- Case Studies

- Teaching Guide

- Using the Open Case Studies Website

- Using the UBC Wiki

- Open Educational Resources

- Case Implementation

- Get Involved

- Process Documentation

Behaviourism

How would you solve these behaviour issues without using behaviourist techniques?

Room Profile

Non-traditional classroom with no desks and a high-risk environment with very expensive equipment and supplies.

Class Profile

- Class of 30 grade 9 students consisting of 6 girls and 24 boys.

- Because it’s a pandemic year, students don’t get their choice of electives so only 3 students actually chose this class as their elective

- 16 designations total

- 6 IEPs - ranging from needing written instructions to having to keep them at your side and a close eye on them for the safety of the student and those in the classroom

- No EA or student aide help

- 2.5 hour class every day for 10 weeks

Description of Behaviours

Every other word uttered by students is a swear and they are incredibly disrespectful toward themselves, each other, the teacher, and the physical environment. One student is so keen on being in the room that they won’t let the teacher talk without interrupting with questions. Three other students keep talking to their neighbours and distracting them regardless of how many times the teacher waits for silence (which ends up about 25 minutes the first time on the first day). Two students refuse to put their phones away claiming they can be on them because of their IEPs; however, they cannot. One student won’t sit down and is physically throwing things around the classroom. This student’s IEP specifies that the teacher has to make sure they are seated very close to them and not to let the student “get away” with anything.

The teacher works on respectful language and discusses code switching, specifically how the classroom has different norms and behavioural expectations than outside of school and students must “switch” to adhere to these expectations when in the classroom. Emails are sent home about language use. The teacher also sits the class down for a minimum of 30 minutes each day to discuss appropriate behaviour and language in class (this continues for the first three weeks of the quarter as behaviour does not change enough to do any curriculum work). The teacher has the class come up with the following list of disciplinary measures increasing in severity:

- 1st offense: Verbal warning

- 2nd offense: Verbal warning and student moved from current location

- 3rd offense: Student sent outside of classroom

- 4th offense: Student sent outside and email home

- 5th offense: Student sent to office and email home

- 6th offense: Student removed from class

The space is split into two parts, the classroom area and performance area. Students are not to use the performance area due to the pandemic and cleaning load of the janitors. The teacher puts tape lines on the carpet to distinguish the classroom space, but these are ignored. Emails are sent home detailing necessary classroom boundaries for the health and safety of students in the space. Chairs are put up above the lines with signs on them noting the boundaries, but these are also ignored. Emails are again sent home and administration is notified. Despite all these efforts, the behaviour persists. .

Second week

The principal comes in to talk to the class. The behaviour continues, but the teacher notes that the use of language has gotten better.

The teacher pulls five senior students out of their classes for one day and divides the class into separate, carefully curated, groups. The teacher also arranges for a peer-tutor to come work with one student, and another is sent to the support room. Two other students are sent to the construction shop to work with the shop teacher. Everyone is successful for one hour. However, the behaviour continues when everyone is back in the classroom together. The teacher removes the students from the classroom and goes into library space with the librarian and vice principal present.

Fourth week

The Library is booked this week so the class is moved primarily outside, as it is safer to be outside during the pandemic anyway. Little to no actual classwork has happened so far.

Traditional classroom with table groups, reading area, teacher desk, and three computer stations

- Class of 30 grade 6 students consisting of 10 girls and 20 boys

- 10 designations total

- 6 IEPs - ranging from needing written instructions to having to keep them at your side and a close eye on them for the safety of the student and others in the classroom

Students exhibit a wide array of disruptive behaviours. The majority of the class is running around, yelling at each other, using disrespectful language or derogatory terms to address one another, and throwing papers and materials across the room. When the teacher tries to address the students, only a handful pay attention and listen for instructions. When the teacher asks for silence, some of the students keep talking to each other, while others keep interrupting the teacher and moving around the classroom. One student with a designation refuses to stop playing games on his phone, claiming he can use it because of his IEP accommodations; however, this student’s IEP specifies that the student should be seated very close to the teacher and to not let him “get away with anything.” Despite the teacher’s efforts, the majority of students won't remain silent or still, mocking the teacher whenever they speak. It takes the teacher 25 minutes to get the students' attention and for them to be relatively quiet. The lesson is not effective since most students tend to be distracted and off-task.

The teacher works on respectful language and discusses code switching, specifically how the classroom has different norms and behavioural expectations than outside of school and students must “switch” to adhere to these expectations when in the classroom. Emails are sent home about language use and respectful behaviour. The teacher also sits the class down for a minimum of 20 minutes each day to discuss appropriate behaviour and language in class (this continues for the first three weeks of the quarter as behaviour does not change enough to do any curriculum work). The teacher has the class come up with the following list of disciplinary measures increasing in severity:

Students are not to use the computers due to the pandemic and cleaning load of the janitors. The teacher puts tape lines on the carpet to distinguish the classroom space, but these are ignored. Emails are sent home detailing necessary classroom boundaries for the health and safety of students in the space. Chairs are put up above the lines with signs on them noting the boundaries, but these are also ignored. Emails are again sent home and administration is notified. Despite all these efforts, the behaviour persists.

The teacher pulls five students out of their classes for one day and divides the class into separate, carefully curated, groups. The teacher also arranges for a peer-tutor to come work with one student, and another is sent to the support room. Two other students are sent to the library to work with the librarian. Everyone is successful for one hour. However, the behaviour continues when everyone is back in the classroom together.

The teacher decides to move the class outside as it is safer to be outside during the pandemic anyway. Little to no actual classwork has happened so far.

Behaviourism on Station 12?

Congratulations Earthling!

As one of Earth’s top teacher candidates, you have been selected to take a tour of Station 12, one of the most advanced elementary schools on Mars! As your friendly Martian tour guide, I’ll be showing you how our education system has advanced to be one of the best in the galaxy! In honesty, our progress is all thanks to you, and your fellow Earth-dwellers. You see, about 50 years ago, we received a time capsule from Earth containing tons of interesting information, sounds, and images! In addition to learning about Justin Bieber, apparently one of Earth’s greatest poets, we learned all about Behaviorism and the perils of dehumanizing our young learners through rewards and punishments. Anyways, that’s enough jibber-jabber, where are my Martian-manners! Let’s go check out Station 12 and you can see for yourself!

As you enter Station 12, you immediately notice the absence of any shiny trophy cases that commonly adorn the lobbies of schools on Earth. You think to yourself: “I guess Martians truly don’t offer rewards for certain behaviours, at least in terms of athletics.” Noticing your curiosity, your friendly Martian turns to you and says, “We don’t use any objective forms of rewards or punishments in our classrooms! We understand that if a student receives a reward or punishment for their behaviour, they may not develop intrinsic motivation for learning.”

As you continue to walk through the hallways of Station 12, you get glimpses of different classroom environments and teaching practices. Interestingly, you don’t notice any signs of grades, stars, or points systems being used in the classrooms. On the surface, the students also seem to be completely engaged and intrinsically motivated.

