- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Submit?

- About Journal of Communication

- About International Communication Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Media flows and technological/industrial change, netflix library composition: a study of 17 countries, data access, acknowledgments.

- < Previous

Netflix, library analysis, and globalization: rethinking mass media flows

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Amanda D Lotz, Oliver Eklund, Stuart Soroka, Netflix, library analysis, and globalization: rethinking mass media flows, Journal of Communication , Volume 72, Issue 4, August 2022, Pages 511–521, https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqac020

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The advent of subscriber-funded, direct-to-consumer, streaming video services has important implications for video distribution around the globe. Conversations about transnational media flows and power—a core concern of critical communication studies—have only just begun to explore these changes. This article investigates how global streamers challenge existing communication and media theory about transnational video and its cultural power and considers the theory rebuilding necessitated by streamers’ discrepant features. It takes particular focus on Netflix and uses the library data available from Ampere Analysis to empirically explore and compare 17 national libraries. Analyses suggest considerable variation in the contents of Netflix libraries cross-nationally, in contrast with other U.S.-based services, as well as Netflix libraries offering content produced in a greater range of countries. These and other results illustrate, albeit indirectly, the operations and strategies of global streamers, which then inform theory building regarding their cultural role.

As is often the case in technological innovation, thinking about streaming services has been structured by the capabilities and protocols of similar technologies that came before. A century ago AT&T imagined radio through the lens of the telephone, though failed to make radio a point-to-point technology, while television largely adopted regulatory norms and scheduling features from radio. Industry, policymakers, and scholars now attempt to slot streaming video services into our conceptual understandings of previous video providers that used broadcast signal, cable, or satellite to distribute content to the home.

However, Internet-distributed video both is and isn’t comparable to these previous technologies. Indeed, even Internet-distributed video may be too varied a category to make substantive claims—TikTok and YouTube operate under very different industrial conditions than Netflix and Disney+, though all offer Internet-distributed video. The latter services, also identified as subscription, video-on-demand services (hereafter, “streamers”), provide the focus here. As video services, streamers do important cultural work in society by producing and circulating stories that, like other audiovisual services, mostly reinforce, but sometimes contradict hegemonic ideas and contribute to culture shared by many ( Fiske, 1987 ; Gitlin, 1979 ; Newcomb & Hirsch, 1983 ). But they are also different from previous distribution technologies upon which foundational theories were built, and these differences require revising or reframing theory. Moreover, the industrial context of the 21st century, which is characterized by much greater choice in services (channels and streamers) and substantial audience fragmentation across these choices, also necessitates adjustment of theories that were developed for norms of limited choice and mass audiences. In terms of critical communication/media studies scholarship, the three most important differences are: Streamers’ reliance on subscriber support, their ability to deliver bespoke content on demand, and their ability to be offered at a near-global scale. These features allow different business strategies that yield different content priorities and different cultures of consumption than characteristic of previous distribution technologies that provide the foundation of the field’s thinking.

Subscriber funding alters the core business of streamers from the commercial norms of advertiser funding in profound ways ( Lotz, 2007 , 2017 ). The need to compel viewers to pay and the ability to offer a range of titles simultaneously—rather than a single title most likely to attract the most viewers—enables, even requires, different content strategies than have been used by video services that seek to attract the most attention to particular titles at a specified time. Streamers have accelerated the transition from mass to niche video industry logics that had been developing since the widespread adoption of cable and satellite in the 1990s. The ubiquitous accessibility of broadcasting that was core to theories about the cultural power of in-home video also diminishes as a consequence of these different affordances ( Lotz, 2021b ).

The global reach of several of the most widely subscribed streamers integrates them in conversations about transnational media flows and power that have been a core concern of critical communication studies. Video media businesses have been transnational since technology made video trade feasible ( Steemers, 2004 ; Havens, 2006 ), yet the last quarter of a century has accelerated and reconfigured the internationalization of video businesses and video consumption ( Lobato, 2019 ; Steemers, 2016 ). The rapid expansion of global streaming services has hastened the erosion of once-nationally organized video sectors and substantially altered legacy businesses of transnational television trade, their industrial priorities, and the accessibility of video produced outside the long-dominant Hollywood system.

This article investigates how global streamers challenge existing communication and media theory about transnational video and its cultural power. It considers how streamers’ discrepant features combine with coterminous, but unrelated disruption from previous industrial norms and conditions to necessitate theory rebuilding. These adjustments have implications for key theories and assumptions about the dynamics of power involved in media trade, including those about corporate ownership ( de Sola Pool, 1979 ; Schiller, 1969 ; Tunstall, 1977 ), proximity ( Straubhaar, 1991 ; 2007 ), asymmetrical interdependence ( Straubhaar, 1991 ; Straubhaar et al., 2021 ), cultural discount ( Hoskins and Mirus, 1988 ), contra-flow ( Thussu, 2006 ), and the roles of geography, language, and culture in explaining patterns of video flow ( Sinclair et al., 1996 ).

This article takes particular focus on Netflix as a streaming service utilizing the most distinctive strategy, such that Lotz (2021a) has described it as a “zebra among horses” in a multifaceted analysis of its “global” strategy. Relying on datasets obtained through subscription to Ampere Analysis, 1 the article uses Netflix’s library composition in different countries to investigate what the titles in these libraries suggest about streamers’ contribution to the transnational flow of video content. It also juxtaposes evidence derived from comparing Netflix’s library strategy with other major, transnational services to illustrate its distinction. The article queries the extent to which streamers with global reach do and do not replicate the industrial practices of linear video services (broadcast, cable, satellite) and consequently how our theories about transnational cultural influence may require nuance.

The investigation is limited by the inaccessibility of the most useful data for answering these questions: data regarding audience use. There is nevertheless much to learn from a focus on library composition. Indeed, title-level data including country of origin facilitates analyses that provide sophisticated understandings of what these services are and what they offer viewers and is useful for assessing the complementarity of these services along with their widely assumed competition. Is Netflix a global behemoth capable of exerting enormous cultural and market influence in the manner its occasional inclusion among abusive “tech giants” suggests and thus in need of policy intervention? If so, is it cultural or competition policy that is warranted? Does its strong market capitalization and scale eliminate the viability of domestic services in the many markets it services? Or does its scale enable it to function as a complement to domestic services with different priorities (e.g., public service or nation-specific commercial broadcasters) and its library strategy suggest it offers viewers an experience not otherwise available?

This article examines evidence relevant to established theories and persistent presumptions in the field regarding the implications of nationality of ownership of conglomerates, the cultural specificity indicated by titles’ country of production, and preferences for local content. It follows critiques that dominant theories have overstated physical proximity and the relevance of the nation as the primary site of cultural connection in a way that has exaggerated the frame of the nation in the questions we prioritize ( Morley & Robbins, 1995 ; Esser, 2016 ), although country of origin provides a useful categorization for preliminary assessment of streamers’ libraries. Such theories derive from the stronger national organization of predigital distribution technologies and have informed policy and come to be “industry lore” ( Havens, 2014 ) but do not adequately account for the complexity of viewing practices now common, especially with regard to such expanded choice. The inquiry here does not aim to assert flaws with the previous emphasis on proximity and national specificity. Rather, it explores how the industrial context in which these theories were developed was circumscribed by mechanisms and practices that substantively narrowed available content in a manner never accounted for because those mechanisms appeared so natural they obscured counter explanations.

The broader significance of this inquiry relates to how new distribution technologies—and the different business models they enable—challenge existing theoretical frameworks. Within critical cultural studies, decades of norms developed for linear, mostly ad-supported channels produced particular hegemonies of industry operation and hegemonies of scholarly thinking about them. The differences in business model and the lack of publicly accessible viewership data have made it difficult to assess how subscriber-funded video services may deviate from conditions previously theorized. This analysis informs that conversation by exploring streamers’ national libraries to begin to reveal the differences among global streamers and enable assessment of their cultural role.

