Qualitative vs Quantitative Research Methods & Data Analysis

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

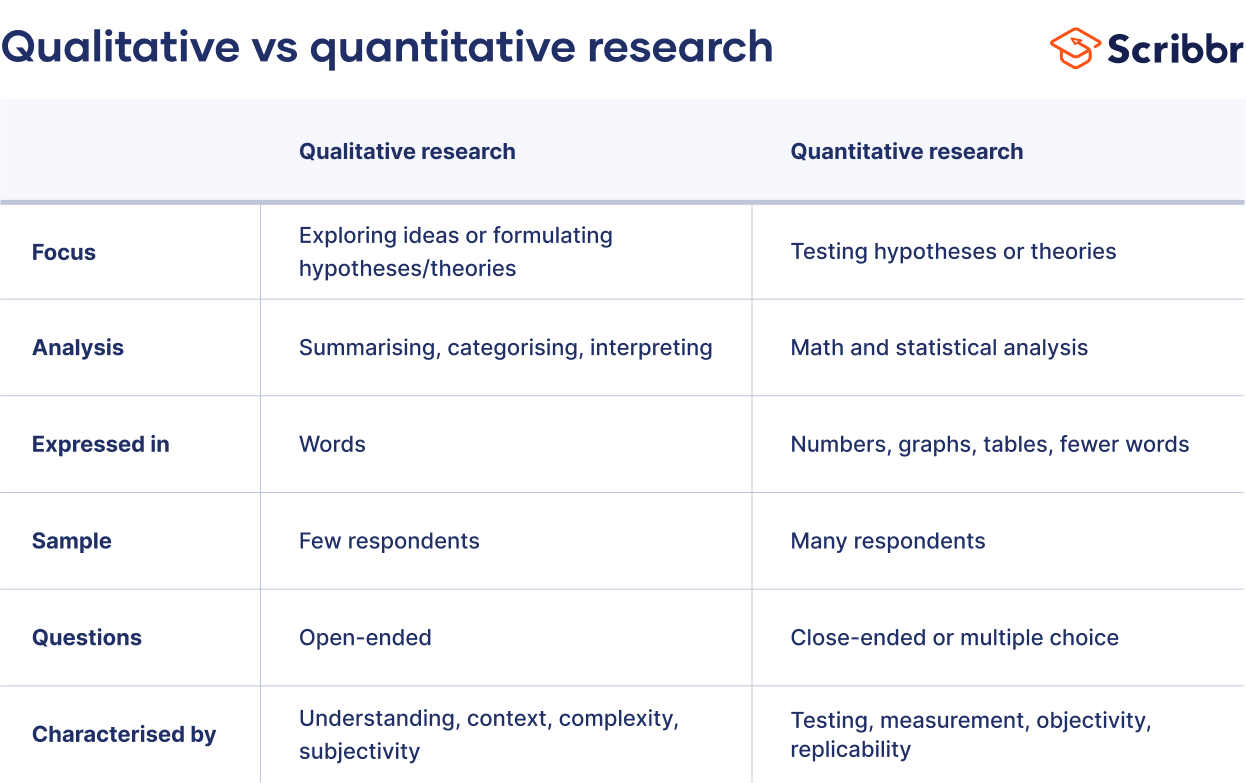

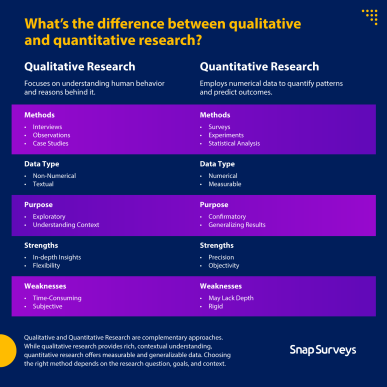

What is the difference between quantitative and qualitative?

The main difference between quantitative and qualitative research is the type of data they collect and analyze.

Quantitative research collects numerical data and analyzes it using statistical methods. The aim is to produce objective, empirical data that can be measured and expressed in numerical terms. Quantitative research is often used to test hypotheses, identify patterns, and make predictions.

Qualitative research , on the other hand, collects non-numerical data such as words, images, and sounds. The focus is on exploring subjective experiences, opinions, and attitudes, often through observation and interviews.

Qualitative research aims to produce rich and detailed descriptions of the phenomenon being studied, and to uncover new insights and meanings.

Quantitative data is information about quantities, and therefore numbers, and qualitative data is descriptive, and regards phenomenon which can be observed but not measured, such as language.

What Is Qualitative Research?

Qualitative research is the process of collecting, analyzing, and interpreting non-numerical data, such as language. Qualitative research can be used to understand how an individual subjectively perceives and gives meaning to their social reality.

Qualitative data is non-numerical data, such as text, video, photographs, or audio recordings. This type of data can be collected using diary accounts or in-depth interviews and analyzed using grounded theory or thematic analysis.

Qualitative research is multimethod in focus, involving an interpretive, naturalistic approach to its subject matter. This means that qualitative researchers study things in their natural settings, attempting to make sense of, or interpret, phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them. Denzin and Lincoln (1994, p. 2)

Interest in qualitative data came about as the result of the dissatisfaction of some psychologists (e.g., Carl Rogers) with the scientific study of psychologists such as behaviorists (e.g., Skinner ).

Since psychologists study people, the traditional approach to science is not seen as an appropriate way of carrying out research since it fails to capture the totality of human experience and the essence of being human. Exploring participants’ experiences is known as a phenomenological approach (re: Humanism ).

Qualitative research is primarily concerned with meaning, subjectivity, and lived experience. The goal is to understand the quality and texture of people’s experiences, how they make sense of them, and the implications for their lives.

Qualitative research aims to understand the social reality of individuals, groups, and cultures as nearly as possible as participants feel or live it. Thus, people and groups are studied in their natural setting.

Some examples of qualitative research questions are provided, such as what an experience feels like, how people talk about something, how they make sense of an experience, and how events unfold for people.

Research following a qualitative approach is exploratory and seeks to explain ‘how’ and ‘why’ a particular phenomenon, or behavior, operates as it does in a particular context. It can be used to generate hypotheses and theories from the data.

Qualitative Methods

There are different types of qualitative research methods, including diary accounts, in-depth interviews , documents, focus groups , case study research , and ethnography.

The results of qualitative methods provide a deep understanding of how people perceive their social realities and in consequence, how they act within the social world.

The researcher has several methods for collecting empirical materials, ranging from the interview to direct observation, to the analysis of artifacts, documents, and cultural records, to the use of visual materials or personal experience. Denzin and Lincoln (1994, p. 14)

Here are some examples of qualitative data:

Interview transcripts : Verbatim records of what participants said during an interview or focus group. They allow researchers to identify common themes and patterns, and draw conclusions based on the data. Interview transcripts can also be useful in providing direct quotes and examples to support research findings.

Observations : The researcher typically takes detailed notes on what they observe, including any contextual information, nonverbal cues, or other relevant details. The resulting observational data can be analyzed to gain insights into social phenomena, such as human behavior, social interactions, and cultural practices.

Unstructured interviews : generate qualitative data through the use of open questions. This allows the respondent to talk in some depth, choosing their own words. This helps the researcher develop a real sense of a person’s understanding of a situation.

Diaries or journals : Written accounts of personal experiences or reflections.

Notice that qualitative data could be much more than just words or text. Photographs, videos, sound recordings, and so on, can be considered qualitative data. Visual data can be used to understand behaviors, environments, and social interactions.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Qualitative research is endlessly creative and interpretive. The researcher does not just leave the field with mountains of empirical data and then easily write up his or her findings.

Qualitative interpretations are constructed, and various techniques can be used to make sense of the data, such as content analysis, grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006), or discourse analysis.

For example, thematic analysis is a qualitative approach that involves identifying implicit or explicit ideas within the data. Themes will often emerge once the data has been coded .

