When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

Welcome to the PLOS Writing Center

Your source for scientific writing & publishing essentials.

A collection of free, practical guides and hands-on resources for authors looking to improve their scientific publishing skillset.

ARTICLE-WRITING ESSENTIALS

Your title is the first thing anyone who reads your article is going to see, and for many it will be where they stop reading. Learn how to write a title that helps readers find your article, draws your audience in and sets the stage for your research!

The abstract is your chance to let your readers know what they can expect from your article. Learn how to write a clear, and concise abstract that will keep your audience reading.

A clear methods section impacts editorial evaluation and readers’ understanding, and is also the backbone of transparency and replicability. Learn what to include in your methods section, and how much detail is appropriate.

In many fields, a statistical analysis forms the heart of both the methods and results sections of a manuscript. Learn how to report statistical analyses, and what other context is important for publication success and future reproducibility.

The discussion section contains the results and outcomes of a study. An effective discussion informs readers what can be learned from your experiment and provides context for the results.

Ensuring your manuscript is well-written makes it easier for editors, reviewers and readers to understand your work. Avoiding language errors can help accelerate review and minimize delays in the publication of your research.

The PLOS Writing Toolbox

Delivered to your inbox every two weeks, the Writing Toolbox features practical advice and tools you can use to prepare a research manuscript for submission success and build your scientific writing skillset.

Discover how to navigate the peer review and publishing process, beyond writing your article.

The path to publication can be unsettling when you’re unsure what’s happening with your paper. Learn about staple journal workflows to see the detailed steps required for ensuring a rigorous and ethical publication.

Reputable journals screen for ethics at submission—and inability to pass ethics checks is one of the most common reasons for rejection. Unfortunately, once a study has begun, it’s often too late to secure the requisite ethical reviews and clearances. Learn how to prepare for publication success by ensuring your study meets all ethical requirements before work begins.

From preregistration, to preprints, to publication—learn how and when to share your study.

How you store your data matters. Even after you publish your article, your data needs to be accessible and useable for the long term so that other researchers can continue building on your work. Good data management practices make your data discoverable and easy to use, promote a strong foundation for reproducibility and increase your likelihood of citations.

You’ve just spent months completing your study, writing up the results and submitting to your top-choice journal. Now the feedback is in and it’s time to revise. Set out a clear plan for your response to keep yourself on-track and ensure edits don’t fall through the cracks.

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher.

Are you actively preparing a submission for a PLOS journal? Select the relevant journal below for more detailed guidelines.

How to Write an Article

Share the lessons of the Writing Center in a live, interactive training.

Access tried-and-tested training modules, complete with slides and talking points, workshop activities, and more.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 28 February 2018

- Correction 16 March 2018

How to write a first-class paper

- Virginia Gewin 0

Virginia Gewin is a freelance writer in Portland, Oregon.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Manuscripts may have a rigidly defined structure, but there’s still room to tell a compelling story — one that clearly communicates the science and is a pleasure to read. Scientist-authors and editors debate the importance and meaning of creativity and offer tips on how to write a top paper.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 555 , 129-130 (2018)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-02404-4

Interviews have been edited for clarity and length.

Updates & Corrections

Correction 16 March 2018 : This article should have made clear that Altmetric is part of Digital Science, a company owned by Holtzbrinck Publishing Group, which is also the majority shareholder in Nature’s publisher, Springer Nature. Nature Research Editing Services is also owned by Springer Nature.

Related Articles

How I harnessed media engagement to supercharge my research career

Career Column 09 APR 24

How we landed job interviews for professorships straight out of our PhD programmes

Career Column 08 APR 24

Three ways ChatGPT helps me in my academic writing

Is ChatGPT corrupting peer review? Telltale words hint at AI use

News 10 APR 24

Rwanda 30 years on: understanding the horror of genocide

Editorial 09 APR 24

Junior Group Leader Position at IMBA - Institute of Molecular Biotechnology

The Institute of Molecular Biotechnology (IMBA) is one of Europe’s leading institutes for basic research in the life sciences. IMBA is located on t...

Austria (AT)

IMBA - Institute of Molecular Biotechnology

Open Rank Faculty, Center for Public Health Genomics

Center for Public Health Genomics & UVA Comprehensive Cancer Center seek 2 tenure-track faculty members in Cancer Precision Medicine/Precision Health.

Charlottesville, Virginia

Center for Public Health Genomics at the University of Virginia

Husbandry Technician I

Memphis, Tennessee

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (St. Jude)

Lead Researcher – Department of Bone Marrow Transplantation & Cellular Therapy

Researcher in the center for in vivo imaging and therapy.

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Typical structure of a research paper

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal

- Open access

- Published: 30 April 2020

- Volume 36 , pages 909–913, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Clara Busse ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0178-1000 1 &

- Ella August ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5151-1036 1 , 2

266k Accesses

15 Citations

705 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Communicating research findings is an essential step in the research process. Often, peer-reviewed journals are the forum for such communication, yet many researchers are never taught how to write a publishable scientific paper. In this article, we explain the basic structure of a scientific paper and describe the information that should be included in each section. We also identify common pitfalls for each section and recommend strategies to avoid them. Further, we give advice about target journal selection and authorship. In the online resource 1 , we provide an example of a high-quality scientific paper, with annotations identifying the elements we describe in this article.

Similar content being viewed by others

Literature reviews as independent studies: guidelines for academic practice

Sascha Kraus, Matthias Breier, … João J. Ferreira

Plagiarism in research

Gert Helgesson & Stefan Eriksson

Open peer review: promoting transparency in open science

Dietmar Wolfram, Peiling Wang, … Hyoungjoo Park

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Writing a scientific paper is an important component of the research process, yet researchers often receive little formal training in scientific writing. This is especially true in low-resource settings. In this article, we explain why choosing a target journal is important, give advice about authorship, provide a basic structure for writing each section of a scientific paper, and describe common pitfalls and recommendations for each section. In the online resource 1 , we also include an annotated journal article that identifies the key elements and writing approaches that we detail here. Before you begin your research, make sure you have ethical clearance from all relevant ethical review boards.

Select a Target Journal Early in the Writing Process

We recommend that you select a “target journal” early in the writing process; a “target journal” is the journal to which you plan to submit your paper. Each journal has a set of core readers and you should tailor your writing to this readership. For example, if you plan to submit a manuscript about vaping during pregnancy to a pregnancy-focused journal, you will need to explain what vaping is because readers of this journal may not have a background in this topic. However, if you were to submit that same article to a tobacco journal, you would not need to provide as much background information about vaping.

