- Open access

- Published: 07 August 2023

A scoping review of trauma informed approaches in acute, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care

- Katherine R. K. Saunders 1 ,

- Elizabeth McGuinness 1 ,

- Phoebe Barnett 2 , 3 , 4 ,

- Una Foye 1 ,

- Jessica Sears 5 ,

- Sophie Carlisle 6 ,

- Felicity Allman 2 , 7 ,

- Vasiliki Tzouvara 8 ,

- Merle Schlief 2 ,

- Norha Vera San Juan 1 ,

- Ruth Stuart 1 ,

- Jessica Griffiths 1 ,

- Rebecca Appleton 2 ,

- Paul McCrone 9 , 10 ,

- Rachel Rowan Olive 11 , 12 ,

- Patrick Nyikavaranda 11 , 12 ,

- Tamar Jeynes 11 ,

- Lizzie Mitchell 11 ,

- Alan Simpson 1 , 7 ,

- Sonia Johnson 2 &

- Kylee Trevillion 1

BMC Psychiatry volume 23 , Article number: 567 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

5326 Accesses

1 Citations

47 Altmetric

Metrics details

Experiences of trauma in childhood and adulthood are highly prevalent among service users accessing acute, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health services. These settings, and restraint and seclusion practices used, can be extremely traumatic, leading to a growing awareness for the need for trauma informed care (TIC). The aim of TIC is to acknowledge the prevalence and impact of trauma and create a safe environment to prevent re-traumatisation. This scoping review maps the TIC approaches delivered in these settings and reports related service user and staff experiences and attitudes, staff wellbeing, and service use outcomes.

We searched seven databases (EMBASE; PsycINFO; MEDLINE; Web of Science; Social Policy and Practice; Maternity and Infant Care Database; Cochrane Library Trials Register) between 24/02/2022-10/03/2022, used backwards and forwards citation tracking, and consulted academic and lived experience experts, identifying 4244 potentially relevant studies. Thirty-one studies were included.

Most studies (n = 23) were conducted in the USA and were based in acute mental health services (n = 16). We identified few trials, limiting inferences that can be drawn from the findings. The Six Core Strategies (n = 7) and the Sanctuary Model (n = 6) were the most commonly reported approaches. Rates of restraint and seclusion reportedly decreased. Some service users reported feeling trusted and cared for, while staff reported feeling empathy for service users and having a greater understanding of trauma. Staff reported needing training to deliver TIC effectively.

TIC principles should be at the core of all mental health service delivery. Implementing TIC approaches may integrate best practice into mental health care, although significant time and financial resources are required to implement organisational change at scale. Most evidence is preliminary in nature, and confined to acute and residential services, with little evidence on community crisis or emergency services. Clinical and research developments should prioritise lived experience expertise in addressing these gaps.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The concept of providing ‘trauma informed care’ (TIC) in healthcare settings has developed in response to increasing recognition that potentially traumatic experiences throughout the life course are associated with subsequent psychological distress and a range of mental health problems [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. ‘Trauma’ has no universally agreed definition. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) defined trauma as ‘an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being’ [ 5 ]. Traumatic experiences include physical, sexual and/or emotional abuse, neglect, exposure to violence or conflict, physical or mental illness (personal experience or that of a family member), and systemic or social traumas [ 6 , 7 ].

Individuals engaged with mental health services report high levels of childhood and adulthood trauma [ 2 , 8 , 9 , 10 ], and there is a high prevalence of trauma among service users in acute services, including among women [ 2 , 11 ], those with psychosis [ 12 , 13 ], and “personality disorder” diagnoses [ 14 ] (which is a particularly controversial diagnosis [ 15 ] as a result of the stigma associated with this diagnostic label and disparities in quality of care experienced [ 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ]). Electronic health record evidence shows that service users with a history of abuse during childhood have more comorbidities and are more likely to have inpatient admissions versus service users without a similar history [ 20 ]. Similarly, among people with long-term mental health conditions, rates of childhood trauma and adversity are high, with both experiences theorised as aetiological factors for mental health conditions [ 21 , 22 , 23 ]. Staff in acute services are also affected by trauma experienced at work, which are highlighted as a source of stress and create a cycle of ‘reciprocal traumatisation’ [ 24 , 25 ].

Inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care settings (typology of care categories adapted from an exploration of the range, accessibility, and quality of acute psychiatric services [ 26 ]) are used by service users experiencing severe mental health episodes. Such settings include acute wards, community crisis teams, psychiatry liaison teams within emergency departments, and mental health crisis houses. These settings can be experienced as destabilising and retraumatising as a result of compulsory detention under mental health legislation, e.g., the Mental Health Act in the UK [ 27 ] and routine staff procedures for managing the behaviour of distressed service users in inpatient settings, including seclusion and restraint [ 6 , 28 ]. These experiences can also constitute a traumatic experience in their own right [ 24 , 29 ]. Power imbalances in these settings can create abusive dynamics, as well as mirror previous abusive relationships and situations [ 6 ], engendering mistrust and creating a harmful environment.

In principle, TIC centres an understanding of the prevalence and impact of trauma, recognises trauma, responds comprehensively to trauma and takes steps to avoid re-traumatisation [ 5 ]. The TIC literature in healthcare is varied and lacks an agreed definition. However, Sweeney and Taggart (2018) [ 6 ], who both write from dual perspectives as researchers and trauma survivors, developed an adapted definition of TIC, [ 5 , 30 , 31 ] which we have used as a working definition throughout this scoping review as a result of its comprehensiveness. They define TIC as ‘a programme or organisational/system approach that: [i] understands and acknowledges the links between trauma and mental health, [ii] adopts a broad definition of trauma which recognises social trauma and the intersectionality of multiple traumas, [iii] undertakes sensitive enquiry into trauma experiences, [iv] refers individuals to evidence-based trauma-specific support, [v] addresses vicarious trauma and re-traumatisation, [vi] prioritises trustworthiness and transparency in communications, [vii] seeks to establish collaborative relationships with service users, [viii] adopts a strengths-based approach to care, [ix] prioritises emotional and physical safety of service users, [x] works in partnership with trauma survivors to design, deliver and evaluate services.’ This comprehensive definition includes elements covered by SAMSHA [ 32 ], the UK Office for Health Improvement & Disparities [ 33 ] and the NHS Education for Scotland (NES) Knowledge and Skills Framework for Psychological Trauma [ 34 ]. Understanding how experiences of trauma impact on individuals presenting in mental health services can support service users to feel heard, understood and able to cope or recover, and can support staff to have a greater understanding of the mental health difficulties and symptoms experienced by service users [ 6 , 31 , 35 ]. For TIC to be implemented, these tenets must be embedded within both formal and informal policy and practice [ 36 ], which can be challenging in these settings.

TIC within inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care settings is newly established; there is no research mapping system-wide trauma informed approaches in these settings. The aim of this scoping review is to identify, map and explore the trauma informed approaches used in these settings, and to review impacts on and experiences of service users and staff. We also highlight gaps and variability in literature and service provision. TIC is a broad term, and it has been applied in numerous and varied ways in mental health care. In this review, we describe each application of TIC as a ‘trauma informed approach’.

This scoping review will answer the following primary research question:

What trauma informed approaches are used in acute, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

Within each trauma informed approach identified, we will answer the following secondary research questions:

What is known about service user and carer expectations and experiences of TIC in acute, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

How does TIC in acute, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care impact on service user outcomes?

What is known about staff attitudes, expectations, and experiences of delivering TIC in acute, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

How does TIC impact on staff practices and staff wellbeing in acute, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

How does TIC in acute, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care impact on service use and service costs, and what evidence exists about their cost-effectiveness?

Study design

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR [ 37 ]), using a framework for conducting scoping reviews [ 38 ]. The PRISMA-ScR checklist can be seen in Appendix 1. The protocol was registered with the Open Science Framework ahead of conducting the searches ( https://osf.io/2b5w7 ). The review was steered by a team including academic experts, clinical researchers, and experts by experience and/or profession, with lived experience researchers contributing to the development of the research questions, the data extraction form, the interpretation, and the manuscript draft.

