- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Business Operations Management

What I Learned in Operations Management: Insights and Perspectives

Table of contents, introduction, strategic importance of operations, efficiency vs. effectiveness, process design and improvement, supply chain dynamics, capacity planning and resource allocation, managing quality and customer satisfaction, decision-making in uncertainty, technology and innovation, collaboration and communication.

*minimum deadline

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below

- Business Insider

- Employee Engagement

- Democratic Leadership

Related Essays

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

The 7 Greatest Leadership Lessons I’ve Learned

by Therese Fauerbach

Leadership Lessons I’ve Learned Everyone can help you learn something. Managers and leaders are different. Leadership is hard. Self-awareness is essential. Get feedback from your network. Communicate. Be present.

As CEO and founder of The Northridge Group, I am both an entrepreneur and a leader. Every day I am focused on helping business leaders solve critical problems as well as running my own company. Through management consulting, I have been exposed to a diverse range of organizations, functional groups, and cultures. Collectively, these experiences and people have contributed to the person and business leader I am today. Occasionally, peers and up-and-comers alike will ask me for my perspective on leadership. Today, I want to share a few of the greatest leadership lessons I have learned throughout my career.

1. Everyone can help you learn something.

It goes without saying that everyone has their own style of leadership, their own personal brand. Observing how others handle themselves – peers, management, and other external leaders – is a great way to learn. Whether you agree with how a situation is handled or not, the experience can teach you how to approach a similar issue in the future. Leadership is a constant assessment and reevaluation, so the more you can learn from the experiences of others – good or bad– the better off you’ll be when you’re positioned to make the decisions.

2. Managers and leaders are different.

It took me twenty years to sum up what makes a good leader versus a good manager , and the best example I can come up with is to describe a former boss of mine. This person was so charismatic that everyone would follow him to the ends of the earth. Though day-to-day operations were almost impossible for him, at times of crisis, he was the person everyone called to help solve the problem. Many times a really good manager can knock your socks off with their results, but they might not be a leader. The difference comes down to being comfortable with assessing and taking risks coupled with the ability to ignite action in others. In a crisis or at any time of need, a leader doesn’t hesitate at all – in fact, crises are where leaders often emerge. But remember, whether you are a leader or a manager, these are both essential and complementary skill sets.

3. Leadership is hard .

A good leader can push through fear, assess risk and take action when action is required. At times, the tough decisions leaders make are the ones that others cannot make. A close friend of mine was an executive in the liquor industry and one of the early crusaders for creating ads against teen drinking. It’s hard to imagine anyone challenging this today but at the time, he was met with criticism and push-back. Rather than retreat or shy away, he took a strong stance on an important issue and pushed forward. Leadership is hard and you are going to make decisions that other people can’t. Understand your values and prioritize them.

4. Self-awareness is essential.

Everyone needs a balanced and honest view of their strengths and weaknesses. Self-awareness grants a person the ability to interact with others frankly and confidently. In order to build a successful team to lead, leaders must be so aware of their weaknesses that they can hire against them. Know where you soar and where you need more help.

5. Get feedback from your network.

I often speak to the value of networking . An outside perspective can bring fresh insight when you need to workshop a new idea or you enter new territory. Furthermore, I recommend getting a broad-based perspective. It’s not always the “whos-who” that can give you the greatest insight, so reach out to a variety of demographics to get a more holistic view.

6. Communicate.

Communication is a lot like cooking to me. Tread too lightly and your message will be too bland. Use too much heat and people won’t be able to digest. You need to speak clearly enough to get your point across as well as a balanced delivery of firm and delicate messaging. Leaders need strong, clear messaging to get the results they want. If you aren’t seeing the results, stop talking and find a new approach. Learn the needs and motivations of your key stakeholders. Determine how to better position your message to reach the desired actions and results.

7. Be present.

Bring vision and strategy to the here and now. A leader needs to be able to communicate with frontline staff without de-positioning management, but you also need to be able to connect. It’s important to engage with all levels because there will be a different perspective from each operational group and level. Business is becoming more moment-to-moment than ever before. It’s more difficult to execute on long-term planning because we need constant re-evaluation to be relevant with the times. Leaders need to be present, listening and open to learning from everyone around them.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Get unique business management insights delivered straight to your inbox.

©2023 Northridge Group | Sitemap | Privacy Policy

Linkedin Facebook Twitter Apple Podcasts Spotify

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading Change and Organizational Renewal

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

7 Strategies for Improving Your Management Skills

- 09 Jan 2020

Developing managerial skills is important for all professionals. According to the World Economic Forum , people management is one of the top 10 skills needed to thrive in today’s workforce. Additionally, research by Gallup shows companies with talented managers experience greater profitability, increased levels of productivity, and higher employee engagement scores—highlighting how vital management is to an organization’s culture and success.

Whether you’re an aspiring or seasoned manager, there are actions you can take to improve how you oversee and guide people, products, and projects. Here are seven ways to become a better manager and advance your career.

Access your free e-book today.

How to Improve Your Management Skills

1. strengthen your decision-making.

Sound decision-making is a crucial skill for managers. From overseeing a team to leading a critical meeting , being an effective manager requires knowing how to analyze complex business problems and implement a plan for moving forward.

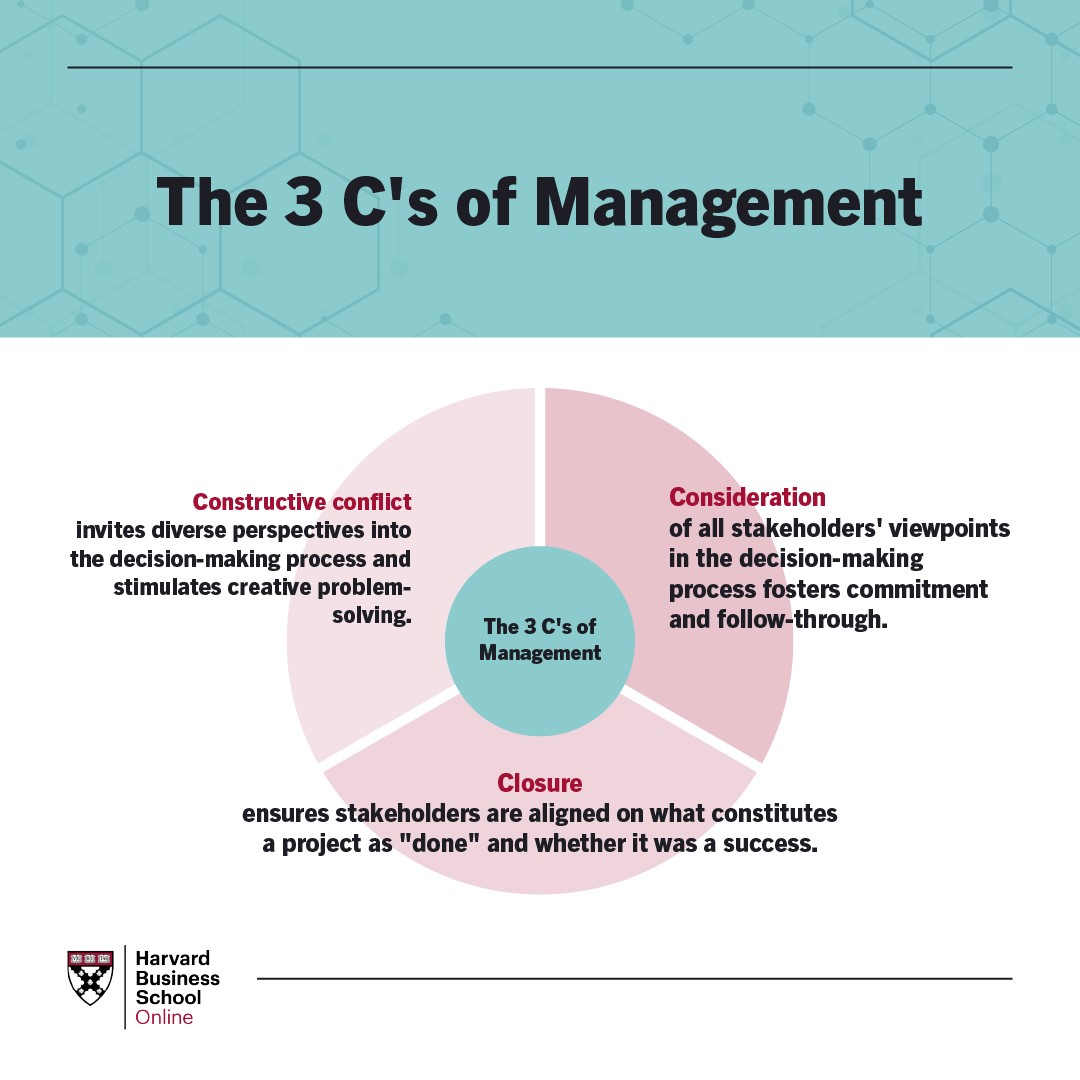

In the online course Management Essentials , the following components—referred to as the “three C’s”—are presented as essential building blocks for a successful decision-making process:

- Constructive conflict: This involves engaging team members in the decision-making process. It invites diverse perspectives and debate and stimulates creative problem-solving.

