- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Black Death

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 28, 2023 | Original: September 17, 2010

The Black Death was a devastating global epidemic of bubonic plague that struck Europe and Asia in the mid-1300s. The plague arrived in Europe in October 1347, when 12 ships from the Black Sea docked at the Sicilian port of Messina. People gathered on the docks were met with a horrifying surprise: Most sailors aboard the ships were dead, and those still alive were gravely ill and covered in black boils that oozed blood and pus. Sicilian authorities hastily ordered the fleet of “death ships” out of the harbor, but it was too late: Over the next five years, the Black Death would kill more than 20 million people in Europe—almost one-third of the continent’s population.

How Did the Black Plague Start?

Even before the “death ships” pulled into port at Messina, many Europeans had heard rumors about a “Great Pestilence” that was carving a deadly path across the trade routes of the Near and Far East. Indeed, in the early 1340s, the disease had struck China, India, Persia, Syria and Egypt.

The plague is thought to have originated in Asia over 2,000 years ago and was likely spread by trading ships , though recent research has indicated the pathogen responsible for the Black Death may have existed in Europe as early as 3000 B.C.

Symptoms of the Black Plague

Europeans were scarcely equipped for the horrible reality of the Black Death. “In men and women alike,” the Italian poet Giovanni Boccaccio wrote, “at the beginning of the malady, certain swellings, either on the groin or under the armpits…waxed to the bigness of a common apple, others to the size of an egg, some more and some less, and these the vulgar named plague-boils.”

Blood and pus seeped out of these strange swellings, which were followed by a host of other unpleasant symptoms—fever, chills, vomiting, diarrhea, terrible aches and pains—and then, in short order, death.

The Bubonic Plague attacks the lymphatic system, causing swelling in the lymph nodes. If untreated, the infection can spread to the blood or lungs.

How Did the Black Death Spread?

The Black Death was terrifyingly, indiscriminately contagious: “the mere touching of the clothes,” wrote Boccaccio, “appeared to itself to communicate the malady to the toucher.” The disease was also terrifyingly efficient. People who were perfectly healthy when they went to bed at night could be dead by morning.

Did you know? Many scholars think that the nursery rhyme “Ring around the Rosy” was written about the symptoms of the Black Death.

Understanding the Black Death

Today, scientists understand that the Black Death, now known as the plague, is spread by a bacillus called Yersinia pestis . (The French biologist Alexandre Yersin discovered this germ at the end of the 19th century.)

They know that the bacillus travels from person to person through the air , as well as through the bite of infected fleas and rats. Both of these pests could be found almost everywhere in medieval Europe, but they were particularly at home aboard ships of all kinds—which is how the deadly plague made its way through one European port city after another.

Not long after it struck Messina, the Black Death spread to the port of Marseilles in France and the port of Tunis in North Africa. Then it reached Rome and Florence, two cities at the center of an elaborate web of trade routes. By the middle of 1348, the Black Death had struck Paris, Bordeaux, Lyon and London.

Today, this grim sequence of events is terrifying but comprehensible. In the middle of the 14th century, however, there seemed to be no rational explanation for it.

No one knew exactly how the Black Death was transmitted from one patient to another, and no one knew how to prevent or treat it. According to one doctor, for example, “instantaneous death occurs when the aerial spirit escaping from the eyes of the sick man strikes the healthy person standing near and looking at the sick.”

How Do You Treat the Black Death?

Physicians relied on crude and unsophisticated techniques such as bloodletting and boil-lancing (practices that were dangerous as well as unsanitary) and superstitious practices such as burning aromatic herbs and bathing in rosewater or vinegar.

Meanwhile, in a panic, healthy people did all they could to avoid the sick. Doctors refused to see patients; priests refused to administer last rites; and shopkeepers closed their stores. Many people fled the cities for the countryside, but even there they could not escape the disease: It affected cows, sheep, goats, pigs and chickens as well as people.

In fact, so many sheep died that one of the consequences of the Black Death was a European wool shortage. And many people, desperate to save themselves, even abandoned their sick and dying loved ones. “Thus doing,” Boccaccio wrote, “each thought to secure immunity for himself.”

Black Plague: God’s Punishment?

Because they did not understand the biology of the disease, many people believed that the Black Death was a kind of divine punishment—retribution for sins against God such as greed, blasphemy, heresy, fornication and worldliness.

By this logic, the only way to overcome the plague was to win God’s forgiveness. Some people believed that the way to do this was to purge their communities of heretics and other troublemakers—so, for example, many thousands of Jews were massacred in 1348 and 1349. (Thousands more fled to the sparsely populated regions of Eastern Europe, where they could be relatively safe from the rampaging mobs in the cities.)

Some people coped with the terror and uncertainty of the Black Death epidemic by lashing out at their neighbors; others coped by turning inward and fretting about the condition of their own souls.

Flagellants

Some upper-class men joined processions of flagellants that traveled from town to town and engaged in public displays of penance and punishment: They would beat themselves and one another with heavy leather straps studded with sharp pieces of metal while the townspeople looked on. For 33 1/2 days, the flagellants repeated this ritual three times a day. Then they would move on to the next town and begin the process over again.

Though the flagellant movement did provide some comfort to people who felt powerless in the face of inexplicable tragedy, it soon began to worry the Pope, whose authority the flagellants had begun to usurp. In the face of this papal resistance, the movement disintegrated.

How Did the Black Death End?

The plague never really ended and it returned with a vengeance years later. But officials in the port city of Ragusa were able to slow its spread by keeping arriving sailors in isolation until it was clear they were not carrying the disease—creating social distancing that relied on isolation to slow the spread of the disease.

The sailors were initially held on their ships for 30 days (a trentino ), a period that was later increased to 40 days, or a quarantine — the origin of the term “quarantine” and a practice still used today.

Does the Black Plague Still Exist?

The Black Death epidemic had run its course by the early 1350s, but the plague reappeared every few generations for centuries. Modern sanitation and public-health practices have greatly mitigated the impact of the disease but have not eliminated it. While antibiotics are available to treat the Black Death, according to The World Health Organization, there are still 1,000 to 3,000 cases of plague every year.

Gallery: Pandemics That Changed History

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Accessibility links

- Skip to content

- Skip to local navigation

- Skip to bbc.co.uk navigation

- Skip to bbc.co.uk search

- Accessibility Help

British History in-depth

- Ancient History

- British History

- Historic Figures

- Family History

- Hands on History

- History for Kids

- On This Day

Black Death: The lasting impact

By Professor Tom James Last updated 2011-02-17

The long term effects of the Black Death were devastating and far reaching. Agriculture, religion, economics and even social class were affected. Contemporary accounts shed light on how medieval Britain was irreversibly changed.

On this page

The onset of the plague, contemporary accounts, society turned upside down, never the same again, find out more, page options.

- Print this page

Contemporaries were horrified by the onset of the plague in the wet summer of 1348: within weeks of midsummer people were dying in unprecedented large numbers. Ralph Higden of Chester, the best known contemporary chronicler thought 'scarcely a tenth of mankind was left alive'. His analysis of the scale of the mortality is repeated by other commentators. The phrase 'there were hardly enough living to care for the sick and bury the dead' is repeated in various sources including a chronicle compiled at St Mary's Abbey, York. The Malmesbury monk, writing in Wiltshire, reckoned that 'over England as a whole a fifth of men, women and children were carried to the grave'. The plague did not abate in the Winter but became even more virulent in the early months of 1349 and continued into 1350.