Eligibility criteria

Service users, or people who support or care for service users, of any age (both adults and children), gender or sexuality, or staff members (of any gender and sexuality) were included.

We included studies that focused (or provided disaggregated data) on care delivered within acute, crisis, emergency settings, or residential mental health settings; acute and crisis settings include inpatient, community-based crisis, hospital emergency department, acute day units and crisis houses. Forensic mental health and substance use acute, crisis and inpatient settings were also included. We excluded studies from general population prison settings, where there is debate as to whether TIC can be delivered in carceral settings ( 39 ), and residential settings where the primary purpose of the setting was not to provide mental health or psychiatric care (e.g., foster care or residential schools).

Intervention

Trauma informed care interventions. Programmes aiming to reduce restrictive practices in psychiatric settings were not included without explicit reference to TIC within the programme.

We included studies reporting any positive and adverse individual-, interpersonal-, service- and/or system-level outcomes, including outcomes from the implementation, use or testing of TIC. Individual-level outcomes are related to service user or staff experiences, attitudes, and expectations; interpersonal outcomes occur because of interactions between staff and service users; service-level outcomes include TIC procedures that occur on an individual service level; and system-level outcomes refer to broader organisational outcomes related to TIC implementation. We included studies exploring service user, staff and carer expectations and experiences of TIC approaches.

Types of studies

We included qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-method research study designs. To map TIC provision, service descriptions, evaluations, audits, and case studies of individual service provision were also included. We excluded reviews, conference abstracts with no associated paper, protocols, editorials, policy briefings, books/book chapters, personal blogs/commentaries, and BSc and MSc theses. We included non-English studies that our team could translate (English, German, Spanish). Both peer-reviewed and grey literature sources were eligible.

Search strategy

A three-step search strategy was used. Firstly, we searched seven databases between 24/02/2022 and 10/03/2022: EMBASE; PsycINFO; MEDLINE; Web of Science; Social Policy and Practice; Maternity and Infant Care Database (formerly MIDIRS); Cochrane Library Trials Register. An example full search strategy can be seen in Appendix 2. Searches were also run in one electronic grey literature database (Social Care Online); two pre-print servers (medRxiv and PsyArXiv), and two PhD thesis websites (EThOS and DART). The search strategy used terms adapted from related reviews [ 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 ]. We added specific health economic search terms. No date or language limits were applied to searches. Secondly, forward citation searching was conducted using Web of Science for all studies meeting inclusion criteria. Reference lists of all included studies were checked for relevant studies. Finally, international experts, networks on TIC in mental health care, and lived experience networks were contacted to identify additional studies.

Study selection

All studies identified through database searches were independently title and abstract screened by KS, KT and NVSJ, with 20% double screened. All full texts of potentially relevant studies were double screened independently by KS and KT, with disagreements resolved through discussion. Screening was conducted using Covidence [ 50 ]. Studies identified through forwards and backwards citation searching and expert recommendation were screened by KS, EMG, and NVSJ.

Charting and organising the data

A data extraction form based on the research questions and potential outcomes was developed using Microsoft Excel and revised collaboratively with the working group. Information on the study design, research and analysis methods, population characteristics, mental health care setting, and TIC approach were extracted alongside data relating to our primary and secondary outcomes. The form was piloted on three included papers and relevant revisions made. Data extraction was completed by KS, EMG, VT, SC, and FA, with over 50% double extracted to check for accuracy by KS and EMG.

Data synthesis process

Data relevant for each research question was synthesised narratively by KS, EMG, JS, UF, VT, FA, and MS. Question 1 was grouped by approach and reported by setting. Where data was available, evidence for questions 2–6 was synthesised within each TIC approach.

Both quantitative and qualitative data were narratively synthesised together for each question. Areas of heterogeneity were considered throughout this process and highlighted. The categorisation and synthesis of the trauma informed approaches were discussed and validated by KS, EMG, JS, and KT.

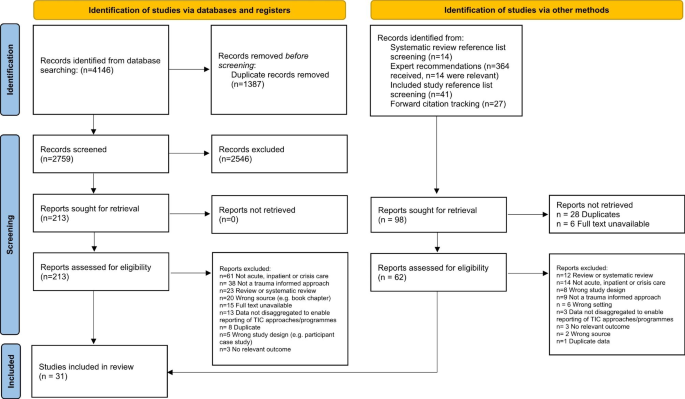

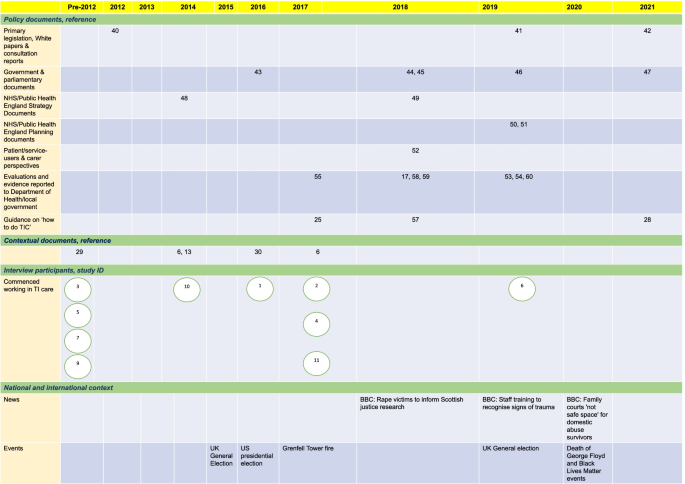

The database search returned 4146 studies from which 2759 potentially relevant full-text studies were identified. Additional search methods identified 96 studies. Overall, 31 studies met inclusion criteria and were included in this review. The PRISMA diagram can be seen in Fig. 1 . Characteristics of all included studies are shown in Table 1 .

PRISMA diagram demonstrating the search strategy. From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71 . For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/

Study characteristics

The models reported most commonly were the Six Core Strategies (n = 7) and the Sanctuary Model (n = 6). Most included studies were based in the USA (n = 23), followed by the UK (n = 5), Australia (n = 2), and Japan (n = 1). Most studies were undertaken in acute services (n = 16) and residential treatment services (n = 14), while one was undertaken in an NHS crisis house. Over a third of studies were based in child, adolescent, or youth mental health settings (n = 12), while six were based in women’s only services. See Table 1 for the characteristics of all included studies.

Twenty-one studies gave no information about how they defined ‘trauma’ within their models. Of the ten studies that did provide a definition, four [ 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 ] referred to definitions from a professional body [ 5 , 55 , 56 ]; three studies [ 57 , 58 , 59 ] used definitions from peer-reviewed papers or academic texts [ 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 ]; in two studies [ 64 , 65 ], authors created their own definitions of trauma; and in one study [ 66 ], the trauma definition was derived from the TIC model manual. See full definitions in Appendix 3. Some studies reported details on participants’ experiences of trauma, these are reported in Table 1 .

What trauma informed approaches are used in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

Thirty-one studies in twenty-seven different settings described the implementation of trauma informed approaches at an organisational level in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential settings. The different models illustrate that the implementation of trauma informed approaches is a dynamic and evolving process which can be adapted for a variety of contexts and settings.

Trauma informed approaches are described by model category and by setting. Child and adolescent only settings are reported separately. Full descriptions of the trauma informed approaches can be seen in Appendix 3. Summaries of results are presented; full results can be seen in Appendix 4.

