If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 8

- Introduction to the Civil Rights Movement

- African American veterans and the Civil Rights Movement

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

- Emmett Till

- The Montgomery Bus Boycott

- "Massive Resistance" and the Little Rock Nine

- The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

- The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965

- SNCC and CORE

- Black Power

- The Civil Rights Movement

- In Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954) a unanimous Supreme Court declared that racial segregation in public schools is unconstitutional.

- The Court declared “separate” educational facilities “inherently unequal.”

- The case electrified the nation, and remains a landmark in legal history and a milestone in civil rights history.

A segregated society

The brown v. board of education case, thurgood marshall, the naacp, and the supreme court, separate is "inherently unequal", brown ii: desegregating with "all deliberate speed”, what do you think.

- James T. Patterson, Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 387.

- James T. Patterson, Brown v. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Milestone and Its Troubled Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 25-27.

- Patterson, Brown v. Board of Education, 387.

- Patterson, Brown v. Board of Education, 32.

- See Patterson, Brown v. Board of Education, and Richard Kluger, Simple Justice: The History of Brown v. Board of Education and Black America’s Struggle for Equality (New York: Knopf, 2004).

- Patterson, Brown v. Board of Education, 43-45.

- Supreme Court of the United States, Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

- Patterson, Grand Expectations, 394-395.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Brown v. Board of Education (1954)

Primary tabs.

Brown v. Board of Education (1954) was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision that struck down the “Separate but Equal” doctrine and outlawed the ongoing segregation in schools. The court ruled that laws mandating and enforcing racial segregation in public schools were unconstitutional, even if the segregated schools were “separate but equal” in standards. The Supreme Court’s decision was unanimous and felt that " separate educational facilities are inherently unequal ," and hence a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution . Nonetheless, since the ruling did not list or specify a particular method or way of how to proceed in ending racial segregation in schools, the Court's ruling i n Brown II (1955) demanded states to desegregate “ with all deliberate speed .”

Background :

The events relevant to this specific case first occurred in 1951, when a public school district in Topeka, Kansas refused to let Oliver Brown’s daughter enroll at the nearest school to their home and instead required her to enroll at a school further away. Oliver Brown and his daughter were black. The Brown family, along with twelve other local black families in similar circumstances, filed a class action lawsuit against the Topeka Board of Education in a federal court arguing that the segregation policy of forcing black students to attend separate schools was unconstitutional. However, the U.S. District Court for the District of Kansas ruled against the Browns, justifying their decision on judicial precedent of the Supreme Court's 1896 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson , which ruled that racial segregation did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment 's Equal Protection Clause as long as the facilities and situations were equal, hence the doctrine known as " separate but equal ." After this decision from the District Court in Kansas, the Browns, who were represented by the then NAACP chief counsel Thurgood Marshall, appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's ruling in Brown overruled Plessy v. Ferguson by holding that the "separate but equal" doctrine was unconstitutional for American educational facilities and public schools. This decision led to more integration in other areas and was seen as major victory for the Civil Rights Movement. Many future litigation cases used the similar argumentation methods used by Marshall in this case. While this was seen as a landmark decision, many in the American Deep South were uncomfortable with this decision. Various Southern politicians tried to actively resist or delay attempts to desegregated their schools. These collective efforts were known as the “ Massive Resistance ,” which was started by Virginia Senator Harry F. Byrd. Thus, in just four years after the Supreme Court’s ruling, the Supreme Court affirmed its ruling again in the case of Cooper v. Aaron , holding that government officials had no power to ignore the ruling or to frustrate and delay desegregation.

[Last updated in July of 2022 by the Wex Definitions Team ]

- ACADEMIC TOPICS

- legal history

- civil rights

- education law

- THE LEGAL PROCESS

- legal practice/ethics

- group rights

- legal education and practice

- wex articles

- wex definitions

Educator Resources

Brown v. Board of Education

The Supreme Court's opinion in the Brown v. Board of Education case of 1954 legally ended decades of racial segregation in America's public schools. Chief Justice Earl Warren delivered the unanimous ruling in the landmark civil rights case. State-sanctioned segregation of public schools was a violation of the 14th Amendment and was therefore unconstitutional. This historic decision marked the end of the "separate but equal" precedent set by the Supreme Court nearly 60 years earlier and served as a catalyst for the expanding civil rights movement. Read more...

Primary Sources

Links go to DocsTeach , the online tool for teaching with documents from the National Archives.

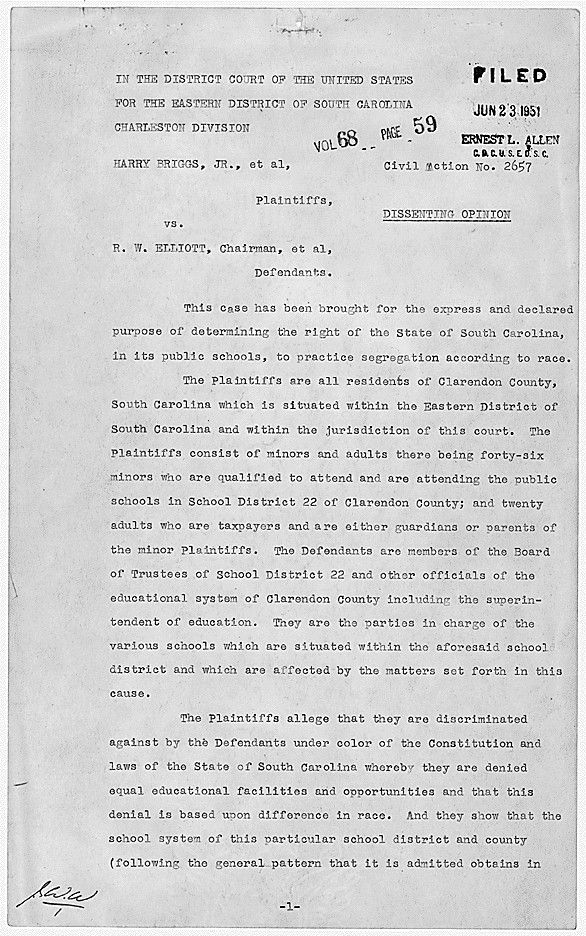

Dissenting opinion in Briggs v. Elliott in which Judge Waties Waring opposed the District Court ruling that "separate but equal" schools were not in violation of the 14th amendment – he presented arguments that would later be used by the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas , 6/21/1951

View in National Archives Catalog

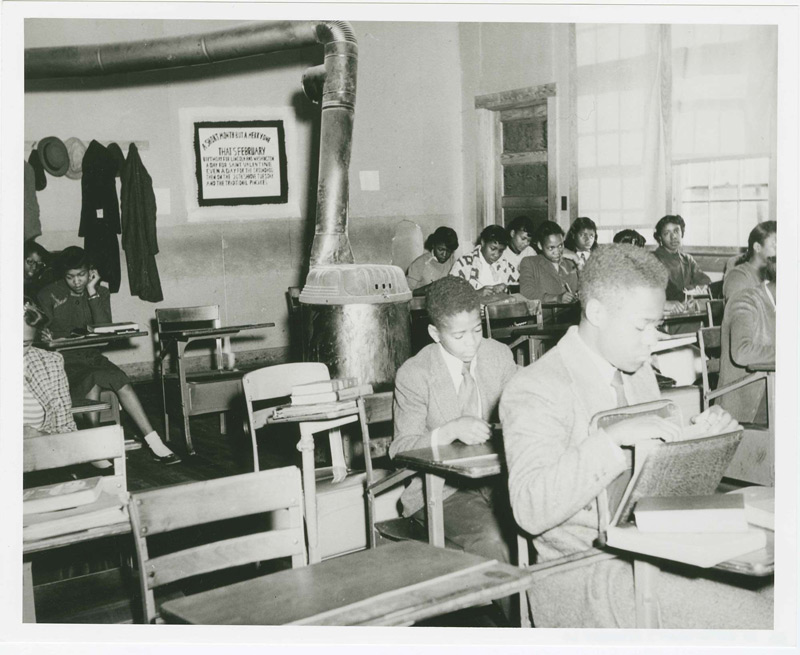

English class at Moton High School , a school for Black students, one of several photographs entered as evidence in the case Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia , which was one of five cases that the Supreme Court consolidated under Brown v. Board of Education , ca. 1951