The ideas that American movies and series dominate the globe and that viewers prefer “proximate” content are among the least contested ideas in critical media studies—despite their apparent contradiction. The assertion that U.S. media enacts cultural imperialism ( Schiller, 1969 ) has been difficult to dislodge, although it has been extensively critiqued ( Tomlinson, 1991 ; Golding & Harris, 1997 ). While there was and remains imbalance in flows, the implications of that imbalance on culture have not been empirically shown.

Rather than being driven by political power and ideological aims, economic logics—with their own ideological concerns—better explain decades of U.S. dominance in audiovisual production and trade. As Hoskins and Mirus (1988) explain, the scale and wealth of the U.S. market created incredible advantages in exporting movies and series. They argue U.S. titles derived less of a “cultural discount” because so many markets had been “acclimatized to Hollywood product,” despite a preference for what Straubhaar (1991) terms “proximate” content. In practice, the need to create titles for an expansive and heterogeneous American mass market led to productions that planed off a lot of cultural specificity, and many of the most popular titles emphasized universal themes such as family dynamics or narrative pleasures such as mystery resolution. Indeed, the “style, values, beliefs, institutions, and behavioral patterns” ( Hoskins & Mirus, 1988 , p. 500) found in U.S. titles were often as foreign to many Americans as to those who viewed them from around the globe. This is not to say that such titles are not imbued with belief structures pervasive in American culture—for example surrounding individualism—but to note we lack detailed scholarship grounded in textual analysis of what characteristics make titles specifically and exclusively “American.” Instead, country of production has been assumed indicative of cultural features.

Cultural and economic concerns have become complicatedly intertwined over time, both in national policy and scholarship regarding audiovisual industries. In many countries, cultural policies such as local content quotas, as well as supports and subsidies for domestic productions or national/public broadcasters, aimed to prevent imported content from dominating or inhibiting local production. Many of these policies were effective through the twentieth century, as countries found a balance that enabled coexistence of domestic and foreign content.

Substantial changes in industrial dynamics that increased the pressure to achieve transnational audience scale have steadily eroded this balance. Satellite channels and their appetite for programming encouraged greater internationalization ( Chalaby, 2005 ) that has since been expanded by multi-territory streaming services. Appeals to governments to increase supports of “cultural industries” on economic grounds have led economic metrics and sector growth to sublimate what were initially cultural policies and led some to prioritize national production output as a metric that has become conflated with delivering effective cultural policy—though such sector supports offer little to ensure productions take on attributes sought by cultural policy such as local identity, character, and cultural diversity ( Lotz & Potter, 2022 ). Sector advocates assume a title produced in Australia—even if an American “runaway” production—inherently delivers Australian cultural value as well as economic value; however, broader industrial changes have disrupted market forces that compelled domestic content as a key strategy of domestic channels to attract the attention of domestic audiences. The weakening of domestic channels (in the face of new advertising tools such as search and social media that have drawn advertiser spending) has resulted in the imagined audience for series and movies to be decreasingly presumed as domestic in the first instance.

The national dynamics of production and circulation ecosystems are also now far more complicated than when most media studies theory was written. Subscribers in countries around the world choose to pay monthly for access to services featuring minimal local content and, as the analysis below indicates, Netflix offers libraries made up of mostly foreign—though not American—content in all markets. This is not to suggest that the concerns about power central in earlier scholarship about ownership and country of origin are invalid, rather that the conditions for the operation of that power have changed in ways that require retheorization that accounts for the more multifaceted dynamics of the 21st century.

Proximity, the idea that “Most audiences seem to prefer television programs that are as close to them as possible in language, ethnic appearance, dress, style, humor, historical reference, and shared topical knowledge” ( Straubhaar, 2007 , p. 26) developed from empirical evidence, but evidence collected at a time when far less channel/program choice existed. With his decades-long trajectory of research, Straubhaar (1991) provided one of the first empirical interventions into ideas about cultural imperialism that assumed country of origin functioned as a strong indicator of cultural effects and dominated early understandings of the implications of the spread of American media content around the world. Straubhaar’s theory of “asymmetrical interdependence” addressed how early importation levels were tied to a first stage of national broadcasting development. By investigating when imported content was scheduled (often outside prime viewing hours), Straubhaar (2007) developed a more nuanced picture than provided by macro level data of raw imports used to argue U.S. hegemony.

Research developed since the height of belief in cultural imperialism identified significant sub-flows of content that could be explained by geo-cultural or cultural-linguistic proximity ( Sinclair et al., 1996 ). The priority of proximity transcended scholarship and even became common in industry discourse. This encouraged a surge in the development of “reality” program formats that could be sold across markets and remade with market specificity in the early 2000s as titles such as Big Brother , Pop Idol , and Weakest Link blanketed the globe ( Waisbord, 2004 ). These formats avoided the level of concern that exports of Dragnet , Dallas , and Baywatch inspired earlier because they enabled “customization,” a deliberate distinction drawn by Moran (against localization) because the shows still aim at national audiences and lack specification to local communities ( Moran, 2009 , p. 157). 2

Like cultural imperialism, the idea that viewers would prefer proximate content is a theory that makes sense on its face. In later work, Straubhaar and La Pastina (2007) extended the concept to include other forms of proximity, such as genres, themes, and values, though these ideas were difficult to test without extensive audience research and pushed more into the psychology of individual preference. In recent work that accounts for streamers—but does not include updated audience research— Straubhaar et al. (2021) back away from proximity and instead suggest evidence of new permutations of asymmetrical interdependence. The scale at which households have adopted—and willingly pay for—streamers services that offer no or negligible domestic content suggests the limits of proximity, or at least that there are other motivations driving viewers. In the pre-multichannel industrial context of limited choice and prioritization on constructing mass audiences, these other motivations would have been difficult to recognize; it would have required audiences to identify a preference for something absent from the market. However, the adoption of streaming services with library strategies quite different from past scheduling norms begins to suggest the existence of these alternative motivations.

Though Straubhaar et al. (2021) engage in speculation about motives based on theories of cosmopolitanism, what is most required to answer these questions is audience research with the qualitative sophistication offered by those who have contributed foundational insights about cultural practices of viewing (e.g., Gray, 1992; Morley, 1986 ; Wood, 2009 ) to assess the complicated cultural roles and ideological processes of the fictional storytelling pervasive among streaming services. In the absence of audience data, this study compares Netflix’s offerings across 17 different national markets to introduce deeper understanding of its library composition and to illustrate how simple categorization of it as “American” and similar to other streaming services offered by American companies leads to facile understanding. Qualitative interviews and complex multi-method approaches are needed to theorize the behavior of viewers who choose streaming services, work that remains rare given its costs and challenges. Until such studies emerge, however, we can develop more comprehensive accounts of the differences between the current industrial context and the context in place when foundational theory was established. Inspired by the insights produced by Straubhaar’s examination of scheduling, we conduct systematic analysis of Netflix libraries.

Twentieth-century television and distribution technologies—the context in which most communication and media studies theories about the operation of “mass storytelling” in culture were built—offered viewers the metaphorical tip of the iceberg in terms of the range of stories perceived as commercially viable. Most programs were designed to attract the most attention—foremost in their nation of production—but by the 1990s, the need for U.S. content to be accessible and desired by viewers around the globe also provided a guiding industrial logic for what was made for U.S. audiences. Viewer choice was constrained, though not strongly perceived as such because the condition of channels selecting programs and making them available at particular times was simply “normal.” Though cable and satellite introduced more choice through more channels, most programming on those channels was merely a reairing of series made for ad-supported linear channels or movies made for theatrical release.

