- Member Login

- About The Project

- Case Studies

Case Study 3 – Palliative and End-of-Life Care

Click here to review the draft palliative and end-of-life care – interactive case study..

The following case vignette provides key concepts that could be considered when developing a plan of care for a patient who may require a controlled substance to manage their health concerns. As with any clinical situation, there are many patient variables that must be considered, including comorbid conditions, social determinants of health and their personal choices. You may choose to include different or additional health history and physical examination points, diagnostic tests, differential diagnoses and treatments depending on your patient’s context however this case vignette focuses on the aspects relevant to controlled substances.

Danny Kahan NP-Adult, specialty is palliative care Joshi Kamakani – 70 year old male with metastatic prostate cancer June Kamakani – patient’s wife Kelli Kamakani – patient’s 40 year old daughter

Danny is reviewing the patient history outside the house or in the car before visiting the patient.

Joshi Kamakani is a 70 year old retired engineer that the Palliative Care home care team and I have been looking after at home for the last two months. Joshi was diagnosed with inoperable prostate cancer three years ago and has been treated with ablative hormone therapy. Six months ago, Joshi started to have pain in his hips. His oncologist ordered a CT scan and found he had metastases in his ribs, pelvis and lumbar spine. Joshi and his wife June had a meeting with the team at the cancer centre and decided not to go ahead with any further cancer treatment. Our team has been involved since. June called me yesterday and asked me to make a home visit. Joshi has been having more pain this week and has been spending most of his time on the couch. He cannot get around without assistance and is very fatigued.

Joshi’s past medical history includes hypertension and reflux. He is taking Predisone 5 mg PO BID, Leuprorelin Depot 22.5mg IM every 3 months, hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg daily and pantoprazole 40 mg daily.

For pain, Joshi takes Morphine slow release 100 mg q12h and has not needed additional medication for breakthrough pain so far.

Takes place in the home. Patient is seen reclining on couch in first floor living room. Wife and daughter present.

Danny rings the doorbell and June lets him in.

June: Hi Danny. I’m so glad you’ve come.

Danny takes off his coat and shoes and walks into the living room. Kelli is sitting with her father who is covered up with a blanket on a couch in the main living area – he is awake but obviously drowsy. He smiles at Danny and holds out his hand. Danny shakes it a sits down in a chair opposite.

June: His pain killers just are not working any more – he’s uncomfortable when he is resting and it’s worse when he has to move around. It’s been happening for the last few weeks. He hasn’t had a fall but he is unsteady on his feet – especially soon after he get up. Joshi: I tried some acetaminophen from the drug store a few days ago but it really didn’t work. Kelli: Danny, you have to do something. He’s so uncomfortable. Danny: OK let’s talk about this a bit more. Joshi, were you sleepy after we increased the morphine 2 weeks ago? You were at 80 mg for each dose and now you are at 100 mg. Joshi: I was a bit sleepy for a few days and I had a bit of a weak stomach but that is gone now. I am a bit constipated though. Danny: when did you have your last bowel movement? Joshi: 4 days ago. Danny: OK we will have to address that today. I’d like to use the scale that I used at our last visit, it’s called the PPS, to assess your level of activity. ( Edmonton symptom assessment scale and Palliative Performance Score). Your PPS is 40% – last time I visited you were at 60%. June: yes, he is definitely having more trouble. I think the pain is preventing him from moving and that’s just making everything worse.

Danny: Joshi, your pain interference score tells me that the pain is severely interfering with your activity and I see that you are rating your current pain at rest at 6/10 and at 10/10 when you move. When I examined you, I did not note any changes from my last visit except for some new swelling over your left hip. June: Yes that’s where it is most sore – and before you ask, I am not going to the hospital for an xray. Kelli: Why can’t you just double his dose?

Danny [THINKS]: I will also add a bowel regime to address Joshi’s constipation and provide an order for a PRN anti-nauseant like metoclopramide or ondansetron. Joshi and his family will need to have education about the timeline of the peak benefit of the change in the regular dose, keeping track of PRN use, proper use of breakthrough medications (before care or any activity that causes pain), any other interventions we can include to help with his pain including adding other medications.

June: Danny, can I speak to you in private for a moment? June and Danny move to a private area of the house. Kelli and Joshi remain on the sofa. June: Danny, I have some concerns about having extra medication in the house and I need some advice on how to deal with this. My daughter had a real problem with drugs when she was in high school. She had to have treatment and as far as I know, she has been clean for the past 2 years. I have talked to her about having medication in the house and she tells me she’s not tempted but I really want to be sure we don’t have any incidents. I trust my daughter but I do worry that some things are beyond her control. Danny: Well June, it is always a good practice to have a plan for safe storage of medications. Here is some information about where you can purchase a locked box. I recommend you keep a key and have the hospice nurse take the other and have it numbered and controlled at the hospice office for the use of the nurses that care for Joshi. In the meantime, keep the medications in a place that you and Joshi can monitor and please keep a count of the medication in the containers and continue to write down when medication is given. June: Thanks Danny – I don’t want my daughter to think I don’t trust her. This should help.

Two weeks later – Danny is back in his office reviewing Joshi’s file with a Nurse Practitioner student…

Follow-up case question by Danny.

Student: Next up is Joshi Kamakani for review… Danny: Well, I’ve just been to see Joshi and his family. It has been two weeks since we increased his dose of morphine SR. We also added a neuropathic pain agent to help with his pain which has made him a bit more drowsy. He continues to take 20-30 mg breakthrough morphine/day and I noticed today that he has some myoclonus. Joshi’s pain is still in the moderate range with activity and now nausea is a problem.

Opioid rotation and opioid equianalgesia from NOUGG (McMaster Guidelines).

Danny: I think a rotation of opioid is the next step. Student: What medication should Danny consider and at what dose?

Danny: Joshi is using 270 mg oral morphine equivalents per day. To convert this dose to hydromorphone, the medication I have chosen to rotate to, we multiply by 0.2. Morphine 270 mg x 0.2 = 54 mg hydromorphone/day. We will want to convert 60% of the total daily dose so 54mg x .6 = 32mg. I want to give Joshi the new dose in a slow release form. It is most practical to provide Joshi with hydromorphone SR 15mg q12h and also provide him an additional 2-3 mg of hydromorphone immediate release for breakthrough pain. Providing him with the breakthrough dosing will be sure Joshi can have additional medication to help him until we are sure we have a stable, effective dose in 48-72 hours.

Learning Outcome

This interactive case study covered the following information:

- Opiate Titration

- Opiate Rotation

- Pain Assessment

- Assessment of adverse effects

- Safety Assessment

- Collaboration

- Family centred care

Building public engagement and access to palliative care and advance care planning: a qualitative study

Affiliations.

- 1 Institute of Nursing and Health Research, Ulster University, Belfast, BT15 1AD, Northern Ireland.

- 2 Institute of Nursing and Health Research, Ulster University, Belfast, BT15 1ED, Northern Ireland.

- 3 Institute of Nursing and Health Research, Ulster University, Belfast, BT15 1AD, Northern Ireland. [email protected].

- PMID: 38605315

- DOI: 10.1186/s12904-024-01420-8

Background: Research evidence suggests that a lack of engagement with palliative care and advance care planning could be attributed to a lack of knowledge, presence of misconceptions and stigma within the general public. However, the importance of how death, dying and bereavement are viewed and experienced has been highlighted as an important aspect in enabling public health approaches to palliative care. Therefore, research which explores the public views on strategies to facilitate engagement with palliative care and advance care planning is required.

