Inequality is on the ballot

Fight poverty and injustice with advocacy

The future is equal

What is famine? Causes and effects and how to stop it

From Gaza to Sudan, people facing famine are hungry and need urgent aid to survive.

When a global report last week revealed that almost 500,000 people in Gaza are now facing starvation, it was another frightening call to action. In half of households, people reported often that they had no food to eat in the house.

"We need all hands on deck...," said the United Nations Emergency Relief Coordinator Martin Griffith. “We fail them daily every time we're not able to get aid through to the people who need it."

At Oxfam, we’ve been focused on the fight to end hunger since our founding. So, we’re going to define what exactly is famine, what causes it, share an example of a famine, and explain how people like you can help stop famine in its tracks.

What does famine mean?

According to researchers Dan Maxwell and Nisar Majid, famine is “an extreme crisis of access to adequate food.” Visible in “widespread malnutrition” and “loss of life due to starvation and infectious disease,” famine robs people of their dignity, equality, and for some—their lives.

So how do we know a famine is occurring? The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification, or IPC, is a common global scale that informs how governments and aid groups should respond when people lose reliable access to sufficient, affordable, and nutritious food. It’s a five-phase warning system to inspire urgent action before it’s too late.

For a famine to exist in a given area—Phase 5 of the acute food insecurity scale— three conditions, backed by evidence, must be met:

- 1 in 5 households faces an extreme food shortage

- More than 30 percent of children are “acutely malnourished,” a nutritional deficiency that results from inadequate energy or protein intake

- Death rates exceed two adults or four children per day for every 10,000 people

As of right now, famine has not yet been declared in Gaza. But according to the IPC , there is a “high” risk of famine across the whole Gaza Strip and about 95 percent of the population faces extreme food insecurity.

What causes a famine?

Famines are caused by multiple factors. Since 2020, a deadly combination of conflict, COVID-19, and climate change has dramatically increased the number of people suffering from severe hunger. When compounded by inaction or policy decisions that make people more vulnerable, famine can result and society can collapse.

In Gaza, many challenges are putting people on the brink of famine:

- Following the attack by Palestinian armed militants on October 7, Israel’s bombardment of Gaza has resulted in widespread damage to assets and infrastructure critical for health and food production and distribution.

- Israel’s tightening of the siege on Gaza and systematic denial of humanitarian access to and within the Gaza Strip continues to impede the safe and equitable delivery of lifesaving humanitarian assistance.

- Aid workers in Gaza are being killed and are unable to safely deliver humanitarian aid.

Political scientist Alex de Waal calls famine a political scandal, a “catastrophic breakdown in government capacity or willingness to do what [is] known to be necessary to prevent famine.” When governments fail to prevent or end conflict —or help families prevent food shortages brought on by any reason—they fail their own people.

What is an example of a famine?

The 1984 famine in Ethiopia took the lives of 1 million people , driven in part by drought, conflict, and the policy choices of national and regional authorities. Estimates suggest around 1 million people survived thanks to the delivery of humanitarian aid.

On the evening of Tuesday, October 23, 1984, NBC Nightly News aired footage taken by an Ethiopian videographer that showed scores of deceased people on stretchers that were being taken toward makeshift graveyards. Though the scenes inspired a robust international response, the nature of that response overlooked the capacity of communities affected by the famine to help themselves.

By the next morning, Oxfam America had received over 300 calls an hour from people like you who wanted to help. During the relief effort, feeding centers provided hungry people with food rations. Makeshift hospitals supported severely dehydrated people with IVs, providing shots of tetracycline to fight infection. Oxfam delivered protein and fat-fortified biscuits to those in need that saved many lives, but some could not eat them, as their mouths were riddled with open sores because of dehydration.

“These scenes of death and dying in the famine camps in Ethiopia were beyond the American experience, beyond anyone’s comprehension,” recalls Bernie Beaudreau , an Oxfam staffer at the time.

Can famine be stopped?

Famine can be stopped—now, and in the long term . But governments and aid groups must anticipate a worsening hunger crisis, secure the resources and political will to address the root causes of hunger, and safely deliver humanitarian aid to those most in need.

In Gaza and countries like Somalia, Yemen, Ethiopia, and Madagascar, Oxfam is working to reduce the likelihood of famine with people like you. Here are some ways you can support Oxfam’s work:

- Stomach ailments from dirty water rob people of good nutrition from whatever food they can find, and young children are particularly vulnerable. That’s why Oxfam helps improve and repair wells to access clean water as well as trucks in water to areas where there is none.

- Good sanitation and hygiene are essential for preventing the spread of diseases like cholera, Ebola, and COVID-19, which are especially deadly leading up to and during famines. Oxfam helps construct latrines and distributes hygiene items like soap so people can wash their hands.

- When food is available in markets, but might be scarce or very expensive for some, Oxfam distributes cash to help buy food. Oxfam also distributes emergency food rations when necessary.

- In areas where farmers can plant crops, Oxfam supplies seeds, tools, and other assistance so people can grow their own food. We also help farmers raising livestock with veterinary services, animal feed, and in some cases, we distribute animals to farmers to help restock their herds .

- We help build the capacity of local organizations to respond to emergencies like famine, shifting power from international organizations to leaders rooted in local know-how. We promote the leadership of our local partners and boost their skills to reduce suffering, risks, and losses by preparing their own communities before disasters strike.

- Oxfam and our supporters advocate for the resolution of conflicts and push for sufficient assistance for people affected by war and famine. Our research and advocacy also advance sustainable development in ways that help reduce the risk of future food crises and disasters.

Now you know what famine is

Join Oxfam to help stop famine in its tracks in Gaza right now.

Related content

Entire Gaza Strip now at “high” risk of famine

Palestinians are being starved as Oxfam continues to reach people in need and to advocate for a permanent ceasefire.

2024 Presidential Election Debate Bingo

Oxfam’s bingo card includes topics we hope are addressed by the candidates and phrases we expect will come up. Play along as you watch the debate.

Palestinians need ceasefire amid impending famine and continuing war

Oxfam and partners continue to deliver assistance for Palestinians enduring conflict, while advocating for a ceasefire, the return of all hostages, and full humanitarian access to Gaza.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Poverty and famines 2.0: the opportunities and challenges of crisis modeling and forecasting

Paul w. howe.

1 Feinstein International Center, Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, Tufts University, Boston, MA USA

2 Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, Tufts University, Boston, MA USA

Elena N. Naumova

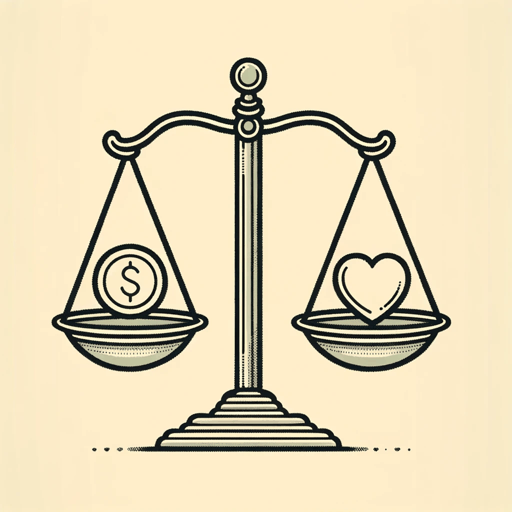

As the world works to achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 1 (SDG1): End poverty in all its forms everywhere, by 2030, it is critical to understand its strong interrelationship with two other SDGs: End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture (SDG2) and Reduce inequality within and among countrie s (SDG10). Progress in one area depends on efforts in the others, and all three goals are part of the global public health agenda. Famines, which can be understood as “acute episodes of extreme hunger that result in excess mortality due to starvation and hunger-induced diseases” [ 1 , 2 ], represent one of the most serious consequences of poverty and inequality, but they also contribute to the further immiseration and marginalization of affected populations. Recognizing these interrelationships has helped transform our approach to famine in the past and could provide a starting point for exploring new advances for the future.

