Here's how COVID-19 affected education – and how we can get children’s learning back on track

Nearly 147 million children missed more than half of their in-person schooling between 2020 and 2022. Image: Unsplash/Taylor Flowe

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Douglas Broom

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Global Health is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, global health.

Listen to the article

- As well as its health impacts, COVID-19 had a huge effect on the education of children – but the full scale is only just starting to emerge.

- As pandemic lockdowns continue to shut schools, it’s clear the most vulnerable have suffered the most.

- Recovering the months of lost education must be a priority for all nations.

When the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 to be a pandemic on 11 March 2020, few could have foreseen the catastrophic effects the virus would have on the education of the world’s children.

During the first 12 months of the pandemic, lockdowns led to 1.5 billion students in 188 countries being unable to attend school in person, causing lasting effects on the education of an entire generation .

As an OECD report into the effects of school closures in 2021 put it: “Few groups are less vulnerable to the coronavirus than school children, but few groups have been more affected by the policy responses to contain the virus.”

Although many school closures were announced as temporary measures, these shutdowns persisted throughout 2020 – and even beyond in some cases.

As late as March 2022, UNICEF reported that 23 countries, home to around 405 million schoolchildren, had not yet fully reopened their schools . As China battled to contain new COVID-19 outbreaks, schools were closed in Shanghai and Xian in October 2022.

COVID has ended education for some

Nearly 147 million children missed more than half of their in-person schooling between 2020 and 2022, UNICEF says. And it warns that many, especially the most vulnerable, are at risk of dropping out of education altogether.

The danger is highlighted by UNICEF data showing that 43% of students did not return when schools in Liberia reopened in December 2020. The number of out-of-school children in South Africa tripled from 250,000 to 750,000 between March 2020 and July 2021, UNICEF adds.

When schools in Uganda reopened after being closed for two years, almost one in ten children were missing from classrooms. And in Malawi, the dropout rate among girls in secondary education increased by 48% between 2020 and 2021.

Out-of-school children are among the most vulnerable and marginalized children in society, says UNICEF. They are the least likely to be able to read, write or do basic maths, and when not in school they are at risk of exploitation and a lifetime of poverty and deprivation, it says.

Lost learning time

Even when children are in school, the amount of learning time they have lost to the pandemic is compounding what UNICEF describes as “a desperately poor level of learning” in 32 low-income countries it has studied.

“In the countries analyzed, the current pace of learning is so slow that it would take seven years for most schoolchildren to learn foundational reading skills that should have been grasped in two years, and 11 years to learn foundational numeracy skills,” the charity says.

Analysis of the crisis by UNESCO, published in November 2022, found that the most vulnerable learners have been hardest hit by the lack of schooling. It added that progress towards the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal for Education had been set back.

In Latin America and the Caribbean – a region that suffered one of the longest periods of school closures – average primary education scores in reading and maths could have slipped back to a level last seen 10 years ago , the World Bank says.

Four out of five sixth graders may not be able to adequately understand and interpret a text of moderate length, the bank says. As a result, these students are likely to earn 12% less over their lifetime than if their education had not been curtailed by the pandemic, it estimates.

Widening the achievement gap

In India, the pandemic has widened the gaps in learning outcomes among schoolchildren with those from disenfranchised and vulnerable families falling furthest behind, according to a 2022 report by the World Economic Forum.

Even where schools tried to keep teaching using remote learning, the socio-economic divide was perpetuated. In the United States, a study found children’s achievement in maths fell by 50% more in less well-off areas , compared to those in more affluent neighbourhoods.

One year on: we look back at how the Forum’s networks have navigated the global response to COVID-19.

Using a multistakeholder approach, the Forum and its partners through its COVID Action Platform have provided countless solutions to navigate the COVID-19 pandemic worldwide, protecting lives and livelihoods.

Throughout 2020, along with launching its COVID Action Platform , the Forum and its Partners launched more than 40 initiatives in response to the pandemic.

The work continues. As one example, the COVID Response Alliance for Social Entrepreneurs is supporting 90,000 social entrepreneurs, with an impact on 1.4 billion people, working to serve the needs of excluded, marginalized and vulnerable groups in more than 190 countries.

Read more about the COVID-19 Tools Accelerator, our support of GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance, the Coalition for Epidemics Preparedness and Innovations (CEPI), and the COVAX initiative and innovative approaches to solve the pandemic, like our Common Trust Network – aiming to help roll out a “digital passport” in our Impact Story .

Consultancy firm McKinsey says that US students were on average five months behind in mathematics and four months behind in reading by the end of the 2020-21 school year. Disadvantaged students were hit hardest, with Black students losing six months of learning on average.

Researchers in Japan found a similar pattern, with disadvantaged children and the youngest suffering most from school closures. They said the adverse effects of being forced to study at home lasted longest for those with poorest living conditions .

However, in Sweden, where schools stayed open during the pandemic, there was no decline in reading comprehension scores among children from all socio-economic groups, leading researchers to conclude that the shock of the pandemic alone did not affect students’ performance.

Getting learning back on track

So what can be done to help the pandemic generation to recover their lost learning ?

The World Bank outlines 10 actions countries can take, including getting schools to assess students’ learning loss and monitor their progress once they are back at school.

Catch-up education and measures to ensure that children don’t drop out of school will be essential, it says. These could include changing the school calendar, and amending the curriculum to focus on foundational skills.

There’s also a need to enhance learning opportunities at home, such as by distributing books and digital devices if possible. Supporting parents in this role is also critical, the bank says.

Teachers will also need extra help to avoid burnout, the bank notes. It highlights a “need to invest aggressively in teachers’ professional development and use technology to enhance their work”.

Have you read?

Covid-19 has hit children hard. here's how schools can help, how the education sector should respond to covid-19, according to these leading experts, covid created an education crisis that has pushed millions of children into ‘learning poverty’ -report, don't miss any update on this topic.

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Global Health .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Protecting employees against tuberculosis is a shot in the arm for sustainable business. Here's why

Richard C Adkerson, René Nijhof, Makoto Inoue and Benoît de la Fouchardiere

March 21, 2024

Why obesity is rising and how we can live healthy lives

Shyam Bishen

March 20, 2024

Harvard scientists have created a new antibiotic that kills superbugs

Microplastics linked to greater risk of heart attack and stroke, plus other top health stories

March 14, 2024

8 global leaders share how we can close the women’s health gap

Dhwani Nagpal

March 8, 2024

African nations have agreed a plan to increase locally produced vaccines. This is how it will work

Simon Torkington

March 7, 2024

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Top issues for young voters? Stories from a swing state.

Why are we so divided? Zero-sum thinking is part of it.

It may be neither higher nor intelligence

Rubén Rodriguez/Unsplash

Time to fix American education with race-for-space resolve

Harvard Staff Writer

Paul Reville says COVID-19 school closures have turned a spotlight on inequities and other shortcomings

This is part of our Coronavirus Update series in which Harvard specialists in epidemiology, infectious disease, economics, politics, and other disciplines offer insights into what the latest developments in the COVID-19 outbreak may bring.

As former secretary of education for Massachusetts, Paul Reville is keenly aware of the financial and resource disparities between districts, schools, and individual students. The school closings due to coronavirus concerns have turned a spotlight on those problems and how they contribute to educational and income inequality in the nation. The Gazette talked to Reville, the Francis Keppel Professor of Practice of Educational Policy and Administration at Harvard Graduate School of Education , about the effects of the pandemic on schools and how the experience may inspire an overhaul of the American education system.

Paul Reville

GAZETTE: Schools around the country have closed due to the coronavirus pandemic. Do these massive school closures have any precedent in the history of the United States?

