Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Citing sources

- What Is an Annotated Bibliography? | Examples & Format

What Is an Annotated Bibliography? | Examples & Format

Published on March 9, 2021 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on August 23, 2022.

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that includes a short descriptive text (an annotation) for each source. It may be assigned as part of the research process for a paper , or as an individual assignment to gather and read relevant sources on a topic.

Scribbr’s free Citation Generator allows you to easily create and manage your annotated bibliography in APA or MLA style. To generate a perfectly formatted annotated bibliography, select the source type, fill out the relevant fields, and add your annotation.

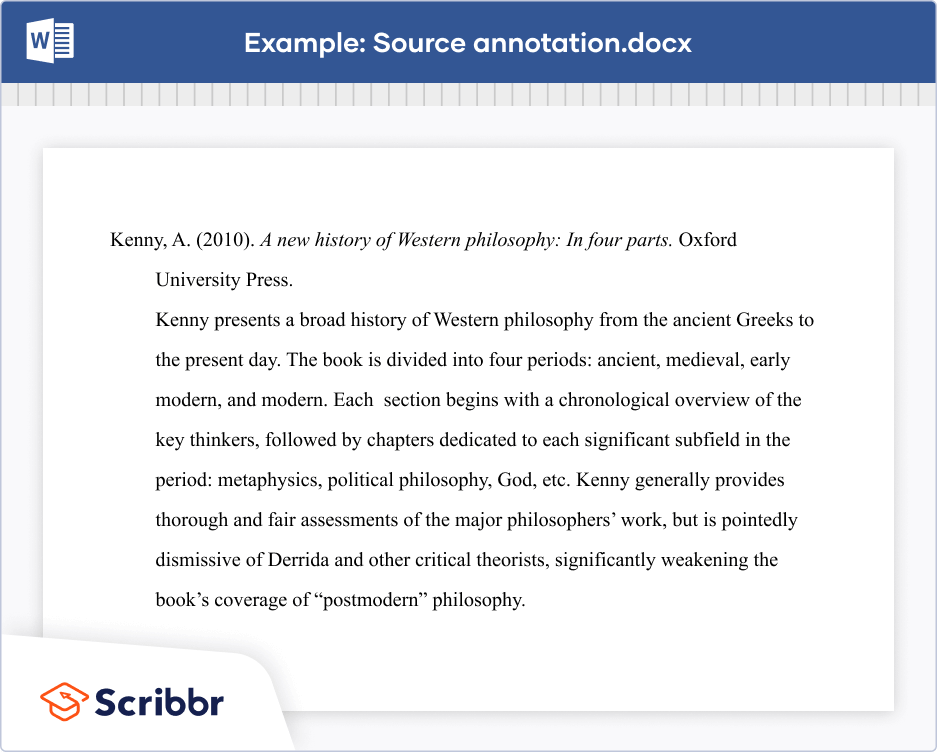

An example of an annotated source is shown below:

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Annotated bibliography format: apa, mla, chicago, how to write an annotated bibliography, descriptive annotation example, evaluative annotation example, reflective annotation example, finding sources for your annotated bibliography, frequently asked questions about annotated bibliographies.

Make sure your annotated bibliography is formatted according to the guidelines of the style guide you’re working with. Three common styles are covered below:

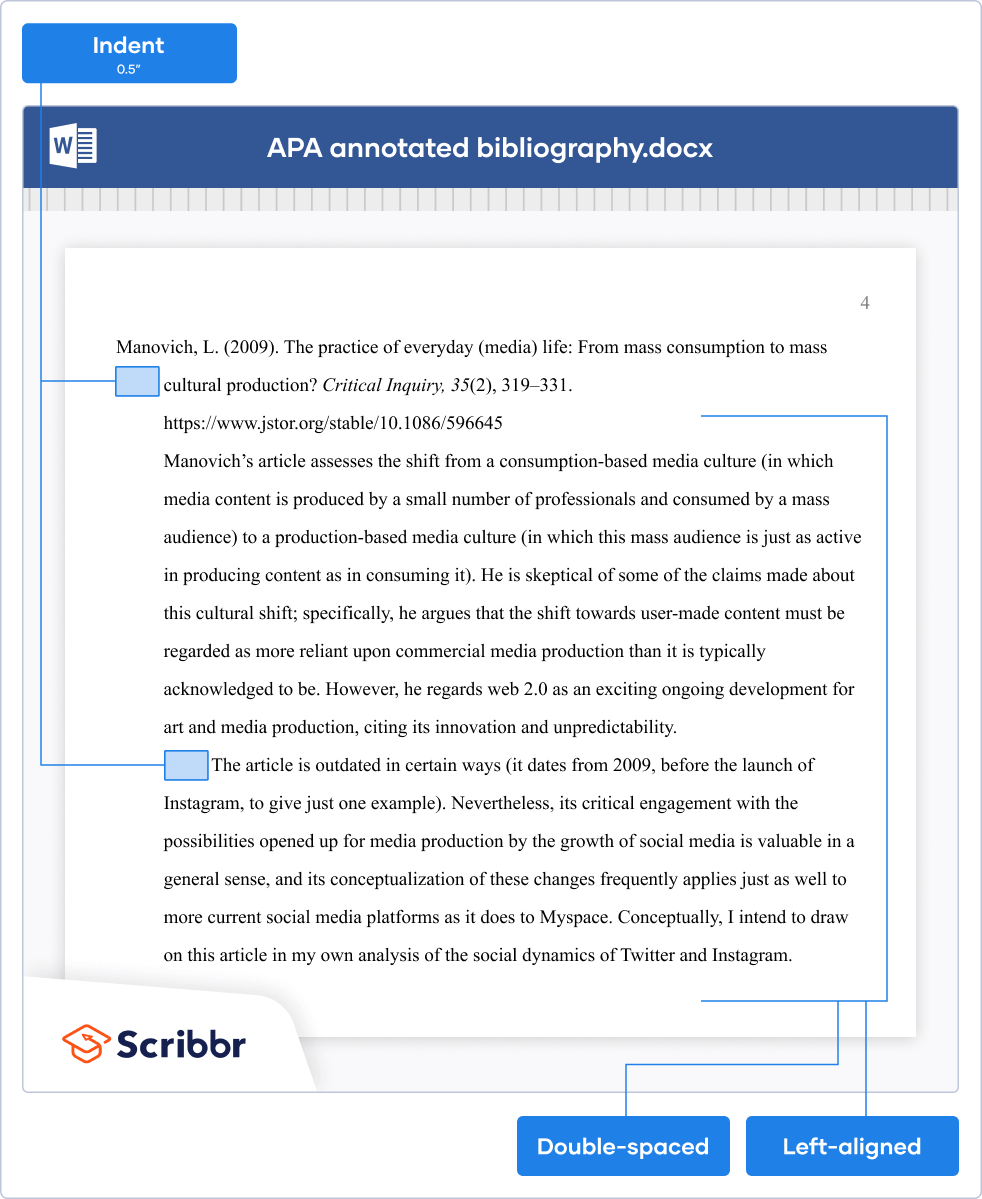

In APA Style , both the reference entry and the annotation should be double-spaced and left-aligned.

The reference entry itself should have a hanging indent . The annotation follows on the next line, and the whole annotation should be indented to match the hanging indent. The first line of any additional paragraphs should be indented an additional time.

