Are Examinations a Fair Way of Testing Our Knowledge?

Many students dislike exams and children of all ages seem to have a diet of more and more exams that they have to take. Coursework is being discredited as a way of demonstrating knowledge as it is becoming easier to plagiarise or even buy coursework over the internet. This leaves exams as the only obvious choice, but do they accurately & fairly test students’ knowledge?

All the Yes points:

A formal system needs to be in place., this s a student point of view, all the no points:, students can cheat in exams, the right discipline, the fact remains the truth because, flawed tests can defeat a good student, there are too many flaws, examinations do not show if someone has truly acquired certain knowledge., the microscopic and responsive nature of examining does not reflect how we use intelligence and knowledge in the real world., exams test memory more than analysis, creativity, or real understanding., coursework is a much more genuine assessment of a candidate, the pressure attached to a’levels and gcses is huge and causes many problems., as well as causing personal problems, pressure can lead many bright students to under-perform., examination results depend on the opinion of the individual examiner., yes because….

Academic competence and intelligence are not straightforward to measure and no method will fully capture the scope of a student’s ability, but the fact remains that we need at least some formal system, otherwise the academic system will not work. We need divisions between ability levels and the amount of experience and knowledge students actually possess, otherwise students will be in environments unsuited to them and won’t be able to learn properly. There is no other way to divide them than by testing them in a fair and impartial manner. Exams are good at this because they are not vague – they have clear, measurable guidelines.

No because…

Guidelines are neither clear nor measurable. Students are duped into believing their innate abilities and potential are being tested whilst they are largely being tested on test-taking ability, confidence and pushiness. What this system encourages is practicing past papers in the hopes of mastering tests and not the subject. Tests do not encourage the pursuit of knowledge so much as the pursuit of great grades. Education should free the mind not restrict it to guidelines that are NOT transparent (As the pandemic of misunderstood Andagogy(opposite of pedagogy) keeps teachers from spoon-feeding or spelling things out). Intellectual exploration is impeded with constant pulls towards mastering guess work and memorising ‘standard’ methods of answering ‘repeated types’ of questions that were originally set to test a student’s response to unfamiliar problems. Subjective/qualitative papers with essay questions are not as easy to measure as mathematics or other quantitative papers. There are times when different examiners grade the same paper by the same student/pupil very differently. Marks on tests are frequently altered on students’ coercion or a teacher/examiner’s admittance of human error on his/her part. Pushier/convincing students can push examiners/tutors into raising their grades and exercise this talent frequently. Tests simply require students to cram when studying, and after the test is taken, the information studied is almost immediately forgotten, so the purpose of the test in the first place is gone.

So,first we have to consider about our world population…..ipsofacto (infact) our country’s population….that would have answered all your questions…if not so continue reading this passage considering the population and the great competition developed at present because of that population….we have to prove ourself through some efficient method even in order to get a job…..and of course we don’t have any efficient method for that purpose except examination……. lack of examinations may …i’m sorry… will definitely cause some unsuited persons to get unsuited jobs and which ‘ll lead to improper development and will affect the country’s development hence to select the good environment for the students according to their ability examinations are must…and im toooo suffering with those stuffs guysssssssssssss………

The problem with examination for the purpose of proving oursleves or comparing our resulits to others is that exams are not required for such things. take for example someone who is planning to become a doctor or a surgeon. it may be helpfull to exam them and test them to see if they can memorise a medical text book from cover to cover but does this prepare them for the more pratical aspects of being a doctor such as conversing with paitents to name but one. even the aspects which are tested in an exam format (body parts/systems, diseases and injuries) could be made into a more pratical test which invloes more than just writing and memory skills. By making exams the main way of catagorising us we decide that in the real world memory and test taking are more important than the pratical aspects of each profession.

Even though exams are closely monitored and there are severe penalties if they are found cheating, students can still sneak information into exams. Exam papers can even be stolen or forged on their way to and from examination centers. Computers that contain the grades before they are formally released can be hacked into or go wrong on their own. It is more difficult to monitor students who don’t take their exams in the main examination room or at the same date and time as the regular exams, because of disability adjustments or resits, and we can’t do away with these. If exams are supposed to be a way to prevent cheating, they aren’t infallible by any means. I never said the method had to be perfect, I said a system that is being replaced because it is vulnerable to cheating shouldn’t be replaced by another system that is vulnerable to cheating. You wouldn’t replace a faulty computer with another faulty computer.

We are mortal: we are all going to die: does that mean we should all kill ourselves and never attempt to prolong and improve our lives? no it does not The system of testing exists for a purpose, which it may not serve ‘perfectly’ but serves to an extent. Tests can be improved and cheating can be reduced. Tests with certain test-takers cheating, are better than no tests at all. You might as well not sell anything because some people steal. It is unfair that students who do not cheat and vye for a fair assessment of their abilities and standing on a subject, should be deprived of being tested because of a few bad eggs. There is a difference between ‘improvement’ and replacement. Testing/exams can not be replaced the conditions in which they proceed are different for different exam centers and different students as you point out that doesn’t mean testing should be chucked altogether. efforts can be made to make stringent and similar test-taking conditions( a faulty computer can be fixed that won’t stop it from gettting faulty again) for everyone everywhere however to expect perfect results is irrational. It is not tests themselves that allow cheating it is the conditions in which they are conducted. You cannot say that a T.V lying on the road then getting stolen, is responsible for getting robbed. It is the condition(sitting on the road, entirely not the T.V’s fault) that leads to the crime/theft.

Examinations are, at times, good and necessary ways of testing a student’s ability to commit information to memory, to work under pressure and to find out what they know. However, examinations must not become regular. Regular examinations result in students working toward exams and exams only. They do not work in order to learn. Knowledge for the sake of knowledge is rid of in a system where examinations reign supreme. It becomes knowledge for the sake of passing the class, receiving an “A” etc. Whilst coursework may easily be cheated on, it is ridiculous to suggest that the only other way of testing a student’s abilities and knowledge is through examination. Class discussions and debates are, with active class participation, one of the most effective ways of learning and retaining information. Through being forced to better one’s own views and opinions, theories and answers, the student gains a deeper insight into their own arguments, becomes better at discussing their views, and the class benefits from listening to these views and thinking about how the views of their peers compare to those of their own. Through this they can alter their own opinions or form new ones. Class participation is a necessary requirement seeing as how even if one person refuses to engage in the discussion, their own ideas are never put to the test of both the peers and their teacher, and so receive no benefit for their own beliefs, and the class also receives no benefit from that particular student. And this is just one student! Full class participation is an absolute requirement. How do we accurately test students? We test them through what they are best at and what they are happiest with through immediate student and teacher feedback during and after classes. Weekly or monthly the parents/guardians of those students will receive report cards, showing which subjects their son/daughter is best at, and which they need the most help with. It will also be noted which classes are that child’s favourite. Parents and students must also be able to suggest ways in which their classes could be made better, so long as the suggestions are realistic, reasonable and that they contribute to the learning environment in such a way that the students learn more and at no cost to student/teacher and student/student relationships. For example, bullying must not become more common as a result of changes to the class. Examinations should appear annually, but no more than that. If there are discrepancies between one’s examination and one’s school work, then this must be investigated, as it would be within the current system now. However, discrepencies are far less likely within this proposed framework, as all the progress and learning goes on during school hours and under the supervision and encouragement of the teacher. (This does not mean to say that kids should not be assigned homework, but the homework itself would be judged on how well the student can prove that they did it i.e., through class discussions the next day).