REVILLE: We’ve certainly had school closures in particular jurisdictions after a natural disaster, like in New Orleans after the hurricane. But on this scale? No, certainly not in my lifetime. There were substantial closings in many places during the 1918 Spanish Flu, some as long as four months, but not as widespread as those we’re seeing today. We’re in uncharted territory.

GAZETTE: What lessons did school districts around the country learn from school closures in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, and other similar school closings?

REVILLE: I think the lessons we’ve learned are that it’s good [for school districts] to have a backup system, if they can afford it. I was talking recently with folks in a district in New Hampshire where, because of all the snow days they have in the wintertime, they had already developed a backup online learning system. That made the transition, in this period of school closure, a relatively easy one for them to undertake. They moved seamlessly to online instruction.

Most of our big systems don’t have this sort of backup. Now, however, we’re not only going to have to construct a backup to get through this crisis, but we’re going to have to develop new, permanent systems, redesigned to meet the needs which have been so glaringly exposed in this crisis. For example, we have always had large gaps in students’ learning opportunities after school, weekends, and in the summer. Disadvantaged students suffer the consequences of those gaps more than affluent children, who typically have lots of opportunities to fill in those gaps. I’m hoping that we can learn some things through this crisis about online delivery of not only instruction, but an array of opportunities for learning and support. In this way, we can make the most of the crisis to help redesign better systems of education and child development.

GAZETTE: Is that one of the silver linings of this public health crisis?

REVILLE: In politics we say, “Never lose the opportunity of a crisis.” And in this situation, we don’t simply want to frantically struggle to restore the status quo because the status quo wasn’t operating at an effective level and certainly wasn’t serving all of our children fairly. There are things we can learn in the messiness of adapting through this crisis, which has revealed profound disparities in children’s access to support and opportunities. We should be asking: How do we make our school, education, and child-development systems more individually responsive to the needs of our students? Why not construct a system that meets children where they are and gives them what they need inside and outside of school in order to be successful? Let’s take this opportunity to end the “one size fits all” factory model of education.

GAZETTE: How seriously are students going to be set back by not having formal instruction for at least two months, if not more?

“The best that can come of this is a new paradigm shift in terms of the way in which we look at education, because children’s well-being and success depend on more than just schooling,” Paul Reville said of the current situation. “We need to look holistically, at the entirety of children’s lives.”

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

REVILLE: The first thing to consider is that it’s going to be a variable effect. We tend to regard our school systems uniformly, but actually schools are widely different in their operations and impact on children, just as our students themselves are very different from one another. Children come from very different backgrounds and have very different resources, opportunities, and support outside of school. Now that their entire learning lives, as well as their actual physical lives, are outside of school, those differences and disparities come into vivid view. Some students will be fine during this crisis because they’ll have high-quality learning opportunities, whether it’s formal schooling or informal homeschooling of some kind coupled with various enrichment opportunities. Conversely, other students won’t have access to anything of quality, and as a result will be at an enormous disadvantage. Generally speaking, the most economically challenged in our society will be the most vulnerable in this crisis, and the most advantaged are most likely to survive it without losing too much ground.

GAZETTE: Schools in Massachusetts are closed until May 4. Some people are saying they should remain closed through the end of the school year. What’s your take on this?

REVILLE: That should be a medically based judgment call that will be best made several weeks from now. If there’s evidence to suggest that students and teachers can safely return to school, then I’d say by all means. However, that seems unlikely.

GAZETTE: The digital divide between students has become apparent as schools have increasingly turned to online instruction. What can school systems do to address that gap?

REVILLE: Arguably, this is something that schools should have been doing a long time ago, opening up the whole frontier of out-of-school learning by virtue of making sure that all students have access to the technology and the internet they need in order to be connected in out-of-school hours. Students in certain school districts don’t have those affordances right now because often the school districts don’t have the budget to do this, but federal, state, and local taxpayers are starting to see the imperative for coming together to meet this need.

Twenty-first century learning absolutely requires technology and internet. We can’t leave this to chance or the accident of birth. All of our children should have the technology they need to learn outside of school. Some communities can take it for granted that their children will have such tools. Others who have been unable to afford to level the playing field are now finding ways to step up. Boston, for example, has bought 20,000 Chromebooks and is creating hotspots around the city where children and families can go to get internet access. That’s a great start but, in the long run, I think we can do better than that. At the same time, many communities still need help just to do what Boston has done for its students.

Communities and school districts are going to have to adapt to get students on a level playing field. Otherwise, many students will continue to be at a huge disadvantage. We can see this playing out now as our lower-income and more heterogeneous school districts struggle over whether to proceed with online instruction when not everyone can access it. Shutting down should not be an option. We have to find some middle ground, and that means the state and local school districts are going to have to act urgently and nimbly to fill in the gaps in technology and internet access.

GAZETTE : What can parents can do to help with the homeschooling of their children in the current crisis?

“In this situation, we don’t simply want to frantically struggle to restore the status quo because the status quo wasn’t operating at an effective level and certainly wasn’t serving all of our children fairly.”

More like this

The collective effort

Notes from the new normal

‘If you remain mostly upright, you are doing it well enough’

REVILLE: School districts can be helpful by giving parents guidance about how to constructively use this time. The default in our education system is now homeschooling. Virtually all parents are doing some form of homeschooling, whether they want to or not. And the question is: What resources, support, or capacity do they have to do homeschooling effectively? A lot of parents are struggling with that.

And again, we have widely variable capacity in our families and school systems. Some families have parents home all day, while other parents have to go to work. Some school systems are doing online classes all day long, and the students are fully engaged and have lots of homework, and the parents don’t need to do much. In other cases, there is virtually nothing going on at the school level, and everything falls to the parents. In the meantime, lots of organizations are springing up, offering different kinds of resources such as handbooks and curriculum outlines, while many school systems are coming up with guidance documents to help parents create a positive learning environment in their homes by engaging children in challenging activities so they keep learning.

There are lots of creative things that can be done at home. But the challenge, of course, for parents is that they are contending with working from home, and in other cases, having to leave home to do their jobs. We have to be aware that families are facing myriad challenges right now. If we’re not careful, we risk overloading families. We have to strike a balance between what children need and what families can do, and how you maintain some kind of work-life balance in the home environment. Finally, we must recognize the equity issues in the forced overreliance on homeschooling so that we avoid further disadvantaging the already disadvantaged.

GAZETTE: What has been the biggest surprise for you thus far?

REVILLE: One that’s most striking to me is that because schools are closed, parents and the general public have become more aware than at any time in my memory of the inequities in children’s lives outside of school. Suddenly we see front-page coverage about food deficits, inadequate access to health and mental health, problems with housing stability, and access to educational technology and internet. Those of us in education know these problems have existed forever. What has happened is like a giant tidal wave that came and sucked the water off the ocean floor, revealing all these uncomfortable realities that had been beneath the water from time immemorial. This newfound public awareness of pervasive inequities, I hope, will create a sense of urgency in the public domain. We need to correct for these inequities in order for education to realize its ambitious goals. We need to redesign our systems of child development and education. The most obvious place to start for schools is working on equitable access to educational technology as a way to close the digital-learning gap.

GAZETTE: You’ve talked about some concrete changes that should be considered to level the playing field. But should we be thinking broadly about education in some new way?

REVILLE: The best that can come of this is a new paradigm shift in terms of the way in which we look at education, because children’s well-being and success depend on more than just schooling. We need to look holistically, at the entirety of children’s lives. In order for children to come to school ready to learn, they need a wide array of essential supports and opportunities outside of school. And we haven’t done a very good job of providing these. These education prerequisites go far beyond the purview of school systems, but rather are the responsibility of communities and society at large. In order to learn, children need equal access to health care, food, clean water, stable housing, and out-of-school enrichment opportunities, to name just a few preconditions. We have to reconceptualize the whole job of child development and education, and construct systems that meet children where they are and give them what they need, both inside and outside of school, in order for all of them to have a genuine opportunity to be successful.