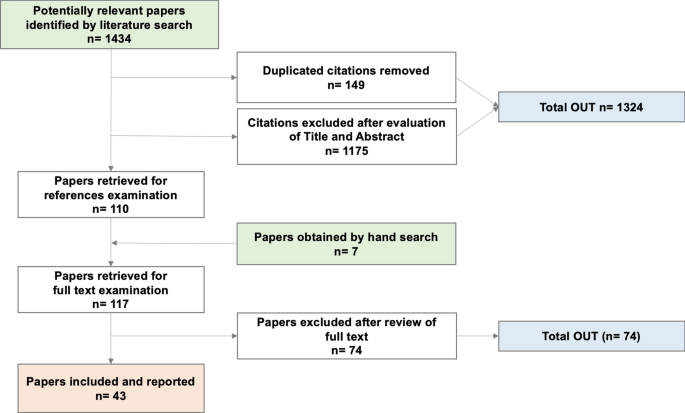

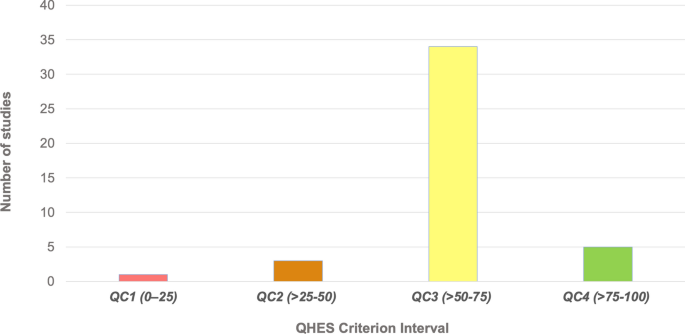

Methods: Exploratory, qualitative design, utilising purposive random sampling from a database of participants involved in a larger mixed methods study. Online semi-structured interviews were conducted (n = 28) and analysed using reflexive thematic analysis. Thematic findings were mapped to the social-ecological model framework to provide a holistic understanding of public behaviours in relation to palliative care and advance care planning engagement.

Results: Three themes were generated from the data: "Visibility and relatability"; "Embedding opportunities for engagement into everyday life"; "Societal and cultural barriers to open discussion". Evidence of interaction across all five social ecological model levels was identified across the themes, suggesting a multi-level public health approach incorporating individual, social, structural and cultural aspects is required for effective public engagement.

Conclusions: Public views around potential strategies for effective engagement in palliative care and advance care planning services were found to be multifaceted. Participants suggested an increase in visibility within the public domain to be a significant area of consideration. Additionally, enhancing opportunities for the public to engage in palliative care and advance care planning within everyday life, such as education within schools, is suggested to improve death literacy and reduce stigma. For effective communication, socio-cultural aspects need to be explored when developing strategies for engagement with all members of society.

Keywords: ACP; Advance care planning; Death and dying.; Death literacy; Palliative care; Public engagement; Public health; Social Ecological Model.

© 2024. The Author(s).

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Health Serv Res

What is case management in palliative care? An expert panel study

Annicka g m van der plas.

1 Department of Public and Occupational Health, EMGO Institute for Health and Care Research, VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

2 Palliative Care Center of Expertise, VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Bregje D Onwuteaka-Philipsen

Marlies van de watering.

3 Kennemer Gasthuis, Haarlem, the Netherlands

Wim J J Jansen

4 Department of Anaesthesiology, VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

5 Agora, National Support Center for Palliative Terminal Care, Bunnik, the Netherlands

Kris C Vissers

6 Department of Anaesthesiology, Pain, and Palliative Medicine, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands

Luc Deliens

7 End-of-Life Care Research Group, Ghent University and Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium

Associated Data

Case management is a heterogeneous concept of care that consists of assessment, planning, implementing, coordinating, monitoring, and evaluating the options and services required to meet the client's health and service needs. This paper describes the result of an expert panel procedure to gain insight into the aims and characteristics of case management in palliative care in the Netherlands.

A modified version of the RAND®/University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) appropriateness method was used to formulate and rate a list of aims and characteristics of case management in palliative care. A total of 76 health care professionals, researchers and policy makers were invited to join the expert panel, of which 61% participated in at least one round.

Nine out of ten aims of case management were met with agreement. The most important areas of disagreement with regard to characteristics of case management were hands-on nursing care by the case manager, target group of case management, performance of other tasks besides case management and accessibility of the case manager.

Conclusions

Although aims are agreed upon, case management in palliative care shows a high level of variability in implementation choices. Case management should aim at maintaining continuity of care to ensure that patients and those close to them experience care as personalised, coherent and consistent.

Patients facing a life-threatening illness are likely to experience palliative care needs [ 1 , 2 ]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), palliative care aims at improving the quality of life of patients and their families, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, emotional, and spiritual [ 3 ]. Palliative care is complex care. Firstly because it demands attention to and knowledge of not only disease, pain and symptom management, but also a range of other non-medical issues from reimbursement structures to availability of social services and spiritual care [ 3 ]. Gaps in the general and specialist knowledge required by the health care provider must be filled by access to reliable knowledge from others. Secondly, communication plays a pivotal role; several professionals and informal caregivers across settings can be involved and round-the-clock continuity of information is necessary to deliver consistent care sensitive to rapidly changing needs. In 98% of their palliative care patients, Dutch General Practitioners (GPs) cooperate with at least one other caregiver, with a mean number of four [ 4 ]. In the Netherlands, about half of patients experience one or more transfers in their last month of life [ 5 ], implying the need for communication across settings at least at the start of the transfer period. This will probably be even more true in future with increasing life expectancy and a growing number of patients with multiple chronic diseases [ 6 ] resulting in, among other things, more health care needs and more need for the coordination of care.

Case management has developed as a means of ensuring continuity of care for patients with complex care needs. It is a heterogeneous term for care that consists of assessment, planning, implementation, coordination, monitoring and evaluation of the options and services required to meet the client's health and service needs [ 7 ]. It has been used for many years in psychiatry [ 8 ], among frail elderly people [ 9 ] and many other populations. There have been varying research results on its effectiveness. There are numerous models of and variations in ways of delivering case management [ 10 ]. Adding to the confusion is the multitude of names given to case management; care management, care coordination, disease management, and managed care being some of the most common in the nursing field. Most studies compare one application of case management with care as usual, there is little research comparing different models or applications of case management. It is difficult to compare studies due to differing methodologies and outcome measures, and unclear definitions and descriptions of case management [ 11 - 13 ]. Therefore, we conclude that based on current research, for most medical conditions there is no way of identifying the best model for delivering case management.

The same can be said for case management in palliative care. No reviews on case management in palliative care were found and there is no definitive evidence of its effectiveness in palliative care. Some positive results are reported. In a randomised trial among patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart failure (CHF) or cancer, case management resulted in increased patient satisfaction with care and the earlier development of advance directives [ 14 ]. In patients with advanced illness (mostly cancer) receiving case management, compared with a matched historical control group, hospice use and number of hospice days increased [ 15 ]. There appear to be variations in the application of case management in palliative care. Differences can be seen in target populations (e.g. cancer only [ 16 ] or a range of diagnoses [ 17 ]), whether principles of disease management should be integrated [ 18 ] or focus should be solely on terminal care [ 19 ], whether case management should be delivered by a multidisciplinary team [ 20 ] or not [ 15 ] and a broad range of other variations. Again, these studies cannot be compared, therefore, no conclusions can be drawn as to which application of case management should be preferred.

The question of how case management should best be delivered in palliative care is unanswered. The purpose of this study was to formulate the aims of case management and describe essential characteristics of case management in palliative care in the Netherlands, as perceived by experts. The expert panel procedure also gave insight into which topics there is consensus between experts and what are the main differences in opinion between them.

The RAND® / University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) appropriateness method is developed to combine scientific evidence with the collective judgment of experts to yield a statement regarding the appropriateness of performing a procedure at the level of patient-specific symptoms, medical history and test results [ 21 ]. The aim of this method is to reach consensus on which medical procedures are appropriate in certain medical conditions and circumstances. With a modified version of this method it is possible to investigate whether there is consensus or disagreement for a diverse range of topics. In three written rounds we consulted experts to formulate and rate aims and characteristics of case management in palliative care. Purpose of round 1 and 2 was to formulate a list of aims and characteristics, in the third round experts rated the aims and characteristics on importance for successful implementation of case management in palliative care.