In his landmark 1981 book, Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation [ 3 ], future Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen proposed a revolutionary shift in our understanding of these crises. He argued that famines often occur not from a lack of availability of food, but from the inability of certain populations to access it. While this insight suggested that poverty was a principal reason that people experience famines, Sen pressed for a more nuanced understanding of why certain groups are more at risk of starvation than others during a crisis. He suggested that it was an inability to ‘command’ adequate food because of a failure of entitlements that led to mortality. His entitlements approach laid the foundation for decades of research that have extended, contested, and moved beyond his views by, for example, emphasizing the importance of the processes that lead to famines [ 4 , 5 ], highlighting the critical role of politics and power in their causation and differential impacts [ 6 ], and addressing the global dimensions of the crises [ 7 ].

Although in the early 2000s trends suggested that these crises were diminishing in number and scale [ 2 , 8 ], famines have killed hundreds of thousands [ 9 ] of people in the first two decades of the twenty-first century and left a legacy of livelihood damage, emotional trauma, physical impairment, and social disruption. In 2021 and 2022, there have been concerns about the risk of famine in Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan, and Yemen [ 10 ]. As of November 2021, it was estimated that more than 45 million people in 43 countries were experiencing emergency food security conditions [ 11 ]. With the looming threats of climate change, continued conflict, and emerging pandemics, the world is likely to continue to face the risk of famine in the years to come, making it critical to understand with greater certainty when and where famines will occur, and which populations will be at greatest risk, and thereby help to trigger appropriate early action [ 12 ].

Just as the risk of famine appears to be increasing again globally, three trends—related to famine theory, measuring and modeling, and humanitarian practice—are converging to offer an opportunity for a step-change in our ability to understand and forecast these crises. While the focus in the discussion will be on ‘famine,’ the trends (and the proposed initiative) apply to food and nutrition security crises more generally.

First, drawing on previous literature, academics have recently suggested that famines can be understood as complex systems and have identified conceptual models that describe their evolution from formation to collapse [ 13 ]. This systems approach to famine offers new possibilities for understanding the dynamics of these crises and could help in defining driving forces, characteristic milestones, and well-tailored metrics, which would facilitate the translation of these concepts into quantitative and analytical models and produce famine forecasts.

Second, there have been rapid developments in the fields of primary data collection and computational, mathematical, and statistical modeling. Real-time data collection capabilities, through electronic devices and crowdsourcing, have accelerated and changed the possibilities for gathering information. Innovations in predictive analytics make it possible to handle the large volume of complex data required to model and forecast famines [ 14 ]. At the same time, a suite of different types of models—systems dynamics, agent-based models, stochastic models, and regression time series models—offer a wide range of approaches to challenging problems and have gained in sophistication, accuracy, and applications. These developments have enabled progress on critical problems as complex as climate change and the COVID-19 global pandemic. They offer hope for meaningful advances to deepen our understanding of famines as systems and develop robust conceptual and forecasting models.

Third, in terms of global reach and innovation, humanitarian practice has evolved in ways that could both drive these efforts forward and translate them into significant, real-world impact. Early warning analysts have continued to improve systems for predicting food insecurity crises and famines through widespread monitoring that combines sophisticated data analysis with on-the-ground insight. The Integrated Phase Classification (IPC) platform, developed in 2004, offers comparable analyses of food insecurity and malnutrition situations globally and provides a widely accepted process for determining whether a famine has occurred based on an internationally agreed definition. Humanitarian agencies are transforming responses through greater use of cash, integration into social protection systems, and emphasis on early action. United Nations Security Council Resolution 2417, which requests regular updates on crises and strongly condemns the use of hunger as a weapon of war, has reinforced accountability for famine prevention. In all these ways, it is clear that humanitarian agencies have the capability to create, adopt, and apply innovations to address crises on a global scale.

The convergence of these trends could permit two important changes in our approach to famine. The first is to help researchers create models of famine as complex systems and describe their evolution from formation to collapse, as has been done for hurricanes and infectious outbreaks. Such models could help us gain new insights into questions such as: What are the components of a famine system? What are its spatial and temporal dimensions? How do the various parts of the system interact to produce critical outcomes such as malnutrition and mortality and why are certain populations especially vulnerable? Based on these insights, the second change would be for experts to better identify the signals of famine formation and therefore improve forecasts. If successful, these forecasts could help (as part of a wider set of tools) reduce uncertainty about the likely occurrence of food and nutrition security crises, contribute to timelier, more targeted, and life-saving action, help deter famine creation, and perhaps spark new fields of inquiry. The efforts to model and forecast hurricanes and infectious outbreaks suggest these kinds of benefits are possible if there is an iterative process that continually promotes learning from experience.

In moving toward a ‘Poverty and Famine 2.0 approach,’ we identify measuring, modeling, and forecasting as three essential and interrelated processes for gathering insight based on the goals and primary activities of each. Measuring aims to collect data to create information and knowledge. Modeling aims to process data, information, and knowledge to form casual paths, rules, and systems thinking, along with their uncertainties. Forecasting aims to infer future unknown situations based on data, information, knowledge, and system thinking. To describe a process of estimating future unknown situations, the terms ‘forecasting,’ ‘prediction,’ ‘projection,’ and ‘prognosis’ are often used by researchers and practitioners interchangeably. We are also making a distinction between forecasting and predictions suggesting that forecasting is an extrapolation of the past into the future, while predictions and projections are typically subjective and judgmental in nature. While both approaches are useful in considering changes that may take place in the future, ideally, forecasting is free from intuition and personal forecasters’ biases, whereas prediction is based on judgment. In short, all forecasts are predictions but not all predictions are forecasts.

Recognizing the potential of these three converging trends, especially the power of accurate relevant data and sound analytical solutions, several actors have engaged in pioneering efforts to use predictive analytics to improve food security and nutrition forecasting based on data sources, machine learning, and novel algorithms [ 14 , 15 ]. For example, the Famine Early Warnings System Network (FEWSNET) has partnered with scientists to incorporate climate models into their scenario-building [ 16 ]; the World Bank has developed sophisticated algorithms to forecast food crises globally [ 17 , 18 ]; Consortiums have used models to understand the risk of malnutrition; and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) has used economic models to analyze the benefits of investments in resilience [ 19 ]. To a large extent, however, these efforts have been fragmented. The learnings from one are not always widely shared to inform the efforts of others. They are also partial in that most do not try to model famine itselfe, focusing instead on forecasting IPC phases, food insecurity indicators, or other outcomes. Some incorporate climate science models but have not yet found ways to bring in political and social dimensions to algorithmic forecasts. Recognizing that we are in the early stages of an emerging field, the IPC and the Global Network Against Food Crises have made famine forecasting a key component of their long-term strategies.