Twenty-first-century video distribution technologies have revealed much more of the storytelling iceberg. Internet distribution has enabled direct-to-consumer, subscriber-funded, on-demand video services that access different commercial strategies and utilize different metrics of success ( Lotz, 2022 ). As a result, they have expanded the content fields available to the consumers who choose and can afford to access them.

In order to investigate the similarity and difference across Netflix libraries, this study uses title-level library data captured by Ampere Analysis, the leading commercial data analytics company in the transnational streaming sector. Knowing what people watch would be especially valuable, but library data allows us to appreciate what these services offer, how the offerings of the services differ, and how those offerings compare with linear, ad-supported services. Moreover, Netflix uses vast amounts of behavioral data in its selection of titles for both commissioning and licensing. 3 Thus, at this established stage of Netflix’s global distribution, it is reasonable to expect that Netflix curates its libraries in response to insight about what is watched. To be clear, this analysis does not argue library composition provides accurate information about viewing differences across nations, but it is the case that the service has proprietary access to substantially more detailed information about viewer behavior than has ever been the case. As Cunningham and Craig (2019) identify, the company developed from a “tech” mindset that foregrounds data-based decision making over the “instinct” long claimed central to television and film making in contexts where individual-specific behavior data has never been available.

Analyzing Netflix libraries can add to our understanding of how transnational streamers blend local and global features in new and old ways. Netflix reaches subscribers in more than 190 countries and thus is generally regarded as “globally” available, although its rates of household penetration vary significantly by nation. It has only released data about subscribers at a “regional” level: At year end 2021, Netflix recorded 75.2 million paying subscribers in UCAN (United States and Canada), 74 million in EMEA (Europe, Middle East, and Africa), 39.9 million in LATAM (Latin America), and 32.6 million in APAC (Asia Pacific) ( Netflix Annual Report 2021 , pp. 21–22). Subscription estimates from data analytics companies indicate Netflix is a niche service (subscribed to by fewer than a quarter of households) in most countries. But it is arguably a mass market product in Australia, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada where roughly half of homes subscribe. 4

On the one hand, Netflix is a single entity. Much about it is consistent across its transnational reach. On the other hand, Netflix is varied in ways that many do not realize. For example, Wayne (2020) identifies localization of the user interface in Israel with both Hebrew language and right to left orientation of the interface—a localization strategy common in many markets, and Netflix has offered a lower priced mobile-only subscription in some markets, particularly in India to addresses two characteristics of that context: (a) that Netflix’s standard price is high relative to market norms and (b) that video consumption in India predominantly occurs on mobile devices ( Ramachandran, 2019 ). But another significant way it varies is by offering different libraries of content in different countries.

The analysis here focuses on 17 different Netflix national libraries. These 17 include many of the countries estimated to have the most subscribers and account for the experience of roughly 80% of Netflix subscribers globally. The focus was also demarcated based on a limited piece of viewing data in which Netflix released lists of the 10 most-viewed titles during 2019 in these 17 different countries. 5 The library data was collected in February 2021 unless otherwise noted. 6

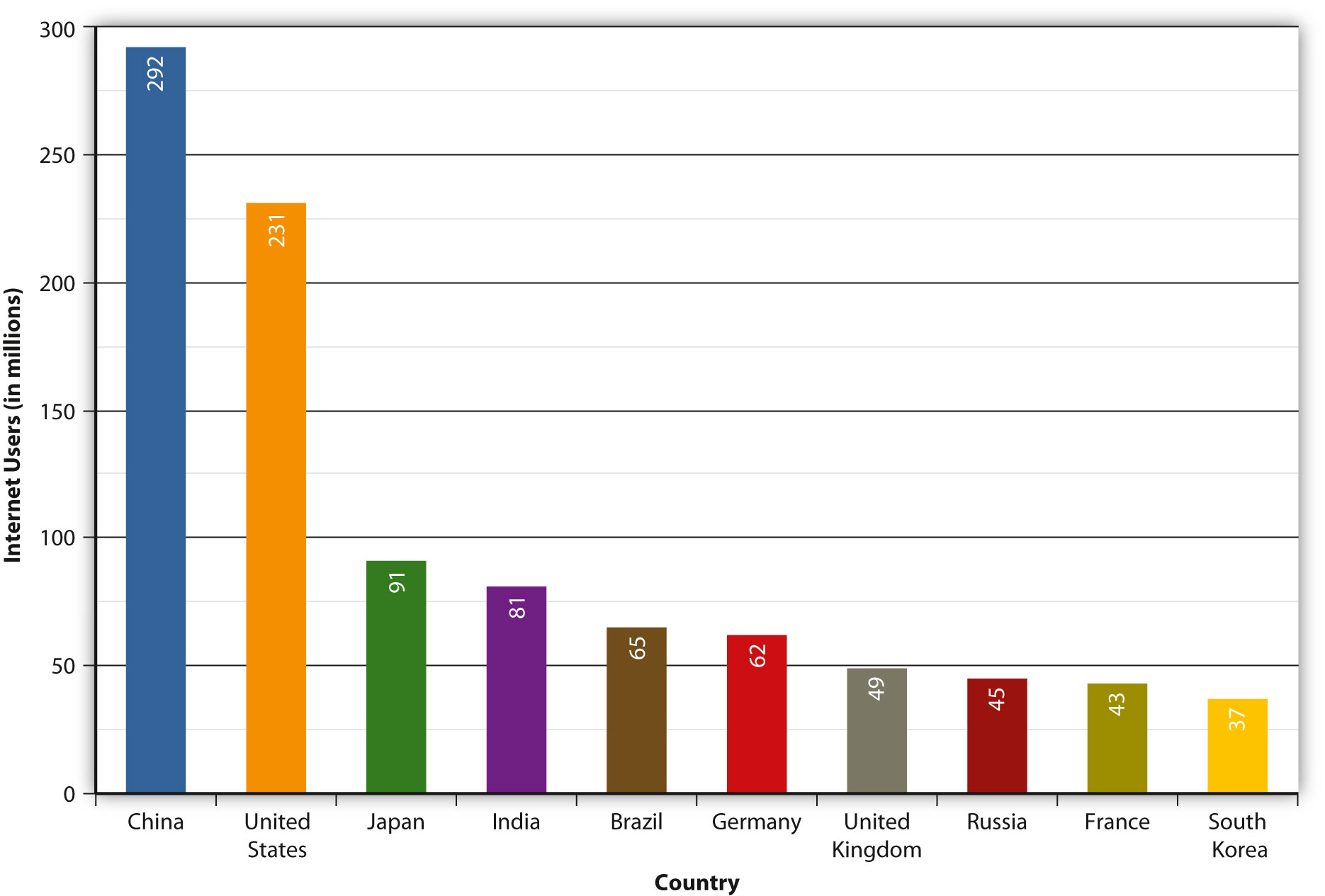

Figure 1 shows the total number of titles in each of the 17 libraries in 2021 as well as the 2016 title count for the 13 libraries that existed at that time. By 2021, the 17 libraries are relatively similar in size, though there were larger differences five years earlier. 7 Note also that despite the similarity in library size, there are differences in the composition of libraries—a topic we consider in more detail below.

Number of titles in Netflix libraries over time: 2016 and 2021.

Country of origin

Given the dominant role of Hollywood in producing video content found throughout the world, we examined the proportion of U.S.-produced content in the different libraries. Figure 2 illustrates that U.S. produced content does not account for the majority of titles in any of the libraries, including the United States’ library, and ranges from 36% to 44% of titles in each library. This is a notable finding. Our analysis of other global streamers’ libraries shows a much greater emphasis on U.S. content: Amazon Prime Video 48%, HBOMax 74%, AppleTV+ 91%, and Disney+ 92%. 8 Not only does Netflix operate with a strategy that is not dominated by U.S. productions across its many libraries, it also offers a smaller proportion of U.S. content than other global U.S.-based streamers.

