A rare insight into the Quaid’s early education

During his five years at the school, Jinnah left and rejoined the institution twice

COMMENTS (1)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ

PTI hails judiciary after victory in reserved seats case

PTI eligible for reserved seats, ECP's allocation to ruling coalition unconstitutional: SC

Lahore faces urban flooding, streets turn into rivers after torrential rain

1720771163-0/photo-collage-png-(1)1720771163-0-270x192.webp)

Qasim Akram replaces Hunain Shah for Pakistan A's Australia tour after injury

PBC also challenges surveillance order

Pakistan, Azerbaijan eye $2 billion trade

Boost your brain: 13 exercises to keep your brain fit

IMF proposes 45% tax on agriculture income

'We know how to form and topple govts,' Zardari warns PML-N

Finance minister calls for overhaul of military pensions

SC full court stalls on reserved seats

SBP to remain closed on July 16-17 for Ashura

Can we stop the rot?

Learning from history

Terrorism threatening transboundary watercourses

Doha-III and the IEA

Indian agenda: terror ties, military alliances and Hindutva expansion

A diminished India

- Entertainment News

- Life & Style

- Prayer Timing Pakistan

- Weather Forecast Pakistan

- Karachi Weather

- Lahore Weather

- Islamabad Weather

- Online Advertising

- Subscribe to the Paper

- Style Guide

- Privacy Policy

- Code of ethics

This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, redistributed or derived from. Unless otherwise stated, all content is copyrighted © 2024 The Express Tribune.

- Latest News

- Entertainment

- Money Matters

- Writer's Archive

- Oped Opinion Newspost Editorial

- Magazines Instep Money Matters YOU US TNS

Quaid’s message for directionless youth

—The writer teaches at Iqra University, Islamabad Campus. She is a freelancer, blog and content writer and social activist. She can be reached at: [email protected]

Court issue a notice to the attorney general and advocate general Islamabad and indicated to hear the case on a daily...

CCP team also provided an overview of the Act with a particular focus on the significance of packaging and labelling...

CM Sarfraz Bugti briefs President Zardari on the overall situation of the province and the ongoing development projects

Several people including women were injured in police action and several leaders of Baloch Yekjehti Committee and...

Court directed IGP to ensure posting of newly recruited law graduate police officers in police stations and...

They argue it would promote smoking habits among children in African countries

- Sci & Tech

Quaid-e-Azam’s Vision for Pakistan: An Islamic or Liberal State?

Published on

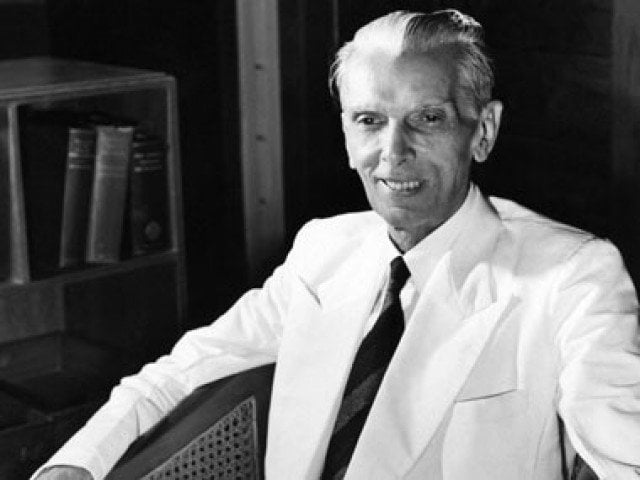

The founder of Pakistan, Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah, is a revered figure in the country’s history, known for his tireless efforts to secure a separate homeland for Muslims in the Indian subcontinent. However, a contentious debate persists regarding whether Quaid-e-Azam envisioned Pakistan as an Islamic state or a liberal one. This article will explore the nuances of Jinnah’s vision and the complexities of the Islamic versus liberal state debate.

One perspective suggests that Quaid-e-Azam aimed to establish Pakistan as an Islamic state, rooted in the principles of Islamic law or Sharia. Jinnah’s speeches and statements often emphasized the importance of Islamic values in the new nation. He spoke of justice, equality, and the welfare of the people, all of which are consistent with Islamic principles.

Jinnah’s efforts to secure the rights of Muslims in a majority-Hindu India also highlight his commitment to the protection of religious minorities, a fundamental Islamic principle. Additionally, the Objectives Resolution of 1949, which was passed after Jinnah’s death, laid the foundation for Pakistan as an Islamic state, committing to the promotion of Islamic values.