Discussions and debates are useless as a measure of your academic performance if you just can’t speak confidently in real time. What do you do in cases where your favorite subject isn’t the subject you perform best in? it might seem obvious that people will perform best in subjects they are enthusiastic in and try the hardest in because they like it, but my grades were almost universally best in subjects i hated – because i tried my hardest to ‘get them over and done with’ so i didn’t have to think about them any more, which people mistook for efficiency, and i would write completely mechanically and impartially about them, which made me look more disciplined, especially when the subject was maths and it mostly was mechanical. the subjects i liked were the ones i was more relaxed in and quite often would assume beforehand that I would do well in, causing me to make less effort. But how can you determine whether someone has absorbed information or attained knowledge and can eloquently reproduce it under pressure whilst being timed, without him or her being tested??

The fact remains the truth because EXAMINATION IS NOT THE TRUE TEST OF KNOWLEDGE . Its every where , Instances where after exams student forget most if not all they’ve learnt during the session all because they were reading only to pass the exams and nothing more . this is becoming more and more common among those who just want to find an easy way out to study where student cram solutions to past questions just to pass the exam…..And the exams has not help in anyway either since its has always been repetition of past questions or modification of past question. I really don’t know what to call this but in most cases the teacher will always want you to give them what they give , what am saying is that they want you to write it the way they taught you in the class, you know, I really don’t know what this thing called examination is ? . I will give you an instance , back then when I was in school ,….we had the subject in physics which was very wide and we did a lot of examples and class work , due to the complexity of the course we had to read both text books and all necessary materials we could lay our hands on ….during the exams the questions where just examples we did in the class , and you wont believe it many student failed . What am I saying ….this thing called examination which test how best you can cram and how lucky you could be ? ….what I mean by that is , there are instances where you will go to an exams and your area of concentration will not even be part of the exams ,…not that you don’t know it or you’ve not read but the aspect of the course where you are good is not on the exams …..so you see there are a lot to this examination of a thing….i think there should be a better way of testing students knowledge about what they’ve learned and how deep they understand it …..and not just making them cram past questions and answers..

“I’ve been making a list of the things they don’t teach you at school. They don’t teach you how to love somebody. They don’t teach you how to be famous. They don’t teach you how to be rich or how to be poor. They don’t teach you how to walk away from someone you don’t love any longer. They don’t teach you how to know what’s going on in someone else’s mind. They don’t teach you what to say to someone who’s dying. They don’t teach you anything worth knowing.” – Neil Gaiman Given all that you’ve said the absence of exams/tests would ipso facto, be an even worse assessment of knowledge, potential and/or ability. Since there is no alternative measure that if it were given the importance given to formal testing would/does not fail in all the areas that exams have failed. It is important to know how people perform under pressure since work (and everything else that exams prepare and assess you for) is generally thought to be very stressing. It’s not just that we have to give exams so that we can pass, but with exams we revise what we read and when we learn all these things they settle in our mind.

I have never been comfortable with a very good grade (an A) or a very bad grade (an F) I may have received as a result of taking a test. Grades on either extreme often leave me wondering if I’ve learned anything at all. One thing I have learned recently, as a result of failing miserably on a test, is that the test itself can be flawed. A little research reveals that the skills required to develop a fair, meaningful and comprehensive test, regardless of the subject matter, are considerable. Imagine for example, a mid-term exam, in this case applied mathematics, with an extremely narrow subject bandwidth, as compared with the overall course material, and limited to essentially three questions, two of which are worth 40 points each with the third worth 20 points. None were multiple choice or matching type questions. Miss just one of the 40 point questions and you get an F! To receive an A required a correct answer on 100% of the material! What does a test like this say, to me or the instructor, about what I’ve really learned in this class? Not much!

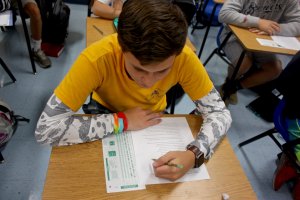

Likes try to take a case in point, of mathematics class which one student takes online versus another who takes in class. Now the student in class may actually be a harder worker, smarter, an overall better student but he is challenged to the fact, that he must take the same exam as the online student, who is able to use his notes, book, online resources. So does the exam treat the student’s fairly? Lets look at another fact of exams, in a generalization most classes consists of 3-4 exams, each exam covering 2-3 chapters, then a compressive final covering all chapters and of course homework. Most classes go by weighted scores, such that your exams consists of 50% of grade, your final 30% of grade, and your homework 20%. Student’s put emphasis on these weighted scores, by creating priorities such that, homework is considered the bottom of the food chain. Why work on homework, when the tests are more important? When the scary realization is that homework is the tool, that provides the best way to create lasting knowledge. How do you get better at a math theory? You constantly use that math theory on dozens of problems over and over again, such as you would find on homework. However on the flip-side on a test, you memorize a theory, use it once, and forget about it. So exams fails to create lasting knowledge, which is the whole point of classes. My final point, doesn’t necessarily point the flaw in examination but the flaw in the examineer. We’ve all had times, where a teacher would vaguely touch on subject, yet the subject becomes a big part of the test. Some teachers fail to recognize the flaws in their teaching method, as most teaching methods consists of trying to create ever lasting knowledge which takes a long time, and repetition. When tests mock the fact of this by exploiting student’s who are good at the skill of learn and forget, studying whats going to be on the test, rather than knowledge provided by the teacher, which sometimes isn’t even on the exam. To finish, I’d like to suggest alternatives tests that would better replace traditional exams. The best I feel would be oral exams, a one on one talk with the examiner as he goes through different questions, would eliminate exams problems that have weird worded question or ask vague questions, and then the examiner could full evaluate the person knowledge and ability use set knowledge in “test” sort of situation. Take home tests, are another, but cheating is an increased chance, so an implement of different tests would have to be used. The student benefits from this, for being forced to research again the knowledge that he or she has probably lost over the course. Which I think should be the true reason for a final test, a refresher on what you’ve learned. Also the final suggestion would be to lose the weighted score of tests, maybe making homework 50% of grade, 3-4 tests 7-10%, and the final test 20%, that way it gets rid of the one thought knowledge test. Because even a student who is copying answers, as long as he copies the method, he is learning something, such the same as a kid who copies theories from a book. Writing or retyping is effective way to create knowledge.

Candidates can score high on an examination by revising hard beforehand, only to forget it immediately afterwards. Surprise examinations are perhaps more effective in showing the candidate’s knowledge.

A surprise exam still sounds like an exam to me. One major question is are there any other ways of testing our knowledge that do not invole some kind of examination? You have practical testing or testing while on the job but that is really just an exam by another name.

In the world of work, in the world of relationships, in the world of family life, relaxation, further academic study, in all these worlds, one requires the ability not just to learn facts and hold understanding of certain intellectual systems in your head, but to make decisions, come up with ideas about how you want to proceed in using any of these things. You need a much more interactive relationship with the world than a simple ‘it exists and I know certain things about it’. Perhaps this aspect of growing up is best provided elsewhere, such as the playground, where certain survival instincts and behavioural tactics are learned or beaten into you, but it seems incredible to me that the educational system couldn’t go some way towards alleviating the disparity between how we are examined in the exam hall and how we come to use what we have learned in wider life.

Exams test memory more than analysis, creativity, or real understanding. If you have a good memory you can get away with doing very little work throughout the course and still get very good grades.

Things such as open book exams, viva voces, and questions which ask you to evaluate information are not testing merely memory, but your ability to apply your knowledge.