As you round the next corner, your tour guide invites you into a classroom where students are just about to return from recess and continue working on their independent research projects. As the students enter the classroom on time, the teacher is giving them a big, gleaming smile. After the students are settled, you begin walking around the classroom and learning about their projects. You discover that one student is learning about Earth and another about the gravity on the Moon. The students are at different stages of their projects and some are still deciding on their topics. You overhear one student inform the teacher that they have decided to study the constellations closest to Mars. As an avid astronomer, the teacher excitedly says, “I think that is a wonderful choice!” Just then, a student enters the classroom 10 minutes late from recess. The teacher lets out a quick “hmm” and shows the slightest suggestion of a frown. Your Martian tour guide turns to you and says, “Did you see that!? No detention for arriving late to the classroom!” Before you can respond, you notice another student beginning to get distracted from their work. You watch as the teacher walks over to a student sitting beside them and, with a warm smile, says, “Great job! I’m so happy you are working hard today and staying focused. I am so proud!” Interestingly, you notice the distracted student begin working again. Another student approaches the teacher and says, “I’ve decided to change my topic to the gravitational pull of the Moon!” Hearing this, the teacher says, “That's a clever idea!” and offers them a quick wink and a warm smile as the student bounces away, seemingly happy with the interaction. Just as you’re about to leave the classroom, you watch as another student explains to the teacher that they have decided to research Emily Carr and the emotions her paintings surface in both humans and Martians. Just as you exit the classroom, you watch the teacher scrunch their noise ever so slightly and say, “Oh. Okay. That’s a good choice,” before immediately moving their attention to another student.

As you leave the school, your Martian tour guide turns to you and says, “So!? What do you think? Pretty impressive, eh? We learned from the time capsule and don’t use any forms of rewards or punishments!” Before you can respond, you are awoken by one of your friends. You’re in EPSE 308 and it’s your turn to discuss your perspectives on Behaviourism. Good luck, Earth-dweller!

Possible Discussion Questions

- In the classrooms on Station 12, you were informed that there were no objective forms of rewards or punishments for students' behaviour. Did you notice any subtle (maybe even unconscious) forms of behaviourism?

- As a teacher candidate, you may be motivated to cultivate a classroom environment that fits your needs and values as a teacher. In this case study, the teacher did this by encouraging students to attend class on time, stay engaged in their work, and pick topics that they themselves deemed worthy. Are these subtle forms of behaviourism more or less harmful, compared to more tangible and objective rewards and punishments? Explain your reasoning.

- As a future teacher, how might you become more aware of your subconscious values and goals for your classroom? How will you manage them in your classroom?

- What do you see as the pros and cons of behaviourism?

Dear Colleague

I can’t imagine you have an answer to this question, but you seem to have been thinking a lot about how to motivate your students and when it comes to this, I’m at a total loss! I thought I had it all figured out, but no – my plan to motivate my students has totally backfired. Help!

I’m teaching seventh grade language arts for the first time this year, and one goal of mine going into this term was to encourage my students to become independent readers. Well, lucky for me, the school librarian, Ms. Daniels, had a program set up this year to do just that! You see, there’s a new book coming out at the end of the year – it’s the latest in a series of young adult novels that’s all the rage right now. Vampires, wizards, a dystopian world – this series has got it all. Anyway, the school librarian KNOWS that this book will be a hot commodity the moment it’s released. When the last in the series came out, she had about fifty holds on it the second she entered it into the library catalogue!

Ms. Daniels devised a system to encourage independent reading. It’s simple: each time a student reads a book from the library – any book – they fill out a worksheet to reflect on it and show they’ve read it. It's just a few questions, asking for a brief plot summary, something they liked about the book, something it made them think about – things like that. Anyway, each time a student hands in a worksheet on a book they’ve read, they get a point, or points, depending on the length of the book. You get one point if you read a book that’s at least 100 pages, two if you read a book that’s at least 200 pages, three if it’s more than 300 pages – you get the idea. The student in the school who has the most points at the end of the year wins a copy of that new young adult novel that everyone wants. It’s bound to fly off the shelves and be sold out for weeks, so they’ll be one of the first to get it!

Well, since I’m teaching language arts this year, I thought I’d supplement Ms. Daniels' competition with some extra motivation – to really get my students wanting to read. After all, not every student in my class is a fan of this series. So, I told my class that for every reading worksheet they hand in to the librarian, they'll also get a bonus mark they can add to their final assignment for the year. It would never change their grade significantly, but hopefully just enough to get them reading. Simple, right?

It all seemed to be going smoothly at first. In the beginning, Bilal was the student who was gaining the most points. He's a high achiever and has always been an avid reader, so that wasn't surprising. But then I had some unexpected runner-ups. A few students who were otherwise struggling in my class, Andy and Sobiga, started gaining more points, and fast! They were giving Bilal a run for his money.

At first, I was thrilled! But that all changed on Friday afternoon. Bilal and Andy had been close friends all term, but on Friday during class, they seemed to have a falling out. Then Bilal lingered after the bell to talk to me. Bilal declared: "Andy is cheating!" When I asked him what he meant, he explained: "He doesn't actually READ any books! He just looks at summaries online to fill out those worksheets!"

To add to my stress, I heard the next day that students in the neighbouring seventh grade class, taught by Mr. Chu, were complaining that my students had an unfair advantage over them because of the bonus marks I had promised. Mr. Chu has even gotten several calls from parents who felt that my students have an advantage over theirs.

As you can see, my plan to encourage reading has gone totally awry! What should I do now? And, most importantly, how can I motivate my students to read?

Ms. Mahmoud

Potential Reflection Questions

1. Identify and provide examples of the types of behaviourism used in the case study (positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, negative punishment).

2. Going beyond the events described in this scenario, what are possible pros and cons of this teacher’s choice to establish a reward system to encourage reading?

3. What suggestions would have for this teacher and the librarian to encourage reading without relying on behaviourist strategies?

4. Assuming Bilal's allegations about Andy are true, how might you deal with this situation? What might be contributing to Andy's behaviour? How could this issue have been prevented?

Additional resources

- https://www.alfiekohn.org/article/reading-incentives/

- https://www.thisamericanlife.org/713/made-to-be-broken/act-two-11

When re-using this resource, please attribute as follows:

This UBC EPSE 308 Behaviourism Open Case Study was developed by Benjamin Dantzer, Lee Iskander, and Sharmilla Miller and it is licensed under a under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Post Image: Educators .co.uk, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

4 Fascinating Classical Conditioning & Behaviorism Studies

Did you experience a rumble in your stomach, even before you entered the dining hall and saw any food?

If so, your unconscious behavior was actually a real-life example of classical conditioning.

This article provides historical background and theory into classical conditioning and behaviorism. You will also learn how these theories are applied in today’s society and still hold considerable importance when learning about human behavior.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free . These science-based exercises will explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

Classical conditioning in psychology history, pavlov’s dog experiment explained, a look at the birth of behaviorism, watson’s little albert research, skinner’s conditioning studies, 4 contemporary findings and case studies, resources from positivepsychology.com, a take-home message.

To understand classical conditioning theory , you first need to understand learning. Learning is the process by which new knowledge, ideas, behaviors, and attitudes are acquired (Rehman, Mahabadi, Sanvictores, & Rehman, 2020). Learning can occur consciously or unconsciously (Rehman et al., 2020).

Classical conditioning is the process by which an automatic, conditioned response and stimuli are paired (McSweeney & Murphy, 2014). There are references in the classical conditioning literature to this being stimulus and response behavior (McSweeney & Murphy, 2014).

A famous work on classical conditioning is that by Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov, born in 1849. His influence on the study of classical conditioning has been tremendous. He won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for this piece of research (The Nobel Prize, n.d.). Classical conditioning was discovered accidentally and was referred to as ‘Pavlovian conditioning’ (Pavlov, 1927).

In this related article you will find practical classroom examples of Classical Conditioning .