Key Features

- Events can be understood adequately only if they are seen in context. Therefore, a qualitative researcher immerses her/himself in the field, in natural surroundings. The contexts of inquiry are not contrived; they are natural. Nothing is predefined or taken for granted.

- Qualitative researchers want those who are studied to speak for themselves, to provide their perspectives in words and other actions. Therefore, qualitative research is an interactive process in which the persons studied teach the researcher about their lives.

- The qualitative researcher is an integral part of the data; without the active participation of the researcher, no data exists.

- The study’s design evolves during the research and can be adjusted or changed as it progresses. For the qualitative researcher, there is no single reality. It is subjective and exists only in reference to the observer.

- The theory is data-driven and emerges as part of the research process, evolving from the data as they are collected.

Limitations of Qualitative Research

- Because of the time and costs involved, qualitative designs do not generally draw samples from large-scale data sets.

- The problem of adequate validity or reliability is a major criticism. Because of the subjective nature of qualitative data and its origin in single contexts, it is difficult to apply conventional standards of reliability and validity. For example, because of the central role played by the researcher in the generation of data, it is not possible to replicate qualitative studies.

- Also, contexts, situations, events, conditions, and interactions cannot be replicated to any extent, nor can generalizations be made to a wider context than the one studied with confidence.

- The time required for data collection, analysis, and interpretation is lengthy. Analysis of qualitative data is difficult, and expert knowledge of an area is necessary to interpret qualitative data. Great care must be taken when doing so, for example, looking for mental illness symptoms.

Advantages of Qualitative Research

- Because of close researcher involvement, the researcher gains an insider’s view of the field. This allows the researcher to find issues that are often missed (such as subtleties and complexities) by the scientific, more positivistic inquiries.

- Qualitative descriptions can be important in suggesting possible relationships, causes, effects, and dynamic processes.

- Qualitative analysis allows for ambiguities/contradictions in the data, which reflect social reality (Denscombe, 2010).

- Qualitative research uses a descriptive, narrative style; this research might be of particular benefit to the practitioner as she or he could turn to qualitative reports to examine forms of knowledge that might otherwise be unavailable, thereby gaining new insight.

What Is Quantitative Research?

Quantitative research involves the process of objectively collecting and analyzing numerical data to describe, predict, or control variables of interest.

The goals of quantitative research are to test causal relationships between variables , make predictions, and generalize results to wider populations.

Quantitative researchers aim to establish general laws of behavior and phenomenon across different settings/contexts. Research is used to test a theory and ultimately support or reject it.

Quantitative Methods

Experiments typically yield quantitative data, as they are concerned with measuring things. However, other research methods, such as controlled observations and questionnaires , can produce both quantitative information.

For example, a rating scale or closed questions on a questionnaire would generate quantitative data as these produce either numerical data or data that can be put into categories (e.g., “yes,” “no” answers).

Experimental methods limit how research participants react to and express appropriate social behavior.

Findings are, therefore, likely to be context-bound and simply a reflection of the assumptions that the researcher brings to the investigation.

There are numerous examples of quantitative data in psychological research, including mental health. Here are a few examples:

Another example is the Experience in Close Relationships Scale (ECR), a self-report questionnaire widely used to assess adult attachment styles .

The ECR provides quantitative data that can be used to assess attachment styles and predict relationship outcomes.

Neuroimaging data : Neuroimaging techniques, such as MRI and fMRI, provide quantitative data on brain structure and function.

This data can be analyzed to identify brain regions involved in specific mental processes or disorders.

For example, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is a clinician-administered questionnaire widely used to assess the severity of depressive symptoms in individuals.

The BDI consists of 21 questions, each scored on a scale of 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms.

Quantitative Data Analysis

Statistics help us turn quantitative data into useful information to help with decision-making. We can use statistics to summarize our data, describing patterns, relationships, and connections. Statistics can be descriptive or inferential.

Descriptive statistics help us to summarize our data. In contrast, inferential statistics are used to identify statistically significant differences between groups of data (such as intervention and control groups in a randomized control study).

- Quantitative researchers try to control extraneous variables by conducting their studies in the lab.

- The research aims for objectivity (i.e., without bias) and is separated from the data.

- The design of the study is determined before it begins.

- For the quantitative researcher, the reality is objective, exists separately from the researcher, and can be seen by anyone.

- Research is used to test a theory and ultimately support or reject it.

Limitations of Quantitative Research

- Context: Quantitative experiments do not take place in natural settings. In addition, they do not allow participants to explain their choices or the meaning of the questions they may have for those participants (Carr, 1994).

- Researcher expertise: Poor knowledge of the application of statistical analysis may negatively affect analysis and subsequent interpretation (Black, 1999).

- Variability of data quantity: Large sample sizes are needed for more accurate analysis. Small-scale quantitative studies may be less reliable because of the low quantity of data (Denscombe, 2010). This also affects the ability to generalize study findings to wider populations.

- Confirmation bias: The researcher might miss observing phenomena because of focus on theory or hypothesis testing rather than on the theory of hypothesis generation.

Advantages of Quantitative Research

- Scientific objectivity: Quantitative data can be interpreted with statistical analysis, and since statistics are based on the principles of mathematics, the quantitative approach is viewed as scientifically objective and rational (Carr, 1994; Denscombe, 2010).

- Useful for testing and validating already constructed theories.

- Rapid analysis: Sophisticated software removes much of the need for prolonged data analysis, especially with large volumes of data involved (Antonius, 2003).

- Replication: Quantitative data is based on measured values and can be checked by others because numerical data is less open to ambiguities of interpretation.

- Hypotheses can also be tested because of statistical analysis (Antonius, 2003).

Antonius, R. (2003). Interpreting quantitative data with SPSS . Sage.

Black, T. R. (1999). Doing quantitative research in the social sciences: An integrated approach to research design, measurement and statistics . Sage.

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology . Qualitative Research in Psychology , 3, 77–101.

Carr, L. T. (1994). The strengths and weaknesses of quantitative and qualitative research : what method for nursing? Journal of advanced nursing, 20(4) , 716-721.

Denscombe, M. (2010). The Good Research Guide: for small-scale social research. McGraw Hill.

Denzin, N., & Lincoln. Y. (1994). Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications Inc.

Glaser, B. G., Strauss, A. L., & Strutzel, E. (1968). The discovery of grounded theory; strategies for qualitative research. Nursing research, 17(4) , 364.

Minichiello, V. (1990). In-Depth Interviewing: Researching People. Longman Cheshire.

Punch, K. (1998). Introduction to Social Research: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches. London: Sage

Further Information

- Designing qualitative research

- Methods of data collection and analysis

- Introduction to quantitative and qualitative research

- Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: a case of the tail wagging the dog?

- Qualitative research in health care: Analysing qualitative data

- Qualitative data analysis: the framework approach

- Using the framework method for the analysis of

- Qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research

- Content Analysis

- Grounded Theory

- Thematic Analysis

Related Articles

Research Methodology

Qualitative Data Coding

What Is a Focus Group?

Cross-Cultural Research Methodology In Psychology

What Is Internal Validity In Research?

Research Methodology , Statistics

What Is Face Validity In Research? Importance & How To Measure

Criterion Validity: Definition & Examples

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Quantitative vs. Qualitative Research in Psychology

Anabelle Bernard Fournier is a researcher of sexual and reproductive health at the University of Victoria as well as a freelance writer on various health topics.

Emily is a board-certified science editor who has worked with top digital publishing brands like Voices for Biodiversity, Study.com, GoodTherapy, Vox, and Verywell.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Emily-Swaim-1000-0f3197de18f74329aeffb690a177160c.jpg)

- Key Differences

Quantitative Research Methods

Qualitative research methods.