Six Core Strategies

Seven studies conducted in four different settings implemented the Six Core Strategies model of TIC practice for inpatient care [ 51 , 59 , 65 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 ]. The Six Core Strategies were developed with the aim of reducing seclusion and restraint in a trauma informed way [ 71 ]. The underpinning theoretical framework for the Six Core Strategies is based on trauma-informed and strengths-based care with the focus on primary prevention principles.

Inpatient settings: child and adolescent services

Four studies using Six Core Strategies were conducted in two child and adolescent inpatient settings using pre/post study designs [ 59 , 67 , 68 , 69 ]. Hale (2020) [ 67 ] describes the entire process of implementing the intervention over a 6-month period and establishing a culture change by 12 months, while Azeem et al’s (2015) [ 69 ] service evaluation documents the process of implementing the six strategies on a paediatric ward in the USA over the course of ten years.

Inpatient settings: adult services

Two studies focused on the use of the Six Core Strategies in adult inpatient and acute settings [ 51 , 65 ]. One further study, Duxbury (2019) [ 70 ], adapted the Six Core Strategies for the UK context and developed ‘REsTRAIN YOURSELF’, described as a trauma informed, restraint reduction programme, which was implemented in a non-randomised controlled trial design across fourteen adult acute and inpatient wards in seven hospitals in the UK.

How does the Six Core Strategies in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care impact on service user outcomes?

Five studies, only one of which had a control group [ 70 ], reported a reduction in restraint and seclusion practices after the implementation of the Six Core Strategies [ 59 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 ]. Two studies [ 51 , 65 ] did not report restraint and seclusion data.

What is known about staff attitudes, expectations, and experiences of delivering the Six Core Strategies in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

Staff reported an increased sense of pride in their ability to help people with a background of trauma [ 59 ], which came with the skills and knowledge development provided [ 51 ]. Staff also showed greater empathy and respect towards service users [ 51 , 65 ].

Staff recognised the need for flexibility in implementing the Six Core Strategies, and felt equipped to do this; as a result they reported feeling more fulfilled as practitioners [ 51 ]. Staff shifted their perspectives on service users and improved connection with them by viewing them through a trauma lens [ 65 ]. Staff also reported improved team cohesion through the process of adopting the Six Core Strategies approach [ 51 ]. It was emphasised that to create a safe environment, role modelling by staff was required [ 65 ].

How does the Six Core Strategies impact on staff practices and staff wellbeing in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

Service users were reportedly more involved in their own care; they reviewed safety plans with staff, and were involved in their treatment planning, including decisions on medication [ 51 , 65 ]. Staff and service users also engaged in shared skill and knowledge building by sharing information, support, and resources on healthy coping, and trauma informed care generally [ 51 , 65 ]. Staff adapted their responses to service user distress and adopted new ways of managing risk and de-escalating without using coercive practices [ 51 , 59 ]. Finally, service user-staff relationships were cultivated through a culture of shared learning, understanding, and trust [ 65 ].

How does the Six Core Strategies in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care impact on service use and costs and what evidence exists about their cost-effectiveness?

One study reported a reduction in the duration of hospital admission [ 59 ], which was largely attributed to the reduction in the amount of documentation that staff had to complete following crisis interventions.

The Sanctuary Model

Six studies, referring to five different settings [ 57 , 58 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 ], employed the ‘Sanctuary Model’ [ 76 ] as a TIC model of clinical and organisational change. One further study [ 72 ] combined the ‘Sanctuary Model’ with ‘Seeking Safety’, an integrated treatment programme for substance misuse and trauma. All studies were conducted in child and adolescent residential emotional and behavioural health settings in the USA.

The Sanctuary Model is a ‘blueprint for clinical and organisational change which, at its core, promotes safety and recovery from adversity through the active creation of a trauma-informed community’ [ 76 ]. It was developed for adult trauma survivors in short term inpatient treatment settings and has formally been adapted for a variety of settings including adolescent residential treatment programmes. No studies explored the use of the Sanctuary Model as a TIC approach in adult inpatient or acute settings, and no studies specifically tested the efficacy of The Sanctuary Model in child and adolescent settings. Studies employing the Sanctuary Model used a range of designs including longitudinal, qualitative methods, service evaluations/descriptions and a non-randomised controlled design.

What is known about service user and carer expectations and experiences of the Sanctuary Model in acute, crisis and inpatient mental health care?

In a service description, Kramer (2016) [ 57 ] reported that service users experienced clear interpersonal boundaries with staff, facilitated by healthy attachments and organisational culture. Service users also experienced staff responses as less punitive and judgemental.

How does the Sanctuary Model in acute, crisis and inpatient mental health care impact on service user outcomes?

Kramer (2016) [ 57 ] described decreasing rates of absconscion, restraint, and removal of service users from the programme post-implementation of the Sanctuary Model, which the authors hypothesised was due to the safe environment, and the movement towards a culture of hope.

What is known about staff attitudes, expectations, and experiences of delivering the Sanctuary Model in acute, crisis and inpatient mental health care?

Staff received the Sanctuary Model positively [ 72 , 73 ] and it gave them a sense of hopefulness [ 75 ]. However, it was widely acknowledged that it was resource intensive for staff to implement TIC in practice and additional training may be needed [ 73 ].

Korchmaros et al. (2021) [ 72 ] reported that the Sanctuary Model components most likely to be adopted were those that staff found most intuitive, though staff generally did not believe the model was acceptable in its entirety for their clinical setting. As staff communication improved, so did physical safety for staff and service users, and team meeting quality [ 75 ]. Staff appreciated the improved safety – or perception of such – after implementing the Sanctuary Model [ 73 , 75 ].

Staff reported that the Sanctuary Model promoted a healthy organisational culture with a commitment to a culture of social responsibility, social learning [ 57 ] and mutual respect [ 73 ].

How does the Sanctuary Model impact on staff practices and staff wellbeing in acute, crisis and inpatient mental health care?

Following implementation, staff focused more on service user recovery through teaching service users adaptive ways of coping and encouraging empathy and compassion towards service users [ 58 , 73 , 75 ]. Staff reported a holistic and compassionate understanding of the associations between trauma, adversity and service user behaviour [ 73 ]. Staff also reported sharing more decisions with service users [ 73 ] and collaboratively involving service users in their treatment care, safety plans, and in the development of community rules [ 73 , 75 ]. Staff felt able to communicate information, ideas, and their mistakes more openly, and their ability to model healthy relationships was seen as a fundamental to treatment [ 75 ].

How does the Sanctuary Model in acute, crisis and inpatient mental health care impact on service use and costs and what evidence exists about their cost-effectiveness?

One study reported a reduction in staff compensation claims due to a reduction in harms from physical interventions [ 72 ].

Comprehensive tailored trauma informed model

We categorised eight models [ 52 , 53 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 ] as ‘comprehensive tailored TIC models’. This reflects models that are holistic and multi-faceted, but do not closely follow an established TIC intervention model or blueprint and have instead been developed locally or to specifically complement the needs of a specific setting.

Residential settings: child and adolescent services

Three studies describe comprehensive tailored trauma informed models in child and adolescent residential treatment settings [ 77 , 78 , 79 ]. At an organisational level, key features of the tailored approaches include whole staff training using a trauma informed curriculum [ 77 , 78 , 79 ], creating a supportive, therapeutic environment and sense of community, using a family-centred approach, structured programmes of psychoeducational, social and skills groups [ 77 , 79 ] and collaborative working across different agencies [ 78 , 79 ].

Residential settings: adult women-only substance misuse service

Three studies [ 53 , 80 , 81 ] describe a gender-specific trauma informed treatment approach in a female only environment. Key components include providing training for all staff on trauma and trauma informed approaches, team support and supervision from a trained trauma therapist, social and life skills groups [ 53 ]; individual therapy and family support programme [ 81 ]; trauma informed group therapies and psychoeducation [ 53 , 80 ]; the implementation of a ‘gender specific, strengths based, non-confrontational, safe nurturing environment’ and strategic level meetings to identify structural barriers and gaps across different agencies [ 80 ]. Zweben et al. (2017) [ 81 ] focused specifically on family-centred treatment for women with severe drug and alcohol problems.

