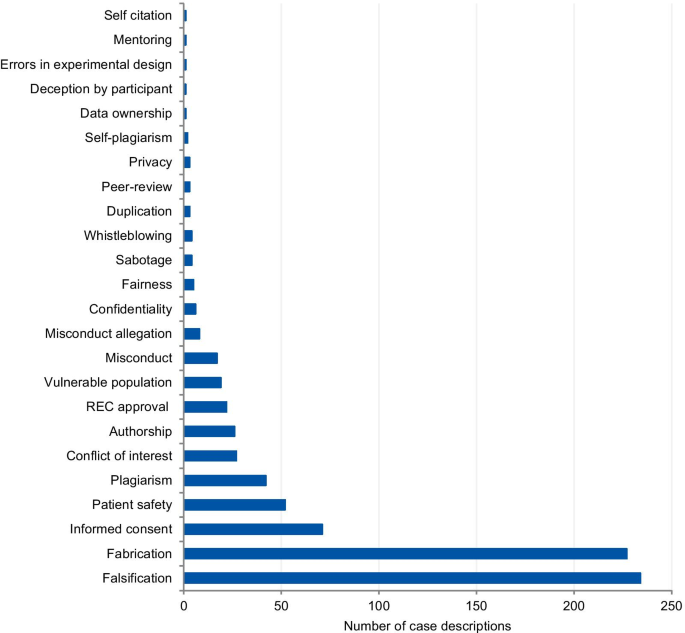

The categories used to classify the violations include those that pertain to the different kinds of scientific misconduct (falsification, fabrication, plagiarism), detrimental research practices (authorship issues, duplication, peer-review, errors in experimental design, and mentoring), and “other misconduct” (according to the definitions from the National Academies of Sciences and Medicine, [ 1 ]). Each case could involve more than one type of violation. The majority of cases presented more than one violation or ethical issue, with a mean of 1.56 violations per case. Figure 2 presents the frequency of each violation tagged to the articles. Falsification and fabrication were the most frequently tagged violations. The violations accounted respectively for 29.1% and 30.0% of the number of taggings (n = 780), and they were involved in 46.8% and 45.4% of the articles (n = 500 case descriptions). Problems with informed consent represented 9.1% of the number of taggings and 14% of the articles, followed by patient safety (6.7% and 10.4%) and plagiarism (5.4% and 8.4%). Detrimental research practices, such as authorship issues, duplication, peer-review, errors in experimental design, mentoring, and self-citation were mentioned cumulatively in 7.0% of the articles.