- How They Relate

In psychology and other social sciences, researchers are faced with an unresolved question: Can we measure concepts like love or racism the same way we can measure temperature or the weight of a star? Social phenomena—things that happen because of and through human behavior—are especially difficult to grasp with typical scientific models.

At a Glance

Psychologists rely on quantitative and quantitative research to better understand human thought and behavior.

- Qualitative research involves collecting and evaluating non-numerical data in order to understand concepts or subjective opinions.

- Quantitative research involves collecting and evaluating numerical data.

This article discusses what qualitative and quantitative research are, how they are different, and how they are used in psychology research.

Qualitative Research vs. Quantitative Research

In order to understand qualitative and quantitative psychology research, it can be helpful to look at the methods that are used and when each type is most appropriate.

Psychologists rely on a few methods to measure behavior, attitudes, and feelings. These include:

- Self-reports , like surveys or questionnaires

- Observation (often used in experiments or fieldwork)

- Implicit attitude tests that measure timing in responding to prompts

Most of these are quantitative methods. The result is a number that can be used to assess differences between groups.

However, most of these methods are static, inflexible (you can't change a question because a participant doesn't understand it), and provide a "what" answer rather than a "why" answer.

Sometimes, researchers are more interested in the "why" and the "how." That's where qualitative methods come in.

Qualitative research is about speaking to people directly and hearing their words. It is grounded in the philosophy that the social world is ultimately unmeasurable, that no measure is truly ever "objective," and that how humans make meaning is just as important as how much they score on a standardized test.

Used to develop theories

Takes a broad, complex approach

Answers "why" and "how" questions

Explores patterns and themes

Used to test theories

Takes a narrow, specific approach

Answers "what" questions

Explores statistical relationships

Quantitative methods have existed ever since people have been able to count things. But it is only with the positivist philosophy of Auguste Comte (which maintains that factual knowledge obtained by observation is trustworthy) that it became a "scientific method."

The scientific method follows this general process. A researcher must:

- Generate a theory or hypothesis (i.e., predict what might happen in an experiment) and determine the variables needed to answer their question

- Develop instruments to measure the phenomenon (such as a survey, a thermometer, etc.)

- Develop experiments to manipulate the variables

- Collect empirical (measured) data

- Analyze data

Quantitative methods are about measuring phenomena, not explaining them.

Quantitative research compares two groups of people. There are all sorts of variables you could measure, and many kinds of experiments to run using quantitative methods.

These comparisons are generally explained using graphs, pie charts, and other visual representations that give the researcher a sense of how the various data points relate to one another.

Basic Assumptions

Quantitative methods assume:

- That the world is measurable

- That humans can observe objectively

- That we can know things for certain about the world from observation

In some fields, these assumptions hold true. Whether you measure the size of the sun 2000 years ago or now, it will always be the same. But when it comes to human behavior, it is not so simple.

As decades of cultural and social research have shown, people behave differently (and even think differently) based on historical context, cultural context, social context, and even identity-based contexts like gender , social class, or sexual orientation .

Therefore, quantitative methods applied to human behavior (as used in psychology and some areas of sociology) should always be rooted in their particular context. In other words: there are no, or very few, human universals.

Statistical information is the primary form of quantitative data used in human and social quantitative research. Statistics provide lots of information about tendencies across large groups of people, but they can never describe every case or every experience. In other words, there are always outliers.

Correlation and Causation

A basic principle of statistics is that correlation is not causation. Researchers can only claim a cause-and-effect relationship under certain conditions:

- The study was a true experiment.

- The independent variable can be manipulated (for example, researchers cannot manipulate gender, but they can change the primer a study subject sees, such as a picture of nature or of a building).

- The dependent variable can be measured through a ratio or a scale.

So when you read a report that "gender was linked to" something (like a behavior or an attitude), remember that gender is NOT a cause of the behavior or attitude. There is an apparent relationship, but the true cause of the difference is hidden.

Pitfalls of Quantitative Research

Quantitative methods are one way to approach the measurement and understanding of human and social phenomena. But what's missing from this picture?

As noted above, statistics do not tell us about personal, individual experiences and meanings. While surveys can give a general idea, respondents have to choose between only a few responses. This can make it difficult to understand the subtleties of different experiences.

Quantitative methods can be helpful when making objective comparisons between groups or when looking for relationships between variables. They can be analyzed statistically, which can be helpful when looking for patterns and relationships.

Qualitative data are not made out of numbers but rather of descriptions, metaphors, symbols, quotes, analysis, concepts, and characteristics. This approach uses interviews, written texts, art, photos, and other materials to make sense of human experiences and to understand what these experiences mean to people.

While quantitative methods ask "what" and "how much," qualitative methods ask "why" and "how."

Qualitative methods are about describing and analyzing phenomena from a human perspective. There are many different philosophical views on qualitative methods, but in general, they agree that some questions are too complex or impossible to answer with standardized instruments.

These methods also accept that it is impossible to be completely objective in observing phenomena. Researchers have their own thoughts, attitudes, experiences, and beliefs, and these always color how people interpret results.

Qualitative Approaches

There are many different approaches to qualitative research, with their own philosophical bases. Different approaches are best for different kinds of projects. For example:

- Case studies and narrative studies are best for single individuals. These involve studying every aspect of a person's life in great depth.

- Phenomenology aims to explain experiences. This type of work aims to describe and explore different events as they are consciously and subjectively experienced.

- Grounded theory develops models and describes processes. This approach allows researchers to construct a theory based on data that is collected, analyzed, and compared to reach new discoveries.

- Ethnography describes cultural groups. In this approach, researchers immerse themselves in a community or group in order to observe behavior.

Qualitative researchers must be aware of several different methods and know each thoroughly enough to produce valuable research.

Some researchers specialize in a single method, but others specialize in a topic or content area and use many different methods to explore the topic, providing different information and a variety of points of view.

There is not a single model or method that can be used for every qualitative project. Depending on the research question, the people participating, and the kind of information they want to produce, researchers will choose the appropriate approach.

Interpretation

Qualitative research does not look into causal relationships between variables, but rather into themes, values, interpretations, and meanings. As a rule, then, qualitative research is not generalizable (cannot be applied to people outside the research participants).

The insights gained from qualitative research can extend to other groups with proper attention to specific historical and social contexts.

Relationship Between Qualitative and Quantitative Research

It might sound like quantitative and qualitative research do not play well together. They have different philosophies, different data, and different outputs. However, this could not be further from the truth.

These two general methods complement each other. By using both, researchers can gain a fuller, more comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon.

For example, a psychologist wanting to develop a new survey instrument about sexuality might and ask a few dozen people questions about their sexual experiences (this is qualitative research). This gives the researcher some information to begin developing questions for their survey (which is a quantitative method).

After the survey, the same or other researchers might want to dig deeper into issues brought up by its data. Follow-up questions like "how does it feel when...?" or "what does this mean to you?" or "how did you experience this?" can only be answered by qualitative research.

By using both quantitative and qualitative data, researchers have a more holistic, well-rounded understanding of a particular topic or phenomenon.

Qualitative and quantitative methods both play an important role in psychology. Where quantitative methods can help answer questions about what is happening in a group and to what degree, qualitative methods can dig deeper into the reasons behind why it is happening. By using both strategies, psychology researchers can learn more about human thought and behavior.

Gough B, Madill A. Subjectivity in psychological science: From problem to prospect . Psychol Methods . 2012;17(3):374-384. doi:10.1037/a0029313

Pearce T. “Science organized”: Positivism and the metaphysical club, 1865–1875 . J Hist Ideas . 2015;76(3):441-465.

Adams G. Context in person, person in context: A cultural psychology approach to social-personality psychology . In: Deaux K, Snyder M, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology . Oxford University Press; 2012:182-208.