- Consideration: All stakeholders involved in a decision should feel their viewpoints were fairly considered before a solution is determined. Without this sense of acknowledgment, they may be less inclined to commit to and implement the solution.

- Closure: This is a function that ensures stakeholders are aligned before proceeding. It requires defining what constitutes a project or initiative as “done” within a set period, determining if anything remains to be accomplished, and ensuring everyone agrees as to whether the outcome was a success.

By ensuring your decision-making process encompasses these qualities, you can become a key contributor at your organization and influence the context in which decisions get made.

2. Cultivate Self-Awareness

A high level of self-awareness is critical for managers, and it’s what separates high-performers from their peers in the workplace.

This core tenet of emotional intelligence requires introspection and an honest evaluation of your strengths and weaknesses. Through engaging in self-assessment and turning to trusted colleagues to gain insight into your managerial tendencies, you can chart a path for your professional development that hones in on areas where you need to improve, enabling you to bring out the best in yourself and others.

Related: Emotional Intelligence Skills: What They Are & How to Develop Them

3. Build Trust

Trust reaps numerous benefits in the workplace. According to research outlined in the Harvard Business Review , employees at high-trust companies report:

- Less stress

- More energy at work

- Higher productivity

- Greater engagement

Forge deeper connections with your colleagues by engaging in small talk before meetings and learning more about their lives outside the scope of their work. In addition, encourage inclusive dialogue about personal and professional differences, and be open to diverse viewpoints in discussions.

Doing so can cultivate empathy among your team , leading to a greater sense of camaraderie, belonging, and motivation.

Related: 6 Tips for Managing Global Teams

4. Be a Better Communicator

Strong communication skills are a hallmark of any successful manager. Being in a managerial role involves tackling complex business situations and ensuring your team has the information and tools required to succeed.

When facing challenges like navigating organizational change , be transparent about tasks at hand and instill your team with a shared vision of how your company can benefit from the impending transition. Continually provide updates and reiterate the plan for moving forward to ensure your employees are aligned and understand how their work factors into larger corporate objectives. By developing communication and other interpersonal skills, you’ll set your team up for success.

5. Establish Regular Check-ins

Make it a habit to regularly check in with your employees outside of their annual performance reviews. According to research by Gallup , team members whose managers provide weekly feedback are over:

- Five times more likely to strongly agree they receive meaningful feedback

- Three times more likely to strongly agree they’re motivated to do outstanding work

- Two times more likely to be engaged at work

Keep the conversation informal when delivering feedback , and focus on the person’s progress toward organizational goals rather than their personality. In addition, help them chart a plan for moving forward, and affirm your role as a trusted advisor as they tackle next steps.

6. Carve Out Time for Reflection

Beyond regular check-ins, set a consistent cadence for reflecting on and reviewing your team’s work. In one study by Harvard Business School professors Francesca Gino and Gary Pisano, it was found that call center employees who spent 15 minutes reflecting at the end of the workday performed 23 percent better after 10 days than those who did not.

In a video interview for Management Essentials , HBS Professor Amy Edmondson says reflection is crucial to learning.

“If we don’t have the time and space to reflect on what we’re doing and how we’re doing it, we can’t learn,” Edmondson says. “In so many organizations today, people just feel overly busy. They’re going 24/7 and think, ‘I don’t have time to reflect.’ That’s a huge mistake, because if you don’t have time to reflect, you don’t have time to learn. You’re going to quickly be obsolete. People need the self-discipline and the collective discipline to make time to reflect.”

Schedule reflection sessions shortly after the completion of an initiative or project and invite all members of your team to participate, encouraging candor and debate. Hone in on problems and issues that can be fixed, and plot a corrective action plan so that you don’t encounter the same pitfalls in your upcoming undertakings.

7. Complete Management Training

Beyond your daily work, furthering your education can be an effective way to bolster your management skills.

Through additional training , such as an online management course , you can learn new techniques and tools that enable you to shape organizational processes to your advantage. You can also gain exposure to a network of peers with various backgrounds and perspectives who inform your managerial approach and help you grow professionally.

For Raymond Porch , a manager of diversity programs at Boston Public Schools who took Management Essentials , engaging with fellow learners was the highlight of his HBS Online experience .

“My favorite part of the program was interacting with my cohort members,” Porch says. “I received valuable shared experiences and feedback and was able to be a thought partner around strategies and best practices in varying scenarios.”

Related: 5 Key Benefits of Enrolling in a Management Training Course

How Managers Become Great Leaders

While the terms “management” and “leadership” are often used interchangeably, they encompass different skill sets and goals . Yet, some of the most effective managers also exhibit essential leadership characteristics.

Characteristics of a great leader include:

- Exemplary leadership: Strong leaders often consider themselves as part of the team they manage. They’re concerned with the greater good of their organization and use delegation skills to effectively assign tasks to the appropriate team members. Just as they must provide feedback to their team, great leaders must accept others’ constructive feedback to improve their leadership style.

- Goal-oriented: It’s crucial for leaders to deeply understand their organization’s business goals. Knowing its overall mission allows them to strategically prioritize initiatives and align their team with a common vision.

- Self-motivated: It’s vital that leaders are self-motivated and use time management skills to reach their goals. They must accomplish difficult tasks while inspiring their team to follow suit.

By bolstering your leadership skills , you can strengthen your relationship with your team and empower them to do their best work, ultimately complementing your managerial skills.

Elevating Your Management Skills

Managing people and implementing projects on time and on budget is a business skill that all professionals should strive to master. Through sharpening your soft skills, building self-awareness, and continuing your education, you can gain the skills needed to excel as a manager and lead both your team and organization to success.

Do you want to become a more effective leader and manager? Explore our online leadership and management courses to learn how you can take charge of your professional development and accelerate your career. To find the right course for you, download the free flowchart .

This post was updated on September 2, 2022. It was originally published on January 9, 2020.

About the Author

- Data, AI, & Machine Learning

- Managing Technology

- Social Responsibility

- Workplace, Teams, & Culture

- AI & Machine Learning

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Big ideas Research Projects

- Artificial Intelligence and Business Strategy

- Responsible AI

- Future of the Workforce

- Future of Leadership

- All Research Projects

- AI in Action

- Most Popular

- The Truth Behind the Nursing Crisis

- Work/23: The Big Shift

- Coaching for the Future-Forward Leader

- Measuring Culture

The spring 2024 issue’s special report looks at how to take advantage of market opportunities in the digital space, and provides advice on building culture and friendships at work; maximizing the benefits of LLMs, corporate venture capital initiatives, and innovation contests; and scaling automation and digital health platform.

- Past Issues

- Upcoming Events

- Video Archive

- Me, Myself, and AI

- Three Big Points

The Processes of Organization and Management

A unifying framework for thinking about processes — or sequences of tasks and activities — that provides an integrated, dynamic picture of organizations and managerial behavior.