Within this coronavirus crisis there is an opportunity to reshape American education. The only precedent in our field was when the Sputnik went up in 1957, and suddenly, Americans became very worried that their educational system wasn’t competitive with that of the Soviet Union. We felt vulnerable, like our defenses were down, like a nation at risk. And we decided to dramatically boost the involvement of the federal government in schooling and to increase and improve our scientific curriculum. We decided to look at education as an important factor in human capital development in this country. Again, in 1983, the report “Nation at Risk” warned of a similar risk: Our education system wasn’t up to the demands of a high-skills/high-knowledge economy.

We tried with our education reforms to build a 21st-century education system, but the results of that movement have been modest. We are still a nation at risk. We need another paradigm shift, where we look at our goals and aspirations for education, which are summed up in phrases like “No Child Left Behind,” “Every Student Succeeds,” and “All Means All,” and figure out how to build a system that has the capacity to deliver on that promise of equity and excellence in education for all of our students, and all means all. We’ve got that opportunity now. I hope we don’t fail to take advantage of it in a misguided rush to restore the status quo.

This interview has been condensed and edited for length and clarity.

Share this article

You might like.

Harvard student pollsters talk to peers in Michigan about money, mental health, and other worries

Researchers examine who embraces mindset that one’s gain is another’s loss, and how that affects our politics — in sometimes surprising ways

Religious scholars examine value, limits of AI

Maria Ressa named 2024 Commencement speaker

Nobel Prize-winning defender of press freedom will deliver principal address

So what exactly makes Taylor Swift so great?

Experts weigh in on pop superstar's cultural and financial impact as her tours and albums continue to break records.

The 20-minute workout

Pressed for time? You still have plenty of options.

Read our research on: TikTok | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

Most k-12 parents say first year of pandemic had a negative effect on their children’s education.

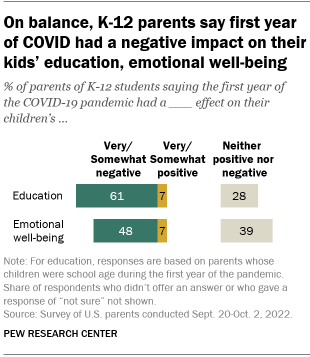

Recent findings from the National Assessment of Educational Progress add to mounting evidence that the transition to remote learning in the early stages of the coronavirus pandemic created gaps in learning that had a lasting impact on K-12 students in the United States. These findings are echoed in the views of many K-12 parents: About six-in-ten (61%) say the first year of the pandemic had a negative effect on their children’s education. Just 7% say it had a positive effect, while 28% say it had neither a positive nor negative effect.

Among parents who say the pandemic had a negative effect on their children’s education, more than four-in-ten (44%) say this is still the case today, while 56% say the impact was only temporary, according to a new Pew Research Center survey of U.S. parents.

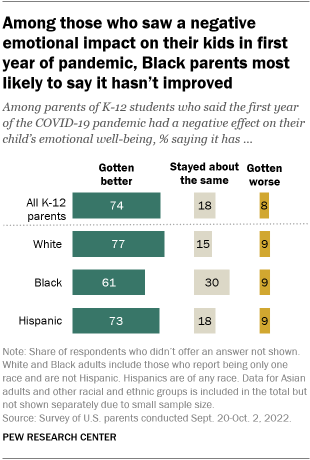

The early stages of the pandemic also presented emotional challenges for children and teens . About half of parents (48%) say that the first year of the pandemic had a negative effect on their children’s emotional well-being, while 7% say it had a positive effect and 39% say the impact was neither positive nor negative. Among parents who say there was a negative impact in the first year, most (74%) say their children’s emotional well-being has gotten better, while 8% say it’s gotten worse and 18% say things have stayed about the same.

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to study how parents of K-12 students assess the impact the COVID-19 pandemic has had on their children’s education and emotional well-being. To do this, we surveyed 3,757 U.S. parents with at least one child younger than 18 (including 3,251 who have a child in a K-12 school) from Sept. 20 to Oct. 2, 2022. Because parents with multiple children in K-12 schools may have different answers to these questions depending on the child or the school they attend, these parents were randomly assigned to think about their youngest or oldest child who is in K-12 when answering these questions. The data was weighted to account for the probability of being assigned to a child in elementary, middle or high school and is representative of all parents of students at each of these stages.

Most parents who took part are members of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This survey also included an oversample of Black, Hispanic and Asian parents from Ipsos’ KnowledgePanel, another probability-based online survey web panel recruited primarily through national, random sampling of residential addresses.

Address-based sampling ensures that nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Here are the questions used for this analysis, along with responses, and its methodology .

Related: Parents Differ Sharply by Party Over What Their K-12 Children Should Learn in School

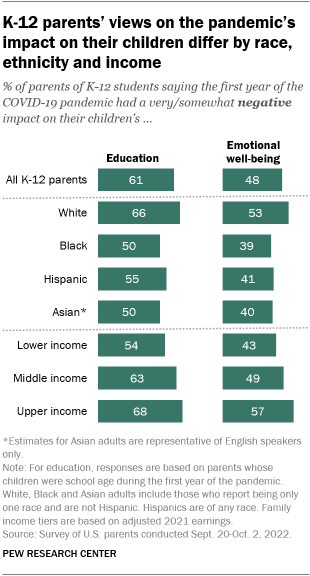

Parents’ views on the effect of the first year of the pandemic on their children’s education differ significantly by race and ethnicity. While studies show that learning loss was more severe for Black and Hispanic students, White parents (66%) are more likely than Black (50%), Hispanic (55%) and Asian parents (50%) to say that the first year of the pandemic had a negative impact on their children’s education.

Income is another factor: A greater share of upper-income parents (68%) say their children’s education was negatively affected, compared with middle- and lower-income parents (63% and 54%, respectively).

The patterns are similar when it comes to the impact of the pandemic on children’s emotional well-being. White parents (53%) are more likely than Black (39%), Hispanic (41%) and Asian parents (40%) to say the first year of the pandemic had a negative effect on their children’s emotional well-being. And a higher share of upper-income parents (57%) than middle- or lower-income parents say the same (49% and 43%, respectively).

Parents’ views on the emotional impact of the first year of the pandemic also differ by the age of their children. Parents of high school and middle school students (57% and 50%, respectively) are more likely than parents of elementary school students (43%) to say the emotional effect was negative.

When asked whether the effects of the first year of the pandemic are still a factor for their children today, the results are mixed. Among parents who say the first year of the pandemic had a negative impact on their children’s education, a majority (56%) say the negative effect was only temporary. Still, 44% say it is still having an effect today.

These assessments don’t differ substantially across key demographic groups, but there are differences by the type of school children attend. Parents who were answering about a child in a public school were more likely than those answering about a child in a private school to say there is still a negative effect on their child’s education today (45% vs. 36%).

When it comes to the emotional impact of the pandemic, most parents who say there was a negative effect in the first year say things are better now (74%). But these attitudes differ by race and ethnicity.

Among parents who say the first year of the pandemic had a negative effect, White (77%) and Hispanic parents (73%) are more likely than Black parents (61%) to say their children’s emotional well-being has gotten better. Roughly four-in-ten Black parents say the negative effects of the first year of the pandemic have persisted or gotten worse. This compares with about a quarter of White and Hispanic parents. (There are too few Asian parents to analyze separately on this question.)

