- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish?

- About Research Evaluation

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1. introduction, 4. synthesis, 4.1 principles of tdr quality, 5. conclusions, supplementary data, acknowledgements, defining and assessing research quality in a transdisciplinary context.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Brian M. Belcher, Katherine E. Rasmussen, Matthew R. Kemshaw, Deborah A. Zornes, Defining and assessing research quality in a transdisciplinary context, Research Evaluation , Volume 25, Issue 1, January 2016, Pages 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvv025

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Research increasingly seeks both to generate knowledge and to contribute to real-world solutions, with strong emphasis on context and social engagement. As boundaries between disciplines are crossed, and as research engages more with stakeholders in complex systems, traditional academic definitions and criteria of research quality are no longer sufficient—there is a need for a parallel evolution of principles and criteria to define and evaluate research quality in a transdisciplinary research (TDR) context. We conducted a systematic review to help answer the question: What are appropriate principles and criteria for defining and assessing TDR quality? Articles were selected and reviewed seeking: arguments for or against expanding definitions of research quality, purposes for research quality evaluation, proposed principles of research quality, proposed criteria for research quality assessment, proposed indicators and measures of research quality, and proposed processes for evaluating TDR. We used the information from the review and our own experience in two research organizations that employ TDR approaches to develop a prototype TDR quality assessment framework, organized as an evaluation rubric. We provide an overview of the relevant literature and summarize the main aspects of TDR quality identified there. Four main principles emerge: relevance, including social significance and applicability; credibility, including criteria of integration and reflexivity, added to traditional criteria of scientific rigor; legitimacy, including criteria of inclusion and fair representation of stakeholder interests, and; effectiveness, with criteria that assess actual or potential contributions to problem solving and social change.

Contemporary research in the social and environmental realms places strong emphasis on achieving ‘impact’. Research programs and projects aim to generate new knowledge but also to promote and facilitate the use of that knowledge to enable change, solve problems, and support innovation ( Clark and Dickson 2003 ). Reductionist and purely disciplinary approaches are being augmented or replaced with holistic approaches that recognize the complex nature of problems and that actively engage within complex systems to contribute to change ‘on the ground’ ( Gibbons et al. 1994 ; Nowotny, Scott and Gibbons 2001 , Nowotny, Scott and Gibbons 2003 ; Klein 2006 ; Hemlin and Rasmussen 2006 ; Chataway, Smith and Wield 2007 ; Erno-Kjolhede and Hansson 2011 ). Emerging fields such as sustainability science have developed out of a need to address complex and urgent real-world problems ( Komiyama and Takeuchi 2006 ). These approaches are inherently applied and transdisciplinary, with explicit goals to contribute to real-world solutions and strong emphasis on context and social engagement ( Kates 2000 ).

While there is an ongoing conceptual and theoretical debate about the nature of the relationship between science and society (e.g. Hessels 2008 ), we take a more practical starting point based on the authors’ experience in two research organizations. The first author has been involved with the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) for almost 20 years. CIFOR, as part of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), began a major transformation in 2010 that shifted the emphasis from a primary focus on delivering high-quality science to a focus on ‘…producing, assembling and delivering, in collaboration with research and development partners, research outputs that are international public goods which will contribute to the solution of significant development problems that have been identified and prioritized with the collaboration of developing countries.’ ( CGIAR 2011 ). It was always intended that CGIAR research would be relevant to priority development and conservation issues, with emphasis on high-quality scientific outputs. The new approach puts much stronger emphasis on welfare and environmental results; research centers, programs, and individual scientists now assume shared responsibility for achieving development outcomes. This requires new ways of working, with more and different kinds of partnerships and more deliberate and strategic engagement in social systems.

Royal Roads University (RRU), the home institute of all four authors, is a relatively new (created in 1995) public university in Canada. It is deliberately interdisciplinary by design, with just two faculties (Faculty of Social and Applied Science; Faculty of Management) and strong emphasis on problem-oriented research. Faculty and student research is typically ‘applied’ in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2012) sense of ‘original investigation undertaken in order to acquire new knowledge … directed primarily towards a specific practical aim or objective’.

An increasing amount of the research done within both of these organizations can be classified as transdisciplinary research (TDR). TDR crosses disciplinary and institutional boundaries, is context specific, and problem oriented ( Klein 2006 ; Carew and Wickson 2010 ). It combines and blends methodologies from different theoretical paradigms, includes a diversity of both academic and lay actors, and is conducted with a range of research goals, organizational forms, and outputs ( Klein 2006 ; Boix-Mansilla 2006a ; Erno-Kjolhede and Hansson 2011 ). The problem-oriented nature of TDR and the importance placed on societal relevance and engagement are broadly accepted as defining characteristics of TDR ( Carew and Wickson 2010 ).

The experience developing and using TDR approaches at CIFOR and RRU highlights the need for a parallel evolution of principles and criteria for evaluating research quality in a TDR context. Scientists appreciate and often welcome the need and the opportunity to expand the reach of their research, to contribute more effectively to change processes. At the same time, they feel the pressure of added expectations and are looking for guidance.

In any activity, we need principles, guidelines, criteria, or benchmarks that can be used to design the activity, assess its potential, and evaluate its progress and accomplishments. Effective research quality criteria are necessary to guide the funding, management, ongoing development, and advancement of research methods, projects, and programs. The lack of quality criteria to guide and assess research design and performance is seen as hindering the development of transdisciplinary approaches ( Bergmann et al. 2005 ; Feller 2006 ; Chataway, Smith and Wield 2007 ; Ozga 2008 ; Carew and Wickson 2010 ; Jahn and Keil 2015 ). Appropriate quality evaluation is essential to ensure that research receives support and funding, and to guide and train researchers and managers to realize high-quality research ( Boix-Mansilla 2006a ; Klein 2008 ; Aagaard-Hansen and Svedin 2009 ; Carew and Wickson 2010 ).

Traditional disciplinary research is built on well-established methodological and epistemological principles and practices. Within disciplinary research, quality has been defined narrowly, with the primary criteria being scientific excellence and scientific relevance ( Feller 2006 ; Chataway, Smith and Wield 2007 ; Erno-Kjolhede and Hansson 2011 ). Disciplines have well-established (often implicit) criteria and processes for the evaluation of quality in research design ( Erno-Kjolhede and Hansson 2011 ). TDR that is highly context specific, problem oriented, and includes nonacademic societal actors in the research process is challenging to evaluate ( Wickson, Carew and Russell 2006 ; Aagaard-Hansen and Svedin 2009 ; Andrén 2010 ; Carew and Wickson 2010 ; Huutoniemi 2010 ). There is no one definition or understanding of what constitutes quality, nor a set guide for how to do TDR ( Lincoln 1995 ; Morrow 2005 ; Oberg 2008 ; Andrén 2010 ; Huutoniemi 2010 ). When epistemologies and methods from more than one discipline are used, disciplinary criteria may be insufficient and criteria from more than one discipline may be contradictory; cultural conflicts can arise as a range of actors use different terminology for the same concepts or the same terminology for different concepts ( Chataway, Smith and Wield 2007 ; Oberg 2008 ).

Current research evaluation approaches as applied to individual researchers, programs, and research units are still based primarily on measures of academic outputs (publications and the prestige of the publishing journal), citations, and peer assessment ( Boix-Mansilla 2006a ; Feller 2006 ; Erno-Kjolhede and Hansson 2011 ). While these indicators of research quality remain relevant, additional criteria are needed to address the innovative approaches and the diversity of actors, outputs, outcomes, and long-term social impacts of TDR. It can be difficult to find appropriate outlets for TDR publications simply because the research does not meet the expectations of traditional discipline-oriented journals. Moreover, a wider range of inputs and of outputs means that TDR may result in fewer academic outputs. This has negative implications for transdisciplinary researchers, whose performance appraisals and long-term career progression are largely governed by traditional publication and citation-based metrics of evaluation. Research managers, peer reviewers, academic committees, and granting agencies all struggle with how to evaluate and how to compare TDR projects ( ex ante or ex post ) in the absence of appropriate criteria to address epistemological and methodological variability. The extent of engagement of stakeholders 1 in the research process will vary by project, from information sharing through to active collaboration ( Brandt et al. 2013) , but at any level, the involvement of stakeholders adds complexity to the conceptualization of quality. We need to know what ‘good research’ is in a transdisciplinary context.