Inpatient settings: adults and children/adolescents

The ‘Patient Focussed Intervention Model’ [ 82 ] was implemented in a variety of settings including residential child and adolescent, adult acute and adult longer term inpatient stays. This model was developed using a collaborative process with involvement from service users, staff, administrators, and external collaborators with continuous quality improvement. The model incorporated (i) an individual TIC treatment model, which emphasised a patient-centred approach to building a culture and environment which is soothing and healing (e.g., by making changes to the physical environment and providing animal assisted therapy), (ii) the Sorensen and Wilder Associates (SWA) aggression management program [ 83 ] and (iii) staff debriefing after incidents of aggression.

Inpatient settings: women-only forensic service

Stamatopoulou (2019) [ 52 ] used qualitative research methods to explore the process of transitioning to a TIC model in a female forensic mental health unit [ 52 ] using the ‘trauma informed organisational change model’ [ 84 ]. Components included (i) staff training on trauma-informed care, (ii) co-produced safety planning through five sessions of Cognitive Analytic Therapy [ 85 ], (iii) a daily ‘Trauma Champion’ role for staff, and (iv) reflective practice groups for staff and service users.

What is known about service user and carer expectations and experiences of comprehensive tailored trauma informed models in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

In a study by Tompkins & Neale (2018) [ 53 ], service users reported being unaware that the service they were attending was trauma informed and were therefore not anticipating being encouraged to confront and reflect on their traumas [ 53 ]. However, the daily structure and routine timetable created a secure environment for their treatment experience. Service users who remained engaged with the service felt cared for by staff, and that the homely atmosphere in the service supported them to feel secure.

How do comprehensive tailored trauma informed models in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care impact on service user outcomes?

Three studies reported data on seclusion and restraints; all indicated a decrease [ 78 , 81 , 82 ]. Brown et al. (2013) [ 78 ] quantitatively reported reductions in the use of both seclusion and restraint in the year following Trauma Systems Therapy implementation, and the reduction in use of physical restraints was significant and sustained over the following eight years. Goetz et al. (2012) [ 82 ] also quantitatively reported that seclusion and restraint rates halved following implementation of the Patient Focused Intervention Model, as well as reductions in: (i) staff injuries, (ii) hours in seclusion and restraint and (iii) the number of aggressive patient events. However, while the number of seclusion room placements was lower, the average number of restraints among children and young people was higher in TIC compared to usual care.

Using a pre-post design, Zweben et al. (2017) [ 81 ] reported that service users receiving TIC reported fewer psychological and emotional problems after a month, compared to on entry to the programme, as well as reduced drug and alcohol misuse. Service user average length of stay was higher among those in the programme, compared to those not enrolled. Finally, as court and protective services became aware of the service users’ improvements, reunifications with children approached 100%.

What is known about staff attitudes, expectations, and experiences of delivering comprehensive tailored trauma informed models in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

Two papers reported on staff attitudes and experiences [ 52 , 53 ]. Some staff experienced introduction of TIC as overwhelming, leaving them unsure about what was expected from them throughout the training and implementation process, and that it might have been more successful had it been implemented in stages [ 52 ]. Some staff also felt unsure of what TIC entailed even after training, and it took time for staff to feel competent and confident [ 53 ]. Staff who had the least awareness of TIC experienced the greatest change anxiety when they were told of its implementation. When there were conflicting views within the team, the consistency of implementation was reduced [ 52 ]. Conversely, however, staff reported a sense of achievement in having implemented TIC and consequently an increased sense of job satisfaction.

Staff reported that their own traumatic experiences can inform the way they communicate and react to situations in the clinical environment, and they needed help to set boundaries and avoid emotional over involvement [ 53 ]. Implementing TIC broke down barriers between their private and professional selves, and there was an increased awareness of the personal impact of their work.

How do comprehensive tailored trauma informed models impact on staff practices and staff wellbeing in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

Stamatopoulou (2019) [ 52 ] reported that with the introduction of TIC, staff moved away from a solely diagnosis-based understanding of distress and developed an ability to formulate connections between service users’ backgrounds and their clinical presentations. As a result, staff showed empathy and respect towards service users and approached sensitive situations with service users more mindfully. Staff adopted new ways of managing risk [ 52 ] and service users were collaboratively involved in the development of treatment care plans [ 53 ]. Goetz et al. (2012) [82] also reported reduced staff injuries in the first year after implementing TIC.

There was an increased focus on staff wellbeing as well as greater awareness of staff personal boundaries and experiences of trauma and adversity, which led to staff feeling as though they had more in common with service users than expected [ 52 ]. Staff also discussed the importance of protecting their wellbeing by maintaining personal and professional boundaries, practicing mindfulness, and attending mutual aid groups [ 53 ].

Wider group relationships were reportedly redefined, and the impact of the work on staff wellbeing was acknowledged, specifically the ways in which staff’s own trauma informed their reactions to incidents on the ward [ 52 ]. Staff reported a greater sense of team connectedness, and that their individual professional identities were reconstructed.

How do comprehensive tailored trauma informed models in inpatient, crisis, emergency and residential mental health care impact on service use and costs and what evidence exists about their cost-effectiveness?

Staff had concerns over the sustainability of the model, especially in an organisation that could not offer the time or money required for service development [ 52 ]. Fidelity to a model varied depending on which staff were working; for instance, when agency staff or new joiners were working, fidelity was low and crisis incidents increased.

Adolescents in residential treatment receiving TIC spent significantly less time in treatment compared to those receiving traditional treatment, with the receipt of trauma informed psychiatric residential treatment (TI-PRT) accounting for 25% of the variance in length of stay [ 77 ]. Similarly, authors observed reduced length of hospital admissions after the introduction of their TIC approach [ 79 ].

Safety focused tailored trauma informed models

Two studies [ 86 , 87 ] tailored their own trauma-informed approach to create a culture of safety and (i) reduce restrictive practices and (ii) staff injuries. A third study [ 88 ] utilised a Trauma and Self Injury (TASI) programme, which was developed in the National High Secure Service for Women.

Inpatient settings: adults and child/adolescent services

Blair et al. (2017) [ 86 ] conducted a pilot trauma informed intervention study with the aim of reducing seclusions and restraints in a psychiatric inpatient hospital facility. Intervention components included the use of Broset Violence Checklist (BVC) [ 89 , 90 , 91 ]; 8-hour staff training in crisis intervention; two-day training in “Risking Connections” [ 92 ]; formal reviewing of restraint and seclusion incidents; environmental enhancements; and individualised plans for service users.

Borckardt et al. (2011) [ 87 ] reported a ‘trauma informed care engagement model’ to reduce restraint and seclusion across five various inpatient units (acute, child and adolescent, geriatric, general and a substance misuse unit). The intervention components included TIC training, changes in rules and language to be more trauma sensitive, patient involvement in treatment planning and physical changes to the environment.

Jones (2021) [ 88 ] reported the TASI programme in a high security women’s inpatient hospital, which aimed to manage trauma and self-injury with a view to reducing life threatening risks to service users and staff. The programme: (i) promotes understanding of trauma through staff training, staff support and supervision on the wards, (ii) provides psychoeducation and wellbeing groups for service users, (iii) focuses on the improvement of the therapeutic environment, (iv) promotes service users’ ability to cope with their distress, and (v) provides individual and group therapy.

What is known about service user and carer expectations and experiences of safety focused tailored trauma informed models in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

In Jones (2021) [ 88 ], some women reported feeling initially overwhelmed by and underprepared to acknowledge and work on their trauma experiences, and sometimes felt their distress was misunderstood by the nurses in their setting, which could lead to an escalation [ 88 ]. Service users felt connected to themselves, to feel safe and contained, particularly in comparison to previous inpatient experiences. Overall, however, the service did not make the women feel as though their problems were fully understood.

How do safety-focused tailored trauma informed models in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care impact on service user outcomes?

Reductions in the number of seclusions and restraint were reported [ 86 , 87 ]. Specifically, the trauma informed change to the physical therapeutic environment was associated with a reduction in the number of both seclusion and restraint [ 87 ]. The duration of restraints reportedly increased, while duration of seclusion decreased [ 86 ].