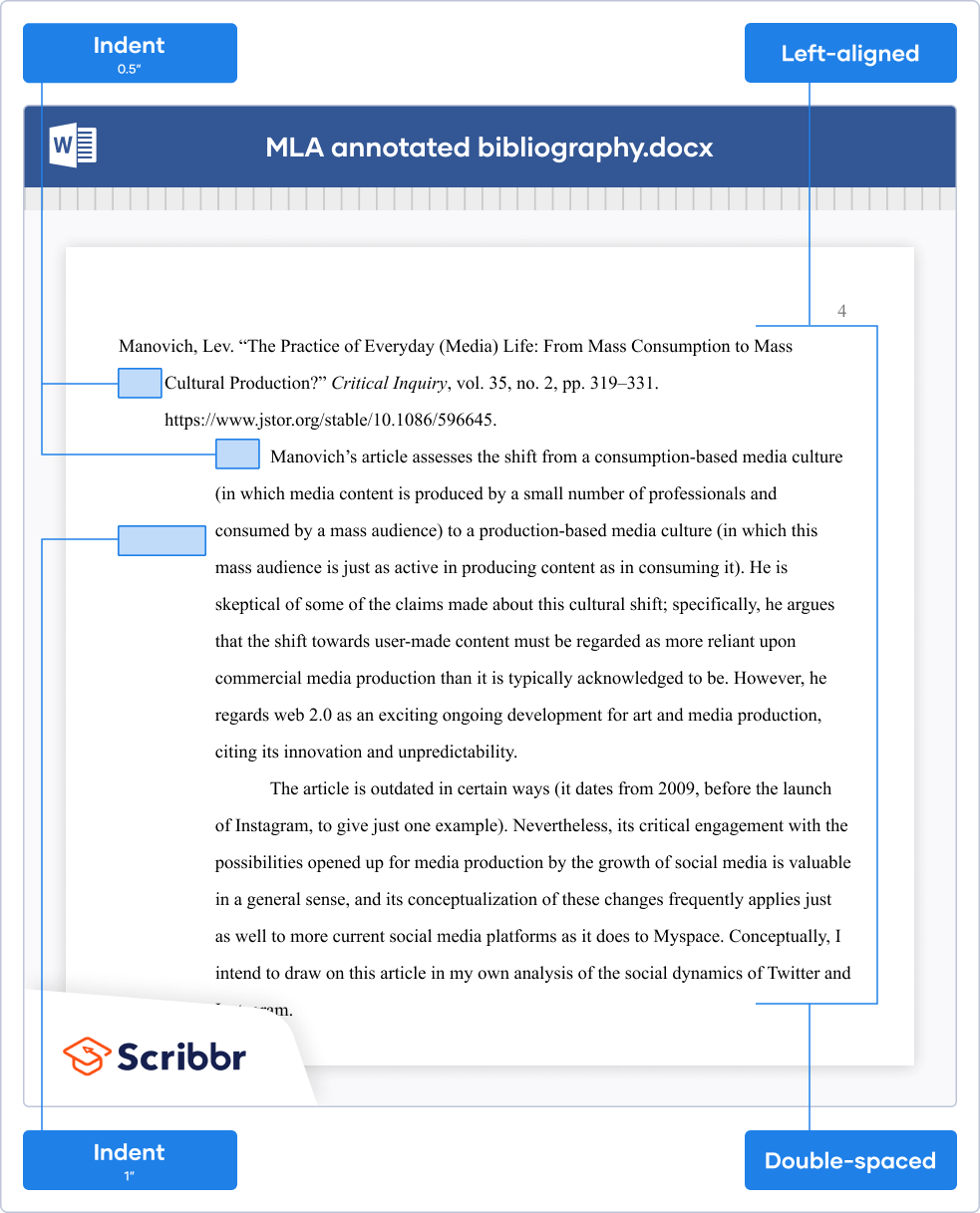

In an MLA style annotated bibliography , the Works Cited entry and the annotation are both double-spaced and left-aligned.

The Works Cited entry has a hanging indent. The annotation itself is indented 1 inch (twice as far as the hanging indent). If there are two or more paragraphs in the annotation, the first line of each paragraph is indented an additional half-inch, but not if there is only one paragraph.

Chicago style

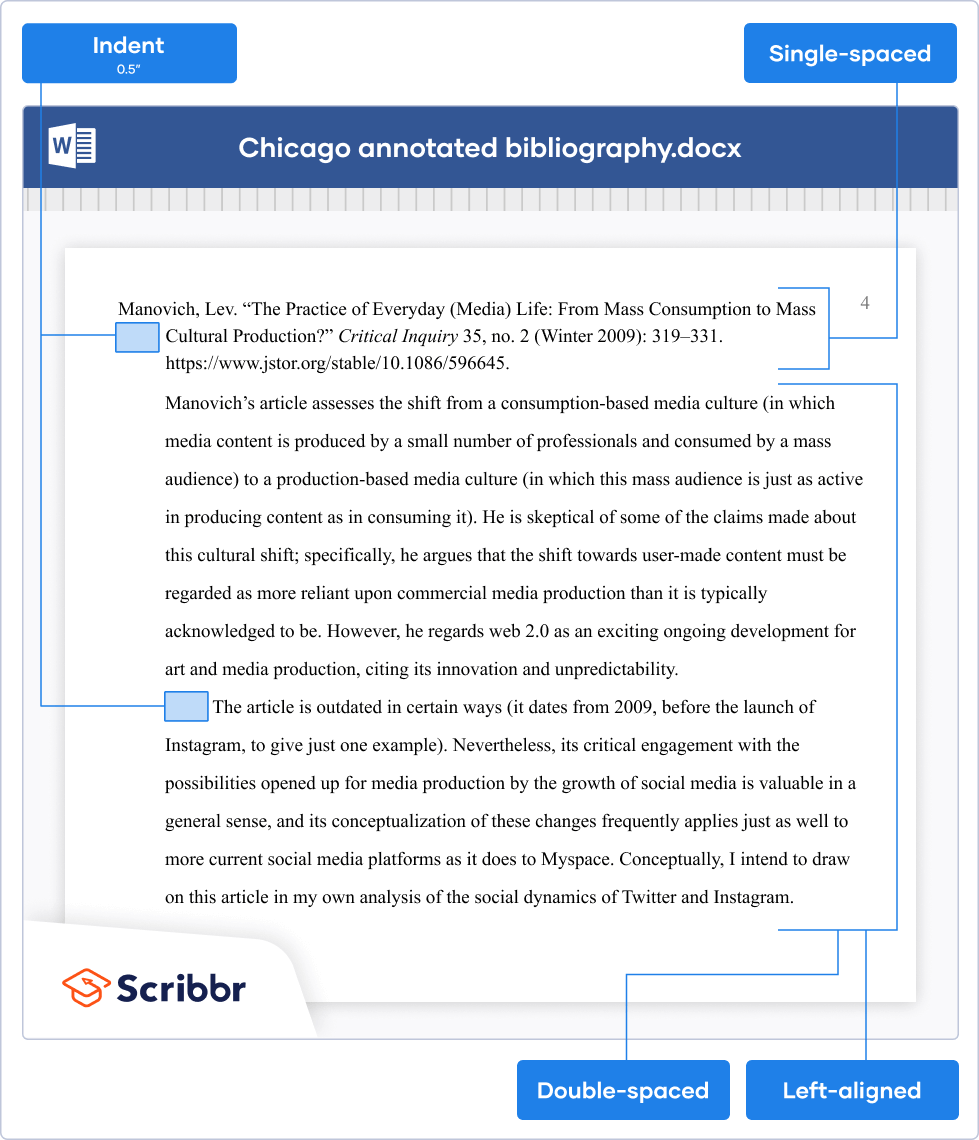

In a Chicago style annotated bibliography , the bibliography entry itself should be single-spaced and feature a hanging indent.

The annotation should be indented, double-spaced, and left-aligned. The first line of any additional paragraphs should be indented an additional time.

Scribbr Citation Checker New

The AI-powered Citation Checker helps you avoid common mistakes such as:

- Missing commas and periods

- Incorrect usage of “et al.”

- Ampersands (&) in narrative citations

- Missing reference entries

For each source, start by writing (or generating ) a full reference entry that gives the author, title, date, and other information. The annotated bibliography format varies based on the citation style you’re using.

The annotations themselves are usually between 50 and 200 words in length, typically formatted as a single paragraph. This can vary depending on the word count of the assignment, the relative length and importance of different sources, and the number of sources you include.

Consider the instructions you’ve been given or consult your instructor to determine what kind of annotations they’re looking for:

- Descriptive annotations : When the assignment is just about gathering and summarizing information, focus on the key arguments and methods of each source.

- Evaluative annotations : When the assignment is about evaluating the sources , you should also assess the validity and effectiveness of these arguments and methods.

- Reflective annotations : When the assignment is part of a larger research process, you need to consider the relevance and usefulness of the sources to your own research.

These specific terms won’t necessarily be used. The important thing is to understand the purpose of your assignment and pick the approach that matches it best. Interactive examples of the different styles of annotation are shown below.

A descriptive annotation summarizes the approach and arguments of a source in an objective way, without attempting to assess their validity.

In this way, it resembles an abstract , but you should never just copy text from a source’s abstract, as this would be considered plagiarism . You’ll naturally cover similar ground, but you should also consider whether the abstract omits any important points from the full text.

The interactive example shown below describes an article about the relationship between business regulations and CO 2 emissions.

Rieger, A. (2019). Doing business and increasing emissions? An exploratory analysis of the impact of business regulation on CO 2 emissions. Human Ecology Review , 25 (1), 69–86. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26964340

An evaluative annotation also describes the content of a source, but it goes on to evaluate elements like the validity of the source’s arguments and the appropriateness of its methods .

For example, the following annotation describes, and evaluates the effectiveness of, a book about the history of Western philosophy.

Kenny, A. (2010). A new history of Western philosophy: In four parts . Oxford University Press.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

A reflective annotation is similar to an evaluative one, but it focuses on the source’s usefulness or relevance to your own research.

Reflective annotations are often required when the point is to gather sources for a future research project, or to assess how they were used in a project you already completed.

The annotation below assesses the usefulness of a particular article for the author’s own research in the field of media studies.