On the other hand, there are arguments suggesting that Quaid-e-Azam envisioned Pakistan as a liberal state, characterized by principles of democracy, rule of law, and individual freedoms. Jinnah’s famous speech on August 11, 1947, to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan, emphasized the importance of religious freedom and the separation of religion from the state’s affairs. He said, “You may belong to any religion or caste or creed – that has nothing to do with the business of the state.”

Furthermore, Pakistan’s initial constitution in 1956 did not declare it an Islamic state. It was only later, during General Zia-ul-Haq’s regime in the late 1970s, that amendments were made to the constitution, explicitly labeling Pakistan as an Islamic Republic.

It is crucial to understand that Quaid-e-Azam’s vision for Pakistan was multifaceted and evolved over time. His primary objective was to secure a separate homeland for Muslims where they could freely practice their religion and live as equal citizens. While Islamic values were important to him, Jinnah also recognized the diversity within Pakistan and the need to protect the rights of all citizens, regardless of their religious beliefs.

The question of whether Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah aimed to establish Pakistan as an Islamic or liberal state is complex and has sparked ongoing debates. His vision was shaped by the historical context and the challenges he faced during the partition of India. Ultimately, Jinnah’s primary goal was to create a nation where Muslims could exercise their rights and live in harmony, and whether Pakistan is an Islamic state or a liberal one continues to be a matter of interpretation and debate.

The writer can be reached at: [email protected]

- vision of Quaid-e-Azam

Latest articles

Umt confers sohail warraich with ‘prof of practice’ title, umt awards degrees to 1795 graduates at 26th convocation, lahoris purchase 400,000 new vehicles annually , traffic problems in lahore.

- Advertisements

- Events / Competitions

Launched in 2005, The Educationist is a Lahore, ُPakistan-based English/Urdu newspaper reporting on the education related news and issues from around the world, especially Pakistan and Asia. The newspaper is available in Hard print form as well in English and Urdu websites.

© 2022 Educationist . All Rights Reserved. Developed by with Clicktraces .

In order to continue enjoying our site, we ask that you confirm your identity as a human. Thank you very much for your cooperation.

- Business Recorder

- Supplements

Quaid’s vision of education

- Dec 25th, 2010

- Comments Off on Quaid’s vision of education

- Middle East

- Eastern Europe

- Southeast Asia

- Central Asia

- International Law

- New Social Compact

- Green Planet

- Urban Development

- African Renaissance

- Video & Podcasts

- Science & Technology

- Intelligence

- Energy News

- Environment

- Health & Wellness

- Arts & Culture

- Travel & Leisure

- Hotels & Resorts

- Publications

- Advisory Board

- Write for Us

- Internships

Creation of Pakistan is, doubtless, a miracle. Despite the lapse of over 70 years, India still has to reconcile with Pakistan as a reality. When Jinnah left India on August 7, 1947, Vallabhai Patel said, ‘The poison had been removed from the body of India’. But the Quaid said, ‘The past has been buried and let us start afresh as two independent sovereign States’. The 1916 Lucknow Pact was acknowledged as a pillar of Hindu-Muslim friendship. However, Motilal Nehru, at the behest of the fanatic Hindus, shattered the spirit of peaceful coexistence by formulating his Nehru Report (1928). His son Jawaharlal, outwardly liberal, regarded the creation of Pakistan as a blunder. His rancour against Pakistan reached a crescendo in his remark ‘I shall not have that carbuncle on my back’ (D. H. Bhutani, The Future of Pakistan , page 14).. Jaswant Singh, in his book, Jinnah: India, Partition, and Independence reveal that Jinnah shelved the idea of independent Pakistan by putting his signature to the Cabinet Mission’s recommendations. This Mission envisaged keeping India undivided for ten years. The constituent assemblies were to consider the question of division after 10 years. When Congress refused to accept the recommendations of the Cabinet Mission, the British government decided to divide India.