However, we are cognizant of the daunting challenges and genuine risks associated with pursuing famine modeling and forecasting. Modeling famine is complicated by the complexities of interacting economic, social, environmental, and political systems and the challenges of characterizing human action and decision-making. The track record on forecasting social phenomena and conflict has sometimes been discouraging [ 20 , 21 ]. These efforts also require large amounts of data from some of the most challenging contexts in the world. As a result, there is a danger that the international community will expend substantial resources and time on a venture with highly uncertain results. Such an initiative may also inadvertently reinforce the notion that there is a technical solution to famine and divert attention from pressing political issues central to its prevention. Moreover, because of the complexity of the models, they may hide assumptions and biases, reduce transparency, and perpetuate inequalities, creating ethical concerns [ 14 , 15 ]. Relatedly, the emphasis on data gathering activities and modeling exercises could lead to data-driven products that are increasingly divorced from local realities, and the experiences, views, and inputs of affected populations. Finally, while these efforts may contribute to improved forecasts, they do not directly address the critical challenge of translating early warning into early action [ 12 ].

We see potential responses to these concerns. For example, the cost of investing in these efforts is substantially smaller than the resources that are required to address current crises and that could be saved through the insights accurate forecasts could provide. Moreover, modeling and forecasting should not be seen as a substitute for social and political efforts (or existing early warning systems), but rather a complementary tool. Deliberate, joined-up approaches could also help address ethical concerns, engage affected populations, make the link to early action, and deal with data issues such as the need for reliable data repositories, tools to abstract and examine data, intra-agency and intergovernmental agreements, and data-curation standards and model-sharing protocols. Considering these challenges and potential responses, we offer six principles that could guide a famine modeling and forecasting initiative in terms of both content and process.

- Focus on both modeling famine itself and forecasting its occurrence. It is difficult to forecast what is not well understood. It is also difficult to act when the forecast is poorly focused and not well explained to end users. If we have better conceptual and analytical models of the formation, evolution, and collapse of famines as complex systems, it should help our attempts to better predict their occurrence. Likewise, progress on forecasting will point to new areas to explore in understanding the dynamics of these crises.

- Integrate multiple dimensions. While we may be more advanced in the use of climate and economic data in models, it will be important to think creatively about how political and social dimensions can be better integrated. Human behavior at any stages of decision-making could alter forecasts.

- Take an inclusive approach with global scope. The initiative requires a joined-up effort that brings together the insights of affected communities, humanitarian practitioners, famine theorists, public health professionals, data holders, and modelers across the globe. Similarly, a wide range of tools employed in science and practice—from machine learning and predictive analytics to intervention strategies to participatory approaches to simulation exercises—should be utilized.

- Be realistic, learn, and invest for the long-term. The history of using models in other fields—whether climate change or hurricanes or pandemics—suggests that they can provide early warning and deeper understanding. But the process of developing and deploying sophisticated, accurate models is challenging and the immediate payoffs uncertain. Results from conceptual developments, data analysis, and modeling need to be widely disseminated and built upon in an iterative process by a broader community. Decades may be needed to achieve the initiative’s full potential.

- Address ethical and other concerns. These models and forecasts entail a number of potential ethical risks that could undermine their usefulness and inadvertently perpetuate biases and inequalities. These concerns should be articulated and addressed upfront by the wider community involved [ 12 , 14 , 15 ], perhaps through development of protocols and procedures to guide the process.

- Look beyond models and forecasts. Models and forecasts are a potential tool for better understanding famines. But they should only be viewed as a part of a wider famine and public health agenda involving theoretical insights, enhanced early warning and action approaches, improved practice, and political efforts to prevent these crises more effectively.

Forty years after the publication of Sen’s seminal work, famine studies have identified its shortcomings and evolved in new directions, but his concern about the relationship between poverty and famines remains and challenges the global community to take creative approaches to more systematically address these crises that continue to threaten the lives and well-being of humans. Given recent trends, we believe it is an opportune moment to make a step-change in our efforts by investing in a 2.0 approach to crisis modeling and forecasting––thereby also supporting the achievement of the interrelated SDGs on poverty, hunger, and inequality.

The Journal of Public Health Policy is joining Springer in seeking submissions to a new Collection on Reducing Poverty and Its Consequences, in support of the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty. This multi-journal Collection aims to synthesize and integrate social, behavioral, and public health perspectives on systemic structures bolstering poverty and inequality, poverty-reduction interventions, as well as gaps in our knowledge and future research directions. In promoting the UN Sustainable Development Goals, we see the need for proactive dialogs across multiple stakeholders, forward-looking intervention study designs, understanding of long-term consequences of hunger and poverty, as well as the need for modeling and forecasting incorporating human behaviors beyond the technical solutions. We invite readers and contributors to share your thoughts, findings, and experiences through this new multi-journal Collection.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Famine, Affluence, and Morality

- Utilitarianism: Simply Explained

Study Guide: Peter Singer's 'Famine, Affluence, and Morality'

Introduction.

Peter Singer ’s ‘ Famine, Affluence, and Morality ’ 1 is widely regarded as one of the most important and influential texts in applied ethics. This study guide explains Singer’s central argument, explores possible objections, and clarifies common misunderstandings.

The Argument

Singer argues that most of us in affluent societies are making a terrible moral mistake. When we look at distant suffering—such as results from global poverty, famine, or disease—we tend to think that helping is morally optional , or what philosophers call “ supererogatory ”. Even if we could very easily give more to effective charities to help, doing so seems “above and beyond the call of duty”. It would be generous to give more, we think, but hardly required . We assume it’s perfectly fine to spend our money on expensive clothes, travel, entertainment, or other luxuries instead. But Singer argues that this assumption is mistaken. Instead, he argues, it is seriously morally wrong to live high while others die. 2

Singer’s argument for this conclusion is straightforward, resting largely on a key moral principle that we will call Singer’s rescue principle . The argument may be summarized as follows: 3

P1. Suffering and death from lack of food, shelter, or medical care are very bad. P2. We can prevent such suffering and death by donating to effective charities (in place of consumer purchases). P3. Many of our consumer purchases are morally insignificant: we could give them up without thereby sacrificing anything morally significant. P4. The rescue principle: If it is in our power to prevent something very bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything morally significant, we ought, morally, to do it. 4 Therefore, C. We ought, morally, to donate to effective charities rather than making morally insignificant consumer purchases. 5

Note that, although Singer is a utilitarian, this argument does not rely on utilitarianism as a premise. P1 - P4 are all claims that non-utilitarians (and even non-consequentialists) could accept.

This is a really striking argument. The four premises each seem perfectly plausible. The conclusion logically follows. Yet the conclusion is radically at odds with how almost all of us live our lives. Every time we purchase something unnecessary, Singer’s argument implies that we not only could , but also should , do better. When you think about how this would apply to your own life, it could well turn out that the majority of the purchases you make in your everyday life would be considered morally wrong. Most of us could probably live significantly more frugally without sacrificing anything morally significant, and use the savings to relieve suffering or even prevent several untimely deaths. According to Singer’s argument, that is then precisely what we are morally required to do. 6 (Note that similar arguments could also apply to one’s choice of career . 7 )

Could such a radical conclusion really be true? You are probably already thinking of ways to dismiss it. But it’s not enough to simply reject the conclusion. To reject it, you must show one (or more) of the premises to be false.

Assessing the Premises

Premise 1: badness.

The first premise claims that suffering and death are very bad . That is hard to deny. Any plausible ethical theory—whether utilitarianism, deontology, virtue ethics, etc.—will agree that, all else being equal, suffering and death are bad, 8 especially suffering that is extreme, involuntary, and uncompensated.