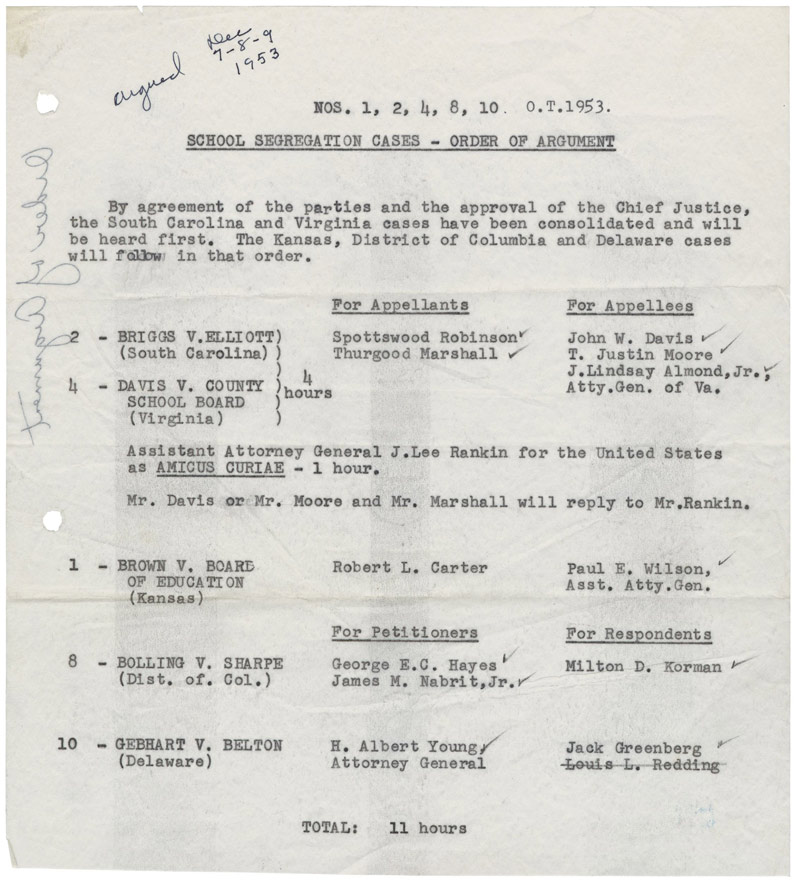

Order of Argument in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka during which attorneys reargued the five cases that the Supreme Court heard collectively and consolidated under the name Brown v. Board of Education , 12/1953

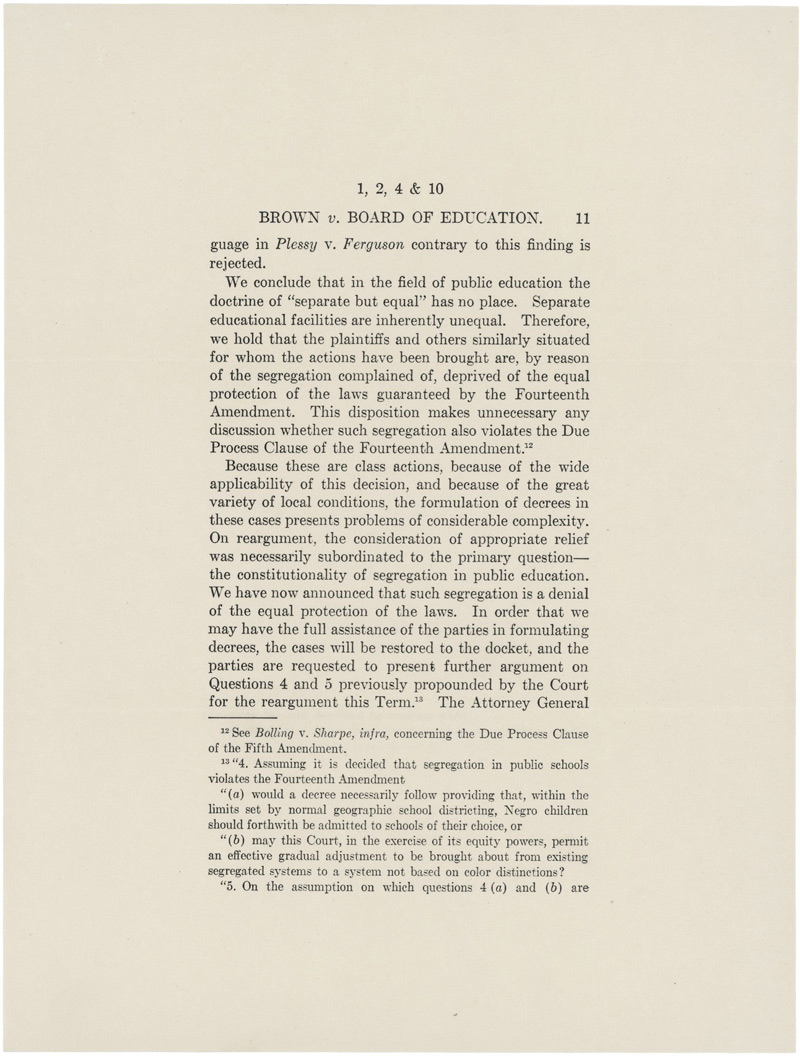

Page 11 of the unanimous Supreme Court ruling of 5/17/1954 in Brown v. Board of Education that state-sanctioned segregation of public schools violated the 14th Amendment, marking the end of the "separate but equal" precedent

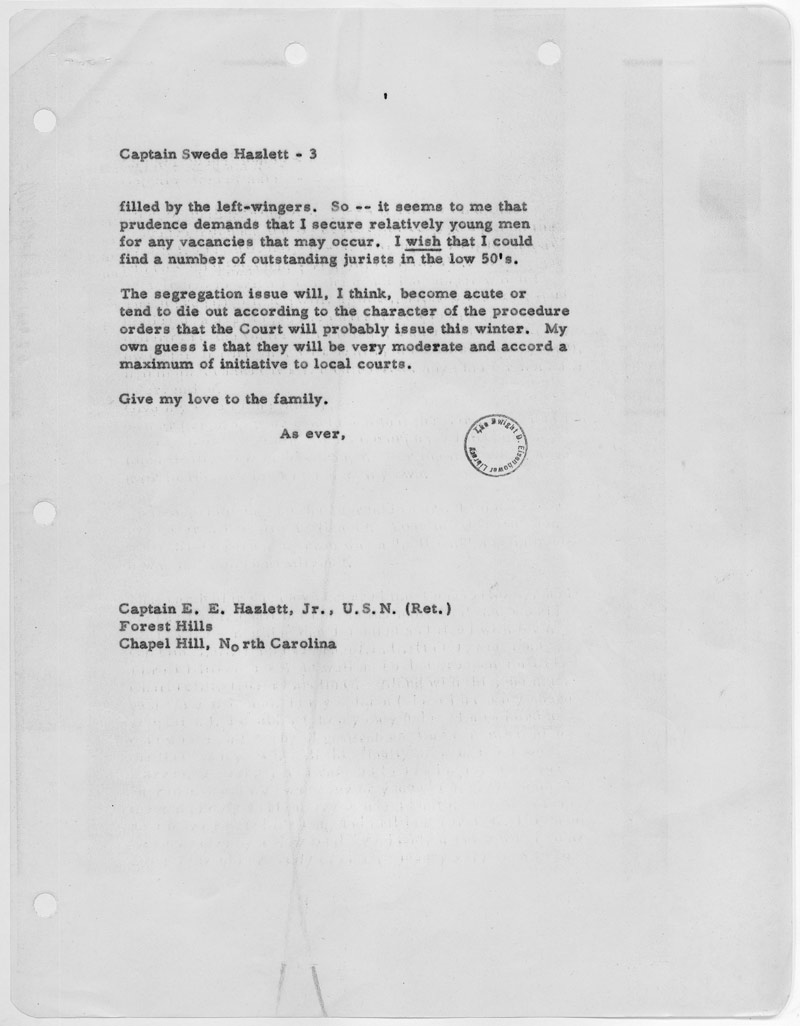

Page 3 of a letter from President Eisenhower to E. E. "Swede" Hazlett in which the President expressed his belief that the new Warren court would be very moderate on the issue of segregation, 10/23/1954