Coursework is a much more genuine assessment of a candidate because it takes into account research, understanding of the issues and ability to express oneself, not just ability to answer a question in a very limited period of time.

Coursework is valuable but should be used in conjunction with exams. A student might answer a question very well given time and help from teachers, family and textbooks, but then be unable to apply what they have learned to another question coming from a different angle.

The pressure attached to A’levels and GCSEs is huge and causes many problems. Some students have breakdowns and, in extreme cases, attempt suicide because they cannot handle the pressure, especially with university places relying on grades.

Coursework can involve a lot of pressure as well, especially with the meeting of deadlines. Schools should, and do, teach pupils about relaxation and stress-management for both exams and coursework.

As well as causing personal problems, pressure can lead many bright students to under-perform. Exams test your ability to keep your cool more than they test your intelligence.

Pressure is a fact of life and children must be prepared for it. Pressure only increases at university and in the workplace and we must teach children how to perform well in these conditions rather than protect them from them.

Examination results depend on the opinion of the individual examiner. The same paper marked by two different examiners could get completely different results. This is exacerbated by the short time that examiners spend marking a paper.

Coursework must also be marked by individuals, so the same criticism applies. It is not significant however, as moderation and examiners meetings ensure that papers are marked to the same standards.

Who is the author of this site.

From Kindergarten we have learned that completing a task correctly might get us a gold star, or our names on the “honor list’. We have been taught or trained that if we are able to demonstrate back information we will be rewarded. Earlier in childhood education with the gold star, and later in adulthood with the “good” job. So, in essence, examinations are just a way of testing how good we are at following instructions to get that reward. Exams do not give an accurate summary of knowledge application

The answer is simple. Exams are not a fair way of testing your knowledge. Grades only tell what you did in the paper. Exams can never be flawless and its best to judge students based on their overall skills seen throughout a period of two to three years instead of forcing them to work under a very specific paper pattern. Exams are little more than modern slavery.

The fact is that if you are always tested, you’ll get nervous and anxious as soon as you’re given work to do and devellop medical conditions after a while

students should not only be tested on how well they do in their exams but also they should be marked on presentations and projects as it gives them the opportunity to explain in their own words what they have learnt and then apply it.:)

Honestly, I think this is a very good system, each subject should have a balance of presentations and exams. But I should also add this, there should also be an option for students who are dissatisfied with their results to present their understanding of their subject once again to see whether they actually understood the concepts but didn’t do well because of the system. No system is perfect, which is why I feel this is a good idea.

a student who works hard, is fully antentive in class, solving problems independently and who has a regular study schedule will not face any problem in answering the question paper. It does not matter too much that wheather the student is poor or not it depends on the students hard work. Exams identify in which field will the student exel and this simplify the career choice. Only the students who want to exel in life will work hard enough

I disagree. There are times when the teacher fails to teach the proper format and how to answer questions. A person who understands the concepts and know how to apply them very well is useless when in a rigid formal system that discourages creativity and exchanges self expression of their good understanding of the course with formal rigid structures. I don’t fail, but I have done badly in exams with high formal structures in university, one of the few assignnrs I did well was one that had absolutely no structure, I was free to express my understanding of the subject.

The way I see it, as long as the student is able To express his understanding in a clear and concise manner, it does not matter if it does not follow the exact format of the written examination.

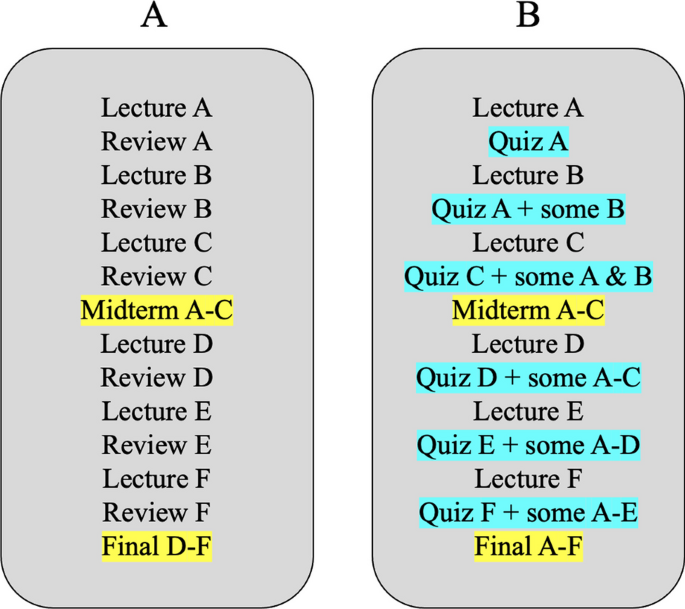

test taking skills are also needed for good scores. If we don’t know test taking skills, then we can’t get a high score, so it is not a good way to test our knowledge. what if a student is too poor to learn these skills? Then they can’t get a high score even though they study harder than students who know a lot of testing skills. it is not his/her fault that their family is poor.

Therefore, examinations are not a fair way of testing our knowledge.

Are exams a true test of one?s ability?

15 mai 2007

Commentaire(s)

Partager cet article

Facebook X LinkedIn WhatsApp

Indeed examinations are regarded by the teachers and other prominent intellectuals as a test of merit .Students prepare for the examinations, days and months in advance. The day of the examination is always awaited with a mixed feeling. There is a fear of facing a tough paper and there is also a sense of relief to know that, once the papers are over, there can be enough time to play and enjoy. Examinations are a bug-bear. They are like electric shocks for most students.

Children have all sorts of nightmares before the preparation of an examination. They priviledge cramming. Unintelligent cramming leads to stunting of the thinking power. They are a farce. The examiners themselves are not sure how to mark the papers.The outstanding advantage of examinations is that the teacher and student tend to be industrious. Examinations inspire them to work hard and score maximum marks in each subject. The teacher and students consider examinations as their only goal. They even compete with other classes.

This means that without examinations, teachers and students would tend to become idle. After the result, the meritorious student is easily known by the teacher or principal. Students are not to be found in cinema houses, restaurants and other places of entertainment during examination days. If there were no examinations, the merits of various students could not be judged, nor would the majority of students take any interest as it is only the fear of examinations that makes students work. They know that if they keep on neglecting books, they will be exposed on examination days.

Now do examinations really test an individual? A student may memorize certain portions of the text and if a question is set from the portions he has prepared, he will no doubt secure good marks, while another student, brighter and more intelligent than the first, may not show good results because he did not especially prepare the questions which were set in the examination. A student may play football during the whole academic year and yet get through the examination. Another student may work hard throughout the year but unfortunately fall ill during the examination days and be thus declared unsuccessful. Is it justice? Is it fair play? It is a mockery. Papers of a lucky candidate may go to a lenient examiner, while bad luck may take yours to a stiff one. A marginal case may pass in the hands of one examiner and fail in another?s. It is a lottery. A lucky one may draw a prize ticket. while an unlucky one may draw blank. The mood of an examiner counts. If he has fallen out with his short-tempered wife, he may fail you.

An examiner, who has just received news of his promotion to class one, would like to share his good luck with his examinees. Are then again examinations a true test of one?s ability? When they come even the gayest of them forget all play and turn to worshippers at the altar of books day and night. This gives one some idea of the terror they strike into the heart of the poor examinees. Examinations are a plague. They are blood-suckers. Their after effects are pale cheeks and sunken eyes, grey hair, sleepless nights, physical and mental disorders.

