Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

- How to Write a Discussion Section | Tips & Examples

How to Write a Discussion Section | Tips & Examples

Published on August 21, 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on July 18, 2023.

The discussion section is where you delve into the meaning, importance, and relevance of your results .

It should focus on explaining and evaluating what you found, showing how it relates to your literature review and paper or dissertation topic , and making an argument in support of your overall conclusion. It should not be a second results section.

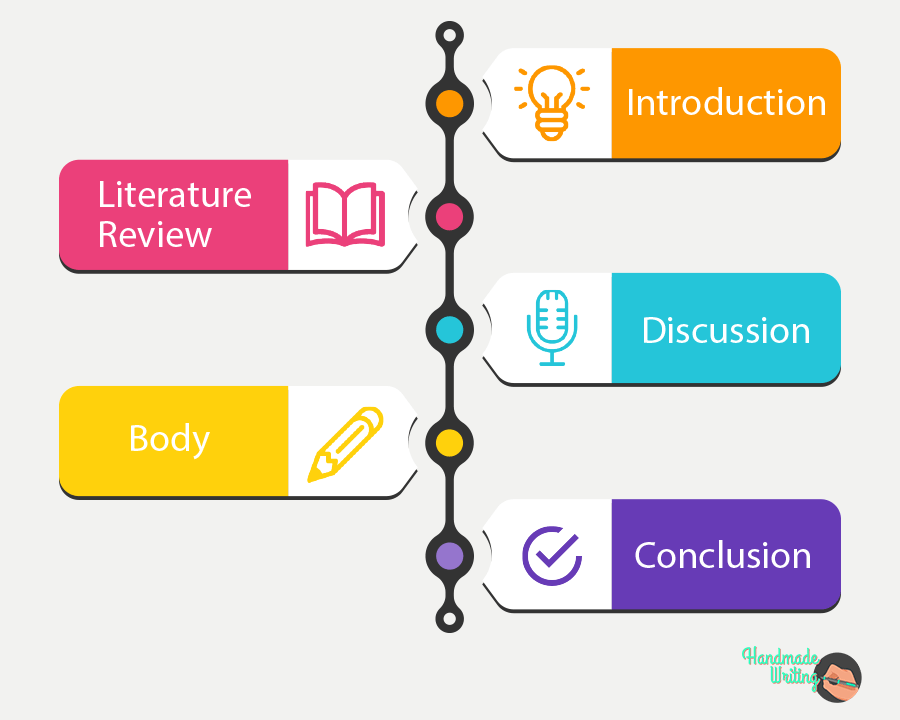

There are different ways to write this section, but you can focus your writing around these key elements:

- Summary : A brief recap of your key results

- Interpretations: What do your results mean?

- Implications: Why do your results matter?

- Limitations: What can’t your results tell us?

- Recommendations: Avenues for further studies or analyses

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What not to include in your discussion section, step 1: summarize your key findings, step 2: give your interpretations, step 3: discuss the implications, step 4: acknowledge the limitations, step 5: share your recommendations, discussion section example, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about discussion sections.

There are a few common mistakes to avoid when writing the discussion section of your paper.

- Don’t introduce new results: You should only discuss the data that you have already reported in your results section .

- Don’t make inflated claims: Avoid overinterpretation and speculation that isn’t directly supported by your data.

- Don’t undermine your research: The discussion of limitations should aim to strengthen your credibility, not emphasize weaknesses or failures.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Start this section by reiterating your research problem and concisely summarizing your major findings. To speed up the process you can use a summarizer to quickly get an overview of all important findings. Don’t just repeat all the data you have already reported—aim for a clear statement of the overall result that directly answers your main research question . This should be no more than one paragraph.

Many students struggle with the differences between a discussion section and a results section . The crux of the matter is that your results sections should present your results, and your discussion section should subjectively evaluate them. Try not to blend elements of these two sections, in order to keep your paper sharp.

- The results indicate that…

- The study demonstrates a correlation between…

- This analysis supports the theory that…

- The data suggest that…

The meaning of your results may seem obvious to you, but it’s important to spell out their significance for your reader, showing exactly how they answer your research question.

The form of your interpretations will depend on the type of research, but some typical approaches to interpreting the data include:

- Identifying correlations , patterns, and relationships among the data

- Discussing whether the results met your expectations or supported your hypotheses

- Contextualizing your findings within previous research and theory

- Explaining unexpected results and evaluating their significance

- Considering possible alternative explanations and making an argument for your position

You can organize your discussion around key themes, hypotheses, or research questions, following the same structure as your results section. Alternatively, you can also begin by highlighting the most significant or unexpected results.

- In line with the hypothesis…

- Contrary to the hypothesized association…

- The results contradict the claims of Smith (2022) that…

- The results might suggest that x . However, based on the findings of similar studies, a more plausible explanation is y .

As well as giving your own interpretations, make sure to relate your results back to the scholarly work that you surveyed in the literature review . The discussion should show how your findings fit with existing knowledge, what new insights they contribute, and what consequences they have for theory or practice.

Ask yourself these questions:

- Do your results support or challenge existing theories? If they support existing theories, what new information do they contribute? If they challenge existing theories, why do you think that is?

- Are there any practical implications?

Your overall aim is to show the reader exactly what your research has contributed, and why they should care.

- These results build on existing evidence of…

- The results do not fit with the theory that…

- The experiment provides a new insight into the relationship between…

- These results should be taken into account when considering how to…

- The data contribute a clearer understanding of…

- While previous research has focused on x , these results demonstrate that y .

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Even the best research has its limitations. Acknowledging these is important to demonstrate your credibility. Limitations aren’t about listing your errors, but about providing an accurate picture of what can and cannot be concluded from your study.

Limitations might be due to your overall research design, specific methodological choices , or unanticipated obstacles that emerged during your research process.

Here are a few common possibilities:

- If your sample size was small or limited to a specific group of people, explain how generalizability is limited.

- If you encountered problems when gathering or analyzing data, explain how these influenced the results.

- If there are potential confounding variables that you were unable to control, acknowledge the effect these may have had.

After noting the limitations, you can reiterate why the results are nonetheless valid for the purpose of answering your research question.

- The generalizability of the results is limited by…

- The reliability of these data is impacted by…

- Due to the lack of data on x , the results cannot confirm…

- The methodological choices were constrained by…

- It is beyond the scope of this study to…

Based on the discussion of your results, you can make recommendations for practical implementation or further research. Sometimes, the recommendations are saved for the conclusion .

Suggestions for further research can lead directly from the limitations. Don’t just state that more studies should be done—give concrete ideas for how future work can build on areas that your own research was unable to address.