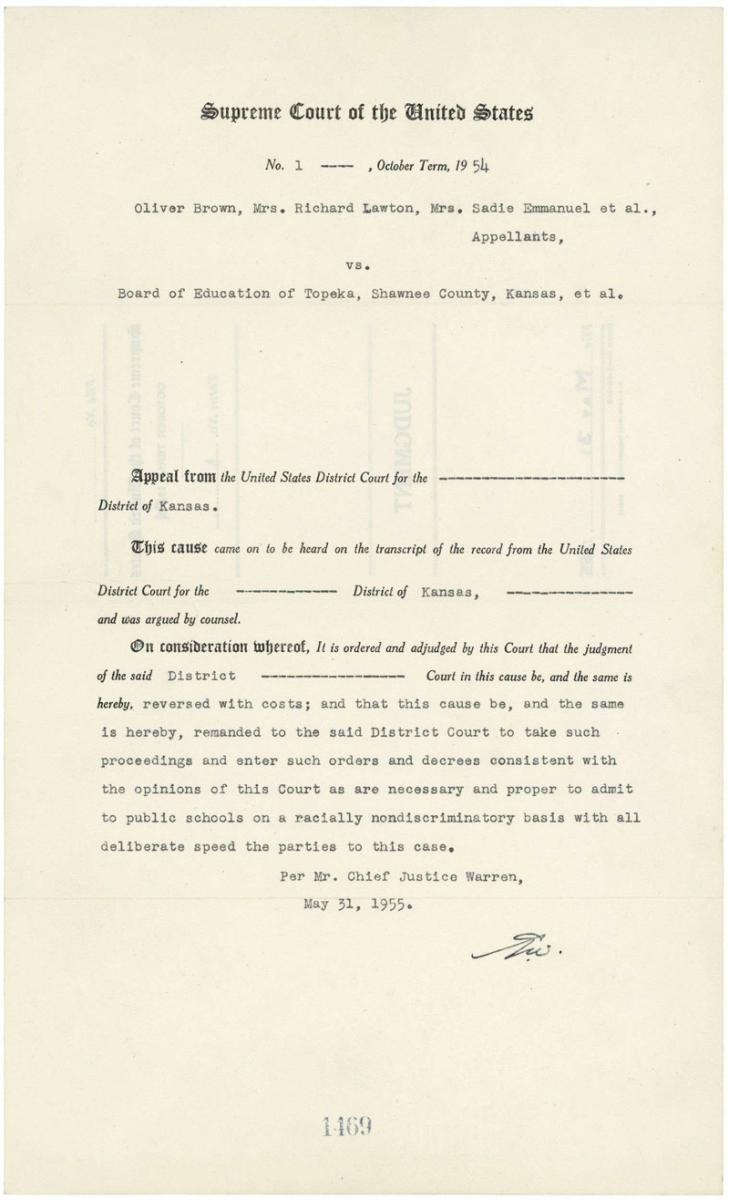

Judgment of May 31, 1955, in Brown v. Board of Education (Brown II) – a year after the ruling that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional – directing that schools be desegregated "with all deliberate speed"

- Brown v. Board of Education Timeline

- Biographies of Key Figures

- Related Primary Sources: Photographs from the Dorothy Davis Case

Teaching Activities

The "Rights in America" page on DocsTeach includes primary sources and document-based teaching activities related to how individuals and groups have asserted their rights as Americans. It includes topics such as segregation, racism, citizenship, women's independence, immigration, and more.

Additional Background Information

While the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution outlawed slavery, it wasn't until three years later, in 1868, that the 14th Amendment guaranteed the rights of citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States, including due process and equal protection of the laws. These two amendments, as well as the 15th Amendment protecting voting rights, were intended to eliminate the last remnants of slavery and to protect the citizenship of Black Americans.

In 1875, Congress also passed the first Civil Rights Act, which held the "equality of all men before the law" and called for fines and penalties for anyone found denying patronage of public places, such as theaters and inns, on the basis of race. However, a reactionary Supreme Court reasoned that this act was beyond the scope of the 13th and 14th Amendments, as these amendments only concerned the actions of the government, not those of private citizens. With this ruling, the Supreme Court narrowed the field of legislation that could be supported by the Constitution and at the same time turned the tide against the civil rights movement.

By the late 1800s, segregation laws became almost universal in the South where previous legislation and amendments were, for all practical purposes, ignored. The races were separated in schools, in restaurants, in restrooms, on public transportation, and even in voting and holding office.

Plessy v. Ferguson

In 1896, the Supreme Court upheld the lower courts' decision in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson . Homer Plessy, a Black man from Louisiana, challenged the constitutionality of segregated railroad coaches, first in the state courts and then in the U. S. Supreme Court.

The high court upheld the lower courts, noting that since the separate cars provided equal services, the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment was not violated. Thus, the "separate but equal" doctrine became the constitutional basis for segregation. One dissenter on the Court, Justice John Marshall Harlan, declared the Constitution "color blind" and accurately predicted that this decision would become as baneful as the infamous Dred Scott decision of 1857.

In 1909 the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was officially formed to champion the modern Civil Rights Movement. In its early years its primary goals were to eliminate lynching and to obtain fair trials for Black Americans. By the 1930s, however, the activities of the NAACP began focusing on the complete integration of American society. One of their strategies was to force admission of Black Americans into universities at the graduate level where establishing separate but equal facilities would be difficult and expensive for the states.

At the forefront of this movement was Thurgood Marshall, a young Black lawyer who, in 1938, became general counsel for the NAACP's Legal Defense and Education Fund. Significant victories at this level included Gaines v. University of Missouri in 1938, Sipuel v. Board of Regents of University of Oklahoma in 1948, and Sweatt v. Painter in 1950. In each of these cases, the goal of the NAACP defense team was to attack the "equal" standard so that the "separate" standard would in turn become susceptible.

Five Cases Consolidated under Brown v. Board of Education

By the 1950s, the NAACP was beginning to support challenges to segregation at the elementary school level. Five separate cases were filed in Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, the District of Columbia, and Delaware:

- Oliver Brown et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka, Shawnee County, Kansas, et al.

- Harry Briggs, Jr., et al. v. R.W. Elliott, et al.

- Dorothy E. Davis et al. v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, et al.

- Spottswood Thomas Bolling et al. v. C. Melvin Sharpe et al.

- Francis B. Gebhart et al. v. Ethel Louise Belton et al.

While each case had its unique elements, all were brought on the behalf of elementary school children, and all involved Black schools that were inferior to white schools. Most importantly, rather than just challenging the inferiority of the separate schools, each case claimed that the "separate but equal" ruling violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment.

The lower courts ruled against the plaintiffs in each case, noting the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling of the United States Supreme Court as precedent. In the case of Brown v. Board of Education , the Federal district court even cited the injurious effects of segregation on Black children, but held that "separate but equal" was still not a violation of the Constitution. It was clear to those involved that the only effective route to terminating segregation in public schools was going to be through the United States Supreme Court.

In 1952 the Supreme Court agreed to hear all five cases collectively. This grouping was significant because it represented school segregation as a national issue, not just a southern one. Thurgood Marshall, one of the lead attorneys for the plaintiffs (he argued the Briggs case), and his fellow lawyers provided testimony from more than 30 social scientists affirming the deleterious effects of segregation on Black and white children. These arguments were similar to those alluded to in the Dissenting Opinion of Judge Waites Waring in Harry Briggs, Jr., et al. v. R. W. Elliott, Chairman, et al . (shown above).

These [social scientists] testified as to their study and researches and their actual tests with children of varying ages and they showed that the humiliation and disgrace of being set aside and segregated as unfit to associate with others of different color had an evil and ineradicable effect upon the mental processes of our young which would remain with them and deform their view on life until and throughout their maturity....They showed beyond a doubt that the evils of segregation and color prejudice come from early training...it is difficult and nearly impossible to change and eradicate these early prejudices however strong may be the appeal to reason…if segregation is wrong then the place to stop it is in the first grade and not in graduate colleges.

The lawyers for the school boards based their defense primarily on precedent, such as the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling, as well as on the importance of states' rights in matters relating to education.

Realizing the significance of their decision and being divided among themselves, the Supreme Court took until June 1953 to decide they would rehear arguments for all five cases.

The arguments were scheduled for the following term. The Court wanted briefs from both sides that would answer five questions, all having to do with the attorneys' opinions on whether or not Congress had segregation in public schools in mind when the 14th amendment was ratified.

The Order of Argument (shown above) offers a window into the three days in December of 1953 during which the attorneys reargued the cases. The document lists the names of each case, the states from which they came, the order in which the Court heard them, the names of the attorneys for the appellants and appellees, the total time allotted for arguments, and the dates over which the arguments took place.

Briggs v. Elliott

The first case listed, Briggs v. Elliott , originated in Clarendon County, South Carolina, in the fall of 1950. Harry Briggs was one of 20 plaintiffs who were charging that R.W. Elliott, as president of the Clarendon County School Board, violated their right to equal protection under the fourteenth amendment by upholding the county's segregated education law. Briggs featured social science testimony on behalf of the plaintiffs from some of the nation's leading child psychologists, such as Dr. Kenneth Clark, whose famous doll study concluded that segregation negatively affected the self-esteem and psyche of African-American children. Such testimony was groundbreaking because on only one other occasion in U.S. history had a plaintiff attempted to present such evidence before the Court.

Thurgood Marshall, the noted NAACP attorney and future Supreme Court Justice, argued the Briggs case at the District and Federal Court levels. The U.S. District Court's three-judge panel ruled against the plaintiffs, with one judge dissenting, stating that "separate but equal" schools were not in violation of the 14th amendment. In his dissenting opinion (shown above), Judge Waties Waring presented some of the arguments that would later be used by the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas . The case was appealed to the Supreme Court.

Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia

Marshall also argued the Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, case at the Federal level. Originally filed in May of 1951 by plaintiff's attorneys Spottswood Robinson and Oliver Hill, the Davis case, like the others, argued that Virginia's segregated schools were unconstitutional because they violated the equal protection clause of the fourteenth amendment. And like the Briggs case, Virginia's three-judge panel ruled against the 117 students who were identified as plaintiffs in the case. (For more on this case, see Photographs from the Dorothy Davis Case .)