Tagged violations from the article analysis

Analysis of the cases

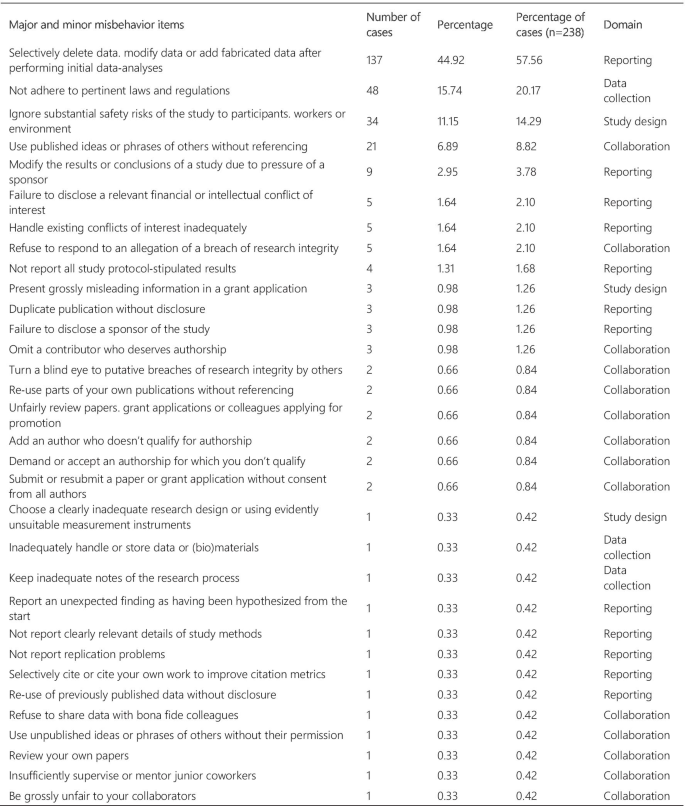

Figure 3 presents the frequency and percentage of each violation found in the cases. Each case could include more than one item from the list. The 238 cases were tagged 305 times, with a mean of 1.28 items per case. Fabrication and falsification were the most frequently tagged violations (44.9%), involved in 57.7% of the cases (n = 238). The non-adherence to pertinent laws and regulations, such as lack of informed consent and REC approval, was the second most frequently tagged violation (15.7%) and involved in 20.2% of the cases. Patient safety issues were the third most frequently tagged violations (11.1%), involved in 14.3% of the cases, followed by plagiarism (6.9% and 8.8%). The list of major and minor misbehaviors [ 8 ] classifies the items into study design, data collection, reporting, and collaboration issues. Our results show that 56.0% of the tagged violations involved issues in reporting, 16.4% in data collection, 15.1% involved collaboration issues, and 12.5% in the study design. The items in the original list that were not listed in the results were not involved in any case collected.

Major and minor misbehavior items from the analysis of cases

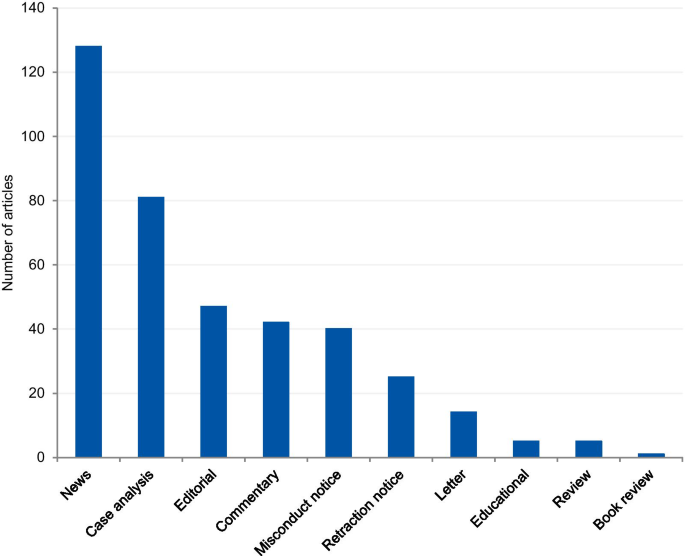

Article genre

The articles were mostly classified into “news” (33.0%), followed by “case analysis” (20.9%), “editorial” (12.1%), “commentary” (10.8%), “misconduct notice” (10.3%), “retraction notice” (6.4%), “letter” (3.6%), “educational paper” (1.3%), “review” (1%), and “book review” (0.3%) (Fig. 4 ). The articles classified into “news” and “case analysis” included predominantly prominent cases. Items classified into “news” often explored all the investigation findings step by step for the associated cases as the case progressed through investigations, and this might explain its high prevalence. The case analyses included mainly normative assessments of prominent cases. The misconduct and retraction notices included the largest number of unique cases, although a relatively large portion of the retraction and misconduct records could not be included because of insufficient case details. The articles classified into “editorial”, “commentary” and “letter” also included unique cases.

Article genre of included articles

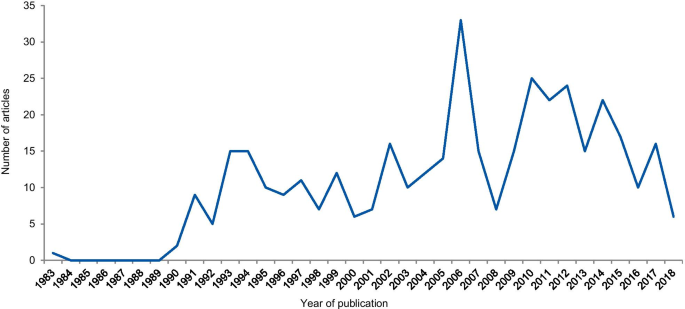

Article analysis

The dates of the eligible articles range from 1983 to 2018 with notable peaks between 1990 and 1996, most probably associated with the Gallo [ 9 ] and Imanishi-Kari cases [ 10 ], and around 2005 with the Hwang [ 11 ], Wakefield [ 12 ], and CNEP trial cases [ 13 ] (Fig. 5 ). The trend line shows an increase in the number of articles over the years.