Chroniclers and administrators make numerous references to the extension of graveyards, for example in Bristol, and to the mass burial of bodies in pits. At Rochester (Kent) men and women cast their dead children into communal graves 'from which arose such a stench that it was barely possible to go past a churchyard'. Modern excavation of such pits in London, near The Tower on the site of former Royal Mint and in the cathedral close at Hereford, testify to these extreme measures. In London the pits took the form of long, narrow trenches with bodies laid in orderly rows: at Hereford the evidence was of more haphazard committal to the earth.

...scarcely a tenth of mankind was left alive.

Today we have the benefit of hindsight. We know, as fourteenth-century people suspected, that the mortality caused by the bubonic plague of the Black Death was the worst demographic disaster in the history of the world. We also know that the mortality came to an end in the first outbreak soon after 1350; contemporaries could not have known this would happen - so far as they were concerned everyone might well die. Some treated each day as if it were their last: moral and sexual codes were broken, while the marriage market was revitalised by those who had lost partners in the plague.

We also know that the plague returned regularly, first in 1361 and then in the 1370s and 1380s and, as an increasingly urban disease, right through until the Great Plague of 1665 in London. But by around 1670 it disappeared from England for over two centuries until a number of outbreaks occurred either side of 1900. It was not until these modern outbreaks that the bacillus was identified and connection between rats and plague discovered. Despite all their best efforts people in the historic period had no remedy against the mysterious plague, except as Daniel Defoe put it, to run away from it.

The sustained onslaught of plague on English population and society over a period of more than 300 years inevitably affected society and the economy. Evidence of the effects can be measured and responses traced not only in social and economic, political and religious terms, but also in changes in art and architecture. The effects of the Black Death in all these matters were disputed by contemporaries and are still hotly disputed today, which makes the topic so endlessly fascinating.

The effects of the Black Death...are still hotly disputed today...

By way of example, Ralph Higden, a contemporary chronicler, argued that 'lords and great men escaped'. By contrast, Geoffrey le Baker, an Oxfordshire man, noted deaths among the nobility. And so there were: one of King Edward III's daughters, archbishops, bishops, abbots, abbesses, nobles and lords of manors died in the first outbreak. In 1361 the Duke of Lancaster, a leading general, was among the victims. Le Baker also noted the immediate effects on the young and strong: 'the weak and elderly it generally spared'. In 1361 we find references to the outbreak being especially fierce among children. Later plagues were especially violent, as noted above, in towns. At Southampton, for example, in the sixteenth century, between 15 and 25% of the population was carried off every twenty years by outbreaks of plague. However, there is no doubt that proportionately the hardest-hit part of society was the most numerous: the peasantry, labourers and artisans.

Following the plague we find a clear sense of society turned upside down in England. The rulers of the kingdom reacted strongly. Some elements of legislation indicate a measure of panic. Within a year of the onset of plague, during 1349, an Ordinance of Labourers was issued and this became the Statute of Labourers in 1351. This law sought to prevent labourers from obtaining higher wages. Despite the shortage in the workforce caused by the plague, workers were ordered to take wages at the levels achieved pre-plague. Landlords gained in the short term from payments on the deaths of their tenants (heriots), but 'rents dwindled, land fell waste for want of tenants who used to cultivate it' (Higden) and '...many villages and hamlets were deserted...and never inhabited again'. Consequently, landed incomes fell. The bulging piles of manorial accounts which survive for the period of the Black Death testify to the active land-market and the additional administration caused by the onset of plague. But all too often the administration consists of noting defaults of rent because of plague (defectus causa pestilencie).

...many villages and hamlets were deserted...and never inhabited again.

It has been argued that the Black Death brought about the end of feudalism. This was the system of service in return for a grant of land, burdening the peasant with many obligations to his lord. For example, payments were due on entering a land holding, upon marriage and death and on many other occasions. The Black Death did not start the process of the commutation (substitution) of a money payment for labour and other services. However, there is no doubt that the plague speeded up the process by reducing dramatically the numbers of peasants and artisans. By how much commutation accelerated is still a matter of fierce debate.

Government and landlords tried to keep the lid on rising wages and changing social aspirations. Lords and peasants alike were indicted for taking higher wages. In 1363 a Sumptuary Law was brought through parliament. This measure decreed not only the quality and colour of cloth that lay people at different levels of society (below the nobility) should use in their attire but also sought to limit the common diet to basics. Such legislation could only occur when the government had observed upwardly-mobile dress among the lower orders. Such legislation was virtually impossible to enforce, but indicates that among those who survived the plague there was additional wealth, from higher wages and from accumulated holdings of lands formerly held by plague victims.

In Chaucer's Canterbury Tales of 1387 the well-known Prologue describes the dress of each pilgrim. Arguably, it demonstrates that apart from the knight, the poor parson and the ploughman, who personify each of the three traditional divisions of medieval society, every pilgrim is dressed more grandly that the Sumptuary Law would allow. The Canterbury Tales came six years after the Great Revolt of 1381 in which rebellion flared throughout much of England, the Kent and Essex men invaded London, chopped off Archbishop Sudbury's head and terrified the fourteen-year-old Richard II into agreeing concessions on the Poll Tax and other matters. The Poll Tax was an unsuccessful attempt by the government to combat the effects of plague by changing the basis of taxation from a charge on communities (many much less populous following successive plagues), with a tax on individuals who had survived. Chaucer, the court poet, was very aware of the anxieties of the elite in the new post-plague society. His Canterbury pilgrims, as the courtiers encountered them, were arranged 'by rank and degree' and sent back down the road to Canterbury in perfect order, led by the knight: precisely the opposite to the unruly mob which had marched up from Canterbury in 1381.

If lay society was never the same again after the Black Death, nor was the English Church. Contemporaries were quick to note that the Black Death killed proportionately at least as many clergy as laity. New recruits were noted as being of a lesser quality. Henry Knighton, writing in Leicester, said of these new clerks that many of them were illiterate, no better than laymen - 'for even if they could read, they did not understand'. Worse still, clergy post-plague demanded from twice to ten times more than before for a vicarage or chaplaincy. Some clergy deserted their posts, and left their churches to 'wild beasts'. A fierce argument raged in the first half of the twentieth century between F.A. Gasquet, who became a cardinal in England, and the Cambridge historian G.G. Coulton over the effects of the plague on the medieval church. Gasquet saw the plague as a catastrophe which ruined the church in England through clergy mortality, and was among the seeds of the Reformation on the sixteenth century. Coulton, by contrast, argued that clergy mortality in the Black Death was exaggerated by monkish writers and that the clergy abandoned their posts and fled. There is evidence on both sides and the argument rages!

In a sense the Black Death was the prehistory both of enclosure and of the Reformation.

In summary, the vast majority of the population at the time of the Black Death was rural peasants who suffered the highest mortality and in so doing, became much more expensive and choosy about where they worked, and how they related to lords. Weakened communities provided the opportunity in the century and a half after the plague for landlords to clear lands and enclose them for sheep, so that Sir Thomas More, writing soon after 1500, saw the countryside as overrun and consumed by sheep. People certainly expected and obtained higher wages even in the church, whose authority was challenged by many, including Chaucer in his mocking Canterbury Tales. Recruitment to the parish clergy fell and monastic houses never recovered. In a sense the Black Death was the prehistory both of enclosure and of the Reformation. Perhaps Cardinal Gasquet was right when he noted long ago that the plague led to the emergence for the first time of a middle class (who chatter and challenge authority) funded by accumulating the wealth of those who had died. Thus the old medieval tripartite division of society into those who fought (the nobility and knights), those who prayed (the churchmen) and those who laboured (the peasants) was never the same again.