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

Listed third in the order of arguments, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was initially filed in February of 1951 by three Topeka area lawyers, assisted by the NAACP's Robert Carter and Jack Greenberg. As in the Briggs case, this case featured social science testimony on behalf of the plaintiffs that segregation had a harmful effect on the psychology of African-American children. While that testimony did not prevent the Topeka judges from ruling against the plaintiffs, the evidence from this case eventually found its way into the wording of the Supreme Court's May 17, 1954 opinion. The Court concluded that:

To separate them [children in grade and high schools] from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely to ever be undone.

Bolling v. Sharpe

Because Washington, D.C., is a Federal territory governed by Congress and not a state, the Bolling v. Sharpe case was argued as a fifth amendment violation of "due process." The fourteenth amendment only mentions states, so this case could not be argued as a violation of "equal protection," as were the other cases. When a District of Columbia parent, Gardner Bishop, unsuccessfully attempted to get 11 African-American students admitted into a newly constructed white junior high school, he and the Consolidated Parents Group filed suit against C. Melvin Sharpe, president of the Board of Education of the District of Columbia. Charles Hamilton Houston, the NAACP's special counsel, former dean of the Howard University School of Law, and mentor to Thurgood Marshall, took up the Bolling case.

With Houston's health already failing in 1950 when he filed suit, James Nabrit, Jr. replaced Houston as the original attorney. By the time the case reached the Supreme Court on appeal, George E.C. Hayes had been added as an attorney for the petitioners, beside James Nabrit, Jr. According to the Court, due to the decision in Plessy , "the plaintiffs and others similarly situated" had been "deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment," therefore, segregation of America's public schools was unconstitutional.

Belton v. Gebhart

The last case listed in the order of arguments, Belton v. Gebhart , was actually two nearly identical cases (the other being Bulah v. Gebhart ), both originating in the state of Delaware in 1952. Ethel Belton was one of the parents listed as plaintiffs in the case brought in Claymont, while Sarah Bulah brought suit in the town of Hockessin, Delaware. While both of these plaintiffs brought suit because their African-American children had to attend inferior schools, Sarah Bulah's situation was unique in that she was a white woman with an adopted Black child, who was still subject to the segregation laws of the state. Local attorney Louis Redding, Delaware's only African-American attorney at the time, originally argued both cases in Delaware's Court of Chancery. NAACP attorney Jack Greenberg assisted Redding. Belton/Bulah v. Gebhart was argued at the Federal level by Delaware's attorney general, H. Albert Young.

Supreme Court Rehears Arguments

Reargument of the Brown v. Board of Education cases at the Federal level took place December 7-9, 1953. Throngs of spectators lined up outside the Supreme Court by sunrise on the morning of December 7, although arguments did not actually commence until one o'clock that afternoon. Spottswood Robinson began the argument for the appellants, and Thurgood Marshall followed him. Virginia's Assistant Attorney General, T. Justin Moore, followed Marshall, and then the court recessed for the evening.

On the morning of December 8, Moore resumed his argument, followed by his colleague, J. Lindsay Almond, Virginia's Attorney General. Following this argument, Assistant United States Attorney General J. Lee Rankin, presented the U.S. government's amicus curiae brief on behalf of the appellants, which showed its support for desegregation in public education. In the afternoon, Robert Carter began arguments in the Kansas case, and Paul Wilson, Attorney General for the state of Kansas, followed him in rebuttal.

On December 9, after James Nabrit and Milton Korman debated Bolling , and Louis Redding, Jack Greenberg, and Delaware's Attorney General, H. Albert Young argued Gebhart , the Court recessed. The attorneys, the plaintiffs, the defendants, and the nation waited five months and eight days to receive the unanimous opinion of Chief Justice Earl Warren's court, which declared, "in the field of public education, the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place."

The Warren Court

In September 1953, President Eisenhower had appointed Earl Warren, governor of California, as the new Supreme Court chief justice. Eisenhower believed Warren would follow a moderate course of action toward desegregation. His feelings regarding the appointment are detailed in the closing paragraphs of a letter he wrote to E. E. "Swede" Hazlett, a childhood friend (shown above). On the issue of segregation, Eisenhower believed that the new Warren court would "be very moderate and accord a maximum initiative to local courts."

In his brief to the Warren Court that December, Thurgood Marshall described the separate but equal ruling as erroneous and called for an immediate reversal under the 14th Amendment. He argued that it allowed the government to prohibit any state action based on race, including segregation in public schools. The defense countered this interpretation pointing to several states that were practicing segregation at the time they ratified the 14th Amendment. Surely they would not have done so if they had believed the 14th Amendment applied to segregation laws. The U.S. Department of Justice also filed a brief; it was in favor of desegregation but asked for a gradual changeover.

Over the next few months, the new chief justice worked to bring the splintered Court together. He knew that clear guidelines and gradual implementation were going to be important considerations, as the largest concern remaining among the justices was the racial unrest that would doubtless follow their ruling.

The Supreme Court Ruling

Finally, on May 17, 1954, Chief Justice Earl Warren read the unanimous opinion: school segregation by law was unconstitutional (shown above). Arguments were to be heard during the next term to determine exactly how the ruling would be imposed.

Just over one year later, on May 31, 1955, Warren read the Court's unanimous decision, now referred to as Brown II (also shown above). It instructed states to begin desegregation plans "with all deliberate speed." Warren employed careful wording in order to ensure backing of the full Court in his official judgment.

The Brown decision was a watershed in American legal and civil rights history because it overturned the "separate but equal" doctrine first articulated in the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896. By overturning Plessy , the Court ended America's 58-year-long practice of legal racial segregation and paved the way for the integration of America's public school systems.

Despite two unanimous decisions and careful, if not vague, wording, there was considerable resistance to the Supreme Court's ruling in Brown v. Board of Education . In addition to the obvious disapproving segregationists were some constitutional scholars who felt that the decision went against legal tradition by relying heavily on data supplied by social scientists rather than precedent or established law. Supporters of judicial restraint believed the Court had overstepped its constitutional powers by essentially writing new law.

However, minority groups and members of the Civil Rights Movement were buoyed by the Brown decision even without specific directions for implementation. Proponents of judicial activism believed the Supreme Court had appropriately used its position to adapt the basis of the Constitution to address new problems in new times. The Warren Court stayed this course for the next 15 years, deciding cases that significantly affected not only race relations, but also the administration of criminal justice, the operation of the political process, and the separation of church and state.

Parts of this text were adapted from an article written by Mary Frances Greene, a teacher at Marie Murphy School in Wilmette, IL.

Legal Dictionary

The Law Dictionary for Everyone

Brown v. Board of Education

Following is the case brief for Brown v. Board of Education, United States Supreme Court, (1954)

Case Summary of Brown v. Board of Education:

- Oliver Brown was denied admission into a white school

- As a representative of a class action suit, Brown filed a claim alleging that laws permitting segregation in public schools were a violation of the 14 th Amendment equal protection clause .

- After the District Court upheld segregation using Plessy v. Ferguson as authority, Brown petitioned the United States Supreme Court.

- The Supreme Court held that segregation had a profound and detrimental effect on education and segregation deprived minority children of equal protection under the law.

Brown v. Board of Education Case Brief

Statement of Facts:

Oliver Brown and other plaintiffs were denied admission into a public school attended by white children. This was permitted under laws which allowed segregation based on race. Brown claimed that the segregation deprived minority children of equal protection under the 14 th Amendment. Brown filed a class action, consolidating cases from Virginia, South Carolina, Delaware and Kansas against the Board of Education in a federal district court in Kansas.

Procedural History:

Brown filed suit against the Board of Education in District Court. After the District Court held in favor of the Board, Brown appealed to the United States Supreme Court. The Supreme Court granted certiorari.

Issues and Holding:

Does the segregation on the basis of race in public schools deprive minority children of equal educational opportunities, violating the 14 th Amendment? Yes.

The Court Reversed the District Court’s decision.

Rule of Law or Legal Principle Applied:

Separating educational facilities based on racial classifications is unequal in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14 th Amendment.

The Court held that looking to historical legislation and prior cases could not yield a true meaning of the 14 th Amendment because each is inconclusive.

At the time the 14 th Amendment was enacted, almost no African American children were receiving an education. As such, trying to determine the historical intentions surrounding the 14 th Amendment is not helpful. In addition, few public schools existed at the time the amendment was adopted.

Analyzing the text of the amendment itself is necessary to determine its true meaning. The Court held the basic language of the Amendment suggests the intent to prohibit all discriminatory legislation against minorities.

Despite the fact each facility is essentially the same, the Court held it was necessary to examine the actual effect of segregation on education. Over the past few years, public education has turned into one of the most valuable public services both state and local governments have to offer. Since education has a heavy bearing on the future success of each child, the opportunity to be educated must be equal to each student.