Upper-income parents who say the first year of the pandemic had a negative effect on their children’s emotional well-being are more likely than middle- or lower-income parents to say their children are doing better now in this regard (81% vs. 73% and 70%, respectively).

Note: Here are the questions used for this analysis, along with responses, and its methodology .

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivered Saturday mornings

Parents Differ Sharply by Party Over What Their K-12 Children Should Learn in School

About a third of k-12 parents are very or extremely worried a shooting could happen at their children’s school, partisans tend to cite different ideas for what more the government should do for parents and children, americans’ complex views on gender identity and transgender issues, how teens navigate school during covid-19, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

The Impact of Covid-19 Pandemic on Education

by Hang Nguyen | Aug 6, 2020 | eLearning

The outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic has affected all aspects of human activities including education. It poses serious concerns to education systems such as learning disruptions and decreased access to education facilities. Besides, the pandemic has also facilitated the creation of innovative teaching methods that may reshape the future of education in the 21 st century. This blog will cover the impact of Covid-19 pandemic on education and how we are dealing with it.

Photo by Julia M Cameron from Pexels

How has the Covid-19 Pandemic Affected Education?

According to UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) , the Covid-19 has resulted in closures of schools in more than 100 countries worldwide, impacting over 1,1 billion learners out of the classroom, accounting for 67.6% of total enrolled learners.

Across the globe, educational disruptions can have long term implications, especially for the vulnerable. When schools shut, children from lower-income households who rely on school-based nutrition programs will lose access to school meals. We don’t know how long the pandemic can last. But this will cause psychological and physical harm to children even if the food insecurity happens for a short time. Moreover, nutrition shortfalls can also cause financial burdens on those families as the true cost to families of feeding children is high.

Due to the coronavirus outbreak, many countries have decided to cancel or postpone the upcoming semester or final exams. Standardized tests widely used for college admissions in the United States such as A-Level, SAT, and IB have been canceled, either.

Even when schools reopen, economic depression may increase inequality and constrain expanding access to education. It’s the government’s responsibility to bridge the gap of equality and not let the vulnerable be left behind.

How do Teachers and Students Overcome this Situation?

The impact of Covid-19 pandemic on education quite serious. Within a few months since the outbreak of the pandemic, the lifestyle of the entire world has been changed thoroughly. Billions of people are forced to “stay at home”. Most schools and educators are looking for solutions to continue teaching during this coronavirus pandemic. In fact, not all students have access to the Internet and digital devices. Therefore, establishing effective forms of online education will grant access to institutional resources. This will help students who have fewer opportunities to be able to access alternative learning methods. The resources are divided into three main categories, namely Curriculums Resources, Professional Development Resources, and Tools.

Curriculums Resources

These include lessons, videos, interactive learning modules, and any other resources that directly support students in acquiring knowledge and skills.

Professional Development Resources

These are resources that can help teachers or parents in supporting learners, guiding them to content, developing their skills to teach remotely, or more generally augmenting their capacity to support learners now learning more independently and at home, rather than at school.

These include tools that can help manage teaching and learning. They are communication tools, learning management systems (LMS), or other tools that help to create educational content. These tools have also led to changes in the ways of teaching and learning in this Covid-19 pandemic. For example, with a communication tool, teachers are able to keep in touch with their students more efficiently through chat groups or video meetings. Whilst, ActivePresenter seems to be the most comprehensive tool for creating education content as teachers can design, edit, export, and publish courses to an LMS right in the software without using any plug-ins or external applications. Learners then can easily access and interact with the course content on any device having internet access.

Educational Challenges and Opportunities

The Covid-19 epidemic poses both challenges and opportunities for education worldwide. Starting the school year late and losing access to facilities completely disrupt many students’ lives, especially to those who are involved in physical activities or sports. Though it’s just a temporary replacement, exercising at home without any equipment and limited space can still be possible. These activities can be stretching, climbing stairs, dancing to music, or even doing the housework.

Switching from traditional learning to online learning may be the most effective way to reduce educational disruptions during this pandemic. However, if we do not act appropriately, it will increase the equality gaps. Many children do not have internet connectivity or a laptop at home, others do. Fortunately, the appropriate strategy in many countries is to use all possible infrastructure. Postcards and other recourses that require less data usage such as content delivered by radio or TV are also available.

The impact of Covid-19 pandemic on education systems is adverse all over the world. The quarantine and school closures across the world may be inconvenient, but it’s necessary to contain the spread of the virus. Also, this is an opportunity for education systems to adopt technology and appropriate teaching methods to adapt to the current situation. With online learning trends emerging in many parts of the world, some people are wondering if it will continue to persist post-pandemic and how it would impact on the education systems worldwide.

- eLearning (195)

- Saola Animate 2 (52)

- Saola Animate 3 (57)

- Screencasting (47)

- eLearning (Vietnamese) (72)

- Hướng dẫn sử dụng (14)

- ActivePresenter 7 (133)

- ActivePresenter 8 (157)

- ActivePresenter 9 (162)

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Science and Technology Directorate