Manovich, Lev. (2009). The practice of everyday (media) life: From mass consumption to mass cultural production? Critical Inquiry , 35 (2), 319–331. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/596645

Manovich’s article assesses the shift from a consumption-based media culture (in which media content is produced by a small number of professionals and consumed by a mass audience) to a production-based media culture (in which this mass audience is just as active in producing content as in consuming it). He is skeptical of some of the claims made about this cultural shift; specifically, he argues that the shift towards user-made content must be regarded as more reliant upon commercial media production than it is typically acknowledged to be. However, he regards web 2.0 as an exciting ongoing development for art and media production, citing its innovation and unpredictability.

The article is outdated in certain ways (it dates from 2009, before the launch of Instagram, to give just one example). Nevertheless, its critical engagement with the possibilities opened up for media production by the growth of social media is valuable in a general sense, and its conceptualization of these changes frequently applies just as well to more current social media platforms as it does to Myspace. Conceptually, I intend to draw on this article in my own analysis of the social dynamics of Twitter and Instagram.

Before you can write your annotations, you’ll need to find sources . If the annotated bibliography is part of the research process for a paper, your sources will be those you consult and cite as you prepare the paper. Otherwise, your assignment and your choice of topic will guide you in what kind of sources to look for.

Make sure that you’ve clearly defined your topic , and then consider what keywords are relevant to it, including variants of the terms. Use these keywords to search databases (e.g., Google Scholar ), using Boolean operators to refine your search.

Sources can include journal articles, books, and other source types , depending on the scope of the assignment. Read the abstracts or blurbs of the sources you find to see whether they’re relevant, and try exploring their bibliographies to discover more. If a particular source keeps showing up, it’s probably important.

Once you’ve selected an appropriate range of sources, read through them, taking notes that you can use to build up your annotations. You may even prefer to write your annotations as you go, while each source is fresh in your mind.

An annotated bibliography is an assignment where you collect sources on a specific topic and write an annotation for each source. An annotation is a short text that describes and sometimes evaluates the source.

Any credible sources on your topic can be included in an annotated bibliography . The exact sources you cover will vary depending on the assignment, but you should usually focus on collecting journal articles and scholarly books . When in doubt, utilize the CRAAP test !

Each annotation in an annotated bibliography is usually between 50 and 200 words long. Longer annotations may be divided into paragraphs .

The content of the annotation varies according to your assignment. An annotation can be descriptive, meaning it just describes the source objectively; evaluative, meaning it assesses its usefulness; or reflective, meaning it explains how the source will be used in your own research .

A source annotation in an annotated bibliography fulfills a similar purpose to an abstract : they’re both intended to summarize the approach and key points of a source.

However, an annotation may also evaluate the source , discussing the validity and effectiveness of its arguments. Even if your annotation is purely descriptive , you may have a different perspective on the source from the author and highlight different key points.

You should never just copy text from the abstract for your annotation, as doing so constitutes plagiarism .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2022, August 23). What Is an Annotated Bibliography? | Examples & Format. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/citing-sources/annotated-bibliography/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, evaluating sources | methods & examples, how to find sources | scholarly articles, books, etc., hanging indent | word & google docs instructions, what is your plagiarism score.

How to Prepare an Annotated Bibliography: The Annotated Bibliography

- The Annotated Bibliography

- Fair Use of this Guide

Explanation, Process, Directions, and Examples

What is an annotated bibliography.

An annotated bibliography is a list of citations to books, articles, and documents. Each citation is followed by a brief (usually about 150 words) descriptive and evaluative paragraph, the annotation. The purpose of the annotation is to inform the reader of the relevance, accuracy, and quality of the sources cited.

Annotations vs. Abstracts

Abstracts are the purely descriptive summaries often found at the beginning of scholarly journal articles or in periodical indexes. Annotations are descriptive and critical; they may describe the author's point of view, authority, or clarity and appropriateness of expression.

The Process

Creating an annotated bibliography calls for the application of a variety of intellectual skills: concise exposition, succinct analysis, and informed library research.

First, locate and record citations to books, periodicals, and documents that may contain useful information and ideas on your topic. Briefly examine and review the actual items. Then choose those works that provide a variety of perspectives on your topic.

Cite the book, article, or document using the appropriate style.

Write a concise annotation that summarizes the central theme and scope of the book or article. Include one or more sentences that (a) evaluate the authority or background of the author, (b) comment on the intended audience, (c) compare or contrast this work with another you have cited, or (d) explain how this work illuminates your bibliography topic.

Critically Appraising the Book, Article, or Document

For guidance in critically appraising and analyzing the sources for your bibliography, see How to Critically Analyze Information Sources . For information on the author's background and views, ask at the reference desk for help finding appropriate biographical reference materials and book review sources.

Choosing the Correct Citation Style

Check with your instructor to find out which style is preferred for your class. Online citation guides for both the Modern Language Association (MLA) and the American Psychological Association (APA) styles are linked from the Library's Citation Management page .

Sample Annotated Bibliography Entries

The following example uses APA style ( Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , 7th edition, 2019) for the journal citation:

Waite, L., Goldschneider, F., & Witsberger, C. (1986). Nonfamily living and the erosion of traditional family orientations among young adults. American Sociological Review, 51 (4), 541-554. The authors, researchers at the Rand Corporation and Brown University, use data from the National Longitudinal Surveys of Young Women and Young Men to test their hypothesis that nonfamily living by young adults alters their attitudes, values, plans, and expectations, moving them away from their belief in traditional sex roles. They find their hypothesis strongly supported in young females, while the effects were fewer in studies of young males. Increasing the time away from parents before marrying increased individualism, self-sufficiency, and changes in attitudes about families. In contrast, an earlier study by Williams cited below shows no significant gender differences in sex role attitudes as a result of nonfamily living.

This example uses MLA style ( MLA Handbook , 9th edition, 2021) for the journal citation. For additional annotation guidance from MLA, see 5.132: Annotated Bibliographies .

Waite, Linda J., et al. "Nonfamily Living and the Erosion of Traditional Family Orientations Among Young Adults." American Sociological Review, vol. 51, no. 4, 1986, pp. 541-554. The authors, researchers at the Rand Corporation and Brown University, use data from the National Longitudinal Surveys of Young Women and Young Men to test their hypothesis that nonfamily living by young adults alters their attitudes, values, plans, and expectations, moving them away from their belief in traditional sex roles. They find their hypothesis strongly supported in young females, while the effects were fewer in studies of young males. Increasing the time away from parents before marrying increased individualism, self-sufficiency, and changes in attitudes about families. In contrast, an earlier study by Williams cited below shows no significant gender differences in sex role attitudes as a result of nonfamily living.

Versión española

Tambíen disponible en español: Cómo Preparar una Bibliografía Anotada

Content Permissions

If you wish to use any or all of the content of this Guide please visit our Research Guides Use Conditions page for details on our Terms of Use and our Creative Commons license.

Reference Help

- Next: Fair Use of this Guide >>

- Last Updated: Sep 29, 2022 11:09 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.cornell.edu/annotatedbibliography

How to Write an Annotated Bibliography - APA Style (7th Edition)

What is an annotation, how is an annotation different from an abstract, what is an annotated bibliography, types of annotated bibliographies, descriptive or informative, analytical or critical, to get started.

An annotation is more than just a brief summary of an article, book, website, or other type of publication. An annotation should give enough information to make a reader decide whether to read the complete work. In other words, if the reader were exploring the same topic as you, is this material useful and if so, why?

While an abstract also summarizes an article, book, website, or other type of publication, it is purely descriptive. Although annotations can be descriptive, they also include distinctive features about an item. Annotations can be evaluative and critical as we will see when we look at the two major types of annotations.

An annotated bibliography is an organized list of sources (like a reference list). It differs from a straightforward bibliography in that each reference is followed by a paragraph length annotation, usually 100–200 words in length.

Depending on the assignment, an annotated bibliography might have different purposes:

- Provide a literature review on a particular subject

- Help to formulate a thesis on a subject

- Demonstrate the research you have performed on a particular subject

- Provide examples of major sources of information available on a topic

- Describe items that other researchers may find of interest on a topic

There are two major types of annotated bibliographies:

A descriptive or informative annotated bibliography describes or summarizes a source as does an abstract; it describes why the source is useful for researching a particular topic or question and its distinctive features. In addition, it describes the author's main arguments and conclusions without evaluating what the author says or concludes.

For example:

McKinnon, A. (2019). Lessons learned in year one of business. Journal of Legal Nurse Consulting , 30 (4), 26–28. This article describes some of the difficulties many nurses experience when transitioning from nursing to a legal nurse consulting business. Pointing out issues of work-life balance, as well as the differences of working for someone else versus working for yourself, the author offers their personal experience as a learning tool. The process of becoming an entrepreneur is not often discussed in relation to nursing, and rarely delves into only the first year of starting a new business. Time management, maintaining an existing job, decision-making, and knowing yourself in order to market yourself are discussed with some detail. The author goes on to describe how important both the nursing professional community will be to a new business, and the importance of mentorship as both the mentee and mentor in individual success that can be found through professional connections. The article’s focus on practical advice for nurses seeking to start their own business does not detract from the advice about universal struggles of entrepreneurship makes this an article of interest to a wide-ranging audience.