The Court stated that the opportunity for education available to segregated minorities has a profound and detrimental effect on both their hearts and minds. Studies showed that segregated students felt less motivated, inferior and have a lower standard of performance than non-minority students. The Court explicitly overturned Plessy v. Ferguson , 163 U.S. 537 (1896), stating that segregation deprives African-American students of equal protection under the 14 th Amendment.

Concurring/ Dissenting opinion :

Unanimous decision led by Justice Warren.

Significance:

Brown v. Board of Education was the landmark case which desegregated public schools in the United States. It abolished the idea of “ separate but equal .”

Student Resources:

http://www.pbs.org/wnet/supremecourt/rights/landmark_brown.html https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/347/483

Skip to main navigation

- Email Updates

- Federal Court Finder

History - Brown v. Board of Education Re-enactment

The plessy decision.

In 1892, an African American man named Homer Plessy refused to give up his seat to a white man on a train in New Orleans, as he was required to do by Louisiana state law. Plessy was arrested and decided to contest the arrest in court. He contended that the Louisiana law separating Black people from white people on trains violated the "equal protection clause" of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. By 1896, his case had made it all the way to the United States Supreme Court. By a vote of 8-1, the Supreme Court ruled against Plessy . In the case of Plessy v. Ferguson , Justice Henry Billings Brown, writing the majority opinion, stated that:

"The object of the [Fourteenth] amendment was undoubtedly to enforce the equality of the two races before the law, but in the nature of things it could not have been intended to abolish distinctions based upon color, or to endorse social, as distinguished from political, equality. . . If one race be inferior to the other socially, the Constitution of the United States cannot put them upon the same plane."

The lone dissenter, Justice John Marshal Harlan, interpreting the Fourteenth Amendment another way, stated, "Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens." Justice Harlan's dissent would become a rallying cry for those in later generations working to declare segregation unconstitutional.

The Road to Brown

(Note: Some of the case information is from Patterson, James T. Brown v. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Milestone and Its Troubled Legacy. Oxford University Press; New York, 2001.)

Early Cases

Despite the Supreme Court's ruling in Plessy and similar cases, people continued to press for the abolition of Jim Crow and other racially discriminatory laws. One particular organization that fought for racial equality was the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) founded in 1909. From 1935 to 1938, the legal arm of the NAACP was headed by Charles Hamilton Houston. Houston, together with Thurgood Marshall, devised a strategy to attack Jim Crow laws in the field of education. Although Marshall played a crucial role in all of the cases listed below, Houston was the head of the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund while Murray v. Maryland and Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada were decided. After Houston returned to private practice in 1938, Marshall became head of the Fund and used it to argue the cases of Sweat v. Painter and McLaurin v. Oklahoma Board of Regents of Higher Education .

Pearson v. Murray (Md. 1936)

Unwilling to accept the fact that the University of Maryland School of Law was rejecting Black applicants solely because of their race, beginning in 1933 Thurgood Marshall, who was rejected from this law school because of its racial acceptance policies, decided to challenge this practice in the Maryland court system. Before a Baltimore City Court in 1935, Marshall argued that Donald Gaines Murray was just as qualified as white applicants to attend the University of Maryland's School of Law and that it was solely due to his race that he was rejected. He argued that since law schools for Black students were not of the same academic caliber, at the time, as the University's law school, the University was violating the principle of "separate but equal." Marshall also argued that the disparities between the law schools for white students and Black students were so great that the only remedy would be to allow students like Murray to attend the University's law school. The Baltimore City Court agreed, and the University appealed to the Maryland Court of Appeals. In 1936, the Court of Appeals ruled in favor of Murray and ordered the law school to admit him. Two years later, Murray graduated with his law degree.

Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada (1938)

Beginning in 1936, the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund decided to take on the case of Lloyd Gaines, a graduate student of the HCBU Lincoln University in Missouri. Gaines had applied to the University of Missouri Law School but was denied admission because of his race. The State of Missouri gave Gaines the option of either attending a Black law school that it would build (Missouri did not have any all-Black law schools at this time) or Missouri would help to pay for him to attend a law school in a neighboring state. Gaines rejected both of these options and, with the help of Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, he sued the state to attend the University of Missouri's law school. By 1938, his case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, and, in December of that year, the Court sided with him. The six-member majority stated that since law school for Black students did not exist in the State of Missouri, the "equal protection clause" required the state to provide within its boundaries a legal education for Gaines. In other words, since the state provided legal education for white students, it could not send Black students, like Gaines, to school in another state.

Sweat v. Painter (1950)

Encouraged by their victory in Gaines' case, the NAACP continued to attack legally sanctioned racial discrimination in higher education. In 1946, an African American man named Heman Sweat applied to the law school at the University of Texas whose student body was white. The University set up an underfunded law school for Black students. However, Sweat employed the services of Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund and sued to be admitted to the University's law school attended by white students. When the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 1950, the Court unanimously agreed with him, citing as its reason the blatant inequalities between the University's law school (the school for white students) and the hastily erected school for Black students. In other words, the two schools were "separate," but not "equal." Like the Murray case, the Court found the only appropriate remedy for this situation was to admit Sweat to the University's law school.

McLaurin v. Oklahoma Board of Regents of Higher Education (1950)

In 1949, the University of Oklahoma admitted George McLaurin, an African American male, to its doctoral program. However, it required him to sit apart and eat apart from the rest of his class. McLaurin sued to end the practices, stating that they had an adverse impact on his academic pursuits. McLaurin was represented by Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund. It eventually went to the U.S. Supreme Court. In an opinion delivered on the same day as the decision in Sweat , the Court stated that the University's actions concerning McLaurin were adversely affecting his ability to learn and ordered that the practices cease immediately.

Brown v. Board of Education (1954, 1955)

The case that came to be known as Brown v. Board of Education was actually the name given to five separate cases that were heard by the U.S. Supreme Court concerning the separate but equal concept in public schools. These cases were Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka , Briggs v. Elliot, Davis v. Board of Education of Prince Edward County (VA.) , Bolling v. Sharpe , and Gebhart v. Ethel . While the facts of each case were different, the main issue was the constitutionality of state-sponsored segregation in public schools. Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund handled the cases.

The families lost in the lower courts, then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

When the cases came before the Supreme Court in 1952, the Court consolidated all five cases under the name of Brown v. The Board of Education. Marshall argued the case before the Court. Although he raised a variety of legal issues on appeal, the central argument was that separate school systems for Black students and white students were inherently unequal, and a violation of the "Equal Protection Clause" of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. He also presented the results of sociological tests, such as the one performed by social scientists Kenneth and _______ Clark, arguing that segregated school systems had a tendency to make Black children feel inferior to white children. In light of those findings, Marshall argued that such a system should not be legally permissible.

Meeting to decide the case, the Justices of the Supreme Court realized that they were deeply divided over the issues raised. Unable to come to a decision by June 1953 (the end of the Court's 1952-1953 term), the Court decided to rehear the case in December 1953. During the intervening months, Chief Justice Fred Vinson died and was replaced by Gov. Earl Warren, of California. After the case was reheard in 1953, Chief Justice Warren was able to bring all of the Justices together to support a unanimous decision declaring unconstitutional the concept of separate but equal in public schools. On May 14, 1954, he delivered the opinion of the Court, stating that "We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. . ."

DISCLAIMER: These resources are created by the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts for educational purposes only. They may not reflect the current state of the law, and are not intended to provide legal advice, guidance on litigation, or commentary on any pending case or legislation.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Brown v. Board of Education: The First Step in the Desegregation of America’s Schools

By: Sarah Pruitt

Updated: September 7, 2023 | Original: May 16, 2018

On May 17, 1954, Chief Justice Earl Warren issued the Supreme Court ’s unanimous decision in Brown v. Board of Education , ruling that racial segregation in public schools violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment . The upshot: Students of color in America would no longer be forced by law to attend traditionally under-resourced Black-only schools.

The decision marked a legal turning point for the American civil-rights movement . But it would take much more than a decree from the nation’s highest court to change hearts, minds and two centuries of entrenched racism. Brown was initially met with inertia and, in most southern states, active resistance. More than half a century later, progress has been made, but the vision of Warren’s court has not been fully realized.

The Supreme Court Rules 'Separate' Means Unequal

The landmark case began as five separate class-action lawsuits brought by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) on behalf of Black schoolchildren and their families in Kansas , South Carolina , Delaware , Virginia and Washington, D.C . The lead plaintiff, Oliver Brown, had filed suit against the Board of Education in Topeka, Kansas in 1951, after his daughter Linda was denied admission to a white elementary school.

Her all-Black school, Monroe Elementary, was fortunate—and unique—to be endowed with well-kept facilities, well-trained teachers and adequate materials. But the other four lawsuits embedded in the Brown case pointed to more common fundamental challenges. The case in Clarendon, South Carolina described school buildings as no more than dilapidated wooden shacks. In Prince Edward County, Virginia, the high school had no cafeteria, gym, nurse’s office or teachers’ restrooms, and overcrowding led to students being housed in an old school bus and tar-paper shacks.