Quaid’s dream of a peaceful Sub-Continent and Indo-Pak joint defence

Akbar Ahmed, in his paper Why Jinnah matters(`Maleeha Lodhi (ed.), Pakistan Beyond the Crisis State , Chapter 2, pages 21-34) says, ‘Just before his own death, Jinnah proposed a joint defence pact with India as the Cold War started to shape the world and the two power blocs began to form. Jinnah was still thinking as a South Asian nationalist. Since he had won the rights and security of his community through the creation of Pakistan, he thought the problem of national defence was over….Had Jinnah’s vision prevailed_ and found an echo in India it would have seen a very different South Asia. There would have been two stable nations India and Pakistan, both supplementing and supporting each other. Indeed Jinnah’s idea of a joint defence system against the outside world would have ensured that there would have been no crippling defence expenditures. There would have been no reason to join one or other camp of the Cold War. There would have been open borders, free trade and regular visiting between the two countries’.

The Quaid keenly desired that the subcontinent and all of South Asia should remain aloof from the rivalry. Therefore, he proposed a joint defence pact with India. Had India accepted his idea, the two countries would not have been at daggers drawn after independence.

Before his final flight (Aug 7, 1947) from Delhi to Pakistan, he sent a message to the Indian government, “the past must be buried and let us start as two independent sovereign states of Hindustan and Pakistan, I wish Hindustan prosperity and peace.” Vallabhbhai Patel replied from Delhi “the poison has been removed from the body of India. As for the Muslims, they have their roots, their sacred places and their centres here. I do not know what they can possibly do in Pakistan. It will not be long before they return to us.”

Nehru’s followers continued their anti-Pakistan tirade in the post-Partition period. Fanatic Hindus in Indian National Congress thought that Pakistan would, at best, be a still-born baby. But, Pakistan was able to survive all hurdles. It proved its viability despite severe politico-economic jolts. A few words about the Quaid’s vision are in order.

The Quaid’s vision

A democracy, not a theocracy

Doubtless, the Quaid visualised Pakistan to be a democracy, not a theocracy. In a broadcast addressed to the people of the USA (February 1948), he said, ‘In any case Pakistan is not going to be a theocratic State to be ruled by priests [mullahs] with a divine mission. We have many non-Muslims, Hindus, Christians, and Parsees– but they are all Pakistanis. They will enjoy the same rights and privileges as any other citizen and will play their rightful part in the affairs of Pakistan’

Plain Mr. Jinnah, not Maulana Jinnah

When an over-ebullient admirer addressed him as `Maulana Jinnah’, he snubbed him. Jinnah retorted, ‘I am not a Maulana, just plain Mr. Jinnah’. About minorities, the Quaid often reminded Muslim zealots ‘Our own history and our and our Prophet (PBUH) have given the clearest proof that non-Muslims have been treated not only justly and fairly but generously.

Protector General of minorities

He added, ‘I am going to constitute myself the Protector-general of the Hindu minority in Pakistan’. Till his last breath, the Quaid remained an ardent supporter of rights of minorities as equal citizens of Pakistan. Our official dignitaries shun rituals and customs of minorities. But, the Quaid participated in Christmas celebrations in December 1947 as a guest of the Christian community. He declared: ‘I am going to constitute myself the Protector General of Hindu minority in Pakistan’.

One member of his post-Partition cabinet was a Hindu. A Jewish scholar, Mohammad Asad, who embraced Islam, held important positions in the post-Partition period in Pakistan.

The following extracts from the Quaid’s speeches and statements as Governor General of Pakistan epitomise his vision: “You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques, or to any other place of worship in this state of Pakistan…you may belong to any religion, caste or creed that has nothing to do with the business of the State…We are starting in the days when there is no discrimination, no distinction between one community and another, no discrimination between one caste or creed or another. We are starting with this fundamental principle that we are all citizens and equal citizens of the one State”.

The Quaid visualised that `in course of time Hindus would cease to be Hindus and Muslims would cease to be Muslims, not in the religious sense, because that is the personal faith of each individual, but in the political sense as citizens of the State”. A. K. Brohi, in his The Fundamental Law of Pakistan , argues that Pakistan is an Islamic state, but not a theocracy. Jinnah’s address to the Constituent Assembly on August 11, 1947, also, epitomises his vision.

He hoped India and Pakistan would live in peace after Partition. In his Will and Testament

He bequeathed a part of his fortune to educational institutions in Aligarh, Bombay and Delhi. He never changed his will as he hoped to visit India again.

Lord Ismay, Chief of Staff to the Viceroy, recorded an interview with the Quaid. Excerpt: ‘Mr. Jinnah said with the greatest earnestness that once Partition has been decided upon, everyone would know exactly all troubles would cease, and they would live happily ever after where they were’.

