- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Communication and Culture

- Communication and Social Change

- Communication and Technology

- Communication Theory

- Critical/Cultural Studies

- Gender (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Studies)

- Health and Risk Communication

- Intergroup Communication

- International/Global Communication

- Interpersonal Communication

- Journalism Studies

- Language and Social Interaction

- Mass Communication

- Media and Communication Policy

- Organizational Communication

- Political Communication

- Rhetorical Theory

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Intercultural competence.

- Lily A. Arasaratnam Lily A. Arasaratnam Director of Research, Department of Communication, Alphacrucis College

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.68

- Published online: 03 February 2016

The phrase “intercultural competence” typically describes one’s effective and appropriate engagement with cultural differences. Intercultural competence has been studied as residing within a person (i.e., encompassing cognitive, affective, and behavioral capabilities of a person) and as a product of a context (i.e., co-created by the people and contextual factors involved in a particular situation). Definitions of intercultural competence are as varied. There is, however, sufficient consensus amongst these variations to conclude that there is at least some collective understanding of what intercultural competence is. In “Conceptualizing Intercultural Competence,” Spitzberg and Chagnon define intercultural competence as, “the appropriate and effective management of interaction between people who, to some degree or another, represent different or divergent affective, cognitive, and behavioral orientations to the world” (p. 7). In the discipline of communication, intercultural communication competence (ICC) has been a subject of study for more than five decades. Over this time, many have identified a number of variables that contribute to ICC, theoretical models of ICC, and quantitative instruments to measure ICC. While research in the discipline of communication has made a significant contribution to our understanding of ICC, a well-rounded discussion of intercultural competence cannot ignore the contribution of other disciplines to this subject. Our present understanding of intercultural competence comes from a number of disciplines, such as communication, cross-cultural psychology, social psychology, linguistics, anthropology, and education, to name a few.

- intercultural competence

- intercultural communication

- appropriate

A Brief Introduction

With increasing global diversity, intercultural competence is a topic of immediate relevance. While some would question the use of the term “competence” as a Western concept, the ability to understand and interact with people of different cultures in authentic and positive ways is a topic worth discussing. Though several parts of the world do remain culturally homogenous, many major cities across the world have undergone significant transformation in their cultural and demographic landscape due to immigration. Advances in communication technologies have also facilitated intercultural communication without the prerequisite of geographic proximity. Hence educational, business, and other projects involving culturally diverse workgroups have become increasingly common. In such contexts the success of a group in accomplishing its goals might not depend only on the group members’ expertise in a particular topic or ability to work in a virtual environment but also on their intercultural competence (Zakaria, Amelinckx, & Wilemon, 2004 ). Cultural diversity in populations continues to keep intercultural competence (or cultural competence, as it is known in some disciplines) on the agenda of research in applied disciplines such as medicine (Bow, Woodward, Flynn, & Stevens, 2013 ; Charles, Hendrika, Abrams, Shea, Brand, & Nicol, 2014 ) and education (Blight, 2012 ; Tangen, Mercer, Spooner-Lane, & Hepple, 2011 ), for example.

As noted in the historiography section, early research in intercultural competence can be traced back to acculturation/adaptation studies. Labels such as cross-cultural adaptation and cross-cultural adjustment/effectiveness were used to describe what we now call intercultural competence, though adaptation and adjustment continue to remain unique concepts in the study of migrants. It is fair to say that today’s researchers would agree that, while intercultural competence is an important part of adapting to a new culture, it is conceptually distinct.

Although our current understanding of intercultural competence is (and continues to be) shaped by research in many disciplines, communication researchers can lay claim to the nomenclature of the phrase, particularly intercultural communication competence (ICC). Intercultural competence is defined by Spitzberg and Chagnon ( 2009 ) as “the appropriate and effective management of interaction between people who, to some degree or another, represent different or divergent affective, cognitive, and behavioral orientations to the world” (p. 7), which touches on a long history of intercultural competence being associated with effectiveness and appropriateness. This is echoed in several models of intercultural competence as well. The prevalent characterization of effectiveness as the successful achievement of one’s goals in a particular communication exchange is notably individualistic in its orientation. Appropriateness, however, views the communication exchange from the other person’s point of view, as to whether the communicator has communicated in a manner that is (contextually) expected and accepted.

Generally speaking, research findings support the view that intercultural competence is a combination of one’s personal abilities (such as flexibility, empathy, open-mindedness, self-awareness, adaptability, language skills, cultural knowledge, etc.) as well as relevant contextual variables (such as shared goals, incentives, perceptions of equality, perceptions of agency, etc.). In an early discussion of interpersonal competence, Argyris ( 1965 ) proposed that competence increases as “one’s awareness of relevant factors increases,” when one can solve problems with permanence, in a manner that has “minimal deterioration of the problem-solving process” (p. 59). This view of competence places it entirely on the abilities of the individual. Kim’s ( 2009 ) definition of intercultural competence as “an individual’s overall capacity to engage in behaviors and activities that foster cooperative relationships in all types of social and cultural contexts in which culturally or ethnically dissimilar others interface” (p. 62) further highlights the emphasis on the individual. Others, however, suggest that intercultural competence has an element of social judgment, to be assessed by others with whom one is interacting (Koester, Wiseman, & Sanders, 1993 ). A combination of self and other assessment is logical, given that the definition of intercultural competence encompasses effective (from self’s perspective) and appropriate (from other’s perspective) communication.

Before delving further into intercultural competence, some limitations to our current understanding of intercultural competence must be acknowledged. First, our present understanding of intercultural competence is strongly influenced by research emerging from economically developed parts of the world, such as the United States and parts of Europe and Oceania. Interpretivists would suggest that the (cultural) perspectives from which the topic is approached inevitably influence the outcomes of research. Second, there is a strong social scientific bias to the cumulative body of research in intercultural competence so far; as such, the findings are subject to the strengths and weaknesses of this epistemology. Third, because many of the current models of intercultural competence (or intercultural communication competence) focus on the individual, and because individual cultural identities are arguably becoming more blended in multicultural societies, we may be quickly approaching a point where traditional definitions of intercultural communication (and by association, intercultural competence) need to be refined. While this is not an exhaustive list of limitations, it identifies some of the parameters within which current conceptualizations of intercultural competence must be viewed.

The following sections discuss intercultural competence, as we know it, starting with what it is and what it is not . A brief discussion of well-known theories of ICC follows, then some of the variables associated with ICC are identified. One of the topics of repeated query is whether ICC is culture-general or culture-specific. This is addressed in the section following the discussion of variables associated with ICC, followed by a section on assessment of ICC. Finally, before delving into research directions for the future and a historiography of research in ICC over the years, the question of whether ICC can be learned is addressed.

Clarification of Nomenclature

As noted in the summary section, one of the most helpful definitions of intercultural competence is provided by Spitzberg and Chagnon ( 2009 ), who define it as “the appropriate and effective management of interaction between people who, to some degree or another, represent different or divergent affective, cognitive, and behavioral orientations to the world” (p. 7). However, addressing what intercultural competence is not is just as important as explaining what it is, in a discussion such as this. Conceptually, intercultural competence is not equivalent to acculturation, multiculturalism, biculturalism, or global citizenship—although intercultural competence is a significant aspect of them all. Semantically, intercultural efficiency, cultural competence, intercultural sensitivity, intercultural communication competence, cross-cultural competence, and global competence are some of the labels with which students of intercultural competence might be familiar.

The multiplicity in nomenclature of intercultural competence has been one of the factors that have irked researchers who seek conceptual clarity. In a meta-analysis of studies in intercultural communication competence, Bradford, Allen, and Beisser ( 2000 ) attempted to synthesize the multiple labels used in research; they concluded that intercultural effectiveness is conceptually equivalent to intercultural communication competence. Others have proposed that intercultural sensitivity is conceptually distinct from intercultural competence (Chen & Starosta, 2000 ). Others have demonstrated that, while there are multiple labels in use, there is general consensus as to what intercultural competence is (Deardorff, 2006 ).