Premise 2: Preventability

The second premise is similarly secure: We can prevent suffering and death by donating to effective charities . Some “aid skeptics” are critical of foreign aid programs. This might suggest that we just do not know whether a given charity actually does any good. Some charitable interventions, on closer examination, even turn out to be counterproductive . However, while many charities have little impact, the most effective charities do a remarkable amount of good. Fortunately, finding effective charities is easy by consulting reputable sources such as GiveWell ’s in-depth charity evaluations. Even prominent aid skeptics do not deny that GiveWell’s top-rated charities are genuinely effective . So there is no real question that well-targeted donations can be expected to prevent a lot of suffering and death. (Of course, the argument will not apply to anyone who lacks the resources to be able to make any such donations. It’s exclusively directed at those of us who do, at least sometimes, make unnecessary purchases.)

Premise 3: Insignificant Sacrifice

The third premise claims that we could give up many of our consumer purchases “without thereby sacrificing anything morally significant.” Could one reasonably deny this? One could insist that all interests are morally significant in the sense that they count for something , so you always have at least some reason to make any consumer purchase that would bring you the slightest bit of extra happiness. But of course Singer does not mean to deny this. His use of “significant” here is not meant to distinguish interests from non-interests (that count for literally zero), but rather to distinguish especially weighty or important interests from relatively trivial ones. And it cannot plausibly be denied that some of our consumer purchases are relatively trivial, or not especially important to our lives.

It’s an interesting question precisely how to distinguish significant interests from comparatively trivial ones. The two extremes seem intuitively clear enough: luxury goods like designer clothes seem fairly unimportant, while providing a good life for one’s own child is obviously of genuine importance. In intermediate cases where it’s unclear whether an interest qualifies as deeply “morally significant”, it will be similarly unclear whether Singer’s argument requires us to be willing to sacrifice that interest in order to prevent grave harm. 9 But it’s important to note that an argument can be sound and practically important even if it is sometimes unclear how to apply it.

Premise 4: Singer’s Rescue Principle

Finally, we come to Singer’s rescue principle: If it is in our power to prevent something very bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything morally significant, we ought, morally, to do it. If we are to reject the argument’s conclusion, we must reject this premise. But can you really believe that it’s morally okay to just sit back and watch something terrible happen, when you could easily (without sacrificing anything important) prevent it?

Some may claim that our only duty is to do no harm . 10 On this view, it would be wrong to steal from the global poor, and it would be generous to help them, but we have no obligation to help in any way—it’s never wrong to simply mind one’s own business. This minimal view of morality (as limited to the duty not to harm others) meshes nicely with common views about charity. But it turns out to be unacceptable when we consider a broader range of cases, as Singer brings out with his famous Drowning Child thought experiment.

The Drowning Child

Singer writes:

If I am walking past a shallow pond and see a child drowning in it, I ought to wade in and pull the child out. This will mean getting my clothes muddy, but this is insignificant, while the death of the child would presumably be a very bad thing. 11

In a case like this, when you can easily prevent something very bad (like a child’s death), it seems clear that doing so is not only morally praiseworthy, but morally required . That remains true even if saving the child comes at a cost to yourself, as long as the cost is insignificant in comparison to the value of the child’s life. Since the cost of ruining your clothes (even an expensive suit that costs several thousand dollars to replace) is insignificant compared to the child’s life, you ought to wade into the pond to save the child.

What does the minimal “do no harm” view of morality imply about the right way to act in the thought experiment? Well, it’s not your fault that the child is drowning; you did not push them in. If you were to walk by and let the child drown, you would not be causing any additional harm—they would be just as badly off if you were not there in the first place. So the minimal view implies that it would be morally fine for you to just walk by (or even sit and eat some popcorn while watching the child drown). But that strikes most people as obscenely immoral. So the minimalist’s response to Singer’s rescue principle fails.

If applied consistently, Singer’s principle has radical implications in the real world. He writes:

We are all in that situation of the person passing the shallow pond: we can all save lives of people, both children and adults, who would otherwise die, and we can do so at a very small cost to us: the cost of a new… shirt or a night out at a restaurant or concert, can mean the difference between life and death to more than one person somewhere in the world. 12

If you accept that saving the drowning child is morally required, even at the cost of ruining your expensive suit, then morality may equally require you to donate an equivalent amount of money to save a child’s life via other means. And you can save a child’s life, just by donating a few thousand dollars to GiveWell’s top charities . (Or you can save a quality-adjusted life year by donating $100 or so.) If you would not think it okay to let a child drown when you have the ability to prevent it, moral consistency requires that you likewise refuse to let children die unnecessarily from poverty or preventable disease.

Aside from helping to address objections to Singer’s rescue principle, the Drowning Child thought experiment clarifies which of our interests are sufficiently “insignificant” that we may be called to sacrifice them to prevent grave harm to others. For example, someone might initially think that wearing designer clothes is a vital part of their identity, but if pressed on whether they would sooner watch a child drown than give up this expensive lifestyle, they might change their mind. 13

Not everyone accepts Singer’s radical conclusion about our moral obligations to donate to those in need. Yet, Singer’s conclusion is difficult to avoid since the standard objections no longer seem plausible when applied to corresponding variations of the pond case. 14 For example:

(1) You may believe charitable donations are uncertain to help. Would that remove the moral requirement to donate? But suppose you are similarly uncertain about whether the child in the pond is truly drowning (maybe they are just playing a game). Even so, mere uncertainty does not justify doing nothing. So long as the chance that your actions would help is sufficiently high (relative to the costs or any associated risks from attempting aid), you may still be required to wade in and offer assistance, just in case. Similarly, uncertainty about the impacts of your donations does not justify keeping the money to yourself, as long as the expected value of your donations is sufficiently high (relative to the costs).

(2) What if other , wealthier people could give more instead? Surely, they are under an even greater moral obligation to give, since doing so is less of a sacrifice for them. But suppose that other people stand around the pond, watching the child drown but refusing to help. They ought to help, so ideally your help would not be needed. But given that they are not helping, so your help is needed, it sure seems like it would still be wrong for you to do nothing and let the child drown. Likewise, it would be wrong not to save others’ lives by donating, even if there are more affluent people who could help but refuse to do so. (The bystander effect suggests that waiting for others to help first could easily result in no-one helping at all.)

(3) What about geographical proximity as a factor? Does it make a moral difference that the drowning child is right in front of you whereas the beneficiaries of your donations are far away ? Imagine that the pond with the drowning child was actually located far away from you, say, in another country, and you could rescue the child’s life by simply pressing a button. Surely, you would be required to press the button, even if you had to pay some money to do so. What matters morally is your ability to prevent the child from dying at a low cost to yourself, so that is what you should do—regardless of how far away the child is. Many moral theories (including utilitarianism) explicitly deny that geographical proximity is inherently morally relevant . 15

(4) Or, perhaps you think it’s enough to do your “fair share”: to just give as much as would be needed if everyone else did the same (perhaps 5% of one’s income). But suppose that after saving one child from drowning, you notice three other drowning children. Two bystanders are just watching the children drown, though you are relieved that one other adult is on track to save two of the remaining three children. Would it be okay to watch the last child drown on the grounds that you have already done the “share” (saving one out of four) that would have sufficed if everyone had done likewise? Or should you step up and do the share that is required to actually save all the children given what others are—and are not—doing?

It is unfair when some do not do their share. It’s unfairly demanding on us to have to do more than our ideal share would have been. But it would be even more unfair on the child to just let them drown. Losing their life would be a far greater burden than the extra cost to us of helping more. So, while some unfairness is inevitable when some do not do their share, concern to minimize unfairness should still lead us to step up and do more when needed.

None of these responses seems successful in establishing a morally important difference between the Drowning Child thought experiment and charitable giving. But considerations of salience, repeatability, or emergency may prove more significant. We address these in the next three sections.