Brown v. Board First to Rule Against Segregation Since Reconstruction Era

The Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board marked a shining moment in the NAACP’s decades-long campaign to combat school segregation. In declaring school segregation as unconstitutional, the Court overturned the longstanding “separate but equal” doctrine established nearly 60 years earlier in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). In his opinion, Chief Justice Warren asserted public education was an essential right that deserved equal protection, stating unequivocally that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

Still, Thurgood Marshall , head of the NAACP’s Legal Defense and Educational Fund and lead lawyer from the plaintiffs, knew the fight was far from over—and that the high court’s decision was only a first step in the long, complicated process of dismantling institutionalized racism. He warned his colleagues soon after the verdict came down: “The fight has just begun.”

In 1954, the Supreme Court unanimously strikes down segregation in public schools, sparking the Civil Rights movement.

Brown v. Board Does Not Instantly Desegregate Schools

In its landmark ruling, the Supreme Court didn’t specify exactly how to end school segregation, but rather asked to hear further arguments on the issue. The Court’s timidity, combined with steadfast local resistance, meant that the bold Brown v. Board of Education ruling did little on the community level to achieve the goal of desegregation. Black students, to a large degree, still attended schools with substandard facilities, out-of-date textbooks and often no basic school supplies.

In a 1955 case known as Brown v. Board II , the Court gave much of the responsibility for the implementation of desegregation to local school authorities and lower courts, urging that the process proceed “with all deliberate speed.” But many lower court judges in the South, who had been appointed by segregationist politicians, were emboldened to resist desegregation by the Court’s lackluster enforcement of the Brown decision.

In Prince Edward County, where one of the five class-action suits behind Brown was filed, the Board of Supervisors refused to appropriate funds for the County School Board, choosing to shut down the public schools for five years rather than integrate them.

This backlash against the Court’s verdict reached the highest levels of government: In 1956, 82 representatives and 19 senators endorsed a so-called “Southern Manifesto” in Congress, urging Southerners to use all “lawful means” at their disposal to resist the “chaos and confusion” that school desegregation would cause.

In 1964, a full decade after the decision, more than 98 percent of Black children in the South still attended segregated schools .

The Brown Ruling Becomes a Catalyst for the Civil Rights Movement

For the first time since the Reconstruction Era , the Court’s ruling focused national attention on the subjugation of Black Americans. The result? The growth of the nascent civil-rights movement, which would doggedly challenge segregation and demand legal equality for Black families through boycotts, sit-ins, freedom rides and voter-registration drives.

The Brown verdict inspired Southern Blacks to defy restrictive and punitive Jim Crow laws, however, the ruling also galvanized Southern whites in defense of segregation—including the infamous standoff at a high school in Little Rock , Arkansas in 1957. Violence against civil-rights activists escalated, outraging many in the North and abroad, helping to speed up the passage of major civil-rights and voting-rights legislation by the mid-1960s.

Finally, in 1964, two provisions within the Civil Rights Act effectively gave the federal government the power to enforce school desegregation for the first time: The Justice Department could sue schools that refused to integrate, and the government could withhold funding from segregated schools. Within five years after the act took effect, nearly a third of Black children in the South attended integrated schools, and that figure reached as high as 90 percent by 1973.

Legacy and Impact of Brown v. Board

More than 60 years after the landmark ruling, assessing its impact remains a complicated endeavor. The Court’s verdict fell short of initial hopes that it would end school segregation in America for good, and some argued that larger social and political forces within the nation played a far greater role in ending segregation.

As the Supreme Court has grown increasingly polarized along political lines, both conservative and liberal justices have claimed the legacy of Brown v. Board to argue different sides in the constitutional debate. In 2007, the Court ruled 5-4 against allowing public schools to take race into account in their admission policies in order to achieve or maintain integration.

Chief Justice John Roberts, writing for the majority, asserted: “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” And in a dissenting opinion, Justice John Paul Stevens wrote that the ruling “rewrites the history of one of this court’s most important decisions.”

Are Schools 'Separate But Equal’ in the 21st Century?

School segregation remains in force all over America today, largely because many of the neighborhoods in which schools are still located are themselves segregated. Despite the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968 and later judicial decisions making racial discrimination illegal, exclusionary economic-zoning laws still bar low-income and working-class Americans from many neighborhoods, which in many cases reduces their access to higher quality schools.

According to a 2014 report by Richard Rothstein of the Economic Policy Institute report , as of the 60th anniversary of the Brown v. Board verdict the typical Black student attended a school where only 29 percent of his or her fellow students were white, down from some 36 percent in 1980.

HISTORY Vault: Black History

Watch acclaimed Black History documentaries on HISTORY Vault.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- 20th Century: Post-1945

- 20th Century: Pre-1945

- African American History

- Antebellum History

- Asian American History

- Civil War and Reconstruction

- Colonial History

- Cultural History

- Early National History

- Economic History

- Environmental History

- Foreign Relations and Foreign Policy

- History of Science and Technology

- Labor and Working Class History

- Late 19th-Century History

- Latino History

- Legal History

- Native American History

- Political History

- Pre-Contact History

- Religious History

- Revolutionary History

- Slavery and Abolition

- Southern History

- Urban History

- Western History

- Women's History

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Brown v. board of education.

- Christopher W. Schmidt Christopher W. Schmidt Chicago-Kent College of Law and the American Bar Foundation

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.668

- Published online: 26 April 2021

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court unanimously struck down as unconstitutional state-mandated racial segregation in public schools, which at the time was policy in seventeen states. Brown v. Board of Education marked the culmination of a decades-long litigation campaign by the NAACP. White-controlled states across the South responded by launching a “massive resistance” campaign of defiance against Brown , which was followed by decades of struggles, inside and outside the courts, to desegregate the nation’s schools. Brown also signaled the new and often controversial direction the Supreme Court would take under leadership of Chief Justice Earl Warren—one that read the rights protections of the Constitution more broadly than its predecessors and was more aggressive in using these rights to protect vulnerable minorities.

Brown is nearly universally celebrated today, yet the terms of its celebration remain contested. Some see the case as a call for ambitious litigation strategies and judicial boldness, whereas others use it to demonstrate the limited power of the courts to effect social change. Some find in Brown a commitment to a principle of a “colorblind” Constitution, others a commitment to expunging practices that oppress racial minorities (often requiring race-conscious policies). Brown thus remains what it was in 1954: a bold statement of the principle of racial equality whose meaning the nation is still struggling to work out.

- Supreme Court

- segregation

- civil rights

- racial discrimination

- civil rights movement

- Thurgood Marshall

- Fourteenth Amendment

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, American History. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 23 April 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|195.216.135.184]

- 195.216.135.184

Character limit 500 /500

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

1954: brown v. board of education.

On May 17, 1954, in a landmark decision in the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, the U.S. Supreme Court declared state laws establishing separate public schools for students of different races to be unconstitutional. The decision dismantled the legal framework for racial segregation in public schools and Jim Crow laws, which limited the rights of African Americans, particularly in the South.

Segregation in Schools

Naacp challenges segregation in court, separate, but equal has 'no place', brown v board quick facts.

What is it? A landmark Supreme Court case.

Significance: Ended 'Separate, but equal,' desegregated public schools.

Date: May 17, 1954

Associated Sites: Brown v Board of Education National Historic Site; US Supreme Court Building

You Might Also Like

- brown v. board of education national historical park

- little rock central high school national historic site

- civil rights

- civil rights movement

- desegregation

- african american history

- brown v. the board of education of topeka

- public education

Brown v. Board of Education National Historical Park , Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site

Last updated: July 12, 2023

- Find a Lawyer

- Ask a Lawyer

- Research the Law

- Law Schools

- Laws & Regs

- Newsletters

- Justia Connect

- Pro Membership

- Basic Membership

- Justia Lawyer Directory

- Platinum Placements

- Gold Placements

- Justia Elevate

- Justia Amplify

- PPC Management

- Google Business Profile

- Social Media

- Justia Onward Blog

Brown v. Board of Education, 344 U.S. 141 (1952)

U.S. Supreme Court

Brown v. Board of Education

November 24, 1952

344 U.S. 141

This is an appeal from a decision of the District Court sustaining the constitutionality of a state statute which authorized racial segregation in the public schools of Kansas. In the District Court, the State intervened and defended the constitutionality of the statute, but neither the State nor any of the other appellees has entered an appearance or filed a brief here. Because of the importance of the issue, this Court requests that the State present its views at the oral argument. If the State does not desire to appear, the Attorney General of the State is requested to advise this Court whether the State's default shall be construed as a concession of the invalidity of the statute. Pp. 344 U. S. 141 -142.

The decision below is reported in 98 F. Supp. 797 .

- Opinions & Dissents

- Copy Citation

Get free summaries of new US Supreme Court opinions delivered to your inbox!