A number of young men go mad year after year as a result of these examinations. Many more commit suicide for or after failing in them. How said: How deplorable? Most educationists now agree that a simple crucial examination is certainly no test of ability; they insist upon a series of practical tests of knowledge and intelligence over a period of two or three years .The results of all these tests, they say, should be taken into account when judging a student?s ability.

On the whole, it may be said that good students do not usually show bad results and that negligent students do not generally pass. They kill all originality. They play with the health and lives of the student. Examinations are a game of chance and skill.

Les plus récents

22 avril 2024 22:22

Elections en Inde

Inside story.

22 avril 2024 22:12

Ali Soliman: le photographe à la recherche de l’authenticité

22 avril 2024 22:00

Océan Indien

Pêche au thon: la transparence au centre des débats.

22 avril 2024 21:45

Questions à…

Usha reena rungoo: «le racisme s’est subtilement manifesté en 20 années passées au canada et aux états-unis».

22 avril 2024 21:39

Trou-d’Eau-Douce: le débarcadère ou un débarquement de vie

22 avril 2024 21:00

Reza: 50 ans derrière son comptoir

22 avril 2024 20:00

Infractions routières

Chiffres alarmants demandent mesures urgentes.

22 avril 2024 19:00

23 ans après

Meurtre de vanessa lagesse: bernard maigrot aux assises le 2 mai.

22 avril 2024 18:44

Plumes engagées

Mesaz a la nasyon.

22 avril 2024 18:42

Les humains sont comme les étoiles

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Authentic assessment.

- Kim H. Koh Kim H. Koh Werklund School of Education, University of Calgary

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.22

- Published online: 27 February 2017

Authentic tasks replicate real-world challenges and standards of performance that experts or professionals typically face in the field. The term “authentic assessment” was first coined by Grant Wiggins in K‒12 educational contexts. Authentic assessment is an effective measure of intellectual achievement or ability because it requires students to demonstrate their deep understanding, higher-order thinking, and complex problem solving through the performance of exemplary tasks. Hence authentic assessment can serve as a powerful tool for assessing students’ 21st-century competencies in the context of global educational reforms. The review begins with a detailed explanation of the concept of authentic assessment. There is a substantial body of literature focusing on the definitions of authentic assessment. However, only those that are original and relevant to educational contexts are included.. Some of the criteria for authentic assessment defined by the authors overlap with each other, but their definitions are consistent. A comparison of authentic assessment and conventional assessment reveals that different purposes are served, as evidenced by the nature of the assessment and item response format. Examples of both types of assessments are included. Three major themes are examined within authentic assessment research in educational contexts: authentic assessment in educational or school reforms, teacher professional learning and development in authentic assessment, and authentic assessment as tools or methods used in a variety of subjects or disciplines in K‒12 schooling and in higher education institutions. Among these three themes, most studies were focused on the role of authentic assessment in educational or school reforms. Future research should focus on building teachers’ capacity in authentic assessment and assessment for learning through a critical inquiry approach in school-based professional learning communities or in teacher education programs. To enable the power of authentic assessment to unfold in the classrooms of the 21st century, it is essential that teachers are not only assessment literate but also competent in designing and using authentic assessments to support student learning and mastery of the 21st-century competencies.

- authentic assessment

- authentic tasks

- criteria for authenticity

- 21st-century competencies

Introduction

The term “authentic assessment” was first coined in 1989 by Grant Wiggins in K‒12 educational contexts. According to Wiggins ( 1989 , p. 703), authentic assessment is “a true test” of intellectual achievement or ability because it requires students to demonstrate their deep understanding, higher-order thinking, and complex problem solving through the performance of exemplary tasks. Authentic tasks replicate real-world challenges and “standards of performance” that experts or professionals (e.g., mathematicians, scientists, writers, doctors, teachers, or designers) typically face in the field (Wiggins, 1989 , p. 703). For instance, authentic tasks in mathematics need to elicit the kind of thinking and reasoning used by mathematicians when they solve problems.

In the assessment literature, some authors have argued that the term “authentic” was first introduced by Archbald and Newmann ( 1988 ) in the context of learning and assessment (Cumming & Maxwell, 1999 ; Palm, 2008 ). However, the term “authentic” in Archbald and Newmann ( 1988 ) was associated with achievement rather than assessment. A few years later, Newmann and Archbald ( 1992 ) provided a detailed explanation of authentic achievement. Cumming and Maxwell ( 1999 ) have aptly pointed out that authentic assessment and authentic achievement are interrelated, as it is important to identify the desired student learning outcomes and realign the methods of assessment to them. Authentic assessment should be rooted in authentic achievement to ensure a close alignment between assessment tasks and desired learning outcomes. This alignment is of paramount importance in the worldwide climate of curriculum and assessment reform, which places greater emphasis on the development of students’ 21st-century competencies—including critical and creative thinking, complex problem solving, effective communication, collaboration, self-directed and lifelong learning, responsible citizenship, and information technological literacy, just to name a few.

In addition to K‒12 education, “authentic assessment” was further defined by Gulikers, Bastiaens, and Kirschner ( 2004 ) in the context of professional and vocational training that incorporates competence-based curricula and assessments. To better prepare students for their future workplace, there is a need for assessment tasks used in professional and vocational education to resemble the tasks students will encounter in their future professional practice. Authentic assessments in competence-based education should create opportunities for students to integrate learning and working in practice, which results in students’ mastery of professional skills needed in their future workplace.

Authentic assessment has played a pivotal role in driving curricular and instructional changes in the context of global educational reforms. Since the 1990s, teacher education and professional development programs in many education systems around the globe have focused on the development of assessment literacy for teachers and teacher candidates which encompasses teacher competence in the design, adaptation, and use of authentic assessment tasks or performance assessment tasks to engage students in in-depth learning of subject matter and to promote their mastery of the 21st-century competencies (e.g., Darling-Hammond & Snyder, 2000 ; Koh, 2011a , 2011b , 2014 ; Shepard et al., 2005 ; Webb, 2009 ). Although many of the 21st-century competencies are not new, they have become increasingly in demand in colleges and workplaces that have shifted from lower-level cognitive and routine manual tasks to higher-level analytic and interactive tasks (e.g., collaborative problem solving) (Darling Hammond & Adamson, 2010 ). The amount of new information is increasing at an exponential rate due to the advancement of digital technology. Hence, rote learning and regurgitation of facts or procedures are no longer suitable in contemporary educational contexts. Rather, students are expected to be able to find, organize, interpret, analyze, evaluate, synthesize, and apply new information or knowledge to solve non-routine problems.

Students’ mastery of the essential 21st-century competencies will enable them to succeed in colleges, to thrive in a fast-changing global economy, and to live meaningfully in a complex, technological connected world. According to Darling-Hammond and Adamson ( 2010 ), the role of performance assessment is critical in helping both teachers and students to achieve the 21st-century standards of assessment and learning. Many authors in extant research have used “performance assessment” and “authentic assessment” interchangeably (e.g., Arter, 1999 ; Darling-Hammond & Adamson, 2010 ). Some authors have distinguished between performance assessment and authentic assessment (Meyer, 1992 ; Palm, 2008 ; Wiggins, 1989 ). Thorough review of the literature suggests that there is a need to differentiate performance assessment from authentic assessment.