Percentage of national library produced in United States.

Netflix libraries are not overwhelming composed of American titles, but they are also not particularly local. Rather, individual libraries contain an average of 7.7% domestic titles across the 17 libraries (and this falls to 3.8% if the three outlier libraries discussed below are excluded). The Netflix United States and Netflix Japan libraries have uncommonly high levels of domestically produced titles—39% and 24%, respectively—followed by South Korea (14%), India (13%), and the UK (8%). But domestic content accounts for just a small percentage of titles in Taiwan, Italy, and Colombia, which is more typical of the service. 9 (Looking outside our sample, is it also the case in most countries.) Percentage of domestic titles is a somewhat difficult indicator to make sense of because streamers’ offering of a library is so different than the schedules linear services have offered; and there is not consistent and comprehensive data about this aspect of linear services. We can nevertheless put these results into what may be a more meaningful context. On average, 3.8% of a library amounts to roughly 200 titles. This is not an insignificant number, though it likely is more meaningful when compared to other streamers in a specific market (see Lobato and Scarlata, 2019 ). To be certain, sorting productions by country of origin is a limited point of analysis. It does not tell us if a title is at all culturally ‘of’ the place it is produced. In other analyses we have found some Netflix commissions to be significantly grounded with cultural specificity (place-based), yet more often they rely only on banal signifiers that locate the setting without cultural detail (placed), and in other cases produce stories devoid of cultural or geographic indicators (placeless) ( Lotz and Potter, 2022 ; see chapters in Lotz and Lobato, 2023 ). Systematic textual analysis is needed to investigate the extent to which domestic titles indicate cultural specificity but cannot be validly performed with a corpus of titles as expansive as a national library.

Another way to assess national origin of the libraries is to evaluate the countries that are the source of the titles in the 17 countries’ libraries. Table 1 presents the top ten countries that source the 17 libraries and the average percentage of titles they account for. Only eight of the 17 countries that are part of the library analysis rank among top ten sources; titles from China, a country in which Netflix does not offer service, account for just over 2% of titles, while Egypt is just under 2%. Both China and Egypt produce content for substantial audiences, China in terms of population and Egypt as a major production hub in its region. Note also that the countries that provide the most titles in Table 1 are not those generally perceived as dominant in past trade. 10 Steemers (2004) cites data produced in 2001 indicating the United States accounted for 75% of the value produced by exporting television, the UK 10%, and Australia and France 1.2% each, leaving 12% accrued by the rest of the world. This is not a perfect comparison to the library titles, but it is indicative of the dynamics of the linear era and how strongly the U.S. dominated trade.

Source country of titles in Netflix library, based on average composition of 17 national Netflix libraries

In sum, Netflix libraries aren’t overwhelmingly composed of only U.S.-produced titles. The U.S. accounts for more content than other countries—typically around 40% of titles—but the remaining 60% is sourced from 80 different countries; this is very different from other U.S.-based services (Disney+; Apple TV+). Even so, Netflix offers significant domestic content in only a few countries (United States, Japan, South Korea, India, and UK).

Library composition

To investigate more deeply the extent to which there is cross-national variation in the titles included in Netflix libraries we queried the percentage of titles held in common in the 16 non-U.S. libraries relative to those in the U.S. library. As Figure 3 indicates, there is significant commonality. Roughly 60–80% of the titles in non-U.S. libraries also appear in the U.S. library. But what about the 20–40% not common across the libraries?

Percentage of common titles in each library and US library.

To investigate the similarities across libraries in a more detailed way, we compared titles in each of the 17 libraries with the others to identify the proportion of titles held in common. Results are illustrated in Figure 4 , in which darker shades reflect higher levels of overlap. 11 The country-by-country comparison illustrates how higher levels of library commonality can be identified among three clusters: Latin America (Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico); Europe (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Sweden); and the Anglosphere (Australia, Canada, United Kingdom, United States) + India . The Asian countries do not form a comparable cluster. This results from the fact that the Asian libraries used in this study, particularly India, Japan, and South Korea, include an uncommonly high number of domestic titles specific to their libraries.

Library commonality matrix.

To better understand the dynamics of Asian libraries, we compared the libraries of all nine Asian countries included in Ampere’s dataset (India, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and five others outside our 17-country sample: Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand). This additional analysis, illustrated in Figure 5 , reveals that Japan and South Korea feature uncommonly unique libraries, as well as the distinction of the Taiwanese and Indian libraries from what appears to be the “core” Asian cluster. Also notable, in terms of comparing this extended Asian sample with the 17-country matrix in Figure 4 , is the distinction of the core Asian cluster from the Indian library, which shows higher levels of commonality with libraries in the Anglosphere.

Asian library commonality matrix.

A contrast among these three uncommon libraries is that Japanese domestic content is largely exclusive to that country, as is South Korea’s, while the Indian content is more regularly included in other countries’ libraries. Indeed, India ranks second as the source country of most countries’ libraries (as explored in Table 1 ). This explains the greater commonality between the Indian library and other countries’ libraries observed in Figure 4 . It also raises another notable phenomenon, that of the variable extent to which Netflix commissions titles in different countries.

Commissioned titles

Another point of library comparison that shows strong commonality is the balance of “commissioned” versus licensed content. Commissioned titles are those where Netflix funds production costs, which earns it input on development; whereas licensed content is commissioned by other providers, typically television channels, or created for theatrical release. Across the 17 libraries, commissioned titles account for 28% on average. Netflix generally makes its commissioned titles available across all libraries, so variation owes primarily to differences in library size. Commissioned content ranged from 1,404 titles in the Japanese library to 1,520 titles in the Spanish library, with an average of 1,464 titles across the 17 libraries. Commissioned titles are important to analyzing the service’s role in culture because they enable the service to deploy a bespoke content strategy. Commissions are also important to a subscriber-funded service because they are typically exclusive to the service. Netflix commissions substantively more content than other “global” streaming services. (This is discussed further below; see Figure 7 .)

Figure 6 shows the number of domestic commissioned titles in each national library, titles that are commissioned by Netflix and produced in the country of that library. The number of domestic commissioned titles for the United States is far larger than elsewhere, so we use a truncated x -axis to show differences across the remaining countries. The UK, and to a lesser extent Japan, Mexico, and India have more domestic commissioned content than other countries. Commissioned, domestic titles account for 16% of the U.S. library with 911 titles; the UK ranks second at 1.4% with 86 titles. Netflix’s origin as a U.S.-only service contributes some to this imbalance; the percentage of U.S.-sourced titles has decreased as U.S. subscribers have diminished relative to the subscriber base ( Lotz, 2022 ). In February 2021, 61% of all Netflix commissions were produced in the United States (which includes earlier years when the service was more resolutely North American), yet among the commissions that debuted in 2020, only 50% were produced in the United States, illustrating the decline in U.S. production as the balance of subscribers shifted outside UCAN. Still, many of the 17 major Netflix markets have 20–40 domestic commissions, which amounts to less than 1% of their library titles.

Domestic commissioned titles in 17 Netflix libraries, February 2021.

It is important to remember that these 17 libraries are not representative of other Netflix libraries in terms of domestic commissioning: 95% of Netflix commissions are accounted for in these 17 libraries, so other libraries will include very little locally commissioned content. Although Netflix is commissioning a significant number of titles outside the United States, this number is more impressive when aggregated cross-nationally than it is at the national level.