As Tijssen ( 2003 : 93) put it: ‘Clearly, in view of its strategic and policy relevance, developing and producing generally acceptable measures of “research excellence” is one of the chief evaluation challenges of the years to come’. Clear criteria are needed for research quality evaluation to foster excellence while supporting innovation: ‘A principal barrier to a broader uptake of TD research is a lack of clarity on what good quality TD research looks like’ ( Carew and Wickson 2010 : 1154). In the absence of alternatives, many evaluators, including funding bodies, rely on conventional, discipline-specific measures of quality which do not address important aspects of TDR.

There is an emerging literature that reviews, synthesizes, or empirically evaluates knowledge and best practice in research evaluation in a TDR context and that proposes criteria and evaluation approaches ( Defila and Di Giulio 1999 ; Bergmann et al. 2005 ; Wickson, Carew and Russell 2006 ; Klein 2008 ; Carew and Wickson 2010 ; ERIC 2010; de Jong et al. 2011 ; Spaapen and Van Drooge 2011 ). Much of it comes from a few fields, including health care, education, and evaluation; little comes from the natural resource management and sustainability science realms, despite these areas needing guidance. National-scale reviews have begun to recognize the need for broader research evaluation criteria but have had difficulty dealing with it and have made little progress in addressing it ( Donovan 2008 ; KNAW 2009 ; REF 2011 ; ARC 2012 ; TEC 2012 ). A summary of the national reviews that we reviewed in the development of this research is provided in Supplementary Appendix 1 . While there are some published evaluation schemes for TDR and interdisciplinary research (IDR), there is ‘substantial variation in the balance different authors achieve between comprehensiveness and over-prescription’ ( Wickson and Carew 2014 : 256) and still a need to develop standardized quality criteria that are ‘uniquely flexible to provide valid, reliable means to evaluate and compare projects, while not stifling the evolution and responsiveness of the approach’ ( Wickson and Carew 2014 : 256).

There is a need and an opportunity to synthesize current ideas about how to define and assess quality in TDR. To address this, we conducted a systematic review of the literature that discusses the definitions of research quality as well as the suggested principles and criteria for assessing TDR quality. The aim is to identify appropriate principles and criteria for defining and measuring research quality in a transdisciplinary context and to organize those principles and criteria as an evaluation framework.

The review question was: What are appropriate principles, criteria, and indicators for defining and assessing research quality in TDR?

This article presents the method used for the systematic review and our synthesis, followed by key findings. Theoretical concepts about why new principles and criteria are needed for TDR, along with associated discussions about evaluation process are presented. A framework, derived from our synthesis of the literature, of principles and criteria for TDR quality evaluation is presented along with guidance on its application. Finally, recommendations for next steps in this research and needs for future research are discussed.

2.1 Systematic review

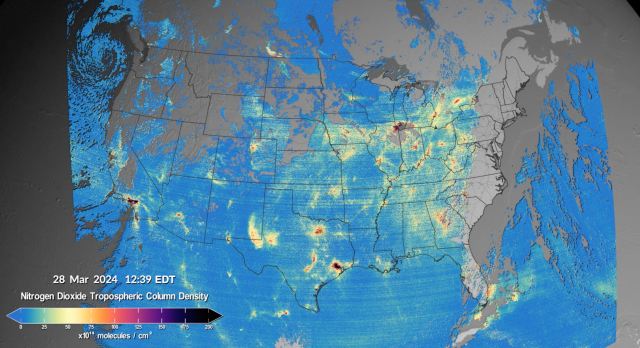

Systematic review is a rigorous, transparent, and replicable methodology that has become widely used to inform evidence-based policy, management, and decision making ( Pullin and Stewart 2006 ; CEE 2010). Systematic reviews follow a detailed protocol with explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure a repeatable and comprehensive review of the target literature. Review protocols are shared and often published as peer reviewed articles before undertaking the review to invite critique and suggestions. Systematic reviews are most commonly used to synthesize knowledge on an empirical question by collating data and analyses from a series of comparable studies, though methods used in systematic reviews are continually evolving and are increasingly being developed to explore a wider diversity of questions ( Chandler 2014 ). The current study question is theoretical and methodological, not empirical. Nevertheless, with a diverse and diffuse literature on the quality of TDR, a systematic review approach provides a method for a thorough and rigorous review. The protocol is published and available at http://www.cifor.org/online-library/browse/view-publication/publication/4382.html . A schematic diagram of the systematic review process is presented in Fig. 1 .

Search process.

2.2 Search terms

Search terms were designed to identify publications that discuss the evaluation or assessment of quality or excellence 2 of research 3 that is done in a TDR context. Search terms are listed online in Supplementary Appendices 2 and 3 . The search strategy favored sensitivity over specificity to ensure that we captured the relevant information.

2.3 Databases searched

ISI Web of Knowledge (WoK) and Scopus were searched between 26 June 2013 and 6 August 2013. The combined searches yielded 15,613 unique citations. Additional searches to update the first searchers were carried out in June 2014 and March 2015, for a total of 19,402 titles scanned. Google Scholar (GS) was searched separately by two reviewers during each search period. The first reviewer’s search was done on 2 September 2013 (Search 1) and 3 September 2013 (Search 2), yielding 739 and 745 titles, respectively. The second reviewer’s search was done on 19 November 2013 (Search 1) and 25 November 2013 (Search 2), yielding 769 and 774 titles, respectively. A third search done on 17 March 2015 by one reviewer yielded 98 new titles. Reviewers found high redundancy between the WoK/Scopus searches and the GS searches.

2.4 Targeted journal searches

Highly relevant journals, including Research Evaluation, Evaluation and Program Planning, Scientometrics, Research Policy, Futures, American Journal of Evaluation, Evaluation Review, and Evaluation, were comprehensively searched using broader, more inclusive search strings that would have been unmanageable for the main database search.

2.5 Supplementary searches

References in included articles were reviewed to identify additional relevant literature. td-net’s ‘Tour d’Horizon of Literature’, lists important inter- and transdisciplinary publications collected through an invitation to experts in the field to submit publications ( td-net 2014 ). Six additional articles were identified via supplementary search.

2.6 Limitations of coverage

The review was limited to English-language published articles and material available through internet searches. There was no systematic way to search the gray (unpublished) literature, but relevant material identified through supplementary searches was included.

2.7 Inclusion of articles

This study sought articles that review, critique, discuss, and/or propose principles, criteria, indicators, and/or measures for the evaluation of quality relevant to TDR. As noted, this yielded a large number of titles. We then selected only those articles with an explicit focus on the meaning of IDR and/or TDR quality and how to achieve, measure or evaluate it. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed through an iterative process of trial article screening and discussion within the research team. Through this process, inter-reviewer agreement was tested and strengthened. Inclusion criteria are listed in Tables 1 and 2 .

Inclusion criteria for title and abstract screening

Inclusion criteria for abstract and full article screening

Article screening was done in parallel by two reviewers in three rounds: (1) title, (2) abstract, and (3) full article. In cases of uncertainty, papers were included to the next round. Final decisions on inclusion of contested papers were made by consensus among the four team members.

2.8 Critical appraisal

In typical systematic reviews, individual articles are appraised to ensure that they are adequate for answering the research question and to assess the methods of each study for susceptibility to bias that could influence the outcome of the review (Petticrew and Roberts 2006). Most papers included in this review are theoretical and methodological papers, not empirical studies. Most do not have explicit methods that can be appraised with existing quality assessment frameworks. Our critical appraisal considered four criteria adapted from Spencer et al. (2003): (1) relevance to the review question, (2) clarity and logic of how information in the paper was generated, (3) significance of the contribution (are new ideas offered?), and (4) generalizability (is the context specified; do the ideas apply in other contexts?). Disagreements were discussed to reach consensus.

2.9 Data extraction and management

The review sought information on: arguments for or against expanding definitions of research quality, purposes for research quality evaluation, principles of research quality, criteria for research quality assessment, indicators and measures of research quality, and processes for evaluating TDR. Four reviewers independently extracted data from selected articles using the parameters listed in Supplementary Appendix 4 .

2.10 Data synthesis and TDR framework design

Our aim was to synthesize ideas, definitions, and recommendations for TDR quality criteria into a comprehensive and generalizable framework for the evaluation of quality in TDR. Key ideas were extracted from each article and summarized in an Excel database. We classified these ideas into themes and ultimately into overarching principles and associated criteria of TDR quality organized as a rubric ( Wickson and Carew 2014 ). Definitions of each principle and criterion were developed and rubric statements formulated based on the literature and our experience. These criteria (adjusted appropriately to be applied ex ante or ex post ) are intended to be used to assess a TDR project. The reviewer should consider whether the project fully satisfies, partially satisfies, or fails to satisfy each criterion. More information on application is provided in Section 4.3 below.