- Further research is needed to establish…

- Future studies should take into account…

- Avenues for future research include…

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Anchoring bias

- Halo effect

- The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon

- The placebo effect

- Nonresponse bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

In the discussion , you explore the meaning and relevance of your research results , explaining how they fit with existing research and theory. Discuss:

- Your interpretations : what do the results tell us?

- The implications : why do the results matter?

- The limitation s : what can’t the results tell us?

The results chapter or section simply and objectively reports what you found, without speculating on why you found these results. The discussion interprets the meaning of the results, puts them in context, and explains why they matter.

In qualitative research , results and discussion are sometimes combined. But in quantitative research , it’s considered important to separate the objective results from your interpretation of them.

In a thesis or dissertation, the discussion is an in-depth exploration of the results, going into detail about the meaning of your findings and citing relevant sources to put them in context.

The conclusion is more shorter and more general: it concisely answers your main research question and makes recommendations based on your overall findings.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, July 18). How to Write a Discussion Section | Tips & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved March 20, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/discussion/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a results section | tips & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

The discussion section contains the results and outcomes of a study. An effective discussion informs readers what can be learned from your experiment and provides context for the results.

What makes an effective discussion?

When you’re ready to write your discussion, you’ve already introduced the purpose of your study and provided an in-depth description of the methodology. The discussion informs readers about the larger implications of your study based on the results. Highlighting these implications while not overstating the findings can be challenging, especially when you’re submitting to a journal that selects articles based on novelty or potential impact. Regardless of what journal you are submitting to, the discussion section always serves the same purpose: concluding what your study results actually mean.

A successful discussion section puts your findings in context. It should include:

- the results of your research,

- a discussion of related research, and

- a comparison between your results and initial hypothesis.

Tip: Not all journals share the same naming conventions.

You can apply the advice in this article to the conclusion, results or discussion sections of your manuscript.

Our Early Career Researcher community tells us that the conclusion is often considered the most difficult aspect of a manuscript to write. To help, this guide provides questions to ask yourself, a basic structure to model your discussion off of and examples from published manuscripts.

Questions to ask yourself:

- Was my hypothesis correct?

- If my hypothesis is partially correct or entirely different, what can be learned from the results?

- How do the conclusions reshape or add onto the existing knowledge in the field? What does previous research say about the topic?

- Why are the results important or relevant to your audience? Do they add further evidence to a scientific consensus or disprove prior studies?

- How can future research build on these observations? What are the key experiments that must be done?

- What is the “take-home” message you want your reader to leave with?

How to structure a discussion

Trying to fit a complete discussion into a single paragraph can add unnecessary stress to the writing process. If possible, you’ll want to give yourself two or three paragraphs to give the reader a comprehensive understanding of your study as a whole. Here’s one way to structure an effective discussion:

Writing Tips

While the above sections can help you brainstorm and structure your discussion, there are many common mistakes that writers revert to when having difficulties with their paper. Writing a discussion can be a delicate balance between summarizing your results, providing proper context for your research and avoiding introducing new information. Remember that your paper should be both confident and honest about the results!

- Read the journal’s guidelines on the discussion and conclusion sections. If possible, learn about the guidelines before writing the discussion to ensure you’re writing to meet their expectations.

- Begin with a clear statement of the principal findings. This will reinforce the main take-away for the reader and set up the rest of the discussion.

- Explain why the outcomes of your study are important to the reader. Discuss the implications of your findings realistically based on previous literature, highlighting both the strengths and limitations of the research.

- State whether the results prove or disprove your hypothesis. If your hypothesis was disproved, what might be the reasons?

- Introduce new or expanded ways to think about the research question. Indicate what next steps can be taken to further pursue any unresolved questions.

- If dealing with a contemporary or ongoing problem, such as climate change, discuss possible consequences if the problem is avoided.

- Be concise. Adding unnecessary detail can distract from the main findings.

Don’t

- Rewrite your abstract. Statements with “we investigated” or “we studied” generally do not belong in the discussion.

- Include new arguments or evidence not previously discussed. Necessary information and evidence should be introduced in the main body of the paper.

- Apologize. Even if your research contains significant limitations, don’t undermine your authority by including statements that doubt your methodology or execution.

- Shy away from speaking on limitations or negative results. Including limitations and negative results will give readers a complete understanding of the presented research. Potential limitations include sources of potential bias, threats to internal or external validity, barriers to implementing an intervention and other issues inherent to the study design.

- Overstate the importance of your findings. Making grand statements about how a study will fully resolve large questions can lead readers to doubt the success of the research.

Snippets of Effective Discussions:

Consumer-based actions to reduce plastic pollution in rivers: A multi-criteria decision analysis approach

Identifying reliable indicators of fitness in polar bears

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write an Abstract

- How to Write Your Methods

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

How to Write a Term Paper From Start to Finish

The term paper, often regarded as the culmination of a semester's hard work, is a rite of passage for students in pursuit of higher education. Here's an interesting fact to kick things off: Did you know that the term paper's origins can be traced back to ancient Greece, where scholars like Plato and Aristotle utilized written works to explore and document their philosophical musings? Just as these great minds once wrote their thoughts on parchment, you, too, can embark on this intellectual voyage with confidence and skill.

How to Write a Term Paper: Short Description

In this article, we'll delve into the core purpose of this kind of assignment – to showcase your understanding of a subject, your research abilities, and your capacity to communicate complex ideas effectively. But it doesn't stop there. We'll also guide you in the art of creating a well-structured term paper format, a roadmap that will not only keep you on track but also ensure your ideas flow seamlessly and logically. Packed with valuable tips on writing, organization, and time management, this resource promises to equip you with the tools needed to excel in your academic writing.

Understanding What Is a Term Paper

A term paper, a crucial component of your college education, is often assigned towards the conclusion of a semester. It's a vehicle through which educators gauge your comprehension of the course content. Imagine it as a bridge between what you've learned in class and your ability to apply that knowledge to real-world topics.

For instance, in a history course, you might be asked to delve into the causes and consequences of a significant historical event, such as World War II. In a psychology class, your term paper might explore the effects of stress on mental health, or in an environmental science course, you could analyze the impact of climate change on a specific region.

Writing a term paper isn't just about summarizing facts. It requires a blend of organization, deep research, and the art of presenting your findings in a way that's both clear and analytical. This means structuring your arguments logically, citing relevant sources, and critically evaluating the information you've gathered.

For further guidance, we've prepared an insightful guide for you authored by our expert essay writer . It's brimming with practical tips and valuable insights to help you stand out in this academic endeavor and earn the recognition you deserve.

How to Start a Term Paper

Before you start, keep the guidelines for the term paper format firmly in mind. If you have any doubts, don't hesitate to reach out to your instructor for clarification before you begin your research and writing process. And remember, procrastination is your worst enemy in this endeavor. If you're aiming to produce an exceptional piece and secure a top grade, it's essential to plan ahead and allocate dedicated time each day to work on it. Now, let our term paper writing services provide you with some valuable tips to help you on your journey:

- Hone Your Topic : Start by cultivating a learning mindset that empowers you to effectively organize your thoughts. Discover how to research a topic in the section below.