Information about a journal’s core readership can be found on its website, usually in a section called “About this journal” or something similar. For example, the Journal of Cancer Education presents such information on the “Aims and Scope” page of its website, which can be found here: https://www.springer.com/journal/13187/aims-and-scope .

Peer reviewer guidelines from your target journal are an additional resource that can help you tailor your writing to the journal and provide additional advice about crafting an effective article [ 1 ]. These are not always available, but it is worth a quick web search to find out.

Identify Author Roles Early in the Process

Early in the writing process, identify authors, determine the order of authors, and discuss the responsibilities of each author. Standard author responsibilities have been identified by The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) [ 2 ]. To set clear expectations about each team member’s responsibilities and prevent errors in communication, we also suggest outlining more detailed roles, such as who will draft each section of the manuscript, write the abstract, submit the paper electronically, serve as corresponding author, and write the cover letter. It is best to formalize this agreement in writing after discussing it, circulating the document to the author team for approval. We suggest creating a title page on which all authors are listed in the agreed-upon order. It may be necessary to adjust authorship roles and order during the development of the paper. If a new author order is agreed upon, be sure to update the title page in the manuscript draft.

In the case where multiple papers will result from a single study, authors should discuss who will author each paper. Additionally, authors should agree on a deadline for each paper and the lead author should take responsibility for producing an initial draft by this deadline.

Structure of the Introduction Section

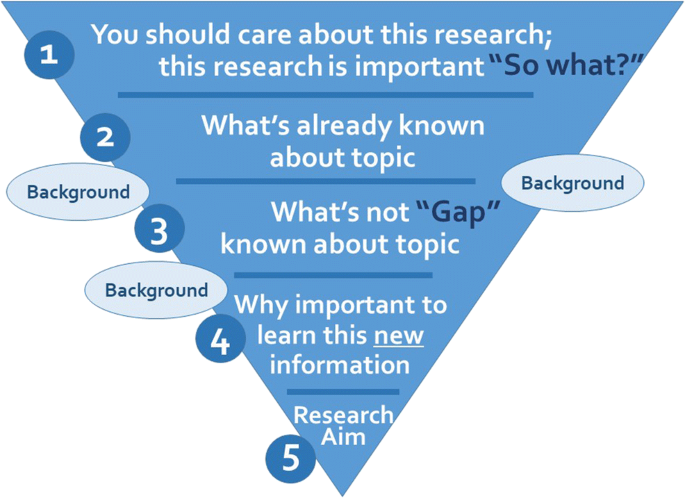

The introduction section should be approximately three to five paragraphs in length. Look at examples from your target journal to decide the appropriate length. This section should include the elements shown in Fig. 1 . Begin with a general context, narrowing to the specific focus of the paper. Include five main elements: why your research is important, what is already known about the topic, the “gap” or what is not yet known about the topic, why it is important to learn the new information that your research adds, and the specific research aim(s) that your paper addresses. Your research aim should address the gap you identified. Be sure to add enough background information to enable readers to understand your study. Table 1 provides common introduction section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

The main elements of the introduction section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Methods Section

The purpose of the methods section is twofold: to explain how the study was done in enough detail to enable its replication and to provide enough contextual detail to enable readers to understand and interpret the results. In general, the essential elements of a methods section are the following: a description of the setting and participants, the study design and timing, the recruitment and sampling, the data collection process, the dataset, the dependent and independent variables, the covariates, the analytic approach for each research objective, and the ethical approval. The hallmark of an exemplary methods section is the justification of why each method was used. Table 2 provides common methods section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Results Section

The focus of the results section should be associations, or lack thereof, rather than statistical tests. Two considerations should guide your writing here. First, the results should present answers to each part of the research aim. Second, return to the methods section to ensure that the analysis and variables for each result have been explained.

Begin the results section by describing the number of participants in the final sample and details such as the number who were approached to participate, the proportion who were eligible and who enrolled, and the number of participants who dropped out. The next part of the results should describe the participant characteristics. After that, you may organize your results by the aim or by putting the most exciting results first. Do not forget to report your non-significant associations. These are still findings.

Tables and figures capture the reader’s attention and efficiently communicate your main findings [ 3 ]. Each table and figure should have a clear message and should complement, rather than repeat, the text. Tables and figures should communicate all salient details necessary for a reader to understand the findings without consulting the text. Include information on comparisons and tests, as well as information about the sample and timing of the study in the title, legend, or in a footnote. Note that figures are often more visually interesting than tables, so if it is feasible to make a figure, make a figure. To avoid confusing the reader, either avoid abbreviations in tables and figures, or define them in a footnote. Note that there should not be citations in the results section and you should not interpret results here. Table 3 provides common results section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

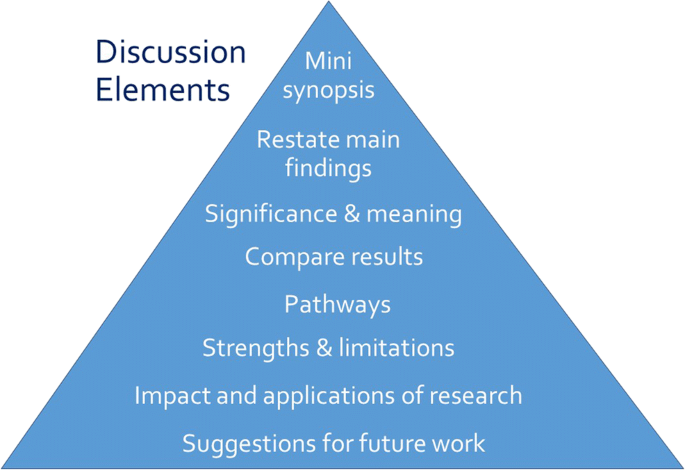

Discussion Section

Opposite the introduction section, the discussion should take the form of a right-side-up triangle beginning with interpretation of your results and moving to general implications (Fig. 2 ). This section typically begins with a restatement of the main findings, which can usually be accomplished with a few carefully-crafted sentences.

Major elements of the discussion section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Next, interpret the meaning or explain the significance of your results, lifting the reader’s gaze from the study’s specific findings to more general applications. Then, compare these study findings with other research. Are these findings in agreement or disagreement with those from other studies? Does this study impart additional nuance to well-accepted theories? Situate your findings within the broader context of scientific literature, then explain the pathways or mechanisms that might give rise to, or explain, the results.

Journals vary in their approach to strengths and limitations sections: some are embedded paragraphs within the discussion section, while some mandate separate section headings. Keep in mind that every study has strengths and limitations. Candidly reporting yours helps readers to correctly interpret your research findings.