We tested the framework on a set of completed RRU graduate theses that used transdisciplinary approaches, with an explicit problem orientation and intent to contribute to social or environmental change. Three rounds of testing were done, with revisions after each round to refine and improve the framework.

3.1 Overview of the selected articles

Thirty-eight papers satisfied the inclusion criteria. A wide range of terms are used in the selected papers, including: cross-disciplinary; interdisciplinary; transdisciplinary; methodological pluralism; mode 2; triple helix; and supradisciplinary. Eight included papers specifically focused on sustainability science or TDR in natural resource management, or identified sustainability research as a growing TDR field that needs new forms of evaluation ( Cash et al. 2002 ; Bergmann et al. 2005 ; Chataway, Smith and Wield 2007 ; Spaapen, Dijstelbloem and Wamelink 2007 ; Andrén 2010 ; Carew and Wickson 2010 ; Lang et al. 2012 ; Gaziulusoy and Boyle 2013 ). Carew and Wickson (2010) build on the experience in the TDR realm to propose criteria and indicators of quality for ‘responsible research and innovation’.

The selected articles are written from three main perspectives. One set is primarily interested in advancing TDR approaches. These papers recognize the need for new quality measures to encourage and promote high-quality research and to overcome perceived biases against TDR approaches in research funding and publishing. A second set of papers is written from an evaluation perspective, with a focus on improving evaluation of TDR. The third set is written from the perspective of qualitative research characterized by methodological pluralism, with many characteristics and issues relevant to TDR approaches.

The majority of the articles focus at the project scale, some at the organization level, and some do not specify. Some articles explicitly focus on ex ante evaluation (e.g. proposal evaluation), others on ex post evaluation, and many are not explicit about the project stage they are concerned with. The methods used in the reviewed articles include authors’ reflection and opinion, literature review, expert consultation, document analysis, and case study. Summaries of report characteristics are available online ( Supplementary Appendices 5–8 ). Eight articles provide comprehensive evaluation frameworks and quality criteria specifically for TDR and research-in-context. The rest of the articles discuss aspects of quality related to TDR and recommend quality definitions, criteria, and/or evaluation processes.

3.2 The need for quality criteria and evaluation methods for TDR

Many of the selected articles highlight the lack of widely agreed principles and criteria of TDR quality. They note that, in the absence of TDR quality frameworks, disciplinary criteria are used ( Morrow 2005 ; Boix-Mansilla 2006a , b ; Feller 2006 ; Klein 2006 , 2008 ; Wickson, Carew and Russell 2006 ; Scott 2007 ; Spaapen, Dijstelbloem and Wamelink 2007 ; Oberg 2008 ; Erno-Kjolhede and Hansson 2011 ), and evaluations are often carried out by reviewers who lack cross-disciplinary experience and do not have a shared understanding of quality ( Aagaard-Hansen and Svedin 2009 ). Quality is discussed by many as a relative concept, developed within disciplines, and therefore defined and understood differently in each field ( Morrow 2005 ; Klein 2006 ; Oberg 2008 ; Mitchell and Willets 2009 ; Huutoniemi 2010 ; Hellstrom 2011 ). Jahn and Keil (2015) point out the difficulty of creating a common set of quality criteria for TDR in the absence of a standard agreed-upon definition of TDR. Many of the selected papers argue the need to move beyond narrowly defined ideas of ‘scientific excellence’ to incorporate a broader assessment of quality which includes societal relevance ( Hemlin and Rasmussen 2006 ; Chataway, Smith and Wield 2007 ; Ozga 2007 ; Spaapen, Dijstelbloem and Wamelink 2007 ). This shift includes greater focus on research organization, research process, and continuous learning, rather than primarily on research outputs ( Hemlin and Rasmussen 2006 ; de Jong et al. 2011 ; Wickson and Carew 2014 ; Jahn and Keil 2015 ). This responds to and reflects societal expectations that research should be accountable and have demonstrated utility ( Cloete 1997 ; Defila and Di Giulio 1999 ; Wickson, Carew and Russell 2006 ; Spaapen, Dijstelbloem and Wamelink 2007 ; Stige 2009 ).

A central aim of TDR is to achieve socially relevant outcomes, and TDR quality criteria should demonstrate accountability to society ( Cloete 1997 ; Hemlin and Rasmussen 2006 ; Chataway, Smith and Wield 2007 ; Ozga 2007 ; Spaapen, Dijstelbloem and Wamelink 2007 ; de Jong et al. 2011 ). Integration and mutual learning are a core element of TDR; it is not enough to transcend boundaries and incorporate societal knowledge but, as Carew and Wickson ( 2010 : 1147) summarize: ‘…the TD researcher needs to put effort into integrating these potentially disparate knowledges with a view to creating useable knowledge. That is, knowledge that can be applied in a given problem context and has some prospect of producing desired change in that context’. The inclusion of societal actors in the research process, the unique and often dispersed organization of research teams, and the deliberate integration of different traditions of knowledge production all fall outside of conventional assessment criteria ( Feller 2006 ).

Not only do the range of criteria need to be updated, expanded, agreed upon, and assumptions made explicit ( Boix-Mansilla 2006a ; Klein 2006 ; Scott 2007 ) but, given the specific problem orientation of TDR, reviewers beyond disciplinary academic peers need to be included in the assessment of quality ( Cloete 1997 ; Scott 2007 ; Spappen et al. 2007 ; Klein 2008 ). Several authors discuss the lack of reviewers with strong cross-disciplinary experience ( Aagaard-Hansen and Svedin 2009 ) and the lack of common criteria, philosophical foundations, and language for use by peer reviewers ( Klein 2008 ; Aagaard-Hansen and Svedin 2009 ). Peer review of TDR could be improved with explicit TDR quality criteria, and appropriate processes in place to ensure clear dialog between reviewers.

Finally, there is the need for increased emphasis on evaluation as part of the research process ( Bergmann et al. 2005 ; Hemlin and Rasmussen 2006 ; Meyrick 2006 ; Chataway, Smith and Wield 2007 ; Stige, Malterud and Midtgarden 2009 ; Hellstrom 2011 ; Lang et al. 2012 ; Wickson and Carew 2014 ). This is particularly true in large, complex, problem-oriented research projects. Ongoing monitoring of the research organization and process contributes to learning and adaptive management while research is underway and so helps improve quality. As stated by Wickson and Carew ( 2014 : 262): ‘We believe that in any process of interpreting, rearranging and/or applying these criteria, open negotiation on their meaning and application would only positively foster transformative learning, which is a valued outcome of good TD processes’.

3.3 TDR quality criteria and assessment approaches

Many of the papers provide quality criteria and/or describe constituent parts of quality. Aagaard-Hansen and Svedin (2009) define three key aspects of quality: societal relevance, impact, and integration. Meyrick (2006) states that quality research is transparent and systematic. Boaz and Ashby (2003) describe quality in four dimensions: methodological quality, quality of reporting, appropriateness of methods, and relevance to policy and practice. Although each article deconstructs quality in different ways and with different foci and perspectives, there is significant overlap and recurring themes in the papers reviewed. There is a broadly shared perspective that TDR quality is a multidimensional concept shaped by the specific context within which research is done ( Spaapen, Dijstelbloem and Wamelink 2007 ; Klein 2008 ), making a universal definition of TDR quality difficult or impossible ( Huutoniemi 2010 ).

Huutoniemi (2010) identifies three main approaches to conceptualizing quality in IDR and TDR: (1) using existing disciplinary standards adapted as necessary for IDR; (2) building on the quality standards of disciplines while fundamentally incorporating ways to deal with epistemological integration, problem focus, context, stakeholders, and process; and (3) radical departure from any disciplinary orientation in favor of external, emergent, context-dependent quality criteria that are defined and enacted collaboratively by a community of users.