Concluding remarks

Stanley Wolpert paid tributes to the Quaid in following words, “Few individual significantly alter the course of history. Few still modify the map of the world. Hardly anyone could be credited with creating a nation State. Muhammad All Jinnah did all three”. Pakistan overcame insurmountable problems of influx of 1947 refugees, skimpy finances and myriad other problems to emerge as a viable entity. We welcomed refugees, while India is all set to drive out 4.7 million refugees from its eastern state of Assam.

IPCC’s Next Assessment Needs to Tackle the Complexities of Catastrophic Risk

New dynamics of regional security: the potential of the us–japan–south korea defense pact, winds of change: iran’s new reformist president and the path ahead, partnership to alliance: convergence in shared isolation between north korea and russia, russia and india: leaders of multipolar world.

- Cookie Policy (EU)

MD does not stand behind any specific agenda, narrative, or school of thought. We aim to expose all ideas, thinkers, and arguments to the light and see what remains valid and sound.

- Fine Living

© 2023 moderndiplomacy.eu. All Rights Reserved.

Pakistan National Hero: Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah

The founder of Pakistan, Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah, is the Pakistan National Hero who played a significant role in the independence movement of Pakistan. He was a visionary leader who fought for the rights of Muslims in the subcontinent and eventually succeeded in creating a separate homeland for them. In this article, we will discuss the life, achievements, and legacy of Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

Pakistan’s history is incomplete without mentioning the name of Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah. He was a lawyer, politician, and statesman who dedicated his entire life to the cause of Pakistan’s independence. Born in Karachi on December 25, 1876, Jinnah was the eldest child of his parents. He received his early education in Karachi and went to England to study law.

Table of Contents

Early Life and Education of the Pakistan National Hero

Jinnah was a brilliant student and excelled in his studies. After completing his education, he started his legal practice in Bombay and soon became a prominent lawyer. He was a man of principles and never compromised on his beliefs. He was deeply influenced by the teachings of Sir Syed Ahmed Khan and Allama Iqbal, who were prominent Muslim leaders of the time.

Political Career of the Pakistan National Hero

Jinnah’s political career started when he joined the Indian National Congress in 1906. He believed that the Indian National Congress was the best platform to fight for the rights of Muslims in the subcontinent. However, he soon realized that the Congress was dominated by Hindus and that the interests of Muslims were not being protected. He, therefore, resigned from the Congress in 1920 and joined the All India Muslim League, which was formed to protect the rights of Muslims.

Struggle for Pakistan

Jinnah’s struggle for Pakistan started in the 1930s when he demanded a separate homeland for Muslims in the subcontinent. He believed that Hindus and Muslims could not live together in a united India and that the only solution to the Hindu-Muslim problem was the creation of a separate homeland for Muslims. He worked tirelessly to convince Muslims of the need for a separate homeland and finally succeeded in achieving his goal in 1947 when Pakistan was created.

Achievements of the Pakistan National Hero

Jinnah’s achievements are numerous. He was the architect of Pakistan and played a crucial role in the creation of the country. He was also the first Governor-General of Pakistan and worked tirelessly to establish the country’s political, economic, and social institutions. He was a strong advocate of democracy, human rights, and equality and believed that these were the foundation stones of a progressive and prosperous society.

Legacy of the Pakistan National Hero

Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s legacy is immense. He is considered to be one of the greatest leaders of the 20th century and an inspiration to millions of people around the world. His vision, determination, and leadership continue to inspire generations of Pakistanis to this day. His legacy is a reminder of the sacrifices and struggles of the people who fought for Pakistan’s independence and the need to uphold the principles of democracy, human rights, and equality.

- Who was Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah?

Answer: Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah was the founder of Pakistan and a national hero who fought for the rights of Muslims in the subcontinent.

- What were Jinnah’s achievements?

Answer: Jinnah’s achievements are numerous. He was the architect of Pakistan and played a crucial role in the country’s creation. He was also the first Governor-General of Pakistan and worked tirelessly to establish the country’s political, economic, and social institutions.

- What was Jinnah’s political career?

Answer: Jinnah’s political career started when he joined the Indian National Congress in 1906. He later resigned from the Congress and joined the All India Muslim League, which was formed to protect the rights of Muslims.

- What was Jinnah’s vision for Pakistan?