- Hook Your Readers: Initiate a brainstorming session and unleash a barrage of creative ideas to captivate your audience right from the outset. Pose intriguing questions, share compelling anecdotes, offer persuasive statistics, and more.

- Craft a Concise Thesis Statement Example : If you find yourself struggling to encapsulate the main idea of your paper in just a sentence or two, it's time to revisit your initial topic and consider narrowing it down.

- Understand Style Requirements: Your work must adhere to specific formatting guidelines. Delve into details about the APA format and other pertinent regulations in the section provided.

- Delve Deeper with Research : Equipped with a clearer understanding of your objectives, dive into your subject matter with a discerning eye. Ensure that you draw from reputable and reliable sources.

- Begin Writing: Don't obsess over perfection from the get-go. Just start writing, and don't worry about initial imperfections. You can always revise or remove those early sentences later. The key is to initiate the term papers as soon as you've amassed sufficient information.

Ace your term paper with EssayPro 's expert help. Our academic professionals are here to guide you through every step, ensuring your term paper is well-researched, structured, and written to the highest standards.

Term Paper Topics

Selecting the right topic for your term paper is a critical step, one that can significantly impact your overall experience and the quality of your work. While instructors sometimes provide specific topics, there are instances when you have the freedom to choose your own. To guide you on how to write a term paper, consider the following factors when deciding on your dissertation topics :

- Relevance to Assignment Length: Begin by considering the required length of your paper. Whether it's a substantial 10-page paper or a more concise 5-page one, understanding the word count will help you determine the appropriate scope for your subject. This will inform whether your topic should be broad or more narrowly focused.

- Availability of Resources : Investigate the resources at your disposal. Check your school or community library for books and materials that can support your research. Additionally, explore online sources to ensure you have access to a variety of reference materials.

- Complexity and Clarity : Ensure you can effectively explain your chosen topic, regardless of how complex it may seem. If you encounter areas that are challenging to grasp fully, don't hesitate to seek guidance from experts or your professor. Clarity and understanding are key to producing a well-structured term paper.

- Avoiding Overused Concepts : Refrain from choosing overly trendy or overused topics. Mainstream subjects often fail to captivate the interest of your readers or instructors, as they can lead to repetitive content. Instead, opt for a unique angle or approach that adds depth to your paper.

- Manageability and Passion : While passion can drive your choice of topic, it's important to ensure that it is manageable within the given time frame and with the available resources. If necessary, consider scaling down a topic that remains intriguing and motivating to you, ensuring it aligns with your course objectives and personal interests.

Worrying About the Quality of Your Upcoming Essay?

"Being highly trained professionals, our writers can provide term paper help by creating a paper specifically tailored to your needs.

Term Paper Outline

Before embarking on the journey of writing a term paper, it's crucial to establish a well-structured outline. Be mindful of any specific formatting requirements your teacher may have in mind, as these will guide your outline's structure. Here's a basic format to help you get started:

- Cover Page: Begin with a cover page featuring your name, course number, teacher's name, and the deadline date, centered at the top.

- Abstract: Craft a concise summary of your work that informs readers about your paper's topic, its significance, and the key points you'll explore.

- Introduction: Commence your term paper introduction with a clear and compelling statement of your chosen topic. Explain why it's relevant and outline your approach to addressing it.

- Body: This section serves as the meat of academic papers, where you present the primary findings from your research. Provide detailed information about the topic to enhance the reader's understanding. Ensure you incorporate various viewpoints on the issue and conduct a thorough analysis of your research.

- Results: Share the insights and conclusions that your research has led you to. Discuss any shifts in your perspective or understanding that have occurred during the course of your project.

- Discussion: Conclude your term paper with a comprehensive summary of the topic and your findings. You can wrap up with a thought-provoking question or encourage readers to explore the subject further through their own research.

How to Write a Term Paper with 5 Steps

Before you begin your term paper, it's crucial to understand what a term paper proposal entails. This proposal serves as your way to introduce and justify your chosen topic to your instructor, and it must gain approval before you start writing the actual paper.

In your proposal, include recent studies or research related to your topic, along with proper references. Clearly explain the topic's relevance to your course, outline your objectives, and organize your ideas effectively. This helps your instructor grasp your term paper's direction. If needed, you can also seek assistance from our expert writers and buy term paper .

Draft the Abstract

The abstract is a critical element while writing a term paper, and it plays a crucial role in piquing the reader's interest. To create a captivating abstract, consider these key points from our dissertation writing service :

- Conciseness: Keep it short and to the point, around 150-250 words. No need for lengthy explanations.

- Highlight Key Elements: Summarize the problem you're addressing, your research methods, and primary findings or conclusions. For instance, if your paper discusses the impact of social media on mental health, mention your research methods and significant findings.

- Engagement: Make your abstract engaging. Use language that draws readers in. For example, if your paper explores the effects of artificial intelligence on the job market, you might begin with a question like, 'Is AI revolutionizing our work landscape, or should we prepare for the robots to take over?'

- Clarity: Avoid excessive jargon or technical terms to ensure accessibility to a wider audience.

Craft the Introduction

The introduction sets the stage for your entire term paper and should engage readers from the outset. To craft an intriguing introduction, consider these tips:

- Hook Your Audience: Start with a captivating hook, such as a thought-provoking question or a compelling statistic. For example, if your paper explores the impact of smartphone addiction, you could begin with, 'Can you remember the last time you went a whole day without checking your phone?'

- State Your Purpose: Clearly state the purpose of your paper and its relevance. If your term paper is about renewable energy's role in combating climate change, explain why this topic is essential in today's world.

- Provide a Roadmap: Briefly outline how your paper is structured. For instance, if your paper discusses the benefits of mindfulness meditation, mention that you will explore its effects on stress reduction, emotional well-being, and cognitive performance.

- Thesis Statement: Conclude your introduction with a concise thesis statement that encapsulates the central argument or message of your paper. In the case of a term paper on the impact of online education, your thesis might be: 'Online education is revolutionizing learning by providing accessibility, flexibility, and innovative teaching methods.'

Develop the Body Sections: Brainstorming Concepts and Content

Generate ideas and compose text: body sections.

The body of your term paper is where you present your research, arguments, and analysis. To generate ideas and write engaging text in the body sections, consider these strategies from our research paper writer :

- Structure Your Ideas: Organize your paper into sections or paragraphs, each addressing a specific aspect of your topic. For example, if your term paper explores the impact of social media on interpersonal relationships, you might have sections on communication patterns, privacy concerns, and emotional well-being.