Although geographical distance by itself does not seem to make a moral difference, it may make a psychological difference to us by affecting the salience of the different needs at stake. The visible suffering of a child right before our eyes has a very different emotional impact than merely abstract knowledge of distant suffering. This difference in emotional impact plausibly explains why most of us would be so much more strongly motivated to save the drowning child than to relieve distant suffering by donating to charity. But what is the moral significance of this difference in psychological salience?

Plausibly, greater salience can help bring to our attention genuine reasons to act that are there regardless, but that we might otherwise mistakenly neglect. After all, it’s not as though a suffering child suddenly becomes objectively more important once they enter our visual field. But we certainly become more aware of them (and how vital it is to help them). If this is right, it seems there is just as much moral reason to help those in need who are far away; we just tend not to notice this so much, and so we (understandably) make the moral mistake of failing to do as much as is objectively warranted in order to aid them. 16

On this analysis, the difference in salience does not affect the strength of our moral reasons—it’s just as important to save a distant child as it is to save one right before our eyes. But it does make an important difference to how we should evaluate the failure to act. Intuitively, failing to save the child from drowning would be morally monstrous , whereas failing to donate does not reflect so badly on you, even if it’s a serious moral mistake. We can explain this difference in terms of one’s quality of will . One is blameworthy to the extent that one acts from malicious motivations, or acts in a way that reveals an egregious lack of concern for others. To neglect more salient suffering reveals a greater lack of altruistic concern, even holding fixed the magnitude of the suffering in each case. So it is more blameworthy. As Chappell & Yetter-Chappell put it: “A child drowning before our eyes shocks us out of complacency, activating whatever altruistic concern we may have, whereas the constant suffering of the global poor is easier to ignore, meaning that inaction does not necessarily imply [such] an egregious lack of concern.” 17

We can thus accommodate the intuition that failing to donate to effective charities is not as blameworthy as watching a child drown (since only the latter reveals an extreme lack of altruistic concern), without this providing any reason to deny that aid in either case may be equally morally important .

Repeatability

A notable difference between the two cases is that it’s very rare to come across drowning children, whereas the needs of the global poor are constant and unrelenting. The significance of this fact is that a policy of helping those nearby in need of direct rescue would not be expected to prove especially costly. But a policy of helping anyone in the world in desperate need of aid would soon take over your life. A better analogy would then seem to be a limitless line of ponds containing drowning children. And when we consider such a case, it may no longer seem so wrong to at least sometimes take a break, and thereby let a child drown. 18

Of course, to save as many lives as possible over the long term, it would likely be optimal to take strategic breaks for self-care. At a minimum, you need to eat and sleep. But you may also save more lives in the long run if you take care to avoid burnout, taking extra breaks to spend time with friends and pursue hobbies that help you to de-stress. If so, taking such strategic breaks is morally justified by Singer’s principles. (There is no virtue in being counter-productively self-sacrificial in one’s altruism.) So this is not yet a counterexample to Singer’s view.

Still, this optimal route is highly demanding since it involves significant personal sacrifice. Suppose that in order to save the most lives you had to forsake your plans to become a parent, and cut down time spent with friends and hobbies to the bare minimum required to maintain your sanity and productivity. That is a big ask, and one that involves the loss of many morally significant goods in life. If Singer’s principle required us to pursue this optimal route, it might not seem so plausible after all.

But does it require this? Unlike maximizing utilitarianism , P4 only asks us to give up things that are not morally significant. Since the above sacrifices are clearly morally significant, it seems that they would be excluded from the list of P4’s possible demands. 19

One difficulty is that it’s not immediately clear how to apply the rescue principle to cases of repeated actions. Consider: giving up any one second of life might seem trivial. But repeated enough times, you would eventually give up your entire life , which is certainly significant. This suggests that repeatedly making an insignificant sacrifice might add up to an extremely significant sacrifice. To apply the rescue principle sensibly, then, it’s not enough to ask whether the immediate sacrifice in isolation is morally significant. We must further ask whether it’s part of a pattern that, in context, adds up to a morally significant sacrifice. If interpreted in this way, Singer’s rescue principle would seem to allow broad leeway for reserving substantial time and resources to pursue the personal projects that are most important to us. 20

Still, the conclusion of Singer’s argument remains strikingly revisionary. Even if we may reserve the majority of our spare time and resources for personal projects, we are still required to do much more for others than almost any of us actually do. Even when we need not entirely give up some expensive (or time-intensive) pastime, we may be morally required to economize—if by doing so we could (perhaps over several years) save many lives without significant lifetime loss to our own well-being . Many hobbies plausibly exhibit diminishing marginal utility: the more time and money we plow into them, the less additional value we gain from further investment. In such cases, we may be able to cut our personal investment by, say, half while still retaining most of the well-being we gain from the hobby. And of course many of us also spend time and money on entirely frivolous things that, on reflection, do not significantly contribute to our lives at all. If we reflect carefully and honestly, most of us would likely find significant opportunities to do more to help others, without needing to sacrifice anything truly important. If Singer’s rescue principle is right—and it seems hard to deny—then we really ought to pursue these opportunities.

Emergencies

The last major challenge to Singer’s argument comes from the idea that special ethical norms apply in emergency cases that cannot be broadly generalized. The drowning child scenario is a paradigmatic emergency. So perhaps common sense could be restored by combining a minimal view of our everyday obligations with ambitious positive obligations to assist in cases of emergency?

The difficulty for this view is to provide it with a principled basis. Why should emergency deaths be treated as inherently more important than equally preventable deaths from ongoing causes?

Sterri and Moen propose to explain this in terms of an “informal-insurance model”. 21 Their basic idea is that emergency ethics can be understood as a mutually-beneficial agreement among all in the moral community to informally insure each other against rare, unexpected risks of grave harm. That is, we undertake to help others in emergency situations, on the understanding that they would do the same for us. Since emergencies are rare, the comfortably-off can agree to participate in such a scheme without expecting to be bled dry by all the world’s needs. And since emergency situations can befall anyone, it’s in their enlightened self-interest to do so. We are all better off informally insuring each other against disaster in this way, than if we all were left to fend for ourselves.

This line of argument faces two significant problems, common to efforts to ground ethics in enlightened self-interest. Firstly, the underlying logic of mutual benefit excludes from the moral community not just the global poor but also others (including infants, non-human animals, future generations, and the severely disabled) who are not in a position to reciprocate. But surely you still ought to rescue a drowning paraplegic, for example, even if he could not do the same for you.

The second problem is that even when the informal insurance model gets the right result (requiring that you help), it does so for the wrong reasons. It implies that you should help for the sake of playing your part in a co-operative scheme of mutual benefit , which does not seem remotely the right reason to save a child from drowning.

To see this, imagine extending the logic of the informal insurance model to a society that includes water-phobic robots who just want to collect paperclips but occasionally drop them in puddles. In order to secure the assistance of the robots in helping to free us from getting our feet caught on railroad tracks (or other non-water-related emergencies), we might reciprocate by rescuing their lost paperclips from puddles. If the informal insurance account of emergency ethics were correct, then your moral reason to save a drowning child would be of exactly the same kind as your reason to “save” a paperclip from a puddle in the imagined scenario. But this is clearly wrong. We have moral reasons to save lives and avert great harms for the sake of the affected individuals. These moral reasons are distinct from (and more important than) our reasons to participate in mutual-benefit schemes.

Singer identifies a logical tension in our ordinary moral thought. We tend not to think much about our power to prevent great suffering (and even save lives). Even when this fact is brought to our attention, we tend to assume that it’s morally okay for us not to act on it, or to do very little. Helping would be generous, we think, but not required.