Technical terms

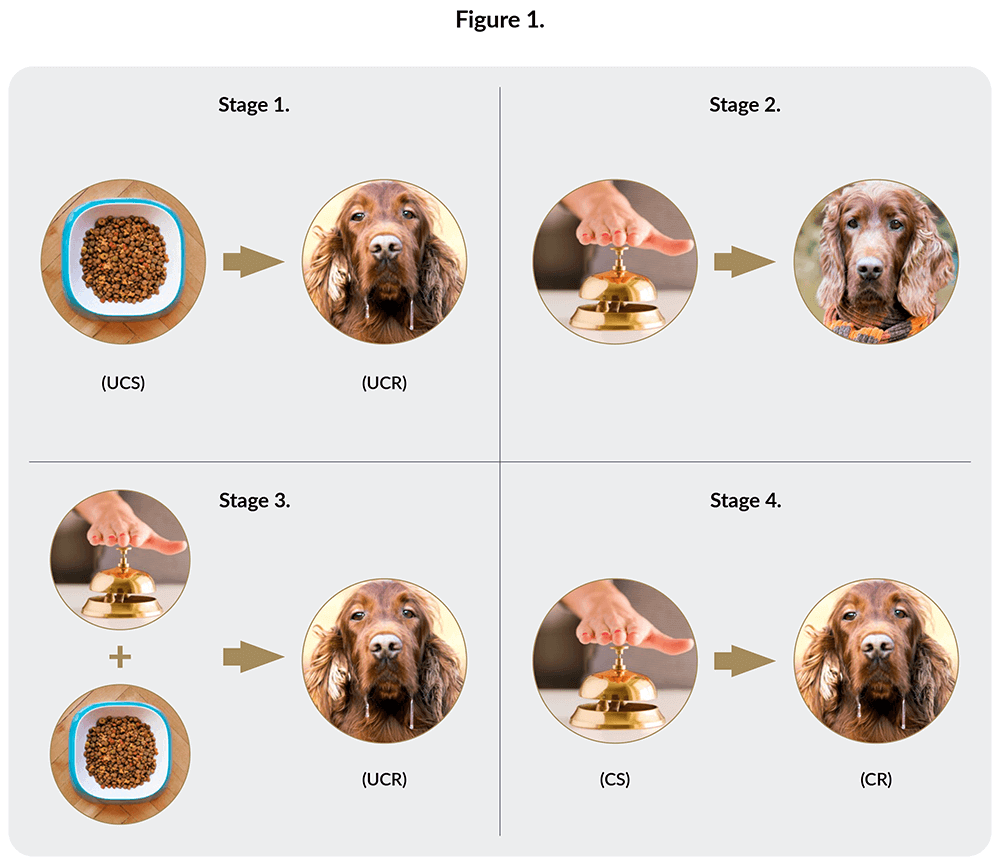

Pavlov (1927) developed the following technical terms to explain the process of classical conditioning and how it works.

- The unconditioned stimulus (UCS) occurs naturally and automatically, and unconditionally triggers a response.

- The unconditioned response (UCR) is the unlearned response. It occurs naturally as a response to the UCS.

- The conditioned stimulus (CS) is a previously neutral stimulus that after being associated with the UCS, results in the triggering of a conditioned response.

- The conditioned response (CR) is a response to the CS being associated with the UCS. The CR is a response that is made to the CS alone and without the UCS being required.

One interesting observation Pavlov made was that just before being given food, the dogs began to salivate. Sometimes this was just from the sight of the lab coats of the technicians feeding them. This made Pavlov wonder why the dogs salivated when there was no food in sight.

Pavlov decided to undertake a series of experiments with the dogs to investigate these observations. Pavlov rang a bell each time, just before feeding the dogs. At first there was no response. Then when the food came out, the dogs realized the sound of the bell meant food, and they salivated. After that, the sound of the bell on its own caused the dogs to salivate. They associated the bell with the arrival of food.

The following diagram (Figure 1) shows the different stages in the classical conditioning process in Pavlov’s (1897) dog experiments.

Classical conditioning has its roots in behaviorism. Behaviorism measures observable behaviors and events (Watson, 1913; Watson 1924).

John B. Watson, like Pavlov, investigated conditioned neutral stimuli eliciting reflexes in respondent conditioning (Watson & Rayner, 1920). Behaviorism views the environment as the primary influence upon human behavior, not genetic factors (Thorndike, 1905).

Behaviorism derived from the earlier research of Edward Thorndike (1905) and the Law of Effect in the later 19th century. This looked at consequences that strengthen and weaken behavior.

It attempted to replace depth psychology (Vladislav & Didier, 2018), considered having roots in the theories of Sigmund Freud, Carl Gustav, and Alfred Adler (Lewis, 1958). Depth psychology had difficulty testing predictions experimentally (Vladislav & Didier, 2018).

B. F. Skinner, an American psychologist, developed his own stance on the behaviorist approach, known as radical behaviorism (Schneider & Edward, 1987). He suggested that cognitions and emotions have the same variables of control as observed behavior (Mecca, 1974).

His technique was known as operant conditioning . This deals with reinforcement and punishment to increase or decrease the performance of behavior (Skinner, 1953).

Watson showed that humans can also be conditioned similarly to animals (Beck, Levinson, & Irons, 2009).

Watson used a small infant in his experiments referred to as Little Albert (Watson & Rayner, 1920). The child was exposed to different stimuli, including a rabbit, dog, wool, mask, monkey, and burning newspapers to see his reactions.

Little Albert showed no fear of the objects. It was not until the objects were paired with a loud noise (banging a metal bar with a hammer) that he began to cry after being shown a white rat. The child then expected to hear a frightening noise when he saw the white rat (neutral stimulus) on its own.

The white rat became the conditioned stimulus, and the emotional response of crying became the conditioned response. This is similar to the distress (unconditioned response) he initially displayed to the noise. Further studies showed Little Albert becoming distressed with furry objects and even a Santa Claus mask (Watson & Rayner, 1920).

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Exercises (PDF)

Enhance wellbeing with these free, science-based exercises that draw on the latest insights from positive psychology.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

B. F. Skinner (1948) conducted various experiments on rats in a box known as the ‘Skinner Box.’ At first, he put a hungry rat in the box that wandered around and discovered a lever. The rat eventually realized that after it pressed the lever, food was released into the box.

The rat then pressed the lever again each time it was hungry. It then pressed the lever immediately each time it was placed in the box, which showed that it was conditioned. Pressing the lever is the operant response, and the food is the reward (Skinner, 1948).

This type of experiment is also known as instrumental conditioning learning (Ainslie, 1992). The response is instrumental in receiving food. This experiment highlighted positive reinforcement (Skinner, 1948).

Skinner then undertook another experiment with rats. He put the rat in a similar box, and this time an electric current was used. As the rat became distressed and ran around the box, it accidentally knocked the lever. This automatically stopped the electric current.

The rat then learned to head first to the lever to prevent the discomfort of the electric current. Pressing the lever is the operant response, and stopping the electric current is its reward. This experiment highlighted negative reinforcement (Skinner, 1951).

Let’s take a look.

1. Classical conditioning and phobias

The classical and operant conditioning models developed by Pavlov, Watson, and Skinner are very relevant in contemporary society today. They can help explain the etiology and treatment of phobias in humans (Davey, 1992).

A phobia is a persistent and irrational fear to a specific situation, object, or activity (American Psychological Association, n.d.).

As an example, consider aerophobia, which is the fear of flying. People who have this phobia have an intense fear and anxiety around flying, sometimes at the mere thought of an airplane.

People with this phobia may avoid flying as much as possible to limit their distress. A closer look at the reason why people develop a fear of flying shows that a bad experience of taking off, terrible weather when flying, or turbulence may have been a crucial factor in the past (Clark & Rock, 2016).

We can think back to Pavlov’s dog experiments to understand more. It seems that the sight or thought of a plane has become the conditioned stimulus, and the fear of flying is the conditioned response.