The first approach is prominent in current research funding and evaluation protocols. Conservative approaches of this kind are criticized for privileging disciplinary research and for failing to provide guidance and quality control for transdisciplinary projects. The third approach would ‘undermine the prevailing status of disciplinary standards in the pursuit of a non-disciplinary, integrated knowledge system’ ( Huutoniemi 2010 : 313). No predetermined quality criteria are offered, only contextually embedded criteria that need to be developed within a specific research project. To some extent, this is the approach taken by Spaapen, Dijstelbloem and Wamelink (2007) and de Jong et al. (2011) . Such a sui generis approach cannot be used to compare across projects. Most of the reviewed papers take the second approach, and recommend TDR quality criteria that build on a disciplinary base.

Eight articles present comprehensive frameworks for quality evaluation, each with a unique approach, perspective, and goal. Two of these build comprehensive lists of criteria with associated questions to be chosen based on the needs of the particular research project ( Defila and Di Giulio 1999 ; Bergmann et al. 2005 ). Wickson and Carew (2014) develop a reflective heuristic tool with questions to guide researchers through ongoing self-evaluation. They also list criteria for external evaluation and to compare between projects. Spaapen, Dijstelbloem and Wamelink (2007) design an approach to evaluate a research project against its own goals and is not meant to compare between projects. Wickson and Carew (2014) developed a comprehensive rubric for the evaluation of Research and Innovation that builds of their extensive previous work in TDR. Finally, Lang et al. (2012) , Mitchell and Willets (2009) , and Jahn and Keil (2015) develop criteria checklists that can be applied across transdisciplinary projects.

Bergmann et al. (2005) and Carew and Wickson (2010) organize their frameworks into managerial elements of the research project, concerning problem context, participation, management, and outcomes. Lang et al. (2012) and Defila and Di Giulio (1999) focus on the chronological stages in the research process and identify criteria at each stage. Mitchell and Willets (2009) , , with a focus on doctoral s tudies, adapt standard dissertation evaluation criteria to accommodate broader, pluralistic, and more complex studies. Spaapen, Dijstelbloem and Wamelink (2007) focus on evaluating ‘research-in-context’. Wickson and Carew (2014) created a rubric based on criteria that span the research process, stages, and all actors included. Jahn and Keil (2015) organized their quality criteria into three categories of quality including: quality of the research problems, quality of the research process, and quality of the research results.

The remaining papers highlight key themes that must be considered in TDR evaluation. Dominant themes include: engagement with problem context, collaboration and inclusion of stakeholders, heightened need for explicit communication and reflection, integration of epistemologies, recognition of diverse outputs, the focus on having an impact, and reflexivity and adaptation throughout the process. The focus on societal problems in context and the increased engagement of stakeholders in the research process introduces higher levels of complexity that cannot be accommodated by disciplinary standards ( Defila and Di Giulio 1999 ; Bergmann et al. 2005 ; Wickson, Carew and Russell 2006 ; Spaapen, Dijstelbloem and Wamelink 2007 ; Klein 2008 ).

Finally, authors discuss process ( Defila and Di Giulio 1999 ; Bergmann et al. 2005 ; Boix-Mansilla 2006b ; Spaapen, Dijstelbloem and Wamelink 2007 ) and utilitarian values ( Hemlin 2006 ; Ernø-Kjølhede and Hansson 2011 ; Bornmann 2013 ) as essential aspects of quality in TDR. Common themes include: (1) the importance of formative and process-oriented evaluation ( Bergmann et al. 2005 ; Hemlin 2006 ; Stige 2009 ); (2) emphasis on the evaluation process itself (not just criteria or outcomes) and reflexive dialog for learning ( Bergmann et al. 2005 ; Boix-Mansilla 2006b ; Klein 2008 ; Oberg 2008 ; Stige, Malterud and Midtgarden 2009 ; Aagaard-Hansen and Svedin 2009 ; Carew and Wickson 2010 ; Huutoniemi 2010 ); (3) the need for peers who are experienced and knowledgeable about TDR for fair peer review ( Boix-Mansilla 2006a , b ; Klein 2006 ; Hemlin 2006 ; Scott 2007 ; Aagaard-Hansen and Svedin 2009 ); (4) the inclusion of stakeholders in the evaluation process ( Bergmann et al. 2005 ; Scott 2007 ; Andréen 2010 ); and (5) the importance of evaluations that are built in-context ( Defila and Di Giulio 1999 ; Feller 2006 ; Spaapen, Dijstelbloem and Wamelink 2007 ; de Jong et al. 2011 ).

While each reviewed approach offers helpful insights, none adequately fulfills the need for a broad and adaptable framework for assessing TDR quality. Wickson and Carew ( 2014 : 257) highlight the need for quality criteria that achieve balance between ‘comprehensiveness and over-prescription’: ‘any emerging quality criteria need to be concrete enough to provide real guidance but flexible enough to adapt to the specificities of varying contexts’. Based on our experience, such a framework should be:

Comprehensive: It should accommodate the main aspects of TDR, as identified in the review.

Time/phase adaptable: It should be applicable across the project cycle.

Scalable: It should be useful for projects of different scales.

Versatile: It should be useful to researchers and collaborators as a guide to research design and management, and to internal and external reviews and assessors.

Comparable: It should allow comparison of quality between and across projects/programs.

Reflexive: It should encourage and facilitate self-reflection and adaptation based on ongoing learning.

In this section, we synthesize the key principles and criteria of quality in TDR that were identified in the reviewed literature. Principles are the essential elements of high-quality TDR. Criteria are the conditions that need to be met in order to achieve a principle. We conclude by providing a framework for the evaluation of quality in TDR ( Table 3 ) and guidance for its application.

Transdisciplinary research quality assessment framework

a Research problems are the particular topic, area of concern, question to be addressed, challenge, opportunity, or focus of the research activity. Research problems are related to the societal problem but take on a specific focus, or framing, within a societal problem.

b Problem context refers to the social and environmental setting(s) that gives rise to the research problem, including aspects of: location; culture; scale in time and space; social, political, economic, and ecological/environmental conditions; resources and societal capacity available; uncertainty, complexity, and novelty associated with the societal problem; and the extent of agency that is held by stakeholders ( Carew and Wickson 2010 ).

c Words such as ‘appropriate’, ‘suitable’, and ‘adequate’ are used deliberately to allow for quality criteria to be flexible and specific enough to the needs of individual research projects ( Oberg 2008 ).

d Research process refers to the series of decisions made and actions taken throughout the entire duration of the research project and encompassing all aspects of the research project.

e Reflexivity refers to an iterative process of formative, critical reflection on the important interactions and relationships between a research project’s process, context, and product(s).

f In an ex ante evaluation, ‘evidence of’ would be replaced with ‘potential for’.

There is a strong trend in the reviewed articles to recognize the need for appropriate measures of scientific quality (usually adapted from disciplinary antecedants), but also to consider broader sets of criteria regarding the societal significance and applicability of research, and the need for engagement and representation of stakeholder values and knowledge. Cash et al. (2002) nicely conceptualize three key aspects of effective sustainability research as: salience (or relevance), credibility, and legitimacy. These are presented as necessary attributes for research to successfully produce transferable, useful information that can cross boundaries between disciplines, across scales, and between science and society. Many of the papers also refer to the principle that high-quality TDR should be effective in terms of contributing to the solution of problems. These four principles are discussed in the following sections.

4.1.1 Relevance

Relevance is the importance, significance, and usefulness of the research project's objectives, process, and findings to the problem context and to society. This includes the appropriateness of the timing of the research, the questions being asked, the outputs, and the scale of the research in relation to the societal problem being addressed. Good-quality TDR addresses important social/environmental problems and produces knowledge that is useful for decision making and problem solving ( Cash et al. 2002 ; Klein 2006 ). As Erno-Kjolhede and Hansson ( 2011 : 140) explain, quality ‘is first and foremost about creating results that are applicable and relevant for the users of the research’. Researchers must demonstrate an in-depth knowledge of and ongoing engagement with the problem context in which their research takes place ( Wickson, Carew and Russell 2006 ; Stige, Malterud and Midtgarden 2009 ; Mitchell and Willets 2009 ). From the early steps of problem formulation and research design through to the appropriate and effective communication of research findings, the applicability and relevance of the research to the societal problem must be explicitly stated and incorporated.

4.1.2 Credibility

Credibility refers to whether or not the research findings are robust and the knowledge produced is scientifically trustworthy. This includes clear demonstration that the data are adequate, with well-presented methods and logical interpretations of findings. High-quality research is authoritative, transparent, defensible, believable, and rigorous. This is the traditional purview of science, and traditional disciplinary criteria can be applied in TDR evaluation to an extent. Additional and modified criteria are needed to address the integration of epistemologies and methodologies and the development of novel methods through collaboration, the broad preparation and competencies required to carry out the research, and the need for reflection and adaptation when operating in complex systems. Having researchers actively engaged in the problem context and including extra-scientific actors as part of the research process helps to achieve relevance and legitimacy of the research; it also adds complexity and heightened requirements of transparency, reflection, and reflexivity to ensure objective, credible research is carried out.