However, Singer’s rescue principle seems undeniable: if we can easily prevent something very bad—that is, without giving up anything morally significant—it sure seems that we ought to do so. And the Drowning Child scenario verifies this principle: we would not think it okay to just watch a child drown when you could easily save them at no risk to yourself. Differences in salience may explain why we find it easier to ignore more distant suffering; but it would also seem to suggest that we are morally mistaken to do so.

Considering repeatability means that we need to take our overall patterns of response into account: sacrifices that are small in isolation may add up to extreme sacrifices that are more than Singer’s principle would require. But even so, there are likely to be many changes we could make to our lives in order to help others more, without overall causing any significant loss to our own well-being. If Singer is right, we are morally required to make these changes. It’s no less important than saving a child who is drowning right before our eyes.

Discussion Questions

- Many effective altruists now believe that you can do more good through pursuing a high-impact career than by donating (even generously) while working at a less impactful job. How does that affect your view of Singer’s argument? Could you be morally required to consider a career change? Should someone in a high-impact career be expected to donate to charity in addition?

- This study guide focuses on the more moderate version of Singer’s rescue principle. But he also defends a stronger version, according to which we are morally required to prevent bad things from happening whenever we can do so without sacrificing anything of comparable moral significance. How much difference do you see between these two versions of the principle? Do you think the stronger principle is correct?

- What would a scalar utilitarian think of Singer’s principles? If there is no such thing as obligation, just better and worse actions, how would that affect Singer’s argument? Would saving lives become any less important or worthwhile if it was no longer “obligatory” in addition? What do you think is added by saying that an act is (not only good but also) “obligatory”?

- Imagine that you are going to donate money to an effective charity—enough to save two lives. But along the way, you see a child drowning in a pond. There is no time to set aside the cash in your pockets: if you jump in, the money will be destroyed, so you will be unable to make the donation after all. Should you still save the drowning child? Why / why not?

- We tend to just think about the money or resources that people already have. But suppose that you could easily earn more , say by working overtime (or shifting to a more lucrative job). Might it be wrong not to earn more money (in order to then donate more)? How would you apply Singer’s principles to this case?

- Would it be wrong for you to tell them about Singer’s argument?

- If so, would that mean that Singer’s conclusion is false , and they are not obliged to donate more after all? Or could a moral claim be true even if it was not always a good idea to tell people about it?

Your professor will explain their general expectations, or what they are looking for in a good philosophy paper. You can find other helpful general guidelines online . If writing on Singer’s ‘Famine, Affluence, and Morality’ in particular, you should take care to avoid the following common pitfalls:

- Do not get hung up on empirical disputes, such as those surrounding aid skepticism. The interesting philosophical question is whether Singer’s moral principles are correct. So just suppose we are in a position where we could help others. The fundamental philosophical question here is: How much could morality, in principle, require us to give up in order to help others? Aid skepticism does not answer this question, but merely dodges it. (Further, as MacAskill emphasizes: “There are thousands of pressing problems that call out for our attention and that we could make significant inroads on with our resources.” Global health charities are far from the only way that our money could be productively used to help others.)

- Do not get distracted by the sociological question of whether we could hope to convince most of society to act on Singer’s recommendations. The question is what we, as individuals, ought to do . It’s not about what we can convince others of. That would, again, be to dodge the fundamental moral question.

- Although Singer is a utilitarian, his argument in this paper does not rely on utilitarianism as a premise. Look again at the premises. These are all claims that even non-utilitarians could (and arguably should) accept. Alternatively, if you think that non-utilitarians ought to reject one or more of these premises, your essay should offer an argument to this effect.

- If you are having trouble coming up with an original “take” on the argument, it can often be helpful to read published responses until you find one that you disagree with. (You might start with our suggestions for further reading, below.) You can then write about why you disagree, diagnosing where you think the other author’s argument or objection goes wrong. Or, if you disagree with Singer’s original argument, you could explain why, while also showing how you think others’ defenses of his argument (as found, for example, in this very study guide) go wrong.

Good luck! And remember to cite your sources.

How to Cite This Page

Want to learn more about utilitarianism.

Read about the theory behind utilitarianism:

Learn how to use utilitarianism to improve the world:

Resources and Further Reading

- Peter Singer (1972). Famine, Affluence, and Morality . Philosophy and Public Affairs , 1(3): 229–243.

- Peter Singer (2019). The Life You Can Save: Acting Now to End World Poverty , 2nd ed. The Life You Can Save, Bainbridge Island, WA and Sydney, available free at <www.thelifeyoucansave.org>.

- Richard Y. Chappell & Helen Yetter-Chappell (2016). Virtue and Salience . Australasian Journal of Philosophy , 94(3): 449–463.

- Andrew T. Forcehimes & Luke Semrau (2019). Beneficence: Does Agglomeration Matter? Journal of Applied Philosophy 36 (1): 17-33.

- Frances Kamm (1999). Famine Ethics: The Problem of Distance in Morality and Singer’s Ethical Theory, in Singer and His Critics , ed. Dale Jamieson, Oxford: Blackwell: 174–203.

- William MacAskill (2019). Aid Scepticism and Effective Altruism . Journal of Practical Ethics , 7(1): 49–60.

- Richard Miller (2004). Beneficence, Duty and Distance . Philosophy and Public Affairs , 32(4): 357–383.

- Theron Pummer (2023). The Rules of Rescue: Cost, Distance, and Effective Altruism . Oxford University Press.

- William Sin (2010). Trivial Sacrifices, Great Demands . Journal of Moral Philosophy 7 (1): 3-15.

- Michael Slote (2007). Famine, Affluence, and Virtue, in Working Virtue: Virtue Ethics and Contemporary Moral Problems , ed. Rebecca L. Walker and Philip J. Ivanhoe, Oxford: Clarendon Press: 279–296.

- Aksel Braanen Sterri & Ole Martin Moen (2021). The ethics of emergencies . Philosophical Studies, 178 (8): 2621–2634.

- Jordan Arthur Thomson (2021). Relief from Rescue . Philosophical Studies 179 (4): 1221-1239.

- Travis Timmerman (2015). Sometimes there is nothing wrong with letting a child drown . Analysis , 75(2): 204–212.

- Peter Unger (1996). Living High and Letting Die: Our Illusion of Innocence . Oxford University Press.

Singer, P. (1972). Famine, Affluence, and Morality . Philosophy and Public Affairs 1 (3): 229-243. ↩︎

See also Unger, P. (1996). Living High and Letting Die: Our Illusion of Innocence . Oxford University Press. ↩︎

P1 and P4 are quoted (with minor edits for clarity) from p. 231 of the text. P2, P3, and C are our own extrapolations. ↩︎

Singer advocates a stricter version of the rescue principle, where we are required to sacrifice even some genuinely morally significant things, so long as they are not comparably significant to the harms thereby prevented. We focus here on the less demanding version of the rescue principle since (as Singer notes) it’s sufficient for practical purposes, while being more difficult to reject. But the stronger version is also plausible, and is entailed by utilitarianism (while also being compatible with other moral theories). ↩︎

Note that this conclusion leaves open that there may be some third option that you ought to do that is even better than donating to effective charities. It’s just making the contrastive normative claim that, between the two specified options , you ought to donate rather than make morally insignificant consumer purchases. ↩︎

Unless, again, there is some other option that would do even more good, in which case we may be required to do that instead! ↩︎

The career-focused version of Singer’s argument might look like this (with P1 unchanged):

P2*: We can prevent suffering and death by working in an impactful job rather than spending our time on a career that does not help others.