Expert panel

We invited 73 experts with experience in palliative care to participate in the expert panel: general practitioners, coordinators of palliative care networks, case managers working in palliative care, researchers and policy makers in palliative care. The perspective of district nurses was included in the expert panel through case managers and scientists in the field of nursing. Two experts declined but proposed four others to take their places and the colleague of another was added leading to the questionnaire being sent to 76 experts. Of those, 46 (61%) participated in at least one round. Twenty-four experts gave their reasons for not participating: lack of time (n = 13), lack of knowledge about case management (n = 7), prolonged illness (n = 4). Four reactions in the first round and two in the second were not traceable because they were returned anonymously. This study is exempt from approval from an ethics committee.

Selection of aims and characteristics

We drafted a first list of aims and characteristics of case management in palliative care based on information from existing initiatives, literature and previous research. We used four headings to partition our list of aims and characteristics: aims of case management in palliative care, characteristics of content of case management in palliative care, characteristics of structure of case management in palliative care and general conditions. The 16 characteristics in the fourth section, general conditions, related so commonly to care in general (e.g. 'the caseload is in ratio with the terms of employment of the case manager and the necessary time investment for individual patients') that they were omitted for the purposes of this paper.

For the aims of case management in palliative care, we made use of the conceptual framework of continuity of care by Bachrach [ 22 ]. She identified seven dimensions in continuity of complex care. The dimensions put together describe an ideal model for care in situations where several health care providers, settings and/or needs are involved. Case management does not necessarily incorporate all elements in itself, but its task is to make sure the patient receives continuity of care. Bachrach listed these dimensions specifically for people with long-term mental disorders, and we hypothesised that they would be useful as a starting point in identifying the aims of case management in palliative care. We reformulated the characteristics to reflect palliative terminology and discourse. Additional to the seven characteristics derived from Bachrach, we added two more, one specifically on palliative care (care or coordination of care is aimed at quality of life and death) and the other because the literature suggests that continuity of care across settings is problematic in palliative care [ 23 , 24 ] and we hypothesised that case management should pay special attention to that aspect. In Table 1 the dimensions of Bachrach and the aims of case management are reported.

Transformation of dimensions of continuity of care to aims of case management in palliative care sent to the expert panel for feedback in round 1

In three written rounds the experts were asked to formulate and rate aims and characteristics of case management in palliative care. In the first round we presented the first draft of the list of aims and characteristics and the expert was asked to add and remove some, give textual feedback and feedback on the aims and characteristics included. For readability characteristics were clustered around themes within the sections; aims of case management in palliative care, characteristics of content of case management, characteristics of structure of case management, and general conditions. In the second round we sent a new draft based on the respondents' feedback, with the same question. No reaction was required if the participant agreed with the content and formulation. In order to be rated independently in the third round, the clusters were then divided into separate characteristics (see Table 2 for an example). Thus, a list of 41 clustered aims and characteristics was divided into 104 separate aims and characteristics. In the third round the expert panel rated all aims and characteristics on a nine-point scale, a score of one indicating that the aim or characteristic was 'not important for successful implementation' and of nine that it was 'very important for successful implementation' of case management in palliative care.

Example of a clustered characteristic in round 2 and division into separate characteristics for round 3

Data analysis

We calculated the mean, standard deviation, median and median absolute deviation (M.A.D.) for all aims and characteristics. Agreement was calculated according to the procedure described by the RAND Corporation specifically designed for expert panels with more than nine participants [ 21 ]. Thus, according to the RAND criteria, for an aim or characteristic to be considered important for successful implementation of case management two requirements for agreement had to be met:

1) the expert panel agreed with the aim or characteristic, meaning that an aim or characteristic was scored 7 to 9 by 80% of participants,

2) the expert panel agreed with each other, meaning that the Interpercentile Range Adjusted for Symmetry (IPRAS) is larger than the Interpercentile Range (IPR). We used .30 and .70 percentile scores to calculate the lower and upper limit of the IPR.

All other results are categorised as 'disagreement'. We used the M.A.D. as an estimator of dispersion to assess the level of disagreement within the expert panel. This measure is less susceptible to outliers than the standard deviation. To distinguish between a high and a moderate level of disagreement we used a cut off score of M.A.D. = 2.0.

Round 1 and 2

In the first round we received 35 reactions on the aims and characteristics. In Table 3 the response is shown differentiated by the discipline of the participants. Main topics addressed by the experts on the first draft were: inclusion of informal caregivers (family, partner) in case management, communication and role delineation between the case manager and other health care professionals and the necessity of tailoring care to individual needs and wishes. Also, wording of the aims and characteristics was altered accordingly to feedback from the expert panel. This resulted in an adapted draft sent around for round two. In the second round we received 12 reactions on the adapted draft. The feedback on this draft mainly concerned suggestions for improvements in detail. The complete list of aims and characteristics for case management in palliative care formulated after round two is reported in Additional file 1 .

Background characteristics of respondents per round

1 Some responses could not be traced, we are not certain whether the two unknown respondents from round two did or did not respond in round one. The total number may be between 4 and 6.

2 Some responses could not be traced, we are not certain whether the two unknown respondents from round two are unique, so the number of persons with one or more responses is between 46 and 48.

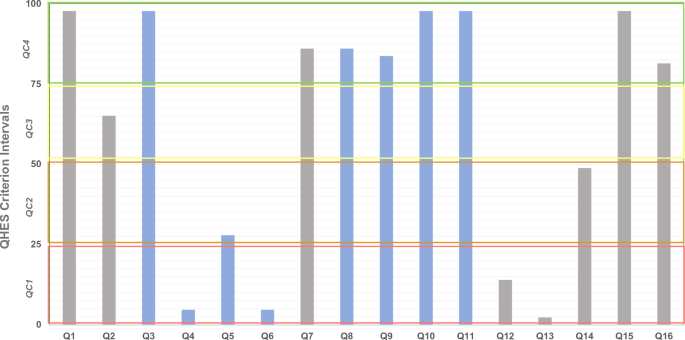

In the third round we received 34 reactions from the expert panel. Table 4 shows that agreement was reached on 35 aims and characteristics. Overall, about a third of the aims and characteristics met with agreement (34%), almost half with a moderate level of disagreement (49%), and less than a fifth (17%) with a high level of disagreement. Both aims and characteristics which are met with agreement and with a high level of disagreement are marked in the Additional file 1 . There were no notable differences between experts from different backgrounds on rating the aims and characteristics (see the Additional file 1 for mean and median scores).

Scoring of the aims and characteristics by the expert panel

Aims of case management in palliative care

In section one on aims almost all aims were met with agreement (90%) and none with a high level of disagreement. The one aim with a moderate level of disagreement (Additional file 1 , aim 1.2) used the term ‘care on demand’ ('vraaggestuurd'), which is used by Dutch policy makers to indicate that the patient is central to care as opposed to 'care as supplied' ('aanbod gestuurd') which prioritises the habits, rules and regulations of the institution delivering it. This characteristic was added at the request of some of the experts because they felt that aim 1.4 on individual care did not adequately cover the aspect of care on demand. However, we received questions on this term (e.g. 'does this mean that care should not be proactive?') that made clear that the denotation of the term is not well known among the expert panel. At the same time we received feedback indicating that the expert panel agrees that the patient should be at the centre of care and that it should be tailored to the individual needs of the patient and aim 1.4 was met with a high level of agreement.

Content of case management in palliative care

In section two on content of case management most characteristics were met with a moderate level of disagreement (44%), while another 40% were met with agreement and a small proportion with a high level of disagreement (17%). Within this section the highest level of disagreement (M.A.D. = 2.33) was on nursing care tasks (characteristic 2.1.a). This stems from the opinion of some experts that the number of health care providers surrounding the patient should be kept as low as possible. The district nurse can perform case management next to other duties. Others believe that district nurses, due to their busy schedules, do not have time to offer patients adequate comfort, reassurance and information and this will take second place to their nursing tasks. Comfort, reassurance and information may also be needed by patients who are not yet using care from a district nurse.