The next element of the discussion is a summary of the potential impacts and applications of the research. Should these results be used to optimally design an intervention? Does the work have implications for clinical protocols or public policy? These considerations will help the reader to further grasp the possible impacts of the presented work.

Finally, the discussion should conclude with specific suggestions for future work. Here, you have an opportunity to illuminate specific gaps in the literature that compel further study. Avoid the phrase “future research is necessary” because the recommendation is too general to be helpful to readers. Instead, provide substantive and specific recommendations for future studies. Table 4 provides common discussion section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Follow the Journal’s Author Guidelines

After you select a target journal, identify the journal’s author guidelines to guide the formatting of your manuscript and references. Author guidelines will often (but not always) include instructions for titles, cover letters, and other components of a manuscript submission. Read the guidelines carefully. If you do not follow the guidelines, your article will be sent back to you.

Finally, do not submit your paper to more than one journal at a time. Even if this is not explicitly stated in the author guidelines of your target journal, it is considered inappropriate and unprofessional.

Your title should invite readers to continue reading beyond the first page [ 4 , 5 ]. It should be informative and interesting. Consider describing the independent and dependent variables, the population and setting, the study design, the timing, and even the main result in your title. Because the focus of the paper can change as you write and revise, we recommend you wait until you have finished writing your paper before composing the title.

Be sure that the title is useful for potential readers searching for your topic. The keywords you select should complement those in your title to maximize the likelihood that a researcher will find your paper through a database search. Avoid using abbreviations in your title unless they are very well known, such as SNP, because it is more likely that someone will use a complete word rather than an abbreviation as a search term to help readers find your paper.

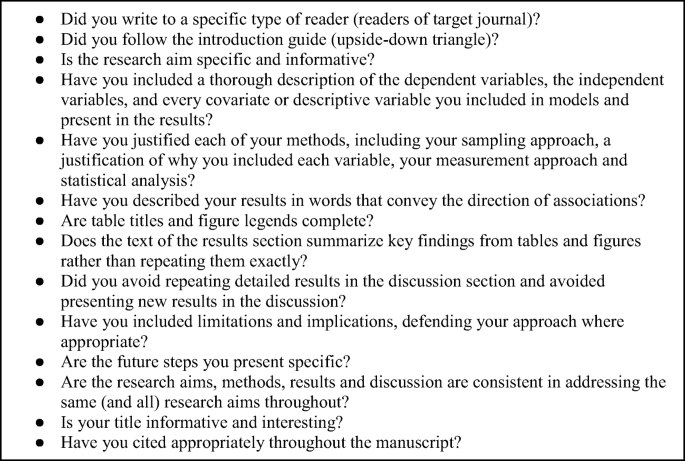

After you have written a complete draft, use the checklist (Fig. 3 ) below to guide your revisions and editing. Additional resources are available on writing the abstract and citing references [ 5 ]. When you feel that your work is ready, ask a trusted colleague or two to read the work and provide informal feedback. The box below provides a checklist that summarizes the key points offered in this article.

Checklist for manuscript quality

Data Availability

Michalek AM (2014) Down the rabbit hole…advice to reviewers. J Cancer Educ 29:4–5

Article Google Scholar

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Defining the role of authors and contributors: who is an author? http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/defining-the-role-of-authosrs-and-contributors.html . Accessed 15 January, 2020

Vetto JT (2014) Short and sweet: a short course on concise medical writing. J Cancer Educ 29(1):194–195

Brett M, Kording K (2017) Ten simple rules for structuring papers. PLoS ComputBiol. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005619

Lang TA (2017) Writing a better research article. J Public Health Emerg. https://doi.org/10.21037/jphe.2017.11.06

Download references

Acknowledgments

Ella August is grateful to the Sustainable Sciences Institute for mentoring her in training researchers on writing and publishing their research.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Maternal and Child Health, University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health, 135 Dauer Dr, 27599, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Clara Busse & Ella August

Department of Epidemiology, University of Michigan School of Public Health, 1415 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, MI, 48109-2029, USA

Ella August

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ella August .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interests.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 362 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Busse, C., August, E. How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal. J Canc Educ 36 , 909–913 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01751-z

Download citation

Published : 30 April 2020

Issue Date : October 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01751-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Manuscripts

- Scientific writing

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Scientific Writing: Structuring a scientific article

- Resume/Cover letter

- Structuring a scientific article

- AMA Citation Style This link opens in a new window

- APA Citation Style This link opens in a new window

- Scholarly Publishing This link opens in a new window

How to Structure a Scientific Article

Many scientific articles include the following elements:

I. Abstract: The abstract should briefly summarize the contents of your article. Be sure to include a quick overview of the focus, results and conclusion of your study.

II. Introduction: The introduction should include any relevant background information and articulate the idea that is being investigated. Why is this study unique? If others have performed research on the topic, include a literature review.

III. Methods and Materials: The methods and materials section should provide information on how the study was conducted and what materials were included. Other researchers should be able to reproduce your study based on the information found in this section.

IV. Results: The results sections includes the data produced by your study. It should reflect an unbiased account of the study's findings.

V. Discussion and Conclusion: The discussion section provides information on what researches felt was significant and analyzes the data. You may also want to provide final thoughts and ideas for further research in the conclusion section.

For more information, see How to Read a Scientific Paper.

Scientific Article Infographic

- Structure of a Scientific Article

- << Previous: Resume/Cover letter

- Next: AMA Citation Style >>

- Last Updated: Jan 23, 2023 11:48 AM

- URL: https://guides.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/scientific-writing

- Himmelfarb Intranet

- Privacy Notice

- Terms of Use

- GW is committed to digital accessibility. If you experience a barrier that affects your ability to access content on this page, let us know via the Accessibility Feedback Form .

- Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library

- 2300 Eye St., NW, Washington, DC 20037

- Phone: (202) 994-2850

- [email protected]

- https://himmelfarb.gwu.edu

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Paper

Definition:

Research Paper is a written document that presents the author’s original research, analysis, and interpretation of a specific topic or issue.

It is typically based on Empirical Evidence, and may involve qualitative or quantitative research methods, or a combination of both. The purpose of a research paper is to contribute new knowledge or insights to a particular field of study, and to demonstrate the author’s understanding of the existing literature and theories related to the topic.

Structure of Research Paper

The structure of a research paper typically follows a standard format, consisting of several sections that convey specific information about the research study. The following is a detailed explanation of the structure of a research paper:

The title page contains the title of the paper, the name(s) of the author(s), and the affiliation(s) of the author(s). It also includes the date of submission and possibly, the name of the journal or conference where the paper is to be published.