Effective treatments for a phobia of flying often use the same principles of classical conditioning and learning (Rothbaum, Hodges, Lee, & Price, 2000). Therapists might activate the fear structure by exposing the person to the feared stimuli. This will elicit a fearful response (Rothbaum et al., 2000).

Once the exposure has been undertaken several times, in a process known as habituation (Bouton, 2007), the phobia is no longer reinforced (known as extinction) and eventually disappears (Miltenberger, 2012). In this way, a phobia can be reversed with the same principles of classical conditioning.

2. Classical conditioning and social anxiety

Social anxiety disorder is an anxiety disorder that has characteristics of extreme and persistent social anxiety that causes distress and prevents someone from participating in social activities (American Psychological Association, n.d.).

Social anxiety disorder may be triggered by some kind of stressful event early in a child’s life, such as being bullied, family abuse, or some type of public embarrassment (Erwin, Heimberg, Marx, & Franklin, 2006).

The dominant psychological treatment for anxiety disorders also involves repeated exposure, similar to the treatment of phobias described above.

Systematic desensitization is a gradual exposure to the phobic stimulus, perhaps including a gradual exposure to social situations.

Flooding is an alternative approach and not gradual. It is an immediate exposure to the most frightening aspect of the situation (American Psychological Association, n.d.), such as attending a large gathering.

Systematic desensitization and flooding can be undertaken in vitro (imagining exposure to the phobic stimulus) or in vivo (actually exposure to the phobic stimulus). Menzies and Clarke (1993) found that in vivo techniques are much more successful. In vitro can be used if it is more practical.

This is yet another example of how acquired fears can be removed by the principles of classical conditioning.

3. Operant conditioning and gambling

Gambling works based on operant conditioning, as gambling behavior is reinforced, increasing the likelihood that the behavior will be repeated. Gambling can become an addiction and is defined as such in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychological Association, n.d.).

Griffiths (2009) suggests that some types of gambling, such as slot machines, are addictive because financial rewards can be gained from pulling the lever. He also describes many other rewards, such as physiological rewards (adrenaline rush of winning), psychological rewards (excitement), and social rewards (praise from peers).

Aasved (2003) found that gamblers continued to gamble and repeat these experiences. Gambling is not prone to extinction, as it is reinforced partially (not every time), which makes the gambler repeat the behavior.

Gambling involves only partial reinforcement, as only a portion of responses are reinforced. The lack of predictability keeps people gambling. Does this remind you of Skinner’s study with rats and the rewards of food they gained from pressing the lever?

There are many treatments for gambling addiction. Treatment that combines the principles of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and in vivo strategies of imagining the consequences of gambling behaviors can be effective for problem gamblers (Bowden-George & Jones, 2015).

4. Operant conditioning and substance misuse

Some individuals use alcohol and drugs because of the pleasant positive feelings they gain from the experience. If they compulsively repeat the experience over time to achieve the same rewarding stimuli, the adverse consequence can be addiction (Angres & Bettinardi-Angres, 2008).

Aversion therapy (American Psychological Association, n.d.) is one way of eliminating addictions, through association with noxious and unpleasant experiences (Brewer, Streel, & Skinner, 2017; Platt, 2000). It is based on operant conditioning principles.

Aversion therapy involves pairing the unwanted and addictive behavior with an unpleasant experience. As an example, someone could be administered a medication that causes them to feel nauseous and vomit if they consume alcohol.

After aversion therapy, alcohol may be associated with the feeling of nausea, and so the person does not want to repeat this behavior (Brewer, Meyers, & Johnson, 2000).

Once again, this resembles the technique used by Skinner, when the rats were exposed to an electric shock and learned to press a level to avoid the experience.

What every person can learn from dog training – Noa Szefler

Throughout our blog, you’ll find many resources to help your clients address negative habits unconsciously acquired through repeated conditioning.

The tools below can help your clients become more aware of these habits and behaviors and help them gain control over their lives.

- Graded Exposure Worksheet This worksheet invites clients to rank their phobias from least to most feared as a first step toward conducting an exposure intervention.

- Building New Habits This worksheet succinctly explains how habits are formed and includes a space for clients to craft a plan to develop a new positive habit.

- Action Brainstorming This exercise helps clients identify, evaluate, and then break or change habits that may be getting in the way of making desired changes or moving closer to goals.

- Changing Physical Habits This worksheet helps clients reflect on their vulnerabilities and habits surrounding aspects of their physical health and consider steps to develop healthier habits.

- Reward Replacement Worksheet This worksheet helps clients identify the negative consequences of behaviors they use to reward themselves and select different reward behaviors with positive consequences to replace them.

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others enhance their wellbeing, this signature collection contains 17 validated positive psychology tools for practitioners. Use them to help others flourish and thrive.

17 Top-Rated Positive Psychology Exercises for Practitioners

Expand your arsenal and impact with these 17 Positive Psychology Exercises [PDF] , scientifically designed to promote human flourishing, meaning, and wellbeing.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

Classical and operant conditioning had great significance on the birth of behaviorism.

Classical conditioning has proven to be most valuable in understanding the acquisition of negative and unwanted behaviors such as phobias, anxiety, and addictions.

It is also valuable in providing people with treatment, as the same principles are used to undo inadvertently developed behaviors. These new treatments include exposure therapy, aversion therapy, systematic desensitization, and flooding.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article and will be able to help your own clients make the changes they need with the recommended resources.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free .

- Ainslie, G. (1992). Picoeconomics: The strategic interaction of successive motivational states within the person . Harvard University Press.

- American Psychological Association. (2021). Dictionary of psychology.

- Angres, D. H., & Bettinardi-Angres, K. (2008). The disease of addiction: Origins, treatment, and recovery. Disease-A-Month , 54 (10), 696–721.

- Aasved, M. (2003). The sociology of gambling (vol. 2). Charles C Thomas.

- Beck, H. P., Levinson, S., & Irons, G. (2009). Finding Little Albert. American Psychologist , 64 , 605–614.

- Bouton, M. E. (2007). Learning and behavior: A contemporary synthesis . MA Sinauer.

- Bowden-George, H., & Jones, S. (2015). A clinician’s guide to working with problem gamblers . Routledge.

- Brewer, C., Meyers, R., & Johnson, J. (2000). Does disulfiram help to prevent relapse in alcohol abuse? CNS Drugs , 14 , 329–341.

- Brewer, C., Streel, E., & Skinner, M. (2017). Supervised disulfiram’s superior effectiveness in alcoholism treatment: Ethical, methodological, and psychological aspects. Alcohol and Alcoholism , 52 (2), 213–219.

- Clark, G. I., & Rock, A. J. (2016). Processes contributing to the maintenance of flying phobia: A narrative review. Frontiers in Psychology , 7 , 754.

- Davey, G. C. (1992). Classical conditioning and the acquisition of human fears and phobias: A review and synthesis of the literature. Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy , 14 (1), 29–66.

- Erwin, B. A., Heimberg, R. G., Marx, B. P., & Franklin, M. E. (2006). Traumatic and socially stressful life events among persons with social anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders , 20 , 896–914.

- Griffiths, M. D. (2009). The psychology of gambling: A personal overview. Psychology Review , 16 (1), 25–27.

- Lewis, J. W. (1958). A survey of Adler’s writing. New Scientist , 4 (83), 224–225.

- McSweeney, F. K., & Murphy, E. S. (2014). The Wiley Blackwell handbook of operant and classical conditioning . Malden.

- Mecca, C. (1974). Radical behaviorism: The philosophy and the science . Authors Co-operative.

- Menzies, R. G., & Clarke, J. C. (1993). A comparison of in vivo and vicarious exposure in the treatment of childhood water phobia. Behavior Research and Therapy , 31 (1), 9–15.