Active reflexivity is a criterion of credibility of TDR that may seem to contradict more rigid disciplinary methodological traditions ( Carew and Wickson 2010 ). Practitioners of TDR recognize that credible work in these problem-oriented fields requires active reflexivity, epitomized by ongoing learning, flexibility, and adaptation to ensure the research approach and objectives remain relevant and fit-to-purpose ( Lincoln 1995 ; Bergmann et al. 2005 ; Wickson, Carew and Russell 2006 ; Mitchell and Willets 2009 ; Andreén 2010 ; Carew and Wickson 2010 ; Wickson and Carew 2014 ). Changes made during the research process must be justified and reported transparently and explicitly to maintain credibility.

The need for critical reflection on potential bias and limitations becomes more important to maintain credibility of research-in-context ( Lincoln 1995 ; Bergmann et al. 2005 ; Mitchell and Willets 2009 ; Stige, Malterud and Midtgarden 2009 ). Transdisciplinary researchers must ensure they maintain a high level of objectivity and transparency while actively engaging in the problem context. This point demonstrates the fine balance between different aspects of quality, in this case relevance and credibility, and the need to be aware of tensions and to seek complementarities ( Cash et al. 2002 ).

4.1.3 Legitimacy

Legitimacy refers to whether the research process is perceived as fair and ethical by end-users. In other words, is it acceptable and trustworthy in the eyes of those who will use it? This requires the appropriate inclusion and consideration of diverse values, interests, and the ethical and fair representation of all involved. Legitimacy may be achieved in part through the genuine inclusion of stakeholders in the research process. Whereas credibility refers to technical aspects of sound research, legitimacy deals with sociopolitical aspects of the knowledge production process and products of research. Do stakeholders trust the researchers and the research process, including funding sources and other sources of potential bias? Do they feel represented? Legitimate TDR ‘considers appropriate values, concerns, and perspectives of different actors’ ( Cash et al. 2002 : 2) and incorporates these perspectives into the research process through collaboration and mutual learning ( Bergmann et al. 2005 ; Chataway, Smith and Wield 2007 ; Andrén 2010 ; Huutoneimi 2010 ). A fair and ethical process is important to uphold standards of quality in all research. However, there are additional considerations that are unique to TDR.

Because TDR happens in-context and often in collaboration with societal actors, the disclosure of researcher perspective and a transparent statement of all partnerships, financing, and collaboration is vital to ensure an unbiased research process ( Lincoln 1995 ; Defila and Di Giulio 1999 ; Boaz and Ashby 2003 ; Barker and Pistrang 2005 ; Bergmann et al. 2005 ). The disclosure of perspective has both internal and external aspects, on one hand ensuring the researchers themselves explicitly reflect on and account for their own position, potential sources of bias, and limitations throughout the process, and on the other hand making the process transparent to those external to the research group who can then judge the legitimacy based on their perspective of fairness ( Cash et al. 2002 ).

TDR includes the engagement of societal actors along a continuum of participation from consultation to co-creation of knowledge ( Brandt et al. 2013 ). Regardless of the depth of participation, all processes that engage societal actors must ensure that inclusion/engagement is genuine, roles are explicit, and processes for effective and fair collaboration are present ( Bergmann et al. 2005 ; Wickson, Carew and Russell 2006 ; Spaapen, Dijstelbloem and Wamelink 2007 ; Hellstrom 2012 ). Important considerations include: the accurate representation of those involved; explicit and agreed-upon roles and contributions of actors; and adequate planning and procedures to ensure all values, perspectives, and contexts are adequately and appropriately incorporated. Mitchell and Willets (2009) consider cultural competence as a key criterion that can support researchers in navigating diverse epistemological perspectives. This is similar to what Morrow terms ‘social validity’, a criterion that asks researchers to be responsive to and critically aware of the diversity of perspectives and cultures influenced by their research. Several authors highlight that in order to develop this critical awareness of the diversity of cultural paradigms that operate within a problem situation, researchers should practice responsive, critical, and/or communal reflection ( Bergmann et al. 2005 ; Wickson, Carew and Russell 2006 ; Mitchell and Willets 2009 ; Carew and Wickson 2010 ). Reflection and adaptation are important quality criteria that cut across multiple principles and facilitate learning throughout the process, which is a key foundation to TD inquiry.

4.1.4 Effectiveness

We define effective research as research that contributes to positive change in the social, economic, and/or environmental problem context. Transdisciplinary inquiry is rooted in the objective of solving real-word problems ( Klein 2008 ; Carew and Wickson 2010 ) and must have the potential to ( ex ante ) or actually ( ex post ) make a difference if it is to be considered of high quality ( Erno-Kjolhede and Hansson 2011 ). Potential research effectiveness can be indicated and assessed at the proposal stage and during the research process through: a clear and stated intention to address and contribute to a societal problem, the establishment of the research process and objectives in relation to the problem context, and the continuous reflection on the usefulness of the research findings and products to the problem ( Bergmann et al. 2005 ; Lahtinen et al. 2005 ; de Jong et al. 2011 ).

Assessing research effectiveness ex post remains a major challenge, especially in complex transdisciplinary approaches. Conventional and widely used measures of ‘scientific impact’ count outputs such as journal articles and other publications and citations of those outputs (e.g. H index; i10 index). While these are useful indicators of scholarly influence, they are insufficient and inappropriate measures of research effectiveness where research aims to contribute to social learning and change. We need to also (or alternatively) focus on other kinds of research and scholarship outputs and outcomes and the social, economic, and environmental impacts that may result.

For many authors, contributing to learning and building of societal capacity are central goals of TDR ( Defila and Di Giulio 1999 ; Spaapen, Dijstelbloem and Wamelink 2007 ; Carew and Wickson 2010 ; Erno-Kjolhede and Hansson 2011 ; Hellstrom 2011 ), and so are considered part of TDR effectiveness. Learning can be characterized as changes in knowledge, attitudes, or skills and can be assessed directly, or through observed behavioral changes and network and relationship development. Some evaluation methodologies (e.g. Outcome Mapping ( Earl, Carden and Smutylo 2001 )) specifically measure these kinds of changes. Other evaluation methodologies consider the role of research within complex systems and assess effectiveness in terms of contributions to changes in policy and practice and resulting social, economic, and environmental benefits ( ODI 2004 , 2012 ; White and Phillips 2012 ; Mayne et al. 2013 ).

4.2 TDR quality criteria

TDR quality criteria and their definitions (explicit or implicit) were extracted from each article and summarized in an Excel database. These criteria were classified into themes corresponding to the four principles identified above, sorted and refined to develop sets of criteria that are comprehensive, mutually exclusive, and representative of the ideas presented in the reviewed articles. Within each principle, the criteria are organized roughly in the sequence of a typical project cycle (e.g. with research design following problem identification and preceding implementation). Definitions of each criterion were developed to reflect the concepts found in the literature, tested and refined iteratively to improve clarity. Rubric statements were formulated based on the literature and our own experience.

The complete set of principles, criteria, and definitions is presented as the TDR Quality Assessment Framework ( Table 3 ).

4.3 Guidance on the application of the framework

4.3.1 timing.

Most criteria can be applied at each stage of the research process, ex ante , mid term, and ex post , using appropriate interpretations at each stage. Ex ante (i.e. proposal) assessment should focus on a project’s explicitly stated intentions and approaches to address the criteria. Mid-term indicators will focus on the research process and whether or not it is being implemented in a way that will satisfy the criteria. Ex post assessment should consider whether the research has been done appropriately for the purpose and that the desired results have been achieved.

4.3.2 New meanings for familiar terms

Many of the terms used in the framework are extensions of disciplinary criteria and share the same or similar names and perhaps similar but nuanced meaning. The principles and criteria used here extend beyond disciplinary antecedents and include new concepts and understandings that encapsulate the unique characteristics and needs of TDR and allow for evaluation and definition of quality in TDR. This is especially true in the criteria related to credibility. These criteria are analogous to traditional disciplinary criteria, but with much stronger emphasis on grounding in both the scientific and the social/environmental contexts. We urge readers to pay close attention to the definitions provided in Table 3 as well as the detailed descriptions of the principles in Section 4.1.