In communication literature, it is fair to note that intercultural competence and intercultural communication competence are used interchangeably. In literature in other disciplines, such as medicine and health sciences, cultural competence is the label with which intercultural competence is described. Some have also proposed the phrase cultural humility as a deliberate alternative to cultural competence, suggesting that cultural humility involves life-long learning through self-awareness and critical reflection (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998 ).

The nature of an abstract concept is such that its reality is defined by the labels assigned to it. Unlike some concepts that have been defined and developed over many years within the parameters of a single discipline, intercultural competence is of great interest to researchers in multiple disciplines. As such, researchers from different disciplines have ventured to study it, without necessarily building on findings from other disciplines. This is one factor that has contributed to the multiple labels by which intercultural competence is known. This issue might not be resolved in the near future. However, those seeking conceptual clarity could look for the operationalization of what is being studied, rather than going by the name by which it is called. In other words, if what is being studied is effectiveness and appropriateness in intercultural communication (each of these terms in turn need to be unpacked to check for conceptual equivalency), then one can conclude that it is a study of intercultural competence, regardless of what it is called.

Theories of Intercultural Competence

Many theories of intercultural (communication) competence have been proposed over the years. While it is fair to say that there is no single leading theory of intercultural competence, some of the well-known theories are worth noting.

There are a couple of theories of ICC that are identified as covering laws theories (Wiseman, 2002 ), namely Anxiety Uncertainty Management (AUM) theory and Face Negotiation theory. Finding its origins in Berger and Calabrese ( 1975 ), AUM theory (Gudykunst, 1993 , 2005 ) proposes that the ability to be mindful and the effective management of anxiety caused by the uncertainty in intercultural interactions are key factors in achieving ICC. Gudykunst conceptualizes ICC as intercultural communication that has the least amount of misunderstandings. While AUM theory is not without its critics (for example, Yoshitake, 2002 ), it has been used in a number of empirical studies over the years (examples include Duronto, Nishida, & Nakayama, 2005 ; Ni & Wang, 2011 ), including studies that have extended the theory further (see Neuliep, 2012 ).

Though primarily focused on intercultural conflict rather than intercultural competence, Face Negotiation theory (Ting-Toomey, 1988 ) proposes that all people try to maintain a favorable social self-image and engage in a number of communicative behaviours designed to achieve this goal. Competence is identified as being part of the concept of “face,” and it is achieved through the integration of knowledge, mindfulness, and skills in communication (relevant to managing one’s own face as well as that of others). Face Negotiation theory has been used predominantly in intercultural conflict studies (see Oetzel, Meares, Myers, & Lara, 2003 ). As previously noted, it is not primarily a theory of intercultural competence, but it does address competence in intercultural settings.

From a systems point of view, Spitzberg’s ( 2000 ) model of ICC and Kim’s ( 1995 ) cultural adaptation theory are also well-known. Spitzberg identifies three levels of analysis that must be considered in ICC, namely the individual system, the episodic system, and the relational system. The factors that contribute to competence are delineated in terms of characteristics that belong to an individual (individual system), features that are particular to a specific interaction (episodic system), and variables that contribute to one’s competence across interactions with multiple others (relational system). Kim’s cultural adaptation theory recognizes ICC as an internal capacity within an individual; it proposes that each individual (being an open system) has the goal of adapting to one’s environment and identifies cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions of ICC.

Wiseman’s ( 2002 ) chapter on intercultural communication competence, in the Handbook of International and Intercultural Communication provides further descriptions of theories in ICC. While there have been several models of ICC developed since then, well-formed and widely tested theories of ICC remain few.

Variables Associated with Intercultural Competence

A number of variables have been identified as contributors to intercultural competence. Among these are mindfulness (Gudykunst, 1993 ), self and other awareness (Deardorff, 2006 ), listening skills (Ting-Toomey & Kurogi, 1998 ), positive attitude toward other cultures, and empathy (Arasaratnam & Doerfel, 2005 ), to name a few. Further, flexibility, tolerance for ambiguity, capacity for complexity, and language proficiency are also relevant. There is evidence to suggest that personal spiritual wellbeing plays a positive role in intercultural competence (Sandage & Jankowski, 2013 ). Additionally, there is an interesting link between intercultural competence and a biological variable, namely sensation seeking. Evidence suggests that, in the presence of a positive attitude towards other cultures and motivation to interact with people from other cultures, there is a positive relationship between sensation seeking and intercultural competence (Arasaratnam & Banerjee, 2011 ). Sensation seeking has also been associated with intercultural friendships (Morgan & Arasaratnam, 2003 ; Smith & Downs, 2004 ).

Cognitive complexity has also been identified with intercultural competence (Gudykunst & Kim, 2003 ). Cognitive complexity refers to an individual’s ability to form multiple nuanced perceptual categories (Bieri, 1955 ). A cognitively complex person relies less on stereotypical generalizations and is more perceptive to subtle racism (Reid & Foels, 2010 ). Gudykunst ( 1995 ) proposed that cognitive complexity is directly related to effective management of uncertainty and anxiety in intercultural communication, which in turn leads to ICC (according to AUM theory).

Not all variables are positively associated with intercultural competence. One of the variables that notably hinder intercultural competence is ethnocentrism. Neuliep ( 2002 ) characterizes ethnocentrism as, “an individual psychological disposition where the values, attitudes, and behaviors of one’s ingroup are used as the standard for judging and evaluating another group’s values, attitudes, and behaviors” (p. 201). Arasaratnam and Banerjee ( 2011 ) found that introducing ethnocentrism into a model of ICC weakened all positive relationships between the variables that otherwise contribute to ICC. Neuliep ( 2012 ) further discovered that ethnocentrism and intercultural communication apprehension debilitate intercultural communication. As Neuliep observed, ethnocentrism hinders mindfulness because a mindful communicator is receptive to new information, while the worldview of an ethnocentric person is rigidly centered on his or her own culture.

This is, by no means, an exhaustive list of variables that influence intercultural competence, but it is representative of the many individual-centered variables that influence the extent to which one is effective and appropriate in intercultural communication. Contextual variables, as noted in the next section, also play a role in ICC. It must further be noted that many of the ICC models do not identify language proficiency as a key variable; however, the importance of language proficiency has not been ignored (Fantini, 2009 ). Various models of intercultural competence portray the way in which (and, in some cases, the extent to which) these variables contribute to intercultural competence. For an expansive discussion of models of intercultural competence, see Spitzberg and Chagnoun ( 2009 ).

If one were to broadly summarize what we know thus far about an interculturally competent person, one could say that she or he is mindful, empathetic, motivated to interact with people of other cultures, open to new schemata, adaptable, flexible, able to cope with complexity and ambiguity. Language skills and culture-specific knowledge undoubtedly serve as assets to such an individual. Further, she or he is neither ethnocentric nor defined by cultural prejudices. This description does not, however, take into account the contextual variables that influence intercultural competence; highlighting the fact that the majority of intercultural competence research has been focused on the individual.

The identification of variables associated with intercultural competence raises a number of further questions. For example, is intercultural competence culture-general or culture-specific; can it be measured; and can it be taught or learned? These questions merit further exploration.