The Black Death by Philip Ziegler, illustrated edition (Sutton, 1991)

The Black Death by Rosemary Horrox (1994)

The Black Death in Wessex by Tom Beaumont James (Salisbury, 1998)

The Black Death in Hampshire by Tom Beaumont James (Winchester, 1999)

About the author

Author, broadcaster and lecturer Professor Tom Beaumont James teaches archaeology and history at the University of Winchester. He has published special studies of the Black Death as a turning point in history, and of medieval palaces. He contributed a history of Britain to BBC Worldwide's This Sceptered Isle. Two major publications are out in 2006: The King's Landscape: Clarendon Park (Wiltshire) , with Chris Gerrard and The Winchester Census of 1871 , with Mark Allen.

«; More Middle Ages

British history timeline.

- Explore the British History Timeline from the Neolithic to the present day

World War One Centenary

- Find out more about how the BBC is covering the World War One Centenary , and see the latest programmes and online content

Surviving the trenches

- Dan Snow asks why so many soldiers survived the trenches in WW1

The History of the Home

- Take a journey through the history of the home . Each room tells a different story.

Search term:

BBC navigation

- Northern Ireland

- Full A-Z of BBC sites

You're using the Internet Explorer 6 browser to view the BBC website. Our site will work much better if you change to a more modern browser. It's free, quick and easy. Find out more about upgrading your browser here…

- Mobile site

- Terms of Use

- About the BBC

- Contact the BBC

- Parental Guidance

BBC © 2014 The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites. Read more.

This page is best viewed in an up-to-date web browser with style sheets (CSS) enabled. While you will be able to view the content of this page in your current browser, you will not be able to get the full visual experience. Please consider upgrading your browser software or enabling style sheets (CSS) if you are able to do so.

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University website

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

The Black Death and its Aftermath

- John Brooke

The Black Death was the second pandemic of bubonic plague and the most devastating pandemic in world history. It was a descendant of the ancient plague that had afflicted Rome, from 541 to 549 CE, during the time of emperor Justinian. The bubonic plague, caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis , persisted for centuries in wild rodent colonies in Central Asia and, somewhere in the early 1300s, mutated into a form much more virulent to humans.

At about the same time, it began to spread globally. It moved from Central Asia to China in the early 1200s and reached the Black Sea in the late 1340s. Hitting the Middle East and Europe between 1347 and 1351, the Black Death had aftershocks still felt into the early 1700s. When it was over, the European population was cut by a third to a half, and China and India suffered death on a similar scale.

Traditionally, historians have argued that the transmission of the plague involved movement of plague-infected fleas from wild rodents to the household black rat. However, evidence now suggests that it must have been transmitted first by direct human contact with rodents and then via human fleas and head lice. This new explanation better explains the bacteria’s very rapid movement along trade routes throughout Eurasia and into sub-Saharan Africa.

At the time, people thought that the plague came into Mediterranean ports by ship. But, it is also becoming clear that small pools of plague had been established in Europe for centuries, apparently in wild rodent communities in the high passes of the Alps.

The remains of Bubonic plague victims in Martigues, France.

We know a lot about the impact of the Black Death from both the documentary record and from archaeological excavations. Within the last few decades, the genetic signature of the plague has been positively identified in burials across Europe.

The bacillus was deadly and took both rich and poor, rural and urban: the daughter of King Edward III of England died of the plague in the summer of 1348. But quickly—at least in Europe—the rich learned to barricade their households against its reach, and the poor suffered disproportionately.

Strikingly, if a mother survived the plague, her children tended to survive; if she died, they died with her. In the late 1340s, news of the plague spread and people knew it was coming: plague pits recently discovered in London were dug before the arrival of the epidemic.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder's 1562 painting "The Triumph of Death" depicts the turmoil Europe experienced as a result of the plague.

The Black Death pandemic was a profound rupture that reshaped the economy, society and culture in Europe. Most immediately, the Black Death drove an intensification of Christian religious belief and practice, manifested in portents of the apocalypse, in extremist cults that challenged the authority of the clergy, and in Christian pogroms against Europe’s Jews.

This intensified religiosity had long-range institutional impacts. Combined with the death of many clergy, fears of sending students on long, dangerous journeys, and the fortuitous appearance of rich bequests, the heightened religiosity inspired the founding of new universities and new colleges at older ones.

The proliferation of new centers of learning and debate subtly undermined the unity of Medieval Christianity. It also set the stage for the rise of stronger national identities and ultimately for the Reformation that split Christianity in the 16 th century.

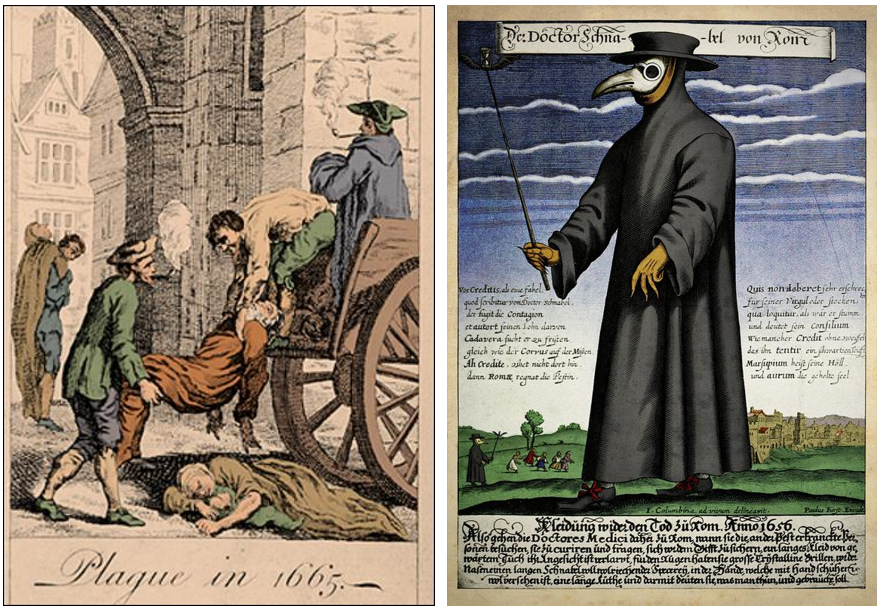

Depiction of the Great Plague of London in 1665 (left) . A copper engraving of a seventeenth-century plague doctor (right) .

The disruption caused by the plague also shaped new directions in medical knowledge. Doctors tending the sick during the plague learned from their direct experience and began to rebel against ancient medical doctrine. The Black Death made clear that disease was not caused by an alignment of the stars but from a contagion. Doctors became committed to a new empirical approach to medicine and the treatment of disease. Here, then, lie the distant roots of the Scientific Revolution.

Quarantines were directly connected to this new empiricism, and the almost instinctive social distancing of Europe’s middling and elite households. The first quarantine was established in 1377 at the Adriatic port of Ragussa. By the 1460s quarantines were routine in the European Mediterranean.

Major outbreaks of plague in 1665 and 1721 in London and Marseille were the result of breakdowns in this quarantine barrier. From the late 17th century to 1871 the Habsburg Empire maintained an armed “cordon sanitaire” against plague eruptions from the Ottoman Empire.

Michel Serre's painting depicting the 1721 plague outbreak in Marseille.

As with the rise of national universities, the building of quarantine structures against the plague was a dimension in the emergence of state power in Europe.

Through all of this turmoil and trauma, the common people who survived the Black Death emerged to new opportunities in emptied lands. We have reasonably good wage data for England, and wage rates rose dramatically and rapidly, as masters and landlords were willing to pay more for increasingly scarce labor.

The famous French historian Marc Bloch argued that medieval society began to break down at this time because the guaranteed flow of income from the labor of the poor into noble households ended with the depopulation of the plague. The rising autonomy of the poor contributed both to peasant uprisings and to late medieval Europe’s thinly disguised resource wars, as nobles and their men at arms attempted to replace rent with plunder.