Yet, Netflix clearly differs from other global streamers in the extent of its commissioning of titles outside the United States. Figure 7 shows the number of hours commissioned by different global streaming services. 12 It should be noted that several of the other services launched since 2019 while Netflix’s first commissioned series debuted in 2013. Commissioned content produced in the U.S. accounts for 58% of Amazon commissions, 61% of Netflix commissions, 88% of HBO Max commissions, and 96% of Disney+ commissions. 13 The scale of Netflix’s commissioning—as opposed to those offering a service based on owned intellectual property—is relevant for understanding the variation in country of origin of its library. Services such as Disney+, Paramount+, and HBO Max rely on titles produced in the United States for decades before streaming.

Comparison of total hours commissioned by major streaming services, February 2021.

A key factor in Netflix’s differentiation from other streamers, then, is the extent to which it commissions content in many countries and that it then circulates those titles across its libraries. Netflix’s commissioned titles account for roughly half of the 60% of titles common across the libraries. Netflix’s transnational “circulation” of content is uneven, but arguably more distributed than the case of broadcast or satellite channels. It is unclear whether this strategy will remain specific to Netflix or be adopted by other streaming services as their new title development expands.

The capabilities of multi-territory streaming services have reanimated legacy concerns about cultural imperialism and balance and flow in audiovisual trade. The willingness of a significant number of subscribers to pay to access Netflix—a service with predominantly foreign content and not guided by the aim of building a national audience—challenges the presumed priority on proximity that developed to explain past transnational media flow dynamics. The implications of the evidence derived from Netflix library analysis are complicated and suggest the need for new lines of research about the cultural role of video in the 21st century.

Its clearest contribution is in dismantling false presumptions of uniformity across U.S.-based, multi-territory streaming services and of Netflix as providing chiefly U.S.-produced content. Netflix may be a U.S.-based company, but at this point, its strategy in sourcing and circulating content differs significantly from services with which it is often compared such as Disney+, Amazon Prime Video, Apple TV+, and HBO Max. Library analysis reveals the scale of its consistency in offering a multi-nationally sourced video service and yet caution is warranted in presuming too much commonality across its national libraries. Claims about “Netflix” must also account for the particularity evident in its operation in Japan, South Korea, and India and in terms of geographic and linguistic clusters, for instance.

There is thus a need for caution in assuming that theory developed for linear, ad-supported services is a reliable starting point for investigating streamers and that the stories the streamers offer have a consistent cultural role across the nations in which they are available. Part of developing the necessarily nuanced understanding of Netflix and its cultural role is recognizing the limits of talking about it as serving 190 countries when it is a most-niche service in most of them. This is important for scholarship that seeks to make claims of its reach, consistency, and influence.

One of the most difficult aspects of theorizing the role of video in culture in the 21st century is the degree to which a multiplicity of niche tastes guides commercial strategies and the extent to which theories built for explaining services driven to create mass audience norms have not engaged with implications of niche video conditions. The ability to build a service by attracting even some subscribers across a base of 190 countries is an endeavor very different from seeking a mass audience within a nation. We mustn’t assume these services aim to be mass services (available in the majority of homes) in every country, as this allows us to be alert to new flows and strategies that emerge and then consider their implications relative to the operation of culture and power. The infrastructure of these services enables greater flexibility than earlier distribution technologies; that flexibility will affect adoption patterns, cultural functions, and likely introduce unexpected “patterns of video flow”. Library analysis can offer us a starting point for understanding, but most theory building requires a broader array of contextualized evidence.

Relatedly, the understanding we develop of the cultural role of these services needs to begin from a specific context. For individuals, “Netflix” only derives its meaning and value relative to other options in their market such as the features of legacy services and the extent to which domestic and other streamers are available. For instance, in order to explain the presence of a library cluster of the “Anglosphere and India” we must begin by appreciating the specificity of India’s context. The cluster may seem surprising, aside from roots in British colonialism, but this is likely a function of Netflix targeting a particular sector of the Indian population and the fact the country has more English speakers than any country but the United States. Even though it offers a discounted, mobile-only pricing plan in India, its library strategy suggests a priority on a cosmopolitan niche that complements the dominant Indian-based streaming services in the market such as ALTBalaji and Eros Now that have libraries of mostly Indian productions.

To consider context in another case, the high take up of Netflix in Australia should not be casually explained by cultural and linguistic proximity alone. Rather, it likely owes as much to Australia’s lack of a competitively priced cable or satellite service. The Australian company Foxtel has held a monopoly on multichannel service and achieved a household penetration rate of only around 25% of Australian households as of 2019, compared to 51% pay-TV-household penetration in the UK ( Ofcom, 2019 , 5), 65% in the United States (down from 90%, Spangler, 2020 ), or 70% in Canada ( CRTC, 2020 ). 14 Streaming was aggressively adopted in Australia because the market lacked the quality of options in comparable countries. Macro-level analysis, as offered in the library analyses above, can establish parameters and trends, but it is necessary to also investigate specific places and account for their particular contextual dynamics as we begin to theorize the cultural implications of streaming services. Theories may need to be tuned to particular configurations of linguistic, economic, technological, and regulatory dimensions rather than be aimed at explaining the cultural role of streaming globally.

Similarly, rather than use the library evidence to presume greater preference for cultural proximity among the Japanese or South Korean markets, we must investigate underlying contextual dynamics. Pertierra and Turner (2012) note that historically 90% of Japanese television content was produced in Japan—a much higher domestic level than typical in much of the world outside of major exporters such as the United States and UK. Netflix's comparatively bespoke approach to the Netflix Japan library may reflect awareness of this.

It is notable that the comparison of libraries illustrated in Figure 6 corresponds to Lotz’s (2021a) hypothesis regarding Netflix operating “consistently” across North and South America, Europe, and Australia and in contrast to the “variable” markets of India, Japan, and South Korea. That analysis was based on very limited viewing data released by Netflix: the ten most-watched titles across the 17 countries assessed here for all of 2019; it identified that India, Japan, and South Korea ranked the lowest in viewing of U.S. produced titles and had the highest level of domestic titles in the most viewed content after the United States. If there is causation in this relationship, it is impossible to know the underlying cause. Netflix may have identified different viewing patterns in these countries and developed library strategies accordingly, or the difference in viewing may be “caused” by the emphasis on domestic content in these libraries. The 2019 viewing data is a very small bit of insight, but given the paucity of available viewing data, it is worth noting that patterns in viewing data are consistent with the more extensive and systematic library analysis developed here.

This article provides an evidence-based frame for building theories about how global streaming services both perpetuate and contrast from expectations of global video services developed for previous technologies and to illustrate the atypicality of Netflix. Constructing such a broad view prevents the article from the specific investigations needed that will cumulatively bring into relief both nationally particular and transnational dimensions of these services. The detailed insight only possible through examination of specific national contexts is crucial to theorizing the cultural implications of these services, implications likely to vary considerably on the basis of pre-existing services, the extent to which global services take bespoke approaches, and the extent of local services and non-U.S., multi-territory services that emerge. Although subscriber-funded, Internet-distributed video services have reconfigured storytelling norms in some ways, they also expand the tyranny of the pursuit of economies of scale that drives media industries and leads to inequitable circulation and commissioning. Implications of the distinctive transnational strategy of a service like Netflix will thus differ among large and small countries, however, we should remain open to considering how the affordances of on-demand libraries and recommendation may make content developed in small nations more accessible and discoverable than under analog norms.

Investigating questions about viewing behavior to refine notions such as proximity requires audience research that is also crucial to advancing thinking in the field. Despite the scale of data associated with digital communication technologies, it is human-level data that is most required to understand emerging cultural dynamics. As others have argued ( Turner, 2019 ), qualitative audience research is desperately needed to begin to build theory suited for the contemporary audiovisual ecosystem.