An analytical or critical annotation not only summarizes the material, it analyzes what is being said. It examines the strengths and weaknesses of what is presented as well as describing the applicability of the author's conclusions to the research being conducted.

Analytical or critical annotations will most likely be required when writing for a college-level course.

McKinnon, A. (2019). Lessons learned in year one of business. Journal of Legal Nurse Consulting , 30 (4), 26–28. This article describes some of the difficulty many nurses experience when transitioning from nursing to a nurse consulting business. While the article focuses on issues of work-life balance, the differences of working for someone else versus working for yourself, marketing, and other business issues the author’s offer of only their personal experience is brief with few or no alternative solutions provided. There is no mention throughout the article of making use of other research about starting a new business and being successful. While relying on the anecdotal advice for their list of issues, the author does reference other business resources such as the Small Business Administration to help with business planning and professional organizations that can help with mentorships. The article is a good resource for those wanting to start their own legal nurse consulting business, a good first advice article even. However, entrepreneurs should also use more business research studies focused on starting a new business, with strategies against known or expected pitfalls and issues new businesses face, and for help on topics the author did not touch in this abbreviated list of lessons learned.

Now you are ready to begin writing your own annotated bibliography.

- Choose your sources - Before writing your annotated bibliography, you must choose your sources. This involves doing research much like for any other project. Locate records to materials that may apply to your topic.

- Review the items - Then review the actual items and choose those that provide a wide variety of perspectives on your topic. Article abstracts are helpful in this process.

- The purpose of the work

- A summary of its content

- Information about the author(s)

- For what type of audience the work is written

- Its relevance to the topic

- Any special or unique features about the material

- Research methodology

- The strengths, weaknesses or biases in the material

Annotated bibliographies may be arranged alphabetically or chronologically, check with your instructor to see what he or she prefers.

Please see the APA Examples page for more information on citing in APA style.

- Last Updated: Aug 8, 2023 11:27 AM

- URL: https://libguides.umgc.edu/annotated-bibliography-apa

Annotated Bibliographies

What Is An Annotated Bibliography?

What is an annotated bibliography.

An annotated bibliography is a list of citations (references) to books, articles, and documents followed by a brief summary, analysis or evaluation, usually between 100-300 words, of the sources that are cited in the paper. This summary provides a description of the contents of the source and may also include evaluative comments, such as the relevance, accuracy and quality of the source. These summaries are known as annotations.

- Annotated bibliographies are completed before a paper is written

- They can be stand-along assignments

- They can be used as a reference tool as a person works on their paper

Annotations vs. Abstracts

Abstracts are the descriptive summaries of article contents found at the beginning of scholarly journal articles that are written by the article author(s) or editor. Their purpose is to inform a reader about the topic, methodology, results and conclusion of the research of the article's author(s). The summaries are provided so that a researcher can determine whether or not the article may have information of interest to them. Abstracts do not serve an evaluative purpose.

Annotations found in bibliographies are evaluations of sources cited in a paper. They describe a work, but also critique the source by examining the author’s point of view, the strengths and weakness of the research or article hypothesis or how well the author presented their research or findings.

How to write an annotated bibliography

The creation of an annotated bibliography is a three-step process. It starts with finding and evaluating sources for your paper. Next is choosing the type or category of annotation, then writing the annotation for each different source. The final step is to choose a citation style for the bibliography.

Types of Annotated Bibliographies

Types of Annotations

Annotations come in different types, the one to use depends on the instructor’s assignment. Annotations can be descriptive, a summary, or an evaluation or a combination of descriptive and evaluation.

Descriptive/Summarizing Annotations

There are two kinds of descriptive or summarizing annotations, informative or indicative, depending on what is most important for a reader to learn about a source. Descriptive/summarizing annotations provide a brief overview or summary of the source. This can include a description of the contents and a statement of the main argument or position of the article as well as a summary of the main points. It may also describe why the source would be useful for the paper’s topic or question.

Indicative annotations provide a quick overview of the source, the kinds of questions/topics/issues or main points that are addressed by the source, but do not include information from the argument or position itself.

Informative annotations, like indicative annotations, provide a brief summary of the source. In addition, an informative annotation identifies the hypothesis, results, and conclusions presented by the source. When appropriate, they describe the author’s methodology or approach to the topic under discussion. However, they do not provide information about the sources usefulness to the paper or contains analytical or critical information about the source’s quality.

Evaluative Annotations (also known as critical or analytical)

Evaluative annotations go beyond just summarizing the source and listing out it’s key points, but also analyzes the content. It looks at the strengths and weaknesses of the article’s argument, the reliability of the presented information as well as any biases of the author. It talks about how the source may be useful to a particular field of study or the person’s research project.

Combination Annotations

Combination annotations “combine” aspects from indicative/informative and evaluative annotations and are the most common category of annotated bibliography. Combination annotations include one to two sentences summarizing or describing content, in addition to one or more sentences providing an critical evaluation.

Writing Style for Annotations

Annotations typically follow three specific formats depending on how long they are.

- Phrases – Short phrases providing the information in a quick, concise manner.

- Sentences – Complete sentences with proper punctuation and grammar, but are short and concise.

- Paragraphs – Longer annotations break the information out into different paragraphs. This format is very effective for combination annotations.

To sum it up:

An annotation may include the following information:

- A brief summary or overview of the source content

- The source’s strengths and weaknesses in presenting the argument or position

- Its conclusions

- Why the source is relevant in to field of study of the paper

- Its relationships to other studies in the field

- An evaluation of the research methodology (if applicable)

- Information about the author’s background and potential biases

- Conclusions about the usefulness of the source for the paper

Critically Analyzing Articles

In order to write an annotation for a paper source, you need to first read and then critically analyze it:

- Try to identify the topic of the source -- what is it about and is it clearly stated.

- See if you can identify the purpose of the author(s) in doing the research or writing about the topic. Is it to survey and summarize research on a topic? Is the author(s) presenting an argument based on previous research, or refuting previously published research?

- Identify the research methods used and try to identify whether they appear to be suitable or not for the stated purpose of the research.

- Was the research reported in a consistent or clear manner? Or, was the author's argument/position presented in a consistent or convincing manner? Did the author(s) fail to acknowledge and explain any limitations?

- Was the logic of the research/argument claims properly supported with convincing evidence/analysis/data? Did you spot any fallacies?

- Check whether the author(s) refers to other research and if similar studies have been done.

- If illustrations or charts are used, are they effective in presenting information?

- Analyze the sources that were used by the author(s). Did the author(s) miss any important studies they should have considered?

- Your opinion of the source -- do you agree with or are convinced of the findings?

- Your estimation of the source’s contribution to knowledge and its implications or applications to the field of study.

Worksheet for Taking Notes for Critical Analysis of Sources/Articles

Additional Resources:

Hofmann, B., Magelssen, M. In pursuit of goodness in bioethics: analysis of an exemplary article. BMC Med Ethics 19, 60 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-018-0299-9

Jansen, M., & Ellerton, P. (2018). How to read an ethics paper. Journal of Medical Ethics, 44(12), 810-813. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2018-104997

Research & Learning Services, Olin Library, Cornell University Library Critically Analyzing Information Sources: Critical Appraisal and Analysis

Formatting An Annotated Bibliography

How do I format my annotated bibliography?

An annotated bibliography entry consists of two components: the Citation and the Annotation.

The citation should be formatted in the bibliographic style that your instructor has requested for the paper. Some common citation styles include APA, MLA, and Chicago. For more information on citation styles, see Writing Guides, Style Manuals and the Publication Process in the Biological & Health Sciences .

Many databases (e.g., PubMed, Academic Search Premier, Library Search on library homepage, and Google Scholar) offer the option of creating your references in various citation styles.

Look for the "cite" link -- see examples for the following resources:

University of Minnesota Library Search

Google Scholar

Sample Annotated Bibliography Entries

An example of an Evaluative Annotation , APA style (7th ed). (sample from University Libraries, University of Nevada ).

APA does not have specific formatting rules for annotations, just for the citation and bibliography.

Maak, T. (2007). Responsible leadership, stakeholder engagement, and the emergence of social capital. Journal of Business Ethics, 74, 329-343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9510-5

This article focuses on the role of social capital in responsible leadership. It looks at both the social networks that a leader builds within an organization, and the links that a leader creates with external stakeholders. Maak’s main aim with this article seems to be to persuade people of the importance of continued research into the abilities that a leader requires and how they can be acquired. The focus on the world of multinational business means that for readers outside this world many of the conclusions seem rather obvious (be part of the solution not part of the problem). In spite of this, the article provides useful background information on the topic of responsible leadership and definitions of social capital which are relevant to an analysis of a public servant.