Answer: Jinnah’s vision for Pakistan was to create a separate homeland for Muslims in the subcontinent. He believed that Hindus and Muslims could not live together in a united India and that the only solution to the Hindu-Muslim problem was the creation of a separate homeland for Muslims.

- What is Jinnah’s legacy?

Answer: Jinnah’s legacy is immense. He is considered to be one of the greatest leaders of the 20th century and an inspiration to millions of people around the world. His vision, determination, and leadership continue to inspire generations of Pakistanis to this day.

Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah is a national hero and a symbol of hope and inspiration for millions of Pakistanis. His vision, determination, and leadership continue to inspire people around the world, and his legacy is a reminder of the sacrifices and struggles of those who fought for Pakistan’s independence. We should strive to uphold his principles of democracy, human rights, and equality and work towards a more prosperous and progressive Pakistan.

- “Muhammad Ali Jinnah” by Encyclopedia Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Muhammad-Ali-Jinnah

- “Muhammad Ali Jinnah” by History.com: https://www.history.com/topics/india/muhammad-ali-jinnah

- “Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah – Father of the Nation” by Government of Pakistan: https://www.pakistan.gov.pk/Quaid-e-Azam-Muhammad-Ali-Jinnah-Profile

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

e Book sheir.org

Quaid-e-azam and two nation theory.

Jinnah was a visionary who rightly exploited the situation at Lahore Resolution to give the Two Nation Theory a concrete outlook. He brought the Indian problem out of the shackles of communalism into its internationalized character seeing a situation when during the world war two years, India was seeking attention of the US President Roosevelt as well.

“The problem in India is not of inter-communal nature, but manifestly of an international one, and it must be treated as such.” Jinnah’s presidential address to the annual session of All India Muslim League in March 1940.

Two Nation Theory & Lahore Resolution Two Nation Theory was an evolutionary theory in the history of the Sub-Continent. It clearly stated that the Hindus and the Muslims are two different nations who cannot be merged into one another in political, religious or even socio-cultural way.

Two Nation Theory sought a formal recognition in the address of Jinnah in 1940. Before calling the Indian issue as an international one, he took time to explain the material and spiritual differences between the two nations. This was a signal by the Muslim League that from now on only Two Nation Theory would be the guiding principle of the struggle of the Muslims. Lahore Resolution of 1940 is important also because it was a platform where the practical manifestation of the Two Nation Theory was presented by Fazal ul Haq who described the geographical division feasible under this theory.

Indian Problem as an International One Jinnah repudiated that Indian problem was mere a communal one. He called it international problem because;

- Both Hindus and the Muslims fulfilled all the criteria to be called as two nations

- Indian problem was not communal because it was now gaining attention of the world community

- It was impossible to take this matter a communal one and let it unsolved without interference of any foreign hand

Conclusion Two Nation Theory was a concrete reality. Jinnah inculcated this theory effectively on the eve of All India Muslim League session of 1940. Internationalization of the Indian problem was in real meaning the manifestation of the Two Nation Theory.

- Career Assessment

- Recognized Universities

- Merit Calculators

- Scholarships

- Entry Tests

- Past Papers

FBISE Rules for Improvement of Subjects for Matric 2024

The much-awaited result of Federal Board Matriculation examination is now public. Results do not bring the same emotions to every student. Those who are successful in achieving the desired marks are happy with the conduct of the examination. On the other hand, students who are unable to score good marks feel depressed and dejected with such results.

There is always light at the end of tunnel and with a positive approach, one can find solutions to a problem. Likewise, students who unfortunately fail in the exam or score less marks can sit in the supplementary examination. It gives them a chance to improve their grades.

Should I improve my matric subjects?

It is a wise decision to look at all factors before applying for the supplementary exams. All this challenging work must translate in the results as increased marks. Therefore, one should only put serious efforts for the supplementary exams if there is gap of more than twenty marks. Moreover, knowing the reason for failure or decreased marks can only help in getting better results. Some students during the preparatory phase, face severe health issues which affects their preparation for the exam badly. Supplementary exams are a practical choice to increase the marks as there will be ample time to prepare the exam. Likewise, students often pay less attention to Urdu, Islamiat and Pak studies which cost them badly in the overall score. So, if you have enough margin to score good marks in a particular subject, you must improve.

How to apply for improvement of subjects for matric?

There are two pathways available for the students after matric, if they are interested in applying for improvement through a supplementary exam.