The abstract is a brief summary of the research paper, typically ranging from 100 to 250 words. It should include the research question, the methods used, the key findings, and the implications of the results. The abstract should be written in a concise and clear manner to allow readers to quickly grasp the essence of the research.

Introduction

The introduction section of a research paper provides background information about the research problem, the research question, and the research objectives. It also outlines the significance of the research, the research gap that it aims to fill, and the approach taken to address the research question. Finally, the introduction section ends with a clear statement of the research hypothesis or research question.

Literature Review

The literature review section of a research paper provides an overview of the existing literature on the topic of study. It includes a critical analysis and synthesis of the literature, highlighting the key concepts, themes, and debates. The literature review should also demonstrate the research gap and how the current study seeks to address it.

The methods section of a research paper describes the research design, the sample selection, the data collection and analysis procedures, and the statistical methods used to analyze the data. This section should provide sufficient detail for other researchers to replicate the study.

The results section presents the findings of the research, using tables, graphs, and figures to illustrate the data. The findings should be presented in a clear and concise manner, with reference to the research question and hypothesis.

The discussion section of a research paper interprets the findings and discusses their implications for the research question, the literature review, and the field of study. It should also address the limitations of the study and suggest future research directions.

The conclusion section summarizes the main findings of the study, restates the research question and hypothesis, and provides a final reflection on the significance of the research.

The references section provides a list of all the sources cited in the paper, following a specific citation style such as APA, MLA or Chicago.

How to Write Research Paper

You can write Research Paper by the following guide:

- Choose a Topic: The first step is to select a topic that interests you and is relevant to your field of study. Brainstorm ideas and narrow down to a research question that is specific and researchable.

- Conduct a Literature Review: The literature review helps you identify the gap in the existing research and provides a basis for your research question. It also helps you to develop a theoretical framework and research hypothesis.

- Develop a Thesis Statement : The thesis statement is the main argument of your research paper. It should be clear, concise and specific to your research question.

- Plan your Research: Develop a research plan that outlines the methods, data sources, and data analysis procedures. This will help you to collect and analyze data effectively.

- Collect and Analyze Data: Collect data using various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments. Analyze data using statistical tools or other qualitative methods.

- Organize your Paper : Organize your paper into sections such as Introduction, Literature Review, Methods, Results, Discussion, and Conclusion. Ensure that each section is coherent and follows a logical flow.

- Write your Paper : Start by writing the introduction, followed by the literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. Ensure that your writing is clear, concise, and follows the required formatting and citation styles.

- Edit and Proofread your Paper: Review your paper for grammar and spelling errors, and ensure that it is well-structured and easy to read. Ask someone else to review your paper to get feedback and suggestions for improvement.

- Cite your Sources: Ensure that you properly cite all sources used in your research paper. This is essential for giving credit to the original authors and avoiding plagiarism.

Research Paper Example

Note : The below example research paper is for illustrative purposes only and is not an actual research paper. Actual research papers may have different structures, contents, and formats depending on the field of study, research question, data collection and analysis methods, and other factors. Students should always consult with their professors or supervisors for specific guidelines and expectations for their research papers.

Research Paper Example sample for Students:

Title: The Impact of Social Media on Mental Health among Young Adults

Abstract: This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults. A literature review was conducted to examine the existing research on the topic. A survey was then administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Introduction: Social media has become an integral part of modern life, particularly among young adults. While social media has many benefits, including increased communication and social connectivity, it has also been associated with negative outcomes, such as addiction, cyberbullying, and mental health problems. This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults.

Literature Review: The literature review highlights the existing research on the impact of social media use on mental health. The review shows that social media use is associated with depression, anxiety, stress, and other mental health problems. The review also identifies the factors that contribute to the negative impact of social media, including social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Methods : A survey was administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The survey included questions on social media use, mental health status (measured using the DASS-21), and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and regression analysis.

Results : The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Discussion : The study’s findings suggest that social media use has a negative impact on the mental health of young adults. The study highlights the need for interventions that address the factors contributing to the negative impact of social media, such as social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Conclusion : In conclusion, social media use has a significant impact on the mental health of young adults. The study’s findings underscore the need for interventions that promote healthy social media use and address the negative outcomes associated with social media use. Future research can explore the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health. Additionally, longitudinal studies can investigate the long-term effects of social media use on mental health.

Limitations : The study has some limitations, including the use of self-report measures and a cross-sectional design. The use of self-report measures may result in biased responses, and a cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causality.

Implications: The study’s findings have implications for mental health professionals, educators, and policymakers. Mental health professionals can use the findings to develop interventions that address the negative impact of social media use on mental health. Educators can incorporate social media literacy into their curriculum to promote healthy social media use among young adults. Policymakers can use the findings to develop policies that protect young adults from the negative outcomes associated with social media use.

References :

- Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2019). Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Preventive medicine reports, 15, 100918.

- Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Barrett, E. L., Sidani, J. E., Colditz, J. B., … & James, A. E. (2017). Use of multiple social media platforms and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A nationally-representative study among US young adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 1-9.

- Van der Meer, T. G., & Verhoeven, J. W. (2017). Social media and its impact on academic performance of students. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 16, 383-398.

Appendix : The survey used in this study is provided below.

Social Media and Mental Health Survey

- How often do you use social media per day?

- Less than 30 minutes

- 30 minutes to 1 hour

- 1 to 2 hours

- 2 to 4 hours

- More than 4 hours

- Which social media platforms do you use?

- Others (Please specify)

- How often do you experience the following on social media?

- Social comparison (comparing yourself to others)

- Cyberbullying

- Fear of Missing Out (FOMO)

- Have you ever experienced any of the following mental health problems in the past month?

- Do you think social media use has a positive or negative impact on your mental health?

- Very positive

- Somewhat positive

- Somewhat negative

- Very negative

- In your opinion, which factors contribute to the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Social comparison

- In your opinion, what interventions could be effective in reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Education on healthy social media use

- Counseling for mental health problems caused by social media

- Social media detox programs

- Regulation of social media use

Thank you for your participation!

Applications of Research Paper

Research papers have several applications in various fields, including:

- Advancing knowledge: Research papers contribute to the advancement of knowledge by generating new insights, theories, and findings that can inform future research and practice. They help to answer important questions, clarify existing knowledge, and identify areas that require further investigation.

- Informing policy: Research papers can inform policy decisions by providing evidence-based recommendations for policymakers. They can help to identify gaps in current policies, evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, and inform the development of new policies and regulations.

- Improving practice: Research papers can improve practice by providing evidence-based guidance for professionals in various fields, including medicine, education, business, and psychology. They can inform the development of best practices, guidelines, and standards of care that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- Educating students : Research papers are often used as teaching tools in universities and colleges to educate students about research methods, data analysis, and academic writing. They help students to develop critical thinking skills, research skills, and communication skills that are essential for success in many careers.