- Organizational Structure

Managers today are enamored of processes. It’s easy to see why. Many modern organizations are functional and hierarchical; they suffer from isolated departments, poor coordination, and limited lateral communication. All too often, work is fragmented and compartmentalized, and managers find it difficult to get things done. Scholars have faced similar problems in their research, struggling to describe organizational functioning in other than static, highly aggregated terms. For real progress to be made, the “proverbial ‘black box,’ the firm, has to be opened and studied from within.” 1

Processes provide a likely solution. In the broadest sense, they can be defined as collections of tasks and activities that together — and only together — transform inputs into outputs. Within organizations, these inputs and outputs can be as varied as materials, information, and people. Common examples of processes include new product development, order fulfillment, and customer service; less obvious but equally legitimate candidates are resource allocation and decision making.

Over the years, there have been a number of process theories in the academic literature, but seldom has anyone reviewed them systematically or in an integrated way. Process theories have appeared in organization theory, strategic management, operations management, group dynamics, and studies of managerial behavior. The few scholarly efforts to tackle processes as a collective phenomenon either have been tightly focused theoretical or methodological statements or have focused primarily on a single type of process theory. 2

Yet when the theories are taken together, they provide a powerful lens for understanding organizations and management:

First, processes provide a convenient, intermediate level of analysis. Because they consist of diverse, interlinked tasks, they open up the black box of the firm without exposing analysts to the “part-whole” problems that have plagued earlier research. 3 Past studies have tended to focus on either the trees (individual tasks or activities) or the forest (the organization as a whole); they have not combined the two. A process perspective gives the needed integration, ensuring that the realities of work practice are linked explicitly to the firm’s overall functioning. 4

Second, a process lens provides new insights into managerial behavior. Most studies have been straightforward descriptions of time allocation, roles, and activity streams, with few attempts to integrate activities into a coherent whole.

About the Author

David A. Garvin is the Robert and Jane Cizik Professor of Business Administration, Harvard Business School.

1. B.S. Chakravarthy and Y. Doz, “Strategy Process Research: Focusing on Corporate Self-Renewal,” Strategic Management Journal, volume 13, special issue, Summer 1992, pp. 5–14, quote from p. 6.

2. L.B. Mohr, Explaining Organizational Behavior (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1982); P.R. Monge, “Theoretical and Analytical Issues in Studying Organizational Processes,” Organization Science, volume 1, number 4, 1990, pp. 406–430; A.H. Van de Ven, “Suggestions for Studying Strategy Process: A Research Note,” Strategic Management Journal, volume 13, special issue, Summer 1992, pp. 169–188; and A.H. Van de Ven and G. Huber, “Longitudinal Field Research Methods for Studying Processes of Organizational Change,” Organization Science, volume 1, number 3, 1990, pp. 213–219.

3. A.H. Van de Ven, “Central Problems in the Management of Innovation,” Management Science, volume 32, number 5, 1986, pp. 590–606.

4. L.R. Sayles, Leadership: Managing in Real Organizations, second edition (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1989).

5. C.P. Hales, “What Do Managers Do?,” Journal of Management Studies, volume 23, number 1, 1986, pp. 88–115; and H. Mintzberg, The Nature of Managerial Work (New York: Harper & Row, 1973).

6. For discussions of processes in the quality literature, see: H.J. Harrington, Business Process Improvement (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1991); E.J. Kane, “IBM’s Quality Focus on the Business Process,” Quality Progress, volume 19, April 1986, pp. 24–33; E.H. Melan, “Process Management: A Unifying Framework,” National Productivity Review, volume 8, 1989, number 4, pp. 395–406; R.D. Moen and T.W. Nolan, “Process Improvement,” Quality Progress, volume 20, September 1987, pp. 62–68; and G.D. Robson, Continuous Process Improvemen (New York: Free Press, 1991). For discussions of processes in the reengineering literature, see: T.H. Davenport, Process Innovation (Boston: Harvar Business School Press, 1993); M. Hammer and J. Champy, Reengineering the Corporation (New York: Harper Business, 1993); and T.A. Stewart,”Reengineeering: The Hot New Managing Tool,” Fortune, 23 August 1993, pp. 40–48.

7. M. Hammer, “Reengineering Work: Don’t Automate, Obliterate,” Harvard Business Review, volume 68, July–August 1990, pp. 104–112.

8. J.D. Blackburn, “Time-Based Competition: White-Collar Activities,” Business Horizons, volume 35, July–August 1992, pp. 96–101.

9. E.H. Melan, “Process Management in Service and Administrative Operations,” Quality Progress, volume 18, June 1985, pp. 52–59.

10. Davenport (1993), chapter 7; Hammer and Champy (1993), chapter 3; Harrington (1991), chapter 6; and Kane (1986).

11. Hammer and Champy (1993), pp. 108–109; Kane (1986); and Melan (1989), p. 398.

12. Moen and Nolan (1987); and Robson (1991).

13. Davenport (1993), pp. 10–15; and Hammer and Champy (1993), pp. 32–34.

14. T.H. Davenport and N. Nohria, “Case Management and the Integration of Labor,” Sloan Management Review, volume 35, Winter 1994, pp. 11–23, quote from p. 11.

15. I. Price, “Aligning People and Processes during Business-Focused Change in BP Exploration,” Prism, fourth quarter, 1993, pp. 19–31.

16. Kane (1986); and Melan (1985) and (1989).

17. H. Gitlow, S. Gitlow, A. Oppenheim, and R. Oppenheim, Tools and Methods for the Improvement of Quality (Homewood, Illinois: Irwin, 1989), chapter 8.

18. P.F. Schlesinger, V. Sathe, L.A. Schlesinger, and J.P. Kotter, Organization: Text, Cases, and Readings on the Management of Organization Design and Change (Homewood, Illinois: Irwin, 1992), pp. 106–110.

19. J. Browning, “The Power of Process Redesign,” McKinsey Quarterly , volume 1, number 1, 1993, pp. 47–58; J.R. Galbraith, Organization Design (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley, 1977), pp. 118–119; and B.P. Shapiro, K. Rangan and J.J. Sviokla, “Staple Yourself to an Order,” Harvard Business Review, volume 70, July–August 1992, pp. 113–122.

20. For example, see: A. March and D.A. Garvin, “Arthur D. Little, Inc.” (Boston: Harvard Business School, case no. 9-396-060, 1995).

21. K.E. Weick, The Social Psychology of Organizing, second edition (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley, 1979), p. 34.

22. S.C. Wheelwright and K.B. Clark, Revolutionizing Product Development (New York: Free Press, 1992).

23. C.I. Barnard, The Functions of the Executive (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1938), pp. 185–189, 205–206; and H.A. Simon, Administrative Behavior, third edition (New York: Free Press, 1976), pp. 96–109, 220–228.

24. L.A. Hill, Becoming a Manager ( Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1992), pp. 20–21.

25. For reviews, see: J.L. Bower and Y. Doz, “Strategy Formulation: A Social and Political Process,” in D.H. Schendel and C.H. Hofer, eds., Strategic Management (Boston: Little, Brown, 1979), pp. 152–166; and A.S. Huff and R.K. Reger, “A Review of Strategic Process Research,” Journal of Management, volume 13, number 2, 1987, pp. 211–236.

26. H. Mintzberg, D. Raisinghani, and A. Théorêt, “The Structure of Unstructured Decision Processes,” Administrative Science Quarterly, volume 21, June 1976, pp. 246–275; P.C. Nutt, “Types of Organizational Decision Processes,” Administrative Science Quarterly, volume 29, September 1984, pp. 414–450; and E. Witte, “Field Research on Complex Decision-Making Processes — The Phase Theorem,” International Studies of Management and Organization, volume 2, Summer 1972, pp. 156–182.