Frequency of articles according to the year of publication

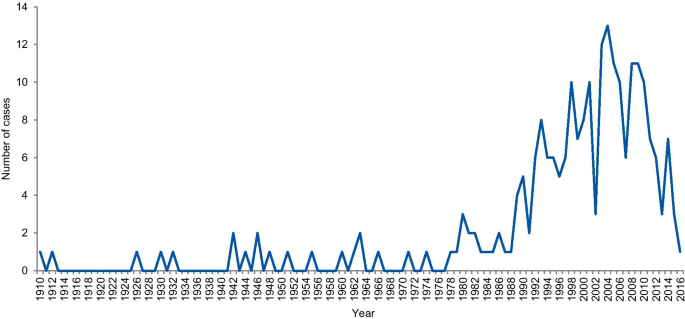

Case analysis

The dates of included cases range from 1798 to 2016. Two cases occurred before 1910, one in 1798 and the other in 1845. Figure 6 shows the number of cases per year from 1910. An increase in the curve started in the early 1980s, reaching the highest frequency in 2004 with 13 cases.

Frequency of cases per year

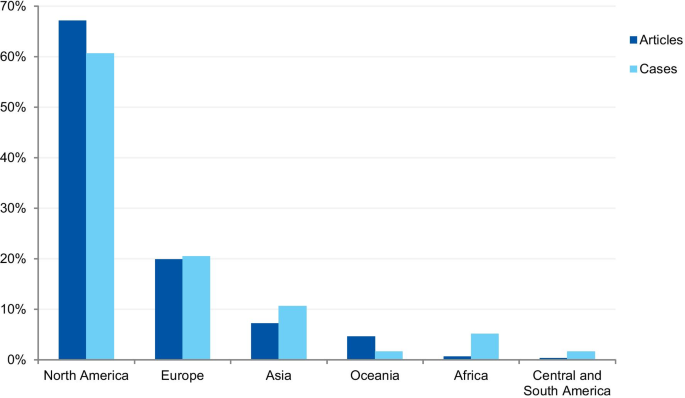

Geographical distribution

The first analysis concerned the authors’ affiliation and the corresponding author’s address. Where the article contained more than one country in the affiliation list, only the first author’s location was considered. Eighty-one articles were excluded because the authors’ affiliations were not available, and 307 articles were included in the analysis. The articles originated from 26 different countries (Additional file 3 ). Most of the articles emanated from the USA and the UK (61.9% and 14.3% of articles, respectively), followed by Canada (4.9%), Australia (3.3%), China (1.6%), Japan (1.6%), Korea (1.3%), and New Zealand (1.3%). Some of the most discussed cases occurred in the USA; the Imanishi-Kari, Gallo, and Schön cases [ 9 , 10 ]. Intensely discussed cases are also associated with Canada (Fisher/Poisson and Olivieri cases), the UK (Wakefield and CNEP trial cases), South Korea (Hwang case), and Japan (RIKEN case) [ 12 , 14 ]. In terms of percentages, North America and Europe stand out in the number of articles (Fig. 7 ).

Percentage of articles and cases by continent

The case analysis involved the location where the case took place, taking into account the institutions involved in the case. For cases involving more than one country, all the countries were considered. Three cases were excluded from the analysis due to insufficient information. In the case analysis, 40 countries were involved in 235 different cases (Additional file 4 ). Our findings show that most of the reported cases occurred in the USA and the United Kingdom (59.6% and 9.8% of cases, respectively). In addition, a number of cases occurred in Canada (6.0%), Japan (5.5%), China (2.1%), and Germany (2.1%). In terms of percentages, North America and Europe stand out in the number of cases (Fig. 7 ). To enable comparison, we have additionally collected the number of published documents according to country distribution, available on SCImago Journal & Country Rank [ 16 ]. The numbers correspond to the documents published from 1996 to 2019. The USA occupies the first place in the number of documents, with 21.9%, followed by China (11.1%), UK (6.3%), Germany (5.5%), and Japan (4.9%).