- Fostering collaboration: Research papers can foster collaboration among researchers, practitioners, and policymakers by providing a platform for sharing knowledge and ideas. They can facilitate interdisciplinary collaborations and partnerships that can lead to innovative solutions to complex problems.

When to Write Research Paper

Research papers are typically written when a person has completed a research project or when they have conducted a study and have obtained data or findings that they want to share with the academic or professional community. Research papers are usually written in academic settings, such as universities, but they can also be written in professional settings, such as research organizations, government agencies, or private companies.

Here are some common situations where a person might need to write a research paper:

- For academic purposes: Students in universities and colleges are often required to write research papers as part of their coursework, particularly in the social sciences, natural sciences, and humanities. Writing research papers helps students to develop research skills, critical thinking skills, and academic writing skills.

- For publication: Researchers often write research papers to publish their findings in academic journals or to present their work at academic conferences. Publishing research papers is an important way to disseminate research findings to the academic community and to establish oneself as an expert in a particular field.

- To inform policy or practice : Researchers may write research papers to inform policy decisions or to improve practice in various fields. Research findings can be used to inform the development of policies, guidelines, and best practices that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- To share new insights or ideas: Researchers may write research papers to share new insights or ideas with the academic or professional community. They may present new theories, propose new research methods, or challenge existing paradigms in their field.

Purpose of Research Paper

The purpose of a research paper is to present the results of a study or investigation in a clear, concise, and structured manner. Research papers are written to communicate new knowledge, ideas, or findings to a specific audience, such as researchers, scholars, practitioners, or policymakers. The primary purposes of a research paper are:

- To contribute to the body of knowledge : Research papers aim to add new knowledge or insights to a particular field or discipline. They do this by reporting the results of empirical studies, reviewing and synthesizing existing literature, proposing new theories, or providing new perspectives on a topic.

- To inform or persuade: Research papers are written to inform or persuade the reader about a particular issue, topic, or phenomenon. They present evidence and arguments to support their claims and seek to persuade the reader of the validity of their findings or recommendations.

- To advance the field: Research papers seek to advance the field or discipline by identifying gaps in knowledge, proposing new research questions or approaches, or challenging existing assumptions or paradigms. They aim to contribute to ongoing debates and discussions within a field and to stimulate further research and inquiry.

- To demonstrate research skills: Research papers demonstrate the author’s research skills, including their ability to design and conduct a study, collect and analyze data, and interpret and communicate findings. They also demonstrate the author’s ability to critically evaluate existing literature, synthesize information from multiple sources, and write in a clear and structured manner.

Characteristics of Research Paper

Research papers have several characteristics that distinguish them from other forms of academic or professional writing. Here are some common characteristics of research papers:

- Evidence-based: Research papers are based on empirical evidence, which is collected through rigorous research methods such as experiments, surveys, observations, or interviews. They rely on objective data and facts to support their claims and conclusions.

- Structured and organized: Research papers have a clear and logical structure, with sections such as introduction, literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. They are organized in a way that helps the reader to follow the argument and understand the findings.

- Formal and objective: Research papers are written in a formal and objective tone, with an emphasis on clarity, precision, and accuracy. They avoid subjective language or personal opinions and instead rely on objective data and analysis to support their arguments.

- Citations and references: Research papers include citations and references to acknowledge the sources of information and ideas used in the paper. They use a specific citation style, such as APA, MLA, or Chicago, to ensure consistency and accuracy.

- Peer-reviewed: Research papers are often peer-reviewed, which means they are evaluated by other experts in the field before they are published. Peer-review ensures that the research is of high quality, meets ethical standards, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

- Objective and unbiased: Research papers strive to be objective and unbiased in their presentation of the findings. They avoid personal biases or preconceptions and instead rely on the data and analysis to draw conclusions.

Advantages of Research Paper

Research papers have many advantages, both for the individual researcher and for the broader academic and professional community. Here are some advantages of research papers:

- Contribution to knowledge: Research papers contribute to the body of knowledge in a particular field or discipline. They add new information, insights, and perspectives to existing literature and help advance the understanding of a particular phenomenon or issue.

- Opportunity for intellectual growth: Research papers provide an opportunity for intellectual growth for the researcher. They require critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity, which can help develop the researcher’s skills and knowledge.

- Career advancement: Research papers can help advance the researcher’s career by demonstrating their expertise and contributions to the field. They can also lead to new research opportunities, collaborations, and funding.

- Academic recognition: Research papers can lead to academic recognition in the form of awards, grants, or invitations to speak at conferences or events. They can also contribute to the researcher’s reputation and standing in the field.

- Impact on policy and practice: Research papers can have a significant impact on policy and practice. They can inform policy decisions, guide practice, and lead to changes in laws, regulations, or procedures.

- Advancement of society: Research papers can contribute to the advancement of society by addressing important issues, identifying solutions to problems, and promoting social justice and equality.

Limitations of Research Paper

Research papers also have some limitations that should be considered when interpreting their findings or implications. Here are some common limitations of research papers:

- Limited generalizability: Research findings may not be generalizable to other populations, settings, or contexts. Studies often use specific samples or conditions that may not reflect the broader population or real-world situations.

- Potential for bias : Research papers may be biased due to factors such as sample selection, measurement errors, or researcher biases. It is important to evaluate the quality of the research design and methods used to ensure that the findings are valid and reliable.

- Ethical concerns: Research papers may raise ethical concerns, such as the use of vulnerable populations or invasive procedures. Researchers must adhere to ethical guidelines and obtain informed consent from participants to ensure that the research is conducted in a responsible and respectful manner.

- Limitations of methodology: Research papers may be limited by the methodology used to collect and analyze data. For example, certain research methods may not capture the complexity or nuance of a particular phenomenon, or may not be appropriate for certain research questions.

- Publication bias: Research papers may be subject to publication bias, where positive or significant findings are more likely to be published than negative or non-significant findings. This can skew the overall findings of a particular area of research.

- Time and resource constraints: Research papers may be limited by time and resource constraints, which can affect the quality and scope of the research. Researchers may not have access to certain data or resources, or may be unable to conduct long-term studies due to practical limitations.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

- +91 8287801801

- [email protected]

Research Paper | Book Publication | Collaborations | Patent

- Research Paper

- Book Publication

- Collaboration

- SCIE, SSCI, ESCI, and AHCI

How to Write a Research Article: A Comprehensive Guide

Writing a Research Article can be an unbelievably daunting task, but it is a vital skill for any researcher or academic. This blog post intends to provide a detailed instruction on how to create a Research Paper. It will delve into the crucial elements of a Research Article, including its format, various types, and how it differs from a Research Paper. By following the steps provided, you will get vital insights on how to write a well-structured and successful research piece. Whether you are a student, researcher, or professional writer, this article will help you understand the key components required to produce a high-quality Research article.