Brady HE. Causation and explanation in social science . In: Goodin RE, ed. The Oxford Handbook of Political Science. Oxford University Press; 2011. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199604456.013.0049

Chun Tie Y, Birks M, Francis K. Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers . SAGE Open Med . 2019;7:2050312118822927. doi:10.1177/2050312118822927

Reeves S, Peller J, Goldman J, Kitto S. Ethnography in qualitative educational research: AMEE Guide No. 80 . Medical Teacher . 2013;35(8):e1365-e1379. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2013.804977

Salkind NJ, ed. Encyclopedia of Research Design . Sage Publishing.

Shaughnessy JJ, Zechmeister EB, Zechmeister JS. Research Methods in Psychology . McGraw Hill Education.

By Anabelle Bernard Fournier Anabelle Bernard Fournier is a researcher of sexual and reproductive health at the University of Victoria as well as a freelance writer on various health topics.

Reference management. Clean and simple.

Qualitative vs. quantitative research - what’s the difference?

What is quantitative research?

What is quantitative research used for, how to collect data for quantitative research, what is qualitative research, what is qualitative research used for, how to collect data for qualitative research, when to use which approach, how to analyze qualitative and quantitative research, analyzing quantitative data, analyzing qualitative data, differences between qualitative and quantitative research, frequently asked questions about qualitative vs. quantitative research, related articles.

Both qualitative and quantitative research are valid and effective approaches to study a particular subject. However, it is important to know that these research approaches serve different purposes and provide different results. This guide will help illustrate quantitative and qualitative research, what they are used for, and the difference between them.

Quantitative research focuses on collecting numerical data and using it to measure variables. As such, quantitative research and data are typically expressed in numbers and graphs. Moreover, this type of research is structured and statistical and the returned results are objective.

The simplest way to describe quantitative research is that it answers the questions " what " or " how much ".

To illustrate what quantitative research is used for, let’s look at a simple example. Let’s assume you want to research the reading habits of a specific part of a population.

With this research, you would like to establish what they read. In other words, do they read fiction, non-fiction, magazines, blogs, and so on? Also, you want to establish what they read about. For example, if they read fiction, is it thrillers, romance novels, or period dramas?

With quantitative research, you can gather concrete data about these reading habits. Your research will then, for example, show that 40% of the audience reads fiction and, of that 40%, 60% prefer romance novels.

In other studies and research projects, quantitative research will work in much the same way. That is, you use it to quantify variables, opinions, behaviors, and more.

Now that we've seen what quantitative research is and what it's used for, let's look at how you'll collect data for it. Because quantitative research is structured and statistical, its data collection methods focus on collecting numerical data.

Some methods to collect this data include:

- Surveys . Surveys are one of the most popular and easiest ways to collect quantitative data. These can include anything from online surveys to paper surveys. It’s important to remember that, to collect quantitative data, you won’t be able to ask open-ended questions.

- Interviews . As is the case with qualitative data, you’ll be able to use interviews to collect quantitative data with the proviso that the data will not be based on open-ended questions.

- Observations . You’ll also be able to use observations to collect quantitative data. However, here you’ll need to make observations in an environment where variables can’t be controlled.

- Website interceptors . With website interceptors, you’ll be able to get real-time insights into a specific product, service, or subject. In most cases, these interceptors take the form of surveys displayed on websites or invitations on the website to complete the survey.

- Longitudinal studies . With these studies, you’ll gather data on the same variables over specified time periods. Longitudinal studies are often used in medical sciences and include, for instance, diet studies. It’s important to remember that, for the results to be reliable, you’ll have to collect data from the same subjects.

- Online polls . Similar to website interceptors, online polls allow you to gather data from websites or social media platforms. These polls are short with only a few options and can give you valuable insights into a very specific question or topic.

- Experiments . With experiments, you’ll manipulate some variables (your independent variables) and gather data on causal relationships between others (your dependent variables). You’ll then measure what effect the manipulation of the independent variables has on the dependent variables.

Qualitative research focuses on collecting and analyzing non-numerical data. As such, it's typically unstructured and non-statistical. The main aim of qualitative research is to get a better understanding and insights into concepts, topics, and subjects.

The easiest way to describe qualitative research is that it answers the question " why ".

Considering that qualitative research aims to provide more profound insights and understanding into specific subjects, we’ll use our example mentioned earlier to explain what qualitative research is used for.

Based on this example, you’ve now established that 40% of the population reads fiction. You’ve probably also discovered in what proportion the population consumes other reading materials.

Qualitative research will now enable you to learn the reasons for these reading habits. For example, it will show you why 40% of the readers prefer fiction, while, for instance, only 10% prefer thrillers. It thus gives you an understanding of your participants’ behaviors and actions.

We've now recapped what qualitative research is and what it's used for. Let's now consider some methods to collect data for this type of research.

Some of these data collection methods include:

- Interviews . These include one-on-one interviews with respondents where you ask open-ended questions. You’ll then record the answers from every respondent and analyze these answers later.

- Open-ended survey questions . Open-ended survey questions give you insights into why respondents feel the way they do about a particular aspect.

- Focus groups . Focus groups allow you to have conversations with small groups of people and record their opinions and views about a specific topic.

- Observations . Observations like ethnography require that you participate in a specific organization or group in order to record their routines and interactions. This will, for instance, be the case where you want to establish how customers use a product in real-life scenarios.

- Literature reviews . With literature reviews, you’ll analyze the published works of other authors to analyze the prevailing view regarding a specific subject.

- Diary studies . Diary studies allow you to collect data about peoples’ habits, activities, and experiences over time. This will, for example, show you how customers use a product, when they use it, and what motivates them.

Now, the immediate question is: When should you use qualitative research, and when should you use quantitative research? As mentioned earlier, in its simplest form:

- Quantitative research allows you to confirm or test a hypothesis or theory or quantify a specific problem or quality.

- Qualitative research allows you to understand concepts or experiences.

Let's look at how you'll use these approaches in a research project a bit closer:

- Formulating a hypothesis . As mentioned earlier, qualitative research gives you a deeper understanding of a topic. Apart from learning more profound insights about your research findings, you can also use it to formulate a hypothesis when you start your research.

- Confirming a hypothesis . Once you’ve formulated a hypothesis, you can test it with quantitative research. As mentioned, you can also use it to quantify trends and behavior.

- Finding general answers . Quantitative research can help you answer broad questions. This is because it uses a larger sample size and thus makes it easier to gather simple binary or numeric data on a specific subject.

- Getting a deeper understanding . Once you have the broad answers mentioned above, qualitative research will help you find reasons for these answers. In other words, quantitative research shows you the motives behind actions or behaviors.

Considering the above, why not consider a mixed approach ? You certainly can because these approaches are not mutually exclusive. In other words, using one does not necessarily exclude the other. Moreover, both these approaches are useful for different reasons.

This means you could use both approaches in one project to achieve different goals. For example, you could use qualitative to formulate a hypothesis. Once formulated, quantitative research will allow you to confirm the hypothesis.

So, to answer the initial question, the approach you use is up to you. However, when deciding on the right approach, you should consider the specific research project, the data you'll gather, and what you want to achieve.

No matter what approach you choose, you should design your research in such a way that it delivers results that are objective, reliable, and valid.

Both these research approaches are based on data. Once you have this data, however, you need to analyze it to answer your research questions. The method to do this depends on the research approach you use.

To analyze quantitative data, you'll need to use mathematical or statistical analysis. This can involve anything from calculating simple averages to applying complex and advanced methods to calculate the statistical significance of the results. No matter what analysis methods you use, it will enable you to spot trends and patterns in your data.

Considering the above, you can use tools, applications, and programming languages like R to calculate:

- The average of a set of numbers . This could, for instance, be the case where you calculate the average scores students obtained in a test or the average time people spend on a website.

- The frequency of a specific response . This will be the case where you, for example, use open-ended survey questions during qualitative analysis. You could then calculate the frequency of a specific response for deeper insights.