Culture General or Culture Specific

A person who is an effective and appropriate intercultural communicator in one context might not be so in another cultural context. The pertinent question is whether there are variables that facilitate intercultural competence across multiple cultural contexts. There is evidence to suggest that there are indeed culture-general variables that contribute to intercultural competence. This means there are variables that, regardless of cultural perspective, contribute to perception of intercultural competence. Arasaratnam and Doerfel ( 2005 ), for example, identified five such variables, namely empathy, experience, motivation, positive attitude toward other cultures, and listening. The rationale behind their approach is to look for commonalities in emic descriptions of intercultural competence by participants who represent a variety of cultural perspectives. Some of the variables identified by Arasaratnam and Doerfel’s research are replicated in others’ findings. For example, empathy has been found to be a contributor to intercultural competence in a number of other studies (Gibson & Zhong, 2005 ; Nesdale, De Vries Robbé, & Van Oudenhoven, 2012 ). This does not mean, however, that context has no role to play in perception of ICC. Contextual variables, such as the relationship between the interactants, the values of the cultural context in which the interaction unfolds, the emotional state of the interactants, and a number of other such variables no doubt influence effectiveness and appropriateness. Perception of competence in a particular situation is arguably a combination of culture-general and contextual variables. However, the aforementioned “culture-general” variables have been consistently associated with perceived ICC by people of different cultures. Hence they are noteworthy. The culture-general nature of some of the variables that contribute to intercultural competence provides an optimistic perspective that, even in the absence of culture-specific knowledge, it is possible for one to engage in effective and appropriate intercultural communication. Witteborn ( 2003 ) observed that the majority of models of intercultural competence take a culture-general approach. What is lacking at present, however, is extensive testing of these models to verify their culture-general nature.

The extent to which the culture-general nature of intercultural competence can be empirically verified depends on our ability to assess the variables identified in these models, and assessing intercultural competence itself. To this end, a discussion of assessment is warranted.

Assessing Intercultural Competence

Researchers have employed both quantitative and qualitative techniques in the assessment of intercultural competence. Deardorff ( 2006 ) proposed that intercultural competence should be measured progressively (at different points in time, over a period of time) and using multiple methods.

In terms of quantitative assessment, the nature of intercultural competence is such that any measure of this concept has to be one that (conceptually) translates across different cultures. Van de Vijver and Leung ( 1997 ) identified three biases that must be considered when using a quantitative instrument across cultures. First, there is potential for construct biases where cultural interpretations of a particular construct might vary. For example, “personal success” might be defined in terms of affluence, job prestige, etc., in an individualistic culture that favors capitalism, while the same construct could be defined in terms of sense of personal contribution and family validation in a collectivistic culture (Arasaratnam, 2007 ). Second, a method bias could be introduced by the very choice of the use of a quantitative instrument in a culture that might not be familiar with quantifying abstract concepts. Third, the presence of an item that is irrelevant to a particular cultural group could introduce an item bias when that instrument is used in research involving participants from multiple cultural groups. For a more detailed account of equivalence and biases that must be considered in intercultural research, see Van de Vijver and Leung ( 2011 ).

Over the years, many attempts have been made to develop quantitative measures of intercultural competence. There are a number of instruments that have been designed to measure intercultural competence or closely related concepts. A few of the more frequently used ones are worth noting.

Based on the Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (DMIS) (Bennett, 1986 ), the Intercultural Development Inventory (IDI) measures three ethnocentric and three ethno-relative levels of orientation toward cultural differences, as identified in the DMIS model (Hammer, Bennett, & Wiseman, 2003 ). This instrument is widely used in intercultural research, in several disciplines. Some examples of empirical studies that use IDI include Greenholtz ( 2000 ), Sample ( 2013 ), and Wang ( 2013 ).

The Intercultural Sensitivity Inventory (ICSI) is another known instrument that approaches intercultural competence from the perspective of a person’s ability to appropriately modify his or her behavior when confronted with cultural differences, specifically as they pertain to individualistic and collectivistic cultures (Bhawuk & Brislin, 1992 ). It must be noted, however, that intercultural sensitivity is not necessarily equivalent to intercultural competence. Chen and Starosta ( 2000 ), for example, argued that intercultural sensitivity is a pre-requisite for intercultural competence rather than its conceptual equivalent. As such, Chen and Starosta’s Intercultural Sensitivity scale should be viewed within the same parameters. The authors view intercultural sensitivity as the affective dimension of intercultural competence (Chen & Starosta, 1997 ).

Although not specifically designed to measure intercultural competence, the Multicultural Personality Questionnaire (MPQ) measures five dimensions, namely open mindedness, emotional stability, cultural empathy, social initiative, and flexibility (Van Oudenhoven & Van der Zee, 2002 ), all of which have been found to be directly related to intercultural competence, in other research (see Matsumoto & Hwang, 2013 ).

Quantitative measures of intercultural competence almost exclusively rely on self-ratings. As such, they bear the strengths and weaknesses of any self-report (for a detailed discussion of self-knowledge, see Bauer & Baumeister, 2013 ). There is some question as to whether Likert-type scales favor individuals with higher cognitive complexity because such persons have a greater capacity for differentiating between constructs (Bowler, Bowler, & Cope, 2012 ). Researchers have also used other methods such as portfolios, reflective journals, responses to hypothetical scenarios, and interviews. There continues to be a need for fine-tuned methods of assessing intercultural competence that utilize others’ perceptions in addition to self-reports.

Can Intercultural Competence Be Learned?

If competence is the holy grail of intercultural communication, then the question is whether it can be learned. On the one hand, many researchers suggest that the process of learning intercultural competence is developmental (Beamer, 1992 ; Bennett, 1986 ; Hammer, Bennett, & Wiseman, 2003 ). Which means that over time, experiences, and deliberate reflection, people can learn things that cumulatively contribute to intercultural competence. Evidence also suggests that collaborative learning facilitates the development of intercultural competence (Helm, 2009 ; Zhang, 2012 ). On the other hand, given research shows that there are many personality variables that contribute to intercultural competence; one could question whether these are innate or learned. Further, many causal models of intercultural competence show that intercultural competence is the product of interactions between many variables. If some of these can be learned and others are innate, then it stands to reason that, given equal learning opportunities, there would still be variations in the extent to which one “achieves” competence. There is also evidence to suggest that there are certain variables, such as ethnocentrism, that debilitate intercultural competence. Thus, it is fair to conclude that, while there is the potential for one to improve one’s intercultural competence through learning, not all can or will.

The aforementioned observation has implications for intercultural training, particularly training that relies heavily on dissemination of knowledge alone. In other words, just because someone knows facts about intercultural competence, it does not necessarily make them an expert at effective and appropriate communication. Developmental models of intercultural competence suggest that the learning process is progressive over time, based on one’s reaction to various experiences and one’s ability to reflect on new knowledge (Saunders, Haskins, & Vasquez et al., 2015 ). Further, research shows that negative attitudes and attitudes that are socially reinforced are the hardest to change (Bodenhausen & Gawronski, 2013 ). Hence people with negative prejudices toward other cultures, for example, may not necessarily be affected by an intercultural training workshop. While many organizations have implemented intercultural competency training in employee education as a nod to embracing diversity, the effectiveness of short, skilled-based training bears further scrutiny. For more on intercultural training, see the Handbook of Intercultural Training by Landis, Bennett, and Bennett ( 2004 ).

Research Directions

In a review of ICC research between 2003 and 2013 , Arasaratnam ( 2014 ) observed that there is little cross-disciplinary dialogue when it comes to intercultural competence research. Even though intercultural competence is a topic of interest to researchers in multiple disciplines, the findings from within a discipline appear to have limited external disciplinary reach. This is something that needs to be addressed. While the field of communication has played a significant role in contributing to current knowledge of intercultural competence, findings from other disciplines not only add to this knowledge but also potentially address gaps in research that are inevitable from a single disciplinary point of view. As previously observed, one of the reasons for lack of cross-disciplinary referencing (apart from lack of familiarity with work outside of one’s own discipline) could be the use of different labels to describe intercultural competence. Hence, students and scholars would do well to include these variations in labels when looking for research in intercultural competence. This would facilitate consolidation of inter-disciplinary knowledge in future research.

New and robust theories of intercultural competence that are empirically tested in multiple cultural groups are needed. As previously observed, the majority of existing theories in intercultural communication competence stem from the United States, and as such are influenced by a particular worldview. Theories from other parts of the world would enrich our current understanding of intercultural competence.