27. Witte (1972), p. 179.

28. Mintzberg et al. (1976); and Nutt (1984).

29. For studies on capital budgeting, see: R.W. Ackerman, “Influence of Integration and Diversity on the Investment Process,” Administrative Science Quarterly, volume 15, September 1970, pp. 341–351; and J.L. Bower, Managing the Resource Allocation Process (Boston: Harvard Business School, Division of Research, 1970). For studies on foreign investments, see: Y. Aharoni, The Foreign Investment Decision Process (Boston: Harvard Business School, Division of Research, 1966). For studies on strategic planning, see: P. Haspeslagh, “Portfolio Planning: Uses and Limits,” Harvard Business Review, volume 60, January–February 1982, pp. 58–74; and R. Simons, “Planning, Control, and Uncertainty: A Process View,” in W.J. Bruns, Jr. and R.S. Kaplan, eds., Accounting and Management: Field Study Perspectives (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1987), pp. 339–367. For studies on internal corporate venturing, see: R.A. Burgelman, “A Process Model of Internal Corporate Venturing in the Diversified Major Firm,” Administrative Science Quarterly, volume 28, June 1983, pp. 223–244; and R.A. Burgelman, “Strategy Making as a Social Learning Process: The Case of Internal Corporate Venturing,” Interfaces, volume 18, number 3, 1988, pp. 74–85. For studies on business exit, see: R.A. Burgelman, “Fading Memories: A Process Theory of Strategic Business Exit in Dynamic Environments,” Administrative Science Quarterly, volume 39, March 1994, pp. 24–56.

30. Bower (1970).

31. G.T. Allison, Essence of Decision (Boston: Little, Brown, 1971); I.L. Janis, Victims of Groupthink (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1972); L.J. Bourgeois, III and K.M. Eisenhardt, “Strategic Decision Processes in High-Velocity Environments: Four Cases in the Microcomputer Industry,” Management Science, volume 34, number 7, 1988, pp. 816–835; K.M. Eisenhardt, “Speed and Strategic Choice: How Managers Accelerate Decision Making,” California Management Review, volume 32, Spring 1990, pp. 39–54; J.W. Fredrickson and T.R. Mitchell, “Strategic Decision Processes: Comprehensiveness and Performance in an Industry with an Unstable Environment,” Academy of Management Journal, volume 27, number 2, 1984, pp. 399–423; J.W. Fredrickson, “The Comprehensiveness of Strategic Decision Processes: Extension, Observations, Future Directions,” Academy of Management Journal, volume 27, number 4, 1984, pp. 445–466; and I. Nonaka and J.K. Johansson, “Organizational Learning in Japanese Companies,” in R. Lamb and P. Shrivastava, eds., Advances in Strategic Management, volume 3 (Greenwich, Connecticut: JAI Press, 1985), pp. 277–296.

32. Janis (1972).

33. A.C. Amason, “Distinguishing the Effects of Functional and Dysfunctional Conflict on Strategic Decision Making: Resolving a Paradox for Top Management Teams,” Academy of Management Journal, volume 39, number 1, 1996, pp. 123–148; D.M. Schweiger, W.R. Sandberg, and J.W. Ragan, “Group Approaches for Improving Strategic Decision Making,” Academy of Management Journal, volume 29, number 1, 1986, pp. 51–71; and D.M. Schweiger, W.R. Sandberg, and P.L. Rechner, “Experimental Effects of Dialectical Inquiry, Devil’s Advocacy, and Consensus Approaches to Strategic Decision Making,” Academy of Management Journal, volume 32, number 4, 1989, pp. 745–772.

34. Janis (1972), pp. 146–149.

35. Bourgeois and Eisenhardt (1988).

36. E.H. Schein, Process Consultation: Its Role in Organization Development, second edition (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley, 1988), pp. 17–19.

37. D.G. Ancona and D.A. Nadler, “Top Hats and Executive Tales: Designing the Senior Team,” Sloan Management Review, volume 31, Fall 1989, pp. 19–28; and D.C. Hambrick, “Top Management Groups: A Conceptual Integration and Reconsideration of the ‘Team’ Label,” in B.M. Staw and L.L. Cummings, eds., Research in Organizational Behavior, volume 16 (Greenwich, Connecticut: JAI Press, 1994), pp. 171–214.

38. Schein (1988), p. 21.

39. Ibid., pp. 22–39.

40. O. Hauptman, “Making Communication Work,” Prism, second quarter, 1992, pp. 71–81; and D. Krackhardt and J.R. Hanson, “Informal Networks: The Company behind the Chart,” Harvard Business Review, volume 71, July–August 1993, pp. 104–111.

41. Ancona and Nadler (1989), p. 24; Schein (1988), p. 50.

42. D. McGregor, The Professional Manager (New York: McGraw-Hill. 1967), pp. 173–174; and Schein (1988), pp. 57–58, 81–82.

43. R.L. Daft and G.P. Huber, “How Organizations Learn: A Communication Framework,” in S.B. Bacharach and N. DiTomaso, eds., Research in the Sociology of Organizations, volume 5 (Greenwich, Connecticut: JAI Press, 1987), pp. 1–36; C.M. Fiol and M.A. Lyles, “Organizational Learning,” Academy of Management Review, volume 10, number 4, 1985, pp. 803–813; G.P. Huber, “Organizational Learning: The Contributing Processes and the Literatures,” Organization Science, volume 2, number 1,1991, pp. 88–115; B. Levitt and J.G. March, “Organizational Learning,” Annual Review of Sociology, volume 14, 1988, pp. 319–340; and P. Shrivastava, “A Typology of Organizational Learning Systems,” Journal of Management Studies, volume 20, number 1, 1983, pp. 7–28.

44. P.M. Brenner, “Assessing the Learning Capabilities of an Organization” (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Sloan School of Management, unpublished master’s thesis, 1994); Daft and Huber (1987), pp. 24–28; D.A. Garvin, “Building a Learning Organization,” Harvard Business Review, volume 71, July–August 1993, pp. 78–91; Levitt and March (1988), p. 320; and E.C. Nevis, A.J. DiBella, and J.M. Gould, “Understanding Organizations as Learning Systems,” Sloan Management Review, volume 37, Winter 1995, pp. 73–85.

45. Nevis et al. (1995), p. 76.

46. T. Kiely, “The Idea Makers,” Technology Review, 96, January 1993, pp. 32–40; M.A. Cusumano and R.W. Selby, Microsoft Secrets (New York: Free Press, 1995); Garvin (1993); J. Simpson, L. Field, and D.A. Garvin, “The Boeing 767: From Concept to Production (A)” (Boston: Harvard Business School, case 9-688-040, 1988); R.C. Camp, Benchmarking (Milwaukee, Wisconsin: ASQC Quality Press, 1989); and R.E. Mittelstaedt, Jr., “Benchmarking: How to Learn from Best-in-Class Practices,” National Productivity Review, volume 11, Summer 1992, pp. 301–315; A. De Geus, “Planning as Learning,” Harvard Business Review, volume 66, March–April 1988, pp. 70–74; Huber (1991), pp. 105–107; Levitt and March (1988), pp. 326–329; and J.P. Walsh and G.R. Ungson, “Organizational Memory,” Academy of Management Review, volume 16, number 1, 1991, pp. 57–91.

47. Shrivastava (1983), p. 16.

48. Bourgeois and Eisenhardt (1988); and Eisenhardt (1990).

49. B. Blumenthal and P. Haspeslagh, “Toward a Definition of Corporate Transformation,” Sloan Management Review, volume 35, Spring 1994, pp. 101–106.

50. A.M. Pettigrew, “Longitudinal Field Research: Theory and Practice,” Organization Science, volume 1, number 3, 1990, pp. 267–292, quote from p. 270.

51. Van de Ven (1992), p. 80.

52. Van de Ven and Huber (1990).

53. C.J.G. Gersick, “Revolutionary Change Theories: A Multilevel Exploration of the Punctuated Equilibrium Paradigm,” Academy of Management Review, volume 16, number 1, 1991, pp. 10–36.