- Support with Evidence: Back up your arguments with credible evidence, such as data, research findings, or expert opinions. For instance, when discussing the effects of social media on mental health, you can include statistics on social media usage and its correlation with anxiety or depression.

- Offer Diverse Perspectives: Acknowledge and explore various viewpoints on the topic. When writing about the pros and cons of genetic engineering, present both the potential benefits, like disease prevention, and the ethical concerns associated with altering human genetics.

- Use Engaging Examples: Incorporate real-life examples to illustrate your points. If your paper discusses the consequences of climate change, share specific instances of extreme weather events or environmental degradation to make the topic relatable.

- Ask Thought-Provoking Questions: Integrate questions throughout your text to engage readers and stimulate critical thinking. In a term paper on the future of artificial intelligence, you might ask, 'How will AI impact job markets and the concept of work in the coming years?'

Formulate the Conclusion

The conclusion section should provide a satisfying wrap-up of your arguments and insights. To craft a compelling term paper example conclusion, follow these steps:

- Revisit Your Thesis: Begin by restating your thesis statement. This reinforces the central message of your paper. For example, if your thesis is about the importance of biodiversity conservation, reiterate that biodiversity is crucial for ecological balance and human well-being.

- Summarize Key Points: Briefly recap the main points you've discussed in the body of your paper. For instance, if you've been exploring the impact of globalization on local economies, summarize the effects on industries, job markets, and cultural diversity.

- Emphasize Your Main Argument: Reaffirm the significance of your thesis and the overall message of your paper. Discuss why your findings are important or relevant in a broader context. If your term paper discusses the advantages of renewable energy, underscore its potential to combat climate change and reduce our reliance on fossil fuels.

- Offer a Thoughtful Reflection: Share your own reflections or insights about the topic. How has your understanding evolved during your research? Have you uncovered any unexpected findings or implications? If your paper discusses the future of space exploration, consider what it means for humanity's quest to explore the cosmos.

- End with Impact: Conclude your term paper with a powerful closing statement. You can leave the reader with a thought-provoking question, a call to action, or a reflection on the broader implications of your topic. For instance, if your paper is about the ethics of artificial intelligence, you could finish by asking, 'As AI continues to advance, what ethical considerations will guide our choices and decisions?'

Edit and Enhance the Initial Draft

After completing your initial draft, the revision and polishing phase is essential for improving your paper. Here's how to refine your work efficiently:

- Take a Break: Step back and return to your paper with a fresh perspective.

- Structure Check: Ensure your paper flows logically and transitions smoothly from the introduction to the conclusion.

- Clarity and Conciseness: Trim excess words for clarity and precision.

- Grammar and Style: Proofread for errors and ensure consistent style.

- Citations and References: Double-check your citations and reference list.

- Peer Review: Seek feedback from peers or professors for valuable insights.

- Enhance Intro and Conclusion: Make your introduction and conclusion engaging and impactful.

- Coherence Check: Ensure your arguments support your thesis consistently.

- Read Aloud: Reading your paper aloud helps identify issues.

- Final Proofread: Perform a thorough proofread to catch any remaining errors.

Term Paper Format

When formatting your term paper, consider its length and the required citation style, which depends on your research topic. Proper referencing is crucial to avoid plagiarism in academic writing. Common citation styles include APA and MLA.

If unsure how to cite term paper for social sciences, use the APA format, including the author's name, book title, publication year, publisher, and location when citing a book.

For liberal arts and humanities, MLA is common, requiring the publication name, date, and location for referencing.

Adhering to the appropriate term paper format and citation style ensures an organized and academically sound paper. Follow your instructor's guidelines for a polished and successful paper.

Term Paper Example

To access our term paper example, simply click the button below.

The timeline of events from 1776 to 1861, that, in the end, prompted the American Civil War, describes and relates to a number of subjects modern historians acknowledge as the origins and causes of the Civil War. In fact, pre-Civil War events had both long-term and short-term influences on the War—such as the election of Abraham Lincoln as the American president in 1860 that led to the Fall of Fort Sumter in April of the same year. In that period, contentions that surrounded states’ rights progressively exploded in Congress—since they were the initial events that formed after independence. Congress focused on resolving significant issues that affected the states, which led to further issues. In that order, the US’s history from 1776 to 1861 provides a rich history, as politicians brought forth dissimilarities, dissections, and tensions between the Southern US & the people of slave states, and the Northern states that were loyal to the Union. The events that unfolded from the period of 1776 to 1861 involved a series of issues because they promoted the great sectional crisis that led to political divisions and the build-up to the Civil War that made the North and the South seem like distinctive and timeless regions that predated the crisis itself.

Final Thoughts

In closing, approach the task of writing term papers with determination and a positive outlook. Begin well in advance, maintain organization, and have faith in your capabilities. Don't hesitate to seek assistance if required, and express your individual perspective with confidence. You're more than capable of succeeding in this endeavor!

Need a Winning Hand in Academia?

Arm yourself with our custom-crafted academic papers that are sharper than a well-honed pencil! Order now and conquer your academic challenges with style!

What is the Difference between a Term Paper and a Research Paper?

What is the fastest way to write a term paper, related articles.

.webp)

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 8. The Discussion

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The purpose of the discussion section is to interpret and describe the significance of your findings in relation to what was already known about the research problem being investigated and to explain any new understanding or insights that emerged as a result of your research. The discussion will always connect to the introduction by way of the research questions or hypotheses you posed and the literature you reviewed, but the discussion does not simply repeat or rearrange the first parts of your paper; the discussion clearly explains how your study advanced the reader's understanding of the research problem from where you left them at the end of your review of prior research.

Annesley, Thomas M. “The Discussion Section: Your Closing Argument.” Clinical Chemistry 56 (November 2010): 1671-1674; Peacock, Matthew. “Communicative Moves in the Discussion Section of Research Articles.” System 30 (December 2002): 479-497.

Importance of a Good Discussion

The discussion section is often considered the most important part of your research paper because it:

- Most effectively demonstrates your ability as a researcher to think critically about an issue, to develop creative solutions to problems based upon a logical synthesis of the findings, and to formulate a deeper, more profound understanding of the research problem under investigation;

- Presents the underlying meaning of your research, notes possible implications in other areas of study, and explores possible improvements that can be made in order to further develop the concerns of your research;

- Highlights the importance of your study and how it can contribute to understanding the research problem within the field of study;

- Presents how the findings from your study revealed and helped fill gaps in the literature that had not been previously exposed or adequately described; and,

- Engages the reader in thinking critically about issues based on an evidence-based interpretation of findings; it is not governed strictly by objective reporting of information.