An example of an Evaluative Annotation , MLA Style (10th ed), (sample from Columbia College, Vancouver, Canada )

MLA style requires double-spacing (not shown here) and paragraph indentations.

London, Herbert. “Five Myths of the Television Age.” Television Quarterly, vol. 10, no. 1, Mar. 1982, pp. 81-69.

Herbert London, the Dean of Journalism at New York University and author of several books and articles, explains how television contradicts five commonly believed ideas. He uses specific examples of events seen on television, such as the assassination of John Kennedy, to illustrate his points. His examples have been selected to contradict such truisms as: “seeing is believing”; “a picture is worth a thousand words”; and “satisfaction is its own reward.” London uses logical arguments to support his ideas which are his personal opinion. He does not refer to any previous works on the topic. London’s style and vocabulary would make the article of interest to any reader. The article clearly illustrates London’s points, but does not explore their implications leaving the reader with many unanswered questions.

Additional Resources

University Libraries Tutorial -- Tutorial: What are citations? Completing this tutorial you will:

- Understand what citations are

- Recognize why they are important

- Create and use citations in your papers and other scholarly work

University of Minnesota Resources

Beatty, L., & Cochran, C. (2020). Writing the annotated bibliography : A guide for students & researchers . New York, NY: Routledge. [ebook]

Efron, S., Ravid, R., & ProQuest. (2019). Writing the literature review : A practical guide . New York: The Guilford Press. [ebook -- see Chapter 6 on Evaluating Research Articles]

Center for Writing: Student Writing Support

- Critical reading strategies

- Common Writing Projects (includes resources for literature reviews & analyzing research articles)

Resources from Other Libraries

Annotated Bibliographies (The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

Writing An Annotated Bibliography (University of Toronto)

Annotated Bibliographies (Purdue Writing Lab, Purdue University)

Annotated Bibliography (UNSW Sydney)

What is an annotated bibliography? (Santiago Canyon College Library): Oct 17, 2017. 3:47 min.

Writing an annotated bibliography (EasyBib.com) Oct 22, 2020. 4:53 min.

Creating an annotated bibliography (Laurier University Library, Waterloo, Ontario)/ Apr 3, 2019, 3:32 min.

How to create an annotated bibliography: MLA (JamesTheDLC) Oct 23, 2019. 3:03 min.

Citing Sources

Introduction

Citations are brief notations in the body of a research paper that point to a source in the bibliography or references cited section.

If your paper quotes, paraphrases, summarizes the work of someone else, you need to use citations.

Citation style guides such as APA, Chicago and MLA provide detailed instructions on how citations and bibliographies should be formatted.

Health Sciences Research Toolkit

Resources, tips, and guidelines to help you through the research process., finding information.

Library Research Checklist Helpful hints for starting a library research project.

Search Strategy Checklist and Tips Helpful tips on how to develop a literature search strategy.

Boolean Operators: A Cheat Sheet Boolean logic (named after mathematician George Boole) is a system of logic to designed to yield optimal search results. The Boolean operators, AND, OR, and NOT, help you construct a logical search. Boolean operators act on sets -- groups of records containing a particular word or concept.

Literature Searching Overview and tips on how to conduct a literature search.

Health Statistics and Data Sources Health related statistics and data sources are increasingly available on the Internet. They can be found already neatly packaged, or as raw data sets. The most reliable data comes from governmental sources or health-care professional organizations.

Evaluating Information

Primary, Secondary and Tertiary Sources in the Health Sciences Understand what are considered primary, secondary and tertiary sources.

Scholarly vs Popular Journals/Magazines How to determine what are scholarly journals vs trade or popular magazines.

Identifying Peer-Reviewed Journals A “peer-reviewed” or “refereed” journal is one in which the articles it contains have been examined by people with credentials in the article’s field of study before it is published.

Evaluating Web Resources When searching for information on the Internet, it is important to be aware of the quality of the information being presented to you. Keep in mind that anyone can host a web site. To be sure that the information you are looking at is credible and of value.

Conducting Research Through An Anti-Racism Lens This guide is for students, staff, and faculty who are incorporating an anti-racist lens at all stages of the research life cycle.

Understanding Research Study Designs Covers case studies, randomized control trials, systematic reviews and meta-analysis.

Qualitative Studies Overview of what is a qualitative study and how to recognize, find and critically appraise.

Writing and Publishing

Citing Sources Citations are brief notations in the body of a research paper that point to a source in the bibliography or references cited section.

Structure of a Research Paper Reports of research studies usually follow the IMRAD format. IMRAD (Introduction, Methods, Results, [and] Discussion) is a mnemonic for the major components of a scientific paper. These elements are included in the overall structure of a research paper.

Top Reasons for Non-Acceptance of Scientific Articles Avoid these mistakes when preparing an article for publication.

Annotated Bibliographies Guide on how to create an annotated bibliography.

Writing guides, Style Manuals and the Publication Process in the Biological and Health Sciences Style manuals, citation guides as well as information on public access policies, copyright and plagiarism.

Research Strategies

- Reference Resources

- News Articles

- Scholarly Sources

- Search Strategy

- OneSearch Tips

- Evaluating Information

- Revising & Polishing

- Presentations & Media

- MLA 9th Citation Style

- APA 7th Citation Style

- Other Citation Styles

- Citation Managers

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review How to

What is An Annotated Bibliography?

An annotated bibliography is a list of sources (books, articles, websites, etc.) with short paragraph about each source. An annotated bibliography is sometimes a useful step before drafting a research paper, or it can stand alone as an overview of the research available on a topic.

Each source in the annotated bibliography has a citation - the information a reader needs to find the original source, in a consistent format to make that easier. These consistent formats are called citation styles. The most common citation styles are MLA (Modern Language Association) for humanities, and APA (American Psychological Association) for social sciences.

Annotations are about 4 to 6 sentences long (roughly 150 words), and address:

- Main focus or purpose of the work

- Usefulness or relevance to your research topic

- Special features of the work that were unique or helpful

- Background and credibility of the author

- Conclusions or observations reached by the author

- Conclusions or observations reached by you

Annotations versus Abstracts

Many scholarly articles start with an abstract, which is the author's summary of the article to help you decide whether you should read the entire article. This abstract is not the same thing as an annotation. The annotation needs to be in your own words, to explain the relevance of the source to your particular assignment or research question.

Annotated Bibliography video

MLA 9th Annotated Bibliography Examples

Ontiveros, Randy J. In the Spirit of a New People: The Cultural Politics of the Chicano Movement . New York UP, 2014.

This book analyzes the journalism, visual arts, theater, and novels of the Chicano movement from 1960 to the present as articulations of personal and collective values. Chapter 3 grounds the theater of El Teatro Campesino in the labor and immigrant organizing of the period, while Chapter 4 situates Sandra Cisneros’s novel Caramelo in the struggles of Chicana feminists to be heard in the traditional and nationalist elements of the Chicano movement. Ontiveros provides a powerful and illuminating historical context for the literary and political texts of the movement.

Journal article

Alvarez, Nadia, and Jack Mearns. “The Benefits of Writing and Performing in the Spoken Word Poetry Community.” The Arts in Psychotherapy , vol. 41, no. 3, July 2014, pp. 263-268. ScienceDirect , https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2014.03.004 .

Spoken word poetry is distinctive because it is written to be performed out loud, in person, by the poet. The ten poets interviewed by these authors describe “a reciprocal relationship between the audience and the poet” created by that practice of performance. To build community, spoken word poets keep metaphor and diction relatively simple and accessible. Richness is instead built through fragmented stories that coalesce into emotional narratives about personal and community concerns. This understanding of poets’ intentions illuminates their recorded performances.

*Note, citations have a .5 hanging indent and the annotations have a 1 inch indent.

- MLA 9th Sample Annotated Bibliography

APA 7th Annotated Bibliography Examples

Alvarez, N. & Mearns, J. (2014). The benefits of writing and performing in the spoken word poetry community. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 41 (3), 263-268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2014.03.004 Prior research has shown narrative writing to help with making meaning out of trauma. This article uses grounded theory to analyze semi-structured interviews with ten spoken word poets. Because spoken word poetry is performed live, it creates personal and community connections that enhance the emotional development and resolution offered by the practice of writing. The findings are limited by the small, nonrandom sample (all the participants were from the same community).

- APA 7th Sample Annotated Bibliography

- << Previous: Citation Managers

- Next: Literature Review How to >>

- Last Updated: Apr 8, 2024 9:46 AM

- URL: https://libguides.csun.edu/research-strategies

Report ADA Problems with Library Services and Resources

- Research Guides

- CECH Library

How to Write an Annotated Bibliography

Writing annotations.

- Introduction

- New RefWorks

- Formatting Citations

- Sample Annotated Bibliographies

An annotation is a brief note following each citation listed on an annotated bibliography. The goal is to briefly summarize the source and/or explain why it is important for a topic. They are typically a single concise paragraph, but might be longer if you are summarizing and evaluating.