Thus far, the majority of research in intercultural communication has been done with the fundamental assumption that participants in a dyadic intercultural interaction arrive at it from two distinct cultural perspectives. This assumption might not be valid in all interactions that could still be classified as intercultural. With increasing global mobility, there are more opportunities for people to internalize more than one culture, thus becoming bicultural or blended in their cultural identity. This adds a measure of complexity to the study of intercultural competence because there is evidence to show that there are cultural differences in a range of socio-cognitive functions such as categorization, attribution, and reasoning (Miyamoto & Wilken, 2013 ), and these functions play important roles in how we perceive others, which in turn influences effective and appropriate communication (Moskowitz & Gill, 2013 ).

The concept of competence itself merits further reflection. Because the majority of voices that contribute to ongoing discussions on intercultural competence arise from developed parts of the world, it is fair to say that these discussions are not comprehensively representative of multiple cultural views. Further, the main mechanisms of academic publishing favor a peer-review system which can be self-perpetuating because the reviewers themselves are often the vocal contributors to the existing body of knowledge. For a more well rounded reflection of what it means to engage in authentic and affirming intercultural communication, sources of knowledge other than academic publications need to be considered. These may include the work done by international aid agencies and not-for-profit organizations for example, which engage with expressions of intercultural communication that are different from those that are observed among international students, expatriates, or medical, teaching, or business professionals, who inform a significant amount of intercultural competence research in academia.

Historiography: Research in Intercultural Competence over the Years

The concept of “competence” is not recent. For example, in an early use of the term, psychologist Robert W. White ( 1959 ) characterized competence as “an organism’s capacity to interact effectively with its environment” (p. 297) and proposed that effectance motivation (which results in feelings of efficacy) is an integral part of competence. Today’s research in intercultural competence has been informed by the work of researchers in a number of disciplines, over several decades.

In the field of communication, some of the pioneers of ICC research are Mary Jane Collier ( 1986 ), Norman G. Dinges ( 1983 ), William B. Gudykunst ( 1988 ), Mitchell R. Hammer ( 1987 ), T. Todd Imohari (Imohari & Lanigan, 1989 ), Daniel J. Kealey ( 1989 ), Young Yun Kim ( 1991 ), Jolene Koester (Koester & Olebe, 1988 ), Judith N. Martin ( 1987 ), Hiroko Nishida ( 1985 ), Brent D. Ruben ( 1976 ), Brian H. Spitzberg ( 1983 ), Stella Ting-Toomey ( 1988 ), and Richard L. Wiseman (Wiseman & Abe, 1986 ).

While much of the momentum in communication research started in the late 1970s, a conservative (and by no means comprehensive) glance at history traces back some of the early works in intercultural competence to the 1960s, where researchers identified essential characteristics for intercultural communication. This research was based on service personnel and Americans travelling overseas for work (Gardner, 1962 ; Guthrie & Zetrick, 1967 ; Smith, 1966 ). The characteristics they identified include flexibility, stability, curiosity, openness to other perspectives, and sensitivity, to name a few, and these characteristics were studied in the context of adaptation to a new culture.

In the 1970s, researchers built on early work to further identify key variables in intercultural “effectiveness” or “cross-cultural” competency. Researchers in communication worked toward not only identifying but also assessing these variables (Hammer, Gudykunst, & Wiseman, 1978 ; Ruben & Kealey, 1979 ), primarily using quantitative methods. Ruben, Askling, and Kealey ( 1977 ) provided a detailed account of “facets of cross-cultural effectiveness” identified by various researchers.

In the 1980s, research in ICC continued to gain momentum, with a special issue of the International Journal of Intercultural Relations dedicated to this topic. ICC was still approached from the point of view of two specific cultures interacting with each other, similar to the acculturation approach in the previous decade. Many of the conceptualizations of ICC were derived from (interpersonal) communication competence, extending this to intercultural contexts. For example, Spitzberg and Cupach’s ( 1984 ) conceptualization of communication competence as effective and appropriate communication has been foundational to later work in ICC.

Researchers in the 1990s built on the work of others before them. Chen ( 1990 ) presented eleven propositions and fifteen theorems in regards to the components of ICC, building from a discussion of Dinges’ ( 1983 ) six approaches to studying effective and appropriate communication in intercultural contexts. Chen went on to propose that competence is both inherent and learned. The 1993 volume of the International and Intercultural Communication Annual was dedicated to ICC, introducing some of the theories that later become influential in intercultural research, such as Gudykunst’s ( 1993 ) Anxiety/Uncertainty Management (AUM) theory, Cupach and Imahori’s ( 1993 ) Identity Management theory, and Ting-Toomey’s ( 1993 ) Identity Negotiation theory. Contributions to intercultural competence theory came from other disciplines as well, such as a learning model for becoming interculturally competent (Taylor, 1994 ) and an instructional model of intercultural strategic competence (Milhouse, 1996 ), for example. The formation of the International Academy for Intercultural Research, in 1997 , marked a significant step toward interdisciplinary collaboration in intercultural research. Research in the 1990s contributed to the strides made in the 2000s.

In a meta-review of ICC, Bradford, Allen, and Beisser ( 2000 ) observed that ICC and intercultural communication effectiveness have been used (conceptually) interchangeably in previous research. Despite the different labels under which this topic has been studied, Arasaratnam and Doerfel ( 2005 ) made the case for the culture-general nature of ICC, and Deardorff ( 2006 ) demonstrated that there is consensus amongst experts as to what ICC is. The publication of the SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence (Deardorff, 2009 ) and Spitzberg and Chagnon’s ( 2009 ) comprehensive introductory chapter on conceptualizing intercultural competence are other noteworthy contributions to literature in intercultural competence. In 2015 , the publication of another special issue on intercultural competence by the International Journal of Intercultural Relations (some 25 years after the 1989 special issue) signals that intercultural competence continues to be a topic of interest amongst researchers in communication and other disciplines. As discussed in the Research Directions section, the areas that are yet to be explored would hopefully be addressed in future research.

Further Reading

- Arasaratnam, L. A. (2014). Ten years of research in intercultural communication competence (2003–2013): A retrospective. Journal of Intercultural Communication , 35 .

- Arasaratnam, L. A. , & Deardorff, D. K. (Eds.). (2015). Intercultural competence [Special issue]. International Journal of Intercultural Relations , 48 .

- Bennett, J. M. (2015). The SAGE encyclopedia of intercultural competence . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Bradford, L. , Allen, M. , & Beisser, K. R. (2000). An evaluation and meta-analysis of intercultural communication competence research. World Communication , 29 (1), 28–51.

- Deardorff, D. K. (2009). The SAGE handbook of intercultural competence . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Martin, J. N. (Ed.). (1989). Intercultural communication competence [Special issue]. International Journal of Intercultural Relations , 13 (3).

- Wiseman, R. L. (2002). Intercultural communication competence. In W. B. Gudykunst & B. Moody (Eds.), Handbook of international and intercultural communication (pp. 207–224). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Wiseman, R. L. , & Koester, J. (1993). Intercultural communication competence . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Arasaratnam, L. A. (2007). Empirical research in intercultural communication competence: A review and recommendation. Australian Journal of Communication , 34 , 105–117.

- Arasaratnam, L. A. , & Banerjee, S. C. (2011). Sensation seeking and intercultural communication competence: A model test. International Journal of Intercultural Relations , 35 , 226–233.

- Arasaratnam, L. A. , & Doerfel, M. L. (2005). Intercultural communication competence: Identifying key components from multicultural perspectives. International Journal of Intercultural Relations , 29 , 137–163.

- Argyris, C. (1965). Explorations in interpersonal competence-I. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science , 1 , 58–83.

- Bauer, I. M. , & Baumeister, R. F. (2013). Self-knowledge. In D. Reisberg (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of cognitive psychology [online publication]. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Beamer, L. (1992). Learning intercultural competence. International Journal of Business Communication , 29 (3), 285–303.

- Bennett, M. J. (1986). A developmental approach to training for intercultural sensitivity. International Journal of Intercultural Relations , 10 , 179–196.