Table of Content

What is a research article .

A Research Article is a written document that represents the findings of original and authentic research. It is typically published in a peer-reviewed academic journal and is used to communicate new knowledge and ideas to the research community. Research Articles are often used as a basis for further research and are an essential part of scientific discourse.

Components of a Research Article

A Research Article typically consists of the following components:

- Abstract – A summary of the research article, including the research question, methodology, results, and conclusion.

- Introduction – This is an explanation of the purpose behind conducting the study, and a summary of the methodology adopted for the research. This section serves as the foundation of the research article and provides the reader with a contextual background for understanding the study’s objectives and methodology. It basically outlines the reason for conducting the research and provides a glimpse of the approach that will be used to answer the research question.

- Literature Review – This section entails a comprehensive examination of the relevant literature that offers a framework for the research question and presents the existing knowledge on the subject.

- Methodology – This section explains the study’s research design, data gathering, and analysis methods.

- Results – A description of the findings of the research.

- Discussion – An interpretation of the results, including their significance and implications, as well as a discussion of the limitations of the study.

- Conclusion – A summary of the research findings, their implications, and recommendations for future research.

Research Article Format

A Research Article typically follows a standard format including:

- Title : A clear and concise title that accurately reflects the research question.

- Authors : A list of authors who contributed to the research.

- Affiliations : The institutions or organizations that the authors are affiliated with.

- Abstract : A summary of the research article.

- Keywords : A list of keywords that describe the research topic.

- Introduction : A fine background of the research question and a complete overview of the methodology used.

- Literature Review : A review of the relevant literature.

- Methodology : A description of the research design, data collection, and analysis methods used.

- Results : A description of the findings of the research.

- Discussion : An interpretation of the results and their implications, as well as a discussion of the limitations of the study.

- Conclusion: A summary of the research findings and recommendations for future research.

Types of Research Articles

There are several types of research articles including:

- Original Research Articles : These are articles that report on original research.

- Review articles : These are articles that summarize and synthesize the findings of existing research.

- Case studies : These are articles that describe and analyze a specific case or cases.

- Short communications : These are brief articles that report on original research.

Research Article vs Research Paper

While research articles and Research Papers are often used interchangeably, there are some differences between the two. A research article is typically a formal, peer-reviewed document that presents the findings of original research. A research paper, on the other hand, is a broader term that can refer to any written work that presents the findings of research, including essays, reports, and dissertations.

Example of a Research Article

Here is an example of a research article:

- Title: The effects of exercise on mental health in older adults.

- Abstract : This study investigated the effects of exercise on mental health in older adults. A sample of 100 participants aged 65 and over were randomly assigned to an exercise or control group. The exercise group participated in a 12-week exercise program, while the control group received no intervention. The results showed that the exercise group had significantly lower levels of depression and anxiety compared to the control group. Additionally, the exercise group reported higher levels of well-being and satisfaction with life. These findings suggest that exercise can be an effective intervention for improving mental health in older adults.

- Introduction: Mental health issues such as depression and anxiety are common among older adults and can have a significant impact on quality of life. Exercise has been shown to have numerous physical health benefits, but its effects on mental health in older adults are less clear. This study aimed to investigate the effects of exercise on mental health outcomes in older adults.

- Literature Review: Previous research has suggested that exercise can improve mental health outcomes in older adults. For example, a study by Mather et al. (2016) found that a 12-week exercise program resulted in significant improvements in depression and anxiety in a sample of older adults. Similarly, a meta-analysis by Smith et al. (2018) found that exercise interventions were associated with improvements in various mental health outcomes, including depression and anxiety, in older adults.

- Methodology: A total of 100 participants aged 65 and over were recruited from a community centre and randomly assigned to an exercise or control group. The exercise group participated in a 12-week exercise program consisting of three 60-minute sessions per week. The program included a combination of aerobic and resistance exercises. The control group received no intervention. Both groups completed measures of depression, anxiety, well-being, and satisfaction with life at baseline and at the end of the 12-week period.

- Results: The results showed that the exercise group had significantly lower levels of depression and anxiety compared to the control group at the end of the 12-week period. Additionally, the exercise group reported higher levels of well-being and satisfaction with life. There were no significant differences between the groups in terms of physical health outcomes.

- Discussion: These findings provide support for the use of exercise as an intervention for improving mental health outcomes in older adults. The results suggest that a 12-week exercise program can lead to significant reductions in depression and anxiety, and improvements in well-being and satisfaction with life. It is important to note, however, that the study had some limitations, including a relatively small sample size and a lack of long-term follow-up. Further research is needed to confirm these findings and explore the potential mechanisms underlying the effects of exercise on mental health in older adults.

This study provides evidence that exercise can be an effective intervention for improving mental health outcomes in older adults. Given the high prevalence of mental health issues in this population, exercise programs may be an important tool for promoting well-being and improving quality of life. Further research is needed to determine the optimal duration, intensity, and type of exercise for improving mental health outcomes in older adults.

Share this Article

Send your query, leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

"Can't find your paper? Let us help! Fill out our form and get one step closer to success."

Related tags.

- abstract in research paper article writing services Components of a Research Article Example of a Research Article how to publish a research paper how to write a research article latest research articles published research articles Research Article research article format Research Article vs Research Paper research article writing research articles Research articles topics research paper format Research Paper Publication types of research articles

Related Blogs

Exploring the DOAJ: World of Open Access Journals

Table of Content Introduction to DOAJ In the ever-evolving landscape of academic research, open access journals play a pivotal role in the global dissemination of

Welcome to The World of Fiction and Nonfiction Books

Table of Content Introduction In the vast realm of literature, books come in two primary forms: fiction and nonfiction. These distinct genres serve different purposes,

The Distinctions Between Conference Papers and Research Papers

Table of Content Introduction In the realm of academia, the terms “conference papers” and “research papers” are often used interchangeably, creating confusion among researchers, students,

UGC Care Guidelines for Research Paper Publication: Quality and Recognition

Table of Content Introduction Publishing research papers is a crucial step in establishing one’s credibility and contributing to the body of knowledge in any field.

Journal Categories

Aimlay is a top-notch Educational and Writing service platform for the last 13 years. Our team of experienced professionals is dedicated to providing you with the highest quality services to ensure that your work is published in reputable national and international indexed journals, and other scholarly works.