What is known about staff attitudes, expectations, and experiences of delivering safety focused tailored trauma informed models in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

In Jones (2021) [ 88 ], nurses emphasised that shared understanding and trust were instrumental in connecting and communicating with the women in their service [ 88 ]. Nurses also cultivated service user-staff therapeutic relationships, which they experienced as intensely emotional. The nurses reported becoming more critical of other staff members they perceived as lacking compassion towards the service users. Finally, staff felt that a barrier to the nurse-service user relationship was the staff’s inability to share personal information and vulnerability back to the service user.

How do safety focused tailored trauma informed models impact on staff practices and staff wellbeing in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

Staff developed new tools and adapted their responses to trauma and distress, and service users were also involved in some, but not all, staff training [ 88 ]. There were changes to information sharing practices [ 52 ]; information on service users’ history and intervention plans were more openly shared within the team to ensure all staff had the same information and did not need to risk re-traumatising service users by asking for information again. Service users also reported being more involved in their treatment planning [ 51 , 87 ] and medication decisions [ 65 ].

Trauma informed training intervention

Three studies focused on trauma informed training interventions for staff [ 66 , 93 , 94 ]. All studies used a pre/post design to evaluate effectiveness.

Gonshak (2011) [ 66 ] reported on a specific trauma informed training programme called Risking Connections [ 92 ] implemented in a residential treatment centre for children with ‘severe emotional disabilities’. Risking Connections is a training curriculum for working with survivors of childhood abuse and includes (i) an overarching theoretical framework to guide work with trauma and abuse (ii) specific intervention techniques (iii) a focus on the needs of trauma workers as well as those of their clients.

Niimura (2019) [ 93 ] reported a 1-day TIC training intervention, covering items including the definition of trauma, evidence on trauma and behavioural, social, and emotional responses to traumatic events, on attitudes of staff in a psychiatric hospital setting. Aremu (2018) [ 94 ] reported a training intervention to improve staff engagement which they identified as a key component of TIC. The intervention was a 2-hour training on engaging with patients, however the specific content of the training is not specified.

What is known about staff attitudes, expectations, and experiences of delivering trauma informed training interventions in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

Following training, half of staff reported feeling their skills or experience were too limited to implement changes and also that staff experienced difficulties when trying to share the principles of trauma informed care with untrained staff [ 93 ]. However, TIC training did produce positive attitude shifts towards TIC.

How do trauma informed training interventions impact on staff practices and staff wellbeing in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

Staff modified their communication with service users by altering their tone and volume, and adopted new ways of managing risk without using coercive practices [ 93 ]. There was also a reported a reduction in the use of as-needed medication [ 94 ].

How do trauma informed training interventions in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care impact on service use and costs and what evidence exists about their cost-effectiveness?

One study reported that educating staff about TIC in residential settings was time intensive and may require frequent or intense “booster” sessions following the initial training [ 66 ]. In terms of evaluation, it took time to implement TIC in the residential setting and then to collect related outcome data.

Other TIC models

This category reports studies which have made attempts to shift the culture towards trauma-informed approaches but have not made full-scale clinical and organisational changes to deliver a comprehensive trauma informed model [ 28 , 54 , 64 , 95 ].

Isobel and Edwards’ (2017) [ 64 ] case study on an Australian inpatient acute ward described TIC ‘as a nursing model of care in acute inpatient care’. This intervention was specifically targeted at nurses working on acute inpatient units but did not involve members of the multi-disciplinary team.

Beckett (2017) [ 95 ] conducted a TIC improvement project on an acute inpatient ward (which primarily received admissions through the hospital emergency department) using workforce development and a participatory methodology. Staff devised workshops on trauma informed approaches, through which six key practice areas were identified for improvement by the staff team.

Jacobowitz et al. (2015) [ 54 ] conducted a cross-sectional study in acute psychiatric inpatient wards to assess the association between TIC meetings and staff PTSD symptoms, resilience to stress, and compassion fatigue. Neither the content nor the structure of the ‘trauma informed care meetings’ were described in further detail.

Crisis house setting

Prytherch, Cooke & March’s (2020) [ 28 ] qualitative study of a ‘trauma informed crisis house’, based in the UK, gives a partial description of how trauma informed approaches were embedded in the service delivery and design.

What is known about service user and carer expectations and experiences of other TIC models in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

Prytherch, Cooke and March (2020) [ 28 ] reported that their TIC model created a positive experience for service users by making them feel worthwhile, respected and heard by staff [ 28 ]. Service users valued being trusted by staff, for example, to have their own room keys and to maintain their social and occupational roles, which were a key source of self-worth. While service user experiences were often positive, they found being asked directly about trauma challenging. This was invalidating for those who did not initially identify as having experienced trauma. Some service users also felt the TIC programme could only support them so far, as it did not incorporate or address wider societal injustices, such as issues related to housing and benefits, that can contribute to and exacerbate distress.

How do other TIC models in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care impact on service user outcomes?

Beckett et al. (2017) [ 95 ] reported that in the three years after the TIC workshops, rates of seclusion dropped by 80%, as did the length of time spent in seclusion, with most seclusions lasting less than an hour.

What is known about staff attitudes, expectations, and experiences of delivering other TIC models in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

Staff found an increased sense of confidence and motivation in managing emotional distress and behavioural disturbance [ 95 ]. Staff also showed increased respect, understanding and compassion towards service users.

Similarly, staff expressed hope for improved care in future, on the basis that they were better skilled to deliver care that was consistent and cohesive, while also being individual and flexible [ 64 ]. They reported a need for clarity and consistency in their role expectations and felt that changes in practice needed to be introduced slowly and framed positively. Conversely, others felt the changes introduced were too minimal to be significant and did not much vary from existing practice. Some staff expressed a fear of reduced safety that could follow changes to longstanding practice. Ambivalence to change stemmed from different degrees of understanding of TIC among staff, and others felt personally criticised by the newly introduced approach, specifically that their previous practice had been labelled traumatising.

How do other TIC models impact on staff practices and staff wellbeing in inpatient, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care?

Some staff modified their communication with service users, e.g., reducing clinical jargon and focusing on the strengths of the service users [ 95 ]. Regular opportunities for service users and staff to discuss and reflect on information, concerns, and experiences were established. Staff received training in physical safety and de-escalation procedures; subsequently, the need for security staff on the ward decreased. Finally, in terms of staff wellbeing, staff PTSD symptoms increased with an increase in signs of burnout and length of time between attending trauma-informed care meetings [ 54 ].

Key findings

TIC approaches implemented in acute, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health settings were broad and varied. Studies that utilised either the Six Core Strategies model [ 71 ] or the Sanctuary Model [ 76 ] followed a clear structure to enact organisation and clinical change. Other studies implemented TIC models tailored to their specific settings, some with a particular emphasis on improving safety. The value of staff training was highlighted across studies, but the content of training was often described in limited detail, making it difficult to draw inferences around its comprehensiveness. Two principles from Sweeney and Taggart (2018) [ 6 ] that were often underrepresented in the TIC models were (i) recognising social traumas and the intersectionality of multiple traumas and (ii) working in partnership with trauma survivors to design, deliver and evaluate services. This indicates missed opportunities to use lived experience to develop services. Trauma itself was poorly defined, raising the question of whether TIC implementation can be truly meaningful without a clear framework of what trauma itself entails.

Service users were able to engage with their traumatic experiences and the implementation of TIC practice improved their ability to communicate their traumas. However, it is important to highlight that service users should not be required to share their experiences of trauma. The focus of TIC approaches in relation to empowering service users should also extend to giving them autonomy over when and how they disclose their traumatic experiences to staff [ 96 ]. While service users felt cared for, trusting, and trusted by staff working in TIC services, some distressing elements of service user experiences were not reflected in the TIC materials e.g., lack of access to housing or benefits, indicating a need for closer adaptation of TIC to the needs of service user populations.