All authentic assessments are performance assessments because they require students to construct extended responses, to perform on something, or to produce a product. Both process and product matter to authentic assessments, and hence formative assessment—such as open questioning, descriptive feedback, self- and peer assessments—can be easily incorporated into authentic assessments. In other words, the process is as important as the product. As such, authentic assessments also capture students’ dispositions such as positive habits of mind, growth mindset, persistence in solving complex problems, resilience and grit, and self-directed learning. The use of scoring criteria and human judgments are two of the essential components of authentic assessments (Wiggins, 1989 ).

Although all performance assessments include constructed responses or performances on open-ended tasks, not all performance assessments are authentic. As Arter ( 1999 ) pointed out, the two essential components of a performance assessment include tasks and criteria. This suggests that the line between performance assessment and authentic assessment is thin. Hence, the authenticity of a performance assessment or performance-based tasks is best to be determined by Gulikers et al.’s ( 2004 ) five dimensions of authenticity; Koh and Luke’s ( 2009 ) criteria for authentic intellectual quality; Newmann, Marks, and Gamoran ( 1996 ) “intellectual quality” criteria; and Wiggins’s ( 1989 ) four key features of authentic assessment. The dimensional framework proposed by Gulikers et al. is appropriate for use with assessments in professional and vocational training contexts including higher education institutions, while Wiggins ( 1989 ), Newmann et al. ( 1996 ), and Koh and Luke ( 2009 ) are appropriate for use with assessments in K‒12 school contexts. The criteria for authentic intellectual quality by Koh and Luke ( 2009 ) have also been linked to the Singapore Classroom Coding Scheme, which was developed by Luke, Cazden, Lin, and Freebody ( 2005 ) to conduct classroom observations of teachers’ instructional practices. Some of the criteria for authentic intellectual quality were adapted from Newmann et al.’s ( 1996 ) authentic intellectual work, Lingard, Ladwig, Mills, Bahr, Chant, & Warry’s ( 2001 ) productive pedagogy and assessment, and the New South Wales model of quality teaching (Ladwig, 2009 ). Lingard et al. ( 2001 ) have used the term “rich tasks” instead of authentic tasks in the Queensland School Reform Longitudinal Study. According to the authors, rich tasks are open-ended tasks that enable students to connect their learning to real-world issues and problems.

In short, this section presents a detailed explanation of the concept of authentic assessment. The remaining sections of this article will include a comparison of authentic assessment and conventional assessment, criteria for authenticity in authentic assessment, authentic assessment research in educational contexts (research problems/questions and methods included), and future research in authentic assessment.

Authentic Assessment Versus Conventional Assessment

Authentic assessment serves as an alternative to conventional assessment. Conventional assessment is limited to standardized paper-and-pencil/pen tests, which emphasize objective measurement. Standardized tests employ closed-ended item formats such as true‒false, matching, or multiple choice. The use of these item formats is believed to increase efficiency of test administration, objectivity of scoring, reliability of test scores, and cost-effectiveness as machine scoring and large-scale administration of test items are possible. However, it is widely recognized that traditional standardized testing restricts the assessment of higher-order thinking skills and other essential 21st-century competencies due to the nature of the item format. From an objective measurement or psychometric perspective, rigorous and higher-level learning outcomes(e.g., critical thinking, complex problem solving, collaboration, and extended communication) are too subjective to be tested. An overemphasis on objective measurement and closed-ended item formats has led to the testing of discrete bits of facts and procedures. As such, curriculum is fragmented and dumbed down as many of the desired learning outcomes are measured as atomized bits of knowledge and skills.

Standardized paper-and-pen tests are administered in uniform ways to ascertain student achievement for summative purposes (i.e., grading and reporting at the end of a unit or a semester, certification at the completion of a course). At the classroom level, standardized tests are typically used in summative assessment at the end of instruction. Assessment is seen to be detached from instruction. Large-scale administration of standardized paper-and-pen tests is often used for cross-national comparisons of student achievement. The use of standardized paper-and-pen tests on a large-scale basis is predominant in state/provincial assessments and international assessments. Examples of state/provincial assessments are the Foundation Skills Assessments (FSA) in British Columbia, Canada; the Provincial Achievement Tests (PAT) in Alberta, Canada; and the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) in the United States. International assessments include the Trends in Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS); the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS); and the Program in International Student Assessment (PISA). The closed-ended item response format in standardized tests tends to encourage students to fill in the bubbles or provide short answers using their rote memorization of discrete facts and procedures. Students are either rewarded or punished depending on whether they get that one answer right according to the answer keys or marking schemes. Such a testing format is aligned with the behaviorist learning theory that promotes the use of rewards to reinforce positive behaviors and of sanctions to remove negative behaviors.

Both summative and international assessments are high stakes because student achievement data derived from these assessments are used for making important decisions or policies, which may lead to unintended consequences for students, teachers, or school administrators. Oftentimes, teacher job performance is evaluated based on student performance on high-stakes assessments. In many high-performative education systems, teachers are held accountable by policy makers, parents, and school administrators for students’ performance. Such a high accountability demand has led to teachers’ tendency to teach to the content and format of state/provincial, national, or international assessments. For example, Koh and Luke’s ( 2009 ) large-scale empirical study of the quality of teachers’ assessment tasks in Singapore, one of the high-performative education systems in the world, has shown that worksheets and summative tests were two of the most commonly used assessment methods in the teaching of core subject areas such as English, mathematics, and science at both elementary and secondary levels. Teachers’ instructional practices were driven by preparing students for high-stakes examinations. As a result, the intended curriculum was reduced to a drill-and-practice of decontextualized factual and procedural knowledge.

Authentic assessments are characterized by open-ended tasks that require students to construct extended responses, to perform an act, or to produce a product in a real-world context—or a context that mimics the real world. Examples of authentic assessments include projects, portfolios, writing an article for newsletter or newspaper, performing a dance or drama, designing a digital artifact, creating a poster for science fair, debates, and oral presentations. According to Wiggins ( 1989 ), authentic tasks must “involve students in the actual challenges, standards, and habits needed for success in the academic disciplines or in the workplace” (p. 706). In other words, authentic tasks need to be designed to replicate the authentic intellectual challenges and standards facing experts or professionals in the field. Such assessment tasks are deemed able to engage and motivate learners when they perceive the relevance of the tasks to the real world or when they find that a completion of the tasks is meaningful for their learning.

The purpose of authentic assessment is to provide students with ample opportunity to engage in authentic tasks so as to develop, use, and extend their knowledge, higher-order thinking, and other 21st-century competencies. Authentic tasks are often performance-based and include complex and ill-structured problems that are well aligned with the rigorous and higher-order learning objectives in a reformed vision of curriculum (Shepard, 2000 ). Most professional challenges in the current and future workplace require individuals to strike a balance between individual and group achievement (Wiggins, 1989 ). The nature of authentic tasks enables students to learn how to achieve such a balance by engaging in independent learning of possible solutions and by collaborating with peers in a socially supportive learning environment over an extended period of time. As such, authentic tasks also support problem-based learning, inquiry-based learning, and other learner-centered pedagogical approaches. Productive discourse or extended communication in a social context is important in the process of arriving at solutions to problems. Hence students are able to “experience what it is like to do tasks in workplace and other real-life contexts” (Wiggins, 1998 , p. 24). John Dewey, a prominent philosopher of education, underscored the importance of experience in education by arguing that learners cannot know something without directly experiencing it. Dewey inspired the use of the project method in his laboratory school at the University of Chicago from 1896 to 1904 . The project method enabled children to reflect and examine critically at their prior beliefs or preexisting knowledge in the light of new experiences. Children were expected to learn content knowledge and procedural skills in a context that was relevant to their real-world lives. The context usually entails a complex, real-life problem or authentic project, with many levels of embedded problems and solutions. The project method was further defined as a “hearty purposeful act” by Kilpatrick ( 1918 , p. 320) in his essay “The Project Method,” which became known worldwide.