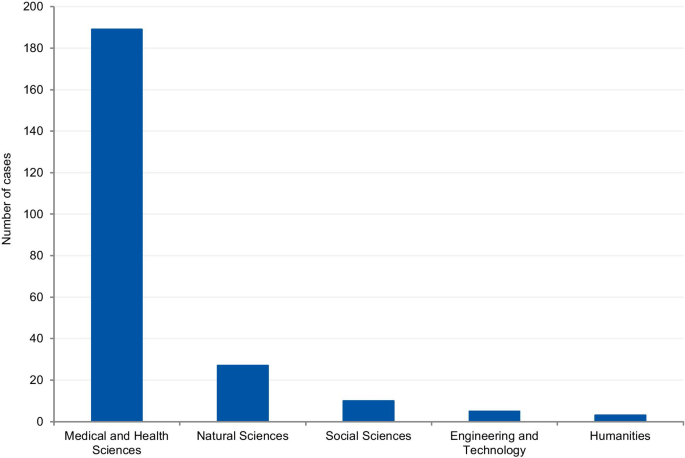

Field of science

The cases were classified according to the field of science. Four cases (1.7%) could not be classified due to insufficient information. Where information was available, 80.8% of cases were from the Medical and Health Sciences, 11.5% from the Natural Sciences, 4.3% from Social Sciences, 2.1% from Engineering and Technology, and 1.3% from Humanities (Fig. 8 ). Additionally, we have retrieved the number of published documents according to scientific field distribution, available on SCImago [ 16 ]. Of the total number of scientific publications, 41.5% are related to natural sciences, 22% to engineering, 25.1% to health and medical sciences, 7.8% to social sciences, 1.9% to agricultural sciences, and 1.7% to the humanities.

Field of science from the analysis of cases

This variable aimed to collect information on possible consequences and sanctions imposed by funding agencies, scientific journals and/or institutions. 97 cases could not be classified due to insufficient information. 141 cases were included. Each case could potentially include more than one outcome. Most of cases (45.4%) involved paper retraction, followed by exclusion from funding applications (35.5%). (Table 2 ).

RE and RI cases have been increasingly discussed publicly, affecting public attitudes towards scientists and raising awareness about ethical issues, violations, and their wider consequences [ 5 ]. Different approaches have been applied in order to quantify and address research misbehaviors [ 5 , 17 , 18 , 19 ]. However, most cases are investigated confidentially and the findings remain undisclosed even after the investigation [ 19 , 20 ]. Therefore, the study aimed to collect the RE and RI cases available in the scientific literature, understand how the cases are discussed, and identify the potential of case descriptions to raise awareness on RE and RI.

We collected and analyzed 500 detailed case descriptions from 388 articles and our results show that they mostly relate to extensively discussed and notorious cases. Approximately half of all included cases was mentioned in at least two different articles, and the top ten most commonly mentioned cases were discussed in 132 articles.

The prominence of certain cases in the literature, based on the number of duplicated cases we found (e.g. Hwang case), can be explained by the type of article in which cases are discussed and the type of violation involved in the case. In the article genre analysis, 33% of the cases were described in the news section of scientific publications. Our findings show that almost all article genres discuss those cases that are new and in vogue. Once the case appears in the public domain, it is intensely discussed in the media and by scientists, and some prominent cases have been discussed for more than 20 years (Table 1 ). Misconduct and retraction notices were exceptions in the article genre analysis, as they presented mostly unique cases. The misconduct notices were mainly found on the NIH repository, which is indexed in the searched databases. Some federal funding agencies like NIH usually publicize investigation findings associated with the research they fund. The results derived from the NIH repository also explains the large proportion of articles from the US (61.9%). However, in some cases, only a few details are provided about the case. For cases that have not received federal funding and have not been reported to federal authorities, the investigation is conducted by local institutions. In such instances, the reporting of findings depends on each institution’s policy and willingness to disclose information [ 21 ]. The other exception involves retraction notices. Despite the existence of ethical guidelines [ 22 ], there is no uniform and a common approach to how a journal should report a retraction. The Retraction Watch website suggests two lists of information that should be included in a retraction notice to satisfy the minimum and optimum requirements [ 22 , 23 ]. As well as disclosing the reason for the retraction and information regarding the retraction process, optimal notices should include: (I) the date when the journal was first alerted to potential problems; (II) details regarding institutional investigations and associated outcomes; (III) the effects on other papers published by the same authors; (IV) statements about more recent replications only if and when these have been validated by a third party; (V) details regarding the journal’s sanctions; and (VI) details regarding any lawsuits that have been filed regarding the case. The lack of transparency and information in retraction notices was also noted in studies that collected and evaluated retractions [ 24 ]. According to Resnik and Dinse [ 25 ], retractions notices related to cases of misconduct tend to avoid naming the specific violation involved in the case. This study found that only 32.8% of the notices identify the actual problem, such as fabrication, falsification, and plagiarism, and 58.8% reported the case as replication failure, loss of data, or error. Potential explanations for euphemisms and vague claims in retraction notices authored by editors could pertain to the possibility of legal actions from the authors, honest or self-reported errors, and lack of resources to conduct thorough investigations. In addition, the lack of transparency can also be explained by the conflicts of interests of the article’s author(s), since the notices are often written by the authors of the retracted article.