54. For studies on creation, see: D.N.T. Perkins, V.F. Nieva, and E.E. Lawler III, Managing Creation: The Challenge of Building a New Organization (New York: Wiley, 1983); S.B. Sarason, The Creation of Settings and the Future Societies (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1972); and A.H. Van de Ven, “Early Planning, Implementation, and Performance of New Organizations,” in J.R. Kimberly, R.H. Miles, and associates, The Organizational Life Cycle (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1980), pp. 83–134. For studies on growth, see: W.H. Starbuck, ed., Organizational Growth and Development: Selected Readings (Middlesex, England: Penguin, 1971). For studies on transformation, see: J.R. Kimberly and R.E. Quinn, eds., New Futures: The Challenge of Managing Corporate Transitions (Homewood, Illinois: Dow Jones-Irwin, 1984); A.M. Mohrman, Jr., S.A. Mohrman, G.E. Ledford, Jr., T.G. Cummings, E.E. Lawler III, and associates, Large-Scale Organizational Change (San-Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1989). For studies on decline, see: D.C. Hambrick and R.A. D’Aveni, “Large Corporate Failures as Downward Spirals,” Administrative Science Quarterly, volume 33, March 1988, pp. 1–23; R.I. Sutton, “Organizational Decline Processes: A Social Psychological Perspective,” in B.M. Staw and L.L. Cummings, eds., Research in Organizational Behavior, volume 12 (Greenwich, Connecticut: JAI Press, 1990), pp. 205–253; and S. Venkataraman, A.H. Van de Ven, J. Buckeye, and R. Hudson, “Starting Up in a Turbulent Environment,” Journal of Business Venturing, volume 5, number 5, 1990, pp. 277–295.

55. Gersick (1991), p. 10.

56. M. Crozier, The Bureaucratic Phenomenon (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964), p. 196; Gersick (1991); H. Mintzberg, “Patterns in Strategy Formation,” Management Science, volume 24, number 9, 1978, pp. 934–948; Starbuck (1971), p. 68; and Van de Ven (1992).

57. L.E. Greiner, “Evolution and Revolution as Organizations Grow,” Harvard Business Review, volume 50, July–August 1972, pp. 37–46; and M.L. Tushman and P. Anderson, “Technological Discontinuities and Organizational Environments,” Administrative Science Quarterly, volume 31, September 1986, pp. 439–465.

58. P. Selznick, Leadership in Administration (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1957), pp. 103–104.

59. Tushman, W.H. Newman, and E. Romanelli, “Convergence and Upheaval: Managing the Unsteady Pace of Organizational Evolution,” California Management Review, volume 29, Fall 1986, pp. 29–44.

60. R.M. Kanter, B.A. Stein, and T.D. Jick, The Challenge of Organizational Change (New York: Free Press, 1992), pp. 375–377.

61. R. Beckhard and R.T. Harris, Organizational Transitions, second edition (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley, 1987); K. Lewin, Field Theory in Social Science (New York: Harper, 1951); E.H. Schein, Professional Education (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1972), pp. 76–84; and N. Tichy and M. Devanna, The Transformational Leader (New York: Wiley, 1986).

62. A. Abbott, “A Primer on Sequence Methods,” Organization Science, volume 1, number 4, 1990, pp. 375–392; Monge (1990); A. Strauss and J. Corbin, Basics of Qualitative Research (Newbury Park, California: Sage, 1990: chapter 9; and Witte (1972).

63. C. Perrow, “A Framework for the Comparative Analysis of Organizations,” American Sociological Review, volume 32, number 2, 1967, pp. 194–208, quote from p. 195.

64. D.A. Garvin, “Leveraging Processes for Strategic Advantage, Harvard Business Review, volume 73, September–October 1995, pp. 76–90.

65. See, for example: Galbraith (1977); and Schlesinger, Sathe, Schlesinger, and Kotter (1992).

66. W.G. Astley and A.H. Van de Ven, “Central Perspectives and Debates in Organization Theory,” Administrative Science Quarterly, volume 28, June 1983, pp. 245–273, quote from p. 263.

67. C.A. Bartlett and S. Ghoshal, “Beyond the M-Form: Toward a Managerial Theory of the Firm,” Strategic Management Journal, volume 14, special issue, Winter 1993, pp. 23–46.

68. Hales (1986); Mintzberg (1973); Sayles (1989); and L.R. Sayles, Managerial Behavior (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964).

69. J. Pfeffer, “Understanding Power in Organizations,” California Management Review, volume 34, Winter 1992, pp. 29–50, quote from p. 29.

70. Crozier (1964); J.G. March, “The Business Firm as a Political Coalition,” Journal of Politics, volume 24, number 4, 1962, pp. 662–678; Sayles (1989); and M.L. Tushman, “A Political Approach to Organizations: A Review and Rationale,” Academy of Management Review, volume 2, April 1977, pp. 206–216.

71. Hales (1986); J.P. Kotter, The General Managers (New York: Free Press, 1982); Mintzberg (1973); and H.E. Wrapp, “Good Managers Don’t Make Policy Decisions,” Harvard Business Review, volume 45, September–October 1967, pp. 91–99.

72. E.M. Leifer and H.C. White, “Wheeling and Annealing: Federal and Multidivisional Control,” in J.F. Short, Jr., ed., The Social Fabric (Beverly Hills, California: Sage, 1986), pp. 223–242.

73. Hill (1992); and Kotter (1982).

74. W. Skinner and W.E. Sasser, “Managers with Impact: Versatile and Inconsistent,” Harvard Business Review, volume 55, November–December 1977, pp. 140–148.

75. Examples include The Soul of a New Machine, featuring Tom West, the leader of a project to build a new minicomputer at Data General Corporation, and My Years with General Motors, written by Alfred Sloan, who resurrected General Motors in the more than twenty years that he served as the company’s chief executive and chairman. See: J.T. Kidder, The Soul of a New Machine (Boston: Little, Brown, 1981); and A.P. Sloan, Jr., My Years with General Motors (New York: Doubleday, 1963).

76. Mintzberg (1973), p. 92; Sayles (1964), chapter 9; and Hales (1986).

77. Kotter (1982).

78. J.J. Gabarro, The Dynamics of Taking Charge (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1987); and R. Simons, “How New Top Managers Use Control Systems as Levers of Strategic Renewal,” Strategic Management Journal, volume 15, number 3, 1994, pp. 169–189.

79. Sayles (1964).

80. Hill (1992); Kotter (1982); F. Luthans, R.M. Hodgetts, and S.A. Rosenkrantz, Real Managers (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Ballinger, 1988); and Mintzberg (1973).

81. D.J. Isenberg, “How Senior Managers Think,” Harvard Business Review, volume 62, November–December 1984, pp. 80–90, quote from p. 84.

82. Sayles (1964).

83. J.E. Dutton and S.J. Ashford, “Selling Issues to Top Management,” Academy of Management Review, volume 18, number 3, 1993, pp. 397–428; and I.C. MacMillan and W.D. Guth, “Strategy Implementation and Middle Management Coalitions,” in R. Lamb and P. Shrivastava, eds., Advances in Strategic Management, volume 3 (Greenwich, Connecticut: JAI Press, 1985), pp. 233–254.

84. D.C. Hambrick and A.A. Cannella, “Strategy Implementation as Substance and Selling,” Academy of Management Executive, volume 3, number 4, 1989, pp. 278–285.

85. Mintzberg (1973), pp. 67–71; and Sayles (1964).

86. Isenberg (1984); and M.A. Lyles and I.I. Mitroff, “Organizational Problem Formulation: An Empirical Study,” Administrative Science Quarterly, volume 25, March 1980, pp. 102–119.

87. Sayles (1964), pp. 170.

88. Mintzberg (1973), pp. 67–71.

89. D.A. Schön, The Reflective Practitioner (New York: Basic Books, 1983), chapters 1, 2, and 8.

90. MacMillan and Guth (1985); and Bower and Doz (1979), pp.152–153.

91. Mohr (1982), p. 43.

92. E.D. Chapple and L.R. Sayles, The Measure of Management (New York: Macmillan, 1961), pp. 49–50.

93. Garvin (1995).

94. E.H. Schein, Process Consultation: Lessons for Managers and Consultants (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley, 1987); and Schein (1988).

Acknowledgments

More like this, add a comment cancel reply.

You must sign in to post a comment. First time here? Sign up for a free account : Comment on articles and get access to many more articles.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Anyone Can Learn to Be a Better Leader

- Monique Valcour

You just have to put in the work.