- Miltenberger, R. (2012). Behavior modification, principles and procedures (5th ed.). Wadsworth.

- The Nobel Prize. (n.d.). Retrieved on June 11, 2021, from https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1904/pavlov/facts/

- Pavlov, I. P. (1897). The work of the digestive glands . Griffin.

- Pavlov, I. P. (1927). Conditioned reflexes: An investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex . Oxford University Press.

- Rehman, I., Mahabadi, N., Sanvictores, T., & Rehman, C. (2020). Classical conditioning . StatPearls. Retrieved June 2, 2021, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470326/

- Rothbaum, B. O., Hodges, L. S., Lee, J. H., & Price, L. (2000). A controlled study of virtual reality exposure therapy for the fear of flying. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 68 (6), 1020–1026.

- Skinner, B. F. (1948). ‘Superstition’ in the pigeon. Journal of Experimental Psychology , 38 , 168–172.

- Skinner, B. F. (1951). How to teach animals . Freeman.

- Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior . MacMillan

- Thorndike, E. L. (1905). The elements of psychology . A. G. Seiler.

- Watson, J. B. (1913). Psychology as the behaviorist views it. Psychological Review , 20 , 158–177.

- Watson, J. B. (1924). Behaviorism . People’s Institute.

- Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology , 3 (1), 1–14.

- Vladislav, S., & Didier, G.J. (2018). Dark religion: Fundamentalism from the perspective of Jungian psychology . Chiron.

Share this article:

Article feedback

Let us know your thoughts cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Hierarchy of Needs: A 2024 Take on Maslow’s Findings

One of the most influential theories in human psychology that addresses our quest for wellbeing is Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. While Maslow’s theory of [...]

Emotional Development in Childhood: 3 Theories Explained

We have all witnessed a sweet smile from a baby. That cute little gummy grin that makes us smile in return. Are babies born with [...]

Using Classical Conditioning for Treating Phobias & Disorders

Does the name Pavlov ring a bell? Classical conditioning, a psychological phenomenon first discovered by Ivan Pavlov in the late 19th century, has proven to [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (17)

- Positive Parenting (3)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (31)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

3 Positive Psychology Tools (PDF)

Behaviorism In Psychology

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Behaviorism, also known as behavioral learning theory, is a theoretical perspective in psychology that emphasizes the role of learning and observable behaviors in understanding human and animal actions. Behaviorism is a theory of learning that states all behaviors are learned through conditioned interaction with the environment. Thus, behavior is simply a response to environmental stimuli. The behaviorist theory is only concerned with observable stimulus-response behaviors, as they can be studied in a systematic and observable manner. Some of the key figures of the behaviorist approach include B.F. Skinner, known for his work on operant conditioning, and John B. Watson, who established the psychological school of behaviorism.

Principles of Behaviorism

The behaviorist movement began in 1913 when John B. Watson wrote an article entitled Psychology as the behaviorist views it , which set out several underlying assumptions regarding methodology and behavioral analysis:

All behavior is learned from the environment:

One assumption of the learning approach is that all behaviors are learned from the environment. They can be learned through classical conditioning, learning by association, or through operant conditioning, learning by consequences.

Behaviorism emphasizes the role of environmental factors in influencing behavior to the near exclusion of innate or inherited factors. This amounts essentially to a focus on learning. Therefore, when born, our mind is “tabula rasa” (a blank slate).

Classical conditioning refers to learning by association, and involves the conditioning of innate bodily reflexes with new stimuli.

Pavlov’s Experiment

Ivan Pavlov showed that dogs could be classically conditioned to salivate at the sound of a bell if that sound was repeatedly presented while they were given food.

He first presented the dogs with the sound of a bell; they did not salivate so this was a neutral stimulus. Then he presented them with food, they salivated.

The food was an unconditioned stimulus and salivation was an unconditioned (innate) response.

Pavlov then repeatedly presented the dogs with the sound of the bell first and then the food (pairing) after a few repetitions, the dogs salivated when they heard the sound of the bell.

The bell had become the conditioned stimulus and salivation had become the conditioned response.

Examples of classical conditioning applied to real life include:

- taste aversion – using derivations of classical conditioning, it is possible to explain how people develop aversions to particular foods

- learned emotions – such as love for parents, were explained as paired associations with the stimulation they provide

- advertising – we readily associate attractive images with the products they are selling

- phobias – classical conditioning is seen as the mechanism by which – we acquire many of these irrational fears.

Skinner argued that learning is an active process and occurs through operant conditioning . When humans and animals act on and in their environmental consequences, follow these behaviors.

If the consequences are pleasant, they repeat the behavior, but if the consequences are unpleasant, they do not.

Behavior is the result of stimulus-response:

Reductionism is the belief that human behavior can be explained by breaking it down into smaller component parts.

Reductionists say that the best way to understand why we behave as we do is to look closely at the very simplest parts that make up our systems, and use the simplest explanations to understand how they work.

Psychology should be seen as a science:

Theories need to be supported by empirical data obtained through careful and controlled observation and measurement of behavior. Watson (1913) stated:

“Psychology as a behaviorist views it is a purely objective experimental branch of natural science. Its theoretical goal is … prediction and control.” (p. 158).

The components of a theory should be as simple as possible. Behaviorists propose using operational definitions (defining variables in terms of observable, measurable events).

Behaviorism introduced scientific methods to psychology. Laboratory experiments were used with high control of extraneous variables.

These experiments were replicable, and the data obtained was objective (not influenced by an individual’s judgment or opinion) and measurable. This gave psychology more credibility.

Behaviorism is primarily concerned with observable behavior, as opposed to internal events like thinking and emotion:

The starting point for many behaviorists is a rejection of the introspection (the attempts to “get inside people’s heads”) of the majority of mainstream psychology.

While modern behaviorists often accept the existence of cognitions and emotions, they prefer not to study them as only observable (i.e., external) behavior can be objectively and scientifically measured.

Although theorists of this perspective accept that people have “minds”, they argue that it is never possible to objectively observe people’s thoughts, motives, and meanings – let alone their unconscious yearnings and desires.

Therefore, internal events, such as thinking, should be explained through behavioral terms (or eliminated altogether).

There is little difference between the learning that takes place in humans and that in other animals:

There’s no fundamental (qualitative) distinction between human and animal behavior. Therefore, research can be carried out on animals and humans.

The underlying assumption is that to some degree the laws of behavior are the same for all species and that therefore knowledge gained by studying rats, dogs, cats and other animals can be generalized to humans.

Consequently, rats and pigeons became the primary data source for behaviorists, as their environments could be easily controlled.

Types of Behaviorist Theory

Historically, the most significant distinction between versions of behaviorism is that between Watson’s original methodological behaviorism, and forms of behaviorism later inspired by his work, known collectively as neobehaviorism (e.g., radical behaviorism).

John B Watson: Methodological Behaviorism

As proposed by John B. Watson, methodological behaviorism is a school of thought in psychology that maintains that psychologists should study only observable, measurable behaviors and not internal mental processes.

According to Watson, since thoughts, feelings, and desires can’t be observed directly, they should not be part of psychological study.

Watson proposed that behaviors can be studied in a systematic and observable manner with no consideration of internal mental states.

He argued that all behaviors in animals or humans are learned, and the environment shapes behavior.

Watson’s article “Psychology as the behaviorist views it” is often referred to as the “behaviorist manifesto,” in which Watson (1913, p. 158) outlines the principles of all behaviorists:

“Psychology as the behaviorist views it is a purely objective experimental branch of natural science. Its theoretical goal is the prediction and control of behavior. Introspection forms no essential part of its methods, nor is the scientific value of its data dependent upon the readiness with which they lend themselves to interpretation in terms of consciousness.”