The analysis of violations/ethical issues shows the dominance of fabrication and falsification cases and explains the high prevalence of prominent cases. Non-adherence to laws and regulations (REC approval, informed consent, and data protection) was the second most prevalent issue, followed by patient safety, plagiarism, and conflicts of interest. The prevalence of the five most tagged violations in the case analysis was higher than the prevalence found in the analysis of articles that involved the same violations. The only exceptions are fabrication and falsification cases, which represented 45% of the tagged violations in the analysis of cases, and 59.1% in the article analysis. This disproportion shows a predilection for the publication of discussions related to fabrication and falsification when compared to other serious violations. Complex cases involving these types of violations make good headlines and this follows a custom pattern of writing about cases that catch the public and media’s attention [ 26 ]. The way cases of RE and RI violations are explored in the literature gives a sense that only a few scientists are “the bad apples” and they are usually discovered, investigated, and sanctioned accordingly. This implies that the integrity of science, in general, remains relatively untouched by these violations. However, studies on misconduct determinants show that scientific misconduct is a systemic problem, which involves not only individual factors, but structural and institutional factors as well, and that a combined effort is necessary to change this scenario [ 27 , 28 ].

Analysis of cases

A notable increase in RE and RI cases occurred in the 1990s, with a gradual increase until approximately 2006. This result is in agreement with studies that evaluated paper retractions [ 24 , 29 ]. Although our study did not focus only on retractions, the trend is similar. This increase in cases should not be attributed only to the increase in the number of publications, since studies that evaluated retractions show that the percentage of retraction due to fraud has increased almost ten times since 1975, compared to the total number of articles. Our results also show a gradual reduction in the number of cases from 2011 and a greater drop in 2015. However, this reduction should be considered cautiously because many investigations take years to complete and have their findings disclosed. ORI has shown that from 2001 to 2010 the investigation of their cases took an average of 20.48 months with a maximum investigation time of more than 9 years [ 24 ].

The countries from which most cases were reported were the USA (59.6%), the UK (9.8%), Canada (6.0%), Japan (5.5%), and China (2.1%). When analyzed by continent, the highest percentage of cases took place in North America, followed by Europe, Asia, Oceania, Latin America, and Africa. The predominance of cases from the USA is predictable, since the country publishes more scientific articles than any other country, with 21.8% of the total documents, according to SCImago [ 16 ]. However, the same interpretation does not apply to China, which occupies the second position in the ranking, with 11.2%. These differences in the geographical distribution were also found in a study that collected published research on research integrity [ 30 ]. The results found by Aubert Bonn and Pinxten (2019) show that studies in the United States accounted for more than half of the sample collected, and although China is one of the leaders in scientific publications, it represented only 0.7% of the sample. Our findings can also be explained by the search strategy that included only keywords in English. Since the majority of RE and RI cases are investigated and have their findings locally disclosed, the employment of English keywords and terms in the search strategy is a limitation. Moreover, our findings do not allow us to draw inferences regarding the incidence or prevalence of misconduct around the world. Instead, it shows where there is a culture of publicly disclosing information and openly discussing RE and RI cases in English documents.

Scientific field analysis

The results show that 80.8% of reported cases occurred in the medical and health sciences whilst only 1.3% occurred in the humanities. This disciplinary difference has also been observed in studies on research integrity climates. A study conducted by Haven and colleagues, [ 28 ] associated seven subscales of research climate with the disciplinary field. The subscales included: (1) Responsible Conduct of Research (RCR) resources, (2) regulatory quality, (3) integrity norms, (4) integrity socialization, (5) supervisor/supervisee relations, (6) (lack of) integrity inhibitors, and (7) expectations. The results, based on the seven subscale scores, show that researchers from the humanities and social sciences have the lowest perception of the RI climate. By contrast, the natural sciences expressed the highest perception of the RI climate, followed by the biomedical sciences. There are also significant differences in the depth and extent of the regulatory environments of different disciplines (e.g. the existence of laws, codes of conduct, policies, relevant ethics committees, or authorities). These findings corroborate our results, as those areas of science most familiar with RI tend to explore the subject further, and, consequently, are more likely to publish case details. Although the volume of published research in each research area also influences the number of cases, the predominance of medical and health sciences cases is not aligned with the trends regarding the volume of published research. According to SCImago Journal & Country Rank [ 16 ], natural sciences occupy the first place in the number of publications (41,5%), followed by the medical and health sciences (25,1%), engineering (22%), social sciences (7,8%), and the humanities (1,7%). Moreover, biomedical journals are overrepresented in the top scientific journals by IF ranking, and these journals usually have clear policies for research misconduct. High-impact journals are more likely to have higher visibility and scrutiny, and consequently, more likely to have been the subject of misconduct investigations. Additionally, the most well-known general medical journals, including NEJM, The Lancet, and the BMJ, employ journalists to write their news sections. Since these journals have the resources to produce extensive news sections, it is, therefore, more likely that medical cases will be discussed.