Occupying a leadership position is not the same thing as leading. To lead, you must be able to connect, motivate, and inspire a sense of ownership of shared objectives. Heightening your capacity to lead others requires being able to see how you think and act, and how your behavior affects others. Leading well requires a continuous journey of personal development. Yet people in leadership roles often eschew the long and challenging work of deepening self-insight in favor of chasing after management “tools”— preferably the “quick ’n’ easy” kind, such as personality type assessments that reduce employees to a few simplistic behavioral tendencies. Tools can be handy aids to good leadership. But none of them can take the place of fearless introspection, feedback seeking, and committed efforts to behavioral change for greater effectiveness and increased positive impact on others.

When you’re an individual contributor, your ability to use your technical expertise to deliver results is paramount. Once you’ve advanced into a leadership role, however, the toolkit that you relied on to deliver individual results rarely equips you to succeed through others. Beware of falling into the logical trap of “if I can do this work well, I should be able to lead a team of people who do this work.” This would be true if leading others were akin to operating a more powerful version of the same machinery you operated previously. But it’s not; machinery doesn’t perform better or worse based on what it thinks about you and how you make it feel, while humans do .

- MV Monique Valcour is an executive coach, keynote speaker, and management professor. She helps clients create and sustain fulfilling and high-performance jobs, careers, workplaces, and lives. moniquevalcour

Partner Center

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

In summation, the role of leadership and management can work in different capacities, yet be the same when developing an organization. Leadership is nothing if it doesn’t build a systems’ based management structure, and management would have no support without the work of leadership as the backbone of ideals.

A review of this chapter’s major conclusions, include:

- Being ethically sound and sacrificing comforts for goals and objectives (classical ideals) make leaders strive for innovation and the improvement of society (contemporary ideals).

- Developing and systematically organizing hiring philosophies, institutional policies, budgeting processes, rewards, and decision-making styles are effective measures for managing organizations into the future.

- Leadership and management are both the same and different.

- Using the iceberg analogy and the five disciplines, leadership and management are both independent and dependent from each other, especially when achieving goals in a learning organization.

To offer parting words after this journey, it is important to understand that whatever leadership or management style chosen, it has to relate to inherent beliefs. Essentially, the iceberg below the surface is not just made in one day, it is shaped and cultivated throughout life through natural and social occurrences, assumptions, and inherent beliefs. It is very important for leaders to find their own icebergs and self-reflect on what their beliefs mean to their leadership styles and how they develop their management strategies. As prospective leaders and managers in society, it is highly important to locate and cultivate a personal leadership style to become successful in a future society.

Leadership and Management in Learning Organizations Copyright © by Clayton Smith; Carson Babich; and Mark Lubrick is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.13: Management Theory and Organizational Behavior

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 48581

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

- Describe the relationship between management theory and organizational behavior

The first management theory that helped establish the foundation for organizational behavior was Taylor’s Scientific Management Theory. As we discussed earlier, Taylor placed a huge focus on productivity and worked to establish the most efficient ways to accomplish every task, big and small. Taylor’s theory impacted each organization’s productivity and it also changed the professional and personal dynamic of its employees and managers. This classical approach to management was later challenged by the onset of the human relations management movement which helped to further develop the groundwork organizational behavior.

While effective for productivity, the scientific management theory was missing a key component, human relations. In response to the classical management approach, human relations management theory was born. The Hawthorne Studies were a shining example of how much human relations and interactions can affect the workforce. A connection was finally made between productivity and the people responsible for it. The Hawthorne Studies proved that it was important for companies to take interest in their employees in order to increase productivity and decrease turnover. Not only did the studies show that individuals performed better when given attention, it also revealed that group dynamics were equally as important as individual contentment. It was becoming clear that the individual and group dynamics in an organization were equally important and directly related to the output of a company. It was through this revelation that people began to study the behavior of organizations at multiple levels; individual, group, and whole organization.

Another big impact on the development of organizational behavior was McGregor’s Theory X & Theory Y. As you read in the last section, the two theories are extremely different. Theory X states that people are inherently lazy and need to be forced to work. Theory Y on the other hand, says that people are motivated to work and argues the importance of a team dynamic. Theory Y is the more effective of the two theories and is a fundamental part of the foundation for organizational behavior.

While organizational behavior roots can be found in many management theories, it was not officially recognized as a field of its own until the 1970s. Since the 1970s, organizational behavior has developed into its own unique field covering a wide variety of topics for individual and group relations within organizations. This course will help you deep dive into the interworking of organizational behavior and help you understand how organizational behavior affects the day-to-day lives of employees in the workplace.

Practice Question

https://assessments.lumenlearning.co...essments/13680

Let’s move on to better define organizational behavior and enhance our understanding of its influence on an organization!

Contributors and Attributions

- Management Theory and Organizational Behavior. Authored by : Freedom Learning Group. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Untitled. Authored by : rawpixel. Provided by : PIxabay. Located at : pixabay.com/photos/office-business-paperwork-document-3295556/. License : CC0: No Rights Reserved . License Terms : Pixabay License

Strategic management Essay

Introduction, strategic management, diversification, viva company, strategies for entering new business, diversification strategies of sony and ge.

Strategic management is arguably one of the basic components of a successful business across the screen. What is it? How does it enhance good performance? This essay discusses the concept of strategic management by describing what it is, with regard to business management.

Additionally, the analysis will give a brief explanation of diversification and why it is necessary in business. Besides these introductory segments, the synthesis will explain the strategies of VIVA Company in the Kingdom of Bahrain and their success foundation. Importantly, strategies for entering new business will be covered, with a special reference to Sony and General Electric companies.

A strategy is conventionally described as a long-term business plan or action formulated solely for the realization of business goals and objectives. On the other hand, strategic management refers to a compilation of managerial decisions and actions, aimed at determining the long-term performance of an organization (Thompson, Strickland & Gamble, 2009).

It encompasses a wide range of concepts including but not limited to environmental scanning, formulation of strategies, implantation, evaluation and control. Similarly, the study of strategic management focuses on evaluation and assessment of an organization’s opportunities and threats in relation to its strengths and weaknesses.

Notably, strategic management has continuously evolved to become a core value, which plays a significant role in helping organizations to thrive in a multifaceted and dynamic business environment. As a result, companies are forced to become more flexible and less bureaucratic to attain competitive advantage in the market place.

This has moved from traditional ways of defining a strategy where companies were mainly concerned with defending their competitive positions. Because of changing technology and the ease of products being replaced by others, most organizations are putting a lot of emphasis on competitive advantage. It is therefore essential for organizations to have the ability to exercise strategic flexibility in to move from a dominant strategy to another (Thompson, Strickland & Gamble, 2009).

Risks exist in any business idea. As a result, there is need for organizations to establish corporate strategies to reduce these risks as much as possible. It therefore denotes an approach that allows an organization to concentrate on several investments within a single business portfolio (Thompson, Strickland & Gamble, 2009). This is based on the fact that a portfolio, which mixes numerous investments, is likely to be more profitable than that which concentrates on a single investment.

Besides higher returns, it is also believed that business diversification exposes an organization to lower financial risks as compared to businesses with single investment entities. In its practical application, diversification eliminates sources of risks in a given portfolio to allow quick neutralization of negative performance by positive ones within the portfolio (Sadler & Craig, 2003). Nevertheless, this can only be realized if there is no perfect correlation between securities within the organization.

It is worth noting that excess diversification may equally undermine the rate at which an organization experiences diversification benefits. Some schools of thought argue that foreign securities are good in managing business risks, since they are usually disjoint from local investments. For instance, an economic meltdown in Greece may not be realized in Japan, thus a Greek investor with Japanese securities would receive some protective cushion against the crisis in his or her home country.

VIVA is a telecommunication company in the Kingdom of Bahrain, owned by Saudi Telecom Company (STC) and has been in operation since March 2010. In understanding the strategies of VIVA Company, it is essential to underscore the success story of STC, which has become a role model in the telecommunications industry in the Arab World and across borders ( VIVA , 2011). STC enjoys a wide range of advantages in the market.

For instance, it is the largest telecommunications company with regard to revenue, market capitalization and the size of workforce. It has the widest coverage and offers varying products and services. The company has been ranked highest in the market for its quality in service delivery, including A+ and A1 rating, an achievement that no other company had ever attained in the region. Globally, the company is rated among the first five best performing companies in the world.