- Berger, C. R. , & Calabrese, R. J. (1975). Some explorations in initial interaction and beyond: Toward a developmental theory of interpersonal communication. Human Communication Theory , 1 , 99–112.

- Bhawuk, D. P. S. , & Brislin, R. W. (1992). The measurement of intercultural sensitivity using the concepts of individualism and collectivism. International Journal of Intercultural Relations , 16 (4), 413–436.

- Bieri, J. (1955). Cognitive complexity-simplicity and predictive behaviour. Journal of Abnormal & Social Psychology , 51 , 263–268.

- Blight, M. (2012). Cultures education in the primary years: Promoting active global citizenship in a changing world. Journal of Student Engagement: Educational Matters , 2 (1), 49–53.

- Bodenhausen, G. V. , & Gawronski, B. (2013). Attitude change. In D. Reisberg (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of cognitive psychology [online publication]. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bow, C. , Woodward, R. , Flynn, E. , & Stevens, M. (2013). Can I ask you something about your personal life? Sensitive questioning in intercultural doctor-patient interviews. Focus on Health Professional Education , 15 (2), 67–77.

- Bowler, M. C. , Bowler, J. L. , & Cope, J. G. (2012). Further evidence of the impact of cognitive complexity on the five-factor model. Social Behaviour and Personality , 40 (7), 1083–1098.

- Bradford, L. , Allen, M. , & Beisser, K. R. (2000). Meta-analysis of intercultural communication competence research. World Communication , 29 (1), 28–51.

- Charles, L. , Hendrika, M. , Abrams, S. , Shea, J. , Brand, G. , & Nicol, P. (2014). Expanding worldview: Australian nursing students’ experience of cultural immersion in India. Contemporary Nurse: A Journal for the Australian Nursing Profession , 48 (1), 67–75.

- Chen, G. M. (1990). Intercultural communication competence: Some perspectives of research. The Howard Journal of Communications , 2 (3), 243–261.

- Chen, G. M. , & Starosta, W. J. (1997). A review of the concept of intercultural sensitivity. Human Communication , 1 , 1–16.

- Chen, G. M. , & Starosta, W. J. (2000). The development and validation of the intercultural communication sensitivity scale. Human Communication , 3 , 1–15.

- Collier, M. J. (1986). Culture and gender: Effects on assertive behavior and communication competence. In M. McLaughlin (Ed.), Communication yearbook 9 (pp. 576–592). Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE.

- Cupach, W. R. , & Imahori, T. T. (1993). Identity management theory: Communication competence in intercultural episodes and relationships. In R. L Wiseman & J. Koester (Eds.), Intercultural communication competence (pp. 112–131). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Deardorff, D. K. (2006). Identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization. Journal of Studies in Intercultural Education , 10 , 241–266.

- Dinges, N. (1983). Intercultural competence. In D. Landis & R. W. Brislin (Eds.), Handbook of intercultural training (Vol. 1) : Issues in theory and design (pp. 176–202). New York: Pergamon.

- Duronto, P. M. , Nishida, T. , & Nakayama, S. I. (2005). Uncertainty, anxiety, and avoidance in communication with strangers. International Journal of Intercultural Relations , 29 (5), 549–560.

- Fantini, A. E. (2009). Assessing intercultural competence. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence (pp. 456–476). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Gardner, G. H. (1962). Cross-cultural communication. Journal of Social Psychology , 58 , 241–256.

- Gibson, D. W. , & Zhong, M. (2005). Intercultural communication competence in the healthcare context. International Journal of Intercultural Relations , 29 , 621–634.

- Greenholtz, J. (2000). Assessing cross-cultural competence in transnational education: The intercultural development inventory. Higher Education in Europe , 25 (3), 411–416.

- Gudykunst, W. B. (1988). Uncertainty and anxiety. In Y. Kim & W. Gudykunst (Eds.), Theories in intercultural communication (pp. 123–156). Newbury Park, CA: SAGE.

- Gudykunst, W. B. (1993). Toward a theory of effective interpersonal and intergroup communication: An anxiety/uncertainty management (AUM) perspective. In R. L Wiseman & J. Koester (Eds.), Intercultural communication competence (pp. 33–71). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Gudykunst, W. B. (1995). Anxiety/uncertainty management (AUM) theory. In R. Wiseman (Ed.), Intercultural communication theory (pp. 8–58). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Gudykunst, W. B. (2005). An anxiety/uncertainty management (AUM) theory of effective communication: Making the mesh of the net finer. In W. B. Gudykunst (Ed.), Theorizing about intercultural communication (pp. 281–322). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Gudykunst, W. B. , & Kim, Y. (2003). Communicating with strangers: An approach to intercultural communication . New York: McGraw Hill.

- Guthrie, G. M. , & Zetrick, I. N. (1967). Predicting performance in the Peace Corps. Journal of Social Psychology , 71 , 11–21.

- Hammer, M. R. (1987). Behavioral dimensions of intercultural effectiveness: A replication and extension. International Journal of Intercultural Relations , 11 , 65–88.

- Hammer, M. R. , Bennett, M. J. , & Wiseman, R. L. (2003). Measuring intercultural sensitivity: The intercultural development inventory. International Journal of Intercultural Relations , 27 , 421–443.

- Hammer, M. R. , Gudykunst, W. B. , & Wiseman, R. L. (1978). Dimensions of intercultural effectiveness: An exploratory study. International Journal of Intercultural Relations , 2 (4), 382–393.

- Helm, F. (2009). Language and culture in an online context: What can learner diaries tell us about intercultural competence? Language & Intercultural Communication , 9 , 91–104.

- Imohari, T. , & Lanigan, M. (1989). Relational model of intercultural communication competence. International Journal of Intercultural Relations , 13 (3), 269–289.

- Kealey, D. J. (1989). A study of cross-cultural effectiveness: Theoretical issues, practical applications. International Journal of Intercultural Relations , 13 (3), 397–428.

- Koester, J. , & Olebe, M. (1988). The behavioral assessment scale for intercultural communication effectiveness. International Journal of Intercultural Relations , 12 , 233–246.

- Kim, Y. (1991). Intercultural communication competence. In S. Ting-Toomey & F. Korzennt (Eds.), Cross-cultural personal communication (pp. 259–275). Newbury Park, CA: SAGE.

- Kim, Y. (1995). Cross-cultural adaptation: An integrative theory. In R. L. Wiseman (Ed.), Intercultural communication theory (pp. 170–193). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Kim, Y. (2009). The identity factor in intercultural competence. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence (pp. 53–65). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Koester, J. , Wiseman, R. L. , & Sanders, J. A. (1993). Multiple perspectives of intercultural communication competence. In R. L Wiseman & J. Koester (Eds.), Intercultural communication competence (pp. 3–15). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Landis, D. , Bennett, J. , & Bennett, M. (2004). Handbook of intercultural training . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Martin, J. N. (1987). The relationship between student sojourner perceptions of intercultural competencies and previous sojourn experience. International Journal of Intercultural Relations , 11 , 337–355.

- Matsumoto, D. , & Hwang, H. C. (2013). Assessing cross-cultural competence: A review of available tests. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology , 44 (6), 849–873.

- Milhouse, V. H. (1996). Intercultural strategic competence: An effective tool collectivist and individualist students can use to better understand each other. Journal of Instructional Psychology , 23 (1), 45–52.

- Miyamoto, Y. , & Wilken, B. (2013). Cultural differences and their mechanisms. In D. Reisberg (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of cognitive psychology [online publication]. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Morgan, S. E. , & Arasaratnam, L. A. (2003). Intercultural friendships as social excitation: Sensation seeking as a predictor of intercultural friendship seeking behavior. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research , 32 , 175–186.