Violations analysis

In the analysis of violations, the cases were categorized into major and minor misbehaviors. Most cases involved data fabrication and falsification, followed by cases involving non-adherence to laws and regulations, patient safety, plagiarism, and conflicts of interest. When classified by categories, 12.5% of the tagged violations involved issues in the study design, 16.4% in data collection, 56.0% in reporting, and 15.1% involved collaboration issues. Approximately 80% of the tagged violations involved serious research misbehaviors, based on the ranking of research misbehaviors proposed by Bouter and colleagues. However, as demonstrated in a meta-analysis by Fanelli (2009), most self-declared cases involve questionable research practices. In the meta-analysis, 33.7% of scientists admitted questionable research practices, and 72% admitted when asked about the behavior of colleagues. This finding contrasts with an admission rate of 1.97% and 14.12% for cases involving fabrication, falsification, and plagiarism. However, Fanelli’s meta-analysis does not include data about research misbehaviors in its wider sense but focuses on behaviors that bias research results (i.e. fabrication and falsification, intentional non-publication of results, biased methodology, misleading reporting). In our study, the majority of cases involved FFP (66.4%). Overrepresentation of some types of violations, and underrepresentation of others, might lead to misguided efforts, as cases that receive intense publicity eventually influence policies relating to scientific misconduct and RI [ 20 ].

Sanctions analysis

The five most prevalent outcomes were paper retraction, followed by exclusion from funding applications, exclusion from service or position, dismissal and suspension, and paper correction. This result is similar to that found by Redman and Merz [ 31 ], who collected data from misconduct cases provided by the ORI. Moreover, their results show that fabrication and falsification cases are 8.8 times more likely than others to receive funding exclusions. Such cases also received, on average, 0.6 more sanctions per case. Punishments for misconduct remain under discussion, ranging from the criminalization of more serious forms of misconduct [ 32 ] to social punishments, such as those recently introduced by China [ 33 ]. The most common sanction identified by our analysis—paper retraction—is consistent with the most prevalent types of violation, that is, falsification and fabrication.

Publicizing scientific misconduct

The lack of publicly available summaries of misconduct investigations makes it difficult to share experiences and evaluate the effectiveness of policies and training programs. Publicizing scientific misconduct can have serious consequences and creates a stigma around those involved in the case. For instance, publicized allegations can damage the reputation of the accused even when they are later exonerated [ 21 ]. Thus, for published cases, it is the responsibility of the authors and editors to determine whether the name(s) of those involved should be disclosed. On the one hand, it is envisaged that disclosing the name(s) of those involved will encourage others in the community to foster good standards. On the other hand, it is suggested that someone who has made a mistake should have the right to a chance to defend his/her reputation. Regardless of whether a person's name is left out or disclosed, case reports have an important educational function and can help guide RE- and RI-related policies [ 34 ]. A recent paper published by Gunsalus [ 35 ] proposes a three-part approach to strengthen transparency in misconduct investigations. The first part consists of a checklist [ 36 ]. The second suggests that an external peer reviewer should be involved in investigative reporting. The third part calls for the publication of the peer reviewer’s findings.

Limitations

One of the possible limitations of our study may be our search strategy. Although we have conducted pilot searches and sensitivity tests to reach the most feasible and precise search strategy, we cannot exclude the possibility of having missed important cases. Furthermore, the use of English keywords was another limitation of our search. Since most investigations are performed locally and published in local repositories, our search only allowed us to access cases from English-speaking countries or discussed in academic publications written in English. Additionally, it is important to note that the published cases are not representative of all instances of misconduct, since most of them are never discovered, and when discovered, not all are fully investigated or have their findings published. It is also important to note that the lack of information from the extracted case descriptions is a limitation that affects the interpretation of our results. In our review, only 25 retraction notices contained sufficient information that allowed us to include them in our analysis in conformance with the inclusion criteria. Although our search strategy was not focused specifically on retraction and misconduct notices, we believe that if sufficiently detailed information was available in such notices, the search strategy would have identified them.

Case descriptions found in academic journals are dominated by discussions regarding prominent cases and are mainly published in the news section of journals. Our results show that there is an overrepresentation of biomedical research cases over other scientific fields when compared with the volume of publications produced by each field. Moreover, published cases mostly involve fabrication, falsification, and patient safety issues. This finding could have a significant impact on the academic representation of ethical issues for RE and RI. The predominance of fabrication and falsification cases might diverge the attention of the academic community from relevant but less visible violations and ethical issues, and recently emerging forms of misbehaviors.