A depiction of the 1381 Peasant's Revolt in England.

At the same time, the ravages of the Black Death decimated the ancient trade routes bringing spices and fine textiles from the East, ending what is known as the Medieval World System, running between China, India, and the Mediterranean.

By the 1460s, the Portuguese—elbowed out of the European resource wars—began a search for new ways to the East, making their way south along the African coast, launching an economic globalization that after 1492 included the Americas.

And we should remember that this first globalization would lead directly to another great series of pandemics, not the plague but chickenpox, measles, and smallpox, which in the centuries following Columbus’s landing would kill the great majority of the native peoples of the Americas.

In these ways we still live in a world shaped by the Black Death.

Let your curiosity lead the way:

Apply Today

- Arts & Sciences

- Graduate Studies in A&S

How the Black Death made life better

Christine R. Johnson is associate professor of history in the Department of History.

“[The] mortality destroyed more than a third of the men, women, and children … such a shortage of workers ensued that the humble turned up their noses at employment, and could scarcely be persuaded to serve the eminent unless for triple wages. … As a result, churchmen, knights and other worthies have been forced to thresh their corn, plough the land and perform every other unskilled task if they are to make their own bread.”

— account of the black death in the cathedral priory chronicle at rochester (written no later than 1350).

In its entry on the Black Death, the 1347–50 outbreak of bubonic plague that killed at least a third of Europe’s population, this chronicle from the English city of Rochester includes among its harrowing details a seemingly trivial lament: Aristocrats and high clergymen not only had to pay triple wages to those toiling in their fields, but, even worse, they themselves had to perform manual labor. Curiously, the documentary record, which provides ample evidence that workers did demand and receive higher wages (on which more below), contains in contrast scant evidence that “worthies” ever dirtied their hands with fieldwork. Even if (or especially as) phantasms, however, these sickle-wielding lords reveal the importance of imagined possibilities in shaping pandemic responses.

The eminent refused to take on menial roles, not because they could not perform these “unskilled” tasks, but because to do so would be unworthy of their social rank, and it was unthinkable to abandon that social and labor hierarchy. Farm work was peasant work, whether performed by serfs bound to a particular manor, tenant farmers or wage laborers hired by the year or the season. But the staggering mortality of the Black Death reduced this previously sufficient peasant population sharply enough to create a severe labor shortage.

What happened next has been the subject of an enormous amount of scholarship, particularly in the case of England, where the large extant body of sources such as chronicles, legislation, court cases and manorial account books provides rich material for studying the social and economic changes in the wake of the Black Death. Scholars disagree about how and how much things changed, but they share a tendency to describe these changes in oddly passive terms: wages rose, inequality decreased, feudalism ended.

Yet there was a great deal of deliberate (in)action behind these developments. Rather than supply some of the needed labor themselves, landowners turned to solutions that might produce the kind of world they were capable of imagining. In England they created first the Ordinance (1349) and then the Statute (1351) of Labourers, which froze wages at pre-plague levels, compelled workers not otherwise engaged in fixed, long-term employment into year-long contracts with the first employer who demanded it, and established penalties to ensure compliance. As Jane Whittle has noted, in putting their efforts behind the control of waged labor rather than the retrenchment of (already declining) serfdom, rural landowners sought a “thinkable” resolution to this impasse: They would use the existing market for labor, but control the terms of exchange.

Many peasants, however, refused to play their assigned role of deferential wage earner. Court records from 1352, for example, show that “Edward le Taillour of Wootton, employee of the prior and convent of Bradenstoke … left his employment before the feast of St Nicholas [6 December] without permission or reasonable cause, contrary to statute,” and that John Death of Wroughton demanded an “excess” of six shillings eightpence for reaping John Lovel’s corn. Recalcitrant laborers remained a problem in 1374, when “John Fisshere, William Theker, William Furnes, John Dyker, Gilbert Chyld, Alan Tasker, Stephen Lang, John Hardlad, Cecilia Ka, Joan daughter of Henry Couper, Matillis de Ely, Alice wife of Simon Souter, all of Bardney, labourers, refused to work [for the Abbot of Bardney at the stipulated wages], and on the same day they left the town to get higher wages elsewhere, in contempt of the king and contrary to statute.”

With many state governments reducing unemployment benefits to push workers to fill open jobs, the aim, like England after the Black Death, is to reinstate and reinforce previous social and labor hierarchies, regardless of whose work has actually been “essential” over the past 16 months.

These records attest to some individuals’ appreciation of the increased value of their labor in the new marketplace created by mass death. The number and geographical range of these individual acts of defiance, moreover, suggest a vibrant, if unrecorded, current of communal discussions, rumors and calculations that supported such individual agency. In the face of official intransigence, workers pushed for higher wages and greater mobility, which they received because “churchmen, knights, and other worthies” were willing to make these concessions, rather than have to work the fields and herd the sheep themselves. As a result, wages rose, inequality lessened … and the social and labor hierarchies remained the same.

Thankfully, the current COVID-19 pandemic is vastly less lethal than the mid 14th-century bubonic plague, and we can hope that people around the world do not experience the loss of human life on the same scale. What the Black Death does share with our present moment is the issue of labor and the limits drawn by the negative space of the unthinkable.

The people who prospered under the pre-pandemic system are now deciding what “back to normal” looks like and how we get there. With many state governments reducing unemployment benefits to push workers to fill open jobs, the aim, like England after the Black Death, is to reinstate and reinforce previous social and labor hierarchies, regardless of whose work has actually been “essential” over the past 16 months. Workers in specific circumstances and with individual or collective determination might negotiate better labor conditions or higher wages, but these concessions’ permanance remains in the hands of employers who saw no reason to implement them prior to the pandemic. As historians Ada Palmer and Eleanor Janega have argued, whatever gains peasants and artisans obtained in the decades after the Black Death did not survive the following centuries. Elites successfully reclaimed a greater share of wealth and income, hierarchies ossified, and laborers’ power diminished.

Simply stating that English society was changed by the Black Death not only discounts the people who did the changing, but also ignores the insufficiencies of the changes they produced. The Rochester chronicler raised the specter of knights and churchmen toiling in the fields to evoke the unthinkable scale of the disaster, and then refused to contemplate this radically different social order any further. We are not the Rochester chronicler. How can we think the unthinkable — about safety and health, racial justice, gender roles, immigration status, access to childcare, and the dignity, autonomy and worth of labor — for our own post-pandemic future?

All quoted material from Rosemary Horrox, ed., The Black Death (Manchester University Press, 1994).

Headline image: Medieval illustration of men harvesting wheat with reaping-hooks, on a calendar page for August, circa 1310. Queen Mary's Psalter (Ms. Royal 2. B. VII), fol. 78v, The British Library.

in the news:

Q&A with writer Amitava Kumar

What a cube, a drop and a wave taught me about creativity, communication and community

Origins and empires: Reading coins for rulers’ stories

Workshop taught students to calm climate anxiety with community action

Home — Essay Samples — History — Black Death — Black Death: Humanity’s Grim Catalyst

Black Death: Humanity's Grim Catalyst

- Categories: Black Death

About this sample

Words: 486 |

Published: Mar 6, 2024

Words: 486 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, economic impact, social and cultural impact.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: History

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 894 words

2 pages / 1049 words

2 pages / 696 words

5 pages / 2464 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Black Death

Becker, C. (2016). The Black Death: The Great Mortality of 1348-1350: A Brief History with Documents. Bedford/St. Martin's.Cohn, S. K. (2019). The Black Death and the History of Plagues, 1345-1730. Cambridge University [...]

The Black Death, a devastating pandemic that swept through Europe in the 14th century, and COVID-19, the ongoing global pandemic caused by the novel coronavirus, have left indelible marks on history. This essay seeks to analyze [...]