4.3.3 Using the framework

The TDR quality framework ( Table 3 ) is designed to be used to assess TDR research according to a project’s purpose; i.e. the criteria must be interpreted with respect to the context and goals of an individual research activity. The framework ( Table 3 ) lists the main criteria synthesized from the literature and our experience, organized within the principles of relevance, credibility, legitimacy, and effectiveness. The table presents the criteria within each principle, ordered to approximate a typical process of identifying a research problem and designing and implementing research. We recognize that the actual process in any given project will be iterative and will not necessarily follow this sequence, but this provides a logical flow. A concise definition is provided in the second column to explain each criterion. We then provide a rubric statement in the third column, phrased to be applied when the research has been completed. In most cases, the same statement can be used at the proposal stage with a simple tense change or other minor grammatical revision, except for the criteria relating to effectiveness. As discussed above, assessing effectiveness in terms of outcomes and/or impact requires evaluation research. At the proposal stage, it is only possible to assess potential effectiveness.

Many rubrics offer a set of statements for each criterion that represent progressively higher levels of achievement; the evaluator is asked to select the best match. In practice, this often results in vague and relative statements of merit that are difficult to apply. We have opted to present a single rubric statement in absolute terms for each criterion. The assessor can then rank how well a project satisfies each criterion using a simple three-point Likert scale. If a project fully satisfies a criterion—that is, if there is evidence that the criterion has been addressed in a way that is coherent, explicit, sufficient, and convincing—it should be ranked as a 2 for that criterion. A score of 2 means that the evaluator is persuaded that the project addressed that criterion in an intentional, appropriate, explicit, and thorough way. A score of 1 would be given when there is some evidence that the criterion was considered, but it is lacking completion, intention, and/or is not addressed satisfactorily. For example, a score of 1 would be given when a criterion is explicitly discussed but poorly addressed, or when there is some indication that the criterion has been considered and partially addressed but it has not been treated explicitly, thoroughly, or adequately. A score of 0 indicates that there is no evidence that the criterion was addressed or that it was addressed in a way that was misguided or inappropriate.

It is critical that the evaluation be done in context, keeping in mind the purpose, objectives, and resources of the project, as well as other contextual information, such as the intended purpose of grant funding or relevant partnerships. Each project will be unique in its complexities; what is sufficient or adequate in one criterion for one research project may be insufficient or inappropriate for another. Words such as ‘appropriate’, ‘suitable’, and ‘adequate’ are used deliberately to encourage application of criteria to suit the needs of individual research projects ( Oberg 2008 ). Evaluators must consider the objectives of the research project and the problem context within which it is carried out as the benchmark for evaluation. For example, we tested the framework with RRU masters theses. These are typically small projects with limited scope, carried out by a single researcher. Expectations for ‘effective communication’ or ‘competencies’ or ‘effective collaboration’ are much different in these kinds of projects than in a multi-year, multi-partner CIFOR project. All criteria should be evaluated through the lens of the stated research objectives, research goals, and context.

The systematic review identified relevant articles from a diverse literature that have a strong central focus. Collectively, they highlight the complexity of contemporary social and environmental problems and emphasize that addressing such issues requires combinations of new knowledge and innovation, action, and engagement. Traditional disciplinary research has often failed to provide solutions because it cannot adequately cope with complexity. New forms of research are proliferating, crossing disciplinary and academic boundaries, integrating methodologies, and engaging a broader range of research participants, as a way to make research more relevant and effective. Theoretically, such approaches appear to offer great potential to contribute to transformative change. However, because these approaches are new and because they are multidimensional, complex, and often unique, it has been difficult to know what works, how, and why. In the absence of the kinds of methodological and quality standards that guide disciplinary research, there are no generally agreed criteria for evaluating such research.

Criteria are needed to guide and to help ensure that TDR is of high quality, to inform the teaching and learning of new researchers, and to encourage and support the further development of transdisciplinary approaches. The lack of a standard and broadly applicable framework for the evaluation of quality in TDR is perceived to cause an implicit or explicit devaluation of high-quality TDR or may prevent quality TDR from being done. There is a demonstrated need for an operationalized understanding of quality that addresses the characteristics, contributions, and challenges of TDR. The reviewed articles approach the topic from different perspectives and fields of study, using different terminology for similar concepts, or the same terminology for different concepts, and with unique ways of organizing and categorizing the dimensions and quality criteria. We have synthesized and organized these concepts as key TDR principles and criteria in a TDR Quality Framework, presented as an evaluation rubric. We have tested the framework on a set of masters’ theses and found it to be broadly applicable, usable, and useful for analyzing individual projects and for comparing projects within the set. We anticipate that further testing with a wider range of projects will help further refine and improve the definitions and rubric statements. We found that the three-point Likert scale (0–2) offered sufficient variability for our purposes, and rating is less subjective than with relative rubric statements. It may be possible to increase the rating precision with more points on the scale to increase the sensitivity for comparison purposes, for example in a review of proposals for a particular grant application.

Many of the articles we reviewed emphasize the importance of the evaluation process itself. The formative, developmental role of evaluation in TDR is seen as essential to the goals of mutual learning as well as to ensure that research remains responsive and adaptive to the problem context. In order to adequately evaluate quality in TDR, the process, including who carries out the evaluations, when, and in what manner, must be revised to be suitable to the unique characteristics and objectives of TDR. We offer this review and synthesis, along with a proposed TDR quality evaluation framework, as a contribution to an important conversation. We hope that it will be useful to researchers and research managers to help guide research design, implementation and reporting, and to the community of research organizations, funders, and society at large. As underscored in the literature review, there is a need for an adapted research evaluation process that will help advance problem-oriented research in complex systems, ultimately to improve research effectiveness.

This work was supported by funding from the Canada Research Chairs program. Funding support from the Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) and technical support from the Evidence Based Forestry Initiative of the Centre for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), funded by UK DfID are also gratefully acknowledged.

Supplementary data is available here

The authors thank Barbara Livoreil and Stephen Dovers for valuable comments and suggestions on the protocol and Gillian Petrokofsky for her review of the protocol and a draft version of the manuscript. Two anonymous reviewers and the editor provided insightful critique and suggestions in two rounds that have helped to substantially improve the article.

Conflict of interest statement . None declared.

1. ‘Stakeholders’ refers to individuals and groups of societal actors who have an interest in the issue or problem that the research seeks to address.

2. The terms ‘quality’ and ‘excellence’ are often used in the literature with similar meaning. Technically, ‘excellence’ is a relative concept, referring to the superiority of a thing compared to other things of its kind. Quality is an attribute or a set of attributes of a thing. We are interested in what these attributes are or should be in high-quality research. Therefore, the term ‘quality’ is used in this discussion.

3. The terms ‘science’ and ‘research’ are not always clearly distinguished in the literature. We take the position that ‘science’ is a more restrictive term that is properly applied to systematic investigations using the scientific method. ‘Research’ is a broader term for systematic investigations using a range of methods, including but not restricted to the scientific method. We use the term ‘research’ in this broad sense.

Aagaard-Hansen J. Svedin U. ( 2009 ) ‘Quality Issues in Cross-disciplinary Research: Towards a Two-pronged Approach to Evaluation’ , Social Epistemology , 23 / 2 : 165 – 76 . DOI: 10.1080/02691720902992323

Google Scholar

Andrén S. ( 2010 ) ‘A Transdisciplinary, Participatory and Action-Oriented Research Approach: Sounds Nice but What do you Mean?’ [unpublished working paper] Human Ecology Division: Lund University, 1–21. < https://lup.lub.lu.se/search/publication/1744256 >

Australian Research Council (ARC) ( 2012 ) ERA 2012 Evaluation Handbook: Excellence in Research for Australia . Australia : ARC . < http://www.arc.gov.au/pdf/era12/ERA%202012%20Evaluation%20Handbook_final%20for%20web_protected.pdf >

Google Preview

Balsiger P. W. ( 2004 ) ‘Supradisciplinary Research Practices: History, Objectives and Rationale’ , Futures , 36 / 4 : 407 – 21 .

Bantilan M. C. et al. . ( 2004 ) ‘Dealing with Diversity in Scientific Outputs: Implications for International Research Evaluation’ , Research Evaluation , 13 / 2 : 87 – 93 .