Annesley Thomas M. “The Discussion Section: Your Closing Argument.” Clinical Chemistry 56 (November 2010): 1671-1674; Bitchener, John and Helen Basturkmen. “Perceptions of the Difficulties of Postgraduate L2 Thesis Students Writing the Discussion Section.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 5 (January 2006): 4-18; Kretchmer, Paul. Fourteen Steps to Writing an Effective Discussion Section. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008.

Structure and Writing Style

I. General Rules

These are the general rules you should adopt when composing your discussion of the results :

- Do not be verbose or repetitive; be concise and make your points clearly

- Avoid the use of jargon or undefined technical language

- Follow a logical stream of thought; in general, interpret and discuss the significance of your findings in the same sequence you described them in your results section [a notable exception is to begin by highlighting an unexpected result or a finding that can grab the reader's attention]

- Use the present verb tense, especially for established facts; however, refer to specific works or prior studies in the past tense

- If needed, use subheadings to help organize your discussion or to categorize your interpretations into themes

II. The Content

The content of the discussion section of your paper most often includes :

- Explanation of results : Comment on whether or not the results were expected for each set of findings; go into greater depth to explain findings that were unexpected or especially profound. If appropriate, note any unusual or unanticipated patterns or trends that emerged from your results and explain their meaning in relation to the research problem.

- References to previous research : Either compare your results with the findings from other studies or use the studies to support a claim. This can include re-visiting key sources already cited in your literature review section, or, save them to cite later in the discussion section if they are more important to compare with your results instead of being a part of the general literature review of prior research used to provide context and background information. Note that you can make this decision to highlight specific studies after you have begun writing the discussion section.

- Deduction : A claim for how the results can be applied more generally. For example, describing lessons learned, proposing recommendations that can help improve a situation, or highlighting best practices.

- Hypothesis : A more general claim or possible conclusion arising from the results [which may be proved or disproved in subsequent research]. This can be framed as new research questions that emerged as a consequence of your analysis.

III. Organization and Structure

Keep the following sequential points in mind as you organize and write the discussion section of your paper:

- Think of your discussion as an inverted pyramid. Organize the discussion from the general to the specific, linking your findings to the literature, then to theory, then to practice [if appropriate].

- Use the same key terms, narrative style, and verb tense [present] that you used when describing the research problem in your introduction.

- Begin by briefly re-stating the research problem you were investigating and answer all of the research questions underpinning the problem that you posed in the introduction.

- Describe the patterns, principles, and relationships shown by each major findings and place them in proper perspective. The sequence of this information is important; first state the answer, then the relevant results, then cite the work of others. If appropriate, refer the reader to a figure or table to help enhance the interpretation of the data [either within the text or as an appendix].

- Regardless of where it's mentioned, a good discussion section includes analysis of any unexpected findings. This part of the discussion should begin with a description of the unanticipated finding, followed by a brief interpretation as to why you believe it appeared and, if necessary, its possible significance in relation to the overall study. If more than one unexpected finding emerged during the study, describe each of them in the order they appeared as you gathered or analyzed the data. As noted, the exception to discussing findings in the same order you described them in the results section would be to begin by highlighting the implications of a particularly unexpected or significant finding that emerged from the study, followed by a discussion of the remaining findings.

- Before concluding the discussion, identify potential limitations and weaknesses if you do not plan to do so in the conclusion of the paper. Comment on their relative importance in relation to your overall interpretation of the results and, if necessary, note how they may affect the validity of your findings. Avoid using an apologetic tone; however, be honest and self-critical [e.g., in retrospect, had you included a particular question in a survey instrument, additional data could have been revealed].

- The discussion section should end with a concise summary of the principal implications of the findings regardless of their significance. Give a brief explanation about why you believe the findings and conclusions of your study are important and how they support broader knowledge or understanding of the research problem. This can be followed by any recommendations for further research. However, do not offer recommendations which could have been easily addressed within the study. This would demonstrate to the reader that you have inadequately examined and interpreted the data.

IV. Overall Objectives

The objectives of your discussion section should include the following: I. Reiterate the Research Problem/State the Major Findings

Briefly reiterate the research problem or problems you are investigating and the methods you used to investigate them, then move quickly to describe the major findings of the study. You should write a direct, declarative, and succinct proclamation of the study results, usually in one paragraph.

II. Explain the Meaning of the Findings and Why They are Important

No one has thought as long and hard about your study as you have. Systematically explain the underlying meaning of your findings and state why you believe they are significant. After reading the discussion section, you want the reader to think critically about the results and why they are important. You don’t want to force the reader to go through the paper multiple times to figure out what it all means. If applicable, begin this part of the section by repeating what you consider to be your most significant or unanticipated finding first, then systematically review each finding. Otherwise, follow the general order you reported the findings presented in the results section.

III. Relate the Findings to Similar Studies

No study in the social sciences is so novel or possesses such a restricted focus that it has absolutely no relation to previously published research. The discussion section should relate your results to those found in other studies, particularly if questions raised from prior studies served as the motivation for your research. This is important because comparing and contrasting the findings of other studies helps to support the overall importance of your results and it highlights how and in what ways your study differs from other research about the topic. Note that any significant or unanticipated finding is often because there was no prior research to indicate the finding could occur. If there is prior research to indicate this, you need to explain why it was significant or unanticipated. IV. Consider Alternative Explanations of the Findings

It is important to remember that the purpose of research in the social sciences is to discover and not to prove . When writing the discussion section, you should carefully consider all possible explanations for the study results, rather than just those that fit your hypothesis or prior assumptions and biases. This is especially important when describing the discovery of significant or unanticipated findings.

V. Acknowledge the Study’s Limitations

It is far better for you to identify and acknowledge your study’s limitations than to have them pointed out by your professor! Note any unanswered questions or issues your study could not address and describe the generalizability of your results to other situations. If a limitation is applicable to the method chosen to gather information, then describe in detail the problems you encountered and why. VI. Make Suggestions for Further Research

You may choose to conclude the discussion section by making suggestions for further research [as opposed to offering suggestions in the conclusion of your paper]. Although your study can offer important insights about the research problem, this is where you can address other questions related to the problem that remain unanswered or highlight hidden issues that were revealed as a result of conducting your research. You should frame your suggestions by linking the need for further research to the limitations of your study [e.g., in future studies, the survey instrument should include more questions that ask..."] or linking to critical issues revealed from the data that were not considered initially in your research.

NOTE: Besides the literature review section, the preponderance of references to sources is usually found in the discussion section . A few historical references may be helpful for perspective, but most of the references should be relatively recent and included to aid in the interpretation of your results, to support the significance of a finding, and/or to place a finding within a particular context. If a study that you cited does not support your findings, don't ignore it--clearly explain why your research findings differ from theirs.