Annotations can be written in a variety of different ways and it’s important to consider the style you are going to use. Are you simply summarizing the sources, or evaluating them? How does the source influence your understanding of the topic? You can follow any style you want if you are writing for your own personal research process, but consult with your professor if this is an assignment for a class.

Annotation Styles

- Combined Informative/Evaluative Style - This style is recommended by the library as it combines all the styles to provide a more complete view of a source. The annotation should explain the value of the source for the overall research topic by providing a summary combined with an analysis of the source.

Aluedse, O. (2006). Bullying in schools: A form of child abuse in schools. Educational Research Quarterly , 30 (1), 37.

The author classifies bullying in schools as a “form of child abuse,” and goes well beyond the notion that schoolyard bullying is “just child’s play.” The article provides an in-depth definition of bullying, and explores the likelihood that school-aged bullies may also experience difficult lives as adults. The author discusses the modern prevalence of bullying in school systems, the effects of bullying, intervention strategies, and provides an extensive list of resources and references.

Statistics included provide an alarming realization that bullying is prevalent not only in the United States, but also worldwide. According to the author, “American schools harbor approximately 2.1 million bullies and 2.7 million victims.” The author references the National Association of School Psychologists and quotes, “Thus, one in seven children is a bully or a target of bullying.” A major point of emphasis centers around what has always been considered a “normal part of growing up” versus the levels of actual abuse reached in today’s society.

The author concludes with a section that addresses intervention strategies for school administrators, teachers, counselors, and school staff. The concept of school staff helping build students’ “social competence” is showcased as a prevalent means of preventing and reducing this growing social menace. Overall, the article is worthwhile for anyone interested in the subject matter, and provides a wealth of resources for researching this topic of growing concern.

(Renfrow & Teuton, 2008)

- Informative Style - Similar to an abstract, this style focuses on the summarizing the source. The annotation should identify the hypothesis, results, and conclusions presented by the source.

Plester, B., Wood, C, & Bell, V. (2008). Txt msg n school literacy: Does texting and knowledge of text abbreviations adversely affect children's literacy attainment? Literacy , 42(3), 137-144.

Reports on two studies that investigated the relationship between children's texting behavior, their knowledge of text abbreviations, and their school attainment in written language skills. In Study One, 11 to 12 year-old children reported their texting behavior and translated a standard English sentence into a text message and vice versa. In Study Two, children's performance on writing measures were examined more specifically, spelling proficiency was also assessed, and KS2 Writing scores were obtained. Positive correlations between spelling ability and performance on the translation exercise were found, and group-based comparisons based on the children's writing scores also showed that good writing attainment was associated with greater use of texting abbreviations (textisms), although the direction of this association is not clear. Overall, these findings suggest that children's knowledge of textisms is not associated with poor written language outcomes for children in this age range.

(Beach et al., 2009)

- Evaluative Style - This style analyzes and critically evaluates the source. The annotation should comment on the source's the strengths, weaknesses, and how it relates to the overall research topic.

Amott, T. (1993). Caught in the Crisis: Women in the U.S. Economy Today . New York: Monthly Review Press.

A very readable (140 pp) economic analysis and information book which I am currently considering as a required collateral assignment in Economics 201. Among its many strengths is a lucid connection of "The Crisis at Home" with the broader, macroeconomic crisis of the U.S. working class (which various other authors have described as the shrinking middle class or the crisis of de-industrialization).

(Papadantonakis, 1996)

- Indicative Style - This style of annotation identifies the main theme and lists the significant topics included in the source. Usually no specific details are given beyond the topic list .

Example:

Gambell, T.J., & Hunter, D. M. (1999). Rethinking gender differences in literacy. Canadian Journal of Education , 24(1) 1-16.

Five explanations are offered for recently assessed gender differences in the literacy achievement of male and female students in Canada and other countries. The explanations revolve around evaluative bias, home socialization, role and societal expectations, male psychology, and equity policy.

(Kerka & Imel, 2004)

Beach, R., Bigelow, M., Dillon, D., Dockter, J., Galda, L., Helman, L., . . . Janssen, T. (2009). Annotated Bibliography of Research in the Teaching of English. Research in the Teaching of English, 44 (2), 210-241. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/27784357

Kerka, S., & Imel, S. (2004). Annotated bibliography: Women and literacy. Women's Studies Quarterly, 32 (1), 258-271. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/233645656?accountid=2909

Papadantonakis, K. (1996). Selected Annotated Bibliography for Economists and Other Social Scientists. Women's Studies Quarterly, 24 (3/4), 233-238. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40004384

Renfrow, T.G., & Teuton, L.M. (2008). Schoolyard bullying: Peer victimization an annotated bibliography. Community & Junior College Libraries, 14(4), 251-275. doi:10.1080/02763910802336407

- << Previous: Formatting Citations

- Next: Sample Annotated Bibliographies >>

- Last Updated: Feb 27, 2023 10:50 AM

- URL: https://guides.libraries.uc.edu/annotated_bibliography

University of Cincinnati Libraries

PO Box 210033 Cincinnati, Ohio 45221-0033

Phone: 513-556-1424

Contact Us | Staff Directory

University of Cincinnati

Alerts | Clery and HEOA Notice | Notice of Non-Discrimination | eAccessibility Concern | Privacy Statement | Copyright Information

© 2021 University of Cincinnati

How to Write a Research Paper: Annotated Bibliography

- Anatomy of a Research Paper

- Developing a Research Focus

- Background Research Tips

- Searching Tips

- Scholarly Journals vs. Popular Journals

- Thesis Statement

- Annotated Bibliography

- Citing Sources

- Evaluating Sources

- Literature Review

- Academic Integrity

- Scholarship as Conversation

- Understanding Fake News

- Data, Information, Knowledge

What is an Annotated Bibliography?

UMary Writing Center

Check out the resources available from the Writing Center .

Write an Annotated Bibliography

What is an annotated bibliography?

It is a list of citations for various books, articles, and other sources on a topic.

An annotation is a short summary and/or critical evaluation of a source.

Annotated bibliographies answer the question: "What would be the most relevant, most useful, or most up-to-date sources for this topic?"

Annotated bibliographies can be part of a larger research project, or can be a stand-alone report in itself.

Annotation versus abstracts

An abstract is a paragraph at the beginning of the paper that discusses the main point of the original work. They typically do not include evaluation comments.

Annotations can either be descriptive or evaluative. The annotated bibliography looks like a works cited page but includes an annotation after each source cited.

Types of Annotations:

Descriptive Annotations: Focuses on description. Describes the source by answering the following questions.

Who wrote the document?

What does the document discuss?

When and where was the document written?

Why was the document produced?

How was it provided to the public?

Evaluative Annotations: Focuses on description and evaluation. Includes a summary and critically assess the work for accuracy, relevance, and quality.

Evaluative annotations help you learn about your topic, develop a thesis statement, decide if a specific source will be useful for your assignment, and determine if there is enough valid information available to complete your project.

What does the annotation include?

Depending on your assignment and style guide, annotations may include some or all of the following information.

- Should be no more than 150 words or 4 to 6 sentences long.

- What is the main focus or purpose of the work?

- Who is the intended audience?

- How useful or relevant was the article to your topic?

- Was there any unique features that useful to you?

- What is the background and credibility of the author?

- What are any conclusions or observations that your reached about the article?

Which citation style to use?

There are many styles manuals with specific instructions on how to format your annotated bibliography. This largely depends on what your instructor prefers or your subject discipline. Check out our citation guides for more information.

Additional Information

Why doesn't APA have an official APA-approved format for annotated bibliographies?

Always consult your instructor about the format of an annotated bibliography for your class assignments. These guides provide you with examples of various styles for annotated bibliographies and they may not be in the format required by your instructor.

Citation Examples and Annotations

Book Citation with Descriptive Annotation

Liroff, R. A., & G. G. Davis. (1981). Protecting open space: Land use control in the Adirondack Park. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger.

This book describes the implementation of regional planning and land use regulation in the Adirondack Park in upstate New York. The authors provide program evaluations of the Adirondack Park Agencys regulatory and local planning assistance programs.

Journal Article Citation with Evaluative Annotation

Gottlieb, P. D. (1995). The “golden egg” as a natural resource: Toward a normative theory of growth management. Society and Natural Resources, 8, (5): 49-56.

This article explains the dilemma faced by North American suburbs, which demand both preservation of local amenities (to protect quality of life) and physical development (to expand the tax base). Growth management has been proposed as a policy solution to this dilemma. An analogy is made between this approach and resource economics. The author concludes that the growth management debate raises legitimate issues of sustainability and efficiency.