Barker C. Pistrang N. ( 2005 ) ‘Quality Criteria under Methodological Pluralism: Implications for Conducting and Evaluating Research’ , American Journal of Community Psychology , 35 / 3-4 : 201 – 12 .

Bergmann M. et al. . ( 2005 ) Quality Criteria of Transdisciplinary Research: A Guide for the Formative Evaluation of Research Projects . Central report of Evalunet – Evaluation Network for Transdisciplinary Research. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Institute for Social-Ecological Research. < http://www.isoe.de/ftp/evalunet_guide.pdf >

Boaz A. Ashby D. ( 2003 ) Fit for Purpose? Assessing Research Quality for Evidence Based Policy and Practice .

Boix-Mansilla V. ( 2006a ) ‘Symptoms of Quality: Assessing Expert Interdisciplinary Work at the Frontier: An Empirical Exploration’ , Research Evaluation , 15 / 1 : 17 – 29 .

Boix-Mansilla V. . ( 2006b ) ‘Conference Report: Quality Assessment in Interdisciplinary Research and Education’ , Research Evaluation , 15 / 1 : 69 – 74 .

Bornmann L. ( 2013 ) ‘What is Societal Impact of Research and How can it be Assessed? A Literature Survey’ , Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology , 64 / 2 : 217 – 33 .

Brandt P. et al. . ( 2013 ) ‘A Review of Transdisciplinary Research in Sustainability Science’ , Ecological Economics , 92 : 1 – 15 .

Cash D. Clark W.C. Alcock F. Dickson N. M. Eckley N. Jäger J . ( 2002 ) Salience, Credibility, Legitimacy and Boundaries: Linking Research, Assessment and Decision Making (November 2002). KSG Working Papers Series RWP02-046. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=372280 .

Carew A. L. Wickson F. ( 2010 ) ‘The TD Wheel: A Heuristic to Shape, Support and Evaluate Transdisciplinary Research’ , Futures , 42 / 10 : 1146 – 55 .

Collaboration for Environmental Evidence (CEE) . ( 2013 ) Guidelines for Systematic Review and Evidence Synthesis in Environmental Management . Version 4.2. Environmental Evidence < www.environmentalevidence.org/Documents/Guidelines/Guidelines4.2.pdf >

Chandler J. ( 2014 ) Methods Research and Review Development Framework: Policy, Structure, and Process . < http://methods.cochrane.org/projects-developments/research >

Chataway J. Smith J. Wield D. ( 2007 ) ‘Shaping Scientific Excellence in Agricultural Research’ , International Journal of Biotechnology 9 / 2 : 172 – 87 .

Clark W. C. Dickson N. ( 2003 ) ‘Sustainability Science: The Emerging Research Program’ , PNAS 100 / 14 : 8059 – 61 .

Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) ( 2011 ) A Strategy and Results Framework for the CGIAR . < http://library.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10947/2608/Strategy_and_Results_Framework.pdf?sequence=4 >

Cloete N. ( 1997 ) ‘Quality: Conceptions, Contestations and Comments’, African Regional Consultation Preparatory to the World Conference on Higher Education , Dakar, Senegal, 1-4 April 1997 .

Defila R. DiGiulio A. ( 1999 ) ‘Evaluating Transdisciplinary Research,’ Panorama: Swiss National Science Foundation Newsletter , 1 : 4 – 27 . < www.ikaoe.unibe.ch/forschung/ip/Specialissue.Pano.1.99.pdf >

Donovan C. ( 2008 ) ‘The Australian Research Quality Framework: A Live Experiment in Capturing the Social, Economic, Environmental, and Cultural Returns of Publicly Funded Research. Reforming the Evaluation of Research’ , New Directions for Evaluation , 118 : 47 – 60 .

Earl S. Carden F. Smutylo T. ( 2001 ) Outcome Mapping. Building Learning and Reflection into Development Programs . Ottawa, ON : International Development Research Center .

Ernø-Kjølhede E. Hansson F. ( 2011 ) ‘Measuring Research Performance during a Changing Relationship between Science and Society’ , Research Evaluation , 20 / 2 : 130 – 42 .

Feller I. ( 2006 ) ‘Assessing Quality: Multiple Actors, Multiple Settings, Multiple Criteria: Issues in Assessing Interdisciplinary Research’ , Research Evaluation 15 / 1 : 5 – 15 .

Gaziulusoy A. İ. Boyle C. ( 2013 ) ‘Proposing a Heuristic Reflective Tool for Reviewing Literature in Transdisciplinary Research for Sustainability’ , Journal of Cleaner Production , 48 : 139 – 47 .

Gibbons M. et al. . ( 1994 ) The New Production of Knowledge: The Dynamics of Science and Research in Contemporary Societies . London : Sage Publications .

Hellstrom T. ( 2011 ) ‘Homing in on Excellence: Dimensions of Appraisal in Center of Excellence Program Evaluations’ , Evaluation , 17 / 2 : 117 – 31 .

Hellstrom T. . ( 2012 ) ‘Epistemic Capacity in Research Environments: A Framework for Process Evaluation’ , Prometheus , 30 / 4 : 395 – 409 .

Hemlin S. Rasmussen S. B . ( 2006 ) ‘The Shift in Academic Quality Control’ , Science, Technology & Human Values , 31 / 2 : 173 – 98 .

Hessels L. K. Van Lente H. ( 2008 ) ‘Re-thinking New Knowledge Production: A Literature Review and a Research Agenda’ , Research Policy , 37 / 4 , 740 – 60 .

Huutoniemi K. ( 2010 ) ‘Evaluating Interdisciplinary Research’ , in Frodeman R. Klein J. T. Mitcham C. (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity , pp. 309 – 20 . Oxford : Oxford University Press .

de Jong S. P. L. et al. . ( 2011 ) ‘Evaluation of Research in Context: An Approach and Two Cases’ , Research Evaluation , 20 / 1 : 61 – 72 .

Jahn T. Keil F. ( 2015 ) ‘An Actor-Specific Guideline for Quality Assurance in Transdisciplinary Research’ , Futures , 65 : 195 – 208 .

Kates R. ( 2000 ) ‘Sustainability Science’ , World Academies Conference Transition to Sustainability in the 21st Century 5/18/00 , Tokyo, Japan .

Klein J. T . ( 2006 ) ‘Afterword: The Emergent Literature on Interdisciplinary and Transdisciplinary Research Evaluation’ , Research Evaluation , 15 / 1 : 75 – 80 .

Klein J. T . ( 2008 ) ‘Evaluation of Interdisciplinary and Transdisciplinary Research: A Literature Review’ , American Journal of Preventive Medicine , 35 / 2 Supplment S116–23. DOI: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.010

Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, Association of Universities in the Netherlands, Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (KNAW) . ( 2009 ) Standard Evaluation Protocol 2009-2015: Protocol for Research Assessment in the Netherlands . Netherlands : KNAW . < www.knaw.nl/sep >

Komiyama H. Takeuchi K. ( 2006 ) ‘Sustainability Science: Building a New Discipline’ , Sustainability Science , 1 : 1 – 6 .

Lahtinen E. et al. . ( 2005 ) ‘The Development of Quality Criteria For Research: A Finnish approach’ , Health Promotion International , 20 / 3 : 306 – 15 .

Lang D. J. et al. . ( 2012 ) ‘Transdisciplinary Research in Sustainability Science: Practice , Principles , and Challenges’, Sustainability Science , 7 / S1 : 25 – 43 .

Lincoln Y. S . ( 1995 ) ‘Emerging Criteria for Quality in Qualitative and Interpretive Research’ , Qualitative Inquiry , 1 / 3 : 275 – 89 .

Mayne J. Stern E. ( 2013 ) Impact Evaluation of Natural Resource Management Research Programs: A Broader View . Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research, Canberra .

Meyrick J . ( 2006 ) ‘What is Good Qualitative Research? A First Step Towards a Comprehensive Approach to Judging Rigour/Quality’ , Journal of Health Psychology , 11 / 5 : 799 – 808 .

Mitchell C. A. Willetts J. R. ( 2009 ) ‘Quality Criteria for Inter and Trans - Disciplinary Doctoral Research Outcomes’ , in Prepared for ALTC Fellowship: Zen and the Art of Transdisciplinary Postgraduate Studies ., Sydney : Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology .

Morrow S. L . ( 2005 ) ‘Quality and Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research in Counseling Psychology’ , Journal of Counseling Psychology , 52 / 2 : 250 – 60 .