Structure of case management in palliative care

In section three on structure of case management most characteristics were met with a moderate level of disagreement (63%), while 22% encountered a high level of disagreement and only 15% were met with agreement. Within this section there were three characteristics with a joint highest level of disagreement (M.A.D. = 2.24): whether the case manager should combine case management with other tasks (e.g. consultation) (characteristic 3.5.b), whether she or he should be accessible 24 hours a day, seven days a week (characteristic 3.8.a), and if the target group she or he works for includes all patients with a life-threatening disease (characteristic 3.7.c).

This study shows that agreement was high on the aims of case management. However, how case management should be implemented, and exactly which elements of care it should include, is more open for debate. Disagreement was highest on topics regarding whether the case manager should perform hands-on nursing care themselves or not, on the target group, on accessibility of the case manager and on performance of other tasks besides case management.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study using a structured procedure to report on the importance of the aims and characteristics of case management in palliative care. The expert panel reflects the opinions of case managers, coordinators of palliative care networks, general practitioners and other physicians, researchers and policy makers. There were no marked differences between experts from different backgrounds on rating the aims and characteristics. However, these opinions not necessarily reflect practice and we lack information on how often and how case management is implemented in the Netherlands. Also, our results may only be representative for mixed public-private health care systems with a strong primary care gatekeeper that resemble the Dutch system. The characteristics of case management may be different in other health care systems.

The aims that met agreement are in accordance with the general principles of palliative care and also reflect the patient advocacy model of case management [ 25 ]. This model offers comprehensive coordination of services aimed at quality of care and is distinguished from the interrogative model, which is more focused on clinical decision-making and emphasises cost-effectiveness. The aims also underline the importance of the seven dimensions of continuity of care formulated by Bachrach for psychiatric care [ 22 ]. This conceptual framework appears to be valid for complex continuous care in general, whether it is psychiatric care or palliative care.

Translation from aims to content of care is apparently relatively straightforward, with 40% agreement and only 17% strong disagreement on what care should be included. Offering information and support, identifying needs and adjusting care to match the patient's needs are the main tasks of the case manager. This can also be seen in descriptions of case management in palliative care [ 20 , 26 ], for cancer patients [ 27 ] and in a Delphi study on case management for patients with dementia [ 28 ]. Delivery of hands-on patient care is the most important area of disagreement within the expert panel. As mentioned in the results section, this stems from task alignment between the district nurse and case manager and whether these should be two different people or not. Besides, this also touches on the discussion whether palliative care should be part of primary (generalist) care, delivered by specialised palliative care providers, or in a cooperation between the two [ 29 ]. Case management could be delivered in a multidisciplinary team taking over all care, or case management can be guiding and assisting the primary health care providers (GP and district nurse) in their care for the patient. Another notable topic of disagreement is whether case management should stop before bereavement support is provided. The panel agrees that bereavement support is part of palliative care, reflected in agreement with characteristic 2.18.c. and aim 3. Whether there can be other endpoints for case management may be related to the target group, which is also a point of disagreement for the expert panel (reflected by characteristics 3.7 a, b and c). In a mixed-method study on case management for cancer patients, there are two distinct case management trajectories for patients receiving curative care and those receiving palliative care [ 27 ]. For curative patients case management can be short-term and stops when information needs are met. The discussion on bereavement support may also be a reflection of the Dutch reimbursement system, where it is not financed by public means and therefore any time the case manager spends on delivering it is not compensated.

Translation from aims to structure of case management is apparently less straightforward, with only 17% agreement and 22% strong disagreement. Characteristics such as the target group and the accessibility of the case manager may reflect the scope and depth of the case manager’s task: when can she or he work with the patient themselves and at what point does she or he refer to another professional? In the aforementioned Delphi study on case management for patients with dementia, no agreement could be reached on similar topics [ 28 ]. Apparently, in correspondence with applications of case management in cancer [ 11 ], CHF [ 12 ] and dementia [ 13 , 28 ], also in palliative care there is no unique best way to deliver case management according to experts.

Case management in palliative care should aim at maintaining continuity of care to ensure that patients and those close to them experience palliative care as personalised, coherent and consistent. There is a high level of agreement about the underlying dimensions of continuity of care [ 22 ]. The most important issues in implementation preferences are defining the target group of case management, the performance of other tasks besides case management, accessibility of the case manager and delivery of hands-on nursing care by the case manager. Research into the feasibility of different options and their effects on implementation could help health care planners make informed decisions on the best way to deliver case management.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing of interest.

Authors’ contributions

AvdP participated in the design of the study, carried out the measurements, analysed and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. BO-P conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination and made substantial contributions to the data interpretation and writing of the paper. MvdW, WJ, KV and LD participated in design of the study, interpretation of the data and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/12/163/prepub

Supplementary Material

Aims and characteristics of case management in palliative care. This file contains a full list of all aims and characteristics of case management in palliative care, as formulated and rated by the expert panel. (PDF 129 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank ZONMw (grant number 80-82100-98-066) for their financial support. The funders had no role in data collection and analysis, selection of respondents, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

- Jaul E, Rosin A. Planning care for non-oncologic terminal illness in advanced age. IMAJ. 2005; 7 :5–8. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McIlfatrick S. Assessing palliative care needs: views of patients, informal carers and healthcare professionals. JAN. 2007; 57 :77–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04062.x. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sepulveda C, Marlin A, Yoshida T, Ullrich A. Palliative care: the World Health Organization's global perspective. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2002; 24 :91–96. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00440-2. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Borgsteede SD, Deliens L, van der Wal G, Francke AL, Stalman WA, van Eijk JT. Interdisciplinary cooperation of GPs in palliative care at home: a nationwide survey in The Netherlands. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2007; 25 :226–231. doi: 10.1080/02813430701706501. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Abarshi E, Echteld M, Van den Block L, Donker G, Deliens L, Onwuteaka-Philipsen B. Transitions between care settings at the end of life in the Netherlands: results from a nationwide study. Palliat Med. 2010; 24 :166–174. doi: 10.1177/0269216309351381. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Van den Akker M, Buntinx F, Metsemakers JF, Roos S, Knottnerus JA. Multimorbidity in general practice: prevalence, incidence, and determinants of co-occurring chronic and recurrent diseases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998; 51 :367–375. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(97)00306-5. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Commission for Case Manager Certification. Definition of Case management. Accessed 14-6-2010. http://www.cmsa.org/Home/CMSA/WhatisaCaseManager/tabid/224/Default.aspx .