- Moskowitz, G. B. , & Gill, M. J. (2013). Person perception. In D. Reisberg (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of cognitive psychology [online publication]. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nesdale, D. , De Vries Robbé, M. , & Van Oudenhoven, J. P. (2012). Intercultural effectiveness, authoritarianism, and ethnic prejudice. Journal of Applied Social Psychology , 42 , 1173–1191.

- Neuliep, J. W. (2002). Assessing the reliability and validity of the generalized ethnocentrism scale. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research , 31 (4), 201–215.

- Neuliep, J. W. (2012). The relationship among intercultural communication apprehension, ethnocentrism, uncertainty reduction, and communication satisfaction during initial intercultural interaction: An extension of Anxiety Uncertainty Management (AUM) theory. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research , 41 (1), 1–16.

- Ni, L. , & Wang, Q. (2011). Anxiety and uncertainty management in an intercultural setting: The impact on organization-public relationships. Journal of Public Relations , 23 (3), 269–301.

- Nishida, H. (1985). Japanese intercultural communication competence and cross-cultural adjustment. International Journal of Intercultural Relations , 9 (3), 247–269.

- Oetzel, J. , Meares, M. , Myers, K. K. , & Lara, E. (2003). Interpersonal conflict in organizations: Explaining conflict styles via face-negotiation theory. Communication Research Reports , 20 (2), 106–115.

- Reid, L. D. , & Foels, R. (2010). Cognitive complexity and the perception of subtle racism. Basic and Applied Social Psychology , 32 , 291–301.

- Ruben, B. D. (1976). Assessing communication competency for intercultural adaptation. Group and Organization Studies , 1 , 334–354.

- Ruben, B. D. , Askling, L. R. , & Kealey, D. J. (1977). Cross-cultural effectiveness. In D. S. Hoopes , P. B. Pedersen , and G. Renwick (Eds.), Overview of intercultural education, training, and research . (Vol. I): Theory (pp. 92–105). Washington, DC: Society for Intercultural Education, Training, and Research.

- Ruben, B. D. , & Kealey, D. J. (1979). Behavioral assessment of communication competency and the prediction of cross-cultural adaptation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations , 3 (1), 15–47.

- Sample, S. G. (2013). Developing intercultural learners through the international curriculum. Journal of Studies in International Education , 17 (5), 554–572.

- Sandage, S. J. , & Jankowski, P. J. (2013). Spirituality, social justice, and intercultural competence: Mediator effects for differentiation of self. International Journal of Intercultural Relations , 37 , 366–374.

- Smith, M. B. (1966). Explorations in competence: A study of Peace Corps teachers in Ghana. American Psychologist , 21 , 555–566.

- Smith, R. A. , & Downs, E. (2004). Flying across cultural divides: Sensation seeking and engagement in intercultural communication. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research , 33 (3), 223–230.

- Spitzberg, B. H. (1983). Communication competence as knowledge, skill, and impression. Communication Education , 32 , 323–329.

- Spitzberg, B. H. (2000). A model of intercultural communication competence. In L. Samovar & R. Porter (Eds.), Intercultural communication: A reader (pp. 375–387). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Spitzberg, B. H. , & Chagnon, G. (2009). Conceptualizing intercultural competence. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence (pp. 2–52). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Spitzberg, B. H. , & Cupach, W. R. (1984). Interpersonal communication competence . Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE.

- Saunders, J. A. , Haskins, M. , & Vasquez, M. (2015). Cultural competence: A journey to an elusive goal. Journal of Social Work Education , 51 , 19–34.

- Tangen, D. , Mercer, K. L. , Spooner-Lane, R. , & Hepple, E. (2011). Exploring intercultural competence: A service-learning approach. Australian Journal of Teacher Education , 36 (11), 62–72.

- Taylor, E. W. (1994). A learning model for becoming interculturally competent. International Journal of Intercultural Relations , 18 (3), 389–408.

- Tervalon, M. , & Murray-Garcia, J. (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in identifying physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Undeserved , 9 (2), 117–125.

- Ting-Toomey, S. (1988). Intercultural conflicts: A face-negotiation theory. In Y. Y. Kim and W. B. Gudykunst (Eds.), Theories in intercultural communication (pp. 213–235). Newbury Park, CA: SAGE.

- Ting-Toomey, S. (1993). Communicative resourcefulness: An identity negotiation perspective. In R. L Wiseman & J. Koester (Eds.), Intercultural communication competence (pp. 72–111). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Ting-Toomey, S. , & Kurogi, A. (1998). Facework competence in intercultural conflict: An updated face-negotiation theory. International Journal of Intercultural Relations , 22 , 187–225.

- Van de Vijver, F. J. R. , & Leung, K. (1997). Methods and data analysis for cross-cultural research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Van de Vijver, F. J. R. , & Leung, K. (2011). Equivalence and bias: A review of concepts, models, and data analytic procedures. In D. Matsumoto & F. J. R. Van de Vijver (Eds.), Cross-cultural research methods in psychology (pp. 17–45). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Van Oudenhoven, J. P. , & Van der Zee, K. (2002). Predicting multicultural effectiveness of international students: The multicultural personality questionnaire. International Journal of Intercultural Relations , 26 , 679–694.

- Wang, J. (2013). Moving towards ethnorelativism: A framework for measuring and meeting students’ needs in cross-cultural business and technical communication. Journal of Technical Writing & Communication , 43 (2), 201–218.

- White, R. W. (1959). Motivation reconsidered: The concept of competence. Psychological Review , 66 (5), 297–333.

- Wiseman, R. L. (2002). Intercultural communication competence. In W. B. Gudykunst and B. Moody (Eds.), Handbook of international and intercultural communication (pp. 207–224). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Wiseman, R. L. , & Abe, H. (1986). Cognitive complexity and intercultural effectiveness. In M. McLaughlin (Ed.), Communication yearbook 9 (pp. 611–624). Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE.

- Witteborn, S. (2003). Communicative competence revisited: An emic approach to studying intercultural communicative competence. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research , 32 , 187–203.

- Yoshitake, M. (2002). Anxiety/uncertainty management (AUM) theory: A critical examination of an intercultural communication theory. Intercultural Communication Studies , 11 , 177–193.

- Zakaria, N. , Amelinckx, A. , & Wilemon, D. (2004). Working together apart? Building a knowledge-sharing culture for global virtual teams. Creativity and Innovation Management , 13 (1), 15–29.

- Zhang, H. (2012). Collaborative learning as a pedagogical tool to develop intercultural competence in a multicultural class. China Media Research , 8 , 107–111.

Related Articles

- Women Entrepreneurs, Global Microfinance, and Development 2.0

- Movements and Resistance in the United States, 1800 to the Present

- Rhetorical Construction of Bodies

- Intercultural Friendships

- A Culture-Centered Approach to Health and Risk Communication

- Race, Nationalism, and Transnationalism

- Methods for Intercultural Communication Research

- Globalizing and Changing Culture

- Communication Skill and Competence

- Intercultural Conflict

- Anxiety, Uncertainty, and Intercultural Communication

- Bella Figura: Understanding Italian Communication in Local and Transatlantic Contexts

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Communication. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 26 June 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [185.39.149.46]

- 185.39.149.46

Character limit 500 /500

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8.3 Intercultural Communication

Learning objectives.

- Define intercultural communication.

- List and summarize the six dialectics of intercultural communication.

- Discuss how intercultural communication affects interpersonal relationships.

It is through intercultural communication that we come to create, understand, and transform culture and identity. Intercultural communication is communication between people with differing cultural identities. One reason we should study intercultural communication is to foster greater self-awareness (Martin & Nakayama, 2010). Our thought process regarding culture is often “other focused,” meaning that the culture of the other person or group is what stands out in our perception. However, the old adage “know thyself” is appropriate, as we become more aware of our own culture by better understanding other cultures and perspectives. Intercultural communication can allow us to step outside of our comfortable, usual frame of reference and see our culture through a different lens. Additionally, as we become more self-aware, we may also become more ethical communicators as we challenge our ethnocentrism , or our tendency to view our own culture as superior to other cultures.