Imagine a world where a devastating disease sweeps across continents, leaving death and destruction in its wake. This was the reality of the Black Death, a plague that ravaged Europe in the 14th century and forever changed the [...]

In the Medieval Era the Black Plague was more than just a thorn in a lion's side. During the time, few people ever reached what is now our national life expectancy. The Black Plague's success rate for fatality still haunts us to [...]

The Black Death, also known as the Black Plague, Bubonic Plague, and sometimes just “The Plague”, was one of the worst diseases to hit Europe back in the 14th century. The Black Plague, according to Modern Historians, had killed [...]

‘Mariana’ is a poem by Alfred Lord Tennyson which was published in 1830. This was an early stage of the Victorian era, a time when there was a plethora of social upheavals in England and Europe. As a composition, 'Mariana' is a [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Covering books and digital resources across all fields of history

ISSN 1749-8155

Town and Countryside in the Age of the Black Death: Essays in Honour of John Hatcher

This collection of essays forms an excellent Festschrift for Professor John Hatcher, whose eclectic range of research is displayed by the volume’s division into three parts: the first explores the medieval demographic system; the second charts the changing relationship between lords and peasants; and the third highlights the fortunes of trade and industry after the Black Death. As Mark Bailey notes in his introduction, the Black Death ‘stands unchallenged as the greatest disaster in documented human history’(p. xx). This Festschrift showcases the pioneering work John Hatcher has conducted over his distinguished career, revisiting the significance of his empirical studies of monastic mortality, his early work on the Duchy of Cornwall, and his comprehensive study of the coal industry. As such, this volume brings together a range of important, influential and innovative essays and is particularly aided by a generous word length which allows many of the contributors to provide a critical literature review of previous work making this an invaluable volume for students and academics alike. This is further aided by short bibliographies of cited works provided at the end of each chapter. However, given the overall length of the volume and the diverse range of subjects explored, the volume would have benefited from a unifying subject index.

In the first of three chapters focusing upon demography, Ole Benedictow explores the historical controversy surrounding the concept of a ‘high pressure’ medieval demographic system, which was qualitatively different from the ‘low pressure’ early modern equivalent. In the former, mortality was the key determinant of population size at around four or five per cent and a life expectancy of between 20 and 25 years, with a high marriage rate resulting in high levels of fertility. In the latter, mortality rates were around three to three and a half per cent, life expectancy was between 30 and 35 years, and the usual age at first marriage was between 24 and 26 years. Benedictow argues that a ‘key factor in this transition was the great change in the understanding of infectious diseases which began at the end of the fifteenth century’, which saw the introduction of preventive measures to combat the spread of diseases and the gradual reduction in mortality levels, paving the way for the gradual transition to the early modern demographic system (p. 33).

In a particularly insightful survey of medieval demographic history, Richard M. Smith discusses Postan’s original suggestions of population decline; Gottfried, Glennie and Goldberg’s work on wills; and the pioneering work conducted by John Hatcher concerning the death rates and life expectancies of monks. From this discussion Smith shows that there is a consensus developing which emphasises a decrease in the life expectancies of monks from the 1450s until the 1520s. He then uses a sample of Inquisitions Post Mortem from the 14th century to show that Russell may have under-estimated life expectancy by as much as 25 per cent. This further reinforces the idea of a drop in life expectancies in the second half of the 15th century and Smith concludes that there is increasing evidence for the presence of a mortality cycle from the 1450s which saw life expectancy decline and instability in death rates worsen. This presents an intriguing conundrum: if England was experiencing increased mortality in the second half of the 15th century, how are we to explain the improvement in rents and the collection of arrears experienced by many landowners in this same period which are suggestive of renewed pressure on landed resources?

Maryanne Kowaleski focuses upon the demography of maritime communities in late medieval England, exploring the many similarities between such communities and their early-modern counterparts. Although the medieval evidence is often lacking, she is able to suggest that there was a high amount of maritime occupations such as fishing, shipping and piracy and that there is evidence for high male mortality and male absences, with a high percentage of single people and large numbers of households headed by women. She concludes that there were a number of ‘striking similarities’ in the demographic features of medieval and later coastal communities and that the nature of maritime communities produced continuity rather than contrast between the late medieval and early modern periods (p. 112).

In a collection of chapters focusing upon the changing relationship between landlords and peasants, Bruce M. S. Campbell considers the causes and consequences of changes in grain yields, exploring changes in tree-ring data, global temperatures, and sea level pressure. He suggests that there were six distinctive sub-periods in the chronology of yields: disastrous harvests of 1349–51/2; persistently poor harvests until 1369–75; dramatic improvement from 1376 until the mid-1390s; worsening harvests into the 1420s; heightened yield variability of the 1430s and 1440s; and following a respite in the 1450s, the return of dismal harvests in the final decades of the century. His chapter contains invaluable figures and tables concerning much of the scientific evidence for the beginning of a cooler and stormier Little Ice Age, including an indexed appendix showing grain yields per seed. Ultimately, Campbell argues that ‘many of the most abiding economic and social features’ of the years following the Black Death ‘sprang in part from the low, varying, and uncertain yield of grain’ (p. 162).

Martin Stephenson explores the capital formation, investment and risk awareness of medieval landowners. He shows that the authors of agricultural treatises were aware of risks, ranging from the human risk of embezzlement by untrustworthy officials to the natural vagaries of the weather, and suggested ways to counteract them. Stephenson argues that Postan and Hilton underestimated capital investment, which he finds was more in the region of 17 per cent than the five per cent they suggested. This was a figure nearly double that of ‘improving’ 18th-century landlords, although at least part of this discrepancy is because these later landowners were purely rentiers and thus their only capital investment took the form of the repair and construction of buildings. As Stephenson acknowledges, alongside buildings, purchasing livestock was ‘perhaps the main outlet for the expansion of capital stock in medieval society’ (p. 188). Thus his only post-Black Death case study of Downton manor shows that investment levels dropped to 9.2 per cent from 1431 when the land was leased out in its entirety; a figure remarkably similar to the 9.3 per cent for Norfolk and Suffolk estates in the late 18th century. His essay does, however, call for a reassessment of the investment levels of landowners as well as a renewed appreciation of their risk awareness with his suggestion that risk-taking increased during ‘difficult economic circumstances’ compared to relatively buoyant periods (p. 208).

In a particularly interesting and detailed chapter, David Stone questions the orthodoxy that there was more continuity than change in the aftermath of the Black Death by focusing upon the immediate and short-term consequences of the pestilence. Thus, we see how communities prepared for the impending arrival of the Black Death, purchasing extra locks to secure the bake-house doors and restricting movement around the estate between autumn 1348 and spring 1349. He argues that the Black Death had significant ‘economic reverberations’ which saw the opening of ‘Pandora’s Box’: patterns of consumption had begun to change; wage-arrangements were riddled with subterfuge; and the expectations of labourers and landowners were changing (p. 241). It seems likely that if pestilence had not returned and the population recovered to its previous levels then medieval lords could have fashioned a makeshift lid for ‘Pandora’s Box’, but ultimately Stone’s essay succeeds in showing that the immediate consequences of the Black Death should not be underestimated and that ‘continuity in administration should not be mistaken for a return to normality’ (p. 229).