- Dixon L, Goldberg R, Iannone V, Lucksted A, Brown C, Kreyenbuhl J. et al. Use of a critical time intervention to promote continuity of care after psychiatric inpatient hospitalization. Psychiatr Serv. 2009; 60 :451–458. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.4.451. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bernabei R, Landi F, Gambassi G, Sgadari A, Zuccala G, Mor V. et al. Randomised trial of impact of model of integrated care and case management for older people living in the community. BMJ. 1998; 316 :1348–1351. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7141.1348. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Huber DL. The diversity of case management models. Lippincotts Case Manag. 2002; 7 :212–220. doi: 10.1097/00129234-200211000-00002. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wulff CN, Thygesen M, Sondergaard J, Vedsted P. Case management used to optimize cancer care pathways: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008; 8 :227–234. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-227. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Whellan DJ, Hasselblad V, Peterson E, O'Connor CM, Schulman KA. Metaanalysis and review of heart failure disease management randomized controlled clinical trials. Am Heart J. 2005; 149 :722–729. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.09.023. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pimouguet C, Lavaud T, Dartigues JF, Helmer C. Dementia case management effectiveness on health care costs and resource utilization: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Nutr Health Aging. 2010; 8 :669–676. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Engelhardt JB, Clive-Reed KP, Toseland RW, Smith TL, Larson DG, Tobin DR. Effects of a program for coordinated care of advanced illness on patients, surrogates, and healthcare costs: a randomized trial. Am J Manag Care. 2006; 12 :93–100. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Spettell CM, Rawlins WS, Krakauer R, Fernandes J, Breton ME, Gowdy W. et al. A comprehensive case management program to improve palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2009; 12 :827–832. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0089. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Seow H, Piet L, Kenworthy CM, Jones S, Fagan PJ, Dy SM. Evaluating a palliative care case management program for cancer patients: the Omega Life Program. J Palliat Med. 2008; 11 :1314–1318. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0140. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Head BA, Lajoie S, Augustine-Smith L, Cantrell M, Hofmann D, Keeney C. et al. Palliative care case management: increasing access to community-based palliative care for medicaid recipients. Prof Case Manag. 2010; 15 :206–217. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Aiken LS, Butner J, Lockhart CA, Volk-Craft BE, Hamilton G, Williams FG. Outcome evaluation of a randomized trial of the PhoenixCare intervention: program of case management and coordinated care for the seriously chronically ill. J Palliat Med. 2006; 9 :111–126. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.111. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Back AL, Li YF, Sales AE. Impact of palliative care case management on resource use by patients dying of cancer at a Veterans Affairs medical center. J Palliat Med. 2005; 8 :26–35. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.26. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Holley APH, Gorawara-Bhat R, Dale W, Hemmerich J, Cox-Hayley D. Palliative access through care at home: experiences with an urban, geriatric home palliative care program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009; 57 :1925–1931. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02452.x. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aguilar MS, Burnand B, LaCalle JR, Lazaro P, The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method User's Manual. 2001.

- Bachrach LL. Continuity of care for chronic mental patients: a conceptual analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 1981; 138 :1449–1456. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hauser JM. Lost in transition: the ethics of the palliative care handoff. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2009; 37 :930–933. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.02.231. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Meier DE, Beresford L. Palliative care's challenge: facilitating transitions of care. J Palliat Med. 2008; 11 :416–421. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.9956. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Long MJ, Marshall BS. What price an additional day of life? A cost-effectiveness study of case management. Am J Manag Care. 2000; 6 :881–886. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Head BA, Cantrell M, Pfeifer M. Mark's journey: a study in medicaid palliative care case management. Prof Case Manag. 2009; 14 :39–45. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Howell D, Sussman J, Wiernikowski J, Pyette N, Bainbridge D, O'Brien M. et al. A mixed-method evaluation of nurse-led community-based supportive cancer care. Support Care Cancer. 2008; 16 :1343–1352. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0416-2. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Verkade PJ, van Meijel B, Brink C, van Os-Medendorp H, Koekkoek B, Francke AL. Delphi research exploring essential components and preconditions for case management in people with dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2010; 10 :54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-10-54. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gott M, Seymour J, Ingleton C, Gardiner C, Bellamy G. 'That's part of everybody's job': the perspectives of health care staff in England and New Zealand on the meaning and remit of palliative care. Palliat Med. 2012; 26 :232–241. doi: 10.1177/0269216311408993. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Case-based learning: palliative and end-of-life care in community pharmacy

Community pharmacists encounter patients at all stages in their life; however, patients who require palliative care require dedicated time and special consideration.

JL / Shutterstock.com

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines palliative care as an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with life-threatening illness. This is achieved through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment, and treatment of pain and other problems [1] .

Palliative care is often considered to be only for patients with cancer, but it also incl udes patients with conditions such as organ failure (e.g. heart failure , COPD, renal and hepatic failure), neurological conditions (e.g. multiple sclerosis , Parkinson’s disease and motor neurone disease), dementia, frailty , stroke and HIV/AIDS [2] , [3] , [4] .

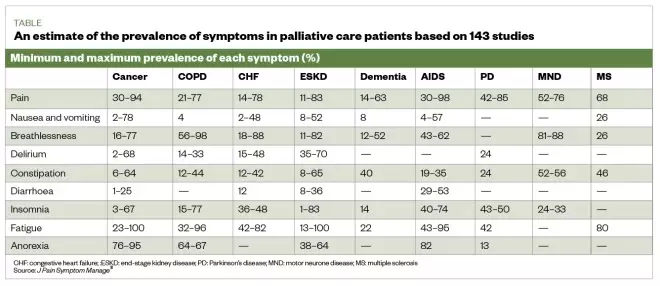

The same can be said when considering symptoms (see Table) [5] . Being symptom-free is one of the most important factors for patients when considering end-of-life care [6] . Pharmacists have much to offer, not only in providing medicines required for symptom management, but also supporting patients and their carers to receive the right care at the right time [2] , [7] , [8] .

Table: an estimate of the prevalence of physical symptoms in palliative patients based on results from 143 studies

Source: J Pain Symptom Manage [5]

Symptom management

How symptoms are treated may change over time and may depend on many factors, including the symptom being treated, the patient’s ability to swallow (owing to disease process causing fatigue and weakness), and level of consciousness. Although most symptoms can be treated with oral preparations, it is likely that the oral route will become less available and a switch to parenteral preparations may be required.

The Gold Standards Framework recommends considering anticipatory prescribing of subcutaneous formulations for pain, nausea and vomiting, agitation/restlessness and excess respiratory secretions (also known as ‘death rattle’) [9] , [10] . The anticipatory prescribing of these medicines is part of advance care planning (i.e. the conversation between the patient’s families and carers about their future wishes and priorities for care) [11] , [12] .

The way symptoms are treated in patients receiving palliative care may change over time; however, several factors may influence this. For example, the Gold Standards Framework recommends considering subcutaneous formulations for:

- Nausea and vomiting;

- Agitation/restlessness;

- Excess respiratory secretions [12] .

Pharmacy schemes across the UK exist to act as stockists for locally selected anticipatory medicines, including alternative anti-emetics, opiates and steroids. See the Local Pharmaceutical Committee website for details (see Useful resources ). Be aware of the local pharmacies enrolled in these schemes, to ensure the pharmacy team can advise patients or carers if needed.

The Gold Standards Framework also suggests five steps for healthcare professionals to consider when advance care planning for patients, which are:

- Thinking about the future and what is important to the patient;

- Talking with family and friends about the patient’s choices so they are aware of them and can act as a spokesperson should the patient become unable to do this for themselves;

- Recording the patient’s wishes;

- Discussing plans with healthcare teams involved in the patient’s care (this may include conversations about resuscitation);

- Sharing information with the people who will need to be aware of it [12] .

An advance care plan can include many details, such as the desired extent of active treatment; the patient’s preferred place of care at the end of life; preferences for symptom management (e.g. the level of sedation a patient finds acceptable); people they would like to be present at end of life; spiritual and religious needs; and thoughts around funeral planning.

The Palliative Care Formulary provides excellent information and guidance on dosing and routes, which are often outside of the product license [10] . The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has also published several documents to support healthcare professionals in their approach to palliative care [13] (see Useful resources ).

Role of the pharmacist

Towards the end of a patient’s life, drug treatments should be as minimised when possible, with pharmacists reviewing and advising on deprescribing [7] , [14] . Pharmacists should also support patients in fulfilling their wishes to die in the place they choose with their symptoms well managed [8] .

The role of pharmacists in palliative care should be much greater than a supply function, although the importance of stocking anticipatory medicines should not be underestimated. Patients and their carers value more than the basic level of service from the pharmacy, and appreciate friendliness from staff who are familiar with them and can provide support with medicines and symptom management [15] .