V. Problems to Avoid

- Do not waste time restating your results . Should you need to remind the reader of a finding to be discussed, use "bridge sentences" that relate the result to the interpretation. An example would be: “In the case of determining available housing to single women with children in rural areas of Texas, the findings suggest that access to good schools is important...," then move on to further explaining this finding and its implications.

- As noted, recommendations for further research can be included in either the discussion or conclusion of your paper, but do not repeat your recommendations in the both sections. Think about the overall narrative flow of your paper to determine where best to locate this information. However, if your findings raise a lot of new questions or issues, consider including suggestions for further research in the discussion section.

- Do not introduce new results in the discussion section. Be wary of mistaking the reiteration of a specific finding for an interpretation because it may confuse the reader. The description of findings [results section] and the interpretation of their significance [discussion section] should be distinct parts of your paper. If you choose to combine the results section and the discussion section into a single narrative, you must be clear in how you report the information discovered and your own interpretation of each finding. This approach is not recommended if you lack experience writing college-level research papers.

- Use of the first person pronoun is generally acceptable. Using first person singular pronouns can help emphasize a point or illustrate a contrasting finding. However, keep in mind that too much use of the first person can actually distract the reader from the main points [i.e., I know you're telling me this--just tell me!].

Analyzing vs. Summarizing. Department of English Writing Guide. George Mason University; Discussion. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Hess, Dean R. "How to Write an Effective Discussion." Respiratory Care 49 (October 2004); Kretchmer, Paul. Fourteen Steps to Writing to Writing an Effective Discussion Section. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008; The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sauaia, A. et al. "The Anatomy of an Article: The Discussion Section: "How Does the Article I Read Today Change What I Will Recommend to my Patients Tomorrow?” The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 74 (June 2013): 1599-1602; Research Limitations & Future Research . Lund Research Ltd., 2012; Summary: Using it Wisely. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Schafer, Mickey S. Writing the Discussion. Writing in Psychology course syllabus. University of Florida; Yellin, Linda L. A Sociology Writer's Guide . Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 2009.

Writing Tip

Don’t Over-Interpret the Results!

Interpretation is a subjective exercise. As such, you should always approach the selection and interpretation of your findings introspectively and to think critically about the possibility of judgmental biases unintentionally entering into discussions about the significance of your work. With this in mind, be careful that you do not read more into the findings than can be supported by the evidence you have gathered. Remember that the data are the data: nothing more, nothing less.

MacCoun, Robert J. "Biases in the Interpretation and Use of Research Results." Annual Review of Psychology 49 (February 1998): 259-287; Ward, Paulet al, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Expertise . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Write Two Results Sections!

One of the most common mistakes that you can make when discussing the results of your study is to present a superficial interpretation of the findings that more or less re-states the results section of your paper. Obviously, you must refer to your results when discussing them, but focus on the interpretation of those results and their significance in relation to the research problem, not the data itself.

Azar, Beth. "Discussing Your Findings." American Psychological Association gradPSYCH Magazine (January 2006).

Yet Another Writing Tip

Avoid Unwarranted Speculation!

The discussion section should remain focused on the findings of your study. For example, if the purpose of your research was to measure the impact of foreign aid on increasing access to education among disadvantaged children in Bangladesh, it would not be appropriate to speculate about how your findings might apply to populations in other countries without drawing from existing studies to support your claim or if analysis of other countries was not a part of your original research design. If you feel compelled to speculate, do so in the form of describing possible implications or explaining possible impacts. Be certain that you clearly identify your comments as speculation or as a suggestion for where further research is needed. Sometimes your professor will encourage you to expand your discussion of the results in this way, while others don’t care what your opinion is beyond your effort to interpret the data in relation to the research problem.

- << Previous: Using Non-Textual Elements

- Next: Limitations of the Study >>

- Last Updated: Mar 21, 2024 9:59 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

- Research Papers

Everything You Need to Know to Write an A+ Term Paper

Last Updated: March 4, 2024 Fact Checked

Sample Term Papers

Researching & outlining.

- Drafting Your Paper

- Revising Your Paper

Expert Q&A

This article was co-authored by Matthew Snipp, PhD and by wikiHow staff writer, Raven Minyard, BA . C. Matthew Snipp is the Burnet C. and Mildred Finley Wohlford Professor of Humanities and Sciences in the Department of Sociology at Stanford University. He is also the Director for the Institute for Research in the Social Science’s Secure Data Center. He has been a Research Fellow at the U.S. Bureau of the Census and a Fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences. He has published 3 books and over 70 articles and book chapters on demography, economic development, poverty and unemployment. He is also currently serving on the National Institute of Child Health and Development’s Population Science Subcommittee. He holds a Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of Wisconsin—Madison. There are 13 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 2,225,015 times.

A term paper is a written assignment given to students at the end of a course to gauge their understanding of the material. Term papers typically count for a good percentage of your overall grade, so of course, you’ll want to write the best paper possible. Luckily, we’ve got you covered. In this article, we’ll teach you everything you need to know to write an A+ term paper, from researching and outlining to drafting and revising.

Quick Steps to Write a Term Paper

- Hook your readers with an interesting and informative intro paragraph. State your thesis and your main points.

- Support your thesis by providing quotes and evidence that back your claim in your body paragraphs.

- Summarize your main points and leave your readers with a thought-provoking question in your conclusion.

- Think of your term paper as the bridge between what you’ve learned in class and how you apply that knowledge to real-world topics.

- For example, a history term paper may require you to explore the consequences of a significant historical event, like the Civil War. An environmental science class, on the other hand, may have you examine the effects of climate change on a certain region.

- Your guidelines should tell you the paper’s word count and formatting style, like whether to use in-text citations or footnotes and whether to use single- or double-spacing. If these things aren’t specified, be sure to reach out to your instructor.

- Make sure your topic isn’t too broad. For example, if you want to write about Shakespeare’s work, first narrow it down to a specific play, like Macbeth , then choose something even more specific like Lady Macbeth’s role in the plot.

- If the topic is already chosen for you, explore unique angles that can set your content and information apart from the more obvious approaches many others will probably take. [3] X Research source

- Try not to have a specific outcome in mind, as this will close you off to new ideas and avenues of thinking. Rather than trying to mold your research to fit your desired outcome, allow the outcome to reflect a genuine analysis of the discoveries you made. Ask yourself questions throughout the process and be open to having your beliefs challenged.

- Reading other people's comments, opinions, and entries on a topic can often help you to refine your own, especially where they comment that "further research" is required or where they posit challenging questions but leave them unanswered.

- For example, if you’re writing a term paper about Macbeth , your primary source would be the play itself. Then, look for other research papers and analyses written by academics and scholars to understand how they interpret the text.

- For example, if you’re writing a paper about Lady Macbeth, your thesis could be something like “Shakespeare’s characterization of Lady Macbeth reveals how desire for power can control someone’s life.”