Authentic tasks assess not only students’ authentic performance or work, but also their dispositions such as persistence in solving messy and complex problems, positive habits of mind, growth mindset, resilience and grit, and self-directed learning. Given that the use of scoring rubrics is a key component of authentic assessment, it enables the provision of descriptive feedback, self- and peer assessment using criteria and standards as in the form of holistic or analytic rubrics. It is important that students receive timely and formative feedback from the teacher and/or peers so that they are able to use the feedback to improve the quality of their performance or work. Such a formative assessment or assessment for learning practice has long been advocated in key assessment literature that urges teachers to use classroom assessment to support student learning or to promote a learner-centered classroom culture (e.g., Black & Wiliam, 1998 ; Shepard, 2000 ). From a social-constructivist learning approach (Shepard, 2000 ), the opportunities for productive discourse or dialogue in the process of collaborating with peers and of giving/receiving peer feedback in completing authentic tasks underscore the importance of co-construction of knowledge and meaning-making through socially supported interactions.

Since the 1990s, the social-constructivist learning theory has played a key role in the curriculum and assessment reform movement. The social-constructivist learning theory was named an emergent constructivist paradigm in Shepard’s ( 2000 ) reconceptualization of classroom assessment practice for the 21st century . The emergent constructivist paradigm was characterized by the shared principles of a reformed vision of curriculum, cognitive and constructivist/social-constructivist learning theories, and classroom assessment. The shared principles emphasize that all students can learn, and thus they must be given an equal opportunity to be exposed to intellectually challenging subject matter and assessment tasks that are aimed at developing their higher-order thinking, problem solving, and dispositions. The principles of classroom assessment in Shepard’s ( 2000 ) emergent constructivist paradigm are similar to those that characterize authentic assessment.

Criteria for Authenticity in Authentic Assessment

There is a substantial curriculum and assessment literature focusing on the features or characteristics of authentic assessment. The use of “features” and “characteristics” seems to suggest that an assessment or a task can be quantifiable for its authenticity. I prefer to use the term “criteria” to determine and describe the degree of authenticity of an assessment or a task. This section includes a review of the relevant literature on the criteria of authentic assessment.

According to Wiggins ( 1989 , 1998 ), assessment is central to learning and must be linked to real-world demands. In these articles, some of the criteria for authentic assessment are overlapping. They can be summarized into eight criteria:

First , authentic assessment “is realistic” (Wiggins, 1998 , p. 22). This means that the authentic task or tasks must replicate how a student’s knowledge, skills, and/or dispositions are assessed in a real-world context. In other words, the authentic task or tasks should replicate or simulate the real-world contexts in which adults are assessed in the workplace, in social life, and in personal life. This enables students to experience what it is like to work or perform in real-life contexts, which are often messy, ambiguous, and unpredictable. Such a “learning by doing” experience is in line with Dewey’s experiential education.

Second , the authentic task or tasks require students to make good judgments and be creative and innovative in solving complex and non-routine problems or performing a task in new situations. This enables the assessment of transferable skills to new tasks or contexts. In addition, students need to be competent and confident in using a repertoire of knowledge, skills, and dispositions to tackle and complete authentic tasks that are intellectually challenging. Hence, authentic tasks serve as an effective tool for assessing students’ demonstrations of critical thinking, complex problem solving, and creativity and innovation. These are some of the essential 21st-century competencies.

Third , an authentic assessment or task enables students to deeply engage in the subject or discipline through critical thinking and inquiry. Instead of rote learning and reproduction of facts and procedures, students need to be able to think, act, and communicate like experts in the subject or discipline. This is akin to Shulman’s ( 2005 ) signature pedagogies.

Fourth , in authentic assessment, students are given opportunities to rehearse, practice, look for useful resources, and receive timely quality feedback so as to improve the quality of performance or product. Students also need to present their work publicly and be given the opportunity to defend it. This suggests that assessment for learning or formative assessment practice can be easily incorporated into authentic assessment.

Fifth , authentic tasks look for multiple evidences of student performance over time and the reasons or explanations behind the success and failure of a performance. In addition, both reliability and validity of judgment about complex performance depend upon multiple evidences gained over many performances across multiple occasions. To ensure fairness and equity, the teacher must be provided with informative data of students’ strengths and weaknesses at the end of each assessment. This will ensure that the teacher’s feedback is aimed at helping all students to make progress toward the standards.

Sixth , a multifaceted scoring system is used, and scoring criteria must be transparent. Sharing of scoring criteria explicitly with students will enable them to understand and internalize the criteria of success.

Seventh , student self-assessment must play a pivotal role in authentic assessment.

Finally , the reliability or defensibility of teachers’ professional judgment or scoring of student performance or work is achieved through social moderation, in which teachers of the same subjects gather to set criteria and standards for scoring, and to compare their scores (Klenowski & Wyatt-Smith, 2010 ).

Authentic achievement rather than authentic assessment is used in Newmann and Archbald ( 1992 ). They identify three criteria or standards for authentic achievement, namely, construction of knowledge , disciplined inquiry , and value beyond school . In their later work, Newmann et al. ( 1996 ) and Newmann, Bryk, and Nagaoka ( 2001 ) have used the term “criteria for authentic intellectual work” instead of “standards for authentic achievement.” Definitions of the three criteria for authentic achievement are as follows:

Construction of Knowledge

This criterion clearly indicates that students need to engage in construction or production of knowledge instead of reproduction of knowledge. Construction of knowledge is expressed in written and oral discourse. Examples of construction of knowledge are writing an article for a newsletter, performing a musical piece of work, creating a poster for a science fair, completing a group project, and designing a digital portfolio. All of these authentic assessments require students to engage in higher-order thinking, problem solving, communication, and collaboration. At the same time, students also need to present and defend their work in public.

Disciplined Inquiry

This criterion suggests that students need to be actively involved in critical inquiry within academic subjects or professional disciplines. Disciplined inquiry consists of three main components: prior knowledge base , in-depth understanding , and elaborated communication (Newmann et al., 2001 , p. 15). Students’ authentic performance is built on their prior knowledge in a subject or discipline. To engage in critical inquiry, students need to be able to tap into their prior knowledge base or the content knowledge that they have acquired before. The prior knowledge base or previously learned content knowledge includes facts, terminologies, vocabularies, concepts, theories, algorithms, procedures, and conventions. In-depth understanding refers to the ability to probe deeper into a problem and to organize, interpret, analyze, evaluate, and synthesize different types of knowledge or information that can be used to solve the problem. In-depth understanding helps students to engage actively in intellectual discourse or in making extended communication to explain their solutions to the problem. All experts or professionals in a subject or discipline are expected to use sophisticated forms of written and oral communication (i.e., elaborated communication) to carry out their work and to express their solutions to problems.

Value Beyond School

This criterion underscores the importance of having a value dimension in assessment tasks. To be intrinsically motivating for students, authentic tasks must have aesthetic, utilitarian, or personal value in the eyes of the learner.

Newmann et al. ( 1996 ) have pointed out that all three of these criteria are necessary for assessing the authenticity of student performance across grade levels and subject areas. They aptly stated that “construction of knowledge through disciplined inquiry to produce discourse, products, or performance that have value beyond success in school can serve as a standard of intellectual quality for assessing the authenticity of student performance” (Newmann et al., 1996 , p. 287). However, they also cautioned that not all instructional activities and assessment tasks will meet all the three criteria at all times.