Staff initially felt overwhelmed, anxious, criticised, and even reluctant at the introduction of TIC, though TIC positively influenced staff empathy, compassion, and wellbeing. Staff required time to build their skills and confidence, which once developed, led to pride and satisfaction in their roles. There were potential implications of delivering TIC for staff with histories of trauma also, e.g., providing staff with support and supervision to process those experiences. Future research could explore how trauma informed changes impact on staff turnover, a key concern in providing consistent care in inpatient and residential care settings.

Reductions in restraint and seclusion were observed, although the quality of evidence is limited as most studies are pre/post designs and lacked a comparison group. However, a broader question remains around whether services that continue to use restraint and seclusion (even in a reduced capacity) can be considered trauma informed.

There was a lack of economic evidence available, which highlights an area for future research. If TIC reduces rates of seclusion and restraint, reduces length of stays, as well as creates a more therapeutic environment (as reported in this review), this may have a positive economic impact, as conflict is costly [ 97 ] and patient satisfaction is associated with reduced costs [ 98 ]. There was also a lack of data on carers, perhaps due to our focus on specific settings, and very little evidence on hospital emergency departments (where care may be experienced as traumatising [ 99 ]), and on community-based crisis assessment services, home treatment, or acute day units, which future research could investigate.

Strengths and limitations

Our broad literature search retrieved evidence on TIC approaches in a variety of mental health settings. However, by nature of reviewing existing academic and grey literature, we are behind the curve of survivor thought and experience of TIC implementation. For example, information on the potential harms of poorly implemented TIC has been documented by people with lived experience [ 100 ], such as feeling required or coerced to confront their traumatic experiences. There was heterogeneity in the reporting of outcome measures across studies, limiting the generalisability of our conclusions. There was more data on residential mental health care settings compared to other settings, mirroring other review findings [ 101 ]; this may be due to their longer-term nature, which may be more amenable to the implementation and evaluation of TIC. This limits our understanding of TIC implementation and outcomes in other settings.

Although scoping review methodology does not require a quality assessment process, we noted significant methodological weaknesses across the included studies; they were primarily cross sectional, with few employing a control group or a randomised design, limiting our ability to draw causal conclusions about the impacts of TIC. Given the nature of this topic, particularly around mental healthcare reform, it is likely that work published in this area is subject to a range of potential biases that we were not able to examine in this study.

Implications for policy

A central tenet of TIC is empathy and understanding of the role of trauma in shaping mental health outcomes, which are positioned as being at the core of how mental health services can best support service users. Arguably, these principles should be a basic requirement of all mental health services, whether labelled as trauma informed or not. Introducing TIC into services may be a method by which basic practices can be integrated and maintained in a structured way [ 6 ]. This requires system-level change, which may be both time and financially resource intensive depending on, for example, the size of the organisation and staff, the time needed to design and provide training, and the policies and procedures which require revising. In theory, the introduction of TIC may challenge pre-existing clinical hierarchies through increased control and autonomy offered to service users and front-line staff, and so buy-in [ 58 ] and positive role modelling [ 65 ] from senior leaders within the service is vital for successful implementation.

Implications for practice

Delivering TIC in inpatient and residential settings requires clear and decisive leadership as well as clear staff roles [ 36 ]. In addition, TIC needs to be implemented, reviewed and evaluated collaboratively with service users to ensure it is delivering safe and appropriate care, otherwise services may continue to cause significant harm [ 100 ]. TIC could be included in pre-registration education across healthcare professions [ 102 , 103 ] and new starters may benefit from training as part of their inductions. Consistent staff supervision also supports the effective delivery of TIC [ 104 ]. These requirements result in a sustainability challenge as the creation and delivery of training is resource intensive, and staff turnover rates are high [ 105 ]. Clinicians should be aware of the intersection between trauma experiences, mental health, and social disadvantage, and the practical role that they may play at this intersection (e.g., providing supporting letters for housing or benefits). Clinical staff should also understand that issues relating to housing and welfare benefits, for example, can exacerbate mental health problems and responses to previous traumas, or even constitute traumatic experiences themselves [ 106 , 107 ]. Finally, clinicians should be conscious not to cause further harm through the delivery of TIC [ 100 ]; confronting and dealing with trauma should always be the choice of the service user, and receipt of TIC should not be dependent on service user willingness to engage with their traumatic experiences.

Implications for future research

We have identified significant evidence gaps around TIC implementation in non-inpatient acute care, including emergency, crisis teams, crisis houses, and acute day hospitals. Most evidence is concentrated within the USA, and there is a paucity of data on TIC elsewhere. Very few studies included control or comparison groups, crucially limiting our ability to determine the nature and strength of change due to TIC. With the development of other approaches to improving inpatient care, for example, Safewards [ 108 ], robust research methodologies must clarify the specific advantages of TIC. Future primary research could explore implementation of TIC in emergency and crisis mental health care settings, where it may be more difficult to implement a consistent and sustainable TIC approach as service users are engaged for shorter time periods. Future research could also consider the potential negative and harmful impacts of TIC. The present study could be extended to map the use of TIC in forensic settings, where poor mental health and experiences of trauma are also highly prevalent.

This scoping review has demonstrated the range of TIC approaches used in acute, crisis, and residential settings as well as a range of outcomes relating to service users and staff experiences, attitudes, and practises. TIC implementation requires commitment and strong leadership to enact organisational change, as well as appropriate training and supervision for staff and the involvement of service users in the design and delivery of approaches. Future research requires robust methods to accurately measure the impacts of TIC approaches and their potential benefits over existing care practices, through the utilisation of comparator conditions to TIC models. Research would also benefit from exploring how TIC impacts on carers; how trauma is understood in emergency services (settings that are frequently used by trauma survivors); and prioritising the expertise and views of those with lived experience with respect to how best to deliver TIC across mental health services.

Lived experience commentary

Written by LM and RRO.

As survivors of trauma from both within and outside mental health services, we welcome approaches which recognise its importance, and are pleased to see the range of perspectives which have been studied. We hope future research can engage with more work from outside the global north, which dominates in this paper.

However, from reading this literature, we do not know whether as patients we could always distinguish a trauma-informed service from any other - particularly given implementation challenges described in services with high levels of inconsistency, agency staff, new starters, and/or staff scepticism. At times trauma-informed care seems to be a means to an end which should already be universal, i.e., treating service users with respect and supporting our autonomy.

It does not particularly matter to us whether a service is trauma-informed on paper if the support staff change day by day and cannot or will not put the theory into practice. Nor does it matter that staff believe themselves to be validating our trauma, if they also retain power: if we can be physically held down; if the versions of ourselves written in their notes overwrite our autobiographies; if we have to surrender control of our most painful experiences in exchange for care. We have experienced some of these; we have heard about others happening to our peers, sometimes in the name of TIC (e.g. https://www.psychiatryisdrivingmemad.co.uk/post/trauma-informed-care-left-me-more-traumatised-than-ever ).

We welcome several studies showing reductions in restraint in trauma-informed environments (although note that this was not a universal finding). But we question whether a system founded on such violence can be anything other than traumatising in its own right. A version of TIC implemented in an under-resourced, fundamentally carceral system carries all the risks of harm associated with that system - with the added gaslighting of framing it as trauma-informed harm. As such, everyone involved in providing care they view as trauma-informed should consider what power over our stories and our bodies they are willing and able to give back.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Edwards DW, Scott CL, Yarvis RM, Paizis CL, Panizzon MS. Impulsiveness, impulsive aggression, personality disorder, and spousal violence. Violence Vict. 2003;18(1):3.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Trevillion K, Oram S, Feder G, Howard LM. Experiences of domestic violence and Mental Disorders: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12):e51740.

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Chen LP, Murad MH, Paras ML, Colbenson KM, Sattler AL, Goranson EN, et al. editors. Sexual abuse and lifetime diagnosis of psychiatric disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo clinic proceedings; 2010: Elsevier.

Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, Sethi D, Butchart A, Mikton C, et al. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(8):e356–e66.