In his efforts to get a unitary scheme of animal response, the behaviorist recognizes no dividing line between man and brute.

Man’s behavior, with all of its refinement and complexity, forms only a part of the behaviorist’s total scheme of investigation.

This behavioral perspective laid the groundwork for further behavioral studies like B.F’s. Skinner who introduced the concept of operant conditioning.

Radical Behaviorism

Radical behaviorism was founded by B.F Skinner , who agreed with the assumption of methodological behaviorism that the goal of psychology should be to predict and control behavior.

Radical Behaviorism expands upon earlier forms of behaviorism by incorporating internal events such as thoughts, emotions, and feelings as part of the behavioral process.

Unlike methodological behaviorism, which asserts that only observable behaviors should be studied, radical behaviorism accepts that these internal events occur and influence behavior.

However, it maintains that they should be considered part of the environmental context and are subject to the same laws of learning and adaptation as overt behaviors.

Another important distinction between methodological and radical behaviorism concerns the extent to which environmental factors influence behavior. Watson’s (1913) methodological behaviorism asserts the mind is a tabula rasa (a blank slate) at birth.

In contrast, radical behaviorism accepts the view that organisms are born with innate behaviors and thus recognizes the role of genes and biological components in behavior.

Social Learning

Behaviorism has undergone many transformations since John Watson developed it in the early part of the twentieth century.

One more recent extension of this approach has been the development of social learning theory, which emphasizes the role of plans and expectations in people’s behavior.

Under social learning theory , people were no longer seen as passive victims of the environment, but rather they were seen as self-reflecting and thoughtful.

The theory is often called a bridge between behaviorist and cognitive learning theories because it encompasses attention, memory, and motivation.

Historical Timeline

- Pavlov (1897) published the results of an experiment on conditioning after originally studying digestion in dogs.

- Watson (1913) launches the behavioral school of psychology, publishing an article, Psychology as the behaviorist views it .

- Watson and Rayner (1920) conditioned an orphan called Albert B (aka Little Albert) to fear a white rat.

- Thorndike (1905) formalized the Law of Effect .

- Skinner (1938) wrote The Behavior of Organisms and introduced the concepts of operant conditioning and shaping.

- Clark Hull’s (1943) Principles of Behavior was published.

- B.F. Skinner (1948) published Walden Two , describing a utopian society founded upon behaviorist principles.

- Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior began in 1958.

- Chomsky (1959) published his criticism of Skinner’s behaviorism, “ Review of Verbal Behavior .”

- Bandura (1963) published a book called the Social Leaning Theory and Personality development which combines both cognitive and behavioral frameworks.

- B.F. Skinner (1971) published his book, Beyond Freedom and Dignity , where he argues that free will is an illusion.

Applications

Mental health.

Behaviorism theorized that abnormal behavior and mental illness stem from faulty learning processes rather than internal conflicts or unconscious forces, as psychoanalysis claimed.

Based on behaviorism, behavior therapy aims to replace maladaptive behaviors with more constructive ones through techniques like systematic desensitization, aversion therapy, and token economies. Systematic desensitization helps phobia patients gradually confront feared objects.

The behaviorist approach has been used in treating phobias. The individual with the phobia is taught relaxation techniques and then makes a hierarchy of fear from the least frightening to the most frightening features of the phobic object.

He then is presented with the stimuli in that order and learns to associate (classical conditioning) the stimuli with a relaxation response. This is counter-conditioning.

Aversion therapy associates unpleasant stimuli with unwanted habits to discourage them. Token economies reinforce desired actions by providing tokens redeemable for rewards.

The implications of classical conditioning in the classroom are less important than those of operant conditioning , but there is still a need for teachers to try to make sure that students associate positive emotional experiences with learning.

If a student associates negative emotional experiences with school, then this can obviously have bad results, such as creating a school phobia.

For example, if a student is bullied at school, they may learn to associate the school with fear. It could also explain why some students show a particular dislike of certain subjects that continue throughout their academic career. This could happen if a teacher humiliates or punishes a student in class.

Cue reactivity is the theory that people associate situations (e.g., meeting with friends)/ places (e.g., pub) with the rewarding effects of nicotine, and these cues can trigger a feeling of craving (Carter & Tiffany, 1999).

These factors become smoking-related cues. Prolonged use of nicotine creates an association between these factors and smoking based on classical conditioning.

Nicotine is the unconditioned stimulus (UCS), and the pleasure caused by the sudden increase in dopamine levels is the unconditioned response (UCR). Following this increase, the brain tries to lower the dopamine back to a normal level.

The stimuli that have become associated with nicotine were neutral stimuli (NS) before “learning” took place but they became conditioned stimuli (CS), with repeated pairings. They can produce the conditioned response (CR).

However, if the brain has not received nicotine, the levels of dopamine drop and the individual experiences withdrawal symptoms, therefore, is more likely to feel the need to smoke in the presence of the cues that have become associated with the use of nicotine.

Issues & Debates

Free will vs. determinism.

Strong determinism of the behavioral approach as all behavior is learned from our environment through classical and operant conditioning. We are the total sum of our previous conditioning.

Softer determinism of the social learning approach theory recognizes an element of choice as to whether we imitate a behavior or not.

Nature vs. Nurture

Behaviorism is very much on the nurture side of the debate as it argues that our behavior is learned from the environment.

The social learning theory is also on the nurture side because it argues that we learn behavior from role models in our environment.

The behaviorist approach proposes that apart from a few innate reflexes and the capacity for learning, all complex behavior is learned from the environment.

Holism vs. Reductionism

The behaviorist approach and social learning are reductionist ; they isolate parts of complex behaviors to study.

Behaviorists believe that all behavior, no matter how complex, can be broken down into the fundamental processes of conditioning.

Idiographic vs. Nomothetic

It is a nomothetic approach as it views all behavior governed by the same laws of conditioning.

However, it does account for individual differences and explains them in terms of differences in the history of conditioning.

Critical Evaluation

Behaviorism has experimental support: Pavlov showed that classical conditioning leads to learning by association. Watson and Rayner showed that phobias could be learned through classical conditioning in the “Little Albert” experiment.

An obvious advantage of behaviorism is its ability to define behavior clearly and measure behavior changes. According to the law of parsimony, the fewer assumptions a theory makes, the better and the more credible it is. Therefore, behaviorism looks for simple explanations of human behavior from a scientific standpoint.

Many of the experiments carried out were done on animals; we are different cognitively and physiologically. Humans have different social norms and moral values that mediate the effects of the environment.

Therefore people might behave differently from animals, so the laws and principles derived from these experiments, might apply more to animals than to humans.

Humanism rejects the nomothetic approach of behaviorism as they view humans as being unique and believe humans cannot be compared with animals (who aren’t susceptible to demand characteristics). This is known as an idiographic approach.

In addition, humanism (e.g., Carl Rogers) rejects the scientific method of using experiments to measure and control variables because it creates an artificial environment and has low ecological validity.

Humanistic psychology also assumes that humans have free will (personal agency) to make their own decisions in life and do not follow the deterministic laws of science .

The behaviorist approach emphasis on single influences on behavior is a simplification of circumstances where behavior is influenced by many factors. When this is acknowledged, it becomes almost impossible to judge the action of any single one.

This over-simplified view of the world has led to the development of ‘pop behaviorism, the view that rewards and punishments can change almost anything.

Therefore, behaviorism only provides a partial account of human behavior, that which can be objectively viewed. Essential factors like emotions, expectations, and higher-level motivation are not considered or explained. Accepting a behaviorist explanation could prevent further research from other perspectives that could uncover important factors.