Regular students at Educational Institutes:

Regular students who are attached to an educational institute can process their application form by paying educational fess through Institutional Head. After the submission of fees, the application forms can be sent to board office with the attached documents required for processing the application.

Ex or Private Students:

Students who have passed the SSC-I OR SSC-II can improve their marks by applying individually (Ex or Private) by sending documents to board office. The application should be on the prescribed admission form and attested by a gazetted officer of BS-17 of Education department/ Armed forces. Students who improve their results will be treated as Ex students and not regular students. Students must send the fee along the application form to ensure their admission in supplementary exam.

Important guidelines for students applying for 2nd Annual exam:

- Admission forms must be dispatched well before the last date, at least three days before the last date to apply for the supplementary examination of the federal board.

- No late fee will be charged for those students whose result is declared after the prescribed date. They must send the application form to the federal board within 15 days of the declaration of results and before the start of examination.

- Students should send the complete fee as notified by the Federal board. If the fee is less, they must send the remaining fee to become eligible for the supplementary examination.

- Students must secure their registration card as no admission form will be accepted without the registration number.

- Fee from the foreign national students studying in institution affiliated with the federal board will be charges according to the rates for the oversees Pakistani.

- Admission form and Examination fee must be sent up to ten working days before the start of supplementary examination. In this case, penalty for every day will be charged, after the deadline of quadruple fee schedule. As a last resort, admission forms of the students (hardship cases) will only be considered after applying on the prescribed late admission form with the requisite fees.

How many subjects can I improve in matric in Federal board?

You can improve as many subjects as you want from part I or part II of SSC or both within a period of one year of passing the examination. If you are appearing in a subject with a practical examination, you must attend the practical examination too. Both the theory and practical exam will be evaluated separately as new cases.

How many times can you apply for improvement in the Federal Board?

If you have passed the SSC-II examination, you will be given multiple number of chances to improve the marks as an Ex-Candidate in the required course if he/she avails the chance in next four years of passing without getting higher education than this level of studies.

What if you missed a chance for improvement, applied but not appeared?

If you applied for improvement but due to any reasons, you could not participate in the exam. You can still avail the chance of improvement. This next chance must be in the four-year limit after passing the SSC-II exam.

Does a student need to send old result card to get the improved result card?

No, as per rule 1.13 clause b of the Federal Board examination rules, if you improve grades or marks in a supplementary examination, you will be issued a new result card showing the improved result without surrendering the old one.

Supplementary exams are conducted with a gap of 40 days after the announcement of results. As the matric results are announced in the mid of July this year, Supplementary Exams can be held in September 2024. For latest information, keep visiting our website www.eduvision.edu.pk

Explore Other Options

- General News

- School Management

- Job Hunting

- Examinations

Related News

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

Elektrostal

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

Elektrostal , city, Moscow oblast (province), western Russia . It lies 36 miles (58 km) east of Moscow city. The name, meaning “electric steel,” derives from the high-quality-steel industry established there soon after the October Revolution in 1917. During World War II , parts of the heavy-machine-building industry were relocated there from Ukraine, and Elektrostal is now a centre for the production of metallurgical equipment. Pop. (2006 est.) 146,189.

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Eastern Europe

- Moscow Oblast

Elektrostal

Elektrostal Localisation : Country Russia , Oblast Moscow Oblast . Available Information : Geographical coordinates , Population, Area, Altitude, Weather and Hotel . Nearby cities and villages : Noginsk , Pavlovsky Posad and Staraya Kupavna .

Information

Find all the information of Elektrostal or click on the section of your choice in the left menu.

- Update data

| Country | |

|---|---|

| Oblast |

Elektrostal Demography

Information on the people and the population of Elektrostal.

| Elektrostal Population | 157,409 inhabitants |

|---|---|

| Elektrostal Population Density | 3,179.3 /km² (8,234.4 /sq mi) |

Elektrostal Geography

Geographic Information regarding City of Elektrostal .

| Elektrostal Geographical coordinates | Latitude: , Longitude: 55° 48′ 0″ North, 38° 27′ 0″ East |

|---|---|

| Elektrostal Area | 4,951 hectares 49.51 km² (19.12 sq mi) |

| Elektrostal Altitude | 164 m (538 ft) |

| Elektrostal Climate | Humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification: Dfb) |

Elektrostal Distance

Distance (in kilometers) between Elektrostal and the biggest cities of Russia.

Elektrostal Map

Locate simply the city of Elektrostal through the card, map and satellite image of the city.