Quick links, useful links, blog categories.

- +91 8287 801 801

- 412, Fourth Floor, D Mall, Bhagwan Mahavir Marg, Swarn Jayanti Park, Sector 10, Rohini, Delhi, 110085

Copyright © 2023 AIMLAY

Javascript not detected. Javascript required for this site to function. Please enable it in your browser settings and refresh this page.

PublishingState.com

How to Write a Research Article

Table of contents, introduction, strategies for selecting a research topic, conducting preliminary research, conducting thorough research and literature review, the vital role of literature reviews, incorporating quality sources, examples of strong thesis statements, refining and revising the thesis statement, structuring the research article: creating an outline, writing the initial draft of the research article, the importance of an engaging introduction, framing the research question and context, creating an opening hook, developing a persuasive body of text.

Research articles are the primary means of communicating new research findings in academia. They advance knowledge within a field by presenting original studies that address research gaps or questions. Understanding how to structure and write a compelling research article properly is thus an essential skill for scholars.

The main purpose of a research article is to disseminate new data, theories, or perspectives on a topic to the scholarly community. By detailing the methodology and results of an original study, research articles validate the findings and allow others to evaluate, build upon, replicate, or refute the research. Strong research articles withstand rigorous peer review and add to the cumulative knowledge of a discipline.

Beyond communicating information, research articles also play a key role in furthering an academic career. Having research published, especially in prestigious journals, can bolster a scholar’s reputation and influence. The number and impact of research articles are often considered in hiring, promotion, and tenure decisions as measures of research productivity and contribution to one’s field.

While formats vary across disciplines, most research articles contain the same key sections: an introduction to frame the research topic and questions, a comprehensive review of relevant literature, an explanation of the methodology used in the study, a presentation of the results and data analysis, and a discussion of the implications of the findings.

Organizing the article clearly around these standard sections makes the research process and findings more accessible to readers. Additional elements like an abstract summarizing the article, properly formatted references, and well-labeled tables, graphs, and appendices characterize a well-structured article.

Employing clear, formal, and discipline-specific language is critical for accurately conveying complex information to an academic audience. Terminology and phrasing should allow readers to grasp the research design and results readily.

Likewise, research articles demand meticulous attention to detail regarding citations, data analysis, and the accurate representation of findings. Any errors or misleading statements threaten the validity of the research. Adhering to scholarly ethics in writing research articles is paramount.

By mastering the foundations of strong research article writing, including structure, language use, and integrity, scholars can effectively share their work while advancing knowledge for the betterment of their discipline.

Choosing a Compelling Research Topic

Selecting an intriguing and meaningful research topic is a crucial first step in crafting an impactful research article. The topic sets the foundation for the entire study, so researchers must choose wisely to align with their academic interests and goals. By conducting thorough preliminary research and identifying gaps in existing literature, scholars can refine their topics to offer original contributions.

When selecting a compelling research topic, choosing an area that genuinely captivates your curiosity and connects with your broader scholarly ambitions is crucial. Reflect on your academic journey thus far—what subjects or questions have consistently captured your attention?

Leveraging existing passions will sustain motivation during the lengthy research process. It also helps to assess your resources and access to data sources relevant to potential topics. A fruitful research topic aligns with available materials to facilitate a smooth investigation. Discuss prospective topics with mentors and colleagues to gain valuable outside perspectives on viability and contribution.

After identifying a broad domain of interest, delving into preliminary research helps sharpen the focus of your chosen topic. A thoughtful topic reflects careful consideration of existing literature to pinpoint meaningful gaps prime for exploration. Scan recent publications to assess the current state of research related to your initial area of interest.

Take notes on relevant theories, landmark studies, open questions, and methodological approaches. Gradually narrow down the scope of your topic as patterns emerge in the literature. Conducting preliminary research ensures your final topic offers an original perspective and advances scholarly understanding in your field.

For research to have a lasting impact, the topic must strive to enhance, expand upon, or challenge current academic discourse in some capacity. Seek out aspects of your broader research area that seem understudied or reflect oversights in dominant theoretical models. Consider diverging from mainstream topics to give voice to marginalized viewpoints.

Innovative topics that shift existing paradigms can profoundly influence how scholars approach certain phenomena. In applied fields, topics addressing unsolved real-world problems demonstrate great social value. Ultimately, selecting a research topic that meaningfully addresses gaps in understanding or practice will amplify the potential contributions of your work.

Comprehensive research is a critical first step in writing a strong research article. This involves gathering relevant sources, data, and background information to situate your study within the existing scholarly discourse. Here are some tips for conducting effective research:

- Cast a wide net: Search top journal databases , libraries, and reputable journals for a broad range of sources related to your topic. Look for seminal works, recent studies, relevant theories and frameworks, and gaps in the literature. Take detailed notes and keep track of bibliographic information for all sources you review.

- Refine and filter: Once you have a broad base of sources, begin evaluating their credibility, relevance, and significance to your specific research aims. Synthesize connections between sources and summarize the most timely, salient, and credible references to ground your study.

- Critically analyze: Read and analyze your sources actively and critically. Look for limitations, biases, assumptions, and gaps that may inform your research. Take detailed notes on the content and the research methodologies used to inform your methods.

A literature review involves synthesizing previous research related to your topic or question. An effective literature review:

- Demonstrates your knowledge of the field and seminal works

- Highlights important theories, models, and frameworks

- Reveals gaps, limitations, biases, or areas in need of further inquiry

- Identifies your study within the ongoing scholarly conversation

Use your review of existing literature to provide context and rationale for your research aims, questions, and hypotheses. Refer to key sources in your literature review throughout your article to ground your ideas in established knowledge.

When writing your research article, thoughtfully incorporate evidence from credible primary and secondary sources. Use citations judiciously to substantiate claims, frame ideas, or provide context. Integrate visuals, statistics, and direct quotes seamlessly to enhance analysis without over-relying on external sources. Synthesize information from quality sources to contribute uniquely to the scholarly discourse.

Crafting a Strong Thesis Statement

A well-formulated thesis statement is the foundation of a compelling research article. It clearly defines the central argument or premise of the study while providing direction for the analysis and discussion to follow. An effective thesis statement generally has several key characteristics:

- It concisely states the main claim or assertion: A strong thesis statement delineates the specific argument or claim in concise, precise language rather than overly broad or vague. This helps focus the scope of the research by establishing parameters for what will and will not be examined.

- It introduces the key concepts or variables being studied: The terms, ideas, relationships, and phenomena that will form the crux of the analysis should be incorporated into the thesis statement. This orientates readers to the key variables and concepts underpinning the research.