As was noted earlier, difference matters, and studying intercultural communication can help us better negotiate our changing world. Changing economies and technologies intersect with culture in meaningful ways (Martin & Nakayama). As was noted earlier, technology has created for some a global village where vast distances are now much shorter due to new technology that make travel and communication more accessible and convenient (McLuhan, 1967). However, as the following “Getting Plugged In” box indicates, there is also a digital divide , which refers to the unequal access to technology and related skills that exists in much of the world. People in most fields will be more successful if they are prepared to work in a globalized world. Obviously, the global market sets up the need to have intercultural competence for employees who travel between locations of a multinational corporation. Perhaps less obvious may be the need for teachers to work with students who do not speak English as their first language and for police officers, lawyers, managers, and medical personnel to be able to work with people who have various cultural identities.

“Getting Plugged In”

The Digital Divide

Many people who are now college age struggle to imagine a time without cell phones and the Internet. As “digital natives” it is probably also surprising to realize the number of people who do not have access to certain technologies. The digital divide was a term that initially referred to gaps in access to computers. The term expanded to include access to the Internet since it exploded onto the technology scene and is now connected to virtually all computing (van Deursen & van Dijk, 2010). Approximately two billion people around the world now access the Internet regularly, and those who don’t face several disadvantages (Smith, 2011). Discussions of the digital divide are now turning more specifically to high-speed Internet access, and the discussion is moving beyond the physical access divide to include the skills divide, the economic opportunity divide, and the democratic divide. This divide doesn’t just exist in developing countries; it has become an increasing concern in the United States. This is relevant to cultural identities because there are already inequalities in terms of access to technology based on age, race, and class (Sylvester & McGlynn, 2010). Scholars argue that these continued gaps will only serve to exacerbate existing cultural and social inequalities. From an international perspective, the United States is falling behind other countries in terms of access to high-speed Internet. South Korea, Japan, Sweden, and Germany now all have faster average connection speeds than the United States (Smith, 2011). And Finland in 2010 became the first country in the world to declare that all its citizens have a legal right to broadband Internet access (ben-Aaron, 2010). People in rural areas in the United States are especially disconnected from broadband service, with about 11 million rural Americans unable to get the service at home. As so much of our daily lives go online, it puts those who aren’t connected at a disadvantage. From paying bills online, to interacting with government services, to applying for jobs, to taking online college classes, to researching and participating in political and social causes, the Internet connects to education, money, and politics.

- What do you think of Finland’s inclusion of broadband access as a legal right? Is this something that should be done in other countries? Why or why not?

- How does the digital divide affect the notion of the global village?

- How might limited access to technology negatively affect various nondominant groups?

Intercultural Communication: A Dialectical Approach

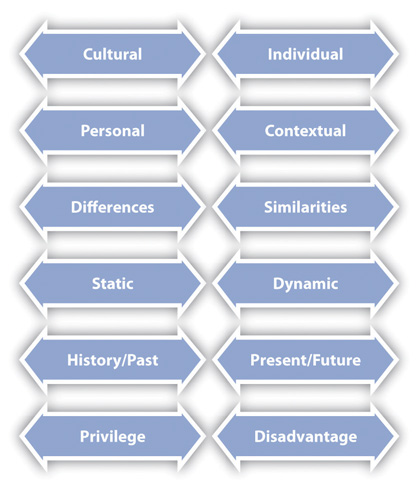

Intercultural communication is complicated, messy, and at times contradictory. Therefore it is not always easy to conceptualize or study. Taking a dialectical approach allows us to capture the dynamism of intercultural communication. A dialectic is a relationship between two opposing concepts that constantly push and pull one another (Martin & Nakayama, 2010). To put it another way, thinking dialectically helps us realize that our experiences often occur in between two different phenomena. This perspective is especially useful for interpersonal and intercultural communication, because when we think dialectically, we think relationally. This means we look at the relationship between aspects of intercultural communication rather than viewing them in isolation. Intercultural communication occurs as a dynamic in-betweenness that, while connected to the individuals in an encounter, goes beyond the individuals, creating something unique. Holding a dialectical perspective may be challenging for some Westerners, as it asks us to hold two contradictory ideas simultaneously, which goes against much of what we are taught in our formal education. Thinking dialectically helps us see the complexity in culture and identity because it doesn’t allow for dichotomies. Dichotomies are dualistic ways of thinking that highlight opposites, reducing the ability to see gradations that exist in between concepts. Dichotomies such as good/evil, wrong/right, objective/subjective, male/female, in-group/out-group, black/white, and so on form the basis of much of our thoughts on ethics, culture, and general philosophy, but this isn’t the only way of thinking (Marin & Nakayama, 1999). Many Eastern cultures acknowledge that the world isn’t dualistic. Rather, they accept as part of their reality that things that seem opposite are actually interdependent and complement each other. I argue that a dialectical approach is useful in studying intercultural communication because it gets us out of our comfortable and familiar ways of thinking. Since so much of understanding culture and identity is understanding ourselves, having an unfamiliar lens through which to view culture can offer us insights that our familiar lenses will not. Specifically, we can better understand intercultural communication by examining six dialectics (see Figure 8.1 “Dialectics of Intercultural Communication” ) (Martin & Nakayama, 1999).

Figure 8.1 Dialectics of Intercultural Communication

Source: Adapted from Judith N. Martin and Thomas K. Nakayama, “Thinking Dialectically about Culture and Communication,” Communication Theory 9, no. 1 (1999): 1–25.

The cultural-individual dialectic captures the interplay between patterned behaviors learned from a cultural group and individual behaviors that may be variations on or counter to those of the larger culture. This dialectic is useful because it helps us account for exceptions to cultural norms. For example, earlier we learned that the United States is said to be a low-context culture, which means that we value verbal communication as our primary, meaning-rich form of communication. Conversely, Japan is said to be a high-context culture, which means they often look for nonverbal clues like tone, silence, or what is not said for meaning. However, you can find people in the United States who intentionally put much meaning into how they say things, perhaps because they are not as comfortable speaking directly what’s on their mind. We often do this in situations where we may hurt someone’s feelings or damage a relationship. Does that mean we come from a high-context culture? Does the Japanese man who speaks more than is socially acceptable come from a low-context culture? The answer to both questions is no. Neither the behaviors of a small percentage of individuals nor occasional situational choices constitute a cultural pattern.

The personal-contextual dialectic highlights the connection between our personal patterns of and preferences for communicating and how various contexts influence the personal. In some cases, our communication patterns and preferences will stay the same across many contexts. In other cases, a context shift may lead us to alter our communication and adapt. For example, an American businesswoman may prefer to communicate with her employees in an informal and laid-back manner. When she is promoted to manage a department in her company’s office in Malaysia, she may again prefer to communicate with her new Malaysian employees the same way she did with those in the United States. In the United States, we know that there are some accepted norms that communication in work contexts is more formal than in personal contexts. However, we also know that individual managers often adapt these expectations to suit their own personal tastes. This type of managerial discretion would likely not go over as well in Malaysia where there is a greater emphasis put on power distance (Hofstede, 1991). So while the American manager may not know to adapt to the new context unless she has a high degree of intercultural communication competence, Malaysian managers would realize that this is an instance where the context likely influences communication more than personal preferences.

The differences-similarities dialectic allows us to examine how we are simultaneously similar to and different from others. As was noted earlier, it’s easy to fall into a view of intercultural communication as “other oriented” and set up dichotomies between “us” and “them.” When we overfocus on differences, we can end up polarizing groups that actually have things in common. When we overfocus on similarities, we essentialize , or reduce/overlook important variations within a group. This tendency is evident in most of the popular, and some of the academic, conversations regarding “gender differences.” The book Men Are from Mars and Women Are from Venus makes it seem like men and women aren’t even species that hail from the same planet. The media is quick to include a blurb from a research study indicating again how men and women are “wired” to communicate differently. However, the overwhelming majority of current research on gender and communication finds that while there are differences between how men and women communicate, there are far more similarities (Allen, 2011). Even the language we use to describe the genders sets up dichotomies. That’s why I suggest that my students use the term other gender instead of the commonly used opposite sex . I have a mom, a sister, and plenty of female friends, and I don’t feel like any of them are the opposite of me. Perhaps a better title for a book would be Women and Men Are Both from Earth .