- Bankruptcy Lawyers

- Business Lawyers

- Criminal Lawyers

- Employment Lawyers

- Estate Planning Lawyers

- Family Lawyers

- Personal Injury Lawyers

- Estate Planning

- Personal Injury

- Business Formation

- Business Operations

- Intellectual Property

- International Trade

- Real Estate

- Financial Aid

- Course Outlines

- Law Journals

- US Constitution

- Regulations

- Supreme Court

- Circuit Courts

- District Courts

- Dockets & Filings

- State Constitutions

- State Codes

- State Case Law

- Legal Blogs

- Business Forms

- Product Recalls

- Justia Connect Membership

- Justia Premium Placements

- Justia Elevate (SEO, Websites)

- Justia Amplify (PPC, GBP)

- Testimonials

Some case metadata and case summaries were written with the help of AI, which can produce inaccuracies. You should read the full case before relying on it for legal research purposes.

- Marbury v. Madison (1803)

- Scott v. Sandford (1857)

- The Slaughterhouse Cases (1873)

- Lochner v. New York (1905)

- Schenck v. United States (1919)

- Korematsu v. United States (1944)

- Youngstown Sheet and Tube Co. v. Sawyer (1952)

- Brown v. Board of Education(1954)

- Mapp v. Ohio (1961)

- Baker v. Carr (1962)

- Miranda v. Arizona (1966)

- Roe v. Wade (1973)

- McCulloch v. Maryland (1819)

- Civil Rights Cases (1883)

- Yick Wo v. Hopkins (1886)

- Plessy v. Ferguson (1896)

- Gideon v. Wainwright (1963)

- Griswold v. Connecticut (1965)

- Katz v. United States (1967)

- Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969)

- Tinker v. Des Moines (1969)

- New York Times v. United States (1971)

- Gregg v. Georgia (1976)

- Regents of Univ. Cal v. Bakke (1978)

- Brown v. Board of Education full program

- President George W. Bush remarks at Brown v. Board Education Site dedication

- Justice Scalia's originalist perspective on Plessy and Brown

- President Obama on Education and Civil Rights

- Justice Alito on Plessy and Brown

- Attorney General Eric Holder on the 60th Anniversary of Brown v. Board

- School Integration: Nine from Little Rock

- Briggs v. Elliot

- Panel on the Legacy of Brown v. Board

- Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP

- Earl Warren's Judicial Philosophy

- Chief Justice Warren's Judicial Diplomacy

- Ending Separate but Equal in the Courts

- Marshall & School Desegregation Plaintiffs

- Plessy v. Ferguson

- Black vs. White School Facilities

- Monroe Elementary School in Topeka

Brown v. Board of Education (1954) struck down the doctrine of “separate but equal” established by the earlier Supreme Court case, Plessy v. Ferguson . In Brown , the Court ruled racial segregation in public schools inherently unequal and unconstitutional based on the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Even though Linda Brown lived just blocks away from an all-white elementary school, she had to walk across railroad tracks and catch a bus to an all-black school farther away. In 1951, her father, Oliver Brown, joined with other black parents in Topeka and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to sue the local board of education, challenging school segregation. NAACP lawyer Thurgood Marshall, who went on to become the Supreme Court’s first African American justice, argued that segregated schools could never be equal. The Supreme Court, in its unanimous opinion, agreed. The justices were influenced by the famous “doll experiments,” which demonstrated the psychological impacts of internalized racism on black children. The Court ruled that segregation itself was harmful and a violation of the constitutional right to equal protection under the law. The decision prompted a backlash across the South but also contributed to a watershed moment in the civil rights movement that struck down segregation laws during the 1960s.

Oliver Brown was a welder and assistant pastor whose daughter Linda was in the third grade when he joined in a lawsuit aimed at integrating her school district. Brown’s name is associated with this famous case simply because it was alphabetically first in the list of plaintiffs. After Brown , Linda attended integrated schools through college and has continued to speak out against segregation.

Thurgood Marshall (July 2, 1908 – January 24, 1993) was chief counsel for the NAACP, representing Brown and his fellow plaintiffs before the Court. He argued 32 cases before the Supreme Court, winning twenty-nine and earning the nickname “Mr. Civil Rights.” In 1967, Marshall became the first African American Supreme Court justice (1967 – 1991).

Earl Warren (March 19, 1891 – July 9, 1974) was a California lawyer, prosecutor and governor who became chief justice of the Supreme Court (1953 – 1969). He led the “Warren Court” in enacting a series of decisions, including Brown , that transformed parts of American law.

You are using an outdated browser no longer supported by Oyez. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

The Power of One Decision: Brown v. Board of Education

As the highest court in the land, the Supreme Court decides cases and controversies that relate to the Constitution and laws of the United States. Because the Court is a reactive institution, it does not seek complaints to resolve. Instead the Court relies on people to bring their concerns to it.

When minority students through legal representatives decided to take their challenge of the “separate but equal” doctrine to the Supreme Court, the 1954 decision handed down by the Court in Brown v. Board of Education and enforced by the executive branch, changed their lives and America forever.

This lesson is based on the Annenberg Classroom video “A Conversation on the Constitution: Brown v. Board of Education” in which Supreme Court Justices Sandra Day O’Connor, Anthony Kennedy and Stephen Breyer participate in a Q&A session with a group of high school students. The conversation revolves around the issues and arguments in Brown v. Board of Education . Through the lesson, students gain insight into decision-making at the Supreme Court, learn about the people behind the case, construct a persuasive argument, and evaluate the significance of Brown v. Board of Education .

The estimated time for this lesson is four class periods. It is aligned with the National Standards for Civics and Government.

Download the lesson plan

Standards Alignment

- National Standards for Civics and Government Grades 5-8

- National Standards for Civics and Government Grades 9-12

Related Resources

- Video: A Conversation on the Constitution with Justices Stephen Breyer, Anthony Kennedy and Sandra Day O'Connor: Brown v. Board of Education

- Book: Chapter 10: The Right to Freedom from Racial Discrimination

- Book: Chapter 13: Public School Desegregation

- Timeline: Fourteenth Amendment Timeline

Please contact the OCIO Help Desk for additional support.

Your issue id is: 11388970991774479760.

The Washington Informer

Black News, Commentary and Culture | The Washington Informer

National Museum of African American History to Commemorate 70th Anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

Sign up to stay connected

Get the top stories of the day around the DMV.

- WIN Daily Start your weekdays right with the most recent stories from the Washington Informer website. Once a day Monday-Friday.

- JPMorgan Chase Money Talks Presented with JPMorgan Chase, this financial education series is dedicated to bridging the racial wealth gap. Let's embark on a journey of healthy financial conversations together. Bi-Monthly.

- Our House D.C. Dive deep into our monthly exploration of the challenges and rewards of Black homeownership. Monthly.

- Deals & Offers Exclusive perks, updates, and events from The Washington Informer partners just for you.

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture will recognize the 70th anniversary of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision by the Supreme Court next month with a daylong public event.

The May 17 event, held in collaboration with the NAACP, will include several panel discussions, with one featuring participants of the Little Rock Nine, the first Black students to enter Little Rock Arkansas’ Central High School in 1957.

The event will take place at the museum’s Oprah Winfrey Theater from 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Registration is required.

On May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court delivered its unanimous 9-0 decision overturning the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson ruling as it applied to public education, stating that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

In a watershed moment for equality and democracy, racial segregation laws were declared in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, paving the way for integration, and winning a major victory for the burgeoning civil rights movement.

“The National Museum of African American History and Culture was founded to ensure that this story and other important chapters in the African American experience are never forgotten,” said Kevin Young, the museum’s Andrew W. Mellon director. “The road to desegregation in the United States was long and arduous. This anniversary stands as a testament to the tenacity and moral clarity of African American trailblazers who insisted on the power of education and refused to settle for the inherent injustice of ‘separate but equal.’”

For more information, go to nmaahc.si.edu, follow @NMAAHC on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram or call Smithsonian information at 202-633-1000.

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Plessy Vs. Ferguson: Brown V. Board of Education

This essay about the pivotal legal cases Plessy v. Ferguson and Brown v. Board of Education, which represent contrasting narratives in the struggle against racial segregation. Plessy upheld segregation under the “separate but equal” doctrine, perpetuating systemic injustice, while Brown challenged this precedent, leading to the eventual dismantling of segregation in public schools. The essay examines the legacies of these cases, highlighting their impact on American society and the ongoing quest for racial equality.

How it works

Within the mosaic of American jurisprudence, two seminal cases, Plessy v. Ferguson and Brown v. Board of Education, cast long shadows on the landscape of racial equality. These legal landmarks, though separated by decades, offer contrasting narratives in the struggle against segregation and discrimination.

Plessy v. Ferguson, etched into legal annals in 1896, epitomized the era’s prevailing racial attitudes. At its core lay Homer Plessy’s defiant act of boarding a whites-only railroad car, an act of civil disobedience against Louisiana’s Jim Crow laws.

Yet, the Supreme Court’s ruling validated the doctrine of “separate but equal,” effectively sanctifying racial segregation. This decision, like a gavel striking marble, resounded across the nation, institutionalizing racial division and emboldening discriminatory practices.