- Any correlation between different variables . Through mathematical analysis, you can calculate whether two or more variables are directly or indirectly correlated. In turn, this could help you identify trends in the data.

- The statistical significance of your results . By analyzing the data and calculating the statistical significance of the results, you'll be able to see whether certain occurrences happen randomly or because of specific factors.

Analyzing qualitative data is more complex than quantitative data. This is simply because it's not based on numerical values but rather text, images, video, and the like. As such, you won't be able to use mathematical analysis to analyze and interpret your results.

Because of this, it relies on a more interpretive analysis style and a strict analytical framework to analyze data and extract insights from it.

Some of the most common ways to analyze qualitative data include:

- Qualitative content analysis . In a content analysis, you'll analyze the language used in a specific piece of text. This allows you to understand the intentions of the author, who the audience is, and find patterns and correlations in how different concepts are communicated. A major benefit of this approach is that it follows a systematic and transparent process that other researchers will be able to replicate. As such, your research will produce highly reliable results. Keep in mind, however, that content analysis can be time-intensive and difficult to automate. ➡️ Learn how to do a content analysis in the guide.

- Thematic analysis . In a thematic analysis, you'll analyze data with a view of extracting themes, topics, and patterns in the data. Although thematic analysis can encompass a range of diverse approaches, it's usually used to analyze a collection of texts like survey responses, focus group discussions, or transcriptions of interviews. One of the main benefits of thematic analysis is that it's flexible in its approach. However, in some cases, thematic analysis can be highly subjective, which, in turn, impacts the reliability of the results. ➡️ Learn how to do a thematic analysis in this guide.

- Discourse analysis . In a discourse analysis, you'll analyze written or spoken language to understand how language is used in real-life social situations. As such, you'll be able to determine how meaning is given to language in different contexts. This is an especially effective approach if you want to gain a deeper understanding of different social groups and how they communicate with each other. As such, it's commonly used in humanities and social science disciplines.

We’ve now given a broad overview of both qualitative and quantitative research. Based on this, we can summarize the differences between these two approaches as follows:

Qualitative research focuses on collecting and analyzing non-numerical data. As such, it's typically unstructured and non-statistical. The main aim of qualitative research is to get a better understanding and insights into concepts, topics, and subjects. Quantitative research focuses on collecting numerical data and using it to measure variables. As such, quantitative research and data are typically expressed in numbers and graphs. Moreover, this type of research is structured and statistical and the returned results are objective.

3 examples of qualitative research would be:

- Interviews . These include one-on-one interviews with respondents with open-ended questions. You’ll then record the answers and analyze them later.

- Observations . Observations require that you participate in a specific organization or group in order to record their routines and interactions.

3 examples of quantitative research include:

- Surveys . Surveys are one of the most popular and easiest ways to collect quantitative data. To collect quantitative data, you won’t be able to ask open-ended questions.

- Longitudinal studies . With these studies, you’ll gather data on the same variables over specified time periods. Longitudinal studies are often used in medical sciences.

The main purpose of qualitative research is to get a better understanding and insights into concepts, topics, and subjects. The easiest way to describe qualitative research is that it answers the question " why ".

The purpose of quantitative research is to collect numerical data and use it to measure variables. As such, quantitative research and data are typically expressed in numbers and graphs. The simplest way to describe quantitative research is that it answers the questions " what " or " how much ".

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Qualitative vs Quantitative Research | Examples & Methods

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research | Examples & Methods

Published on 4 April 2022 by Raimo Streefkerk . Revised on 8 May 2023.

When collecting and analysing data, quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings. Both are important for gaining different kinds of knowledge.

Common quantitative methods include experiments, observations recorded as numbers, and surveys with closed-ended questions. Qualitative research Qualitative research is expressed in words . It is used to understand concepts, thoughts or experiences. This type of research enables you to gather in-depth insights on topics that are not well understood.

Table of contents

The differences between quantitative and qualitative research, data collection methods, when to use qualitative vs quantitative research, how to analyse qualitative and quantitative data, frequently asked questions about qualitative and quantitative research.

Quantitative and qualitative research use different research methods to collect and analyse data, and they allow you to answer different kinds of research questions.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Quantitative and qualitative data can be collected using various methods. It is important to use a data collection method that will help answer your research question(s).

Many data collection methods can be either qualitative or quantitative. For example, in surveys, observations or case studies , your data can be represented as numbers (e.g. using rating scales or counting frequencies) or as words (e.g. with open-ended questions or descriptions of what you observe).

However, some methods are more commonly used in one type or the other.

Quantitative data collection methods

- Surveys : List of closed or multiple choice questions that is distributed to a sample (online, in person, or over the phone).

- Experiments : Situation in which variables are controlled and manipulated to establish cause-and-effect relationships.

- Observations: Observing subjects in a natural environment where variables can’t be controlled.

Qualitative data collection methods

- Interviews : Asking open-ended questions verbally to respondents.

- Focus groups: Discussion among a group of people about a topic to gather opinions that can be used for further research.

- Ethnography : Participating in a community or organisation for an extended period of time to closely observe culture and behavior.

- Literature review : Survey of published works by other authors.

A rule of thumb for deciding whether to use qualitative or quantitative data is:

- Use quantitative research if you want to confirm or test something (a theory or hypothesis)

- Use qualitative research if you want to understand something (concepts, thoughts, experiences)

For most research topics you can choose a qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods approach . Which type you choose depends on, among other things, whether you’re taking an inductive vs deductive research approach ; your research question(s) ; whether you’re doing experimental , correlational , or descriptive research ; and practical considerations such as time, money, availability of data, and access to respondents.

Quantitative research approach

You survey 300 students at your university and ask them questions such as: ‘on a scale from 1-5, how satisfied are your with your professors?’

You can perform statistical analysis on the data and draw conclusions such as: ‘on average students rated their professors 4.4’.

Qualitative research approach

You conduct in-depth interviews with 15 students and ask them open-ended questions such as: ‘How satisfied are you with your studies?’, ‘What is the most positive aspect of your study program?’ and ‘What can be done to improve the study program?’

Based on the answers you get you can ask follow-up questions to clarify things. You transcribe all interviews using transcription software and try to find commonalities and patterns.

Mixed methods approach

You conduct interviews to find out how satisfied students are with their studies. Through open-ended questions you learn things you never thought about before and gain new insights. Later, you use a survey to test these insights on a larger scale.

It’s also possible to start with a survey to find out the overall trends, followed by interviews to better understand the reasons behind the trends.

Qualitative or quantitative data by itself can’t prove or demonstrate anything, but has to be analysed to show its meaning in relation to the research questions. The method of analysis differs for each type of data.

Analysing quantitative data

Quantitative data is based on numbers. Simple maths or more advanced statistical analysis is used to discover commonalities or patterns in the data. The results are often reported in graphs and tables.

Applications such as Excel, SPSS, or R can be used to calculate things like:

- Average scores

- The number of times a particular answer was given

- The correlation or causation between two or more variables

- The reliability and validity of the results

Analysing qualitative data

Qualitative data is more difficult to analyse than quantitative data. It consists of text, images or videos instead of numbers.

Some common approaches to analysing qualitative data include:

- Qualitative content analysis : Tracking the occurrence, position and meaning of words or phrases

- Thematic analysis : Closely examining the data to identify the main themes and patterns

- Discourse analysis : Studying how communication works in social contexts

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to test a hypothesis by systematically collecting and analysing data, while qualitative methods allow you to explore ideas and experiences in depth.

In mixed methods research , you use both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis methods to answer your research question .

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organisations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organise your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Streefkerk, R. (2023, May 08). Qualitative vs Quantitative Research | Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved 3 June 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/quantitative-qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Raimo Streefkerk

- Translators

- Graphic Designers

Please enter the email address you used for your account. Your sign in information will be sent to your email address after it has been verified.