For example, the psychodynamic approach (Freud) criticizes behaviorism as it does not consider the unconscious mind’s influence on behavior and instead focuses on externally observable behavior. Freud also rejects the idea that people are born a blank slate (tabula rasa) and states that people are born with instincts (e.g., eros and Thanatos).

Biological psychology states that all behavior has a physical/organic cause. They emphasize the role of nature over nurture. For example, chromosomes and hormones (testosterone) influence our behavior, too, in addition to the environment.

Behaviorism might be seen as underestimating the importance of inborn tendencies. It is clear from research on biological preparedness that the ease with which something is learned is partly due to its links with an organism’s potential survival.

Cognitive psychology states that mediational processes occur between stimulus and response, such as memory , thinking, problem-solving, etc.

Despite these criticisms, behaviorism has made significant contributions to psychology. These include insights into learning, language development, and moral and gender development, which have all been explained in terms of conditioning.

The contribution of behaviorism can be seen in some of its practical applications. Behavior therapy and behavior modification represent one of the major approaches to the treatment of abnormal behavior and are readily used in clinical psychology.

The behaviorist approach has been used in the treatment of phobias, and systematic desensitization .

Many textbooks depict behaviorism as dominating and defining psychology in the mid-20th century, before declining from the late 1950s with the “cognitive revolution.”

However, the empirical basis for claims about behaviorism’s prominence and decline has been limited. Wide-scope claims about behaviorism are often based on small, unrepresentative samples of historical data. This raises the question – to what extent was behaviorism actually dominant in American psychology?

To address this question, Braat et al. (2020) conducted a quantitative bibliometric analysis of 119,278 articles published in American psychology journals from 1920-1970.

They generated cocitation networks, mapping similarities between frequently cited authors, and co-occurrence networks of frequently used title terms, for each decade. This allowed them to examine the structure and development of psychology fields without relying on predefined behavioral/non-behavioral categories.

Key findings:

- In no decade did behaviorist authors belong to the most prominent citation clusters. Even a combined “behaviorist” cluster accounted for max. 28% of highly cited authors.

- The main focus was measuring personality/mental abilities – those clusters were consistently larger than behaviorist ones.

- Between 1920 and 1930, Watson was a prominent author, but behaviorism was a small (19%) slice of psychology. Larger clusters were mental testing and Gestalt psychology.

- From the 1930s, behaviorism split into two clusters, possibly reflecting “classical” vs. “neobehaviorist” approaches. However, the combined behaviorist cluster was still smaller than mental testing and Gestalt clusters.

- The influence of behaviorism did not dramatically decline after 1950. The behaviorist cluster was stable at 28% during the 1940s-60s, and its citation count quadrupled.

- Contrary to narratives, Skinner was not highly cited in the 1950s-60s – he did not dominate behaviorism after WWII.

- Analyses challenge assumptions that behaviorism was the single dominant force in mid-20th-century psychology. The story was more diverse.

However, behaviorist vocabulary became more prominent over time in title term analyses. This suggests behaviorists were influential in shaping psychological research agendas, if not fully dominating the field.

Overall, quantitative analyses provide a richer perspective on the development of behaviorism and 20th-century psychology. Claims that behaviorism “rose and fell” as psychology’s single dominant school appear too simplistic.

Psychology was more multifaceted, with behaviorism as one of several influential but not controlling approaches. The narrative requires reappraisal.

Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1963). Social learning and personality development . New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Braat, M., Engelen, J., van Gemert, T., & Verhaegh, S. (2020). The rise and fall of behaviorism: The narrative and the numbers. History of Psychology, 23 (3), 252-280.

Carter, B. L., & Tiffany, S. T. (1999). Meta‐analysis of cue‐reactivity in addiction research. Addiction , 94 (3), 327-340.

Chomsky, N. (1959). A review of BF Skinner’s Verbal Behavior . Language, 35(1) , 26-58.

Holland, J. G. (1978). BEHAVIORISM: PART OF THE PROBLEM OR PART OF THE SOLUTION? Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis , 11 (1), 163-174.

Hull, C. L. (1943). Principles of behavior: An introduction to behavior theory . New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Pavlov, I. P. (1897). The work of the digestive glands . London: Griffin.

Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis . New York: Appleton-Century.

Skinner, B. F. (1948). Walden two. New York: Macmillan.

Skinner, B. F. (1971). Beyond freedom and dignity . New York: Knopf.

Thorndike, E. L. (1905). The elements of psychology . New York: A. G. Seiler.

Watson, J. B. (1913). Psychology as the behaviorist views it . Psychological Review, 20 , 158-178.

Watson, J. B. (1930). Behaviorism (revised edition). University of Chicago Press.

Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions . Journal of Experimental Psychology, 3 , 1, pp. 1–14.

What is the theory of behaviorism?

What is behaviorism with an example.

An example of behaviorism is using systematic desensitization in the treatment of phobias. The individual with the phobia is taught relaxation techniques and then makes a hierarchy of fear from the least frightening to the most frightening features of the phobic object.

How behaviorism is used in the classroom?

In the conventional learning situation, behaviorist pedagogy applies largely to issues of class and student management, rather than to learning content.

It is very relevant to shaping skill performance. For example, unwanted behaviors, such as tardiness and dominating class discussions, can be extinguished by being ignored by the teacher (rather than being reinforced by having attention drawn to them).

Who founded behaviorism?

John B. Watson founded behaviorism. Watson proposed that psychology should abandon its focus on mental processes, which he believed were impossible to observe and measure objectively, and focus solely on observable behaviors.

His ideas, published in a famous article “ Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It ” in 1913, marked the formal start of behaviorism as a major school of psychological thought.

Is behavior analysis the same as behaviorism?

No, behavior analysis and behaviorism are not the same. Behaviorism is a broader philosophical approach to psychology emphasizing observable behaviors over internal events like thoughts and emotions.

Behavior analysis , specifically applied behavior analysis (ABA), is a scientific discipline and set of methods derived from behaviorist principles, used to understand and change specific behaviors, often employed in therapeutic contexts, such as with autism treatment.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Behaviorism?

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Classical Conditioning

Operant conditioning, frequently asked questions.

Behaviorism is a theory of learning based on the idea that all behaviors are acquired through conditioning, and conditioning occurs through interaction with the environment . Behaviorists believe that our actions are shaped by environmental stimuli.

In simple terms, according to this school of thought, also known as behavioral psychology, behavior can be studied in a systematic and observable manner regardless of internal mental states. Behavioral theory also says that only observable behavior should be studied, as cognition , emotions , and mood are far too subjective.

Strict behaviorists believe that any person—regardless of genetic background, personality traits , and internal thoughts— can be trained to perform any task, within the limits of their physical capabilities. It only requires the right conditioning.

Verywell / Jiaqi Zhou

History of Behaviorism

Behaviorism was formally established with the 1913 publication of John B. Watson 's classic paper, "Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It." It is best summed up by the following quote from Watson, who is often considered the father of behaviorism:

"Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-formed, and my own specified world to bring them up in and I'll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to become any type of specialist I might select—doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief and, yes, even beggar-man and thief, regardless of his talents, penchants, tendencies, abilities, vocations, and race of his ancestors."

Simply put, strict behaviorists believe that all behaviors are the result of experience. Any person, regardless of their background, can be trained to act in a particular manner given the right conditioning.

From about 1920 through the mid-1950s, behaviorism became the dominant school of thought in psychology . Some suggest that the popularity of behavioral psychology grew out of the desire to establish psychology as an objective and measurable science.

During that time, researchers were interested in creating theories that could be clearly described and empirically measured, but also used to make contributions that might have an influence on the fabric of everyday human lives.

Types of Behaviorism

There are two main types of behaviorism used to describe how behavior is formed.