STC acquired an operating license in the Kingdom of Bahrain in the year 2009, which was followed by the launch of VIVA in March 2010. Since its inception, VIVA has emerged to be among the leading telecommunications Company in the Kingdom of Bahrain and it is believed that the company has an array of strategies, which have propelled it to amazing performance in the market ( VIVA , 2011). Of great significance has been the company’s investment in customer satisfaction and building of strong ties.

Founded in its mission, VIVA aims at becoming the leading service provider in the country by improving the lives of its customers in a competitive business world. This is achieved through innovative communication services and products, which satisfy the needs of customers beyond their expectations. Additionally, the company is committed to equipping Bahrain communities with relevant knowledge by engaging in development programs.

Lastly, the company believes in transparency and honesty even as it is involved in the development of Bahrain’s telecommunications infrastructure. The success of these strategies is based on the company’s mission and vision, and the commitment of its leadership to perform outstandingly ( VIVA , 2011).

It is doubtless that joining a new business can be challenging and quite demanding especially when the right procedures and strategies are not put into action. In understanding these strategies, it is worth noting that different businesses may require the implementation or adoption of unique strategies (Sadler & Craig, 2003).

For example, small business strategies may differ from a multi-dollar investment. It is therefore important to have a clear picture of the business before adopting any of the strategies discussed below. Most business experts argue that formation of joint ventures with another company can be quite significant in realizing a business dream. This allows a company to merge efforts and drive a common business agenda (Kenny, 2009). Nevertheless, these efforts may be jeopardized by conflicting interests.

Additionally, some investors may opt to purchase an existing business and advance its agenda. Acquisition of an existing investment is preferred by most people because it allows the launching of a new business brand without going through initial procedures. Moreover, proponents of this strategy argue that it eliminates hurdles and barriers, which are common when entering a new business.

Nevertheless, it is important for the purchasing company to carry out enough survey and establish the history and performance of the firm on offer before sealing the acquisition deal. It can be concluded that every entry strategy has its drawbacks that have to be addressed sufficiently (Kenny, 2009).

Like other companies in the world, Sony has implemented several diversification strategies throughout its history especially after Norio Ohga took over the presidency of the company in the year 1976. After observing the struggling nature of the company, Norio remained determined to make a difference at the helm of the company.

Although Sony had concentrated in production of CDs, Norio Ohga pushed for mass manufacture of CCD ( Sony , 2012). As an innovative manager, he diversified Sony’s products by moving away from VCR to other brands that would sustain the company in a competitive business environment.

In order to meet this target, the company aimed at strengthening its brands and made advances in office automation and microcomputer products. Through miniaturization of products, Sony has continually advanced original equipment manufacturing. Additionally, Sony ventured into professional products for industrial usage and in production of component parts ( Sony , 2012).

On the other hand, General Electric remains a major manufacturer of consumer appliances, industrial products, and offers a wide range of financial services. Due to expansion and diversification, GE deals in healthcare, energy and industrial manufacturing among other sectors. In the year 2010, Forbes ranked GE as the second largest company worldwide (Barron, 2011). Its diversification approach has enabled the company to guard against poor performance among its business sectors.

Additionally, its size allows it to acquire and sell companies when market conditions are deemed favorable by the management. Integration of acquired business is also given first priority by the company’s management. The company has announced its shift to engine, healthcare and energy, and aimed at acquiring Clarient in 2010. The diversification of the two companies focuses on products and not services (Barron, 2011).

It is doubtless that there are reasons why a consumer electronic company may enter into a joint venture with a mobile phone company. A good example of such a joint venture is between Japan’s Sony, specializing in consumer electronics and Sweden’s Ericson, dealing with mobile phones.

One of the reasons why such a merger may occur is the presence of market (Tharp, 2009). For instance, the launch of joint ventures between the two companies proved popular especially with the existence of a huge target audience, who were mainly high-class people. Besides the existence of a potential business market, the compatibility of some products may force companies to join their production efforts.

This is also coupled with merging technology. For example, walkman phones and cyber-shot camera phones utilized Sony’s expertise in wireless technology to meet the demands of the market. Through their partnership, Sony Ericson has been able to produce LG electronics, emerging in fourth position as the largest manufacturer by 2006. Through this collaboration, Sony Ericson was able to register a pre-tax of € 514m in 2005, which contrasted a loss of € 291m that the company had made in 2002 (Tharp, 2009).

Additionally, the joint venture has enabled Sony Ericson to diversify and serve a wide range of customers. After its success in production of handsets, Sony Ericson targeted mobile operators like Orange through deals that were to see the company increase its sales. Moreover, this joint venture has addressed the changing needs of the mobile phone market and technology (Tharp, 2009).

Sony Ericson is able to manufacture television mobile phones to allow young people to watch TV, since they spend a lot of time online. In addition, they have addressed the issue of social media, which is driving most manufactures to woo consumers.

Barron, Z. (2011). General Electric: A Deep Analysis of Company Strategy. Web.

Kenny, G. (2009). Diversification Strategy: How to Grow a Business by Diversifying Successfully . London: Kogan Page Publishers.

Sadler, P., & Craig, C. (2003). Strategic Management . London: Kogan Page Publishers.

Sony: Chapter 24 Diversification . (2012). Web.

Tharp, A. (2009). Joint Venture: Sony Ericsson . Web.

Thompson, A., Strickland, J., & Gamble, J. (2009). Crafting and Executing Strategy: The Quest for Competitive Advantage: Concepts and Cases . New York City: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

VIVA: Company Overview . (2011). Web.

- The Selection Criteria of Employees Used by Two International Companies, Dell and Ericson

- Surveillance Assemblage

- Human Development: Adolescence as the Most Important Age Range

- Abu Dhabi Accountability Authority Recruitment Process

- Decision-Making Process at the AES Corporation

- Marketing and HR Order ID.

- Recommendations to CEO on Drug Testing Implementation

- Motivate Your Employees produced by BNet Video for CBS Money Watch

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, November 6). Strategic management. https://ivypanda.com/essays/strategic-management-3/

"Strategic management." IvyPanda , 6 Nov. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/strategic-management-3/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Strategic management'. 6 November.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Strategic management." November 6, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/strategic-management-3/.

1. IvyPanda . "Strategic management." November 6, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/strategic-management-3/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Strategic management." November 6, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/strategic-management-3/.

Interview Questions

Comprehensive Interview Guide: 60+ Professions Explored in Detail

13 Leadership Experience Examples for Interviews

By Biron Clark

Published: November 20, 2023

You could hear this question in any interview… whether it’s an entry-level position or a Director job: “What are some of your leadership experiences?”

I’m going to give you the 3 steps to make sure you give a GREAT interview answer that stands out and makes them think “yes, this is the person we should hire!”

Then, we’ll look at 13 examples of leadership experience you can include on your resume or mention in interviews (including some you may not realize you have!)

Let’s get started…

Why Do Employers Ask About Your Prior Leadership Experience?

Employers will inquire about your prior leadership experience when you interview for a position as a supervisor or manager or when they anticipate that you’ll lead a team on specific projects.

Even if you don’t have specific management experience in a prior role, you likely have experience leading a task to completion or organizing a project. Highlight your experience and the steps you took to manage your team successfully. Your example will give the interviewer a sense of what to expect if they hire you for the role.

What are Leadership Experience and Skills?

Leadership skills encompass several traits, including interpersonal communication, conflict resolution, strategic thinking, and negotiation. The right combination of leadership experience and skills allows managers to successfully motivate their teams and inspire them to work toward specific goals. Good leaders will also demonstrate accountability for their responsibilities and actions.

Watch: How to Answer “What Are Some of Your Leadership Experiences?”

How to answer “what are some of your leadership experiences”.

There are a couple of guidelines to keep in mind. You want to pick leadership examples that follow these 3 guidelines:

1. Choose an example that’s as relevant as possible

What does this mean? If you’re applying for a Customer Service Supervisor job, and you’ve had some leadership experience in other customer service roles , you should absolutely share that! That’s much more relevant than leadership on a sports team, in school, etc. So always go with what’s most relevant first!