The complex and often changing medicines regimens for palliative care patients can be challenging for medicines optimisation. Providing clear instructions on regimens and general communication can help (see Box 1 ) [10] . It is important to establish what medicines the patient is taking and when, and support and simplify their regimen if possible. For example, a patient is instructed to take paracetamol 1,000mg four times a day at 08:00, 12:00, 16:00 and 20:00, but wakes during the night with pain. Instead, the patient could be advised to take the paracetamol at equal intervals throughout the 24-hour period, (e.g. every six hours) [10] . However, this decision would need to take into consideration the patients waking hours and preferences.

The following case describes how pharmacists can assist patients nearing end of life with management of pain, nausea and constipation, and anticipatory prescribing.

Box: Considerations to take into account when communicating with palliative care patients and carers

Aims of communication :

- Information sharing;

- Reducing uncertainty;

- Facilitating choices and joint decision making;

- Creating, developing and maintaining relationships .

Getting started:

- Make time for the conversation, even if it is only for a few uninterrupted minutes;

- Ensure privacy;

- Introduce yourself;

- Indicate clearly that you have time to listen (e.g. offer to sit down with them);

- Use open questions to obtain information and allow the patient to talk (e.g. “what do you think this medicine is for?”);

- Engage using active listening (e.g. nodding and summarising to check information).

Be aware of non-verbal communication, such as:

- Facial expression;

- Eye contact;

- Posture (whether sitting or standing);

- Pitch and pace of voice;

- Use of appropriate touch.

Try to recognise barriers to good communication, for example:

- Language (patient’s own language or the use of jargon);

- Poor hearing, feeling generally unwell, fatigued, distracted by symptoms, fear and anxiety;

- Poor transfer of care information;

- Lack of time and privacy.

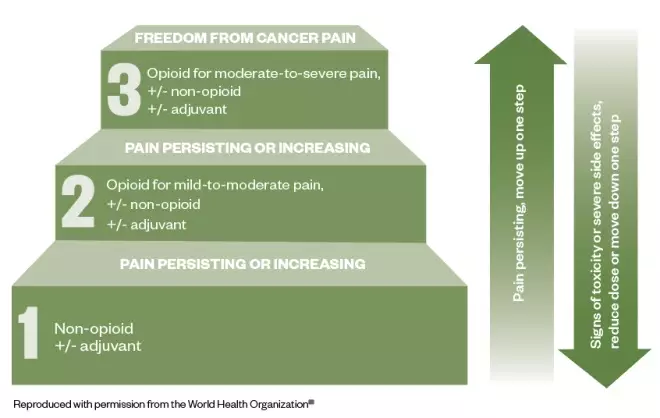

Figure: the three-step analgesic ladder

Source: World Health Organization [16]

This cancer pain management ladder provides a general guide to treatment based on the severity of pain

Palliative care part 1: pain management

Mary*, aged 54 years, comes into the pharmacy and asks to speak to the pharmacist about her prescribed medicines. She was recently diagnosed with metastatic pancreatic cancer, and her GP and palliative care team are working to manage her pain.

Two weeks ago, Mary was started on paracetamol 1,000mg four times per day and morphine sulphate liquid 5mg (2.5mL) every two to four hours as required. She was previously prescribed codeine 30–60mg four times per day, but this did not help to relieve her symptoms. On average, she has been taking six doses of morphine sulphate 5mg in each 24-hour period, and although this helps, it does not completely alleviate her pain.

Today, Mary has been prescribed morphine sulphate (MST; Napp Pharmaceuticals) 15mg twice daily and has been told to continue with her paracetamol and morphine sulphate liquid (for breakthrough pain). Mary explains that her GP said there may be a need to add a medicine for nerve pain. However, Mary goes on to say that she is worried that she is taking “too much” medicine and she is reluctant to take all of these medicines, especially if another may be added for nerve pain.

Actions and recommendations

The pharmacist should consider the following during the consultation:

- Communication — open questions should be used to determine how much has been explained to Mary about pain management. It may be that she has been given an explanation, but it is often worth covering these again;

- World Health Organization pain ladder — explain the use of the ladder (see Figure), including the need to use regular paracetamol;

- Analgesia — patients are often concerned by using more than one opiate. Patients may need to be encouraged to use their breakthrough analgesia when required, explaining how the dose is determined by the background analgesia may help [17] ;

- Keeping a diary — Mary should be encouraged to keep a pain diary. This can be a benefit as keeping a record of breakthrough doses may help when it comes to dose titration;

- Addressing patient concerns — explain to Mary that neuropathic agents may be used as an adjuvant if opiates fail to control the pain [18] ;

- Resources — recommend available online resources to Mary through the British Pain Society and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (see Useful resources) [17] , [19] .

Explain to Mary that as her opiate dose is increased, breakthrough doses will also increase. These should be one-sixth of the total daily opiate dose. For example, a dose of MST 30mg twice daily (60mg/24 hours), will require morphine sulphate (liquid or tablet) 10mg every 2–4 hours as required for breakthrough pain [10] , [14] .

When to refer

Mary should be referred back to her GP or the palliative care team if she requires frequent prescriptions for breakthrough medicines, which would indicate that her pain is not adequately managed, or she is experiencing unacceptable side effects (e.g. nausea or severe itch).

Palliative care part 2: nausea and constipation

Mary returns to the pharmacy ten days after starting on MST and her background dose is currently 30mg twice daily. She says that her pain is controlled, but she has been experienced nausea since the MST dose was increased two days ago. She also explains that she has not had “a proper bowel movement” for five days. Mary says she feels generally uncomfortable and has a feeling of fullness in her abdomen.

As a result, Mary is considering stopping the MST capsules. When questioned on her diet, Mary says she understands that dietary intake influences her bowels; however, she explains that her appetite is reduced owing to the abdominal discomfort. Mary would like to know if there is anything she can purchase that will help.

Constipation is the most commonly reported side effect of opiate treatment (up to 80% of patients) and can result in reduced quality of life and discontinuation of the offending medicine, which could result in a resurgence of pain [10] , [20] . When speaking with Mary about management, consider the following:

- Ascertain bowel pattern — the Bristol Stool chart can be used to support the consultation, but it is important to determine what is ‘normal’ for the patient and any other symptoms (e.g. colic) [21] . Mary confirms that her bowels feel sluggish and she is passing small, hard stools, which requires a lot of effort.;

- Maintaining a healthy diet — Mary’s dietary intake is reduced, but with resolution of constipation, this may improve. Encourage a healthy diet that includes whole grains, fruit and vegetables, and a good fluid intake [22] ;

- Laxatives — regular administration of laxatives to avoid constipation is advised [14] . The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends the use of: stimulant laxatives (e.g. Senna [7.5–15mg at night, increasing to 30mg maximum in 24 hours] and sodium picosulphate [5–10mg at night]) and osmotic laxatives (e.g. lactulose [15–45mL daily in three divided doses] and macrogol compound [1–3 sachets daily in divided doses]) [22] . Docusate (up to 500mg daily in divided doses) is an alternative as both a softener and weak stimulant [10] . If tolerance to constipation does not occur, treatment with laxatives is advised for the duration of opiate use [20] . If titration of laxative is required then this occurs every 1–2 days according to response before switching to an alternative [10] ;

- Nausea — this common side effect occurs on initiation and dose increase, but is normally transient, lasting only a few days [15] , [23] , [24] . If patients are aware of this, they may feel more prepared and willing to accept it for a short period of time making the use of an antiemetic unnecessary [20] ;

- Non-pharmacological measures — pharmacy teams can recommend removal of certain stimuli (e.g. sight and smell of nausea-provoking foods) that lead to nausea and massage to help manage constipation [25] , [26] .

It is important to explain to Mary that opioid analgesics are a common cause of constipation, alongside other contributing factors, such as poor fluid, and dietary intake [27] .

Compliance with laxatives may be limited by patient factors, such as palatability, volume required and undesirable effects (e.g. flatulence and colic). Mary’s preference should be considered, especially as there is limited evidence for the use of laxatives, and management is generally dictated by best practice and expert opinion [14] .