Feature Article: Here’s What We’ve Learned About COVID-19

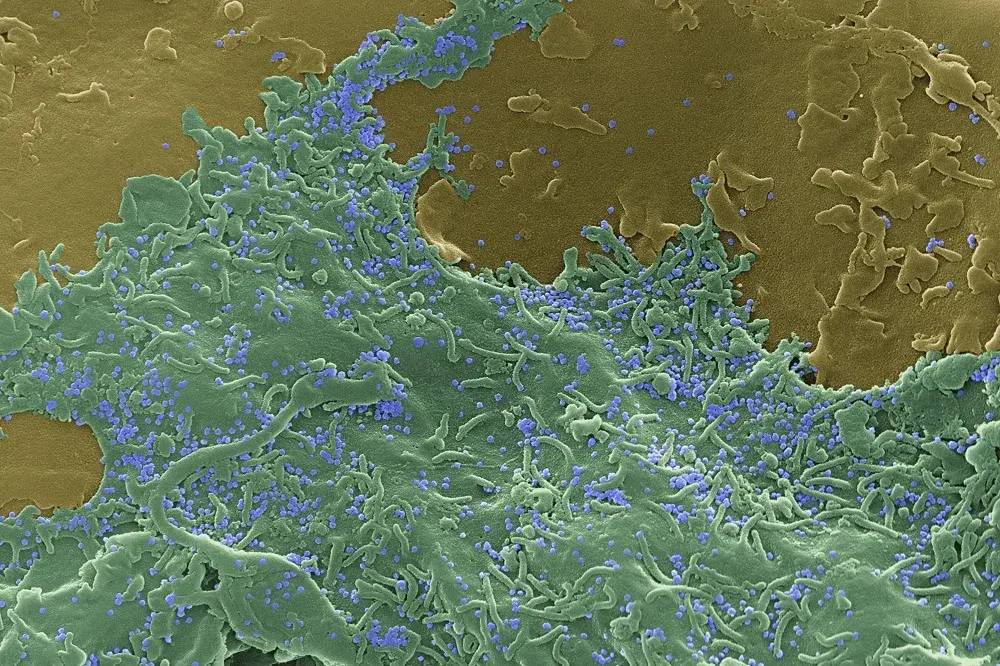

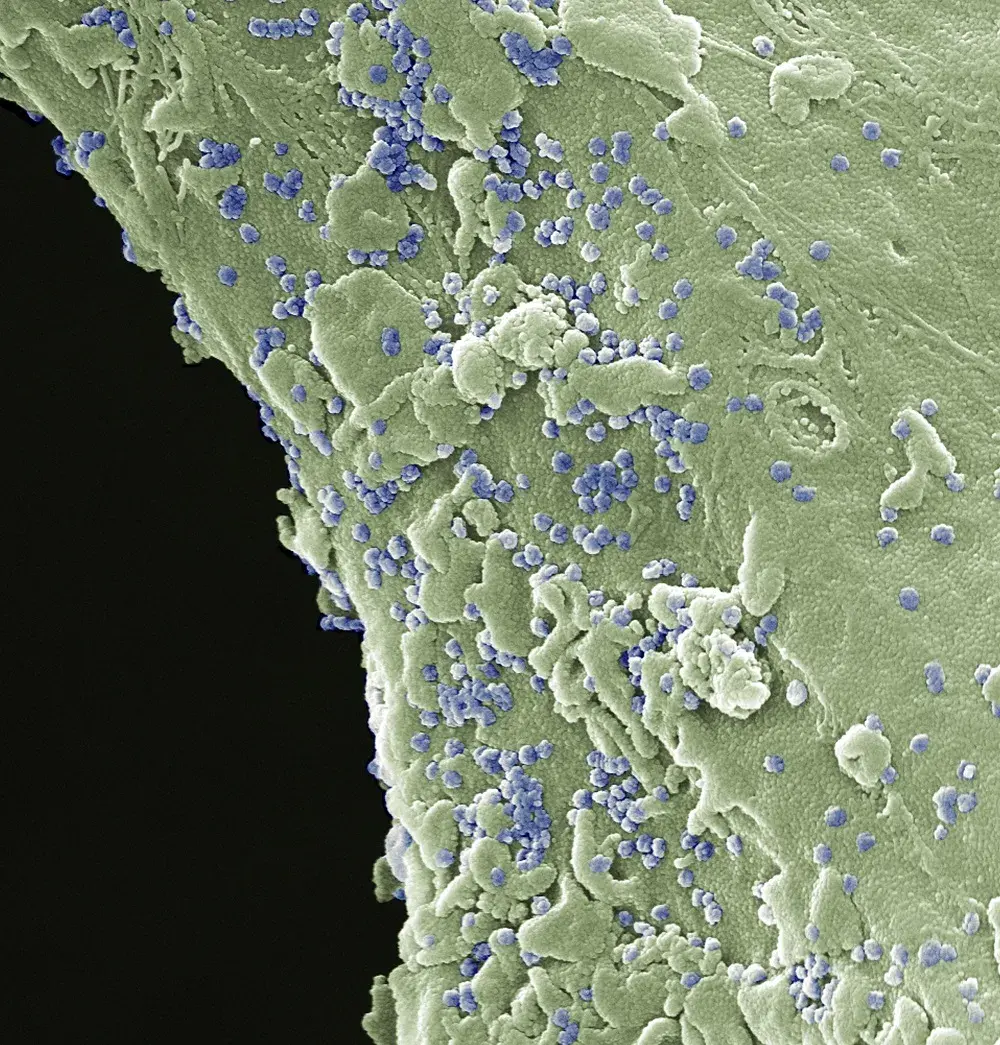

Flu season is here and with the coronavirus pandemic still plaguing much of the world, it’s more important than ever to be health conscious. Countless scientists all over the world are striving to better understand SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, and bringing the most relevant research findings together in one place is key to a coordinated effort.

The Master Question List (MQL) does just that. The MQL organizes our collective knowledge. This consolidation of recent, trustworthy COVID-19 information is updated every week with the latest results and data relevant to weathering the pandemic. The Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Directorate (S&T) started publishing the MQL this past Spring as part of its COVID-19 response .

According to Dr. Lloyd Hough, director of S&T’s Hazard Awareness and Characterization Technology Center, “We go out and conduct searches of a variety of different publications and sources—some of them are traditional scientific sources like the National Library of Medicine, but there are also journal websites and news sources. We go through a lot of these sources and look for vetted information from reliable sources.”

“The MQL is important for us because it identifies what we don’t know,” continued Dr. Hough. “And with finite lab resources, it ensures we don’t duplicate something that is already being studied elsewhere. It’s really a matter of identifying the highest priority gaps—the things that are most impactful for better understanding the disease and helping us to respond to it.”

The list of what we don’t know is still long, but thanks to the dedication of numerous researchers, such as those at S&T’s National Biodefense Analysis and Countermeasures Center (NBACC), many important questions have been answered.

How does it spread from one host to another? How easily is it spread?

COVID-19 is highly contagious, and you can catch it by simply inhaling. It was clear early on that COVID-19 was easily spread through close contact, whether that was person-to-person or by touching contaminated surfaces. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has now acknowledged that airborne transmission is possible under certain circumstances, meaning the virus can spread through particles in the air and not just the larger droplets that can be spread short distances.

It is also important to note that COVID-19 can infect anyone, though it’s worse for some than others. The CDC has found that most symptomatic cases are mild, but severe disease can be found in any age group . Children have proven susceptible (PDF, 28 pgs., 1.85 MB) to COVID-19. We don’t know exactly how infectious they are, but children with positive cases appear to have as much SARS-CoV-2 in their upper respiratory tract as adults.

How long does the virus live in the environment?

How long after infection do symptoms appear? Are people infectious during this time?

According to research collected in the MQL, on average, symptoms develop five days after exposure to the virus and individuals are most infectious before they start showing symptoms. Early iterations of the MQL noted that, “Identifying the contribution of asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic transmission is important for implementing control measures” and this has turned out to be quite true. We now know that pre-symptomatic transmission causes around 40 percent of infections . Also, patients who don’t show any symptoms during the course of their infection can definitely spread the virus. It turns out asymptomatic individuals can transmit the disease as soon as two days after they become infected and at least 12 percent (PDF, 15 pgs., 444 KB) of all cases are estimated to be due to asymptomatic transmission. The CDC recommends that anyone, including those without symptoms, who has been in close contact with a positive COVID-19 case should be tested.

What are the signs and symptoms of an infected person?

Can individuals become re-infected after recovery?

Studies show that re-infection is possible , but rare . Neutralizing antibodies develop in most patients , but the duration of any protection is unknown.

What personal protective equipment (PPE) is effective, and who should be using it?

Face masks are effective at reducing transmission of COVID-19 and almost everyone should be using them. Numerous studies have supported this finding, including research published by the American Society for Microbiology , (PDF, 5 pgs., 1.64MB) the Journal of the American Medical Association , and Nature Research .

The World Health Organization and U.S. CDC recommend wearing face masks when in public settings and when physical distancing is difficult. The benefit is maximized when most of the population wears face masks. Studies show we should avoid masks with exhalation vents or valves as they can allow particles to pass through unfiltered. Medical-grade respirators such as N95 face masks should be reserved for those most vulnerable. S&T research has shown that if handled properly, filtering facepiece respirators can be safely decontaminated for reuse . We also now have data published by the National Institutes of Health showing the effectiveness of homemade face masks varies based on the material used. Layered cotton fabrics with raised visible fibers are best when compared to other household materials such as t-shirts, bandanas, or towels.

How effective are social distancing measures?

Broad-scale control measures such as stay-at-home orders are effective at reducing transmission , as shown by research published in the Journal of Public Health Management & Practice and elsewhere. Social distancing and reductions in both non-essential visits to stores and overall movement distance led to lower transmission rates of COVID-19 in the United States. In hindsight, the data show each day of delay in emergency declarations and school closures was associated with a 5-6 percent increase in mortality . Contact tracing combined with high levels of testing and physical distancing may limit COVID-19 resurgence as restrictions are eased.

There is a path forward.

There are still some questions we don’t have the answer to, like “ How much of the virus will make a healthy individual ill?” which once answered, will help make disinfection efforts, transmission models, and diagnostic practices more accurate. And of course, researchers are furiously working to find effective treatments and a vaccine.