Building upon the three criteria of authentic achievement, Newmann et al. ( 1996 ) have further developed seven criteria for assessing the intellectual quality of assessment tasks. The criteria are organization of information , consideration of alternatives , disciplinary content , disciplinary process , elaborated written communication , problem connected to the world , and audience beyond the school . Organization of information and consideration of alternatives reflect the importance of assessing students’ higher-order thinking or critical thinking in solving real-world problems. Disciplinary content emphasizes students’ ability to engage in critical inquiry into the ideas, theories, and perspectives central to their academic subject or professional discipline, while disciplinary process refers to the ability to use sound methods of inquiry, research, and communication, which is central to their academic subject or professional discipline. The use of elaborated written communication suggests that authentic tasks must involve students in using extended communication or sustained writing to express deep understanding and problem solving. The last two criteria, namely, problem connected to the world and audience beyond the school , indicate that assessment tasks need to expose students to the real-world issues or problems that they encounter in their daily lives or are likely to encounter in their future colleges, workplaces, and lives.

Gulikers et al. ( 2004 ) have proposed five criteria for defining authentic assessment in the context of professional and vocational training. Similar to Wiggins ( 1989 ) and Newmann and Archbald ( 1992 ), they contend that authenticity of assessment is a multifaceted concept. In determining the authenticity of an assessment, there is a need to take into account students’ perceptions of authenticity. In other words, students’ perceptions of the meaningfulness or relevance of the assessment is central to the determination of authenticity. The five criteria for authenticity or dimensions of authenticity are task , physical context , social context , assessment form , and criteria (Gulikers et al., 2004 ). The criteria are summarized below:

Using Messick’s ( 1994 ) question of authentic to what , Gulikers et al. ( 2004 ) have argued that the degree of authenticity of an assessment or a task is measured against a criterion situation. According to them, “a criterion situation reflects a real-life situation that students can be confronted with in their work placement or future professional life, which serves as a basis for designing an authentic assessment” (Gulikers et al., 2004 , p. 75). Therefore, an authentic assessment task should resemble the complexity of the knowledge, skills, and dispositions required in the criterion situation. And students should see the relevance or meaning of their performances on the authentic task to their future professions. The degree of authenticity of an assessment task can further be determined by whether the task requires multiple solutions and whether it is ill-structured and involves multiple disciplines.

Physical Context

In this criterion, three components are identified by Gulikers et al. ( 2004 ) to determine the degree of authenticity of an assessment: similarity to the professional work space (fidelity), availability of professional resources (methods/tools/materials, relevant or irrelevant information), and time given to complete the assessment task. Sufficient time for the completion of a task is important so that students’ thinking and acting will not be restricted by time constraints. Many professional activities in real life involve planning and execution of tasks over an extended period of time.

Social Context

The social processes of an authentic assessment must resemble those of a professional context. If the professional context or real-life situation requires collaboration with peers in solving problems, then the assessment should also involve students in collaboration and problem solving. However, it is important to note that if a professional context or real-life situation typically requires individual work then the assessment should not enforce collaboration. In other words, fidelity of the social processes in authentic assessment to those in a real-life situation is essential.

Assessment Form

The authenticity of assessment form is determined by the degree to which students are observed for their demonstrations of competences when performing on a task or creating a product. The observation will enable an inference about students’ competences in future professional contexts. The authenticity of the form of assessment also depends on the use of multiple tasks and indicators of learning. This is similar to Wiggins’s ( 1989 ) multifaceted scoring system, which emphasizes the use of multiple evidences of student performance. Many measurement and assessment experts also advocate for the use of multiple methods or tasks and multiple indicators of learning to ensure the accuracy, fairness, reliability, and validity of professional judgment about student performance (Messick, 1994 ; Shavelson, Baxter, & Gao, 1993 ; Wiggins, 1989 ). Hence, students’ professional competence should neither be assessed by a single task nor be judged based on a single performance.

Scoring criteria used in authentic assessment should be based on criteria used in professional practice or a real-life situation. In addition, scoring criteria should concern the development of relevant professional competence, which means that assessment of students’ learning progression is an important practice in the context of authentic assessment. Similar to Wiggins ( 1989 ), Gulikers et al. ( 2004 ) have argued that scoring criteria must be transparent and be shared explicitly with students to facilitate their learning. Hence, criterion-referenced rubrics should be used to judge students’ performance or work in authentic assessment.

Research in Authentic Assessment

Since the 1990s, research in authentic assessment was focused on three themes: authentic assessment in educational or school reforms, teacher professional learning or development in authentic assessment, and authentic assessment as tools or methods used in a variety of subjects or disciplines in K‒12 schooling and in higher education institutions. Among these three themes, most studies were focused on the role of authentic assessment in educational or school reforms. Due to space limitations, only key studies concentrating on authentic assessment in educational or school reforms have been reviewed.

Authentic Assessment in Educational or School Reforms

Since the late 1990s, authentic assessment has become a key lever for educational or school reforms that aim to develop students’ 21st-century competencies and prepare them for a global knowledge-based economy in a technologically connected world. In the curriculum frameworks of many education systems, there is a shift from low-level learning outcomes (e.g., factual knowledge and procedural skills) to higher-order learning outcomes (i.e., higher-order thinking, problem solving, and other essential 21st-century competencies). Likewise, teachers have been urged to move toward the use of social-constructivist, learner-centered pedagogy, authentic assessment, and formative assessment. Such changes have resulted in a substantial body of research focusing on teachers’ assessment practices and building teachers’ capacity in classroom assessment.

In the United States, Newmann and his associates (Newmann et al., 1996 ; Newmann et al., 2001 ) have conducted empirical studies to examine the impact of authentic pedagogy on student performance in Chicago public elementary schools. The focus of Newmann et al.’s ( 1996 ) study was to determine the relationship between authentic pedagogy and student performance in schools that used authentic pedagogy as a school reform initiative. Authentic pedagogy was comprised of authentic instruction and authentic assessment based on the criteria for authentic intellectual work. The study involved teachers who taught mathematics and social studies in three different grades ranging from elementary schools to high schools. Data included classroom observations of the teachers’ daily lessons and analyses of the assessment tasks and students’ written responses to the tasks that were embedded within the lessons. The data were analyzed using the criteria for authentic intellectual work. Student responses to the assessment tasks were used as evidence of student performance.

Most studies on educational or assessment reforms have often used standardized test scores as an indicator of improved student learning even when an educational innovation involves a new form of assessment. Student responses to tasks or student work samples are embedded within teachers’ instructional practices and hence serve as a better indicator of student performance. Newmann et al. ( 1996 ) found that authentic pedagogy was strongly associated with students’ authentic academic performance at all grade levels in both mathematics and social studies. Students who were exposed to assessment tasks with high intellectual demands demonstrated higher authentic performance than students who did not have the same exposure. In addition, the effects of authentic pedagogy were found to be equitably distributed among students of diverse social backgrounds, indicating that all students should have an equal access to the standards of intellectual quality. The findings suggest that student performance is dependent on the quality of teachers’ assessment tasks, and authentic assessment can play a pivotal role to raise the quality of students’ learning and performance irrespective of their gender, ethnic group, and socioeconomic status. Authentic assessment can serve as a powerful mechanism to ensure equitable learning opportunities and outcomes for all students.