Data used in this article are proprietary but can be obtained from Ampere Analysis. Scripts used to run the analyses shown are available from the author.

Authors bio

Amanda D. Lotz is Professor in the Digital Media Research Centre at Queensland University of Technology where she leads the Transforming Media Industries research program. Her research explores how digital distribution has changed media industries, the content they make, and the implications for culture.

Oliver Eklund is a PhD candidate in the Digital Media Research Centre at Queensland University of Technology. His research focuses on media industry and policy transformations.

Stuart Soroka is Professor in the Department of Communication at the University of California, Los Angeles. His research focuses on political communication, political psychology, and mass media.

Our thanks to research team members Ramon Lobato, Stuart Cunningham, and Alexa Scarlata, members of the Global Internet Television Consortium, and Anna Potter for support and feedback on the development of this article, as well as the blind reviewers and editorial team at the Journal of Communication .

This research relies on funding from the Australian Research Council (Discovery Project DP190100978).

Ampere Analysis is a data and analytics firm specializing in the SVOD sector. Access to its database of SVOD libraries is available for an annual subscription fee; we generated reports for the services under consideration using parameters facilitated by Ampere. Ampere is used globally by regulators, industry, and researchers.

Within critical media studies, attention increasingly turned to closer examinations of specific national contexts in the late 1990s and early 2000s that uncovered particular industrial, historical, and contextual features that further explained the role of television in culture, especially as satellite television significantly challenged the national boundaries of these industries. These accounts identified storytelling ecosystems that blend domestic and imported content and provided context-based explanations for those practices, although audience research did not figure significantly in these projects (e.g., Kumar, 2010 ; Tinic, 2005 ).

Commissions (so-called Netflix “originals”) are titles that Netflix pays production costs and then functionally owns, while licensed titles, the majority of the current Netflix content, are created by production companies for theatrical distribution or for television channels. Netflix effectively “rents” these titles for a limited period, either for particular national libraries or the service in its entirety.

Analysis based multiplying subscriber estimates by 2.5 (per household composition norms of these countries) and dividing by population figures.

This is not a lot of data to work from, but the consistency of source and time make it the richest information our research team has identified to consider audience viewing relative to the library data. Netflix began releasing daily ten most-watched lists in each market in March 2020; however, these lists cannot be aggregated in any way to make the data meaningful beyond the day. Netflix has subsequently made weekly lists available, but again, only offer rank indication.

When exploring Ampere datasets for this article, we focused the main analysis on the month of February 2021 using Ampere’s ability to filter data by month and year. We filtered to explore titles as “TV Shows” and “Movies.” As such, we did not count each TV Season as a separate title, which is how the data is organized. The coding of country of origin and “commissioned” status is done by Ampere. In a small number of cases, Ampere had not yet coded the primary production country. There was no assigned production country for a few titles. The research team manually added this field for those titles.

We also looked at the data in terms of hours rather than titles. The trends were not different (a heavier or uneven use of series versus movies would cause this) and we decided titles was the most legible way to present the data.

The libraries of these services also vary by country, but much less so, excepting Amazon. Not all services are available in the same countries preventing a precise comparison. Every effort was made to achieve a representative result although our analysis of these other services is provided for context and is not as systematic as the investigation of Netflix. The Amazon Prime Video figure averages Australia, Brazil, Germany, India, South Korea, and the United States—three countries with a major Amazon retail presence and three without—because there are significant differences in the library size of countries that have a strong retail presence. Only U.S. library data was available for HBO Max. The Apple TV+ figure uses Australia, Brazil, Germany, India, and the United States. The Disney+ figure uses Australia, Brazil, Germany, and the United States.

Those familiar with European regulation of content quotas may find this surprising. It should be noted that the AVMSD was in various stages of implementation and enforcement across the EU at the time the data was collected. Many member states’ national versions of the AVMSD catalogue quotas affecting on-demand services allow for the majority of the requirement to be satisfied through ‘European works’. As such, individual European countries can still record low amounts of domestic content. AVMSD definitions count a title as European if it is produced in signatory countries to the European Convention on Transfrontier Television . Signatories to that convention include the UK, allowing UK content to count as European post-Brexit.

No comprehensive data of global television trade exists publicly, so this assertion is based on discourse rather than empirical data.

The commonality matrix shown in Figure 4 is like a correlation matrix, but the raw material is slightly different. For any given dyad, we take the average of (a) the proportion of titles in library x that also appear in library y , and (b) the proportion of titles in library y that also appear in library x . The resulting value captures the proportion of the two libraries that is shared; and those proportions are illustrated in Figure 4 such that darker shades reflect higher levels of overlap. (See the legend to the right of the graphic.) Countries are then arranged in Figure 4 based on their commonality scores.

Data in Figure 7 also come from Ampere and are based on the hours of commissioned movies and series seasons found in the U.S. library of these services. Except for Paramount+, the measurement is for Feb. 2021. Paramount+ is for the month of March 2021 due to data availability.

Titles only counted once complete and available.

Australia data is based on calculations from Foxtel subscriber data and ABS household data for 2019. The UK figure is Ofcom’s number of pay-TV households in 2019, then divided by total UK households (14.3 million/27.8 million). Pay-TV household penetration in 2019 in Canada is CRTC (2020) information in their supplemental excel files they offer from the Communications Monitoring Report. U.S. figure of 65% is derived from Spangler (2020 ).

Chalaby J. ( 2005 ). Transnational television worldwide . Tauris .

Google Scholar

Google Preview

CRTC . ( 2020 ). Communications Monitoring Report. https://crtc.gc.ca/eng/publications/reports/PolicyMonitoring/2020/cmrd.htm .

Cunningham S. , Craig D. ( 2019 ). Social media entertainment . New York University Press .

de Sola Pool I. ( 1979 ). Direct broadcast satellites and the integrity of national cultures. In Nordenstreng K. , Schiller H. (Eds.), National sovereignty and international communication (pp. 120 – 153 ). Ablex .

Esser A. ( 2016 ). Defining “the local” in localization or “adapting for whom?” In Smith I. R. , Bernal-Merino M. Á. (Eds.), Media across borders: Localising TV, film and video games (pp. 19 – 35 ). Routledge .

Fiske J. ( 1987 ). Television culture . Methuen .

Gitlin T. ( 1979 ). Prime time ideology: The hegemonic process in television entertainment . Social Problems , 26 ( 3 ), 251 – 266 . https://doi.org/10.2307/800451

Golding P. , Harris P. ( 1997 ). Beyond cultural imperialism . Sage .

Gray A. ( 1992 ). Video playtime: The gendering of a leisure technology . Routledge .

Havens T. ( 2006 ). Global television marketplace . British Film Inst .

Havens T. ( 2014 ). Towards a structuration theory of media intermediaries. In Making media work (pp. 39 – 62 ). New York University Press .

Hoskins C. , Mirus R. ( 1988 ). Reasons for the US dominance of the international trade in television programmes . Media, Culture & Society , 10 ( 4 ), 499 – 515 . https://doi.org/10.1177/016344388010004006

Kumar S. ( 2010 ). Gandhi meets primetime: Globalization and nationalism in Indian television . University of Illinois Press .

Lobato R. ( 2019 ). Netflix nations: The geography of digital distribution . NYU Press .

Lobato R. , Scarlata A. ( 2019 ). Australian content in SVOD catalogs: Availability and discoverability. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2019-10/apo- nid264821.pdf.

Lotz A. D. ( 2007 ). If it is not TV, what is it? The case of U.S. subscription television. In Banet-Weiser S. , Chris C. , Freitas A. , (Eds.) Cable Visions: Television Beyond Broadcasting (pp. 85 – 102 ). New York University Press .