In stark contrast, the dawn of the 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education heralded a new era in the struggle for civil rights. Originating from disparate legal battles across America, the case coalesced around a singular premise: the inherent injustice of segregated public education. Chief Justice Earl Warren’s unanimous opinion delivered a resounding rebuke to the notion of “separate but equal,” laying the groundwork for the dismantling of segregation in schools and society at large.

The dichotomy between Plessy and Brown encapsulates a broader narrative of legal evolution and societal transformation. Plessy, a relic of its time, symbolizes the entrenched racism of the late 19th century, while Brown represents the burgeoning momentum of the mid-20th century civil rights movement. Together, they form a prism through which to examine the complexities of race, law, and social progress in America.

Plessy v. Ferguson’s enduring legacy is one of entrenched inequality and systemic injustice. Its validation of segregation emboldened discriminatory practices across the nation, relegating African Americans to second-class citizenship and perpetuating a cycle of racial subjugation. Despite subsequent challenges and critiques, the case remains a cautionary tale, reminding us of the enduring legacy of racial injustice in American history.

Conversely, Brown v. Board of Education stands as a beacon of hope and progress in the ongoing struggle for racial equality. By striking down the legal foundation of segregation in public schools, the Supreme Court’s decision paved the way for transformative change, challenging the status quo and inspiring generations of activists. Though implementation faced resistance and obstacles, Brown’s legacy endures as a testament to the power of legal advocacy and social mobilization in advancing the cause of justice.

The juxtaposition of these two cases underscores the dynamic nature of American jurisprudence and its capacity for both perpetuating and dismantling systemic injustices. From the halls of the Supreme Court to the streets of America, the struggle for racial equality continues, shaped by the lessons of the past and the aspirations of the future.

In conclusion, Plessy v. Ferguson and Brown v. Board of Education represent divergent paths in the journey toward racial equality in America. While Plessy entrenched segregation and sanctioned racial discrimination, Brown challenged the status quo and laid the groundwork for progress. Together, these cases offer a prism through which to examine the complexities of race, law, and social change in American society.

Cite this page

Plessy Vs. Ferguson: Brown V. Board Of Education. (2024, Apr 22). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/plessy-vs-ferguson-brown-v-board-of-education/

"Plessy Vs. Ferguson: Brown V. Board Of Education." PapersOwl.com , 22 Apr 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/plessy-vs-ferguson-brown-v-board-of-education/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Plessy Vs. Ferguson: Brown V. Board Of Education . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/plessy-vs-ferguson-brown-v-board-of-education/ [Accessed: 23 Apr. 2024]

"Plessy Vs. Ferguson: Brown V. Board Of Education." PapersOwl.com, Apr 22, 2024. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/plessy-vs-ferguson-brown-v-board-of-education/

"Plessy Vs. Ferguson: Brown V. Board Of Education," PapersOwl.com , 22-Apr-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/plessy-vs-ferguson-brown-v-board-of-education/. [Accessed: 23-Apr-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Plessy Vs. Ferguson: Brown V. Board Of Education . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/plessy-vs-ferguson-brown-v-board-of-education/ [Accessed: 23-Apr-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Case No. 23-0055

State of iowa v. clayton curtis brown.

The State seeks further review of the court of appeals decision affirming in part, reversing in part, and remanding Clayton Curtis Brown’s convictions for possession of a firearm by a felon, eluding while driving 25 over the speed limit and participating in a felony, and driving while barred as a habitual offender. The court of appeals found there was insufficient evidence to prove that Brown possessed the firearm. Further, because there was insufficient evidence for this count, the court determined he should also have been acquitted of eluding while driving 25 over the speed limit and participating in a felony.

State of Iowa

Clayton Curtis Brown

Attorney for the Applicant

Timothy M. Hau

Attorney for the Resister

Supreme court, oral argument schedule.

Mar 20, 2024 9:30 AM

Supreme Court Opinion

Opinion number:, date published:, court of appeals, court of appeals opinion.

Appeal from the Iowa District Court for Boone County, Derek J. Johnson, Judge. AFFIRMED IN PART, REVERSED IN PART, AND REMANDED. Considered by Bower, C.J., Chicchelly, J., and Potterfield, S.J. Opinion by Potterfield, S.J. (13 pages)

Clayton Brown appeals his convictions for possession of a firearm as a felon; eluding while exceeding the speed limit by twenty-five miles per hour (mph) and participating in a felony (i.e. being a felon in possession of a firearm, which is a class “D” felony); and driving while barred as an habitual offender. Brown argues (1) the district court should have granted his motion for mistrial after an officer testified in front of the jury that Brown had “convictions on his record”; (2) there is not substantial evidence to support the jury’s finding he was the person driving the car that eluded the officer; and (3) even if there was substantial evidence Brown was the driver during the chase, there was insufficient evidence he knowingly possessed the firearm that was later found tucked underneath the driver’s seat in the car. OPINION HOLDS: The district court did not abuse its discretion in denying the motion for mistrial and substantial evidence supports the jury’s finding Brown was the driver of the vehicle. We affirm Brown’s conviction for driving while barred as an habitual offender. But because there is insufficient evidence Brown knowingly possessed a firearm, we reverse his convictions for felon in possession of a firearm and eluding while exceeding the speed limit by twenty-five miles mph and participating in a felony. We remand for further proceedings on the lesser-included eluding charges.

Other Information

Date further review is granted:.

View archived opinions from prior to November 2017

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Board of Education of Topeka was a landmark 1954 Supreme Court case in which the justices ruled unanimously that racial segregation of children in public schools was unconstitutional. Brown v ...

The 1954 decision found that the historical evidence bearing on the issue was inconclusive. Brown v. Board of Education, case in which, on May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously (9-0) that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. It was one of the most important cases in the Court's history, and it helped ...

That is why the case is called Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, even though the case involved plaintiffs in multiple states. Most simply refer to it as Brown v. Board. The Supreme Court took the relatively unusual step in Brown v. Board of hearing oral arguments twice, once in 1953 and again in 1954. The second round of oral arguments was ...

In Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954) a unanimous Supreme Court declared that racial segregation in public schools is unconstitutional. The Court declared "separate" educational facilities "inherently unequal.". The case electrified the nation, and remains a landmark in legal history and a milestone in civil rights history.

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the segregated schools are otherwise equal in quality. The decision partially overruled the Court's 1896 decision Plessy v.Ferguson, which had held that racial segregation laws ...

The Browns appealed their case to the U.S. Supreme Court, stating that even if the facilities were similar, segregated schools could never be equal. The Court decided that state laws requiring separate but equal schools violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. Students in a segregated, one-room school in Waldorf, Maryland (1941)

Ferguson case. On May 17, 1954, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Earl Warren delivered the unanimous ruling in the landmark civil rights case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. State-sanctioned segregation of public schools was a violation of the 14th amendment and was therefore unconstitutional. This historic decision marked the end of ...

Overview:. Brown v. Board of Education (1954) was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision that struck down the "Separate but Equal" doctrine and outlawed the ongoing segregation in schools. The court ruled that laws mandating and enforcing racial segregation in public schools were unconstitutional, even if the segregated schools were "separate but equal" in standards.

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. No. 8. Decided October 8, 1952*. 344 U.S. 1. Syllabus. In two cases set for argument in October, laws of Kansas and South Carolina providing for racial segregation in public schools were challenged as violative of the Fourteenth Amendment. In another case raising the same question with respect to laws of ...

The Supreme Court's opinion in the Brown v. Board of Education case of 1954 legally ended decades of racial segregation in America's public schools. Chief Justice Earl Warren delivered the unanimous ruling in the landmark civil rights case. State-sanctioned segregation of public schools was a violation of the 14th Amendment and was therefore ...

Case Summary of Brown v. Board of Education: Oliver Brown was denied admission into a white school. As a representative of a class action suit, Brown filed a claim alleging that laws permitting segregation in public schools were a violation of the 14 th Amendment equal protection clause. After the District Court upheld segregation using Plessy v.

Board of Education (1954, 1955) The case that came to be known as Brown v. Board of Education was actually the name given to five separate cases that were heard by the U.S. Supreme Court concerning the separate but equal concept in public schools. These cases were Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka , Briggs v.

In the Kansas case, Brown v. Board of Education, the plaintiffs are Negro children of elementary school age residing in Topeka. They brought this action in the United States District Court for the District of Kansas to enjoin enforcement of a Kansas statute which permits, but does not require, cities of more than 15,000 population to maintain ...

Board of Education . Brown v. Board of Education (of Topeka), (1954) U.S. Supreme Court case in which the court ruled unanimously that racial segregation in public schools violated the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The amendment says that no state may deny equal protection of the laws to any person within its jurisdiction.

Board of Education case was brought, with their parents (L-R) Zelma Henderson, Oliver Brown, Sadie Emanuel, Lucinda Todd, and Lena Carper, 1953. In its landmark ruling, the Supreme Court didn't ...