Erin McGibbon Smith explores the various methodological problems of using manorial court rolls, criticising past work which has either focused upon the analysis of a narrow range of themes from the total business of the court, or has sought out multiple series of good court rolls without ensuring it is examining records from the same time. This has numerous disadvantages, not least the fact that the lords' officials focused on some offences and not others, and thus as Smith argues, the ‘“window” provided by rolls changed in size, shape and opacity over time’ (p. 252). She uses seven categories of court business to illustrate changes across the Black Death: the lord’s rights; inter-peasant litigation; community nuisance; officials and court function; crime and misbehaviour; land; and the market. One of the most significant changes in her categories concerns that of ‘crime and misbehaviour’ which shows a distinct peak in violent crime in 1335–45, bringing into question Ambrose Raftis’ widely accepted argument that a decline in the ‘village community’ took place after the onset of the Black Death.

Phillipp Schofield revisits Hatcher’s early work on the Duchy of Cornwall using the archives of the Earls of Arundell to explore regional trends in Cornwall. He argues that a combination of economic factors better explain the general success and stability of the Arundell estates in the second half of the 15th century rather than the sub-regional patterns which Hatcher emphasised, and that ‘explanations for robustness must also be detected in the local economy beyond the estate itself’ (p. 293). Schofield’s chapter is particularly important in exploring the inter-relationship between late medieval seigneurial economies and the non-manorial sector. He also discusses the relative lack of innovation on the Arundell estate, and states that where there was change it was largely ‘consistent with past practice’ (p. 291). Despite this, the Earls were willing to ‘let holdings both for differing terms, at lower rents, and to permit accumulation’, thus emphasising that they may well have been rentiers but this ‘did not mean that they were inert as landlords’ (p. 292).

John Munro’s chapter focuses upon the period from 1370 until 1420 which saw the widespread leasing of demesne land across medieval England. Unlike many of the other contributors, Munro focuses upon the role of monetary and fiscal factors in producing the momentous changes in the economy of this period rather than relying upon demographic explanations of change. His chapter provides a lucid summary of the various elements of this argument, ranging from the problem of the ‘time-lag’ between the Black Death and changes in socio-economic trends in the 1370s, and the problem of ‘wage-stickiness’. He argues that a combination of price-scissors, problems of capital and personal indebtedness led lords ‘to convert villein tenancies into leaseholds, with fewer or no servile obligations’ as the enforcement costs of serfdom became too expensive (p. 337). This reliance on broad fiscal and monetary factors to explain change has numerous advantages and highlights some of the pitfalls of demographic determinism, but also runs the risk of reducing the events at Smithfield and Mile End to little more than a footnote in the history of medieval England.

The final three chapters explore trade and industry after the Black Death. James Davis explores the trade in food and drink in one small town (Clare, Suffolk) in order to examine the immediate and longer-term impact of the Black Death. He considers the wide range of factors influencing trade in market towns, ranging from demography and inter-related aspects of supply and demand, to standards of living, seigneurial reactions and lower-class aspirations. Davis concludes that the enforcement of the assizes of ale was as ‘much the product of social and political interests as of economic factors’, and that the arrival of a new lord brought with it a change in direction with the townsfolk gaining ‘de facto control of the market and court’ (p. 370). Overall, Davis shows how there was a sharp expansion in opportunities and regulation soon after the Black Death lasting into the 1370s; changes between the 1380s and 1410s as the level of amercements fell away; and by the 15th century, there were low levels of amercements and ‘seemingly less interference in everyday market life’ (p. 395).

John S. Lee highlights the current lack of knowledge concerning fairs between the mid 14th and mid 16th centuries compared to either the preceding or succeeding periods. He shows that the number of grants for new fairs did not decline as much as for new markets in the 15th century, although unfortunately, as Lee discusses, the sources often do not indicate the success or longevity of many of these fairs. In particular, Lee highlights the wide range of goods traded at fairs, from wool and cloth, to livestock and fish, to household and consumer goods, as well as emphasising the role fairs played as gatherings for entertainment, social activities and gathering news. He also emphasises the way in which fairs were important in meeting the growing consumer demands of everyday people after the Black Death, who were increasingly experiencing a rise in living standards. His essay highlights the importance of fairs, suggesting that ‘their continuing prominence at least merits consideration in any reassessment of the debate over late medieval “urban decline”’ (p. 428).

In a fitting final chapter of the volume, Richard H. Britnell explores the coal industry of the Bishops of Durham. He pays considerable attention to the people engaged in the coal trade, showing that this entrepreneurship was ‘broadly based, involving Newcastle merchants, episcopal administrators, ecclesiastical bodies of all sizes, gentry families, other lay landowners of varied status, and skilled local tenants’ (p. 467). His chapter shows the fundamental differences between inland and coastal coal mines, with the inland mines at Railey showing surprising buoyancy during the entirety of the 15th century. Of particular interest is his suggestion that these sales were dependent ‘upon the local household demand’ of tenants even in the depth of the mid 15th-century recession, which by the early 16th century could account for as much as 17,500 tons being sold to ‘various people coming to the said mine’ across just two years (p. 449). Britnell’s essay thus provides a platform for future research into the consumption patterns of Durham tenants in the 15th century: how and why did local tenants incorporate coal into their everyday lives during the depth of the mid-century recession?

As Mark Bailey concluded his introduction: ‘debate will continue to rage over the exact consequences of the Black Death’ (p. xxxvi). This collection of essays is a noteworthy and welcome contribution to this debate and forms a fitting Festschrift for such a pioneering figure in the study of the economic and social history of medieval England.

The editors were happy to read the positive review and do not wish to reply.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

The Effects of the Black Death on the Life, Culture and Mentality of Medieval People

Related Papers

Mac Zentner

Benton Ludgin

IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science

Panchanan Dalai

Sait KIRTEPE

Rowland S . Ward

Michael A G Haykin

Matthew Corbitt

Brooke Bobincheck

This work argues that in the wake of the Black Death, the Holy Church struggled to maintain the supremacy it had just a century earlier. The social and political tactics the papacy used to regain hegemony during the active phase of the Black Death can be seen as a continuation of Church policy from the first Crusade through the beginning of the Age of Exploration, including the Reconquista, taking place in Iberia, Spain in circa CE 1492, more than a hundred and forty years after the Black Death had ceased ravaging central and western Europe. This work comprises elements of military analysis, historical observation, factual inclusion of relevant chronologically specific detail, and historical narrative to synthesize the thesis. This paper utilizes military analysis to examine the societal impact of the Church’s struggle to maintain and regain its traditional position in the face of increasingly powerful secular leadership and the lay reaction to clerical neglect in the face of the Black Death.

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

83 Black Death Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best black death topic ideas & essay examples, ⭐ good research topics about black death, 👍 simple & easy black death essay titles, ❓ research questions about the black death.

- Impact of the Black Death An obvious social impact of the plague is the fact that the Black Death led to a significant reduction in the human population of the affected areas.

- The Catholic Church and the Black Death in the 14th Century Therefore, the essence of this research paper is to investigate the role of Catholic Church during the Black Death, specifically paying attention to the steps the church used to prevent the disease, the Flagellants and […] We will write a custom essay specifically for you by our professional experts 808 writers online Learn More

- Black Death and COVID-19 Comparison The availability of highly complex treatment systems and the provision of medical care to the majority of the population alleviates the potential negative effects of the virus, allowing sick individuals to receive necessary medications.

- The Demographics Impact of Black Death and the Standard of Living Controversies in the Late Medieval This article explores the property rights of the Europeans in the aftermath of the Black Death. In this article, Zapotoczny focuses on the effects of the Black Death.

- Flash Point History Documentary About the Black Death IN order to document the spread of the plague, a number of different maps and graphs are used, allowing the creators to showcase the spread of the plague throughout Europe.

- The Black Death: Causes and Reactions This paper discusses the causes of the Black Death, human contribution to the spread of the disease, and describes the responses to the Black Death.

- Comparison of Black Death and COVID-19 Decameron, the classic piece of medieval literature, starts with a depiction of the devastating plague the Black Death. Luckily, COVID-19 mortality rates are nothing in comparison with the Black Death.