Elektrostal Nearby cities and villages

Elektrostal Weather

Weather forecast for the next coming days and current time of Elektrostal.

Elektrostal Sunrise and sunset

Find below the times of sunrise and sunset calculated 7 days to Elektrostal.

| Day | Sunrise and sunset | Twilight | Nautical twilight | Astronomical twilight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 July | 02:53 - 11:31 - 20:08 | 01:56 - 21:06 | 01:00 - 01:00 | 01:00 - 01:00 |

| 9 July | 02:55 - 11:31 - 20:08 | 01:57 - 21:05 | 01:00 - 01:00 | 01:00 - 01:00 |

| 10 July | 02:56 - 11:31 - 20:07 | 01:59 - 21:04 | 23:45 - 23:17 | 01:00 - 01:00 |

| 11 July | 02:57 - 11:31 - 20:05 | 02:01 - 21:02 | 23:57 - 23:06 | 01:00 - 01:00 |

| 12 July | 02:59 - 11:31 - 20:04 | 02:02 - 21:01 | 00:05 - 22:58 | 01:00 - 01:00 |

| 13 July | 03:00 - 11:32 - 20:03 | 02:04 - 20:59 | 00:12 - 22:51 | 01:00 - 01:00 |

| 14 July | 03:01 - 11:32 - 20:02 | 02:06 - 20:57 | 00:18 - 22:45 | 01:00 - 01:00 |

Elektrostal Hotel

Our team has selected for you a list of hotel in Elektrostal classified by value for money. Book your hotel room at the best price.

| Located next to Noginskoye Highway in Electrostal, Apelsin Hotel offers comfortable rooms with free Wi-Fi. Free parking is available. The elegant rooms are air conditioned and feature a flat-screen satellite TV and fridge... | from | |

| Located in the green area Yamskiye Woods, 5 km from Elektrostal city centre, this hotel features a sauna and a restaurant. It offers rooms with a kitchen... | from | |

| Ekotel Bogorodsk Hotel is located in a picturesque park near Chernogolovsky Pond. It features an indoor swimming pool and a wellness centre. Free Wi-Fi and private parking are provided... | from | |

| Surrounded by 420,000 m² of parkland and overlooking Kovershi Lake, this hotel outside Moscow offers spa and fitness facilities, and a private beach area with volleyball court and loungers... | from | |

| Surrounded by green parklands, this hotel in the Moscow region features 2 restaurants, a bowling alley with bar, and several spa and fitness facilities. Moscow Ring Road is 17 km away... | from | |

Elektrostal Nearby

Below is a list of activities and point of interest in Elektrostal and its surroundings.

Elektrostal Page

| Direct link | |

|---|---|

| DB-City.com | Elektrostal /5 (2021-10-07 13:22:50) |

- Information /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#info

- Demography /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#demo

- Geography /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#geo

- Distance /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#dist1

- Map /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#map

- Nearby cities and villages /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#dist2

- Weather /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#weather

- Sunrise and sunset /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#sun

- Hotel /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#hotel

- Nearby /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#around

- Page /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#page

- Terms of Use

- Copyright © 2024 DB-City - All rights reserved

- Change Ad Consent Do not sell my data

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

As Quaid-e-Azam is the founder of Pakistan, so on that important event Quaid sends an important message to the nation that what will be the future structure of education.

Like the great leaders of the world, Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah was an ardent supporter of education. He envisioned a nation equipped with the best education available, both within the ...

The document discusses Quaid-e-Azam's vision for education in Pakistan based on his speeches and messages. It summarizes his key principles: 1) Education should develop the whole personality and teach morality, justice and civic duties. 2) Education must be tailored to the needs of the nation and economy, focusing on fields like industry, agriculture, science and technology. 3) The education ...

Regarding the basis of education Quaid-e-Azam identify and clear on different occasion that Islam is self sufficient in all regards and thus the basis of the education will be

Quaid's vision of education. Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah is perhaps the only leader of a developing country who laid emphasis, time and again, on the importance of education in the economic development and social progress of a nation. The Quaid was a clear-headed political visionary who contended, quite frankly, that a nation lagging ...

His birthday is observed as a national holiday, Quaid-e-Azam Day, in Pakistan. [217] Jinnah earned the title Quaid-e-Azam (meaning "Great Leader"). His other title is Baba-e-Qawm ( Father of the Nation ). The former title was reportedly given to Jinnah at first by Mian Ferozuddin Ahmed.