Lotz A. D. ( 2017 ). Portals: A Treatise on Internet-Distributed Television . Maize Publishing .

Lotz A. D. ( 2021a ). In between the global and the local: Mapping the geographies of Netflix as a multinational service . International Journal of Cultural Studies , 24 ( 2 ), 195 – 215 . https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877920953166

Lotz A. D. ( 2021b ). Unpopularity and cultural power in the age of Netflix: New questions for cultural studies’ approaches to television texts . European Journal of Cultural Studies , 24 ( 4 ), 887 – 900 . https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549421994578

Lotz A. D. ( 2022 ). Netflix and streaming video: The business of subscriber-funded video on demand . Polity .

Lotz A. D. , Potter A. ( 2022 ). Effective cultural policy in the 21 st century: Challenges and strategies from Australian television . International Journal of Cultural Policy , 1 . https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2021.2022652

Lotz A. D. , Lobato R. (Eds.) ( 2023 ). Streaming stories: Subscription video and storytelling across borders . New York : New York University Press .

Moran A. ( 2009 ). Reasserting the national? Programme formats, international television and domestic culture. In Turner G. , Tay J. (Eds.), Television studies after TV , (pp. 159 – 168 ). Routledge .

Morley D. ( 1986 ). Family television: Cultural power and domestic leisure . Routledge .

Morley D. , Robbins K. ( 1995 ). Spaces of identity: Global media, electronic landscapes and cultural boundaries . Routledge .

Newcomb H. M. , Hirsch P. M. ( 1983 ). Television as a cultural forum: Implications for research . Quarterly Review of Film & Video , 8 ( 3 ), 45 – 55 .

Netflix Annual Report . 2021 ; https://s22.q4cdn.com/959853165/files/doc_financials/2021/q4/da27d24b-9358-4b5c-a424-6da061d91836.pdf

Ofcom . ( 2019 ). Media Nations: UK 2019 . Ofcom .

Pertierra A. C. , Turner G. ( 2012 ). Locating television: Zones of consumption . Routledge .

Ramachandran N. ( 2019 ). Netflix tries out mobile-only subscription plan in India. Variety , March 22. https://variety.com/2019/digital/news/netflix-tries-mobile-only-subscription-plan-in-india-1203169961/ .

Schiller H. ( 1969 ). Mass communication and American empire . Westview .

Spangler T. ( 2020 ). Traditional pay-TV operators lost record 6 million subscribers in 2019 as cord-cutting picks up speed. Variety , 19 Feb.; https://variety.com/2020/biz/news/cable-satellite-tv-2019-cord-cutting-6-million-1203507695/

Steemers J. ( 2004 ). Selling television: British television in the global marketplace . British Film Institute .

Steemers J. ( 2016 ). International sales of UK television content: Change and continuity in “the space in between” production and consumption . Television & New Media , 17 ( 8 ), 734 – 753 .

Sinclair J. , Jacka E. , Cunningham S. ( 1996 ). New patterns in global television: Peripheral vision . Oxford University Press .

Straubhaar J. D. ( 1991 ). Beyond media imperialism: Asymmetrical interdependence and cultural proximity . Critical Studies in Media Communication , 8 ( 1 ), 39 – 59 .

Straubhaar J. D. ( 2007 ). World television: From global to local . Thousand Oaks : SAGE publications .

Straubhaar J. D. , La Pastina A. ( 2007 ). Multiple proximities between television genres and audiences. In World television: From global to local . SAGE publications .

Straubhaar J. D. , Santillana M. , Joyce V. D. M. H. , Duarte L. G. ( 2021 ). From telenovelas to Netflix: Transnational, transverse television in Latin America . Palgrave Macmillan .

Thussu D. K. (Ed.) ( 2006 ). Mapping media flow and contra-flow. In Media on the move: Global flow and contra-flow (pp. 10 – 29 ). Routledge .

Tinic S. ( 2005 ). On location . University of Toronto Press .

Tomlinson J. ( 1991 ). Cultural imperialism: A critical introduction . Plinter .

Tunstall J. ( 1977 ). The media are American: Anglo-American media in the world . Constable .

Turner G. ( 2019 ). Approaching the cultures of use: Netflix, disruption and the audience . Critical Studies in Television: The International Journal of Television Studies , 14 ( 2 ), 222 – 232 .

Waisbord S. ( 2004 ). McTV: Understanding the global popularity of television formats . Television & New Media , 5 ( 4 ), 359 – 383 .

Wayne M. L. ( 2020 ). Global streaming platforms and national pay-television markets: A case study of Netflix and multi-channel providers in Israel . The Communication Review , 23 ( 1 ), 29 – 45 .

Wood H. ( 2009 ). Talking with television: Women, talk shows, and modern self-reflexivity . University of Illinois Press .

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1460-2466

- Print ISSN 0021-9916

- Copyright © 2024 International Communication Association

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Globalization, Development and the Mass Media

- Colin Sparks - Hong Kong Baptist University, HK

- Description

It examines two main currents of thought. The first: the ways in which the media can be used to effect change and development. It traces the evolution of thinking from attempts to spread 'modernity' by way of using the media through to alternative perspectives based on encouraging participation in development communication.

The second: the elaboration of the theory of media imperialism, the criticisms that it provoked and its replacement as the dominant theory of international communication by globalization.

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

Preview this book

Sample materials & chapters.

Introduction PDF

Select a Purchasing Option

This title is also available on SAGE Knowledge , the ultimate social sciences online library. If your library doesn’t have access, ask your librarian to start a trial .

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section History of Global Media

Introduction, navigating the field: resources and journals.

- General Overviews

- The Telegraph and Global Communications, 19th to Mid-20th Centuries

- News in the Age of Colonial Empires, 1850s to 1950s

- Media in the Colonial and Postcolonial World I: Asia and the Middle East

- Media in the Colonial and Postcolonial World II: Africa

- Media Histories of Latin America

- Media and the Cold War

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Cable Television

- Communication History

- Cultural Imperialism Theories

- Political Economy

- Radio Studies

- Telecommunications History/Policy

- Visual Communication

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Culture Shock and Communication

- LGBTQ+ Family Communication

- Queerbaiting

- Find more forthcoming titles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

History of Global Media by Sönke Kunkel LAST REVIEWED: 26 February 2020 LAST MODIFIED: 26 February 2020 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756841-0243

Inspired by the “global turn” in the humanities and social sciences, the history of global media has developed into a burgeoning interdisciplinary field in recent years and now integrates a wide spectrum of diverse approaches and disciplines, ranging from media and communication studies over political science to history. This article reviews particularly the newer historical scholarship which has seen a major rise of output in recent years and has added much new empirical insight to the field. The focus is especially on works covering the 19th and 20th centuries and it concentrates first on newer works on global telegraphy and news agencies as well as on broader overviews. The second part of this article then maps works on the classic mass media in Africa, Asia, and Latin America: print, radio, and television, with a few glimpses toward cinema. It concludes with a section on the Cold War. Global media history means three things in the context of this article: (1) the history of media as global connectors and forces of globalization that enabled and promoted transnational flows of news, texts, pictures, information, ideas, and lifestyles; (2) the history of mass media in regions beyond the United States and Europe; and (3) the history of the ways in which governments and other historical actors used media to promote cross-national and international connections, messages, and interactions. The underlying understanding here, then, is that writing global media history involves as much a specific perspective on entanglements and interconnections as it is a programmatic effort to decenter existing European and US-centered national historiographies and enrich those with Latin American, African, and Asian experiences. The first studies on global media already appeared in the 1960s and 1970s. Mostly written by social scientists and communication scholars under contract by governments or UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization), those works mapped the contemporary media environments of African, Asian, and Latin American countries, but usually also touched on historical developments. Common themes of those works were the media policies of the postcolonial state and the charge of cultural imperialism. Genuinely historical works on global mass media only began appearing from the mid-1980s on and initially focused on the interrelationships between diplomacy and global communications. Since the 2000s the historical study of global media has gradually broadened, and now overlaps considerably with other fields such as imperial history, business history, the history of public diplomacy and propaganda, and even ocean studies, making it a highly dynamic and fast-growing field.