- Remember, your research and thesis development doesn’t stop here. As you continue working through both the research and writing, you may want to make changes that align with the ideas forming in your mind and the discoveries you continue to unearth.

- On the other hand, don’t keep looking for new ideas and angles for fear of feeling confined. At some point, you’re going to have to say enough is enough and make your point. You may have other opportunities to explore these questions in future studies, but for now, remember your term paper has a finite word length and an approaching due date!

- Abstract: An abstract is a concise summary of your paper that informs readers of your topic, its significance, and the key points you’ll explore. It must stand on its own and make sense without referencing outside sources or your actual paper.

- Introduction: The introduction establishes the main idea of your paper and directly states the thesis. Begin your introduction with an attention-grabbing sentence to intrigue your readers, and provide any necessary background information to establish your paper’s purpose and direction.

- Body paragraphs: Each body paragraph focuses on a different argument supporting your thesis. List specific evidence from your sources to back up your arguments. Provide detailed information about your topic to enhance your readers’ understanding. In your outline, write down the main ideas for each body paragraph and any outstanding questions or points you’re not yet sure about.

- Results: Depending on the type of term paper you’re writing, your results may be incorporated into your body paragraphs or conclusion. These are the insights that your research led you to. Here you can discuss how your perspective and understanding of your topic shifted throughout your writing process.

- Conclusion: Your conclusion summarizes your argument and findings. You may restate your thesis and major points as you wrap up your paper.

Drafting Your Term Paper

- Writing an introduction can be challenging, but don’t get too caught up on it. As you write the rest of your paper, your arguments might change and develop, so you’ll likely need to rewrite your intro at the end, anyway. Writing your intro is simply a means of getting started and you can always revise it later. [10] X Trustworthy Source PubMed Central Journal archive from the U.S. National Institutes of Health Go to source

- Be sure to define any words your readers might not understand. For example, words like “globalization” have many different meanings depending on context, and it’s important to state which ones you’ll be using as part of your introductory paragraph.

- Try to relate the subject of the essay (say, Plato’s Symposium ) to a tangentially related issue you happen to know something about (say, the growing trend of free-wheeling hookups in frat parties). Slowly bring the paragraph around to your actual subject and make a few generalizations about why this aspect of the book/subject is so fascinating and worthy of study (such as how different the expectations for physical intimacy were then compared to now).

- You can also reflect on your own experience of researching and writing your term paper. Discuss how your understanding of your topic evolved and any unexpected findings you came across.

- While peppering quotes throughout your text is a good way to help make your point, don’t overdo it. If you use too many quotes, you’re basically allowing other authors to make the point and write the paper for you. When you do use a quote, be sure to explain why it is relevant in your own words.

- Try to sort out your bibliography at the beginning of your writing process to avoid having a last-minute scramble. When you have all the information beforehand (like the source’s title, author, publication date, etc.), it’s easier to plug them into the correct format.

Revising & Finalizing Your Term Paper

- Trade in weak “to-be” verbs for stronger “action” verbs. For example: “I was writing my term paper” becomes “I wrote my term paper.”

- It’s extremely important to proofread your term paper. If your writing is full of mistakes, your instructor will assume you didn’t put much effort into your paper. If you have too many errors, your message will be lost in the confusion of trying to understand what you’ve written.

- If you add or change information to make things clearer for your readers, it’s a good idea to look over your paper one more time to catch any new typos that may have come up in the process.

- The best essays are like grass court tennis—the argument should flow in a "rally" style, building persuasively to the conclusion. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- If you get stuck, consider giving your professor a visit. Whether you're still struggling for a thesis or you want to go over your conclusion, most instructors are delighted to help and they'll remember your initiative when grading time rolls around. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- At least 2 hours for 3-5 pages.

- At least 4 hours for 8-10 pages.

- At least 6 hours for 12-15 pages.

- Double those hours if you haven't done any homework and you haven't attended class.

- For papers that are primarily research-based, add about two hours to those times (although you'll need to know how to research quickly and effectively, beyond the purview of this brief guide).

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://www.binghamton.edu/counseling/self-help/term-paper.html

- ↑ Matthew Snipp, PhD. Research Fellow, U.S. Bureau of the Census. Expert Interview. 26 March 2020.

- ↑ https://emory.libanswers.com/faq/44525

- ↑ https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/assignments/planresearchpaper/

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/the_writing_process/thesis_statement_tips.html

- ↑ https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/outline

- ↑ https://gallaudet.edu/student-success/tutorial-center/english-center/writing/guide-to-writing-introductions-and-conclusions/

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26731827

- ↑ https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/assignments/writing-an-abstract-for-your-research-paper/

- ↑ https://www.ivcc.edu/stylesite/Essay_Title.pdf

- ↑ https://www.uni-flensburg.de/fileadmin/content/institute/anglistik/dokumente/downloads/how-to-write-a-term-paper-daewes.pdf

- ↑ https://library.sacredheart.edu/c.php?g=29803&p=185937

- ↑ https://www.cornerstone.edu/blog-post/six-steps-to-really-edit-your-paper/

About This Article

If you need to write a term paper, choose your topic, then start researching that topic. Use your research to craft a thesis statement which states the main idea of your paper, then organize all of your facts into an outline that supports your thesis. Once you start writing, state your thesis in the first paragraph, then use the body of the paper to present the points that support your argument. End the paper with a strong conclusion that restates your thesis. For tips on improving your term paper through active voice, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Bill McReynolds

Apr 7, 2017

Did this article help you?

Gerard Mortera

Mar 30, 2016

Ayuba Muhammad Bello

Dec 28, 2016

Mar 24, 2016

Jera Andarino

May 11, 2016

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

How to Write the Discussion Section of a Research Paper

The discussion section of a research paper analyzes and interprets the findings, provides context, compares them with previous studies, identifies limitations, and suggests future research directions.

Updated on September 15, 2023

Structure your discussion section right, and you’ll be cited more often while doing a greater service to the scientific community. So, what actually goes into the discussion section? And how do you write it?

The discussion section of your research paper is where you let the reader know how your study is positioned in the literature, what to take away from your paper, and how your work helps them. It can also include your conclusions and suggestions for future studies.

First, we’ll define all the parts of your discussion paper, and then look into how to write a strong, effective discussion section for your paper or manuscript.

Discussion section: what is it, what it does

The discussion section comes later in your paper, following the introduction, methods, and results. The discussion sets up your study’s conclusions. Its main goals are to present, interpret, and provide a context for your results.

What is it?

The discussion section provides an analysis and interpretation of the findings, compares them with previous studies, identifies limitations, and suggests future directions for research.

This section combines information from the preceding parts of your paper into a coherent story. By this point, the reader already knows why you did your study (introduction), how you did it (methods), and what happened (results). In the discussion, you’ll help the reader connect the ideas from these sections.