“This is a scary, challenging time,” said Dr. Hough. “We owe it to the essential workers, the overwhelmed parents, the unemployed, and most of all, those who have fallen prey to this insidious disease to do all that we can to be responsible members of our communities. The public needs to buy time for our scientific and medical community.”

In the meantime, we need to follow the recommendations of the CDC and our local public health authorities and stay informed. If you’d like to learn more about any of the science presented here, check out the MQL . Over 700 studies are cited, and again, it is updated every week. You can find comprehensive public health guidance on the CDC website . For related media requests, contact [email protected] .

- Science and Technology

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Environment

Coronavirus and schools: Reflections on education one year into the pandemic

Subscribe to the center for universal education bulletin, daphna bassok , daphna bassok nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , brown center on education policy @daphnabassok lauren bauer , lauren bauer fellow - economic studies , associate director - the hamilton project @laurenlbauer stephanie riegg cellini , stephanie riegg cellini nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , brown center on education policy helen shwe hadani , helen shwe hadani former brookings expert @helenshadani michael hansen , michael hansen senior fellow - brown center on education policy , the herman and george r. brown chair - governance studies @drmikehansen douglas n. harris , douglas n. harris nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , brown center on education policy , professor and chair, department of economics - tulane university @douglasharris99 brad olsen , brad olsen senior fellow - global economy and development , center for universal education @bradolsen_dc richard v. reeves , richard v. reeves president - american institute for boys and men @richardvreeves jon valant , and jon valant director - brown center on education policy , senior fellow - governance studies @jonvalant kenneth k. wong kenneth k. wong nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , brown center on education policy.

March 12, 2021

- 11 min read

One year ago, the World Health Organization declared the spread of COVID-19 a worldwide pandemic. Reacting to the virus, schools at every level were sent scrambling. Institutions across the world switched to virtual learning, with teachers, students, and local leaders quickly adapting to an entirely new way of life. A year later, schools are beginning to reopen, the $1.9 trillion stimulus bill has been passed, and a sense of normalcy seems to finally be in view; in President Joe Biden’s speech last night, he spoke of “finding light in the darkness.” But it’s safe to say that COVID-19 will end up changing education forever, casting a critical light on everything from equity issues to ed tech to school financing.

Below, Brookings experts examine how the pandemic upended the education landscape in the past year, what it’s taught us about schooling, and where we go from here.

In the United States, we tend to focus on the educating roles of public schools, largely ignoring the ways in which schools provide free and essential care for children while their parents work. When COVID-19 shuttered in-person schooling, it eliminated this subsidized child care for many families. It created intense stress for working parents, especially for mothers who left the workforce at a high rate.

The pandemic also highlighted the arbitrary distinction we make between the care and education of elementary school children and children aged 0 to 5 . Despite parents having the same need for care, and children learning more in those earliest years than at any other point, public investments in early care and education are woefully insufficient. The child-care sector was hit so incredibly hard by COVID-19. The recent passage of the American Rescue Plan is a meaningful but long-overdue investment, but much more than a one-time infusion of funds is needed. Hopefully, the pandemic represents a turning point in how we invest in the care and education of young children—and, in turn, in families and society.

Congressional reauthorization of Pandemic EBT for this school year , its extension in the American Rescue Plan (including for summer months), and its place as a central plank in the Biden administration’s anti-hunger agenda is well-warranted and evidence based. But much more needs to be done to ramp up the program–even today , six months after its reauthorization, about half of states do not have a USDA-approved implementation plan.

In contrast, enrollment is up in for-profit and online colleges. The research repeatedly finds weaker student outcomes for these types of institutions relative to community colleges, and many students who enroll in them will be left with more debt than they can reasonably repay. The pandemic and recession have created significant challenges for students, affecting college choices and enrollment decisions in the near future. Ultimately, these short-term choices can have long-term consequences for lifetime earnings and debt that could impact this generation of COVID-19-era college students for years to come.

Many U.S. educationalists are drawing on the “build back better” refrain and calling for the current crisis to be leveraged as a unique opportunity for educators, parents, and policymakers to fully reimagine education systems that are designed for the 21st rather than the 20th century, as we highlight in a recent Brookings report on education reform . An overwhelming body of evidence points to play as the best way to equip children with a broad set of flexible competencies and support their socioemotional development. A recent article in The Atlantic shared parent anecdotes of children playing games like “CoronaBall” and “Social-distance” tag, proving that play permeates children’s lives—even in a pandemic.

Tests play a critical role in our school system. Policymakers and the public rely on results to measure school performance and reveal whether all students are equally served. But testing has also attracted an inordinate share of criticism, alleging that test pressures undermine teacher autonomy and stress students. Much of this criticism will wither away with different formats. The current form of standardized testing—annual, paper-based, multiple-choice tests administered over the course of a week of school—is outdated. With widespread student access to computers (now possible due to the pandemic), states can test students more frequently, but in smaller time blocks that render the experience nearly invisible. Computer adaptive testing can match paper’s reliability and provides a shorter feedback loop to boot. No better time than the present to make this overdue change.

A third push for change will come from the outside in. COVID-19 has reminded us not only of how integral schools are, but how intertwined they are with the rest of society. This means that upcoming schooling changes will also be driven by the effects of COVID-19 on the world around us. In particular, parents will be working more from home, using the same online tools that students can use to learn remotely. This doesn’t mean a mass push for homeschooling, but it probably does mean that hybrid learning is here to stay.

I am hoping we will use this forced rupture in the fabric of schooling to jettison ineffective aspects of education, more fully embrace what we know works, and be bold enough to look for new solutions to the educational problems COVID-19 has illuminated.

There is already a large gender gap in education in the U.S., including in high school graduation rates , and increasingly in college-going and college completion. While the pandemic appears to be hurting women more than men in the labor market, the opposite seems to be true in education.

Looking through a policy lens, though, I’m struck by the timing and what that timing might mean for the future of education. Before the pandemic, enthusiasm for the education reforms that had defined the last few decades—choice and accountability—had waned. It felt like a period between reform eras, with the era to come still very unclear. Then COVID-19 hit, and it coincided with a national reckoning on racial injustice and a wake-up call about the fragility of our democracy. I think it’s helped us all see how connected the work of schools is with so much else in American life.

We’re in a moment when our long-lasting challenges have been laid bare, new challenges have emerged, educators and parents are seeing and experimenting with things for the first time, and the political environment has changed (with, for example, a new administration and changing attitudes on federal spending). I still don’t know where K-12 education is headed, but there’s no doubt that a pivot is underway.

- First, state and local leaders must leverage commitment and shared goals on equitable learning opportunities to support student success for all.

- Second, align and use federal, state, and local resources to implement high-leverage strategies that have proven to accelerate learning for diverse learners and disrupt the correlation between zip code and academic outcomes.

- Third, student-centered priority will require transformative leadership to dismantle the one-size-fits-all delivery rule and institute incentive-based practices for strong performance at all levels.

- Fourth, the reconfigured system will need to activate public and parental engagement to strengthen its civic and social capacity.

- Finally, public education can no longer remain insulated from other policy sectors, especially public health, community development, and social work.

These efforts will strengthen the capacity and prepare our education system for the next crisis—whatever it may be.

Higher Education K-12 Education

Brookings Metro Economic Studies Global Economy and Development Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy Center for Universal Education

Sofoklis Goulas

March 14, 2024

Melissa Kay Diliberti, Stephani L. Wrabel

March 12, 2024

Sarah Reber, Gabriela Goodman

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Education and the COVID-19 pandemic

Sir john daniel.