Examples were taken from http://lib.calpoly.edu/support/how-to/write-an-annotated-bibliography/#samples

Book Citation

Lee, Seok-hoon, Yong-pil Kim, Nigel Hemmington, and Deok-kyun Yun. “Competitive Service Quality Improvement (CSQI): A Case Study in the Fast-Food Industry.” Food Service Technology 4 (2004): 75-84.

In this highly technical paper, three industrial engineering professors in Korea and one services management professor in the UK discuss the mathematical limitations of the popular SERVQUAL scales. Significantly, they also aim to measure service quality in the fast-food industry, a neglected area of study. Unfortunately, the paper’s sophisticated analytical methods make it inaccessible to all but the most expert of researchers.

Battle, Ken. “Child Poverty: The Evolution and Impact of Child Benefits.” A Question of Commitment: Children's Rights in Canada . Ed. Katherine Covell and R.Brian Howe. Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. 2007. 21-44.

Ken Battle draws on a close study of government documents, as well as his own research as an extensively-published policy analyst, to explain Canadian child benefit programs. He outlines some fundamental assumptions supporting the belief that all society members should contribute to the upbringing of children. His comparison of child poverty rates in a number of countries is a useful wake-up to anyone assuming Canadian society is doing a good job of protecting children. Battle pays particular attention to the National Child Benefit (NCB), arguing that it did not deserve to be criticized by politicians and journalists. He outlines the NCB’s development, costs, and benefits, and laments that the Conservative government scaled it back in favour of the inferior Universal Child Care Benefit (UCCB). However, he relies too heavily on his own work; he is the sole or primary author of almost half the sources in his bibliography. He could make this work stronger by drawing from others' perspectives and analyses. However, Battle does offer a valuable source for this essay, because the chapter provides a concise overview of government-funded assistance currently available to parents. This offers context for analyzing the scope and financial reality of child poverty in Canada.

Journal Article Example

Kerr, Don and Roderic Beaujot. “Child Poverty and Family Structure in Canada, 1981-1997.” Journal of Comparative Family Studies 34.3 (2003): 321-335.

Sociology professors Kerr and Beaujot analyze the demographics of impoverished families. Drawing on data from Canada’s annual Survey of Consumer Finances, the authors consider whether each family had one or two parents, the age of single parents, and the number of children in each household. They analyze child poverty rates in light of both these demographic factors and larger economic issues. Kerr and Beaujot use this data to argue that.

Examples were taken from http://libguides.enc.edu/writing_basics/ annotatedbib/mla

Check out these resources for more information about Annotated Bibliographies.

- Purdue Owl- Annotated Bibliographies

- University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill- Annotated Bibliographies

- << Previous: Thesis Statement

- Next: Citing Sources >>

- Last Updated: Apr 4, 2024 5:51 PM

- URL: https://libguide.umary.edu/researchpaper

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

An annotated bibliography is a list of cited resources related to a particular topic or arranged thematically that include a brief descriptive or evaluative summary. The annotated bibliography can be arranged chronologically by date of publication or alphabetically by author, with citations to print and/or digital materials, such as, books, newspaper articles, journal articles, dissertations, government documents, pamphlets, web sites, etc., multimedia sources like films and audio recordings, or documents and materials preserved in archival collections.

Beatty, Luke and Cynthia Cochran. Writing the Annotated Bibliography: A Guide for Students and Researchers . New York: Routledge, 2020; Harner, James L. On Compiling an Annotated Bibliography . 2nd edition. New York: Modern Language Association, 2000.

Importance of a Good Annotated Bibliography

In lieu of writing a formal research paper or in preparation for a larger writing project, your professor may ask you to develop an annotated bibliography. An annotated bibliography may be assigned for a number of reasons, including :

- To show that you can identify and evaluate the literature underpinning a research problem;

- To demonstrate that you can identify and conduct an effective and thorough review of pertinent literature;

- To develop skills in discerning the most relevant research studies from those which have only superficial relevance to your topic;

- To explore how different types of sources contribute to understanding the research problem;

- To be thoroughly engaged with individual sources in order to strengthen your analytical skills; or,

- To share sources among your classmates so that, collectively, everyone in the class obtains a comprehensive understanding of research about a particular topic.

On a broader level, writing an annotated bibliography can lay the foundation for conducting a larger research project. It serves as a method to evaluate what research has been conducted and where your proposed study may fit within it. By critically analyzing and synthesizing the contents of a variety of sources, you can begin to evaluate what the key issues are in relation to the research problem and, by so doing, gain a better perspective about the deliberations taking place among scholars. As a result of this analysis, you are better prepared to develop your own point of view and contributions to the literature.

In summary, creating a good annotated bibliography...

- Encourages you to think critically about the content of the works you are using, their place within the broader field of study, and their relation to your own research, assumptions, and ideas;

- Gives you practical experience conducting a thorough review of the literature concerning a research problem;

- Provides evidence that you have read and understood your sources;

- Establishes validity for the research you have done and of you as a researcher;

- Gives you the opportunity to consider and include key digital, multimedia, or archival materials among your review of the literature;

- Situates your study and underlying research problem in a continuing conversation among scholars;

- Provides an opportunity for others to determine whether a source will be helpful for their research; and,

- Could help researchers determine whether they are interested in a topic by providing background information and an idea of the kind of scholarly investigations that have been conducted in a particular area of study.

In summary, writing an annotated bibliography helps you develop skills related to critically reading and identifying the key points of a research study and to effectively synthesize the content in a way that helps the reader determine its validity and usefulness in relation to the research problem or topic of investigation.

NOTE: Do not confuse annotating source materials in the social sciences with annotating source materials in the arts and humanities. Rather than encompassing forms of synopsis and critical analysis, an annotation assignment in arts and humanities courses refers to the systematic interpretation of literary texts, art works, musical scores, performances, and other forms of creative human communication for the purpose of clarifying and encouraging analytical thinking about what the author(s)/creator(s) have written or created. They are assigned to encourage students to actively engage with the text or creative object.

Annotated Bibliographies. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Annotated Bibliographies. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Annotated Bibliography. The Waldin Writing Center. Waldin University; Hartley, James. Academic Writing and Publishing: A Practical Guide . (New York: Routledge, 2008), p. 127-128; Writing an Annotated Bibliography. Assignment Structures and Samples Research and Learning Online, Monash University; Kalir, Remi H. and Antero Garcia. Annotation . Essential Knowledge Series. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2021.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Types

- Descriptive : This annotation describes the source without summarizing the actual argument, hypothesis, or message in the content. Like an abstract , it describes what the source addresses, what issues are being investigated, and any special features, such as appendices or bibliographies, that are used to supplement the main text. What it does not include is any evaluation or criticism of the content. This type of annotation seeks to answer the question: Does this source cover or address the topic I am researching? Collectively, this type of annotated bibliography synthesizes prior research about a topic or serves as a review of the literature before conducting a broader research study.

- Informative/Summative : This type of annotation summarizes what the content, message, or argument of the source is. It generally contains the hypothesis, methodology, and conclusion or findings, but like the descriptive type, you are not offering your own evaluative comments about such content. This type of annotation seeks to answer these types of questions: What are the author's main arguments? What are the key findings? What conclusions or recommended actions did the author state? Collectively, this type of annotated bibliography summarizes the way in which scholars have studied and documented outcomes about a topic.

- Evaluative/Critical/Analytical : This annotation includes your own evaluative statements about the content of a source. It is the most common type of annotation your professor will ask you to write. Your critique may focus on describing a study's strengths and weaknesses or it may describe the applicability of the conclusions to the research problem you are studying. This type of annotation seeks to answer these types of questions: Is the reasoning sound? Is the methodology sound? Does this source address all the relevant issues? How does this source compare to other sources on this topic? Collectively, this type of annotated bibliography offers a detailed analysis and critical assessment of the research literature about a topic.

NOTE: There are a variety of strategies you can use to critically evaluate a source based on its content, purpose, and format. A description of these strategies can be found here .

II. Choosing Sources for Your Bibliography

There are two good strategies to begin identifying possible sources for your bibliography--one that looks back into the literature and one that projects forward based on tracking sources cited by researchers.

- The first strategy is to identify several recently published [within the past few years] scholarly books using the USC Libraries catalog or journal articles found by searching a comprehensive, multidisciplinary database like ProQuest Multiple . Review the list of references to sources cited by the author(s). Review these citations to identify prior research published about your topic. For a complete list of scholarly databases GO HERE .

- The second strategy is to identify one or more books, book chapters, journal articles, or research reports on your topic and paste the title of the item into Google Scholar [e.g., from Negotiation Journal , entering the title of the article, " Civic Fusion: Moving from Certainty through Not Knowing to Curiosity " ]. If it is a short title or it uses a lot of common words, place quotation marks around the title so Google Scholar searches the source as a phrase rather than a combination of individual words. Below the citation may be a "Cited by" reference link followed by a number [e.g., Cited by 45]. This number refers to the number of times a source has subsequently been cited by other authors in other sources after the item you found was published.