Why is it necessary?

The discussion provides context and interpretations for the results. It also answers the questions posed in the introduction. While the results section describes your findings, the discussion explains what they say. This is also where you can describe the impact or implications of your research.

Adds context for your results

Most research studies aim to answer a question, replicate a finding, or address limitations in the literature. These goals are first described in the introduction. However, in the discussion section, the author can refer back to them to explain how the study's objective was achieved.

Shows what your results actually mean and real-world implications

The discussion can also describe the effect of your findings on research or practice. How are your results significant for readers, other researchers, or policymakers?

What to include in your discussion (in the correct order)

A complete and effective discussion section should at least touch on the points described below.

Summary of key findings

The discussion should begin with a brief factual summary of the results. Concisely overview the main results you obtained.

Begin with key findings with supporting evidence

Your results section described a list of findings, but what message do they send when you look at them all together?

Your findings were detailed in the results section, so there’s no need to repeat them here, but do provide at least a few highlights. This will help refresh the reader’s memory and help them focus on the big picture.

Read the first paragraph of the discussion section in this article (PDF) for an example of how to start this part of your paper. Notice how the authors break down their results and follow each description sentence with an explanation of why each finding is relevant.

State clearly and concisely

Following a clear and direct writing style is especially important in the discussion section. After all, this is where you will make some of the most impactful points in your paper. While the results section often contains technical vocabulary, such as statistical terms, the discussion section lets you describe your findings more clearly.

Interpretation of results

Once you’ve given your reader an overview of your results, you need to interpret those results. In other words, what do your results mean? Discuss the findings’ implications and significance in relation to your research question or hypothesis.

Analyze and interpret your findings

Look into your findings and explore what’s behind them or what may have caused them. If your introduction cited theories or studies that could explain your findings, use these sources as a basis to discuss your results.

For example, look at the second paragraph in the discussion section of this article on waggling honey bees. Here, the authors explore their results based on information from the literature.

Unexpected or contradictory results

Sometimes, your findings are not what you expect. Here’s where you describe this and try to find a reason for it. Could it be because of the method you used? Does it have something to do with the variables analyzed? Comparing your methods with those of other similar studies can help with this task.

Context and comparison with previous work

Refer to related studies to place your research in a larger context and the literature. Compare and contrast your findings with existing literature, highlighting similarities, differences, and/or contradictions.

How your work compares or contrasts with previous work

Studies with similar findings to yours can be cited to show the strength of your findings. Information from these studies can also be used to help explain your results. Differences between your findings and others in the literature can also be discussed here.

How to divide this section into subsections

If you have more than one objective in your study or many key findings, you can dedicate a separate section to each of these. Here’s an example of this approach. You can see that the discussion section is divided into topics and even has a separate heading for each of them.

Limitations

Many journals require you to include the limitations of your study in the discussion. Even if they don’t, there are good reasons to mention these in your paper.

Why limitations don’t have a negative connotation

A study’s limitations are points to be improved upon in future research. While some of these may be flaws in your method, many may be due to factors you couldn’t predict.

Examples include time constraints or small sample sizes. Pointing this out will help future researchers avoid or address these issues. This part of the discussion can also include any attempts you have made to reduce the impact of these limitations, as in this study .

How limitations add to a researcher's credibility

Pointing out the limitations of your study demonstrates transparency. It also shows that you know your methods well and can conduct a critical assessment of them.

Implications and significance

The final paragraph of the discussion section should contain the take-home messages for your study. It can also cite the “strong points” of your study, to contrast with the limitations section.

Restate your hypothesis

Remind the reader what your hypothesis was before you conducted the study.

How was it proven or disproven?

Identify your main findings and describe how they relate to your hypothesis.

How your results contribute to the literature

Were you able to answer your research question? Or address a gap in the literature?

Future implications of your research

Describe the impact that your results may have on the topic of study. Your results may show, for instance, that there are still limitations in the literature for future studies to address. There may be a need for studies that extend your findings in a specific way. You also may need additional research to corroborate your findings.

Sample discussion section

This fictitious example covers all the aspects discussed above. Your actual discussion section will probably be much longer, but you can read this to get an idea of everything your discussion should cover.

Our results showed that the presence of cats in a household is associated with higher levels of perceived happiness by its human occupants. These findings support our hypothesis and demonstrate the association between pet ownership and well-being.

The present findings align with those of Bao and Schreer (2016) and Hardie et al. (2023), who observed greater life satisfaction in pet owners relative to non-owners. Although the present study did not directly evaluate life satisfaction, this factor may explain the association between happiness and cat ownership observed in our sample.

Our findings must be interpreted in light of some limitations, such as the focus on cat ownership only rather than pets as a whole. This may limit the generalizability of our results.

Nevertheless, this study had several strengths. These include its strict exclusion criteria and use of a standardized assessment instrument to investigate the relationships between pets and owners. These attributes bolster the accuracy of our results and reduce the influence of confounding factors, increasing the strength of our conclusions. Future studies may examine the factors that mediate the association between pet ownership and happiness to better comprehend this phenomenon.

This brief discussion begins with a quick summary of the results and hypothesis. The next paragraph cites previous research and compares its findings to those of this study. Information from previous studies is also used to help interpret the findings. After discussing the results of the study, some limitations are pointed out. The paper also explains why these limitations may influence the interpretation of results. Then, final conclusions are drawn based on the study, and directions for future research are suggested.

How to make your discussion flow naturally

If you find writing in scientific English challenging, the discussion and conclusions are often the hardest parts of the paper to write. That’s because you’re not just listing up studies, methods, and outcomes. You’re actually expressing your thoughts and interpretations in words.

- How formal should it be?

- What words should you use, or not use?

- How do you meet strict word limits, or make it longer and more informative?

Always give it your best, but sometimes a helping hand can, well, help. Getting a professional edit can help clarify your work’s importance while improving the English used to explain it. When readers know the value of your work, they’ll cite it. We’ll assign your study to an expert editor knowledgeable in your area of research. Their work will clarify your discussion, helping it to tell your story. Find out more about AJE Editing.

Adam Goulston, PsyD, MS, MBA, MISD, ELS

Science Marketing Consultant

See our "Privacy Policy"

Ensure your structure and ideas are consistent and clearly communicated

Pair your Premium Editing with our add-on service Presubmission Review for an overall assessment of your manuscript.

- Langson Library

- Science Library

- Grunigen Medical Library

- Law Library

- Connect From Off-Campus

- Accessibility

- Gateway Study Center

Email this link

Writing a scientific paper.

- Writing a lab report

- INTRODUCTION

Writing a "good" discussion section

"discussion and conclusions checklist" from: how to write a good scientific paper. chris a. mack. spie. 2018., peer review.

- LITERATURE CITED