Qualitative and Quantitative Research: Differences and Similarities

Qualitative research and quantitative research are two complementary approaches for understanding the world around us.

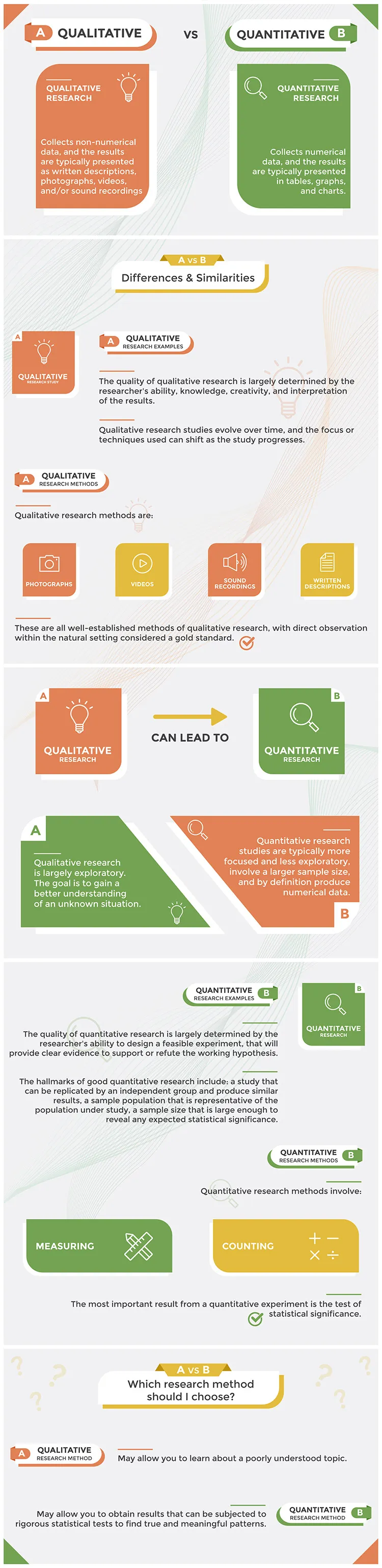

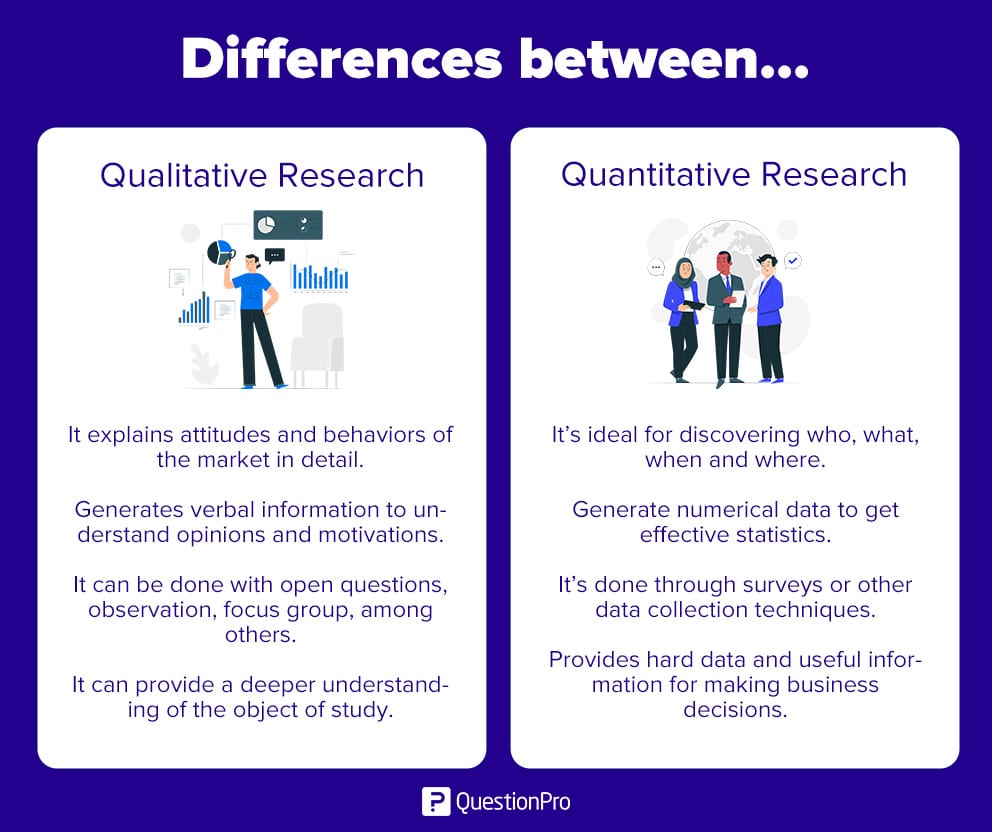

Qualitative research collects non-numerical data , and the results are typically presented as written descriptions, photographs, videos, and/or sound recordings.

In contrast, quantitative research collects numerical data , and the results are typically presented in tables, graphs, and charts.

Debates about whether to use qualitative or quantitative research methods are common in the social sciences (i.e. anthropology, archaeology, economics, geography, history, law, linguistics, politics, psychology, sociology), which aim to understand a broad range of human conditions. Qualitative observations may be used to gain an understanding of unique situations, which may lead to quantitative research that aims to find commonalities.

Within the natural and physical sciences (i.e. physics, chemistry, geology, biology), qualitative observations often lead to a plethora of quantitative studies. For example, unusual observations through a microscope or telescope can immediately lead to counting and measuring. In other situations, meaningful numbers cannot immediately be obtained, and the qualitative research must stand on its own (e.g. The patient presented with an abnormally enlarged spleen (Figure 1), and complained of pain in the left shoulder.)

For both qualitative and quantitative research, the researcher's assumptions shape the direction of the study and thereby influence the results that can be obtained. Let's consider some prominent examples of qualitative and quantitative research, and how these two methods can complement each other.

Qualitative research example

In 1960, Jane Goodall started her decades-long study of chimpanzees in the wild at Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania. Her work is an example of qualitative research that has fundamentally changed our understanding of non-human primates, and has influenced our understanding of other animals, their abilities, and their social interactions.

Dr. Goodall was by no means the first person to study non-human primates, but she took a highly unusual approach in her research. For example, she named individual chimpanzees instead of numbering them, and used terms such as "childhood", "adolescence", "motivation", "excitement", and "mood". She also described the distinct "personalities" of individual chimpanzees. Dr. Goodall was heavily criticized for describing chimpanzees in ways that are regularly used to describe humans, which perfectly illustrates how the assumptions of the researcher can heavily influence their work.

The quality of qualitative research is largely determined by the researcher's ability, knowledge, creativity, and interpretation of the results. One of the hallmarks of good qualitative research is that nothing is predefined or taken for granted, and that the study subjects teach the researcher about their lives. As a result, qualitative research studies evolve over time, and the focus or techniques used can shift as the study progresses.

Qualitative research methods

Dr. Goodall immersed herself in the chimpanzees' natural surroundings, and used direct observation to learn about their daily life. She used photographs, videos, sound recordings, and written descriptions to present her data. These are all well-established methods of qualitative research, with direct observation within the natural setting considered a gold standard. These methods are time-intensive for the researcher (and therefore monetarily expensive) and limit the number of individuals that can be studied at one time.

When studying humans, a wider variety of research methods are available to understand how people perceive and navigate their world—past or present. These techniques include: in-depth interviews (e.g. Can you discuss your experience of growing up in the Deep South in the 1950s?), open-ended survey questions (e.g. What do you enjoy most about being part of the Church of Latter Day Saints?), focus group discussions, researcher participation (e.g. in military training), review of written documents (e.g. social media accounts, diaries, school records, etc), and analysis of cultural records (e.g. anything left behind including trash, clothing, buildings, etc).