In a second study, Newmann et al. ( 2001 ) examined the effects of authentic assignments or assessments on students’ authentic intellectual work in the day-to-day classroom and students’ achievement in high-stakes standardized tests. Samples of classroom assignments were collected from 19 elementary schools in Chicago. The study involved approximately 5,000 students and their teachers in grades 3, 6, and 8. These grades were purposefully selected because of the relevance of using test scores from both the statewide and national testing programs. This allowed the researchers to “link teacher assignments both to student performance on state tests of reading, writing, and mathematics and to results from the national norm-reference tests of reading and mathematics” (Newmann et al. 2001 , p. 16). In addition to test scores, teacher assignments in writing and mathematics were analyzed for their intellectual demands. A group of teachers from the Chicago public schools were trained to judge the quality of teacher assignments using scoring rubrics that consisted of the criteria for authentic intellectual work. Newmann et al. ( 2001 ) found that when teachers organized instruction around authentic assignments, students not only produced more authentic, intellectually complex work but also gained greater scores in both statewide and national tests in reading and mathematics. Similar results were noted in some very disadvantaged classrooms. Newmann et al. ( 2001 ) also pointed out that the intellectual demands in teacher assignments or assessment tasks played a far more important role than a particular teaching strategy or pedagogical method to influence student engagement in learning. Hence, professional development for teachers should focus on their capacity in designing and using curriculum materials and classroom assessments that include high authentic intellectual challenge.

Newmann et al.’s ( 1996 ) work, originating in the United States, has been adapted and expanded in the Queensland School Reform Longitudinal Study (Lingard et al., 2001 ). The criteria for authentic intellectual work provided the basis for the Queensland model of productive pedagogies, assessment, and performance (Lingard et al. 2001 ). In Lingard et al.’s ( 2001 ) criteria for productive assessment, the three Newmann criteria of authentic intellectual work were extended to include knowledge criticism , technical metalanguage , inclusive knowledge , and explicitness of expectations as new indicators. Similar to Newmann et al.’s ( 1996 ) authentic pedagogy, productive pedagogies were intellectually demanding, connected to the real world, supportive of student learning, and diversity valuing. Lingard et al. ( 2001 ) found that the levels of intellectual or cognitive demand of teachers’ assessment tasks were positively associated with the quality of students’ performance as evidenced in students’ written work. This important finding has led to the New Basics trial of curriculum in grades 1‒9 in Queensland schools. The New Basics curriculum was aligned with productive pedagogies and rich tasks (i.e., authentic tasks). The trial yielded positive outcomes. As such, the use of rich tasks and teacher-moderated judgment of students’ work in response to rich tasks have become exemplary assessment practices in many Queensland schools. Such exemplary assessment practices are applauded by policy makers, school administrators, educators, and researchers around the globe. This has led to the Core 1 Pedagogy and Assessment project in Singapore (Luke, Freebody, Lau, & Gopinathan, 2005 ).

Both the Newmann et al. ( 1996 ) and Lingard et al. ( 2001 ) studies served as the basis for Koh and Luke’s ( 2009 ) study of Singaporean teachers’ assessment practices. As one of the world’s high-performing education systems, Singapore has launched a variety of educational reforms since the beginning of the 21st century . Like their counterparts in other developed countries, Singaporean teachers have been urged to implement new forms of assessment (i.e., authentic assessment and formative assessment) to capture higher-order learning outcomes in the intended curriculum. The Koh and Luke study was conducted to examine Singaporean teachers’ assessment practices as well as the quality of teachers’ assessment tasks and the quality of students’ work in grades 5 and 9 in seven subject areas: English, social studies, mathematics, sciences, Mandarin Chinese, Malay, and Tamil. It was the first large-scale empirical study of teachers’ assessment practices and the data were drawn from a representative sample of Singaporean classrooms. Following the framework of Newmann et al. ( 1996 ) and the work from Anderson and Krathwohl ( 2001 ), Marzano ( 1992 ), and Nitko ( 2004 ), Koh and Luke ( 2009 ) have devised nine criteria for assessing the quality of teachers’ assessment tasks and six criteria for assessing the quality of students’ work in response to the assessment tasks.

The nine criteria for assessment tasks were depth of knowledge , knowledge criticism , knowledge manipulation , sustained writing , task clarity and organization , connections to the real world beyond the classroom , supportive task framing , student control , and explicit performance standards or marking criteria . The six criteria for assessing the quality of students’ work included depth of knowledge , knowledge criticism , knowledge manipulation , sustained writing , quality of students’ writing or answers , and connections to the real world beyond the classroom (Koh, 2011a ).

Brief descriptions of the criteria are as follows:

Depth of Knowledge

According to the revised Bloom’s taxonomy of intended student learning outcomes, there are three types of knowledge, namely, factual knowledge, procedural knowledge, and advanced concepts or conceptual knowledge (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001 ). Factual knowledge is knowledge of discrete and decontextualized content elements (i.e., bits of information), while procedural knowledge entails knowledge of using discipline-specific skills, rules, algorithms, techniques, tools, and methods. Conceptual knowledge involves knowledge of complex, organized, and structured knowledge forms (e.g., how a particular subject matter is organized and structured, how the different parts or bits of information are interconnected and interrelated in a more systematic manner, and how these parts function together). All three types of knowledge are essential for student learning.

Knowledge Criticism

Based on models of critical literacy and critical pedagogy, knowledge criticism is a predisposition to the generation of alternative perspectives, critical arguments, and new solutions or knowledge (Luke, 2004 ). Knowledge criticism enables students to judge the value, credibility, and soundness of different sources of information or knowledge through comparison and critique rather than to accept and present all information or knowledge as given.

Knowledge Manipulation

Knowledge manipulation calls for an application of higher-order thinking and reasoning skills in the reconstruction of texts, intellectual artifacts, and knowledge. It involves organization, interpretation, analysis, synthesis, and/or evaluation of different sources of knowledge or information (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001 ). Authentic assessments or tasks should provide students with more opportunities to make their own hypotheses and generalizations in order to solve problems, arrive at conclusions, or discover new meanings, rather than only to reproduce information expounded by the teacher or textbooks, or to reproduce fragments of knowledge and preordained procedures.

Sustained Writing

This criterion aims to gauge the degree to which the assessment task requires and generates production of extended chunks of prose. Authentic assessments or tasks must ask students to elaborate on their nuances/understanding, explanations, arguments, or conclusions through the generation of sustained written prose.

Task clarity and organization , student control , and explicit performance standards or marking criteria are conceptualized based on Marzano’s ( 1992 ) learning-centered instruction. The assumption here is that the explicitness of the procedures and criteria for the assessment task provides clear goals and explicit criteria and language for the assessment of value. The incorporation of these criteria into the classroom assessment provides students with ample opportunity to engage in formative assessment or assessment for learning, which contributes to their self-directed learning, independent learning, and critical thinking.

Task Clarity and Organization

The assessment task is framed logically and has instructions that are easy to understand so that students will not have misinterpretations and missing information. The written instructions, guidelines, worksheets, and other textual advanced organizers must be clear and well organized.

Connections to the Real World Beyond the Classroom

This criterion assesses the degree to which the assessment task and affiliated artifacts were connected to an activity, function, or task in a real-world situation.

Supportive Task Framing

Teachers’ scaffolding of an assignment or assessment task—that is, providing some structure and guidance—can assist students to accomplish a complex task (Nitko, 2004 ). There are three types of scaffolding: content, procedural, and strategic. For highly intellectual tasks, teachers should place more emphasis on strategic scaffolding.

Student Control