Global media history has many outlets these days, and much recent work is published in journals that do not necessarily specialize in media history, including the Journal of Global History , History and Technology , or journals with a more regional focus. Readers looking for newer works that go beyond the scope of this bibliography may therefore find it most productive to go through academic databases first, many of which have indexed and made searchable journal articles across the disciplines of history and communication studies. There are also a number of specialized journals for media historians, however, and those increasingly treat global perspectives. Among those, The Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television is one of the oldest, followed by Media History which has been published since the 1990s. Journalism Studies , too, often includes historical pieces. Many media historians are organized in the International Association for Media and History whose blog often features book reviews and news about recent developments in the field, and thus is another useful resource for a first contact with global media history.

The Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television . 1980–.

The leading journal on the international and global history of media. Published four times a year, the journal features research articles and a very extensive book review section. Though an emphasis is often on transatlantic media, journal issues usually also feature items of interest for global media historians. Most recommended as a resource.

History and Technology . 1983–.

The focus of this journal is the history of technology, defined in a broad sense. Issues often cover essays on media technologies and mass communications, ranging from the telegraph to the telephone. There is a certain predominance of research articles on technologies in the Western world, but the non-Western world gets a fair share of treatment as well.

International Association for Media and History

The most important professional association for media historians, bringing them together with practitioners under one roof. The Association organizes an international conference every two years, runs a blog, and offers masterclasses for postdoctoral researchers and postgraduate students on a regular basis.

Journalism Studies . 2000–.

Featuring up to twelve or more issues a year, this journal is devoted to the study of journalism in all of its aspects and dimensions. Focus is mostly on current issues, but the journal also often features historical pieces. Includes only research articles, no book reviews.

Journal of Global History . 2006–.

The flagship journal for global historians. Publishes research on global history, though media history has not yet drawn much attention within its pages. Still, every now and then issues do include contributions on media history, making the journal a useful starting point for scholars interested in global media history.

Media History . 1993–.

Formerly known as Studies in Newspaper and Periodical History , this interdisciplinary journal covers the broad sweep of media history from the 1500s to today, though the focus is mostly on the 19th and 20th centuries. Often publishes special issues on topics of interest. Also includes a short book review section. One of the leading journals in the field.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Communication »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Accounting Communication

- Acculturation Processes and Communication

- Action Assembly Theory

- Action-Implicative Discourse Analysis

- Activist Media

- Adherence and Communication

- Adolescence and the Media

- Advertisements, Televised Political

- Advertising

- Advertising, Children and

- Advertising, International

- Advocacy Journalism

- Agenda Setting

- Annenberg, Walter H.

- Apologies and Accounts

- Applied Communication Research Methods

- Argumentation

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) Advertising

- Attitude-Behavior Consistency

- Audience Fragmentation

- Audience Studies

- Authoritarian Societies, Journalism in

- Bakhtin, Mikhail

- Bandwagon Effect

- Baudrillard, Jean

- Blockchain and Communication

- Bourdieu, Pierre

- Brand Equity

- British and Irish Magazine, History of the

- Broadcasting, Public Service

- Capture, Media

- Castells, Manuel

- Celebrity and Public Persona

- Civil Rights Movement and the Media, The

- Co-Cultural Theory and Communication

- Codes and Cultural Discourse Analysis

- Cognitive Dissonance

- Collective Memory, Communication and

- Comedic News

- Communication Apprehension

- Communication Campaigns

- Communication, Definitions and Concepts of

- Communication Law

- Communication Management

- Communication Networks

- Communication, Philosophy of

- Community Attachment

- Community Journalism

- Community Structure Approach

- Computational Journalism

- Computer-Mediated Communication

- Content Analysis

- Corporate Social Responsibility and Communication

- Crisis Communication

- Critical and Cultural Studies

- Critical Race Theory and Communication

- Cross-tools and Cross-media Effects

- Cultivation

- Cultural and Creative Industries

- Cultural Mapping

- Cultural Persuadables

- Cultural Pluralism and Communication

- Cyberpolitics

- Death, Dying, and Communication

- Debates, Televised

- Deliberation

- Developmental Communication

- Diffusion of Innovations

- Digital Divide

- Digital Gender Diversity

- Digital Intimacies

- Digital Literacy

- Diplomacy, Public

- Distributed Work, Comunication and

- Documentary and Communication

- E-democracy/E-participation

- E-Government

- Elaboration Likelihood Model

- Electronic Word-of-Mouth (eWOM)

- Embedded Coverage

- Entertainment

- Entertainment-Education

- Environmental Communication

- Ethnic Media

- Ethnography of Communication

- Experiments

- Families, Multicultural

- Family Communication

- Federal Communications Commission

- Feminist and Queer Game Studies

- Feminist Data Studies

- Feminist Journalism

- Feminist Theory

- Focus Groups

- Food Studies and Communication

- Freedom of the Press

- Friendships, Intercultural

- Gatekeeping

- Gender and the Media

- Global Englishes

- Global Media, History of

- Global Media Organizations

- Glocalization

- Goffman, Erving

- Habermas, Jürgen

- Habituation and Communication

- Health Communication

- Hermeneutic Communication Studies

- Homelessness and Communication

- Hook-Up and Dating Apps

- Hostile Media Effect

- Identification with Media Characters

- Identity, Cultural

- Image Repair Theory

- Implicit Measurement

- Impression Management

- Infographics

- Information and Communication Technology for Development

- Information Management

- Information Overload

- Information Processing

- Infotainment

- Innis, Harold

- Instructional Communication

- Integrated Marketing Communications

- Interactivity

- Intercultural Capital

- Intercultural Communication

- Intercultural Communication, Tourism and

- Intercultural Communication, Worldview in

- Intercultural Competence

- Intercultural Conflict Mediation

- Intercultural Dialogue

- Intercultural New Media

- Intergenerational Communication

- Intergroup Communication

- International Communications

- Interpersonal Communication

- Interpersonal LGBTQ Communication

- Interpretation/Reception

- Interpretive Communities

- Journalism, Accuracy in

- Journalism, Alternative

- Journalism and Trauma

- Journalism, Citizen

- Journalism, Citizen, History of

- Journalism Ethics

- Journalism, Interpretive

- Journalism, Peace

- Journalism, Tabloid

- Journalists, Violence against

- Knowledge Gap

- Lazarsfeld, Paul

- Leadership and Communication

- Mass Communication

- McLuhan, Marshall

- Media Activism

- Media Aesthetics

- Media and Time

- Media Convergence

- Media Credibility

- Media Dependency

- Media Ecology

- Media Economics

- Media Economics, Theories of

- Media, Educational

- Media Effects

- Media Ethics

- Media Events

- Media Exposure Measurement

- Media, Gays and Lesbians in the

- Media Literacy

- Media Logic

- Media Management

- Media Policy and Governance

- Media Regulation

- Media, Social

- Media Sociology

- Media Systems Theory

- Merton, Robert K.

- Message Characteristics and Persuasion

- Mobile Communication Studies

- Multimodal Discourse Analysis, Approaches to

- Multinational Organizations, Communication and Culture in

- Murdoch, Rupert

- Narrative Engagement

- Narrative Persuasion

- Net Neutrality

- News Framing

- News Media Coverage of Women

- NGOs, Communication and

- Online Campaigning

- Open Access