The underlying aetiology of nausea and/or vomiting should be considered; gastric dysmotility and stimulation of the chemoreceptor trigger zone are most common with opiates, and can be managed with prokinetics (e.g. domperidone, metoclopramide) or a D2 receptor antagonist (e.g. haloperidol) [10] , [18] , [19] .

When the maximum licensed dose of laxatives is reached without adequate result, then there is a need to refer the patient.

If an antiemetic is considered necessary (e.g. owing to persistent or intolerable nausea ), the patient requires referral for thorough assessment [25] .

Palliative care part 3: Anticipatory prescribing

Mary’s husband, John*, brings a prescription for anticipatory medicines into the pharmacy. He is visibly upset and asks to speak to the pharmacist. He explains that the GP surgery called and asked for this prescription to be collected following a home visit from Mary’s community nurse.

During the visit, the nurse asked difficult questions about where Mary would like to be cared for when she becomes less well, and whether she would want to be resuscitated. The nurse had also suggested that Mary can stop her simvastatin, which she has been taking for the past 17 years.

John’s concerns

Although John is concerned because he knows Mary is unwell, he thinks these conversations suggest that Mary is nearing the end of her life.

When speaking with John, be empathetic while providing information. For example, explain:

- That anticipatory prescribing is part of advance care planning and does not signify that a patient is imminently dying. Medicines are prescribed in anticipation of symptoms, and should be put in place well in advance to enable rapid symptom relief [13] , [28] ;

- The possible use for each of the medicines (pain, nausea and vomiting, excess respiratory secretions, agitation and restlessness) [29] . It is unlikely that all would be needed, and possibly none at all. These medicines can be used for a more acute symptom, such as nausea or pain owing to infection, rather than only for use in the last few days of life;

- Stopping unnecessary medicines (i.e. those for long-term risk, such as statins for cardiovascular disease) should be considered to reduce tablet burden and potential side effects [7] ;

- These conversation can be distressing, but it provides an opportunity to consider serious issues during a time that is less critical and that some patients and carers may find comfort in the planning [30] .

After speaking with and explaining these points to John he appears to be more content and less worried. It is important to explain to him that the pharmacy team is available to speak to him or his wife if they have any further concerns.

*Case study is fictional

Useful resources

- Local Pharmaceutical Committee: lpc-online.org.uk/

[1] World Health Organization. WHO definition of palliative care. 2019. Available at: https://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ (accessed October 2019)

[2] World Health Organization. Palliative care. 2018. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care (accessed October 2019)

[3] The Gold Standards Framework. PIG – Proactive identification guidance registration form. 2016. Available at: http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/PIG (accessed October 2019)

[4] Marie Curie. Triggers for palliative care. 2015. Available at: https://www.mariecurie.org.uk/globalassets/media/documents/policy/policy-publications/june-2015/triggers-for-palliative-care-full-report.pdf (accessed October 2019)

[5] Moens K, Higginson IJ & Harding R. Are there differences in the prevalence of palliative care-related problems in people living with advanced cancer and eight non-cancer conditions? A systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manag 2014;48(4):660–677. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.11.009

[6] Kobewka D, Ronksley P, McIssac D et al. Prevalence of symptoms at the end of life in an acute care hospital: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ Open 2017;5(1):E222–E228. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20160123

[7] Walker KA, Scarpaci L & McPherson ML. Fifty reasons to love your palliative care pharmacist. American J Hosp Palliat Care 2010;27(8):511–513. doi: 10.1177/1049909110371096

[8] Macmillan Cancer Support. The Final Injustice: variation in end of life care in England. 2017. Available at: https://www.macmillan.org.uk/_images/MAC16904-end-of-life-policy-report_tcm9-321025.pdf (accessed October 2019)

[9] The Gold Standards Framework. Examples of Good Practice Resource Guide. Just in Case Boxes. 2006. Available at: https://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/cd-content/uploads/files/Library%2C%20Tools%20%26%20resources/ExamplesOfGoodPracticeResourceGuideJustInCaseBoxes.pdf (accessed October 2019)

[10] Twycross R, Wilcock A & Howard P. Palliative Care Formulary 6th Ed (PCF6). 2016. Available at: https://about.medicinescomplete.com/publication/palliative-care-formulary (accessed October 2019)

[11] National Palliative and End of Life Care Partnership. Ambitions for palliative and end of life care. 2015. Available at: http://endoflifecareambitions.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Ambitions-for-Palliative-and-End-of-Life-Care.pdf (accessed October 2019)

[12] Gold Standard Framework. Advance Care Planning. 2018. Available at: https://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/advance-care-planning (accessed October 2019)

[13] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Care of dying adults in the last days of life. NICE guideline [NG31]. 2015. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng31 (accessed October 2019)

[14] Royal Pharmaceutical Society. British National Formulary 76 . London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2001

[15] Edwards Z, Blenkinsopp A, Ziegler L & Bennett MI. How do patients with cancer pain view community pharmacy services? An interview study. Health Soc Care Community 2018;26(4):507–518. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12549

[16] World Health Organization. WHO’s cancer pain ladder for adults. 2019. Available at: https://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/painladder/en/ (accessed October 2019)

[17] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Palliative care for adults: strong opioids for pain relief. NICE guideline [CG140] 2016. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg140/ifp/chapter/Managing-side-effects (accessed October 2019)

[18] The British Pain Society. Cancer pain management. 2010. Available at: https://www.britishpainsociety.org/static/uploads/resources/files/book_cancer_pain.pdf (accessed October 2019)

[19] The British Pain Society. Patient publications. Available at: https://www.britishpainsociety.org/british-pain-society-publications/patient-publications/ (accessed October 2019)

[20] Rogers E, Mehta S, Shengelia R, & Carrington Reid M. Four strategies for managing opioid-induced side effects in older adults. Clin Geriatr 2013;21(4). PMID: 25949094

[21] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Clinical knowledge summary. Constipation in adults. 2019. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/constipation#!scenarioRecommendation:1 (accessed October 2019)

[22] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Constipation in children and young people: diagnosis and management. Clinical guideline [CG99]. 2017. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg99/resources/cg99-constipation-in-children-and-young-people-bristol-stool-chart-2 (accessed October 2019)

[23] NHS. Morphine. 2018. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/morphine/# (accessed October 2019)

[24] Cherny N, Ripamonti C, Pereira J et al. Strategies to manage the adverse effects of oral morphine: An evidence-based report. J Clin Oncol 2001;19(9):2542–2554. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.9.2542

[25] Chand S. Nausea and vomiting in palliative care. Pharm J 2014;292(7799)240. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2014.11135047

[26] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Clinical Knowledge Summary. Palliative care — nausea and vomiting. 2016. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/palliative-care-nausea-and-vomiting (accessed October 2019)

[27] Watson M, Lucas C, Hoy A & Back I. Oxford Handbook of Palliative Care. Oxford University Press; 2005.

[28] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Care of dying adults in the last days of life. Quality standard [QS144]. 2017. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs144 (accessed October 2019)

[29] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Medicines guidance: prescribing in palliative care. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/guidance/prescribing-in-palliative-care.html (accessed October 2019)

[30] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). End of life care for adults. 2017. Quality Standard [QS13]. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs13 (accessed October 2019)

You might also be interested in…

PJ view: Restore pharmacy opening hours to improve end-of-life care

Controlled drug stock licensing is working against high-quality palliative care for care home patients

How palliative care pharmacists in community practice are improving access to medicines

5 case studies: When is it time for palliative care versus hospice?

Never hesitate to say “I need help” if you’re struggling to cope with the pain and distress of a life-limiting illness. Hospice and palliative care providers are specially trained to hear your plea and will offer comfort, compassion and support.

“Just because you ask to speak with a palliative care or hospice care provider doesn’t mean you have to start service,” says Lisa Wasson, RN, clinical educator for HopeHealth.

Palliative care and hospice care are two different sets of services, although you might hear people use the terms interchangeably.