Availability of data and materials

This review has been developed by members of the EnTIRE project in order to generate information on the cases that will be made available on the Embassy of Good Science platform ( www.embassy.science ). The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the Open Science Framework (OSF) repository in https://osf.io/3xatj/?view_only=313a0477ab554b7489ee52d3046398b9 .

National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine. Fostering integrity in research. National Academies Press; 2017.

Davis MS, Riske-Morris M, Diaz SR. Causal factors implicated in research misconduct: evidence from ORI case files. Sci Eng Ethics. 2007;13(4):395–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-007-9045-2 .

Article Google Scholar

Ampollini I, Bucchi M. When public discourse mirrors academic debate: research integrity in the media. Sci Eng Ethics. 2020;26(1):451–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-019-00103-5 .

Hesselmann F, Graf V, Schmidt M, Reinhart M. The visibility of scientific misconduct: a review of the literature on retracted journal articles. Curr Sociol La Sociologie contemporaine. 2017;65(6):814–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392116663807 .

Martinson BC, Anderson MS, de Vries R. Scientists behaving badly. Nature. 2005;435(7043):737–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/435737a .

Loikith L, Bauchwitz R. The essential need for research misconduct allegation audits. Sci Eng Ethics. 2016;22(4):1027–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-016-9798-6 .

OECD. Revised field of science and technology (FoS) classification in the Frascati manual. Working Party of National Experts on Science and Technology Indicators 2007. p. 1–12.

Bouter LM, Tijdink J, Axelsen N, Martinson BC, ter Riet G. Ranking major and minor research misbehaviors: results from a survey among participants of four World Conferences on Research Integrity. Res Integrity Peer Rev. 2016;1(1):17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-016-0024-5 .

Greenberg DS. Resounding echoes of Gallo case. Lancet. 1995;345(8950):639.

Dresser R. Giving scientists their due. The Imanishi-Kari decision. Hastings Center Rep. 1997;27(3):26–8.

Hong ST. We should not forget lessons learned from the Woo Suk Hwang’s case of research misconduct and bioethics law violation. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31(11):1671–2. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2016.31.11.1671 .

Opel DJ, Diekema DS, Marcuse EK. Assuring research integrity in the wake of Wakefield. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2011;342(7790):179. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d2 .

Wells F. The Stoke CNEP Saga: did it need to take so long? J R Soc Med. 2010;103(9):352–6. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2010.10k010 .

Normile D. RIKEN panel finds misconduct in controversial paper. Science. 2014;344(6179):23. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.344.6179.23 .

Wager E. The Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE): Objectives and achievements 1997–2012. La Presse Médicale. 2012;41(9):861–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lpm.2012.02.049 .

SCImago nd. SJR — SCImago Journal & Country Rank [Portal]. http://www.scimagojr.com . Accessed 03 Feb 2021.

Fanelli D. How many scientists fabricate and falsify research? A systematic review and meta-analysis of survey data. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(5):e5738. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0005738 .

Steneck NH. Fostering integrity in research: definitions, current knowledge, and future directions. Sci Eng Ethics. 2006;12(1):53–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00022268 .

DuBois JM, Anderson EE, Chibnall J, Carroll K, Gibb T, Ogbuka C, et al. Understanding research misconduct: a comparative analysis of 120 cases of professional wrongdoing. Account Res. 2013;20(5–6):320–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2013.822248 .

National Academy of Sciences NAoE, Institute of Medicine Panel on Scientific R, the Conduct of R. Responsible Science: Ensuring the Integrity of the Research Process: Volume I. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) Copyright (c) 1992 by the National Academy of Sciences; 1992.

Bauchner H, Fontanarosa PB, Flanagin A, Thornton J. Scientific misconduct and medical journals. JAMA. 2018;320(19):1985–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.14350 .

COPE Council. COPE Guidelines: Retraction Guidelines. 2019. https://doi.org/10.24318/cope.2019.1.4 .

Retraction Watch. What should an ideal retraction notice look like? 2015, May 21. https://retractionwatch.com/2015/05/21/what-should-an-ideal-retraction-notice-look-like/ .

Fang FC, Steen RG, Casadevall A. Misconduct accounts for the majority of retracted scientific publications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(42):17028–33. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1212247109 .