Your method for selecting which sources to annotate depends on the purpose of the assignment and the research problem you are investigating . For example, if the course is on international social movements and the research problem you choose to study is to compare cultural factors that led to protests in Egypt with the factors that led to protests against the government of the Philippines in the 1980's, you should consider including non-U.S., historical, and, if possible, foreign language sources in your bibliography.

NOTE: Appropriate sources to include can be anything that you believe has value in understanding the research problem . Be creative in thinking about possible sources, including non-textual items, such as, films, maps, photographs, and audio recordings, or archival documents and primary source materials, such as, diaries, government documents, collections of personal correspondence, meeting minutes, or official memorandums. If you want to include these types of sources in your annotated bibliography, consult with a librarian if you're not sure where to locate them.

III. Strategies to Define the Scope of Your Bibliography

It is important that the scope of sources cited and summarized in your bibliography are well-defined and sufficiently narrow in coverage to ensure that you're not overwhelmed by the number of potential items to consider including. Many of the general strategies used to narrow a topic for a research paper are the same that be applied to framing the scope of sources to include in an annotated bibliography.

- Aspect -- choose one lens through which to view the research problem, or look at just one facet of your topic [e.g., rather than annotating a bibliography of sources about the role of food in religious rituals, create a bibliography on the role of food in Hindu ceremonies].

- Time -- the shorter the time period to be covered, the more narrow the focus [e.g., rather than political scandals of the 20th century, cite literature on political scandals during the 1980s].

- Comparative -- a list of resources that focus on comparing two or more issues related to the broader research topic can be used to narrow the scope of your bibliography [e.g., rather than college student activism during the 20th century, cite literature that compares student activism in the 1930s and the 1960s]

- Geography -- the smaller the area of analysis, the fewer items there are to consider including in your bibliography [e.g., rather than cite sources about trade relations in West Africa, include only sources that examine, as a case study, trade relations between Niger and Cameroon].

- Type -- focus your bibliography on a specific type or class of people, places, or things [e.g., rather than health care provision in Japan, cite research on health care provided to the elderly in Japan].

- Source -- your bibliography includes specific types of materials [e.g., only books, only scholarly journal articles, only films, only archival materials, etc.]. However, be sure to describe why only one type of source is appropriate.

- Combination -- use two or more of the above strategies to focus your bibliography very narrowly or to broaden coverage of a very specific research problem [e.g., cite literature only about political scandals during the 1980s that took place in Great Britain].

IV. Assessing the Relevance and Value of Sources All the items included in your bibliography should reflect the source's contribution to understanding the research problem . In order to determine how you will use the source or define its contribution, you will need to critically evaluate the quality of the central argument within the source or, in the case of including non-textual items, determine how the source contributes to understanding the research problem [e.g., if the bibliography lists sources about outreach strategies to homeless populations, a non-textual source would be a film that profiles the life of a homeless person]. Specific elements to assess a research study include an item’s overall value in relation to other sources on the topic, its limitations, its effectiveness in defining the research problem, the methodology used, the quality of the evidence, and the strength of the author’s conclusions and/or recommendations. With this in mind, determining whether a source should be included in your bibliography depends on how you think about and answer the following questions related to its content:

- Are you interested in the way the author(s) frame the research questions or in the way the author goes about investigating the questions [the method]?

- Does the research findings make new connections or promote new ways of understanding the problem?

- Are you interested in the way the author(s) use a theoretical framework or a key concept?

- Does the source refer to and analyze a particular body of evidence that you want to highlight?

- How are the author's conclusions relevant to your overall investigation of the topic?

V. Format and Content

The format of an annotated bibliography can differ depending on its purpose and the nature of the assignment. Contents may be listed alphabetically by author, arranged chronologically by publication date, or arranged under headings that list different types of sources [i.e., books, articles, government documents, research reports, etc.]. If the bibliography includes a lot of sources, items may also be subdivided thematically, by time periods of coverage or publication, or by source type. If you are unsure, ask your professor for specific guidelines in terms of length, focus, and the type of annotation you are to write. Note that most professors assign annotated bibliographies that only need to be arranged alphabetically by author.

Introduction Your bibliography should include an introduction that describes the research problem or topic being covered, including any limits placed on items to be included [e.g., only material published in the last ten years], explains the method used to identify possible sources [such as databases you searched or methods used to identify sources], the rationale for selecting the sources, and, if appropriate, an explanation stating why specific types of some sources were deliberately excluded. The introduction's length depends, in general, on the complexity of the topic and the variety of sources included.

Citation This first part of your entry contains the bibliographic information written in a standard documentation style , such as, MLA, Chicago, or APA. Ask your professor what style is most appropriate, and be consistent! If your professor does not have a preferred citation style, choose the type you are most familiar with or that is used predominantly within your major or area of study.

Annotation The second part of your entry should summarize, in paragraph form, the content of the source. What you say about the source is dictated by the type of annotation you are asked to write [see above]. In most cases, however, your annotation should describe the content and provide critical commentary that evaluates the source and its relationship to the topic.

In general, the annotation should include one to three sentences about the item in the following order : (1) an introduction of the item; (2) a brief description of what the study was intended to achieve and the research methods used to gather information; ( 3) the scope of study [i.e., limits and boundaries of the research related to sample size, area of concern, targeted groups examined, or extent of focus on the problem]; (4) a statement about the study's usefulness in relation to your research and the topic; (5) a note concerning any limitations found in the study; (6) a summary of any recommendations or further research offered by the author(s); and, (7) a critical statement that elucidates how the source clarifies your topic or pertains to the research problem.

Things to think critically about when writing the annotation include:

- Does the source offer a good introduction on the issue?

- Does the source effectively address the issue?

- Would novices find the work accessible or is it intended for an audience already familiar with the topic?

- What limitations does the source have [reading level, timeliness, reliability, etc.]?

- Are any special features, such as, appendices or non-textual elements effectively presented?

- What is your overall reaction to the source?

- If it's a website or online resource, is it up-to-date, well-organized, and easy to read, use, and navigate?

Length An annotation can vary in length from a few sentences to more than a page, single-spaced. However, they are normally about 300 words--the length of a standard paragraph. The length also depends on the purpose of the annotated bibliography [critical assessments are generally lengthier than descriptive annotations] and the type of source [e.g., books generally require a more detailed annotation than a magazine article]. If you are just writing summaries of your sources, the annotations may not be very long. However, if you are writing an extensive analysis of each source, you'll need to devote more space.

Annotated Bibliographies. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Annotated Bibliographies. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Annotated Bibliography. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Annotated Bibliography. Writing Center. Walden University; Annotated Bibliography. Writing Skills, Student Support and Development, University of New South Wales; Engle, Michael et al. How to Prepare an Annotated Bibliography. Olin Reference, Research and Learning Services. Cornell University Library; Guidelines for Preparing an Annotated Bibliography. Writing Center at Campus Library. University of Washington, Bothell; Harner, James L. On Compiling an Annotated Bibliography . 2nd edition. New York: Modern Language Association, 2000; How to Write an Annotated Bibliography. Information and Library Services. University of Maryland; Knott, Deborah. Writing an Annotated Bibliography. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Norton, Donna. Top 32 Effective Tips for Writing an Annotated Bibliography Top-notch study tips for A+ students blog; Writing from Sources: Writing an Annotated Bibliography. The Reading/Writing Center. Hunter College.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article >>

- Last Updated: Mar 6, 2024 1:00 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

How to Prepare an Annotated Bibliography

- Critical Appraisal & Analysis

Sample Annotations

Attributions.

- Citation Styles

Need Help? Ask Us.

Hesburgh Library First Floor University of Notre Dame Notre Dame, IN 46556

(574) 631-6258 [email protected]

Chat with us!

SAMPLE DESCRIPTIVE ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY ENTRY FOR A JOURNAL ARTICLE

The following example uses the APA format for the journal citation.

Waite, L. J., Goldschneider, F. K., & Witsberger, C. (1986). Nonfamily living and the erosion of traditional family orientations among young adults. American Sociological Review, 51 (4), 541-554.

This example uses the MLA format for the journal citation. NOTE: Standard MLA practice requires double spacing within citations.

Waite, Linda J., Frances Kobrin Goldscheider, and Christina Witsberger. "Nonfamily Living and the Erosion of Traditional Family Orientations Among Young Adults." American Sociological Review 51.4 (1986): 541-554. Print.

More Sample Annotations

- Annotated Bibliography Examples

- Annotated Bibliography Samples

The University of Toronto offers an example that illustrates how to summarize a study's research methods and argument.

The Memorial University of Newfoundland presents these examples of both descriptive and critical annotations.

The Writing Center at the University of Wisconsin gives examples of the some of the most common forms of annotated bibliographies.

The Writing Center at the University of North Carolina gives examples of several different forms of annotated bibliographies in 3 popular citation formats:

- MLA Example

- APA Example

- CBE Example