KARACHI: Historians and biographers may have discussed the life of Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah threadbare, yet there are several aspects of his multi-faceted life that have not been covered ...

Mohammed Ali Jinnah, Indian Muslim politician, who was the founder and first governor-general (1947-48) of Pakistan.

Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah had high hopes from Pakistani youth and in all his important addresses to students, he stressed upon youth's vision in life.

Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah at the Constitutional Assembly. Muhammad Ali Jinnah's 11 August Speech is a speech made by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, founding father of Pakistan and known as Quaid-e-Azam (Great Leader) to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan. While Pakistan was created as a result of what could be described as Indian Muslim ...

He is known there as 'Quaid-I Azam' or 'Great Leader'. Mohammed Ali Jinnah was born on 25 December 1876 in Karachi, now in Pakistan, but then part of British-controlled India. His father was a ...

Muhammad Ali Jinnah (26 December 1876 - 11 September 1948) was the founder of the country of Pakistan. After the independence of Pakistan, he became the Governor-General of Pakistan. As a mark of respect, Pakistanis call him Quaid-e-Azam. [2] Quaid-e-Azam is a phrase which, in the Urdu language, means "the great leader". He is also called Baba-e-Qaum, another phrase in the Urdu language ...

The founder of Pakistan, Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah, is a revered figure in the country's history, known for his tireless efforts to secure a separate homeland for Muslims in the Indian subcontinent. However, a contentious debate persists regarding whether Quaid-e-Azam envisioned Pakistan as an Islamic state or a liberal one. This article will explore the […]

Muhammad Ali Jinnah, often referred to as Quaid-e-Azam (Great Leader), was born on December 25, 1876, in Karachi, then part of British India. Coming from a prosperous and well-educated family ...

Quaid e Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah believed that education was a matter of life and death for Pakistan because each generation must be prepared for the pace with which the world changes.

Quaid's vision of education News Desk Dec 25th, 2010 Comments Off Due to the forward looking and transformational leadership provided by the Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah and earlier backed by the thinker of Pakistan, Allama Muhammad Iqbal and the massive struggle launched by the Muslims of the then-British sub-continent, Pakistan emerged as a sovereign independent state on the political ...

The Quaid-e-Azam's vision of Pakistan. Creation of Pakistan is, doubtless, a miracle. Despite the lapse of over 70 years, India still has to reconcile with Pakistan as a reality. When Jinnah left India on August 7, 1947, Vallabhai Patel said, 'The poison had been removed from the body of India'. But the Quaid said, 'The past has been ...

Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah is a national hero and a symbol of hope and inspiration for millions of Pakistanis. His vision, determination, and leadership continue to inspire people around the world, and his legacy is a reminder of the sacrifices and struggles of those who fought for Pakistan's independence.

Quaid-e-Azam and Two Nation Theory Jinnah was a visionary who rightly exploited the situation at Lahore Resolution to give the Two Nation Theory a concrete outlook. He brought the Indian problem out of the shackles of communalism into its internationalized character seeing a situation when during the world war two years, India was seeking attention of the US President Roosevelt as well.

Quaid-e-Azam University. University of the Punjab. University of Karachi. University of Peshawar. Lahore University of Management Sciences. ... The application should be on the prescribed admission form and attested by a gazetted officer of BS-17 of Education department/ Armed forces. Students who improve their results will be treated as Ex ...

Elektrostal metallurgical factory Elektrostal chemical-mechanical factory Elektrostal Heavy Engineering Works, JSC is a designer and manufacturer of equipment for producing seamless hot-rolled, cold-rolled and welded steel materials and metallurgical equipment. MSZ, also known as Elemash, Russia's largest producer of fuel rod assemblies for nuclear power plants, which are exported to many ...

Elektrostal, city, Moscow oblast (province), western Russia. It lies 36 miles (58 km) east of Moscow city. The name, meaning "electric steel," derives from the high-quality-steel industry established there soon after the October Revolution in 1917. During World War II, parts of the heavy-machine-building industry were relocated there from Ukraine, and Elektrostal is now a centre for the ...

Elektrostal Elektrostal Localisation : Country Russia, Oblast Moscow Oblast. Available Information : Geographical coordinates, Population, Area, Altitude, Weather and ...

Travel guide resource for your visit to Elektrostal. Discover the best of Elektrostal so you can plan your trip right.