Methodological Behaviorism

Methodological behaviorism states that observable behavior should be studied scientifically and that mental states and cognitive processes don't add to the understanding of behavior. Methodological behaviorism aligns with Watson's ideologies and approach.

Radical Behaviorism

Radical behaviorism is rooted in the theory that behavior can be understood by looking at one's past and present environment and the reinforcements within it, thereby influencing behavior either positively or negatively. This behavioral approach was created by the psychologist B.F. Skinner .

Classical conditioning is a technique frequently used in behavioral training in which a neutral stimulus is paired with a naturally occurring stimulus. Eventually, the neutral stimulus comes to evoke the same response as the naturally occurring stimulus, even without the naturally occurring stimulus presenting itself.

Throughout the course of three distinct phases of classical conditioning, the associated stimulus becomes known as the conditioned stimulus and the learned behavior is known as the conditioned response .

Learning Through Association

The classical conditioning process works by developing an association between an environmental stimulus and a naturally occurring stimulus.

In physiologist Ivan Pavlov 's classic experiments, dogs associated the presentation of food (something that naturally and automatically triggers a salivation response) at first with the sound of a bell, then with the sight of a lab assistant's white coat. Eventually, the lab coat alone elicited a salivation response from the dogs.

Factors That Impact Conditioning

During the first part of the classical conditioning process, known as acquisition , a response is established and strengthened. Factors such as the prominence of the stimuli and the timing of the presentation can play an important role in how quickly an association is formed.

When an association disappears, this is known as extinction . It causes the behavior to weaken gradually or vanish. Factors such as the strength of the original response can play a role in how quickly extinction occurs. The longer a response has been conditioned, for example, the longer it may take for it to become extinct.

Operant conditioning, sometimes referred to as instrumental conditioning, is a method of learning that occurs through reinforcement and punishment . Through operant conditioning, an association is made between a behavior and a consequence for that behavior.

This behavioral approach says that when a desirable result follows an action, the behavior becomes more likely to happen again in the future. Conversely, responses followed by adverse outcomes become less likely to reoccur.

Consequences Affect Learning

Behaviorist B.F. Skinner described operant conditioning as the process in which learning can occur through reinforcement and punishment. More specifically: By forming an association between a certain behavior and the consequences of that behavior, you learn.

For example, if a parent rewards their child with praise every time they pick up their toys, the desired behavior is consistently reinforced and the child will become more likely to clean up messes.

Timing Plays a Role

The process of operant conditioning seems fairly straightforward—simply observe a behavior, then offer a reward or punishment. However, Skinner discovered that the timing of these rewards and punishments has an important influence on how quickly a new behavior is acquired and the strength of the corresponding response.

This makes reinforcement schedules important in operant conditioning. These can involve either continuous or partial reinforcement.

- Continuous reinforcement involves rewarding every single instance of a behavior. It is often used at the beginning of the operant conditioning process. Then, as the behavior is learned, the schedule might switch to one of partial reinforcement.

- Partial reinforcement involves offering a reward after a number of responses or after a period of time has elapsed. Sometimes, partial reinforcement occurs on a consistent or fixed schedule. In other instances, a variable and unpredictable number of responses or amount of time must occur before the reinforcement is delivered.

Uses for Behaviorism

The behaviorist perspective has a few different uses, including some related to education and mental health.

Behaviorism can be used to help students learn, such as by influencing lesson design. For instance, some teachers use consistent encouragement to help students learn (operant conditioning) while others focus more on creating a stimulating environment to increase engagement (classical conditioning).

One of the greatest strengths of behavioral psychology is the ability to clearly observe and measure behaviors. Because behaviorism is based on observable behaviors, it is often easier to quantify and collect data when conducting research.

Mental Health

Behavioral therapy was born from behaviorism and originally used in the treatment of autism and schizophrenia. This type of therapy involves helping people change problematic thoughts and behaviors, thereby improving mental health.

Effective therapeutic techniques such as intensive behavioral intervention, behavior analysis, token economies, and discrete trial training are all rooted in behaviorism. These approaches are often very useful in changing maladaptive or harmful behaviors in both children and adults.

Impact of Behaviorism

Several thinkers influenced behavioral psychology. Among these are Edward Thorndike , a pioneering psychologist who described the law of effect, and Clark Hull , who proposed the drive theory of learning.

There are a number of therapeutic techniques rooted in behavioral psychology. Though behavioral psychology assumed more of a background position after 1950, its principles still remain important.

Even today, behavior analysis is often used as a therapeutic technique to help children with autism and developmental delays acquire new skills. It frequently involves processes such as shaping (rewarding closer approximations to the desired behavior) and chaining (breaking a task down into smaller parts, then teaching and chaining the subsequent steps together).

Other behavioral therapy techniques include aversion therapy , systematic desensitization , token economies, behavior modeling , and contingency management.

Criticisms of Behaviorism

Many critics argue that behaviorism is a one-dimensional approach to understanding human behavior. They suggest that behavioral theories do not account for free will or internal influences such as moods, thoughts, and feelings.

Freud, for example, felt that behaviorism failed by not accounting for the unconscious mind's thoughts, feelings, and desires, which influence people's actions. Other thinkers, such as Carl Rogers and other humanistic psychologists , believed that behaviorism was too rigid and limited, failing to take into consideration personal agency.

More recently, biological psychology has emphasized the role the brain and genetics play in determining and influencing human actions. The cognitive approach to psychology focuses on mental processes such as thinking, decision-making, language, and problem-solving. In both cases, behaviorism neglects these processes and influences in favor of studying only observable behaviors.

Behavioral psychology also does not account for other types of learning that occur without the use of reinforcement and punishment. Moreover, people and animals can adapt their behavior when new information is introduced, even if that behavior was established through reinforcement.

A Word From Verywell

While the behavioral approach might not be the dominant force that it once was, it has still had a major impact on our understanding of human psychology . The conditioning process alone has been used to understand many different types of behaviors, ranging from how people learn to how language develops.

But perhaps the greatest contributions of behavioral psychology lie in its practical applications. Its techniques can play a powerful role in modifying problematic behavior and encouraging more positive, helpful responses. Outside of psychology, parents, teachers, animal trainers, and many others make use of basic behavioral principles to help teach new behaviors and discourage unwanted ones.

John B. Watson is known as the founder of behaviorism. Though others had similar ideas in the early 1900s, when behavioral theory began, some suggest that Watson is credited as behavioral psychology's founder due to being "an attractive, strong, scientifically accomplished, and forceful speaker and an engaging writer" who was willing to share this behavioral approach when other psychologists were less likely to speak up.

Behaviorism can be used to help elicit positive behaviors or responses in students, such as by using reinforcement. Teachers with a behavioral approach often use "skill and drill" exercises to reinforce correct responses through consistent repetition, for instance.

Other ways reinforcement-based behaviorism can be used in education include praising students for getting the right answer and providing prizes for those who do well. Using tests to measure performance enables teachers to measure observable behaviors and is, therefore, another behavioral approach.

Behaviorism says that behavior is a result of environment, the environment being an external stimulus. Psychoanalysis is the opposite of this, in that it is rooted in the belief that behavior is a result of an internal stimulus. Psychoanalytic theory is based on behaviors being motivated by one's unconscious mind, thus resulting in actions that are consistent with their unknown wishes and desires.

Whereas strict behaviorism has no room for cognitive influences, cognitive behaviorism operates on the assumption that behavior is impacted by thoughts and emotions. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), for instance, attempts to change negative behaviors by changing the destructive thought patterns behind them.

Krapfl JE. Behaviorism and society . Behav Anal. 2016;39(1):123-9. doi:10.1007/s40614-016-0063-8