P3*: We can work in an impactful job without significant uncompensated sacrifice.

P4*: If it is in our power to prevent something very bad from happening, without significant uncompensated sacrifice, we ought, morally, to do it.

C*: We ought, morally, to work in an impactful job rather than spend our time on a career that does not help others.

Note that P3 and P4 are worded in terms of significant uncompensated sacrifice, because one’s career choice is a major life decision that is likely to involve significant tradeoffs. If one passes up becoming an artist (say), there may be something morally significant about that loss, even if one is overall happier with an alternate career. If you receive benefits commensurate with what you sacrificed, we can say that your sacrifice was compensated and so not costly to you, all things considered. ↩︎

Someone sufficiently desperate to escape the argument might reject the first premise by claiming that overpopulation is such a problem that we should not seek to save lives after all (because lives saved add to overpopulation, thus increasing overall suffering). But there are a number of reasons why this is badly misguided. First, this claim is a myth: empirically, saving lives in poor countries does not lead to overpopulation. See: Melinda Gates (2014). Saving Lives Does Not Lead to Overpopulation . The Breakthrough Institute ; Hans Rosling. Will saving poor children lead to overpopulation? Gapminder Foundation .

Second, someone who really believed this claim would also need to advocate for shutting down hospitals, letting serial killers go free, etc. Few would be willing to consistently hold the view that there is no point to saving innocent lives. Letting people die unnecessarily seems an atrocious way to attempt to counteract overpopulation.

Third, there are obviously better alternatives, such as empowering women in ways that predictably lower birth rates. Examples of this include global family planning charities or girls’ education. See Singer, P. (1972). Famine, Affluence, and Morality . Philosophy and Public Affairs , 1(3): 229–243, p. 240.

Finally, note that it’s increasingly disputed whether we should be more concerned about overpopulation or underpopulation; and that none of these concerns touch on the importance of reducing suffering, which increases the quality rather than quantity of life. ↩︎

Though, as we’ll see below, the drowning child scenario might help to illuminate the boundaries of morality’s demands here. ↩︎

Or, even more minimally, to simply not violate anyone’s rights . Either way, philosophers call this a negative duty—a duty to not do a certain action—in contrast to positive duties to do a certain action. ↩︎

Singer, P. (1972). Famine, Affluence, and Morality . Philosophy and Public Affairs , 1(3): 229–243, p. 231. ↩︎

Singer, P. (1997). The Drowning Child and the Expanding Circle . New Internationalist . ( archive ) ↩︎

Of course, the relevant question is not the psychological one of what someone would be willing to choose, but the moral one of what choice is truly justifiable. But it’s often by thinking through such a choice from the inside that we form our moral beliefs about which choices are morally permissible. ↩︎

See also Chapter 3: Common Objections to Giving, in Singer, P. (2019). The Life You Can Save: Acting Now to End World Poverty , 2nd ed. The Life You Can Save, Bainbridge Island, WA and Sydney, available free at <www.thelifeyoucansave.org>. ↩︎

Though for a competing view, see Kamm, F.M. (1999). Famine Ethics: The Problem of Distance in Morality and Singer’s Ethical Theory, in Singer and His Critics , ed. Dale Jamieson. Oxford: Blackwell: 174–203. ↩︎

Though for a competing view, which takes normal empathetic responses to determine what is right, see Slote, M. (2007). Famine, Affluence, and Virtue, in Working Virtue: Virtue Ethics and Contemporary Moral Problems , ed. Rebecca L. Walker and Philip J. Ivanhoe, Oxford: Clarendon Press: 279–296. ↩︎

Chappell, R.Y. & Yetter-Chappell, H. (2016). Virtue and Salience . Australasian Journal of Philosophy , 94(3): 449–463, p.453. ↩︎

Timmerman, T. (2015). Sometimes there is nothing wrong with letting a child drown . Analysis , 75(2): 204–212. ↩︎

Notably, Singer’s stricter comparable sacrifice principle might require those sacrifices, if none of the personal losses were comparable in significance to the extra lives saved. Singer himself endorses the utilitarian thought that we ought (in principle) to give to the point of marginal utility , where the cost to us of giving any more would equal or outweigh the gain to others. But non-utilitarians might, of course, take a different view of what counts as being of comparable moral significance. And the weaker rescue principle (P4) that our main text focuses on is certainly less demanding. ↩︎

This interpretation brings Singer’s rescue principle much closer to Miller’s Principle of Sympathy , according to which: “One’s underlying disposition to respond to neediness as such ought to be sufficiently demanding that giving which would express greater underlying concern would impose a significant risk of worsening one’s life, if one fulfilled all further responsibilities; and it need not be any more demanding than this.”

Miller, R. (2004). Beneficence, Duty and Distance . Philosophy and Public Affairs , 32(4): 357–383, p.359. ↩︎

Sterri, A.B. & Moen, O.M. (2021). The ethics of emergencies . Philosophical Studies, 178 (8): 2621–2634. ↩︎

The future is equal

- Press releases

Famine in Somalia: causes and solutions

The UN announcement of famine in Somalia is both a wake-up call to the scale of this disaster, and a wake-up call to the solutions needed to limit death-from-hunger now and in the future. So, what is famine and how can we prevent it? Famine is the “triple failure” of (1) food production, (2) people’s ability to access food and, finally and most crucially (3) in the political response by governments and international donors. Crop failure and poverty leave people vulnerable to starvation – but famine only occurs with political failure. In Somalia years of internal violence and conflict have been highly significant in creating the conditions for famine.

What is famine?

The UN uses a five-step scale, called the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), developed with NGOs including Oxfam, to assess a country’s food security. Stage 5 – “famine/humanitarian catastrophe” – requires that more than two people per 10,000 die each day, acute malnutrition rates are above 30 percent, all livestock is dead, and there is less than 2,100 kilocalories of food and 4 liters of water available per person per day In October 2009 Oxfam published a paper on Ethiopia and neighboring regions asking “what can be done to prevent the next drought from becoming a disaster?” We acknowledged that food aid saved lives but that it was not cost-effective and did not alone help people to withstand the next shock. By the time the UN calls a famine it is already a signal of large-scale loss of life. We can only ensure now that aid comes quickly and appropriately to prevent an even worse-case scenario. We must also resolve not why this famine happened but why again? And how to prevent the next one?

The causes of famine

Famines result from a combination “triple failure”:

- Production failure : In Somalia, a two-year drought – which is phenomenal in now being the driest year in the last 60 – has caused record food inflation, particularly in the expectation of the next harvest being 50% of normal. Somalia already had levels of malnutrition and premature mortality so high as to be in a “normalized” state of permanent emergency. This is true too in pockets across the entire region.

- Access failure : The drought has killed off the pastoralists’ prime livestock assets (up to 90% animal mortality in some areas), slashing further their purchasing power. In addition Somalia severe internal conflict has made development almost impossible to achieve and data difficult to access both accurately and credibly.

- Response failure : Underlying it all has been the inability of Somalia’s government and donors to tackle the country’s chronic poverty, which has marginalized vulnerable people and fundamentally weakened their ability to cope. There’s been a lack of investment in social services and basic infrastructure and lack of good governance. Meanwhile donors have reacted too late and too cautiously. The overall international donor response to this humanitarian crisis has been slow and inadequate. According to UN figures, $1 billion is required to meet immediate needs. So far donors have committed less than $200m, leaving an $800 million black hole .

How does this situation compare with current food crises in other parts of the world?

This famine represents the most serious food insecurity situation in the world today in terms of both scale and severity.