- The Black Death in Europe: Spread and Causes The bacterium persists more commonly in the lymphatic system of the groin, armpits, and neck, and increasing pain of the bubonic elements is one of the central symptoms of the disease.

- The Plague (The Black Death) of 1348 and 1350 European population of nearly 30 to 60% has fallen victims to Black Death which indicates the death of 450 million in the year 1400. The objective of this agency is to track and probe the […]

- The Black Death in Medieval Europe According to the institution, the pestilence that affected France, Italy, Germany, and other countries was majorly a result of some configurations of planets. The Faculty added that the vapor and hot air were also a […]

- Economic Impact of the Black Death in the European Society This paper will focus on the economic impact of the Black Death and the changes that occurred to European society after the catastrophe. The most noticeable effect of the Black Death was the abrupt decline […]

- Early Modern Europe After the Black Death The decrease of the population had a considerable on commercial relations since due to the disappearance of the working class which the main basis in the medieval economy, peasants become more conscious and prudent.

- Black Death of Archbishop and Scientific Progress The death led to the development of potential domains in modern medicine. His closeness to the king would have contributed to the rapid development of science.

- The Black Death Effect on the Medieval Europe It is inappropriate to perceive the problem only in the light of sharply declining numbers of population, and changes in the patterns of settlement.

- Black Death’s Effect on Religion in Europe To fully understand the impact of the Black Death pandemic, it is important to establish the power of the Catholic Church in the years before the appearance of the plague.

- The Black Death and Michael Dols’s Theory The biggest problem is that many believed that it cannot be contagious because of religious reasons, and it has led to numerous casualties. However, the issue is that it was not possible to control the […]

- The Black Death Disease’ History The disease is also believed to have come to Europe from the black mice that were often seen on the merchants’ boats.

- The Black Death, the Late Medieval Demographic Crises, and the Standard of Living Controversies Such claims make the name of the pandemic a moot point because another group of historians dispute the idea that the name originated from the discoloration of the victims’ skins, but it is instead a […]

- The Black Death and Its Influence on the Renaissance

- Plague, Politics, and Pogroms: The Black Death, Rule of Law, and the Persecution of Jews in the Holy Roman Empire

- Black Death and Its Effects on Europe’s Population, Economy, Religion, and Politics

- The Black Death and Bubonic Plague During the Elizabethan Era

- Before and After the Black Death: Money, Prices, and Wages in Fourteenth-Century England

- After the Black Death: Labor Legislation and Attitudes Towards Labor in Late-Medieval Western Europe

- The Black Death and Its Effect on the Change in Medicine

- Diseases and Hygiene Issues in England: The Black Death Plague

- The Black Death: Human History’s Biggest Catastrophe

- The Black Death: Bubonic Plague’s Worst Disaster

- Agricultural and Rural Society After the Black Death

- Economic Shocks, Inter-Ethnic Complementarities and the Persecution of Minorities: Evidence From the Black Death

- The Black Death: Key Facts About the Bubonic Plague

- Microbes and Markets: Was the Black Death an Economic Revolution

- The Black Death and Property Rights

- Confusion and Chaos in Europe During the Spread of the Black Death

- The Most Significant Pandemics -The Black Death

- The Black Death and the Comprehensive Outlook of Human Development

- Demographic Decline Black Death and the Ottoman Turks

- The Black Death: How Different Were Christian and Muslim

- The Black Death and Its Effects on Western Civilization

- Black Death and Its Effects on European and Asian Societies

- The Black Death: Long Term and Short Term Effects

- Black Death Slowly Creeps Across Asia, Europe, and Great Britain

- Adverse Shocks and Mass Persecutions: Evidence From the Black Death

- Pandemics, Places, and Populations: Evidence From the Black Death

- Socio-Economic, Political, Religious, and Cultural Consequences of the Black Death

- The Black Death: The Darkest Period of European History

- Agrarian Labor Productivity Rates Before the Black Death

- The Black Death Killed More Than a Third of the Population

- Black Death and the Devastation It Caused: Political, Economic and Social Structures of Medieval Europe

- The Black Death and Its Effects on European Culture

- European Goods Market Integration in the Very Long Run: From the Black Death to the First World War

- Political, Psychological, Economic, and Social Aftermath of the Black Death

- Social and Religious Changes Influenced by the Black Death

- Christian and Muslim Views on the 14th Century Plague, Known as Black Death

- The Destruction and Devastation Caused by the Black Death

- Reform and Relearn: How the Black Death Shaped the Renaissance

- The Black Death and the Transformation of the West

- Black Death: The History of How It Began, the Symptoms, and More

- What Caused the Black Death?

- How Did the Black Death Affect European Societies of the Mid-Fourteenth Century?

- How the Black Death Greatly Improved the European Society?

- How the Black Death Left a Lasting Impression in the Medieval Society?

- What Is the Black Death Called Now?

- How the Justinian Plague Paved the Way to the Black Death?

- How Different Were the Christian and Muslim Responses to the Black Death?

- Was the Black Death the Largest Disaster of European History?

- What Was More Significant to Europe: the Black Death or the Peasants Revolt?

- Why Did the Black Death Kill So Many People?

- Will HIV and Aids Be the Black Death of the Twenty-First Century?

- Is the Black Death Still Alive?

- How Did the Black Death Spread So Quickly?

- Who Discovered the Cure for the Black Death?

- Is There a Vaccine for the Black Death?

- What Was the Chance of Surviving the Black Death?

- Did Anyone Recover from the Black Death?

- What Was It like Living during the Black Death?

- How Is the Black Plague Similar to COVID-19?

- In What Country Is the Black Death Believed to Have Started?

- What Were the Positives of the Black Death?

- Who Was Affected the Most by the Black Death?

- Which Country Was Hit Hardest by the Black Death?

- Are Some People Immune to the Black Death?

- Which Countries Were Not Affected by the Black Death?

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, March 2). 83 Black Death Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/black-death-essay-topics/

"83 Black Death Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 2 Mar. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/black-death-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2024) '83 Black Death Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 2 March.

IvyPanda . 2024. "83 Black Death Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/black-death-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "83 Black Death Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/black-death-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "83 Black Death Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/black-death-essay-topics/.

- Pandemic Ideas

- Natural Disaster Topics

- European History Essay Titles

- Ancient History Topics

- Demographics Topics

- World History Topics

- Disease Questions

- Hygiene Essay Topics

- Influenza Topics

- Vaccination Research Topics

- Communicable Disease Research Topics

- Antibiotic Ideas

- Death Titles

- Illness Research Topics

- Pneumonia Questions

Baltimore bridge collapse: What happened and what is the death toll?

What is the death toll, when did the baltimore bridge collapse, why did the bridge collapse, who will pay for the damage and how much will the bridge cost.

HOW LONG WILL IT TAKE TO REBUILD THE BRIDGE?

What ship hit the baltimore bridge, what do we know about the bridge that collapsed.

HOW WILL THE BRIDGE COLLAPSE IMPACT THE BALTIMORE PORT?

Get weekly news and analysis on the U.S. elections and how it matters to the world with the newsletter On the Campaign Trail. Sign up here.

Writing by Lisa Shumaker; Editing by Daniel Wallis and Bill Berkrot

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. , opens new tab

Thomson Reuters

Lisa's journalism career spans two decades, and she currently serves as the Americas Day Editor for the Global News Desk. She played a pivotal role in tracking the COVID pandemic and leading initiatives in speed, headline writing and multimedia. She has worked closely with the finance and company news teams on major stories, such as the departures of Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey and Amazon’s Jeff Bezos and significant developments at Apple, Alphabet, Facebook and Tesla. Her dedication and hard work have been recognized with the 2010 Desk Editor of the Year award and a Journalist of the Year nomination in 2020. Lisa is passionate about visual and long-form storytelling. She holds a degree in both psychology and journalism from Penn State University.