Nowotny H. Scott P. Gibbons M. ( 2001 ) Re-Thinking Science . Cambridge : Polity .

Nowotny H. Scott P. Gibbons M. . ( 2003 ) ‘‘Mode 2’ Revisited: The New Production of Knowledge’ , Minerva , 41 : 179 – 94 .

Öberg G . ( 2008 ) ‘Facilitating Interdisciplinary Work: Using Quality Assessment to Create Common Ground’ , Higher Education , 57 / 4 : 405 – 15 .

Ozga J . ( 2007 ) ‘Co - production of Quality in the Applied Education Research Scheme’ , Research Papers in Education , 22 / 2 : 169 – 81 .

Ozga J . ( 2008 ) ‘Governing Knowledge: research steering and research quality’ , European Educational Research Journal , 7 / 3 : 261 – 272 .

OECD ( 2012 ) Frascati Manual 6th ed. < http://www.oecd.org/innovation/inno/frascatimanualproposedstandardpracticeforsurveysonresearchandexperimentaldevelopment6thedition >

Overseas Development Institute (ODI) ( 2004 ) ‘Bridging Research and Policy in International Development: An Analytical and Practical Framework’, ODI Briefing Paper. < http://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/198.pdf >

Overseas Development Institute (ODI) . ( 2012 ) RAPID Outcome Assessment Guide . < http://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/7815.pdf >

Pullin A. S. Stewart G. B. ( 2006 ) ‘Guidelines for Systematic Review in Conservation and Environmental Management’ , Conservation Biology , 20 / 6 : 1647 – 56 .

Research Excellence Framework (REF) . ( 2011 ) Research Excellence Framework 2014: Assessment Framework and Guidance on Submissions. Reference REF 02.2011. UK: REF. < http://www.ref.ac.uk/pubs/2011-02/ >

Scott A . ( 2007 ) ‘Peer Review and the Relevance of Science’ , Futures , 39 / 7 : 827 – 45 .

Spaapen J. Dijstelbloem H. Wamelink F. ( 2007 ) Evaluating Research in Context: A Method for Comprehensive Assessment . Netherlands: Consultative Committee of Sector Councils for Research and Development. < http://www.qs.univie.ac.at/fileadmin/user_upload/qualitaetssicherung/PDF/Weitere_Aktivit%C3%A4ten/Eric.pdf >

Spaapen J. Van Drooge L. ( 2011 ) ‘Introducing “Productive Interactions” in Social Impact Assessment’ , Research Evaluation , 20 : 211 – 18 .

Stige B. Malterud K. Midtgarden T. ( 2009 ) ‘Toward an Agenda for Evaluation of Qualitative Research’ , Qualitative Health Research , 19 / 10 : 1504 – 16 .

td-net ( 2014 ) td-net. < www.transdisciplinarity.ch/e/Bibliography/new.php >

Tertiary Education Commission (TEC) . ( 2012 ) Performance-based Research Fund: Quality Evaluation Guidelines 2012. New Zealand: TEC. < http://www.tec.govt.nz/Documents/Publications/PBRF-Quality-Evaluation-Guidelines-2012.pdf >

Tijssen R. J. W. ( 2003 ) ‘Quality Assurance: Scoreboards of Research Excellence’ , Research Evaluation , 12 : 91 – 103 .

White H. Phillips D. ( 2012 ) ‘Addressing Attribution of Cause and Effect in Small n Impact Evaluations: Towards an Integrated Framework’. Working Paper 15. New Delhi: International Initiative for Impact Evaluation .

Wickson F. Carew A. ( 2014 ) ‘Quality Criteria and Indicators for Responsible Research and Innovation: Learning from Transdisciplinarity’ , Journal of Responsible Innovation , 1 / 3 : 254 – 73 .

Wickson F. Carew A. Russell A. W. ( 2006 ) ‘Transdisciplinary Research: Characteristics, Quandaries and Quality,’ Futures , 38 / 9 : 1046 – 59

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1471-5449

- Print ISSN 0958-2029

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

A Step-To-Step Guide to Write a Quality Research Article

- Conference paper

- First Online: 01 June 2023

- Cite this conference paper

- Amit Kumar Tyagi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2657-8700 14 ,

- Rohit Bansal 15 ,

- Anshu 16 &

- Sathian Dananjayan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6103-7267 17

Part of the book series: Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems ((LNNS,volume 717))

Included in the following conference series:

- International Conference on Intelligent Systems Design and Applications

275 Accesses

21 Citations

Today publishing articles is a trend around the world almost in each university. Millions of research articles are published in thousands of journals annually throughout many streams/sectors such as medical, engineering, science, etc. But few researchers follow the proper and fundamental criteria to write a quality research article. Many published articles over the web become just irrelevant information with duplicate information, which is a waste of available resources. This is because many authors/researchers do not know/do not follow the correct approach for writing a valid/influential paper. So, keeping such issues for new researchers or exiting researchers in many sectors, we feel motivated to write an article and present some systematic work/approach that can help researchers produce a quality research article. Also, the authors can publish their work in international conferences like CVPR, ICML, NeurIPS, etc., or international journals with high factors or a white paper. Publishing good articles improve the profile of researchers around the world, and further future researchers can refer their work in their work as references to proceed with the respective research to a certain level. Hence, this article will provide sufficient information for researchers to write a simple, effective/impressive and qualitative research article on their area of interest.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Nair, M.M., Tyagi, A.K., Sreenath, N.: The future with industry 4.0 at the core of society 5.0: open issues, future opportunities and challenges. In: 2021 International Conference on Computer Communication and Informatics (ICCCI), pp. 1–7 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCCI50826.2021.9402498

Tyagi, A.K., Fernandez, T.F., Mishra, S., Kumari, S.: Intelligent Automation Systems at the Core of Industry 4.0. In: Abraham, A., Piuri, V., Gandhi, N., Siarry, P., Kaklauskas, A., Madureira, A. (eds.) ISDA 2020. AISC, vol. 1351, pp. 1–18. Springer, Cham (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-71187-0_1

Chapter Google Scholar

Goyal, D., Tyagi, A.: A Look at Top 35 Problems in the Computer Science Field for the Next Decade. CRC Press, Boca Raton (2020) https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003052098-40

Tyagi, A.K., Meenu, G., Aswathy, S.U., Chetanya, V.: Healthcare Solutions for Smart Era: An Useful Explanation from User’s Perspective. In the Book “Recent Trends in Blockchain for Information Systems Security and Privacy”. CRC Press, Boca Raton (2021)

Google Scholar

Varsha, R., Nair, S.M., Tyagi, A.K., Aswathy, S.U., RadhaKrishnan, R.: The future with advanced analytics: a sequential analysis of the disruptive technology’s scope. In: Abraham, A., Hanne, T., Castillo, O., Gandhi, N., Nogueira Rios, T., Hong, T.-P. (eds.) HIS 2020. AISC, vol. 1375, pp. 565–579. Springer, Cham (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-73050-5_56

Tyagi, A.K., Nair, M.M., Niladhuri, S., Abraham, A.: Security, privacy research issues in various computing platforms: a survey and the road ahead. J. Inf. Assur. Secur. 15 (1), 1–16 (2020)

Madhav, A.V.S., Tyagi, A.K.: The world with future technologies (Post-COVID-19): open issues, challenges, and the road ahead. In: Tyagi, A.K., Abraham, A., Kaklauskas, A. (eds.) Intelligent Interactive Multimedia Systems for e-Healthcare Applications, pp. 411–452. Springer, Singapore (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-6542-4_22

Mishra, S., Tyagi, A.K.: The role of machine learning techniques in the Internet of Things-based cloud applications. In: Pal, S., De, D., Buyya, R. (eds.) Artificial Intelligence-Based Internet of Things Systems. Internet of Things (Technology, Communications and Computing). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-87059-1_4

Pramod, A., Naicker, H.S., Tyagi, A.K.: Machine Learning and Deep Learning: Open Issues and Future Research Directions for Next Ten Years. Computational Analysis and Understanding of Deep Learning for Medical Care: Principles, Methods, and Applications. Wiley Scrivener (2020)

Kumari, S., Tyagi, A.K., Aswathy, S.U.: The Future of Edge Computing with Blockchain Technology: Possibility of Threats, Opportunities and Challenges. In the Book Recent Trends in Blockchain for Information Systems Security and Privacy. CRC Press, Boca Raton (2021)