This is the first officially-declared famine in Africa so far this century, at a time when famine has been eradicated everywhere else.

What needs to be done?

The 21st Century is the first time in human history that we have the capacity to eradicate famine. To do so, we must address the underlying problems:

- Production solutions : We must accelerate investment in African food production. There are regions in Africa we know have always faced chronic food shortages, where even small blips in harvests can have terrible consequences. We need more support for small-holder farmers and pastoralists (e.g. hardier crops, cheaper inputs, disaster risk management).

- Access solutions : We must alleviate rural African poverty. More aid and budgetary investment into physical infrastructure (roads, communications etc) and allowing public intervention to correct market failures until markets are stronger (e.g. grain reserves to stop price volatility).

- Response solutions : We need to move away from discretionary assistance to guaranteed social protection e.g. such as social assistance to the poor households to access food throughout the year and insurances, so that support can be triggered automatically in times of crisis. In some contexts cash transfers can be more appropriate than food aid, where availability of food is not a problem.

Emergency aid is vital right now, but we also need to ask why this has happened, and how we can stop it ever happening again. The warning signs have been seen for months, and the world has been slow to act. Much greater long-term investment is needed in food production and basic development to help people cope with poor rains and ensure that this is the last famine in the region.

Published July 2011.

Oxfam responded to the crisis by providing life-saving water, sanitation services, food, and cash, aiming to reach at least 3.5 million people, across Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia.

A global food crisis

Conflict, economic shocks, climate extremes and soaring fertilizer prices are combining to create a food crisis of unprecedented proportions. As many as 309 million people are facing chronic hunger in 71 countries. We have a choice: act now to save lives and invest in solutions that secure food security, stability and peace for all, or see people around the world facing rising hunger.

Extreme jeopardy for those struggling to feed their families

The scale of the current global hunger and malnutrition crisis is enormous. A shocking 37.2 million people face Emergency levels of hunger, while 1.3 million people are in the grips of catastrophic hunger – primarily in Gaza and Sudan but also in pockets of South Sudan and Mali. They are teetering on the brink of famine.

Many food crises involve multiple overlapping issues driving hunger, that are building year on year. The interplay between conflict, economic shocks and the impact of the climate crisis is vital to understanding the scale of the challenge. The global community must not fail on its promise to end hunger and malnutrition by 2030.

WFP is facing multiple challenges – the number of acutely hungry people continues to increase at a pace that funding is unlikely to match , while the cost of delivering food assistance is high because food and fuel prices have increased.

Unmet needs heighten the risk of hunger and malnutrition. Unless the necessary resources are made available, lost lives and the reversal of hard-earned development gains will be the price to pay.

What is driving the global food crisis?

But why is the world hungrier than ever?

This seismic hunger crisis has been caused by a deadly combination of factors.

Conflict is still the biggest driver of hunger, with 70 percent of the world's hungry people living in areas afflicted by war and violence. Events in countries such as Palestine and Ukraine are further proof of how conflict feeds hunger – forcing people out of their homes, wiping out their sources of income and wrecking countries’ economies.

The climate crisis is one of the leading causes of the steep rise in global hunger. Climate shocks destroy lives, crops and livelihoods, and undermine people’s ability to feed themselves. Hunger will spiral out of control if the world fails to take immediate climate action.

Global fertilizer prices have climbed even faster than food prices. The effects of the war in Ukraine, including higher natural gas prices, have further disrupted global fertilizer production and exports – reducing supplies, raising prices and threatening to reduce harvests. High fertilizer prices could turn the current food affordability crisis into a food availability crisis .

On top of increased operational costs , WFP is facing major drops in funding, reflecting the new and more challenging financial landscape that the entire humanitarian sector is navigating. Almost half of WFP country operations have already been forced to cut the size and scope of food, cash and nutrition assistance by up to 50 percent.

Hunger Hotspots 2024

Publication | 5 June 2024

Hunger and malnutrition surging across West and Central Africa, says report

Story | 12 April 2024

Hunger in Gaza: Famine findings a ‘dark mark’ on the world, says WFP Palestine Country Director

Story | 18 March 2024

Hunger hotspots

From the Central American Dry Corridor and Haiti, through the Sahel, Central African Republic, South Sudan and then eastwards to the Horn of Africa, Palestine, Syria, Yemen and all the way to Afghanistan, conflict and climate shocks are driving millions of people to the brink of starvation.

In 2023, the world rallied US$8.3 billion for WFP to tackle the global food crisis. But it is not sufficient to only keep people alive. We need to go further, and this can only be achieved by addressing the underlying causes of hunger.

The consequences of not investing in resilience activities will reverberate across borders. If communities are not empowered to withstand shocks and stresses, this could result in increased migration and possible destabilization and conflict. Recent history has shown us this: when WFP ran out of funds to feed Syrian refugees in 2015, they had no choice but to leave the camps and seek help elsewhere, causing one of the greatest refugee crises in recent European history.

Let's stop hunger now

WFP’s changing lives work helps to build human capital, support governments in strengthening social protection programmes, stabilize communities in particularly precarious places, and help them to better survive sudden shocks without losing all their assets.

In just four years of the Sahel Resilience Scale-up, WFP and local communities turned 158,000 hectares of barren fields in the Sahel region of five African countries into farm and grazing land. Over 2.5 million people benefited from integrated activities. Evidence shows that people are better equipped to withstand seasonal shocks and have improved access to vital natural resources like land they can work. Families and their homes, belongings and fields are better protected against climate hazards. Support serves as a buffer to instability by bringing people together, creating social safety nets, keeping lands productive and offering job opportunities – all of which help to break the cycle of hunger.

As a further example, WFP’s flagship microinsurance programme – the R4 Rural Resilience initiative – protects around 360,000 farming and pastoralist families from climate hazards that threaten crops and livelihoods in 14 countries including Bangladesh, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Fiji, Guatemala, Kenya, Madagascar and Zimbabwe.

At the same time, WFP is working with governments in 83 countries to boost or build national safety nets and nutrition-sensitive social protection, allowing us to reach more people than we can with emergency food assistance.

Humanitarian assistance alone is not enough though. A coordinated effort across governments, financial institutions, the private sector and partners is the only way to mitigate an even more severe crisis in 2024. Good governance is a golden thread that holds society together, allowing human capital to grow, economies to develop and people to thrive.

The world also needs deeper political engagement to reach zero hunger. Only political will can end conflict in places like Palestine, Yemen, and South Sudan and Ukraine, and without a firm political commitment to contain global warming as stipulated in the Paris Agreement , the main drivers of hunger will continue unabated.

Tackling hunger

Help families facing unprecedented hunger

Advanced search

World Hunger: Causes and Solutions Essay (Critical Writing)

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Although World Hunger may seem to be completely solved for the majority of people in developed countries, it is not entirely true. Diverse issues concerning this global problem can be considered urgent or damaging for some nations or even continents. For example, despite the presence of several developing and industrial countries in Africa, most of the continent’s inhabitants lead an agricultural lifestyle and live under conditions of constant hunger. Therefore, an appropriate solution requires to be found in order to provide broad-based prosperity and admissible living conditions.

World hunger can be caused by diverse reasons, which lead to the establishment of different concepts about the issue. The most common reasons for famine are poverty, food shortages, war, armed conflicts, global warming, the economy, poor public policy and food nutrition, gender inequality, food waste, as well as forced migration. Hence, the global understanding of world hunger can be viewed in correlation with other ubiquitous issues, and the reason for various solutions is the distinctions between its diverse concepts and directions.