Huang LN, Flatow R, Biggs T, Afayee S, Smith K, Clark T et al. SAMHSA’s Concept of Truama and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. 2014.

Sweeney A, Taggart D. Mis) understanding trauma-informed approaches in mental health. Taylor & Francis; 2018. pp. 383–7.

Cohodes EM, Kribakaran S, Odriozola P, Bakirci S, McCauley S, Hodges H, et al. Migration-related trauma and mental health among migrant children emigrating from Mexico and Central America to the United States: Effects on developmental neurobiology and implications for policy. Dev Psychobiol. 2021;63(6):e22158.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Khalifeh H, Moran P, Borschmann R, Dean K, Hart C, Hogg J, et al. Domestic and sexual violence against patients with severe mental illness. Psychol Med. 2015;45(4):875–86.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Oram S, Flynn SM, Shaw J, Appleby L, Howard LM. Mental illness and domestic homicide: a population-based descriptive study. Psychiatric Serv. 2013;64(10):1006–11.

Article Google Scholar

Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Br J psychiatry. 2010;197(5):378–85.

Fisher H, Morgan C, Dazzan P, Craig TK, Morgan K, Hutchinson G, et al. Gender differences in the association between childhood abuse and psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(4):319–25.

Inyang B, Gondal FJ, Abah GA, Dhandapani MM, Manne M, Khanna M et al. The role of childhood trauma in psychosis and schizophrenia: a systematic review. Cureus. 2022;14(1).

Bebbington PE, Bhugra D, Brugha T, Singleton N, Farrell M, Jenkins R, et al. Psychosis, victimisation and childhood disadvantage: evidence from the second British National Survey of Psychiatric Morbidity. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185(3):220–6.

Porter C, Palmier-Claus J, Branitsky A, Mansell W, Warwick H, Varese F. Childhood adversity and borderline personality disorder: a meta‐analysis. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2020;141(1):6–20.

Dale O, Sethi F, Stanton C, Evans S, Barnicot K, Sedgwick R, et al. Personality disorder services in England: findings from a national survey. BJPsych Bull. 2017;41(5):247–53.

Campbell K, Clarke K-A, Massey D, Lakeman R. Borderline personality disorder: to diagnose or not to diagnose? That is the question. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2020;29(5):972–81.

Evans S, Sethi F, Dale O, Stanton C, Sedgwick R, Doran M et al. Personality disorder service provision: a review of the recent literature. Mental Health Review Journal. 2017.

Ring D, Lawn S. Stigma perpetuation at the interface of mental health care: a review to compare patient and clinician perspectives of stigma and borderline personality disorder. J Mental Health. 2019:1–21.

Sheridan Rains L, Echave A, Rees J, Scott HR, Lever Taylor B, Broeckelmann E, et al. Service user experiences of community services for complex emotional needs: a qualitative thematic synthesis. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(4):e0248316.

Werbeloff N, Hilge Thygesen J, Hayes JF, Viding EM, Johnson S, Osborn DP. Childhood sexual abuse in patients with severe mental illness: demographic, clinical and functional correlates. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2021;143(6):495–502.

Coughlan H, Cannon M. Does childhood trauma play a role in the aetiology of psychosis? A review of recent evidence. BJPsych Adv. 2017;23(5):307–15.

Rafiq S, Campodonico C, Varese F. The relationship between childhood adversities and dissociation in severe mental illness: a meta-analytic review. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2018;138(6):509–25.

Matheson S, Shepherd AM, Pinchbeck R, Laurens K, Carr VJ. Childhood adversity in schizophrenia: a systematic meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2013;43(2):225–38.

Spandler H, McKeown M. Exploring the case for truth and reconciliation in mental health services. Mental Health Review Journal. 2017.

Rössler W. Stress, burnout, and job dissatisfaction in mental health workers. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin NeuroSci. 2012;262(2):65–9.

Johnson S, Dalton-Locke C, Baker J, Hanlon C, Salisbury TT, Fossey M, et al. Acute psychiatric care: approaches to increasing the range of services and improving access and quality of care. World Psychiatry. 2022;21(2):220–36.

Akther SF, Molyneaux E, Stuart R, Johnson S, Simpson A, Oram S. Patients’ experiences of assessment and detention under mental health legislation: systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. BJPsych Open. 2019;5(3).

Prytherch H, Cooke A, Marsh I. Coercion or collaboration: service-user experiences of risk management in hospital and a trauma-informed crisis house. Psychosis. 2021;13(2):93–104.

Cohen LJ. Psychiatric hospitalization as an experience of trauma. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1994;8(2):78–81.

Elliott DE, Bjelajac P, Fallot RD, Markoff LS, Reed BG. Trauma-informed or trauma‐denied: principles and implementation of trauma‐informed services for women. J community Psychol. 2005;33(4):461–77.

Sweeney A, Filson B, Kennedy A, Collinson L, Gillard S. A paradigm shift: relationships in trauma-informed mental health services. BJPsych Adv. 2018;24(5):319–33.

Substance A, Mental Health Services A. Substance abuse and Mental Health Administration’s (SAMSHA) concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. p. 27.

Google Scholar

Office for Health Improvement & Disparities. Working definition of trauma-informed practice. In: Disparities OfHI, editor.; 2022.

NHS Education for Scotland. Transforming Psychological Trauma: A Knowledge and Skills Framework for the Scottish Workforce. 2017.

Sweeney A. Trauma-informed mental healthcare in the UK: what is it and how can we further its development? Mental Health Review Journal. 2016;21(3):174–92.

Bryson SA, Gauvin E, Jamieson A, Rathgeber M, Faulkner-Gibson L, Bell S, et al. What are effective strategies for implementing trauma-informed care in youth inpatient psychiatric and residential treatment settings? A realist systematic review. Int J mental health Syst. 2017;11(1):1–16.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Miller NA, Najavits LM. Creating trauma-informed correctional care: a balance of goals and environment. Eur J psychotraumatology. 2012;3(1):17246.

Lloyd-Evans B, Slade M, Jagielska D, Johnson S. Residential alternatives to acute psychiatric hospital admission: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(2):109–17.

Niccols A, Milligan K, Sword W, Thabane L, Henderson J, Smith A. Integrated programs for mothers with substance abuse issues: a systematic review of studies reporting on parenting outcomes. Harm Reduct J. 2012;9(1):1–11.

Carpenter RA, Falkenburg J, White TP, Tracy DK. Crisis teams: systematic review of their effectiveness in practice. The Psychiatrist. 2013;37(7):232–7.

Iozzino L, Ferrari C, Large M, Nielssen O, De Girolamo G. Prevalence and risk factors of violence by psychiatric acute inpatients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(6):e0128536.

de Andrade D, Elphinston RA, Quinn C, Allan J, Hides L. The effectiveness of residential treatment services for individuals with substance use disorders: a systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;201:227–35.

Staniszewska S, Mockford C, Chadburn G, Fenton S-J, Bhui K, Larkin M, et al. Experiences of in-patient mental health services: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2019;214(6):329–38.

Stewart NA, Wilkinson-Tough M, Chambers GN. Psychological interventions for individuals with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder in forensic settings: a systematic review. J Forensic Psychiatr Psychol. 2019;30(5):744–93.

Alford M, O’Rourke S, Doyle P, Todd L. Examining the factors associated with impulsivity in forensic populations: a systematic review. Aggress Violent Beh. 2020;54:101409.

Alsuhaibani R, Smith DC, Lowrie R, Aljhani S, Paudyal V. Scope, quality and inclusivity of international clinical guidelines on mental health and substance abuse in relation to dual diagnosis, social and community outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):1–23.

Malik N, Facer-Irwin E, Dickson H, Bird A, MacManus D. The effectiveness of trauma-focused interventions in prison settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Violence, & Abuse: Trauma; 2021. p. 15248380211043890.

Covidence. Covidence systematic review software. 2017.

Chandler G. Reducing Use of Restraints and Seclusion to create a culture of Safety. J PsychoSoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2012;50:29–36.

Stamatopoulou V. Transitioning to a trauma informed forensic unit: staff perceptions of a shift in organisational culture. 2019.