Qualitative research can lead to quantitative research

Qualitative research is largely exploratory. The goal is to gain a better understanding of an unknown situation. Qualitative research in humans may lead to a better understanding of underlying reasons, opinions, motivations, experiences, etc. The information generated through qualitative research can provide new hypotheses to test through quantitative research. Quantitative research studies are typically more focused and less exploratory, involve a larger sample size, and by definition produce numerical data.

Dr. Goodall's qualitative research clearly established periods of childhood and adolescence in chimpanzees. Quantitative studies could better characterize these time periods, for example by recording the amount of time individual chimpanzees spend with their mothers, with peers, or alone each day during childhood compared to adolescence.

For studies involving humans, quantitative data might be collected through a questionnaire with a limited number of answers (e.g. If you were being bullied, what is the likelihood that you would tell at least one parent? A) Very likely, B) Somewhat likely, C) Somewhat unlikely, D) Unlikely).

Quantitative research example

One of the most influential examples of quantitative research began with a simple qualitative observation: Some peas are round, and other peas are wrinkled. Gregor Mendel was not the first to make this observation, but he was the first to carry out rigorous quantitative experiments to better understand this characteristic of garden peas.

As described in his 1865 research paper, Mendel carried out carefully controlled genetic crosses and counted thousands of resulting peas. He discovered that the ratio of round peas to wrinkled peas matched the ratio expected if pea shape were determined by two copies of a gene for pea shape, one inherited from each parent. These experiments and calculations became the foundation of modern genetics, and Mendel's ratios became the default hypothesis for experiments involving thousands of different genes in hundreds of different organisms.

The quality of quantitative research is largely determined by the researcher's ability to design a feasible experiment, that will provide clear evidence to support or refute the working hypothesis. The hallmarks of good quantitative research include: a study that can be replicated by an independent group and produce similar results, a sample population that is representative of the population under study, a sample size that is large enough to reveal any expected statistical significance.

Quantitative research methods

The basic methods of quantitative research involve measuring or counting things (size, weight, distance, offspring, light intensity, participants, number of times a specific phrase is used, etc). In the social sciences especially, responses are often be split into somewhat arbitrary categories (e.g. How much time do you spend on social media during a typical weekday? A) 0-15 min, B) 15-30 min, C) 30-60 min, D) 1-2 hrs, E) more than 2 hrs).

These quantitative data can be displayed in a table, graph, or chart, and grouped in ways that highlight patterns and relationships. The quantitative data should also be subjected to mathematical and statistical analysis. To reveal overall trends, the average (or most common survey answer) and standard deviation can be determined for different groups (e.g. with treatment A and without treatment B).

Typically, the most important result from a quantitative experiment is the test of statistical significance. There are many different methods for determining statistical significance (e.g. t-test, chi square test, ANOVA, etc.), and the appropriate method will depend on the specific experiment.

Statistical significance provides an answer to the question: What is the probably that the difference observed between two groups is due to chance alone, and the two groups are actually the same? For example, your initial results might show that 32% of Friday grocery shoppers buy alcohol, while only 16% of Monday grocery shoppers buy alcohol. If this result reflects a true difference between Friday shoppers and Monday shoppers, grocery store managers might want to offer Friday specials to increase sales.

After the appropriate statistical test is conducted (which incorporates sample size and other variables), the probability that the observed difference is due to chance alone might be more than 5%, or less than 5%. If the probability is less than 5%, the convention is that the result is considered statistically significant. (The researcher is also likely to cheer and have at least a small celebration.) Otherwise, the result is considered statistically insignificant. (If the value is close to 5%, the researcher may try to group the data in different ways to achieve statistical significance. For example, by comparing alcohol sales after 5pm on Friday and Monday.) While it is important to reveal differences that may not be immediately obvious, the desire to manipulate information until it becomes statistically significant can also contribute to bias in research.

So how often do results from two groups that are actually the same give a probability of less than 5%? A bit less than 5% of the time (by definition). This is one of the reasons why it is so important that quantitative research can be replicated by different groups.

Which research method should I choose?

Choose the research methods that will allow you to produce the best results for a meaningful question, while acknowledging any unknowns and controlling for any bias. In many situations, this will involve a mixed methods approach. Qualitative research may allow you to learn about a poorly understood topic, and then quantitative research may allow you to obtain results that can be subjected to rigorous statistical tests to find true and meaningful patterns. Many different approaches are required to understand the complex world around us.

- Academic Writing Advice

- All Blog Posts

- Writing Advice

- Admissions Writing Advice

- Book Writing Advice

- Short Story Advice

- Employment Writing Advice

- Business Writing Advice

- Web Content Advice

- Article Writing Advice

- Magazine Writing Advice

- Grammar Advice

- Dialect Advice

- Editing Advice

- Freelance Advice

- Legal Writing Advice

- Poetry Advice

- Graphic Design Advice

- Logo Design Advice

- Translation Advice

- Blog Reviews

- Short Story Award Winners

- Scholarship Winners

Need an academic editor before submitting your work?

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research 101

A plain-language explanation (with examples).

By: Kerryn Warren (PhD, MSc, BSc) | June 2020

So, it’s time to decide what type of research approach you’re going to use – qualitative or quantitative . And, chances are, you want to choose the one that fills you with the least amount of dread. The engineers may be keen on quantitative methods because they loathe interacting with human beings and dealing with the “soft” stuff and are far more comfortable with numbers and algorithms. On the other side, the anthropologists are probably more keen on qualitative methods because they literally have the opposite fears.

However, when justifying your research, “being afraid” is not a good basis for decision making. Your methodology needs to be informed by your research aims and objectives , not your comfort zone. Plus, it’s quite common that the approach you feared (whether qualitative or quantitative) is actually not that big a deal. Research methods can be learnt (usually a lot faster than you think) and software reduces a lot of the complexity of both quantitative and qualitative data analysis. Conversely, choosing the wrong approach and trying to fit a square peg into a round hole is going to create a lot more pain.

In this post, I’ll explain the qualitative vs quantitative choice in straightforward, plain language with loads of examples. This won’t make you an expert in either, but it should give you a good enough “big picture” understanding so that you can make the right methodological decision for your research.

Qualitative vs Quantitative: Overview

- Qualitative analysis 101

- Quantitative analysis 101

- How to choose which one to use

- Data collection and analysis for qualitative and quantitative research

- The pros and cons of both qualitative and quantitative research

- A quick word on mixed methods

Qualitative Research 101: The Basics

The bathwater is hot.

Let us unpack that a bit. What does that sentence mean? And is it useful?

The answer is: well, it depends. If you’re wanting to know the exact temperature of the bath, then you’re out of luck. But, if you’re wanting to know how someone perceives the temperature of the bathwater, then that sentence can tell you quite a bit if you wear your qualitative hat .

Many a husband and wife have never enjoyed a bath together because of their strongly held, relationship-destroying perceptions of water temperature (or, so I’m told). And while divorce rates due to differences in water-temperature perception would belong more comfortably in “quantitative research”, analyses of the inevitable arguments and disagreements around water temperature belong snugly in the domain of “qualitative research”. This is because qualitative research helps you understand people’s perceptions and experiences by systematically coding and analysing the data .

With qualitative research, those heated disagreements (excuse the pun) may be analysed in several ways. From interviews to focus groups to direct observation (ideally outside the bathroom, of course). You, as the researcher, could be interested in how the disagreement unfolds, or the emotive language used in the exchange. You might not even be interested in the words at all, but in the body language of someone who has been forced one too many times into (what they believe) was scalding hot water during what should have been a romantic evening. All of these “softer” aspects can be better understood with qualitative research.

In this way, qualitative research can be incredibly rich and detailed , and is often used as a basis to formulate theories and identify patterns. In other words, it’s great for exploratory research (for example, where your objective is to explore what people think or feel), as opposed to confirmatory research (for example, where your objective is to test a hypothesis). Qualitative research is used to understand human perception , world view and the way we describe our experiences. It’s about exploring and understanding a broad question, often with very few preconceived ideas as to what we may find.