2. Pick something that’s somewhat recent if you can

Recent experience beats older experience if everything else is equal. So when you share some of your leadership experiences, pick things that are recent whenever you have a choice.

3. And finally, choose an example that’s impressive overall

Along with thinking about which of your experiences are most relevant and recent, you need to think about how impressive something is overall. Leading a large number of people is impressive. Managing people directly is more impressive than just leading people on a quick project (especially if you’re interviewing for a job where you’ll be managing more people directly – this goes back to what’s relevant!) Leading a complex project is impressive. Handling multiple projects is impressive. You get the point. So also think about the scale of your past leadership, and the challenges involved, and try to share examples that are most challenging and have a “wow” factor.

Best Interview Answers for “What Are Some of Your Leadership Experiences?”

So to give the best answer possible, you want to combine the three points above, and then be specific. If you have previous work experience, use the STAR method – Situation, Task, Action, Result. What was the situation you were in? Was it school, a recent job, or something else? How many people did you lead, and who were they? Next, what was the task? What did you need to accomplish or what problem did you face? After that, talk about the action you took and how you led. What were your options, which did you choose as a leader, and why?

And finally, conclude your leadership experiences by talking about the RESULT. That’s most important. How did things turn out? And what did you learn from it? How did you use this experience to improve and how will you use this knowledge to perform well in this job you’re interviewing for!

It’s Okay if You Don’t Have ‘Perfect’ Leadership Examples…

Maybe you just graduated from school, or you’re applying for your first job . You might not have work-related leadership experience. That’s okay. Just pick the most relevant leadership experiences that you can think of. Do the best you can with the example you prepare. Nobody’s perfect, and nobody has every single thing an employer wants in the interview, so you just need to prepare the best you can and give the best example you can when responding to the question. And if the STAR method isn’t working (I’ve seen people struggle to use it if your example of leadership experience is from sports, etc.), make it simpler and just focus on the situation, and what you learned from it. What was the goal, and how did you help accomplish it through leadership? And how did you improve and develop as a leader? Always show what you learned at the end! That’s one of the keys to answering this type of interview question. If you don’t have any formal leadership experience (like managing a team at work, or managing client projects), here are 13 examples of leadership experience to help you get ideas…

13 Leadership Experience Examples

1. leading a project or task in school.

This can be any level of school. Choose whatever you completed most recently. If you’re a college graduate, pick a project from the last one or two years of college. If you just graduated high school, choose something from your senior year. Taking a lead role in a school project is a great example of leadership experience. If you delegated tasks, chose the overall strategy for the project, or anything like that, that’s leadership! Organizing a team presentation can also be considered leadership.

Example answer:

I was assigned to lead a team of three colleagues in my college marketing course. We had to develop a comprehensive digital marketing strategy for a hypothetical e-commerce company. I organized our group to work on different components of the plan, including our content, social media , and email strategy. We developed a 15-page report and earned an A+.

2. Organizing a study group

Maybe you didn’t lead projects in school, but you organized a study group after class. That’s still a great example of leadership and taking initiative. Any example of you taking initiative and doing something that wasn’t required, but helped you succeed, is a good leadership example.

A calculus course during college was extremely difficult, and I noticed several students were struggling with the assignments and tests. I organized a study group that met twice each week to discuss calculus concepts and work on our homework together. The group was highly beneficial; we all finished with As and Bs in the course.

3. Spotting a problem at work and finding a solution

Maybe you spotted a potential problem in your most recent job and brought it to your boss’ attention, or better yet – fixed it yourself. This is a great leadership example. Any time you go above and beyond what your basic job requires and solve a problem or take the lead on something without being asked is great leadership.

In my previous job as a quality control engineer, I noticed that a part we manufactured often had a specific defect. I looked further into the issue and found that one of our machines didn’t have the proper calibrations, and this caused the defect. I alerted a manager and we fixed the machine. After that, we saw a 90% decrease in defects for that part.

4. Sports leadership experience

If you’ve played a lead role on any sports teams, this can certainly be used as a leadership example in job interviews. So think back to your past, and whether you led any sports teams.

I was a cheerleader in high school, and we regularly competed against other teams in our city. I wanted our team to win before I graduated, so I designed a creative cheer that involved lots of stunts and dancing. We practiced hard, and our performance was rock solid at the competition. We won the event and took home several trophies.

5. Volunteer/non-profit leadership

If you’ve volunteered at a local foundation or non-profit and taken a leadership role – even in one task or for one day – you can mention this as leadership experience. Some of the best leadership experience examples can be for one single day or one single moment; it doesn’t need to be something you did for years.

I volunteer at my local Animal Rescue and usually spend at least one or two days each month caring for the animals in the shelter. I wanted to see more animals go to good homes, so I contacted a pet store to organize adoptions for dogs and cats. We moved several animals to the store, and they were immediately adopted.

6. Training/mentoring newer team members

You don’t need to have a Manager or Supervisor job title to play a lead role in a past job. If you were ever asked to help get a new team member up to speed, train them on the basics, or watch over them in their first few weeks, that’s a great example of leadership experience. This shows your past boss trusted you and knew they could rely on you. That’s one of the key things you want to try to do when sharing past leadership experiences – pick something that shows other people thought you were someone they could trust and rely on. In an interview, this will help convince the interviewer that they can also rely on you! That’ll help you get hired.

In my last role as an accountant , we expanded our department by ten new employees in six months. Most new workers were recent college graduates, so I became a mentor to help them adjust to the work environment. I introduced them to our accounting system and ensured they had the guidance to perform their tasks.

7. Managing clients/projects

Maybe you’ve never had people reporting directly to you, but you’ve managed projects or managed client accounts for your last company. You can certainly mention that as one of your leadership examples in the interview.

In my last role as a sales director, I was in charge of several prolific clients who were a significant source of revenue for our company. I ensured that our services always met their needs and regularly checked in on them so we could immediately fix any issues they encountered. Every one of the clients I worked with renewed their contract with our company.

8. Direct reports

If you’ve ever had direct reports, this is the most powerful example you can give. If you hired people, did annual reviews, and had them report to you on a regular basis, this shows your employer trusted you at a very high level. While most people aren’t going to be able to give this as an example, if you can, you should!

In my last role as the human resources manager , I oversaw a team of six employees. I ensured they had all the resources needed to handle their responsibilities and was always there to guide them if questions arose. During my time, the company promoted two of my team members to supervisory positions, and they credited my mentorship as a significant reason for their success.

9. Leading a meeting or committee

This can be at school, at an after-school organization, any type of volunteer organization, a job, a club, etc. If you led a meeting or committee for even a short time period or one-time event, that’s still great leadership experience to put on a resume and then talk about in interviews if asked. For example, if you were part of a club that needed to host an event, and they put you in charge of the committee responsible for finding a venue and calling different event halls to ask if they’re available – that’s something you led.

As the project manager for the compliance department, I led a weekly meeting with our legal, accounting, finance, and tax team members. Before the meeting, I organized all the topics to discuss and any current updates I had. I ensured that each session was smooth and productive and that every participant understood the responsibilities they needed to take care of in the next week.

10. Passion projects

Even if you took the lead on a project that wasn’t work-related and wasn’t for a non-profit, you can still share it as a leadership example. Maybe you got three friends together to build an electric go-cart. This still shows the ability to manage and organize a highly-technical, time-consuming project. That’s a valuable trait for many jobs! So don’t be shy about sharing examples of leadership experience even if you weren’t paid for it, weren’t officially a “manager”, and weren’t doing it for an official organization or employer!

While in college, I decided to organize a group of people who enjoyed weekend hikes. I’m a regular hiker familiar with the nearby trails, so I led every trek, ensuring that everyone remained safe and enjoyed the time spent in nature. By the end of the first semester, over 100 students had joined the club. Even though it’s been a few years since my last college hike, we still keep in contact and share the hikes and nature adventures we embark on.

11. Conflict Resolution

Everyone experiences conflict at some point in their lives, both personally and professionally. However, not everyone can successfully resolve disputes. If you have a noteworthy example of conflict resolution, share it with the interviewer. For example, perhaps you stopped a disagreement between two colleagues and found a reasonable compromise that suited both parties.