The static-dynamic dialectic suggests that culture and communication change over time yet often appear to be and are experienced as stable. Although it is true that our cultural beliefs and practices are rooted in the past, we have already discussed how cultural categories that most of us assume to be stable, like race and gender, have changed dramatically in just the past fifty years. Some cultural values remain relatively consistent over time, which allows us to make some generalizations about a culture. For example, cultures have different orientations to time. The Chinese have a longer-term orientation to time than do Europeans (Lustig & Koester, 2006). This is evidenced in something that dates back as far as astrology. The Chinese zodiac is done annually (The Year of the Monkey, etc.), while European astrology was organized by month (Taurus, etc.). While this cultural orientation to time has been around for generations, as China becomes more Westernized in terms of technology, business, and commerce, it could also adopt some views on time that are more short term.

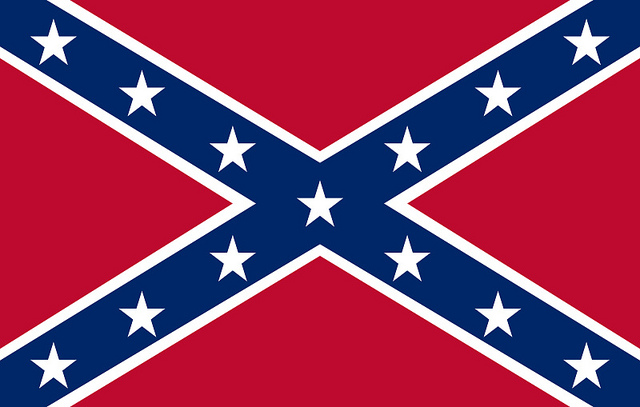

The history/past-present/future dialectic reminds us to understand that while current cultural conditions are important and that our actions now will inevitably affect our future, those conditions are not without a history. We always view history through the lens of the present. Perhaps no example is more entrenched in our past and avoided in our present as the history of slavery in the United States. Where I grew up in the Southern United States, race was something that came up frequently. The high school I attended was 30 percent minorities (mostly African American) and also had a noticeable number of white teens (mostly male) who proudly displayed Confederate flags on their clothing or vehicles.

There has been controversy over whether the Confederate flag is a symbol of hatred or a historical symbol that acknowledges the time of the Civil War.

Jim Surkamp – Confederate Rebel Flag – CC BY-NC 2.0.

I remember an instance in a history class where we were discussing slavery and the subject of repatriation, or compensation for descendants of slaves, came up. A white male student in the class proclaimed, “I’ve never owned slaves. Why should I have to care about this now?” While his statement about not owning slaves is valid, it doesn’t acknowledge that effects of slavery still linger today and that the repercussions of such a long and unjust period of our history don’t disappear over the course of a few generations.

The privileges-disadvantages dialectic captures the complex interrelation of unearned, systemic advantages and disadvantages that operate among our various identities. As was discussed earlier, our society consists of dominant and nondominant groups. Our cultures and identities have certain privileges and/or disadvantages. To understand this dialectic, we must view culture and identity through a lens of intersectionality , which asks us to acknowledge that we each have multiple cultures and identities that intersect with each other. Because our identities are complex, no one is completely privileged and no one is completely disadvantaged. For example, while we may think of a white, heterosexual male as being very privileged, he may also have a disability that leaves him without the able-bodied privilege that a Latina woman has. This is often a difficult dialectic for my students to understand, because they are quick to point out exceptions that they think challenge this notion. For example, many people like to point out Oprah Winfrey as a powerful African American woman. While she is definitely now quite privileged despite her disadvantaged identities, her trajectory isn’t the norm. When we view privilege and disadvantage at the cultural level, we cannot let individual exceptions distract from the systemic and institutionalized ways in which some people in our society are disadvantaged while others are privileged.

As these dialectics reiterate, culture and communication are complex systems that intersect with and diverge from many contexts. A better understanding of all these dialectics helps us be more critical thinkers and competent communicators in a changing world.

“Getting Critical”

Immigration, Laws, and Religion

France, like the United States, has a constitutional separation between church and state. As many countries in Europe, including France, Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden, have experienced influxes of immigrants, many of them Muslim, there have been growing tensions among immigration, laws, and religion. In 2011, France passed a law banning the wearing of a niqab (pronounced knee-cobb ), which is an Islamic facial covering worn by some women that only exposes the eyes. This law was aimed at “assimilating its Muslim population” of more than five million people and “defending French values and women’s rights” (De La Baume & Goodman, 2011). Women found wearing the veil can now be cited and fined $150 euros. Although the law went into effect in April of 2011, the first fines were issued in late September of 2011. Hind Ahmas, a woman who was fined, says she welcomes the punishment because she wants to challenge the law in the European Court of Human Rights. She also stated that she respects French laws but cannot abide by this one. Her choice to wear the veil has been met with more than a fine. She recounts how she has been denied access to banks and other public buildings and was verbally harassed by a woman on the street and then punched in the face by the woman’s husband. Another Muslim woman named Kenza Drider, who can be seen in Video Clip 8.2, announced that she will run for the presidency of France in order to challenge the law. The bill that contained the law was broadly supported by politicians and the public in France, and similar laws are already in place in Belgium and are being proposed in Italy, Austria, the Netherlands, and Switzerland (Fraser, 2011).

- Some people who support the law argue that part of integrating into Western society is showing your face. Do you agree or disagree? Why?

- Part of the argument for the law is to aid in the assimilation of Muslim immigrants into French society. What are some positives and negatives of this type of assimilation?

- Identify which of the previously discussed dialectics can be seen in this case. How do these dialectics capture the tensions involved?

Video Clip 8.2

Veiled Woman Eyes French Presidency

(click to see video)

Intercultural Communication and Relationships

Intercultural relationships are formed between people with different cultural identities and include friends, romantic partners, family, and coworkers. Intercultural relationships have benefits and drawbacks. Some of the benefits include increasing cultural knowledge, challenging previously held stereotypes, and learning new skills (Martin & Nakayama, 2010). For example, I learned about the Vietnamese New Year celebration Tet from a friend I made in graduate school. This same friend also taught me how to make some delicious Vietnamese foods that I continue to cook today. I likely would not have gained this cultural knowledge or skill without the benefits of my intercultural friendship. Intercultural relationships also present challenges, however.

The dialectics discussed earlier affect our intercultural relationships. The similarities-differences dialectic in particular may present challenges to relationship formation (Martin & Nakayama, 2010). While differences between people’s cultural identities may be obvious, it takes some effort to uncover commonalities that can form the basis of a relationship. Perceived differences in general also create anxiety and uncertainty that is not as present in intracultural relationships. Once some similarities are found, the tension within the dialectic begins to balance out and uncertainty and anxiety lessen. Negative stereotypes may also hinder progress toward relational development, especially if the individuals are not open to adjusting their preexisting beliefs. Intercultural relationships may also take more work to nurture and maintain. The benefit of increased cultural awareness is often achieved, because the relational partners explain their cultures to each other. This type of explaining requires time, effort, and patience and may be an extra burden that some are not willing to carry. Last, engaging in intercultural relationships can lead to questioning or even backlash from one’s own group. I experienced this type of backlash from my white classmates in middle school who teased me for hanging out with the African American kids on my bus. While these challenges range from mild inconveniences to more serious repercussions, they are important to be aware of. As noted earlier, intercultural relationships can take many forms. The focus of this section is on friendships and romantic relationships, but much of the following discussion can be extended to other relationship types.

Intercultural Friendships