But that’s not the only way to analyse bathwater, of course…

Quantitative Research 101: The Basics

The bathwater is 45 degrees Celsius.

Now, what does this mean? How can this be used?

I was once told by someone to whom I am definitely not married that he takes regular cold showers. As a person who is terrified of anything that isn’t body temperature or above, this seemed outright ludicrous. But this raises a question: what is the perfect temperature for a bath? Or at least, what is the temperature of people’s baths more broadly? (Assuming, of course, that they are bathing in water that is ideal to them). To answer this question, you need to now put on your quantitative hat .

If we were to ask 100 people to measure the temperature of their bathwater over the course of a week, we could get the average temperature for each person. Say, for instance, that Jane averages at around 46.3°C. And Billy averages around 42°C. A couple of people may like the unnatural chill of 30°C on the average weekday. And there will be a few of those striving for the 48°C that is apparently the legal limit in England (now, there’s a useless fact for you).

With a quantitative approach, this data can be analysed in heaps of ways. We could, for example, analyse these numbers to find the average temperature, or look to see how much these temperatures vary. We could see if there are significant differences in ideal water temperature between the sexes, or if there is some relationship between ideal bath water temperature and age! We could pop this information onto colourful, vibrant graphs , and use fancy words like “significant”, “correlation” and “eigenvalues”. The opportunities for nerding out are endless…

In this way, quantitative research often involves coming into your research with some level of understanding or expectation regarding the outcome, usually in the form of a hypothesis that you want to test. For example:

Hypothesis: Men prefer bathing in lower temperature water than women do.

This hypothesis can then be tested using statistical analysis. The data may suggest that the hypothesis is sound, or it may reveal that there are some nuances regarding people’s preferences. For example, men may enjoy a hotter bath on certain days.

So, as you can see, qualitative and quantitative research each have their own purpose and function. They are, quite simply, different tools for different jobs .

Need a helping hand?

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research: Which one should you use?

And here I become annoyingly vague again. The answer: it depends. As I alluded to earlier, your choice of research approach depends on what you’re trying to achieve with your research.

If you want to understand a situation with richness and depth , and you don’t have firm expectations regarding what you might find, you’ll likely adopt a qualitative research approach. In other words, if you’re starting on a clean slate and trying to build up a theory (which might later be tested), qualitative research probably makes sense for you.

On the other hand, if you need to test an already-theorised hypothesis , or want to measure and describe something numerically, a quantitative approach will probably be best. For example, you may want to quantitatively test a theory (or even just a hypothesis) that was developed using qualitative research.

Basically, this means that your research approach should be chosen based on your broader research aims , objectives and research questions . If your research is exploratory and you’re unsure what findings may emerge, qualitative research allows you to have open-ended questions and lets people and subjects speak, in some ways, for themselves. Quantitative questions, on the other hand, will not. They’ll often be pre-categorised, or allow you to insert a numeric response. Anything that requires measurement , using a scale, machine or… a thermometer… is going to need a quantitative method.

Let’s look at an example.

Say you want to ask people about their bath water temperature preferences. There are many ways you can do this, using a survey or a questionnaire – here are 3 potential options:

- How do you feel about your spouse’s bath water temperature preference? (Qualitative. This open-ended question leaves a lot of space so that the respondent can rant in an adequate manner).

- What is your preferred bath water temperature? (This one’s tricky because most people don’t know or won’t have a thermometer, but this is a quantitative question with a directly numerical answer).

- Most people who have commented on your bath water temperature have said the following (choose most relevant): It’s too hot. It’s just right. It’s too cold. (Quantitative, because you can add up the number of people who responded in each way and compare them).

The answers provided can be used in a myriad of ways, but, while quantitative responses are easily summarised through counting or calculations, categorised and visualised, qualitative responses need a lot of thought and are re-packaged in a way that tries not to lose too much meaning.

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research: Data collection and analysis

The approach to collecting and analysing data differs quite a bit between qualitative and quantitative research.

A qualitative research approach often has a small sample size (i.e. a small number of people researched) since each respondent will provide you with pages and pages of information in the form of interview answers or observations. In our water perception analysis, it would be super tedious to watch the arguments of 50 couples unfold in front of us! But 6-10 would be manageable and would likely provide us with interesting insight into the great bathwater debate.

To sum it up, data collection in qualitative research involves relatively small sample sizes but rich and detailed data.

On the other side, quantitative research relies heavily on the ability to gather data from a large sample and use it to explain a far larger population (this is called “generalisability”). In our bathwater analysis, we would need data from hundreds of people for us to be able to make a universal statement (i.e. to generalise), and at least a few dozen to be able to identify a potential pattern. In terms of data collection, we’d probably use a more scalable tool such as an online survey to gather comparatively basic data.

So, compared to qualitative research, data collection for quantitative research involves large sample sizes but relatively basic data.

Both research approaches use analyses that allow you to explain, describe and compare the things that you are interested in. While qualitative research does this through an analysis of words, texts and explanations, quantitative research does this through reducing your data into numerical form or into graphs.

There are dozens of potential analyses which each uses. For example, qualitative analysis might look at the narration (the lamenting story of love lost through irreconcilable water toleration differences), or the content directly (the words of blame, heat and irritation used in an interview). Quantitative analysis may involve simple calculations for averages , or it might involve more sophisticated analysis that assesses the relationships between two or more variables (for example, personality type and likelihood to commit a hot water-induced crime). We discuss the many analysis options other blog posts, so I won’t bore you with the details here.

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research: The pros & cons on both sides

Quantitative and qualitative research fundamentally ask different kinds of questions and often have different broader research intentions. As I said earlier, they are different tools for different jobs – so we can’t really pit them off against each other. Regardless, they still each have their pros and cons.

Let’s start with qualitative “pros”

Qualitative research allows for richer , more insightful (and sometimes unexpected) results. This is often what’s needed when we want to dive deeper into a research question . When we want to find out what and how people are thinking and feeling , qualitative is the tool for the job. It’s also important research when it comes to discovery and exploration when you don’t quite know what you are looking for. Qualitative research adds meat to our understanding of the world and is what you’ll use when trying to develop theories.

Qualitative research can be used to explain previously observed phenomena , providing insights that are outside of the bounds of quantitative research, and explaining what is being or has been previously observed. For example, interviewing someone on their cold-bath-induced rage can help flesh out some of the finer (and often lost) details of a research area. We might, for example, learn that some respondents link their bath time experience to childhood memories where hot water was an out of reach luxury. This is something that would never get picked up using a quantitative approach.

There are also a bunch of practical pros to qualitative research. A small sample size means that the researcher can be more selective about who they are approaching. Linked to this is affordability . Unless you have to fork out huge expenses to observe the hunting strategies of the Hadza in Tanzania, then qualitative research often requires less sophisticated and expensive equipment for data collection and analysis.

Qualitative research also has its “cons”:

A small sample size means that the observations made might not be more broadly applicable. This makes it difficult to repeat a study and get similar results. For instance, what if the people you initially interviewed just happened to be those who are especially passionate about bathwater. What if one of your eight interviews was with someone so enraged by a previous experience of being run a cold bath that she dedicated an entire blog post to using this obscure and ridiculous example?

But sample is only one caveat to this research. A researcher’s bias in analysing the data can have a profound effect on the interpretation of said data. In this way, the researcher themselves can limit their own research. For instance, what if they didn’t think to ask a very important or cornerstone question because of previously held prejudices against the person they are interviewing?

Adding to this, researcher inexperience is an additional limitation . Interviewing and observing are skills honed in over time. If the qualitative researcher is not aware of their own biases and limitations, both in the data collection and analysis phase, this could make their research very difficult to replicate, and the theories or frameworks they use highly problematic.