Resnik DB, Dinse GE. Scientific retractions and corrections related to misconduct findings. J Med Ethics. 2013;39(1):46–50. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2012-100766 .

de Vries R, Anderson MS, Martinson BC. Normal misbehavior: scientists talk about the ethics of research. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics JERHRE. 2006;1(1):43–50. https://doi.org/10.1525/jer.2006.1.1.43 .

Sovacool BK. Exploring scientific misconduct: isolated individuals, impure institutions, or an inevitable idiom of modern science? J Bioethical Inquiry. 2008;5(4):271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-008-9113-6 .

Haven TL, Tijdink JK, Martinson BC, Bouter LM. Perceptions of research integrity climate differ between academic ranks and disciplinary fields: results from a survey among academic researchers in Amsterdam. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(1):e0210599. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210599 .

Trikalinos NA, Evangelou E, Ioannidis JPA. Falsified papers in high-impact journals were slow to retract and indistinguishable from nonfraudulent papers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(5):464–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.019 .

Aubert Bonn N, Pinxten W. A decade of empirical research on research integrity: What have we (not) looked at? J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2019;14(4):338–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1556264619858534 .

Redman BK, Merz JF. Scientific misconduct: do the punishments fit the crime? Science. 2008;321(5890):775. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1158052 .

Bülow W, Helgesson G. Criminalization of scientific misconduct. Med Health Care Philos. 2019;22(2):245–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-018-9865-7 .

Cyranoski D. China introduces “social” punishments for scientific misconduct. Nature. 2018;564(7736):312. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-07740-z .

Bird SJ. Publicizing scientific misconduct and its consequences. Sci Eng Ethics. 2004;10(3):435–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-004-0001-0 .

Gunsalus CK. Make reports of research misconduct public. Nature. 2019;570(7759):7. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-01728-z .

Gunsalus CK, Marcus AR, Oransky I. Institutional research misconduct reports need more credibility. JAMA. 2018;319(13):1315–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.0358 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the EnTIRE research group. The EnTIRE project (Mapping Normative Frameworks for Ethics and Integrity of Research) aims to create an online platform that makes RE+RI information easily accessible to the research community. The EnTIRE Consortium is composed by VU Medical Center, Amsterdam, gesinn. It Gmbh & Co Kg, KU Leuven, University of Split School of Medicine, Dublin City University, Central European University, University of Oslo, University of Manchester, European Network of Research Ethics Committees.

EnTIRE project (Mapping Normative Frameworks for Ethics and Integrity of Research) has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement N 741782. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Behavioural Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Debrecen, Móricz Zsigmond krt. 22. III. Apartman Diákszálló, Debrecen, 4032, Hungary

Anna Catharina Vieira Armond & János Kristóf Bodnár

Institute of Ethics, School of Theology, Philosophy and Music, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland

Bert Gordijn, Jonathan Lewis & Mohammad Hosseini

Centre for Social Ethics and Policy, School of Law, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK

Center for Medical Ethics, HELSAM, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

Center for Ethics and Law in Biomedicine, Central European University, Budapest, Hungary

Péter Kakuk

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors (ACVA, BG, JL, MH, JKB, SH and PK) developed the idea for the article. ACVA, PK, JKB performed the literature search and data analysis, ACVA and PK produced the draft, and all authors critically revised it. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Anna Catharina Vieira Armond .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

. Pilot search and search strategy.

Additional file 2

. List of Major and minor misbehavior items (Developed by Bouter LM, Tijdink J, Axelsen N, Martinson BC, ter Riet G. Ranking major and minor research misbehaviors: results from a survey among participants of four World Conferences on Research Integrity. Research integrity and peer review. 2016;1(1):17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-016-0024-5 ).

Additional file 3

. Table containing the number and percentage of countries included in the analysis of articles.

Additional file 4

. Table containing the number and percentage of countries included in the analysis of the cases.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Armond, A.C.V., Gordijn, B., Lewis, J. et al. A scoping review of the literature featuring research ethics and research integrity cases. BMC Med Ethics 22 , 50 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-021-00620-8

Download citation

Received : 06 October 2020

Accepted : 21 April 2021

Published : 30 April 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-021-00620-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Research ethics

- Research integrity

- Scientific misconduct

BMC Medical Ethics

ISSN: 1472-6939

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- OpenBU

- BU Open Access Articles

Cases of ethical violation in research publications: through editorial decision making process

Date Issued

Publisher version.

Export Citation

Permanent link, citation (published version), collections.

- BU Open Access Articles [6228]

- MET: Scholarly Works [167]

Deposit Materials

McCombs School of Business

- Español ( Spanish )