- It implies a cause-and-effect relationship: A compelling thesis suggests a causal link between concepts or variables rather than simply stating a fact. This causal relationship generally forms the basis for the arguments elaborated on in the body of the research article.

- It can be tested or explored through analysis: An effective thesis provides a hypothesis or claim that can be supported or refuted through evidence-based analysis. This engages readers by suggesting the research will yield intriguing revelations.

Here are some examples of precisely worded thesis statements:

- The implementation of stringent gun control policies in developed nations correlates with lower homicide rates over ten years.

- Public health campaigns that use positive emotional framing are more effective at changing high-risk behavioral patterns than those relying on fear or negative messaging.

- Cryptocurrency adoption has grown rapidly in developing countries with high inflation rates and unstable fiat currencies.

It is important to continually revisit and revise the thesis statement throughout the writing process. As the arguments and analysis evolve, the main claim may need adjustment to reflect the research content accurately. Ask the following questions when revising:

- Is my central assertion clearly distinguished from other claims being made?

- Does it establish an arguable premise that lends itself to testing and exploration?

- Is it specific enough to determine the scope and limits of my analysis?

- Does it imply a causal relationship that forms the basis of my arguments?

Refining the thesis statement in this manner is crucial for maintaining the coherence and direction of the research article.

A clear outline is crucial for organizing ideas and structuring a compelling research article. An outline serves as a roadmap that guides the writing process from start to finish. Here are some key tips for crafting an effective outline:

- Use the standard framework: Most research articles follow a standard format consisting of an introduction, methods, results, and discussion/conclusion. When outlining, map out the key points to cover in each of these sections. Consider what background context needs to be provided, how to summarize the study design and procedures, what data/findings to highlight, and what conclusions can be drawn.

- Organize ideas logically: Ensure your outline has a logical flow of ideas by grouping related points under headings and subheadings. Use numbering/bullet points to structure sequences. Logical organization strengthens the arguments made and enhances readability.

- Flesh out details under each main point: Under each heading, include 2-3 key points that support that topic. Adding some detail at the outlining stage helps to map out the content and prevents important points from being missed later. Leave room for expansion when drafting the full article.

- Pay attention to transitions between sections: When outlining, consider how to transition smoothly between different article sections. Think about sentences that conclude one section and introduce the next. Well-connected sections improve flow.

An organized, thoughtful outline lays the groundwork for an impactful research article. Allowing time for effective planning and structuring of ideas pays dividends when sitting down to write the first draft.

Drafting a research article’s initial version can be challenging. Breaking it down into manageable steps makes the writing process more approachable. Here is some practical advice on how to get started:

- Brainstorm and outline first: Before writing full paragraphs, brainstorm key ideas and organize them into an outline. An outline provides a roadmap that makes the initial drafting stage far less intimidating. Use the research article’s thesis and main arguments to structure the outline.

- Write without self-editing: The first draft should focus on getting ideas down on paper without self-editing along the way. Self-editing can bog writers down as they second-guess word choice and phrasing. Instead, make the first draft about expressing core ideas, even if the writing is rough. Resist the urge to obsess over small details at this stage.

- Incorporate supporting evidence: While drafting the research article’s first version, bring evidence and analysis to back up key claims. This supporting information will later be crucial for constructing a persuasive argument. Sources to draw from include research data, relevant theories, expert opinions, statistics, case studies, and real-world examples. Build the first draft around this evidence.

By following these helpful tips on brainstorming, avoiding editing pitfalls, and substantiating ideas, scholars can overcome writer’s block and make steady progress on that all-important first draft. The key is to break the intimidating writing process down into smaller, more manageable steps.

Crafting a Captivating Introduction

The introduction is the first thing readers see when they open a research article. As such, it plays a pivotal role in capturing attention and drawing readers into the piece. An engaging introduction piques curiosity, establishes relevance, and motivates readers to continue reading. This section offers strategies for crafting an introduction that hooks readers and compels them to dive into the research.

The introduction sets the stage for the entire research article. A dull or unfocused introduction can cause readers to lose interest quickly. On the other hand, an intriguing introduction sparks curiosity and entices readers to learn more. Key reasons an engaging introduction matters include:

- It is often the first section readers see, so it must capture attention immediately.

- It shapes initial impressions about the research quality and importance.

- An interesting hook encourages readers to invest time in reading further.

An engaging introduction gives a distinct edge in a sea of academic articles competing for readers’ limited time.

The introduction should frame the research question and establish an overall context for readers. Strategies to accomplish this include:

- Succinctly state the research problem or gap in current knowledge.

- Articulate the purpose and nature of the study.

- Provide relevant background details so readers understand the research context.

- Briefly discuss existing literature and how this study builds on or departs from it.

Framing the research clearly and contextualized allows readers to grasp its purpose and significance.

An opening hook instantly intrigues readers. Effective hook types include:

- An interesting anecdote or story

- A thought-provoking question

- An attention-grabbing statistic

- A striking quote

- A paradox or unexpected contrast

The tone should entice further reading without sensationalism. The goal is to stimulate the reader’s interest in learning more, not dramatic exaggeration.

The body of a research article is where authors present their key arguments, analysis, evidence, and findings. Structuring this section effectively is crucial for conveying complex ideas persuasively. Here are some tips:

- Structuring and developing the body: Organize the body into logical sections that flow well together. Each section should focus on one main idea or finding that supports your thesis. Use transition sentences between paragraphs and sections to guide readers. When presenting data or evidence, properly contextualize figures and tables so readers understand how they fit your arguments.

- Use clear and coherent language: Write clearly and precisely, defining key terms helpful. Break down complex concepts into understandable explanations that general audiences can comprehend. Use plain, straightforward language instead of overly academic or technical jargon. Summarize statistical analysis and results in an accessible way for those less familiar with the methodologies.

- Integrate citations, data, and visuals: Use in-text citations to support statements with reputable sources. Quote or paraphrase subject matter experts where appropriate. Include properly formatted references. Supplement arguments by incorporating relevant data such as statistics, survey results, or experimental findings. Visualize data through graphs, charts, diagrams, or images when helpful for reader comprehension. The judicious use of citations, data, and graphics reinforces the credibility of your analysis.

By keeping these tips in mind when structuring the body of your research article, you can craft a persuasive text that conveys key ideas to convince readers of your arguments and conclusions.

We have delved into how to write a research article. Crafting a research article is a meticulous process that requires a clear understanding of the subject matter, a structured approach, and an unwavering commitment to scholarly standards. Starting with a comprehensive literature review, researchers set the stage for presenting new findings within the context of existing knowledge.