Acsenda School of Management, Vancouver, Canada

The COVID-19 pandemic is a huge challenge to education systems. This Viewpoint offers guidance to teachers, institutional heads, and officials on addressing the crisis. What preparations should institutions make in the short time available and how do they address students’ needs by level and field of study? Reassuring students and parents is a vital element of institutional response. In ramping up capacity to teach remotely, schools and colleges should take advantage of asynchronous learning, which works best in digital formats. As well as the normal classroom subjects, teaching should include varied assignments and work that puts COVID-19 in a global and historical context. When constructing curricula, designing student assessment first helps teachers to focus. Finally, this Viewpoint suggests flexible ways to repair the damage to students’ learning trajectories once the pandemic is over and gives a list of resources.

The last 50 years have seen huge growth worldwide in the provision of education at all levels. COVID-19 is the greatest challenge that these expanded national education systems have ever faced. Many governments have ordered institutions to cease face-to-face instruction for most of their students, requiring them to switch, almost overnight, to online teaching and virtual education. This brief note offers pragmatic guidance to teachers, institutional heads and state officials who must manage the educational consequences of this crisis. It addresses:

- Preparations that systems could make

- Needs of students at different levels and stages

Reassurance to students and parents

- Simple approaches to remote learning

After COVID-19

- Useful resources.

Preparations

Most governments played catch-up to the exponential spread of COVID-19, so institutions had very little time to prepare for a remote-teaching regime. Where possible, preparations could have included:

- Ensuring that students took home the books, etc., needed for study at home.

- Tying up loose ends; e.g., finalizing test results and reports. In the northern hemisphere, many schoolteachers were in the process of predicting grades of year-end exams for submission with students’ applications to tertiary education. Depending on whether they made them before or after the formal suspension of these exams, teachers’ predictions may have been different, creating anxiety for both themselves and their students.

- Staff preparation and training: arrangements for safeguarding; division of work between departments; mechanisms for teachers to remain in touch collectively for mutual support; and brief and simple updates on learning technologies already somewhat familiar. Many institutions had plans to make greater use of technology in teaching, but the outbreak of COVID-19 has meant that changes intended to occur over months or years had to be implemented in a few days.

Different students, different needs

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the lives of students in different ways, depending not only on their level and course of study but also on the point they have reached in their programmes. Those coming to the end of one phase of their education and moving on to another, such as those transitioning from school to tertiary education, or from tertiary education to employment, face particular challenges. They will not be able to complete their school curriculum and assessment in the normal way and, in many cases, they have been torn away from their social group almost overnight. Students who make the transition to tertiary education later this year are unlikely to take up offers to sit their year-end school exams (e.g., the International Baccalaureate) in a later session.

Even those part-way through their programmes will be anxious until they have clear indications of how their courses and assessment schemes will be restored after the crisis. Many in the COVID-19 cohort of students will worry about suffering long-term disadvantages, compared to those who studied “normally”, when they move to another level of study or enter the labour market. Statements from tertiary institutions that they will apply admission criteria “compassionately” may not always reassure.

While approaches to remote learning will clearly differ as between elementary (primary) school and tertiary education, the needs of skills-sector programmes (Technical and Vocational Education and Training–TVET) need special attention. The graduates of such programmes will have a key role in economic recovery. Providing the practical training they require through distance learning is possible but requires special arrangements. The Commonwealth of Learning is a useful point of reference for TVET in developing countries.

These are anxious times for students and parents. Uncertainties about when life will return to “normal” compound the anxiety. Even as institutions make the changes required to teach in different ways, all should give the highest priority to reassuring students and parents—with targeted communication. Many teachers and counsellors will have to provide this reassurance without clear information from examining bodies and institutions about the arrangements for replacing cancelled examinations and modifying admissions procedures. Institutions should update students and parents with frequent communication on these matters. Teachers and school counsellors may be better than parents at assuaging the anxieties of students in deprived situations. All, however, can access help lines and resources outside the school system that specialize in addressing emotional and psychological challenges.

Fifty years ago, various jurisdictions created “open” universities in order to equalize opportunity by extending access to tertiary education through distance learning. Sadly, the current imperative of continuing schooling by hasty transitions to remote learning may have the opposite impact. Institutions and educational systems must make special efforts to help those students whose parents are unsupportive and whose home environments are not conducive to study. Where households are confined to their residences by COVID-19, parents and guardians may be deeply anxious about their own economic future, so studying at home is not easy, especially for children with low motivation. Such homes often lack the equipment and connectivity that richer households take for granted, compounding the problem.

Simple approaches to remote teaching: Use asynchronous learning

Just as institutions take steps to inform, reassure and maintain contact with students and parents, they must also ramp up their ability to teach remotely. This emergency is not the time to put into effect complex institutional plans for distance learning that were meant to be implemented over months or years. The witticism that “if a job is worth doing, it’s worth doing badly” has validity. Teachers should work with what they know. Giving full attention to reassuring students is more important than trying to learn new pedagogy or technology on the fly.

The most important adjustment, for those used to teaching in classrooms in real time, is to take advantage of asynchronous learning. For most aspects of learning and teaching, the participants do not have to communicate simultaneously. Asynchronous working gives teachers flexibility in preparing learning materials and enables students to juggle the demands of home and study. Asynchronous learning works best in digital formats. Teachers do not need to deliver material at a fixed time: it can be posted online for on-demand access and students can engage with it using wikis, blogs, and e-mail to suit their schedules. Teachers can check on student participation periodically and make online appointments for students with particular needs or questions. Creating an asynchronous digital classroom gives teachers and students more room to breathe.

Similarly, video lessons are usually more effective—as well as easier to prepare—if they are short (5‒10 minutes). Organizations offering large-enrolment online courses, such as FutureLearn, have optimized approaches to remote learning that balance accessibility and effectiveness. Anyone asked to teach remotely can log in to a FutureLearn course in their subject area to observe the use of short videos. Teachers might also wish to flag relevant online courses to their students.

What curriculum should teachers use for remote learning during the COVID-19 crisis? The response will vary by jurisdiction. Some have prescriptive national curricula, whereas others give wide discretion to teachers to choose programme content. General advice is for teachers to keep two objectives in mind. While it is important to continue to orient students’ learning to the classroom curriculum and the assessments/examinations for which they were preparing, it is also vital to maintain students’ interest in learning by giving them varied assignments—not least, perhaps, by work that sets the present COVID-19 crisis in a wider global and historical context. Some schools are encouraging students to engage with the crisis by preparing hampers of food and supplies for vulnerable families or writing letters to elderly residents in care homes.

For such enrichment, teachers can draw on the abundance of high-quality learning material now available as freely usable Open Educational Resources. The OpenLearn website, for example, contains over 1,000 courses at both school and tertiary levels. There is no dishonour in teaching through good materials prepared by others.

End-of-year examinations in the northern hemisphere have been cancelled or suspended by many examining bodies (e.g., the International Baccalaureate Organisation), with a knock-on impact in the southern hemisphere. This has left millions of students, even those who do not relish examinations, feeling left in the lurch. At this moment (April 2020), as COVID-19 still rages in most parts of the world, these bodies are unable to say when they will resume normal operations and how, if at all, they will provide results for this year’s cohort.

Institutions versed in distance learning often start the process of course construction by designing the student assessments that will be part of it. This is a way of clarifying learning objectives and content that teachers making a sudden transition to remote operation should consider adopting. It will help them determine the parts of the standard curriculum on which they will focus as well as their aims in including other topics.

Until countries can judge when the trade-off between economic activity and public health will enable them to ease restrictions on normal life, anxiety about the extent and duration of the special COVID-19 arrangements in each jurisdiction will continue. Moreover, the return to normality will not be a simple one-time transition to life as it used to be. Jurisdictions will assess risks differently and all will take precautionary measures against second and third waves of COVID-19 outbreaks.