Tompkins CNE, Neale J. Delivering trauma-informed treatment in a women-only residential rehabilitation service: qualitative study. Drugs: Educ Prev Policy. 2018;25(1):47–55.

Jacobowitz W, Moran C, Best C, Mensah L. Post-traumatic stress, trauma-informed care, and compassion fatigue in psychiatric hospital staff: a correlational study. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2015;36(11):890–9.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub; 2013.

Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC2000.

Kramer MG. Sanctuary in a residential treatment center: creating a therapeutic community of hope countering violence. Therapeutic communities: The International Journal of therapeutic communities. 2016.

Rivard J, Bloom S, McCorkle D, Abramovitz R. Preliminary results of a study examining the implementation and effects of a trauma recovery framework for youths in residential treatment. Therapeutic Community: The International Journal for Therapeutic and Supportive Organizations. 2005;26.

Hale R. Implementation of a trauma-informed Care Program for the reduction of Crisis Interventions. Walden University; 2019.

Black PJ, Woodworth M, Tremblay M, Carpenter T. A review of trauma-informed treatment for adolescents. Can Psychol. 2012;53(3):192.

Cook A, Blaustein M, van der Spinazzola J. Complex trauma in children and adolescents: white paper from the national child traumatic stress network complex trauma task force. Los Angeles: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress. 2003;35(5):390–8.

n der Kolk B. Posttraumatic stress disorder and the nature of trauma. Solomon MFaS, D.J, editors, editor. New York, NY2003.

Scheidlinger S. Group interventions for treatment of psychological trauma. New York. 2004:64.

Isobel S, Edwards C. Using trauma informed care as a nursing model of care in an acute inpatient mental health unit: a practice development process: TRAUMA INFORMED MODEL OF CARE. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2016;26.

Chandler G. From traditional inpatient to trauma-informed treatment: transferring control from staff to patient. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2008;14:363–71.

Gonshak AB. Analysis of trauma symptomology, trauma-informed care, and student-teacher relationships in a residential treatment center for female adolescents. Electronic Theses and Dissertations: University of Louisville; 2011.

Hale R, Wendler MC. Evidence-based practice: implementing trauma-informed care of children and adolescents in the inpatient psychiatric setting. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2020:1078390320980045.

Azeem MW, Aujla A, Rammerth M, Binsfeld G, Jones RB. Effectiveness of six core strategies based on trauma informed care in reducing seclusions and restraints at a child and adolescent psychiatric hospital. J Child Adolesc Psychiatric Nurs. 2011;24(1):11–5.

Azeem MW, Reddy B, Wudarsky M, Carabetta L, Gregory F, Sarofin M. Restraint reduction at a pediatric psychiatric hospital: a ten-year journey. J Child Adolesc Psychiatric Nurs. 2015;28(4):180–4.

Duxbury J, Baker J, Downe S, Jones F, Greenwood P, Thygesen H, et al. Minimising the use of physical restraint in acute mental health services: the outcome of a restraint reduction programme (‘REsTRAIN YOURSELF’). Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;95:40–8.

Huckshorn KA, CAP I, Director N. Six core strategies to reduce the use of seclusion and restraint planning tool. Washington, DC: National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors; 2005.

Korchmaros JD, Greene A, Murphy S. Implementing trauma-informed research-supported treatment: Fidelity, Feasibility, and acceptability. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 2021;38(1):101–13.

Prchal KM. Implementing a new treatment philosophy in a residential treatment center for children with severe emotional disturbances: a qualitative study. Columbia University; 2005.

Farragher B, Yanosy S. Creating a trauma-sensitive culture in residential treatment. Therapeutic Communities. 2005;26(1):97–113.

Rivard JC, McCorkle D, Duncan ME, Pasquale LE, Bloom SL, Abramovitz R. Implementing a trauma recovery framework for youths in residential treatment. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 2004;21(5):529–50.

Bloom SL. Creating sanctuary: toward the evolution of sane societies. Routledge; 2013.

Boel-Studt S. A quasi-experimental study of trauma-informed Psychiatric Residential treatment for children and adolescents. Res Social Work Pract. 2015;27.

Brown AD, McCauley K, Navalta CP, Saxe GN. Trauma systems therapy in residential settings: improving emotion regulation and the social environment of traumatized children and youth in congregate care. J family violence. 2013;28(7):693–703.

Forrest S, Gervais R, Lord KA, Sposato A, Martin L, Beserra K, et al. Building communities of care: a comprehensive model for trauma-informed youth capacity building and behavior management in residential services. Residential Treat Child Youth. 2018;35(4):265–85.

Cadiz S, Savage A, Bonavota D, Hollywood J, Butters E, Neary M, et al. The portal project: a layered approach to integrating trauma into alcohol and other drug treatment for women. Alcoholism Treat Q. 2005;22(3–4):121–39.

Zweben JE, Moses Y, Cohen JB, Price G, Chapman W, Lamb J. Enhancing family protective factors in residential treatment for substance use disorders. Child Welfare. 2015;94(5):145–66.

PubMed Google Scholar

Goetz SB, Taylor-Trujillo A. A change in culture: violence prevention in an acute behavioral health setting. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2012;18(2):96–103.

Wilder SS, Sorensen C. Essentials of aggression management in health care. Pearson; 2001.

Harris ME, Fallot RD. Using trauma theory to design service systems. Jossey-Bass/Wiley; 2001.

Ryle A, Poynton AM, Brockman BJ. Cognitive-analytic therapy: active participation in change: a new integration in brief psychotherapy. John Wiley & Sons; 1990.

Blair EW, Woolley S, Szarek BL, Mucha TF, Dutka O, Schwartz HI, et al. Reduction of seclusion and restraint in an inpatient psychiatric setting: a pilot study. Psychiatr Q. 2017;88(1):1–7.

Borckardt JJ, Madan A, Grubaugh AL, Danielson CK, Pelic CG, Hardesty SJ, et al. Systematic investigation of initiatives to reduce seclusion and restraint in a state psychiatric hospital. Psychiatric Serv. 2011;62(5):477–83.

Jones J. How distress is understood and communicated by women patients detained in high secure forensic healthcare, and how nurses interpret that distress: an exploration using a multi-perspective interpretative phenomenological analysis. University of Derby (United Kingdom); 2021.

Almvik R, Woods P. The Brøset Violence Checklist (BVC) and the prediction of inpatient violence: some preliminary results. Psychiatric Care. 1998;5:208–13.

Almvik R, Woods P, Rasmussen K. The Brøset Violence Checklist: sensitivity, specificity, and interrater reliability. J interpers Violence. 2000;15(12):1284–96.

Woods P, Almvik R. The Brøset violence checklist (BVC). Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2002;106:103–5.

Saakvitne KW, Gamble S, Pearlman LA, Lev BT. Risking connection: A training curriculum for working with survivors of childhood abuse. 2000.

Niimura J, Nakanishi M, Okumura Y, Kawano M, Nishida A. Effectiveness of 1-day trauma‐informed care training programme on attitudes in psychiatric hospitals: A pre–post study. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2019;28(4):980–8.

Aremu B, Hill PD, McNeal JM, Petersen MA, Swanberg D, Delaney KR. Implementation of trauma-informed care and brief solution-focused therapy: a quality improvement project aimed at increasing engagement on an inpatient psychiatric unit. J PsychoSoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2018;56(8):16–22.

Beckett P, Holmes D, Phipps M, Patton D, Molloy L. Trauma-informed care and practice: practice improvement strategies in an inpatient mental health ward. J PsychoSoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2017;55(10):34–8.

Tarzia L, Bohren MA, Cameron J, Garcia-Moreno C, O’Doherty L, Fiolet R, et al. Women’s experiences and expectations after disclosure of intimate partner abuse to a healthcare provider: a qualitative meta-synthesis. BMJ open. 2020;10(11):e041339.

Flood C, Bowers L, Parkin D. Estimating the costs of conflict and containment on adult acute inpatient psychiatric wards. Nurs Econ. 2008;26(5):325–32.