Mayoral candidate murdered in Mexico amid rising political violence

A ruling party mayoral candidate was shot dead on Monday in central Mexico during an event on the first day of her campaign, despite having requested security protection from authorities and receiving no response.

Lawsuit accuses Portland officer of Black man’s wrongful death

A federal lawsuit has been filed against the Portland officer accused of fatally shooting Immanueal “Manny” Clark two years ago. The complaint was filed in the U.S. District Court of Oregon and accuses Officer Christopher Sathoff of using excessive force , causing a wrongful death and negligence after the 30-year-old Black man was allegedly not provided medical care for 26 minutes after being shot in the back by a semiautomatic rifle.

“He’s gonna get justice for what happened to him because he shouldn’t be dead,” Rhoshelle Clark told KOIN 6 News on Saturday at a vigil held in her son’s honor. “My son was only 30 years old… They need to change something. My son, he didn’t deserve this,” she added. In September 2023, a grand jury determined that Sathoff’s use of deadly force was not criminal.

The tragedy unfolded as police were responding to a robbery call on Nov. 19 at a SuperDeluxe restaurant off Southeast Powell Boulevard around 12:30 a.m. A car matching the description of the alleged assailants, who were described as three to four white men , was reportedly observed driving recklessly nearby, which led police to trail their sedan and to make a high-risk stop when the car pulled into a church parking lot. Clark-Johnson was standing outside along the driver's side door when he began to run.

“Officer Sathoff saw Mr. Clark-Johnson as he ran from the vehicle and believed he was witnessing Mr. Clark-Johnson attempting to access a firearm and that he and his fellow law enforcement officers were about to be shot. In that moment, Officer Sathoff fired three rounds from his rifle. One round struck Mr. Clark-Johnson in the lower back,” read a memorandum when grand jury transcripts were released to the public. He died two days after being injured.

Investigators later determined that the young man was unarmed and that he and the others, a Black man, a white man and a white woman, were not the suspects involved in the robbery. Though authorities did not explain why the passengers fled, it was determined that the vehicle they were occupying was reported stolen and that Clark-Johnson had several active warrants for his arrest.

Clark hopes the federal lawsuit will effect changes in local laws.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The effects of the Black Death were many and varied. Trade suffered for a time, and wars were temporarily abandoned. Many labourers died, which devastated families through lost means of survival and caused personal suffering; landowners who used labourers as tenant farmers were also affected. The labour shortage caused landowners to substitute wages or money rents in place of labour services ...

The Black Death had far reaching social impacts on the people who lived during the fourteenth century. An obvious social impact of the plague is the fact that the Black Death led to a significant reduction in the human population of the affected areas. This had extensive effects on all aspects of life, including the social and political ...

The outbreak of plague in Europe between 1347-1352 - known as the Black Death - completely changed the world of medieval Europe. Severe depopulation upset the socio-economic feudal system of the time but the experience of the plague itself affected every aspect of people's lives. Disease on an epidemic scale was simply part of life in the ...

The Black Death was a devastating global epidemic of bubonic plague that struck Europe and Asia in the mid-1300s. Explore the facts of the plague, the symptoms it caused and how millions died from it.

The Black Death was a plague pandemic that devastated medieval Europe from 1347 to 1352. The Black Death killed an estimated 25-30 million people. ... France, Spain, Britain, and Ireland, which all witnessed its awful effects. Spreading like wildfire, there were plague outbreaks in Germany, Scandinavia, the Baltic states, and Russia through ...

The Black Death had profound effects on art and literature. After 1350, ... "Before and After the Black Death: Money, Prices, and Wages in Fourteenth-Century England," Working Papers munro-04-04, University of Toronto, Department of Economics This page was last edited on 26 March 2024, at 17:57 (UTC). Text is available under the Creative ...

bubonic. plague in the mid-14th century, an event more commonly known today as the Black Death. In a passage from his book titled The Decameron, Florence, Italy resident Giovani Boccaccio described the Black Death, which reached Florence in 1348: It first betrayed itself by the emergence of certain tumors in the groin or the armpits, some of ...

Black Death: The lasting impact. By Professor Tom James. Last updated 2011-02-17. The long term effects of the Black Death were devastating and far reaching. Agriculture, religion, economics and ...

The Black Death radically disrupted society, but did the social, political and religious upheaval created by the plague contribute to the Renaissance? Some historians say yes. With so much land readily available to survivors, the rigid hierarchical structure that marked pre-plague society became more fluid. The Medici family, important patrons ...

The Black Death. The Black Death was an epidemic that killed upward of one-third of the population of Eu-. rope between 1346 and 1353 (more on proportional mortality below). The precise speci-. cation of the time span, particularly the end dates, varies by a year or so, depending on. the source.

Boccaccio's novel Decameron. fers a description of symptoms, and such is the state of Black Death that we are dependent upon a work of fiction as much as anything else. apparent spread of the Black Death along shipping routes is congruent plague, because the black rat is a good climber and would have gained.

The Black Death was the second pandemic of bubonic plague and the most devastating pandemic in world history. It was a descendant of the ancient plague that had afflicted Rome, from 541 to 549 CE, during the time of emperor Justinian. The bubonic plague, caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, persisted for centuries in wild rodent colonies in Central Asia and, somewhere in the early 1300s ...

other indirect long-run effects of the Black Death are associated with the growth of Europe relative to the rest of the world, especially Asia and the Middle East ... The Black Death of the mid-14th century began the Second Pandemic which continued until the early 18th century. The late 19th century plague outbreak is referred to as the Third ...

Elites successfully reclaimed a greater share of wealth and income, hierarchies ossified, and laborers' power diminished. Simply stating that English society was changed by the Black Death not only discounts the people who did the changing, but also ignores the insufficiencies of the changes they produced. The Rochester chronicler raised the ...

Published: Mar 14, 2024. Imagine a world where a devastating disease sweeps across continents, leaving death and destruction in its wake. This was the reality of the Black Death, a plague that ravaged Europe in the 14th century and forever changed the course of history. In this essay, we will explore the causes, effects, and lasting impact of ...

IntroductionThe Black Death, also known as the Bubonic Plague, was a devastating epidemic that spread throughout Europe in the mid-14th century. ... the outbreak had a profound and lasting impact on society, economy, and culture. This essay explores the effects of the Black Death on these three aspects of life, highlighting the significant ...

The Black Death, also known as the Bubonic Plague, was one of the deadliest pandemics in human history. It swept through Europe in the 14th century, wiping out millions of people and drastically altering the course of history. In this essay, I will explore the consequences of the Black Death and its impact on various aspects of society, economy ...

This collection of essays forms an excellent Festschrift for Professor John Hatcher, whose eclectic range of research is displayed by the volume's division into three parts: the first explores the medieval demographic system; the second charts the changing relationship between lords and peasants; and the third highlights the fortunes of trade and industry after the Black Death.

The Black Death: The Great Mortality of 1348-1350: A Brief History with Documents. Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2005. Print. Klick 9 Ben-Sasson, Haim Hillel. Trial and Achievement: Currents in Jewish History from 313. Jerusalem: Keter House, 1974. Print. Cantor, Norman F. In the Wake of the Plague: The Black Death and the World It Made.

The Black Death in Europe: Spread and Causes. The bacterium persists more commonly in the lymphatic system of the groin, armpits, and neck, and increasing pain of the bubonic elements is one of the central symptoms of the disease. The Plague (The Black Death) of 1348 and 1350.