Institutions, teachers, and students will continue to look for flexible ways to repair the damage caused by COVID-19’s interruptions to learning trajectories. In this context, the open schools (e.g., India’s National Institute of Open Schooling; the New Zealand Correspondence School) and open universities (e.g., The UK Open University; Athabasca University, Canada)—most of which have continued to operate through the COVID-19 pandemic—can sometimes provide the variety of courses and flexibility of time and place of learning to help students get back on track.

Although institutions that normally teach face-to-face in classrooms or on campuses will likely return to that mode of instruction with some relief, the special arrangements they put in place during the COVID-19 crisis will leave a lasting trace. The expansion of online learning in tertiary education will further accelerate, and schools will organize themselves more systematically to pursue the aspects of technology-based learning that they have found most useful.

All institutions will derive benefit from the mechanisms that they have put in place to continue their educational and training missions in a time of crisis.

This is a small selection of the huge array of resources on which educators wishing to adopt remote learning can draw. To put them in context:

- The Commonwealth of Learning is an intergovernmental agency of the Commonwealth tasked with helping developing countries use technology effectively in education and training at all levels. It focuses particularly on technology that is appropriate for resource-poor situations.

Commonwealth of Learning. (Skills training [TVET] for men and women): https://www.col.org/programmes/technical-and-vocational-skills-development

Commonwealth of Learning. (Open Schooling): https://www.col.org/programmes/open-schooling

- These references from David Gaertner and the Sacred Heart Schools bracket a range of responses to COVID-19, from “work with what you know” to carefully organised and gradual processes.

David Gaertner, #COVIDCAMPUS: https://novelalliances.com/2020/03/16/covidcampus/

Sacred Heart Schools: Flexible Plan for Instructional Continuity: https://tinyurl.com/rrqfae7

- UNESCO has much experience in advising Member States how to adapt their educational systems to crises of various kinds.

UNESCO—Distance learning solutions: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse/solutions

- The YTL Foundation is an example of national provision of online resources to teachers, parents, and students.

YTL Foundation, Malaysia: https://ytlfoundation.org/learnfromhome/

- FutureLearn and OpenLearn are important collections of online courses and course resources under the aegis of the UK Open University.

FutureLearn (free mass enrolment courses on many topics): https://www.futurelearn.com/

OpenLearn: Free learning from the Open University: https://www.open.edu/openlearn/

- Open Schools: There are open schools offering flexible schooling to large numbers of pupils in various countries. Three examples are India ( https://www.nios.ac.in/ ), Namibia ( https://www.namcol.edu.na/ ), and New Zealand ( https://www.tekura.school.nz/ )

- Open Universities: Some 50 jurisdictions around the world have established open universities, which enroll millions of students between them. Three examples are Canada ( https://www.athabascau.ca/ , Tanzania ( https://www.out.ac.tz/ ), and the United Kingdom ( http://www.open.ac.uk/ ).

- Surrey County Council: Resources for families—examples of links recommended by an English regional government.

Talking to your child about coronavirus: https://youngminds.org.uk/blog/talking-to-your-child-about-coronavirus/

How to look after your family’s mental health when you’re stuck indoors: https://parentinfo.org/article/how-to-look-after-your-family-s-mental-health-when-you-re-stuck-indoors

Keeping children happy and safe online during COVID-19: https://www.saferinternet.org.uk/blog/keeping-children-happy-and-safe-online-during-covid-19 .

Sir John Daniel (Canada, United Kingdom)

was educated at Christ’s Hospital School and the Universities of Oxford and Paris. After completing degrees in Metallurgy, he taught at the École Polytechnique, Montréal before studies in Educational Technology led him to re-orient his career to open and distance education and take up appointments that included 17 years as a university president at Laurentian University, Ontario; and the UK Open University. After serving as Assistant Director-General for Education at UNESCO from 2001 to 2004, he moved to Vancouver as president of the Commonwealth of Learning in 2004. He was knighted in 1994, appointed to the Order of Canada in 2013, and holds 32 honorary doctorates from universities in 17 countries. His 390 publications include Mega-universities and Knowledge Media: Technology Strategies for Higher Education and Mega-Schools, Technology and Teachers: Achieving Education for All.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

How to Write About Coronavirus in a College Essay

Students can share how they navigated life during the coronavirus pandemic in a full-length essay or an optional supplement.

Writing About COVID-19 in College Essays

Getty Images

Experts say students should be honest and not limit themselves to merely their experiences with the pandemic.

The global impact of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, means colleges and prospective students alike are in for an admissions cycle like no other. Both face unprecedented challenges and questions as they grapple with their respective futures amid the ongoing fallout of the pandemic.

Colleges must examine applicants without the aid of standardized test scores for many – a factor that prompted many schools to go test-optional for now . Even grades, a significant component of a college application, may be hard to interpret with some high schools adopting pass-fail classes last spring due to the pandemic. Major college admissions factors are suddenly skewed.

"I can't help but think other (admissions) factors are going to matter more," says Ethan Sawyer, founder of the College Essay Guy, a website that offers free and paid essay-writing resources.

College essays and letters of recommendation , Sawyer says, are likely to carry more weight than ever in this admissions cycle. And many essays will likely focus on how the pandemic shaped students' lives throughout an often tumultuous 2020.

But before writing a college essay focused on the coronavirus, students should explore whether it's the best topic for them.

Writing About COVID-19 for a College Application

Much of daily life has been colored by the coronavirus. Virtual learning is the norm at many colleges and high schools, many extracurriculars have vanished and social lives have stalled for students complying with measures to stop the spread of COVID-19.

"For some young people, the pandemic took away what they envisioned as their senior year," says Robert Alexander, dean of admissions, financial aid and enrollment management at the University of Rochester in New York. "Maybe that's a spot on a varsity athletic team or the lead role in the fall play. And it's OK for them to mourn what should have been and what they feel like they lost, but more important is how are they making the most of the opportunities they do have?"

That question, Alexander says, is what colleges want answered if students choose to address COVID-19 in their college essay.

But the question of whether a student should write about the coronavirus is tricky. The answer depends largely on the student.

"In general, I don't think students should write about COVID-19 in their main personal statement for their application," Robin Miller, master college admissions counselor at IvyWise, a college counseling company, wrote in an email.

"Certainly, there may be exceptions to this based on a student's individual experience, but since the personal essay is the main place in the application where the student can really allow their voice to be heard and share insight into who they are as an individual, there are likely many other topics they can choose to write about that are more distinctive and unique than COVID-19," Miller says.

Opinions among admissions experts vary on whether to write about the likely popular topic of the pandemic.

"If your essay communicates something positive, unique, and compelling about you in an interesting and eloquent way, go for it," Carolyn Pippen, principal college admissions counselor at IvyWise, wrote in an email. She adds that students shouldn't be dissuaded from writing about a topic merely because it's common, noting that "topics are bound to repeat, no matter how hard we try to avoid it."

Above all, she urges honesty.

"If your experience within the context of the pandemic has been truly unique, then write about that experience, and the standing out will take care of itself," Pippen says. "If your experience has been generally the same as most other students in your context, then trying to find a unique angle can easily cross the line into exploiting a tragedy, or at least appearing as though you have."

But focusing entirely on the pandemic can limit a student to a single story and narrow who they are in an application, Sawyer says. "There are so many wonderful possibilities for what you can say about yourself outside of your experience within the pandemic."

He notes that passions, strengths, career interests and personal identity are among the multitude of essay topic options available to applicants and encourages them to probe their values to help determine the topic that matters most to them – and write about it.

That doesn't mean the pandemic experience has to be ignored if applicants feel the need to write about it.

Writing About Coronavirus in Main and Supplemental Essays