- Palliative care is for patients with a serious illness who are still receiving curative treatments, such as chemotherapy or dialysis. Palliative care providers offer medical relief from the symptoms or stress caused by either the illness itself or the treatment. They also help patients understand their options and establish goals of care.

- Hospice care is for patients with a life-limiting illness who have decided to stop curative treatments or have been given no further treatment options for cure or to prolong life. A full team of doctors, nurses, social workers, spiritual chaplains, hospice aides, grief support professionals and volunteers offer comfort and support to the patient and family.

To learn more about these differences, read The ABC’s of curative, palliative and hospice care .

5 case studies: Is palliative care or hospice care more appropriate?

Below are five fictional stories to give you a sense of when it could be helpful to ask for a palliative care or hospice care consultation. (Every medical case is unique, and only your health care provider can advise on your care.)

Case 1: An 86-year-old with Alzheimer’s disease is repeatedly hospitalized

Janet was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease nine years ago and lives at home in the care of her husband. She cannot make her needs known, is incontinent and depends on her husband to feed her. She has lost 20 pounds in six months and been hospitalized three times.

Palliative care or hospice? Janet would likely qualify for hospice care given how far along her disease has advanced.

Case 2: A man wishes to stop dialysis despite family’s wishes

Robert is 64 years old and has kidney failure, coronary artery disease and diabetes. He receives dialysis three times per week but wants to stop treatment. Today he was hospitalized after skipping two dialysis appointments. Robert’s family is concerned he is giving up, and they don’t know what to do.

Palliative care or hospice? Robert and his family need to get on the same page regarding his options and wishes. A good first step would be to ask a palliative care provider to guide that conversation with skill and sensitivity. Ultimately, Robert does have to the right to stop dialysis and choose hospice if he wishes.

“We deserve as much beauty, care and respect from the health care system at the end of life as we receive at the beginning when we are born” —Lisa Wasson, RN, CHPN

Case 3: A 30-year-old with breast cancer and her mother need support

Imani has undergone two rounds of chemotherapy and radiation for breast cancer. She has severe nausea and is losing weight due to poor appetite. Her mother, who works full time, is her primary caregiver.

Palliative care or hospice? Imani is actively fighting her disease with curative treatment and might qualify for palliative care. She would receive symptom management, support services to help her mother, and a conversation about her goals of care.

Case 4: A woman with autoimmune disorders battles depression

Cindy, age 52, has multiple autoimmune disorders, fibromyalgia pain and depression. She takes antidepressant medication, is self-isolating and cannot hold a job due to taking too many sick days.

Palliative care or hospice? Cindy is not a candidate for either palliative care or hospice care because she does not have a life-limiting disease. She still needs support, though, and would be referred to a case manager or social worker.

Case 5: A man with advanced ALS requests a do-not-resuscitate order

Carter has ALS, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a progressive neurodegenerative disease. He has been hospitalized with infection five times and is on a ventilator. Carter is alert and told doctors he wants to return home and sign a do-not-resuscitate order (DNR). His family is upset about his decision.

Palliative care or hospice? While in the hospital, Carter can request to speak with a palliative care or hospice care provider to guide this sensitive conversation with his family. If he wishes to start hospice, a team will help him return home, tend to life-closure tasks and die in peace and comfort surrounded by his family.

Lisa Wasson hopes more patients and their families will seek to understand the benefits of hospice and palliative care. “We deserve as much beauty, care and respect from the health care system at the end of life as we receive at the beginning when we are born,” she says.

Questions about hospice care or palliative care? Contact us at (844) 671-HOPE or [email protected] .

Privacy overview.

- Open access

- Published: 22 October 2022

Stories of paediatric palliative care: a qualitative study exploring health care professionals’ understanding of the concept

- Kirsti Riiser 1 ,

- Heidi Holmen 2 ,

- Anette Winger 2 ,

- Simen A. Steindal 3 ,

- Charlotte Castor 4 ,

- Lisbeth Gravdal Kvarme 2 ,

- Anja Lee 5 ,

- Vibeke Bruun Lorentsen 6 ,

- Nina Misvaer 2 &

- Elena Albertini Früh 2

BMC Palliative Care volume 21 , Article number: 187 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

4464 Accesses

1 Citations

10 Altmetric

Metrics details

By sharing patient stories, health care professionals (HCPs) may communicate their attitudes, values and beliefs about caring and treatment. Previous qualitative research has shown that HCPs usually associate paediatric palliative care (PPC) with death or dying and that they find the concept challenging to understand and difficult to implement. Attending to HCPs’ stories may provide a richer account of their understanding of PPC. Thus, the aim of this study was to explore PPC stories narrated by HCPs to gain increased insight into their understanding of what PPC entails.

This qualitative study collected data from four focus group interviews with 21 HCPs from different units in two Norwegian hospitals. Stories told by the HCPs to illustrate their comprehension of PPC were analysed following thematic analysis procedures.

Four themes were identified illustrating what PPC meant to the participants: creating spaces for normality, providing tailored support for the family, careful preparations for saying goodbye and experiencing dilemmas and distress. The stories centred on family care, particularly relating to dramatic or affective situations when the death of a child was imminent.

The stories reflect how the HCPs view PPC as a specific field of health care that requires particular professional sensitivity, including good communication, collaboration and planning. Thus, the HCPs in this study demonstrated knowledge about the core qualities needed to succeed in PPC. However, similar to previous research, the stories illustrate that how HCPs speak about PPC is strongly associated with end-of-life care, and by that the HCPs do not capture the breadth of the PPC concept. The findings highlight the importance of increasing knowledge about the meaning and content of PPC among HCPs in order to maintain quality of life for all children with life-limiting or life-threatening conditions throughout their illness trajectory.

Peer Review reports

Storytelling is a fundamental part of being human. Through stories information can be shared in a way that creates an emotional connection and by that provides a deeper understanding of the storyteller’s experiences. Thus, storytelling has the potential to bring new perspectives to the Table [ 1 ]. When telling stories about specific events from patients´ lives, health care professionals (HCPs) not only describe the patients’ medical situations. By sharing patient stories, HCPs also communicate their attitudes, values and beliefs about caring and treatment [ 2 ]. The present study used storytelling as a methodological approach to investigate HCPs’ understanding of paediatric palliative care (PPC). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), PPC should be the standard of care for children with life-threatening or life-limiting conditions and should be integrated with prevention, early diagnosis and treatment [ 3 , 4 ]. PPC is defined as “the active total care of the child’s body, mind and spirit, and [this] also involves giving support to the family” [ 5 ]. Children (0–18 years) and their families should be provided with interdisciplinary care aiming to promote their physical, psychological, social and spiritual well-being [ 4 ]. Early implementation of PPC through active and integrated support is endorsed as beneficial to the well-being of the child and the family [ 3 , 6 , 7 ]. HCPs may display good knowledge of the principles of palliative care, but their comprehension of the concept, their way of thinking and their reported reasons for referrals to PPC demonstrate that they associate PPC with death and dying [ 8 , 9 ]. Research reports that HCPs find the concept challenging to understand and implement and that it evokes negative emotions [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Consequently, early integration of PPC may be delayed and many children are not referred to PPC until late in their illness trajectory [ 12 ]. Among the barriers reported for implementing PPC at an early stage are uncertainty and confusion about the concept, as well as stigma related to the term [ 10 , 13 ]. In our recent study of interdisciplinary HCPs’ understanding and implementation of PPC, we found that the participants viewed the concept as unfamiliar and not meaningful [ 11 ]. HCPs associated PPC with death and dying and used words like scary, burdensome, dramatic and lack of active treatment to describe their comprehension of the concept [ 11 ].

Attending to stories of HCPs´ clinical experience with children and their families may provide further insights than solely through answering questions and thus be a valuable approach to gain an even richer account of their understanding of PPC. Thus, the aim of this study was to explore stories of PPC narrated by HCPs to enhance our knowledge of their understanding of what PPC entails.